Abstract

Toxin–antitoxin (TA) modules are small operons involved in bacterial stress response and persistence. higBA operons form a family of TA modules with an inverted gene organization and a toxin belonging to the RelE/ParE superfamily. Here, we present the crystal structures of chromosomally encoded Vibrio cholerae antitoxin (VcHigA2), toxin (VcHigB2) and their complex, which show significant differences in structure and mechanisms of function compared to the higBA module from plasmid Rts1, the defining member of the family. The VcHigB2 is more closely related to Escherichia coli RelE both in terms of overall structure and the organization of its active site. VcHigB2 is neutralized by VcHigA2, a modular protein with an N-terminal intrinsically disordered toxin-neutralizing segment followed by a C-terminal helix-turn-helix dimerization and DNA binding domain. VcHigA2 binds VcHigB2 with picomolar affinity, which is mainly a consequence of entropically favorable de-solvation of a large hydrophobic binding interface and enthalpically favorable folding of the N-terminal domain into an α-helix followed by a β-strand. This interaction displaces helix α3 of VcHigB2 and at the same time induces a one-residue shift in the register of β-strand β3, thereby flipping the catalytically important Arg64 out of the active site.

INTRODUCTION

Toxin–antitoxin (TA) modules are small autoregulated operons found in bacteria and archaea (1,2). They are involved in several physiological functions, most notably in plasmid stabilization (3), in bacterial stress-response (4,5) and in the transition to the persister state (6). Most abundant are type II modules, which consist of two genes: one encoding for a toxin protein and the other for a corresponding antitoxin protein. The toxins shutdown bacterial metabolism by interfering with the components of the translation machinery or with the DNA replication and transcription systems (reviewed in 4,6). In normal growing cells, the activity of the toxin is controlled by tight binding of the antitoxin. Activation of the toxins depends on the degradation of the antitoxin by intracellular proteases such as Lon and is triggered by various stress stimuli, such as nutrient deprivation and antibiotic treatment or in the case of plasmid-residing TA modules plasmid loss (7).

Most prevalent among TA toxins are ribonucleases. MazF and HicA toxins mostly cleave free mRNA (8,9) while ribonucleases from the RelE superfamily cleave mRNAs in a ribosome-dependent context (10). tRNAs are also the target of several different types of toxins (11). The RelE superfamily can be divided into several subfamilies based on sequence identities of the toxins. Different members of the RelE family have historically been given different names such as HigB, MqsR, BrnT, YafQ and YoeB, but the nomenclature does not always coincides well with sequence relationships between the toxins. The structures of different members of the RelE family are known in their free, ribosome-bound and antitoxin-bound states. Despite differences in active site residues, all of them bind to the A site of the translating ribosome (12–14). Some toxins are inhibited by the antitoxin that covers the active site (15,16) yet notable exceptions include MqsA, PvHigB and YafQ, where the antitoxin does not interact with the active site (17–20).

The higBA module was first discovered on plasmid Rts1 from Proteus vulgaris (21). It has an unusual, inverted toxin-before-antitoxin gene organization that was later also observed in some other TA modules such as mqsRA, hicAB and brnTA (9,22,23). The crystal structure of the Rts1 plasmid-born higBA from P. vulgaris (from now on referred to as PvhigBA) shows a toxin with a RelE-type ribonuclease fold and an unusual antitoxin that is fully structured, with a single domain harboring both the toxin neutralizing and DNA binding activities (13,17).

Chromosomal counterparts of the higBA module were identified on the Vibrio cholerae chromosome II, which hosts two such modules higBA1 and higBA2. The activation of these two orthologs depends on the Lon protease and is triggered by amino acid starvation (24,25). The V. cholerae HigB2 toxin (VcHigB2) is a ribosome-dependent RNase that cleaves translating mRNA molecules with a similar cleavage pattern as Escherichia coli RelE (24,26). These genes were initially annotated as higBA homologs given their reverse gene organization. However, sequence alignments indicate that the active site residues are more similar to RelE and considering these higBA homologs display a similar cleavage pattern as RelE, it is assumed they function as RelE homologs.

In this work, we present the crystal structures of the VcHigBA2 complex and its components VcHigB2 and VcHigA2 together with thermodynamics of their mutual interactions and the structure-activity relationship of the toxin's active site. Our results show that there are important differences between Vibrio and Proteus encoded higBA modules concerning the structures of toxin and antitoxin as well as the neutralization mechanism. The structures of free and antitoxin-bound VcHigB2 toxin are related by a shift in the register of a β-strand, resulting in two conformations of the catalytically important Arg64. We discuss this β-strand sliding, which is observed for the first time for a ribonuclease protein, in the context of toxin neutralization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of VcHigBA2, VcHigB2, VcHigA2 and VcHigA2ΔN

Peptides (VcHigA23-22 and VcHigA23-33) were obtained from China Peptides Co., Ltd. and were at least 95% pure according to the manufacturer. Both peptides contain an additional tryptophan residue at their C-terminus to enable concentration determination by UV spectrophotometry. Cloning of the V. cholerae higBA2 operon and purification of the VcHigBA2 complex as well as of the individual VcHigA2 and VcHigB2 proteins have been described previously (27,28). A sequence corresponding to the truncated version of VcHigA2 containing C-terminal domain only (residues 37–104) was cloned by a commercial supplier (GenScript) into the pET21b+ vector (Novagen) using its NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. In this construct an un-cleavable Histidine tag is placed at the C-terminus of VcHigA2ΔN and protein was produced following the same protocol as for the production of VcHigBA2 (27,28).

Selenomethionine-labeled VcHigBA2 complex was produced using auxotrophic E. coli B834 (DE3) cells. A preculture was grown at 37°C in SelenoMet medium (Molecular Dimensions Limited) supplemented with ampicillin (100 mg l−1), L-methionine (50 mg l−1) and 0.2% glucose. After overnight incubation the cells were pelleted, washed with sterile water and used to inoculate the main culture in the same medium as before but with L-Se-methionine (50 mg l−1) added. Cells grown for 10 h at 37°C (OD600 nm∼1) were induced with 1 mM IPTG and incubated overnight. From this point on the complex was purified according to the same protocol as the unlabeled complex (27).

The concentrations of the proteins and peptides were determined by measuring UV absorption using extinction coefficients for proteins calculated according to Pace et al. (29). The following molar extinction coefficients at 280 nm were used (in M−1 cm−1): 42860 (VcHigBA2 complex, 2:2 stoichiometry), 15930 (VcHigB2), 11000 (full-length and truncated VcHigA2 dimer), 5500 (VcHigA23-22 and VcHigA23-33).

Nanobody production

Nanobodies were raised against VcHigB2 via the VIB Nanobody Service Facility (http://www.vib.be/en/research/services/Nanobody-Service-Facility). The nanobody gene sequences were re-cloned into to the pHEN6c expression vector, which was subsequently transformed into E. coli WC6 cells. Cell cultures were grown in TB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 mg l−1) at 37°C with aeration. The cultures were grown until OD600 nm reached 0.8, after which the temperature was lowered to 28°C. Expression was induced by adding 1 mM IPTG and the cultures were incubated overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 0.2 M TRIS–HCl, 0.5 M sucrose, 0.65 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), PH 8.0. The nanobodies were extracted from the periplasm by osmotic shock by resuspending cells followed by 45 min incubation at 4°C with stirring at 200 rpm. The lysate was centrifuged (40 min at 25 000 g) to remove the cell debris and loaded onto a Ni-NTA column equilibrated in 50 mM phosphate pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl buffer. The column was washed with five column volumes of 50 mM phosphate pH 6.0, 1 M NaCl buffer to elute the non-specifically bound proteins. The nanobodies were eluted with 50 mM phosphate pH 4.5, 1 M NaCl. The nanobody-containing fractions were pooled and neutralized by the addition of 1 M TRIS–HCl pH 7.4. The pooled fractions were further purified on a Superdex 75 HR 10/30 gel-filtration column run with 20 mM TRIS-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl elution buffer. The purity of the nanobody samples was analysed by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

In vitro activity assay

The activity of VcHigB2 and its neutralization by VcHigA2 and the VcHigA2-derived peptides was analyzed by measuring the synthesis of the reporter protein eGFP using the in vitro synthesis kit (PURExpress, New England Biolabs). The reactions (12.5 μl) were set up according to the manufacturers’ instructions and supplemented with 75 ng of purified PCF fragment (purified using Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System, Promega) coding for the eGFP reporter protein (amplified from pPROBE'-GFP plasmid with primers 5΄: GCGAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCT–TAAGTATAAGGAGGAAAAAATATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTCAC and 3΄: AAACCCCTCCGT–TTAGAGAGGGGTTATGCTAGTTATTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCATTTGTATAGTTCATC–CATGCCA. Reactions were incubated for 3 h at 37°C in absence and presence of varying amounts of VcHigB2 and its variants, VcHigA2, VcHigA23-22 and VcHigA23-33. Relative amount of synthesized protein was determined through fluorescence measurement by diluting the sample to 60 μl and using 483 and 535 nm as excitation and emission wavelengths. Concentration of WT toxin or toxin variant required for half-maximal inhibition of reporter protein synthesis was obtained by fitting the inhibition curve, which was the average of three experiments, to the logistic function (Supplementary Figure S4).

