Abstract

Background

Primary bile acid diarrhoea (BAD) is associated with increased bile acid synthesis and low fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19). Bile acid sequestrants are used as therapy, but are poorly tolerated and may exacerbate FGF19 deficiency.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the pharmacological effects of conventional sequestrants and a colonic-release formulation preparation of colestyramine (A3384) on bile acid metabolism and bowel function in patients with BAD.

Methods

Patients with seven-day 75selenium-homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) scan retention <10% were randomised in a double-blind protocol to two weeks treatment with twice-daily A3384 250 mg (n = 6), 1 g (n = 7) or placebo (n = 6). Thirteen patients were taking conventional sequestrants at the start of the study. Symptoms were recorded and serum FGF19 and 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4) measured.

Results

Median serum FGF19 on conventional sequestrant treatment was 28% lower than baseline values in BAD (p < 0.05). C4 on conventional sequestrant treatment was 58% higher in BAD (p < 0.001). No changes were seen on starting or withdrawing A3384. A3384 improved diarrhoeal symptoms, with a median reduction of 2.2 points on a 0–10 Likert scale compared to placebo, p < 0.05.

Conclusions

Serum FGF19 was suppressed and bile acid production up-regulated on conventional bile acid sequestrants, but not with A3384. This colonic-release formulation of colestyramine produced symptomatic benefit in patients with BAD.

Keywords: Bile acid sequestrants, colestyramine, fibroblast growth factor 19, bile acid malabsorption, bile acid diarrhoea, chronic diarrhoea, irritable bowel syndrome

Introduction

Bile acid diarrhoea (BAD) is characterised by chronic watery diarrhoea and is a consequence of increased delivery of bile acids to the colonic lumen.1 This can occur secondary to malabsorption in the terminal ileum due to inflammation or surgical resection, as commonly seen in Crohn’s disease (secondary BAD) or with a histologically normal ileum, (primary BAD). Primary BAD has been identified in excess of 25% of patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and may have a prevalence of up to 1% in the population.2,3 Primary BAD differs in mechanism to secondary BAD by a primary defect in fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) stimulation in the ileum. FGF19 is a potent inhibitor of bile acid synthesis in the liver, and lower serum FGF19 levels in primary BAD result in overproduction of bile acid that saturate ileal absorption capacity and spill over in to the colon.4 Bile acid production can be quantified in the serum by measuring the bile acid precursor, 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4). C4 inversely correlates with FGF19 and low FGF19, and high C4 is predictive of BAD.5 BAD is reliably diagnosed by 75selenium-homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) retention seven days after ingestion, with values of 10–15%, 5–10% and 0–5% representing mild, moderate or severe BAD respectively.

The currently available treatments for BAD are bile acid sequestrants, of which colestyramine is the most widely used. These are inactive resins that bind bile acids in the small bowel lumen, preventing diarrhoeal effects in the colon and increasing excretion. Treatment with these conventional sequestrants is effective in 75–88% of patients, but poor tolerance is common, with discontinuation rates of over 40%.6,7 Many of these effects are due to palatability or upper abdominal symptoms. In addition, conventional sequestrants may interact with other drugs including fat-soluble vitamins.8 Furthermore, binding of bile acids in the small bowel potentially decreases the ability of bile acids to bind to the ileal nuclear receptor Farnesoid X Receptor that controls transcription of FGF19. Lundasen et al. showed that administration of colestyramine to healthy volunteers reduced FGF19 by 87% and increased C4 18-fold.9 Since FGF19 has beneficial effects on bile acid metabolism as well as hepatic gluconeogenesis and lipid storage, the lowering of FGF19 by bile acid sequestrants may be undesirable.

