Abstract

Spitzoid neoplasms are a distinct group of melanocytic tumors. Genetically, they lack mutations in common melanoma-associated oncogenes. Recent studies have shown that spitzoid tumors may contain a variety of kinase fusions, including ROS1, NTRK1, ALK, BRAF, and RET fusions. We report herein the discovery of recurrent NTRK3 gene rearrangements in childhood melanocytic neoplasms with spitzoid and/or atypical features, based on genome-wide copy number analysis by single-nucleotide polymorphism array, which showed intragenic copy number changes in NTRK3. Break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed the presence of NTRK3 rearrangement, and a novel MYO5A-NTRK3 transcript, representing an in-frame fusion of MYO5A exon 32 to NTRK3 exon 12, was identified using a rapid amplification of cDNA ends–based anchored multiplex PCR assay followed by next-generation sequencing. The predicted MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion protein consists of several N-terminal coiled-coil protein dimerization motifs encoded by MYO5A and C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain encoded by NTRK3, which is consistent with the prototypical structure of TRK oncogenic fusions. Our study also demonstrates how array-based copy number analysis can be useful in discovering gene fusions associated with unbalanced genomic aberrations flanking the fusion points. Our findings add another potentially targetable kinase fusion to the list of oncogenic fusions in melanocytic tumors.

CME Accreditation Statement: This activity (“The JMD 2017 CME Program in Molecular Diagnostics”) has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) and the American Society for Investigative Pathology (ASIP). ASCP is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

The ASCP designates this journal-based CME activity (“The JMD 2017 CME Program in Molecular Diagnostics”) for a maximum of 36 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

CME Disclosures: The authors of this article and the planning committee members and staff have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose.

Spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms are a distinctive group of melanocytic tumors. In 1948, Sophie Spitz coined the term melanoma of childhood for a group of melanocytic skin tumors composed of spindled or epithelioid melanocytes that developed predominantly in children and adolescents.1 Most of these neoplasms behaved in an indolent manner, and they were subsequently termed Spitz nevus to indicate their benign nature. Malignant tumors with spitzoid histological features were termed spitzoid melanomas, and these tumors often showed aggressive clinical behavior with widespread metastasis, similar to conventional melanomas. Tumors with ambiguous histological features, overlapping between those of Spitz nevus and melanoma, are termed atypical Spitz tumors.2, 3

Most spitzoid neoplasms lack mutations in common melanoma-associated oncogenes, such as NRAS, KIT, GNAQ, or GNA11.4, 5 Recent studies have uncovered ROS1, NTRK1, ALK, RET, BRAF, and MET fusions in this group of tumors, suggesting that activation of kinase pathways plays an important role in their pathogenesis.5, 6, 7

In our clinical practice, we perform genome-wide high-resolution single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array analysis as an adjunct to the histopathological diagnosis for diagnostically challenging melanocytic tumors. Two hundred seven samples have been tested, most of which were diagnosed histologically as atypical Spitz tumors. In a previous study, we reported using array-based DNA copy number analysis to screen for gene fusions associated with unbalanced genomic aberrations flanking the fusion points and successfully identified KDR-PDGFRA fusion in a glioblastoma patient sample.8 This concept has informed our analysis of copy number profiles in the diagnostic setting, and intragenic copy number changes involving common receptor kinase genes are typically further analyzed and, if necessary, studied by alternative methods. Herein, we present the discovery of recurrent NTRK3 gene rearrangements and a novel MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion in childhood melanocytic neoplasms.

Materials and Methods

Study Samples

From January 2014 through December 2015, 207 melanocytic neoplasms with atypical, ambiguous, or controversial light microscopic features were submitted by a dermatopathologist (K.J.B.) for DNA copy number array analysis as part of the diagnostic assessment to the Clinical Cytogenetics and Cytogenomics Laboratory of the Department of Pathology. This study was conducted with the approval of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

DNA Copy Number Array Analysis

Tumor-rich areas were macrodissected from sections (10 μm thick) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues. Genomic DNA was extracted using Qiagen DNeasy Tissue and Blood kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Genome-wide DNA copy number alterations and allelic imbalances were analyzed by SNP-array using Affymetrix OncoScan FFPE Assay (Affymetrix, Santa, Clara, CA). We used 80 ng of genomic DNA for each sample. Processing of samples was performed according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Affymetrix). OncoScan SNP-array data were analyzed by the software couple of OncoScan Console version 1.0 (Affymetrix) and Nexus Express version 3.1 (BioDiscovery, El Segundo, CA) using Affymetrix TuScan algorithm. All array data were also manually reviewed for subtle alterations not automatically called by the software.

NTRK3 Break-Apart FISH Assay

FFPE tissue samples were tested for NTRK3 rearrangements by a break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay using a commercial NTRK3 break-apart FISH probe (Empire Genomics, Buffalo, NY). FFPE tissue sections (4 μm thick) generated from FFPE blocks of tumor specimens were pretreated by deparaffinizing in xylene and dehydrating in ethanol. Dual-color FISH assay was conducted according to the protocol for FFPE sections from Vysis/Abbott Molecular with a few modifications. FISH analysis and signal capture were conducted on a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) coupled with ISIS FISH Imaging System (Metasystems, Altlussheim, Germany). We analyzed 100 interphase nuclei from each tumor specimen.

Anchored Multiplex PCR for Targeted RNA-Sequencing

Tumor-rich areas were macrodissected from sections of FFPE tissues, and subjected to RNA extraction using Mineral Oil-Qiagen RNeasy FFPE kit (Qiagen). Random priming was used to synthesize cDNAs from the RNA samples extracted. An anchored multiplex PCR assay based on Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) strategy followed by next-generation sequencing (Archer FusionPlex, ArcherDX) was used to identify specific partners involved in selected gene fusions.9 We used a custom fusion-screening panel focusing on 35 genes, including NTRK3, known to be involved in recurrent gene fusions in several solid tumors. The list of genes in the panel is given in Supplemental Table S1. Within this panel, for NTRK3 fusions, 5′RACE was conducted using five pairs of NTRK3-specific 3′ primers targeting exons 13 to 16, and the multiplex RACE products were sequenced on MiSeq (Illumina), and sequencing data were analyzed by Archer Analysis software version 3.3.0 (ArcherDx).

