Abstract

Background:

We compared relapse-free survival (RFS) in gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO grade 3) and gastric carcinoma (GC). This is one of very few studies that compare the prognosis of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO grade 3, G3 NEC) with that of GC.

Methods:

Between 1996 and 2014, 63 patients were diagnosed with G3 NEC of the stomach and 56 with gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) with GC at Asan Medical Center in Seoul, Korea. We also randomly selected 762 patients diagnosed with GC between 1999 and 2008.

Results:

Patients with G3 NEC tumors that invaded the muscularis propria or shallower had poorer RFS than those with GC of the same type, while G3 NEC that invaded the subserosa or deeper had similar RFS to GC of that type. Patients diagnosed with G3 NEC with N0 or N2 had poorer RFS than the corresponding patients with GC, while those who had G3 NEC with N1 or N3 had similar RFS to the corresponding patients with GC. G3 NEC patients had poorer RFS than well-differentiated, moderately differentiated and poorly differentiated GC patients, while G3 NEC patients had similar RFS to that of those with signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC). In addition, patients with G3 NEC of stages I or IIa had poorer RFS than those with corresponding GC, while G3 NEC stage IIb or greater had similar RFS to the corresponding GC.

Conclusions:

Non-advanced G3 NEC showed poorer RFS than GC excluding SRC, while advanced G3 NEC has a similar RFS to that of GC without SRC. Therefore, we recommend that patients with non-advanced G3 NEC of the stomach be given a more aggressive treatment and surveillance than those with non-advanced GC excluding SRC.

Keywords: grade 3 NEC, gastric carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, relapse-free survival, WHO classification

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) of the stomach are rare and comprise about 0.1–0.6% of all gastric cancers [Matsubayashi et al. 2000]. However, gastric NETs have increased in incidence [Modlin et al. 2003, 2004]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed a classification of NETs of the digestive system based on the Ki-67 index (grade 1, ⩽2%; grade 2, 3–20%; and grade 3, >20%) [Hamilton and Aaltonen, 2000]. As of now, NETs are classified into the following subclasses: NETs, grade 1 (carcinoid); atypical carcinoid tumors (well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas), grade 2; poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (small and large cell type), grade 3. Rindi and colleagues have presented the ‘European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) TNM staging of foregut (neuro) endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system based on Ki-67 index and mitosis’ [Rindi et al. 2006], and Pape and colleagues have examined the prognostic relevance of a novel TNM classification system for upper gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) [Pape et al. 2008]. Recently, ENETS published consensus guidelines for the standard of care in NETs: ‘Towards a standardized approach to the diagnosis of GEP-NETs and their prognostic stratification based on TNM classification’ [Kloppel et al. 2009]. However, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) (7th edition) proposed that high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas and mixed glandular/well-differentiated NETs should be staged according to the guidelines used for staging carcinomas at that site [Edge et al. 2010]. Thus, the staging systems for NETs are not yet unified worldwide.

It is generally regarded that gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) are extremely malignant because they have aggressive biological behavior and frequently metastasize to lymph nodes and the liver, even in the early stages of the disease [Matsui et al. 1991]. It has been suggested that angioinvasion, tumor size, clinicopathological type, mitotic index and Ki-67 labeling index are predictors of tumor malignancy and patient outcome [Rindi et al. 1999]. However, there have been only few reports supporting this view [Jiang et al. 2006; Kubota et al. 2012]. In addition, Kim and colleagues reported that the small cell type of gastric NEC did not have such extreme behavior [Kim et al. 2013]. We sought to find reports that compared gastric NEC (WHO grade 3, G3) with gastric carcinoma (GC) in terms of relapse-free survival (RFS), but were unable to find such studies. We therefore presumed that a study on RFS comparison in NEC/GC would be a valuable addition to the current clinical knowledge in gastric cancer.

Methods

Between 1996 and 2013, 63 patients were diagnosed with poorly differentiated G3 NEC of the stomach, and 56 were diagnosed as mixed type at the Asan Medical Center in Seoul, Korea. Mixed type was defined as NET mixed with GC. None of the tumors had metastasized and all were curatively resected. All tissues were reviewed by a pathologist and classified according to the WHO 2010 classification [Hamilton and Aaltonen, 2000]. We also selected 762 patients with GC according to the following criteria: availability of entire specimen; blood samples; full follow-up records; and records of genetic analysis between 1999 and 2008. None had distant metastases at diagnosis and all underwent curative resection. We used the AJCC (7th edition) TNM classification for these tumors [Edge et al. 2010].

