Abstract

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) by Leishmania braziliensis is associated with decreasing cure rates in Brazil. Standard treatment with pentavalent antimony (Sbv) cures only 50–60% of the cases. The immunopathogenesis of CL ulcer is associated with high interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production. Pentoxifylline, a TNF inhibitor, has been successfully used in association with Sbv in mucosal and cutaneous leishmaniasis. This randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral pentoxifylline plus Sbv versus placebo plus Sbv in patients with CL in Bahia, Brazil. A total of 164 patients were randomized in two groups to receive the combination or the monotherapy. Cure rate 6 months after treatment was 45% in the pentoxifylline group and 43% in the control group. There was also no difference between the groups regarding the healing time (99.7 ± 66.2 days and 98.1 ± 72.7 days, respectively). Adverse events were more common in the pentoxifylline group (37.8%), versus 23% in the placebo group. This trial shows that Sbv combined therapy with pentoxifylline is not more effective than Sbv monotherapy in the treatment of CL caused by L. braziliensis.

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) caused by Leishmania braziliensis is the most frequent form of American tegumentary leishmaniasis in Brazil.1 Monotherapy with pentavalent antimony (Sbv) has been the standard treatment for decades with an increasing rate of failure in up to 47% of the cases.2

Several data show that the host immune inflammatory response is associated with the development of CL ulcers: early treatment of preulcerative lesions with Sbv does not avoid the ulcer development3; activated T cells associated with interferon (IFN)-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production correlates with ulcer size4; production of IFN-γ and TNF decreases after treatment and cure5; and the number of local CD8+ cells producing granzyme A correlates with the inflammatory infiltrate intensity.6 Therefore, targeting of inflammatory cytokines like TNF should be a useful approach to a better or a more efficient treatment of CL. Due to its capacity to inhibit TNF production, pentoxifylline was associated with Sbv in the treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis (ML) refractory cases with success.7 This association also increased the cure rate of ML when compared with Sbv monotherapy,8 as well as in CL caused by Leishmania major.9 More recently, we have shown that pentoxifylline plus Sbv therapy induced a lower peripheral production of TNF in association with cure in a small group of subjects with CL caused by L. braziliensis.10

Materials and Methods

Ethical considerations.

This trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil (CEP/MCO/UFBA-Par/Res 078/2009) and was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01381055). It was conducted based on the principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

Study design.

Subject selection.

This study was conducted in the health post of Corte de Pedra, an endemic area for L. braziliensis, in Bahia, Brazil. The inclusion criteria were the presence of 1–3 ulcerated lesions measuring 1–5 cm of diameter with less than 90 days, in a subject 18–50 years of age. CL diagnosis was confirmed by a positive Leishmania skin test associated with parasite documentation with one of these methods: positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture to Leishmania; presence of amastigotes in histopathology. The exclusion criteria were evidence of severe underlying disease (cardiac, renal, hepatic, or pulmonary), including serious infection other than CL; immunodeficiency or antibody to human immunodeficiency virus; pregnancy or lactation.

Intradermal skin test.

The volar surface of the left forearm was injected with 25 mg of antigen obtained from Leishmania amazonensis strain (MHOM-BR-86BA-125) in 0.1 mL of distilled water, and the largest diameter of induration was measured at 48 hours. The test was considered positive for induration greater than 5 mm.

Parasite culture.

Needle aspiration of the ulcer border was performed, and aspirates were cultured in Nicolle–McNeal–Novy medium overlaid with modified liver infusion tryptose medium. Cultures were kept at 25°C and examined weekly for Leishmania identification.

PCR for Leishmania DNA.

