Abstract

The marketing approval of genetically engineered hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) as the first-line therapy for the treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID) is a tribute to the substantial progress that has been made regarding HSC engineering in the past decade. Reproducible manufacturing of high-quality, clinical-grade, genetically engineered HSCs is the foundation for broadening the application of this technology. Herein, the current state-of-the-art manufacturing platforms to genetically engineer HSCs as well as the challenges pertaining to production standardization and product characterization are addressed in the context of primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs) and other monogenic disorders.

Keywords: hematopoietic stem cells, manufacturing, lentiviral vectors, gamma-retroviral vectors, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, primary immunodeficiency disease, SCID-X, ADA-SCID, WAS, LMO2

Main Text

Since the discovery of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the 1960s, HSC transplantation has become a curative clinical approach for an ever-increasing number of indications in oncology and regenerative medicine due to the unique self-renewal potential of HSCs.1 Given the experience with HSC transplantation, the genetic modification of autologous HSCs is an attractive therapeutic option for patients with monogenic disorders who lack a suitable HSC donor. By now, nearly two decades of clinical experience with the use of genetically modified autologous HSCs have been accumulated in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs). Although this treatment modality has proven to be efficacious for the treatment of PIDs such as severe combined immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID), X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID), and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS), many challenges remain for the treatment of diseases such as chronic granulomatous disease (CGD)2, 3, 4 or hemoglobinopathies.5 Nonetheless, the recent approval of engineered HSCs for the treatment of patients with ADA-SCID provides an unprecedented proof of concept that paves the way for future applications.6 The genetic engineering and manufacturing processes are critical for the broadening of HSC-based therapies. Here, we review the current status of HSC transduction in the context of the largely successful clinical applications for the treatment of PIDs (X-SCID, ADA-SCID, WAS, and CGD) as well as other monogenic disorders such as adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) and metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD).

Manufacturing of Genetically Engineered HSCs

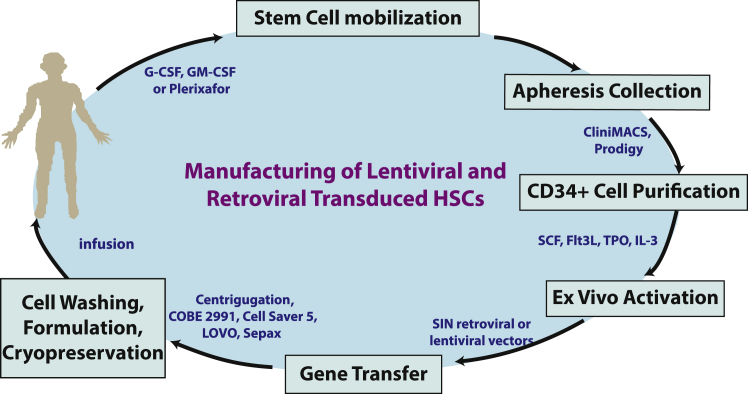

For patients with suitable donors, allogeneic HSC transplantation (HSCT) is accepted as the overt first line of therapy with proven efficacy in patients with immunodeficiency diseases such as ADA-SCID, X-SCID, and WAS. For patients without matched donors, clinical studies have demonstrated long-lasting and curative effects of genetically engineered autologous HSCs with the bona fide elimination of the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD).2, 4, 7 The survival rate in patients with ADA-SCID has reached 100%, surpassing the efficacy of HSCT with fully matched donors.8 The successful manufacturing of genetically engineered HSCs is the basis for this unparalleled positive outcome. Processes ranging from HSC collection, CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor stem cells (HPSCs) selection, ex vivo activation/expansion, and genetic engineering of HSPCs must fulfill their own specific requirements to warrant a suitable clinical-grade product (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Major Steps in Retroviral and Lentiviral Vector-Transduced HPSC Cell Manufacturing Process

Examples of available technologies and devices.

HPSC Collection

The primary sources for autologous hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells (HPSCs) are either bone marrow (BM) or mobilized peripheral blood (MPB). Several clinical trials have established that a minimum of 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg body weight is needed for successful engraftment, and 5–10 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg body weight is desirable for faster engraftment in the autologous setting.9, 10

In their quiescent state, HSPCs are tethered to osteoblasts, stromal cells, and the extracellular matrix in the BM stem cell niche. BM has been collected and infused into patients for more than 60 years.11 When BM is chosen as the collection source, a surgical procedure is required. Patients undergo general or regional anesthesia and BM is collected through a needle inserted into the rear of the hip, which contains a large concentration of blood stem cells. When mobilized peripheral blood is chosen as the HSC source, HSCs need to be released from their BM niche to allow them to migrate into the bloodstream. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three agents for the mobilization of HSPCs: two hematopoietic growth factors, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF); and a small bicyclam molecule, Plerixafor (also known as AMD3100). G-CSF is the first-line treatment for HPSC mobilization and has been shown to reduce neutropenia-related infection and enhance post-transplant myeloid recovery.12 GM-CSF is less efficacious in mobilizing HSPCs13 and considered a salvage mobilization regiment in patients who failed G-CSF mobilization. Plerixafor inhibits the CXCR4-SDF1 interaction within the BM microenvironment and induces rapid mobilization of stem cells.14 It has recently been shown that a combination of Plerixafor and G-CSF results in enhanced mobilization of HSPCs with greater repopulating potential in donors with multiple myeloma,15 non-Hodgkin lymphoma,16 and thalassemia,17 suggesting that distinct HPSC populations may be liberated from their specific niches by two different mechanisms. The COBE Spectra is the most commonly used platform for leukapheresis. The Spectra Optia system (Spectra’s next generation), Haemonetics’ MCS+, Fresenius Kabi’s COM.TEC, and Fenwal’s Amicus became more recently available for leukapheresis collection. The Spectra Optia and the Spectra systems have been shown to generate comparable HPSC products, yielding the least amount of red cell contamination, whereas the Amicus system removes fewer platelets from the donor.18, 19, 20, 21

