Abstract

Estrogen is involved in numerous physiological processes such as growth, differentiation, and function of the male and female reproductive tissues. In the developing brain, estrogen signaling has been linked to cognitive functions, such as learning and memory; however, the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are poorly understood. We have previously shown a link between developmental dyslexia and estrogen signaling, when we studied the functional interactions between the dyslexia candidate protein DYX1C1 and the estrogen receptors α (ERα) and β (ERβ). Here, we investigate the 17β-estradiol (E2)-dependent regulation of dyslexia susceptibility 1 candidate 1 (DYX1C1) expression. We demonstrate that ERβ, not ERα, binds to a transcriptionally active cis-regulatory region upstream of DYX1C1 transcriptional start site and that DYX1C1 expression is enhanced by E2 in a neuroblastoma cell line. This regulation is dependent on transcription factor II-I and liganded ERβ recruitment to this region. In addition, we describe that a single nucleotide polymorphism previously shown to be associated with dyslexia and located in the cis-regulatory region of DYX1C1 may alter the epigenetic and endocrine regulation of this gene. Our data provide important molecular insights into the relationship between developmental dyslexia susceptibility and estrogen signaling.

The gonadal steroid hormone 17β-estradiol (E2) is involved in numerous physiological processes such as growth, differentiation, and function of the male and female reproductive tissues. In the mammalian brain of all ages, E2 influences neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and neuronal survival (1). E2 mediates its effects via the nuclear receptor transcription factors (TF) estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and -β (ERβ) to which it binds with high affinity. The ligand-bound ER attract coactivator proteins and bind promoter regions of ER-target genes modulating their transcription. Although both ER isoforms are present in the brain throughout development and into adulthood, the distribution of these receptors differs (2). Interestingly, in the hypothalamus, which is important for reproduction, the predominant form found is ERα, and ERβ is only sparsely found in certain regions of the hypothalamus (3, 4). On the other hand, the ERβ isoform has mostly been detected in regions of the rodent brain known to be important for cognitive functions, such as neocortex, hippocampus, and nuclei of the basal forebrain (4, 5). The importance of ERβ in the developing brain is further strengthened by studies on ERβ knockout mice showing that ERβ affects neuronal migration in the later stages of corticogenesis (5, 6).

The DYX1C1 (dyslexia susceptibility 1 candidate 1) gene on 15q21 was identified by analyzing a disruption of this gene through a translocation t (2;15)(q11;q21) which cosegregated with dyslexia (7). In the same study two low-frequency single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) were found to be associated with dyslexia. Later, replication studies have provided mixed results, but DYX1C1 has been shown to associate with dyslexia or verbal short-term memory in different populations (8–11). Recently, SNPs in DYX1C1 were shown to be associated with reading and spelling in two Australian sample sets representing normal populations, and in one set involving Chinese children, strengthening the role of DYX1C1 in reading ability (11–13).

The full-length variant of the DYX1C1 gene contains 10 exons with the start codon in exon 2; it encodes a 420-amino acid protein with a molecular mass of 48 kDa (NM_130810.2 and ENST00000321149). The DYX1C1 protein contains known protein domains such as a p23-domain in the N terminus and three tetratricopeptide repeat domains at the C terminus, which are thought to play a role in protein-protein interactions. Indeed, it has been shown that DYX1C1 interacts with the U-box protein carboxyl terminus of constitutive heat shock cognate 70-interacting protein, which belongs to a family of ubiquitin-protein ligases, and with heat shock proteins 70 and 90 (14–16). It is also known that the rat ortholog Dyx1c1 is involved in neuronal migration in the developing brain (17). Impaired expression of the Dyx1c1 in the rat brain causes heterogeneous brain malformations and defects in auditory processing and spatial learning (18). Interestingly, the observed malformations, such as ectopias and heterotopias, are very similar to the defects observed in postmortem human dyslectic brains (19, 20), which were later confirmed by in vivo imaging studies (21, 22).

We have previously studied the effects of SNPs in the promoter and 5′-untranslated region (UTR) region of DYX1C1. These genetic variations associated with dyslexia [rs3743205 (−3G/A), rs12899331, and rs16787] were shown to have allele-specific consequences for the binding of transcription factors to these sites and their activity. We also identified a complex of three proteins, TFII-I, splicing factor proline/glutamine-rich, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, that binds to the cis-regulatory region of the DYX1C1 5′-UTR harboring the rs3743205 (−3G/A) and showed that the protein complex can directly affect the DYX1C1 mRNA expression (23). In addition, we have shown that DYX1C1 is involved in the ER pathway by interacting with the ER in the extensions of rat primary hippocampal neurons and regulating their protein levels and transcriptional activity (24).

Here, we study further the regulation of DYX1C1 expression in connection with the estrogen-signaling pathway. Using the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line, we show that there is an E2-dependent expression of this gene, mediated by ERβ and the TFII-I transcription factor by binding the cis-regulatory region of DYX1C1 near the translation start site. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the rs3743205 (−3G/A) SNP within this regulatory region affects ERβ-dependent expression and is crucial for epigenetic regulation of DYX1C1. Our results put forward a link between estrogen signaling, epigenetics, and susceptibility for developmental dyslexia.