We compared the basic clinical features and survival data for the G3 NEC versus mixed type pair, for the G3 NEC versus GC pair, and for the GC versus the mixed type pair. RFS was defined as the time from resection to recurrence or last contact. We then evaluated clinical outcomes and RFS according to depth of invasion, nodal stage, AJCC TNM stages and histologic differentiation.

Numeric data are expressed as means with standard deviations, and compared using Student’s t-test. Risk factors were analyzed using the chi-square test. Survival data were examined using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. All statistical data were performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software; a p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study received approval from Asan Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

Subgroup clinicopathologic analysis: grade 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma, mixed type and gastric carcinoma

All 63 G3 NEC patients had invasion of the submucosa or deeper, and only 2 (3.7%) of the 56 patients with mixed types showed confinement to the mucosal layer. However, 196 (25.6%) of the GCs were confined to the mucosal layer. There were distinctive clinicopathologic differences between G3 NEC and GC (Table 1): patients with G3 NEC were older than those with GC (p < 0.05), and they experienced more lymph node metastases, had higher stages and suffered more tumor recurrence than did the GC patients (p < 0.05). Patients of the mixed type were also older than those with GC (p < 0.05) and experienced more lymph node metastases and higher stages (p < 0.05). In addition, they had a higher proportion of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCs) than the patients with GC (p < 0.05), while showing a lower proportion of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Subgroup clinicopathologic analysis; G3 NEC, mixed type, and GC.

| Patient characteristics | G3 NEC (n = 63, %) |

Mixed type (n = 56, %) |

GC (n = 762, %) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 61.7 ± 9.1 | 60.2 ± 10.6 | 50.9 ± 12.1 | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Gender | NS | |||

| Male | 48 (76.2) | 40 (71.4) | 517 (67.8) | |

| Female | 15 (23.8) | 16 (28.6) | 245 (32.2) | |

| Tumor site (%) | p < 0.05*,† | |||

| Upper third | 11 (17.5) | 1 (1.8) | 176 (23.1) | |

| Middle third | 21 (33.3) | 25 (44.6) | 306 (40.2) | |

| Lower third | 31 (49.2) | 30 (53.6) | 340 (44.7) | |

| Multiple | 6 (9.5) | 6 (10.7) | 12 (1.6) | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Adjuvant CTx | 35 (55.6) | 30 (53.6) | 294 (38.6) | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Tumor size (mm) | 56.9 ± 28.7 | 59.9 ± 29.2 | 50.8 ± 33.3 | p < 0.05‡ |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Well-differentiated | 1 (1.8) | 78 (10.2) | p < 0.05‡ | |

| Moderately differentiated | 14 (25.0) | 180 (23.6) | NS | |

| Poorly differentiated | 32 (60.7) | 339 (44.5) | p < 0.05‡ | |

| SRC type | 3 (5.4) | 149 (19.60) | p < 0.05‡ | |

| Others | 4 (7.1) | 16 (2.1) | p < 0.05‡ | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 55 (87.3) | 44 (78.6) | 266 (34.9) | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Lymph node metastasis | 40 (63.5) | 36 (64.3) | 314 (41.2) | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Recurrence | 24 (38.1) | 13 (23.2) | 121 (15.9) | p < 0.05† |

| T stage | p < 0.05†,‡ | |||

| 1 | 9 (14.3) | 7 (12.5) | 350 (45.9) | |

| 2 | 13 (20.6) | 14 (25.0) | 84 (11.0) | |

| 3 | 27 (42.9) | 27 (48.2) | 155 (20.3) | |

| 4 | 14 (22.2) | 8 (14.3) | 173 (22.8) | |

| Nodal stage | p < 0.05†,‡ | |||

| 0 | 23 (36.5) | 20 (35.7) | 448 (58.8) | |

| 1 | 14 (22.2) | 15 (26.8) | 93 (12.2) | |

| 2 | 15 (23.8) | 13 (23.2) | 82 (10.8) | |

| 3 | 11 (17.5) | 8 (14.3) | 139 (18.2) | |

| Stage | p < 0.05†,‡ | |||

| 1 | 15 (23.8) | 17 (30.3) | 384 (50.4) | |

| 2 | 22 (34.9) | 20 (35.7) | 151 (19.8) | |

| 3 | 26 (41.3) | 19 (40.0) | 230 (30.2) |

G3 NEC, grade 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma; GC, gastric carcinoma; NS, non-specific; SRC, signet ring cell carcinoma.

