Abstract

Trust in health care relationships is a key ingredient of effective, high-quality care. Although the indirect influence of trust on health outcomes has long been recognized, recent research has shown that trust has a direct effect on outcomes of care. Trust is important. However, the research on trust is disparate, organized around differing definitions, and primarily focused on patients’ trust in physicians. Morse’s method of theoretical coalescence was used to further develop and elaborate a grounded theory of the evolution of trust in health care relationships, in the context of chronic illness. This middle-range theory offers a clear conceptual framework for organizing and relating disparate studies, explaining the findings of different studies at a higher conceptual level, and identifying gaps in research and understanding. In addition, the grounded theory is relevant to practice.

Keywords: constant comparison, families, grounded theory, illness and disease, chronic, relationships, theory development, trust

Introduction

There has been long-standing interest in health care relationships, that is, the interpersonal relationships between patients, their family members, and the professionals who provide care. My personal interest in health care relationships began in the early 80s when I conducted phenomenological research with parents of chronically ill children who were experiencing repeated hospitalizations (Robinson, 1984, 1985). A dominant theme in the narratives of their experiences was health care relationships. At the same time, a colleague, Sally Thorne, was conducting research with families with an adult member with cancer. She too found that health care relationships were a dominant influence on the family experience with cancer. At this time in history, dissatisfaction with health care was increasing, which led to interest in health care relationships because of the clear link with level of satisfaction with care. Furthermore, chronic illness was being recognized as presenting different challenges to the health care system and health care relationships than acute illness (Kleinman, 1988). Together, and independently, Thorne and I pursued the theme and developed a theory that explained the development of health care relationships in the context of chronic illness as well as several related concepts/attributes.

Decades later, interest in health care relationships remains strong, and it is now clear that these relationships are integral to quality health care. Not only do health care relationships influence satisfaction with care, but recent research has shown that they also influence health outcomes. There is beginning evidence that health care relationships directly influence health outcomes in the context of chronic illness, particularly mental health outcomes (Lee & Lin, 2010, 2011). Beach, Keruly, and Moore (2006) found that when people with HIV perceive they are known as a person by their physician, this is significantly and independently associated with treatment adherence and undetectable blood levels of HIV RNA. These results support the direct effect of health care relationships on both physical and mental health and reinforce the importance of research in the area.

More specifically, trust, identified as a core facet of effective therapeutic relationships, has received a great deal of attention (Calnan & Rowe, 2006, 2007; Calnan, Rowe, & Entwistle, 2006; Gilson, 2006; Hall, 2006; Hupcey & Miller, 2006; Thorne, Nyhlin, & Paterson, 2000). It is well recognized that trust is particularly important in the context of chronic illness because of enhanced patient vulnerability, uncertainty regarding outcomes, and increased dependence on health care providers over extended periods of time (Calnan & Rowe, 2006). Research on trust has primarily focused on the relationship between patient and physician (Calnan et al., 2006; Hall, 2006); these authors advocate a broader look at patient trust in health care teams, organizations, and systems, and also trust between providers and managers as well as health systems. Calnan and Rowe (2006) identified a further research gap in that research regarding interpersonal relationships between patients and providers has focused on threats to relationships from the patient perspective so attention to the provider perspective is needed.

There are many competing definitions of trust. However, there is some consensus about key elements. Trust is based on a belief in the goodwill of others (Gilson, 2006). There is general agreement among U.S. researchers that the core of patient trust consists of the following in order of importance: loyalty or caring, competency, honesty, and confidentiality (Hall, 2006). There is also agreement that trust is relational, is constructed through interpersonal interaction (Calnan & Rowe, 2006), and depends on a patient’s “overall assessment of the physician’s personality and professionalism, and it is driven fundamentally by the vulnerability of patients seeking care in the compromised state of illness” (Hall, 2006, p. 459). It is important to note the primary importance of the patient’s perception of the caring personality of the physician, which may include such things as sincerity, empathy, altruism, and congeniality (Gilson, 2006). Hall (2006) concludes that trust is highly emotionally based (as opposed to rationally based) and has a strong element of faith. Measures of patient trust have shown trust to be a global phenomenon with a single-factor, unidimensional structure (Hall, 2006).

Some authors argue that, although the importance of trust in health care relationships is not disputed, the pathways between trust and health are unclear and require investigation (Gilson, 2006; Green, 2004; Hall, 2006). Following a review of the evidence, Calnan and Rowe (2006) concluded that there is strong support for the indirect influence of trust on health via its impact on such things as disclosure of relevant information, treatment adherence, and continuity with a provider. The question remains: Is trust a mediator of quality care, which then influences health outcomes (Green, 2004), or does it exert a direct effect on health? Recent research supports the hypothesis that trust in health care relationships directly influences health outcomes, for example, glycemic control and physical health-related quality of life for patients with diabetes (Lee & Lin, 2011).