CD34+ HPSC Purification

CD34 has been used for the past 40 years as a surrogate marker for hematopoietic progenitors enriched with repopulating stem cells. Positive selection of CD34+ cells from BM or MPB is the method of choice for both autologous and allogeneic transplantations. Several immunoselection devices, including Ceparte, Isolex 300i, and CliniMACS have been used in the past for CD34+ cell selection.22 Currently, the Miltenyi CliniMACS Plus system together with the automated CliniMACS Prodigy are the only methods available for this procedure. CliniMACS offers the advantage of semiautomatic separation of magnetically labeled progenitor cells from both BM and MPB. It has been reported that a medium recovery of 71% and medium purity of 97% of CD34+ cells, with a median of 0.04% residual CD3+ cells could be achieved from either BM or MPB by using the CliniMACS device.23 Similar results were obtained with the automated CliniMACS Prodigy, although CD34+ cell recovery and depletion of CD3+ cells may be lower than with the semi-automated CliniMACS Plus instrument.24, 25

When using BM as starting material for CD34+ cell selection, isolation of BM mononuclear cells (BMMCs) by standard Ficoll gradient density centrifugation with the COBE 2991 cell washer or a regular centrifuge26, 27 is the first step toward HPSC purification. Both the isolated BMMCs and the MPB are then washed, resuspended in wash buffer, blocked with human gamma globulin, and incubated with CliniMACS CD34 reagent. The magnetically labeled CD34+ cells are subsequently isolated.23 CD34+ cells isolated from either BM or MPB have been successfully used in HSC gene therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Transduction Parameters for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Gene Therapy Clinical Trials in Patients with Primary Immunodeficiencies and Metabolic Diseases

| Disease (Gene) | Country | Study ID | HSC Source | CD34 Purification Method | Pre-stim Condition (Length) | Vector Type and Transduction Condition | Culture Length | Infusion Dose per kg (Medium) | Transduction Efficiency (No. Patients Treated) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCID-X1 (IL2RG) | France | NA | BM | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL MDGF, 60 ng/ mL IL-3, 300 ng/mL Flt3-L (24 hr) | γ-retro (MLV-LTR) addition of vector supernatant every day for 3 days | 4 days | 1–20 × 106 (4 × 106) | VCN/cell for product: NA VCN/cell in T cells: 0.5-1.5 (10) | 82, 83 |

| UK | NA | BM | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL TPO, 20 ng/mL IL-3, and 300 ng/mL Flt3-L (40 hr) | γ-retro (MLV-LTR) 3 rounds of transduction in 56 hr | 4 days | 6.9−34.1 × 106 (23.1 × 106) | 18.4%–57.7% (10) | 37, 41, 84, 85 | |

| US | NCT00028236 | MPB | Isolex300i | 50 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL Flt3 L, 50 ng/mL TPO, 25 ng/mL IL-6, and 5 ng/mL IL-3 (16 hr) | γ-retro (MLV-LTR) addition of 100 mL of vector per 100 × 106 cells every 6 hr/day on 4 consecutive days | 5 days | 28.5–31.3 × 106 (29.2 × 106) | VCN/cell: 1.1, 2.3, 3.7 (3) | 86 | |

| France, UK, US | NCT01410019 NCT01175239 NCT01129544 | BM | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL MDGF, 60 ng/mL IL-3, and 300 ng/mL, Flt3-L (24 hr) or 300 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL TPO, 20 ng/mL IL-3, and 300 ng/mL Flt3-L (40 hr) | SIN γ-retro (EF-1α S) 3 rounds of transduction in 56 hr | 4 days | 3.7–10 × 106 (7.7 × 106) | VCN/cell: 0.25–2.92 (9) | 47 | |

| US | NCT01306019 | MPB | Isolex 300i | 50–100 ng/mL SCF, 50–100 ng/mL FLT-3L, 50–100 ng/mL TPO, and 5 ng/mL IL-3 (overnight) | SIN-lenti (EF-1α) 6–8 hr each day for 2 consecutive days | 3 days | 16–25 × 106 (20.4 × 106) | 17%–57.5% (5) | 51 | |

| ADA-SCID | Italy | NCT 00599781 | BM | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 300 ng/mL FLT3-L, 100 ng/mL, TPO, and 60 ng/mL IL-3 (1 day) | MLV-LTR(GIADAl) preloading of GIADAl retroviral vector sup 33°C 4 hr, then incubate with CD34+ cells, 3 rounds of gene transfer in 3 days | 4 days | 0.9–13.6 × 106 (9.1 × 106) | VCN/cell: 0.35–2.2 (18) | 87 |

| UK | NA | BM | CliniMACS | SCF (300 ng/mL), TPO (100 ng/mL), IL3 (20 ng/mL), and Flt3-L (300 ng/mL) (40 hr) | MLV- SFFV LTR-WPRE mut) (SFada/W) 3 rounds of transduction in 56 hr | 4 days | <0.5–1.8 × 106 (3.2 × 106) | 5%–50% (6) | 37, 88 | |

| US | NCT 00018018 | BM | Isolex 300i | 50 ng/mL SCF, 300 ng/mL Flt-3L, and 50 ng/mL MGDF (40–48 hr) | MLV- MPSV LTR and MLV-MND-LTR 3 rounds of transduction every 24 hr | 5 days | 0.7–9.8 × 106 (1.9 × 106) | VCN/cell: 0.1–13 (10) | 38 | |

| UK, US | NCT 01380990 NCT 02022696 NCT 01852071 NCT00598481 | BM | NA | NA (24 hr) | SIN-lenti (EF-1α S) 18 hr | NA | 3–17 × 106 (NA) | VCN/cell: 0.25–6.3 (20) | 4, 53 | |

| WAS (WASP) | Germany | DRKS00000330 | BM or MPB | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 300 ng/mL FLT3L, 100 ng/mL TPO, and 60 ng/mL IL-3 | γ-retro (LTR) | NA | NA | VCN/cell: 1.7–5.2 (10) | 43, 44 |

| UK, France | NCT01347242 NCT01347346 NCT02333760 | BM or MPB | CliniMACS | SCF (300 ng/mL), Flt-3L (300 ng/mL), TPO (100 ng/mL), and IL-3 (20 ng/mL) (24 hr) | SIN-lenti (WAS promoter) LV-w1.6 WASp 2 rounds of transduction twice with 18 hr each time | 3 days | 2–11 × 106 (6.8 × 106) | VCN/cell: 0.6–2.8 (7) | 54 | |

| Italy | NCT 01515462 | BM or MPB | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 300 ng/mL Flt-3L, 100 ng/mL TPO, and 60 ng/mL IL-3 (24 hr) | SIN-lenti (WAS promoter) LV-w1.6 WASp 2 rounds of transduction MOI of 100 | 3 days | 8.91–14.1 × 106 (10.3 × 106) | VCN/cell: 1.4–2.8 (8) | 4, 55 | |