Results

SNP-Array Study

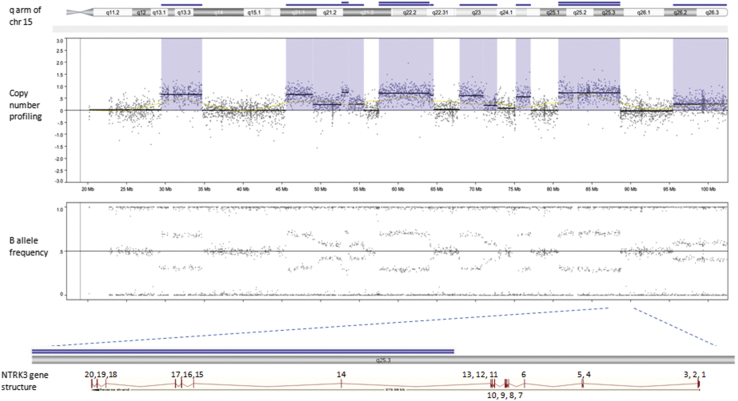

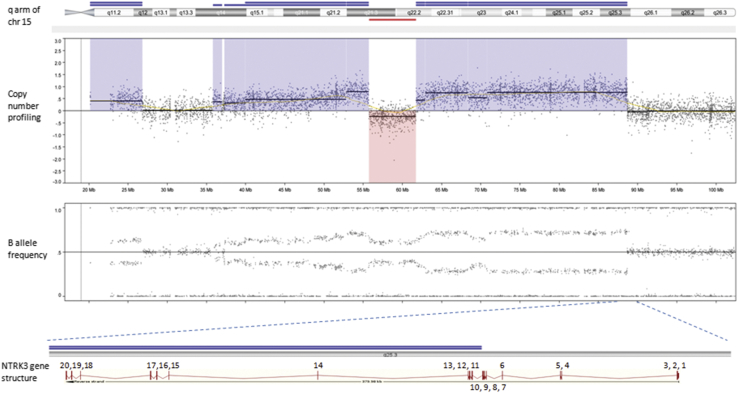

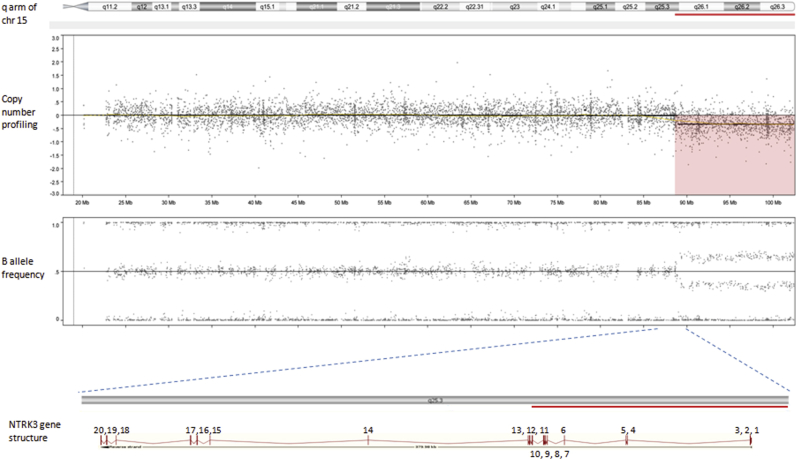

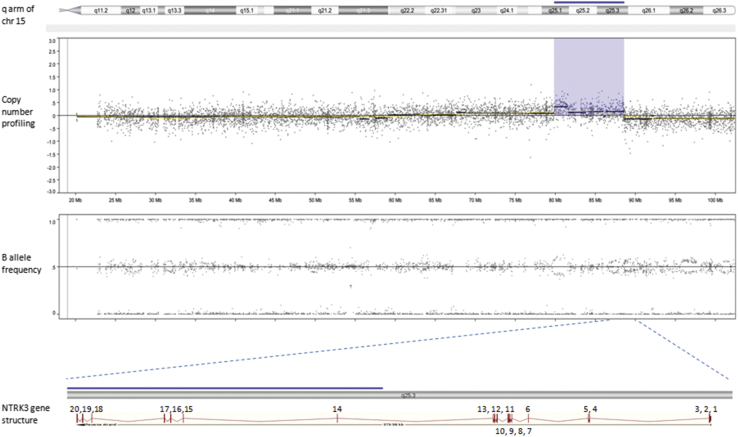

Based on genome-wide copy number profiling data of 207 melanocytic neoplasms analyzed by high-resolution SNP-array, we identified four tumors with intragenic copy number alteration of NTRK3 (reference transcript NM_001012338) at 15q25. NTRK3 encodes TRKC, a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase. The copy number plots of NTRK3 in the first case [709 (Figure 1)] and second case [930 (Figure 2)] showed a dramatic copy number increase of the 3′ portion of NTRK3, and no copy number change of the 5′ portion of NTRK3. The change point mapped to NTRK3 intron 13 in sample 709 and to the region between NTRK3 exons 10 and 12 in sample 930, respectively. An exon-level fine mapping of the breakpoint could not be achieved in 930 because of low probe coverage between exons 10 and 12. The copy number plot of NTRK3 in the other two cases (3509 and 4583) showed intragenic discontinuity with the change point mapped to NTRK3 exons 10 to 12 and intron 13, respectively. Case 3509 (Figure 3) is characterized by a copy number loss of the 5′ portion of NTRK3, and a copy number gain of 3′ NTRK3 was the notable finding in case 4583 (Figure 4). A summary of all intragenic copy number change points in NTRK3 identified by SNP-array analysis in this study is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 1.

Copy number and B allele frequency alterations across the q arm of chromosome (chr) 15 for case 709 revealed by SNP-array analysis (violet shadows highlight gains). A zoom-in view at NTRK3 gene locus illustrates the intragenic copy number change in NTRK3. Blue line indicates copy number gain and double blue line indicates high-level copy number gain (≥4 copies).

Figure 2.

Copy number and B allele frequency alterations across the q arm of chromosome (chr) 15 for case 930 revealed by SNP-array analysis (violet shadows and red shadows highlight gains and losses, respectively). A zoom-in view at NTRK3 gene locus illustrates the intragenic copy number change in NTRK3. Red line indicates copy number loss; blue line, copy number gain; and double blue line, high-level copy number gain (≥4 copies).

Figure 3.

