Combined results from gene expression and bioinformatics analyses defined ERβ regulations previously unknown and identified regulatory mechanisms with implications for colon cancer.

Abstract

Several studies suggest estrogen to be protective against the development of colon cancer. Estrogen receptor β (ERβ) is the predominant estrogen receptor expressed in colorectal epithelium and is the main candidate to mediate the protective effects. We have previously shown that expression of ERβ reduces growth of colorectal cancer in xenografts. Little is known of the actions of ERβ and its effect on gene transcription in colon cancers. To dissect the processes that ERβ mediates and to investigate cell-specific mechanisms, we reexpressed ERβ in three colorectal cancer cell lines (SW480, HT29, and HCT-116) and conducted genome-wide expression studies in combination with gene-pathway analyses and cross-correlation to ERβ-chromatin-binding sites. Although induced gene regulation was cell specific, overrepresentation analysis of functional classes indicated that the same biological themes, including apoptosis, cell differentiation, and regulation of the cell cycle, were affected in all three cell lines. Novel findings include a strong ERβ-mediated down-regulation of IL-6 and downstream networks with significant implications for inflammatory mechanisms involved in colon carcinogenesis. We also discovered cross talk between the suggested nuclear receptor coregulator PROX1 and ERβ, demonstrating that ERβ both regulates and shares target genes with PROX1. The influence of ERβ on apoptosis was further explored using functional studies, which suggested an increased DNA-repair capacity. We conclude that reexpression of ERβ induces transcriptome changes that, through several parallel pathways, converge into antitumorigenic capabilities in all three cell lines. We propose that enhancing ERβ action has potential as a novel therapeutic approach for prevention and/or treatment of colon cancer.

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer in the Western world. Men are more likely to develop this disease compared with women of similar age. Studies designed to investigate the long-term health effects of hormone replacement therapy have shown that this treatment reduces the risk of colorectal cancer (1, 2). These findings indicate that estrogen may lower the risk for colorectal cancer. Estrogen acts via two receptors, i.e. estrogen receptor α (ERα) and estrogen receptor β (ERβ). The two ERs are highly similar in their DNA-binding domain but differ in their ligand-binding domain, as well as in their transcriptional activating function and coregulator binding. As a result, the two receptors exert distinct actions that vary widely in different cell types, most likely due to variations in expression and ratio of the two ERs, coregulators, and activities of other cross-signaling pathways. A decreased expression of ERβ, or an increased ERα/ERβ ratio, has been shown in many cancers (3–5). This change of ERα and ERβ expression in cancer progression suggests that the two receptors have different roles in this process. In breast cancer ERα has been shown to promote proliferation, whereas reintroduction of ERβ results in an antiproliferative effect (6–10). We have previously demonstrated that ERβ opposes ERα regulation of many genes in breast cancer but also affects genes not regulated by ERα (11). ERβ is the predominant ER in the human colonic epithelium (12). The levels of ERβ are reduced in colorectal cancer compared with normal colonic tissue, and this has been reported to be related to loss of differentiation and advanced Dukes staging (12–15). Collectively, these observations imply a protective role of ERβ in colorectal cancer. The protective role of ERβ in colon cancer progression has further been confirmed in in vivo studies with mice that spontaneously develop intestinal adenomas (ApcMin/+) in which deletion of ERβ lead to an increase in size and number of adenomas (16) and treatment with an ERβ-specific agonist had the opposite effect (17).

Whereas the function and effect of ERβ on gene regulation have been studied in breast cancer where ERα is also present, ERβ's genome-wide regulation on its own, in colon cancer cells, is not known. In this study we dissected the gene-regulatory events after ERβ expression in the SW480 cells. To examine the variations between different cell lines, we overexpressed ERβ in two additional ERα-negative human colon cancer cell lines; HT29 and HCT-116. Because ERβ expression is decreased during colon cancer progression, no colon cancer cells lines express any significant amount of ERβ. The lack of immortalized cells lines expressing the protein is one of the challenges when studying transcriptional regulation by ERβ (18). Introduction of ERβ in colon cancer cell lines, but not ERα, because normal colonic mucosa only express very low levels of the protein, is a way to restore the lost endogenous expression of ERβ and to study the effect ERβ has on colon cancer cells. It is not certain that this method will fully restore the physiological situation of the once lost endogenous expression of ERβ, but it will serve as a tool for in vitro mechanistic studies of ERβ, to gain a better insight of the role of ERβ in tumor cells and serve as guidance for future in vivo studies. We used microarrays to study the genome-wide changes that ERβ induces in these cells followed by in silico pathway analysis to decipher the signaling networks activated by ERβ expression. By cross-correlating our gene-expression data with genome-wide ERβ-promoter-binding assays in a system biology approach, we separated primary gene regulation events from secondary downstream effects. Confirmatory experiments were performed using real-time PCR, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), and functional studies. The combined results of this unbiased study enabled us, for the first time, to report the mechanisms behind the action of ERβ in colon cancer cells.

Results

We have previously shown that ERβ affects key cell cycle proteins in both the colon cancer cell line SW480 and in the breast cancer cell line T47D, causing a reduction in cellular proliferation and xenograft growth (8, 11, 19). Our present study focuses on the genome-wide alterations that occur when ERβ is reexpressed in colon cancer cells, mimicking the biologically relevant therapeutic scenario of a tumor adapting to reexpressed or reactivated ERβ. In addition, we chose to explore cell-specific events and variations of ERβ action in three different colon cancer cell lines.

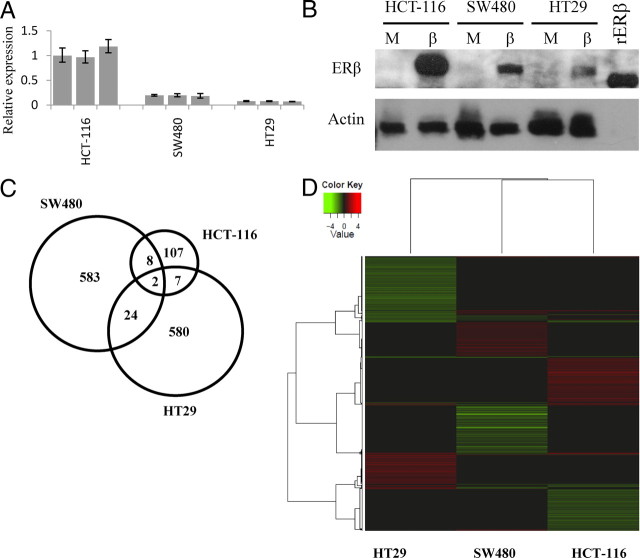

Western blot and real-time PCR for ERβ showed that both the protein and transcript are expressed in all three cell lines after transfection. HCT-116 expresses about 5 times more ERβ compared with SW480, which in turn expresses twice the amount compared with HT29 (Fig. 1, A and B).

Fig. 1.

Levels of ERβ in the three colon cancer cell lines. A, Real-time PCR showing transcript levels of ERβ in three separately ERβ transfected clone mixes for each cell line. B, Flag-ERβ Western blot. rERβ has a molecular weight of 59 kb, actin has a molecular weight of 42 kb. Not many differentially expressed genes were commonly regulated in the three colon cancer cell lines as illustrated by the Venn diagram (panel C) and Heatmap (panel D) showing hierarchical clustering of the 2000 genes with highest B value from each array experiment. Clustering of rows and columns was made with average linkage of Pearson correlations.