Results

E2 promotes DYX1C1 expression in SH-SY5Y cells in an ERβ-specific manner

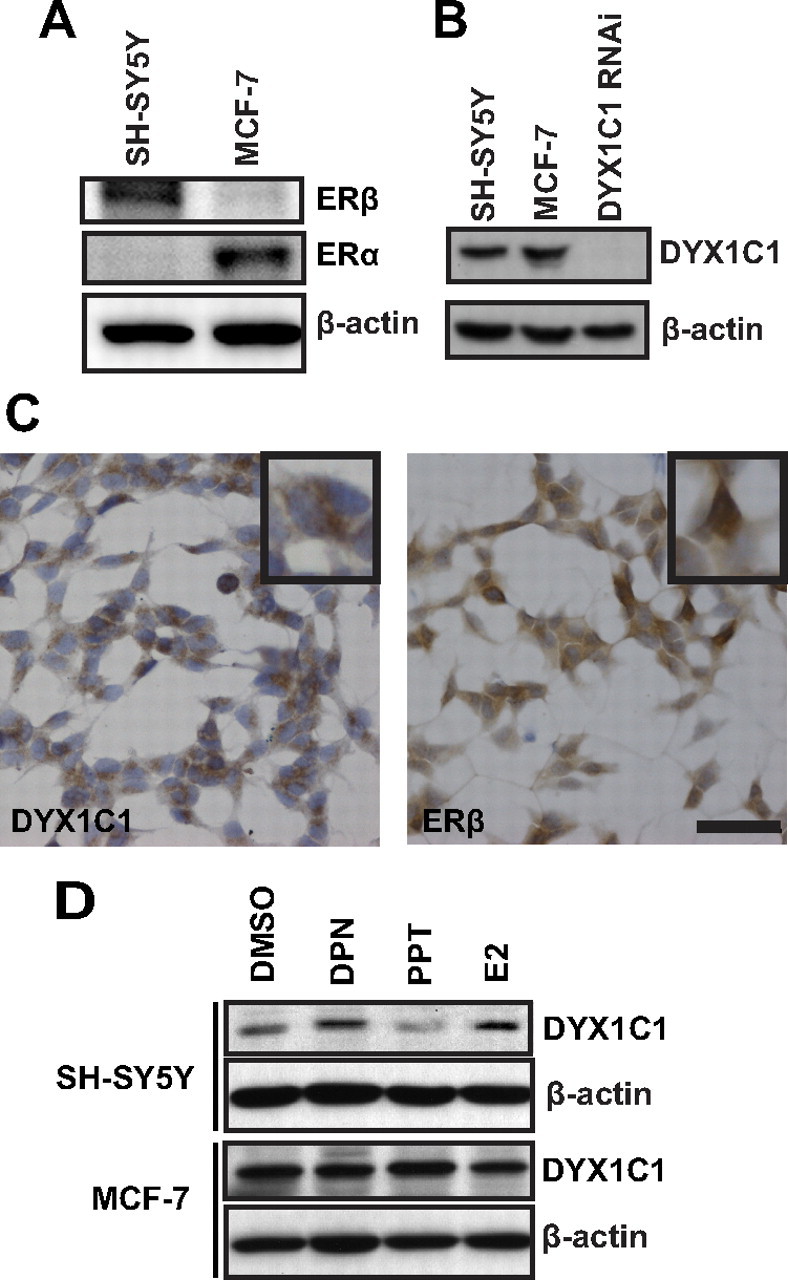

17β-Estradiol (E2) acts efficiently via both ER isoforms. To dissect the effect of one or the other isoform, it is important to use model systems that contain endogenous levels of ERα and/or ERβ. We evaluated the ERα and ERβ protein content in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y and the human mammary carcinoma cell line MCF-7S, by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A). ERβ could be detected only in the SH-SY5Y cells, whereas ERα was only present in the MCF-7S cells. In addition, we could not detect measurable mRNA levels of ERα in the SH-SY5Y cells (data not shown). DYX1C1 protein expression was detected in both cell lines (Fig. 1B). To confirm the specificity of the DYX1C1 antibody, we performed small interfering RNA (siRNA) experiment against DYX1C1 in the SH-SY5Y cell line. When analyzing the distribution of native DYX1C1 and ERβ in SH-SY5Y cells by immunocytochemistry, DYX1C1 was detected in all the cells, generally in the cytoplasm, whereas ERβ was found predominantly in the nucleus (Fig. 1C). Next, we investigated whether the expression levels of DYX1C1 in the SH-SY5Y and MCF-7S cell lines are affected by ER ligands. Interestingly, E2 increased DYX1C1 expression in SH-SY5Y but not in MCF-7S cells (Fig. 1D). The ERβ-specific agonist 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile (DPN) was able to induce DYX1C1 protein levels in SH-SY5Y cells as efficiently as the natural ER ligand E2. On the other hand, the ERα-specific agonist 4,4′,4′-(4-Propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl)trisphenol (PPT) did not increase DYX1C1 expression. These results suggest that DYX1C1 protein levels are induced by ERβ activation.

Fig. 1.

E2 promotes DYX1C1 protein expression in SH-SY5Y cells. A, Western blot analysis of ERα and ERβ in SH-SY5Y and MCF-7 cells. B, Western blot analysis of DYX1C1 in SH-SY5Y and MCF-7S cells as well as siRNA silenced DYX1C1 expression in SH-SY5Y cells. C, Immunocytochemical staining of DYX1C1 (left) and ERβ (right) in SH-SY5Y cells. Black squares are magnifications showing the subcellular localization. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, Western blot analysis of DYX1C1 protein levels upon DMSO or 10 nm DPN (ERβ agonist), PPT (ERα agonist), and E2 (ERα and ERβ agonist) treatment for 16 h.

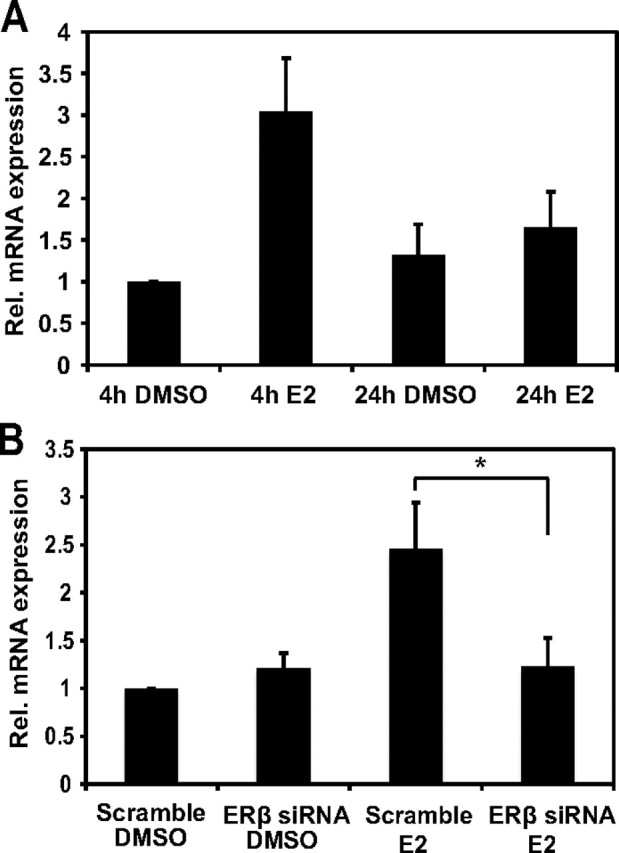

In addition we performed quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of DYX1C1 mRNA expression upon E2 treatment in the two cell lines. No differential expression for DYX1C1 upon ligand treatment was detected in the MCF-7S cell line (data not shown). In contrast, in the SH-SY5Y cell line, the expression was approximately 3-fold increased upon 4 h E2 treatment (Fig. 2A). No effect was seen after 24 h of E2 treatment suggesting a direct and transient effect of E2 on its transcription. The role of ERβ as a mediator of the E2-dependent transcription was analyzed by silencing ERβ by siRNA. A clear reduction of DYX1C1 expression could be observed upon ERβ silencing (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org).

Fig. 2.

ERβ and TFII-I are necessary for the E2-mediated DYX1C1 mRNA expression. A, qRT-PCR analysis of DYX1C1 expression in SH-SY5Y cells upon 4 h or 24 h of DMSO or E2. B, DYX1C1 mRNA expression upon 4 h E2 treatment after ERβ silencing (ERβ siRNA). The expression was normalized to cells transfected with nontargeting siRNA (scramble) and DMSO treated. Data are represented as mean ± sd. *, P < 0.05. All siRNA controls are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. Rel., Relative.

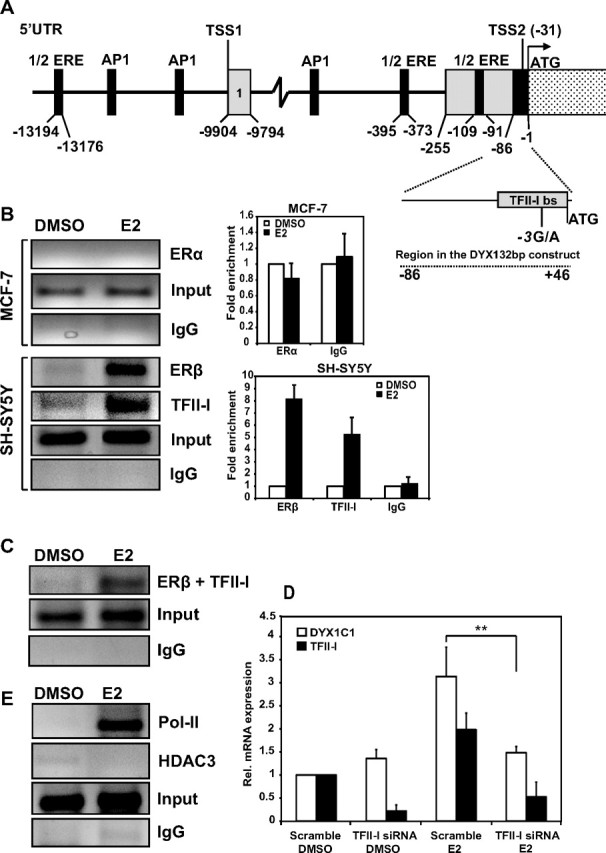

ERβ and TFII-I bind E2 dependently to the cis-regulatory region upstream of DYX1C1 translation start site