Copy number and B allele frequency alterations across the q arm of chromosome (chr) 15 for case 3509 revealed by SNP-array analysis (the red shadow highlights a copy number loss). A zoom-in view at NTRK3 gene locus illustrates the intragenic copy number change in NTRK3. Red line indicates copy number loss.

Figure 4.

Copy number and B allele frequency alterations across the q arm of chromosome (chr) 15 for case 4583 revealed by SNP-array analysis (the violet shadow highlights a copy number gain). A zoom-in view at NTRK3 gene locus illustrates the intragenic copy number change in NTRK3. Blue line indicates copy number gain.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of NTRK3 gene structure (reference sequence: NM_001012338) with green diamond arrows indicating the intragenic copy number change point in each sample. From left to right: 930, 3509, 709, and 4583. NTRK3 kinase domain coding exons are 15 to 20.

Besides the aberrations leading to intragenic copy number change of NTRK3, genome-wide SNP-array analysis also revealed other copy number changes elsewhere in the genome in each sample (Supplemental Figures S1–S4) (ie, multiple segmental gains in 15q and in chromosome 20 in sample 709; multiple segmental gains in 15q, and copy number change at 14q32 in sample 930; gain of 1q in sample 3509; and 6q deletion and complex copy number changes across 11q in sample 4583). The SNP-array data discussed in this publication have been deposited in National Center for Biotechnology Information's Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; accession number GSE90644).10

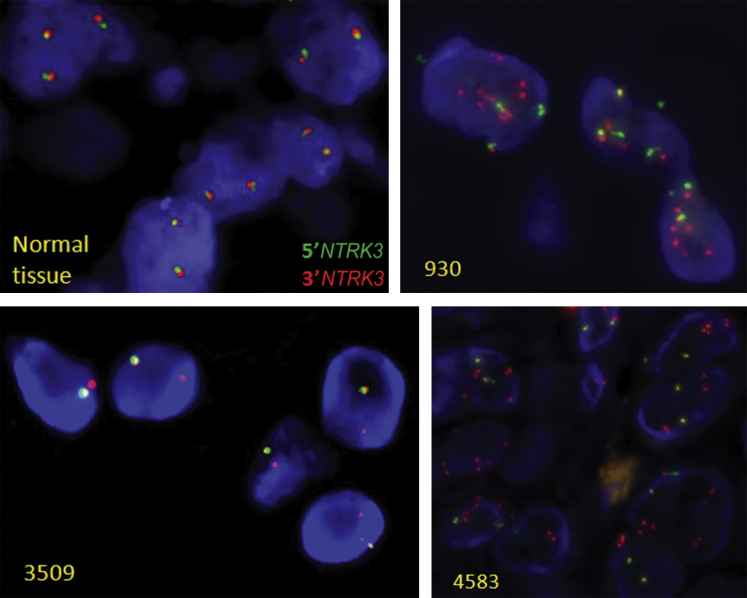

Verification of NTRK3 Gene Rearrangement by FISH Analysis

NTRK3 break-apart FISH was performed on three tumor samples (930, 3509, and 4583) with NTRK3 intragenic copy number alterations. Sample 709 has insufficient tumor tissue for FISH study. In sample 930, FISH detected one 3′/5′ fusion signal plus six to eight signals for 3′NTRK3 and one single signal for 5′NTRK3. A similar signal pattern was observed in sample 4583. Because of the lower tumor content in sample 4583 compared to sample 930, SNP-array analysis showed a lesser copy number increase of the 3′ portion of NTRK3 in 4583 compared to the dramatic copy number increase (>6 copies) of the 3′ portion of NTRK3 in 930. FISH supported the loss of 5′NTRK3 in sample 3509 by showing one 3′/5′ fusion signal and one single 3′ NTRK3 signal. FISH analysis confirmed the SNP-array findings and further supported the presence of NTRK3 fusions in the three tumor samples. Representative FISH images of all three samples are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Interphase fluorescent in situ hybridization detection of NTRK3 gene rearrangement. Green signals represent 5′NTRK3; and red signals, 3′NTRK3. In comparison to the 5′/3′-fusion signals seen in normal cells, multiple signals for 3′NTRK3 and one separated signal for 5′NTRK3 were observed in samples 930 and 4583; and a single 3′NTRK3 signal pattern (loss of the signal for 5′NTRK3) was observed in sample 3509. Original magnification, ×63.