A colonic-release formation of a bile acid sequestrant may be better tolerated by patients and allow physiological bile acid signalling in the ileum, as well as being devoid of interaction issues with other drugs. In 1984, a colonic-release tablet of colestyramine was shown to be efficacious, but with a large variability in patients with ileal resection, and the pharmacodynamic effects on FGF19 or C4 were not measured.10 A3384 is a novel multiparticular colonic-release formulation of colestyramine and the aim of the current study is to examine the pharmacodynamic effects of conventional bile acid sequestrants and A3384 in healthy volunteers and patients with BAD.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

We report on data from two industry sponsored trials (Albireo Pharmaceuticals AB, Sweden). Data from healthy volunteers were used from a phase I dose-ranging study into another compound (A4250): ‘Safety and pharmacokinetics of A4250 in healthy subjects’, (EudraCT number 2013-001175-21). The A4250 results have been reported in a separate publication.11 During this study, in three arms, healthy volunteers took either 1 g b.d. conventional colestyramine (n = 2) or 1 g b.d. A3384 (n = 6), or placebo (n = 4) for one week. Subjects and staff were blinded to their treatment and these subjects received a placebo form of A4250, although blinding was not possible for the powdered colestyramine group. This study was conducted by Quotient Clinical, Nottingham, UK and the results of the primary outcome have already been reported.11

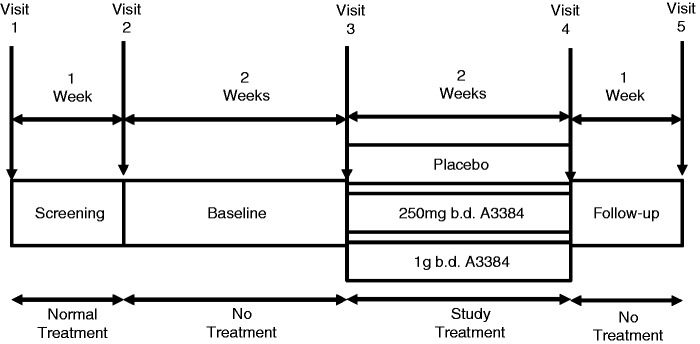

Data from patients with BAD were used from a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial: ‘A3384 in bile acid malabsorption/diarrhoea’ (EudraCT number 2013-002924-17). Patients were recruited from three sites, one in the UK and two in Sweden from April–December 2014. After a one-week screening period, during which the patients took their normal treatment for BAD, all bile acid sequestrants were stopped for two weeks before randomisation to either 250 mg b.d. A3384 or 1 g b.d. A3384, or placebo for two weeks. The patients returned one week later for a follow-up visit, before restarting their standard conventional sequestrants. A schematic of the trial design is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Design of the A3384 in bile acid diarrhoea (BAD) study.

This study was stopped early due to poor recruitment. The sample size of 36 patients had been determined in order to detect a 40% reduction in mean number of bowel motions during the last week of treatment in the group dosed with 1 g b.d. A3384 compared to placebo with a power of 90% and an alpha of 0.05. This assumed a mean number of bowel motions/day of four in the placebo group as reported by Jacobsen et al.10 Based on these calculations, 12 patients per treatment arm were required. At the time of the trial closing, 19 patients had undergone randomisation.

The study protocols for both studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and were approved by ethics committees in the UK and in Sweden.

Study population

For the healthy volunteer study, men and women with no concurrent illnesses or medications, between the ages of 18–60 years and with a body mass index (BMI) 18–32 were eligible. For the BAD study, men and women aged 18–80 years with a BMI between 18.5–35 were eligible for inclusion in the trial if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) three stools of Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) ≥5 per day on average, calculated from seven days off therapy; (b) SeHCAT seven-day retention of <10% (moderate or severe impairment), within the last five years with no change in symptoms since; (c) ≥21 bowel motions in the last seven days before randomisation, of which >50% are BSFS ≥5; (d) macroscopically normal colonoscopy with no histological evidence of microscopic colitis within the last five years. Exclusion criteria are listed in the Supplementary Material.

Treatment allocation

Healthy volunteers were admitted to a clinical research facility two days before randomisation by sequential numbering to treatment arms. They remained in the facility until 24 h after the last dose nine days later.

