Pasireotide activates the sst2A receptor via a molecular switch that is structurally and functionally distinct from that turned on during octreotide-driven sst2A activation.

Abstract

The clinically used somatostatin (SS-14) analogs octreotide and pasireotide (SOM230) stimulate distinct species-specific patterns of sst2A somatostatin receptor phosphorylation and internalization. Like SS-14, octreotide promotes the phosphorylation of at least six carboxyl-terminal serine and threonine residues, namely S341, S343, T353, T354, T356, and T359, which in turn leads to a robust endocytosis of both rat and human sst2A receptors. Unlike SS-14, pasireotide fails to induce any substantial phosphorylation or internalization of the rat sst2A receptor. Nevertheless, pasireotide is able to stimulate a selective phosphorylation of S341 and S343 of the human sst2A receptor followed by a clearly detectable receptor sequestration. Here, we show that transplantation of amino acids 1–180 of the human sst2A receptor to the rat sst2A receptor facilitates pasireotide-induced internalization. Conversely, construction of a rat-human sst2A chimera conferred resistance to pasireotide-induced internalization. We then created a series of site-directed mutants leading to the identification of amino acids 27, 30, 163, and 164 that when exchanged to their human counterparts facilitated pasireotide-driven S341/S343 phosphorylation and internalization of the rat sst2A receptor. Exchange of these amino acids to their rat counterparts completely blocked the pasireotide-mediated internalization of the human sst2A receptor. Notably, octreotide and SS-14 stimulated a full phosphorylation and internalization of all mutant sst2A receptors tested. Together, these findings suggest that pasireotide activates the sst2A receptor via a molecular switch that is structurally and functionally distinct from that turned on during octreotide-driven sst2A activation.

The peptide hormone somatostatin (SS-14) is widely distributed throughout the brain and periphery where it regulates the release of a variety of hormones including GH, TSH, ACTH, glucagon, insulin, gastrin, and ghrelin (1). The biological actions of SS-14 are mediated by five G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), named somatostatin receptor (sst)1 through sst5. Natural SS-14 binds with high affinity to all five SS-14 receptors. However, the clinical utility of SS-14 is limited by its rapid degradation in human plasma.

In the past, a number of metabolically stable SS-14 analogs have been synthesized, two of which, octreotide and lanreotide, were approved for clinical use. Octreotide and lanreotide bind with high subnanomolar affinity to sst2 only, have moderate affinity to sst3 and sst5, and show very low or absent binding to sst1 and sst4. In clinical practice, octreotide and lanreotide are used as first choice medical treatment of neuroendocrine tumors such as GH-secreting adenomas and carcinoids (2, 3). Loss of octreotide response in these tumors occurs due to diminished expression of sst2A, whereas expression of sst5 persists (4). Octreotide has no suppressive effect on ACTH levels in patients with Cushing's disease, a condition with predominant sst5 expression (4).

Recently, the novel multireceptor SS-14 analog, pasireotide (SOM230), has been synthesized (5). Pasireotide is a cyclohexapeptide that binds with high affinity to all SS-14 receptors except sst4 (6). In contrast to octreotide, pasireotide exhibits particular high subnanomolar affinity to sst5 and an improved metabolic stability (7). Pasireotide is currently under clinical evaluation as a successor compound to octreotide for treatment of acromegaly, Cushing's disease, and octreotide-resistant carcinoid tumors (8–10).

We have recently uncovered agonist-selective and species-specific patterns of sst2A receptor phosphorylation and trafficking (11). Whereas octreotide, in a manner similar to that observed with SS-14, stimulates the phosphorylation of a number of carboxyl-terminal phosphate acceptor sites in both rat and human sst2A receptors, pasireotide fails to promote any detectable phosphorylation or internalization of the rat sst2A receptor. In contrast, pasireotide is able to trigger a partial internalization of the human sst2A receptor. In the present study, we created a series of receptor chimeras and site-directed mutants, which led to the identification of structural determinants involved in the agonist-selective regulation of sst2A receptor signaling and trafficking.

Results

Structural determinants of agonist-selective internalization of the sst2A receptor