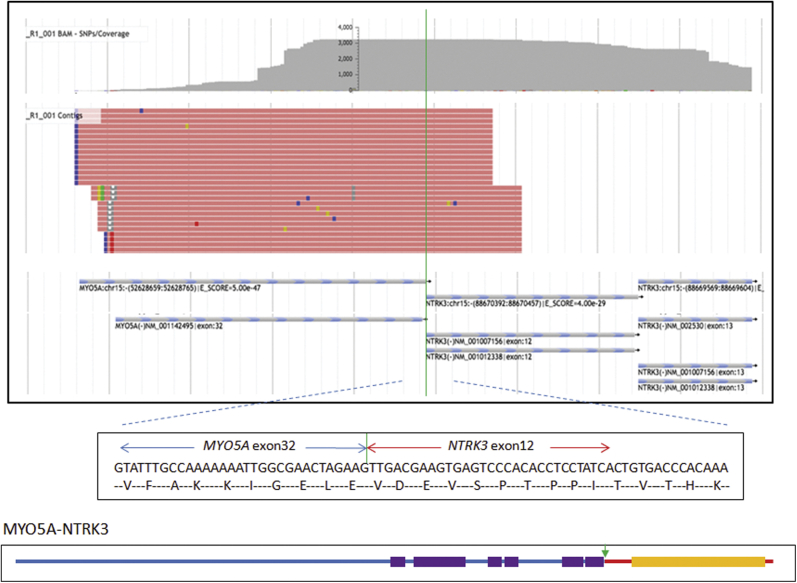

Identification of a Novel Fusion Transcript, MYO5A-NTRK3, in a Spitz Nevus

To identify the 5′ fusion partners of NTRK3, we used the anchored multiplex PCR platform for targeted RNA-sequencing (seq) (Archer FusionPlex). Using this platform, we successfully identified a novel fusion transcript in sample 930, MYO5A-NTRK3. The novel MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion showed MYO5A (NM_001142495) exon 32 fused in-frame to NTRK3 (NM_001012338) exon 12 (Figure 7), and expressed in high abundance in the tumor sample 930, according to the targeted RNA-seq data. In brief, after the deduplication of high-quality raw sequences, >66,000 on-target RNA-originated sequences were obtained, which represented 4516 unique cDNA molecules (unique start sites). Among these unique reads, approximately 25% are from NTRK3 transcripts. In contrast, the number of reads representing transcripts from each of the other 34 genes in the panel was much lower (0% to 4% per gene), and no fusion transcript involving the 34 genes was identified according to our data analysis pipeline. In terms of NTRK3 transcripts, 16% of the reads are bona fide MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion reads spanning the fusion points. For X-NTRK3 (X represents any 5′ partner) fusion screening, we have five pairs of NTRK3-specific 3′ primers, targeting from exon 13 to exon 16, for 5′RACE procedure to uncover 5′ fusion partners of NTRK3. Considering the degradation of RNA that occurs because of the formalin fixation process results in RNA species with an average size of approximately 200 nucloetides,11 only the primers that are close to the fusion point are efficacious in the 5′RACE procedure to pull out the 5′ fusion partner. In fact, all MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion reads identified in sample 930 were derived from primers targeting NTRK3 exon 13. In other words, many other NTRK3 transcript reads, if not all, may be from the MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion product; however, they were not informative in unveiling the novel gene fusion because of the degradation of FFPE RNA. In summary, our targeted RNA-seq data provided strong evidence that MYO5A-NTRK3 was the sole kinase fusion and expressed in high abundance in case 930.

Figure 7.

Identification of the novel MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion in the spitzoid tumor sample 930. Top panel: A representative image of MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion visualization by Archer JBrowse software version 3.3.0. Middle panel: Partial sequence of the MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion transcript along with predicted amino acid sequence. The transcript is an in-frame fusion of MYO5A exon 32 to NTRK3 exon 12. Bottom panel: Schematic diagram of the predicted MYO5A-NTRK3 chimeric protein. Blue line indicates N-terminal of MYO5A; red line, C-terminal of NTRK3; purple bars, coiled-coil dimerization domains of MYO5A; orange bar, the kinase domain of NTRK3; vertical green lines in top and middle panels and the green arrow in bottom panel, the fusion point.

MYO5A and NTRK3 are approximately 36 Mb apart on genomic DNA, respectively mapping to 15q21.2 and 15q25.3, and both are on the reverse strand of chromosome 15. In sample 930, complex copy number changes across 15q were detected by SNP-array analysis (Figure 2), including multiple segmental copy number gains (from three to six copies) and a segmental deletion. One copy gain segment overlapped the entire MYO5A gene, with no intragenic copy number change observed. Therefore, the MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion may result from some complex genomic rearrangement in this sample. No evidence of intragenic copy number change of MYO5A gene was observed in the other cases. Whether MYO5A is the recurrent fusion partner could not be verified because of the unavailability of material of cases 709, 3509, and 4583 for RNA extraction and the targeted RNA-seq study.

The predicted MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion protein consist of several N-terminal coiled-coil protein dimerization motifs from MYO5A and C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain provided by NTRK3, which is consistent with the fusion structure typically demonstrated in NTRK (NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3) oncogenic fusions.12 Figure 7 shows the schematic diagram of the predicted MYO5A-NTRK3 chimeric protein.

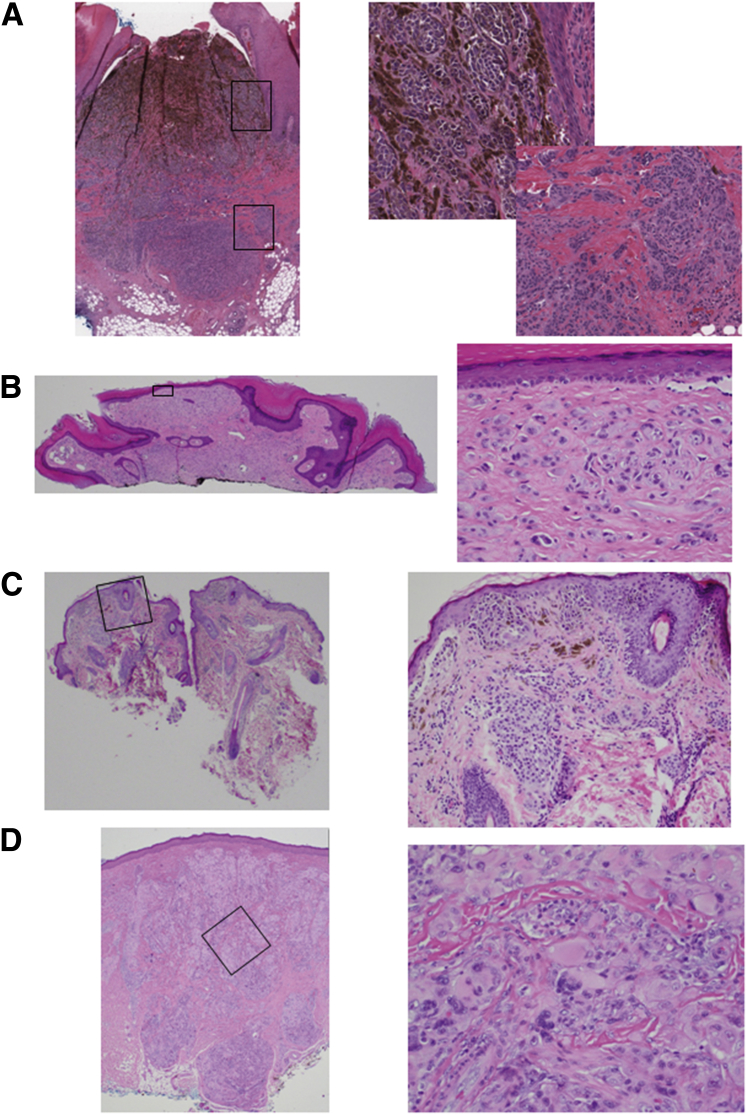

Clinical and Histopathological Features of NTRK3-Rearranged Melanocytic Tumors

The four tumor samples with evidence of NTRK3 fusion were from four children, including three girls (1, 7, and 15 years old) and one 8-year-old boy. Two lesions (3509 and 4583) were from the cheek, and two (709 and 930) were from the foot. Three lesions had spitzoid cytologic features (ie, 930 and 3509 were interpreted as Spitz nevi, whereas 4583 was designated as spitzoid melanoma of childhood because of nuclear pleomorphism and additional cytogenetic aberrations, including loss of the q arm of chromosome 6 and segmental gains and losses across 11q). The remaining one lesion (709) was an acral nevus in a one-year-old child with unusual features. The tumor displayed a congenital nevus pattern and contained a subpopulation of heavily pigmented epithelioid melanocytes. Accordingly, the histopathological findings of the four tumors were variable. Two lesions were entirely composed of amelanotic large epithelioid cells (Figure 8, B and D); the other two lesions contained a mixed population of pigmented large melanocytes superficially and amelanotic epithelioid melanocytes in the deeper portion of the lesion (Figure 8, A and C).