G3 NEC versus mixed type.

G3 NEC versus GC.

Mixed type versus GC.

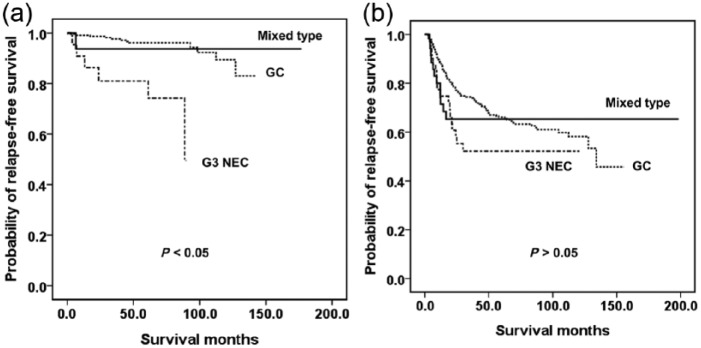

Figure 1 shows Kaplan–Meier estimates of RFS. Patients with G3 NEC had a lower survival rate than the other two groups (p < 0.05), who had similar RFS values (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for RFS in patients with grade 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma, mixed type or gastric carcinoma.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

We could not compare the adjuvant chemotherapy regimen between the three groups of tumors as a function of mucosal layer involvement because none of the G3 NEC was confined to the mucosa. We reviewed the adjuvant chemotherapy regimens administered for the patients. A total of 39 (61.9%) of the GC NEC patients received adjuvant chemotherapy and 21 (53.8%) of them received intravenous chemotherapy. A total of 37 (66.1%) of the mixed type patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, 14 (37.8%) received intravenous chemotherapy, and 14 received oral plus intravenous chemotherapy. For GC, 292 patients (38.3%) received adjuvant chemotherapy and 165 (56.5%) of them received oral plus intravenous chemotherapy. Regimens of oral chemotherapy or intravenous chemotherapy differed between G3 NEC and GC and between mixed type and GC. However, regimens of oral plus intravenous chemotherapy differed only between mixed type and GC. In stage 2 cancer, a similar proportion of patients in each group received chemotherapy. The route of chemotherapy administration differed between subgroups.

Matched-pair analysis according to depth of invasion

We analyzed the relation between clinicopathologic data and depth of invasions. For invasions reaching either the submucosa or the muscularis propria, the results were similar. In the submucosal layer, G3 NEC had more aggressive behavior, including lymph node metastasis and tumor recurrence, and poorer RFS than GC (p < 0.05). The mixed type also had poorer RFS than the GC. In the muscularis propria tumors, G3 NEC again exhibited more aggressive behavior, including lymphovascular invasion and tumor recurrence, and poorer RFS than the GC (p < 0.05), and the mixed types had poorer RFS than the GC as well. In the subserosal layer or beyond the subserosa, the results differed from those in the submucosa and muscularis propria: in the subserosal layer, there were no significant differences in lymph node metastasis and tumor recurrence between any groups (p > 0.05) and a similar trend was seen in the serosal layer.

Therefore, we divided the cases into two groups. Group 1 (Table 2) contained tumors invading the submucosa or muscularis propria; group 2 (Table 3) contained tumors invading the subserosa or beyond the subserosa. The G3 NEC in group 1 had more aggressive behaviors, including lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis and tumor recurrence, than did the GC (p < 0.05). They also had poorer RFS than the mixed type and GC (Figure 2a), which had similar RFS (Figure 2a) (p > 0.05). In contrast, there were no statistically significant differences in surgical outcomes including lymph node metastasis and recurrence between the various types in group 2 (Figure 2b) (p > 0.05)

Table 2.