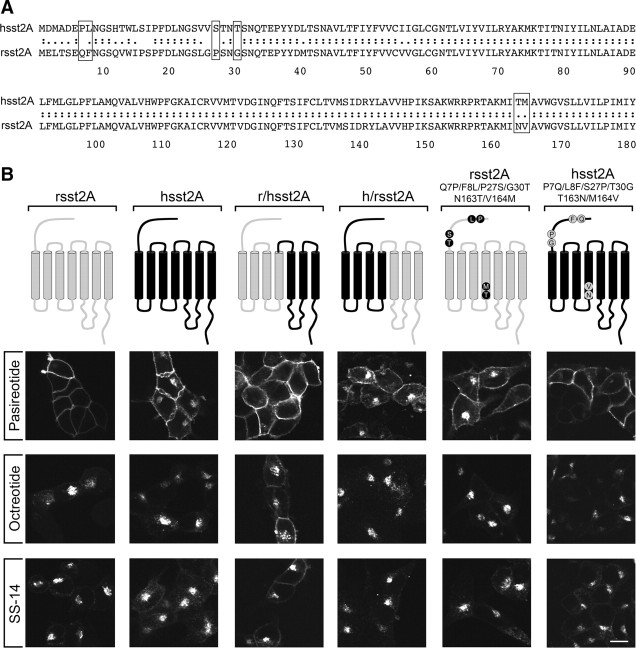

First, we examined agonist-induced internalization of the wild-type rat and human sst2A receptors by ELISA (Supplemental Fig. 1 published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web at http://mend.endojournals.org). We found that octreotide and SS-14 induced a similar dose-dependent internalization of both rat and human sst2A receptors. Pasireotide induced a partial internalization of the human sst2A receptor but completely failed to stimulate any detectable internalization of the rat sst2A receptor. Given that pasireotide has a lower affinity to the sst2A receptor than SS-14 or octreotide (Supplemental Table 1), we then examined the effects of 1 μm SS-14, 1 μm octreotide, and 10 μm pasireotide on the internalization of the rat and human sst2A receptors by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1 B (first panel), saturating concentrations of pasireotide failed to stimulate any detectable internalization of the rat sst2A receptor. In contrast, pasireotide was able to induce a clearly detectable internalization of the human sst2A receptor (Fig. 1B, second panel). Octreotide and SS-14 promoted a robust internalization of both rat and human sst2A receptors. Thus, pasireotide is unique in that it induced a species-selective internalization, whereas octreotide and SS-14 did not discriminate between rat and human sst2A receptors. We then used the species selectivity of the pasireotide-mediated internalization to further elucidate the structural determinants of agonist-selective signaling at the sst2A receptor. Two chimeras were constructed: first, amino acids 181–369 of the rat sst2A receptor were exchanged for their human counterparts. However, analysis of agonist-induced internalization of this rat-human sst2A chimera revealed that transplantation of the human carboxyl-terminal tail was not sufficient to drive pasireotide-induced internalization of the rat sst2A receptor (Fig. 1B, third panel). Second, exchange of amino acids 1–180 of the human sst2A receptor to the rat sst2A receptor facilitated pasireotide-induced internalization, suggesting that the structural basis for the species-selective sst2A internalization must reside within the amino-terminal half of the receptor (Fig. 1B, fourth panel). This region is highly homologous between rat and human sst2A receptors. Nevertheless, comparison of the amino acid sequences revealed several differences, six of which were selected for further analysis (Fig. 1A, boxed amino acids). When these six residues, i.e. amino acids 7, 8, 27, 30, 163, and 164, were exchanged for their human counterparts, pasireotide was able to stimulate a clearly detectable internalization of the rat sst2A receptor (Fig. 1B, fifth panel). Conversely, exchange of amino acids 7, 8, 27, 30, 163, and 164 for their rat counterparts conferred complete resistance to pasireotide-mediated internalization of the human sst2A receptor (Fig. 1B, sixth panel). Again, octreotide and SS-14 induced a robust internalization of all chimeras and mutants tested (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Agonist-selective internalization of rat and human sst2A receptors. A, Sequence comparison of amino acids 1–180 of rat and human sst2A. Boxed amino acids were selected for site-directed mutagenesis. B (upper panel), Schematic representation of chimeras and mutant receptors analyzed. Rat sst2A is depicted in gray. Human sst2A is depicted in black. B (lower panel), HEK293 cells stably expressing the indicated sst2A receptors were treated with either 10 μm pasireotide, 1 μm octreotide, or 1 μm SS-14 for 30 min. Cells were fixed, immunofluorescence stained with anti-sst2A antibody (UMB-1), and examined by confocal microscopy. Note that the structural basis for agonist-selective sst2A internalization resides in six residues within amino acids 1–180. Shown are representative images from one of at least five independent experiments performed in duplicate. Scale bar, 20 μm.

