Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma is highly refractory cancer which is resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy, carrying a dismal prognosis. Although many anticancer drugs have been developed for treating HCC, sorafenib is the only effective treatment, but it only prolongs survival duration for about 3 months. Recently, oncolytic virotherapy has shown promising results in treating HCCs and the effects can be more enhanced by adopting immune modulatory molecules. This review discusses the current status of treating HCC and the effective strategy of oncolytic virus-based immunotherapy for the treatment of HCCs.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cancer with a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and is the only carcinoma with increasing mortality [1, 2]. The major pathophysiological characteristics of HCC are chronic liver disease with cirrhosis. Etiology of HCC ranges from hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections to metabolic diseases such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [3]. In the last 20 years, the incidence of HCC has increased 62% and over 750,000 new cases are annually identified [4, 5]. Current treatments for HCC have a lot of limitations, because survival is not guaranteed even for patients with localized HCC. For the earliest stage, tumor curative treatments such as resection and percutaneous ablation are feasible, and a 5-year survival rate in these patients ranges from 40% to 70% [6]. However, tumor recurrence for 3 years is observed in 70% of patients after resection or radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Liver transplantation is an effective treatment for cirrhosis and early tumors, but most patients are ineligible because organs are scarce [7]. Moreover, approximately more than 70% of patients with HCC are not eligible for these procedures because most have intermediate or advanced stage disease at the time of diagnosis. For intermediate stage tumors, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) (conventional or drug-eluting beads) is the standard of care [8], but overall survival is usually less than 20 months [9, 10]. For patients with advanced HCC, the survival is dismal because median overall survival is about 7 months [11]. With the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib, the only approved systemic therapy for HCC, this survival can be increased by about 3 months [6]. Besides sorafenib, other target agents, such as sunitinib, brivanib, or linifanib, have not been proven to be superior to sorafenib [12, 13]. Several newer molecules have been shown to confer a survival advantage in a subset of patients [14]. The mean survival of patients with advanced stage HCC is less than 1 year. Most of the target agents are not tumoricidal but tumor-static agents and do not have long lasting antitumor effects after discontinuation. The major factor contributing to such a grim outcome in HCC treatment is the lack of effective therapeutics so far.

Therefore, HCC is considered a highly refractory cancer and is resistant to conventional chemotherapy. To overcome these issues, the focus is shifting from antiangiogenic therapy [15] to novel modalities to improve survival for this deadly disease [16, 17]. HCC is an attractive target for immunotherapy, because of its immunological characteristics like chronic inflammation, with several immunologic mechanisms such as evasion of immune response, immunosuppressive environment, and T cell exhaustion, which are at play to promote HCC development and growth. Several novel approaches geared towards manipulating the immune response to HCC have suggested a therapeutic benefit in early stage clinical trials [18]. Contemporary clinical studies are ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of immunotherapy to reduce the risk of relapse after surgical or percutaneous ablation and prolong survival in intermediated and advanced HCC as monotherapy or in combination.

This review discusses the current status and the barriers of immunotherapy against HCC and effective immunotherapy strategies using oncolytic virus for HCC.

2. Chemotherapy

Treatment options for HCC are divided into three categories as follows: (1) surgical therapies (i.e., resection, cryoablation, and liver transplantation), (2) liver-directed nonsurgical therapies (i.e., percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), radio frequency ablation (RFA), TACE, radiation, and radioembolization), or (3) systemic nonsurgical therapies (chemotherapy, molecular-targeted therapy, and hormone therapy). Since surgical therapies and liver-directed surgical therapies are generally used in the early stages of HCCs and HCC is typically diagnosed late in the course of patient with chronic liver diseases [19], here we will discuss systemic treatment approaches for patients with advanced HCCs. It is reported that the efficacy of cytotoxic chemotherapy is generally limited [20]. Although few randomized trials have been conducted, median survival in all of the studied population has been short (less than 12 months in all cases). Main reasons for this are because of the following: (1) high rate of expression of drug resistance genes such as p-glycoprotein, glutathione-S-transferase, heat shock proteins, and mutations of p53 [21, 22]. (2) Survival is often determined by the degree of hepatic dysfunction, and systemic chemotherapy is usually not well tolerated by patients with significant underlying hepatic dysfunction. (3) Clinical investigations have been undertaken in diverse patient populations. For example, Asian patients are usually younger with well-compensated cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis B and/or C, while North American or European patients with HCC are typically over 60 years old with alcoholic cirrhosis and comorbid illness [23]. (4) Chemotherapy may be less effective overall in patients with significant cirrhosis [24].

2.1. Doxorubicin and Mitoxantrone

Doxorubicin is the most studied chemotherapy agent for advanced HCC. Among the agents tried, doxorubicin-based regimens appear to have the greatest efficacy with response rates of 20–30% and a minimal impact on survival [25]. Mitoxantrone has a similar antitumor efficacy as doxorubicin (response rate 10 to 25%) [26, 27]. Antitumor effect of doxorubicin may be potentiated by tamoxifen [28]. Although 12 out of 38 patients with HCC received doxorubicin plus tamoxifen (32%) that achieved a response, the median progression-free survival was only seven months [29].

2.2. Fluoropyrimidines

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) has broad antitumor efficacy with acceptably low toxicity. Although the response rate with only 5-FU has been low, combination with leucovorin can bring response rates to as high as 28% [30].

2.3. Gemcitabine, Irinotecan, and Thalidomide

Gemcitabine has modest activity at best. It is reported that 5 of 28 patients that received gemcitabine had a partial response of short duration (~13 weeks) [31]. Irinotecan treatment resulted in one partial response for seven months among 14 patients with advanced HCC [32]. A second trial in 29 patients showed no objective partial responses, but 12 patients had disease stabilizations [33]. Thalidomide, an agent with antiangiogenic activity, showed low rate of objective antitumor activity, with disease stabilization in up to one-third of the patients [34].

2.4. Cisplatin-Based Combination Therapy

Cisplatin-based combination therapy appears to show higher objective response rates than that in noncisplatin-based therapy, although it is not clear whether it confers a survival benefit. Cisplatin plus doxorubicin had 18 and 49% objective responses, respectively [35, 36]. The combination therapy of cisplatin and mitoxantrone with continuous infusion of 5-FU showed 24 and 27% responses in two different studies [37, 38]. It was reported that 15% of patients showed response rate for cisplatin and epirubicin infusion [39]. Other combination studies reported 24% for cisplatin and doxorubicin plus capecitabine [40] and 6 and 20% in two studies for cisplatin plus capecitabine [41, 42]. The above data suggest that combination chemotherapy may play a minor role and no chemical drug or regimen has been approved for the treatment of HCC [43].