| US | NCT01410825 | BM | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 300 ng/mL Flt-3L, 100 ng/mL TPO, and 20 ng/mL IL-3 (24 hr) | SIN-lenti (WAS promoter) | 3 days | NA | NA (2) | 3 | |

| CGD (CYBB) | US | NA | MPB | Isolex 300i | 100 ng/mL IL-3, 100 ng/mL GM-CSF, and 10 ng/mL G-CSF (overnight) | γ-retro (MLV-LTR) 3 rounds of spin-inoculation every 24 hr in 3 days | 4 days | 0.1–4.7 × 106 (2.5 × 106) | VCN/cell: 0.05–0.18 (5) | 89 |

| Germany | NA | MPB | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 300 ng/mL Flt-3L, 100 ng/mL TPO, and 60 ng/mL IL-3 (36 hr) | γ-retro (SFFV-LTR) 3 rounds transduction 24 hr apart by incubating on freshly coated/preloaded flasks | 5 days | 3.6–5.1 × 106 (4.4 × 106) | P1: 45% P2: 39.5% (2) | 46, 90 | |

| Switzerland | NCT00927134 | MPB | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 300 ng/mL Flt-3L, 100 ng/mLTPO, and 60 ng/mL IL-3 (36 hr) | γ-retro (SFFV-LTR) 3 rounds transduction 24 hr apart by incubating on freshly coated/preloaded flasks | 5 days | 6.0 × 106 (6.0 × 106) | 32.3% (1) | 90, 91, 92 | |

| UK | NA | NA | NA | NA | γ-retro (MLV-LTR or SFFV-LTR) | NA | 0.2–10.0 × 106 (NA) | 5%–20% (4) | 90 | |

| US | NCT00394316 | MPB | Isolex 300i or CliniMACS | 50 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL TPO, 50 ng/mL Flt-3L, and 5 ng/mL IL-3 (16–18 hr) | γ-retro (MLV-LTR) cells were transduced daily times 4 days for 6 hr/day | 4 days | 18.9–71 × 106 (43 × 106) | 25%–73% (3) | 90, 93 | |

| Korea | NCT00778882 | MPB | CliniMACS | 300 ng/mL SCF, 300 ng/mL Flt-3L, 100 ng/mLTPO, and 60 ng/mL IL-3 (40 hr) | γ-retro (MLV-LTR) MT−gp91 3 rounds transduction in 40 hr on freshly coated/preloaded flasks | 4 days | 5.4 × 106, 5.8 × 106 (5.6 × 106) | P1: 10.5% P2: 28.5% (2) | 90, 94 | |

| Europe | NCT01855685 G1XCGD.01 | MPB | NA | NA | SIN-lenti | NA | NA | NA | 2 | |

| US | NCT02234934 NCT02757911 | MPB | NA | NA | SIN-lenti (G1XCGD) | NA | NA | NA | 2 | |

| Germany | NCT01906541 | MPB | NA | NA | SIN-retro | NA | no patient yet | NA | 2 | |

| X-ALD (ABCD1) | France | NA | MPB | CliniMACS | 100 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL MDGF, 100 ng/mL Flt3-L, 60 ng/mL IL-3, and 4 μg/mL PS (19 hr) | SIN-lenti vector was added at MOI = 25 for 17 hr | 2 days | 4.6 × 106, 7.2 × 106 (5.9 × 106) | P1: 50% P2: 33% (2) | 57, 62 |

| US | NCT01896102 | NA | NA | NA | SIN-Lenti (Lenti-D) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| MLD (ARSA) | Italy | NCT01560182 | BM | CliniMACS | NA | SIN-lenti (ARSA-LV) 2 rounds of transductions 16 hr each time with 108 TU/mL ARSA-LV | 3 days | 4.2–18.2 × 106 (9.9 × 106) | VCN/cell: 1.7–4.4 (9) | 58, 62 |

| China | NCT02559830 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA, not available; BM, bone marrow; MPB, mobilized peripheral blood; SCF, stem cell factor; MGDF, polyethylene glycol-megakaryocyte differentiation factor; Flt-3L, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; TPO, thrombopoietin; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MLV, murine leukemia virus; IL-3, interleukin 3; PS, protamine sulfate; LTR, long terminal repeats; SFFV, spleen focus-forming virus; MPSV, myeloproliferative sarcoma virus; MND, modified version of MPSV LTR with deletion of a negative control region and alterations of the adjacent primer binding site.38

Vectors for HPSC Genetic Engineering

Multiple gene delivery vector systems, including adenoviral vectors, adenovirus-associated virus-derived vectors (AAV), herpes simplex viral vectors, retroviral vectors, and lentiviral vectors, have been developed to provide either non-integrating transient gene correction or integrating stable gene transfer.28 For post-mitotic tissues, non-integrating vectors such as AAV vectors have been used in applications such as cancer,29 hemophilia,30, 31 and inherited retinal dystrophy.32, 33, 34 For stable gene transfer, retroviral vector and lentiviral vector are the vectors of choice because of their ability to integrate into the host genome. Owing to HSPCs’ pluripotency, permanent correction of the gene of interest in HSPCs through genetic engineering provides a potential cure for patients who lack a suitable HSCT donor. Advanced sequencing technology and analytical tools have led to better understanding of the vector insertion pattern, which has guided a series of vector design improvements resulting in safer and more effective gene transfer strategies.35, 36

Gamma-Retroviral Vectors

The Moloney murine leukemia (MLV)-based γ retroviral vector (γRV) with intact long terminal repeats (LTRs) was among the first vectors employed for HSC gene therapy. More than 40 ADA-SCID patients have been treated with this vector, yielding 100% survival and 75% disease-free survival without detectable insertional mutagenesis.37, 38 However, despite marked clinical benefits in 20 X-SCID patients treated with CD34+ HSPCs transduced with MLV γRV expressing the common cytokine receptor γ chain,39 5 of them developed T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia due to γRV insertion-induced transactivation of LMO2 or CCND2 proto-oncogenes.40, 41, 42 Similarly, 7 of 10 patients treated with HSPCs transduced with MLV γRV encoding WAS protein developed leukemia associated with the dysregulation of LMO2 or with secondary myeloid malignancy as a result of insertional mutations in the MDS-Evi 1 locus.43, 44, 45 The γRV SF71pg91phox vector in which the gp91phox subunit of the NADPH oxidase is expressed under the control of the spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV)-derived LTR was used in clinical trials to treat patients with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease (X-CDG). Although two patients treated with this vector demonstrated initial clinical benefits, both of them developed pre-leukemic myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) due to the dysregulation of MDS1/EVI1.46