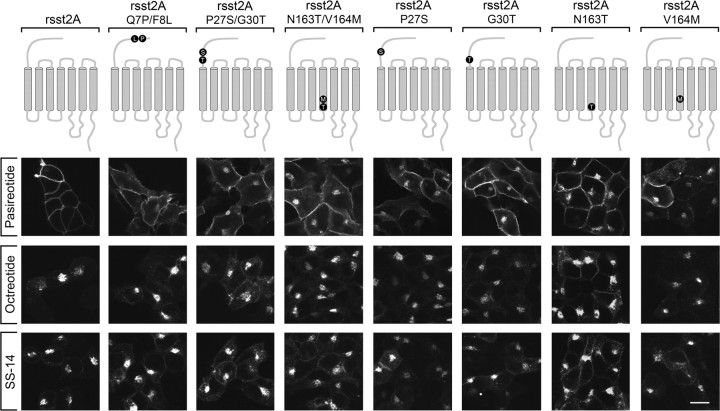

To further elucidate the structural determinants for species-selective sst2A internalization, we constructed a series of single and double mutants of the rat sst2A receptor. Analysis of three double mutants revealed that exchange of either amino acids 27 and 30 or 163 and 164, but not of amino acids 7 and 8, to their human counterparts was sufficient to facilitate pasireotide-induced internalization of the rat sst2A receptor (Fig. 2). Moreover, analysis of single mutants revealed that exchange of either amino acid 27, 30, 163, or 164 to their human counterparts was sufficient to facilitate pasireotide-induced internalization of the rat sst2A receptor (Fig. 2). Again, octreotide and SS-14 induced a robust internalization of all mutants tested (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Structural determinants of agonist-selective sst2A internalization. Upper panel, Schematic representation of mutant rat sst2A receptors. Lower panel, HEK293 cells stably expressing the indicated sst2A receptors were treated with either 10 μm pasireotide, 1 μm octreotide, or 1 μm SS-14 for 30 min. Cells were fixed, immunofluorescence stained with anti-sst2A antibody (UMB-1), and examined by confocal microscopy. Note that exchange of either amino acid 27, 30, 163, or 164 to their human counterparts was sufficient to facilitate pasireotide-induced internalization of the rat sst2A receptor. Shown are representative images from one of at least four independent experiments performed in duplicate. Scale bar, 20 μm.

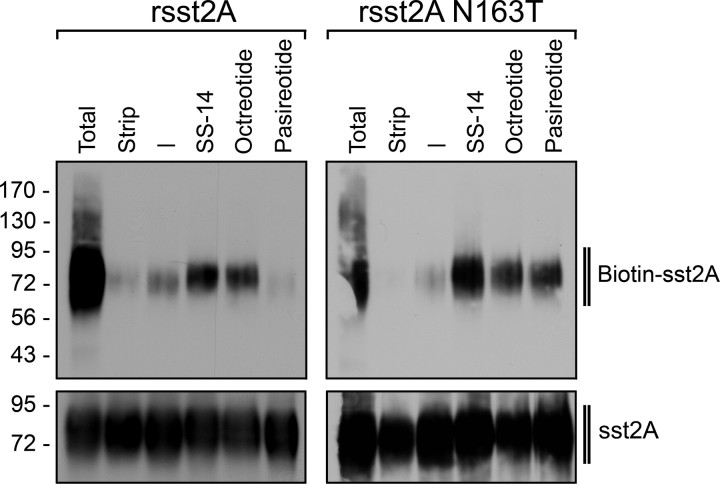

Next, sst2A internalization was quantitatively analyzed using surface biotinylation protection assays. Cells expressing either the wild-type or the N163T mutant of the rat sst2A receptor were subjected to surface biotinylation and then exposed to pasireotide, octreotide, or SS-14. Subsequently, remaining surface biotinylation was stripped, cells were lysed, and biotinylated proteins were precipitated using streptavidin-agarose, allowing selective detection of internalized receptors. The results depicted in Fig. 3 (left panel) confirm that pasireotide did not promote any detectable internalization of the rat sst2A receptor. In contrast, pasireotide stimulated a robust internalization of the N163T mutant (Fig. 3, right panel). Again, octreotide and SS-14 did not discriminate between the two receptors (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of sst2A receptor internalization. HEK293 cells stably expressing the wild type or the N163T mutant of the rat sst2A receptor were subjected to surface biotinylation and then exposed to either 10 μm pasireotide, 1 μm octreotide, or 1 μm SS-14 for 30 min. Remaining surface biotinylation was stripped using glutathione. Biotinylated proteins were precipitated using streptavidin-agarose. Subsequently, glycosylated proteins were precipitated using wheat germ lectin-agarose beads. The levels of biotinylated sst2A receptors (upper panel) and total sst2A receptors (lower panel) were then determined by Western blot analysis using anti-sst2A antibody (UMB-1). Blots shown are representative of four independent experiments each. The positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated on the left (in kilodaltons).