Still needed in relation to the research into interpersonal trust in health care relationships is an encompassing theory to organize research efforts (Thorne et al., 2000). In addition, attention to family members and their lived experience is required, and this seems to be an unrecognized gap in research. Chronic illness is not the sole realm of patients and providers. Chronic illness is a family experience with all members being influenced by the condition/disease, and the majority of illness care occurs within the family. Given that, from the patient and family perspective, engagement in health care relationships is meant to serve the aim of living well when there is chronic illness, the individualistic focus of research from the patient perspective is not adequate. Furthermore, the one-way focus on patients trusting physicians that predominates in the research will not contribute to effective, socially and financially responsible relationships in the context of chronic illness. Trust in the patient and the family from health care providers is also critical (Calnan et al., 2006; Giambra, Sabourin, Broome, & Buelow, 2014; Williams, McGregor, King, Nelson, & Glasgow, 2005). Reciprocal trust between patients, family members, and the broad array of providers requires attention (Gilson, 2006). Finally, the dynamic nature of trust must be addressed. Given that trust is relational and context-sensitive, perhaps the conceptualization of trust as being on a continuum of high to low (i.e., having levels) or being relatively stable may not be an adequate explanation. Perhaps, as proposed many years ago by Thorne and Robinson (1988a, 1989), and re-visited below, conceptualizing different kinds of trust might have more explanatory utility.

This article presents a theoretical coalescence of previous research from four studies (Table 1) to elaborate and further develop a middle-range theory of trust in health care relationships in the context of chronic illness. Current research is integrated to both support the theory and demonstrate its continuing relevance.

Table 1.

Health Care Relationships as Described From Four Studies.

| Thorne & Robinson, 1988a | Robinson & Thorne, 1984 | Thorne & Robinson, 1989 | Thorne & Robinson, 1988b | Robinson, 1993 | Robinson, 1996 | Robinson, 1998 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three-stage grounded theory of evolving health care relationships in chronic illness Naïve trust  Disenchantment  Guarded Alliance |

Conceptualization of family response within the stage of Disenchantment (interfering behaviors) | Grounded theory of constellation of health care relationships in the stage of Guarded Alliance | Conceptualization of the interaction of trust between provider and patient/family in the stage of Guarded Alliance | Role of providers in the construction of the story of “life as normal” in the context of chronic illness | Conceptualization of provider stance that supports reciprocal trust in the stage of Guarded Alliance | Grounded theory of women’s evolving relationship with chronic illness and helpful nursing interventions |

Method

Theoretical coalescence, a method developed by Morse (in press), was used to formalize connections between several related studies for the purpose of elaborating a richer, more detailed theory of the evolution of trust in health care relationships than has been previously presented. The four studies (Robinson & Thorne, 1984; Robinson, 1993, 1996, 1998; Thorne & Robinson, 1988a, 1988b, 1989) were conducted with families experiencing a broad range of chronic illnesses and used different approaches and methods of analysis, including secondary analysis of two phenomenologically oriented studies, and constant comparative analysis within two grounded theory studies.

The aim of theoretical coalescence is to systematically integrate studies that are theoretically connected to develop a more complex middle-range theory with increased scope to enhance understanding and better inform practice. Theoretical coalescence consists of six steps (Morse, in press):

Identifying significant concepts;

Evaluating the development of the concepts common to each study;

Diagramming the concepts and their positions overall. Mapping each concept in position according to the primary contribution it makes to the overall theory;

Identifying the attributes that are common to each example of the concepts. This provides some indication of how the concepts interlock and share characteristic across conceptual boundaries;

Develop analytic questions about the nature of the overarching concept and the answers in each study;

Diagram and write the middle-range theory.

The Evolution of Trust in Interpersonal Health Care Relationships in the Context of Chronic Illness

The following represents the complex evolution of trust in interpersonal health care relationships within the context of chronic illness, from the family perspective. By chronic illness, I mean a health condition that cannot be “fixed” or cured. The term illness is used to distinguish the family experience with sickness from the medical perspective of sickness, which is termed disease (Kleinman, 1988). It is critical to understand that the family goal in the situation of chronic illness is to live well and to have as normal a life as possible (Thorne & Robinson, 1988a; Robinson, 1993, 1998). So, over time, health care relationships are judged in relation to how they serve this goal. The other important aspect of chronic illness is that when chronic illness enters the family, it is initially viewed as an unwelcome intruder, but over time and to varying degrees, it becomes accepted as a family member (Robinson, 1998). Illness, as a family member, has a relationship with all other family members, not just the person with the diagnosis (Robinson, 1998). This means that the interpersonal relationships with health care providers that are central to living well encompass and influence each family member and the family as a whole. Health care relationships are not just relationships between patients and providers.

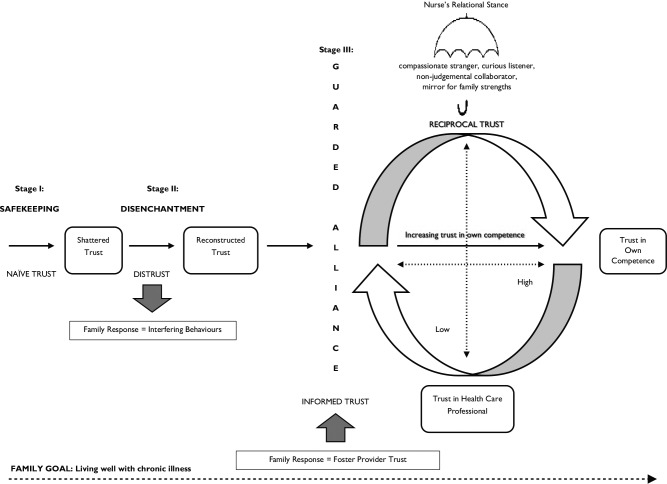

The “backbone” of the middle-range theory is composed of three distinct relationship stages configured around three different kinds of trust: naïve trust, distrust, and informed trust (adapted from Thorne & Robinson, 1988a; Figure 1). Underpinning each stage are beliefs and interactional patterns between patient/family and providers. Wright and Leahey (2013) note that interactional patterns can be identified in most relationship issues. These patterns are circular, where the reciprocal behaviors of both members of the dyad serve to grow and sustain the pattern, which makes them challenging to alter.