3. Molecular-Targeted Therapy

Treatment approaches are now directed against a specific molecular defect, which is termed “molecular-targeted therapies.” Although the molecular pathogenesis of HCC remains poorly understood, the following signaling pathways are notably involved: (1) the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/EGF (HER1) in the carcinogenesis and proliferative behavior of HCC [44–49]. (2) HCCs are highly vascular tumors with high levels of expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). (3) Raf/MAP kinase-ERK kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is implicated in HCC tumorigenesis [50, 51]. Therefore, small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) or monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to be the target-specific antigens have been proposed and approved by the FDA for clinical use (Table 1). Among them, only sorafenib is approved for treating HCCs. Sorafenib (Nexavar) is a multitargeted orally active TKI, inhibiting Raf kinase and the VEGFR intracellular kinase pathway [52].

Table 1.

TKI and mAbs approved by FDA for use of cancer therapy.

| Category | Name | Targets | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| TKI | Dasatinib | BCR-ABL, SRC family, c-KIT, PDGFR | Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), acute lymphocytic leukemia |

| Erlotinib | EGFR | Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), pancreatic cancer |

|

| Gefitinib | EGFR | NSCLC | |

| Imatinib | BCR-ABL, c-KIT, PDGFR | Acute lymphocytic leukemia, CML, gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

|

| Lapatinib | HER2/neu, EGFR | Breast cancer | |

| Sorafenib | BRAF, VEGFR, EGFR, PDGFR | Renal cell carcinoma (RCC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) |

|

| Sunitinib | VEGFR, PDGFR, c-KIT, FLT3 | RCC, gastrointestinal stromal tumor | |

| Temsirolimus | mTOR, VEGF | RCC | |

| Pazopanib | VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, PDGF-α/β, and c-KIT |

RCC | |

| Nilotinib | BCR-ABL | CML | |

| Crizotinib | ALK, HGFR | NSCLC | |

| Vemurafenib | BRAF | Late-stage melanoma | |

| mAb | Alemtuzumab | CD52 | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| Bevacizumab | VEGF | Colorectal cancer, NSCLC, RCC | |

| Cetuximab | EFGR | Colorectal cancer, head and neck cancer | |

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | CD33 | Relapsed acute myeloid leukemia | |

| Ibritumomab tiuxetan | CD20 | Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) (with yttrium-90 or indium-111) |

|

| Panitumumab | EGFR | Colorectal cancer | |

| Rituximab | CD20 | NHL | |

| Tositumomab | CD20 | NHL (with iodine-131) | |

| Trastuzumab | HER2/neu | Breast cancer with HER2/neu overexpression | |

| Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | Late-stage melanoma |

4. Oncolytic Virotherapy for HCC Treatment

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) have been recently recognized as an effective treatment for cancer in preclinical models and promising clinical responses in human cancer patients [53]. OVs have a number of advantages over conventional antitumor agent, because they have their own cancer specificity and better safety margin. They selectively target and replicate in cancer cells, as a host cell; thus, OVs survive by lysing cancer cells [54]. OV-mediated oncolysis not only leads to tumor regression but also provides important immune responses. Key signals provided by oncolysis to dendritic cells (DCs) and other antigen-presenting cells (APCs) can then initiate additional potent antitumor immune response [55]. In addition to its oncolytic characteristics, OV can be engineered to express some functional genes. For instance, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) expression in OVs increase tumor cell lysis. GM-CSF is an immune modulator, acts as a paracrine manner on various cells, and recruits circulating neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes to enhance their functions in host defense [56]. As for HCC treatment in clinical trials, adenovirus and vaccinia virus (VV) are mostly used [57, 58].

5. Oncolytic Virus-Based Preclinical Studies

Most of the preclinical studies use adenoviruses and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) as the vector, due to their natural ability to kill or target HCC cells. For instance, adenoviruses have excellent tropism towards hepatocytes [59], in case of VSV, which has intrinsic ability to infect cancer cells [60]. However, various studies have used other viruses like herpes simplex virus (HSV), measles vaccine virus (MeV), newcastle disease virus (NDV), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), and vaccinia virus (VV) [61]. In order to target and enhance therapeutic efficacy of viruses, various genes are engineered in their genome. The anticancer and immunotherapeutic efficacy of these viruses are evaluated in HCC cell lines and animal models (Table 2).

Table 2.

Representative OVs used in preclinical studies.

| Virus strain | Modification | Therapeutic gene | HCC cell lines used | Animal model | Dose (pfu) and route |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus, CV890 |

AFP transcriptional regulatory elements (TRE) to control an artificial E1A-IRES-E1B bicistronic cassette in an ad5 vector |

None, combination with doxorubicin |

HepG2, Huh7, Hep3B, and SNU449 |

BALB/c nude mice Hep3B/HepG2 xenografts |

1 × 1011 IV | [74] |

| Adenovirus, ZD55-TRAIL/ZD55- Smac |

Deletion of E1B 55KDa gene Insertion of EGFP, TRAIL/Smac genes |

TRAIL/Smac | Hep3B, BEL7404, and SMMC7721 |

BALB/c nude mice BEL7404 xenograft |

2 × 109 IT | [67] |

| Adenovirus, CNHK500 | Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) and hypoxia-response promoter controlled the E1b gene |

hTERT | Hep3B, HepGII, and SMMC-7721 |

BALB/c nude mice, SMMC-7721, and Hep3B xenografts |

2 × 108–2 × 109 IT | [68] |

| Adenovirus, CNHK300 | hTERT was inserted with viral genome at upstream of E1A region | hTERT | HepGII and Hep3B | No animal model used | MOI of 5 pfu/cell |

[69] |

| Adenovirus, ZD55-IFN-β |

E1B-55-kDa gene deletions and hIFN-β insertion | hIFN-β | Hep-G2 and BEL7404 | BALB/c nude mice, BEL7404 xenografts |

2 × 109 IT | [70] |

| Adenovirus, SG7011let7T | Insertion of eight copies of let-7 target sites (let7T) into the 39 untranslated region of E1A |

miRNA, let-7 | HepG2, Hep3B, PLC/PRF/5, and Huh7 |

BALB/c nude mice, Hep3B and SMMC-7721 xenografts |

5 × 108 IT | [71] |

| Adenovirus, Telomelysin |

hTERT inserted upstream of the E1 gene |

hTERT | Human: Huh-7, Hep3B, PLC5, HA22T, HCC36, and HepG2 Mouse: Hepa-1c1c7 and Hepa 1–6 |

