Abstract

Background

Studies in small groups of patients indicated that splenic volume (SV) may be decreased in patients with celiac disease (CD), refractory CD (RCD) type II and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL).

Objective

The objective of this article is to evaluate SV in a large cohort of uncomplicated CD, RCD II and EATL patients and healthy controls.

Methods

The retrospective cohort consisted of 77 uncomplicated CD (of whom 39 in remission), 29 RCD II, 24 EATL and 12 patients with both RCD II and EATL. The control group included 149 healthy living kidney donors. SV was determined on computed tomography.

Results

The median SV in the uncomplicated CD group was significantly larger than in controls (202 cm3 (interquartile range (IQR): 154–275) versus 183 cm3 (IQR: 140–232), p = 0.02). After correction for body surface area, age and gender, the ratio of SV in uncomplicated CD versus controls was 1.28 (95% confidence interval: 1.20–1.36; p < 0.001). The median SV in RCD II patients (118 cm3 (IQR 83–181)) was smaller than the median SV in the control group (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates large inter-individual variation in SV. SV is enlarged in uncomplicated CD. The small SV in RCD II may be of clinical relevance considering the immune-compromised status of these patients.

Keywords: Celiac disease, refractory celiac disease, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, splenic volume, computed tomography, spleen

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic autoimmune-mediated enteropathy of the small bowel, caused by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically pre-disposed individuals resulting in villous atrophy.1 The prevalence of CD is 0.5%–1% in Western countries, North Africa, the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent.1–3 The only accepted treatment in CD is a life-long gluten-free diet (GFD). In less than 1% of CD patients, villous atrophy persists despite a GFD.4 After exclusion of other, mostly rare, diseases such as collagenous sprue, common variable immunodeficiency, Giardia lamblia and autoimmune enteropathy, these patients are diagnosed with refractory CD (RCD).5 RCD can be divided in two types based on the absence (type I) or presence (type II) of an intraepithelial lymphocyte population with an aberrant phenotype.6 This phenotype is characterized by lack of surface CD3 (sCD3) expression, but presence of intracellular CD3 complexes (iCD3). RCD II is now considered as a precursor of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL), a lymphoma with a poor prognosis.7,8

Splenic atrophy in CD patients has already been reported in a necropsy study in the 1970s.9 Impairment of splenic function in CD patients has been recognized over the years that was not associated with development of malignant disease.10–15 Similarly, functional hyposplenism can also be found in other diseases such as sickle cell disease and inflammatory bowel disease.16,17

In a pilot study, we observed that patients with RCD II and EATL appeared to have a smaller spleen on computed tomography (CT) than uncomplicated CD patients.18 Other studies involving small numbers of individuals suggested a small spleen in uncomplicated CD patients as well.19,20

The aim of this study was to evaluate in a large patient cohort whether splenic volume (SV), as measured by CT, is different in subgroups of CD as compared with healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Patients

All CD, RCD II and EATL patients included in this study have been initially diagnosed with CD according to the United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW) criteria.21 Indications for CT were assessment of abdominal complaints at diagnosis or follow-up of CD and/or (suspected) RCD II or EATL. Active CD was defined as Marsh III and/or positive serology for antibodies against tissue transglutaminase (TGA) type 2 and/or endomysium (EMA) six months before or after CT. CD in remission was defined as Marsh 0 or I and/or negative serology before or up to six months after CT. Patients were diagnosed with RCD II when other causes of villous atrophy had been excluded and more than 20% of the intra-epithelial lymphocytes showed an aberrant phenotype (sCD3− iCD3+) or when ulcerative jejunitis in CD was diagnosed.5 The control group included healthy individuals who underwent screening for kidney donation.

Methods

This study was a retrospective study including complicated and uncomplicated CD patients and controls who underwent CT between 2000 and 2013. SV was calculated by two expert radiologists with special interest in CD and scored according to a standard formula: SV = 30 + 0.58 (length × width × height).22 Body surface area (BSA) was calculated by the formula of Du Bois and Du Bois including height and weight.23

Statistical analysis

Differences in continuous variables between the different groups were analyzed using the Independent-Samples Kruskal–Wallis Test and the Independent-Samples Mann–Whitney U Test. For categorical variables we used the Pearson Chi-Square test. Differences in SV between the different groups were analyzed using both univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis. For the linear regression analysis, SV was transformed to a logarithmic scale because of the skewed distribution of this variable. The difference in means on the logarithmic scale was the ratio of geometric means after transforming the data back to the original scale. Multivariate linear regression analysis included the potential confounders age, gender and BSA up to one year before or after CT.24,25 We carried out backward linear regression analysis with a p value for removal of 0.1. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analysis were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20.

