Abstract

Importance

Patients recently discharged from psychiatric inpatient services are at elevated risk of dying prematurely. National cohorts provide sufficient statistical power for examining cause-specific mortality in this population.

Objective

To comprehensively investigate premature mortality in a national cohort of recently discharged psychiatric patients at 15-44 years of age.

Design, setting, and participants

Cohort study of all persons born in Denmark during 1967-1996 (N=1,683,385). Participants were followed up from their 15th birthday until their date of death, emigration or December 31st 2011, whichever came first.

Exposures

First discharge from inpatient psychiatric care.

Main outcome measures

Incidence rates and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for all-cause mortality and for an array of unnatural and natural causes among discharged patients versus persons not admitted for psychiatric care. Our primary analysis considered risk within a year of first discharge.

Results

Compared to persons not admitted, discharged patients had an elevated risk for all-cause mortality within a year (IRR 16.2, 95% CI 14.5-18.0). Relative risk for unnatural death (IRR 25.0, 95% CI 22.0- 28.4) was much higher than for natural death (IRR 8.6, 95% CI 7.0-10.7). The highest IRR found was for suicide: IRR 66.9, 95% CI 56.4-79.4; the IRR for alcohol-related deaths was the second highest observed: IRR 42.0, 95% CI 26.6-66.1. Among the psychiatric diagnostic categories assessed, psychoactive substance abuse conferred the highest risk for all-cause mortality (IRR 24.8, 95% CI 21.0-29.4). Across the array of cause-specific outcomes examined, risk of premature death during the first year post-discharge was markedly elevated compared to longer term follow up.

Conclusions and relevance

Enhanced liaison between primary and secondary health services post-discharge, as well as early intervention programs for drug and alcohol misuse could substantially decrease the greatly elevated mortality risk among recently discharged psychiatric patients.

Introduction

Mental disorders are associated with an elevated risk of premature mortality.1–3 The inpatient psychiatric population has been shrinking in size in western countries for several decades,4–7 thereby shifting patients’ treatment to the community or other institutional settings.8 Consequently patients who have experienced inpatient psychiatric care are generally the most severely ill individuals with a markedly elevated risk of dying prematurely.9 Existing evidence from national registry studies strongly indicates that mortality risk is especially elevated soon after discharge from inpatient psychiatric services.10,11 Previous study populations have differed in terms of country and regional settings, study designs, mortality outcomes assessed, and types of individuals examined. Thus, whereas some studies utilized national registry data with large numbers of discharged patients analyzed10–13 other investigations based their smaller studies on a single hospital or a small sample of units.14–16

This investigation, conducted in a national cohort of younger persons, focused on the first year post-discharge as opposed to longer-term follow-up.13,15 Furthermore, in contrast to previous research11,14 we considered a broad array of psychiatric diagnostic categories, including substance abuse disorders. We conducted a comprehensive examination of cause-specific mortality risk among recently discharged inpatients through assessment of the following mortality outcomes:

-

1)

All-cause mortality

-

2)

All unnatural and all natural deaths

-

3)

Suicide; accidental death

-

4)

Specific natural causes

-

5)

Alcohol-related death

Examination of alcohol-related death was an especially novel feature of the investigation. Consistent with existing literature we hypothesized mortality risk to be highest during the period soon after discharge.10,16 To maximize clinical relevance we primarily considered risk within a year of first discharge, but to better understand and contextualize short-term risk we also examined mortality beyond the first year up to a maximum follow-up of 30 years. We also hypothesized elevated risk across the full range of cause-specific mortality, and we anticipated relative risk for unnatural death to be greater than that for natural death.11–13,16

Methods

Study cohort description

Approval for the study was granted by the Danish Data Protection Agency and data access was agreed by the State Serum Institute and Statistics Denmark. Since this project was conducted using only registry data, it did not need approval from the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics. Information was extracted from the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS). The CRS has captured vital status information on all Danish residents since 1968 and can be linked accurately with other national registers using personal identification numbers issued at birth or on immigration.17 At individual level, we linked CRS data with information from the Danish Psychiatric Central Register18 and the Danish Register of Causes of Death.19 For further information regarding the study data, please see the Supplement (‘Additional information concerning the validity of Danish national registry data’; page 4). In accordance with the Danish Act on Processing of Personal Data, anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained; for example, by replacing personal identification numbers with randomly generated identifiers in the study dataset.