HBx transgenic mice, orthotopic model |

Low: 1.25 × 108 Medium: 6.25 × 108 High: 3.0 × 109 IT |

[72] |

| Adenovirus, Ad-ΔB/TRAIL and Ad-ΔB/IL-12 |

Mutated in E1A and deleted in E1B regions. Insertion of hTRAIL or hIL-12 |

hTRAIL or hIL-12 | Hep3B and HuH7 | Athymic nude mice, orthotopic model |

2 × 108 1 × 1010 IV |

[73] |

| HSV, designated liver-cancer specific oncolytic virus (LCSOV) |

Viral glycoprotein H gene linked with liver-specific apolipoprotein E (apoE)-AAT promoter. miR-122a complimentary sequence to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR). miR-124a and let-7 also inserted at 3′ UTR |

miR122miR-124a and let-7 |

HuH-7, HepG2, and Hep3B |

Hsd: athymic (nu/nu) mice, Hep3B xenograft |

5 × 106 IT | [75] |

| HSV, G47Δ | ICP47 and γ34.5-deletion |

None | HepG2, HepB, SMMC-7721, BEL-7404, and BEL-7405 | Balb/c nude mice SMMC-7721, BEL-7404 xenograft |

2 × 107 IT | [76] |

| MeV, (Res + MeV) | Encoding of GFP as a marker gene and SCD as suicide gene |

None Combination with HDACi drug resminostat (Res) |

HepG2 and Hep3B | No animal model used | Various MOIs | [89] |

| NDV | L289A mutation within the F gene |

None | HepG2 and Huh7 | Buffalo rats McA-RH7777 rat HCC-orthotopic model |

108 TCID50/rat HAI | [90] |

| VV, JX-594 | Deletion of TK and VGF, insertion of h GM-CSF |

hGM-CSF | None | Immunocompetent, orthotopic, NZW rabbits. VX2 tumor model. Rat: chemically induced HCC |

Rabbit: 1 × 108–1 × 109 IV/IT Rat: 1 × 108 IT |

[79] |

| VV, JX-963 | Deletion of TK and VGF, insertion of h GM-CSF |

hGM-CSF | None | Immunocompetent, orthotopic, NZW rabbits VX2 tumor model |

Various IV | [80] |

| VV, GLV-1 h68 | Deletion of TK and insertion of Renilla luciferasegreen fluorescent protein (Ruc-GFP), β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase |

None | HuH7 and PLC/PRF/5 |

Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu HuH7 and PLC xenografts |

5 × 106 IV | [82] |

| VV, GLV-1 h68 | Deletion of TK and insertion of Renilla luciferasegreen fluorescent protein (Ruc-GFP), β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase |

None | Huh-7, Hep 3B, SNU-449 and SNU-739 |

No animal model used | MOI of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 | [83] |

| VV, GLV-2b-372 | Deletion of TK and insertion of TurboFP635 gene |

None | Huh-7, Hep G2, SNU-449, and SNU-739 |

Athymic nude mice Huh-7 xenograft |

1 × 105 IT | [84] |

| VSV, rVSV-GFP | Insertion of GFP | None | Human: Hep 3B and Hep G2 Rat: McA-RH7777 |

Buffalo rats McA-RH7777 orthotopic, syngeneic |

1 × 108 IT | [85] |

| VSV, rVSV-β-gal | Insertion of β-galactosidase (β-gal) |

None | McA-RH7777 | Buffalo rats McA-RH7777 orthotopic |

1.3 × 107 HAI | [86] |

| VSV, rVSV-NDV/F(L289A) | Insertion of NDV/F | None | Human: Hep 3B and Hep G2 Rat: McA-RH7777 |

Buffalo rats, orthotopic syngeneic McA-RH7777 | 1.3 × 107 HAI | [85–87] |

| VSV, rVSV-NDV/F(L289A) | Insertion of NDV/F | None | Human: Hep 3B and Hep G2 Rat: McA-RH7777 |

Buffalo rats, orthotopic syngeneic McA-RH7777 | 1.3 × 107 HAI | [88] |

| VSV, rVSV(MΔ51)-M3 | MΔ51deletion and M3 addition | None | McA-RH7777 | Buffalo rats McA-RH7777 orthotopic |

5.0 × 107–5.0 × 109 HAI | [69] |

IV: intravenous; IT: intratumoral; MOI: multiplicity of infection.

5.1. Adenoviruses

Adenoviruses are nonenveloped viruses, consist of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) about 36 kb in size. There are seven subgroups reported, based on cross-reactivity patterns of neutralizing antibodies, from A to G. These are further classified as serotypes. As of now, 57 serotypes have been reported. The pathogenicity and tissue tropism are similar within the subgroups [62]. Adenovirus 5 (Ad5) subtype has been extensively used in oncolytic virotherapy as a vector [63]. Most of the preclinical studies have used adenovirus as a vector to transfer a transgene. Modifications in E1A and E1B genes of adenovirus have made it as oncolytic vector against the cancer cells [64]. The E1A gene is responsible for inactivation of several proteins, including retinoblastoma, allowing entry into S-phase [65]. The E1B inactivates p53, thus preventing apoptosis. A high resistance to tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis–inducing ligand (TRAIL) has been reported in the HCC cells [66] whereas TRAIL is known to selectively induce apoptosis in malignant cells.

In order to overcome to this hurdle, adenovirus vector, ZD55, was constructed with -Smac (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases)/TRAIL as ZD55-Smac/ZD55-TRAIL. The combined antitumor effect of these vectors was evaluated in mice xenograft models and cell lines. A significant regression of tumor size was reported in contrast to partial effect of single treatment of ZD55-Smac or ZD55-TRAIL. Moreover, in vitro-based analysis showed activation of caspases and significant reduction of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) expression [67]. Various transgenes have been inserted in those regions for selective targeting of HCC cells. A dual-regulated adenovirus variant CNHK500, in which human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) drove the Ad5 E1a gene and hypoxia-response promoter controlled the E1b gene, was engineered. The efficacy of this virus was checked in HCC cell lines and animal models in terms of tumor targeting, which showed selective gene expression, tumor regression, and prolonged survival period. The results compared with those of CNHK300 confirmed antitumor efficacy and selective replication of CNHK500 in HCC models [68].

