SUMMARY

The monocytic leukemia zinc-finger protein-related factor (MORF) is a transcriptional coactivator and a catalytic subunit of the lysine acetyltransferase complex implicated in cancer and developmental diseases. We have previously shown that the double plant homeodomain finger (DPF) of MORF is capable of binding to acetylated histone H3. Here we demonstrate that the DPF of MORF recognizes many newly identified acylation marks. The mass spectrometry study provides comprehensive analysis of H3K14 acylation states in vitro and in vivo. The crystal structure of the MORF DPF-H3K14butyryl complex offers insight into the selectivity of this reader toward lipophilic acyllysine substrates. Together, our findings support the mechanism by which the acetyltransferase MORF promotes spreading of histone acylation.

Keywords: PTM, epigenetic, lysine acylation, double PHD finger, DPF, MORF, histone binding

eTOC Blurb

Growing evidence suggests the important role of the lysine acylation states in metabolic pathways and epigenetic signaling. Klein et al. identified the DPF domain of the lysine acetyltransferase MORF as a reader of global histone H3K14 acylation.

INTRODUCTION

Latest breakthrough in mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of posttranslational modifications (PTMs) in histones reveals a wide array of acylation marks beside the established acetylation mark. These include formylation, propionylation, crotonylation, butyrylation, β-hydroxybutyrylation, 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation, malonylation, and succinylation of lysine (Huang et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2014). Although the significance of lysine acylation in the metabolic pathways has been documented, accumulating evidence suggests that the acyl chain variations are also essential for eliciting specific epigenetic responses (Choudhary et al., 2014; Dutta et al., 2016). Lysine butyrylation and crotonylation are found to concentrate at highly active gene promoters, and butyrylation, which competes with acetylation for the same lysine residues, blocks the recruitment of the testis-specific protein Brdt1 during spermatogenesis (Goudarzi et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Sabari et al., 2015). Modulation of acetylation through activities of lysine acetyltransferases (KATs) and deacetylases that add or remove this PTM and through the binding of acetyllysine-recognizing readers is well established (Andrews et al., 2016b; Musselman et al., 2012; Verdin and Ott, 2015), however very little is known about the proteins capable of writing, erasing or reading the newly discovered acylation PTMs. We used a systematic structure-based search of the protein surface channels that can accommodate large side-chains of acylated lysine, and have identified the DPF domain of MORF as a general acyllysine-recognizing reader with a slight preference toward lipophilic acylation.

MORF, also known as KAT6B or MYST4, is a catalytic subunit of the major human KAT complex (Klein et al., 2014a; Yang, 2015). The MORF KAT complex is required for neurogenesis and transcriptional regulation, and its genomic translocations and mutations are associated with cancer and developmental diseases (Huan et al., 2016; Yang, 2015). In addition to the catalytic MORF subunit, the native MORF complex contains the adaptor proteins BRPF1, ING5 and MEAF6 (Feng et al., 2016). Of the four core subunits, three – MORF, BRPF1 and ING5 – possess histone reader domains that recognize different PTMs. The multiple PTM-reader interactions fine-tune the MORF complex localization within the genome and its function. A single histone reader in the MORF subunit, the DPF module, has previously been shown to associate with acetylated histone H3 tails (Ali et al., 2012; Qiu et al., 2012), however its sensitivity to other acylated species has not been examined. Here, we report on the structural basis and selectivity of the DPF domain of MORF for the acylation marks, present on histone H3K14, and identified and characterized in vitro and in vivo profiles of H3K14 acylation modifications. Our findings suggest a mechanism-based preference of acyllysine readers toward selective acylation states that likely has significant functional implications.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

