Abstract

Aberrant CpG dinucleotide methylation in a specific region of the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter is associated with increased TERT mRNA levels and malignancy in several cancer types. However, routine screening of this region to aid cancer diagnosis can be challenging because i) several established methylation assays may inaccurately report on hypermethylation of this particular region, ii) interpreting the results of methylation assays can sometimes be difficult for clinical laboratories, and iii) use of high-throughput methylation assays for a few patient samples can be cost prohibitive. Herein, we describe the use of combined bisulfite restriction enzyme analysis (COBRA) as a diagnostic tool for detecting the hypermethylated TERT promoter using in vitro methylated and unmethylated genomic DNA as well as genomic DNA from four melanomas and two benign melanocytic lesions. We compare COBRA with MassARRAY, a more commonly used high-throughput approach, in screening for promoter hypermethylation in 28 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded neuroblastoma samples. COBRA sensitively and specifically detected samples with hypermethylated TERT promoter and was as effective as MassARRAY at differentiating high-risk from benign or low-risk tumors. This study demonstrates the utility of this low-cost, technically straightforward, and easily interpretable assay for cancer diagnosis in tumors of an ambiguous nature.

The telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) oncogene encodes the rate-limiting catalytic subunit of telomerase, the enzyme required by virtually all proliferative cells to maintain the integrity of chromosomal ends.1, 2 Cancer cell lines and tissues have an uncontrolled capacity for proliferation, and TERT mRNA levels are inappropriately elevated through diverse mechanisms in approximately 85% to 90% of these cases.3, 4, 5 Certain mechanisms of TERT dysregulation predominate in some cancer types but not others. For example, activating point mutations in the TERT promoter are common in cancers such as melanoma, glioblastoma, thyroid cancer, bladder cancer, and liver cancer,6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 but not in others such as bone and soft tissue sarcomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, gastric cancer, and pancreatic cancer.13, 14, 15, 16 Similarly, copy number amplification of TERT is more common in medulloblastoma, lung cancer, cervical cancer, and breast cancer,17, 18, 19, 20 whereas structural rearrangements involving TERT are found in B-cell malignancies, neuroblastoma (NBL), and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma.10, 21, 22, 23

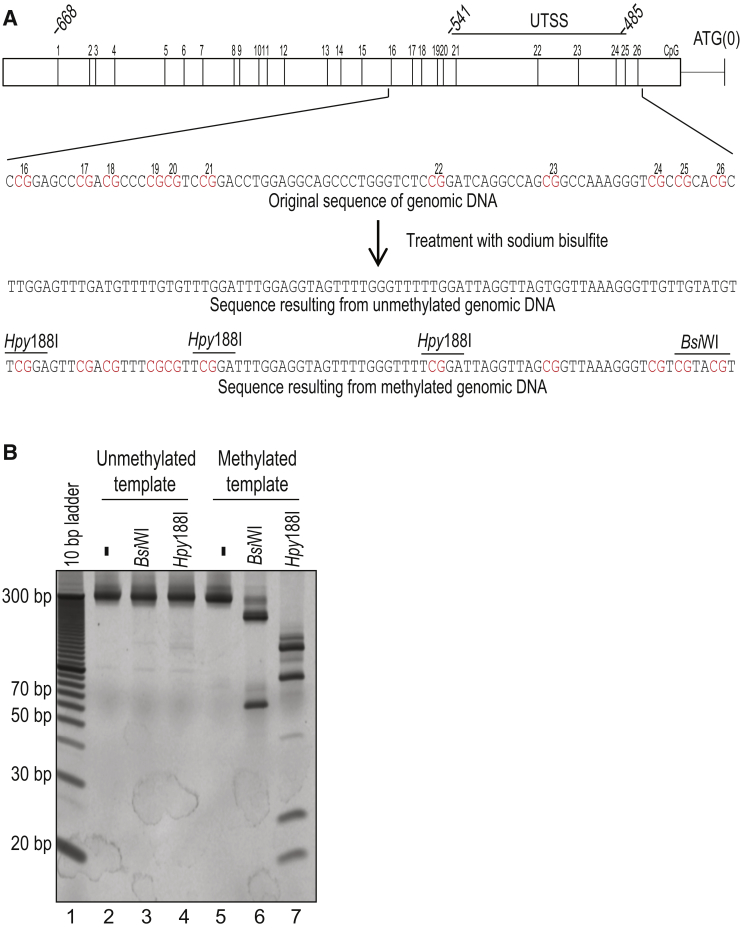

In addition to these genetic mechanisms of TERT dysregulation, a prominent epigenetic mechanism associated with cancer is CpG dinucleotide hypermethylation in the upstream of transcription start site (UTSS), a region located −541 to −485 bp upstream of the start codon of TERT (Figure 1A).24, 25 Hypermethylation of CpG dinucleotides in the UTSS is associated with increased TERT mRNA levels and poorer patient outcomes24, 25, 26 and frequently occurs in medulloblastoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, and prostate, esophageal, gastric, colorectal, and cervical cancer.17, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 More important, for diagnostic purposes, these CpG dinucleotides are unmethylated or significantly less methylated in benign tumors and normal tissues, including nonneoplastic but proliferative cells expressing TERT mRNA, such as activated lymphocytes, embryonic stem cells, testis, and hematopoietic stem cells.24, 25, 28, 33, 34

Figure 1.