To further characterize the E2-dependent expression of DYX1C1 we analyzed possible binding regions for ERβ upstream of the start codon. According to the ENSEMBLE database (http://www.ensembl.org), the DYX1C1 gene has 12 splice variants with two different transcription start sites (TSS). For instance, three of the variants (001, 202, and 203) use TSS1 (−9904 bases from the ATG) and three variants (002, 003, and 204) use TSS2 (−31 bases from the ATG) (Fig. 3A). When searching for possible ER-binding sites in the region of these two TSS sites using the Genomatix promoter search algorithm (http://www.genomatix.de), we could identify three estrogen response element (ERE) half-sites, and three activator protein 1 (AP1) sites within approximately 14 kb from TSS2 (Fig. 2A). To test whether ER are recruited to these predicted binding sites, we conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis. However, these experiments revealed that neither ERα nor ERβ bind to these sites (data not shown). Previously, we reported on the binding of the TFII-I transcription factor to the cis-regulatory region of the DYX1C1 5′-UTR of TSS2 in SH-SY5Y cells (23), and TFII-I has been shown to interact with ERα with possible implications for E2 signaling (23, 25). Therefore, we analyzed the possible binding of ER to this region (positions −1 to −86 from the ATG) by ChIP. In MCF-7S cells expressing ERα but lacking ERβ, no binding was observed with or without E2 treatment (Fig. 3B). However, an 8-fold enrichment of ERβ binding was observed in SH-SY5Y cells upon E2 treatment. Furthermore, TFII-I was also 5-fold enriched at this region upon E2 binding. Qualitative Re-ChIP analysis revealed that TFII-I and ERβ are present simultaneously on the cis-regulatory region of DYX1C1 after E2 treatment (Fig. 3C). In addition, we analyze whether TFII-I could be important for the ERβ-mediated expression of DYX1C1 by silencing TFII-I using siRNA (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, silencing TFII-I reduced the DYX1C1 expression in a similar manner as ERβ silencing (Fig. 2B), suggesting that both ERβ and/or TFII-I are necessary for the E2-dependent DYX1C1 expression. The transcription factor RNA polymerase II was also seen recruited to the cis-regulatory region upon E2 treatment, further strengthening the role of E2 on DYX1C1 expression (Fig. 3E). On the other hand, histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3), a negative regulator of transcription, was not recruited. These findings further support a role for ERβ in the regulation of DYX1C1 expression in the SH-SY5Y cells.

Fig. 3.

ERβ binds to a cis-regulatory element in the DYX1C1 5′-UTR. A, Schematic representation of the promoter and 5′-UTR cis-regulatory regions of DYX1C1. AP1 and ERE half-sites are indicated in the 5′-UTR and promoter region. The two TSS are located in exon 1 and 2. The cis-regulatory region spans from −1 to −86 bp upstream of ATG in exon 2. This region contains the binding site for TFII-I. DYX132bp indicates the region cloned into pGL3 vector. B, Left panel, ChIP analysis of endogenous ERα, ERβ, and TFII-I binding to the DYX1C1 cis-regulatory region; right panel, qRT-PCR analysis of the ChIP results of ERα binding to the DYX1C1 cis-regulatory region in MCF-7S cells, and ERβ and TFII-I in the SH-SY5Y cell line. C. Re-ChIP analysis of ERβ and TFII-I binding to the DYX1C1 cis-regulatory region. First/second antibodies used for the immunoprecipitation steps are indicated. D, TFII-I silencing (TFII-I siRNA). The expression was normalized to cells transfected with nontargeting siRNA (scramble) and DMSO treated. E, ChIP analysis of polymerase II (Pol-II) and HDAC3 recruitment to the DYX1C1 cis-regulatory region. The cells were pretreated with DMSO or 10 nm E2 for 45 min and ChIP were analyzed by conventional PCR and qRT-PCR. Data are represented as mean ± sd. **, P < 0.01. All siRNA controls are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1.

Functional analysis of the DYX1C1 cis-regulatory element

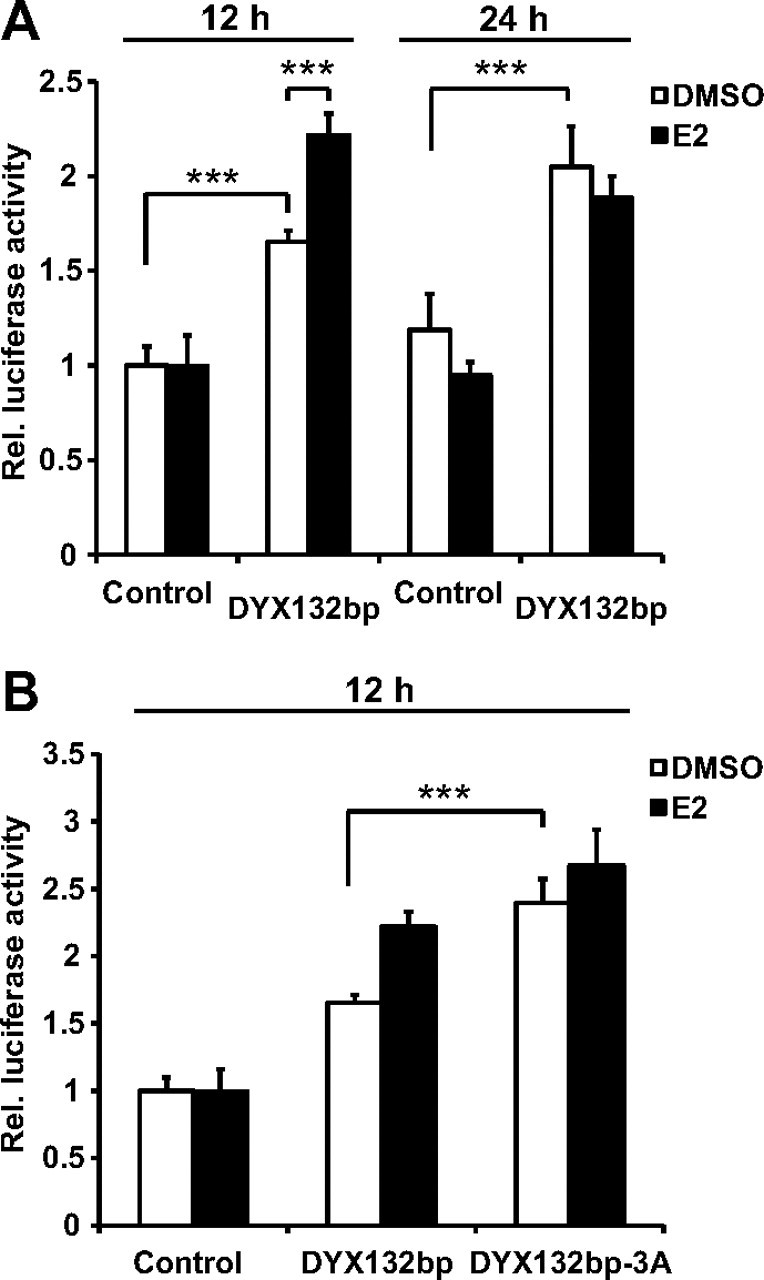

We performed luciferase assays in SH-SY5Y and MCF-7S cell lines to study whether the DYX1C1 cis-regulatory region (−1 to −86 sequence from ATG) can induce transcription in the presence or absence of E2 and endogenous ER. We cotransfected the cell lines with pGL3 promoter vector containing the DYX132bp insert fragment spanning the region −86 to +46 (pGL3prom-DYX132bp), or pGL3 promoter vector without insert (control) and pRLTK vector (containing the Renilla luciferase) for normalization (illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 2A). Cells were treated with E2 or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as control for 12 or 24 h, and the luciferase activity was measured. A significant difference between the control and DYX132bp plasmids was detected in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4A), but not in MCF-7S cells (Supplemental Fig. 2B). We also observed that 12 h of E2 treatment increased modestly but significantly the DYX132bp-mediated luciferase expression compared with vehicle treatment in the SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 4A). However, this change in expression was not as evident as in the qRT-PCR data, suggesting that additional regulatory elements outside the studied region are of importance for the E2-mediated regulation. Additionally, in Fig. 1C it appears that not all cells express equal amounts of ERβ, which could also explain this. No difference upon E2 treatment after 24 h was observed in the SH-SY5Y cells being in concordance with the endogenous expression, and suggesting immediate effects of ERβ on DYX1C1 transcription in the SH-SY5Y cell line.

