Synthetic FXR agonist GW4064 activates ERR proteins and through ERRα regulates PGC-1α expression. Further, FXR physically interacts with ERR and protects it from SHP repression.

Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) is induced in energy-starved conditions and is a key regulator of energy homeostasis. This makes PGC-1α an attractive therapeutic target for metabolic syndrome and diabetes. In our effort to identify new regulators of PGC-1α expression, we found that GW4064, a widely used synthetic agonist for the nuclear bile acid receptor [farnesoid X receptor (FXR)] strongly enhances PGC-1α promoter reporter activity, mRNA, and protein expression. This induction in PGC-1α concomitantly enhances mitochondrial mass and expression of several PGC-1α target genes involved in mitochondrial function. Using FXR-rich or FXR-nonexpressing cell lines and tissues, we found that this effect of GW4064 is not mediated directly by FXR but occurs via activation of estrogen receptor-related receptor α (ERRα). Cell-based, biochemical and biophysical assays indicate GW4064 as an agonist of ERR proteins. Interestingly, FXR disruption alters GW4064 induction of PGC-1α mRNA in a tissue-dependent manner. Using FXR-null [FXR knockout (FXRKO)] mice, we determined that GW4064 induction of PGC-1α expression is not affected in oxidative soleus muscles of FXRKO mice but is compromised in the FXRKO liver. Mechanistic studies to explain these differences revealed that FXR physically interacts with ERR and protects them from repression by the atypical corepressor, small heterodimer partner in liver. Together, this interplay between ERRα-FXR-PGC-1α and small heterodimer partner offers new insights into the biological functions of ERRα and FXR, thus providing a knowledge base for therapeutics in energy balance-related pathophysiology.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) is a transcriptional coactivator that is enriched in tissues with high energy demand, such as brown fat, “slow-twitch” oxidative skeletal muscles, and heart (1–3). Unlike most of the constitutively expressed coactivators, PGC-1α expression is inducible by exercise, fasting, or exposure to cold (4). PGC-1α has been implicated in the regulation of fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial respiratory function, glucose utilization, and hepatic gluconeogenesis (5, 6).

Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) regulates a multitude of genes in bile acid biosynthesis and transport, including the rate-limiting enzyme for bile acid biosynthesis, cholesterol-7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) (7). FXR interacts with PGC-1α and mediates PGC-1α actions in hepatic gluconeogenesis and lipid metabolism (8–10). Due to its importance in glucose and lipid homeostasis, FXR is considered a promising therapeutic target. GW4064, a synthetic FXR ligand (11, 12), has been reported to ameliorate lithogenic diet-induced cholesterol gallstone disease in mice (13) and favorably affect glucose and lipid homeostasis in obesity and diabetes (8). Due to poor bioavailability, the promise of GW4064 as a candidate drug is diminished. However, it is extensively used as a reference compound to deduce FXR function since the past decade. Studies on the mechanism of FXR action have revealed that a part of the FXR action is mediated by induction of the atypical corepressor small heterodimer partner (SHP) (11, 14), which binds to coactivator binding surface of a number of nuclear receptors and recruits corepressor complex proteins (15).

The estrogen receptor-related receptors (ERR) that include ERRα, ERR-β, and ERR-γ also interact with PGC-1α (16–18). ERRα in particular mediates a number of PGC-1α functions, such as regulation of mitochondrial mass, function, and hepatic glucose oxidation (16). FXR, PGC-1α, ERR, and SHP share a common tissue distribution and are found in liver, kidney, stomach, and intestine (19), although ERR are also enriched in other PGC-1α-expressing tissues, including brown fat, skeletal muscle, and heart (19).

The present study was designed to identify and characterize new regulators of PGC-1α expression. From our screening, we identified GW4064, a well-known synthetic agonist of FXR as a regulator of PGC-1α expression. We demonstrate that this PGC-1α induction is mediated through ERRα, and GW4064 is an agonist for all ERR isoforms. Further, we show that FXR via physical interaction with ERRα contributes to hepatic PGC-1α regulation. Given that FXR is important for cholesterol and carbohydrate metabolism and ERR are principal to energy homeostasis, our findings suggest that these physiologically related but distinct pathways converge through this ERR and FXR interplay.

Results

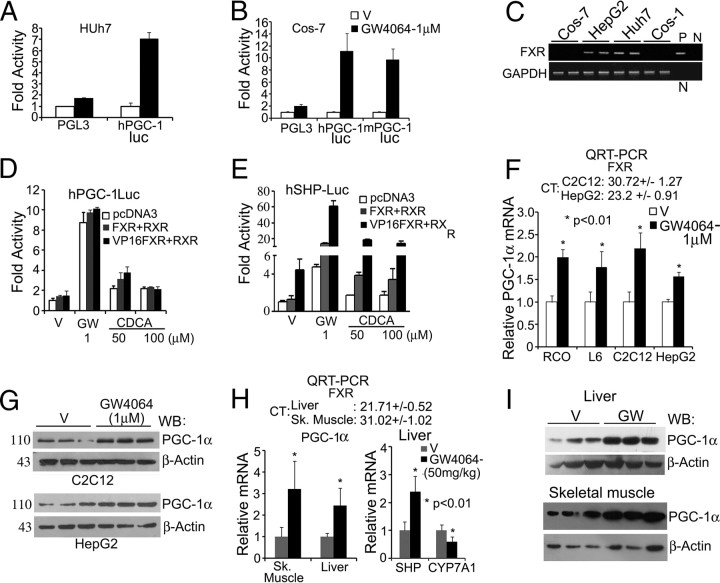

FXR-independent induction of PGC-1α by GW4064

To identify new factors regulating PGC-1α expression, 2.6-kb mouse PGC-1α and 1-kb human PGC-1α promoter reporters (mouse PGC-1luc and human PGC-1luc) were screened in Huh7 hepatoma cells using commercially available ligands for various nuclear receptors. Among the compounds tested, FXR agonist GW4064 strongly induced the reporter activities (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, GW4064 also activated PGC-1luc in COS-7 cells (Fig. 1B), which were used as a negative control in secondary screening, because they do not express FXR (Fig. 1C) (20). Moreover, chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), a natural FXR ligand, failed to activate PGC-1luc (Fig. 1D). Introduction of FXR or FXR fused to herpes simplex virus protein VP16 activation domain (VP16FXR) failed to augment basal or GW4064 induction of PGC-1luc activity (Fig. 1D), whereas they strongly enhanced a SHP promoter reporter (SHP-luc) (Fig. 1E). Further, 9-cis retinoic acid had no effect on GW4064 activation of PGC-1luc (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). These results indicate that the GW4064 effect on PGC-1luc may be FXR independent. Interestingly, GW4064 also activated SHP-luc in Cos-7 cells in the absence of exogenous FXR, and this activation was equivalent to the activity of VP16FXR in absence of FXR ligand (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

GW4064 activates PGC-1α promoter reporter and induces its expression in cell and in vivo. A and B, GW4064 activates PGC-1luc in Huh7 (A) and Cos-7 cells (B). Cells were transfected with indicated plasmids and treated for 24 h. After lysis, luciferase activities were determined, normalized with GFP fluorescence, and plotted as fold activity over vehicle-treated PGL3-basic transfected controls. C, Relative expression levels of FXR in indicated cell lines as detected by RT-PCR. All primer information is provided in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. D, Exogenous FXR fails to augment GW4064 activity on PGC-1luc. E, Exogenous FXR enhances GW4064 activation of SHP-luc. Reporter assays were performed in Cos-7 cells as in A, and data are plotted as fold activity over vehicle-treated controls. Data represent mean ± sd from three independent experiments. F, GW4064 induces PGC-1α expression; 24 h after treatment of indicated cell lines with vehicle (V) or 1 μm GW4064, QRT-PCR were performed. Data represent mean ± sem from three independent experiments. Average FXR CT values from three independent QRT-PCR are shown at the top. H, GW4064 induces PGC-1α expression in vivo. Eight-wk-old male BALB/C mice were fed once with vehicle (gum acacia; n =5) or GW4064 (50 mg/kg body weight in gum acacia; n =6). After 24 h, RNA was extracted from liver and pooled hind limb skeletal muscle, and QRT-PCR was performed in triplicates. Top panel shows average CT values for FXR mRNA. G and I, GW4064 induces PGC-1α protein expression as detected by immunoblotting. RCO, Rat calvarial osteoblasts; P, plasmid control; n, negative control; GW, GW4064; WB, Western blot; Sk., skeletal.