Figure 1.

Evolution of trust in health care relationships.

Stage 1: Safekeeping (Renamed From Robinson & Thorne, 1984; Thorne & Robinson, 1988a)

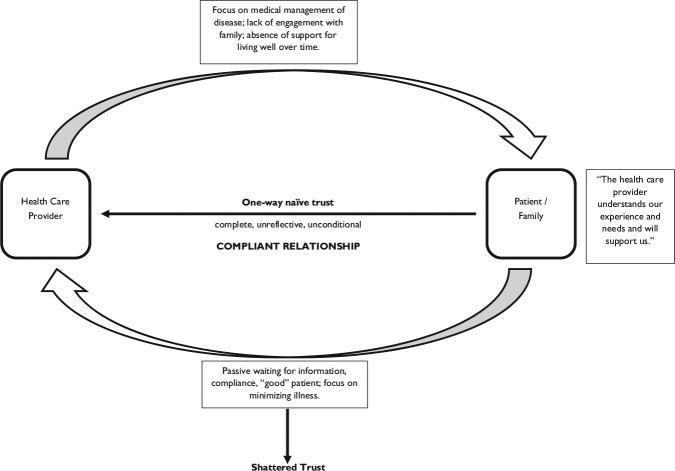

Safekeeping was the beginning relationship stage between patient/family and providers, and is characterized by naïve trust. We called the trust in this relationship stage “naïve” because it was based on unrealistic beliefs and expectations. In this stage, patients and family members engaged with providers in hopeful expectation of being actively and meaningfully involved in coming to understand and manage the health problem. They were new in their relationship with illness, and both vulnerability and uncertainty were high. At this point, family members viewed illness as an unwelcome intruder that they hoped the medical system would manage (Robinson, 1988). They did not know or understand the illness, and many initially resisted gaining a better understanding. However, they believed that health care providers did know the problem and both understood and respected the family experience of illness. So they placed their ill member wholly in the safekeeping of the professionals.

Naïve trust was all encompassing and included both providers and the health system in which they worked. This trust “was based on the family’s [belief] that its perspective was a shared or commonly held perspective with the professionals who cared for the ill member” (Thorne & Robinson, 1988a, p. 296). Family members expected that all providers would behave in accord with an implicit mutual understanding of patient and family best interests. They expected to be acknowledged and respected as the primary care providers of their sick member on a day-to-day basis, and that “care would be collaborative and cooperative with decisions being mutually negotiated” (p. 297). Based on the underpinning belief about a shared perspective, supported by unconditional naïve trust, family members waited passively for their expectations to be met. They were “good” family members, compliantly doing whatever was asked of them, quietly and patiently waiting for acknowledgment, engagement, and most important, information.

However, as previously explained, naïve trust began to erode as families interacted with health care professionals:

It took some time in the experience before family members began to understand that health care professionals held a different perspective and, as a result, had different expectations of their encounters. Family members learned that the long-term nature of their chronic illness experience was often disregarded as was their involvement and expertise about the ill person and illness management . . . . Discrepancies arose between family members’ views and providers’ views about the best interests of the sick member. The professional health care system is organized around the medical model of disease so that management focuses on intervening with regard to the disease process. (Thorne & Robinson, 1988a, p. 297)

This contrasted sharply with the family’s aim of minimizing the effects and consequences of illness to live as normal a life as possible (Robinson, 1993). One mother of a child with a progressive neurological disorder who was confined to a wheelchair eloquently captured the discrepant perspectives:

He [the doctor] just, he said to me “I want to give him nice straight feet.” He said “Make him beautiful straight feet.” And I said, “Well, is he going to walk with them?” “Oh no, he’ll never walk.” And I said, “What’s . . . . what’s the good of doin’ it you know.” And then he said, “Well to give him nice straight feet.” (Thorne & Robinson, 1988a, p. 297)

Thus, family members learned that their priority of living well with illness was often preempted by disease management or competing provider concerns such as education and research. Over time, expectations were unmet, and it became clear that compliance and passive waiting were unproductive. Frustration mounted, and trust eroded. The unconditional nature of naïve trust based on faulty beliefs could not be sustained and trust shattered along with the idea that the ill family member was safe in the health care system and hands of providers. For some families, naïve trust was slowly worn down over time, whereas, for others, a single dramatic incident resulted in the break. The reciprocal interaction pattern that held the problematic relational dynamic in place is depicted in Figure 2. Please note that the pattern is depicted from the family perspective.

