Abstract

Objectives:

The objectives of our study were (1) to determine risk factors associated with tuberculosis (TB)–specific and non–TB-specific mortality among patients with TB and (2) to examine whether risk factors for TB-specific mortality differed from those for non–TB-specific mortality.

Methods:

We obtained data from the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System and included all patients who had TB between 2009 and 2013 in the United States and its territories. We used multinomial logistic regression analysis to determine the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of each risk factor for TB-specific and non–TB-specific mortality.

Results:

Of 52 175 eligible patients with TB, 1404 died from TB, and 2413 died from other causes. Some of the risk factors associated with the highest odds of TB-specific mortality were multidrug-resistant TB diagnosis (aOR = 3.42; 95% CI, 1.95-5.99), end-stage renal disease (aOR = 3.02; 95% CI, 2.23-4.08), human immunodeficiency virus infection (aOR = 2.63; 95% CI, 2.02-3.42), age 45-64 years (aOR = 2.57; 95% CI, 2.01-3.30) or age ≥65 years (aOR = 5.76; 95% CI, 4.37-7.61), and immunosuppression (aOR = 2.20; 95% CI, 1.71-2.83). All of these risk factors except multidrug-resistant TB were also associated with increased odds of non–TB-specific mortality.

Conclusion:

TB patients with certain risk factors have an elevated risk of TB-specific mortality and should be monitored before, during, and after treatment. Identifying the predictors of TB-specific mortality may help public health authorities determine which subpopulations to target and where to allocate resources.

Keywords: tuberculosis, mortality, surveillance

In 2015, 9557 tuberculosis (TB) cases were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from the 50 US states and the District of Columbia, and in 2014, 493 people died of TB.1 Because many people in the United States die each year of TB, public health officials designing TB prevention and control programs need to understand which factors are associated with TB-specific mortality.

Most studies of mortality involving patients with TB examined risk factors only as they relate to all-cause, rather than TB-specific, mortality.2–5 However, few distinguished TB-specific mortality from all-cause mortality.

At least one study, which was published in 2006, examined the relationship between various risk factors and TB-specific mortality in a low-burden setting (eg, the United States and Canada).6 However, this study included only patients who had completed treatment, and although many TB patients never receive treatment or receive only a short course of treatment, these findings were not generalizable to all patients with TB. Additional research that uses a broad population of TB patients and examines which risk factors contribute independently to TB-specific mortality may help public health authorities and departments develop TB prevention and intervention programs.

The objectives of our study were (1) to determine which risk factors were associated with TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality among a broad population of patients with TB living in a low-burden setting (eg, the United States) and (2) to examine if the risk factors for TB-specific mortality differed from the risk factors for non–TB-specific mortality.

Methods

Data Source and Collection

Before 2009, CDC’s Division of Tuberculosis Elimination obtained TB death information based on death certificate data in the National Vital Statistics System.7 In 2009, the Report of Verified Cases of Tuberculosis—the standardized TB reporting form used by TB programs in the United States to report cases of TB to CDC’s National Tuberculosis Surveillance System—was transitioned into a web-based reporting system.8 At that time, the Report of Verified Cases of Tuberculosis was also updated to include information about a TB patient’s cause of death.

Typically, attending health care professionals report a diagnosis of TB to their local health departments and designate whether a patient death is caused by TB. Using that information, health departments in each reporting jurisdiction then fill out the Report of Verified Cases of Tuberculosis forms and submit them to the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System. We obtained data from the system through a central database used for research and programmatic evaluation. CDC verified all TB diagnoses according to reporting guidelines.9 In addition, to determine crude TB-specific and non–TB-specific mortality rates, we obtained population estimates from the American Community Survey.10

Study Population

We obtained data from the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System and included in our study all patients, alive or dead, diagnosed with TB between 2009 and 2013. These patients were divided into 3 outcome-related categories: (1) patients who were alive at the time of TB diagnosis and who had not died during treatment (controls), (2) patients who were dead at the time of TB diagnosis or died during TB treatment and for whom TB was reported as a cause of death (TB-specific mortality), and (3) patients who were dead at the time of TB diagnosis or died during TB treatment and for whom TB was not reported as a cause of death (non–TB-specific mortality).

Variables

Risk factor variables of interest included age group, sex, duration of time in the United States, birthplace (foreign born vs US born), race/ethnicity, excessive alcohol use within the past year, resident of a correctional or long-term care facility, homelessness within the past year, injectable drug use within the past year, primary occupation, site of TB disease, previous episode of TB, type of TB therapy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, additional TB risk factors, reason for evaluation, and multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB. For race/ethnicity, because of low numbers of patients in some groups and some missing data, we created an “other or unknown” group that included patients whose race/ethnicity was multiracial, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, or unknown. The type of therapy variable included self-administered therapy and directly observed therapy, in which a trained health care worker or other designated person (excluding a family member) provided the prescribed TB drugs and watched the patient swallow every dose.

Statistical Methods

In 2009, 10 states were initially unable to provide TB mortality data because of delayed information technology upgrades (R. Pratt, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, CDC, personal communication, January 2017). Therefore, we examined annual secular trends in TB-specific mortality for 2009 through 2013 by comparing the crude rate ratio of non–TB-specific mortality with TB-specific mortality and were able to confirm the uniformity of our data.