Next, the effect of GW4064 on PGC-1α mRNA expression was investigated in a number of cell lines that express endogenous PGC-1α (we did not detect PGC-1α in Huh7 and Cos cells). GW4064 significantly induced PGC-1α mRNA in HepG2 cells, which are known to express relatively high amounts of FXR. GW4064 also induced PGC-1α mRNA in L6, C2C12 myocytes, and primary rat calvarial osteoblasts (Fig. 1F), which we assumed to be lacking FXR, because earlier studies did not detect FXR expression in skeletal muscle and bone (19). Further, GW4064 induced PGC-1α protein expression in both C2C12 and HepG2 (Fig. 1G). These results indicate that GW4064 activates PGC-1α promoter and induces its expression in both FXR-nonexpressing and FXR-rich cells. Consistent with mitochondrial role of PGC-1α, GW4064 enhanced mitochondrial mass and activity in C2C12 cells (Supplemental Fig. 2). The induction of PGC-1α by GW4064 was replicated in vivo. GW4064 significantly enhanced PGC-1α mRNA and protein in both liver (FXR-rich) and skeletal muscles (does not express FXR) of BALB/C mice (Fig. 1, H and I) and, as expected, induced SHP and suppressed CYP7A1 mRNA in liver (Fig. 1H).

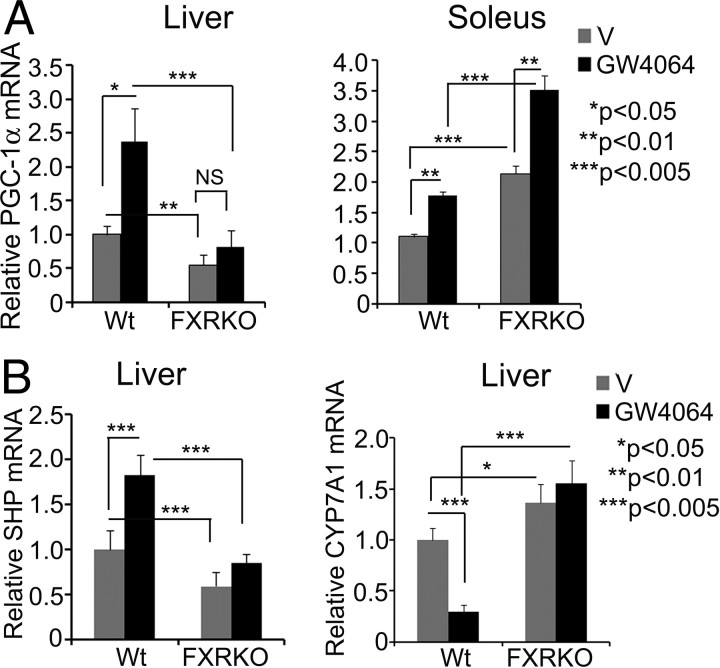

FXR differentially contributes to PGC-1α expression in liver and skeletal muscles

Although GW4064 activated PGC-1luc independent of FXR and induced PGC-1α mRNA in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 1), the reported alterations of PGC-1α expression in liver of fed, short-term- and long-term-fasted FXR knockout (FXRKO) mice (21, 22), and a tendency for increased PGC-1α expression in FXRKO skeletal muscle (23), prompted us to examine the role of FXR in regulation of PGC-1α in liver and skeletal muscle. FXRKO or wild type (WT) mice were administrated GW4064 by oral gavage, and gene expression analyses were performed in liver and type I “slow-twitch” fiber-enriched soleus muscle (soleus muscle was chosen, because it exhibits high energy demand, and therefore, PGC-1α plays a critical role in this tissue). Consistent with previous reports (21, 23), FXR disruption strongly suppressed basal PGC-1α expression in fed liver, whereas PGC-1α expression in soleus muscles was increased (Fig. 2A). Intriguingly, FXR disruption eliminated the GW4064 induction of hepatic PGC-1α, which is contrary to our finding in Fig. 1 that GW4064 induction of PGC-1 is FXR independent. However, in soleus muscle of FXRKO mice, GW4064 induction of PGC-1α expression was maintained (Fig. 2A). As expected, GW4064 induced SHP and repressed CYP7A1 expression in WT but not in FXRKO liver.

Fig. 2.

PGC-1α induction by GW4064 is FXR dependent in liver but independent in skeletal muscle. A and B, Ten- to 12-wk-old FXRKO or age- and sex-matched WT mice were given GW4064 or vehicle (V) by oral gavage (50 mg/kg body weight) for 3 d (WT: V, n = 3; GW4064, n = 4; FXRKO: V, n = 3; GW4064, n = 4). To eliminate fasting-mediated PGC-1α induction, animals were killed under fed condition. Total RNA was isolated from indicated tissues, and QRT-PCR was performed in triplicates. Data represent mean ± sem and are plotted as fold change over vehicle-treated WT controls.

Together, these results demonstrate that GW4064 induction of PGC-1α may occur through FXR-independent pathways both in vitro and in vivo; however, FXR contributes to this effect in liver. Further, because SHP-luc was also activated by GW4064 in absence of FXR in Cos-7 cells (Fig. 1E), it appears that this FXR-independent effect probably is mediated through a common factor that regulates both SHP and PGC-1α expression.