Self-Inactivating-Retroviral Vectors

Self-inactivating (SIN)-γRVs have been generated to improve the safety profile of γRV, in which the U3 promoter/enhancer is deleted from the LTR and the transgene expression is driven by an internal promoter. Such SIN-γRVs have been successfully used in X-SCID clinical trials, where the common cytokine γ chain expression is driven by the elongation factor 1α (EF1α) short promoter.47, 48 Among nine patients, eight experienced stable correction of their immune cell functions, without retroviral vector insertional mutagenesis-related genotoxicity.47

Lentiviral Vectors

By using a tumor-prone mouse model, it was shown that lentiviral vectors (LVs) have a lower genotoxicity profile as compared to γRVs.49 This feature was also demonstrated in a sensitive in vitro immortalization (IVIM) assay performed in hematopoietic cells.50 SIN-LVs have become the vectors of choice in the most recently initiated clinical trials using HSCs. None of the patients who have displayed clear clinical benefits among the X-SCID (n = 5),51 ADA-SCID (n = 20),38, 52, 53 WAS (n = 27),3, 43, 44, 54, 55, 56 ALD (n = 2),57 and MLD (n = 9)58, 59 patients have undergone adverse events related to LV insertional mutagenesis post-autologous HSC gene therapy except one patient with thalassemia. In this patient, a single myeloid progenitor clone emerged upon trans-activation at the HMGA2 locus and eventually regressed after 7 years upon presumed exhaustion of the mutated clone. Importantly, this clone never progressed to leukemia.60 In-depth molecular analysis of the reconstituted hematopoiesis in patients with various diseases and treated with different types of vectors has allowed the characterization of vector-insertion distribution.61 Unlike the early intact γRV LTRs, chimeric LV LTRs elicit much less frequent dominant clones and display different insertion site preferences.54, 55, 62

CD34+ Cell Activation, Transduction, Formulation, and Cryopreservation

Efficient gene delivery and stable transduction of CD34+ cells require their pre-activation to exit cell cycle arrest. Gamma-retroviral vectors can only transduce dividing cells. Lentiviral vectors can infect non-dividing cells, but reverse transcription is minimal in G0-arrested cells.63 Upon collection and selection, the large majority of CD34+ cells from BM and MPB are in G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle; in addition, the BM-derived CD34+ cells contain approximately 10% of cells in S and G2/M phases.64 Stem cell factor (SCF) has been shown to effectively activate HSPCs for transduction when using a retroviral vector.65 The most commonly used activation conditions combine SCF, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3-L), thrombopoietin (TPO), and interleukin 3 (IL-3) for both γRV- and LV-mediated gene transfer (Table 1).

After pre-stimulation ranging from 14 to 40 hr, CD34+ cells are exposed to one or multiple rounds of transduction using either γRV or LV in presence of the same pre-stimulation cytokine cocktail. RetroNectin-coated tissue culture bags are frequently used to facilitate the transduction. The time in culture ranges from 2 to 5 days, resulting in transduction efficiency encompassing a wide range (Table 1). In order to minimize HSC differentiation and to maintain their pluripotency, the time in culture is kept short. In addition, maintaining the cultures for less than 4 days following the transduction allows archiving the quality control (QC) samples for replication-competent lentivirus (RCL) while alleviating the need to perform this expensive test.66 The transduced cell populations are subsequently harvested, washed, formulated, and released for patient infusion either fresh or upon cryopreservation.

For the trials listed in Table 1, Cartier et al.57 reported the use of cryopreserved cell products with hematopoietic recovery occurring at day 13 to 15 post-infusion, whereas other patients were treated with cells post-formulation without cryopreservation. For cryopreserved stem cell products, post-thaw viability constitutes one of the release tests. It has been recently reported that the viability of cryopreserved peripheral blood stem cells does not always correlate with the functional colony formation activity and engraftment outcome.67 Cryopreservation has a direct impact on the engraftment potential of stem cells from BM, peripheral blood (PB), and cord blood sources. Fast freeze rate is deleterious to clonogenic recovery and could be a major factor for engraftment failure.68, 69, 70 Thus, caution must be taken in designing rate-controlled freezer programs when using cryopreserved stem cell products.

HSC Gene Therapy Quality Control

Because the production processes are patient specific, moving forward this personalized cellular therapy toward a standard therapy poses great challenges.

The manufacturing procedure needs to be carried out by trained manufacturing personnel under good manufacturing practices (GMPs) following validated conditions. The quality of genetically engineered HSCs is subject to donor-to-donor variability and is also dependent on the manufacturing environment, the quality of ancillary raw materials/reagents, and a robust, controlled, and reproducible manufacturing process to ensure product consistency with minimal risk of contamination. We previously published how our group validated the collection, transduction, and formulation of CD34+ cells derived from thalassemic patients genetically modified with a LV encoding a normal β-globin gene, prior to initiating the first phase I clinical trial approved by the FDA in the United States.71 Product quality is built within every manufacturing step and established through process qualification procedures and robust validation studies. More recently, we extensively reviewed the qualification of manufacturing processes and ancillary components for manufacturing chimeric antigen receptor T cells, which also applies to the clinical manufacturing of genetically engineered HSPCs.72 Herein, we will therefore focus on the release testing of HPSC products.

The product testing and release criteria are devised to address the fundamental properties of the product including safety, purity, identity, and potency. Safety requires the lack of harmful contaminations, such as microbial agents, endotoxin, and mycoplasma; purity is reflected by the percentage of CD34+ cells and the transduction efficiency in the final product; identity of the product is commonly defined by the level of transgene incorporation in the genome; and potency of the transduced HSCs is often determined through soft agar colony formation assay and level of transgene expression in progenitors. Table 2 summarizes examples of release assays for RV or LV vector-transduced HSCs. The release of the cell products for infusion is handled through the issuance of a certificate of analysis, which summarizes the specifications and characteristics of the products and the release tests that have been performed.

Table 2.