We used descriptive statistics to report the risk factors of interest and Pearson χ2 tests to determine bivariate differences between the outcome groups. We defined significance as P ≤ .001.

To analyze the odds of TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality for each risk factor, we compared each group of patients with the group of all living patients with TB. Because we observed an interaction between the country of birth and race/ethnicity variables when we assessed our initial TB-specific mortality results, we combined these 2 variables when we analyzed the risk of TB-specific and non–TB-specific mortality.

We used multinomial logistic regression analysis to determine the effect of each risk factor on TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality. We chose the final regression model using stepwise, forward-selection, and backward-elimination strategies. We initially considered all risk variables for inclusion, but because of the large population size, we set statistical significance at α = .001 to decide whether to enter a variable into the regression model. Only variables that were selected with all 3 strategies were included in the final model. Although diabetes was not selected into the logistic regression model as a risk factor, we included it in the final model because of its clinical significance. Results were tabulated as unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (aORs), adjusted for the socioeconomic and clinical variables selected into the final model.

We performed a sensitivity analysis on 514 patients with TB whose information on cause of death was missing. When we added these patients to the TB-specific mortality group or the non–TB-specific mortality group or excluded them from analysis, we found a <10% change in the effect estimates. Because the observations among this subgroup did not have a meaningful effect on the overall study results, we excluded this subgroup from our analysis. We conducted statistical analyses with SAS version 9.4.11

Results

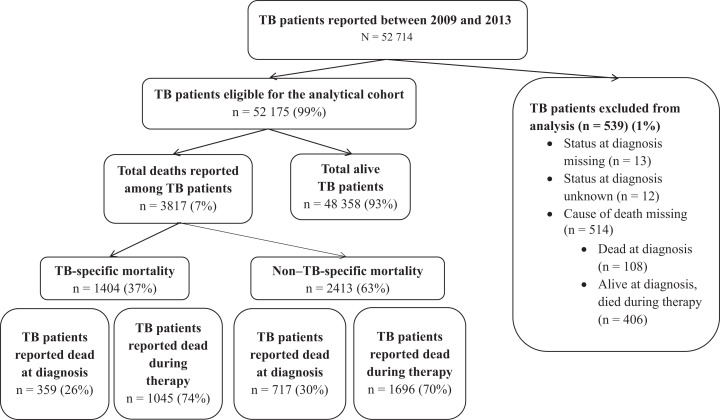

Of the 52 714 patients with TB reported to CDC from 2009 to 2013, 52 175 (99%) met the eligibility criteria for the study. Of these, 3817 (7.3%) died either at the time of TB diagnosis or during TB treatment, including 1404 (37%) who died from TB and 2413 (63%) who died from other causes (Figure).

Figure.

Flow diagram for 52 175 patients with tuberculosis (TB) in the United States reported to the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System between 2009 and 2013 and included in an analysis of the risk factors associated with TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality. Non–TB-specific mortality includes only patients for whom the cause of death was explicitly recorded as not due to TB. TB patients who died during therapy included patients for whom the cause of death was due to TB therapy, unrelated, or unknown.

The crude rate ratio of non–TB-specific mortality to TB-specific mortality in 2009 was 3.1 (0.23:0.08 per 100 000 population); between 2010 and 2013, the crude rate ratio ranged from 1.8 (0.20:0.11 per 100 000 population) to 2.1 (0.19:0.09 per 100 000 population). Throughout the study period, the annual proportion of TB patients who died of causes other than TB ranged from 4.7% to 6.4%, the annual proportion of TB patients who died because of TB ranged from 2.0% to 3.2%, and the annual proportion of TB patients who were alive ranged from 91.0% to 92.7%.

In bivariate analyses, multiple sociodemographic and clinical variables were associated with TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality (Tables 1 and 2). We found no association between recent homelessness and either type of mortality.

Table 1.

TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality, by sociodemographic risk factors, among patients with TB in the United States reported to the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System, 2009-2013a

| Sociodemographic Risk Factors | Patients, No.b (%)c | P Valued | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 52 175) | Alive (n = 48 358) | TB-Specific Mortality (n = 1404) | Non–TB-Specific Mortality (n = 2413) | ||

| Age group, y | 52 175 (100.0) | 48 355 (100.0) | 1403 (99.9) | 2413 (100.0) | <.001 |

| 0-14 | 2830 (5.4) | 2812 (99.4) | 12 (0.4) | 6 (0.2) | |

| 15-24 | 5498 (10.5) | 5461 (99.3) | 21 (0.4) | 16 (0.3) | |

| 25-44 | 16 935 (32.5) | 16 561 (97.8) | 172 (1.0) | 202 (1.2) | |

| 45-64 | 16 090 (30.8) | 14 891 (92.5) | 453 (2.8) | 746 (4.6) | |

| ≥65 | 10 818 (20.7) | 8630 (79.8) | 745 (6.9) | 1443 (13.3) | |

| Sex | 52 156 (100.0) | 48 340 (100.0) | 1403 (99.9) | 2413 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Male | 31 691 (60.8) | 29 159 (92.0) | 935 (3.0) | 1597 (5.0) | |