In vitro ribosome binding assay

Ribosomes from E. coli MRE600 strain were purified on 10–50% sucrose gradient in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NH4Cl as previously described (30). Ribosomes were collected top to bottom and the profiles were measured based on absorption at 280 nm. Ribosomal fractions were pooled and sucrose was removed using buffer exchange by Amicon 100K filters (Millipore). We used T7 polymerase to synthesize mRNA (5΄-GGGCAAAACAAAAGGAGGCTAAATATGTTCTAGCAAAACAAAACAAAA-GAATT-3΄) and tRNAs were extracted from E. coli XL1-Blue cells as previously described (31). The ribosome binding assays were performed in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 70 mM NH4Cl, 30 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT. Ribosomes were used at a final concentration of 2 μM and were incubated with 2-fold excess of mRNA for 5 min at 37°C and 4-fold excess of tRNA for 30 min prior to the assays. VcHigB2 toxin was added in 5-fold excess and incubated for 20 min. All the reactions were layered on the sucrose gradient and free VcHigB2 toxin was also layered on the sucrose gradient as control. Fractions corresponding to proteins and to ribosomal fractions were pooled and TCA precipitated, pellets were washed two times with acetone, air dried and re-suspended in SDS-loading buffer. Protein and ribosomal fractions were then analysed by SDS-PAGE and western blot with antibodies against polyHis tag.

Crystallography

Crystallization and data collection for VcHigBA2, VcHigA2 and VcHigB2 have been described (27). Complexes of VcHigB2 with nanobodies Nb2, Nb6 and Nb8 were prepared by mixing 1 mg of toxin with 1.3 mg of nanobody and isolating the pure complex by size-exclusion chromatography using the BioRad Enrich 70-10-30 column. Isolated complexes were crystallized using the hanging drop method. Drops consisting of 1 μl of protein solution (10 mg ml−1 in 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM TRIS–HCl pH 8.0) and 1 μl of precipitant solution were equilibrated against 110 μl precipitant solution. Various commercial screens were used: Crystal Screen and Crystal Screen 2 (Hampton Research), Morpheus, PACT premier and ProPlex (Molecular Dimensions) and Jena Classic (Jena Bioscience). All final crystallization conditions are listed in Table S1.

All data were measured at the SOLEIL synchrotron (Gif-sur-Yvette, France) at 100K on beamline PROXIMA1 using a PILATUS 6M detector. All data were indexed, integrated and scaled with XDS (32). The structure of the VcHigBA2 complex was determined using SAD phasing. Se-Met sites were located using SHELXD using the selenium anomalous signal (33) and phases were calculated using PHASER-EP (34). Following density improvement with PARROT (35), an initial model was automatically build with BUCCANEER (36). The latter was used as a starting point for iterative refinement with phenix.refine (37) and manual rebuilding using Coot (38).

All other structures were solved by molecular replacement using PHASER-MR (34) and using the C-terminal domain of the VcHigA2 antitoxin or the VcHigB2 toxin as present in the VcHigBA2 complex as search models. To locate nanobodies, the co-ordinates of a nanobody against β-lactamase BcII and stripped of its complementarity-determining region (CDR) loops (39), (PDB ID: 3DWT) was used as search model. In all cases, the structures were manually rebuilt using Coot and refined using phenix.refine. The final refinement cycles included TLS refinement (one TLS group per chain). Data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table S1.

Small angle X-ray scattering

SAXS data were collected at 15°C in HPLC mode at the SWING beamline at the SOLEIL synchrotron (Gif-sur-Yvette, France). The VcHigA2 sample (8 mg/ml in 20 mM TRIS–HCl pH 8.0 and 200 mM NaCl) was injected into a Shodex KW 402.5-4F column and ran at 0.2 ml/min. The data frames (1 ms exposure) were interrupted by a dead time of 0.5 ms. The buffer scatter was measured at the beginning of the chromatogram (during the dead volume), while the sample scatter was collected during the peak elution, which enables the acquisition of data at different protein concentrations. The data were processed with Foxtrot (40) and the ATSAS package (41). After buffer subtraction, Guinier analysis was performed on each curve using the program AUTORG (41). The curves of sufficient quality and stable Rg value along the elution peak were merged into a single final scatter curve used in further analysis. The molecular weights of the proteins and the protein complexes was estimated by using the QR ratio derived from the invariant volume of correlation (42).

A model of the VcHigA2 conformational ensemble was generated using the Ensemble Optimization Method (EOM) (43). An initial pool of 10 000 random conformations was generated for the disordered N-terminal segment (residues 2–37) attached to the folded C-terminal domain based on the following assumptions: (i) the Cα distribution of the disordered segment is one found in random-coils, (ii) the symmetry of the folded core dimer is C2 (iii) no overall structure symmetry is imposed. A final ensemble was selected from the pool of conformations with the EOM algorithm based on the experimental scattering curve and this process was repeated five times. These final ensembles had χ2 values of 5.9, 1.1, 1.2, 1.2, 1.2 and consisted of 5–7 models. Based on the RG and DMAX values of the individual models all ensembles (except the first one) are structurally similar. The model ensemble with the lowest χ2 value (1.1) is considered to best represent the true ensemble and structural parameters of each model in this model ensemble are given in Supplementary Table S4. The quality of the model ensemble was assessed using the RSAS and χ2FREE parameters as proposed recently (42) and is reported in Supplementary Table S3.

CD spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements were carried out at 25°C on an Aviv 62A DS CD spectrophotometer (Aviv Associates, NJ, USA) in a cuvette with 1 mm optical path length. All data were measured in 20 mM phosphate pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl buffer in the wavelength range of 190–250 nm using a spectral bandwidth of 0.5 nm and an averaging time of 2 s. For measurements of the induction of secondary structure in the antitoxin VcHigA2 upon VcHigB2 binding, spectra of free VcHigB2 (14 μM), free VcHigA2 (6 μM) and of the VcHigBA2 TA complex (14 μM toxin mixed with 6 μM antitoxin dimer) were measured. The spectrum of VcHigA2 in its bound conformation was estimated as difference spectrum between the spectrum of the VcHigBA2 complex and the spectrum of free VcHigB2 toxin. To estimate the CD spectrum of the antitoxin N-terminal domain of VcHigA2 in its native unbound state, the spectrum of the truncated antitoxin variant consisting of the C-terminal domain only (VcHigA2ΔN) was subtracted from the spectrum of the full-length antitoxin (both protein were at 20 μM concentration). The CD spectrum of the VcHigA23-33 peptide derived from the VcHigA2 N-terminal domain was measured at 12 μM. The reported mean molar ellipticities (in degrees cm2 dmol−1) were obtained from the raw data (ellipticities) by taking into account the molar concentration (c) and the optical path length (l) through the relation [θ] = θ /(c l).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Samples were dialyzed against 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA and filtered. Prior to the experiments the samples were degassed for 20 min. All experiments were performed in a VP-ITC micro-calorimeter (MicroCal, CT, USA). The concentration of VcHigB2 in the cell was 1 μM and the concentration of the macromolecule in the syringe (VcHigA2 or VcHigA23-22) depended on the desired final stoichiometry. Raw data were integrated using the MicroCal Origin software to obtain the enthalpy change (per mole of ligand added per injection) as a function toxin/antitoxin ratio r at temperature T. The enthalpy changes accompanying complex formation were obtained by correcting the measured enthalpies for the dilution effects (in case of strong binding, the dilution enthalpy was estimated using the measured enthalpy changes above stoichiometric ratios).