This study was presented to the Medical Ethics Review committee of VU University Medical Center. They confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) does not apply to this study and that an official approval of this study by the committee is not required.

Results

Initially, 322 individuals were included in the study. Of these individuals 31 were excluded because of positive CD antibodies together with Marsh 0, I or II (n = 13) or because of negative CD antibodies together with Marsh II or III (n = 18).

Ultimately, 291 individuals were included consisting of 149 healthy controls, 77 uncomplicated CD and 65 complicated CD patients, defined as RCD II and/or EATL. The uncomplicated CD group consisted of 38 patients with active CD and 39 patients with CD in remission. Median time between diagnosis of CD and CT in the CD in remission group was five years (interquartile range (IQR): 2–11), which is indicative for time using a GFD. The complicated CD group consisted of 29 RCD II patients, 24 EATL patients without history of RCD II and 12 patients with both RCD II and EATL. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total | Controls | CD | RCD II | EATL | Both RCDII and EATL | Overall p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 291 | 149 | 77 | 29 | 24 | 12 | – |

| Gender (M/F) (%) | 130/161 (45%/55%) | 72/77 (48%/52%) | 23/54 (30%/70%) | 16/13 (55%/45%) | 14/10 (58%/42%) | 5/7 (42%/58%) | 0.03 |

| Median age at CT (years) (range) | 57 (18–88) | 55 (26–84) | 51 (18–86) | 64 (44–88) | 64 (51–73) | 63 (56–68) | <0.001 |

| Median BSA (m2) (range) Missing BSA data (n) (%) | 1.84 (1.32–2.41) 23 (8%) | 1.93 (1.48–2.41) 3 (2%) | 1.80 (1.32–2.36) 13 (17%) | 1.68 (1.42–2.00) 4 (14%) | 1.83 (1.48–2.17) 2 (8%) | 1.70 (1.50–2.14) 1 (8%) | <0.001 |

| Median splenic volume (cm3) (IQR) | 185 (136–245) | 183 (140–232) | 202 (154–275) | 118 (83–181) | 195 (163–259) | 144 (129–238) | <0.001 |

CD: celiac disease; RCD II: refractory celiac disease type II; EATL: enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; M: male; F: female; CT: computed tomography; BSA: body surface area; IQR: interquartile range.

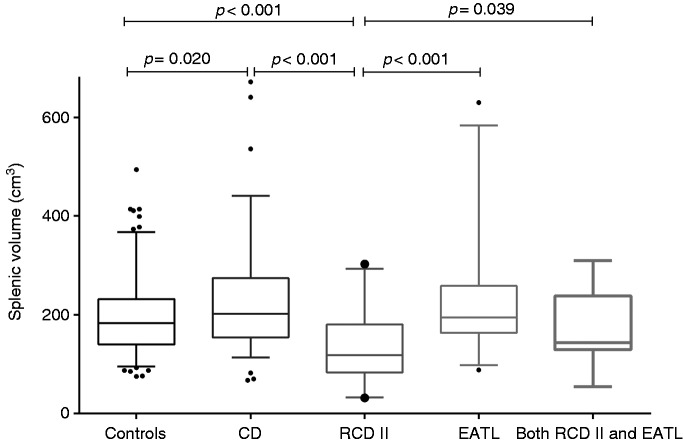

The median SV in the control group was 183 cm3 (IQR: 140–232), versus 202 cm3 (IQR: 154–275) in the uncomplicated CD group (p = 0.020), whereas in the complicated CD group a smaller median SV compared with controls of 162 cm3 (IQR: 114–210) was found (p = 0.026). Subdivision of the uncomplicated CD group showed a median SV of 223 cm3 (IQR: 168–328) in active CD and 192 cm3 (IQR: 143–253) in CD in remission (p = 0.196). Between these two CD subgroups, there was also no significant difference in age (p = 0.409), gender (p = 0.411) and BSA (p = 0.338). Subdivision of the complicated CD group showed a median spleen of 118 cm3 (IQR: 83–181) in RCD II, 195 cm3 in EATL (IQR: 163–259) and 144 cm3 (range: 54–310) in patients with both RCD II and EATL. A smaller spleen was found in RCD II patients without EATL compared both with controls and uncomplicated CD (both p < 0.001), as well as compared with EATL patients with or without RCD II (respectively p = 0.039 and p < 0.001). SV distribution is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Splenic volume (cm3) in different groups.

CD: celiac disease; RCD II: refractory celiac disease type II; EATL: enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; n: number.