Fig. 4.

Transcriptional activity of the DYX1C1 cis-regulatory region. A, Relative luciferase expression of DYX132bp construct compared with the control in SH-SY5Y measured after 12 or 24 h DMSO/E2 treatment. B, Comparison of the DYX132bp and DYX132bp-3A effect on relative luciferase expression in SH-SY5Y cells. The luciferase experiments were done three times in triplicate, and the error bars represent sd. Statistical significance was tested for different groups and compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Multiple Comparison post hoc test (***, P < 0.001). Rel., Relative.

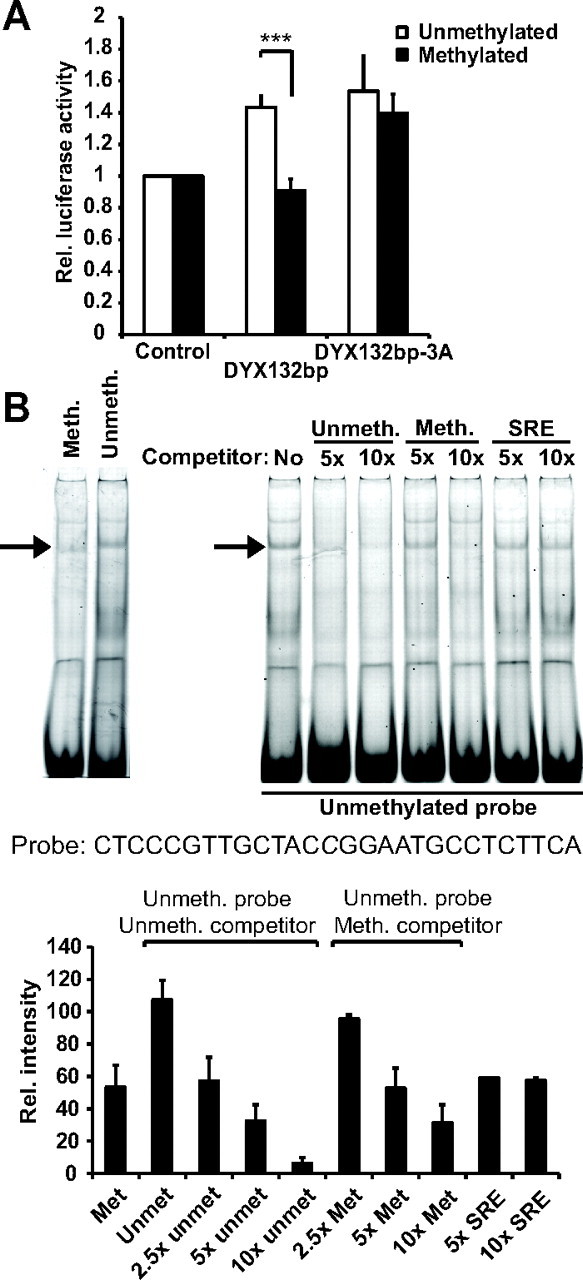

Because we have previously shown that the dyslexia-associated polymorphism rs3743205 (−3G/A) in the position −3 from ATG affects the binding of TFII-I in EMSA (23), we studied whether this polymorphism could affect the luciferase activity of the pGL3prom-DYX132bp plasmid. SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with the plasmids pGL3prom and pGL3prom-DYX132bp or pGL3prom-DYX132bp-3A containing the −3G/A SNP and treated with DMSO or E2 for 12 h. The −3A variant showed a slight but significant increase in the luciferase expression compared with the −3G variant (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, E2 treatment had no apparent effect on the luciferase expression with the pGL3prom-DYX132bp-3A plasmid. Thus the effect of liganded ERβ on DYX1C1 expression is affected by the dyslexia-associated polymorphism rs3743205.

The rs3743205 SNP is essential for the epigenetic regulation of DYX1C1

Interestingly, the rs 3743205 (−3G/A) polymorphism is predicted to be situated within a CpG island spanning −4 to +40 from the ATG (MetPrimer prediction algorithm, http://www.urogene.org/methprimer/index1.html), and loss of this CpG nucleotide could have effects on the DYX1C1 gene transcription by affecting a possible methylation site. To address whether methylation of this region in general and the CpG at −4/−3 in particular, is important for DYX1C1 expression, we carried out luciferase assays using in vitro methylated pGL3prom-DYX132bp and pGL3prom-DYX132bp-3A constructs. Surprisingly, methylation of the pGL3prom-DYX132bp construct had a drastic effect on luciferase activity whereas pGL3prom-DYX132bp-3A was not affected by methylation (Fig. 5A). This suggests that methylation of the CpG −4/−3 is sufficient to inhibit gene transcription at least from this cis-regulatory region. Additionally, it implicates that loss of this CpG by G to A mutation could have significant effects on DYX1C1 regulation by DNA methylation.

Fig. 5.

Effect of DNA methylation on activity of and transcription factor binding to DYX1C1 cis-regulatory region. A, Effect of in vitro methylation of the DYX132bp and DYX132bp-3A constructs on relative luciferase expression in SH-SY5Y cells. The luciferase experiments were done three times in duplicate, and the error bars represent sd. Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t test (***, P < 0.001). B, Mobility shift assays and competition assays using nuclear extracts of SH-SY5Y cells and a labeled unmethylated or methylated sequence encoding the cis-regulatory region of DYX1C1 (left panel). For competition assays, binding to the labeled unmethylated sequence with 2.5 to 10× excess of unmethylated and methylated unlabeled oligonucleotides are shown. Unmeth, Unmethylated probe, meth, methylated probe (at C); SRE, serum response factor element (control region) (right panel). Shown are representative gels and blots of six independent assays summarized in a relative intensity graph (bottom panel). Rel., Relative.

To investigate whether methylation of CpG at −4/−3 affects transcription factor recruitment to this region, we performed gel shift assays. We used labeled oligonucleotides encompassing the cis-regulatory region of DYX1C1 (23) with either unmethylated or methylated CpG −4/−3. These probes were incubated with nuclear extracts of SH-SY5Y cells, and the mixture was run on a native polyacrylamide gel. Subsequently, protein-DNA complexes could be detected as retarded bands (shifts) on the gel. As described previously (23), several protein-DNA complexes could be detected, including one containing TFII-I (Fig. 5B, marked with an arrow). Methylation of CpG −4/−3 resulted in a decrease of protein binding (Fig. 5B, left panel). In mobility shift competition assays, protein-DNA complex formation was measured upon addition of 5 or 10 times excess of unlabeled oligonucleotides encoding either for the unmethylated or the methylated cis-regulatory region, or a control sequence containing a TFII-I binding site (23). Unmethylated oligonucleotides as well as the control sequence were able to compete with protein binding to the labeled probe (Fig. 5B, right panel, lanes 2 and 3 and 6 and 7). In contrast, addition of the methylated sequence affected the complex to a much lesser extent (Fig. 5B, lanes 4 and 5). These results indicate that methylation at CpG −4/−3 affects transcription factor binding to the cis-regulatory region of DYX1C1. This could explain the abolishment of transcriptional activation of the methylated pGL3prom-DYX132bp construct.

