Abstract

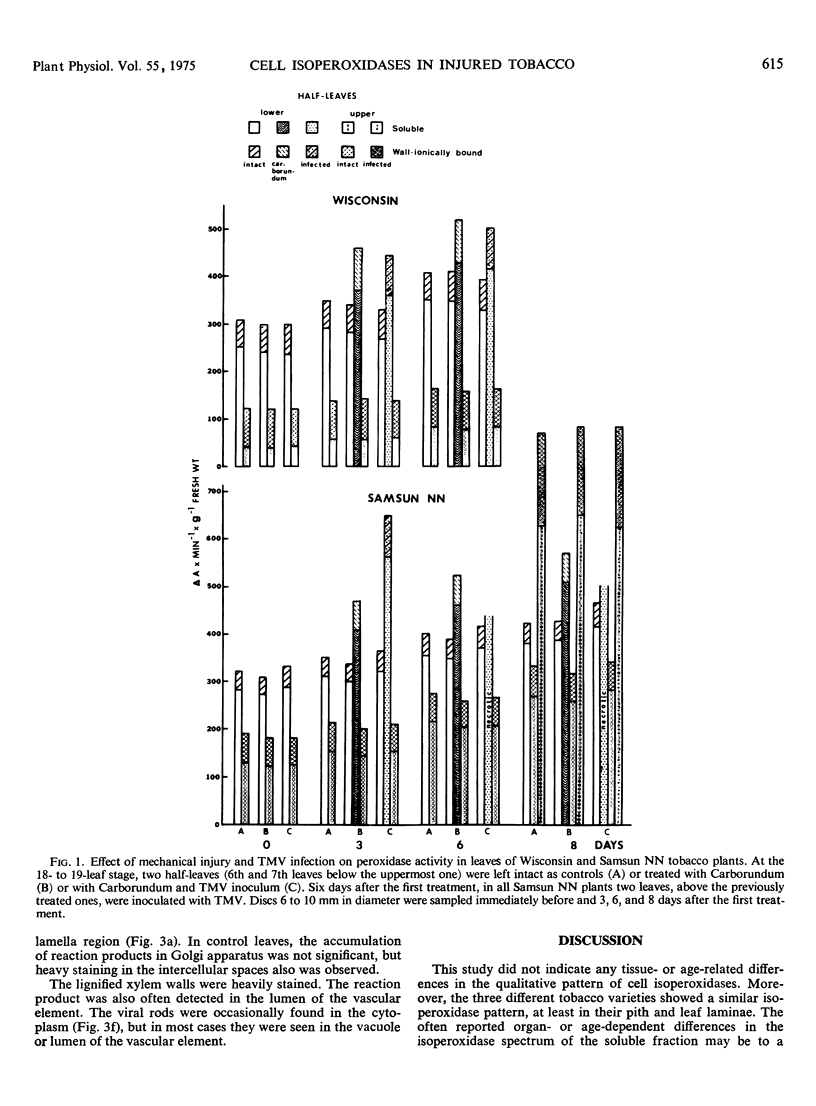

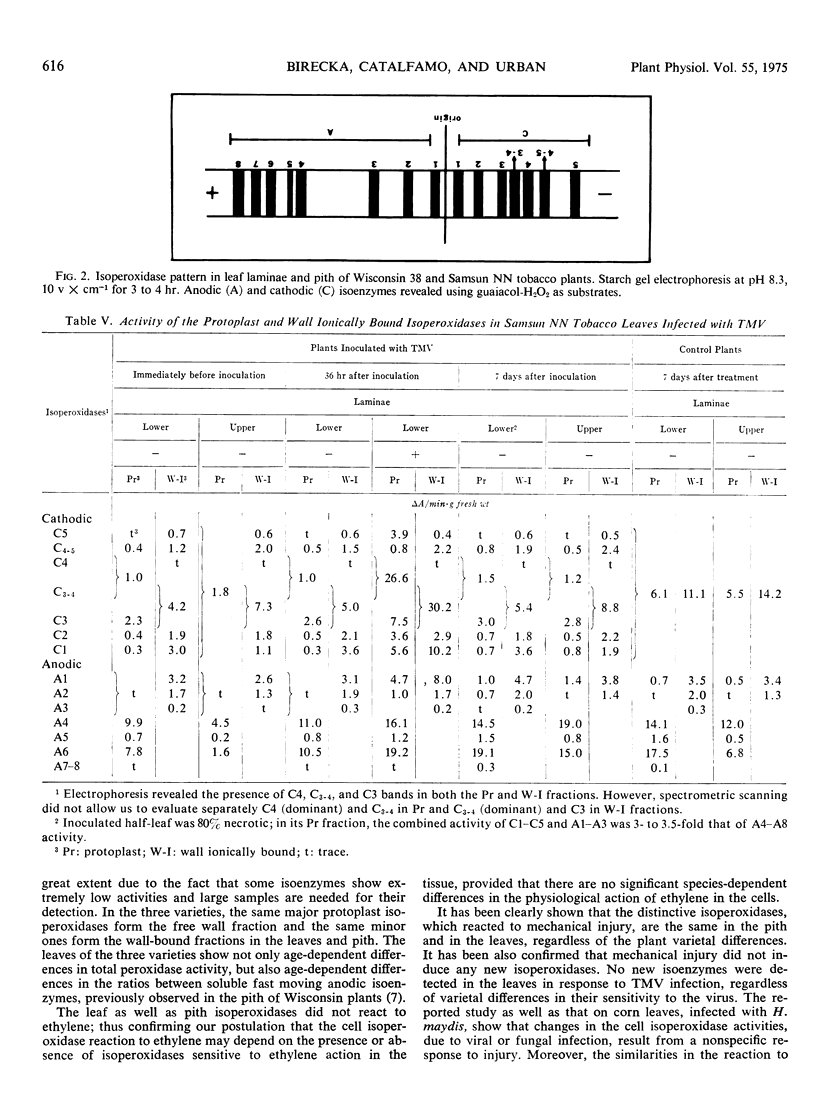

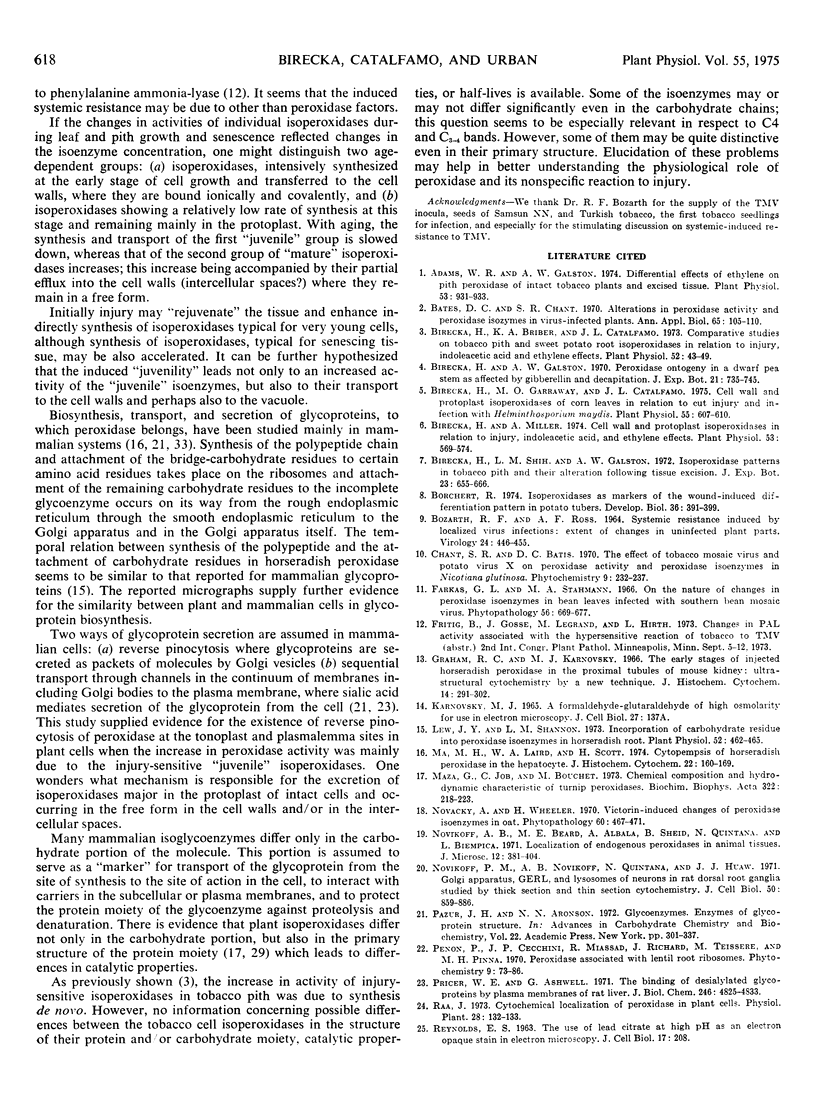

Leaves and pith of Turkish, Wisconsin 38, and Samsun NN tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) varieties, which differ in their sensitivity to tobacco mosaic virus, showed the same qualitative isoperoxidase patterns and a similar distribution of distinctive isoperoxidases between the cell protoplast and wall-free, ionically, and covalently bound fractions. No changes in the qualitative isoenzyme spectrum were found in relation to age, mechanical injury, or leaf infection with tobacco mosaic virus. The distinctive isoperoxidases which reacted to infection were the same as those responsive to mechanical injury, confirming that the enzyme reaction to infection results from a nonspecific response to injury. The increase in peroxidase activity in response to infection or mechanical injury, or both, was greater in young tissue than in the older ones. The great increase in Samsun NN leaves and no increase in those of the two other varieties in response to infection may be due to differences in the degree to which the pathogen affected processes controlling the nonspecific peroxidase reaction to injury. Peroxidase development in the infected Samsun NN leaves was due to isoenzymes which form the wall-bound fraction in very young tissues, and to those which increase in activity with aging in the protoplast and wall-free fractions. In mechanically injured tissue, only the first group of