Another viral strain, a monoregulated adenovirus CNHK300, was constructed with hTERT, and its antitumor efficacy was evaluated in different cell lines. The detection of hTERT expression and cytotoxicity, especially at low multiplicity of infection (MOI), confirmed the oncolytic activity of CNHK300 [69]. ZD55-IFN-β was generated by homologous recombination of ZD55 vector with interferon-β (IFN-β) containing vector. The antitumor efficacy and IFN-β expression of ZD55-IFN-β were evaluated in HCC cell lines and mice xenograft model. In contrast to Ad5-IFN-β-treated model, 100% cytopathic effect was examined in cell lines and more IFN-β expression were observed in both ZD55-IFN-β received mice and cell lines. This study confirmed the ability of adenovirus as a carrier of potential anticancer genes [70].

SG7011let7T was constructed as adenovirus with microRNA (miRNA), let-7. It was generated as introducing eight copies of let-7 target sites (let7T) into the 39 untranslated regions of E1A. A higher selective replication and cytotoxicity were reported in HCC cell lines when compared to normal liver cell lines. These were also verified in animal models [71]. Telomelysin, an adenovirus with hTERT insertion, had selective replication in HCC cell lines. At a low MOI, ranging 0.77–6.35 pfu, Telomelysin caused HCC cell lysis, but not normal liver cells. These results were confirmed in both in vitro in cell culture and in vivo using an immunocompetent in situ orthotopic HCC model [72].

Adenoviruses armed with apoptosis-induced and immune-stimulatory molecules, such as human TRAIL and IL-12, were constructed as Ad-ΔB/TRAIL and Ad-ΔB/IL-12, respectively. The combined antitumor effects of these vectors were evaluated in Hep3B and HuH7 HCC cell lines. In addition, in vivo efficacy was examined in transplanted Hep3B-orthotopic model. A significant reduction in tumor size of orthotopic model and increased HCC cell death in cell culture were reported. Interestingly, this study documented a remarkable suppression of VEGF with infiltration of natural killer cells (NK cells) and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) at tumor microenvironment (TME). Moreover, enhanced apoptosis and upregulation of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production were also reported in this study [73]. In addition, a combination of doxorubicin with α-fetoprotein- (AFP-) E1A-IRES-E1B bicistronic cassette derived from Ad5, CV890 showed a synergic antitumor effect in vitro as well as in vivo [74].

5.2. Herpes Simplex Viruses

Herpes simplex viruses (HSV) consist of dsDNA (154 kb) as genetic material. Cell receptors, such as herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), nectin 1, and nectin 2, are used for cell entry. Using HSV as an oncolytic agent, only very few studies were conducted in HCC model. In order to enhance HCC cell-specific tropism, liver-cancer-specific oncolytic virus (LCSOV) was created. It was constructed by linking the essential viral glycoprotein H gene with the liver specific apolipoprotein E (apoE)-AAT promoter. Then, miR-122a complimentary sequence was further inserted to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR). In addition, let-7 was also engineered into the same 3′UTR to increase the safety of this virus. The highly selective replication and tumor cell lysis were reported in xenograft as well as in cell culture models [75]. HSV, G47Δ vector was tested for its antitumor efficacy and cytotoxicity in various HCC cell lines. More than 95% cell toxicity was documented in HepG2, Hep3B, and SMMC-7721 cell lines on day 5 with MOI of 0.01. Intratumoral (IT) injection of G47Δ caused reduction in tumor size and prolonged survival of mice [76].

5.3. Vaccinia Virus

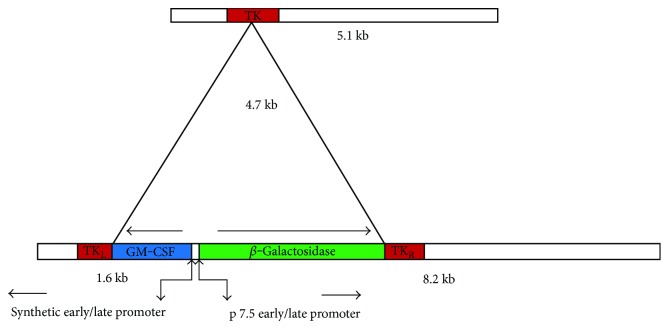

VV possesses 190 kb dsDNA as genetic material and widely used in oncolytic virotherapy because of its widest tropism in both mice and human cells [77, 78]. The antitumor and immunotherapeutic efficacies of Wyeth and Lister strains of VV have been demonstrated in preclinical studies. JX-594 from Wyeth strain was constructed by adding human granulocyte microphage colony-stimulating factor (hGM-CSF) and deleting viral thymidine kinase (vTK) (Figure 1). Intratumoral (IT)/intravenous (IV) administration of JX-594 in liver cancer models of rabbits and mice showed its anticancer ability against tumors. In addition, eradication of lung metastases from liver tumors was reported in rabbits [79]. The anticancer efficacy of JX-963 (a Western Reserve strain encoding hGM-CSF) was evaluated in HCC, in which rabbits were used as animal models. No significant toxicity was reported in this study. Moreover, a significant increased populations of neutrophils, monocytes, and basophils were found in peripheral blood. In addition, hGM-CSF expression and cytotoxic T cell population were observed at tumor site [80, 81]. The Lister strain, GLV 1h 68, was evaluated for colonization and replication efficiency in HCC. In a xenograft model, a reduction in tumor size and upregulated proinflammatory cytokines level were observed. These results confirmed the antitumor efficacy of GLV 1h 68 against HCC [82]. Interestingly, its efficacy was not affected in sorafenib-resistant HCC cell lines. Antitumor effect of GLV 1h 68 against sorafenib-resistant HCC cells was also observed in vitro. The replication efficacy and infectivity of virus showed similar results in sorafenib-resistant HCC cells when compared to parental HCC cells [83]. GLV-2b372 was generated by inserting TurboFP635 into TK locus of LIVP 1.1.1 cassette for real time monitoring of viral infection. Infectivity, selective replication, biodistribution, and antitumor efficacy were evaluated in various cell panels. 80% of cell death was seen in dose- and concentration-dependent manner in cell lines. Significant viral presence was detected at tumor sites. IT injection of viral strain reduced tumor size in athymic nude mice as a flank xenograft model [84].

Figure 1.