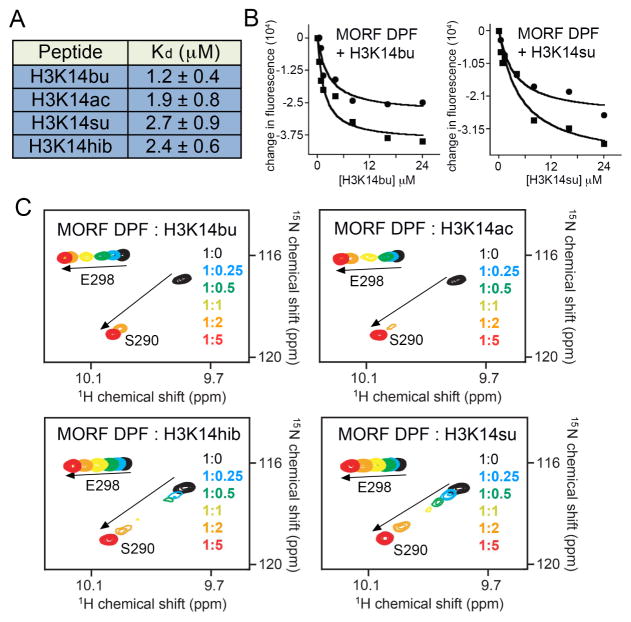

To determine whether the MORF subunit is capable of recognizing the long acyllysine side-chains, we generated an isolated DPF domain of MORF and examined its binding to the histone H3 peptides acylated at lysine 14 (H3K14acyl) (residues 1-19 of H3). We focused on the set of acylation modifications previously reported for the H3K14 site, including acetylation (H3K14ac), butyrylation (H3K14bu), 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation (H3K14hib), and succinylation (H3K14su) (Huang et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2014), and measured the dissociation constants (Kds) of the corresponding DPF-H3K14acyl complexes by fluorescence spectroscopy (Fig. 1a, b). Binding affinity of the MORF DPF domain to the H3K14bu peptide was found to be 1.3 μM, and comparable though only slightly weaker binding was detected to other acylated peptides, including H3K14ac, H3K14hib and H3K14su. The slight preference of the MORF DPF domain for butyrylated lysine was supported by 1H,15N HSQC experiments, in which H3K14bu, H3K14ac, H3K14hib and H3K14su peptides were titrated into the 15N-labeled DPF sample (Fig. 1b). Although all four NMR titrations revealed intermediate exchange regime on the NMR time scale, addition of H3K14bu induced more pronounced resonance changes at the beginning of the titration experiment and resulted in a faster saturation (compare spectra at the protein:peptide molar ratio of 1:0.25 and of 1:2 in the four panels in Fig. 1c). Altogether, these data demonstrate that the MORF DPF domain is a reader of global H3K14 acylation.

Figure 1. Acetyllysine selectivity of the MORF DPF domain.

(a) Binding affinities of the MORF DPF for indicated peptides were measured by tryptophan fluorescence. Values represent the average of three separate experiments. Error bars are SD. (b) Representative binding curves used to determine Kds. (c) Superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled MORF DPF, collected as indicated H3K14acyl peptides were added stepwise. The intermediate exchange regime is commonly observed for binding of readers to histone peptides, indicating strong interaction. Spectra are color coded according to the protein:peptide molar ratio (inset).