Randomisation of patients with BAD to treatment arms occurred at visit 3 after checking the eligibility criteria. Randomisation was double blind and stratified according to site. Patients were allocated to one of three treatment groups in a 1:1:1 ratio. The randomisation process is described in the Supplementary Material.

Pharmacodynamic parameters

Venous blood was taken for serum FGF19 and C4 after fasting for 6 h before dosing on the mornings of day 1 (baseline), 2, 7, 8 and 14 (follow-up) for healthy volunteers and on each visit for BAD patients. Assay methods are supplied in the Supplementary Material.

Symptom recording

Symptoms were not recorded in the healthy volunteer study. In the BAD study all patients were asked to record their bowel symptoms daily in a paper diary from visit 1 (first day of screening) to visit 4 (last day of treatment). In the diary patients recorded the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) for each bowel movement (1 = hard lumps, 2 = lumpy sausage, 3 = cracked sausage, 4 = smooth sausage, 5 = soft lumps, 6 = mushy and 7 = watery).12 They were also asked to rate their diarrhoea, abdominal discomfort or bloating over the last 24 h on a 0–10 Likert scale where 0 = none and 10 = very severe. At each visit the diary was collected and a new one issued.

Safety parameters

On each visit (or days 1, 2 and 8 for healthy volunteers) the patient’s vital signs were recorded, blood tests were taken for full blood count, liver function tests and renal profile. Urine samples underwent dipstick testing for protein, blood and leucocytes. On visits 1, 4 and 5 a physical examination was performed. Any changes to these tests or reported changes to symptoms not attributable to BAD were reported as adverse events.

Pharmacodynamic evaluation

Changes on starting and withdrawing A3384, conventional bile acid sequestrants and placebo in serum FGF19, C4 and bile acids (BAs) were analysed.

Clinical outcomes evaluation

Clinical outcomes were only collected for the BAD study. The study was underpowered for the primary efficacy endpoint: a reduction in mean daily number of bowel motions in the last seven days of treatment (week 5). The secondary efficacy endpoints were based upon the patients stool diary recordings in the last seven days of treatment and included: reduction in the severity of diarrhoea, abdominal discomfort or bloating using the rating scales, and reduction in stool consistency as measured by the BSFS.

Safety evaluation

The occurrence of treatment-emergent adverse effects based upon patient reports, visit blood tests and clinical assessments are reported descriptively.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy and pharmacodynamic effects were analysed using the intention-to-treat population which included all patients that had been randomised and had taken at least one dose of the trial medication.

Results were given as median (95% confidence interval (CI), if not stated otherwise) or percentage change. Where numbers were <4, the median (range) is reported and ‘range’ is clearly stated. Fishers exact test was used to compare proportions and Wilcoxon’s signed and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for statistical analysis of paired and unpaired data respectively. Values of p < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant; all statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 6 software (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, California, USA).

Results

Demographics and safety (BAD patients)

Thirty-four patients were screened for the study, and 15 patients dropped out before randomisation. The most common reason for screening failure was less than 21 episodes of diarrhoea during the run-in period (six patients). Nineteen patients entered the trial, forming the intention-to-treat cohort of whom 15 patients completed the trial as per protocol. For all reported results the intention-to-treat population was used, as discriminatory analysis showed no significant differences with the per protocol population. Of the 19 patients in the intention-to-treat population, 11 were recruited at centre 1 in the UK, six at centre 2 in Sweden and two at centre 3 in Sweden. The demographics of this population by treatment arm are shown in Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences in these parameters. There were four minor treatment-emergent adverse effects reported on A3384, these were nausea, cardiac palpitations, upper abdominal pain and hyperhidrosis. Seven treatment-emergent adverse effects were reported in the placebo group.

Table 1.