JX-594 was generated as insertion of human GM-CSF and β-galactosidase at in between early/late promoter of TK gene. GM-CSF is an immune-stimulatory cytokine, which induces immune response against tumor cells.

5.4. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus

VSV consists of single strand RNA (ssRNA) as a genetic material. Due to its intrinsic infectivity against cancer cells, most of the earlier preclinical studies used VSV for oncolytic virotherapy. VSV was recombined with green fluorescence protein (GFP) to examine antitumor efficacy and toxicity in HCC cell panels. The efficient selective replication and cytotoxicity were documented. IT injection of the virus in rat liver showed tumor destruction and tumor growth inhibition, which leads to prolonged survival of animals [85]. Hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) of rVSV-β-gal into Buffalo rats bearing orthotopically implanted multifocal HCC showed efficient viral transduction, tumor-selective viral replication, and extensive oncolysis. There were no significant vector-associated toxicities and damage to the hepatic parenchyma reported, whereas prolonged survival was reported in vector-treated group [86]. Recombinant VSV was generated by insertion of a transcription unit expressing a control or fusion protein derived from NDV. Extensive syncytia formation and enhanced cytotoxic effects were observed in both in vivo and in vitro models. Interestingly, no toxicities were found in liver and parenchymal tissues [87]. Antiviral actions of alpha/beta interferon (IFN-α/β) was checked in rVSV-NDV/F- (L289A-) treated HCC cell lines and rat models. Potential replication efficacy and no toxicity were documented as major outcomes. This study reported an increased index of oncolytic VSV virotherapy in interferon-treated advanced HCC models [88]. In order to improve the oncolytic potency of VSV, VSV (MΔ51) was modified as rVSV (MΔ51)-M3, vector expressing M3, a chemokine-binding protein with broad-spectrum and high affinity from murine gammaherpesvirus-68. This vector was used to treat rats bearing multifocal lesions of HCC. Treatment resulted in a significant reduction of neutrophil and natural killer cell accumulation in the lesions, a 2-log elevation of intratumoral viral titer with enhanced necrosis. There were no apparent systemic and organ toxicities reported in the treated animals [69].

5.5. Other Oncolytic Viruses

The effect of the combination of an oncolytic MeV with the novel oral HDACi resminostat (Res) was checked in HCC cell panels. The combination effect showed a boosted cytotoxic effect as an enhanced induction of apoptosis with improved rate of primary infections [89]. In order to enhance therapeutic efficacy, a novel NDV vector harboring an L289A mutation within the F (fusion protein) gene was generated; membrane fusion and cytotoxicity were examined in HCC cell lines and orthotopic liver tumors. Tumor-specific syncytia formation and necrosis without toxicity to neighboring parenchyma were observed. Furthermore, when compared with control NDV, the improved oncolysis conferred by the L289A mutation was translated to significantly prolonged survival of rNDV/F- (L289A-) treated mice [90].

6. Oncolytic Virus and Immunotherapy-Based Clinical Trials for HCC

Despite a number of OVs were tried in the preclinical studies, only a few among them have entered into the clinical studies (Table 3). The reasons are different ranging from biodistribution to toxicity. Adenovirus-based trials showed failure in reduced disease progression, but good tolerability of dI1520 vector [91]. Most of the studies used vaccinia such as JX-594 from Wyeth strain for the treatment of HCC patients due to its remarkable outcomes in preclinical and clinical trials [77, 78, 81, 92]. The phase I studies have confirmed the anticancer efficacy and immunotherapeutic effect of JX-594 in HCC. The safety and maximum tolerated dose (MTD) were evaluated in liver cancer patients. IT administration in metastatic primary liver tumors showed a significant regression in tumor size. The replication of JX-594 and GM-CSF expression were also confirmed in this study. As the adverse events, grade I–III flu-like symptoms grade, dose-related thrombocytopenia, and grade III hyperbilirubinaemia were experienced by patients when received 1 × 109 pfu [93]. In order to demonstrate antivascular and immunostimulatory properties of JX-594, IT administration in three hepatitis B virus- (HBV-) infected HCC patients was done. This study showed some interesting outcomes, along with the induction of antivascular cytokines and distant tumor targeting, with it suppressed HBV infection [93].

Table 3.

Clinical trial outcomes in HCC patients.

| Virus strain | Modification | Phase | Dose (pfu) | Route | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus, dl1520 | E1B deletion | I | 3 × 1011 | IV | Tolerability was shown in patients but failed to reduce the disease progression |

[91] |

| Vaccinia virus, JX-594 |

Deletion of TK and VGF, insertion of human GM-CSF | I | 108, 3 × 108, 109, or 3 × 109 | IT | Well toleration, 1 × 109 pfu, was maximum-tolerated dose (MTD) and hyperbilirubinemia noted as the dose-limiting toxicity |

[93] |

| Vaccinia virus, JX-594 | Deletion of TK and VGF, insertion of human GM-CSF | I | 3 × 106 | IT | Induction of antivascular cytokines and suppressed HBV replication in the patients |

[93] |

| Vaccinia virus, JX-594 | Deletion of TK and VGF, insertion of human GM-CSF | I | 108 or 109 | IT | Safety and efficacy of JX-594 followed by sorafenib: well toleration and tumor perfusion |

[92] |

| Vaccinia virus, JX-594 | Deletion of TK and VGF, insertion of human GM-CSF | II | 108 or 109 | Intravascular fusion | Subject survival duration was significantly related to high dose of JX-594 |

[81] |

A sequential therapy of JX-594, followed by sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor and antagonist to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) in three HCC patients, showed well-tolerance, associated with significantly decreased tumor perfusion and tumor responses (Choi criteria; up to 100% necrosis) [92]. In addition, phase II randomized dose-finding clinical trials showed that survival duration of patients was significantly related to viral dose. The results were confirmed by objective intrahepatic modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (mRECIST) (15%) and Choi (62%) response rates. Furthermore, intrahepatic disease control (50%) were equivalent in injected site and distant noninjected tumor sites at both doses. Infusion of low- or high-dose JX-594 into liver tumors (days 1, 15, and 29) were used in this study [81].