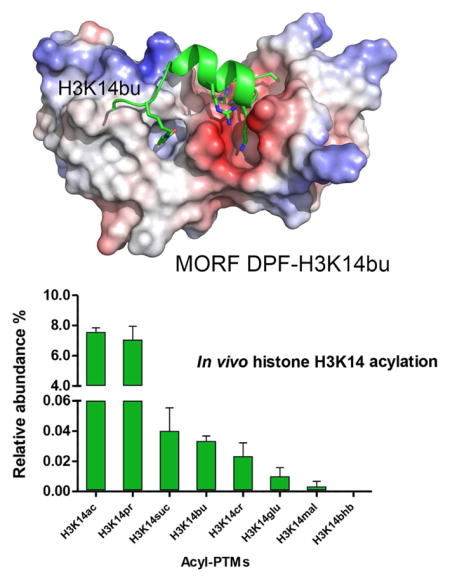

To define the molecular basis of the acyllysine recognition, we obtained a 1.6 Å resolution crystal structure of the MORF DPF domain in complex with H3K14bu peptide (aa 1-19 of H3) (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The structure reveals a bean-shaped double zinc finger scaffold of the protein, also seen in DPFs of DPF3b and MOZ (Dreveny et al., 2014; Qiu et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2010). The clear electron density, observed for the residues 1-15 of the H3K14bu peptide, indicates that they are well-ordered, and part of the peptide (residues K4-T11 of H3) adopts an α-helical conformation (Fig. 2a). The first eight N-terminal residues of the H3K14bu peptide are bound in an acidic groove, whereas butyrylated K14 inserts into a hydrophobic channel (Fig. 2b). Numerous intermolecular hydrogen bonding and electrostatic contacts stabilize the complex. The free amino group of A1 is bivalently engaged with the carbonyl oxygens of Pro308 and Gly310, allowing the methyl group of A1 to be buried in a shallow cavity composed of Leu286, Pro308, and Trp312. The guanidino group of R2 is constrained through a salt bridge with the carboxylate group of Asp292 and by two hydrogen bonds with the Asp289 carboxylate and the carbonyl oxygen of Cys288. The backbone amide of R2 donates a water-mediated hydrogen bond to Phe287. The amino group of K4 forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen of Ile267, and the side chain of R8 participates in two salt bridges with the carboxylate groups of Glu268 and Asp283. Additional stabilization of the histone peptide arises from a water-mediated hydrogen bond involving the guanidino group of Arg227 and the carbonyl oxygen of G13, and from the interactions between the side-chain amino group of Lys250 and the carbonyl oxygen of S10, and between backbone amide and carbonyl groups of A15 and Ser217.

Figure 2. The structural mechanism for the recognition of H3K14bu by MORF.

(a) The crystal structure of the MORF DPF-H3K14bu complex. The DPF domain is depicted in ribbon diagram with the first and second PHD fingers colored yellow and gray, respectively, and H3K14bu peptide is colored green. The histone peptide residues and the residues of DPF involved in the interaction are labeled. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. (b) The electrostatic surface potential of the MORF DPF is shown using blue and red colors for positive and negative charges, respectively. (c) A zoom-in view of the K14bu-binding channel.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| MORF DPF-H3K14bu | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P1211 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 32.54, 69.19, 69.93 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 97.2, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.60 (1.63–1.60)* |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.13 (2.7)* |

| I/σI | 12.1 (0.6)* |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.7)* |

| Redundancy | 9.5 (7.3)* |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 34.7–1.6 |

| No. reflections | 40102 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 18.0/23.0 |

| No. atoms | 2225 |

| Protein/peptide | 1947 |

| Water | 270 |

| Ligand/Ion | 8 |

| B-factors | 30.3 |

| Protein | 28.9 |

| Ligand/ion | 20.1 |

| Water | 40.7 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.07 |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell. Data was collected from a single crystal.

While stabilization of the H3K14bu peptide in the complex appears to be driven by electrostatic interactions, the main driving force of recognition of the butyryl moiety by MORF is mostly hydrophobic in nature. Close evaluation of the butyryllysine-binding channel reveals that with the exception of a water-meditated hydrogen bond formed between the side-chain amide nitrogen atom of K14bu and the hydroxyl group of Ser217 and Ser242, only hydrophobic contacts are observed. The hydrophobic side-chains of Phe218, Leu235, Leu249, Trp264 and Cys266, along with Ser210, Ser242 and Ser243, and G237 tightly lock the lipophilic butyryl moiety of K14bu (Fig. 2c). The predominantly hydrophobic nature of the acyllysine-binding pocket of MORF likely accounts for the selectivity of this protein toward the saturated acylated side-chains such as butyryl and acetyl, as compared to the charged (succinylyl) or polar (2-hydroxyisobutyryl).