Matched-pair analysis according to depth of invasion in submucosa or muscularis propria.

| Patient characteristics | G3 NEC (n = 22, %) |

Mixed type (n = 19, %) |

GC (n = 238, %) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 63.8 ± 7.5 | 62.1 ± 8.7 | 53.3 ± 12.1 | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Gender | p < 0.05‡ | |||

| Male | 13 (59.1) | 8 (42.1) | 170 (71.4) | |

| Female | 9 (40.9) | 11 (57.9) | 68 (28.6) | |

| Tumor site (%) | p > 0.05 | |||

| Upper third | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 27 (11.1) | |

| Middle third | 8 (36.4) | 9 | 106 (44.5) | |

| Lower third | 13 (59.1) | 10 | 105 (44.1) | |

| Multiple | 3 (13.6) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (0.8) | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Adjuvant CTx | 5 (22.7) | 2 (10.5) | 31 (13.1) | p >0.05 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 40.5 ± 22.1 | 50.1 ± 24 | 38.7 ± 20.0 | p < 0.05‡ |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 20 (90.9) | 13 (68.4) | 65 | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Lymph node metastasis | 11 (50.0) | 6 (31.6) | 60 (27.3) | p < 0.05† |

| Recurrence | 6 (27.3) | 1 (5.3) | 12 (5.0) | p < 0.05† |

G3 NEC, WHO grade 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma; GC, gastric carcinoma.

G3 NEC versus mixed type.

G3 NEC versus GC.

Mixed type versus GC.

Table 3.

Matched-pair analysis according to depth of invasion in subserosa or deeper.

| Patients characteristics | G3 NEC (n = 41, %) | Mixed type (n = 35, %) |

GC (n = 328, %) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 60.5 ± 9.8 | 59.2 ± 11.7 | 50.5 ± 12.6 | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Gender | p < 0.05†,‡ | |||

| Male | 35 (85.6) | 31 (88.6) | 217 | |

| Female | 6 (14.6) | 4 (11.4) | 111 | |

| Tumor site (%) | p < 0.05*,‡ | |||

| Upper third | 10 (24.4) | 1 (2.9) | 58 (17.7) | |

| Middle third | 13 (31.7) | 14 (40.0) | 134 (40.9) | |

| Lower third | 18 (43.9) | 20 (57.1) | 136 (41.4) | |

| Multiple | 3 (7.3) | 3 (8.6) | 5 (1.5) | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Adjuvant CTx | 30 (73.2) | 28 (80.0) | 262 (79.9) | p > 0.05 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 65.5 ± 28.3 | 66.9 ± 29.5 | 71.1 ± 35.3 | p > 0.05 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 35 (85.4) | 31 (88.6) | 193 (58.8) | p < 0.05†,‡ |

| Lymph node metastasis | 29 (70.7) | 30 (85.7) | 247 (75.3) | p > 0.05 |

| Recurrence | 18 (43.9) | 12 (34.3) | 105 (32.0) | p > 0.05 |

G3 NEC, WHO grade 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma; GC, gastric carcinoma.

G3 NEC versus mixed type.

G3 NEC versus GC.

Mixed type versus GC.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for relapse-free survival of (a) tumors invading the submucosa or muscularis propria; and (b) tumors invading the subserosa or deeper.