Agonist-selective phosphorylation of rat and human sst2A receptors

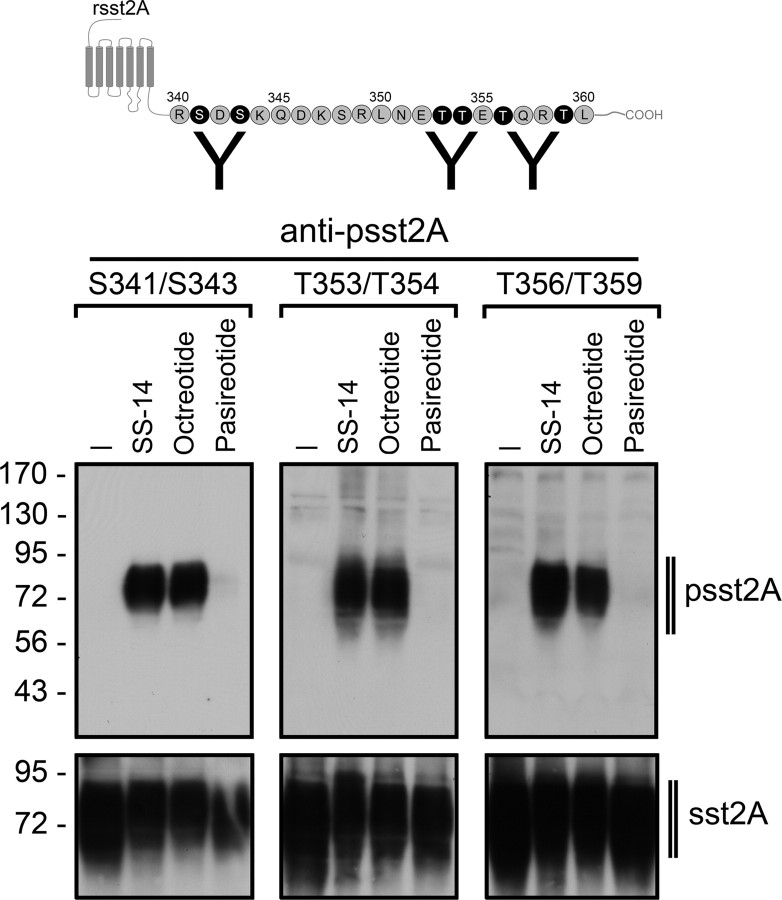

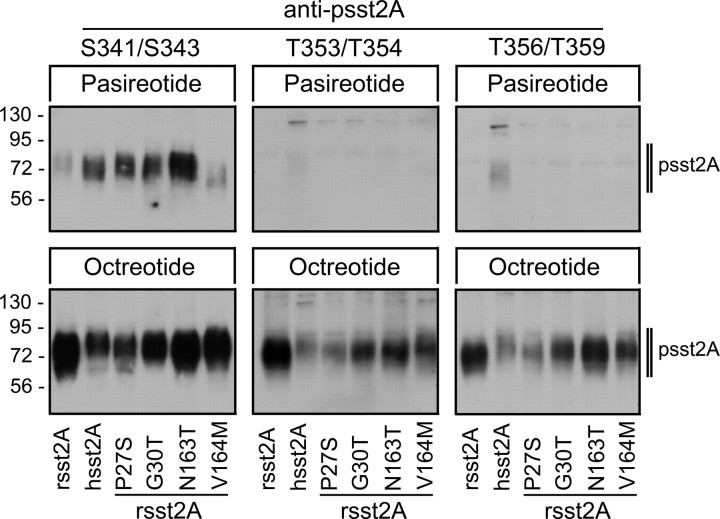

We have recently generated phosphosite-specific antibodies, which allowed us to detect the T353/T354-phosphorylated form as well as the T356/T359-phosphorylated form of the sst2A receptor (11). To facilitate a more complete analysis of agonist-induced sst2A phosphorylation, we generated an antibody against the S341/S343-phosphorylated form of the sst2A receptor (12). When human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells stably expressing the rat sst2A receptor were exposed to saturating concentrations of SS-14, octreotide, or pasireotide for 5 min, only SS-14 and octreotide were able to promote a robust phosphorylation of S341, S343, T353, T354, T356, and T359 (Fig. 4). In contrast, pasireotide failed to induce any detectable phosphorylation at these sites even after extended exposure (30 min), confirming that pasireotide activates the rat sst2A receptor without causing its rapid phosphorylation and internalization (11) (Fig. 4). We then examined pasireotide-induced phosphorylation of the human sst2A receptor (Supplemental Fig. 2). Unlike that observed at the rat sst2A receptor, pasireotide stimulated a selective phosphorylation of the serine residues S341 and S343. No phosphorylation was detected at the threonine residues T353, T354, T356, or T359 (Fig. 5). Thus, there appears to be a high degree of correlation between receptor phosphorylation and internalization, strongly suggesting that the selective serine phosphorylation is the underlying basis for the partial internalization of the human sst2A receptor after activation by pasireotide. Next, pasireotide-mediated phosphorylation of the internalizing single mutants of the rat sst2A receptor was examined. Like that observed with the human sst2A receptor, pasireotide stimulated a selective phosphorylation of the serine residues S341 and S343 in the P27S, G30T, and N163T mutants and, to a lesser extent, in the V164M mutant (Fig. 5). Again, octreotide and SS-14 induced a robust phosphorylation of all serine and threonine residues in all mutant receptors tested (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Agonist-selective phosphorylation of the rat sst2A receptor. Upper panel, Schematic representation of the rat sst2A receptor indicating potential phosphate acceptor sites (white letters in black circles) within the carboxyl-terminal tail. Lower panel, HEK293 cells stably expressing the rat sst2A receptor were either not exposed or exposed to 1 μm SS-14, 1 μm octreotide, or 10 μm pasireotide for 5 min. The levels of phosphorylated sst2A receptors (psst2A) were then determined using the phosphosite-specific antibodies anti-pS341/pS343 (3157), anti-pT353/pT354 (0521), or anti-pT356/pT359 (0522). Blots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with the phosphorylation-independent anti-sst2A antibody (UMB-1) to confirm equal loading of gels (sst2A). Note that SS-14 and octreotide stimulated a robust phosphorylation of all six phosphate acceptor sites, whereas pasireotide failed to promote any detectable phosphorylation of the rat sst2A receptor. The Western blots shown are representative of one of three independent experiments. The positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated on the left (in kilodaltons).

Fig. 5.