Cohort members were persons born in Denmark between January 1st 1967 and December 31st 1996 who were alive and residing in the country at their 15th birthday (N=1,683,385) with both of their parents also Danish-born, to eliminate potential for confounding due to elevated psychopathology risk among immigrants.20 Persons discharged from inpatient psychiatric care at least once before their 15th birthday (n=5882), were excluded. Follow-up commenced on cohort members’ 15th birthdays and was terminated on their dates of death, emigration or December 31st 2011, whichever came first, to a maximum age of 44 years. Within this single cohort design we identified individuals who experienced their first discharge from an inpatient psychiatric unit or a psychiatric ward in a general hospital during the study observation period from January 1st 1982 through December 31st 2011. We compared this exposure group to the remainder of the cohort without psychiatric admission, as explained in the ‘Statistical analyses’ subsection with further elaboration in the Supplement (‘Clarification of the cohort study design’; page 4).

Outcomes

Utilizing the Danish Register of Causes of Death we classified the underlying cause of death according to the International Classification of Diseases, 8th (ICD-8)21 and 10th (ICD-10)22 revisions. Unnatural death was delineated using ICD-8 E800-E999, ICD-10 V01-Y98; all other ICD-8 and ICD-10 cause of death codes denoted natural death. Accidental death was classified as ICD-8 E800-E949, ICD-10 V01-X59, Y85-Y86, suicide as ICD-8 E950-E959, ICD-10 X60-X84, Y87.0 and unnatural death of undetermined intent as ICD-8 E980-E989 (excl. E988.8), ICD-10 Y10-Y34 (excl. Y33.9),Y87.2. Alcohol-related death was delineated using ICD-10 F10, G31.2, G62.1, I42.6, K29.2, K70, K73, K74 (excl. K74.3-K74.5), K86.0, X45, X65, Y15, according to the England & Wales Office for National Statistics definition based on ICD-9 and ICD-10.23 Because ICD-9 was never implemented in Denmark we only included alcohol-related deaths assigned ICD-10 codes that occurred during 1994 and later. eTable 1 in the Supplement presents the standard coding ranges for classifying natural death according to ICD-8 and ICD-10 chapter headings.

Covariates

Time since first discharge, admission type (voluntary versus involuntary) and psychiatric diagnosis at first admission were obtained from the Psychiatric Central Research Register. Primary and secondary diagnoses were classified using ICD-8 and ICD-10 codes as in previous Danish registry studies, following the ICD-10 hierarchy24 as indicated in eTable 2 in the Supplement. We have reported separate relative risks according to these covariates; adjustment for the potential confounding influences of gender, age and period is explained in the next subsection.

Statistical analyses

We calculated incidence rates and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) to compare mortality risk following first discharge from inpatient psychiatric care versus persons not admitted (the reference group). For persons recorded as dying on the same day as their discharge date, we could not distinguish cases that happened before versus after discharge and we delineated these as occurring before discharge. Aggregated person-time was modelled using Poisson regression to estimate IRRs and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with adjustment for potential confounding by gender, and by age and calendar year fitted as time-dependent variables categorized as 5 year bands. All analyses, except for the comparison of ‘within 1 year’ versus ‘after 1 year’ post-discharge (Fig. 1), were restricted to deaths occurring within 365 days since first discharge. We tested for Poisson over-dispersion by additionally fitting negative binomial regression models25 and comparing them with the originally fitted Poisson models. After gender, age and calendar year adjustment, none of the models were over-dispersed (e.g. all-cause mortality among all persons: likelihood ratio test, p=0.50).