Discussion

Although dyslexia has been widely studied, very little is known about the molecular mechanisms involved in the etiology of this language-based learning disorder. Studies point at different possible factors behind dyslexia. Interestingly, dyslexia appears generally to affect more boys than girls (26), and although the molecular biology behind this is largely unknown, it has been suggested that disruption of the neuroendocrine environment (e.g. circulating androgens) in the developing brain is important for the susceptibility of several cognitive anomalies (27–30). Interestingly, differences in DYX1C1 SNP haplotypes with regard to gender have been shown (10), further strengthening the link between dyslexia and E2 signaling in the developing brain. In addition, ERα and ERβ isoforms show differential expression levels at different developmental time points, both in pre- and postnatal rodent brain, where ERβ appears to be more important for areas involved in cognitive functions (5, 31). Thus, E2 signaling, in particular via ERβ, could possibly play a more direct role in the etiology of developmental dyslexia.

Here, we report that the expression of the dyslexia candidate gene DYX1C1 is regulated by ERβ in an E2-dependent manner in the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line (Fig. 1). We observed that this effect was limited to ligand-bound ERβ in a transient way, because we could not detect overexpression of DYX1C1 mRNA after 24 h of E2 treatment (Fig. 2). This could imply an active negative feedback of DYX1C1 expression, suggesting that the expression of this protein is under tight control. Furthermore, we observed that ERα does not appear to play a direct role in the expression of DYX1C1. However, a role for ERα should not be excluded. We have previously linked DYX1C1 to the estrogen pathway by showing that it physically interacts with both cytoplasmic ERα and ERβ and targets them for proteasomal degradation by the possible interaction with carboxyl terminus of constitutive heat shock cognate 70-interacting protein (24). Additionally, DYX1C1 is also expressed in cells lacking ERβ, such as MCF-7S, an ERα-positive/ERβ-negative cell line. This suggests cell-specific regulation of DYX1C1 expression. However, using the documented ERβ-positive SH-SY5Y (32, 33) and ERα-positive MCF-7S cells, we could only observe a role for E2-dependent DYX1C1 expression mediated by ERβ. Nevertheless, finding other neuronal cell lines expressing either ERα or ERβ would be of interest for dissecting the ER-mediated expression of DYX1C1. Unfortunately, it seems to be difficult to find neuronal cell lines that express significant levels of either ER.

Interestingly, our results showed that ERβ did not bind to any of the detected AP1 or ERE half-sites (Sp1 sites not analyzed) upstream of the DYX1C1 TSS1 or TSS2, but to the cis-regulatory region directly upstream of the TSS, which also harbors the −3G/A (rs3743205) SNP (Fig. 3). In addition to binding to ERE in the promoter regions of ER target genes, ER may bind to other cis-regulatory regions (34), mediating different effects on transcription. We also found the TFII-I transcription factor to bind the cis-regulatory region of DYX1C1 in an E2-dependent manner, suggesting a role for this factor in E2 signaling.

Because there are no classical ERβ-binding elements (ERE, AP1, or Sp1 sites) in the cis-regulatory region examined (according to the Genomatix promoter search algorithm), one may speculate that ERβ binds in a tethered manner to this region. Our data that TFII-I and ERβ are recruited to the sequence simultaneously in an E2-dependent manner could be suggestive of a physical interaction between these proteins that allows ERβ to bind the sequence tethered to TFII-I. Our re-ChIP and TFII-I silencing analyses further strengthen this hypothesis (Figs. 2C and 3C).

The rs3743205 −3G/A polymorphism in the 5′-UTR of DYX1C1 has been previously shown to associate with dyslexia, however, with ambiguous results because different studies indicate different risk alleles (7, 9–11, 35–38). We reported earlier that in luciferase assays, the −3A polymorphism variant of the rs3743205 showed higher transcriptional activity compared with the typical −3G variant in luciferase assays, whereas TFII-I preferably bound to the −3G variant together with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 and splicing factor proline/glutamine-rich (23). In this study we showed that the transcriptional activity of the −3G variant is increased upon E2 treatment, whereas the activity of the −3A variant was E2 independent. This suggests that the −3A variant has lost one means of regulation, namely by E2 via ERβ, and that other factors regulate the activity of this atypical variant.