DNA isolation was carried out from biopsy samples using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Purified DNA was resuspended in Tris-ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid buffer and stored frozen at 22°C until use. For the detection of the subgenus Viannia, we applied the primers 59-GGGGT!TGGTGTAATATAGTGG-39 and 59-CTAATTGTGCACG-39. For Leishmania genus detection, we have used the primers 59 (G/C)(G/C)(C/G)CC(A/C)CTAT(A/T)TTA CAC CAA CCC C-39 and 59-GGG GAG GGG CGT-39. Amplification mixes consisted of 25 pmol of each primer, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase, 10× PCR buffer, and 2 μL of target DNA. Amplifications were carried out in a Veriti 96-well thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA). For Viannia detection, we applied 35 cycles of 1 minute at 94°C, 1 minute at 60°C, and 1 minute at 72°C. Amplicons were fractionated in 1.3% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under ultraviolet light using a UVP Vision Works LS apparatus (UVP, Upland, CA). The Leishmania-specific band consists of 120 base pairs, and that for Viannia consists of 750 base pairs.

Group assignment and treatment.

Patients were randomized into two groups (Sbv plus oral pentoxifylline or Sbv plus oral placebo), each group with 82 patients. The random allocation was obtained on the site www.randomization.com. No patients were withdrawn after randomization. Meglumine antimoniate (Sbv) (Glucantime; Sanofi, Gentilly, France) was administered intravenously at a dose of 20 mg Sbv/kg/day for 20 consecutive days (maximum daily dose of 1,215 mg) to both groups. The study group was treated simultaneously with pentoxifylline (400 mg, three times daily for 20 days), whereas the placebo group received inert pills (three times daily for 20 days) with the same aspect of pentoxifylline. Patients returned the blisters during and after treatment for regular use checking.

Study procedures.

Twenty milliliters of peripheral venous blood was collected from each patient before and 15 days after initiation of treatment to perform a complete hemogram, and tests for aminotransferases (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase), urea, and creatinine. All women in child-bearing age were submitted to beta-human chorionic gonadotropin test to exclude pregnancy. All patients were submitted to incisional biopsy on the border of the ulcer.

Follow-up schedule.

Patients were followed up at 2 weeks, 1, 2, 3, and 6 months posttherapy. Patients that did not return for follow-up were visited at home the same day or within 7 days of the missed appointment.

Clinical outcomes.

The primary outcome was cure without relapse at 6 months after completion of treatment. Secondary outcomes were 1) cure at 2 months after the end of treatment, and 2) data from clinical and laboratory adverse events (AEs). All lesions were also categorized as either active or healed (cured) at follow-up visits. Only lesions with complete reepithelialization, without raised borders or infiltrations were considered cured. Two physicians who were unaware of the group assignment independently examined the patients on all visits. Clinical and laboratory AEs were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event v3.0 of the National Cancer Institute (ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf).

Sample size and statistical analysis.

For this superiority trial, the sample size was calculated assuming an expected 25% difference between groups with α = 0.05 and a power of 80%. Comparisons between groups were done by parametric and nonparametric methods as appropriate. The intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was used to calculate the cure rates. No deviations were accepted for the final analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