COBRA can distinguish hypermethylated from unmethylated UTSS through the PCR-RFLPs generated by the bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA. A: Map showing the positions of 26 CpG dinucleotides located in the proximal TERT promoter [nucleotides 1295772 to 1295104 on chromosome 5 (GRCh37/hg19)]. The five CpG dinucleotides within the UTSS, located −485 to −541 bp upstream of the translation start site (ATG), are indicated. The genomic sequence of the UTSS before bisulfite treatment, as well as the resulting sequences after bisulfite conversion if none or all of the CpG dinucleotides in the UTSS are protected by methylation, are shown. CpG dinucleotides are highlighted in red, and BsiWI (5′-CGTACG-3′) and Hpy188I (5′-TCNGA-3′) restriction sites generated by bisulfite treatment are indicated. B: Restriction digestion of the UTSS PCR product from bisulfite-treated unmethylated (lanes 2 to 4) or methylated (lanes 5 to 7) genomic DNA. Dashes above lanes 2 and 5 indicate that no restriction enzyme was added to those reactions. Identical blotches observed on a subset of gels are the result of residue present on the surface on which those gels were imaged.

The discovery that TERT promoter methylation is a unique characteristic of cancer cells has prompted the use of different methylation assays to specifically detect this event for cancer diagnosis. However, these assays have yet to be adopted in clinical laboratories mainly because applying high-throughput or difficult-to-interpret methylation assays to predict patient outcomes in routine clinical practice is challenging and cost prohibitive. Recent improvements in experimental protocols, ease of analysis, and cost may facilitate the use of such high-throughput assays in the clinic.35

Combined bisulfite restriction enzyme analysis (COBRA) is a simple, sensitive, and low-cost assay for detecting DNA methylation at specific genetic loci. In this study, we demonstrate the effectiveness of COBRA in detecting TERT promoter UTSS hypermethylation in tumor samples, and compare it to detection by the high-throughput MassARRAY approach. In COBRA, hypermethylation of CpG dinucleotides results in their protection from cytosine to uracil conversion by sodium bisulfite that results in PCR restriction fragment length polymorphisms (PCR-RFLPs). PCR-RFLPs can distinguish DNA amplified from methylated and unmethylated UTSS. The appearance of short restriction fragments after BsiW1, Hpy188I, or Hpy99I digestion indicates the presence of hypermethylated UTSS in a sample and, thus, cancer. We demonstrate that this approach is highly robust, easy to perform and interpret, and reliable in distinguishing high-risk malignant tumors from low-risk and benign lesions.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Samples

Tumor samples from two cohorts—the melanoma cohort and the NBL cohort—were analyzed with institutional review board approval. For the melanoma cohort, samples included four malignant melanomas arising in a giant congenital nevus and two benign proliferative nodules in the giant congenital nevus. For this cohort, tumor characteristics and UTSS methylation status by next-generation bisulfite sequencing have been previously described.36 For the NBL cohort, samples included 28 tumors, classified as 12 high-risk, 5 intermediate-risk, and 11 low-risk NBL samples by the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group classification system.37, 38 Supplemental Table S1 gives clinicopathologic characteristics of the NBL cohort.

Purification of Genomic DNA and Bisulfite Treatment

Genomic DNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was isolated by using the Maxwell 16 FFPE Plus LEV DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI). From each sample, 500 ng of genomic DNA was modified with sodium bisulfite by using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Sodium bisulfite–treated DNA was used for bisulfite PCR amplification, as previously described.36

COBRA and Cloning

PCR amplification of the UTSS was performed by using GoTaq Long PCR Master Mix (Promega), as previously described,36 with primer set 1 (forward: 5′-GGAAGTGTTGTAGGGAGGTATTT-3′ and reverse: 5′-AAAACCATAATATAAAAACCCTAAA-3′), generating bisulfite amplicons of 244 bp, or primer set 2 (forward: 5′-AGGAAGAGAGGGGAAGTGTTGTAGGGAGGTATTT-3′ and reverse: 5′-CAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAAGGCTAAAAACCATAATATAAAAACCCTAAA-3′),24 generating bisulfite amplicons of 285 bp. Cycling parameters were as follows: 95°C for 15 seconds, 53°C for 20 seconds, and 68°C for 30 seconds for 45 cycles.

For COBRA, 3 to 5 μL of each 285- or 244-bp PCR amplicon was digested with BsiW1 or Hpy188I, according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). Samples were electrophoresed on Novex 20% polyacrylamide TBE gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), which were then stained with GelRed (Biotium, Fremont, CA) before visualization using an Odyssey Fc Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). To characterize the specificity of RFLP detection by COBRA, commercially prepared High Methylated (>85% methylation) and Low Methylated Human Genomic DNA (<5% methylation) samples were used as templates (EpigenDx, Hopkinton, MA). To determine the sensitivity of COBRA to detect methylated UTSS, premixed methylation calibration standards for human genomic DNA were used as templates (EpigenDx). For sequencing analysis, amplicons were cloned into the PCR2.1 vector, using blue/white selection (TOPO TA Cloning Kit with PCR2.1; Thermo Fisher Scientific), as per the manufacturer's instructions. Incorporation of insert of the expected length was verified by using T7 and M13 reverse-amplification primers, and 9 or 10 clones from each sample were randomly selected for sequencing.