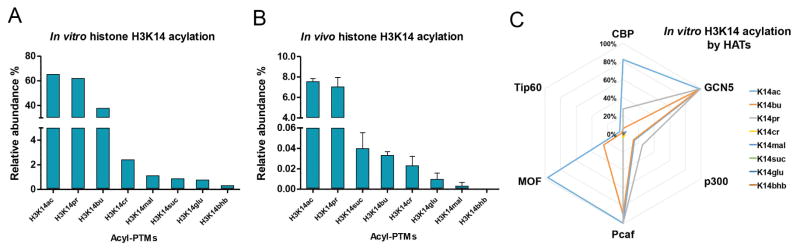

The four H3K14 acylation PTMs tested in this study have previously been identified in vitro (Huang et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2014), however their existence in vivo remains elusive. We carried out comprehensive analysis of H3K14 acylation states in vitro and in vivo using a mass spectrometry approach (Fig. 3). We performed in vitro enzymatic assays with the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domains of Gcn5 (KAT2A), PCAF (KAT2B), CBP (KAT3A) and p300 (KAT3B), known to be catalytically active, and the full length Tip60 (KAT5) and MOF (KAT8) HATs (MORF was not tested because the entire complex is required for its activity). The HATs and short-chain acyl-CoAs were incubated with recombinant histone H3, and reaction products were quantified by nano liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (nanoLC-MS/MS) (Fig. 3a). The resultant in vitro H3K14 acylation profile confirmed acetylation, butyrylation and succinylation at this site (Fig. 3a). Additionally, we found that H3K14 can be substantially propionylated both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 3a, b). Crotonylation, malonylation, β-hydroxybutyrylation and glutarylation were also observed, though these acylations of H3K14 occurred to a lesser extent. Of the six HATs examined, GCN5, PCAF and MOF were able to butyrylate H3K14 in vitro, whereas in vitro H3K14 propionylation was carried out by GCN5, PCAF and CBP (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Identification of histone H3K14acyl PTMs in vitro and in vivo.

(a) In vitro H3K14 acylation profiles. Values represent the average of the relative abundances of enzymatically acylated H3K14 by six HATs (see panel (c)). Lysine modification abbreviations are: acetyl (ac), propionyl (pr), butyryl (bu), crotonyl (cr), malonyl (mal), succinyl (suc), β-hydroxybutyryl (bhb), and glutaryl (glu). (b) Bar plots showing the quantification of acylated H3K14 in HeLa cells. All results are shown as the average of 3 biological replicates; error bars are SD. (c) In vitro specificity of HATs for H3K14acyl. Radar chart showing the H3K14 acylation activity of indicated HATs in the presence of acetyl-, propionyl-, crotonyl-, butyryl-, malonyl-, β-hydroxybutyryl-, succinyl-, and glutaryl-CoA. Each spoke represents a different HAT and the anchor represents the relative abundance of modified H3 peptide KSTGGKAPR (aa 9-17) at position H3K14. HATs Tip60 and MOF were only evaluated in the presence of acetyl- and butyryl-CoA. All results are shown as the average of 3 biological replicates.

In conclusion, we have identified the MORF DPF domain as a reader of global histone H3K14 acylation. Our findings provide new insight into the biological role of the MORF KAT subunit, which functions both as a writer and a reader of lysine acylation, much like the MOZ KAT, whose binding to crotonylated and other acylated H3K14 sequences has been reported recently and independently of our study (Xiong et al., 2016). The ability of MORF DPF to bind acylated and particularly butyrylated H3K14 may contribute to the recruitment or stabilization of the MORF complex at promoters of target genes, such as the HOX family. Our findings support the mechanism by which the MORF KAT, acting in trans, stimulates spreading of histone acylation. Such spreading is vital for the formation of open chromatin domains and can be strictly regulated through acylation. Importantly, the MORF DPF module expands the family of readers capable of binding to the newly identified acyllysine PTMs (Andrews et al., 2016a; Li et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2016).

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Email contact for reagent and resource sharing: tatiana.kutateladze@ucdenver.edu or bgarci@mail.med.upenn.edu.

METHOD DETAILS

Protein Purification

The DPF domain of MORF (aa 211-322) was expressed and purified as described in (Ali et al., 2012). Briefly, unlabeled and 15N-labeled proteins were expressed in E. coli Rosetta-2 (DE3) pLysS cells grown in LB or 15NH4Cl (Sigma-Aldrich) minimal media supplemented with 50 μM ZnCl2. After induction with IPTG (0.5 mM) (Gold biotechnology) for 16 hrs at 18 °C, cells were harvested via centrifugation and lysed by freeze-thaw followed by sonication. The unlabeled and 15N-labeled GST-fusion proteins were purified on glutatahione Sepharose 4B beads (Thermo Fisher Sci). The GST tag was cleaved with Thrombin protease (MP Biomedicals). The proteins were concentrated into PBS buffer pH 6.5, supplemented with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The unlabeled protein was further purified by size exclusion chromatography and concentrated in Millipore concentrators (Millipore).

NMR titrations

1H,15N HSQC spectra were collected at 298K on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer. The binding was monitored by titrating the histone H3K14bu, H3K14ac, H3K14hib and H3K14su peptides (1-19 aa) (synthesized by Synpeptide) to the NMR samples containing 0.15 mM uniformly 15N-labeled MORF DPF in 1xPBS pH 6.5 buffer, supplemented with 5 mM DTT and 8–10% D2O. NMR data were processed and analyzed with NMRPipe and NMRDraw as previously described (Klein et al., 2014b).