A multivariate linear regression analysis was subsequently used to analyze the relationship between SV and the different groups taking into account the potential confounders BSA, age at time of CT (years) and gender. Due to the small number of patients in the different complicated CD subgroups, only the three main groups: controls, uncomplicated CD and complicated CD were compared in this analysis. BSA, age and gender were all significantly related to the logarithmic transformed SV on univariate regression analysis (all p < 0.001), as showed in Table 2. Performing backward multivariate regression, the variables complicated CD and gender were removed from the model. The corrected ratio of geometric means of SV in uncomplicated CD versus controls equals 1.28 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.20–1.36) (p = 0.001). Notably, both in univariate and multivariate analysis, BSA had the largest effect on SV (Tables 2 and 3). Performing the same backward analysis after dividing the uncomplicated CD group in active CD and CD in remission showed a significantly larger SV in both groups compared with controls with a ratio of 1.33 (CI 1.14–1.56), p < 0.001 and 1.23 (CI 1.03–1.45), p = 0.018, respectively. In this model, complicated CD and gender were also removed.

Table 2.

Univariate regression analysis: The relationship between splenic volume and other variables

| Unstandardized coefficients | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncomplicated CD (uncomplicated CD vs control) | 1.15 | 1.09–1.22 | 0.014 |

| Complicated CD (complicated CD vs control) | 0.82 | 0.77–0.88 | 0.004 |

| Gender (female vs male) | 0.80 | 0.76–0.84 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 0.991 | 0.989–0.993 | <0.001 |

| BSA (m2) | 2.23 | 1.97–2.54 | <0.001 |

CD: celiac disease; BSA: body surface area; CI: confidence interval.

Table 3.

Multivariate regression analysis: The relationship between splenic volume and other variables

| Unstandardized coefficients | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncomplicated CD (uncomplicated CD vs control) | 1.28 | 1.20–1.36 | <0.001 |

| Complicated CD (complicated CD vs control) | a | – | – |

| Gender (female vs male) | a | – | – |

| Age (years) | 0.994 | 0.992–0.996 | 0.002 |

| BSA (m2) | 2.46 | 2.17–2.78 | <0.001 |

Removed from the model by performing backward analysis.

CD: celiac disease; BSA: body surface area; CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

This study demonstrated large inter-individual variation in SV and the strong positive correlation between BSA in SV as described before.22,25 We observed a significantly larger SV in uncomplicated CD patients when compared with healthy controls, a difference that remained significant after correction for confounders. This is remarkable since both functional hyposplenism and splenic atrophy have been described in CD patients.10–17

The observation of Trewby et al. that CD patients on a GFD for several years had a smaller spleen than CD patients who had just started a GFD was not confirmed in this large data set.19

RCD II patients, a condition seen as a precursor of EATL, were found to have a smaller SV compared both with controls and uncomplicated CD. This observation may be of clinical relevance considering that these patients are generally considered immune-compromised because of malnutrition, wasting and mucosal immune dysfunction.

The finding of a smaller SV of RCD II patients in the absence of EATL compared with EATL patients with or without RCD II could probably be the effect of the lymphoma since extraintestinal presentations of EATL are common in the spleen.26

Since it has been reported that SV and splenic function are positively correlated with each other,27 there might be a correlation between splenic function and celiac disease as well. Our finding that SV did not differ between active CD and CD in remission is remarkably since previous studies have highlighted that a GFD was effective in restoring splenic function, except in CD patients with other autoimmune disorders, RCD and EATL.28,29 Splenic functions include phagocytosis of erythrocytes, recycling of iron, induction of adaptive immune responses and capture and removal of (encapsulated) pathogens.30 The latter function is achieved by the combination of specific anatomical features together with highly adapted macrophages of the spleen.31 Therefore, splenic atrophy and thereby impairment of splenic function could lead to an increased risk of infection with encapsulated bacteria such as Steptococcus pneumoniae. Although it is known that CD patients have a higher risk of pneumonia compared both to CD patients vaccinated against streptococcal pneumonia and the general population, there is a low pneumococcal vaccination rate in CD patients.32

As a consequence of impairment of splenic function, the risk of developing other auto-immune-mediated disease by T-regulatory cell depletion due to splenic dysfunction also increases.11 It is interesting that a recent study showed that the prevalence of other immune-mediated disorders was high at CD diagnosis (20%) and increased during follow-up with more than half of the patients developing new immune-mediated diseases despite a GFD.33 Splenic dysfunction can also lead to reduced platelet sequestration and defective removal of pits from erythrocytes. The first might induce thromboembolism, the latter an increase of circulating Howell-Jolly bodies and pitted red cells.11,34