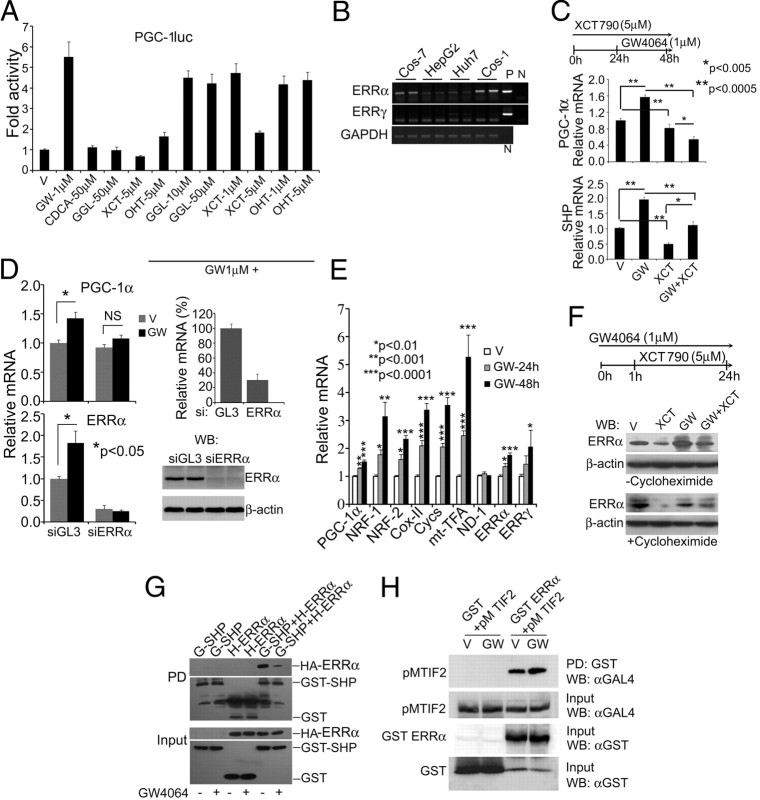

GW4064 induction of PGC-1α expression is routed through ERRα

ERR regulate both PGC-1α and SHP promoters (24, 25) and share similar tissue distribution and induction pattern with PGC-1α (16, 26). Therefore, we examined whether GW4064 induction of PGC-1α occurs through ERR. In Cos-7 reporter assays, XCT790 (Fig. 3A), an ERRα inverse agonist (27), reduced basal PGC-1α luc activity and abolished the GW4064 induction of this reporter. However, ERRγ inverse agonist, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (OHT) (28) or guggulsterone (that in addition to being an FXR antagonist affects multiple nuclear receptors) (29, 30), failed to affect GW4064-mediated PGC-1α luc activity (Fig. 3A). Guggulsterone successfully inhibited the activity of pMFXR on a luciferase reporter driven by yeast GAL4 response element (Gal-luc) (Supplemental Fig. 3), and XCT790 did not affect pMFXR activity on Gal-luc (Supplemental Fig. 4). Gene expression analysis revealed ERRα but not ERRγ expression in Cos, Huh7, and HepG2 (Fig. 3B). We also found strong ERRα expression in all the cell lines and tissues where GW4064 induction of PGC-1α mRNA was observed by RT-PCR (Fig. 3B) or quantitative RT-PCR (QRT-PCR) [cycle threshold (CT) values for ERRα, HepG2: 24.29 ± 0.26; C2C12: 23.48 ± 0.62; liver: 25.85 ± 0.92; skeletal muscle: 26.80 ± 1.15]. These results suggest that GW4064 induction of PGC-1α may occur through ERRα.

Fig. 3.

GW4064-mediated PGC-1α up-regulation occurs via ERRα. A, XCT790 represses GW4064 activation of PGC-1luc. Cos-7 cells were transfected and treated as indicated. In cotreatment experiments, GW4064 treatment was preceded by 1-h treatment with indicated inhibitors. Cells were processed as in Fig. 1A. Data represent mean ± sd from three independent experiments. B, mRNA Expression of ERRα. Total RNA was isolated from indicated cell lines, RT-PCR was performed and resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. P, Plasmid control, N, no DNA. C, XCT790 represses basal or GW4064-induced PGC-1α and SHP expression. HepG2 cells were treated with GW4064 and/or XCT790 as illustrated and were analyzed by QRT-PCR. Data represent mean ± sem from three independent experiments done in triplicates. D, ERRα depletion compromises GW4064 induction of PGC-1α and ERRα mRNA. HepG2 cells were transfected with ERRa or control (siPGL3) siRNA; 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 1 μm GW4064 for a further 24 h. Cells were then lysed, and QRT-PCR were performed. Data represent mean ± sem from three independent experiments. Inset shows percent ERRα knockdown (upper panel) and ERRα protein level after 72 h of siRNA transfection is shown (lower panel). E, GW4064 induces ERRα targets in C2C12 myocytes. C2C12 myocytes were treated with 1 μm GW4064 as indicated, and QRT-PCR were performed. Data represent mean ± sem from at least six independent experiments. F, Reduction of ERRα protein stability by XCT790 is reversed by GW4064. Cos-7 cells were treated as illustrated. For cycloheximide treatment, 10 μm cycloheximide was added 2 h before GW4064 treatment. A representative Western blotting of three independent experiments is shown. G, GW4064 reduces ERRα-SHP interaction in Cos-7 cells. In-cell GST pull-down assay. After transfection with mammalian GST expression plasmid expressing GST-SHP (pEBGSHP) and a plasmid encoding HAERRα, and indicated treatments, whole-cell extracts were immobilized on glutathione sepharose beads and analyzed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. Data represent one of two independent experiments. G-SHP, pEBGSHP; H-ERRα, HAERRα. H, GW4064 enhances ERRa-TIF-2 (transcription intermediary factor-2) interaction. As demonstrated above, in-cell GST pull-down assay was performed and detected with indicated antibodies. Data are representative of two independent experiments. V, Vehicle; GW, GW4064; WB, Western blot.

Because XCT790 degrades ERRα protein (27), we studied the effect of XCT790-mediated depletion of endogenous ERRα in GW4064 regulation of endogenous PGC-1α and SHP in HepG2 cells. XCT790 significantly reduced both basal and GW4064-induced expressions of PGC-1α and SHP (Fig. 3C). Further, XCT790 repression of GW4064 activity on PGC-1luc could be rescued with the introduction of exogenous ERRα (Supplemental Fig. 5), indicating that the observed GW4064 effect on PGC-1α expression may solely be through ERRα. This finding was further substantiated using an RNAi approach. As demonstrated in Fig. 3D, GW4064 induction of PGC-1α as well as ERRα (which is autoregulated by ERRα) was abolished in presence of ERRα small interfering RNA (siRNA). This finding was also substantiated in FXR-nonexpressing C2C12 cells, where GW4064 induced mRNA levels of a number of genes involved in mitochondrial functions that also are validated ERRα targets (31, 32), including cytochrome C somatic, nuclear respiratory factor (NRF)-2 (NRF-2), and ERRα (Fig. 3E). Consistent with PGC-1α induction, GW4064 also induced validated PGC-1α targets (33), NRF-1, mitochondrial transcription factor (mt-TFA), and cytochrome C oxidase II (COX-II) (Fig. 3E).

We next studied the effect of GW4064 on XCT790 degradation of ERRα in Cos-7 cells, because it expresses endogenous ERRα but not FXR. As shown in Fig. 3F, XCT790 strongly depleted endogenous ERRα protein in Cos-7 cells, whereas GW4064 abolished this effect. The same pattern was replicated in presence of protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (Fig. 3F), indicating that GW4064 can reverse the degradation of ERRα by XCT790. Further, GW4064 treatment reduced ERR interaction with immobilized SHP in an in-cell glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assay (Fig. 3G), whereas it enhanced ERRα interaction with coactivator transcriptional intermediary factor 2 (Fig. 3H), indicating that GW4064 may activate ERRα by reducing its interaction with SHP and enhancing its interaction with coactivators.

Together, these data demonstrate that PGC-1α expression is regulated by GW4064 through ERRα and that this regulation may occur due to a direct interaction between GW4064 and ERRα and concomitant increase in ERRα protein stability and reduction in interaction with corepressor SHP and enhancement of coactivator interaction.