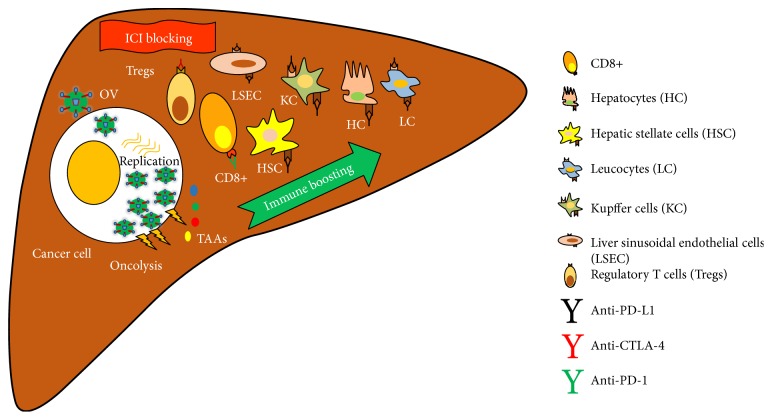

7. Summary and Future Perspectives

Due to limitations in conventional therapies for HCC, new treatment approaches have been established using modern molecular techniques. Oncolytic virotherapy is using oncolytic viruses which selectively infect and kill cancer cells. In order to enhance immunity against cancer cells, genes elevating onco-immunity have been engineered within oncolytic virus. Past and ongoing clinical trials have investigated anticancer efficacy and toxicities of oncolytic viruses, particularly JX-594 (GM-CSF encoding VV) for HCC treatment. GM-CSF as an immune-stimulatory cytokine boosts host immune activity through the infiltration of dendritic cells (DCs) and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at tumor sites. Despite these outcomes have shown favorable results for prognosis of HCC treatment, as an immunotherapeutic approach, more advanced methods, that is, combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) such as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and/or programmed cell death protein 1(PD-1), would be taken into the account (Figure 2). This is because of “tolerogenic” nature of the liver; it expresses more immune checkpoints associated molecules. At present, antitumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) drugs like Nivolumab and Ipilimumab are being evaluated in various clinical trials. Completed trial results showed positive outcomes in HCC treatment [94]. Therefore, combination therapy approaches as oncolytic virotherapy with immune checkpoint blockades may accelerate treatment. Moreover, genetically engineered oncolytic virus with mAbs can be generated for advancement treatment in HCC models. Development of biomarker to monitor the treatment outcomes and toxicities would be very helpful in the translational medicinal research.

Figure 2.

Future prospective for HCC treatment: combination therapy of oncolytic virus with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) blockades. Oncolytic virus enters into cancer cells and replicates in cytosol. It causes oncolysis and activation of neoantigens, which was released from lysed cancer cells. This phenomenon activates immune mechanism against surrounding cancer cells. ICI blockades inhibits action of CTLA-4, PD-L1, and PD-L2 in the liver cells.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Biomedical Research Institute Grant and Busan Cancer Center Grant (2015-23), Pusan National University Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests in this study.