MassARRAY

The UTSS PCR product was amplified from bisulfite-treated sample DNA, or from completely methylated or unmethylated control DNA, using primer set 2.24 These PCR products were used as templates for in vitro transcription reactions by using T7 RNA polymerase. The ensuing RNA transcripts were specifically cleaved at uracil residues, and differences in fragment sizes and charges from each sample were measured by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MassARRAY System; Agena Bioscience, San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed by the EpiTYPER software version 1.0 (Agena Bioscience), using a 10% cutoff value.

Results

COBRA Effectively Differentiates Methylated from Unmethylated TERT Promoters

Building on our recent study of TERT promoter hypermethylation in melanoma,36 we sought to use COBRA as a diagnostic screen for distinguishing malignant tumors from benign or low-grade tumors. First, the nucleotide sequence of this region, amplified from bisulfite-treated genomic DNA of both melanoma and benign samples, was analyzed to identify PCR-RFLPs that would be useful for differentiating hypermethylated from unmethylated UTSS.36 Restriction sites for BsiWI, Hpy188I, and Hpy99I were present in a PCR product amplified from hypermethylated but not unmethylated UTSS, contingent on bisulfite treatment of the sample DNA (Figure 1A). For example, BsiW1 digestion of a 285-bp PCR product amplified from a hypermethylated UTSS is expected to yield a 63-bp restriction fragment, although no such fragment will be generated if this template was originally unmethylated. Similarly, Hpy188I digestion of a PCR product amplified from the hypermethylated UTSS should yield both 21- and 26-bp fragments, both of which would be absent if this template was unmethylated.

To confirm these predictions, commercially available methylated and unmethylated genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite and used as a template for UTSS amplification. Each resulting PCR product was digested with either BsiW1 or Hpy188I (Figure 1B). As expected, the PCR product obtained from the methylated DNA was almost completely digested by each of these restriction endonucleases to yield smaller fragments of expected lengths. No such fragments were detected when the unmethylated DNA was used as a template, confirming that bisulfite treatment of the methylated, but not the unmethylated, promoter generated restriction sites recognized by these enzymes. Next, to measure the sensitivity of this approach for detecting methylated UTSS in an excess of unmethylated template, as is usually the case in actual patient samples, different ratios of bisulfite-treated methylated and unmethylated genomic DNA were mixed together before amplification. A mixture containing as little as 5% methylated DNA was successfully detected by this assay (Supplemental Figure S1).

We then tested the effectiveness of COBRA in accurately detecting hypermethylated UTSS in four cases of malignant melanoma, using two cases of benign proliferative nodules arising from the giant congenital nevus that had unmethylated UTSS as negative controls. Hypermethylated UTSS had previously been confirmed in all but one (sample S1001) of the melanoma samples by high-throughput bisulfite sequencing, as had the unmethylated UTSS in the benign samples.36 Genomic DNA from each sample was treated with sodium bisulfite and used as a template for UTSS amplification. On digestion with BsiW1 or Hpy188I, those PCR products derived from each of the four malignant melanoma samples yielded short restriction fragments characteristic of hypermethylated UTSS (Figure 2A), whereas the PCR products derived from the benign samples did not (Figure 2B). The presence of hypermethylated UTSS in sample S1001 was verified by cloning the amplified product and sequencing individual clones; four of nine clones sequenced were derived from hypermethylated UTSS (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

A and B: COBRA analysis of UTSS hypermethylation in melanoma samples (A) and proliferative nodules in the giant congenital nevus (B). Dashes indicate that no restriction enzyme was added to those reactions. C: Summary of sequencing results for each of the nine clones analyzed from melanoma case S1001, which was a tumor that was not previously analyzed by high-throughput bisulfite sequencing. Positions of each of the 26 CpG dinucleotides in this region are shown, and the region constituting the UTSS is indicated. Open and closed circles indicate unmethylated and methylated CpG dinucleotides, respectively. Asterisks indicate primer dimers approximately 90 bp long. Identical blotches observed on a subset of gels are the result of residue present on the surface on which those gels were imaged.

Overall, these results confirm the ability of COBRA to differentiate methylated from unmethylated TERT promoter UTSS, even in samples contaminated with nonneoplastic tissues, which are typically seen in the clinic.

COBRA Effectively Differentiates High-Risk NBL with Methylated TERT Promoter from Low- and Intermediate-Risk Tumors

Next, we compared the effectiveness of COBRA with that of MassARRAY, a high-throughput methylation assay, to identify NBL samples with hypermethylated UTSS. Although TERT hypermethylation is enriched in high-risk NBL as compared with low-risk NBL,21, 39 several other mutually exclusive mechanisms for TERT activation and telomere length maintenance occur frequently in this type of cancer.21, 40 We thus expected a range of genetic and epigenetic TERT-associated aberrations to be represented in this cohort. The NBL samples were well characterized in terms of clinicopathologic data and patient outcomes, and a range of NBL risk groups were represented (Supplemental Table S1).