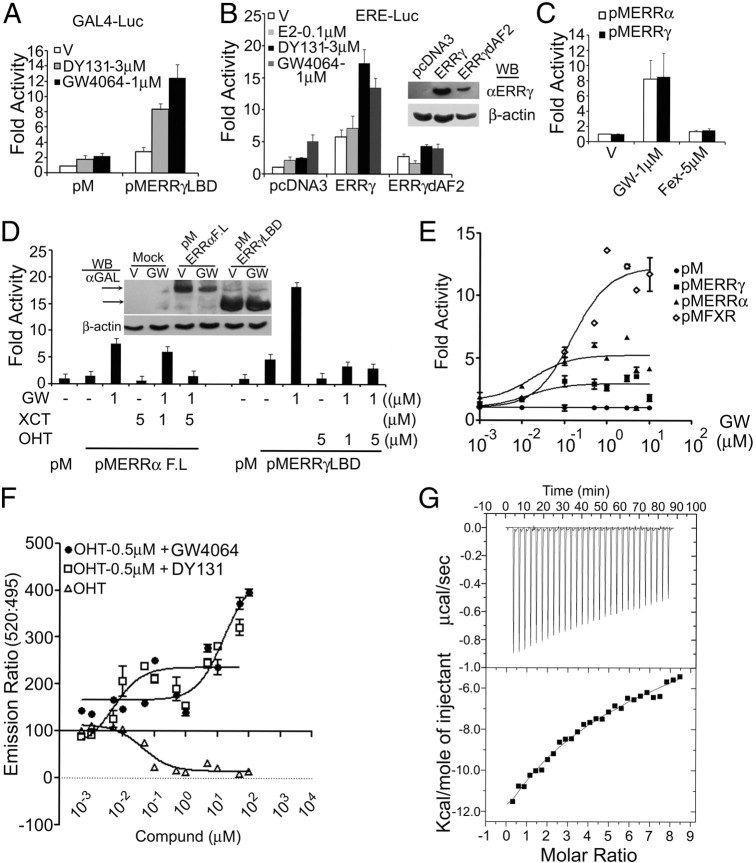

GW4064 is an ERR ligand

We next investigated whether GW4064 activates ERR group of proteins. To answer this, we used mammalian two hybrid-based ERR-cofactor interaction studies with or without GW4064 or DY131, an ERRβ/γ agonist (34). All three ERR isoforms, being constitutive transcriptional activators, interacted with steroid receptor coactivator 2 in absence of added agonist, and GW4064 further augmented these interactions (Supplemental Fig. 6). Further, GW4064 strongly activated pMERRα and showed comparable augmentation of pMERRγ activity with DY131 (Fig. 4, A, C, and D), whereas another FXR agonist Fexaramine (Fex) failed to do so (Fig. 4C). GW4064 also activated ERR-responsive ERE-luc (estrogen response element driven luciferase reporter) in ER and FXR-null Cos-7 cells, and this activity was enhanced by full-length ERRγ but not ERRγdAF2 (ERRγ deletion mutant lacking the activation function 2) (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, GW4064 activation of pMERRα or −ERRγ was compromised by their respective inverse agonists, XCT790 and OHT (Fig. 4D). GW4064 dose dependently enhanced pMFXR, pMERRα, or pMERRγ activity on Gal-luc, and the EC50 were determined to be 17.46 nm for ERRα, 13.32 nm for ERRγ, and 152.7 nm for FXR.

Fig. 4.

GW4064 is an ERR ligand. A, GW4064 augments pMERRγ activity on Gal-luc. Cos-7 cells were transfected and treated as indicated, and data were plotted as fold activity over vehicle (V)-treated controls. B, GW4064 enhances ERRγ activity on ERE-luc. C, GW4064 but not Fex activates ERRα and ERRγ on Gal-luc. D, XCT790 and OHT suppress GW4064-induced ERRα and ERRγ activation of GAL-luc, respectively. For pMERRα studies, 50 ng of PGC-1α were added, because ERRα is a weak activator of transcription in reporter assays. A–D, Data represent mean ± sd from three independent experiments. Insets are Western blottings showing expression levels of the transfected constructs. E, Dose response of GW4064 on ERRα and ERRγ. Cos-7 cells were transfected with Gal-luc and indicated expression plasmids and treated with indicated doses of GW4064. Normalized luciferase values were further normalized by dividing the values with corresponding values obtained from pM transfected cells. Data represent mean ± sd from one of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. All the experiments exhibited identical pattern. F, GW4064 relieves inhibition of ERRγ-coactivator interaction by OHT. TR-FRET assay was performed using “Lanthascreen” ERRγ coactivator assay kit. Y-axis represents ratio of fluorescence intensity at 520 nm (signal) and 495 nm (background). X-axis represents ligand doses in μM. Data represent mean ± sd of one experiment performed in quadruplets. One of two independent experiments is shown. G, Probing GW4064-ERRγLBD interactions by ITC. ITC was performed as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods. The negative peaks indicate an exothermic reaction. The area under each peak represents the heat released after an injection of GW4064 into ERRγLBD solution. Lower panel represents binding isotherms obtained by plotting peak areas against the molar ratio of ligand to ERRγLBD. The lines represent the best-fit curves obtained from least-squares regression analyses assuming a two set of sequential binding model. The raw data with integrated baseline are represented in upper panel. In the lower panel, the integrated peaks are represented by a fitted curve, using the “two set of sequential sites model” from Origin 7 (MicroCal). GW, GW4064; WB, Western blot.

To explore whether GW4064 is a ligand for ERR isoforms, a comparative docking study was performed. Because GW4064 could activate all ERR (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 5), and ERRγ is structurally the more well-studied isoform, it was chosen for structural analysis. The docking analyses were performed for known ERRγ ligands, including, OHT, Bisphenol A, DY131, GSK4716, and GW4064. It was observed that all the compounds occupy the same spatial position with similar binding mode as the cocrystallized OHT and Bisphenol A in ERRγ active site. A thorough examination of top scoring binding mode of GW4064 revealed that docking conformation of GW4064 is involved in aromatic interaction with aromatic ring of Trp305, Tyr326, and Phe435, whereas nonbonded Van der Waal interactions are mainly provided by Cys269, Ala272, Met306, Leu309, Ile310, Val313, and Leu440. Hydrogen bonds exist between carbonyl oxygen of Glu275 and carbonyl oxygen of GW4064 and NH2 of Arg316 and carbonyl oxygen of GW4064 to stabilize the complex whereas polar groups of Glu441 lie in close vicinity of Cl31 of GW4064 (Supplemental Fig. 7).

To confirm the physical interaction between ERR and GW4064, an in vitro time-resolved fluorescent resonant energy transfer (TR-FRET) assay was performed with ERRγ and a coactivator peptide. Because ERRγ shows strong constitutive coactivator interaction, the assay was modified as a competitor assay using OHT. As shown in Fig. 4E, OHT alone concentration-dependently inhibited the constitutive ERR-coactivator peptide interaction, and both DY131 and GW4064 concentration-dependently rescued the inhibition caused by 500 nm OHT.

To determine the thermodynamic property of ERRγ-GW4064 interaction, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was performed. As shown in Fig. 4F, a downward position of the ITC titration peaks (Fig. 4F, top panel) and the resultant negative integrated heats (Fig. 4F, bottom panel) demonstrated that the association between ERRγ ligand binding domain (LBD) and GW4064 is an enthalpically driven process at these experimental conditions, characterized by the equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) for the first and second binding site equal to 8.13 ± 1.0 μm (Kd1) and 292.4 ± 29.92 μm (Kd2), respectively.

Together, Figs. 3 and 4 demonstrate that GW4064 may indeed be a pan-ERR ligand and that the observed GW4064 effects on PGC-1α expression may be through ERRα activation.

FXR interacts with ERR and protects it from SHP repression

Although Figs. 3 and 4 clearly demonstrated the role of ERRα in GW4064-mediated PGC-1α induction, decreased basal PGC-1α transcript and absence of GW4064 effect in FXRKO liver (Fig. 2A) was still puzzling. We hypothesized that FXR may regulate ERR activity in liver.