Pasireotide stimulates selective S341/S343 phosphorylation of the human sst2A receptor. HEK293 cells stably expressing rat sst2A, human sst2A, or internalizing mutants of the rat sst2A receptor were either not exposed or exposed to 10 μm pasireotide (upper panel) or 1 μm octreotide (lower panel) for 5 min. The levels of phosphorylated sst2A receptors (psst2A) were then determined using the phosphosite-specific antibodies anti-pS341/pS343 (3157), anti-pT353/pT354 (0521), or anti-pT356/pT359 (0522). Note that pasireotide stimulated a selective S341/S343 phosphorylation of the human sst2A receptor and the internalizing mutants of the rat sst2A receptor but not the wild-type rat sst2A. The Western blots shown are representative of one of five independent experiments. The positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated on the left (in kilodaltons).

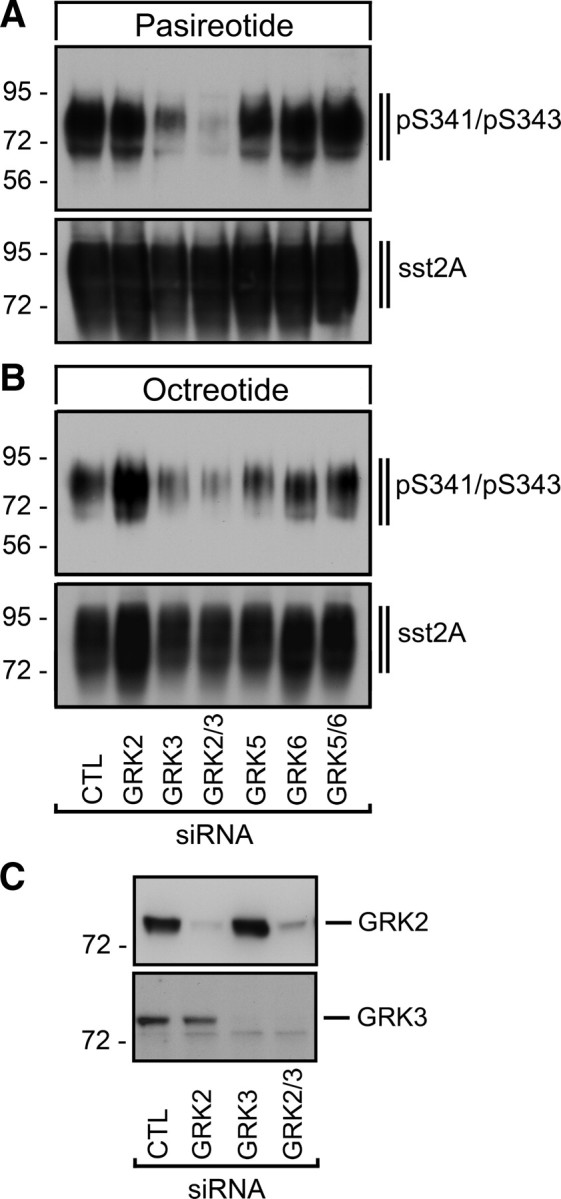

We have recently reported that the phosphorylation of the threonine residues T353, T354, T356, and T359 is mediated by G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRK) 2 and 3. Here we used a similar small interfering RNA (siRNA) approach to determine the kinase responsible for agonist-dependent phosphorylation of the serine residues S341 and S343. The results depicted in Fig. 6 show that both pasireotide- and octreotide-induced S341/S343 phosphorylation of the human sst2A receptor is predominantly mediated by GRK3. siRNA knockdown of GRK2, GRK5, or GRK6 had no effect on S341/S343 phosphorylation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

GRK3 is responsible for S341/S343 phosphorylation of the human sst2A receptor. HEK293 cells stably expressing the human sst2A receptor were transfected with siRNAs targeting GRK2, GRK3, GRK5, or GRK6 or nonsilencing siRNA control (CTL) for 72 h and then exposed to 10 μm pasireotide (A) or 1 μm octreotide (B) for 5 min. The levels of phosphorylated sst2A receptors (psst2A) were then determined using anti-pS341/pS343 antibody (3157). Blots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with the phosphorylation-independent anti-sst2A antibody (UMB-1) to confirm equal loading of gels (sst2A). C, GRK2 and GRK3 knockdown was confirmed in total cell lysates using specific anti-GRK2 and anti-GRK3 antibodies. The Western blots shown are representative of one of three independent experiments. The positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated on the left (in kilodaltons).

Discussion

Pasireotide was designed to imitate the broad SS-14 receptor binding and signaling profile of SS-14. However, recent evidence indicates that pasireotide displays functional selectivity (11, 13, 14). In fact, pasireotide and octreotide are equally active in inducing classical G protein-dependent signaling at the sst2A receptor. Yet, they promote strikingly different patterns of sst2A phosphorylation, internalization, and ß-arrestin trafficking (11). Whereas octreotide and SS-14 promote the phosphorylation of at least six carboxyl-terminal serine and threonine residues of the rat sst2A receptor, pasireotide fails to induce any substantial phosphorylation or internalization. These findings suggest that distinct active conformations of the rat sst2A receptor exist. Octreotide and SS-14 stabilize an active conformation, which facilitates both G protein activation and recruitment of GRK2/3. The conformational change induced by pasireotide allows G protein activation but does not permit efficient phosphorylation by GRK2/3 (11).