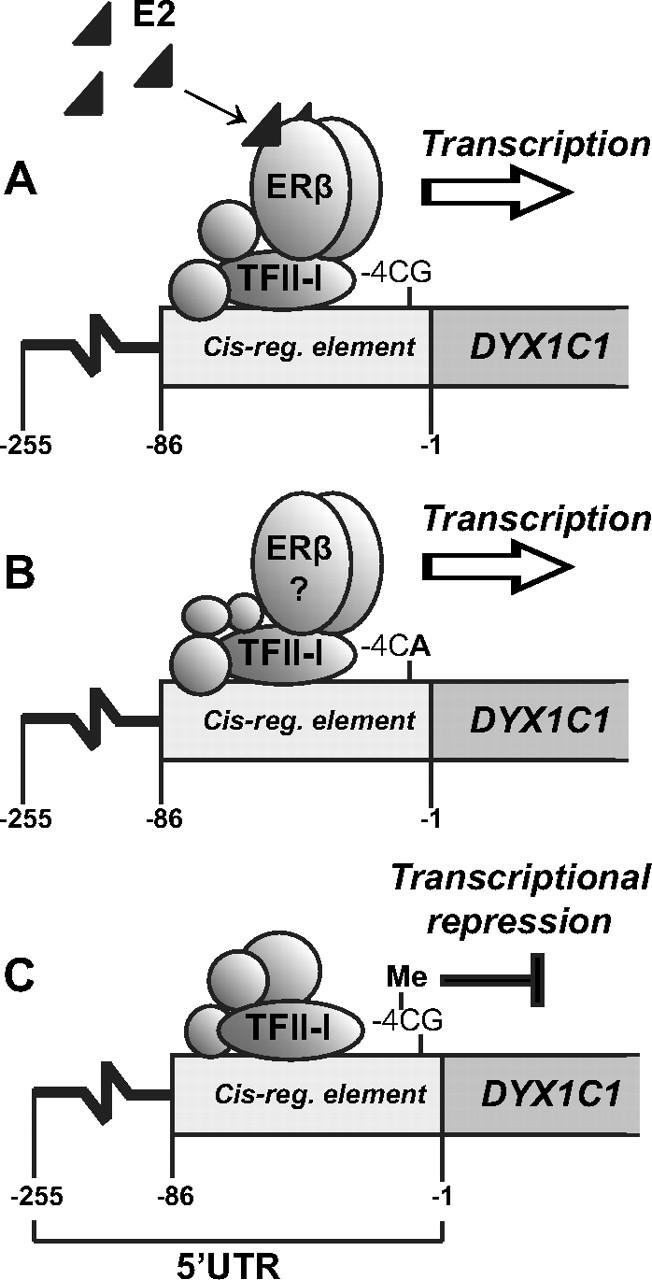

We could further demonstrate the importance of the rs3743205 SNP for DYX1C1 regulation by analyzing the effect of DNA methylation on DYX1C1 expression. The change of one nucleotide in this site, −3G to A, results in loss of the CpG −4/−3. Luciferase assays using methylated vectors showed that methylation of the −3G variant leads to complete abolishment of transcriptional activity whereas the −3A variant was not affected. This is striking as the investigated region contains in total nine CpG sites (or eight for the −3A variant) which all get methylated by in vitro methylation employed for this experiment. This particular role of CpG −4/−3 could be explained by the fact that it belongs to a transcription factor-binding site important for DYX1C1 regulation, and that methylation of this site affects transcription factor binding. Indeed, our gel-shift assays demonstrated that methylation of CpG −4/−3 impairs protein binding to this site. Thus, the loss of a CpG by the single SNP −3G/A in the cis-regulatory element could impair the epigenetic control of this gene (Fig. 6). Epigenetic mechanisms, in particular changes in DNA methylation, have been shown to be important for gene regulation during cell differentiation (39). Our findings raise the question whether DYX1C1 is epigenetically regulated, particularly during neuronal differentiation, and whether epigenetic factors could be involved in the susceptibility for dyslexia. Our data raise the possibility that during development DYX1C1 expression could be under tight neuroendocrine and epigenetic control, and that dysregulation of this control, e.g. by the −3G/A SNP, may cause prolonged DYX1C1 expression that could explain the described abnormalities in neuronal migration (18). Currently, we are establishing models to monitor DYX1C1 regulation during differentiation and development.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the epigenetic and E2-dependent regulation of DYX1C1 by ERβ in SH-SY5Y cells. A, Upon E2 treatment, both ERβ and TFII-I are enriched at the DYX1C1 cis-regulatory region in the 5′-UTR. This mediates the E2-dependnet expression of DYX1C1. B, The −3G/A SNP in the cis-regulatory region results in loss of the −4CpG and enables transcription in an E2-independent manner. The role of ERβ and TFII-I in this scenario is not clear. C, Upon methylation of this region, the −4 CpG alone is able to mediate transcriptional repression of DYX1C1. So far, the factors bound to the methylated region remain unknown. This implies that DYX1C1 transcription is regulated at several levels, both epigenetically and through E2 signaling. reg., Regulatory.

Because no causal variants have been found in the coding region of the DYX1C1 gene to explain the association with developmental dyslexia, it is important to understand the regulation of the gene expression. Future experiments, in relevant tissues and at critical time points in development, as well as human patient material, are needed to verify our in vitro results described here. Nevertheless, it is tempting to speculate that neuroendocrine signaling and epigenetic mechanisms could be molecular pathways involved in the etiology of developmental dyslexia. Interestingly, ERβ has been suggested to be involved in regulation of DNA methylation (40). Thus, it will be interesting to analyze whether ERβ can control DYX1C1 expression both as a classical transcription factor and as a regulator of DNA methylation. Apart from its effects via the transcription factors ERα and ERβ, E2 can induce rapid extranuclear effects by modulating ER binding to proteins outside of the nucleus (41). Interestingly, DYX1C1 could be such a protein. We have previously demonstrated that DYX1C1 overexpression interacts with, and targets, liganded cytoplasmic ERβ for proteasomal degradation (24).

In summary, our data demonstrate that there is an E2-dependent regulation of the expression of the dyslexia candidate gene DYX1C1. This regulation is mediated by ERβ together with TFII-I. In addition, we show that a SNP in the cis-regulatory region is crucial for the epigenetic control of DYX1C1. Thus, dysregulation of estrogen signaling and differential epigenetic control of DYX1C1 could lead to increased risk of dyslexia susceptibility.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and transient transfections

The human breast cancer cell line MCF-7S was cultured in DMEM with l g/liter glucose, 1% l-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line was cultured in MEM with Earle's salts and GLUTAMAX-I (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Before all experiments, cells were cultured 24–48 h in phenol-red free MEM (or DMEM + 1% l-Glutamine for MCF-7S), supplemented with 4% of dextran-charcoal-treated FBS (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Transfections (plasmid or siRNA) were performed using either the Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or Dharmafect I (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO), following the recommendations from the manufacturers. The cells were treated with 10 nm 17β-estradiol (E2) (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis, MO), 10 nm PPT, 10 nm DPN (2,3-bis(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile) (both from Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO), or DMSO as control, as indicated for each experiment. All cell culturing was performed at 37 C, 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator, and the medium was changed every 2–3 d.

Western blotting

Protein extracts derived from the SH-SY5Y and MCF-7S cells were separated on 10% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) in NuPAGE 3[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid sodium dodecyl sulfate running buffer and electroblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride Hybond-P transfer membranes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). After transfer of proteins the filters were blocked for unspecific protein binding by incubation for 1 h at room temperature (RT) in 5% nonfat dry milk and 1% Tween-PBS. Subsequently, filters were incubated for 1 h with the primary antibody, washed three times for 15 min in Tween-PBS, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody for 1 h. Filters were again washed using the same conditions as above, and detection was performed using light-sensitive films and the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) advance Western blotting detection kit (GE Healthcare).

The primary antibodies used in the Western blots were chicken antihuman ERβ (antibody 14021, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:700, rabbit antihuman ERα (sc-543, HC-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) diluted 1:1000, mouse antihuman β-actin (A1978, Sigma-Aldrich or antibody 6276, Abcam) diluted 1:10,000 and 1:8000 respectively, rabbit antihuman DYX1C1 (14522-1-AP; Proteintech, Manchester, UK) diluted 1:1500 and mouse antihuman TFII-I (B71520, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) diluted 1:1000. The secondary antibodies were sheep antimouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked IgG (NA934, GE Healthcare) diluted 1:5000, donkey antimouse HRP-linked IgG (NA931 GE Healthcare) diluted 1:5000, and rabbit antichicken HRP-linked IgY (A-9046, Sigma Aldrich) diluted 1:2000.

Immunocytochemistry

The immunocytochemical protocol has been described elsewhere and was carried out with only slight modifications (42). Briefly, epitopes were retrieved in heated citric buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min, and cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 0.5% H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1:1 PBS-methanol for 30 min. Unspecific antibody binding was blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h, and cells were exposed to the polyclonal rabbit anti-DYX1C1 antibody diluted 1:300 (14522-1-AP, Proteintech) or mouse antihuman ERβ 1:10 (PPG5/10; AbDserotec, Oxford, UK) overnight at 4 C. Negative controls were incubated without primary antibody. Biotinylated antirabbit antibody or biotinylated antimouse (both from Invitrogen), diluted 1:200, were used as secondary antibodies and avidin-biotin complex method (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used to amplify the signal. DAB+ Chromagen (DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA) was applied for 4 min and 1.5 min to detect the antibody binding of DYX1C1 and ERβ, respectively. The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and analyzed using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY).

siRNA gene silencing

siRNA gene silencing was performed using the On-Targetplus and siGENOME SMARTpool systems following the manufacturer's recommendations (Dharmacon). In brief, SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in phenol-red free MEM, supplemented with 4% of dextran-charcoal-treated FBS in 10 cm2 (for mRNA analysis) or 25 cm2 (for protein analysis) plates. The cells were transfected, using the DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent, with ERβ siRNA (ESR2 On-Targetplus SMARTpool siRNA, L-003402), TFII-I siRNA (GTF21 On-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA, L-013638-00), or DYX1C1 siRNA (siGENOME SMARTpool, siRNA M-015300-02-0010). Cyclophilin B siRNA (On-Targetplus SMARTpool siRNA, D001820-10) and On-Targetplus non-targeting siRNA pool (Scramble, D001810-10) were used in parallel with each experiment as positive and negative siRNA controls, respectively (all from Dharmacon). The cells were incubated with the transfection reagents in phenol-red free MEM, supplemented with 4% of dextran-charcoal-treated FBS for 48 h (for mRNA analysis and DYX1C1 protein analysis) or 70 h (for ERβ, TFII-I, and protein analysis).

qRT-PCR

Cells were grown in 3.5-cm inner diameter culture plates as described above. After treating with 10 nm E2 or DMSO (mock) for 4 h or 24 h, RNA was extracted using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Total RNA (1 μg) was treated with deoxyribonuclease I and reverse transcribed using random hexamer primers (Invitrogen). Of the resulting cDNA, 1 μl was then used for qRT-PCR using the 7500 fast real-time qPCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and a two-step amplification protocol consisting of a 2-min incubation step at 50 C and 10 min at 95 C, followed by target amplification via 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95 C and 1 min at 60 C. All real-time PCR were performed in duplicate from at least three replicates, and results were normalized to the 18s rRNA content and to the untreated samples (primers listed in Supplemental Table 2).