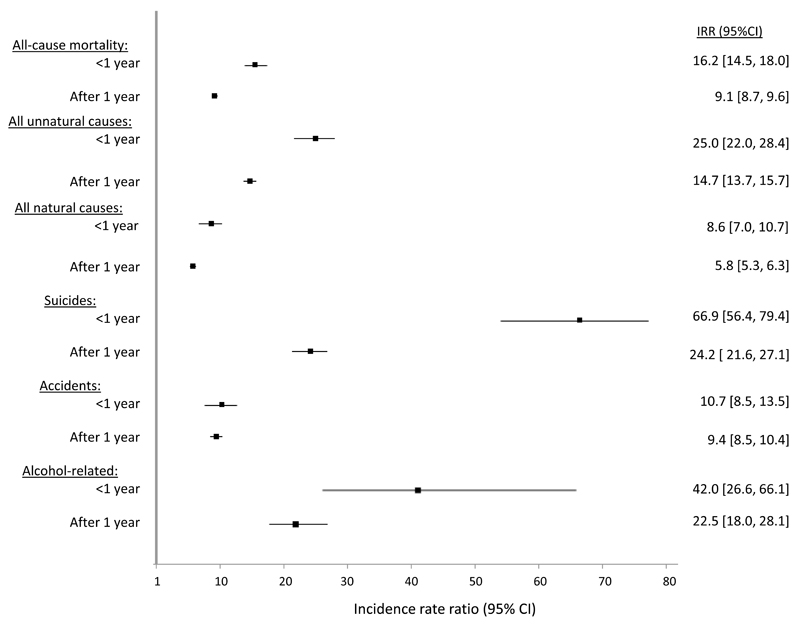

Figure 1.

Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for all-cause and cause-specific mortality within one year and after one year since first discharge compared to persons not admitted for psychiatric treatment

Results

Descriptive statistics

The cohort consisted of 1,683,385 persons of whom 48,599 were discharged from inpatient psychiatric care on or after their 15th birthday, 1982-2011. As reported in Table 1, there was a slight preponderance (51.4 percent) of females at first discharge, almost three-quarters of these patients (73.4 percent) were aged 15-29 years and most (70.0 percent) had a length of stay of 30 days or less. The overwhelming majority of discharged patients (93.9 percent) were admitted voluntarily, and a fifth (20.1 percent) had history of attempted suicide prior to their first discharge. eTable 3 in the Supplement additionally presents prevalence estimates for the physical illnesses delineated by the Charlson Comorbidity Index26 for persons discharged from inpatient psychiatric care as well as a randomly sampled age- and gender matched comparison group. The prevalence of these conditions was greater among the post-discharge group; the Supplement gives a description of the methods used to generate these results (on page 6).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the 48,599 individuals at first discharge from inpatient psychiatric care during the study period Jan. 1st 1982 - Dec. 31st 2011.

| Characteristic | n | % of Total (N=48,599) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 23,593 | 48.6 |

| Female | 25,006 | 51.4 |

| Age at first discharge (in years): | ||

| 15-19 | 12,345 | 25.4 |

| 20-24 | 13,503 | 27.8 |

| 25-29 | 9812 | 20.2 |

| 30-34 | 7222 | 14.9 |

| 35-39 | 4286 | 8.8 |

| 40 and older | 1431 | 2.9 |

| Psychiatric diagnostic category: | ||

| Psychoactive substance abuse | 10,208 | 21.0 |

| Schizophrenia and related disorders | 7469 | 15.4 |

| Mood disorders | 10,828 | 22.3 |

| Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders | 11,809 | 24.3 |

| All other disorders combined | 8285 | 17.0 |

| Comorbid mental illness + substance abuse diagnoses | 5427 | 11.2 |

| Type of admission:a | ||

| Voluntary | 45,643 | 93.9 |

| Involuntary | 2941 | 6.1 |

| Length of stay: | ||

| Up to 7 days | 21,247 | 43.7 |

| 8-30 days | 12,748 | 26.2 |

| 31 days to 6 months | 12,997 | 26.7 |

| More than 6 months | 1607 | 3.3 |

| History of attempted suicide before first dischargeb | 9750 | 20.1 |

Admission type was not recorded for n=15 persons, who were omitted from the denominator for this prevalence estimate

