Abstract

Incorporation of patient values is a key element of patient-centered care, but consistent incorporation of patient values at the point of care is lacking. Shared decision making encourages incorporation of patient values in decision making, but associated tools often lack guidance on value assessment. Additionally, focusing on patient values relating only to specific decisions misses an opportunity for a more holistic approach to value assessment which could impact other aspects of clinical encounters, including health care planning, communication, and stakeholder involvement. In this commentary, we propose a taxonomy of values underlying patient decision-making and provide examples of how these impact provision of healthcare. The taxonomy describes four categories of patient values: global, decisional, situational, and external. Global values are personal values impacting decision-making at a universal level and can include value traits and life priorities. Decisional values are the values traditionally conceptualized in decision making, including considerations such as efficacy, toxicity, quality of life, convenience, and cost. Situational values are values tied to a specific moment in time that modify patients’ existing global and decisional values. Finally, discussion of external values acknowledges that many patients consider values other than their own when making decisions. Recognizing the breadth of values impacting patient decision making has implications for both for overall healthcare delivery and for shared decision making, as value assessments focusing only on decisional values may miss important patient considerations. This draft taxonomy highlights different values impacting decision-making and facilitates a more complete value assessment at the point of care.

MeSH term: Value, shared decision making, taxonomy, decision making

Background

Patient-centered care is partly defined by responsiveness to patient values, where patient values “refers to the unique preferences, concerns, and expectations that are brought by each patient to a clinical encounter and must be integrated into clinical decisions if the patient is to be served” [1]. “Value” here is distinct from the term’s use in health economics, where value relates to quality and cost [2]. Fifteen years have passed since the landmark Institute of Medicine publication promoting patient-centered care [1], but consistent incorporation of patient values at the point of care remains lacking. Only 47% of U.S. adults report that clinicians consider their goals and concerns [3].

When patient values are incorporated within clinical encounters, it typically occurs in the context of shared decision making (SDM), “the pinnacle of patient-centered care” [4]. SDM is a patient-clinician collaboration incorporating patients’ values and preferences alongside best available evidence to make a healthcare decision. SDM descriptions focus on how clinicians provide evidence to patients and allowing patients to incorporate values when making decisions [5]. SDM models describe helping patients understand that options exist, providing details about the options, and supporting patients in considering values when making a decision [6]. There is little discussion regarding the role of value assessment in SDM, however.

Decision aids (DAs) are one approach to value assessment within SDM. DAs are structured approaches guiding clinicians and patients through information about a decision and helping patients understand personal values. The International Patient Decision Aid Standards instrument (IPDASi) checklist includes clarifying values as one key component of DAs, requiring that DAs help patients imagine experiencing the physical, psychological, and social effects of different options and consider which positive and negative features of the choice matter most [7]. While DAs can help patients gain clarity about values and lead to decisions that are more in line with their values [8, 9], only 55% of DAs include value clarification exercises [8].

Furthermore, DA value assessments often take a narrow view of patient values, focusing purely on preferences relating to positive and negative outcomes of the choice. A review of DA value clarification methods found that listing the pros and cons of a decision was the most common method used [10]. Additionally, DAs including value clarification incorporate this after the discussion of options and evidence and thus have no mechanism for individualizing the presentation of potential risks and benefits to patients’ values. This is also true of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s SHARE approach to SDM, where assessing a patient’s values is step 3 of 5, occurring only after engaging the patient and helping him explore and compare treatment options [11]. While increasing research supports DAs as helpful tools for improving informed decision-making [9, 12], these tools used in isolation miss the opportunity for a more holistic approach to value assessment.

Value-focused thinking

Systems management makes a useful distinction between “value-focused thinking” and “alternative-focused thinking.” Much like DAs used in isolation, alternative-focused thinking is reactive, identifying options in response to a problem before values are defined. In contrast, value-focused thinking recognizes that values should be the fundamental driving force behind decision-making. Available alternatives are only relevant as a means by which values can be respected and goals achieved [13].