Figure 8.

Light microscopic findings of four NTRK3-rearrangement melanocytic tumors. Sample 709 (A), 930 (B), 3509 (C), and 4583 (D). A–D: Left panels: Low-magnification images. Right panels: High-magnification images showing boxed areas of detail. A: Pandermal acral epithelioid melanocytic tumor with heavy pigmentation in its superficial portion. Top right panel: Superficial pigmented epithelioid cell component. Bottom right panel: Deep dermal amelanotic spindle and epithelioid cell proliferation. B: Polypoid silhouette of a predominantly intradermal amelanotic pauci-cellular melanocytic nevus; the intradermal melanocytes are predominantly epithelioid in appearance. C: Compound melanocytic nevus, the tumor cells are epithelioid in appearance; a few melanophages are present. D: Spitzoid melanoma of childhood, large atypical compound melanocytic tumor with extension into subcutis, the tumor cells are amelanotic, epithelioid in appearance, and display nuclear pleomorphism. Original magnifications: ×2 (A–D, left panels); ×20 (A–D, right panels).

Discussion

We report herein the evidence for recurrent NTRK3 gene fusions in four childhood melanocytic tumors based on genome-wide copy number analysis by SNP-array. In addition, in one case of which sufficient material was available for RNA extraction, a novel MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion was identified by targeted RNA-seq. The approach used in the current study builds on our previous studies,8 which had shown that high-resolution copy number array analysis can be used to screen for gene fusions associated with unbalanced genomic aberrations flanking the fusion points without prior knowledge of the genetics of a given case. In addition to the identification of NTRK3 fusions, we also detected samples with ALK, BRAF, and NTRK1 gene rearrangements that have known to be associated with recurrent gene fusions in spitzoid tumors. FISH assays were performed on each case, when tumor material was available, and verified the prediction based on the SNP-array findings (data not shown).

In a recent study, Wiesner et al6 used a high-throughput next-generation sequencing approach to analyze 140 spitzoid tumors, and demonstrated that recurrent kinase fusions involving ROS1, NTRK1, ALK, BRAF, and RET are common genetic aberrations in spitzoid neoplasms, and these aberrations present in a mutually exclusive pattern. And, more recently, Yeh et al7 reported MET fusions in a rare subtype of spitzoid tumor. All these kinase genes, except MET, are included in our custom fusion-screening panel designed for anchored multiplex PCR for targeted RNA-seq. This fusion-screening strategy enables the identification of both known and novel fusions involving genes in the panel. Using the screening platform, we discovered a MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion in sample 930. Besides the strong evidence from the target RNA-seq showing the bona fide MYO5A-NTRK3 transcript, MYO5A-NTRK3 is the only fusion transcript identified in this sample, which suggests that NTRK3 fusion is mutually exclusive with other kinase fusions in spitzoid tumors. Given that MET was not included in our fusion-screening panel, we could not obtain data from the targeted RNA-seq to verify if NTRK3 and MET fusions are mutually exclusive. All MET-fusion cases reported by Yeh et al7 were associated with unbalanced structural abnormalities at or near MET gene locus by array analysis. However, this phenomenon was not observed in any of our NTRK3-rearranged cases by high-resolution copy number analysis. Therefore, it is likely that NTRK3 and MET fusions in melanocytic tumors follow the mutually exclusive pattern as well.

The NTRK3 gene encodes TRKC, a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase, which is primarily involved in neuronal cellular processes.13 TRKC is a member of the tropomyosin-receptor kinase (TRK) family that also includes TRKA (encoded by NTRK1) and TRKB (encoded by NTRK2). NTRK1/2/3 oncogenic gene fusions have been identified in several tumor types to date.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 The first NTRK3 gene fusion, ETV6-NTRK3, was described in congenital fibrosarcoma in 1998.19 Since then, ETV6-NTRK3 rearrangements have been identified in several other tumor types, including congenital mesoblastic nephroma,20 secretory breast carcinoma,21 acute myeloid leukemia,22 mammary analog secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland,23 radiation-associated thyroid cancer,24 and colorectal cancer.26 In contrast to NTRK1 and NTRK2 fusions in which a variety of 5′ fusion partners have been identified, almost all NTRK3 gene fusions reported so far are ETV6-NTRK3 regardless of the tumor type, and only a few other fusion partners have been identified in individual cases.

In most of the NTRK fusions identified so far, the 5′ fusion partner provides a portion encoding one or more dimerization domains and 3′ portion of NTRK encoding the kinase domain is always preserved in the fusion gene. Several functional studies have shown that chimeric TRK proteins are constitutively active tyrosine kinases and oncogenic. For instance, Wai et al29 expressed a serial of ETV6-NTRK3 constructions in NIH3T3 cells and demonstrated that the protein product of ETV6-NTRK3 functions as a chimeric protein tyrosine kinase that is autophosphorylated on tyrosine residues and has transforming activity. Both an intact dimerization domain and a functional protein tyrosine kinase domain are required for its transforming activity. Further on, Tognon et al30 illustrated that the expression of ETV6-NTRK3 in NIH3T3 cells leads to constitutive activation of two effector pathways of wild-type NTRK3 (ie, the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–AKT pathway), and mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–AKT activations act synergistically to mediate ETV6-NTRK3 transforming activity. As ETV6-NTRK3 fusion is fairly dominant in secretory breast cancer, Tognon et al21 also demonstrated the transforming activity of ETV6-NTRK3 in mammary epithelial cells. Similarly, several studies reported oncogenic activity of NTRK1 fusions with different 5′ fusion partners.16, 17 Given that chimeric TRK proteins are constitutively active tyrosine kinases and oncogenic, clinical trials to evaluate the benefit of pan-TRK inhibitors in patients with NTRK fusions are ongoing.31, 32 We recently reported the first clinical response to TRKC inhibition in a patient with an NTRK3-rearranged malignancy, underlining the role of NTRK3 fusions as targetable drivers of oncogenesis.33