References

- 1.Bruix J., Sherman M., D. American Association for the Study of Liver Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farazi P. A., DePinho R. A. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2006;6(9):674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perz J., Armstrong G., Farrington L., Hutin Y. J. F., Bell B. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. Journal of Hepatology. 2006;45(4):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arzumanyan A., Reis H. M. G. P. V., Feitelson M. Pathogenic mechanisms in HBV- and HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2013;13(2):123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrc3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology. 2012;56(4):908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attwa M., El Etreby S. Guide for diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World Journal of Hepatology. 2015;7(12):1632–1651. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i12.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieghart W., Hucke F., Peck Radosavljevic M. Transarterial chemoembolization: modalities, indication, and patient selection. Journal of Hepatology. 2015;62(5):1187–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sangro B., Carpanese L., Cianni R., et al. Survival after yttrium-90 resin microsphere radioembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma across Barcelona clinic liver cancer stages: a European evaluation. Hepatology. 2011;54(3):868–878. doi: 10.1002/hep.24451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llovet J., Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37(2):429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannini E., Farinati F., Ciccarese F., et al. Prognosis of untreated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):184–190. doi: 10.1002/hep.27443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cainap C., Qin S., Huang W.-T., et al. Linifanib versus sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(2):172–179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng A.-L., Kang Y.-K., Lin D.-Y., et al. Sunitinib versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular cancer: results of a randomized phase III trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(32):4067–4075. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.8372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santoro A., Rimassa L., Borbath I., et al. Tivantinib for second-line treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet Oncology. 2013;14(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo S. Y., Kwon S. M. Angiogenesis and its therapeutic opportunities. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:p. 11. doi: 10.1155/2013/127170.127170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo H. Y., Yoo S. Y., Heo J. New chemical treatment options in second-line hepatocellular carcinoma: what to do when sorafenib fails? Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2017;18(1):35–44. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2016.1261825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong Y.-P., Li Z.-D., Prasoon P., Zhang Q. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: from basic research to clinical use. World Journal of Hepatology. 2015;7(7):980–992. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i7.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pardee A. D., Butterfield L. H. Immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: unique challenges and clinical opportunities. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1(1):48–55. doi: 10.4161/onci.1.1.18344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.C. t. c. o. t. l. i. p. Investigators. A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators. Hepatology. 1998;28(3):751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng G. L., Zeng S., Shen H. Chemotherapy and target therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: new advances and challenges. World Journal of Hepatology. 2015;7(5):787–798. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i5.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soini Y., Virkajarvi N., Raunio H., Paakko P. Expression of P-glycoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: a potential marker of prognosis. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1996;49(6):470–473. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.6.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caruso M. L., Valentini A. M. Overexpression of p53 in a large series of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a clinicopathological correlation. Anticancer Research. 1999;19(5B):3853–3856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGlynn K. A., Petrick J. L., London W. T. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: an emphasis on demographic and regional variability. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2015;19(2):223–238. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagahama H., Okada S., Okusaka T., et al. Predictive factors for tumor response to systemic chemotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;27(5):321–324. doi: 10.1093/jjco/27.5.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeo W., Mok T. S., Zee B., et al. A randomized phase III study of doxorubicin versus cisplatin/interferon α-2b/doxorubicin/fluorouracil (PIAF) combination chemotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(20):1532–1538. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colleoni M., Buzzoni R., Bajetta E., et al. A phase II study of mitoxantrone combined with beta-interferon in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;72(11):3196–3196. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931201)72:11<3196::AID-CNCR2820721111>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunk A., Scott S., Johnson P., et al. Mitozantrone as single agent therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase II study. Journal of Hepatology. 1985;1(4):395–404. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(85)80777-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng A.-L., Chuang S.-E., Fine R. L., et al. Inhibition of the membrane translocation and activation of protein kinase C, and potentiation of doxorubicin-induced apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by tamoxifen. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1998;55(4):523–531. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(97)00594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng A. L., Yeh K. H., Fine R. L., et al. Biochemical modulation of doxorubicin by high-dose tamoxifen in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 1998;45(24):1955–1960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patt Y. Z., Hassan M. M., Aguayo A., et al. Oral capecitabine for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and gallbladder carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101(3):578–586. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang T. S., Lin Y. C., Chen J. S., Wang H. M., Wang C. H. Phase II study of gemcitabine in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89(4):750–756. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000815)89:4<750::AID-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Reilly E. M., Stuart K. E., Sanz-Altamira P. M., et al. A phase II study of irinotecan in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;91(1):101–105. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<101::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boige V., Taïeb J., Hebbar M., et al. Irinotecan as first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter phase II study with dose adjustment according to baseline serum bilirubin level. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(4):456–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patt Y. Z., Hassan M. M., Lozano R. D., et al. Thalidomide in the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase II trial. Cancer. 2005;103(4):749–755. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee J., Park J. O., Kim W. S., et al. Phase II study of doxorubicin and cisplatin in patients with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2004;54(5):385–390. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Czauderna P., Mackinlay G., Perilongo G., et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: results of the first prospective study of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(12):2798–2804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang T.-S., Chang H.-K., Chen J.-S., Lin Y.-C., Liau C.-T., Chang W.-C. Chemotherapy using 5-fluorouracil, mitoxantrone, and cisplatin for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: an analysis of 63 cases. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;39(4):362–369. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikeda M., Okusaka T., Ueno H., Takezako Y., Morizane C. A phase II trial of continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil, mitoxantrone, and cisplatin for metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103(4):756–762. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boucher E., Corbinais S., Brissot P., Boudjema K., Raoul J.-L. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with systemic chemotherapy combining epirubicin, cisplatinum and infusional 5-fluorouracil (ECF regimen) Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2002;50(4):305–308. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park S. H., Lee Y., Han S. H., et al. Systemic chemotherapy with doxorubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine for metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2006;6(1):p. 1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shim J. H., Park J.-W., Nam B. H., Lee W. J., Kim C.-M. Efficacy of combination chemotherapy with capecitabine plus cisplatin in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2009;63(3):459–467. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0759-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J., Lee K., Oh D., et al. Combination chemotherapy with capecitabine and cisplatin for patients with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Annals of Oncology. 2009;20(8):1402–1407. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nowak A. K., Chow P. K., Findlay M. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. European Journal of Cancer. 2004;40(10):1474–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huether A., Höpfner M., Sutter A. P., Schuppan D., Scherübl H. Erlotinib induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in hepatocellular cancer cells and enhances chemosensitivity towards cytostatics. Journal of Hepatology. 2005;43(4):661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hung W., Chuang L., Tsai J.-H., Chang C.-C. Effects of epidermal growth factor on growth control and signal transduction pathways in different human hepatoma cell lines. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology International. 1993;30(2):319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carr B. I., Yamaguchi K., Nalesnik M. A. Concomitant and isolated expression of TGF-alpha and EGF-R in human hepatoma cells supports the hypothesis of autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine growth of human hepatoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 1995;58(4):240–245. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930580409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyaki M., Sato C., Sakai K., et al. Malignant transformation and EGFR activation of immortalized mouse liver epithelial cells caused by HBV enhancer-X from a human hepatocellular carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2000;85(4):518–522. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000215)85:4<518::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Höpfner M., Sutter A. P., Huether A., Schuppan D., Zeitz M., Scherübl H. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor by gefitinib for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology. 