ChIP

ChIP assays were performed as described in Ref. 43 with slight modifications. Briefly, SH-SY5Y cells were grown on 15-cm inner diameter culture plates to 80–90% confluency in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% DCC-stripped FBS (Thermo Scientific) for 48 h. After treating with 10 nm E2or DMSO (mock) (both from Sigma) for 45 min, cells were washed with PBS, and chromatin was cross-linked for 15 min with 1.5% formaldehyde in PBS. Cells were harvested and nuclear extracts produced. Chromatin was sonicated using a Bioruptor (Diagenode, Liège, Belgium), and a fraction of the soluble chromatin was put aside as input material. ChIP was performed overnight with the indicated antibodies and protein sepharose A or G (Stratagene/Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The antibodies were rabbit antihuman ERα, H-184, mouse antihuman Pol II, F-12, mouse antihuman HDAC3, B12, normal mouse (sc-2762) and rabbit IgG (sc-2763) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse antihuman TFII-I (B71520, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and rabbit antihuman ERβ ligand-binding domain, a kind gift from Dr. M. Warner. After washing, the sepharose beads were eluted three times with 50 μl elution buffer (0.1 m NaHCO3/1% sodium dodecyl sulfate), and bound chromatin was reverse cross-linked overnight at 65 C. For re-ChIP assays, beads were washed and eluted with 10 mm dithiothreitol after the first immunoprecipitation. Eluates were diluted, and the second antibody was added overnight. The samples were then treated as in normal ChIP assays. Eluted DNA fragments were isolated and purified using PCRapace kit (Invitek, Birkenfeld, Germany), and analyzed by conventional PCR using 1 μl of ChIPed DNA and an annealing temperature of 57.3 C for 30 cycles, and/or by real-time qPCR normalized to input (primers listed in Supplemental Table 1).

Luciferase reporter assays

For the luciferase experiments, sequence −86 to +44 from the DYX1C1 translation start site ATG was amplified from SH-SY5Y cell DNA using primers containing KpnI and XhoI restriction sites (5′-gacaggtacCTGGCGCATGGTAACCCCAG-3′ and 5′-ggccctcgagCAGTCTTCGTCTGCTGCCAGC-3′). PCR product and the pGL3 basic/promoter vectors (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) were digested with restriction enzymes KpnI and XhoI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and ligated according to manufacturer's protocol. We used the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene/Agilent) to construct the 132-3A plasmid according to manufacturer's protocol. The DNA inserts of the plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The SH-SY5Y and MCF7S cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 2.5 × 106 cells per ml. After 24 h, the cells were cotransfected with 100 ng of indicated pGL3promoter plasmids and 10 ng of the pRLTK vector containing the herpes simplex thymidine kinase promoter linked to a constitutively expressing Renilla luciferase reporter gene (Promega). For studying methylation dependency of the transcription, the pGL3 promoter plasmids were in vitro methylated using SssI (NEB) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfections were carried out overnight after which the 12-h and 24-h treatments with 10 nm E2 or DMSO (vehicle) were started. The cells were harvested according to manufacturer's instructions and luciferase activity was determined using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and a TECAN Infinite luminescence reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). All data were normalized to Renilla luciferase. The experiments were done at least three times in triplicate. Statistical significance was tested for different groups and compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Multiple Comparison post hoc test using R statistical program.

Mobility shift assays

Nuclear extracts of SH-SY5Y cells were prepared as described previously (44). The mobility shift reaction was carried out as described in Ref. 23 with slight modifications. Nuclear extracts (7 μg) were preincubated with 0.5 μg of polydeoxyinosinic deoxycytidylic acid in a 10-μl reaction with 4× buffer containing 80 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 2 mm EDTA, 200 mm NaCl, 20% glycerol, and 40 mm dithiothreitol for 15 min at room temperature. Fluorescein-labeled probe oligonucleotide (1 pmol) (sequences listed in Supplemental Table 2) was added, and the reaction was incubated for additional 15 min at room temperature. The complexes were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE. For competition assays, 2.5–10 pmol unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides (sequences listed in Supplemental Table 2) were added to the initial reaction and preincubated with the nuclear extracts for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 1 pmol fluorescein-labeled probe was added. Fluorescent signals were detected using a Typhoon 9400 variable mode imager (Amersham Biosciences), and signals were quantified using ImageQuant TL (GE Healthcare).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Margaret Warner (University of Houston, Houston, TX) for providing us with the ERβ ligand-binding domain antibody.

This work was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation, the Texas Emerging Technology Fund, Swedish Cancer Fund, the Inga-Britt and Arne Lundberg′s Forskningsstiftelse, Swedish Research Council, Swedish Royal Bank Tercentennial Foundation, Swedish Brain Foundation (Hjärnfonden), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Osk. Huttunen Foundation, Academy of Finland, European Union (CRESCENDO), and the Swiss National Research Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

NURSA Molecule Pages†:

Nuclear Receptors: ER-β;

Ligands: 17β-estradiol | Diarylpropionitrile.

Annotations provided by Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas (NURSA) Bioinformatics Resource. Molecule Pages can be accessed on the NURSA website at www.nursa.org.

- AP1

- Activator protein 1

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DMSO

- dimethylsulfoxide

- DPN

- 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile

- DYX1C1

- dyslexia susceptibility 1 candidate 1

- E2

- 17β-estradiol

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- ERE

- estrogen response element

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- PPT

- 4,4′,4′-(4-Propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl)trisphenol

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- SNP

- single-nucleotide polymorphism

- TF

- transcription factor

- TSS

- transcription start sites

- UTR

- untranslated region.