| Female | 20 465 (39.2) | 19 181 (93.7) | 468 (2.3) | 816 (4.0) | |

| Time in the United States, y | 52 175 (100.0) | 48 358 (100.0) | 1404 (100.0) | 2413 (100.0) | <.001 |

| <1 | 7256 (13.9) | 6850 (94.4) | 163 (2.3) | 243 (3.4) | |

| 1-9 | 11 247 (21.6) | 10 933 (97.2) | 130 (1.2) | 184 (1.6) | |

| ≥10 | 14 365 (27.5) | 13 293 (92.5) | 384 (2.7) | 688 (4.8) | |

| US born | 19 307 (37.0) | 17 282 (89.5) | 727 (3.8) | 1298 (6.7) | |

| Country of birth and race/ethnicity | 52 125 (99.9) | 48 323 (99.9) | 1399 (99.6) | 2403 (99.6) | <.001 |

| Foreign born | 32 818 (63.0) | 31 041 (94.6) | 672 (2.1) | 1105 (3.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 14 476 (27.8) | 13 624 (94.1) | 297 (2.1) | 555 (3.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 4437 (8.8) | 4296 (96.8) | 59 (1.3) | 82 (1.9) | |

| Hispanic | 11 378 (21.8) | 10 760 (94.6) | 254 (2.2) | 364 (3.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1654 (3.3) | 1527 (92.3) | 44 (2.7) | 83 (5.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic other or unknown | 873 (1.7) | 834 (95.5) | 18 (2.1) | 21 (2.4) | |

| US born | 19 307 (37.0) | 17 282 (89.5) | 727 (3.8) | 1298 (6.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 667 (1.3) | 638 (95.7) | 8 (1.2) | 21 (3.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 7721 (14.8) | 6893 (89.3) | 285 (3.7) | 543 (7.0) | |

| Hispanic | 3588 (7.1) | 3357 (93.6) | 104 (2.9) | 127 (3.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 6462 (12.4) | 5630 (87.1) | 280 (4.3) | 552 (8.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic othere or unknown | 869 (1.7) | 764 (87.9) | 50 (5.8) | 55 (6.3) | |

| Excessive alcohol use within past year | 52 109 (99.9) | 48 298 (99.9) | 1401 (99.8) | 2410 (99.9) | <.001 |

| Yes | 6067 (11.6) | 5498 (90.6) | 239 (3.9) | 330 (5.4) | |

| No or unknown | 46 042 (88.4) | 42 800 (93.0) | 1162 (2.5) | 2080 (4.5) | |

| Correctional facility resident at time of TB diagnosis | 51 993 (99.7) | 48 192 (99.7) | 1397 (99.5) | 2404 (99.6) | <.001 |

| Yes | 2114 (4.1) | 2057 (97.3) | 20 (1.0) | 37 (1.8) | |

| No or unknown | 49 879 (95.9) | 46 135 (92.5) | 1377 (2.8) | 2367 (4.8) | |

| Long-term care facility resident at time of TB diagnosis | 52 111 (99.9) | 48 304 (99.9) | 1400 (99.7) | 2407 (99.8) | <.001 |

| Yes | 1090 (2.1) | 722 (66.2) | 112 (10.3) | 256 (23.5) | |

| No or unknown | 51 021 (97.9) | 47 582 (93.3) | 1288 (2.5) | 2151 (4.2) | |

| Homeless within past year | 52 112 (99.9) | 48 305 (99.9) | 1400 (99.7) | 2407 (99.8) | .02 |

| Yes | 2786 (5.3) | 2565 (92.1) | 98 (3.5) | 123 (4.4) | |

| No or unknown | 49 326 (94.7) | 45 740 (92.7) | 1302 (2.6) | 2284 (4.6) | |

| Injectable drug use within past year | 52 125 (99.9) | 48 314 (99.9) | 1402 (99.9) | 2409 (99.8) | .001 |

| Yes | 753 (1.4) | 672 (89.2) | 28 (3.7) | 53 (7.0) | |

| No or unknown | 51 372 (98.6) | 47 642 (92.7) | 1374 (2.7) | 2356 (4.6) | |

| Primary occupation | 48 315 (92.6) | 44 583 (92.2) | 1375 (97.9) | 2357 (97.7) | <.001 |

| High-risk occupationf | 1829 (3.8) | 1792 (98.0) | 15 (0.8) | 22 (1.2) | |

| Not employed | 22 629 (46.8) | 20 921 (92.5) | 620 (2.7) | 1088 (4.8) | |

| Retired | 6655 (13.8) | 5209 (78.3) | 505 (7.6) | 941 (14.1) | |

| Other or unknown | 17 202 (35.6) | 16 661 (96.9) | 235 (1.4) | 306 (1.8) | |

Abbreviation: TB, tuberculosis.

aData source: National Tuberculosis Surveillance System, 2009-2013, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

bSome categories do not have observations for every patient included in the study because the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System is a passive surveillance system in which not every data field was completed for every patient.

cPercentages may not total to 100.0% because of rounding. Total percentages for each risk factor are column percentages from the total number of patients with TB in that category.

dP values are based on a Pearson χ2 test of independence. We defined significance as P ≤ .001.

eIncludes multiracial, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and unknown race.

fIncludes correctional employees and health care workers.