In the present study, we uncover a species difference in the pasireotide-mediated phosphorylation and internalization of rat and human sst2A receptors. Unlike that observed with the rat sst2A receptor, pasireotide is able to stimulate a selective phosphorylation of S341 and S343 of the human sst2A receptor, which is followed by a clearly detectable receptor sequestration. Construction of receptor chimeras and a series of site-directed mutants led us to identify amino acids 27, 30, 163, and 164, which, when exchanged to their human counterparts, facilitated pasireotide-driven S341/S343 phosphorylation and internalization of the rat sst2A receptor. Conversely, exchange of these amino acids to their rat counterparts completely blocked the pasireotide-mediated internalization of the human sst2A receptor. However, it should be noted that SS-14 and octreotide did not discriminate between rat and human sst2A receptors and stimulated a full phosphorylation and internalization of all mutant sst2A receptors tested.

GPCRs are no longer thought to behave as simple two-state switches. Rather, agonist binding and activation of GPCRs is believed to occur through a series of conformational intermediates (15–17). Transition to these intermediate states involves disruption of noncovalent intramolecular interactions that stabilize the basal state of the receptor. Binding of structurally different agonists might entail the disruption of different combinations of these intramolecular interactions leading to different receptor conformations and differential effects on downstream signaling proteins. Amino acids 27 and 30 are located within the amino terminus close to transmembrane domain 1. Amino acids 163 and 164 are located near the cytoplasmic end of transmembrane domain 4. The most likely explanation for our findings is that these residues participate in pasireotide-induced, but not in SS-14-induced, sst2A activation. Conversely, octreotide appears to activate sst2A receptors by a mechanism virtually identical to that of SS-14. Thus, pasireotide and octreotide achieve varying efficacies for different signaling pathways by stabilizing particular sets of conformations that can interact with specific effectors.

In conclusion, we identify structural determinants involved in the agonist-selective regulation of sst2A receptor signaling and trafficking. Our results suggest that pasireotide activates the sst2A receptor via a molecular switch that is structurally and functionally distinct from that turned on during octreotide-driven sst2A activation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Pasireotide and octreotide were provided by Dr. Herbert Schmid (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland). SS-14 was obtained from Bachem (Weil am Rhein, Germany). Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin and streptavidin-agarose were obtained from Pierce (Bonn, Germany). The phosphorylation-independent rabbit monoclonal anti-sst2A antibody (UMB-1) and the phosphosite-specific sst2A antibodies anti-pT353/pT354 (0521) and anti-pT356/pT359 (0522) were generated and extensively characterized as previously described (11, 18). Phosphosite-specific polyclonal antisera that detect the S341- and S343-phosphorylated form of the sst2A receptor were generated against the following sequence: DGER(pS)D(pS)KQDK. This sequence contains two phosphorylated serine residues and corresponds to amino acids 337–347 of the rat and human sst2A receptor. The peptide was purified and coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. The conjugate was mixed 1:1 with Freund's adjuvant and injected into four rabbits (3155–3158) for antisera production. Animals were injected at 4-wk intervals, and serum was obtained 2 wk after immunizations beginning with the second injection. The specificity of the antisera was initially tested using dot blot analysis. For subsequent analysis, antibodies were affinity purified against their immunizing peptide using the SulfoLink kit (Pierce).

Generation of mutant sst2A receptors

Chimeras of rat and human sst2A receptors were generated by exchange of first 180 amino acids using the KpnI restriction site present in the DNA sequence of both receptors. For the rsst2AQ7P/F8L/P27S/G30T/N163T/V164M mutant, the following changes in the DNA sequence were made in rat sst2A receptor: at position 20–22 AGT to CAC, leading to an exchange of glutamine and phenylalanine to proline and leucine, respectively; at position 79 C to G and at position 88–89 GG to AC, leading to an exchange of proline and glycine to serine and threonine, respectively; and at position 488 A to C and at position 490 G to A, leading to an exchange of asparagine to threonine and valine to methionine, respectively. The same changes were introduced to generate individual single and double mutants of the rat sst2A receptor. For the hsst2AP7Q/L8F/S27P/T30G7T163N/M164V mutant, the opposite changes were made in the human sst2A receptor. All mutated DNA sequences were obtained from MWG Eurofins (Ebersberg, Germany) and introduced into the rat or human sst2A receptor using the KpnI restriction site.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells were obtained from the German Resource Centre for Biological Material (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). HEK293 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding for wild-type or mutant sst2A receptors using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Stable transfectants were selected in the presence of 400 μg/ml G418. Stable transfectants were characterized using radioligand-binding assays, Western blot analysis, and immunocytochemistry as described previously (19, 20). The level of sst2A receptor expression was approximately 900 fmol/mg membrane protein. All chimeras and mutants tested were present at the cell surface and expressed similar amounts of receptor protein (Supplemental Figs. 3 and 4). The IC50 values of SS-14, octreotide, and pasireotide are given in Supplemental Table 1, indicating that mutations had no major impact on ligand-binding affinity.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were grown on poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips overnight. After the appropriate treatment with SS-14, octreotide, or pasireotide, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) for 30 min at room temperature and washed several times. Specimens were permeabilized and then incubated with anti-sst2A (UMB-1) antibodies followed by Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany). Specimens were mounted and examined using a Zeiss LSM510 META laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany) (13).