Demographics of the intention-to-treat bile acid diarrhoea (BAD) patient population

| A3384 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 g b.d. | 250 mg b.d. | Placebo | All | |

| Overall n | 7 | 6 | 6 | 19 |

| Female n (%) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50) | 8 (42.1) |

| Mean age (SD) | 46.4 (20.4) | 50 (21.28) | 38.7 (17.57) | 45.1 (19.31) |

| Caucasian n (%) | 5 (71.4) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) | 14 (73.7) |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 28.7 (5.1) | 28.4 (5.17) | 26.6 (4.44) | 27.9 (4.79) |

BMI: body mass index; SD: standard deviation.

Effect of conventional sequestrants and A3384 on FGF19 and C4

Healthy volunteers

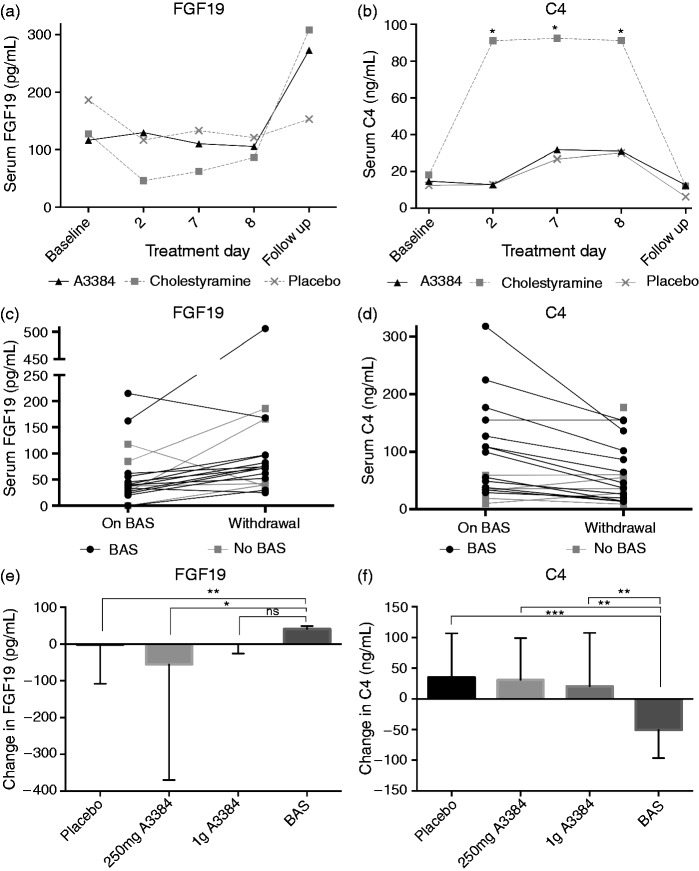

Administration of conventional colestyramine lowered serum FGF19 in healthy volunteers on day seven of treatment by 58% from baseline. In both the A3384 and placebo arms, a reduction of 30% was seen from baseline to day seven of treatment. Median FGF19 values are shown in Table 2 and in Figure 2(a). There were no statistically significant differences between treatment arms, or within the treatments when compared to baseline.

Table 2.

Fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) in healthy volunteers on bile acid sequestrant treatment

| Baseline day 1 | Treatment day 2 | Treatment day 7 | Treatment day 8 | Follow-up day 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 4) | 114 (53–264) | 44 (28–190) | 82 (35–131) | 76(34–199) | 139 (27–208) |

| Colestyramine (n = 2) | 167 (134–199) | 72 (33–112) | 71 (50–91) | 116 (88–143) | 389 (329–449) |

| A3384 (n = 6) | 133 (48–172) | 126 (44–198) | 96 (50–243) | 98 (43–158) | 258 (98–456) |

Serum fasting FGF19 in pg/ml, median (range).

Figure 2.

(A-F): Effect on fasting serum FGF19 (A) and C4 (B) of conventional colestyramine, 1g b.d. (n=2), A3384 (colonic release colestyramine) 1g b.d. (n=6) or placebo (n=4) in healthy volunteers. Plots of individual change in FGF19 (C) and C4 (D) on conventional bile acid sequestrants (BAS) on visit 2 (on BAS) and 2 weeks after withdrawal on visit 3 (withdrawal) in BAD patients. Median change (IQR) in fasting FGF19 (E) and C4 (F) on withdrawal of placebo, colonic release colestyramine (A3384 250mg b.d or 1g b.d.) compared to withdrawal of conventional bile acid sequestrants (BAS). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns = non-significant.. C4: 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one; FGF19: fibroblast growth factor 19.