IRRs for all-cause mortality and for all unnatural and all natural deaths

People discharged from inpatient psychiatric services for the first time were at markedly elevated risk for dying prematurely versus individuals not admitted (Table 2). All-cause mortality risk was 16 times higher in the first follow-up year with no significant evidence of a gender difference (χ21 = 0.4, p=0.51). Discharged persons had a much greater elevation in risk for unnatural deaths compared to those not admitted, with women having a higher relative risk for this outcome than men (χ21 = 13.0, p<0.001). The relative risk of dying from natural causes was considerably lower than that observed for unnatural causes. Unlike unnatural causes, no marked gender difference in relative risk was observed in relation to natural deaths (χ21 = 0.0, p=0.95). Table 3 presents relative risks for all-cause mortality estimated separately according to salient clinical characteristics. Risks were highest among individuals who at first inpatient episode were diagnosed with psychoactive substance abuse disorders, and those admitted involuntarily; they were also greatest during the first post-discharge month. Patients with co-morbid substance abuse and a mental illness diagnosis were at higher risk versus those with a mental illness diagnosis only. Similar patterns were observed across these subgroups in relation to risk of dying either unnaturally or naturally, among persons at first discharge from inpatient psychiatric services versus individuals not admitted, as shown in eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement.

Table 2. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for all-cause mortality and for unnatural and natural death within one year after first inpatient discharge compared to persons not admitted.

| Discharged patients: N=48,599 |

Persons without psychiatric admission: N=1,634,786 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of deaths | Incidence rate per 100,000 person years | Number of deaths | Incidence rate per 100,000 person years | IRRa | 95% CI | ||

| All-cause mortality* | |||||||

| All persons | 340 | 777.9 | 12,769 | 49.7 | 16.2 | 14.5 | 18.0 |

| Male | 231 | 1090.8 | 9040 | 68.8 | 15.8 | 13.9 | 18.0 |

| Female | 109 | 483.8 | 3729 | 29.7 | 17.2 | 14.2 | 20.8 |

| Unnatural death§ | |||||||

| All persons | 245 | 560.6 | 6283 | 24.5 | 25.0 | 22.0 | 28.4 |

| Male | 174 | 821.7 | 5163 | 39.3 | 21.8 | 18.7 | 25.3 |

| Female | 71 | 315.1 | 1120 | 8.9 | 39.0 | 30.6 | 49.6 |

| Natural death* | |||||||

| All persons | 89 | 203.6 | 6037 | 23.5 | 8.6 | 7.0 | 10.7 |

| Male | 52 | 245.6 | 3535 | 26.9 | 8.7 | 6.6 | 11.4 |

| Female | 37 | 164.2 | 2502 | 19.9 | 8.6 | 6.2 | 11.9 |

Estimated incidence rate ratios were adjusted for gender, age and calendar year. Gender-specific incidence rate ratios were adjusted for age and calendar year

no significant interaction between outcome and gender

significant interaction between outcome and gender (p<0.001)

Table 3. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for all-cause mortality according to clinical subgroups within one year after first inpatient discharge compared to persons not admitted.