We first screened the NBL samples by MassARRAY, requiring that all CpG dinucleotides positioned within the UTSS be methylated to score the entire UTSS as hypermethylated. To analyze MassARRAY data, a threshold must first be set to determine whether any given cytosine residue is methylated in each sample. Cytosine residues with methylation signals above this threshold are scored as methylated, whereas those with signals below the threshold are scored as unmethylated. To determine an appropriate threshold value to use, we first directly measured the proportion of hypermethylated UTSS in a subset of NBL samples by cloning the corresponding PCR products and sequencing 9 or 10 clones from each case. In each case, 10% to 30% of clones were derived from hypermethylated UTSS, although in some cases all clones were derived from unmethylated UTSS (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figures S2 and S3). On the basis of these results, 10% was used as the threshold for analysis because, at the least, 10% of the UTSS definitely harbored fully methylated CpG dinucleotides in the cases analyzed. Furthermore, a 10% threshold effectively separated the two groups into which the NBL samples naturally partitioned on the basis of average UTSS CpG dinucleotide methylation signal, according to a previous analysis (data not shown).41

Figure 3.

Detection of TERT promoter methylation patterns in an NBL cohort by COBRA and MassARRAY. A: Representative sequencing results for nine clones obtained from a patient with high-risk (HR) NBL. Open and closed circles indicate unmethylated and methylated CpG dinucleotides, respectively. B: Summary of MassARRAY results for CpG dinucleotide methylation in the TERT promoter. Hypermethylated CpG dinucleotides were identified on the basis of demonstration of ≥10% resistance to bisulfite conversion from cytosine to thymine, and are indicated in blue. CpG dinucleotides for which information was not available are shaded in gray. The tumor risk group was determined by clinical criteria and risk factors. Supplemental Table S1 summarizes the samples that showed evidence of alternative mechanisms of TERT up-regulation or of alternative lengthening of telomeres. C: Restriction patterns of the PCR-amplified product from NBL samples that gave positive signals in COBRA analysis. D: Representative restriction patterns of the PCR-amplified product from samples that gave negative signals in COBRA analysis. Asterisks indicate primer dimers. Dashes indicate that no restriction enzyme was added to those reactions. Identical blotches observed on a subset of gels are the result of residue present on the surface on which those gels were imaged. LR, low-risk.

Using these parameters, we performed MassARRAY on the 28 NBL tumor samples. Only four tumors, all from the high-risk group, harbored hypermethylated UTSS (Figure 3B and Supplemental Table S2). Interestingly, the eight remaining high-risk samples with unmethylated UTSS included cases of alternative mechanisms for TERT up-regulation, such as copy number amplification of N-myc21 or of TERT itself40 and genomic rearrangements involving the TERT loci21, 42 (Supplemental Table S1). TERT-independent alternative lengthening of telomeres was seen in three cases21, 42, 43 (Supplemental Table S1). All 11 low-risk and four intermediate-risk samples were identified as unmethylated by MassARRAY, and no other compensating mechanism was observed in these samples (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2).

The samples in the cohort were then screened by COBRA. Short fragments characteristic of hypermethylated UTSS were obtained from the same four high-risk tumors shown to have hypermethylated UTSS by MassARRAY (Figure 3C). None of the other 23 samples were identified as having hypermethylated UTSS by COBRA, which was consistent with results from MassARRAY (Figure 3D). These results indicate that COBRA is as effective as MassARRAY in distinguishing hypermethylated from unmethylated UTSS in NBL tumor samples. Interestingly, one NBL sample (NBL33) was originally classified as an intermediate-risk tumor, but subsequently shown to be a high-risk NBL, ultimately leading to the patient's death. COBRA correctly diagnosed this tumor as having hypermethylated UTSS (Supplemental Figure S4), although this sample was not included in our comparison because of insufficient material for MassARRAY.

Overall, these results suggest that both COBRA and MassARRAY are useful in detecting hypermethylated UTSS in NBL tumors, despite the fact that only some cells in these samples might actually harbor this epigenetic lesion.

Discussion

We show that COBRA is a methylation assay that is well suited to screen for cancer because it is accurate, sensitive, inexpensive, and easy to perform and interpret. However, other methylation assays have also been used to detect the hypermethylated TERT promoter in tumor samples. For example, in methylation-specific PCR, primers are designed to specifically amplify sequences generated by bisulfite treatment of only the methylated or only unmethylated TERT promoter.31, 34, 44, 45, 46 This approach has not been consistently effective at detecting high-risk cancer, perhaps because different regions of the promoter have been targeted by different studies, and the regions amplified did not always include the UTSS.31, 34, 44, 45, 46 Furthermore, although methylation-specific PCR is highly sensitive, it is also prone to false-positive errors because of inadvertent cross-reactivity between primers assumed to only amplify the methylated promoter and the promoter that is actually unmethylated, or vice versa.47, 48, 49 For example, using the same amplification primer sequences previously assumed to be specific for the hypermethylated TERT promoter,46 we observed non-specific amplification from benign and normal tissues, which we had unambiguously determined by sequencing to have unmethylated UTSS (data not shown). In contrast, we observed no instance of false-positive error when using COBRA. Of note, false-positive errors in COBRA cannot occur because of incomplete bisulfite treatment of a sample, because incomplete treatment only weakens the intensity of short restriction fragments used for diagnosis but cannot spuriously cause them to appear.