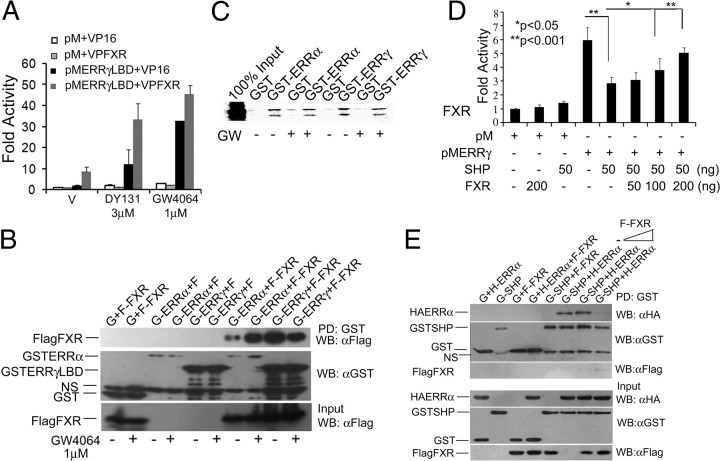

First, we investigated whether ERR interact with FXR. pMERRγ strongly interacted with VP16FXR in a mammalian two hybrid assay in absence of ligand, and the reporter activity was further enhanced in presence of both DY131 and GW4064 (Fig. 5A). In-cell GST pull-down assay also showed strong interaction between ERRα,γ and FXR in absence of GW4064 (Fig. 5B) and unlike in mammalian two hybrid assay, in this system, GW4064 failed to potentiate it (Fig. 5B). These data indicate that the augmentation of reporter activity in mammalian two hybrid interaction assay may reflect the increased transcriptional activity of the ERR-FXR complex but not the intensity of interaction between these two proteins. Further, in vitro GST pull-down assays showed that FXR physically interacts with ERRα and ERRγ with equal intensity in presence or absence of ligand (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

FXR interacts with ERR and protects them from SHP repression. A, ERRγ and FXR interact in Cos-7 mammalian two hybrid assay. Data represent mean ± sd from three independent experiments. B, ERRα and ERRγ interact with FXR in in-cell GST pull-down assay. In-cell GST pull down was performed as described elsewhere (20). One of two independent experiments is shown. C, Ligand-independent interaction of ERRα, ERRγ, and FXR in vitro. In vitro GST pull down was performed as described elsewhere (25). Representative figures out of six independent experiments are shown. D, FXR relieves SHP repression of ERR activity on Gal-luc. Data represent mean ± sd from three independent experiments. E, FXR blocks ERR-SHP interaction in in-cell GST pull-down assay. NS, Nonspecific; G, pEBG; G-SHP, pEBGSHP; G-ERRα, pEBGERRα; G-ERRγ, pEBGERRγ; H-ERRα, HAERRα; F-FXR, FlagFXR. V, Vehicle; PD, pull-down; GW, GW4064; WB, Western blot.

Because hepatic cells express SHP, which inhibits ERR activity (24, 25), we investigated whether FXR by interacting with ERR could modulate ERR repression by SHP. SHP strongly inhibited the constitutive activity of pMERRγ on Gal-luc (Supplemental Fig. 8), and this SHP repression was relieved by FXR in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5D). Consistent with previous reports (11), SHP failed to affect pMFXR activity (Supplemental Fig. 8). FXR also affected interaction between immobilized SHP and ERRα in in-cell pull-down assay, whereas no interaction between FXR and SHP was observed (Fig. 5E). Together these data demonstrate that FXR may protect ERR activity by competing with SHP.

Discussion

Our study has identified that GW4064, a synthetic FXR agonist, is also a bona fide agonist for ERR isoforms, and through ERRα, it augments PGC-1α expression in multiple tissues and cell lines. Although FXR does not regulate PGC-1α directly, it is necessary in ERRα-mediated PGC-1α expression in SHP-positive hepatic cells through a unique mechanism, whereby FXR interacts with ERR and protects them from SHP repression. Our results also demonstrate that, despite its absence in skeletal muscle, FXR inhibits PGC-1α expression through yet unknown mechanisms.

These results are important, because they provide mechanistic insights into a number of observations made earlier. For example, GW4064 but not CDCA has been reported to induce PGC-1α mRNA in HepG2 cells, although the mechanism was not elucidated (10). Further, structurally distinct FXR ligands CDCA, GW4064, and Fex have been found to induce distinct gene expression profiles in microarray (35, 36), and our study indicates that this difference between GW4064 and Fex may at least partly be due to GW4064 activation of ERR isoforms. Our data that GW4064 is an ERR agonist also gain an indirect support from an earlier report, where microarray analysis of GW4064 or CDCA treated primary rat hepatocytes revealed that 21 genes were up-regulated by 2-fold or more in GW4064 but not in CDCA-treated samples (36). Upon literature searches, we found that eight of these 21 genes have been reported as ERRα or ER targets by various methods, including pharmacological approaches, gene expression, and chromatin immunoprecipitation-based assays. These genes include carnitine palmitoyl transferase II (31), fatty acid transporter/CD36 (37), muscle LIM protein (37, 38), δ4-3-ketosteroid 5β-reductase (39), multidrug resistance protein 2 (40), heat shock protein 70 (41), UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B 15 (42), and SHP (25). We are currently pursuing detailed evaluation of these targets in reference to ERR-GW4064 in relevant tissues.

A puzzling observation, as witnessed here (Fig. 3B) and earlier, has been that SHP expression is remarkably reduced in FXRKO mice (8, 22, 43), despite the regulation of SHP promoter by liver-abundant and robust constitutive transcriptional activator, liver receptor homolog-1 (11, 14), and ERR (25). Our findings that FXR protects ERR from SHP repression gives a rational explanation to this phenomenon, where disruption of FXR may increase ERR-SHP interaction and subsequently cause stronger down-regulation of SHP promoter. A counter argument may be that in FXRKO liver, CYP7A1 is increased and GW4064 fails to repress it, but it is important to note that CYP7A1 repression by GW4064-FXR is routed through both SHP-dependent and SHP-independent pathways (44, 45). Further, using liver- or intestine-specific FXRKO mice, Kim et al. (46) demonstrated that in liver-specific FXRKO mice, GW4064 repression of hepatic CYP7A1 is not affected, whereas intestine-specific FXRKO eliminates GW4064 suppression of hepatic CYP7A1, indicating that most of the acute effect of FXR on CYP7A1 transcription is mediated by induction of fibroblast growth factor 15 in intestine.

Interestingly, a recent report has shown ER-FXR interaction in breast cancer cells (47), and we believe it will be worth investigating whether all SHP interacting NR could interact with FXR. Moreover, recent genome-wide FXR binding sites in liver and intestine revealed the presence of half-sites (AGGTCA or TGACCT) adjacent to FXR binding sequences (48). Further, another recent report showed that FXR by binding to steroidogenic factor 1 response element regulates aromatase expression in Leydig cells (49). Incidentally, these half-sites and steroidogenic factor 1 response element sequences represent typical ERR binding sites.

Together, FXR-ERR interaction, ligand sharing, and a possibility of sharing of target elements suggest that ERR and FXR pathways may converge in a multitude of physiological and disease pathways. Detailed dissection, which is currently in progress, of this intricate interplay under different experimental conditions may help in developing new treatment regimens to various metabolic disease states.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

GW4064 was procured from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and Tocris Biosciences (Ellisville, MO) and compared. Both showed identical activities on PGC-1α expression, PGC-1luc activation, and ERR/FXR transactivation. Sigma GW4064 was used for all the experiments in this report. CDCA, XCT790, and OHT were from Sigma. JC-1, LanthaScreen ERRγ TR-FRET Coactivator assay kit, cell culture media, and supplements were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Remaining chemicals were from Sigma unless otherwise indicated.

Primers

Trans-species primers for RT-PCR

Trans-species primers were designed from conserved regions of indicated genes based on trans-species sequence alignment [using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (bl2seq) program from National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD)] between Homo sapiens, Rattus norvegicus, Mus musculus, Macaca mulata, and Pan troglodytes. In all the cases, the deduced product lengths were identical as checked by species specific primer blast searches from National Center for Biotechnology Information. The primer sequences (5′-3′) are: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) forward (F), CACCATCTTCCAGGAGCGAGA; GAPDH reverse (R), GCTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTG CA; FXR F, AAAGGGGATGAGCTGTGTGT; FXR R, TTCAGCCAACATTCCCATCTC; PGC-1α F, GCTGAACAAGCACTTCGGTCA; PGC-1α R, GCATCCTTTGGGGTCTTTGAGA; ERRα F, CCTGACAGTCCAAAGGGTTC; ERRα R, ATGGTCCTCTTGAAGAAGGC; ERRγ F, AGTTCAACCATGAATGGCCATCA; ERRγ R, GCCTTGCAGGCTTCACATGA.