| Discharged patients: N=48,599 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical subgroups | Number of deaths | Incidence rate per 100,000 person years | IRR a | 95% CI | |

| All discharged patients | 340 | 777.9 | 16.2 | 14.5 | 18.0 |

| Time since discharge: | |||||

| 1-30 days | 59 | 1576.3 | 32.9 | 25.5 | 42.5 |

| 31-90 days | 69 | 945.3 | 19.7 | 15.5 | 25.0 |

| 91-180 days | 75 | 690.3 | 14.4 | 11.4 | 18.0 |

| 181-365 days | 137 | 628.5 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 15.4 |

| Psychiatric diagnostic category: | |||||

| Psychoactive substance abuse | 138 | 1493.7 | 24.8 | 21.0 | 29.4 |

| Schizophrenia and related disorders | 53 | 837.8 | 16.7 | 12.7 | 21.9 |

| Mood disorders | 52 | 535.6 | 12.3 | 9.4 | 16.2 |

| Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders | 54 | 494.5 | 11.0 | 8.4 | 14.3 |

| All other disorders combined | 43 | 572.4 | 13.6 | 10.1 | 18.3 |

| Mental illness and substance abuse co-morbidity: | |||||

| Mental illness diagnosis only | 202 | 588.7 | 13.1 | 11.4 | 15.1 |

| Substance abuse diagnosis only | 79 | 1723.7 | 27.5 | 22.1 | 34.4 |

| Mental illness + substance abuse diagnosis | 59 | 1226.1 | 21.2 | 16.4 | 27.3 |

| Type of admission: | |||||

| Voluntary admission | 295 | 717.4 | 15.1 | 13.4 | 16.9 |

| Involuntary admission | 45 | 1747.7 | 30.0 | 22.4 | 40.2 |

Estimated incidence rate ratios were adjusted for gender, age and calendar year

IRRs for cause-specific mortality

Of the 245 cases of unnatural death within a year of first discharge, most (146, 59.6%) were suicides (Table 4). Among all the specific causes examined, relative risk was also highest for suicide (IRR 66.9, 95% CI 56.4-79.4), with a strong gender interaction (χ21 = 24.5, p<0.001): females IRR 158.4, 95% CI 114.1-219.9; male IRR 52.9, 95% CI 43.1-65.0. Risk of dying accidentally was ten times higher versus persons not admitted, with no evidence for a gender interaction (χ21 = 0.6, p=0.42). For all other unnatural causes combined, the risk was 30 times higher among discharged persons with almost all of these 27 cases being deaths of undetermined intent. Compared to persons without psychiatric inpatient care, discharged patients were also at elevated risk for each type of natural death examined. The largest elevations in risk were observed for death by mental disorders, followed by diseases of the digestive system, then infections and parasitic diseases. Of the 13 recently discharged patients who died due to mental disorders, nine (69%) died from illicit drug and alcohol misuse or dependence syndromes (IRR 31.8, 95% CI 16.2-62.35), and most deaths (9 of 14, 64%) in the digestive system diseases chapter were from alcohol-induced conditions. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases accounted for most of the 7 deaths from infections and parasitic diseases among recently discharged inpatients (IRR 71.4, 95% CI 25.3-201.3). Due to the unavailability of HIV codes in ICD-8 this particular analysis was restricted to discharges occurring during 1994 and onwards. As was also seen among individuals not admitted, the highest natural-cause incidence rate observed among people recently discharged was for neoplasms (36.6 per 100,000 person-years at risk), although the elevation in risk was smaller than those found for most of the other natural-cause ICD chapters.