Table 2.

TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality, by clinical risk factors, among patients with TB in the United States reported to the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System, 2009-2013a

| Clinical Risk Factors | Patients, No.b (%)c | P Valued | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 52 175) | Alive (n = 48 358) | TB-Specific Mortality (n = 1404) | Non–TB-Specific Mortality (n = 2413) | ||

| Site of disease | 52 135 (99.9) | 48 321 (99.9) | 1404 (100.0) | 2410 (99.9) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary only | 36 193 (69.4) | 33 490 (91.6) | 1003 (2.7) | 1700 (4.7) | |

| Extrapulmonary only | 11 120 (21.3) | 10 502 (93.7) | 162 (1.5) | 456 (4.1) | |

| Both | 4822 (9.2) | 4329 (88.4) | 239 (4.9) | 254 (5.2) | |

| Previous episode of TB | 51 274 (98.3) | 47 480 (98.2) | 1395 (99.4) | 2399 (99.4) | .82 |

| Yes | 2415 (4.7) | 2232 (92.4) | 64 (2.7) | 119 (4.9) | |

| No or unknown | 48 859 (95.3) | 45 248 (92.6) | 1331 (2.7) | 2280 (4.7) | |

| Type of therapy | 46 844 (89.8) | 44 230 (91.5) | 991 (70.6) | 1623 (67.3) | <.001 |

| Self-administered | 4331 (9.2) | 4075 (94.1) | 98 (2.3) | 158 (3.7) | |

| Directly observed | 28 321 (60.5) | 26 322 (92.9) | 803 (2.8) | 1196 (4.2) | |

| Both | 13 917 (29.7) | 13 580 (97.6) | 81 (0.6) | 256 (1.8) | |

| Unknown | 275 (0.6) | 253 (92.0) | 9 (3.3) | 13 (4.7) | |

| HIV status at time of diagnosis | 47 545 (91.1) | 43 940 (90.9) | 1329 (94.7) | 2276 (94.3) | <.001 |

| Positive | 3164 (6.7) | 2807 (88.7) | 124 (3.9) | 233 (7.4) | |

| Negative | 37 141 (78.1) | 35 388 (95.3) | 649 (1.8) | 1104 (3.0) | |

| Testing not offered | 4164 (8.8) | 3033 (72.8) | 433 (10.4) | 698 (16.8) | |

| Othere or unknown | 3076 (6.5) | 2712 (88.2) | 123 (4.0) | 241 (7.8) | |

| Additional TB risk factorsf | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 6620 | 5809 (87.7) | 292 (4.4) | 519 (7.8) | <.001 |

| End-stage renal disease | 1048 | 690 (65.8) | 114 (10.9) | 244 (23.3) | <.001 |

| Any immunosuppressiong | 2374 | 1852 (78.0) | 152 (6.4) | 370 (15.6) | <.001 |

| TB-specific risk factorsh | 5499 | 5318 (96.7) | 80 (1.5) | 101 (1.8) | <.001 |

| Other | 10 404 | 9301 (89.4) | 388 (3.7) | 715 (6.9) | <.001 |

| None reported | 24 130 | 22 884 (94.8) | 517 (2.1) | 729 (3.0) | <.001 |

| Reason evaluated | 48 618 (93.2) | 44 863 (92.8) | 1384 (98.6) | 2371 (98.3) | <.001 |

| Abnormal chest x-ray | 9941 (20.4) | 8988 (90.4) | 320 (3.2) | 633 (6.4) | |

| Contact with a TB patient | 2386 (4.9) | 2356 (98.7) | 12 (0.5) | 18 (0.8) | |

| TB symptoms | 27 688 (57.0) | 25 682 (92.8) | 833 (3.0) | 1173 (4.2) | |

| Otheri or unknown | 8603 (17.7) | 7837 (91.1) | 219 (2.6) | 547 (6.4) | |

| MDR TB diagnosis | 39 236 (75.2) | 35 866 (74.2) | 1255 (89.4) | 2115 (87.7) | .02 |

| Yes | 522 (1.3) | 489 (93.7) | 19 (3.6) | 14 (2.7) | |

| No or unknown | 38 714 (98.7) | 35 377 (91.4) | 1236 (5.8) | 2101 (5.4) | |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MDR, multidrug resistant; TB, tuberculosis.

aData source: National Tuberculosis Surveillance System 2009-2013, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

bSome categories do not have observations for every patient included in the study, because the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System is a passive surveillance system in which not every data field was completed for every patient.

cPercentages may not total to 100.0% because of rounding. Total percentages for each risk factor are column percentages from the total number of patients with TB in that category.

dP values are based on a Pearson χ2 test of independence. We defined significance as P ≤ .001.

eIncludes HIV test refused, result indeterminate, and test done but results unknown.

fBecause these categories were not mutually exclusive, total data counts were not reported.

gIncludes immunosuppression, post–organ transplantation, and/or on tumor necrosis factor alpha–antagonist therapy.

hIncludes contact with patient with infectious TB or MDR TB, incomplete latent TB infection therapy, or missed contact in a TB cluster investigation.

iIncludes health care worker, employment/administrative test, immigration medical examination, incident laboratory result, and targeted TB testing.