Calorimetric curves were measured at four different temperatures (15, 25, 37, 42°C) that are below the temperatures that induce unfolding of the protein samples. For the analysis of the titration curves (enthalpy change ΔH(T,r) measured at different molar ratios r), a model function was derived based on binding models assuming two equivalent independent binding sites on the VcHigA2 or one binding site on the VcHigA2 peptides:

|

(1) |

The derivative  (

( is the average number of occupied binding sites), which contains information on the site binding constant K was derived from the corresponding mass-balance equations and expressed in an analytical form. The model function is defined at any r and T by the enthalpy ΔHb°(T0) and free energy ΔGb°(T0) ( = -RT0·lnK(T0)) of binding (T0 = reference temperature = 25°C) and heat capacity of binding Δc°p,b (assumed to be temperature-independent quantity) (30). Values of parameters ΔHb°(T0), ΔGb°(T0) and Δc°p,b were determined using the global fitting approach based on Levenberg–Marquardt least-square minimization of the discrepancy between the model function and experimental titration curves measured at different T. Validity of the fitted parameters was assessed using a Monte-Carlo error propagation analysis (Supplementary Figure S6).

is the average number of occupied binding sites), which contains information on the site binding constant K was derived from the corresponding mass-balance equations and expressed in an analytical form. The model function is defined at any r and T by the enthalpy ΔHb°(T0) and free energy ΔGb°(T0) ( = -RT0·lnK(T0)) of binding (T0 = reference temperature = 25°C) and heat capacity of binding Δc°p,b (assumed to be temperature-independent quantity) (30). Values of parameters ΔHb°(T0), ΔGb°(T0) and Δc°p,b were determined using the global fitting approach based on Levenberg–Marquardt least-square minimization of the discrepancy between the model function and experimental titration curves measured at different T. Validity of the fitted parameters was assessed using a Monte-Carlo error propagation analysis (Supplementary Figure S6).

Structure-based thermodynamic calculations

Polar (AP) and nonpolar (AN) contributions of the solvent accessible surface were calculated using NACESS 2.1 with the default set of parameters (44). Change of the solvent accessible surface due to the formation of the VcHigBA2 was calculated by subtracting total surface of the proteins in the unbound state from that of the VcHigBA2 complex. The heat capacity change was estimated by the relation introduced by Murphy and Freire (45).

RESULTS

Crystal structure of VcHigB2

As VcHigB2 resisted crystallization by conventional methods we used VcHigB2-specific cameloid single-chain antibody fragments as crystallization chaperones. From the blood of a single llama immunized with VcHigB2, a library was constructed that was panned for VcHigB2 binders using phage display. From this library, 10 unique nanobody sequences were obtained, of which five were used to produce protein (selection was based on good expression yields). From these five nanobodies, three (Nb2, Nb6 and Nb8) eventually gave crystals of sufficient quality for structure determination. In these three complexes nanobodies are bound to different VcHigB2 epitopes and the resulting structures of the VcHigB2 are very similar—with 0.7 Å (VcHigB2-Nb6 versus Nb8) and 1.4 Å (VcHigB2 Nb2 versus Nb6) rmsd for 94 out of 110 Cα atoms (Supplementary Figure S1). This suggest that nanobody binding does not significantly disturb the fold of the protein, and that the conformation of VcHigB2 observed in these crystals may be a good approximation to that of the toxin in the unbound state.

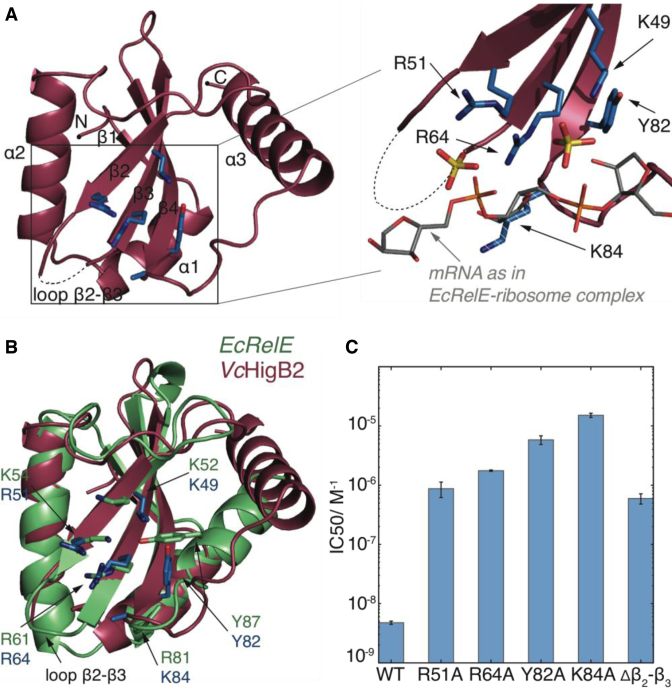

The VcHigB2 toxin consists of a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet core flanked by two N-terminal α-helices (helices α1 and α2) on one side and a longer C-terminal α-helix (helix α3) on the other side (Figure 1A). This architecture is typical for a large family of microbial RNases that includes other TA related mRNA interferases such as RelE, MqsR, YoeB and YafQ (15,18–20,46). Electron density is seen for the entire molecule except for the affinity tag and residues Ala53-Ser63 of loop β2-β3, which has a disorder-promoting sequence ASKGKGRGGS (dashed line in Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

The structure and activity of VcHigB2 toxin. (A) Left: the structure of the VcHigB2 toxin. Secondary structure elements and positively charged β2-β3 loop, which is missing from the model are indicated. Active site residues are shown as blue sticks. Right: detailed view of the active site residues, which coordinate two sulphate ions from the crystallization mixture (yellow). The mRNA (gray) as found in the EcRelE-ribosome structure (PDB ID: 4V7J) is superimposed for comparison. The side chain of Lys84 lacks clear electron density, but is modeled here in a likely position and shown as dashed stick. (B) Comparison of the active site of the VcHigB2 (red) and the EcRelE (green, PDB ID: 3KHA). VcHigB2 residues (blue sticks) that correspond to the active site residues of EcRelE (green sticks) are shown. (C) Concentrations of WT toxin and its variants to achieve half-maximal inhibition of the reporter protein synthesis in the in vitro activity assay.

A DALI search identified E. coli RelE (EcRelE, PDB 3KHA, DALI score 9.6, (47)) as the closest structural relative of VcHigB2. Although VcHigB2 and EcRelE share only 17% sequence identity, their tertiary structures are well preserved (2.5 Å rmsd for 82 of 94 Cα atoms). Notable differences are observed for the packing of the C-terminal helix against the β-sheet core and for loop β2-β3, which is structured and significantly shorter in EcRelE (Figure 1B). Apart from EcRelE, VcHigB2 shares high structural similarity with RelJ, YoeB, YafQ, the archeal RelEs (which are all ribonucleases,(15,19,46) and also with Caulobacter crescentus ParE and E. coli O157 ParE2 (48,49), which have different biochemical activities (Supplementary Figure S2, sequence identities and DALI scores are given in Supplementary Table S2). Surprisingly, plasmid-born PvHigB, together with BrnT from Brucella abortus and MqsR from E. coli belongs to the more distant relatives (Supplementary Figure S2 and Table S2, (17,18)). While the β-sheet core is still preserved, these toxins completely lack the C-terminal helix α3 and also differ in the arrangement and number of N-terminal helices.

VcHigB2 has a RelE-like active site

Similar to EcRelE (24,26), the ribosome bound VcHigB2 toxin cleaves translating mRNA molecules after the second codon position without a strong sequence preference. The active site of VcHigB2 is located on the β-sheet surface and is almost identical to the active site of EcRelE (Figure 1B). The active site surface is positively charged, suggesting strong electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged mRNA phosphate backbone. Two sulphate ions are located in the active site of VcHigB2, strongly resembling the positions of backbone phosphates of the mRNA molecule in the RelE-ribosome structure (Figure 1A, (12)). It is not uncommon for ribonucleases to harbor a sulphate or phosphate ion in their active site cleft in absence of a substrate, and has been observed for other RelE family members such as YafQ (20).