TaqMan probes have previously been used to increase the specificity and sensitivity of detection (approximately 0.5%) of the methylated over the unmethylated TERT promoter in patient samples.50, 51 Using this approach, significant correlations between disease progression and promoter hypermethylation, either alone or in combination with epigenetic dysregulation of other promoters, have been observed for lung, cervical, and leptomeningeal metastatic tumors but not for ovarian cancer.28, 32, 33, 50 A study that analyzed three of the five CpG dinucleotides in the UTSS using a 23 nucleotide-long TaqMan probe reported excellent diagnostic results.28 In this report, no false-positive errors were seen and fewer false-negative errors occurred than that with previously used biomarkers. However, the fact that a relatively long TaqMan probe would be required to span all CpG dinucleotides in the UTSS could result in technical complications as longer TaqMan probes tend to misanneal to heterogeneously methylated targets, as is sometimes the case with the UTSS.24, 51

Finally, high-throughput methylation assays such as high-throughput bisulfite sequencing, pyrosequencing, MassARRAY (alias Sequenom analysis), and methylation-specific microarray have been used as diagnostic tools to detect TERT promoter hypermethylation in cancer.17, 24, 25, 27, 29, 39, 47, 52, 53, 54 However, these and other high-throughput methods are often costly when used on a case-by-case basis, and are sometimes ill suited to analyze the TERT promoter. The Illumina 450 K methylation-specific microarray, for example, is relatively easy to perform and has been used to screen for TERT promoter hypermethylation in neuroblastoma and pediatric brain tumor samples.39 However, this array and the more recently developed 850 K array do not include probes to detect UTSS hypermethylation. In fact, these arrays detect methylation of only one of the 26 CpG dinucleotides in the proximal TERT promoter (Figure 1), which can sometimes lead to false-negative diagnoses, and the 450 K array cannot differentiate malignant and benign tumors on the basis of TERT promoter hypermethylation alone.24 Of note, the MassARRAY methylation signal of almost all CpG dinucleotides in NBL70 passed the 10% threshold, except for the critical sites located in the UTSS (Figure 3B). This sample would probably have been incorrectly diagnosed by microarray as a high-risk case. COBRA, on the other hand, accurately identified it as a low-risk case, because this assay is primarily sensitive to the methylation status of the clinically relevant CpG dinucleotides (Supplemental Figure S5).

Another disadvantage of high-throughput approaches is that it is sometimes difficult to conclude whether different sites are all methylated on the same promoter or whether it only appears this way because of the aggregation methylation signal obtained for each of these sites, although each signal is generated on a separate promoter.52 The first case would correspond to a true hypermethylated UTSS and lead to the diagnosis of a malignant tumor, whereas the second case would correspond to mostly the unmethylated or singly methylated UTSS, leading to the diagnosis of a benign tumor. For example, MassARRAY suggested that both CpG dinucleotides 21 and 22 were methylated in NBL57, indicating a partially hypermethylated UTSS and the potential to develop into a malignant case (Figure 3B). However, COBRA correctly diagnosed this as a low-risk tumor, because the PCR product lacked the complete set of RFLPs required to generate the characteristic restriction fragments (Supplemental Figure S5). Presumably, the UTSS was methylated at site 21 in some tumor cells but at site 22 in other cells, but both sites were never simultaneously methylated. Hence, the results of COBRA are easily interpretable and unambiguous. Furthermore, they do not require cutoff values to be arbitrarily decided to assign promoter methylation status.

As our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that underpin TERT up-regulation in various cancer types advances, the use of promoter methylation as a biomarker for cancer is expected to become increasingly relevant. Although recent advances in high-throughput approaches are helping to make them more practical and affordable for clinical use,35 COBRA is particularly well suited for TERT promoter methylation analysis for the following reasons: i) it is specific for hypermethylated UTSS, resulting in a low rate of false-positive error; ii) it is sensitive, resulting in a low rate of false-negative error; iii) it is not confounded by methylation of surrounding CpG dinucleotides that are less diagnostically relevant; iv) it is easy and inexpensive to perform; v) it does not require arbitrary cutoffs to be made during analysis; and vi) it can distinguish methylation events that occur on the same promoter from those that occur on different promoters. COBRA could be an especially useful diagnostic tool for cancers such as melanoma in which UTSS hypermethylation is frequently observed, whereas additional diagnostic assays might be needed to account for compensatory mechanisms in cancers such as NBL. Further studies are required to measure the usefulness of this method for diagnosis in other cancers, especially those with particularly high basal levels of DNA methylation.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the NIH National Cancer Institute grant P30CA021765 (A.B.) and by ALSAC.

S.L. and S.B. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: A patent application (number 62/393,843) based in part on the method described in this article has been filed by S.L., S.B., and A.B.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2017.01.003.

Supplemental Data

Detection of hypermethylated UTSS in varying relative amounts in bisulfite-treated unmethylated and methylated genomic DNA by COBRA. Commercially prepared methylation calibration standards of human genomic DNA (EpigenDx) were used to prepare the template for PCR amplification of the UTSS. The resultant products were digested with either BsiW1 (top panel) or Hyp188I (bottom panel). Identical blotches observed on a subset of gels are the result of residue present on the surface on which those gels were imaged. M, markers.

Summary of sequencing results of clones derived from the remaining NBL samples with hypermethylated UTSS. Open and closed circles indicate unmethylated and methylated CpG dinucleotides, respectively. CpG dinucleotides for which the methylation state was uninterpretable after sequencing are indicated by brown circles. N/A, not available.

Summary of sequencing results of clones derived from the remaining NBL samples with unmethylated UTSS. Open and closed circles indicate unmethylated and methylated CpG dinucleotides, respectively. N/A, not available.

COBRA showing short restriction fragments characteristic of hypermethylated UTSS in a clinically aggressive NBL sample that had been incorrectly classified as a low-risk tumor on the basis of the risk stratification criteria.