Mouse primers for QRT-PCR

GAPDH F, GTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA; GAPDH R,CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTG; PGC-1α F, AGCCGTGACCACTGACAACGAG; PGC-1α R, CTGCATGGTTCTGAGTGCTAAG; FXR F, TCCGGACATTCAACCATCAC; FXR R, TCACTGCATCCCAGATCTC; SHP F, CTGAAGGGCACGATCCTCTTC; SHP R, ACCAGGGCTCCAAGACTTCAC; CYP7A1 F, AGCAACTAAACAACCTGCCAGT ACTA; CYP7A1 R, GTCCGGATATTCAAGGATGCA; mt-TFA F, CTGATGGGTATGGA GAAGGAGG; mt-TFA R, CCAACTTCAGCCATCTGCTCTTC; NRF-1 F, GAACGCC AC CGATTTCACTGTC; NRF-1 R, CCCTACCACCCACGAATCTGG; NRF-2 F, GGCACAG TGCTCCTATGCGTG; NRF-2 R, CCAGCTCGACAATGTTCTCCAGC; COX-II F, CCA TAGGGCACCAATGATACTG; COX-II R, AGTCGGCCTGGGATGGCATC; cytochrome C somatic F, TTGACCAGCCCGGAACGAAT; and Cytochrome C somatic R, GCTATTAGGTCTGCCCTTTCTCCC.

Human primers for QRT-PCR

GAPDH F, GCAGGGGGGAGCCAAAAGGGT; GAPDH R, TGGGTGGCAGTGATGGCATGG; PGC-1α F, TGAGAGGGCCAAGCAAAG; PGC-1α R, ATAAATCACACGGCGCTCTT; SHP F, AGGGACCATCCTCTTCAACC; and SHP R, TTCACAGCACCCAGTGAG.

Rat primers for QRT-PCR

GAPDH F, TGGGAAGCTGGTCATCAAC; GAPDH R, GCATCACCCATTTGATGTT; PGC-1α F, AGACGTGACCACTGACAACGAG; and PGC-1α R, TTGCATGGTTCTGAGTGCTAAG.

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used in this study were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA) (hemagglutinin, HA), Abcam (Cambridge, MA) (ERRγ), Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., (Santa Cruz, CA) (Gal4, GST, and β-actin), Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO) (ERRα), and Sigma (Flag). Anti-PGC-1α mouse monoclonal antibody (4C1.3) was from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) (this antibody was selected because it detects a single band of ∼110 kDa and it does not detect any band in PGC-1α knockout tissues).

Plasmids

Human (−992 to +90) and mouse (−2533 to + 78) PGC-1α promoters were cloned in pGL3-Basic (Promega, Madison, WI) as described elsewhere (50, 51). pCMV3XHAERRα and pCMV3XHAERRγ were subcloned from pcDNA3 ERRα/γ into pCMV3XHA (20). Mammalian GST expression constructs were constructed by cloning respective fragments from PCMV3XHAERRα and pGEX4TERRγLBD (25) into pEBG (a gift from Bruce Mayer; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) (20). pMFXR was constructed by subcloning full-length human FXR into pM vector (CLONTECH, Mountain View, CA). 3XFlagFXR was a kind gift from Rayuchiro Sato (Biological Science Laboratories; Kao Corp., Tokyo, Japan). All the constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Remaining plasmids used are reported elsewhere (18, 20, 25).

Cell culture and transient transfection-based reporter assays

All cell lines used were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained as par American Type Culture Collection recommendations. Primary rat calvarial osteoblast cells were cultured as described elsewhere (52). Transfections were carried out with lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). Total DNA in each transfection was adjusted to 700 ng by adding pcDNA3 empty vector. Luciferase activity was measured in a GloMax-96 microplate luminometer (Promega) using Steady-Glo Assay (Promega), GFP fluorescence was quantified in a fluorimeter (POLARstar Galaxy; BMG Labtech, Cary, NC).

RNAi, RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and QRT-PCR

Human ERRα siRNA and control siRNA (siPGL3) were from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). HepG2 cells were transfected with 100 nm of siRNA using Dharmafect I transfection reagent (Dharmacon). RNA isolation, RT-PCR were performed as reported earlier (20). QRT-PCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 System (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and analyzed by ΔΔCT method with GAPDH used as an internal control. To ensure the homogeneity of the PCR products, melting curves were acquired after each reaction.

Protein extraction, protein-protein interaction assays, and Western blotting

These assays were performed as described elsewhere (20).

TR-FRET assay

TR-FRET assays were performed in 384-well low-volume assay plate, using lanthascreen TR-FRET assay kit (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 20 μl, as per manufacturer's instructions, with minor modifications. Briefly, the GST-tagged ERRγLBD, terbium-labeled anti-GST antibody, and fluorescein-labeled peptide PGC-1α were added to indicated ligands in a white 384-well assay plate for final assay concentrations of 5 nm LBD, 5 nm antibody, and 0.5 μm peptide. Ligand volume was kept constant for all wells. After 1-h incubation at 25 C, the terbium emission at 495 nm and the FRET signal at 520 nm were measured after excitation at 340 nm using a BMG FLUOstar Galaxy 384 microplate reader. Data were plotted as ratio of emissions at 495 and 520 nm.

Protein purification and isothermal calorimetry

ERRγLBD (amino acids 222–458) was amplified by PCR using primers mouse ERRγ F (5′-CCGGGATCCCTGAACCCTCAGCTGGTGCAGCCAG-3′) and mouse ERRγ R (5′-GCCCTCGAGTCAGACCTTGGCCTCCAGCATTTCCA-3′) and was cloned into pGEX4T-1 at BamH1 and XhoI sites. For protein expression and purification, pGEX4T-1 ERRγLBD was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified on an affinity column of glutathione-sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Co., Princeton, NJ). GST was cleaved on the resin by thrombin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), for 12 h at 4 C. After incubation, ERRγLBD was eluted in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 50 mm NaCl, and its concentration was determined by the Bradford method.

ITC experiments were performed on a MicroCal VP-ITC MicroCalorimeter (MicroCal, Northampton, MA) calibrated as per users protocol. Reference cell was filled with water. All ITC experiments were conducted in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), containing 150 mm NaCl. To prepare the ligand solution, 20 μl of a 10 mm compound stock in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was added to 1 ml of buffer. A matched quantity of DMSO was added to the protein sample, and the sample was vortexed and centrifuged immediately before running the experiment. All solutions were degassed for 10–15 min at 20 C before loading the samples in the ITC cell and syringe. All titrations were carried out at 25 C with a stirring speed of 351 rpm and 180 sec spacing between each 10-μl injection of 20-sec duration. The titrand solution contained 0.2 mm of the compound DY131 or GW4064, and the reaction cell contained 1.4359 ml of 5 μm ERRγLBD. To correct for the heats of dilution, control experiments were performed by making identical injections of the titrand solution into a cell containing only buffer with equal percentage of DMSO. These control experiment values were subtracted from their respective titration before data analysis. The fitting of ITC data to different binding models by nonlinear least-squares approach (Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm) was done with MicroCal Origin software package version 7.0 (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA) provided with the instrument. Thermal titration data were fitted to one or more of the three association models available in the software: single set of identical sites, two sets of independent sites, and sequential binding sites (53). The basic principal of these mathematical approaches are summarized elsewhere (54). The models were compared by visual inspection of the fitted curves and by comparing the χ2 values obtained after the computation. The model resulting in the lowest value of χ2 was considered the best model to describe the molecular mechanism of binding. A sequential two-site binding model, in which the Kd is a function of the number of binding sites occupied, provided a better fit to the data. This analysis yielded thermodynamic parameters association constant (Ka) (Ka K1 and K2) and enthalpy of binding (ΔH1, ΔH2). The free energy of binding (ΔG) and entropy change (ΔS) were obtained using the fundamental equations of thermodynamics.

| (1) |

Where, r = 1.9872 cal · mol−1 · K−1, T = 298 K.