In our study, the predicted MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion protein consists of several N-terminal coiled-coil protein dimerization motifs encoded by MYO5A and C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain encoded by NTRK3, which perfectly fits the TRK oncogenic fusion paradigm and suggests it may function as a chimeric protein tyrosine kinase with potent transforming activity (Figure 7). Although MYO5A is a novel fusion partner for NTRK3, a MYO5A-ROS1 fusion was identified in the Wiesner study of spitzoid tumors.6 MYO5A is one of three myosin V heavy-chain genes, belonging to the myosin gene superfamily. Myosin V is a class of actin-based motor proteins involved in cytoplasmic vesicle transport and anchorage, spindle-pole alignment, and mRNA translocation. The expression of MYO5A is abundant in melanocytes and nerve cells.34 Hence, we hypothesize that MYO5A, as a recurrent fusion partner involved in kinase gene fusions in spitzoid tumor, may facilitate the oncogenic activity of the fusion products not only by providing the coiled-coil dimerization domain but also by its strong promoter to up-regulate the expression of the fusion transcript. As shown by the targeted RNA-seq, the MYO5A-NTRK3 fusion transcripts expressed in high abundance in tumor sample 930, which is consistent with our hypothesis. Unfortunately, the expression of NTRK3 chimeric protein could not be evaluated by immunohistochemical staining on the FFPE tumor tissues in the present study because of the unavailability of a reliable antibody. Future studies will continue to characterize NTRK3 fusion(s) in childhood melanocytic neoplasms and determine whether NTRK3 fusions contribute to the initiation and/or maintenance of the fusion-positive childhood melanocytic neoplasms.

In summary, we report herein the identification of a novel NTRK3 gene fusion in childhood melanocytic tumors based on genome-wide copy number analysis by SNP-array. Because the prevalence and pattern of DNA copy number changes differ dramatically between benign and malignant melanocytic tumors, DNA copy number analysis by array-based studies has been used as an important ancillary method for diagnostic evaluation of melanocytic proliferations with ambiguous histopathological findings.35, 36, 37 As such, we suggest that intragenic copy number changes, in particular when genes affected are known to be involved in recurrent gene fusions in human tumors, should be closely reviewed and further evaluated (if needed) to confirm potential gene fusions that may be rational drug targets.

Our findings add to the list of kinase fusions that have so far been found in melanocytic tumors. NTRK3 fusion may define an additional subset of melanocytic tumors with a potentially targetable driver oncogene. Among the four examined lesions, three lesions had spitzoid cytologic features, whereas one was not believed to belong into the group of Spitz tumors. Thus, our findings suggest that, although kinase activation by receptor-kinase–gene fusions is a common mechanism that drives tumorigenesis in spitzoid neoplasms, kinase fusions could be found in childhood melanocytic neoplasms outside of the spectrum of Spitz tumors. With regard to the significance of NTRK3 fusions in Spitz tumors, as previously documented with other kinase fusions,5 kinase fusions can be found in the full spectrum of spitzoid neoplasms ranging from lesions classified as nevi to lesions designated as spitzoid melanoma of childhood. The clinical significance of NTRK3 fusions in childhood melanocytic tumors will be determined on following up on the clinical outcomes of patients bearing the fusions.

Footnotes

Supported by the Department of Pathology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Internal Research Fund and in part by the NIH/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support grant under award P30CA008748.

Disclosures: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.11.005.

Supplemental Data

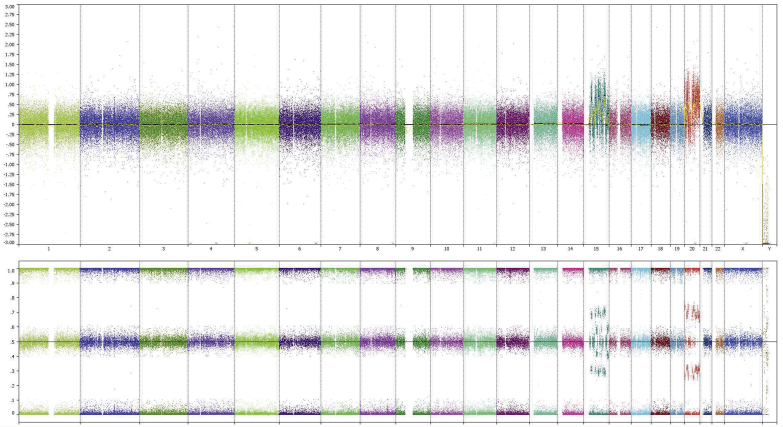

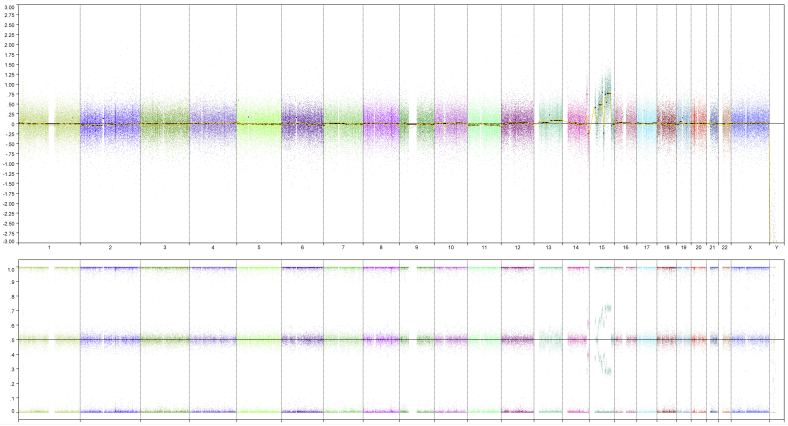

Supplemental Figure S1.

Genome-wide copy number plot revealed by SNP-array analysis: case 709. Top panel: Copy number changes. Bottom panel: B allele frequency. Each column stands for one chromosome, and from left to right are chromosome 1 to 22, X, and Y, in order.