In multivariate analyses, most of the risk factors that were significant predictors of mortality had a similar directional effect on TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality (Table 2). Although older age was a significant predictor of TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality, when compared with those aged 25-44 years, the odds of non–TB-specific mortality for those aged ≥65 years (aOR = 8.55; 95% CI, 6.61-11.07) were much higher than their odds of TB-specific mortality (aOR = 5.76; 95% CI, 4.37-7.61). Similarly, other risk factors predicted non–TB-specific mortality more strongly than TB-specific mortality: male sex (vs female), immunosuppression (vs not), long-term care facility resident at the time of TB diagnosis (vs not), and not employed and retired (vs other or unknown occupation). Several risk factors predicted TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality roughly equally: end-stage renal disease (vs not), other TB risk factors (vs none), and HIV-positive and other or unknown HIV status (vs HIV negative; Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds ratiosa for TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality, by sociodemographic and clinical risk factors, among patients with TB in the United States reported to the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System, 2009-2013b

| Risk Factors | TB-Specific Mortality | Non–TB-Specific Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 0-14 | 0.41 (0.23-0.74) | 0.08 (0.01-0.61) | 0.18 (0.08-0.39) | 0.21 (0.05-0.86) |

| 15-24 | 0.37 (0.24-0.58) | 0.36 (0.19-0.70) | 0.24 (0.14-0.40) | 0.30 (0.15-0.62) |

| 25-44 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| 45-64 | 2.93 (2.45-3.50) | 2.57 (2.01-3.30) | 4.11 (3.51-4.81) | 3.69 (2.90-4.69) |

| ≥65 | 8.31 (7.03-9.83) | 5.76 (4.37-7.61) | 13.71 (11.81-15.92) | 8.55 (6.61-11.07) |

| Male sex | 1.31 (1.17-1.47) | 1.36 (1.16-1.59) | 1.29 (1.18-1.40) | 1.41 (1.24-1.61) |

| Country of birth and race/ethnicity | ||||

| Foreign born | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.44 (0.37-0.52) | 0.67 (0.53-0.84) | 0.42 (0.37-0.52) | 0.78 (0.66-0.94) |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 0.28 (0.21-0.37) | 0.70 (0.46-1.06) | 0.20 (0.15-0.25) | 0.83 (0.60-1.15) |

| Hispanic | 0.48 (0.40-0.56) | 1.08 (0.85-1.37) | 0.35 (0.30-0.40) | 0.87 (0.71-1.06) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 0.58 (0.42-0.80) | 0.80 (0.52-1.23) | 0.55 (0.44-0.70) | 0.93 (0.67-1.29) |

| Non-Hispanic otherc or unknown | 0.43 (0.27-0.70) | 0.80 (0.40-1.63) | 0.26 (0.17-0.40) | 0.80 (0.45-1.43) |

| US born | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.25 (0.12-0.51) | 0.85 (0.29-2.46) | 0.34 (0.22-0.52) | 0.99 (0.43-2.30) |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 1.11 (0.88-1.40) | 1.13 (0.90-1.43) | 0.80 (0.71-0.91) | 1.05 (0.87-1.26) |

| Hispanic | 0.62 (0.50-0.78) | 1.39 (0.99-1.94) | 0.39 (0.32-0.47) | 1.05 (0.77-1.43) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Non-Hispanic otherc or unknown | 1.32 (0.97-1.80) | 1.97 (1.29-3.00) | 0.73 (0.55-0.98) | 1.26 (0.83-1.89) |

| Long-term care facility resident at time of TB diagnosisd | 5.73 (4.66-7.05) | 2.08 (1.55-2.79) | 7.84 (6.76-9.10) | 2.70 (2.15-3.39) |

| Primary occupation | ||||

| High-risk occupatione | 0.59 (0.35-1.00) | 1.00 (0.51-1.93) | 0.67 (0.43-1.03) | 1.06 (0.60-1.86) |

| Not employed | 2.10 (1.81-2.45) | 1.88 (1.52-2.34) | 2.83 (2.49-3.22) | 2.19 (1.81-2.66) |

| Retired | 6.87 (5.87-8.05) | 1.98 (1.52-2.57) | 9.84 (8.61-11.23) | 2.47 (1.97-3.08) |

| Other or unknown | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Site of TB disease | ||||

| Pulmonary only | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Extrapulmonary only | 0.52 (0.44-0.61) | 0.53 (0.40-0.69) | 0.86 (0.77-0.95) | 0.91 (0.76-1.09) |

| Both | 1.84 (1.60-2.13) | 1.96 (1.61-2.39) | 1.16 (1.01-1.32) | 1.32 (1.09-1.59) |