References

- 1. McCarthy MM. 2008. Estradiol and the developing brain. Physiol Rev 88:91–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillies GE , McArthur S. 2010. Estrogen actions in the brain and the basis for differential action in men and women: a case for sex-specific medicines. Pharmacol Rev 62:155–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shughrue PJ , Lane MV , Merchenthaler I. 1997. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-α and -β mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 388:507–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spary EJ , Maqbool A , Batten TF. 2010. Changes in oestrogen receptor α expression in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat over the oestrous cycle and following ovariectomy. J Neuroendocrinol 22:492–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fan X , Xu H , Warner M , Gustafsson JA. 2010. ERβ in CNS: new roles in development and function. Prog Brain Res 181:233–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang L , Andersson S , Warner M , Gustafsson JA. 2003. Estrogen receptor (ER)β knockout mice reveal a role for ERβ in migration of cortical neurons in the developing brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:703–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taipale M , Kaminen N , Nopola-Hemmi J , Haltia T , Myllyluoma B , Lyytinen H , Muller K , Kaaranen M , Lindsberg PJ , Hannula-Jouppi K , Kere J. 2003. A candidate gene for developmental dyslexia encodes a nuclear tetratricopeptide repeat domain protein dynamically regulated in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:11553–11558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meng H , Hager K , Held M , Page GP , Olson RK , Pennington BF , DeFries JC , Smith SD , Gruen JR. 2005. TDT-association analysis of EKN1 and dyslexia in a Colorado twin cohort. Hum Genet 118:87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marino C , Citterio A , Giorda R , Facoetti A , Menozzi G , Vanzin L , Lorusso ML , Nobile M , Molteni M. 2007. Association of short-term memory with a variant within DYX1C1 in developmental dyslexia. Genes Brain Behav 6:640–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dahdouh F , Anthoni H , Tapia-Páez I , Peyrard-Janvid M , Schulte-Körne G , Warnke A , Remschmidt H , Ziegler A , Kere J , Müller-Myhsok B , Nöthen MM , Schumacher J , Zucchelli M. 2009. Further evidence for DYX1C1 as a susceptibility factor for dyslexia. Psychiatr Genet 19:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lim CK , Ho CS , Chou CH , Waye MM. 2011. Association of the rs3743205 variant of DYX1C1 with dyslexia in Chinese children. Behav Brain Funct 7:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bates TC , Lind PA , Luciano M , Montgomery GW , Martin NG , Wright MJ. 2009. Dyslexia and DYX1C1: deficits in reading and spelling associated with a missense mutation. Mol Psychiatry 15:1190–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paracchini S , Ang QW , Stanley FJ , Monaco AP , Pennell CE , Whitehouse AJ. 2011. Analysis of dyslexia candidate genes in the Raine cohort representing the general Australian population. Genes Brain Behav 10:158–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hatakeyama S , Matsumoto M , Yada M , Nakayama KI. 2004. Interaction of U-box-type ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) with molecular chaperones. Genes Cells 9:533–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen Y , Zhao M , Wang S , Chen J , Wang Y , Cao Q , Zhou W , Liu J , Xu Z , Tong G , Li J. 2009. A novel role for DYX1C1, a chaperone protein for both Hsp70 and Hsp90, in breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135:1265–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim YJ , Huh JW , Kim DS , Bae MI , Lee JR , Ha HS , Ahn K , Kim TO , Song GA , Kim HS. 2009. Molecular characterization of the DYX1C1 gene and its application as a cancer biomarker. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135:265–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Y , Paramasivam M , Thomas A , Bai J , Kaminen-Ahola N , Kere J , Voskuil J , Rosen GD , Galaburda AM , Loturco JJ. 2006. DYX1C1 functions in neuronal migration in developing neocortex. Neuroscience 143:515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Threlkeld SW , McClure MM , Bai J , Wang Y , LoTurco JJ , Rosen GD , Fitch RH. 2007. Developmental disruptions and behavioral impairments in rats following in utero RNAi of Dyx1c1. Brain Res Bull 71:508–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Galaburda AM , Sherman GF , Rosen GD , Aboitiz F , Geschwind N. 1985. Developmental dyslexia: four consecutive patients with cortical anomalies. Ann Neurol 18:222–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Humphreys P , Kaufmann WE , Galaburda AM. 1990. Developmental dyslexia in women: neuropathological findings in three patients. Ann Neurol 28:727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chang BS , Ly J , Appignani B , Bodell A , Apse KA , Ravenscroft RS , Sheen VL , Doherty MJ , Hackney DB , O'Connor M , Galaburda AM , Walsh CA. 2005. Reading impairment in the neuronal migration disorder of periventricular nodular heterotopia. Neurology 64:799–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang BS , Katzir T , Liu T , Corriveau K , Barzillai M , Apse KA , Bodell A , Hackney D , Alsop D , Wong ST , Wong S , Walsh CA. 2007. A structural basis for reading fluency: white matter defects in a genetic brain malformation. Neurology 69:2146–2154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tapia-Páez I , Tammimies K , Massinen S , Roy AL , Kere J. 2008. The complex of TFII-I, PARP1, and SFPQ proteins regulates the DYX1C1 gene implicated in neuronal migration and dyslexia. FASEB J 22:3001–3009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Massinen S , Tammimies K , Tapia-Páez I , Matsson H , Hokkanen ME , Söderberg O , Landegren U , Castrén E , Gustafsson JA , Treuter E , Kere J. 2009. Functional interaction of DYX1C1 with estrogen receptors suggests involvement of hormonal pathways in dyslexia. Hum Mol Genet 18:2802–2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ogura Y , Azuma M , Tsuboi Y , Kabe Y , Yamaguchi Y , Wada T , Watanabe H , Handa H. 2006. TFII-I down-regulates a subset of estrogen-responsive genes through its interaction with an initiator element and estrogen receptor α. Genes Cells 11:373–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rutter M , Caspi A , Fergusson D , Horwood LJ , Goodman R , Maughan B , Moffitt TE , Meltzer H , Carroll J. 2004. Sex differences in developmental reading disability: new findings from 4 epidemiological studies. JAMA 291:2007–2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beech JR , Beauvois MW. 2006. Early experience of sex hormones as a predictor of reading, phonology, and auditory perception. Brain Lang 96:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. James WH. 2008. Further evidence that some male-based neurodevelopmental disorders are associated with high intrauterine testosterone concentrations. Dev Med Child Neurol 50:15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garcia-Segura LM. 2008. Aromatase in the brain: not just for reproduction anymore. J Neuroendocrinol 20:705–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cornil CA , Charlier TD. 2010. Rapid behavioural effects of oestrogens and fast regulation of their local synthesis by brain aromatase. J Neuroendocrinol 22:664–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kudwa AE , Michopoulos V , Gatewood JD , Rissman EF. 2006. Roles of estrogen receptors α and β in differentiation of mouse sexual behavior. Neuroscience 138:921–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chamniansawat S , Chongthammakun S. 2009. Estrogen stimulates activity-regulated cytoskeleton associated protein (Arc) expression via the MAPK- and PI-3K-dependent pathways in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci Lett 452:130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Extier A , Perruchot MH , Baudry C , Guesnet P , Lavialle M , Alessandri JM. 2009. Differential effects of steroids on the synthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids by human neuroblastoma cells. Neurochem Int 55:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Carroll JS , Brown M. 2006. Estrogen receptor target gene: an evolving concept. Mol Endocrinol 20:1707–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scerri TS , Fisher SE , Francks C , MacPhie IL , Paracchini S , Richardson AJ , Stein JF , Monaco AP. 2004. Putative functional alleles of DYX1C1 are not associated with dyslexia susceptibility in a large sample of sibling pairs from the UK. J Med Genet 41:853–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wigg KG , Couto JM , Feng Y , Anderson B , Cate-Carter TD , Macciardi F , Tannock R , Lovett MW , Humphries TW , Barr CL. 2004. Support for EKN1 as the susceptibility locus for dyslexia on 15q21. Mol Psychiatry 9:1111–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brkanac Z , Chapman NH , Matsushita MM , Chun L , Nielsen K , Cochrane E , Berninger VW , Wijsman EM , Raskind WH. 2007. Evaluation of candidate genes for DYX1 and DYX2 in families with dyslexia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 144B:556–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Newbury DF , Paracchini S , Scerri TS , Winchester L , Addis L , Richardson AJ , Walter J , Stein JF , Talcott JB , Monaco AP. 2011. Investigation of dyslexia and SLI risk variants in reading- and language-impaired subjects. Behav Genet 41:90–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meissner A , Mikkelsen TS , Gu H , Wernig M , Hanna J , Sivachenko A , Zhang X , Bernstein BE , Nusbaum C , Jaffe DB , Gnirke A , Jaenisch R , Lander ES. 2008. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature 454:766–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rüegg J , Cai W , Karimi M , Kiss NB , Swedenborg E , Larsson C , Ekström TJ , Pongratz I. 2011. Epigenetic regulation of glucose transporter 4 by estrogen receptor β. Mol Endocrinol 25:2017–2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vasudevan N , Pfaff DW. 2008. Non-genomic actions of estrogens and their interaction with genomic actions in the brain. Front Neuroendocrinol 29:238–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fan X , Warner M , Gustafsson JA. 2006. Estrogen receptor β expression in the embryonic brain regulates development of calretinin-immunoreactive GABAergic interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:19338–19343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rüegg J , Swedenborg E , Wahlström D , Escande A , Balaguer P , Pettersson K , Pongratz I. 2008. The transcription factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator functions as an estrogen receptor β-selective coactivator, and its recruitment to alternative pathways mediates antiestrogenic effects of dioxin. Mol Endocrinol 22:304–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hardeland U , Kunz C , Focke F , Szadkowski M , Schär P. 2007. Cell cycle regulation as a mechanism for functional separation of the apparently redundant uracil DNA glycosylases TDG and UNG2. Nucleic Acids Res 35:3859–3867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]