And

| (2) |

The affinity of the ligand to protein is given as the Kd.

| (3) |

Duplicate titrations were performed for each sample set to evaluate reproducibility.

Animal studies

All animal experimentation described in the submitted manuscript was conducted in accord with accepted standards of humane animal care, as according to the Institutional Animal Ethical Guidelines. Mice were maintained under a standard 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle with water and chow provided ad libitum. Eight-wk-old male BALB/C (1-d-treatment group) or 10- to 12-wk-old male FXRKO and age- and sex-matched WT (3-d-treatment group) were given GW4064 (50 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle (gum acacia), by oral gavage. The animals were killed in fed condition, tissues were isolated and used for RNA extraction.

Statistics

Data are represented as mean ± sd from three independent experiments, unless otherwise indicated. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t test.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rayuchiro Sato and Dr. Bruce Mayer for kind gift of plasmids and Dr. Eckardt Treuter for critical reading of the manuscript.

Present address for So.S.: Department of Biotechnology, Amity University, Viraj Khand 5, Gomti Nagar, Lucknow 226010, India.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid project of Ministry of Health, Government of India; Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) Network Projects NWP0032 and NWP0034; CSIR Grant SIP0007 (to A.B.); CSIR fellowship grants (S.K.D.D. and R.K.); the University Grants Commission (N.S. and J.S.M.); and CDRI communication number 8047.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Nuclear Receptors: ERR-α | FXR-α | SHP;

Coregulators: PGC-1;

Ligands: GW4064 | 4-Hydroxytamoxifen | Bisphenol A.