Example of Release Tests for Retroviral and Lentiviral Transduced HSCs

| Testing | Example Assays | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | ||

| Sterility | USP, no growth within 14 days | sterile |

| Mycoplasma | PTC | negative |

| Endotoxin level | LAL | ≤5 EU/kg |

| Copies of transgene insertion per cell | qPCR | ≤4 or 5 |

| RCL/RCR (only required for culture exceeding 96 hr) | marker-rescue cell culture assay | no RCL/RCR detected |

| Purity | ||

| Immunophenotype (CD34) | FACS | ≥90% CD34+ or report value |

| Identity | ||

| Vector copy number or biological activity of transgene | qPCR or other gene specific assays | report value |

| Potency | ||

| Colony formation | CFU assay | report value |

| Viability | trypan blue or automated cell count | ≥80% pre-formulation |

| ≥70% post-thaw | ||

USP, US Pharmacopeia; PTC, points to consider; LAL, limulus amebocyte lysate; EU, endotoxin unit; RCL, replication-competent lentivirus; RCR, replication-competent retrovirus; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; CFU, colony-forming unit.

Future Perspectives

Since the initiation of the first gene therapy trial in ADA-SCID patients in 1990s,73, 74 we have embraced the approval of HSC gene therapy as the first line of therapy for this disease.6 Cumulative evidence shows that HSC gene therapy is an effective treatment for various immunodeficiencies, inherited blood disorders, and monogenic metabolic diseases. More than 150 patients who did not have a matched donor have been treated with γRV or LV vector-transduced HSPCs worldwide, the majority of which have demonstrated some clinical benefit (Table 1).

However, many challenges remain to be overcome. Standardization and automation of the manufacturing process await to be further developed. A very promising semi-automated system was recently reported to successfully transduce and manufacture non-human primate autologous gene-modified CD34+ cell products that were capable of stable, polyclonal multilineage reconstitution.75 This process is likely to be adapted to the transduction of human HPSCs.

It is advisable to further develop cell manufacturing processes based on quality-by-design (QbD) principles.76 In order for HSC-based therapies to realize their transformative potential, QbD principles should allow the linkage of measurable molecular and cellular characteristics of the cell population to final product quality.77 A well-designed manufacturing platform should take into account the complexity of process scheduling, traceability, and time to release given the unique nature of this personalized medicine.

Vector insertional mutagenesis is still a major safety concern. The safety profiles for lentiviral vector-based trials are encouraging,51, 55, 59 and follow-up of these patients is ongoing. The maturation of gene-editing technologies, such as zinc finger endonuclease,78 TALEN,79 and CRISPR/Cas,80 also offers new prospects and promises for in situ gene correction and may allow to take advantage of the endogenous regulatory machinery to drive the physiological level of gene expression.81

The approval of HSC gene therapy for ADA-SCID is likely to widen the interest from industry and biotechnology companies, which will help develop automation platforms to enable commercialization. Certain existing platforms used in CAR-T cell manufacturing might also be suitable for genetically engineered-HSC production.72 The field of HSC gene therapy is evolving at a fast pace. Successful clinical applications are poised to promote this exciting treatment modality to the forefront of standard of care in the near future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michel Sadelain for thoroughly reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by NCI grants P30 CA08748, NYSTEM grant N14C-010, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation grant GC202631, and Starr Foundation grant 2014-023.