ERβ exerts extensive genome-wide regulation

ERβ expression resulted in large genome-wide gene expression changes. We detected 623, 613, and 124 differentially regulated transcripts in SW480, HT29, and HCT-116, respectively. Few genes were identically regulated by ERβ in all three cell lines, as shown in the Venn diagram in Fig. 1C. Consequently, the ERβ-induced gene regulation is cell specific in different colon cancer cell lines. Cluster analysis comparing the genome-wide ERβ-controlled genes is shown in Fig. 1D. We note that the effect of ERβ is slightly more similar between SW480 and HT29 compared with HCT-116. Complete lists of differentially regulated transcripts and real-time PCR confirmations are available in Supplemental Table 1 published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org.

Analysis of overrepresented groups among the ERβ-regulated genes showed that similar biological processes were affected in all three cell lines, as exemplified in Table 1. Protein binding, apoptosis, regulation of cell cycle, cell differentiation, proliferation and kinase activity are examples of significantly overrepresented Gene Ontology groups. Thus, ERβ initiates similar biological events in different colon tumor cells via regulation of individual cell-specific genes and pathways. Furthermore, in SW480 cells the IL-6 signaling pathway represented a significantly enriched subnetwork (P value 0.031). Real-time PCR confirmed a massive down-regulation of IL-6 by ERβ in all three clone mixes of SW480. As a consequence of the IL-6 inactivation, 10 IL-6 target genes were down-regulated as illustrated in Fig. 2 (lower panel). In HT29 cells the most notable enriched subnetworks were MAPK1 (ERK2) and MAPK3 (ERK1) (P values of 0.021/0.045). MAPK and MAPK1 pathways were also affected in HCT-116 cells (P value 0.078/0.373). We did not detect any changes of MAPK1 or MAPK3 transcript levels, but downstream target genes and mediators of the MAPK1/3 phosphorylation pathways such as SP-1, VEGF, and JUN1 (20), were down-regulated after ERβ expression. The MAPK1 and MAPK3 networks influenced by ERβ are depicted in Table 2.

Table 1.

Overrepresented pathways and gene ontology groups

| Categorya | SW480 | HCT-116 | HT29 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation of cell cycle | 9.39E-03 | 1.50E-02 | 1.37E-11 |

| Kinase activity | 1.18E-02 | 3.60E-02 | 2.50E-03 |

| Cell differentiation | 6.55E-04 | 3.26E-02 | 1.43E-02 |

| Apoptosis | 5.36E-07 | 1.85E-02 | 5.89E-04 |

| Protein binding | 1.03E-13 | 4.59E-05 | 3.80E-28 |

| DNA repair | 7.85E-01 | 3.81E-01 | 3.71E-06 |

| Cell adhesion | 1.62E-07 | 6.78E-02 | 2.75E-03 |

Analysis is based on both up-regulated and down-regulated genes. A category is statistically significant when P < 0.05 (marked in bold). For each category, a P value is given for each cell line.

Category represents main gene ontology group but P value may represent a subgroup to this main group.

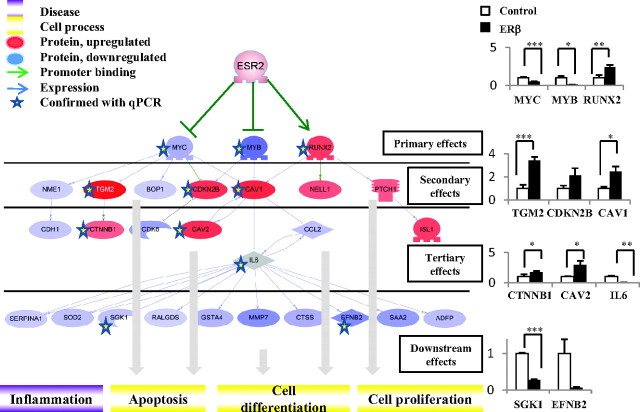

Fig. 2.

Comparison of our microarray data with ERβ-promoter-binding data showed that ERβ binds directly to the three transcription factors MYC, MYB, and RUNX2. Bioinformatics analysis showed that these, in turn, regulate several of the genes observed on the array. A combination of change in primary, secondary, tertiary, and further downstream genes leads to downstream effects such as decreased cell proliferation and apoptosis. Red genes are up-regulated on the microarray; blue genes are down-regulated. The intensity of color is related to fold change of the gene transcript from our array study: stronger color is more significant. Real-time PCR confirmations to the right, y-axis: relative expression (fold change).

Table 2.

Enriched subnetwork analysis in HT29 and HCT-116 showed that ERα and ERβ regulates genes in the MAPK1, MAPK3, and MAPK networks

| HCT-116 | HT29 |

|---|---|

| MAPK1 | MAPK1 |

| Up-regulated | Up-regulated |

| RABEP2, CYP24A1, BIM, TGM2, ERRFI1, ZFP36 | S100A4, TGFBI, KRT18, TIMP2, E2F1, TGM2, AQP3, HSPB1, CLDN2 |

| Down-regulated | Down-regulated |

| S100A4 | GDF15, UTRN, DDIT4, NFE2L2, ERRFI1, VEGFA, ITGB1, CD44, ITGA2, CA9,CYP2B6, CXADR, JUND |

| MAPK | MAPK3 |

| Up-regulated | Up-regulated |

| RABEP2, CYP24A1, BIM, ZFP36, SGK1, GADD45B | HSPB1, CLDN2, TIMP2, KRT18, S100A4, TGFBI |

| Down-regulated | Down-regulated |

| CLU | VEGFA, ITGB1, JUND, NFE2L2, GDF15, SP1 |

The antiproliferative effect of ERβ in SW480 was previously shown to be estrogen independent (19). For a comprehensive understanding of ligand-dependent gene regulation in colon cancer cells, cells treated with estrogen (24 h) were compared with vehicle-treated cells and gene expression was analyzed by microarray. SW480, HT29, and HCT-116 cells showed no transcriptional changes following after treatment. Thus, no genes could be detected that were regulated upon ligand treatment. This was confirmed by real-time PCR (Supplemental Fig. 1). Accordingly, there does not appear to be any estrogen-dependent endogenous gene regulation in these cell lines. Notably, no false positives were observed in our microarray analysis, indicating a high accuracy of the method used.

ERβ expression elicits antitumorigenic cascades

A number of genes shown to be involved in metastasis, tumor formation, proliferation, angiogenesis, and tumor cell invasion were down-regulated by ERβ expression in the three cell lines (Table 3). ERβ has previously been suggested to reduce the risk of breast cancer by facilitating terminal differentiation of mammary gland epithelium (21). Cell-differentiation genes were overrepresented upon expression of ERβ in the colon cancer cells. Several genes associated with increased differentiation were up-regulated, and genes associated with inhibition of differentiation were down-regulated in all three cell lines (Table 3).

Table 3.