Footnotes

- CDCA

- Chenodeoxycholic acid

- COX-II

- cytochrome C oxidase II

- CT

- cycle threshold

- CYP7A1

- cholesterol-7α-hydroxylase

- DMSO

- dimethylsulfoxide

- ERR

- estrogen receptor-related receptor

- F

- forward

- Fex

- Fexaramine

- FXR

- farnesoid X receptor

- FXRKO

- FXR knockout

- Gal-Luc

- luciferase reporter driven by yeast GAL 4 response element

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- Ka

- association constant

- Kd

- dissociation constant

- LBD

- ligand binding domain

- mt-TFA

- mitochondrial transcription factor

- NRF

- nuclear respiratory factor

- OHT

- 4-hydroxytamoxifen

- PGC-1α

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α

- QRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- R

- reverse

- SHP

- small heterodimer partner

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TR-FRET

- time-resolved fluorescent resonant energy transfer

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Lin J , Wu H , Tarr PT , Zhang CY , Wu Z , Boss O , Michael LF , Puigserver P , Isotani E , Olson EN , Lowell BB , Bassel-Duby R , Spiegelman BM. 2002. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1α drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature 418:797–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Puigserver P , Wu Z , Park CW , Graves R , Wright M , Spiegelman BM. 1998. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92:829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knutti D , Kaul A , Kralli A. 2000. A tissue-specific coactivator of steroid receptors, identified in a functional genetic screen. Mol Cell Biol 20:2411–2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Puigserver P , Spiegelman BM. 2003. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocr Rev 24:78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finck BN , Kelly DP. 2006. PGC-1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J Clin Invest 116:615–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Handschin C , Spiegelman BM. 2006. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 coactivators, energy homeostasis, and metabolism. Endocr Rev 27:728–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lefebvre P , Cariou B , Lien F , Kuipers F , Staels B. 2009. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev 89:147–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang Y , Lee FY , Barrera G , Lee H , Vales C , Gonzalez FJ , Willson TM , Edwards PA. 2006. Activation of the nuclear receptor FXR improves hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:1006–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stayrook KR , Bramlett KS , Savkur RS , Ficorilli J , Cook T , Christe ME , Michael LF , Burris TP. 2005. Regulation of carbohydrate metabolism by the farnesoid X receptor. Endocrinology 146:984–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Fabiani E , Mitro N , Gilardi F , Caruso D , Galli G , Crestani M. 2003. Coordinated control of cholesterol catabolism to bile acids and of gluconeogenesis via a novel mechanism of transcription regulation linked to the fasted-to-fed cycle. J Biol Chem 278:39124–39132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goodwin B , Jones SA , Price RR , Watson MA , McKee DD , Moore LB , Galardi C , Wilson JG , Lewis MC , Roth ME , Maloney PR , Willson TM , Kliewer SA. 2000. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Mol Cell 6:517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maloney PR , Parks DJ , Haffner CD , Fivush AM , Chandra G , Plunket KD , Creech KL , Moore LB , Wilson JG , Lewis MC , Jones SA , Willson TM. 2000. Identification of a chemical tool for the orphan nuclear receptor FXR. J Med Chem 43:2971–2974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moschetta A , Bookout AL , Mangelsdorf DJ. 2004. Prevention of cholesterol gallstone disease by FXR agonists in a mouse model. Nat Med 10:1352–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu TT , Makishima M , Repa JJ , Schoonjans K , Kerr TA , Auwerx J , Mangelsdorf DJ. 2000. Molecular basis for feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis by nuclear receptors. Mol Cell 6:507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Båvner A , Sanyal S , Gustafsson JA , Treuter E. 2005. Transcriptional corepression by SHP: molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16:478–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giguère V. 2008. Transcriptional control of energy homeostasis by the estrogen-related receptors. Endocr Rev 29:677–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rangwala SM , Wang X , Calvo JA , Lindsley L , Zhang Y , Deyneko G , Beaulieu V , Gao J , Turner G , Markovits J. 2010. Estrogen-related receptor γ is a key regulator of muscle mitochondrial activity and oxidative capacity. J Biol Chem 285:22619–22629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanyal S , Matthews J , Bouton D , Kim HJ , Choi HS , Treuter E , Gustafsson JA. 2004. Deoxyribonucleic acid response element-dependent regulation of transcription by orphan nuclear receptor estrogen receptor-related receptor γ. Mol Endocrinol 18:312–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bookout AL , Jeong Y , Downes M , Yu RT , Evans RM , Mangelsdorf DJ. 2006. Anatomical profiling of nuclear receptor expression reveals a hierarchical transcriptional network. Cell 126:789–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sanyal S , Båvner A , Haroniti A , Nilsson LM , Lundåsen T , Rehnmark S , Witt MR , Einarsson C , Talianidis I , Gustafsson JA , Treuter E. 2007. Involvement of corepressor complex subunit GPS2 in transcriptional pathways governing human bile acid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:15665–15670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duran-Sandoval D , Cariou B , Percevault F , Hennuyer N , Grefhorst A , van Dijk TH , Gonzalez FJ , Fruchart JC , Kuipers F , Staels B. 2005. The farnesoid X receptor modulates hepatic carbohydrate metabolism during the fasting-refeeding transition. J Biol Chem 280:29971–29979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma K , Saha PK , Chan L , Moore DD. 2006. Farnesoid X receptor is essential for normal glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest 116:1102–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cariou B , van Harmelen K , Duran-Sandoval D , van Dijk TH , Grefhorst A , Abdelkarim M , Caron S , Torpier G , Fruchart JC , Gonzalez FJ , Kuipers F , Staels B. 2006. The farnesoid X receptor modulates adiposity and peripheral insulin sensitivity in mice. J Biol Chem 281:11039–11049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang L , Liu J , Saha P , Huang J , Chan L , Spiegelman B , Moore DD. 2005. The orphan nuclear receptor SHP regulates PGC-1α expression and energy production in brown adipocytes. Cell Metab 2:227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sanyal S , Kim JY , Kim HJ , Takeda J , Lee YK , Moore DD , Choi HS. 2002. Differential regulation of the orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner (SHP) gene promoter by orphan nuclear receptor ERR isoforms. J Biol Chem 277:1739–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schreiber SN , Knutti D , Brogli K , Uhlmann T , Kralli A. 2003. The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1 regulates the expression and activity of the orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα). J Biol Chem 278:9013–9018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lanvin O , Bianco S , Kersual N , Chalbos D , Vanacker JM. 2007. Potentiation of ICI182,780 (fulvestrant)-induced estrogen receptor-α degradation by the estrogen receptor-related receptor-α inverse agonist XCT790. J Biol Chem 282:28328–28334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coward P , Lee D , Hull MV , Lehmann JM. 2001. 4-Hydroxytamoxifen binds to and deactivates the estrogen-related receptor γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:8880–8884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Urizar NL , Liverman AB , Dodds DT , Silva FV , Ordentlich P , Yan Y , Gonzalez FJ , Heyman RA , Mangelsdorf DJ , Moore DD. 2002. A natural product that lowers cholesterol as an antagonist ligand for FXR. Science 296:1703–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burris TP , Montrose C , Houck KA , Osborne HE , Bocchinfuso WP , Yaden BC , Cheng CC , Zink RW , Barr RJ , Hepler CD , Krishnan V , Bullock HA , Burris LL , Galvin RJ , Bramlett K , Stayrook KR. 2005. The hypolipidemic natural product guggulsterone is a promiscuous steroid receptor ligand. Mol Pharmacol 67:948–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dufour CR , Wilson BJ , Huss JM , Kelly DP , Alaynick WA , Downes M , Evans RM , Blanchette M , Giguère V. 2007. Genome-wide orchestration of cardiac functions by the orphan nuclear receptors ERRα and γ. Cell Metab 5:345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schreiber SN , Emter R , Hock MB , Knutti D , Cardenas J , Podvinec M , Oakeley EJ , Kralli A. 2004. The estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα) functions in PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α)-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:6472–6477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu Z , Puigserver P , Andersson U , Zhang C , Adelmant G , Mootha V , Troy A , Cinti S , Lowell B , Scarpulla RC , Spiegelman BM. 1999. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu DD , Forman BM. 2005. Identification of an agonist ligand for estrogen-related receptors ERRβ/γ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 15:1311–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Downes M , Verdecia MA , Roecker AJ , Hughes R , Hogenesch JB , Kast-Woelbern HR , Bowman ME , Ferrer JL , Anisfeld AM , Edwards PA , Rosenfeld JM , Alvarez JG , Noel JP , Nicolaou KC , Evans RM. 2003. A chemical, genetic, and structural analysis of the nuclear bile acid receptor FXR. Mol Cell 11:1079–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pircher PC , Kitto JL , Petrowski ML , Tangirala RK , Bischoff ED , Schulman IG , Westin SK. 2003. Farnesoid X receptor regulates bile acid-amino acid conjugation. J Biol Chem 278:27703–27711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huss JM , Torra IP , Staels B , Giguère V , Kelly DP. 2004. Estrogen-related receptor α directs peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α signaling in the transcriptional control of energy metabolism in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biol 24:9079–9091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Lange P , Moreno M , Silvestri E , Lombardi A , Goglia F , Lanni A. 2007. Fuel economy in food-deprived skeletal muscle: signaling pathways and regulatory mechanisms. FASEB J 21:3431–3441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takahashi Y , Odbayar TO , Ide T. 2009. A comparative analysis of genistein and daidzein in affecting lipid metabolism in rat liver. J Clin Biochem Nutr 44:223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vollrath V , Wielandt AM , Iruretagoyena M , Chianale J. 2006. Role of Nrf2 in the regulation of the Mrp2 (ABCC2) gene. Biochem J 395:599–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shimizu T , Yu HP , Suzuki T , Szalay L , Hsieh YC , Choudhry MA , Bland KI , Chaudry IH. 2007. The role of estrogen receptor subtypes in ameliorating hepatic injury following trauma-hemorrhage. J Hepatol 46:1047–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harrington WR , Sengupta S , Katzenellenbogen BS. 2006. Estrogen regulation of the glucuronidation enzyme UGT2B15 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 147:3843–3850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cariou B , van Harmelen K , Duran-Sandoval D , van Dijk T , Grefhorst A , Bouchaert E , Fruchart JC , Gonzalez FJ , Kuipers F , Staels B. 2005. Transient impairment of the adaptive response to fasting in FXR-deficient mice. FEBS Lett 579:4076–4080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Holt JA , Luo G , Billin AN , Bisi J , McNeill YY , Kozarsky KF , Donahee M , Wang DY , Mansfield TA , Kliewer SA , Goodwin B , Jones SA. 2003. Definition of a novel growth factor-dependent signal cascade for the suppression of bile acid biosynthesis. Genes Dev 17:1581–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Song KH , Li T , Owsley E , Strom S , Chiang JY. 2009. Bile acids activate fibroblast growth factor 19 signaling in human hepatocytes to inhibit cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene expression. Hepatology 49:297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim I , Ahn SH , Inagaki T , Choi M , Ito S , Guo GL , Kliewer SA , Gonzalez FJ. 2007. Differential regulation of bile acid homeostasis by the farnesoid X receptor in liver and intestine. J Lipid Res 48:2664–2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Journe F , Laurent G , Chaboteaux C , Nonclercq D , Durbecq V , Larsimont D , Body JJ. 2008. Farnesol, a mevalonate pathway intermediate, stimulates MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth through farnesoid-X-receptor-mediated estrogen receptor activation. Breast Cancer Res Treat 107:49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thomas AM , Hart SN , Kong B , Fang J , Zhong XB , Guo GL. 2010. Genome-wide tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor binding in mouse liver and intestine. Hepatology 51:1410–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Catalano S , Malivindi R , Giordano C , Gu G , Panza S , Bonofiglio D , Lanzino M , Sisci D , Panno ML , Andò S. 2010. Farnesoid X receptor, through the binding with steroidogenic factor 1-responsive element, inhibits aromatase expression in tumor Leydig cells. J Biol Chem 285:5581–5593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Handschin C , Rhee J , Lin J , Tarr PT , Spiegelman BM. 2003. An autoregulatory loop controls peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α expression in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:7111–7116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Daitoku H , Yamagata K , Matsuzaki H , Hatta M , Fukamizu A. 2003. Regulation of PGC-1 promoter activity by protein kinase B and the forkhead transcription factor FKHR. Diabetes 52:642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bhargavan B , Gautam AK , Singh D , Kumar A , Chaurasia S , Tyagi AM , Yadav DK , Mishra JS , Singh AB , Sanyal S , Goel A , Maurya R , Chattopadhyay N. 2009. Methoxylated isoflavones, cajanin and isoformononetin, have non-estrogenic bone forming effect via differential mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling. J Cell Biochem 108:388–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wiseman T , Williston S , Brandts JF , Lin LN. 1989. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal Biochem 179:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jelesarov I , Bosshard HR. 1999. Isothermal titration calorimetry and differential scanning calorimetry as complementary tools to investigate the energetics of biomolecular recognition. J Mol Recognit 12:3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]