Table 4. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for death by specific causes within one year after first inpatient discharge compared to persons not admitted.

| Discharged patients: N=48,599 |

Persons without psychiatric admission: N=1,634,786 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific cause of death | Number of deaths | Incidence rate per 100,000 person years | Number of deaths | Incidence rate per 100,000 person years | IRR a | 95% CI | |

| Unnatural death: | |||||||

| Suicide | 146 | 334.1 | 1362 | 5.3 | 66.9 | 56.4 | 79.4 |

| Accident | 72 | 164.7 | 4395 | 17.1 | 10.7 | 8.5 | 13.5 |

| All other unnatural deaths combined | 27 | 61.8 | 526 | 2.0 | 30.3 | 20.6 | 44.7 |

| Natural death - by ICD chapter: | |||||||

| Infections and parasitic diseases | 7 | 16.0 | 239 | 0.9 | 21.0 | 9.9 | 44.6 |

| Neoplasms | 16 | 36.6 | 2191 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 7.0 |

| ENM diseases b | 8 | 18.3 | 358 | 1.4 | 12.6 | 6.2 | 25.3 |

| Mental disorders | 13 | 29.7 | 197 | 0.8 | 35.8 | 20.4 | 62.9 |

| Circulatory system diseases | 10 | 22.9 | 938 | 3.7 | 6.0 | 3.2 | 11.3 |

| Digestive system diseases | 14 | 32.0 | 273 | 1.1 | 28.9 | 16.9 | 49.4 |

| Unspecified conditions | 10 | 22.9 | 587 | 2.3 | 10.1 | 5.4 | 18.8 |

| All other natural causes combined | 11 | 25.2 | 1254 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 9.7 |

Estimated incidence rate ratios were adjusted for gender, age and calendar year;

Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases

IRRs within a year post-discharge versus long-term follow-up

Figure 1 compares relative risk of dying within a year post-discharge versus long-term follow-up, showing greater risk elevations during the first year for most cause-specific mortality categories. The greatest differential between short- and long-term follow-up was for suicide. This figure also presents large IRRs for alcohol-related death; the IRR point estimate for this category was almost twice as high within a year post-discharge versus long-term follow-up.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Our national cohort study comprehensively examined the full array of cause-specific mortality outcomes among patients recently discharged from inpatient psychiatric services. Discharged patients were at elevated risk for all types of mortality examined versus persons not admitted. The elevation in risk of unnatural death soon after discharge was much greater than that for dying naturally. Clinical subgroups with particularly high risk included persons admitted involuntarily, and those with substance abuse disorders. The greatest relative risk observed was for suicide, followed by alcohol-related death. Among the natural-cause ICD chapters, mental disorders and digestive diseases had the largest IRRs; these excess risks were largely explained by substance abuse disorders for the former chapter and alcohol-induced conditions for the latter. The large IRR for fatal infectious diseases can mainly be explained by a preponderance of HIV cases,27 although the number of observed deaths for this outcome was small. Death by neoplasm had the highest incidence among the natural-cause ICD chapters, but the elevation in risk compared to those not admitted was relatively modest with a 4-fold increased risk observed. Risk of dying within the first year following first discharge from inpatient psychiatric care was consistently greater than after one year, and the differential in relative risk between these two periods was especially marked for suicide.

Comparison with existing evidence and interpretation

Our findings mostly concur with the published literature on premature mortality among patients discharged from inpatient psychiatric services. Several studies have reported similar findings, showing discharged patients at higher risk for dying prematurely10–16 with the risk of unnatural death being higher than for natural death.11–13,16 This is mainly due to the hugely elevated suicide risk, as has also been observed previously.11–13,15,16 The tenfold increased risk for accidental death is congruent with reports of greatly elevated risk for this outcome among persons with mental illness per se,28–30 although this outcome has not been reported during the post-discharge period in any published studies to our knowledge. One possible explanation for elevated risk of accidental death in this population is comorbid substance abuse.28 Another factor might be sleeping problems and chronic fatigue, placing former inpatients at higher risk for serious accidents.31,32 The possibility of intentional self-poisonings being misclassified as accidents has also been highlighted previously.33