ERα and ERβ−regulated genes (gene symbol) shown to be involved in anti-/apoptosis, anti-/tumorigenesis (metastasis, tumor formation, proliferation, angiogenesis, tumor cell invasion) and de-/differentiation for each cell line

| Cell line | Up-regulated | Down-regulated |

|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | ||

| SW480 | TP53INP1, TPD52L1, VIM, AHR, DUSP6, TGM2, CTGF, BMP4, IGFBP7, CAV1, TLR4, ANXA1, ANXA5, EPAS1, CTNNB1, LEF1, PTCH1, APOD, NCOA1, CDKN2B, TNFRSF12A, ACVR1, ARF4, ITGA3, EDAR, LATS2, TRAF6, MAP1B, IL17RD, MYCBP2, CAV2, RERE, UACA, NELL1 | MYB, BIRC2, CCl2, TNFRSF18, ZFP36L2, VIL1, TXNDC17, TRAF5, TPP2, TNFAIP3, THOC5, SOD2, SGK1, SERPINA1, RELB, RALGDS, PROX1, NOL3, JAG1, ICAM1, GSTA4, AHCY, ADA |

| HCT-116 | BIM, TGM2, IGFBP6, LIF, CEBPB, CTSD, ZFP36, TFAP2C, HSPB8, HBA1, SEMA3B, ERRFI1, SMOX, FHL2, OLFM1 | CLU, INSR, KITLG, S100A4, SMAD6 |

| HT29 | E2F1, CEACAM1, CDC20, AMPH, TGM2, IFIH1, CD38, CALR, TGFBI, KRT18, LGALS9, OAS1, SDC1, EPHB6, CFL1, AFP, LGALS1, PADI2, NF2, MAGOH, RARRES3, SEPT8 | NRAS, JUND, BRAF, CD44, VEGFA, RB1, NPM1, GRB10, ACSL4, ASNS, CLCN3, NFE2L2, ITGB1, AREG, GNAI1, PRKCI, S100P, F5, DDIT4, ATF7IP, PLD1, CDK7, TOPBP1, HSPA9, BIRC6, SUZ12, TOP2A, ZNF217, CEACAM6, TPP2, BHLHB2, REV3 liter, RANBP2, RPL28, TAX1BP1, REG4 |

| Antitumorigenica | ||

| SW480 | CAV1, IGFBP7 | MMP-7, PRDX4, EDN1, CXCL6 |

| HCT-116 | CEBPB, IGFBP6, SEMA3B, MXD1 | S100A4 |

| HT29 | CEACAM1, SDC1, TIMP-2 | VEGFA, MET, CD44, CXR4, PRKC1, BRAF, CEACAM6, ZNF217, KRAS, AREG |

| Differentiation | ||

| SW480 | BDNF, KITLG, BMP4, ANXA1 | MYB, SPRY1, LRP5, CDK6, GNAS, SOX4, NFKBIA |

| HCT-116 | CEBPB, TGM2 | SMAD6 |

| HT29 | MKD, HSP27, CALR, CD38 | CDC2, CDK6, CEACAM6, NR2F2, NPM1 |

Because the expression of ERβ in our study is nontransient, a considerable number of the alterations detected are expected to be secondary effects. To dissect the order of events, we first assumed that genes with reported ERβ-chromatin-binding sites were direct targets of ERβ. Genome-wide ERβ protein-binding studies have only been performed in breast cancer MCF-7 cells (22), in which 11% of the genome has ERβ-binding sites. Of the ERβ-regulated genes, 17% (SW480), 14% (HT29), and 23% (HCT-116), respectively, had one or more ERβ-binding sites (Supplemental Table 2). Compared with the expected frequencies of 11%, Chi-square test showed that there was a significant overrepresentation of regulated genes harboring an ERβ-binding site (P values = 0.01076 for SW480; 0.04005 for HT29; and 0.00029 for HCT-116). This indicates that the detected ERβ-regulated genes in all three cell lines result from ERβ binding to cis-regulatory elements. Subsequent bioinformatic analysis showed that 10 transcription factors were regulated by ERβ through chromatin binding in SW480 cells (up-regulated: AHR, CITED2, RUNX2, down-regulated: MYC, MYB, FOXP1, EHF, SOX4, ZFP36L2, TFAM). We have previously observed ERβ regulation of MYC, MYB, ZFP36L2, and FOXP1 in T47D breast cancer cells (11). In HCT-116 cells, three transcription factors were directly regulated by ERβ (up-regulated, CEBPB, TFAP2C; down-regulated, SMAD6) and in HT29 cells, seven transcription factors were directly regulated by ERβ (all down-regulated: FOXP1, ZNF217, ZNF295, CTR9, NFIB, BHLHE40, SP3). FOXP1, thus regulated by ERβ in both SW480 and HT29 and in breast cancer cells, has also been associated with expression of ERα and ERβ in clinical breast cancer samples (23).

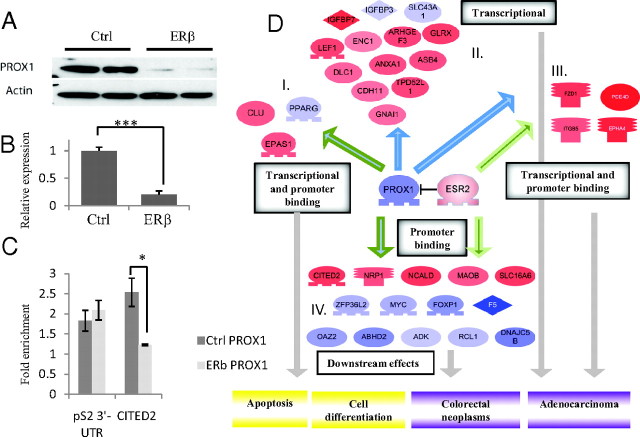

As illustrated in Fig. 2 reexpressed ERβ binds to the promoters of, and strongly down-regulates, the oncogenes MYB and MYC and up-regulates the differentiation factor RUNX2. These three transcription factors regulate a common target, CAV1, which as a result becomes up-regulated. The increased level of CAV1 inhibits the effect of IL-6 and, together with a robust down-regulation of IL-6, a network of IL-6-regulated genes is subsequently decreased. These genes have functions in inflammation, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. This is one example of a system biology approach that may reveal the order of events and network effects of ERβ expression. Another example is represented by one of the most strongly ERβ-down-regulated targets in SW480, the transcriptional factor and nuclear receptor coregulator PROX1. Figure 3, A and B, shows the nearly complete down-regulation of PROX1 mRNA upon expression of ERβ and the corresponding disappearance of the PROX1 protein. Comparison with a PROX1 silencing microarray study (24) revealed many shared genes, suggesting they are regulated as a result of ERβ-mediated PROX1 down-regulation. Cross-correlation with a PROX1 ChIP-on-chip dataset showed that many of these genes had a PROX1 chromatin-binding site nearby (25). Further, of the 69 regulated genes in our study that harbor an ERβ-binding site, 14 (20%) also have a PROX1-binding site. The expected genome-wide frequency of PROX1-binding sites is 12% (25). Statistical analysis proved this correlation of PROX1- and ERβ-binding sites to be significant (P value of 0.034). To confirm the occurrence of shared target genes, we performed a PROX1 ChIP on ERβ-expressing cells (low PROX1) and compared with control cells (high PROX1). We showed that PROX1 indeed binds to the chromatin less than 50 kb upstream from CITED2 transcription start site (Fig. 3C), whereas ERβ-binding site is approximately 150 kb upstream of transcription start site (22). Figure 3, C and D, show PROX1 ChIP data for the binding to CITED2 (panel C) and illustrate the resulting expression of genes with common chromatin-binding sites for both ERβ and PROX1 (panel D).