RFS according to nodal group, histologic differentiation and TNM stage

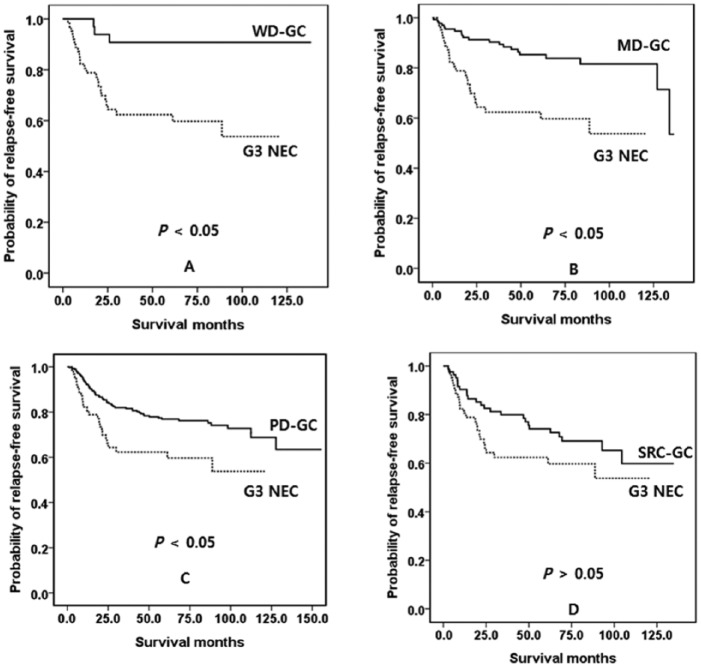

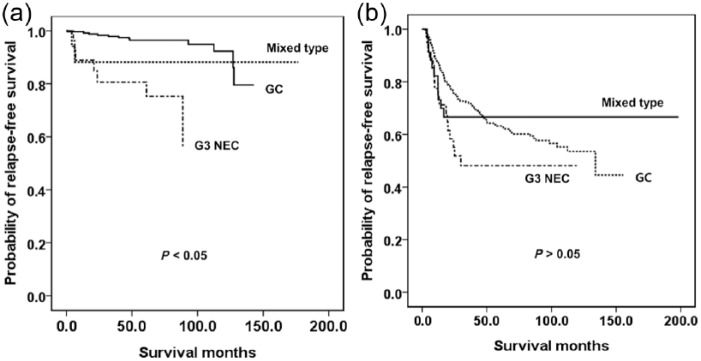

We evaluated RFS according to nodal stage. In N0 and N2, G3 had poorer RFS than the other two groups (p < 0.05), between which there was no difference in RFS (p > 0.05). However, in N1 and N3, there was no difference in RFS between any groups (p > 0.05). We evaluated RFS according to the histologic differentiation of the GC. G3 NEC had poorer RFS than well-differentiated, moderately differentiated or poorly differentiated GC (Figure 3a–c, p < 0.05). However, the RFS was similar to that of SRC GC (Figure 3d, p < 0.05). We also evaluated RFS according to TNM stage. In stage I, G3 NEC and the mixed type had poorer survival than GC (p < 0.05), but there was no difference in RFS between G3 NEC and mixed type (p > 0.05). In stage IIa, G3 NEC had poorer survival than the other two groups (p < 0.05), but there was no difference in RFS between G3 NEC and mixed type and between mixed type and GC (p > 0.05). In stage IIb, IIIa, IIIb or IIIc there was no difference in RFS between any groups (p < 0.05). Therefore, we divided the stages into two groups: stage I and IIa in group 1; and stage IIb through to IIIc in group 2. The G3 NEC in group 1 had poorer survival than the mixed type and GC (Figure 4a, p < 0.05), and there was no difference in survival between mixed type and GC (p > 0.05). In group 2 there was no difference in RFS between any of the types (Figure 4b, p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for RFS, according to histologic differentiation of the GC. (a) Well-differentiated GC versus G3 NEC. (b) Moderately differentiated GC versus G3 NEC. (c) Poorly differentiated GC versus G3 NEC. (d) SRC type GC versus G3 NEC.

G3 NEC, WHO grade 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma; GC, gastric carcinoma; MD, moderately differentiated; PD, poorly differentiated; RFS, relapse-free survival; SRC, signet ring cell carcinoma; WD, well-differentiated.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for RFS. (a) AJCC stage I or IIa. (b) AJCC stage IIb or IIIa–c.

G3 NEC, WHO grade 3 neuroendocrine carcinoma; GC, gastric carcinoma.

Discussion

The WHO and ENET grading systems according to Ki-67 index/mitosis have been validated for the foregut and particularly for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN)s (PanNENs), and their biological relevance and power to discriminate among prognostic groups has been widely confirmed [Ekeblad et al. 2008; Fischer et al. 2008; Pape et al. 2008; La Rosa et al. 2009; Scarpa et al. 2010]. However, the TNM stages of the AJCC and ENET have not yet been unified. In the AJCC (7th edition), the T categories for GC, NEC and adenocarcinoma with NET are: T1 – tumor invading the mucosa or submucosa; T2 – tumor invading the muscularis propria; T3 – tumor invading the subserosa; and T4 – tumor penetrating the serosa or invading adjacent structures. In contrast, the T categories for gastric NET are defined as: T1 – tumor invading the lamina propria or submucosa and 1 cm or less in size; T2 – tumor invading the muscularis propria or >1 cm in size; T3 – tumor penetrating the subserosa; and T4 – tumor invading serosal or other organs or adjacent structures [and for any T, add (m) for multiple tumors]. In contrast, ENET TNM stage is uniform for all gastric NET or NEC, unlike GC TNM stage. In this study we evaluated the TNM stage uniformly according to the AJCC (7th edition) definitions of GC, NEC, and adenocarcinoma with NET.