Elevated suicide and attempted suicide risks post-discharge have also been reported.10,34 Our study indicated that relative risks for suicide, and all of the other specific causes examined, decreased over time but remained elevated nonetheless compared to persons not admitted. Several possible explanations could potentially explain the increased risk post-discharge, including incomplete recovery, exposure to stress, decreased professional care, and ready access to means of suicide.10 Stigma surrounding psychiatric disorders, resulting in reluctance to seek professional help, have also been considered as factors contributing to suicide risk.35,36 In our study the time shortly after discharge was not only the period of highest suicide risk, but also for other unnatural and natural deaths. Among the psychiatric diagnostic categories examined, discharged patients with psychoactive substance abuse had the largest relative risks compared to those not admitted, and this was the case for dying unnaturally and naturally. Our findings in relation to specific natural causes of death indicate that a large proportion of post-discharge deaths are directly or indirectly attributable to substance abuse.

Our study has yielded valuable new knowledge regarding premature mortality risk from cancer among recently discharged psychiatric patients, given that contradictory results for this association have been reported previously.16,37,38 Although the relative risk compared to persons without psychiatric admission was the lowest among all the natural-cause ICD chapters, it was markedly elevated nonetheless in terms of the strength of association generally reported by studies of premature mortality in other contexts. Further research to identify the specific types of cancer most commonly linked with premature death post-discharge should be an important focus for future research.

Strength and limitations

The main strength of this study is that, for the first time, a comprehensive array of cause-specific mortality outcomes has been investigated in a national cohort across a range of psychiatric diagnostic categories. We utilized high-quality Danish registry data17 and, due to the size of the study cohort, we were able to report on rare causes of death with statistical power and precision. One important limitation was the restricted number of explanatory variables available, which is a common limitation of register-based studies.39 More specifically, we could not identify fatalities that happened on the same day that a person was discharged from inpatient psychiatric care, which may have caused a slight underestimate in the post-discharge relative risk estimates. Furthermore, we could not distinguish between psychiatric unit type (e.g. acute adult versus forensic), whether the patient was formally discharged or had absconded40 or whether they had been discharged into the community or to other institutional facilities. Also, although we investigated 48,599 persons following their first discharge from inpatient psychiatric care, our cohort lacked adequate power to examine more specific psychiatric diagnostic categories, such as unipolar depression versus bipolar disorder in the broader ‘mood disorders’ category. Finally, the maximum age at follow-up was age 44 years, which precludes application of our findings to middle-aged and older patients. Thus, for example, suicide is likely to be less numerically predominant as a cause of death among persons discharged from inpatient psychiatric care across the entire adult age range.11

Conclusion and relevance

This study adds value to the existing literature in several ways. First, we carried out the most comprehensive study of cause-specific mortality in this population conducted to date, which enabled us to examine even the rarest natural and unnatural cause-specific mortality outcomes. Second, we examined alcohol-related death, an outcome that is underrepresented in the literature. We also considered substance abuse disorder as a psychiatric diagnostic category, in contrast to previous studies that examined restricted sets of psychiatric diagnoses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.11 Lastly, we focused on premature mortality risk within a year post-discharge, the period of greatest clinical relevance.

The time shortly after discharge from inpatient psychiatric care is the period with the highest risk for premature death from a wide variety of causes. Clinicians should ensure the safety of discharged patients through enhanced liaison between primary and secondary healthcare services to provide holistic care accounting for patients’ physical and mental health needs as well as their psychosocial problems. Mental health services and their partner agencies need to work proactively and in unison to establish what risks are likely to re-emerge or become exacerbated at discharge, and to provide extra support to ameliorate the highly elevated risk of unnatural death. Patients with alcohol and drug use disorders and those admitted involuntary should be monitored particularly closely, and interventions targeting substance abuse should be offered to patients at early stages of their treatment with dedicated care coordinators ensuring appropriate levels of clinical surveillance. Given that risk is markedly elevated for so many causes of death, and especially so shortly after discharge, clinicians, academics and public health specialists must carefully consider the multiple mechanisms that are likely implicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Funding/Support

This study was funded by a Medical Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership PhD studentship awarded to Mr Walter and by a European Research Council Starting Grant (ref. 335905) awarded to Dr Webb.