COBRA of the remaining NBL samples with unmethylated UTSS. Identical blotches observed on a subset of gels are the result of residue present on the surface on which those gels were imaged.

References

- 1.Nandakumar J., Cech T.R. Finding the end: recruitment of telomerase to telomeres. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:69–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackburn E.H., Collins K. Telomerase: an RNP enzyme synthesizes DNA. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:1–9. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yi X., Shay J.W., Wright W.E. Quantitation of telomerase components and hTERT mRNA splicing patterns in immortal human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4818–4825. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.23.4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyerson M., Counter C.M., Eaton E.N., Ellisen L.W., Steiner P., Caddle S.D., Ziaugra L., Beijersbergen R.L., Davidoff M.J., Liu Q., Bacchetti S., Haber D.A., Weinberg R.A. hEST2, the putative human telomerase catalytic subunit gene, is up-regulated in tumor cells and during immortalization. Cell. 1997;90:785–795. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinagre J., Almeida A., Populo H., Batista R., Lyra J., Pinto V., Coelho R., Celestino R., Prazeres H., Lima L., Melo M., da Rocha A.G., Preto A., Castro P., Castro L., Pardal F., Lopes J.M., Santos L.L., Reis R.M., Cameselle-Teijeiro J., Sobrinho-Simoes M., Lima J., Maximo V., Soares P. Frequency of TERT promoter mutations in human cancers. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2185. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang F.W., Hodis E., Xu M.J., Kryukov G.V., Chin L., Garraway L.A. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1229259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horn S., Figl A., Rachakonda P.S., Fischer C., Sucker A., Gast A., Kadel S., Moll I., Nagore E., Hemminki K., Schadendorf D., Kumar R. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science. 2013;339:959–961. doi: 10.1126/science.1230062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Killela P.J., Reitman Z.J., Jiao Y., Bettegowda C., Agrawal N., Diaz L.A., Jr. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6021–6026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303607110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagel I., Szczepanowski M., Martin-Subero J.I., Harder L., Akasaka T., Ammerpohl O., Callet-Bauchu E., Gascoyne R.D., Gesk S., Horsman D., Klapper W., Majid A., Martinez-Climent J.A., Stilgenbauer S., Tonnies H., Dyer M.J., Siebert R. Deregulation of the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene by chromosomal translocations in B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2010;116:1317–1320. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-240440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinhold N., Jacobsen A., Schultz N., Sander C., Lee W. Genome-wide analysis of noncoding regulatory mutations in cancer. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1160–1165. doi: 10.1038/ng.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kool M., Jones D.T., Jager N., Northcott P.A., Pugh T.J., Hovestadt V. Genome sequencing of SHH medulloblastoma predicts genotype-related response to smoothened inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akaike K., Toda-Ishii M., Suehara Y., Mukaihara K., Kubota D., Mitani K., Takagi T., Kaneko K., Yao T., Saito T. TERT promoter mutations are a rare event in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:836. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1606-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang D.S., Wang Z., He X.J., Diplas B.H., Yang R., Killela P.J., Meng Q., Ye Z.Y., Wang W., Jiang X.T., Xu L., He X.L., Zhao Z.S., Xu W.J., Wang H.J., Ma Y.Y., Xia Y.J., Li L., Zhang R.X., Jin T., Zhao Z.K., Xu J., Yu S., Wu F., Liang J., Wang S., Jiao Y., Yan H., Tao H.Q. Recurrent TERT promoter mutations identified in a large-scale study of multiple tumour types are associated with increased TERT expression and telomerase activation. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:969–976. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koelsche C., Renner M., Hartmann W., Brandt R., Lehner B., Waldburger N., Alldinger I., Schmitt T., Egerer G., Penzel R., Wardelmann E., Schirmacher P., von Deimling A., Mechtersheimer G. TERT promoter hotspot mutations are recurrent in myxoid liposarcomas but rare in other soft tissue sarcoma entities. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33:33. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-33-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito T., Akaike K., Kurisaki-Arakawa A., Toda-Ishii M., Mukaihara K., Suehara Y., Takagi T., Kaneko K., Yao T. TERT promoter mutations are rare in bone and soft tissue sarcomas of Japanese patients. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4:61–64. doi: 10.3892/mco.2015.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang N., Kjellin H., Sofiadis A., Fotouhi O., Juhlin C.C., Backdahl M., Zedenius J., Xu D., Lehtio J., Larsson C. Genetic and epigenetic background and protein expression profiles in relation to telomerase activation in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:21332–21346. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang A., Zheng C., Lindvall C., Hou M., Ekedahl J., Lewensohn R., Yan Z., Yang X., Henriksson M., Blennow E., Nordenskjold M., Zetterberg A., Bjorkholm M., Gruber A., Xu D. Frequent amplification of the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene in human tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6230–6235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshimoto M., Bayani J., Nuin P.A., Silva N.S., Cavalheiro S., Stavale J.N., Andrade J.A., Zielenska M., Squire J.A., de Toledo S.R. Metaphase and array comparative genomic hybridization: unique copy number changes and gene amplification of medulloblastomas in South America. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;170:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Totoki Y., Tatsuno K., Covington K.R., Ueda H., Creighton C.J., Kato M. Trans-ancestry mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma genomes. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1267–1273. doi: 10.1038/ng.