2004;41(6):1008–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas M. B., Abbruzzese J. L. Opportunities for targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(31):8093–8108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huynh H., Nguyen T. T. T., Chow K.-H. K.-P., Tan P. H., Soo K. C., Tran E. Over-expression of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK)-MAPK in hepatocellular carcinoma: its role in tumor progression and apoptosis. BMC Gastroenterology. 2003;3(1):p. 1. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gollob J. A., Wilhelm S., Carter C., Kelley S. L. Role of Raf kinase in cancer: therapeutic potential of targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK signal transduction pathway. Seminars in Oncology. 2006;33(4):392–406. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu L., Cao Y., Chen C., et al. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Research. 2006;66(24):11851–11858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russell S. J., Peng K.-W., Bell J. C. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nature Biotechnology. 2012;30(7):658–670. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo Z. S., Thorne S. H., Bartlett D. L. Oncolytic virotherapy: molecular targets in tumor-selective replication and carrier cell-mediated delivery of oncolytic viruses. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Cancer. 2008;1785(2):217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaufman H. L., Kohlhapp F. J., Zloza A. Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2015;14(9):642–662. doi: 10.1038/nrd4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanerva A., Nokisalmi P., Diaconu I., et al. Antiviral and antitumor T-cell immunity in patients treated with GM-CSF–coding oncolytic adenovirus. Clinical Cancer Research. 2013;19(10):2734–2744. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Downs-Canner S., Guo Z. S., Ravindranathan R., et al. Phase 1 study of intravenous oncolytic poxvirus (vvDD) in patients with advanced solid cancers. Molecular Therapy. 2016;24(8):1492–1501. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samson A., Bentham M. J., Scott K., et al. Oncolytic reovirus as a combined antiviral and anti-tumour agent for the treatment of liver cancer. Gut. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shayakhmetov D. M., Gaggar A., Ni S., Li Z. Y., Lieber A. Adenovirus binding to blood factors results in liver cell infection and hepatotoxicity. Journal of Virology. 2005;79(12):7478–7491. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7478-7491.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hastie E., Grdzelishvili V. Z. Vesicular stomatitis virus as a flexible platform for oncolytic virotherapy against cancer. The Journal of General Virology. 2012;93(Pt 12):2529–2545. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.046672-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang J. F., Chen P. J., Sze D. Y., et al. Oncolytic virotherapy for advanced liver tumours. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2009;13(7):1238–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ginsberg H. S. The Adenoviruses. US: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wold W. S. M., Toth K. Adenovirus vectors for gene therapy, vaccination and cancer gene therapy. Current Gene Therapy. 2013;13(6):421–433. doi: 10.2174/1566523213666131125095046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chu R. L., Post D. E., Khuri F. R., Van Meir E. G. Use of replicating oncolytic adenoviruses in combination therapy for cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(16):5299–5312. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0349-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferrari R., Gou D., Jawdekar G., et al. Adenovirus small E1A employs the lysine acetylases p300/CBP and tumor suppressor Rb to repress select host genes and promote productive virus infection. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014;16(5):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pathil A., Armeanu S., Venturelli S., et al. HDAC inhibitor treatment of hepatoma cells induces both TRAIL-independent apoptosis and restoration of sensitivity to TRAIL. Hepatology. 2006;43(3):425–434. doi: 10.1002/hep.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pei Z., Chu L., Zou W., et al. An oncolytic adenoviral vector of Smac increases antitumor activity of TRAIL against HCC in human cells and in mice. Hepatology. 2004;39(5):1371–1381. doi: 10.1002/hep.20203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Q., Chen G., Peng L., et al. Increased safety with preserved antitumoral efficacy on hepatocellular carcinoma with dual-regulated oncolytic adenovirus. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12(21):6523–6531. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu L., Huang T.-g., Meseck M., et al. rVSV (MΔ51)-M3 is an effective and safe oncolytic virus for cancer therapy. Human Gene Therapy. 2008;19(6):635–647. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He L. F., Gu J. F., Tang W. H., et al. Significant antitumor activity of oncolytic adenovirus expressing human interferon-β for hepatocellular carcinoma. The Journal of Gene Medicine. 2008;10(9):983–992. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jin H., Lv S., Yang J., et al. Use of microRNA Let-7 to control the replication specificity of oncolytic adenovirus in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PloS One. 2011;6(7, article e21307) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin W. H., Yeh S. H., Yang W. J., et al. Telomerase-specific oncolytic adenoviral therapy for orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma in HBx transgenic mice. International Journal of Cancer. 2013;132(6):1451–1462. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.El-Shemi A. G., Ashshi A. M., Na Y., et al. Combined therapy with oncolytic adenoviruses encoding TRAIL and IL-12 genes markedly suppressed human hepatocellular carcinoma both in vitro and in an orthotopic transplanted mouse model. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2016;35(1):p. 1. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0353-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li Y., Yu D.-C., Chen Y., et al. A hepatocellular carcinoma-specific adenovirus variant, CV890, eliminates distant human liver tumors in combination with doxorubicin. Cancer Research. 2001;61(17):6428–6436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fu X., Rivera A., Tao L., De Geest B., Zhang X. Construction of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus that precisely targets hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Molecular Therapy. 2012;20(2):339–346. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang J., Xu L., Zeng W., et al. Treatment of human hepatocellular carcinoma by the oncolytic herpes simplex virus G47delta. Cancer Cell International. 2014;14(1):p. 1. doi: 10.1186/s12935-014-0083-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Badrinath N., Heo J., Yoo S. Y. Viruses as nanomedicine for cancer. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2016;11:4835–4847. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S116447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yoo S. Y., Bang S. Y., Jeong S. N., Kang D. H., Heo J. A cancer-favoring oncolytic vaccinia virus shows enhanced suppression of stem-cell like colon cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(13):16479–16489. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim J., Oh J., Park B., et al. Systemic armed oncolytic and immunologic therapy for cancer with JX-594, a targeted poxvirus expressing GM-CSF. Molecular Therapy. 2006;14(3):361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee J., Roh M., Lee Y., et al. Oncolytic and immunostimulatory efficacy of a targeted oncolytic poxvirus expressing human GM-CSF following intravenous administration in a rabbit tumor model. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2010;17(2):73–79. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heo J., Reid T., Ruo L., et al. Randomized dose-finding clinical trial of oncolytic immunotherapeutic vaccinia JX-594 in liver cancer. Nature Medicine. 2013;19(3):329–336. doi: 10.1038/nm.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gentschev I., Müller M., Adelfinger M., et al. Efficient colonization and therapy of human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) using the oncolytic vaccinia virus strain GLV-1h68. PloS One. 2011;6(7, article e22069) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ady J. W., Heffner J., Mojica K., et al. Oncolytic immunotherapy using recombinant vaccinia virus GLV-1h68 kills sorafenib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma efficiently. Surgery. 2014;156(2):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ady J. W., Johnsen C., Mojica K., et al. Oncolytic gene therapy with recombinant vaccinia strain GLV-2b372 efficiently kills hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 2015;158(2):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ebert O., Shinozaki K., Huang T.-G., Savontaus M. J., García-Sastre A., Woo S. L. Oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus for treatment of orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma in immune-competent rats. Cancer Research. 2003;63(13):3605–3611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shinozaki K., Ebert O., Kournioti C., Tai Y.-S., Woo S. L. Oncolysis of multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma in the rat liver by hepatic artery infusion of vesicular stomatitis virus. Molecular Therapy. 2004;9(3):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ebert O. Syncytia induction enhances the oncolytic potential of vesicular stomatitis virus in virotherapy for cancer. Cancer Research. 2004;64(9):3265–3270. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shinozaki K., Ebert O., Suriawinata A., Thung S. N., Woo S. L. Prophylactic alpha interferon treatment increases the therapeutic index of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus virotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in immune-competent rats. Journal of Virology. 2005;79(21):13705–13713. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13705-13713.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ruf B., Berchtold S., Venturelli S., et al. Combination of the oral histone deacetylase inhibitor resminostat with oncolytic measles vaccine virus as a new option for epi-virotherapeutic treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular Therapy Oncolytics. 2015;2:p. 15019. doi: 10.1038/mto.2015.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Altomonte J., Marozin S., Schmid R. M., Ebert O. Engineered newcastle disease virus as an improved oncolytic agent against hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular Therapy. 2010;18(2):275–284. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Habib N., Salama H., Abd El Latif AbuMedian A., et al. Clinical trial of E1B-deleted adenovirus (dl1520) gene therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2002;9(3):254–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Heo J., Breitbach C. J., Moon A., et al. Sequential therapy with JX-594, a targeted oncolytic poxvirus, followed by sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: preclinical and clinical demonstration of combination efficacy. Molecular Therapy. 2011;19(6):1170–1179. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Park B.-H., Hwang T., Liu T.-C., et al. Use of a targeted oncolytic poxvirus, JX-594, in patients with refractory primary or metastatic liver cancer: a phase I trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9(6):533–542. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hato T., Goyal L., Greten T. F., Duda D. G., Zhu A. X. Immune checkpoint blockade in hepatocellular carcinoma: current progress and future directions. Hepatology. 2014;60(5):1776–1782. doi: 10.1002/hep.27246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]