Fig. 3.

PROX1 is involved carcinogenesis and cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. PROX1 is down-regulated by ERβ in SW480 at protein (panel A) and mRNA (panel B) levels. C, PROX1 ChIP real-time PCR where samples are normalized to IgG. Primers for pS2 3′-untranslated region (UTR) are used as a negative control (Ctrl). There is a statistically significant reduction (unpaired one-tailed t test) of CITED2 binding in ERβ cells compared with the control cells (PROX1). D, Several differentially expressed genes have previously been defined to be regulated in the same direction when PROX1 is silenced, indicating that regulation of these genes results from the ERβ-driven down-regulation of PROX1 (I–III). In addition, several ERβ-regulated genes have been shown to have binding sites for both ERβ and PROX1 (IV). Proteins in red are transcriptionally up-regulated, as a consequence of ERβ expression described in our study and in agreement with a study by Petrova et al. (24), describing results of PROX1 silencing. Proteins in blue are transcriptionally down-regulated. Blue arrow, PROX1 transcriptional regulation. Dark green arrow with blue filling, PROX1 DNA binding and transcriptional regulation. Green arrow, ERβ DNA binding.

ERβ expression affects cell viability after DNA damage

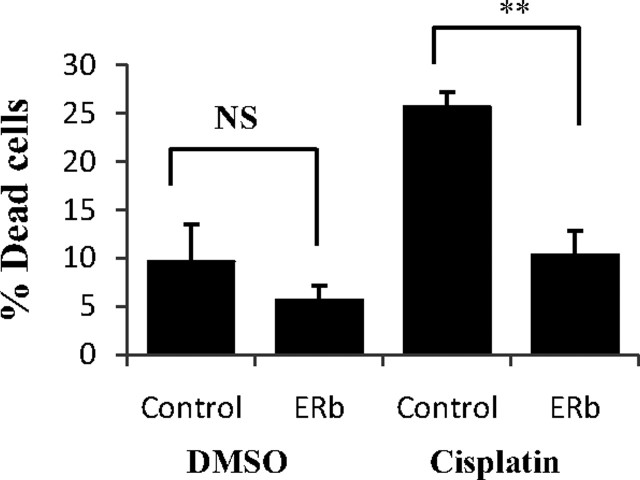

Apoptosis was an overrepresented theme among ERβ-regulated genes in all three cell lines. Table 3 summarizes genes changed for each cell line. An effect of ERβ on apoptosis could not previously be detected in xenografts of SW480 cells, using terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling assay (19). Additional cell-death assays in the current study confirmed that ERβ did not affect cell death in any of these three cell lines. However, our observed regulation of apoptosis genes, and recent results that ERβ affects apoptosis in breast cancer cells when the cells are triggered by cisplatin-induced DNA damage (26), prompted us to investigate whether ERβ expression affects the potential for apoptosis upon challenge. There was a significant change in viability by 15 percentage points between cisplatin-treated ERβ cells vs. cisplatin-treated control cells in the case of SW480 cells (Fig. 4). ERβ-expressing cells showed a lower percentage of dead cells compared with control cells (see Discussion). Thus, we demonstrate that upon challenge by cisplatin-induced DNA damage ERβ affects survival of SW480 colon cancer cells. The effect on cell death by cisplatin treatment was however absent in HCT-116 and HT29 cells.

Fig. 4.

Treatment (24 h) with cisplatin in SW480 control cells and ERβ-expressing cells. A higher percentage of attached control cells were dead after cisplatin treatment compared with ERβ-expressing cells, indicating that ERβ is protective against DNA damage in these colon cancer cells. The protective effect against DNA damage in ERβ cells is most likely a combination of lowered cell proliferation and increased DNA repair. DMSO. Dimethylsulfoxide; NS, nonsignificant (P = 0.201).

ERβ has previously been speculated to regulate DNA damage response (26). In our study, the gene ontology group ‘DNA repair’ was overrepresented among ERβ-regulated genes (Table 1). SW480 ERβ-expressing cells had higher levels of the double-stranded DNA-repair protein RAD51L3 as well as RRM2B [involved in p53-mediated DNA repair (27)]. HCT-116 cells are DNA repair-deficient (28) and HT29 cells have nonfunctional p53 and are less responsive to cisplatin (29). HT29 cells did, however, exhibit an ERβ-induced expression of LIG3, a key enzyme in double-stranded DNA repair. Thus, to further investigate the effect ERβ may have on survival in colon cells with functional mismatch repair and p53, we selected an additional colon cancer cell line with these characteristics, SW403. A transgenic transfection of ERβ in these cells, followed by cisplatin treatment, showed that a higher percentage of control cells died after the treatment compared with ERβ-transfected cells using this cell line (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Discussion

We noted three particularly exciting aspects of ERβ action in colon cancer cells: the effect on the MAPK pathways, the down-regulation of and cross talk with the nuclear receptor cofactor PROX1, and the down-regulation of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 network.

The subnetwork of MAPK1 was affected at the transcriptional level by ERβ in both HCT-116 and HT29. Estrogen has previously been shown to rapidly activate the MAPK/ERK pathway (30). Our results indicate that ERβ may also play a role in the regulation of the MAPK/ERK pathways. From our data, we cannot conclude whether ERβ activates or has a suppressive effect on MAPK1/3, but we see that ERβ expression has a transcriptional effect on targets downstream of MAPK1 phosphorylation. These genes have been shown previously to be transcriptionally altered after MAPK1 activation/inhibition. This indicates that ERβ expression changes the activity of MAPK1, which in turn changes phosphorylation status, and thereby activity, of MAPK1 target genes, leading to transcriptional changes of further downstream targets in this pathway. These results strongly indicate that ERβ exerts some of its transcriptional effects via the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Because the MAPK/ERK pathway drives a large proportion of colon cancers, an ERβ-mediated attenuation of this pathway would reduce the aggressiveness of the colon cancers.

PROX1 is a transcription factor frequently overexpressed in colon adenomas. In vivo overexpression of the protein leads to enhanced colon cancer progression whereas silencing of PROX1 significantly reduces the size and incidence of human colorectal tumor xenografts (24). To our knowledge, this is the first time ERβ has been reported to affect PROX1 expression, and it is plausible that the ERβ-driven down-regulation of PROX1 contributes to the antitumorigenic effects of ERβ observed in SW480 xenografts. PROX1 is a nuclear receptor coregulator, interacting with nuclear receptors via its N-terminal region, which contains two putative NR boxes (31). It has been shown to interact with several nuclear receptors such as COUP-TFII, LRH-1, HNF4α, and ERRα/PGC-1α (25, 32–35). Figure 3D shows the secondary effects of the ERβ-mediated down-regulation of PROX1, visualizing the DNA interactions of both ERβ and PROX1. We can organize these genes into four groups of regulated genes. Group I consists of genes that have PROX1 DNA-binding sites (25) and have previously been shown to be transcriptionally regulated by PROX1 (24). The regulation of these genes in our study is thus a direct consequence of the PROX1 down-regulation by ERβ. Group II consists of genes shown to be transcriptionally regulated when PROX1 is silenced, but which lack PROX1-DNA-binding sites. This group most likely consists of genes indirectly regulated by PROX1. Group III consists of genes that are transcriptionally regulated when PROX1 is silenced [in the absence of ERβ (24)] and harbor an ERβ-chromatin-binding site in the promoter region. Regulation of these genes in our study is likely a combined consequence of an indirect effect of PROX1 silencing and a direct up-regulating effect by ERβ. The last group, IV, consists of genes that have both PROX1- and ERβ-DNA-binding sites in their promoter regions. The regulation of these genes suggests that the two transcription factors compete or coregulate each other to influence the regulation of common targets. The combination of ERβ's down-regulatory effect on PROX1 and the function of PROX1 as a nuclear receptor coregulator allow for an intricate cross talk between the two transcription factors. Hence, the colon carcinogenic activity of PROX1 is affected by ERβ in dual ways; through down-regulation of PROX1 itself and through coregulation of the target genes.