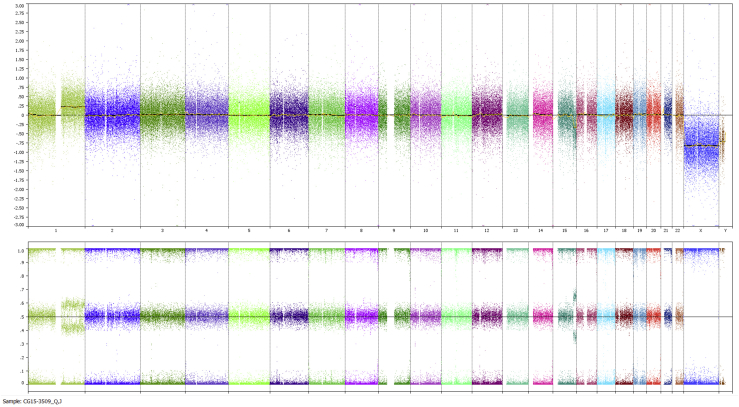

Supplemental Figure S2.

Genome-wide copy number plot revealed by SNP-array analysis: case 930. Top panel: Copy number changes. Bottom panel: B allele frequency. Each column stands for one chromosome, and from left to right are chromosome 1 to 22, X, and Y, in order.

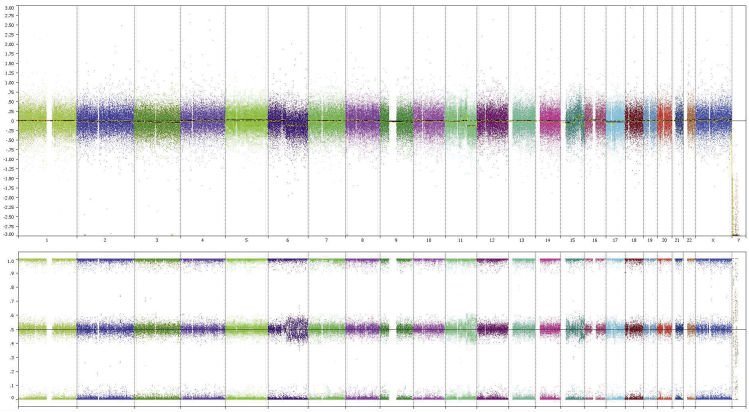

Supplemental Figure S3.

Genome-wide copy number plot revealed by SNP-array analysis: case 3509. Top panel: Copy number changes. Bottom panel: B allele frequency. Each column stands for one chromosome, and from left to right are chromosome 1 to 22, X, and Y, in order.

Supplemental Figure S4.

Genome-wide copy number plot revealed by SNP-array analysis: case 4583. Top panel: Copy number changes. Bottom panel: B allele frequency. Each column stands for one chromosome, and from left to right are chromosome 1 to 22, X, and Y, in order.