Figure 2.

Interactional pattern in safekeeping.

The negative dynamic is well described by Dickinson, Smythe, and Spence (2006) in their research with parents of chronically ill children. The parents in this study were confused and frustrated by being “thrown” into a web of relationships with multiple providers who paternalistically determined resources and services without consultation or negotiation. Relationships were characterized as turbulent, unpredictable, and the sense of being “thrown” as violent. Care occurred that did not fit with family life, and parents lacked control. However, they persevered for their children.

Given the changing health care system, researchers (Rowe & Calnan, 2006) postulate that more informed recipients of care may take a consumer approach to their health care relationships. This might mean the stage of Safekeeping based on naïve trust is no longer relevant. We also wondered whether more informed family members might avoid the pitfall of basing trust on faulty beliefs regarding the way the health system is organized but this did not prove to be the case. It is important to note that we had health care professionals as participants in the studies on which the initial theory was based and they too entered their health care relationships with naïve trust. Indeed, there is current evidence to support the continuing existence of naïve trust in health care relationships. Robb and Greenhalgh (2006), reporting on a grounded theory study of interpreted health care encounters, found evidence of what they term hegemonic trust.

Hegemonic trust is unreflexive, taken-for-granted, and unconditional with lack of consideration of any alternative, that is, no choice is involved (Robb & Greenhalgh, 2006). Some authors argue that trust involves an element of risk (Entwistle & Quick, 2006), but this was not the case in naïve trust where risk was not recognized. Furthermore, Robb and Greenhalgh assert,

Not only does the patient have no choice but to trust the clinician, but his or her propensity to trust has been shaped by an imperfect system. The power of the medical profession rests not only on expert knowledge and the miraculous nature of that knowledge but on the increasingly powerful social position of the medical profession. (p. 436)

This seems to capture the situation of a family’s early relationship with chronic illness where there is high vulnerability and uncertainty coupled with recognition of the continuing need for care accompanied by lack of knowledge about the health problem. Patients and family members need to trust health care providers. Although naïve trust may ease uncertainty and initially act to calm the situation, the dangers of blind trust are well recognized (Calnan & Rowe, 2006). For the participant patients and family members, blind trust was risky because it invited them to be passive. Eventually, the naïve trust broke under the weight of unmet expectations. This is supported by longitudinal research that found trust can decrease over time in response to a new understanding that physician behaviors may be influenced primarily by financial concerns rather than patient best interests (Hall, 2006).

Shattered trust

Sometimes when something breaks, it can be healed and put back together, but in the case of naïve trust, this was not the case. Once family members experienced the markedly different perspectives of providers and came to understand that their belief about implicit mutual understanding was faulty, naïve trust was broken beyond repair. Hall’s (2006) work in developing measures of trust offers one explanation for why naïve trust breaks and shatters. Hall found that specific dimensions of trust in one’s physician cannot be isolated but contribute to global trust, which is unidimensional, comprised of a single factor. Hall concluded that trust is highly emotionally based (as opposed to rationally based) and has a strong element of faith. Shattered trust led to the next relationship stage of Disenchantment.

Stage 2: Disenchantment

Although family members experienced frustration and growing concern with the relationships they had with health care providers in the stage of Safekeeping, this was magnified in the stage of Disenchantment, where naïve trust was replaced by distrust. They had learned that the family’s experience of living with chronic illness and their priority of living well were often not in alignment with the system’s focus on addressing immediate, acute problems within the long-term disease/condition or other concerns such as medical education and research. A father of a child with life-threatening allergies, eating problems, and asthma who had spent 14 of his 16 months in hospital put it this way:

The hospital is concerned with any immediate illness that is going on with him, that he’s not functioning at the time as well as he could be . . . . But as far as trying to set out a diet or a life-style for him, to pattern him after, they’re more concerned about when things are already wrong with him . . . . As far as seeing what they can do to develop him like a normal kid—they don’t seem to do much in that aspect . . . . Somewhere along the line they’ve got to start preparing him for his future and giving us some kind of idea about what we can do. (Robinson, 1993, p. 22)

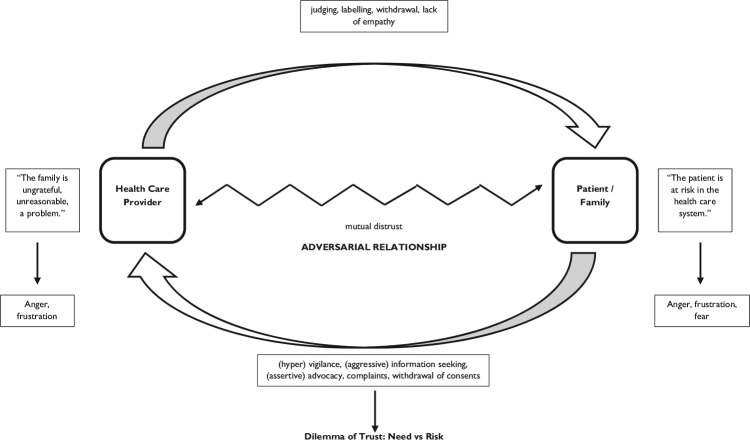

As a result of the serious discrepancy in perspectives and unmet expectations, family members came to believe that their ill member was at risk in the health care system, which generated fear and anger in addition to extreme frustration. Family members took action to protect their vulnerable family member, but were hampered by lack of knowledge and skills arising from the absence of information they had expected but did not receive. Their efforts to influence the care of their ill member were often assertive or even aggressive and health care relationships became adversarial. In hindsight, participants judged their actions to be ineffective or even counterproductive but, at the time, they were uninformed and propelled by fear, anger, and distrust. Protective actions included such things as tearing up consent forms, restricting provider access to the ill member, vigilant supervision of providers, and emotional outbursts.