There was a five-fold increase in serum C4 on colestyramine treatment from baseline, and the maximum change for both A3384 and placebo was a two-fold change. The change in C4 was statistically significant for colestyramine when compared to baseline values for all days on treatment. Serum C4 returned to baseline values when colestyramine was stopped (Figure 2(b)). Changes from baseline C4 for both the A3384 and placebo groups were not statistically significant. When median values were compared between treatment arms, the trend for higher C4 on colestyramine did not reach statistical significance, the maximum difference (64.3 ng/ml) between median C4 between the arms was on day eight of treatment (placebo 27 (range 23–42), A3384 31 (22–57), colestyramine 91 (58–124), A3384 versus colestyramine, p = 0.07).

Patients with BAD

To compare the effects of conventional sequestrants to A3384, changes in FGF19 and C4 were measured at visit 2 (on conventional sequestrants) and visit 3 (off conventional sequestrants) to measure the effect of conventional sequestrant withdrawal. This was compared to visit 4 (on A3384) and visit 5 (off A3384) in order to evaluate the effect of A3384 withdrawal. Thirteen patients across all treatment groups were taking conventional sequestrants in week one (seven took colestyramine, four took colesevelam, two took colestipol). On withdrawal of conventional sequestrants, FGF19 increased by 28% (median FGF19 visit 2; 58.6 pg/ml (21.9–95.3), visit 3; 74.8 pg/ml (33.7–184), p = 0.01), This was supported by a 58% decrease in serum C4 (median C4 visit 2; 109 ng/ml (65.8–168.7), visit 3; 45.7 ng/ml (33.9–99.6), p = 0.0005).

Such effects on FGF19 and C4 were not seen with either dose of A3384. There was a non-significant trend for higher FGF19 on 250 mg A3384 (45% increase on starting (visit 4, vs visit 3), 33% decrease on withdrawal (visit 4 vs visit 5)). Similar changes were seen in C4, with a non-significant trend towards lower C4 on treatment with A3384. Median values and changes are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2(e), 2(f).

Table 3.

Fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) and C4 in bile acid diarrhoea patients taking A3384.

| Placebo | A3384 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 250 mg b.d. | 1 g b.d. | ||

| Visit 3 (baseline) | |||

| FGF19 | 57.1(20.4–129.4) | 86.5 (–16.5–347.2) | 62 (23–112.8) |

| C4 | 27.3 (9.4–68.8) | 50.8 (39.5–163.8) | 55.4 (20–148.8) |

| Visit 4 (treatment) | |||

| FGF19 | 107.9 (34.3–168.4) | 125.5 (–42.5–552.2) | 50.9 (20.1–90) |

| C4 | 30.7 (2.6–92.2) | 33.5 (13–122.9) | 82.1 (23.4–126.5) |

| Change Visit 3-Visit 4 | |||

| FGF19 | 34.85 (–48.34–101.3) | 39.75 (–76.74–255.7) | –9.3 (–31.92–6.32) |

| C4 | 8.55 (–20.16–36.83) | 8.25 (–57.12–30.12) | –0.74 (–39.3–20.37) |

| Visit 5 (withdrawal) | |||

| FGF19 | 72.6 (18.5–111.2) | 79.9 (11.7–206.7) | 53.0 (16–107.6) |

| C4 | 47.9 (–37.8–202.2) | 86.1 (17.5–153.4) | 49.7 (–5.3–195.7) |

| Change Visit 5-Visit 4 | |||

| FGF19 | –0.9 (–100.5–27.54) | –55.8 (–386.4–95.2) | 0 (–30.4–43.88) |

| C4 | 13.55 (–16.38–178) | –2.35 (–29.3–122) | 1.42 (–82.5–202.8) |

Median (95% confidence interval (CI)) serum FGF19 (pg/ml) and C4 (ng/ml) in bile acid diarrhoea patients at baseline (visit 3) and after two weeks on treatment with either 250 mg b.d. A3384, 1 g b.d. A3384 or placebo (visit 4) and one week after treatment withdrawal (visit 5) and median (95% CI) change between visit 3 (baseline, before treatment), visit 4 (on treatment for two weeks) and visit 5 (one week after treatment withdrawal).