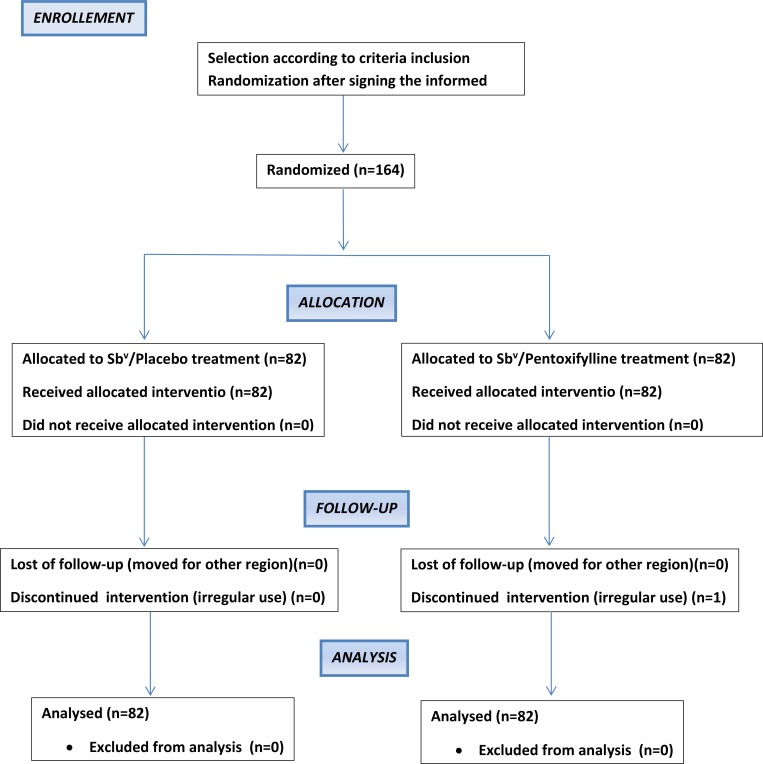

A total of 164 CL patients were included in the trial from December 2010 to October 2013 (Figure 1 ). The patients ranged in age from 18 to 62 years with a predominance of male sex in the groups. The number and size of lesions were similar in both groups (Table 1). Amastigotes were described in the histopathology in 23% of cases, a Leishmania-positive culture was obtained in 26% of patients, whereas PCR identified L. braziliensis in the majority of subjects (62%). The groups did not differ regarding Leishmania identification.

Figure 1.

Trial flowchart.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis included in the trial and treated with Sbv plus placebo or Sbv plus pentoxifylline

| Characteristics | Sbv + placebo (82) | Sbv + pentoxifylline (82) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (% of male) | 72 | 63 |

| Age (years) (M ± SD) | 33.4 ± 11.2 | 33.3 ± 10.4 |

| Number of lesions (M ± SD) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 |

| Area of lesions (mm2) (M ± SD) | 132 ± 227 | 134 ± 249.3 |

| Lesions in inferior limbs (%) | 82 | 74 |

| LST (area) (mm2) (M ± SD) | 254.8 ± 133.3 | 252 ± 138.7 |

LST = Leishmania skin test; M = media; Sbv = pentavalent antimony; SD = standard deviation.

Efficacy.

Two months after the end of the treatment, 43% (35/82) of patients in the Sbv group were cured, compared with 48% (39/82) in the pentoxifylline group (P = 0.70). The cure rates at 6 months of follow-up were 43% (35/82) in the Sbv group and 45% (37/82) in the pentoxifylline group (P = 0.64) (Table 2). The mean time to cure was 99.7 ± 66.2 days in the Sbv group and 98.1 ± 72.7 days in the pentoxifylline group. A reactivation of the ulcer was observed despite regular use of the treatment in two subjects in the pentoxifylline group, between 2 and 6 months after the end of the treatment. These cases were considered as failures at 6 months by ITT analysis. One patient in the pentoxifylline group interrupted treatment and was considered as failure at 2 and 6 months by ITT.

Table 2.

Clinical and therapeutic outcome data from CL patients treated with the combination of pentoxifylline and Sbv or placebo and Sbv

| Characteristics | Sbv + placebo | Sbv + pentoxifylline | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cure rate at 60 days (%) | 35/82 (43) | 39/82 (47.5) | 0.70 |

| Cure rate at 180 days (%) | 35/82 (43) | 37/82 (45) | 0.64 |

| Healing time (days) (M ± SD) | 99.7 ± 66.2 | 98.1 ± 72.7 | 0.87 |

CL = cutaneous leishmaniasis; M = media; Sbv = pentavalent antimony; SD = standard deviation.

Student's t test.

Toxicity and tolerability.