References

- 1.Müller A.M., Huppertz S., Henschler R. Hematopoietic stem cells in regenerative medicine: astray or on the path? Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2016;43:247–254. doi: 10.1159/000447748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Booth C., Gaspar H.B., Thrasher A.J. Treating immunodeficiency through HSC gene therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2016;22:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo C.Y., Kohn D.B. Gene therapy for the treatment of primary immune deficiencies. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16:39. doi: 10.1007/s11882-016-0615-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cicalese M.P., Aiuti A. Clinical applications of gene therapy for primary immunodeficiencies. Hum. Gene Ther. 2015;26:210–219. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansilla-Soto J., Riviere I., Boulad F., Sadelain M. Cell and gene therapy for the beta-thalassemias: advances and prospects. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016;27:295–304. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ylä-Herttuala S. ADA-SCID gene therapy endorsed by European medicines agency for marketing authorization. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:1013–1014. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavazzana M., Six E., Lagresle-Peyrou C., André-Schmutz I., Hacein-Bey-Abina S. Gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency: where do we stand? Hum. Gene Ther. 2016;27:108–116. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Touzot F., Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Fischer A., Cavazzana M. Gene therapy for inherited immunodeficiency. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2014;14:789–798. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2014.895811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver C.H., Hazelton B., Birch R., Palmer P., Allen C., Schwartzberg L., West W. An analysis of engraftment kinetics as a function of the CD34 content of peripheral blood progenitor cell collections in 692 patients after the administration of myeloablative chemotherapy. Blood. 1995;86:3961–3969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carral A., de la Rubia J., Martín G., Martínez J., Sanz G., Jarque I., Sempere A., Soler M.A., Marty M.L., Sanz M.A. Factors influencing hematopoietic recovery after autologous blood stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia and with non-myeloid malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:825–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas E.D., Lochte H.L., Jr., Lu W.C., Ferrebee J.W. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1957;257:491–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195709122571102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giralt S., Costa L., Schriber J., Dipersio J., Maziarz R., McCarty J., Shaughnessy P., Snyder E., Bensinger W., Copelan E. Optimizing autologous stem cell mobilization strategies to improve patient outcomes: consensus guidelines and recommendations. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quittet P., Ceballos P., Lopez E., Lu Z.Y., Latry P., Becht C., Legouffe E., Fegueux N., Exbrayat C., Pouessel D. Low doses of GM-CSF (molgramostim) and G-CSF (filgrastim) after cyclophosphamide (4 g/m2) enhance the peripheral blood progenitor cell harvest: results of two randomized studies including 120 patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:275–284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liles W.C., Broxmeyer H.E., Rodger E., Wood B., Hübel K., Cooper S., Hangoc G., Bridger G.J., Henson G.W., Calandra G., Dale D.C. Mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in healthy volunteers by AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood. 2003;102:2728–2730. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girbl T., Lunzer V., Greil R., Namberger K., Hartmann T.N. The CXCR4 and adhesion molecule expression of CD34+ hematopoietic cells mobilized by “on-demand” addition of plerixafor to granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor. Transfusion. 2014;54:2325–2335. doi: 10.1111/trf.12632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valtola J., Varmavuo V., Ropponen A., Nihtinen A., Partanen A., Vasala K., Lehtonen P., Penttilä K., Pyörälä M., Kuittinen T. Blood graft cellular composition and posttransplant recovery in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients mobilized with or without plerixafor: a prospective comparison. Transfusion. 2015;55:2358–2368. doi: 10.1111/trf.13170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karponi G., Psatha N., Lederer C.W., Adair J.E., Zervou F., Zogas N., Kleanthous M., Tsatalas C., Anagnostopoulos A., Sadelain M. Plerixafor+G-CSF-mobilized CD34+ cells represent an optimal graft source for thalassemia gene therapy. Blood. 2015;126:616–619. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-629618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steininger P.A., Strasser E.F., Weiss D., Achenbach S., Zimmermann R., Eckstein R. First comparative evaluation of a new leukapheresis technology in non-cytokine-stimulated donors. Vox Sang. 2014;106:248–255. doi: 10.1111/vox.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brauninger S., Bialleck H., Thorausch K., Felt T., Seifried E., Bonig H. Allogeneic donor peripheral blood “stem cell” apheresis: prospective comparison of two apheresis systems. Transfusion. 2012;52:1137–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu F.Y., Heng K.K., Salleh R.B., Soh T.G., Lee J.J., Mah J., Linn Y.C., Loh Y., Hwang W., Tan L.K. Comparing peripheral blood stem cell collection using the COBE Spectra, Haemonetics MCS+, and Baxter Amicus. Transfus. Apheresis Sci. 2012;47:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu Y.M., Cushing M.M. Autologous stem cell mobilization and collection. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2016;30:573–589. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Donnell P.V., Myers B., Edwards J., Loper K., Rhubart P., Noga S.J. CD34 selection using three immunoselection devices: comparison of T-cell depleted allografts. Cytotherapy. 2001;3:483–488. doi: 10.1080/146532401317248081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schumm M., Lang P., Taylor G., Kuçi S., Klingebiel T., Bühring H.J., Geiselhart A., Niethammer D., Handgretinger R. Isolation of highly purified autologous and allogeneic peripheral CD34+ cells using the CliniMACS device. J. Hematother. 1999;8:209–218. doi: 10.1089/106161299320488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hümmer C., Poppe C., Bunos M., Stock B., Wingenfeld E., Huppert V., Stuth J., Reck K., Essl M., Seifried E., Bonig H. Automation of cellular therapy product manufacturing: results of a split validation comparing CD34 selection of peripheral blood stem cell apheresis product with a semi-manual vs. an automatic procedure. J. Transl. Med. 2016;14:76. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stroncek D.F., Tran M., Frodigh S.E., David-Ocampo V., Ren J., Larochelle A., Sheikh V., Sereti I., Miller J.L., Longin K., Sabatino M. Preliminary evaluation of a highly automated instrument for the selection of CD34+ cells from mobilized peripheral blood stem cell concentrates. Transfusion. 2016;56:511–517. doi: 10.1111/trf.13394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gastens M.H., Goltry K., Prohaska W., Tschöpe D., Stratmann B., Lammers D., Kirana S., Götting C., Kleesiek K. Good manufacturing practice-compliant expansion of marrow-derived stem and progenitor cells for cell therapy. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:685–696. doi: 10.3727/000000007783465172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radrizzani M., Lo Cicero V., Soncin S., Bolis S., Sürder D., Torre T., Siclari F., Moccetti T., Vassalli G., Turchetto L. Bone marrow-derived cells for cardiovascular cell therapy: an optimized GMP method based on low-density gradient improves cell purity and function. J. Transl. Med. 2014;12:276. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vannucci L., Lai M., Chiuppesi F., Ceccherini-Nelli L., Pistello M. Viral vectors: a look back and ahead on gene transfer technology. New Microbiol. 2013;36:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santiago-Ortiz J.L., Schaffer D.V. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors in cancer gene therapy. J. Control. Release. 2016;240:287–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nathwani A.C., Reiss U.M., Tuddenham E.G., Rosales C., Chowdary P., McIntosh J., Della Peruta M., Lheriteau E., Patel N., Raj D. Long-term safety and efficacy of factor IX gene therapy in hemophilia B. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1994–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tardieu M., Zérah M., Husson B., de Bournonville S., Deiva K., Adamsbaum C., Vincent F., Hocquemiller M., Broissand C., Furlan V. Intracerebral administration of adeno-associated viral vector serotype rh.10 carrying human SGSH and SUMF1 cDNAs in children with mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA disease: results of a phase I/II trial. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014;25:506–516. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simonelli F., Maguire A.M., Testa F., Pierce E.A., Mingozzi F., Bennicelli J.L., Rossi S., Marshall K., Banfi S., Surace E.M. Gene therapy for Leber’s congenital amaurosis is safe and effective through 1.5 years after vector administration. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:643–650. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Testa F., Maguire A.M., Rossi S., Pierce E.A., Melillo P., Marshall K., Banfi S., Surace E.M., Sun J., Acerra C. Three-year follow-up after unilateral subretinal delivery of adeno-associated virus in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis type 2. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1283–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson S.G., Cideciyan A.V., Roman A.J., Sumaroka A., Schwartz S.B., Heon E., Hauswirth W.W. Improvement and decline in vision with gene therapy in childhood blindness. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1920–1926. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montini E., Cesana D., Schmidt M., Sanvito F., Bartholomae C.C., Ranzani M., Benedicenti F., Sergi L.S., Ambrosi A., Ponzoni M. The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of HSC gene therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:964–975. doi: 10.1172/JCI37630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabriel R., Schmidt M., von Kalle C. Integration of retroviral vectors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012;24:592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaspar H.B., Cooray S., Gilmour K.C., Parsley K.L., Zhang F., Adams S., Bjorkegren E., Bayford J., Brown L., Davies E.G. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for adenosine deaminase-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency leads to long-term immunological recovery and metabolic correction. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:97ra80. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Candotti F., Shaw K.L., Muul L., Carbonaro D., Sokolic R., Choi C., Schurman S.H., Garabedian E., Kesserwan C., Jagadeesh G.J. Gene therapy for adenosine deaminase-deficient severe combined immune deficiency: clinical comparison of retroviral vectors and treatment plans. Blood. 2012;120:3635–3646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-400937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hacein-Bey H., Cavazzana-Calvo M., Le Deist F., Dautry-Varsat A., Hivroz C., Rivière I., Danos O., Heard J.M., Sugamura K., Fischer A., De Saint Basile G. Gamma-c gene transfer into SCID X1 patients’ B-cell lines restores normal high-affinity interleukin-2 receptor expression and function. Blood. 1996;87:3108–3116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Von Kalle C., Schmidt M., McCormack M.P., Wulffraat N., Leboulch P., Lim A., Osborne C.S., Pawliuk R., Morillon E. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howe S.J., Mansour M.R., Schwarzwaelder K., Bartholomae C., Hubank M., Kempski H., Brugman M.H., Pike-Overzet K., Chatters S.J., de Ridder D. Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of SCID-X1 patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3143–3150. doi: 10.1172/JCI35798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Garrigue A., Wang G.P., Soulier J., Lim A., Morillon E., Clappier E., Caccavelli L., Delabesse E., Beldjord K. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3132–3142. doi: 10.1172/JCI35700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boztug K., Schmidt M., Schwarzer A., Banerjee P.P., Díez I.A., Dewey R.A., Böhm M., Nowrouzi A., Ball C.R., Glimm H. Stem-cell gene therapy for the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1918–1927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braun C.J., Boztug K., Paruzynski A., Witzel M., Schwarzer A., Rothe M., Modlich U., Beier R., Göhring G., Steinemann D. Gene therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome—long-term efficacy and genotoxicity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:227ra33. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams D.A., Thrasher A.J. Concise review: lessons learned from clinical trials of gene therapy in monogenic immunodeficiency diseases. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014;3:636–642. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ott M.G., Schmidt M., Schwarzwaelder K., Stein S., Siler U., Koehl U., Glimm H., Kühlcke K., Schilz A., Kunkel H. Correction of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease by gene therapy, augmented by insertional activation of MDS1-EVI1, PRDM16 or SETBP1. Nat. Med. 2006;12:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nm1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Pai S.Y., Gaspar H.B., Armant M., Berry C.C., Blanche S., Bleesing J., Blondeau J., de Boer H., Buckland K.F. A modified γ-retrovirus vector for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1407–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stein S., Ott M.G., Schultze-Strasser S., Jauch A., Burwinkel B., Kinner A., Schmidt M., Krämer A., Schwäble J., Glimm H. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Nat. Med. 2010;16:198–204. doi: 10.1038/nm.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montini E., Cesana D., Schmidt M., Sanvito F., Ponzoni M., Bartholomae C., Sergi Sergi L., Benedicenti F., Ambrosi A., Di Serio C. Hematopoietic stem cell gene transfer in a tumor-prone mouse model uncovers low genotoxicity of lentiviral vector integration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:687–696. doi: 10.1038/nbt1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Modlich U., Navarro S., Zychlinski D., Maetzig T., Knoess S., Brugman M.H., Schambach A., Charrier S., Galy A., Thrasher A.J. Insertional transformation of hematopoietic cells by self-inactivating lentiviral and gammaretroviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1919–1928. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Ravin S.S., Wu X., Moir S., Anaya-O’Brien S., Kwatemaa N., Littel P., Theobald N., Choi U., Su L., Marquesen M. Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016;8:335ra57. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaspar H.B., Buckland K., Rivat C., Himoudi N., Gilmour K., Booth C., Cornetta K., Kohn D.B., Carbonaro D., Paruzynski A., Schmidt M. Immunological and metabolic correction after lentiviral vector mediated haematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for ADA deficiency. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:S106. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaspar H.B., Buckland K., Carbonaro D.A., Shaw K., Barman P., Davila A., Gilmour K.C., Booth C., Terrazs D., Cornetta K., Paruzynski A. Immunological and metabolic correction after lentiviral vector gene therapy for ADA deficiency. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:S102–S103. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hacein-Bey Abina S., Gaspar H.B., Blondeau J., Caccavelli L., Charrier S., Buckland K., Picard C., Six E., Himoudi N., Gilmour K. Outcomes following gene therapy in patients with severe Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. JAMA. 2015;313:1550–1563. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aiuti A., Biasco L., Scaramuzza S., Ferrua F., Cicalese M.P., Baricordi C., Dionisio F., Calabria A., Giannelli S., Castiello M.C. Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy in patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Science. 2013;341:1233151. doi: 10.1126/science.1233151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castiello M.C., Scaramuzza S., Pala F., Ferrua F., Uva P., Brigida I., Sereni L., van der Burg M., Ottaviano G., Albert M.H. B-cell reconstitution after lentiviral vector-mediated gene therapy in patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:692–702.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cartier N., Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Bartholomae C.C., Veres G., Schmidt M., Kutschera I., Vidaud M., Abel U., Dal-Cortivo L., Caccavelli L. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326:818–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sessa M., Lorioli L., Fumagalli F., Acquati S., Redaelli D., Baldoli C., Canale S., Lopez I.D., Morena F., Calabria A. Lentiviral haemopoietic stem-cell gene therapy in early-onset metachromatic leukodystrophy: an ad-hoc analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:476–487. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biffi A., Montini E., Lorioli L., Cesani M., Fumagalli F., Plati T., Baldoli C., Martino S., Calabria A., Canale S. Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy benefits metachromatic leukodystrophy. Science. 2013;341:1233158. doi: 10.1126/science.1233158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cavazzana-Calvo M., Payen E., Negre O., Wang G., Hehir K., Fusil F., Down J., Denaro M., Brady T., Westerman K. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human β-thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biasco L., Baricordi C., Aiuti A. Retroviral integrations in gene therapy trials. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:709–716. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Biffi A., Aubourg P., Cartier N. Gene therapy for leukodystrophies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20(R1):R42–R53. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naldini L., Blömer U., Gallay P., Ory D., Mulligan R., Gage F.H., Verma I.M., Trono D. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Bruyn C., Delforge A., Lagneaux L., Bron D. Characterization of CD34+ subsets derived from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood and mobilized peripheral blood after stem cell factor and interleukin 3 stimulation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:377–383. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Budak-Alpdogan T., Przybylowski M., Gonen M., Sadelain M., Bertino J., Rivière I. Functional assessment of the engraftment potential of gammaretrovirus-modified CD34+ cells, using a short serum-free transduction protocol. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17:780–794. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.US Food and Drug Administration (2006). Guidance for industry: supplemental guidance on testing for replication competent retrovirus in retroviral vector-based gene therapy products and during follow-up of patients in clinical trials using retroviral vectors. https://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/CellularandGeneTherapy/ucm072961.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Morgenstern D.A., Ahsan G., Brocklesby M., Ings S., Balsa C., Veys P., Brock P., Anderson J., Amrolia P., Goulden N. Post-thaw viability of cryopreserved peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) does not guarantee functional activity: important implications for quality assurance of stem cell transplant programmes. Br. J. Haematol. 2016;174:942–951. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abrams R.A., Glaubiger D., Simon R., Lichter A., Deisseroth A.B. Haemopoietic recovery in Ewing’s sarcoma after intensive combination therapy and autologous marrow infusion. Lancet. 1980;2:385–389. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gorin N.C., Douay L., David R., Stachowiak J., Parlier Y., Oppenheimer M., Najman A., Duhamel G. Delayed kinetics of recovery of haemopoiesis following autologous bone marrow transplantation. The role of excessively rapid marrow freezing rates after the release of fusion heat. Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 1983;19:485–491. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(83)90111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watts M.J., Linch D.C. Optimisation and quality control of cell processing for autologous stem cell transplantation. Br. J. Haematol. 2016;175:771–783. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boulad F., Wang X., Qu J., Taylor C., Ferro L., Karponi G., Bartido S., Giardina P., Heller G., Prockop S.E. Safe mobilization of CD34+ cells in adults with β-thalassemia and validation of effective globin gene transfer for clinical investigation. Blood. 2014;123:1483–1486. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-507178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang X., Rivière I. Clinical manufacturing of CAR T cells: foundation of a promising therapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2016;3:16015. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blaese R.M., Culver K.W., Miller A.D., Carter C.S., Fleisher T., Clerici M., Shearer G., Chang L., Chiang Y., Tolstoshev P. T lymphocyte-directed gene therapy for ADA- SCID: initial trial results after 4 years. Science. 1995;270:475–480. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Onodera M., Ariga T., Kawamura N., Kobayashi I., Ohtsu M., Yamada M., Tame A., Furuta H., Okano M., Matsumoto S. Successful peripheral T-lymphocyte-directed gene transfer for a patient with severe combined immune deficiency caused by adenosine deaminase deficiency. Blood. 1998;91:30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adair J.E., Waters T., Haworth K.G., Kubek S.P., Trobridge G.D., Hocum J.D., Heimfeld S., Kiem H.P. Semi-automated closed system manufacturing of lentivirus gene-modified haematopoietic stem cells for gene therapy. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13173. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rathore A.S., Winkle H. Quality by design for biopharmaceuticals. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:26–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt0109-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lipsitz Y.Y., Timmins N.E., Zandstra P.W. Quality cell therapy manufacturing by design. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:393–400. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Urnov F.D., Rebar E.J., Holmes M.C., Zhang H.S., Gregory P.D. Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:636–646. doi: 10.1038/nrg2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ott de Bruin L.M., Volpi S., Musunuru K. Novel genome-editing tools to model and correct primary immunodeficiencies. Front. Immunol. 2015;6:250. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sander J.D., Joung J.K. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Genovese P., Schiroli G., Escobar G., Di Tomaso T., Firrito C., Calabria A., Moi D., Mazzieri R., Bonini C., Holmes M.C. Targeted genome editing in human repopulating haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;510:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature13420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cavazzana-Calvo M., Hacein-Bey S., de Saint Basile G., Gross F., Yvon E., Nusbaum P., Selz F., Hue C., Certain S., Casanova J.L. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science. 2000;288:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Hauer J., Lim A., Picard C., Wang G.P., Berry C.C., Martinache C., Rieux-Laucat F., Latour S., Belohradsky B.H. Efficacy of gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:355–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gaspar H.B., Parsley K.L., Howe S., King D., Gilmour K.C., Sinclair J., Brouns G., Schmidt M., Von Kalle C., Barington T. Gene therapy of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by use of a pseudotyped gammaretroviral vector. Lancet. 2004;364:2181–2187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gaspar H.B., Cooray S., Gilmour K.C., Parsley K.L., Adams S., Howe S.J., Al Ghonaium A., Bayford J., Brown L., Davies E.G. Long-term persistence of a polyclonal T cell repertoire after gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:97ra79. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chinen J., Davis J., De Ravin S.S., Hay B.N., Hsu A.P., Linton G.F., Naumann N., Nomicos E.Y., Silvin C., Ulrick J. Gene therapy improves immune function in preadolescents with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Blood. 2007;110:67–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-058933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aiuti A., Cattaneo F., Galimberti S., Benninghoff U., Cassani B., Callegaro L., Scaramuzza S., Andolfi G., Mirolo M., Brigida I. Gene therapy for immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:447–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gaspar H.B., Bjorkegren E., Parsley K., Gilmour K.C., King D., Sinclair J., Zhang F., Giannakopoulos A., Adams S., Fairbanks L.D. Successful reconstitution of immunity in ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy following cessation of PEG-ADA and use of mild preconditioning. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Malech H.L., Maples P.B., Whiting-Theobald N., Linton G.F., Sekhsaria S., Vowells S.J., Li F., Miller J.A., DeCarlo E., Holland S.M. Prolonged production of NADPH oxidase-corrected granulocytes after gene therapy of chronic granulomatous disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12133–12138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grez M., Reichenbach J., Schwäble J., Seger R., Dinauer M.C., Thrasher A.J. Gene therapy of chronic granulomatous disease: the engraftment dilemma. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:28–35. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bianchi M., Hakkim A., Brinkmann V., Siler U., Seger R.A., Zychlinsky A., Reichenbach J. Restoration of NET formation by gene therapy in CGD controls aspergillosis. Blood. 2009;114:2619–2622. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bianchi M., Niemiec M.J., Siler U., Urban C.F., Reichenbach J. Restoration of anti-Aspergillus defense by neutrophil extracellular traps in human chronic granulomatous disease after gene therapy is calprotectin-dependent. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;127:1243–1252.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kang E.M., Choi U., Theobald N., Linton G., Long Priel D.A., Kuhns D., Malech H.L. Retrovirus gene therapy for X-linked chronic granulomatous disease can achieve stable long-term correction of oxidase activity in peripheral blood neutrophils. Blood. 2010;115:783–791. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-222760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kang H.J., Bartholomae C.C., Paruzynski A., Arens A., Kim S., Yu S.S., Hong Y., Joo C.W., Yoon N.K., Rhim J.W. Retroviral gene therapy for X-linked chronic granulomatous disease: results from phase I/II trial. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:2092–2101. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]