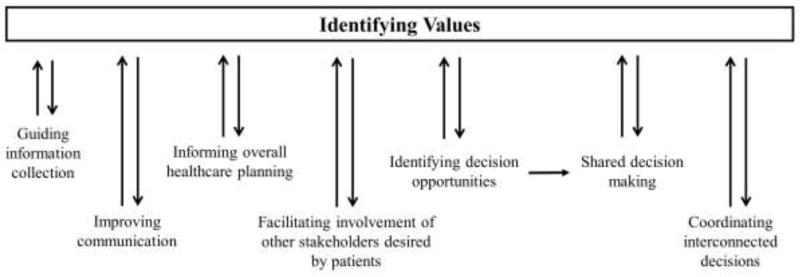

This approach acknowledges that identifying values has a broader role than simply allowing patients to weigh pros and cons of individual decisions (Figure 1). Understanding patient values can guide clinicians’ questions at follow-up visits and inform a care plan that accounts for a person’s ability to successfully work, parent, or perform a hobby. Patient values inform overall health planning and help patients and clinicians link connected decisions, such as adjusting medications for comorbidities while avoiding polypharmacy. Values may prompt a decision and also inform discussion of the relevant alternatives. Understanding values may motivate family member involvement and improve communication.

Figure 1. The Impact of Patient Values.

Identifying patient values has implications for interactions throughout health encounters, not just at the moment when there is a specific decision to be made.

Identifying values is not purely unidirectional. Improved communication leads to better value assessment. Healthcare planning, specific decisions, and available alternatives may prompt patients to consider or reconsider stated values, particularly as circumstances change. Involvement of other stakeholders such as family members can also change value assessments (Figure 1).

Taxonomy development

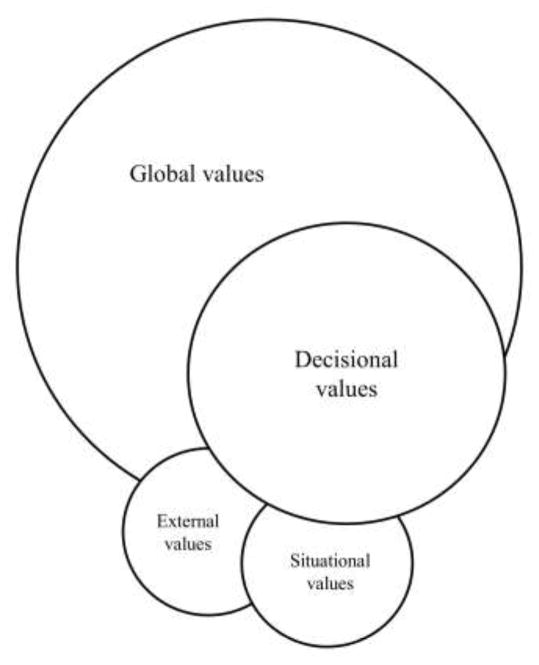

In moving towards a more comprehensive view of value assessment at the point of care, a model is needed to understand the types of values impacting healthcare decisions. Various patient engagement taxonomies exist [14, 15], but no identified taxonomies describe values underlying patient decision-making. Without a shared understanding of the types of values informing decisions, value assessments are likely to miss key contributors to decision-making. We thus propose a draft taxonomy outlining overlapping values relevant to patient decision-making (Figure 2) based on clinical experiences using an SDM model. We suggest that patients make healthcare decisions based on global, decisional, situational, and external values and provide examples of how these impact SDM.

Figure 2. Taxonomy of Patient Values Impacting Shared Decision Making.

Global values provide an over-arching context for individual decisions both within and outside the health realm. Decisional values are at the core of shared decision making, but can be modified by external and situational values.

Global values

Global values are core personal values existing beyond specific decisions, including value traits and life priorities. Value traits represent values tied to underlying personality. Patients may be risk-averse or early-adopters and this may impact approaches to all decisions. An anxious personality – whether or not anxiety relates to a clinical diagnosis – may also impact decisions, such as inclining individuals to favor more testing to exclude concerning diagnoses.