Fluorescence spectroscopy

The tryptophan fluorescence measurements were recorded on a Fluoromax-3 spectrofluorometer (HORIBA) at room temperature. The samples of 2 μM MORF DPF and progressively increasing concentrations of the histone peptides, H3K14bu, H3K14ac, H3K14hib and H3K14su in PBS buffer pH 6.5, supplemented with 5 mM DTT were excited at 295 nm. Emission spectra were recorded over a range of wavelengths between 310 and 405 nm with a 0.5 nm step size and a 0.6 s integration time. The Kd values were determined as previously described (Klein et al., 2014b). The Kd values were averaged over three separate experiments, with error calculated as the standard deviation between the runs.

X-Ray Crystallography

Purified MORF DPF (residues 211-322) was concentrated to 10 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 buffer, supplemented with 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM dithiothreitol, and incubated with the H3K14bu (1-19 aa) peptide at a 1:1.5 molar ratio for 1 hour on ice prior crystallization. Crystals of the DPF:H3K14bu complex were grown using hanging-drop diffusion method at 18°C by mixing protein–peptide solution with well solution composed of 1.1 M sodium citrate tribasic and 0.1 M sodium hepes pH 7.0 at a 1:1 ratio. The crystals were soaked in a solution of 1.1 M sodium citrate tribasic and 0.1 M sodium hepes pH 7.0, supplemented with 30% ethylene glycol prior to flash freezing in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected from a single crystal on beamline 4.2.2 at the Advance Light Source administrated by the Molecular Biology Consortium. XDS was use to process the raw diffraction imagines and scale the data (Kabsch, 2010). Processing was completed using ccp4 (Winn et al., 2011). The phase solution was found via molecular replacement using the MOZ DPF:H3 peptide complex structure (PDB ID 4LK9) as a model. Refinement was carried out using Phenix (Adams et al., 2010). The model was built with Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and verified by MOLProbity (Chen et al., 2010).

In vitro HAT assay

In vitro enzymatic assays were carried out by incubating 0.5 μg of each HAT (Gcn5, p300, Pcaf, and CBP) with 10 μg of recombinant histone H3 in the presence of 0.5 mM of short-chain acyl-CoAs (acetyl-, crotonyl-, malonyl-, succinyl-, propionyl-, butyryl-, glutaryl-, and β-hydroxybutyryl CoA - Sigma-Aldrich) in 1X HAT buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 25 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM AEBSF and 5 mM sodium butyrate) for 60 min at 30°C; final volume was 50 μl. HATs Tip60 and MOF were only assayed in the presence of acetyl- and butyryl-CoA. Background control reactions were performed in the absence of HATs. Reactions were stopped by freezing, and samples were dried in a SpeedVac and resuspended in 20 μl of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Histones were derivatized and analyzed by mass spectrometry following procedures described previously (Sidoli et al., 2016). Data analysis was performed using the software EpiProfile with a 10 ppm tolerance for extracting peak areas from raw files (Yuan et al., 2015). The relative abundances of acyl-PTMs were calculated by dividing the intensity the modified peptide by the sum of all modified and unmodified peptides sharing the same sequence.

In vivo acyl-PTMs quantification

HeLa S3 mammalian cells were cultured at 37°C and 5 % CO2 in spinner flasks in Joklik’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) newborn calf serum (HyClone), penicillin-streptomycin (1:100), and 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested, washed with PBS and histone extraction was carried out as described (Sidoli et al., 2016; Sidoli et al., 2015). Histones (50 μg) were resuspended in 20 μl of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and subjected to two cycles of chemical derivatization with propionic anhydride (or d-10 propionic anhydride when identifying propionyl and butyryl histone marks), digested with trypsin for 6 h at 37°C and desalted with C18 stage-tips as described (Sidoli et al., 2016; Sidoli et al., 2015). Spectra were acquired using data-independent acquisition (DIA) as in (Sidoli et al., 2015), and quantification of histone H3K14 PTMs was performed using in-house software EpiProfile (Yuan et al., 2015) with a 10 ppm tolerance for extracting areas from raw files. Relative abundances of modified H3K14 peptide was calculated by diving the area under the curve of a specific modified form of the peptide by all forms of the same given peptide (considered as 100%).