Gastric NET frequently contains an adenocarcinoma component [Waldum et al. 1998; Nishikura et al. 2003], and it has been proposed that gastric NET is derived predominantly from endocrine precursor cell clones arising in earlier adenocarcinoma components that transform into endocrine tumors during rapid clonal expansion [Nishikura et al. 2003]. A category of mixed adeno-neuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC) was recently proposed on the grounds that WHO 2010 did not define cases with both neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components [La Rosa et al. 2012]. In addition, there are no studies that support the 30% rule for the definition of MANEC. Thus, WHO 2010 classification is likely to be correct in the light of the evidence for the MANEC definition [Rindi et al. 2014]. Kim and colleagues reported that the neuroendocrine features of GC appeared to be correlated with clinicopathologic parameters such as high stage and high frequency of regional lymph node metastasis [Kim et al. 2011]. In our study, we could not establish the exact proportions of each component. Therefore, we defined NETs with any proportions of adenocarcinoma as a mixed type.

Recently, Park and colleagues evaluated the clinicopathologic features of GCs with neuroendocrine differentiation (NED) and found no significant difference in the survival rate between NEC and GC with 10–30% of NED [Park et al. 2014]. They therefore proposed that GCs with ⩾10% NED should be differentiated from conventional adenocarcinomas. They also recommended that the ⩾10% NED cut-off may be useful in practice and may serve as an informative parameter for predicting patient outcomes and establishing optimal therapeutic guidelines for GCs with NED.

Several studies have already shown that NEC of the stomach has a poor prognosis [La Rosa et al. 2011; Ishida et al. 2013]. However, there are few reports that have evaluated the prognostic significance of neuroendocrine components of GC [Jiang et al. 2006; Kubota et al. 2012]. In addition, Kim and colleagues reported that the small cell type of gastric NECs did not have such extreme behavior [Kim et al. 2013], and Kubota and colleagues reported that early detection and curative operations are essential for improving the prognosis of gastric NEC [Kubota et al. 2012].

Our study has the following limitations. NETs of the stomach are very rare; therefore, the statistical power of this study was limited by the relatively small number of patients. Recently, WHO 2010 defined MANEC as requiring >30% of each component. However, as mentioned above, we could not determine the exact proportions of the components, so we defined NETs with any portion of adenocarcinoma as mixed type. Another weakness is the lack of data on the expression of neuroendocrine markers in the control group. In addition, various adjuvant chemotherapy regimens were administered for patients in each type of tumor and the regimens differed widely among subgroups. Our study may also be prone to selection bias because the patients were selected according to the following criteria: availability of entire specimen, blood samples, full follow-up records, and records of genetic analysis.

In conclusion, even though the number of patients with GC NEC was very small and different adjuvant chemotherapy regimens were administered, our results show that G3 NEC has a worse prognosis than GC. G3 NEC tumors that invade only as far as the muscularis propria have poorer RFS than the corresponding cases of GC, while those that invade the subserosa or deeper have similar RFS to GC. Therefore, non-advanced G3 NEC of the stomach requires more aggressive treatment and surveillance than does GC, excluding the SRC type.

Footnotes

Ethical standards: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or its alternative was obtained from every patient in the study.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Beom Su Kim, Department of Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, 05505, Korea.

Young Soo Park, Department of Pathology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, 05505, Korea.

Jeong Hwan Yook, Department of Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, 05505, Korea.

Byung-Sik Kim, Department of Surgery Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, 88, Olympic-ro 43-gil, Songpa-gu, Seoul, 05505, Korea.