The connection between inflammation and tumorigenesis is well established, and cytokines are important in all steps of colon tumorigenesis, including initiation, promotion, progression, and metastasis (36). IL-6 is produced at sites of inflammation and induces a transcriptional inflammatory response. It is active in colon cancer as a prosurvival and proangiogenic cytokine and also acts as a growth factor in premalignant enterocytes (37). We observed a complete down-regulation of IL-6 upon ERβ expression in SW480, along with 10 known IL-6-regulated gene targets. These genes are also known to participate in cell proliferation and/or apoptosis. Chronic intestinal inflammation precedes tumor development, and an ERβ-mediated down-regulation of IL-6 in normal colonic epithelia in vivo would substantially contribute to the suggested colon cancer-preventive effect of estrogen. This finding prompts further investigations to explore implications for preventive measures.

Using functional studies with a DNA-damaging agent, we noted an effect by ERβ on cell viability after DNA damage in SW480. Cisplatin-treated ERβ-expressing cells had a higher viability compared with control cells. We have previously shown that introduction of ERβ in SW480 significantly decreased proliferation. We interpret the protective effect of ERβ upon DNA damage in SW480 cells as a combination of decreased cell proliferation and increased DNA repair. Because cells that do not divide and cells that repair their DNA abolish the need for apoptosis, this combined effect increases the survival of ERβ-expressing cells. SW480 cells are DNA mismatch repair proficient (28) and despite a mutated p53 in these cells, many p53-associated pathways are still functional (38). The ERβ-induced down-regulation of MYC would further contribute to increased DNA repair, because MYC can disrupt the repair of double-stranded DNA breaks (39). The lack of effect on cell death after ERβ expression in HT29 and HCT-116 may be explained by the facts that these cells have defects in their DNA repair systems. This was explored further by analysis of another colon cancer cell line with functional p53 and mismatch repair, SW403. Also here ERβ had a protective effect against cell death induced by cisplatin. We suggest that ERβ interacts with the DNA repair and p53, resulting in a positive effect on DNA repair. Based on this observation, we propose that ERβ can work as a tumor suppressor by protecting colon cells from mutations through improved DNA repair, and hence against tumor progression in the early stages of colon cancer development. This is in line with the findings that estrogen can up-regulate the DNA mismatch repair gene hMLH1 in colon cancer cells (40) and that the protective actions of estrogen against colon cancer primarily occur during the initial stages of disease development (41).

This study sheds light on the transcriptional regulation by ERβ in human colon cancer cells and offers insights into ERβ's general mechanisms. Several previous studies of the transcriptional effects of ERβ have been performed under transient conditions in ERα-expressing breast cancer cells. Because ERβ often functions in relation to ERα and both receptors compete for binding sites and can form heterodimers with each other, it is difficult to study specific ERβ mechanisms while ERα is present. In the present investigation we use a system in which we can examine the stable transcriptional effects of ERβ homodimers alone. Among the genes detected in this study as regulated by ERβ, several have previously been shown to be transcriptionally regulated by ERα, frequently in the opposite direction [e.g. VEGFA, MYC, MYB, CD44, AREG, CEACAM1, ZNF217, CDC2, AHR, CITED2, EHF, CAV1, PRDX4, and ZFP36L2 (11, 42–44)]. Thus, the ERβ-mediated anti-ERα effect often observed in breast cancer is potentially a characteristic of ERβ itself and not solely dependent on its potentially inhibitory effect on ERα.

We did not observe any ligand-dependent gene-regulatory effect of ERβ. Ligand-independent activity of both estrogen receptors has been described in several studies (45–48). The mechanism behind ERβ ligand-independent activation is not well understood, but phosphorylation in the AF-1 domain of ERα has been shown to trigger ligand-independent activation (49), and this mechanism is plausible also for ERβ. In addition, studies have implied that MAPK/ERK can activate ERα in a ligand-independent manner (50). We speculate that the frequent ligand independence of ERβ observed in colon cancer cells may be due to the high MAPK/ERK phosphorylation activity. In nonmalignant colonocytes, however, an estrogen dose-dependent antiproliferative effect has been reported (41). Thus, there may be a difference regarding ERβ's ligand independence in normal vs. cancerous colon cells. In osteosarcoma cells, ERβ has been found to regulate some genes in a ligand-dependent manner and other genes in a ligand-independent manner (48). In colon cancer cells, however, only ligand independent effects have been detected (19, 46). We do not rule out the possibility that some of the ligand-independent effects are ligand dependent in normal colon. We hypothesize that ERβ is antitumorigenic in a ligand-mediated way in normal colonocytes and prestages of colon cancer, but may become ligand independent upon reexpression in colon cancer cell lines.

There were few genes identically regulated by ERβ in the three colon cancer cell lines. The three cell lines do express different levels of ERβ. However, levels of ERβ in SW480 and HT29 are relatively similar but still few genes are identically regulated. This indicates that the expression levels of ERβ are not solely responsible for the cell-specific differences in gene regulation. Cancer is a complex disease with differing genetic backgrounds and many separate, activated signaling pathways leading to the progression of disease, and therefore it is not surprising that there are large variations in gene regulation between different tumors or cancer cell lines. Identified differences between the three cell lines include mutations in p53, RAS, PROX1, and DNA repair genes. For example, HCT-116 cells do not express PROX1 mRNA and HT-29 cells have coding-region mutations of PROX1 (24); accordingly, the considerable downstream effects of ERβ-induced repression of PROX1 are lacking in these cells. Such mutations and presence/absence of different cofactors will play vital roles in the transcriptional effects induced by ERβ.