When the median change of FGF19 in withdrawal of conventional sequestrants (V2–V3) was compared to withdrawal of A3384 (V4–V5) there was a median increase in FGF19 ‘off conventional sequestrants' and a decrease off A3384 (combined doses) (+41.5 vs −16 ng/ml, p < 0.05) (Figure 2(e)). This trend was also seen in serum C4 with a decrease ‘on conventional sequestrants' withdrawal, but an increase ‘on A3384' withdrawal, that was statistically significant for all treatment arms compared to conventional sequestrants (Figure 2(f)). There were no significant differences in FGF19 or C4 upon withdrawal in either A3384 or placebo arm.

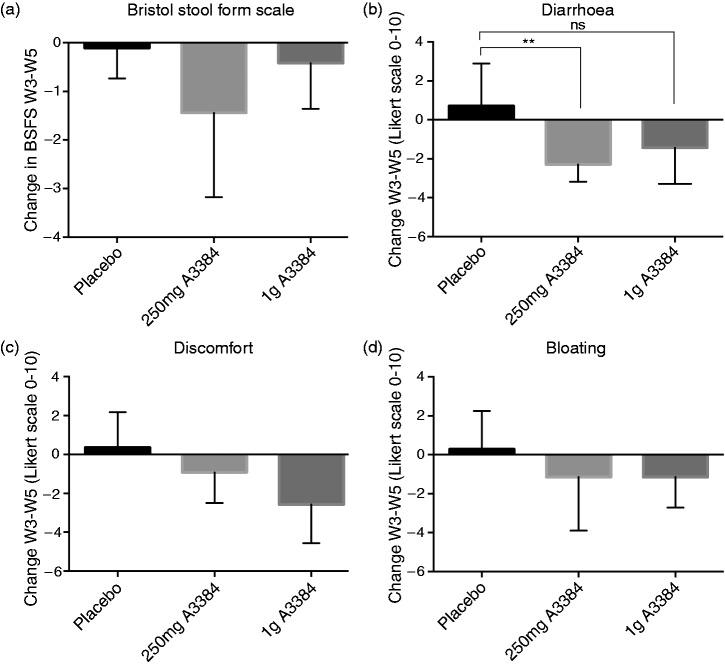

Effect of colonic-release colestyramine on bowel symptoms and BSFS

The median stool type as measured by BSFS reduced in all groups from week 3 to week 5 (Figure 3(a)). Median change in the placebo arm was –0.1 (0.8–0.5), in 250 mg A3384 –1.4 (−4.1–0.4), in 1 g A3384 –0.4 (−1.4–0) and in both A3384 doses combined −1.2 (−2.2–−0.2). This narrowly missed statistical significance for the 250 mg and combined A3384 arms (p = 0.058 and 0.065 respectively).

Figure 3.

(A-D): Median change (IQR) from week 3 (baseline, 2nd week of conventional bile acid sequestrant withdrawal) to week 5 (2nd week of treatment) in Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) (A), self-reported severity of diarrhoea (B), abdominal discomfort (C) and bloating (D). Answers were recorded on a 0-10 Likert scale daily and the mean value for the weeks calculated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns = non-significant.