isoenzymes increased in activity. In Samsun NN plants, the increased peroxidase activity in upper intact leaves above the infected ones was only due to isoenzymes whose activity increases with both normal and virus-accelerated senescence. Peroxidase reaction to challenge inoculation in these leaves was the same whether the lower ones were intact, infected and/or mechanically injured. Thus, the induced systemic resistance to tobacco mosaic virus may be due to other than peroxidase factors.

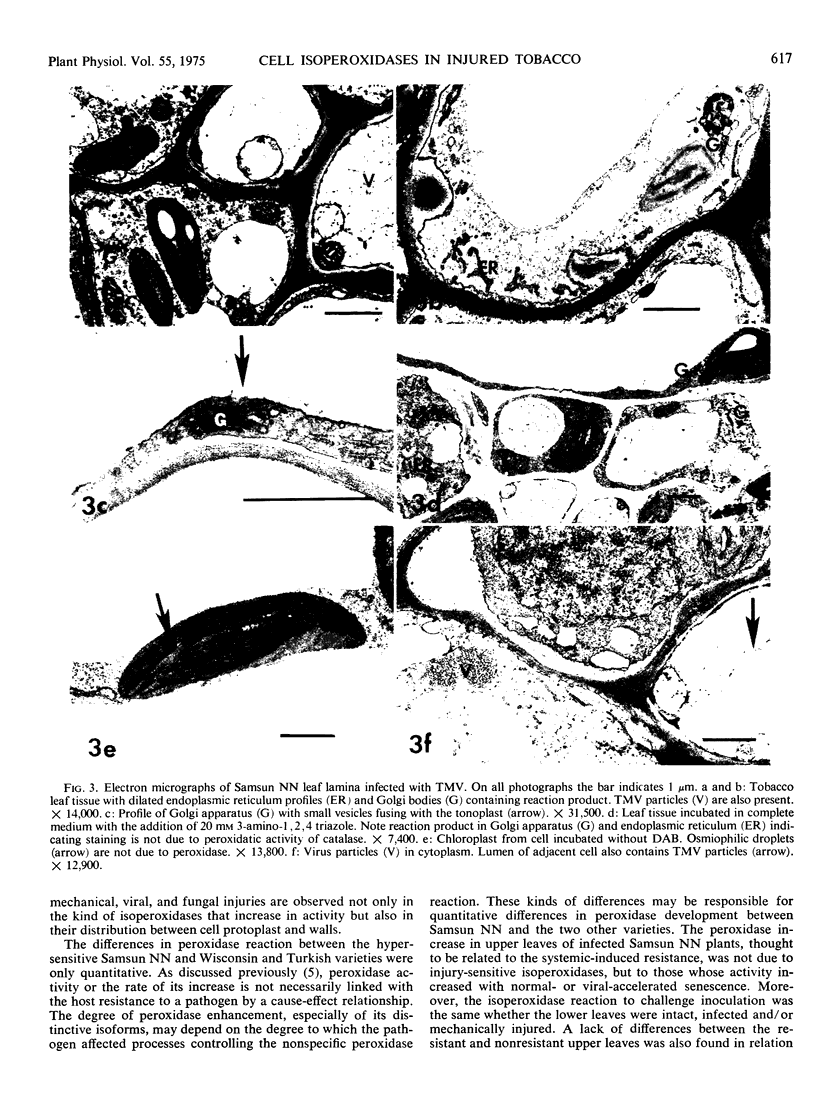

In infected tissues, peroxidase was detected in the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, vacuole, cell wall, and intercellular spaces. The Golgi vesicles were often localized near the tonoplast and plasmalemma, fusing with membranes and secreting their contents. The possible “rejuvenating” effects of injury on synthesis and transport of distinctive isoperoxidases are discussed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams W. R., Galston A. W. Differential effects of ethylene on pith peroxidase of intact tobacco plants and excised tissue. Plant Physiol. 1974 Jun;53(6):931–933. doi: 10.1104/pp.53.6.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birecka H., Briber K. A., Catalfamo J. L. Comparative studies on tobacco pith and sweet potato root isoperoxidases in relation to injury, indoleacetic Acid, and ethylene effects. Plant Physiol. 1973 Jul;52(1):43–49. doi: 10.1104/pp.52.