The problematic interactional pattern that characterized the stage of Disenchantment is depicted in Figure 3 (based on Robinson & Thorne, 1984). Provider response to the family behaviors that may be interpreted as irrational, aggressive, ungrateful, or interfering can be seen to reinforce the sense of being “at risk” in the health care system and to support distrust because they are distancing.

Figure 3.

Interactional pattern in disenchantment.

An example of the negative relational dynamic in this stage can be found in Dickinson and colleagues’ (2006) research with parents of chronically ill children and their providers. Parents engaged in a process of “going around” to multiple providers as they persistently sought information as a way to gain control and manage uncertainty. Providers were aware of this process and interpreted it as playing a game of pitting one provider against another. Although providers recognized the behavior as a product of parental distress, they viewed it as manipulative and believed it was destructive to relationships and needed to be controlled.

In the stage of Disenchantment, family members were caught in a dilemma of trust. They viewed their ill family member to be at risk if they did not step in and attempt to influence the experience, but, at the same time, they were acutely aware of their continuing dependence on professional providers and that their actions might negatively affect necessary provider goodwill. This dilemma created even greater distress and anxiety. The emotional chaos was untenable, but it was impossible to return to naïve trust. Informant family members were emphatic that in the situation of chronic illness, associated with the long-term need for health care, some measure or kind of trust in health care professionals was essential. The need for care, the need to trust, and the need to move beyond the emotional chaos of Disenchantment were powerful synergistic forces enabling the active construction of a different kind of trust in the next stage of Guarded Alliance.

Stage 3: Guarded Alliance

Patients and family members fully understood that chronic illness required continuing professional care, and they explained that they needed to have some trust in selected providers. As Entwistle and Quick (2006) note, “trust facilitates co-operation and allows people to inhabit a less threatening world” (p. 400). Patients’ and family members’ need to trust was driven by a sense of vulnerability (Hall, 2006) and uncertainty but was associated with perceived risk. In this stage, a new kind of trust called “informed trust” was constructed based on altered expectations of providers, a belief that the health care system is inherently limited or even flawed, and an understanding that family must be actively involved in care to insure the best possible outcomes for the ill member and family as a whole. Informed trust was based on a more realistic rather than naïve understanding of their own responsibilities, their own strengths and limitations, and the strengths and limitations of providers. Health care relationships involved an alliance, but it was conditional and guarded.

In the stage of Guarded Alliance, family members established relationships with chosen providers based on human characteristics that were uniquely meaningful. For example, the provider might be someone who participated in community activities such as children’s sports activities, or it might be someone who belonged to a particular political party or club. Family members were concerned about establishing a relationship in which providers were interested in their ill member and their situation so they actively engaged in strategies to diminish emotional distance and generate a personal connection. These strategies included gift giving, inquiries into the health and well-being of providers, and acknowledgment of the challenges involved in providing care. Concern about whether providers are motivated to apply their knowledge and skills in the best interests of the patient have been identified in the literature on trust. For example, Gilson (2006) notes that patient and family member trust in providers is associated with expectations regarding provider ethics, integrity, and motivation as well as competence. In addition, others have suggested that motivations are as significant to trust as are results (Hall, Dugan, Zheng, & Mishra, 2001).

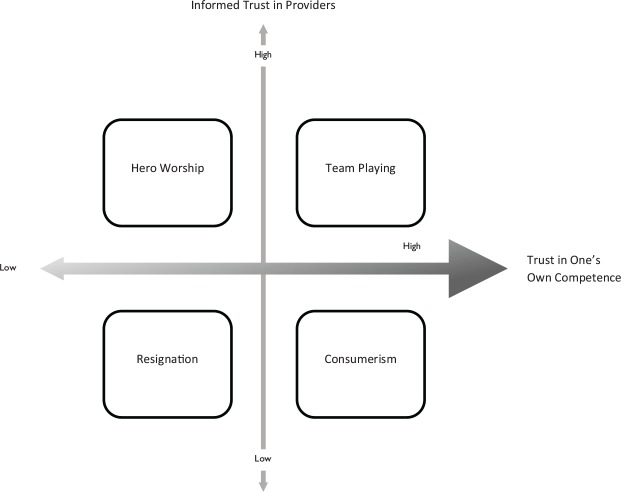

Just as family members actively engaged to reshape their relationships with providers, they engaged in their relationship with illness by becoming more informed and competent in managing illness problems. There are four relationship types in Guarded Alliance that revolve around two dimensions of trust: trust in providers and trust in one’s own ability to manage illness (Figure 4, adapted from Thorne & Robinson, 1989).

Figure 4.

Trust in guarded alliance.