Daily symptom rating scales

Patients were asked to rate their symptoms over the last 24 h on a 0–10 Likert scale. There was an improvement in diarrhoea scores for all treatment groups apart from placebo shown in Figure 3(b). Median change from week 3–week 5 was 0.7 (–1.2–3) for placebo, −2.3 (−3.4–−0.8) for 250 mg b.d. A3384, 1.4 (−3.5–−0.6) for 1 g b.d. A3384 and −2.1 (−2.8–−0.7) for both doses of A3384 combined. This reached statistical significance compared to placebo for the 250 mg and combined A3384 arms (but not for 1 g A3384 compared to placebo, p = 0.10). There were non-statistically significant improvements in abdominal discomfort and bloating in all A3384 treatment groups compared to placebo from week 3–week 5, shown in Figure 3(c) and 3(d).

Discussion

We have shown that administration of conventional bile acid sequestrants reduces FGF19 in patients with BAD. This decrease is not seen when administering bile acid sequestrants in colonic-release pellets in BAD patients. The reported 28% reduction in FGF19 may be an underestimate, since we also report a 58% decrease in FGF19 in healthy volunteers taking conventional colestyramine; possibly this reflects a difference in baseline FGF19 between healthy volunteers and BAD patients. More convincingly, C4, the functional marker of FGF19 action in the liver, increased in healthy volunteers taking conventional sequestrants (5.1-fold change) and in patients (1.6-fold change). This compares to the 18-fold increase in C4 reported by Lundasen et al.9 in healthy volunteers taking colestyramine and the 2.9-fold increase reported by Camilleri et al.13 in patients with IBS-D given colesevelam.

Serum C4 and FGF19 exhibit diurnal variation and values may vary within the same patient by up to four times from baseline depending on timing.14 This may explain some of the changes seen within the placebo groups, and the large ranges reported in the other arms. Despite the natural variances, and small number of patients, statistically significant differences in C4 have been found between the treatment groups. Intact delivery of the A3384 pellets to the colon was not assessed in this study, but the lack of decrease in FGF19 in the A3384 arms suggests that pellets behaved as designed. There is a potential for type II error in this comparison since the sample sizes for the A3384 and placebo arms are smaller than those of the conventional sequestrants group (n = 6–7 vs n = 13 respectively).

In addition to regulating bile acid homeostasis, FGF19 has an impact on many metabolic pathways which include insulin homeostasis, lipid regulation and body weight.15 Hypertriglyceridaemia and overweight are known associations of BAD.14 Restoring normal bile acid physiology in BAD requires further work with both FXR agonists,16 and A3384 to maximise therapeutic benefit without exacerbating the FGF19 pathophysiology of BAD.

Conventional sequestrants are poorly tolerated in around 40% of patients.3 This may be partly because colestyramine is formulated as a gritty powder, and also because all conventional sequestrants can cause upper abdominal symptoms. A colonic-release formulation of sequestrant will circumvent both of these problems. As bile acids exert effects on gastro-intestinal motility, binding of bile acids in the upper gastro-intestinal tract may cause slowing of small bowel motility; colesevelam has been shown to slow gastric emptying times.1,17 Colonic-release sequestrants should avoid these effects, so it is of interest that there was a small, non-significant decrease in reported daily pain and bloating, where we may have expected an increase with conventional sequestrants.

The A3384 in BAD study was stopped early and was underpowered to detect the primary endpoint of a 40% reduction in daily number of bowel motions. However, there was a non-significant trend on both doses of A3384, with 71% of patients on the larger dose reporting a reduction. The trend towards a lower number of daily bowel motions with A3384 is further supported by a near-significant reduction in stool form on treatment compared to placebo and significant decreases in daily diarrhoeal symptoms recorded by the Likert scale.

We have shown that conventional bile acid sequestrants may have detrimental effects on FGF19 and bile acid metabolism, and that these effects are not seen with a colonic-release preparation of colestyramine (A3384). A3384 was well tolerated and was efficacious in reducing diarrhoea. The ideal treatment for BAD should aim to restore physiological bile acid regulation and A3384, a colonic-release bile acid sequestrant, shows potential in this regard.