Based on the sequence alignment and structural similarity with EcRelE (sequence alignment is shown in Supplementary Figure S3) we prepared several variants of VcHigB2 with alanine substitutions of the presumed active site residues (Arg51, Arg64, Tyr82 and Lys84). For all of these toxin variants orders of magnitude higher concentrations are needed to inhibit synthesis of a reporter protein in our in vitro translation assay compared to the WT toxin (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure S4). Most disruptive is the substitution of Lys84 leading to a 3000-fold drop in toxin activity, followed by Tyr82 with a 1200-fold reduction (Figure 1C). Substitutions of Arg51 and Arg64 on strands β2 and β3, which coordinate a sulphate ion in our structure, were less disruptive (170- and 350-fold reduction relative to WT). Similar to EcRelE, the active site of VcHigB2 toxin lacks a His-Glu or His-His acid-base pair as is commonly found in RNases and other members of the RelE superfamily. Recent data on the cleavage mechanism of EcRelE points toward a model where the acid-base pair consists of an arginine (Arg81) and a lysine (Lys54) residue (50,51). Interestingly, in VcHigB2 this arginine is structurally replaced by Lys84 while the lysine is replaced by Arg51. We also tested a toxin variant where the positively charged flexible β2-β3 loop (residues 54–63) is substituted by a sequence of three alanines. This modification reduces the activity by 120-fold relative to the WT enzyme (Figure 1C).

VcHigA2 contains of a helix-turn-helix DNA binding/dimerization motif

The VcHigA2 antitoxin counteracts the VcHigB2 toxin and rescues growth-stalled bacterial cells (24). The molecular weight estimate for VcHigA2 from SAXS is in accordance with previous estimates from analytical gel-filtration experiments, which indicates that this antitoxin is a dimer (Supplementary Table S3, (28)). Crystals of the C-terminal domain of VcHigA2 (residues 38–104) were obtained after a 4-month waiting period from trials utilizing the full length protein (27). These crystals contain in their asymmetric unit four dimers of the C-terminal domain arranged around a non-crystallographic four-fold axis while the N-terminal domain is absent due to degradation as shown before (27).

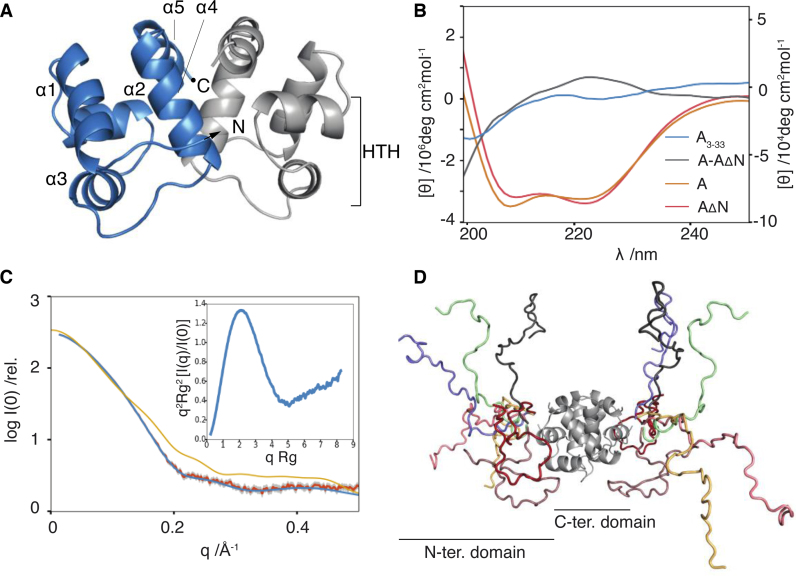

The VcHigA2 C-terminal domain is a Lambda repressor-like DNA binding domain. The domain has a small hydrophobic core surrounded by five α-helices (Figure 2A). The dimerization interface is formed by helices α4 and α5, while helices α2 and α3 form a characteristic HTH motif that likely binds the operator DNA. This arrangement differs dramatically from the PvHigA where the dimerization interface is formed by a longer helix α5. This results in an overall distinct relative orientation of the two monomers in the dimer, and thus a different relative disposition of the two DNA binding motifs (Supplementary Figure S5, (17)). Taken together the DNA-binding domain of the VcHigA is more similar to the MqsA antitoxin (PDB ID: 3GN5, (18)), while that of PvHigA antitoxin seems to belong to a distinct group of HTH proteins that also includes HigA from E. Coli (PDB 2ICT) and Coxiella brunetii (PDB ID: 3TRB).

Figure 2.

VcHigA2 antitoxin has two domains. (A) Crystal structure of the VcHigA2 C-terminal DNA-binding domain. Two monomers are in different colors. Helix-turn-helix motif is indicated on one monomer. (B) CD spectra of the full-length VcHigA2 (orange) and the N-terminal truncate VcHigA2ΔN (red) have very similar intensities indicating that the N-terminus is unstructured. The difference spectrum (VcHigA2-VcHigA2ΔN) corresponding to the N-terminal domain in the full-length antitoxin (gray) has features typical of random coil and is very similar to the that of the N-terminal peptide VcHigA23-33 (blue). Intensities for blue and gray spectra are given on the right y-axis. (C) The measured SAXS curve of the full-length antitoxin (orange) is superimposed on the calculated scatter of the EOM-derived model (blue). The extended, folded conformation of the VcHigA2 as observed in the VcHigBA2 complex is not compatible with the SAXS data (yellow). Inset: the normalized Kratky plot is in agreement with the presence of a globular domain combined with a flexible segment. (D) The representative EOM-derived model of the full-length antitoxin consists of seven conformations of the N-terminal domain (in different colors).

The N-terminal region of VcHigA2 is intrinsically disordered

Several lines of evidence suggest that the VcHigA2 N-terminal region (residues 1–36), which was not observed in the crystal structure of the free antitoxin, is intrinsically disordered in solution. The CD spectrum of a peptide encompassing residues Asn3 to Asn33 is typical for a random coil polypeptide with a minimum below 200 nm and a very weak ellipticity above 210 nm (blue curve, Figure 2B). The CD spectrum of the N-terminal region in its native state (attached to the C-terminal domain) was estimated by calculating the difference spectrum between full length VcHigA2 and a truncate (VcHigA2ΔN) consisting of amino acid residues 37–104. The latter protein, which mirrors the residues seen in the crystal structure, is thermodynamically stable and shows a CD spectrum with essentially the same α-helical content as the full length protein (Figure 2B). The difference spectrum is similar to the spectrum of the isolated peptide and suggests presence of the random coil structure (gray and blue curves, Figure 2B).

Further evidence for an N-terminal intrinsically disordered domain comes from SAXS experiments. The normalized Kratky plot of VcHigA2 shows a bell-shaped curve (typical for a globular macromolecule), followed by a continuous increase of the intensity at higher scattering angles (a sign of flexibility) (Figure 2C, inset). Such a shape is characteristic for a protein consisting of a globular domain connected to an IDP domain (52). Together with the CD data, this thus agrees with a model in which the VcHigA2 antitoxin has a well-structured dimeric C-terminal domain, as seen in the crystal structure, and ∼36 amino acids long disordered N-terminal segment.

Based on these assumptions we applied the Ensemble Optimization Method (43) to derive a model for the structural ensemble of the full-length antitoxin. The minimal ensemble model that satisfactorily describes the data includes seven conformations (Figure 2C and D, model statistics are given in Supplementary Table S3). Interestingly, these conformations belong to two structural groups. One contains extended conformations of the N-terminal domain, while the other is characterized by more compact conformations. The structural parameters for all conformations of the representative ensemble are given in Supplementary Table S4.