Global values also represent overarching life priorities or beliefs, a lens through which patients view all decisions. A patient’s top priority may be remaining independent in her home and she may make all decisions within that context. Global values may also reflect religious or cultural priorities. Global values may change over an individual’s life, but they have relevance for every healthcare decision regardless of specific scenario.

Knowing global values helps clinicians frame SDM discussions. If a clinician knows that a patient values continued employment over retirement or disability, treatment options and potential side effects can be framed in that context, enhancing the individualized discussion. For medical decisions with known ethical, cultural, or religious implications, such as organ donation or in vitro fertilization, clinicians may benefit from querying patients’ global values in order to best frame the discussion.

Decisional values

Decisional values relate directly to the decision needing to be made. These are the most obvious values in SDM and those most commonly addressed with DAs. Decisional values include considerations such as efficacy, toxicity, quality of life, convenience, and cost [16]. Anticipated regret may also impact decision-making [17]. SDM provides the evidence needed to weigh these considerations for any specific decision.

The challenge with decisional values is how individuals weigh competing considerations. Most patients value treatments that work, improve quality of life, have few side effects, and are convenient and affordable. Few such options exist. Patients must thus balance competing values and identify which take precedence in a situation and how best to coordinate interconnected decisions (Figure 1). The most commonly described circumstance highlighting the balance of decisional values is that of individuals facing cancer treatment. Some patients prioritize a possibility of remission or extended life and are willing to tolerate a high risk of side effects and expensive care. Others prioritize better quality of life from avoiding treatment visits and treatment-related side effects, knowing that the cancer will progress more rapidly without intervention. While efficacy, toxicity, quality of life, convenience, and cost are described here as “decisional values,” in some decisions these are also alternatives, with individuals forced to decide which alternative has the greater individual value.

Combining “values clarification” and “preference elicitation” is the approach most commonly described for informing decisional values [18]. Clinicians assist patients in clarifying the personal importance of the positive and negative elements of each alternative, a process which includes an assessment of how likely an outcome is to occur. Preference elicitation then helps patients identify the best option in that given circumstance. This process focuses on decisional values, but could clearly be framed to incorporate other taxonomy values.

Situational values

Situational values are tied to a specific context and modify global and decisional values. Situational values reflect something specific and (potentially) transient about the individual, environment, or time. A person with Parkinson’s disease may never have felt inclined to aggressively treat his tremor until preparing to walk his daughter down the wedding aisle. The situation changed his value assessment, making him more interested in therapeutic options and more tolerant of possible side effects. Similarly, a college student who has judged that the potential cognitive side effects of medications outweigh the benefit during a challenging semester may reconsider her values over summer break, when she is more inclined to try new therapies. While SDM always occurs in a specific moment, the presence of situational values emphasizes the importance of SDM as an ongoing and repeated process rather than a one-time event.

External values

Patients often consider others’ values when making decisions. This does not imply that they have relinquished decision-making or accepted an external locus of control, but rather a choice to consider others’ opinions and values alongside their own. The importance of family values and participation in medical decision-making can be cultural, such as in mainland China where family decision-making aims to reflect mutual benevolence and the Confucian ideal of family harmony [19] or in Pakistan where decision-making is based on a family-doctor-patient triad norm [20]. Even in Western cultures, arguments for joint patient and family decision-making include respect of the intrinsic community nature of decision-making within families and acknowledging that family members have vested interests in patient decisions (e.g. financial or transportation considerations) [21].

Even if prioritizing patient autonomy, external values can represent patients’ decisions to consider others’ views in addition to their own. Patients may reasonably choose to involve family and friends in medical decision-making based on ongoing relationships, reciprocal concern, respect of others’ advice, and mutual interests without implying coercion or undue influence [22]. An individual might personally prefer a palliative approach for advanced cancer yet select a more aggressive therapy based on respect for his family’s wishes.

Implications

These categories are distinct but not completely independent. All four value types – global, decisional, situational, and external – can impact any specific decision, but situational and external values are not always relevant. Decisions may change over time as patients reassess their values or situations, external supports, or priorities change (e.g. as patients enter new life phases or disease stages).