Source. Adapted from Thorne & Robinson, 1989.

The four relationship types of Hero Worship, Resignation, Consumerism, and Team Playing are well described elsewhere (Thorne & Robinson, 1989). In hero worship, there is high trust in the provider who is the designated “hero,” while there is low trust in one’s own competence to manage illness problems. Care is placed in the hands of the selected provider and a measure of ease and security is attained. However, this dependent relationship is precarious because the Hero is placed on a pedestal and sometimes falls off or perhaps moves away or retires, which places individuals at risk because they have not developed trust in their competence to solve illness problems on their own and may have difficulty finding another hero. This relationship type resembles the Safekeeping relationship, but trust is informed rather than naïve, rests on a selected provider, and does not encompass trust in the health care system. Hero worship required little work for patients and families because problem solving and decision making were placed in the provider’s hands.

In the resignation relationship type, there is low trust in providers and low trust in one’s own competence to manage illness problems. Participants had little confidence that anyone could make a positive difference to their illness experience, and some withdrew from care for a time. Others maintained connection with providers so that necessary help would be available if the illness changed. This relationship type resembles Disenchantment in that it was characterized by hopelessness and despair but lacked anger and aggression. For some participants, relationships characterized by resignation allowed a welcome rest from actively engaging in health care relationships with providers and was effectively achieved at a time when the chronic illness was relatively stable.

In the consumerism type of relationship, there is low trust in providers but high trust in one’s own competence to manage illness problems. This relationship put patients and family members squarely in the driver’s seat of their own health care and involved taking responsibility for problem solving and decision making. Health care relationships in this pattern were a means to getting desired care. Participants reported being very creative in communicating with providers to achieve their preferred result, and while they described themselves as being manipulative and noncompliant, they perceived that they convinced health care professionals otherwise. It was interesting to note that providers would not likely know they were in a consumer relationship because participants presented as “good,” compliant, and attentive patients and family members and did not take an overtly demanding approach. The downside to this relationship type was that it took a great deal of work, but it also offered a high level of control.

In the team playing type of relationship, there is high trust in providers and high trust in one’s own competence to manage illness problems. This was a highly desired relationship type but required finding a provider who was willing to engage as a team member, and this was sometimes difficult. For example, some participants who had a consumerism relationship reported that they were seeking a team playing relationship but could not find a provider who was willing to participate as an equal partner. The team playing relationship type was built on mutual understanding of and respect for the strengths and weaknesses of all members on the team. Problem solving and decision making were collaborative and negotiated. Responsibility for the relationship and illness management were shared. The team playing relationship is most closely aligned with patient- and family-centered care where the patient and family member perceive they are known as persons by their providers (Beach et al., 2006). Although this is a highly valued kind of relationship, it takes a great deal of work on two levels. First, patients and family members need to continually develop their competence to deal with illness problems, and second, they must often put a lot of energy into creating an effective partnership. A good example of this can be found in the research of Giambra and colleagues (2014). These researchers developed a grounded theory of shared communication from the perspective of parents of technologically dependent children that highlights the extensive work parents undertake to explicitly join with nurses and create a partnership based on mutual understanding of the child’s plan of care.

Providers’ trust in patients and family members

It can be seen that each relationship type had advantages and disadvantages. Participants reported that they had different relationships with different providers. Some reported that they had different relationships with the same provider over time, for example, moving between team playing and hero worship in relation to dramatic changes in the illness that meant trust in their own competence shifted for a time. It must be noted that competence was situational and responsive to the changing demands of chronic illness so it required continual adaptation. Not all of the relationship patterns were equally effective in terms of supporting the goal of living well with chronic illness. Although providers tend to focus on promoting the vertical dimension of developing or maintaining trust in providers, what proved more powerful to living well was the horizontal dimension of trust in one’s own competence. Participants who had high trust in their own competence were more successful at living well because, regardless of the situation with their providers, they could count on themselves. Research shows that the more engaged patients are in their own care, the better their health outcomes and the better their health care experiences (Hibbard & Greene, 2013). Engagement, or activation as Hibbard and Greene (2013) term it, can be increased, and these authors emphasize the importance of attending to patient engagement in all efforts to improve the effectiveness of care.

The key ingredient that fostered both participants’ trust in their own competence and trust in providers was providers’ expressions of trust in patients’ and family members’ ability to know the illness, know themselves, and make sound decisions with regard to their health (Thorne & Robinson, 1988b). Participants described sound decision making as a flexible and context-sensitive process of making, sharing, or delegating decisions in accord with what best supported living well. Trust from providers was a particularly meaningful and powerful influence on health care relationships because participants experienced it as affirming and validating. One participant explained it this way:

I overheard him [the internist] talking to the nurse, and he said, “Look, you want to know about myasthenia, you ask her [referring to the patient] . . . . She knows more about it than I do.” I loved it . . . I have such confidence in them now that I know I can trust them! (Thorne & Robinson, 1988b, p. 785)

Trust from providers generated participant trust on multiple levels—trust in the provider and trust in oneself. Reciprocal trust between patients, family members, and providers was the most potent factor explaining movement along both dimensions of trust in Guarded Alliance and characterized team playing. Reciprocal trust enabled an effective working relationship where providers got the information they needed to enable them to make good decisions, and patients and family members were open to the provider’s recommendations. The importance of provider expressions of trust is supported by Williams and colleagues (2005) who found that physician support for patient autonomy enabled a sense of competence that was significantly related to decreased depressive symptoms and increased satisfaction and glycemic control.