In general, AEs were more common in the Sbv plus pentoxifylline group (31 patients) than in Sbv plus placebo group (19 patients). However, severe AEs were more common in the placebo group (nine patients) when compared with the pentoxifylline group (one patient) (Table 3). The most common side effects observed in pentoxifylline group were myalgia (11 patients), headache (nine patients), nausea (seven patients), and arthralgia (seven patients). In the placebo group, it was arthralgia (10 patients) and myalgia (six patients). No cardiological AE was documented in both groups.

Table 3.

Clinical toxicity data in patients with CL treated in both groups

| Side effect symptoms (%) | Sbv + Pentoxifylline | CTC Grade | Sbv + Placebo | CTC Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vomiting | 02 (2.4) | 2 (2)* | NR | NR |

| Diarrhea | 01 (1.2) | 2 (1) | NR | NR |

| Nausea | 07 (8.6) | 1 (5) | 02 (2.4) | 2 (2) |

| 2 (2) | ||||

| Headache | 09 (11) | 1 (4) | 05 (06) | 2 (3) |

| 2 (5) | 3 (2) | |||

| Asthenia | 03 (3.7) | 1 (1) | 02 (2.4) | 1 (1) |

| 2 (2) | 3 (1) | |||

| Anorexia | 03 (3.7) | 1 (1) | 01 (1.2) | 3 (1) |

| 2 (2) | ||||

| Epigastralgia | 03 (3.7) | 1 (2) | 02 (2.4) | 2 (1) |

| 2 (1) | 3 (1) | |||

| Pain | 02 (2.4) | 1 (1) | 02 (2.4) | 1 (2) |

| 2 (1) | ||||

| Dizziness | 02 (2.4) | 1 (2) | NR | NR |

| Fever | 06 (7.4) | 1 (3) | 02 (2.4) | 1 (1) |

| 2 (3) | 2 (1) | |||

| Arthralgia | 07 (8.6) | 1 (4) | 10 (12) | 1 (6) |

| 2 (3) | 2 (2) | |||

| 3 (2) | ||||

| Myalgia | 11 (13.5) | 1 (8) | 06 (7.3) | 1 (2) |

| 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |||

| 3 (1) | 3 (2) | |||

| Total | 31 (37.8) | 19 (23) |

CL = cutaneous leishmaniasis; CTC = common toxicity criteria; NR = not registered; Sbv = pentavalent antimony.

In parenthesis, the number absolute of patients for each CTC grade.

Discussion

The treatment of CL caused by L. braziliensis is associated with a higher therapeutic failure when compared with CL due to other Leishmania species.11 Considering that the host inflammatory immune response associated with high TNF-α production is related to tissue damage in ML and CL, the combination of pentoxifylline to Sbv has been evaluated in several studies. For instance, this association was able to cure nine of ten refractory ML subjects,7 increased the cure rate of ML when compared with Sbv monotherapy in a randomized and controlled trial,8 and cured two refractory CL cases.12 In CL caused by L. major, a clinical trial conducted in Iran showed that the group treated with Sbv and pentoxifylline had a higher cure rate than subjects treated with Sbv monotherapy.9 More recently, our group showed in a pilot trial that although Sbv–pentoxifylline association in CL was not associated with a higher cure rate, it decreased TNF levels and IFN-γ significantly when compared with treatment with Sbv and placebo.10 We have also documented that CXCL-9 levels increased during treatment in both groups, but in a lesser extent in subjects using the association. Therefore, this modulation in the inflammatory immune response could have a positive impact in therapeutic outcome. Based on these previous data, we designed this clinical trial in a larger number of patients, with power to confirm that the association could benefit CL caused by L. braziliensis and be indicated as standard therapy to replace Sbv monotherapy. However, our study did not show a higher cure rate and better therapeutic outcome in the subjects treated with pentoxifylline and Sbv. Pentoxifylline is considered a safe drug, with the main side effects related to gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) and without cardiac toxicity described,8,9 favoring the association with Sbv. Although a higher rate of AEs were described in the pentoxifylline group, severe toxicity were documented mainly in the placebo group, confirming that Sbv therapy is as ineffective as toxic and should be replaced with safer and more effective drugs. A possible limitation of this study is the monthly follow-up schedule which does not allow a precise determination of the time to cure. We conclude that although associated immunotherapy with pentoxifylline is useful in the treatment of ML, it should not be indicated to treat patients with CL caused by L. braziliensis.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was funded by INCT-DT 573839/2008-5 and ICIDR grant AI088650.