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to the memory of Hans Graffner, valued colleague and friend, who sadly passed away before the publication of this study. The authors wish to give thanks to the patients and healthy participants who made this study possible and for the diligent work of the staff of Albireo AB, Quotient Clinical Translational Pharmaceutics and IRW Consulting AB who worked on both trials. RA is the guarantor of this body of work, this manuscript and its scientific integrity. RA analysed and collected the data and prepared the manuscript. AB, MS, KU and JW contributed to the data collection and the trial design. PG and HG were responsible for the development of the new formulation of colestyramine, trial design and the collation of data between sites. All authors contributed to, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests

JW has served as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for Albireo AB, GE Healthcare, Intercept Pharmaceuticals and Pendopharm, and has received research funding from Albireo and Intercept which has supported RA. PG and HG are employees of Albireo AB and both own stocks and shares in Albireo AB.

Funding

This study was funded in full by Albireo AB. The writing of this paper was funded in part by Imperial College London. Initial data analyses were undertaken by Anna Torrång, Réka Conrad and Anna Asplind who are employees of IRW consulting AB and received funding from Albireo AB.

References

- 1.Appleby RN, Walters JR. The role of bile acids in functional GI disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014; 26: 1057–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slattery SA, Niaz O, Aziz Q, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The prevalence of bile acid malabsorption in the irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wedlake L, A'Hern R, Russell D, et al. Systematic review: The prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 707–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walters JRF, Tasleem AM, Omer OS, et al. A new mechanism for bile acid diarrhea: Defective feedback inhibition of bile acid biosynthesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 1189–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston IM, Pattni SS, Lin J, et al. Meal-stimulated FGF19 response and genetic polymorphisms in Primary Bile Acid Diarrhea. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: S268–S268. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghede MK, Schlutter JM, Agnholt JS, et al. Bile acid malabsorption investigated by selenium-75-homocholic acid taurine ((75)SeHCAT) scans: Causes and treatment responses to cholestyramine in 298 patients with chronic watery diarrhoea. Eur J Intern Med 2011; 22: e137–e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wedlake L, A'Hern R, Russell D, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of colesevelam hydrocholoride for bile-acid malabsorption in patients with cancer: A retrospective chart review and patient questionnaire. Clin Therap 2009; 31: 2549–2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johns WH, Bates TR. Quantification of the binding tendencies of cholestyramine. II. Mechanism of interaction with bile salt and fatty acid salt anions. J Pharm Sci 1970; 59: 329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundasen T, Galman C, Angelin B, et al. Circulating intestinal fibroblast growth factor 19 has a pronounced diurnal variation and modulates hepatic bile acid synthesis in man. J Intern Med 2006; 260: 530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen O, Hojgaard L, Moller EH, et al. Effect of enterocoated cholestyramine on bowel habit after ileal resection: A double blind crossover study. Br Med J 1985; 290: 1315–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graffner H, Gillberg PG, Rikner L, et al. The ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor A4250 decreases serum bile acids by interrupting the enterohepatic circulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heaton KW, Radvan J, Cripps H, et al. Defecation frequency and timing, and stool form in the general population: A prospective study. Gut 1992; 33: 818–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camilleri M, Acosta A, Busciglio I, et al. Effect of colesevelam on faecal bile acids and bowel functions in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41: 438–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galman C, Angelin B, Rudling M. Bile acid synthesis in humans has a rapid diurnal variation that is asynchronous with cholesterol synthesis. Gastroenterology 2005; 129: 1445–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang Q, Li H, Song Q, et al. Serum fibroblast growth factor 19 levels are decreased in Chinese subjects with impaired fasting glucose and inversely associated with fasting plasma glucose levels. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2810–2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters JR, Johnston IM, Nolan JD, et al. The response of patients with bile acid diarrhoea to the farnesoid X receptor agonist obeticholic acid. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41: 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odunsi-Shiyanbade ST, Camilleri M, McKinzie S, et al. Effects of chenodeoxycholate and a bile acid sequestrant, colesevelam, on intestinal transit and bowel function. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 8: 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]