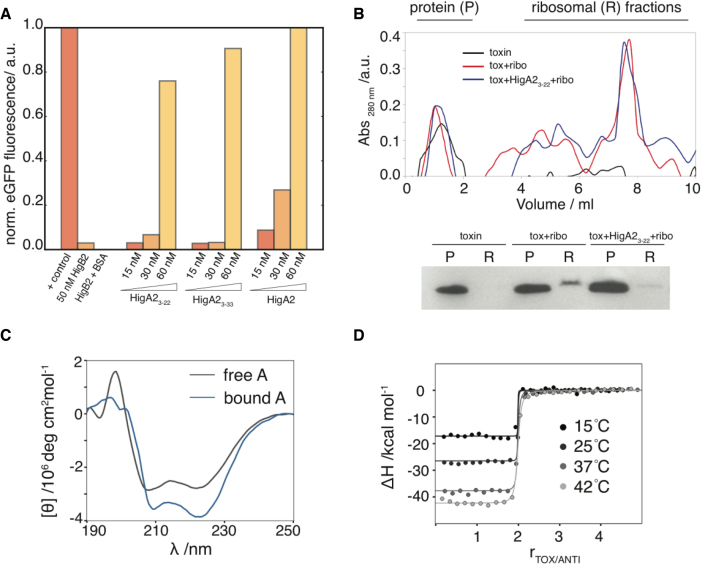

The N-terminal domain of VcHigA2 inhibits VcHigB2 through folding upon binding

Increasing amounts of VcHigB2 abolish synthesis of the reporter protein in an in vitro translation assay and half-maximal inhibition is observed at 5 nM concentration of VcHigB2 toxin (Supplementary Figure S4, (28)). Addition of VcHigA2 in stoichiometric amounts inactivates VcHigB2 (Figure 3A). Interestingly, peptides derived from the VcHigA2 N-terminus also counteract the activity of the toxin (Figure 3A). The minimal element for toxin inhibition is the VcHigA2 peptide encompassing residues Asn3-Glu22, which corresponds to the segment that folds into an α-helix upon toxin binding (see below). Using an in vitro ribosome binding assay we also observe that the VcHigA23-22 peptide prevents VcHigB2 binding to the ribosomes (Figure 3B). Thus the intrinsically disordered N-terminal domain is sufficient for VcHigB2 toxin regulation.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of the VcHigB2 toxin by the VcHigA2 antitoxin. (A) Fluorescent reporter protein is synthesized in the in vitro translation assay and addition of VcHigB2 toxin (at 50 nM, 10 times above its IC50) inhibits its synthesis. Addition of BSA (at 1 μM) has no effect on toxin activity, while peptides derived from the N-terminus of VcHigA2 antitoxin (VcHigA23-22 and VcHigA23-33) as well as full-length antitoxin inhibit toxin activity. Concentration of VcHigB2 toxin was constant 50 nM. Fluorescence of the reporter protein (eGFP) was normalized using the values for the positive (no toxin) and negative controls (no eGFP coding fragment). (B) Top: ribosome profiles from ultracentrifugation on a sucrose gradient. Bottom: anti-his western blot of the protein and ribosomal fractions show that VcHigA23-22 prevents binding of the VcHigB2 toxin to the ribosome. (C) Binding to the toxin is coupled by the folding of the antitoxin. CD spectrum of the bound antitoxin estimated as the difference spectrum between VcHigBA2 complex and VcHigB2. (D) Calorimetric titrations of toxin into antitoxin performed at different temperatures. Global fits of the model function (Equation 1) to the data measured at different temperatures are shown as solid lines.

The interaction between VcHigA2 and VcHigB2 is characterized by a very high affinity and by structuring of the antitoxin N-terminal domain. Coupled folding and binding is evident from the comparison of the CD spectra from free and the VcHigB2-bound VcHigA2 (Figure 3C). The interaction was studied using ITC and the corresponding thermodynamic parameters were obtained by global fitting of the model function (Equation 1) to the titration curves measured at four different temperatures (see Methods). This procedure ensures that the parameters ΔGb°, ΔHb°, TΔSb° and Δc°p,b are reliable within the error margins as determined from the Monte Carlo error propagation analysis (Figure 3D and Supplementary Figure S6). The dissociation constant of the VcHigB2–VcHigA2 complex is 50 pM (at 25°C; ΔGb° = −14.1 ± 0.5 kcal mol−1). Binding is driven by a high negative enthalpy change (ΔHb° = −26.6 ± 0.9 kcal mol−1) and is opposed by an unfavorable entropy contribution (TΔSb° = −12.5 ± 1.0 kcal mol−1). Similar thermodynamic characteristics were observed also for high-affinity binding of the intrinsically disordered CcdA antitoxin domain to the toxin CcdB from ccdAB TA module (53). The negative enthalpy change likely originates from the folding of the N-terminal domain (in particular the formation of an α-helix) and from specific interactions between VcHigB2 and VcHigA2. The unfavorable entropic contributions likely originate from the reduction of rotational and translational degrees of freedom due to the association of VcHigB2 and VcHigA2 molecules and from the reduction of conformational degrees of freedom due to the folding of the N-terminal domain of VcHigA2. Moreover, the binding is associated with a decrease of the heat capacity. The obtained experimental value of −0.95 kcal mol−1 K−1 is in agreement with the corresponding heat capacity change estimated on the basis of changes of the accessible surface areas (−1.05 ± 0.08 kcal mol−1 K−1) (45) and suggests that the binding is accompanied by a favorable desolvation entropy contribution.

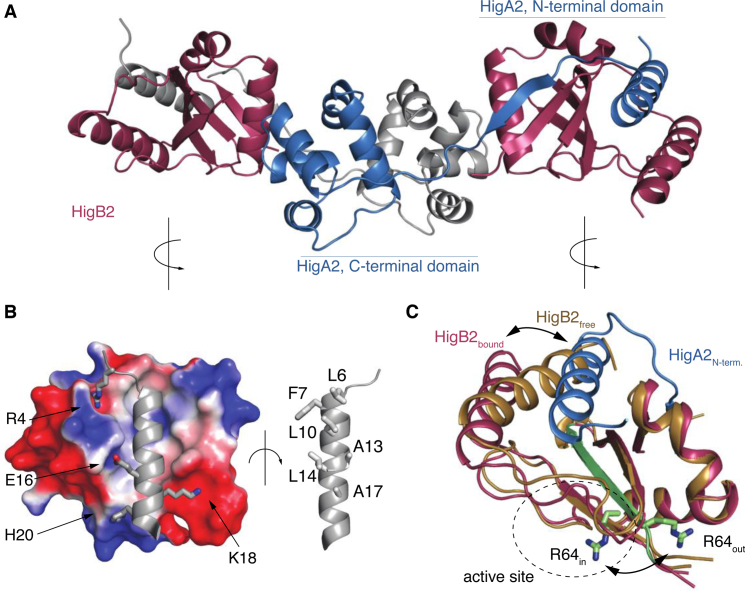

Structure of the heterotetrameric VcHigBA2 complex

Crystals of the VcHigBA2 complex contain a VcHigA2 dimer of which the extended N-termini fold and wrap around VcHigB2 to form an elongated HigB2-HigA2-HigA2-HigB2 heterotetramer (Figure 4A). The electron density is clear and continuous except for the affinity tags and again the positively charged β2-β3 loop of VcHigB2. The N-terminal region of VcHigA2 folds into an N-terminal α-helix (residues 3–22) followed by a short β-strand (residues 28–37). This β-strand is added to the β-sheet core of VcHigB2 while the α-helix binds along the β-sheet surface. The structure of the N-terminal segment of VcHigA2 does not possess a hydrophobic core on its own, in agreement with our observations that in solution and in absence of VcHigB2, this segment remains unfolded.

Figure 4.

Structure of the heterotetrameric VcHigBA2 complex. (A) Overall structure of the complex. The two VcHigB2 toxins are in red, the two chains of the antitoxin dimer are in gray and blue. (B) Interactions between the toxin and the antitoxin's N-terminal domain. The electrostatic surface of the VcHigB2 toxin was calculated with ABPS using default parameters (60). (C) Conformational changes in the VcHigB2 induced by binding to VcHigA2. The antitoxin N-terminal helix (blue) partially displaces the VcHigB2 C-terminal helix (toxin in its free state is shown in gold, toxin in the bound state in red) and shifts the register of the β-strand β3 (green). The two positions of the catalytically important Arg64 are shown in sticks.