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Software

Software used in this this study has been previously published as detailed in the Key Resources Table.

Data Resources

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 5U2J.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli Rosetta-2 (DE3) pLysS | Ali et al., 2012 | N/A |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Dithiothreitol | Gold Biotechnology | 27565-41-9 |

| H3K14bu, H3K14ac, H3K14hib and H3K14su peptides (1-19 aa) | Synpeptide | N/A |

| 15NH4Cl | Sigma-Aldrich | 299251 |

| IPTG | Gold biotechnology | I2481C100 |

| Glutatahione Sepharose 4B beads | Thermo Fisher Sci | 16101 |

| Thrombin | MP Biomedicals | 154163 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Deposited Data | ||

| Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank | This study | PDB ID 5U2J |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Human: HeLa S3 | N/A | |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid: modified pGEX2T | Ali et al., 2012 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| XDS | Kabsch et al., 2010 | N/A |

| ccp4 | Winn et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Phenix | Adams et al., 2010 | N/A |

| Coot | Emsley et al., 2010 | N/A |

| EpiProfile | Yuan et al., 2015 | N/A |

| MOLProbity | Chen et al., 2010 | N/A |

| Other | ||

HIGLIGHTS.

The DPF domain of the MORF KAT is a reader of global histone H3K14 acylation

The structure of the MORF DPF-H3K14bu complex offers insight into selectivity

MS analysis of H3K14 acylation states in vivo and in vitro is described

Findings support the mechanism by which the MORF KAT promotes spreading of acylation