The most important strength of this study is the inclusion of a unique large group of both complicated and uncomplicated CD and healthy controls. Although the RCD II cohort is one of the largest known RCD II cohorts in the literature, it is still too small to correct SV for BSA, age and gender. Further research is necessary to evaluate splenic function both in uncomplicated and complicated CD and how this relates to SV.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Castillo NE, Theethira TG, Leffler DA. The present and the future in the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2015; 3: 3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makharia GK, Mulder CJ, Goh KL, et al. Issues associated with the emergence of coeliac disease in the Asia-Pacific region: A working party report of the World Gastroenterology Organization and the Asian Pacific Association of Gastroenterology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 29: 666–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 1731–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nijeboer P, van Wanrooij RL, Tack GJ, et al. Update on the diagnosis and management of refractory coeliac disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2013; 2013: 518483–518483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Gils T, Nijeboer P, van Wanrooij RL, et al. Mechanisms and management of refractory coeliac disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12: 572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulder CJ, Wahab PJ, Moshaver B, et al. Refractory coeliac disease: A window between coeliac disease and enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 2000: 32–37. [PubMed]

- 7.Al-Toma A, Verbeek WH, Hadithi M, et al. Survival in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: Retrospective evaluation of single-centre experience. Gut 2007; 56: 1373–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tack GJ, Verbeek WH, Al-Toma A, et al. Evaluation of Cladribine treatment in refractory celiac disease type II. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17: 506–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson H. Necropsy studies on adult coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol 1974; 27: 710–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmon GS, Lee JS. Splenic atrophy in celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 8: A22–A22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Sabatino A, Brunetti L, Carnevale MG, et al. Is it worth investigating splenic function in patients with celiac disease? World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 2313–2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson A, Hutton MM, Maxwell JD, et al. Adult coeliac disease in hyposplenic patients. Lancet 1970; 1: 163–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corazza GR, Zoli G, Di Sabatino A, et al. A reassessment of splenic hypofunction in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Grady JG, Stevens FM, McCarthy CF. Celiac disease: Does hyposplenism predispose to the development of malignant disease? Am J Gastroenterol 1985; 80: 27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robertson DA, Swinson CM, Hall R, et al. Coeliac disease, splenic function, and malignancy. Gut 1982; 23: 666–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.William BM, Thawani N, Sae-Tia S, et al. Hyposplenism: A comprehensive review. Part II: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Hematology 2007; 12: 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.William BM, Corazza GR. Hyposplenism: A comprehensive review. Part I: Basic concepts and causes. Hematology 2007; 12: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallant M, Hadithi M, Al-Toma AB, et al. Abdominal computed tomography in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 1696–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trewby PN, Chipping PM, Palmer SJ, et al. Splenic atrophy in adult coeliac disease: Is it reversible? Gut 1981; 22: 628–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balaban DV, Popp A, Lungu AM, et al. Ratio of spleen diameter to red blood cell distribution width: A novel indicator for celiac disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94: e726–e726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.When is a coeliac a coeliac? Report of a working group of the United European Gastroenterology Week in Amsterdam, 2001. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 13: 1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Prassopoulos P, Daskalogiannaki M, Raissaki M, et al. Determination of normal splenic volume on computed tomography in relation to age, gender and body habitus. Eur Radiol 1997; 7: 246–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Bois D, Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. 1916. Nutrition 1989; 5: 303–311. discussion 312–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caglar V, Alkoc OA, Uygur R, et al. Determination of normal splenic volume in relation to age, gender and body habitus: A stereological study on computed tomography. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2014; 73: 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linguraru MG, Sandberg JK, Jones EC, et al. Assessing splenomegaly: Automated volumetric analysis of the spleen. Acad Radiol 2013; 20: 675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Catassi C, Bearzi I, Holmes GK. Association of celiac disease and intestinal lymphomas and other cancers. Gastroenterology 2005; 128(4 Suppl 1): S79–S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smart RC, Ryan FP, Holdworth CD, et al. Relationship between splenic size and splenic function. Gut 1978; 19: 56–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corazza GR, Frisoni M, Vaira D, et al. Effect of gluten-free diet on splenic hypofunction of adult coeliac disease. Gut 1983; 24: 228–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Sabatino A, Rosado MM, Cazzola P, et al. Splenic hypofunction and the spectrum of autoimmune and malignant complications in celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol 2005; 5: 606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraal G. Cells in the marginal zone of the spleen. Int Rev Cytol 1992; 132: 31–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zingone F, Abdul Sultan A, Crooks CJ, et al. The risk of community-acquired pneumonia among 9803 patients with coeliac disease compared to the general population: A cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 44: 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imperatore N, Rispo A, Capone P, et al. Gluten-free diet does not influence the occurrence and the Th1/Th17-Th2 nature of immune-mediated diseases in patients with coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis 2016; 48: 740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lammers AJ, de Porto AP, Bennink RJ, et al. Hyposplenism: Comparison of different methods for determining splenic function. Am J Hematol 2012; 87: 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]