Although research into trust in interpersonal health care relationships often focuses on patients’ trust in physicians, in effective relationships, trust is not a one-way street. Instead, it requires that “both parties demonstrate behaviours that allow each to trust the other” (Gilson, 2006, p. 362). It is important to reiterate that once trust is shattered, it must be earned on a relationship-by-relationship basis. Gilson (2006) notes that trust is “resilient in the face of violation [but it] is difficult to re-construct once broken” (p. 362). The next two sections will address the behaviors that foster reciprocal trust.

Provider behaviors that fostered trust and competence

Families identified four aspects to what I have termed a relational stance that fosters trust and invites healing of significant chronic health problems (Robinson, 1996). These four aspects are curious listener, compassionate stranger, nonjudgmental collaborator, and mirror for family strengths. The curious listener balanced careful listening with the asking of good questions. A good question is one that invites reflection about the concern at hand. The compassionate stranger balanced the tension between connectedness and detachment in the relationship by being close enough to be touched by the family’s experience but distant enough to be objective and unburdened by the family’s suffering. Expressions of compassion were deeply appreciated as were new ideas regarding the concerns at hand because the participant families were stuck in patterns of managing that were not effective. The nonjudgmental collaborator avoided negative judgments while working with the family to achieve its goals in living well. All of the families had experienced being negatively judged, blamed, and criticized by providers and were particularly sensitive to this destructive dynamic. As previously identified, negative judgments were a common experience in the stage of Disenchantment. The participant families were highly competent and were looking for a team playing relationship in which they would be supported to help themselves. The mirror for family strengths was a particularly powerful aspect because the participant families were aware that providers usually attended to problems and focused their efforts on correcting them. A focus on strengths, abilities, and competencies was not usual professional behavior. The families were explicit about what providers did that was helpful. They offered commendations: situation-specific, individualized observations of individual and family strengths or competencies. This echoes what the participants in our earlier study (Thorne & Robinson, 1988b) told us promoted, recognized, and supported their competencies, which, at that point, we called affirmations. As one man commented,

I felt good because I was in control of myself a bit more. They trusted me to do these things too, and they even told me that only certain people get to be put on those things [home total parenteral nutrition]. You know, I started to appreciate that they really did think that I knew something about it. (Thorne & Robinson, 1988b, p. 785)

Commendations have received attention in family nursing (Bohn, Wright, & Moules, 2003; Limacher & Wright, 2003, 2006; McElheran & Harper-Jaques, 1994) and have been noted to support collaborative health care relationships. This theoretical coalescence adds to the understanding of how commendations work by highlighting the link to trust and to reciprocal trust.

Researchers investigating the relational needs of parents of children with Type 1 diabetes (Ayala, Howe, Dumser, Buzby, & Murphy, 2014; Howe, Ayala, Dumser, Buzby, & Murphy, 2012) found that reciprocal trust was essential to the alliance parents wanted with their children’s providers. The findings highlight the importance of providers asking good questions, being emotionally involved, knowing the child and family not just the illness, picking up on problems or concerns, inviting open communication, tailoring the plan of care to the realities of family life, becoming the “Captain of the Ship” when the situation changed and parents did not know what to do, offering expert advice, and responding compassionately to high emotions. Howe and colleagues (2012) offer many helpful examples of supportive provider behaviors when the goal is to create an effective partnership.

Dibben and Lean (2003) also give clear examples of provider behaviors that promote interpersonal trust. Although their research was aimed at achieving treatment compliance rather than competence, strategies such as offering commendations, focusing on strengths, and joining with the patient are all consistent with inviting patient involvement and increasing competence.

Patient and family strategies aimed at generating trust from selected providers

Participants described a variety of strategies to encourage providers to trust them, including providing concise information about the illness and treatment, use of medical language, careful use of the health care system and resources, withholding information that might be judged negatively such as noncompliance or use of alternative treatment modalities, and clear, explicit requests for assistance (Thorne & Robinson, 1988b). Efforts were made to reduce relational distance and establish a human connection in the hope that this would invite provider interest in them and their situation such a making jokes, bringing small gifts, and inquiring about the well-being of the provider. These strategies were carefully developed competencies that contributed to living well with the chronic health problem because they supported an effective relational partnership.

Conclusion

The process of theoretical coalescence has enabled the development and elaboration of a theory of trust in health care relationships in the context of chronic illness. Examples of current research were used to demonstrate the relevance and utility of the theory in relation to both explaining and positioning disparate studies. This theory offers a way to conceptualize the spectrum of research on trust in health care relationships, the relationship between studies, and the gaps that require further investigation. In addition, the grounded theory offers a way of seeing the complexity of trust and how it evolves in health care relationships that are useful for informing practice.

Acknowledgments

The article processing charge was waived by GQNR.