The interaction between VcHigA2 and VcHigB2 buries a total of 5300 Å2 of solvent accessible surface, most of which is accounted for by the binding of the antitoxin N-terminal helix. Nonpolar residues along one side of the VcHigA2 N-terminal helix are facing the β-sheet surface of VcHigB2, thereby creating an extended hydrophobic core (Figure 4B). On the opposite side of the VcHigA2 N-terminal helix several charged residues tighten the binding via electrostatic interactions (Figure 4B). In addition to the interactions with the N-terminal domain of VcHigA2, there is an additional binding interface employing the globular domain of VcHigA2. This involves positioning of the VcHigB2 α2 helix into a hydrophobic cleft formed by helices α2 and α3 of the VcHigA2 antitoxin. However, the observed ITC curves accompanying binding of the VcHigA23-22 peptide and the full-length antitoxin to the VcHigB2 are very similar, suggesting that the major contributions to binding affinity come from the interaction between VcHigA2 N-terminal domain and VcHigB2 while the interactions between the globular domains are less important (Supplementary Figure S7). This is in line with our activity experiments that suggest that the first 20 amino acids from the disordered HigA2 N-terminus regulate the toxin activity.

Conformational changes of VcHigB2 upon VcHigA2 binding

Comparison of the conformations of VcHigB2 in the nanobody complexes with the conformation observed in the VcHigBA2 complex reveals two major differences: a displacement of the C-terminal helix α3 and a one-residue register shift in β-strand 3 (Figure 4C). The helix displacement is a direct consequence of the interaction with N-terminal helix of VcHigA2, since both helices compete for an overlapping anchor site on the β-sheet surface (Figure 4C). In its novel position the α3 is rotated by ∼30°. The N-end roughly retains its original position, while the C-end is displaced by ∼13 Å compared to its position in the nanobody-bound VcHigB2.

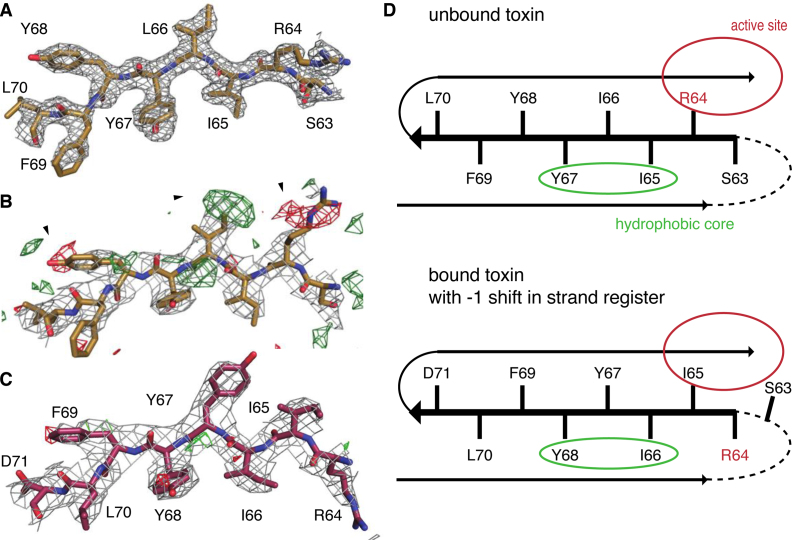

β-strand β3 consists of amino acid sequence 63-SRIIYYFL-70 and its central residues are part of the VcHigB2 hydrophobic core. The electron density of this sequence is clear and allows unambiguous tracing of the polypeptide chain from the Arg60 or Gly62 in the in nanobody-VcHigB2 structures (Figure 5A). Surprisingly, when this model is used to refine the structure of the VcHigBA2 complex, clear difference peaks in mFo-DFc maps suggested an alternative tracing of the polypeptide (Figure 5B). A model with the amino acid sequence of β3 shifted by one residue (−1 shift in the β-strand register) clearly describes the data better (Figure 5C). Remarkably, this shifted conformation does not disrupt the hydrophobic packing interactions between β-sheet and the helices α1 and α2 of the VcHigB2, because the four central hydrophobic residues are a repeat (65-IIYY-68), and therefore the positions of Ile65 and Tyr67 (in the Nb−VcHigB2 complexes) are mimicked by Ile66 and Tyr68 in the VcHigBA2 complex (Figure 5D). The shift in the β-strand register comes with a structural change likely crucial for the activity of the VcHigB2 toxin. In the nanobody complexes Arg64, which is part of the active site, is oriented correctly relative to the other active site residues (in-conformation). In contrast, in the VcHigBA2 complex the register shift flips this side chain to the opposite plane of the β-sheet (out-conformation) (Figures 4C and 5D). In the slided conformation the β3-β4 loop is one residue shorter, while β2-β3 loop is extended for one residue, but remains disordered in both conformations.

Figure 5.

Sliding of VcHigB2 strand β3. (A) Model of the strand β3 from the Nb6-VcHigB2 structure and the corresponding 2mFo-DFc map contoured at 1 σ (resolution 1.85 Å). (B) Positive (green) and negative (red) peaks in the mFo-DFc map contoured at 3 σ suggest a different tracing of the sequence of strand β3 in the VcHigBA2 complex. (C) 2mFo-DFc and mFo-DFc maps (contoured at 1 σ and 3 σ, respectively; resolution 3 Å) for the final model of strand β3 in the VcHigBA2 complex. (D) Schematic figure displaying strand β3 in both conformations. Unstructured β2-β3 loop is shown as dashed line, locations of the active site and solvent-inaccessible hydrophobic core are circled. Slided conformation (bottom) does not perturb the hydrophobic packing due to a sequence repeat.

DISCUSSION

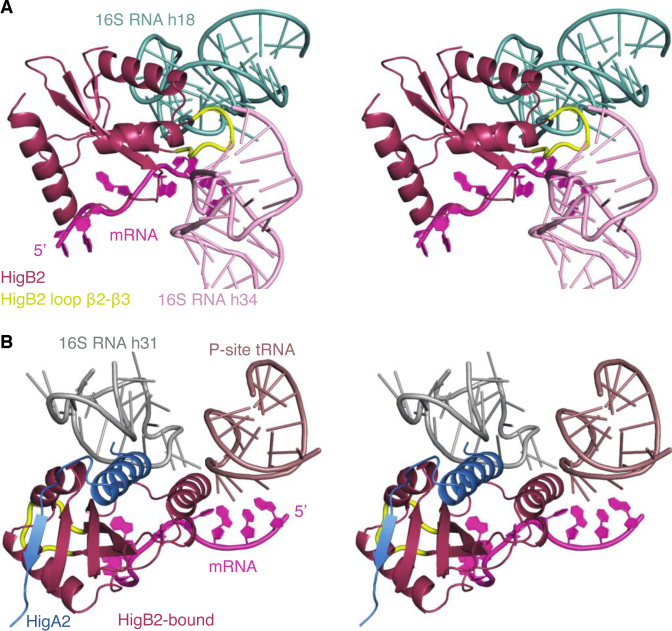

The higBA module on plasmid Rts1 was the first TA module discovered with an inverted gene organization, the toxin gene being located upstream of the antitoxin gene. Since then, the name ‘higBA’ has been used for a plethora of TA modules where a toxin gene (weakly) related to relE is followed by an antitoxin gene that encodes a helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif. Our crystal structures show that the proteins encoded by the V. cholerae chromosomal higBA2 module differ in significant aspects from those of the plasmid encoded Rts1 module (17) and that defining a distinct higBA family based solely on the gene order of toxin and antitoxin may be misleading. The toxin VcHigB2 shows a much stronger similarity to the classic E. coli RelE both in terms of overall structure and in its atypical combination of the catalytic residues. The most striking difference between VcHigB2 and EcRelE is the sequence of loop β2-β3, which in VcHigB2 is longer, rich in lysines and remains disordered. Substitution of this loop for a sequence of three alanines impairs toxin activity (Figure 1C). Superposition of VcHigB2 on ribosome-bound EcRelE (PDB ID: 4V7J, (12)) suggests that this loop might form extensive interactions with the 16S RNA helices 18 and 34 (Figure 6A). EcRelE interacts with the ribosomal RNA via two Lys and Arg-rich patches involving helices α1 and α2 (12). The same basic patches also mediate binding to the ribosomal A site in YoeB, YafQ and PvHigB mRNAses (13,14,54). Surprisingly in VcHigB2, helices α1 and α2 are not charged and superposition of VcHigB2 on ribosome-bound EcRelE shows minimal contacts between the ribosomal RNA and helices α1 and α2 of VcHigB2 (only Lys13 from α1 seems to interact with 16S RNA helix 31). Given the absence of other contacts between the ribosome scaffold and the VcHigB2 toxin, the positively charged β2-β3 loop likely mediates binding of the VcHigB2 to the ribosomal A site by electrostatic interactions with the 16S RNA.