| Type of TB therapy | ||||

| Self-administered | 0.79 (0.64-0.98) | 0.94 (0.72-1.22) | 0.85 (0.72-1.01) | 0.84 (0.67-1.05) |

| Directly observed | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Both | 0.20 (0.16-0.25) | 0.20 (0.16-0.26) | 0.42 (0.36-0.48) | 0.47 (0.40-0.55) |

| Unknown | 1.17 (0.60-2.28) | 0.73 (0.28-1.89) | 1.13 (0.65-1.98) | 0.74 (0.33-1.68) |

| HIV status at time of TB diagnosis | ||||

| Positive | 2.41 (1.98-2.93) | 2.63 (2.02-3.42) | 2.66 (2.30-3.08) | 2.67 (2.13-3.36) |

| Negative | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Testing not offered | 7.78 (6.86-8.84) | 4.77 (3.96-5.76) | 7.38 (6.66-8.17) | 3.41 (2.89-4.02) |

| Otherf or unknown | 2.47 (2.03-3.01) | 1.58 (1.19-2.11) | 2.85 (2.47-3.29) | 1.76 (1.42-2.17) |

| Additional TB risk factorsg | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.92 (1.69-2.19) | 1.10 (0.89-1.36) | 2.01 (1.82-2.22) | 0.96 (0.81-1.14) |

| End-stage renal disease | 6.11 (4.97-7.50) | 3.02 (2.23-4.08) | 7.77 (6.67-9.05) | 2.97 (2.33-3.78) |

| Any immunosuppressionh | 3.05 (2.56-3.63) | 2.20 (1.71-2.83) | 4.55 (4.03-5.13) | 2.76 (2.28-3.33) |

| Other | 1.60 (1.42-1.81) | 1.38 (1.12-1.59) | 1.77 (1.62-1.94) | 1.35 (1.14-1.59) |

| None reported | 0.65 (0.58-0.72) | 0.95 (0.76-1.18) | 0.48 (0.44-0.53) | 0.74 (0.62-0.89) |

| Reason evaluated | ||||

| Abnormal chest x-ray | 1.27 (1.07-1.52) | 1.68 (1.29-2.18) | 1.01 (0.90-1.14) | 1.34 (1.10-1.62) |

| Contact with a TB patient | 0.18 (0.10-0.33) | 0.40 (0.16-1.01) | 0.11 (0.07-0.18) | 0.30 (0.14-0.65) |

| TB symptoms | 1.16 (1.00-1.35) | 1.65 (1.30-2.08) | 0.65 (0.59-0.73) | 1.13 (0.95-1.34) |

| Otheri or unknown | 1 [Reference] | |||

| MDR TB diagnosisj | 1.11 (0.70-1.77) | 3.42 (1.95-5.99) | 0.48 (0.28-0.82) | 1.05 (0.48-2.28) |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MDR, multidrug resistant; OR, odds ratio; TB, tuberculosis.

aORs are based on multinomial logistic regression analysis. All variables included in the multinomial regression model were selected through all of the following model selection methods: backward elimination, stepwise selection, and forward selection. Diabetes mellitus was forced into the multinomial logistic regression model because of its clinical significance.

bData source: National Tuberculosis Surveillance System, 2009-2013, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

cIncludes multiracial, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native.

dReference category: not residing in a long-term care facility at the time of TB diagnosis.

eIncludes correctional employees and health care workers.

fIncludes HIV test refused, result indeterminate, and test done but results unknown.

gReference category: the absence of any report per risk factor.

hIncludes immunosuppression, post–organ transplantation, and/or on tumor necrosis factor alpha–antagonist therapy.

iIncludes health care worker, employment/administrative test, immigration medical examination, incident laboratory result, and targeted TB testing.

jReference category: absence of an MDR TB diagnosis.

However, some risk factors predicted TB-specific mortality more strongly than they predicted non–TB-specific mortality. When compared with patients with only pulmonary TB, those with both pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB had higher odds of TB-specific mortality (aOR = 1.96; 95% CI, 1.61-2.39) than non–TB-specific mortality (aOR = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.09-1.59). In addition, when compared with those who were HIV negative, those who were not offered HIV testing had higher odds of TB-specific mortality (aOR = 4.77; 95% CI, 3.96-5.76) than non–TB-specific mortality (aOR = 3.41; 95% CI, 2.89-4.02). When compared with patients evaluated for other or unknown reasons, those evaluated because of an abnormal chest x-ray had higher odds of TB-specific mortality (aOR = 1.68; 95% CI, 1.29-2.18) than non–TB-specific mortality (aOR = 1.34; 95% CI, 1.10-1.62; Table 3).

Finally, several risk factors either strongly or weakly predicted TB-specific mortality without predicting non–TB-specific mortality, including MDR TB (vs not; aOR = 3.42; 95% CI, 1.95-5.99), evaluated because of TB symptoms (vs evaluated for other or unknown reasons; aOR = 1.65; 95% CI, 1.30-2.08), and US born (multiracial, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, or unknown race) (vs US-born white; aOR = 1.97; 95% CI, 1.29-3.00; Table 3).