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peifer M., Hertwig F., Roels F., Dreidax D., Gartlgruber M., Menon R. Telomerase activation by genomic rearrangements in high-risk neuroblastoma. Nature. 2015;526:700–704. doi: 10.1038/nature14980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis C.F., Ricketts C.J., Wang M., Yang L., Cherniack A.D., Shen H., Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network The somatic genomic landscape of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y., Wang S., Popova E.Y., Grigoryev S.A., Zhu J. Rearrangement of upstream sequences of the hTERT gene during cellular immortalization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:963–974. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castelo-Branco P., Choufani S., Mack S., Gallagher D., Zhang C., Lipman T., Zhukova N., Walker E.J., Martin D., Merino D., Wasserman J.D., Elizabeth C., Alon N., Zhang L., Hovestadt V., Kool M., Jones D.T., Zadeh G., Croul S., Hawkins C., Hitzler J., Wang J.C., Baruchel S., Dirks P.B., Malkin D., Pfister S., Taylor M.D., Weksberg R., Tabori U. Methylation of the TERT promoter and risk stratification of childhood brain tumours: an integrative genomic and molecular study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:534–542. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castelo-Branco P., Leao R., Lipman T., Campbell B., Lee D., Price A., Zhang C., Heidari A., Stephens D., Boerno S., Coelho H., Gomes A., Domingos C., Apolonio J.D., Schafer G., Bristow R.G., Schweiger M.R., Hamilton R., Zlotta A., Figueiredo A., Klocker H., Sultmann H., Tabori U. A cancer specific hypermethylation signature of the TERT promoter predicts biochemical relapse in prostate cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Oncotarget. 2016;7:57726–57736. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Vlodrop I.J., Niessen H.E., Derks S., Baldewijns M.M., van Criekinge W., Herman J.G., van Engeland M. Analysis of promoter CpG island hypermethylation in cancer: location, location, location! Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4225–4231. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y., Li G., He D., Yang F., He G., He L., Zhang H., Deng Y., Fan M., Shen L., Zhou D., Zhang Z. Telomerase reverse transcriptase methylation predicts lymph node metastasis and prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:279–286. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S97899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bougel S., Lhermitte B., Gallagher G., de Flaugergues J.C., Janzer R.C., Benhattar J. Methylation of the hTERT promoter: a novel cancer biomarker for leptomeningeal metastasis detection in cerebrospinal fluids. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2216–2223. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindsey J.C., Schwalbe E.C., Potluri S., Bailey S., Williamson D., Clifford S.C. TERT promoter mutation and aberrant hypermethylation are associated with elevated expression in medulloblastoma and characterise the majority of non-infant SHH subgroup tumours. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:307–309. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1225-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nomoto K., Maekawa M., Sugano K., Ushiama M., Fukayama N., Fujita S., Kakizoe T. Methylation status and expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase mRNA in relation to hypermethylation of the p16 gene in colorectal cancers as analyzed by bisulfite PCR-SSCP. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32:3–8. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyf001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gigek C.O., Leal M.F., Silva P.N., Lisboa L.C., Lima E.M., Calcagno D.Q., Assumpcao P.P., Burbano R.R., Smith Mde A. hTERT methylation and expression in gastric cancer. Biomarkers. 2009;14:630–636. doi: 10.3109/13547500903225912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Widschwendter A., Muller H.M., Hubalek M.M., Wiedemair A., Fiegl H., Goebel G., Mueller-Holzner E., Marth C., Widschwendter M. Methylation status and expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase in ovarian and cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Wilde J., Kooter J.M., Overmeer R.M., Claassen-Kramer D., Meijer C.J., Snijders P.J., Steenbergen R.D. hTERT promoter activity and CpG methylation in HPV-induced carcinogenesis. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:271. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renaud S., Loukinov D., Abdullaev Z., Guilleret I., Bosman F.T., Lobanenkov V., Benhattar J. Dual role of DNA methylation inside and outside of CTCF-binding regions in the transcriptional regulation of the telomerase hTERT gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1245–1256. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y., Sebra R., Pullman B.S., Qiao W., Peter I., Desnick R.J., Geyer C.R., DeCoteau J.F., Scott S.A. Quantitative and multiplexed DNA methylation analysis using long-read single-molecule real-time bisulfite sequencing (SMRT-BS) BMC Genomics. 2015;16:350. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan Y., Lee S., Wu G., Easton J., Yergeau D., Dummer R., Vogel P., Kirkwood J.M., Barnhill R.L., Pappo A., Bahrami A. Telomerase expression by aberrant methylation of the TERT promoter in melanoma arising in giant congenital nevi. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:339–342. doi: 10.1038/JID.2015.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brodeur G.M., Pritchard J., Berthold F., Carlsen N.L.T., Castel V., Castelberry R.P., De Bernardi B., Evans A.E., Favrot M., Hedborg F., Kaneko M., Kemshead J., Lampert F., Lee R.E.J., Look A.T., Pearson A.D.J., Philip T., Roald B., Sawada T., Seeger R.C., Tsuchida Y., Voute P.A. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1466–1477. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohn S.L., Pearson A.D., London W.B., Monclair T., Ambros P.F., Brodeur G.M., Faldum A., Hero B., Iehara T., Machin D., Mosseri V., Simon T., Garaventa A., Castel V., Matthay K.K. The International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) classification system: an INRG Task Force report. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:289–297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olsson M., Beck S., Kogner P., Martinsson T., Caren H. Genome-wide methylation profiling identifies novel methylated genes in neuroblastoma tumors. Epigenetics. 