Figure 6.

Model of the VcHigB2 toxin bound to the ribosome. The model was obtained by the superposition of the VcHigB2 toxin on EcRelE in the EcRelE–ribosome complex (PDB ID: 4V7J). (A) VcHigB2 positively charged β2-β3 loop (highlighted in yellow) interacts with helies 18 and 34 from the 16S RNA. The conformation of the β2-β3 loop was optimized using ModLoop web server (61). (B) VcHigB2 toxin with bound VcHigA23-33 peptide placed in the VcHigB2 binding site of ribosome using the EcRelE–ribosome complex (PDB ID: 4V7J) as a guide. No obvious clashes are observed between the ribosome or the mRNA substrate and VcHigB2 or VcHigA23-33.

The relation between V. cholerae higBA2 and E. coli relBE comes with an interesting switch in genetic organization. Not only does the VchigBA2 module have an inverted gene organization, the arrangement of the two functional domains of the VcHigA2 antitoxin is inverted as well. The intrinsically disordered toxin-neutralizing domain is located N-terminal to the DNA binding domain, unlike in the EcRelB as well as most other modular antitoxins (55). In stark contrast, PvHigA lacks the toxin-binding intrinsically disordered domain and binds the toxin with the globular domain (17). The IDP domain of VcHigA2 folds upon binding in an extended structure consisting of an α-helix followed by a β-strand. This motif is omnipresent in relBE-related TA modules (e.g. dinJ-yafQ, yoeB-yefM, (55)) where this α-helix acts as the main regulatory element to control the activity of the toxin.

The inhibition of the ribosome-dependent mRNases such as VcHigB, RelE, YoeB and YafQ by their cognate antitoxins, can be explained by the formation of large TA complexes, which cannot enter the ribosomal A site. Yet, in all cases the previously mentioned α-helical toxin-binding motif are sufficient to neutralize these toxins, often involving rearrangements in the active sites. For example, binding of the YefM C-terminal helix to YoeB induces a conformational rearrangement of the active site residues of the YeoB toxin (15). The C-terminal domain of DinJ directly covers the active site of the YafQ toxin (19,20) and binding of EcRelB displaces the C-terminal helix of EcRelE, thereby distancing the catalytically important Tyr87 from the active site (16). Thus, in general short toxin-binding motifs act as minimal regulatory elements for the corresponding toxins and the perturbation of the active site is a general strategy for toxin inhibition. Indeed, our data show that the VcHigA2 N-terminal domain containing the neutralization helix (peptide VcHigA23-22) is sufficient to neutralize VcHigB2 (Figure 3A).

Like the C-terminal α-helix of EcRelB, the N-terminal α-helix from VcHigA2 displaces helix α3 of VcHigB2. Displacement of α3 of VcHigB2 does not perturb the active site of VcHigB2 directly and in contrast to EcRelE this helix does bear a catalytically important residue. Indeed the functional equivalent of Tyr87 located on helix α3 of EcRelE is Tyr82 which is located on strand β4 of VcHigB2 (Figure 1B). Even though there are no obvious large clashes between peptide-bound VcHigB2 and the ribosome scaffold (Figure 6B) the VcHigA23-22 peptide prevents binding to the ribosome (Figure 3B).This may be explained by the observation of dynamic nature of the β3 strand. In the slided conformation the Arg64 can be found in or out of the active site due to the shift in the β-strand register (Figure 5D). Its structural homolog Arg61 from EcRelE binds the mRNA molecule and has been identified as stabilizer of the negatively charged transition state (51). In all three nanbody-VcHigB2 structures the Arg64 is found in the active in-conformation and interacts with the sulphate or phosphate ions from the crystallization solution (Figure 1A). On the other hand in the structure of the VcHigBA2 complex, Arg64 is flipped to the other side of the β-strand and is no longer part of the active site and it cannot interact with mRNA molecule. Moreover, sliding of the β3 stand also extends the β2-β3 loop, which probably disrupts interactions with the ribosome (Figure 6B).

The sequence of strand β3 seems to acts as a ‘chameleon’ sequence and the VcHigB2 exists in two conformations (active ‘in’ and non-active ‘out’). This β-strand sliding toward the ‘out’ conformation would then need to be induced though the binding of the N-terminal helix of VcHigA2. In addition, the interaction of VcHigB2 loop β2-β3 with the ribosome may help to stabilize the active ‘in’ conformation. Several examples of functional shifts in the β-strand registers have also been described in other proteins, for example during the signal transduction of the BLUF photoreceptor (56,57) and in the Arf1 and Arl3 GTPases (58,59), but the mechanism of β-strand sliding is poorly understood. This is the first observation of β-strand sliding in a ribonuclease and further research might clarify how the two conformations of VcHigB2 are interconverted.