Some risk factors protected against TB-specific mortality. When compared with patients with only pulmonary TB, those with only extrapulmonary TB also had lower odds of TB-specific mortality (aOR = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40-0.69). Compared with patients with only directly observed therapy, those with both directly observed therapy and self-administered therapy had lower odds of TB-specific mortality (aOR = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.16-0.26). Contrasted with those of US-born white race, those of foreign-born Asian race had lower odds of TB-specific mortality (aOR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.53-0.84) and non–TB-specific mortality (aOR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.66-0.94; Table 3).

Discussion

Between 2009 and 2013, >50 000 patients in the United States were reported to have TB, and nearly 1 in 38 patients died from TB. The strongest predictor of TB-specific mortality that was not a predictor of non–TB-specific mortality was MDR TB diagnosis. The strongest predictors of TB-specific and non–TB-specific mortality were age ≥45, end-stage renal disease, immunosuppression, TB diagnosis while living in a long-term care facility, positive HIV status, and not being offered HIV testing.

Patients with TB who were older (particularly ≥65), residents of a long-term care facility at the time of TB diagnosis, not employed or retired, or immunosuppressed were more likely to die of something other than TB than to die of TB. However, patients with TB and an increased odds of TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality included those who had end-stage renal disease, were HIV-positive, or had other or unknown HIV status. We speculate that some of those who died and whose HIV status was other or unknown or to whom testing was not offered may have died before they had the opportunity to be tested for HIV.

Several risk factors predicted TB-specific mortality more strongly than they predicted non–TB-specific mortality. Patients with combined extrapulmonary and pulmonary disease and those with TB symptoms or abnormal chest x-ray as a reason for evaluation all had substantially greater odds of TB-specific mortality than of non–TB-specific mortality. These risk factors imply the presence of more advanced disease, which is more likely to occur when TB diagnosis or treatment has been delayed. The promotion of earlier TB diagnosis and treatment may reduce the incidence of these risk factors and potentially lower the TB-specific mortality rate in the United States.

Some of the risk factors increased the odds of TB-specific mortality while hardly affecting or not affecting the odds of non–TB-specific mortality. This finding was particularly true for those of US-born other/unknown race. The increased risk of TB-specific mortality among these selected US-born racial/ethnic groups may partially be due to TB testing protocols in the United States, making some people in these groups less likely to receive TB testing than their foreign-born peers and potentially resulting in later TB diagnosis and more advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. Additionally, compared with other racial/ethnic groups, Pacific Islanders and American Indians/Alaska Natives have higher rates of certain comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, which are known to increase the risk of adverse outcomes.12–14

Another risk factor that increased the odds of TB-specific mortality without substantially increasing non–TB-specific mortality was diagnosis with MDR TB. It is caused by an organism that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, the 2 most potent and commonly used TB drugs.15 MDR TB can occur in patients who do not take their TB medicine regularly or completely, suggesting that programs that are focused on regular and complete treatment may lower the risk of MDR TB and the increased risk of death associated with it.

In contrast, some risk factors protected against TB-specific mortality. Compared with those who had only pulmonary TB, those with only extrapulmonary TB had significantly lower odds of TB-specific mortality. This finding could have resulted from medical professionals being less likely to identify TB as the cause of death when patients had no evidence of pulmonary TB. We also found a protective effect against TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality for patients with TB treated with both directly observed therapy and self-administered therapy (compared with directly observed therapy alone). This finding is consistent with common clinical practice, in which patients who respond well to TB therapy are often switched from directly observed therapy to self-administered therapy and historically have lower TB-specific mortality. Although contact with a TB patient as the reason for evaluation was also protective against non–TB-specific mortality, it was not protective against TB-specific mortality. However, this finding may have been the result of the study population including a small number of patients who had contact with a TB patient and also died of TB. If the study population had included more of these patients, we might have found a substantial protective effect, consistent with the notion that patients with TB who receive earlier diagnosis and treatment tend to have better outcomes than patients with delayed diagnosis and treatment.2

Although other researchers have reported homelessness as a risk factor for all-cause mortality among patients with TB,4 we did not find an association between past-year homelessness and either TB-specific mortality or non–TB-specific mortality. Because the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System is a passive surveillance system, recent homelessness may have been inadequately reported by patients with TB. Additionally, past-year homelessness might not reflect the duration of homelessness, which may be a better predictor of mortality.

Several previous studies reported results similar to those found in our study. A study by Marks et al conducted with National Tuberculosis Surveillance System data from 1997 to 2005, involving 146 253 patients with TB, found that patients infected with HIV had higher odds of TB diagnosis at death and death during TB treatment than patients who were HIV negative. The study also found that patients who were American Indian/Alaska Native, US born, or diagnosed with MDR TB had higher odds of death during TB treatment than patients who did not have these attributes.4 In a study of 3451 patients in Washington State treated for TB between 1993 and 2005, mortality was independently associated with increasing age, HIV coinfection, and US birth.16 A study of 229 newly diagnosed cases of TB in New York City between 1991 and 1994 also found that all-cause mortality was associated with having MDR TB and HIV infection.2 However, in that study, TB-specific deaths may have driven the observed associations between the 2 predictors and all-cause mortality.