2016;11:74–84. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1138195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cobrinik D., Ostrovnaya I., Hassimi M., Tickoo S.K., Cheung I.Y., Cheung N.K. Recurrent pre-existing and acquired DNA copy number alterations, including focal TERT gains, in neuroblastoma central nervous system metastases. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:1150–1166. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fluhr S., Boerries M., Busch H., Symeonidi A., Witte T., Lipka D.B., Mucke O., Nollke P., Krombholz C.F., Niemeyer C.M., Plass C., Flotho C. CREBBP is a target of epigenetic, but not genetic, modification in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:50. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valentijn L.J., Koster J., Zwijnenburg D.A., Hasselt N.E., van Sluis P., Volckmann R., van Noesel M.M., George R.E., Tytgat G.A., Molenaar J.J., Versteeg R. TERT rearrangements are frequent in neuroblastoma and identify aggressive tumors. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1411–1414. doi: 10.1038/ng.3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryan T.M., Englezou A., Dalla-Pozza L., Dunham M.A., Reddel R.R. Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nat Med. 1997;3:1271–1274. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dessain S.K., Yu H., Reddel R.R., Beijersbergen R.L., Weinberg R.A. Methylation of the human telomerase gene CpG island. Cancer Res. 2000;60:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Devereux T.R., Horikawa I., Anna C.H., Annab L.A., Afshari C.A., Barrett J.C. DNA methylation analysis of the promoter region of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) gene. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6087–6090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruland V., Hartung S., Kordes U., Wolff J.E., Paulus W., Hasselblatt M. Methylation of the hTERT promoter is frequent in choroid plexus tumors but not of independent prognostic value. J Neurooncol. 2014;119:215–216. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Claus R., Wilop S., Hielscher T., Sonnet M., Dahl E., Galm O., Jost E., Plass C. A systematic comparison of quantitative high-resolution DNA methylation analysis and methylation-specific PCR. Epigenetics. 2012;7:772–780. doi: 10.4161/epi.20299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Draht M.X., Smits K.M., Jooste V., Tournier B., Vervoort M., Ramaekers C., Chapusot C., Weijenberg M.P., van Engeland M., Melotte V. Analysis of RET promoter CpG island methylation using methylation-specific PCR (MSP), pyrosequencing, and methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting (MS-HRM): impact on stage II colon cancer patient outcome. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:44. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0211-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guilleret I., Yan P., Grange F., Braunschweig R., Bosman F.T., Benhattar J. Hypermethylation of the human telomerase catalytic subunit (hTERT) gene correlates with telomerase activity. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:335–341. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nikolaidis G., Raji O.Y., Markopoulou S., Gosney J.R., Bryan J., Warburton C., Walshaw M., Sheard J., Field J.K., Liloglou T. DNA methylation biomarkers offer improved diagnostic efficiency in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5692–5701. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eads C.A., Danenberg K.D., Kawakami K., Saltz L.B., Blake C., Shibata D., Danenberg P.V., Laird P.W. MethyLight: a high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E32. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quillien V., Lavenu A., Karayan-Tapon L., Carpentier C., Labussiere M., Lesimple T., Chinot O., Wager M., Honnorat J., Saikali S., Fina F., Sanson M., Figarella-Branger D. Comparative assessment of 5 methods (methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction, MethyLight, pyrosequencing, methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting, and immunohistochemistry) to analyze O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltranferase in a series of 100 glioblastoma patients. Cancer. 2012;118:4201–4211. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deng J., Zhou D., Zhang J., Chen Y., Wang C., Liu Y., Zhao K. Aberrant methylation of the TERT promoter in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet. 2015;208:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao X., Tian X., Kajigaya S., Cantilena C.R., Strickland S., Savani B.N., Mohan S., Feng X., Keyvanfar K., Dunavin N., Townsley D.M., Dumitriu B., Battiwalla M., Rezvani K., Young N.S., Barrett A.J., Ito S. Epigenetic landscape of the TERT promoter: a potential biomarker for high risk AML/MDS. Br J Haematol. 2016;175:427–439. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detection of hypermethylated UTSS in varying relative amounts in bisulfite-treated unmethylated and methylated genomic DNA by COBRA. Commercially prepared methylation calibration standards of human genomic DNA (EpigenDx) were used to prepare the template for PCR amplification of the UTSS. The resultant products were digested with either BsiW1 (top panel) or Hyp188I (bottom panel). Identical blotches observed on a subset of gels are the result of residue present on the surface on which those gels were imaged. M, markers.

Summary of sequencing results of clones derived from the remaining NBL samples with hypermethylated UTSS. Open and closed circles indicate unmethylated and methylated CpG dinucleotides, respectively. CpG dinucleotides for which the methylation state was uninterpretable after sequencing are indicated by brown circles. N/A, not available.

Summary of sequencing results of clones derived from the remaining NBL samples with unmethylated UTSS. Open and closed circles indicate unmethylated and methylated CpG dinucleotides, respectively. N/A, not available.

COBRA showing short restriction fragments characteristic of hypermethylated UTSS in a clinically aggressive NBL sample that had been incorrectly classified as a low-risk tumor on the basis of the risk stratification criteria.

COBRA of the remaining NBL samples with unmethylated UTSS. Identical blotches observed on a subset of gels are the result of residue present on the surface on which those gels were imaged.