References

- Edge S., Byrd D., Compton C., Fritz A., Greene F., Trotti A. (2010) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ekeblad S., Skogseid B., Dunder K., Oberg K., Eriksson B. (2008) Prognostic factors and survival in 324 patients with pancreatic endocrine tumor treated at a single institution. Clin Cancer Res 14: 7798–7803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer L., Kleeff J., Esposito I., Hinz U., Zimmermann A., Friess H., et al. (2008) Clinical outcome and long-term survival in 118 consecutive patients with neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg 95: 627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton S., Aaltonen L. (2000) Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida M., Sekine S., Fukagawa T., Ohashi M., Morita S., Taniguchi H., et al. (2013) Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the stomach: morphologic and immunohistochemical characteristics and prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol 37: 949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Mikami T., Umezawa A., Saegusa M., Kameya T., Okayasu I. (2006) Gastric large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Am J Surg Pathol 30: 945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Oh S., Yook J., Park Y., Kim B. (2013) Primary small cell carcinoma of the stomach: clinical outcomes and prognoses. Am Surg 79: e305–e307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim J., Hur H., Cho Y., Han S. (2011) Clinicopathologic significance of gastric adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine features. J Gastric Cancer 11: 195–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloppel G., Couvelard A., Perren A., Komminoth P., McNicol A., Nilsson O., et al. (2009) ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: towards a standardized approach to the diagnosis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and their prognostic stratification. Neuroendocrinology 90: 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T., Ohyama S., Hiki N., Nunobe S., Yamamoto N., Yamaguchi T. (2012) Endocrine carcinoma of the stomach: clinicopathological analysis of 27 surgically treated cases in a single institute. Gastric Cancer 15: 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa S., Inzani F., Vanoli A., Klersy C., Dainese L., Rindi G., et al. (2011) Histologic characterization and improved prognostic evaluation of 209 gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Hum Pathol 42: 1373–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa S., Klersy C., Uccella S., Dainese L., Albarello L., Sonzogni A., et al. (2009) Improved histologic and clinicopathologic criteria for prognostic evaluation of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Hum Pathol 40: 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa S., Marando A., Sessa F., Capella C. (2012) Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas (MANECs) of the gastrointestinal tract: an update. Cancers (Basel) 4: 11–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi H., Takagaki S., Otsubo T., Iiri T., Kobayashi Y., Yokota T., et al. (2000) Advanced gastric glandular-endocrine cell carcinoma with 1-year survival after gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer 3: 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui K., Kitagawa M., Miwa A., Kuroda Y., Tsuji M. (1991) Small cell carcinoma of the stomach: a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 86: 1167–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlin I., Lye K., Kidd M. (2003) A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 97: 934–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlin I., Lye K., Kidd M. (2004) A 50-year analysis of 562 gastric carcinoids: small tumor or larger problem? Am J Gastroenterol 99: 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikura K., Watanabe H., Iwafuchi M., Fujiwara T., Kojima K., Ajioka Y. (2003) Carcinogenesis of gastric endocrine cell carcinoma: analysis of histopathology and p53 gene alteration. Gastric Cancer 6: 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape U., Jann H., Muller-Nordhorn J., Bockelbrink A., Berndt U., Willich S., et al. (2008) Prognostic relevance of a novel TNM classification system for upper gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer 113: 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Ryu M., Park Y., Park H., Ryoo B., Kim M., et al. (2014) Prognostic significance of neuroendocrine components in gastric carcinomas. Eur J Cancer 50: 2802–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindi G., Azzoni C., La Rosa S., Klersy C., Paolotti D., Rappel S., et al. (1999) ECL cell tumor and poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma of the stomach: prognostic evaluation by pathological analysis. Gastroenterology 116: 532–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindi G., Kloppel G., Alhman H., Caplin M., Couvelard A., De Herder W., et al. (2006) TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch 449: 395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindi G., Petrone G., Inzani F. (2014) The 2010 WHO classification of digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: a critical appraisal four years after its introduction. Endocr Pathol 25: 186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A., Mantovani W., Capelli P., Beghelli S., Boninsegna L., Bettini R., et al. (2010) Pancreatic endocrine tumors: improved TNM staging and histopathological grading permit a clinically efficient prognostic stratification of patients. Mod Pathol 23: 824–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldum H., Aase S., Kvetnoi I., Brenna E., Sandvik A., Syversen U., et al. (1998) Neuroendocrine differentiation in human gastric carcinoma. Cancer 83: 435–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]