Author Biography

Carole A. Robinson, PhD, RN, is a professor in the School of Nursing at the University of British Columbia in Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ayala J., Howe C., Dumser S., Buzby M., Murphy K. (2014). Partnerships with providers: Reflections from parents of children with type 1 diabetes. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 36, 1238–1253. doi: 10.1177/0193945913518848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach M. C., Keruly J., Moore R. D. (2006). Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn U., Wright L. M., Moules N. J. (2003). A family systems nursing interview following a myocardial infarction: The power of commendations. Journal of Family Nursing, 9, 151–165. doi: 10.1177/1074840703251969 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan M., Rowe R. (2006). Researching trust relations in health care: Conceptual and methodological challenges—An introduction. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 20, 349–358. doi: 10.1108/14777260610701759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan M., Rowe R. (2007). Trust and health care. Sociology Compass, 1, 283–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00007.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan M., Rowe R., Entwistle V. (2006). Trust relations in health care: An agenda for future research. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 20, 477–484. doi: 10.1108/14777260610701830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibben M. R., Lean M. (2003). Achieving compliance in chronic illness management: Illustrations of trust relationships between physicians and nutrition clinic patients. Health, Risk & Society, 5, 241–258. doi: 10.1080/13698570310001606950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson A. R., Smythe E., Spence D. (2006). Within the web: The family-practitioner relationship in the context of chronic childhood illness. Journal of Child Health Care, 10, 309–325. doi: 10.1177/1367493506067883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle V. A., Quick O. (2006). Trust in the context of patient safety problems. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 20, 397–416. doi: 10.1108/14777260610701786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giambra B. K., Sabourin T., Broome M. E., Buelow J. (2014). The theory of shared communication: How parents of technology-dependent children communicate with nurses on the inpatient unit. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29, 14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L. (2006). Trust in health care: Theoretical perspectives and research needs. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 20, 359–375. doi: 10.1108/14777260610701768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. (2004). Is trust an under-researched component of healthcare organisation? British Medical Journal, 329, Article 384. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38174.496944.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. A., Dugan E., Zheng B., Mishra A. (2001). Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Quarterly, 79, 613–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. A. (2006). Researching medical trust in the United States. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 20, 456–467. doi: 10.1108/14777260610701812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard J. H., Greene J. (2013). What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Affairs, 32, 207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe C. J., Ayala J., Dumser S., Buzby M., Murphy K. (2012). Parental expectations in the care of their children and adolescents with diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27, 119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupcey J. E., Miller J. (2006). Community dwelling adults’ perception of interpersonal trust vs. trust in health care providers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01386.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. (1988). The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. Y., Lin J. L. (2010). Do patient autonomy preferences matter? Linking patient-centered care to patient-physician relationships and health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 1811–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. Y., Lin J. L. (2011). How much does trust really matter? A study of the longitudinal effects of trust and decision-making preferences on diabetic patient outcomes. Patient Education & Counseling, 85, 406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limacher L. H., Wright L. M. (2003). Commendations: Listening to the silent side of a family intervention. Journal of Family Nursing, 9, 130–150. doi: 10.1177/1074840703251968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limacher L. H., Wright L. M. (2006). Exploring the therapeutic family intervention of commendations: Insights from research. Journal of Family Nursing, 12, 307–331. doi: 10.1177/1074840706291696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElheran N. G., Harper-Jaques S. R. (1994). Commendations: A resource intervention for clinical practice. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 8, 7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M. (in press). Analyzing and constructing the conceptual and theoretical foundations of nursing. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Robb N., Greenhalgh T. (2006). “You have to cover up the words of the doctor”: The mediation of trust in interpreted consultations in primary care. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 20, 434–455. doi: 10.1108/14777260610701803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. A. (1984). When hospitalization becomes an “everyday thing.” Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 7, 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. A. (1985). Parents of hospitalized chronically ill children: Competency in question. Nursing Papers, 17(2), 59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. A. (1993). Managain life with a chronic condition: The story of normalization. Qualitative Health Research, 3, 6–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. A. (1996). Health care relationships revisited. Journal of Family Nursing, 2, 152–173. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. A. (1998). Women, families, chronic illness, and nursing interventions: From burden to balance. Journal of Family Nursing, 4, 271–290. doi: 10.1177/107484079800400304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. A., Thorne S. E. (1984). Strengthening family ‘interference.’ Journal of Advanced Nursing, 9, 597-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R., Calnan M. (2006). Trust in health care: Developing a theoretical framework for the “new” NHS. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 20, 376–396. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14777260610701777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. E., Nyhlin K. T., Paterson B. L. (2000). Attitudes toward patient expertise in chronic illness. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 37, 303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. W., Robinson C. A. (1988a). Health care relationships: The chronic illness perspective. Research in Nursing & Health, 11, 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. E., Robinson C. A. (1988b). Reciprocal trust in heatlh care relationships. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 13, 782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. E., Robinson C. A. (1989). Guarded alliance: Health care relationships in chronic illness. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 21, 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G. C., McGregor H. A., King D., Nelson C. C., Glasgow R. E. (2005). Variation in perceived competence, glycemic control, and patient satisfaction: Relationship to autonomy support from physicians. Patient Education & Counseling, 57, 39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright L. M., Leahey M. (2013). Nurses and families: A guide to family assessment and intervention (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. [Google Scholar]