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birecka H., Catalfamo J. L. Cell Wall and Protoplast Isoperoxidases of Corn Leaves in Relation to Cut Injury and Infection with Helminthosporium maydis. Plant Physiol. 1975 Apr;55(4):607–610. doi: 10.1104/pp.55.4.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birecka H., Miller A. Cell wall and protoplast isoperoxidases in relation to injury, indoleacetic Acid, and ethylene effects. Plant Physiol. 1974 Apr;53(4):569–574. doi: 10.1104/pp.53.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchert R. Isoperoxidases as markers of the wound-induced differentiation pattern in potato tuber. Dev Biol. 1974 Feb;36(2):391–399. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(74)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas G. L., Stahmann M. A. On the nature of changes in peroxidase isoenzymes in bean leaves infected by southern bean mosaic virus. Phytopathology. 1966 Jun;56(6):669–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham R. C., Jr, Karnovsky M. J. The early stages of absorption of injected horseradish peroxidase in the proximal tubules of mouse kidney: ultrastructural cytochemistry by a new technique. J Histochem Cytochem. 1966 Apr;14(4):291–302. doi: 10.1177/14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M. H., Laird W. A., Scott H. Cytopempsis of horseradish peroxidase in the hepatocyte. J Histochem Cytochem. 1974 Mar;22(3):160–169. doi: 10.1177/22.3.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza G., Job C., Bouchet M. Chemical composition and hydrodynamic characteristics of turnip peroxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973 Oct 18;322(2):218–223. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(73)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikoff P. M., Novikoff A. B., Quintana N., Hauw J. J. Golgi apparatus, GERL, and lysosomes of neurons in rat dorsal root ganglia, studied by thick section and thin section cytochemistry. J Cell Biol. 1971 Sep;50(3):859–886. doi: 10.1083/jcb.50.3.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pricer W. E., Jr, Ashwell G. The binding of desialylated glycoproteins by plasma membranes of rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1971 Aug 10;246(15):4825–4833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REYNOLDS E. S. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1963 Apr;17:208–212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seevers P. M., Daly J. M., Catedral F. F. The role of peroxidase isozymes in resistance to wheat stem rust disease. Plant Physiol. 1971 Sep;48(3):353–360. doi: 10.1104/pp.48.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman A. M., Shannon W. A., Jr, Hoshino Y., Plapinger R. E. Some important principles in 3,3'-diaminobenzidine ultrastructural cytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1973 Aug;21(8):756–758. doi: 10.1177/21.8.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner R. R., Cynkin M. A. Glycoprotein biosynthesis. Incorporation of glycosyl groups into endogenous acceptors in a Golgi apparatus-rich fraction of liver. J Biol Chem. 1971 Jan 10;246(1):143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]