Acknowledgments

We thank Jay Nix at beam line 4.2.2 of the ALS in Berkeley for help with X-ray crystallographic data collection. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 GM106416, GM101664 and GM100907 to T.G.K., CA196539 and GM110174 to B.A.G., a Leukemia and Lymphoma Robert Arceci Award to B.A.G., and CPRIT (RP160237), Welch (G1719) and Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Career Development Award (1339-17) to X.S. F.H.A is an AHA postdoctoral fellow.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.J.K., J.S., X.W., J.A., F.H.A., and Y.Z. performed experiments and together with J.C., X.S., B.A.G. and T.G.K. analyzed the data. B.J.K., J.S., F.H.A., B.A.G. and T.G.K. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Yan K, Lalonde ME, Degerny C, Rothbart SB, Strahl BD, Cote J, Yang XJ, Kutateladze TG. Tandem PHD fingers of MORF/MOZ acetyltransferases display selectivity for acetylated histone H3 and are required for the association with chromatin. Journal of molecular biology. 2012;424:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews FH, Shinsky SA, Shanle EK, Bridgers JB, Gest A, Tsun IK, Krajewski K, Shi XB, Strahl BD, Kutateladze TG. The Taf14 YEATS domain is a reader of histone crotonylation. Nature chemical biology. 2016a;12:396–U333. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews FH, Strahl BD, Kutateladze TG. Insights into newly discovered marks and readers of epigenetic information. Nature chemical biology. 2016b;12:662–668. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C, Weinert BT, Nishida Y, Verdin E, Mann M. The growing landscape of lysine acetylation links metabolism and cell signalling. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2014;15:536–550. doi: 10.1038/nrm3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreveny I, Deeves SE, Fulton J, Yue B, Messmer M, Bhattacharya A, Collins HM, Heery DM. The double PHD finger domain of MOZ/MYST3 induces alpha-helical structure of the histone H3 tail to facilitate acetylation and methylation sampling and modification. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:822–835. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A, Abmayr SM, Workman JL. Diverse Activities of Histone Acylations Connect Metabolism to Chromatin Function. Molecular cell. 2016;63:547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng YP, Vlassis A, Roques C, Lalonde ME, Gonzalez-Aguilera C, Lambert JP, Lee SB, Zhao XB, Alabert C, Johansen JV, et al. BRPF3-HBO1 regulates replication origin activation and histone H3K14 acetylation. Embo Journal. 2016;35:176–192. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzi A, Zhang D, Huang H, Barral S, Kwon OK, Qi S, Tang Z, Buchou T, Vitte AL, He T, et al. Dynamic Competing Histone H4 K5K8 Acetylation and Butyrylation Are Hallmarks of Highly Active Gene Promoters. Molecular cell. 2016;62:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huan F, Abmayr SM, Workman JL. Regulation of KAT6 Acetyltransferases and Their Roles in Cell Cycle Progression, Stem Cell Maintenance, and Human Disease. Molecular and cellular biology. 2016;36:1900–1907. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00055-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Lin S, Garcia BA, Zhao Y. Quantitative proteomic analysis of histone modifications. Chemical reviews. 2015;115:2376–2418. doi: 10.1021/cr500491u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Sabari BR, Garcia BA, Allis CD, Zhao YM. SnapShot: Histone Modifications. Cell. 2014;159:458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. Xds. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BJ, Lalonde ME, Cote J, Yang XJ, Kutateladze TG. Crosstalk between epigenetic readers regulates the MOZ/MORF HAT complexes. Epigenetics. 2014a;9:186–193. doi: 10.4161/epi.26792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BJ, Piao L, Xi Y, Rincon-Arano H, Rothbart SB, Peng D, Wen H, Larson C, Zhang X, Zheng X, et al. The Histone-H3K4-Specific Demethylase KDM5B Binds to Its Substrate and Product through Distinct PHD Fingers. Cell reports. 2014b;6:325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Sabari BR, Panchenko T, Wen H, Zhao D, Guan H, Wan L, Huang H, Tang Z, Zhao Y, et al. Molecular Coupling of Histone Crotonylation and Active Transcription by AF9 YEATS Domain. Molecular cell. 2016;62:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselman CA, Lalonde ME, Cote J, Kutateladze TG. Perceiving the epigenetic landscape through histone readers. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012;19:1218–1227. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Liu L, Zhao C, Han C, Li F, Zhang J, Wang Y, Li G, Mei Y, Wu M, et al. Combinatorial readout of unmodified H3R2 and acetylated H3K14 by the tandem PHD finger of MOZ reveals a regulatory mechanism for HOXA9 transcription. Genes & development. 2012;26:1376–1391. doi: 10.1101/gad.188359.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabari BR, Tang Z, Huang H, Yong-Gonzalez V, Molina H, Kong HE, Dai L, Shimada M, Cross JR, Zhao Y, et al. Intracellular Crotonyl-CoA Stimulates Transcription through p300-Catalyzed Histone Crotonylation. Molecular cell. 2015;58:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidoli S, Bhanu NV, Karch KR, Wang XS, Garcia BA. Complete Workflow for Analysis of Histone Post-translational Modifications Using Bottom-up Mass Spectrometry: From Histone Extraction to Data Analysis. Jove-J Vis Exp. 2016 doi: 10.3791/54112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidoli S, Simithy J, Karch KR, Kulej K, Garcia BA. Low Resolution Data-Independent Acquisition in an LTQ-Orbitrap Allows for Simplified and Fully Untargeted Analysis of Histone Modifications. Anal Chem. 2015;87:11448–11454. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdin E, Ott M. 50 years of protein acetylation: from gene regulation to epigenetics, metabolism and beyond. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2015;16:258–264. doi: 10.1038/nrm3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, Panchenko T, Yang S, Zhao S, Yan P, Zhang W, Xie W, Li Y, Zhao Y, Allis CD, Li H. Selective recognition of histone crotonylation by double PHD fingers of MOZ and DPF2. Nature chemical biology. 2016;12:1111–1118. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ. MOZ and MORF acetyltransferases: Molecular interaction, animal development and human disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1853:1818–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan ZF, Lin S, Molden RC, Cao XJ, Bhanu NV, Wang XS, Sidoli S, Liu SC, Garcia BA. EpiProfile Quantifies Histone Peptides With Modifications by Extracting Retention Time and Intensity in High-resolution Mass Spectra. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2015;14:1696–1707. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.046011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Zhang Q, Li S, Plotnikov AN, Walsh MJ, Zhou MM. Mechanism and regulation of acetylated histone binding by the tandem PHD finger of DPF3b. Nature. 2010;466:258–262. doi: 10.1038/nature09139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Zeng L, Zhao CC, Ju Y, Konuma T, Zhou MM. Structural Insights into Histone Crotonyl-Lysine Recognition by the AF9 YEATS Domain. Structure. 2016;24:1606–1612. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Guan HP, Zhao S, Mi WY, Wen H, Li YY, Zhao YM, Allis CD, Shi XB, Li HT. YEATS2 is a selective histone crotonylation reader. Cell Research. 2016;26:629–632. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]