Concluding remarks

A wide repertoire of transcriptional changes was observed after reexpression of ERβ in colon cancer cells. These changes appear to increase differentiation and decrease proliferation and tumorigenic potential and would aid in preventing tumor progression. ERβ's antitumorigenic effect may be a combined result of regulation of the cell cycle, down-regulation of oncogenes such as MYC, MYB and PROX1, regulation of the antiinflammatory response, and increased DNA repair capacity. We speculate that tumors expressing ERβ are less aggressive compared with tumors that have lost their ERβ expression. Using ERβ as a prognostic marker in colon tumors may help to identify patients with a better prognosis and who would benefit from therapeutic approaches utilizing ERβ. We suggest that ERβ, at the gene-expression level, has related antitumorigenic effects in different colon cancers but that different genes and pathways operate to achieve these effects. Overall, our data strengthen the hypothesis that activation or reintroduction of ERβ is an important therapeutic approach for the prevention and/or treatment of colon cancer. Further, our findings are not only important in future clinical approaches but also provide a better understanding of the transcriptional regulation induced by ERβ.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and generation of stably ERβ-expressing cells

Cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Full-length ERβ was expressed via lentivirus transduction, with empty vector as control as previously described (19). SW403 was transfected in six-well plates with FuGENE (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) at a ratio of 3.0:1, according to conditions specified by the manufacturer. ERβ expression was confirmed at mRNA and protein levels using real-time PCR and Western blot. The ligand-binding and transcriptional-activating function of the protein was confirmed using estrogen-responsive element (ERE)-luciferase assay (Supplemental Fig. 3). The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37 C with 5% CO2, with the exception of SW403 cells that were cultured in 10% FBS. Twenty four hours before the experiments, the medium was changed to phenol red-free RPMI 1640 with 5% dextran-coated-charcoal-treated FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were treated with 10 nm estrogen or vehicle (EtOH) for 24 h in stripped medium.

ERE-luciferase assay

Transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with 100,000 seeded cells per 35-mm well and 1 μg of the ERE-TATA-LUC plasmid, in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). Five hours later the medium was changed to RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2% dextran-coated-charcoal-treated FBS ± 10 nm estrogen. Whole-cell lysates were harvested 24 h later, and luciferase activity was measured using Luciferase assay kit (BioThema, Handen, Sweden) in a Berthold FB12 luminometer (Labsystem, Gyeongbuk, Korea). Renilla luciferase was used as normalization control. Each transfection experiment was done in triplicates and presented as mean values (±sd).

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to standard protocol and purified with RNeasy spin columns (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA). On-column deoxyribonuclease I digestion was used to remove remaining genomic DNA. Quantitative and qualitative analyses of the RNA were performed with NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), respectively. All samples had an RNA integrity ≥9.3. cDNA was synthesized with Superscript III (Invitrogen) and random-hexamer primers.

Microarray experiment and analysis

We used a two-channel comparative technique, utilizing Operon's nucleotide arrays from Microarrays, Inc. (Huntsville, AL). In addition, the arrays were complemented with 133 oligos covering nuclear receptors, splice variants, and coregulators. Three independent sets of mixed clones were used for each cell line and condition. Each microarray comparison was replicated and dye swapped with different sets of mixed clones. ERβ-expressing cells were compared with control cells. To estimate gene expression changes induced by the lentiviral system itself, untransfected parental cells were compared with control cells. There were minor differences in gene expression between control cells and parental cells, which were adjusted for. Microarray analysis was performed as described previously (11). Differentially expressed genes, also close to cut off, could be confirmed by real-time PCR. Raw data and detailed protocols are available from the Array Express data repository using the accession number E-MEXP-3169.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed in a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with Fast SYBR-Green Master mix (Applied Biosystems) according to conditions specified by the manufacturer. All primer pairs were checked with melting curve analysis. Primer sequences will be provided on request. For real-time PCR analysis, unpaired two-tailed t test was used to compare differences between two parallel treatment groups of identical origin. Significance is presented as P <0.05 (*), <0.01 (**) or <0.001 (***).

Western blot analysis

For PROX1 Western blot, whole-cell extract was separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE, and blotting was performed according to standard protocols (51). For ERβ, whole-cell extract was first immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) before separation on SDS-PAGE. PROX1 antibody (07–537; Upstate Biotechnology, Inc, Lake Placid, NY) was used at 1:1000 dilution, ERβ (NBP1-04936, Novus biologicus) was used at a 1:1000-dilution, and β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 1:50,000. For PROX1 Western blot, donkey antirabbit IgG and sheep antimouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) were used at 1:10,000. For ERβ Western blot, rabbit antichicken IgY and sheep antimouse IgG (GE Healthcare Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) were used at 1:6000. Antibody binding was visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence, Super Signal (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL).

ChIP and real-time PCR

Cells were lysed by sonication on a Diagenode Bioruptor UCD200 (Diagenode, Liege, Belgium; 70 cycles of 30 sec on/30 sec off on high setting). Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen) overnight. Each reaction used 5 μl of bead together with 1 μg anti-PROX1 antibody (Upstate). Rabbit IgG (1 μg, Santa Cruz) was used as control. Immunoprecipitated chromatin and whole-cell extract samples were incubated overnight at 65 C. DNA was purified on a MinElute column (QIAGEN) using the PCR purification protocol as specified by manufacturer. Whole-cell extract samples were diluted 1:50, and real-time PCR was performed with 2 μl of DNA and Fast SYBR-Green Master mix (Applied Biosystems) as specified by manufacturer. Primer sequences will be provided on request.

Cell death and apoptosis assay

To investigate the effect of ERβ on cell-death, 2 × 105 ERβ-expressing or control cells were plated on six-well culture dishes. After 72 h, the cells were stained with trypan blue and counted with the automated cell counter Countess (Invitrogen). Experiments were performed with three different clone mixes for each transduction. To study the apoptotic potential as induced by DNA-damaging agent, cells were treated in triplicates for 24 h with [cisplatin (cis-Diammineplatinum(II) dichloride] (Sigma-Aldrich) with a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Cells were subsequently stained with trypan blue and counted as above.

Bioinformatics

Ariadne Pathway Studio 7.1 was used to facilitate the biological interpretation of microarray data. Fischer's exact test was used to define enriched Gene Ontology functional groups among differentially expressed genes. Sub-Network Enrichment Analysis (SNEA) algorithm was used to find subnetworks of key regulators, targets, and binding partners in our list of differentially expressed genes. SNEA uses experimental data from differentially expressed genes and information extracted from literature to find downstream neighbors to an individual protein (seed protein). An enriched subnetwork can consist of both differentially up-regulated and down-regulated genes. Because downstream targets of the seed protein are enriched, it is assumed that the seed protein is one of the key regulators. Results with P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. To examine whether any of the genes were direct targets of ERβ, we compared our list of differentially expressed genes with the results from an ERβ binding ChIP-on-chip assay in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Further, comparisons between our list of differentially expressed genes and those from a PROX1 ChIP-on-chip study were made to identify genes regulated by PROX1. A Chi-square test with expected frequencies was used to determine statistical significance of comparisons between our microarray data and the ChIP studies, where P < 0.005 is considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chin-Yo Lin, Center for Nuclear Receptors and Cell Signaling, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by The Texas Emerging Technology Fund, under Agreement no. 300-9-1958, and by grants from Lars Hierta's Memorial Foundation, the Magnus Bergvall's Foundation, the Swedish Cancer Society, and the Robert A. Welch Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: K.E., A.S., P.J., and C.W. have nothing to declare. J.Å.G. is a stockholder and consultant of Karo Bio AB and is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of BioNovo, Inc.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Nuclear Receptors: ER-β;

Coregulators: PROX1 | CAV1.

Footnotes

- ChIP

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- ERE

- estrogen-responsive element

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum.