Recognition of different value categories is not trivial. Clinicians may assume that they share basic values with patients, but cultural norms informing global values may differ substantially and this may not be appreciated unless the topic is specifically addressed [23]. Opinions among clinicians and patients may prompt different approaches, but only if identified [23].

Identifying four value categories has important implications for SDM. Knowing global values can impact many elements of clinical care (Figure 1), including helping clinicians frame SDM discussions, something not well-captured in current models. Decisional values are at the heart of SDM, while external and situational values underscore the need for querying time-sensitive goals and priorities, ongoing decision reassessment as circumstances change, and providing opportunities for patients to consult with family or friends. While this draft value taxonomy requires testing with focus groups and further refinements, it highlights types of values impacting decision-making that allow a more complete value assessment within SDM.

Putting it into practice

A holistic view of value assessment at the point-of-care requires clinicians to inquire about patients’ global values at initial encounters, even before a decision is needed. Continuity of care allows patients and clinicians to incorporate identified values on an ongoing basis. Clinicians should be deliberate about understanding patients’ values, routinely incorporating them into clinical encounters and using them as a foundation for SDM. When a decision is required, clinicians should be sensitive to decisional values relating to alternatives but also to other contributing values, including offering patients the opportunity to engage others’ in decision-making and reassessing over time. Health technology manufacturers can assist by producing more patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) studies. PCOR can extend the evidence base beyond traditional value assessments toward a more holistic assessment that incorporates the IOM’s definition of patient values.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: MJA is supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) K08 career development award (K08HS24159) for research on patient engagement in clinical practice guidelines, through which this manuscript was developed.

The authors thank Del Price for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D. C: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ken Lee KH, Matthew Austin J, Pronovost PJ. Developing a measure of value in health care. Value Health. 2016;19:323–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alston CL, Paget L, Halvorson G, et al. Communicating with patients on health care evidence [discussion paper] Washington, D.C: Institute of Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit MP, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ. 2012;344:e256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elwyn G, O’Connor AM, Bennett C, et al. Assessing the quality of decision support technologies using the International Patient Decision Aid Standards instrument (IPDASi) PLoS One. 2009;4(3):e4705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connor AM, Bennett C, Stacey D, et al. Do patient decision aids meet effectiveness criteria of the international patient decision aid standards collaboration? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Decis Making. 2007;27(5):554–74. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07307319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagerlin A, Pignone M, Abhyankar P, et al. Clarifying values: an updated review. BMC Med Inform Dec Mak. 2013;13(Suppl2):S8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed September 16, 2016];The SHARE Approach. Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/index.html.

- 12.Alston C, Berger ZD, Brownlee, et al. Shared decision-making strategies for best care: patient decision aids [discussion paper] Washington, D.C: Institute of Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeney RL. Creativity in decision making with value-focused thinking. Sloan Management Review. 1994;35(4):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):985–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2037-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson AG. The meaning of patient involvement and participation in health care consultations: a taxonomy. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(6):1297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: a conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23):2563–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Speck RM, Neuman MD, Resnick KS, Mellers BA, Fleisher LA. Anticipated regret in shared decision-making: a randomized experimental study. Perioper Med (Lond) 2016;5:5. doi: 10.1186/s13741-016-0031-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Crump RT. Decision support for patients: values clarification and preference elicitation. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(1 Suppl):50S–79S. doi: 10.1177/1077558712461182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rui D. A family-oriented decision-making model for human research in mainland China. J Med Philos. 2015;40:400–17. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhv013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aslam F, Aftab O, Janjua NZ. Medical decision making: the family-doctor-patient triad. PLoS Med. 2005;2(6):e129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blustein J. The Family in Medical Decision Making. In: Monagle JF, Thomasma DC, editors. Health Care Ethics: Critical Issues for the 21st Century. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho A. Relational autonomy or undue pressure? Family’s role in medical decision-making. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(1):128–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrova M, Dale J, Fulford BK. Values-based practice in primary care: easing the tensions between individual values, ethical principles and best evidence. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(530):703–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]