ACESSION NUMBERS

PDB IDs: 5J9I, 5JA8, 5JA9, 5JAA and 5MJE.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Andrew Thompson for excellent beamline support.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen [G.0135.15N, G0C1213N, G.0090.11N]; Onderzoeksraad of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel [OZR2232 to S.H., SPR13]; European Community's Seventh Framework Programme under BioStruct-X (projects 1673 and 6131) [FP7/2007-2013]; Hercules Foundation [UABR/11/012]; Danish National Research Foundation [Grant identifier DNRF120]; Slovenian Research Agency [P1–0201]. Funding for open access charge: Slovenian Research Agency [P1–0201]; Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen [G.0135.15N, G0C1213N, G.0090.11N].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Leplae R., Geeraerts D., Hallez R., Guglielmini J., Dreze P., Van Melderen L.. Diversity of bacterial type II toxin-antitoxin systems: a comprehensive search and functional analysis of novel families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:5513–5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pandey D.P., Gerdes K.. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005; 33:966–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gerdes K., Rasmussen P.B., Molin S.. Unique type of plasmid maintenance function: postsegregational killing of plasmid-free cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986; 83:3116–3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gerdes K., Maisonneuve E.. Bacterial persistence and toxin-antitoxin loci. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012; 66:103–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buts L., Lah J., Dao-Thi M.H., Wyns L., Loris R.. Toxin-antitoxin modules as bacterial metabolic stress managers. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005; 30:672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewis K. Persister cells. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010; 64:357–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brzozowska I., Zielenkiewicz U.. Regulation of toxin-antitoxin systems by proteolysis. Plasmid. 2013; 70:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Christensen S.K., Pedersen K., Hansen F.G., Gerdes K.. Toxin-antitoxin loci as stress-response-elements: ChpAK/MazF and ChpBK cleave translated RNAs and are counteracted by tmRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2003; 332:809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jorgensen M.G., Pandey D.P., Jaskolska M., Gerdes K.. HicA of Escherichia coli defines a novel family of translation-independent mRNA interferases in bacteria and archaea. J. Bacteriol. 2009; 191:1191–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pedersen K., Zavialov A.V., Pavlov M.Y., Elf J., Gerdes K., Ehrenberg M.. The bacterial toxin RelE displays codon-specific cleavage of mRNAs in the ribosomal A site. Cell. 2003; 112:131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cruz J.W., Woychik N.A.. tRNAs taking charge. Pathog. Dis. 2016; 74, doi:10.1093/femspd/ftv117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Neubauer C., Gao Y.G., Andersen K.R., Dunham C.M., Kelley A.C., Hentschel J., Gerdes K., Ramakrishnan V., Brodersen D.E.. The structural basis for mRNA recognition and cleavage by the ribosome-dependent endonuclease RelE. Cell. 2009; 139:1084–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schureck M.A., Dunkle J.A., Maehigashi T., Miles S.J., Dunham C.M.. Defining the mRNA recognition signature of a bacterial toxin protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:13862–13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feng S., Chen Y., Kamada K., Wang H., Tang K., Wang M., Gao Y.G.. YoeB-ribosome structure: a canonical RNase that requires the ribosome for its specific activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:9549–9556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kamada K., Hanaoka F.. Conformational change in the catalytic site of the ribonuclease YoeB toxin by YefM antitoxin. Mol. Cell. 2005; 19:497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li G.Y., Zhang Y., Inouye M., Ikura M.. Inhibitory mechanism of Escherichia coli RelE-RelB toxin-antitoxin module involves a helix displacement near an mRNA interferase active site. J. Biol. Chem. 2009; 284:14628–14636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schureck M.A., Maehigashi T., Miles S.J., Marquez J., Cho S.E., Erdman R., Dunham C.M.. Structure of the Proteus vulgaris HigB-(HigA)2-HigB toxin-antitoxin complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2014; 289:1060–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown B.L., Grigoriu S., Kim Y., Arruda J.M., Davenport A., Wood T.K., Peti W., Page R.. Three dimensional structure of the MqsR:MqsA complex: a novel TA pair comprised of a toxin homologous to RelE and an antitoxin with unique properties. PLoS Pathog. 2009; 5:e1000706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ruangprasert A., Maehigashi T., Miles S.J., Giridharan N., Liu J.X., Dunham C.M.. Mechanisms of toxin inhibition and transcriptional repression by Escherichia coli DinJ-YafQ. J. Biol. Chem. 2014; 289:20559–20569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liang Y., Gao Z., Wang F., Zhang Y., Dong Y., Liu Q.. Structural and functional characterization of Escherichia coli toxin-antitoxin complex DinJ-YafQ. J. Biol. Chem. 2014; 289:21191–21202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tian Q.B., Ohnishi M., Tabuchi A., Terawaki Y.. A new plasmid-encoded proteic killer gene system: cloning, sequencing, and analyzing hig locus of plasmid Rts1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996; 220:280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamaguchi Y., Park J.H., Inouye M.. MqsR, a crucial regulator for quorum sensing and biofilm formation, is a GCU-specific mRNA interferase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2009; 284:28746–28753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heaton B.E., Herrou J., Blackwell A.E., Wysocki V.H., Crosson S.. Molecular structure and function of the novel BrnT/BrnA toxin-antitoxin system of Brucella abortus. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287:12098–12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Christensen-Dalsgaard M., Gerdes K.. Two higBA loci in the Vibrio cholerae superintegron encode mRNA cleaving enzymes and can stabilize plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 2006; 62:397–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Budde P.P., Davis B.M., Yuan J., Waldor M.K.. Characterization of a higBA toxin-antitoxin locus in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 2007; 189:491–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hurley J.M., Woychik N.A.. Bacterial toxin HigB associates with ribosomes and mediates translation-dependent mRNA cleavage at A-rich sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2009; 284:18605–18613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hadzi S., Garcia-Pino A., Martinez-Rodriguez S., Verschueren K., Christensen-Dalsgaard M., Gerdes K., Lah J., Loris R.. Crystallization of the HigBA2 toxin-antitoxin complex from Vibrio cholerae. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2013; 69:1052–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sterckx Y.G., De Gieter S., Zorzini V., Hadzi S., Haesaerts S., Loris R., Garcia-Pino A.. An efficient method for the purification of proteins from four distinct toxin-antitoxin modules. Protein Exp. Purif. 2015; 108:30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pace C.N., Vajdos F., Fee L., Grimsley G., Gray T.. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995; 4:2411–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Korber P., Stahl J.M., Nierhaus K.H., Bardwell J.C.A.. Hsp 15: a ribosome-associated heat shock protein. EMBO J. 2000; 19:741–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buck M., Connick M., Ames B.N.. Complete analysis of transfer-Rna modified nucleosides by high-performance liquid-chromatography—the 29 modified nucleosides of Salmonella-Typhimurium and Escherichia-Coli transfer-Rna. Anal. Biochem. 1983; 129:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kabsch W. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010; 66:133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sheldrick G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A. 2008; 64:112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCoy A.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D., Winn M.D., Storoni L.C., Read R.J.. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007; 40:658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cowtan K. Recent developments in classical density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010; 66:470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006; 62:1002–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkoczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010; 66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W.G., Cowtan K.. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010; 66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vincke C., Loris R., Saerens D., Martinez-Rodriguez S., Muyldermans S., Conrath K.. General strategy to humanize a camelid single-domain antibody and identification of a universal humanized nanobody scaffold. J. Biol. Chem. 2009; 284:3273–3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. David G., Perez J.. Combined sampler robot and high-performance liquid chromatography: a fully automated system for biological small-angle X-ray scattering experiments at the Synchrotron SOLEIL SWING beamline. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009; 42:892–900. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Petoukhov M.V., Franke D., Shkumatov A.V., Tria G., Kikhney A.G., Gajda M., Gorba C., Mertens H.D.T., Konarev P.V., Svergun D.I.. New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012; 45:342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rambo R.P., Tainer J.A.. Accurate assessment of mass, models and resolution by small-angle scattering. Nature. 2013; 496:477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bernado P., Mylonas E., Petoukhov M.V., Blackledge M., Svergun D.I.. Structural characterization of flexible proteins using small-angle X-ray scattering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007; 129:5656–5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hubbard J., Thornton J.. NACCESS, Computer Program. 1993; London: University College. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murphy K.P., Freire E.. Thermodynamics of structural stability and cooperative folding behavior in proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 1992; 43:313–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Takagi H., Kakuta Y., Okada T., Yao M., Tanaka I., Kimura M.. Crystal structure of archaeal toxin-antitoxin RelE-RelB complex with implications for toxin activity and antitoxin effects. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005; 12:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Boggild A., Sofos N., Andersen K.R., Feddersen A., Easter A.D., Passmore L.A., Brodersen D.E.. The crystal structure of the intact E. coli RelBE toxin-antitoxin complex provides the structural basis for conditional cooperativity. Structure. 2012; 20:1641–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dalton K.M., Crosson S.. A conserved mode of protein recognition and binding in a ParD-ParE toxin-antitoxin complex. Biochemistry. 2010; 49:2205–2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sterckx Y.G.J., Jove T., Shkumatov A.V., Garcia-Pino A., Geerts L., De Kerpel M., Lah J., De Greve H., Van Melderen L., Loris R.. A unique hetero-hexadecameric architecture displayed by the Escherichia coli O157 PaaA2-ParE2 antitoxin-toxin complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2016; 428:1589–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Griffin M.A., Davis J.H., Strobel S.A.. Bacterial toxin RelE: a highly efficient ribonuclease with exquisite substrate specificity using atypical catalytic residues. Biochemistry. 2013; 52:8633–8642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dunican B.F., Hiller D.A., Strobel S.A.. Transition state charge stabilization and acid-base catalysis of mRNA cleavage by the endoribonuclease RelE. Biochemistry. 2015; 54:7048–7057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bernado P., Svergun D.I.. Structural analysis of intrinsically disordered proteins by small-angle X-ray scattering. Mol. Biosyst. 2012; 8:151–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Drobnak I., De Jonge N., Haesaerts S., Vesnaver G., Loris R., Lah J.. Energetic basis of uncoupling folding from binding for an intrinsically disordered protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013; 135:1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maehigashi T., Ruangprasert A., Miles S.J., Dunham C.M.. Molecular basis of ribosome recognition and mRNA hydrolysis by the E. coli YafQ toxin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:8002–8012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Loris R., Garcia-Pino A.. Disorder- and dynamics-based regulatory mechanisms in toxin-antitoxin modules. Chem. Rev. 2014; 114:6933–6947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yuan H., Anderson S., Masuda S., Dragnea V., Moffat K., Bauer C.. Crystal structures of the Synechocystis photoreceptor Slr1694 reveal distinct structural states related to signaling. Biochemistry. 2006; 45:12687–12694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mehlhorn J., Lindtner T., Richter F., Glass K., Steinocher H., Beck S., Hegemann P., Kennis J.T., Mathes T.. Light-Induced Rearrangement of the beta5 Strand in the BLUF Photoreceptor SyPixD (Slr1694). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015; 6:4749–4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Goldberg J. Structural basis for activation of ARF GTPase: mechanisms of guanine nucleotide exchange and GTP-myristoyl switching. Cell. 1998; 95:237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hillig R.C., Hanzal-Bayer M., Linari M., Becker J., Wittinghofer A., Renault L.. Structural and biochemical properties show ARL3-GDP as a distinct GTP binding protein. Structure. 2000; 8:1239–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Baker N.A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M.J., McCammon J.A.. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001; 98:10037–10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fiser A., Sali A.. ModLoop: automated modeling of loops in protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2003; 19:2500–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.