Our findings have various implications for the targeting of TB screening and mortality prevention efforts in patients with TB. Patients in long-term care facilities are particularly concerning given their advancing age, poor baseline health, and residence in a congregate setting. These patients should be regularly screened for TB, and those diagnosed with TB should be carefully monitored during TB treatment. Likewise, patients with TB who are aged ≥45 are also at high risk for TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality and should be closely monitored during treatment. Additionally, efforts should be made to evaluate people in other high-risk subpopulations before they present with TB symptoms or abnormal chest x-rays. Early diagnosis may improve the likelihood that these patients can start treatment before dying of TB and may strengthen the effect of TB treatment once initiated.

Patients with TB and concurrent chronic conditions, such as end-stage renal disease or immunosuppressive disorders, should be closely monitored during TB treatment. Although patients in the United States with MDR TB typically start treatment as soon as they are diagnosed, they also need to be followed closely during treatment to monitor disease progression and evaluate treatment effectiveness. Finally, HIV testing should be offered to all patients with TB and included with TB screening of patients who are at high risk for TB and HIV. In patients with TB who are coinfected with HIV, outcomes can be improved by initiating TB treatment as soon as possible and providing antiretroviral therapy concurrently.17,18

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, by using data from a passive surveillance system, data on some variables may not have been captured adequately or may have been reported more often for people who had access to health care compared with those who did not have access to health care. However, it seems likely that discrepancies in these variables would ultimately affect TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality similarly, thus reducing the likelihood that these discrepancies would have substantially biased the study results. Second, it is possible that the cause of death of patients in our study was not assessed and reported uniformly by different health care providers or jurisdictions, which could have resulted in misclassification of the type of mortality in our analysis. However, most risk factors in our study had directionally similar odds of TB-specific mortality and non–TB-specific mortality. Consequently, even if there was some misclassification, we do not believe that the implications of our study results would change. Lastly, the opportunity for a patient to be treated for TB and the amount of time that a patient actually received TB treatment both likely have substantial effects on TB-specific mortality. We were unable to collect adequate data about duration of treatment to assess it as a risk factor in this analysis, partially because some patients who died of TB were diagnosed with TB at the time of death and thus were never treated. However, we were able to include several other risk factors, such as different types of TB therapy, in the multivariate model that may have reasonably served as proxies for duration of treatment.

Conclusions

TB patients who have MDR TB, HIV infection, end-stage renal disease, immunosuppression, age ≥45, residency in a long-term care facility, TB symptoms as a reason for evaluation, and US-born multiracial, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, or unknown race should be closely monitored before, during, and after treatment to improve their outcomes given their elevated risk of TB-specific and non–TB-specific mortality. Identifying the predictors of TB-specific mortality may help public health leaders and departments determine which population subgroups to target and where to allocate their resources.

Acknowledgments

We thank the surveillance team at CDC’s Division of Tuberculosis Elimination for compiling and managing the current data through the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System. We thank the state and local TB programs for collecting data about TB cases in the United States and reporting them to CDC.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: For Neel R. Gandhi, this work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (grant K24 AI114444; principal investigator: N.R.G.).

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2015. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pablos-Méndez A, Sterling TR, Frieden TR. The relationship between delayed or incomplete treatment and all-cause mortality in patients with tuberculosis. JAMA. 1996;276(15):1223–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kourbatova EV, Leonard MK, Jr, Romero J, Kraft C, del Rio C, Blumberg HM. Risk factors for mortality among patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis at an academic inner-city hospital in the US. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(9):715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marks SM, Magee E, Robison V. Patients diagnosed with tuberculosis at death or who died during therapy: association with the human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(4):465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pascopella L, Barry PM, Flood J, DeRiemer K. Death with tuberculosis in California, 1994-2008. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1(3):ofu090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sterling TR, Zhao Z, Khan A, et al. ; Tuberculosis Trials Consortium. Mortality in a large tuberculosis treatment trial: modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(5):542–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About multiple causes of death, 1999-2015. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html. Accessed January 29, 2017.

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report of Verified Case of Tuberculosis (RVCT) Instruction Manual. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/programs/rvct/instructionmanual.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Law and the Public’s Health. Tuberculosis Control Laws and Policies: A Handbook for Public Health and Legal Practitioners. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10. US Census Bureau. 2009-2013 American Community Survey. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed January 20, 2017.

- 11. SAS Institute, Inc. SAS Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karter AJ, Schillinger D, Adams AS, et al. Elevated rates of diabetes in Pacific Islanders and Asian subgroups: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Diabetes Care. 2013;36(3):574–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burrows NR, Geiss LS, Engelgau MM, Acton KJ. Prevalence of diabetes among Native Americans and Alaska Natives, 1990-1997: an increasing burden. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(12):1786–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker MA, Harries AD, Jeon CY, et al. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact sheet: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB). http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/drtb/mdrtb.htm. Accessed January 29, 2017.

- 16. Horne DJ, Hubbard R, Narita M, Exarchos A, Park DR, Goss CH. Factors associated with mortality in patients with tuberculosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization. Treatment of Tuberculosis: Guidelines. 4th ed Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(8):697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]