Authors' addresses: Graça Brito, Mayra Dourado, Luiz Henrique Guimarães, Albert Schriefer, Edgar Marcelino de Carvalho, and Paulo Roberto Lima Machado, Serviço de Imunologia, Complexo Hospitalar Universitário Professor Edgard Santos, Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, Brazil, E-mails: gracaobrito@yahoo.com.br, mayradourado@hotmail.com, luizhenriquesg@yahoo.com.br, aschriefer@globo.com, edgar@ufba.br, and prlmachado@uol.com.br. Everson Meireles, Laboratório de Instrumentação e Avaliação Psicológica, Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia/Centro de Ciências da Saúde (CCS), Santo Antônio de Jesus, Brazil, E-mail: eversoncam@yahoo.com.br.

References

- 1.Grimaldi G, Jr, Tesh RB, McMahon-Pratt D. A review of the geographic distribution and epidemiology of leishmaniasis in the New World. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41:687–725. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.41.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machado PR, Ampuero J, Guimarães LH, Villasboas L, Rocha AT, Schriefer A, Sousa RS, Talhari A, Penna G, Carvalho EM. Miltefosine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania braziliensis in Brazil: a randomized and controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machado P, Araújo C, Da Silva AT, Almeida RP, D'Oliveira A, Jr, Bittencourt A, Carvalho EM. Failure of early treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in preventing the development of an ulcer. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E69–E73. doi: 10.1086/340526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonelli LR, Dutra WO, Almeida RP, Bacellar O, Carvalho EM, Gollob KJ. Activated inflammatory T cells correlate with lesion size in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Immunol Lett. 2005;101:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribeiro-de-Jesus A, Almeida RP, Lessa H, Bacellar O, Carvalho EM. Cytokine profile and pathology in human leishmaniasis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1998;31:143–148. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1998000100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faria DR, Souza PE, Durães FV, Carvalho EM, Gollob KJ, Machado PR, Dutra WO. Recruitment of CD8+ T cells expressing granzyme A is associated with lesion progression in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2009;31:432–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lessa H, Machado P, Lima F, Cruz A, Bacellar O, Guerreiro J, Carvalho EM. Successful treatment of refractory mucosal leishmaniasis with pentoxifylline plus antimony. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:87–89. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado PRL, Lessa H, Lessa M, Guimarães LH, Bang H, Ho J, Carvalho EM. Oral pentoxifylline combined with pentavalent antimony: a randomized trial for mucosal leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:788–793. doi: 10.1086/511643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadeghian G, Nilforoushzadeh MA. Effect of combination therapy with systemic glucantime and pentoxifylline in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:819–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brito G, Dourado M, Polari L, Celestino D, Carvalho LP, Queiroz A, Carvalho EM, Machado PRL, Passos S. Clinical and immunological outcome in cutaneous leishmaniasis patients treated with pentoxifylline. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:617–620. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arevalo J, Ramirez L, Adaui V, Zimic M, Tulliano G, Miranda-Verástegui C, Lazo M, Loayza-Muro R, De Doncker S, Maurer A, Chappuis F, Dujardin JC, Llanos-Cuentas A. Influence of Leishmania (Viannia) species on the response to antimonial treatment in patients with American tegumentary leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1846–1851. doi: 10.1086/518041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bafica A, Oliveira F, Freitas L, Nascimento EG, Barral A. American cutaneous leishmaniasis unresponsive to antimonial drugs: successful treatment using combination of N-methilglucamine antimoniate plus pentoxifylline. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:203–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]