References

- 1. Grodstein F , Newcomb PA , Stampfer MJ. 1999. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and the risk of colorectal cancer: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 106:574–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Newcomb PA , Zheng Y , Chia VM , Morimoto LM , Doria-Rose VP , Templeton A , Thibodeau SN , Potter JD. 2007. Estrogen plus progestin use, microsatellite instability, and the risk of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Res 67:7534–7539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park BW , Kim KS , Heo MK , Ko SS , Hong SW , Yang WI , Kim JH , Kim GE , Lee KS. 2003. Expression of estrogen receptor-β in normal mammary and tumor tissues: is it protective in breast carcinogenesis? Breast Cancer Res Treat 80:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pasquali D , Staibano S , Prezioso D , Franco R , Esposito D , Notaro A , De Rosa G , Bellastella A , Sinisi AA. 2001. Estrogen receptor β expression in human prostate tissue. Mol Cell Endocrinol 178:47–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rutherford T , Brown WD , Sapi E , Aschkenazi S , Muñoz A , Mor G. 2000. Absence of estrogen receptor-beta expression in metastatic ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol 96:417–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hartman J , Lindberg K , Morani A , Inzunza J , Ström A , Gustafsson JA. 2006. Estrogen receptor β inhibits angiogenesis and growth of T47D breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res 66:11207–11213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murphy LC , Peng B , Lewis A , Davie JR , Leygue E , Kemp A , Ung K , Vendetti M , Shiu R. 2005. Inducible upregulation of oestrogen receptor-β1 affects oestrogen and tamoxifen responsiveness in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. J Mol Endocrinol 34:553–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ström A , Hartman J , Foster JS , Kietz S , Wimalasena J , Gustafsson JA. 2004. Estrogen receptor β inhibits 17β-estradiol-stimulated proliferation of the breast cancer cell line T47D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:1566–1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang EC , Frasor J , Komm B , Katzenellenbogen BS. 2006. Impact of estrogen receptor β on gene networks regulated by estrogen receptor α in breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 147:4831–4842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paruthiyil S , Parmar H , Kerekatte V , Cunha GR , Firestone GL , Leitman DC. 2004. Estrogen receptor β inhibits human breast cancer cell proliferation and tumor formation by causing a G2 cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res 64:423–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams C , Edvardsson K , Lewandowski SA , Ström A , Gustafsson JA. 2008. A genome-wide study of the repressive effects of estrogen receptor β on estrogen receptor α signaling in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 27:1019–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Konstantinopoulos PA , Kominea A , Vandoros G , Sykiotis GP , Andricopoulos P , Varakis I , Sotiropoulou-Bonikou G , Papavassiliou AG. 2003. Oestrogen receptor β (ERβ) is abundantly expressed in normal colonic mucosa, but declines in colon adenocarcinoma paralleling the tumour's dedifferentiation. Eur J Cancer 39:1251–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jassam N , Bell SM , Speirs V , Quirke P. 2005. Loss of expression of oestrogen receptor β in colon cancer and its association with Dukes' staging. Oncol Rep 14:17–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nüssler NC , Reinbacher K , Shanny N , Schirmeíer A , Glanemann M , Neuhaus P , Nussler AK , Kirschner M. 2008. Sex-specific differences in the expression levels of estrogen receptor subtypes in colorectal cancer. Gend Med 5:209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foley EF , Jazaeri AA , Shupnik MA , Jazaeri O , Rice LW. 2000. Selective loss of estrogen receptor β in malignant human colon. Cancer Res 60:245–248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giroux V , Lemay F , Bernatchez G , Robitaille Y , Carrier JC. 2008. Estrogen receptor β deficiency enhances small intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice. Int J Cancer 123:303–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giroux V , Bernatchez G , Carrier JC. 2011. Chemopreventive effect of ERβ-selective agonist on intestinal tumorigenesis in Apc(Min/+) mice. Mol Carcinog 50:359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deroo BJ , Buensuceso AV. 2010. Minireview: Estrogen receptor-β: mechanistic insights from recent studies. Mol Endocrinol 24:1703–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hartman J , Edvardsson K , Lindberg K , Zhao C , Williams C , Ström A , Gustafsson JA. 2009. Tumor repressive functions of estrogen receptor β in SW480 colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 69:6100–6106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Milanini-Mongiat J , Pouysségur J , Pagès G. 2002. Identification of two Sp1 phosphorylation sites for p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases: their implication in vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription. J Biol Chem 277:20631–20639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Förster C , Mäkela S , Wärri A , Kietz S , Becker D , Hultenby K , Warner M , Gustafsson JA. 2002. Involvement of estrogen receptor β in terminal differentiation of mammary gland epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:15578–15583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhao C , Gao H , Liu Y , Papoutsi Z , Jaffrey S , Gustafsson JA , Dahlman-Wright K. 2010. Genome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor-β-binding regions reveals extensive cross-talk with transcription factor activator protein-1. Cancer Res 70:5174–5183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rayoo M , Yan M , Takano EA , Bates GJ , Brown PJ , Banham AH , Fox SB. 2009. Expression of the forkhead box transcription factor FOXP1 is associated with oestrogen receptor α, oestrogen receptor β and improved survival in familial breast cancers. J Clin Pathol 62:896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Petrova TV , Nykänen A , Norrmén C , Ivanov KI , Andersson LC , Haglund C , Puolakkainen P , Wempe F , von Melchner H , Gradwohl G , Vanharanta S , Aaltonen LA , Saharinen J , Gentile M , Clarke A , Taipale J , Oliver G , Alitalo K. 2008. Transcription factor PROX1 induces colon cancer progression by promoting the transition from benign to highly dysplastic phenotype. Cancer Cell 13:407–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Charest-Marcotte A , Dufour CR , Wilson BJ , Tremblay AM , Eichner LJ , Arlow DH , Mootha VK , Giguère V. 2010. The homeobox protein Prox1 is a negative modulator of ERRα/PGC-1α bioenergetic functions. Genes Dev 24:537–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas CG , Strom A , Lindberg K , Gustafsson JA. 10 July 2010. Estrogen receptor β decreases survival of p53-defective cancer cells after DNA damage by impairing G(2)/M checkpoint signaling. Breast Cancer Res Treat 10.1007/s10549-010-1011-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Byun DS , Chae KS , Ryu BK , Lee MG , Chi SG. 2002. Expression and mutation analyses of P53R2, a newly identified p53 target for DNA repair in human gastric carcinoma. Int J Cancer 98:718–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parsons R , Li GM , Longley MJ , Fang WH , Papadopoulos N , Jen J , de la Chapelle A , Kinzler KW , Vogelstein B , Modrich P. 1993. Hypermutability and mismatch repair deficiency in RER+ tumor cells. Cell 75:1227–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fernández de Mattos S , Villalonga P , Clardy J , Lam EW. 2008. FOXO3a mediates the cytotoxic effects of cisplatin in colon cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 7:3237–3246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Razandi M , Pedram A , Park ST , Levin ER. 2003. Proximal events in signaling by plasma membrane estrogen receptors. J Biol Chem 278:2701–2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steffensen KR , Holter E , Båvner A , Nilsson M , Pelto-Huikko M , Tomarev S , Treuter E. 2004. Functional conservation of interactions between a homeodomain cofactor and a mammalian FTZ-F1 homologue. EMBO Rep 5:613–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee S , Kang J , Yoo J , Ganesan SK , Cook SC , Aguilar B , Ramu S , Lee J , Hong YK. 2009. Prox1 physically and functionally interacts with COUP-TFII to specify lymphatic endothelial cell fate. Blood 113:1856–1859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qin J , Gao DM , Jiang QF , Zhou Q , Kong YY , Wang Y , Xie YH. 2004. Prospero-related homeobox (Prox1) is a corepressor of human liver receptor homolog-1 and suppresses the transcription of the cholesterol 7-α-hydroxylase gene. Mol Endocrinol 18:2424–2439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Song KH , Li T , Chiang JY. 2006. A Prospero-related homeodomain protein is a novel co-regulator of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α that regulates the cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene. J Biol Chem 281:10081–10088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yamazaki T , Yoshimatsu Y , Morishita Y , Miyazono K , Watabe T. 2009. COUP-TFII regulates the functions of Prox1 in lymphatic endothelial cells through direct interaction. Genes Cells 14:425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Terzić J , Grivennikov S , Karin E , Karin M. 2010. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology 138:2101–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karin M , Greten FR. 2005. NF-κB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Immunol 5:749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rochette PJ , Bastien N , Lavoie J , Guérin SL , Drouin R. 2005. SW480, a p53 double-mutant cell line retains proficiency for some p53 functions. J Mol Biol 352:44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Karlsson A , Deb-Basu D , Cherry A , Turner S , Ford J , Felsher DW. 2003. Defective double-strand DNA break repair and chromosomal translocations by MYC overexpression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:9974–9979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jin P , Lu XJ , Sheng JQ , Fu L , Meng XM , Wang X , Shi TP , Li SR , Rao J. 2010. Estrogen stimulates the expression of mismatch repair gene hMLH1 in colonic epithelial cells. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 3:910–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weige CC , Allred KF , Allred CD. 2009. Estradiol alters cell growth in nonmalignant colonocytes and reduces the formation of preneoplastic lesions in the colon. Cancer Res 69:9118–9124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frasor J , Danes JM , Komm B , Chang KC , Lyttle CR , Katzenellenbogen BS. 2003. Profiling of estrogen up- and down-regulated gene expression in human breast cancer cells: insights into gene networks and pathways underlying estrogenic control of proliferation and cell phenotype. Endocrinology 144:4562–4574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lin CY , Ström A , Vega VB , Kong SL , Yeo AL , Thomsen JS , Chan WC , Doray B , Bangarusamy DK , Ramasamy A , Vergara LA , Tang S , Chong A , Bajic VB , Miller LD , Gustafsson JA , Liu ET. 2004. Discovery of estrogen receptor α target genes and response elements in breast tumor cells. Genome Biol 5:R66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Soulez M , Parker MG. 2001. Identification of novel oestrogen receptor target genes in human ZR75–1 breast cancer cells by expression profiling. J Mol Endocrinol 27:259–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lazennec G , Bresson D , Lucas A , Chauveau C , Vignon F. 2001. ER β inhibits proliferation and invasion of breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 142:4120–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Martineti V , Picariello L , Tognarini I , Carbonell Sala S , Gozzini A , Azzari C , Mavilia C , Tanini A , Falchetti A , Fiorelli G , Tonelli F , Brandi ML. 2005. ERβ is a potent inhibitor of cell proliferation in the HCT8 human colon cancer cell line through regulation of cell cycle components. Endocr Relat Cancer 12:455–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tremblay A , Giguère V. 2001. Contribution of steroid receptor coactivator-1 and CREB binding protein in ligand-independent activity of estrogen receptor β. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 77:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vivar OI , Zhao X , Saunier EF , Griffin C , Mayba OS , Tagliaferri M , Cohen I , Speed TP , Leitman DC. 2010. Estrogen receptor β binds to and regulates three distinct classes of target genes. J Biol Chem 285:22059–22066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thomas RS , Sarwar N , Phoenix F , Coombes RC , Ali S. 2008. Phosphorylation at serines 104 and 106 by Erk1/2 MAPK is important for estrogen receptor-α activity. J Mol Endocrinol 40:173–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Atanaskova N , Keshamouni VG , Krueger JS , Schwartz JA , Miller F , Reddy KB. 2002. MAP kinase/estrogen receptor cross-talk enhances estrogen-mediated signaling and tumor growth but does not confer tamoxifen resistance. Oncogene 21:4000–4008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harlow E , Lane D. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- 52. Asham E , Shankar A , Loizidou M , Fredericks S , Miller K , Boulos PB , Burnstock G , Taylor I. 2001. Increased endothelin-1 in colorectal cancer and reduction of tumour growth by ET(A) receptor antagonism. Br J Cancer 85:1759–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Galbiati F , Volonté D , Liu J , Capozza F , Frank PG , Zhu L , Pestell RG , Lisanti MP. 2001. Caveolin-1 expression negatively regulates cell cycle progression by inducing G(0)/G(1) arrest via a p53/p21(WAF1/Cip1)-dependent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell 12:2229–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zeng ZS , Shu WP , Cohen AM , Guillem JG. 2002. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 expression in colorectal cancer liver metastases: evidence for involvement of MMP-7 activation in human cancer metastases. Clin Cancer Res 8:144–148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gongoll S , Peters G , Mengel M , Piso P , Klempnauer J , Kreipe H , von Wasielewski R. 2002. Prognostic significance of calcium-binding protein S100A4 in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 123:1478–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sun L , Fu BB , Liu DG. 2005. Systemic delivery of full-length C/EBP β/liposome complex suppresses growth of human colon cancer in nude mice. Cell Res 15:770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fujiya M , Watari J , Ashida T , Honda M , Tanabe H , Fujiki T , Saitoh Y , Kohgo Y. 2001. Reduced expression of syndecan-1 affects metastatic potential and clinical outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Jpn J Cancer Res 92:1074–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Herynk MH , Stoeltzing O , Reinmuth N , Parikh NU , Abounader R , Laterra J , Radinsky R , Ellis LM , Gallick GE. 2003. Down-regulation of c-Met inhibits growth in the liver of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 63:2990–2996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nishimura T , Andoh A , Inatomi O , Shioya M , Yagi Y , Tsujikawa T , Fujiyama Y. 2008. Amphiregulin and epiregulin expression in neoplastic and inflammatory lesions in the colon. Oncol Rep 19:105–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nittka S , Günther J , Ebisch C , Erbersdobler A , Neumaier M. 2004. The human tumor suppressor CEACAM1 modulates apoptosis and is implicated in early colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncogene 23:9306–9313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rooney PH , Boonsong A , McFadyen MC , McLeod HL , Cassidy J , Curran S , Murray GI. 2004. The candidate oncogene ZNF217 is frequently amplified in colon cancer. J Pathol 204:282–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang S , Liu H , Ren L , Pan Y , Zhang Y. 2008. Inhibiting colorectal carcinoma growth and metastasis by blocking the expression of VEGF using RNA interference. Neoplasia 10:399–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zeelenberg IS , Ruuls-Van Stalle L , Roos E. 2003. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is required for outgrowth of colon carcinoma micrometastases. Cancer Res 63:3833–3839 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zeng M , Kikuchi H , Pino MS , Chung DC. 2010. Hypoxia activates the K-ras proto-oncogene to stimulate angiogenesis and inhibit apoptosis in colon cancer cells. PLoS One 5:e10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]