Western blot analysis

Cells were plated onto 100-mm dishes and grown to 80% confluence. After the appropriate treatment with SS-14, octreotide, or pasireotide, cells were lysed in detergent buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 10 mm NaF, 10 mm disodium pyrophosphate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml bacitracin]. Glycosylated proteins were partially enriched using wheat germ lectin-agarose beads as described elsewhere (21–23). Proteins were eluted from the beads using SDS-sample buffer for 20 min at 60 C and then resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After electroblotting, membranes were incubated with phosphosite-specific antibodies anti-pS341/pS343 (3157), anti-pT353/pT354 (0521), or anti-pT356/pT359 (0522) at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml followed by detection using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham). Blots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with anti-sst2A (UMB-1) to confirm equal loading of the gels.

Surface biotinylation protection assay

Cells were plated onto 60-mm dishes and grown to 80% confluence. Cells were incubated with 0.8 mm sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin in PBS containing 2 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2 for 30 min at 4 C. After washing, biotinylation was stopped with ice-cold quenching buffer (Tris-buffered saline containing 100 mm glycine, 2 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm MgCl2). Quenching buffer was changed three times after 1 min. Cells were then washed with serum-free medium and either incubated for 30 min at 4 C or stimulated with SS-14, octreotide, or pasireotide at 37 C. To remove biotin from cell surface, cells were incubated with stripping buffer (0.3 m NaCl, 75 mm NaOH, 100 mm glutathione, 1 mm EDTA, 1% fetal calf serum) three times for 10 min. After washing, cells were lysed in detergent buffer followed by incubation with streptavidin-agarose overnight. Subsequently, glycosylated proteins were partially enriched using wheat germ lectin-agarose beads. Proteins were eluted from the beads using SDS-sample buffer for 20 min at 60 C and then resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After electroblotting, membranes were incubated with anti-sst2A (UMB-1) followed by detection using enhanced chemiluminescence.

Quantification of receptor internalization by ELISA

HEK293 cells expressing the T7-tagged rat sst2A receptor or the hemagglutinin-tagged human sst2A receptor were seeded onto poly-l-lysine-treated 24-well plates. The next day, the cells were preincubated with 1 μg/ml anti-T7 or anti-HA antibody for 2 h at 4 C. After the appropriate treatment with SS-14, pasireotide, or octreotide, cells were fixed and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit antibody for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the plates were developed with 2,2′-azinobis 3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid solution and analyzed at 405 nm using a microplate reader.

siRNA silencing of gene expression

Chemically synthesized double-stranded siRNA duplexes (with 3′-dTdT overhangs) were purchased from QIAGEN (Hilden, Germany) for the following mRNA targets: GRK2 (5′-CCGGGAGAUCUUCGACUCAUA-3′), GRK3 (5′-AAGCAAGCUGUAGAACACGUA-3′), GRK5 (5′-AGCGUCAUAACUAGAACUGAA-3′), and GRK6 (5′-AACACCUUCAGGCAAUACCGA-3′) and a nonsilencing RNA duplex (5′-GCUUAGGAGCAUUAGUAAA-3′). HEK293 cells were transfected with HiPerFect (QIAGEN) according to the instructions of the manufacturer for 3 d. Silencing was quantified by immunoblotting. All experiments showed protein levels reduced by more than or equal to 80%.

Radioligand-binding assay

Competition binding assays were performed on membrane preparations from stable transfected cells as described above. Cells were homogenized in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8) containing 3 mm EGTA and 5 mm EDTA, centrifuged (50,000 × g, 15 min) and washed twice. The resulting pellet was resuspended with 10 mm HEPES buffer (5 mm MgCl2; 5 μg/ml bacitracin, pH 7.5). Aliquots of crude membrane suspension were incubated with 0.05 nm [125I]Tyr11-SS-14 (specific activity: 74 TBq/mmol, PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA) for 45 min at room temperature. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting nonspecific binding, defined as that seen in the presence of 1 μm SS-14, octreotide, or pasitreotide, from total binding obtained with radioligand alone. For the determination of the IC50 values, SS-14, octreotide, or pasireotide was used in concentrations ranging from 10−12 m to 10−5 m. Incubation was terminated by addition of ice-cold buffer and rapid filtration through glass fiber filters. The filters were washed and dried. The radioactivity was determined using a γ-counter (COBRA, Packard Instruments, Meriden, CT). Data from ligand binding and EC50 were analyzed by curve fitting using GraphPad Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Acknowledgments

We thank Heidrun Guder, Marita Wunder, Heike Stadler (Jena, Germany), and Michaela Böx (Magdeburg, Germany) for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant SCHU924/10-3 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Grant 107721 from the Deutsche Krebshilfe.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

- G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- SDS

- sodium dodecyl sulfate

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- sst

- somatostatin receptor

- SS-14

- somatostatin.