References

- 1.Spitz S. Melanomas of childhood. Am J Pathol. 1948;24:591–609. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murali R., Sharma R.N., Thompson J.F., Stretch J.R., Lee C.S., McCarthy S.W., Scolyer R.A. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in histologically ambiguous melanocytic tumors with spitzoid features (so-called atypical spitzoid tumors) Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:302–309. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9577-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludgate M.W., Fullen D.R., Lee J., Lowe L., Bradford C., Geiger J., Schwartz J., Johnson T.M. The atypical Spitz tumor of uncertain biologic potential: a series of 67 patients from a single institution. Cancer. 2009;115:631–641. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu C., Zhang J., Nagahawatte P., Easton J., Lee S., Liu Z., Ding L., Wyczalkowski M.A., Valentine M., Navid F., Mulder H., Tatevossian R.G., Dalton J., Davenport J., Yin Z., Edmonson M., Rusch M., Wu G., Li Y., Parker M., Hedlund E., Shurtleff S., Raimondi S., Bhavin V., Donald Y., Mardis E.R., Wilson R.K., Evans W.E., Ellison D.W., Pounds S., Dyer M., Downing J.R., Pappo A., Bahrami A. The genomic landscape of childhood and adolescent melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:816–823. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S., Barnhill R.L., Dummer R., Dalton J., Wu J., Pappo A., Bahrami A. TERT promoter mutations are predictive of aggressive clinical behavior in patients with spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11200. doi: 10.1038/srep11200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiesner T., He J., Yelensky R., Esteve-Puig R., Botton T., Yeh I., Lipson D., Otto G., Brennan K., Murali R., Garrido M., Miller V.A., Ross J.S., Berger M.F., Sparatta A., Palmedo G., Cerroni L., Busam K.J., Kutzner H., Cronin M.T., Stephens P.J., Bastian B.C. Kinase fusions are frequent in Spitz tumours and spitzoid melanomas. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3116. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeh I., Botton T., Talevich E., Shain A.H., Sparatta A.J., de la Fouchardiere A., Mully T.W., North J.P., Garrido M.C., Gagnon A., Vemula S.S., McCalmont T.H., LeBoit P.E., Bastian B.C. Activating MET kinase rearrangements in melanoma and Spitz tumours. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7174. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozawa T., Brennan C.W., Wang L., Squatrito M., Sasayama T., Nakada M., Huse J.T., Pedraza A., Utsuki S., Yasui Y., Tandon A., Fomchenko E.I., Oka H., Levine R.L., Fujii K., Ladanyi M., Holland E.C. PDGFRA gene rearrangements are frequent genetic events in PDGFRA-amplified glioblastomas. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2205–2218. doi: 10.1101/gad.1972310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Z., Liebers M., Zhelyazkova B., Cao Y., Panditi D., Lynch K.D., Chen J., Robinson H.E., Shim H.S., Chmielecki J., Pao W., Engelman J.A., Iafrate A.J., Le L.P. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med. 2014;20:1479–1484. doi: 10.1038/nm.3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A.E. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masuda N., Ohnishi T., Kawamoto S., Monden M., Okubo K. Analysis of chemical modification of RNA from formalin-fixed samples and optimization of molecular biology applications for such samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4436–4443. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaishnavi A., Le A.T., Doebele R.C. TRKing down an old oncogene in a new era of targeted therapy. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:25–34. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao M.V. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin-Zanca D., Hughes S.H., Barbacid M. A human oncogene formed by the fusion of truncated tropomyosin and protein tyrosine kinase sequences. Nature. 1986;319:743–748. doi: 10.1038/319743a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greco A., Miranda C., Pierotti M.A. Rearrangements of NTRK1 gene in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;321:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaishnavi A., Capelletti M., Le A.T., Kako S., Butaney M., Ercan D., Mahale S., Davies K.D., Aisner D.L., Pilling A.B., Berge E.M., Kim J., Sasaki H., Park S.I., Kryukov G., Garraway L.A., Hammerman P.S., Haas J., Andrews S.W., Lipson D., Stephens P.J., Miller V.A., Varella-Garcia M., Jänne P.A., Doebele R.C. Oncogenic and drug-sensitive NTRK1 rearrangements in lung cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:1469–1472. doi: 10.1038/nm.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J., Lee Y., Cho H.J., Lee Y.E., An J., Cho G.H., Ko Y.H., Joo K.M., Nam D.H. NTRK1 fusion in glioblastoma multiforme. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Créancier L., Vandenberghe I., Gomes B., Dejean C., Blanchet J.C., Meilleroux J., Guimbaud R., Selves J., Kruczynski A. Chromosomal rearrangements involving the NTRK1 gene in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;365:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knezevich S.R., McFadden D.E., Tao W., Lim J.F., Sorensen P.H. A novel ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in congenital fibrosarcoma. Nat Genet. 1998;18:184–187. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin B.P., Chen C.J., Morgan T.W., Xiao S., Grier H.E., Kozakewich H.P., Perez-Atayde A.R., Fletcher J.A. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma t(12;15) is associated with ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion: cytogenetic and molecular relationship to congenital(infantile) fibrosarcoma. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65732-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tognon C., Knezevich S.R., Huntsman D., Roskelley C.D., Melnyk N., Mathers J.A., Becker L., Carneiro F., MacPherson N., Horsman D., Poremba C., Sorensen P.H. Expression of the ETV6–NTRK3 gene fusion as a primary event in human secretory breast carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kralik J.M., Kranewitter W., Boesmueller H., Marschon R., Tschurtschenthaler G., Rumpold H., Wiesinger K., Erdel M., Petzer A.L., Webersinke G. Characterization of a newly identified ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcript in acute myeloid leukemia. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop J.A., Yonescu R., Batista D., Begum S., Eisele D.W., Westra W.H. Utility of mammaglobin immunohistochemistry as a proxy marker for the ETV6-NTRK3 translocation in the diagnosis of salivary mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1982–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leeman-Neill R.J., Kelly L.M., Liu P., Brenner A.V., Little M.P., Bogdanova T.I., Evdokimova V.N., Hatch M., Zurnadzy L.Y., Nikiforova M.N., Yue N.J., Zhang M., Mabuchi K., Tronko M.D., Nikiforov Y.E. ETV6-NTRK3 is a common chromosomal rearrangement in radiation-associated thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:799–807. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts K.G., Li Y., Payne-Turner D., Harvey R.C., Yang Y.L., Pei D. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hechtman J.F., Zehir A., Yaeger R., Wang L., Middha S., Zheng T., Hyman D.M., Solit D., Arcila M.E., Borsu L., Shia J., Vakiani E., Saltz L., Ladanyi M. Identification of targetable kinase alterations in patients with colorectal carcinoma that are preferentially associated with wild-type RAS/RAF. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14:296–301. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0392-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones D.T., Hutter B., Jäger N., Korshunov A., Kool M., Warnatz H.J., International Cancer Genome Consortium PedBrain Tumor Project Recurrent somatic alterations of FGFR1 and NTRK2 in pilocytic astrocytoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:927–932. doi: 10.1038/ng.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu G., Diaz A.K., Paugh B.S., Rankin S.L., Ju B., Li Y., St. Jude Children's Research Hospital–Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:444–450. doi: 10.1038/ng.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wai D.H., Knezevich S.R., Lucas T., Jansen B., Kay R.J., Sorensen P.H. The ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion encodes a chimeric protein tyrosine kinase that transforms NIH3T3 cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:906–915. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tognon C., Garnett M., Kenward E., Kay R., Morrison K., Sorensen P.H. The chimeric protein tyrosine kinase ETV6-NTRK3 requires both Ras-Erk1/2 and PI3-kinase-Akt signaling for fibroblast transformation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8909–8916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doebele R.C., Davis L.E., Vaishnavi A., Le A.T., Estrada-Bernal A., Keysar S., Jimeno A., Varella-Garcia M., Aisner D.L., Li Y., Stephens P.J., Morosini D., Tuch B.B., Fernandes M., Nanda N., Low J.A. An oncogenic NTRK fusion in a patient with soft-tissue sarcoma with response to the tropomyosin-related kinase inhibitor LOXO-101. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1049–1057. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.TRK inhibitor shows early promise. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:OF4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-NB2015-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drilon A., Li G., Dogan S., Gounder M., Shen R., Arcila M., Wang L., Hyman D.M., Hechtman J., Wei G., Cam N.R., Christiansen J., Luo D., Maneval E.C., Bauer T., Patel M., Liu S.V., Ou S.H., Farago A., Shaw A., Shoemaker R.F., Lim J., Hornby Z., Multani P., Ladanyi M., Berger M., Katabi N., Ghossein R., Ho A.L. What hides behind the MASC: clinical response and acquired resistance to entrectinib after ETV6-NTRK3 identification in a mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) Ann Oncol. 2016;27:920–926. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desnos C., Huet S., Darchen F. “Should I stay or should I go?”: myosin V function in organelle trafficking. Biol Cell. 2007;99:411–423. doi: 10.1042/BC20070021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtin J.A., Fridlyand J., Kageshita T., Patel H.N., Busam K.J., Kutzner H., Cho K.H., Aiba S., Bröcker E.B., LeBoit P.E., Pinkel D., Bastian B.C. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer J., Bastian B.C. Distinguishing melanocytic nevi from melanoma by DNA copy number changes: comparative genomic hybridization as a research and diagnostic tool. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L., Rao M., Fang Y., Hameed M., Viale A., Busam K., Jhanwar S.C. A genome-wide high-resolution array-CGH analysis of cutaneous melanoma and comparison of array-CGH to FISH in diagnostic evaluation. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.