References

- 1. Weckbecker G , Lewis I , Albert R , Schmid HA , Hoyer D , Bruns C. 2003. Opportunities in somatostatin research: biological, chemical and therapeutic aspects. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2:999–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donangelo I , Melmed S. 2005. Treatment of acromegaly: future. Endocrine 28:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oberg KE , Reubi JC , Kwekkeboom DJ , Krenning EP. 2010. Role of somatostatins in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumor development and therapy. Gastroenterology 139:742–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van der Hoek J , Lamberts SW , Hofland LJ. 2004. The role of somatostatin analogs in Cushing's disease. Pituitary 7:257–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruns C , Lewis I , Briner U , Meno-Tetang G , Weckbecker G. 2002. SOM230: a novel somatostatin peptidomimetic with broad somatotropin release inhibiting factor (SRIF) receptor binding and a unique antisecretory profile. Eur J Endocrinol 146:707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewis I , Bauer W , Albert R , Chandramouli N , Pless J , Weckbecker G , Bruns C. 2003. A novel somatostatin mimic with broad somatotropin release inhibitory factor receptor binding and superior therapeutic potential. J Med Chem 46:2334–2344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma P , Wang Y , van der Hoek J , Nedelman J , Schran H , Tran LL , Lamberts SW. 2005. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic comparison of a novel multiligand somatostatin analog, SOM230, with octreotide in patients with acromegaly. Clin Pharmacol Ther 78:69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boscaro M , Ludlam WH , Atkinson B , Glusman JE , Petersenn S , Reincke M , Snyder P , Tabarin A , Biller BM , Findling J , Melmed S , Darby CH , Hu K , Wang Y , Freda PU , Grossman AB , Frohman LA , Bertherat J. 2009. Treatment of pituitary-dependent Cushing's disease with the multireceptor ligand somatostatin analog pasireotide (SOM230): a multicenter, phase II trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pedroncelli AM. 2010. Medical treatment of Cushing's disease: somatostatin analogues and pasireotide. Neuroendocrinology 92(Suppl 1):120–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petersenn S , Schopohl J , Barkan A , Mohideen P , Colao A , Abs R , Buchelt A , Ho YY , Hu K , Farrall AJ , Melmed S , Biller BM. 2010. Pasireotide (SOM230) demonstrates efficacy and safety in patients with acromegaly: a randomized, multicenter, phase II trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:2781–2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pöll F , Lehmann D , Illing S , Ginj M , Jacobs S , Lupp A , Stumm R , Schulz S. 2010. Pasireotide and octreotide stimulate distinct patterns of sst2A somatostatin receptor phosphorylation. Mol Endocrinol 24:436–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu Q , Bee MS , Schonbrunn A. 2009. Site specificity of agonist and second messenger-activated kinases for sst2A somatostatin receptor phosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol 76:68–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lesche S , Lehmann D , Nagel F , Schmid HA , Schulz S. 2009. Differential effects of octreotide and pasireotide on somatostatin receptor internalization and trafficking in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:654–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cescato R , Loesch KA , Waser B , Mäcke HR , Rivier JE , Reubi JC , Schonbrunn A. 2010. Agonist-biased signaling at the sst2A receptor: the multi-somatostatin analogs KE108 and SOM230 activate and antagonize distinct signaling pathways. Mol Endocrinol 24:240–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kobilka BK , Deupi X. 2007. Conformational complexity of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28:397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosenbaum DM , Rasmussen SG , Kobilka BK. 2009. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 459:356–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wess J , Han SJ , Kim SK , Jacobson KA , Li JH. 2008. Conformational changes involved in G-protein-coupled-receptor activation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 29:616–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fischer T , Doll C , Jacobs S , Kolodziej A , Stumm R , Schulz S. 2008. Reassessment of sst2 somatostatin receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4519–4524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pfeiffer M , Koch T , Schröder H , Klutzny M , Kirscht S , Kreienkamp HJ , Höllt V , Schulz S. 2001. Homo- and heterodimerization of somatostatin receptor subtypes. Inactivation of sst(3) receptor function by heterodimerization with sst(2A). J Biol Chem 276:14027–14036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tulipano G , Stumm R , Pfeiffer M , Kreienkamp HJ , Höllt V , Schulz S. 2004. Differential β-arrestin trafficking and endosomal sorting of somatostatin receptor subtypes. J Biol Chem 279:21374–21382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mundschenk J , Unger N , Schulz S , Höllt V , Schulz S , Steinke R , Lehnert H. 2003. Somatostatin receptor subtypes in human pheochromocytoma: subcellular expression pattern and functional relevance for octreotide scintigraphy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:5150–5157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Plöckinger U , Albrecht S , Mawrin C , Saeger W , Buchfelder M , Petersenn S , Schulz S. 2008. Selective loss of somatostatin receptor 2 in octreotide-resistant growth hormone-secreting adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1203–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schulz S , Pauli SU , Schulz S , Händel M , Dietzmann K , Firsching R , Höllt V. 2000. Immunohistochemical determination of five somatostatin receptors in meningioma reveals frequent overexpression of somatostatin receptor subtype sst2A. Clin Cancer Res 6:1865–1874 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]