Role of Funder

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None reported.

Access to Data and Data Analysis

Florian Walter (University of Manchester) has full access to all the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Joukamaa M, Heliövaara M, Knekt P, Aromaa A, Raitasalo R, Lehtinen V. Mental disorders and cause-specific mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179(6):498–502. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173(1):11–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salzer MS, Kaplan K, Atay J. State psychiatric hospital census after the 1999 Olmstead Decision: evidence of decelerating deinstitutionalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1501–1504. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salinsky E, Loftis C. Shrinking Inpatient Psychiatric Capacity: Cause for Celebration or Concern? George Washington University National Health Policy Forum Issue brief. 2007;(823):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS England. Bed Availability and Occupancy Data - Overnight. [Accessed December 16th, 2016];2010 Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/bed-availability-and-occupancy/bed-data-overnight.

- 7.Eurostat. Psychiatric Care Beds in Hospitals. [Accessed December 16th, 2016];2016 Available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/tps00047.

- 8.Lamb HR, Weinberger LE. The shift of psychiatric inpatient care from hospitals to jails and prisons. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(4):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crump C, Ioannidis JP, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Mortality in persons with mental disorders is substantially overestimated using inpatient psychiatric diagnoses. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(10):1298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin P, Nordentoft M. Suicide risk in relation to psychiatric hospitalization: evidence based on longitudinal registers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):427–432. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoang U, Stewart R, Goldacre MJ. Mortality after hospital discharge for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: retrospective study of linked English hospital episode statistics, 1999-2006. BMJ. 2011;343:d5422. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohlman B, Lehtinen V. Mortality among discharged psychiatric patients in Finland. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99(2):102–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb07207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stark C, MacLeod M, Hall D, O'Brien F, Pelosi A. Mortality after discharge from long-term psychiatric care in Scotland, 1977 – 94: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2003;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-3-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valevski A, Zalsman G, Tsafrir S, Lipschitz-Elhawi R, Weizman A, Shohat T. Rate of readmission and mortality risks of schizophrenia patients who were discharged against medical advice. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(7):496–499. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meloni D, Miccinesi G, Bencini A, et al. Mortality among discharged psychiatric patients in Florence, Italy. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1474–1481. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen V, Jacobsen BK, Arnesen E. Cause-specific mortality in psychiatric patients after deinstitutionalisation. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179(5):438–443. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen CB, Gotzsche H, Moller O, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53(4):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):54–57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):26–29. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantor-Graae E, Pedersen CB. Full spectrum of psychiatric disorders related to foreign migration: a Danish population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(4):427–435. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Classification of Diseases: Extended Danish-Latin version of the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, 8th revision, 1965. Copenhagen: Danish National Board of Health; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breakwell C, Baker A, Griffiths C, Jackson G, Fegan G, Marshall D. Trends and geographical variations in alcohol-related deaths in the United Kingdom, 1991-2004. Health Stat Q. 2007;(33):6–22. Spring. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573–581. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ver Hoef J, Boveng P. Quasi-Poisson vs. Negative Binomial Regression: How Should we Model Overdispersed Count Data? Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helleberg M, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB, Mortensen PB, Obel N. Associations between HIV and schizophrenia and their effect on HIV treatment outcomes: A nationwide population-based cohort study in Denmark. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(8):344–350. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Mental disorders and risk of accidental death. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(3):297–302. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.123992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiroeh U, Appleby L, Mortensen PB, Dunn G. Death by homicide, suicide, and other unnatural causes in people with mental illness: A population-based study. Lancet. 2001;358(9299):2110–2112. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black DW, Warrack G, Winokur G. The Iowa record-linkage study. I. Suicides and accidental deaths among psychiatric patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(1):71–75. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790240073007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Rae DS, West JC, Mojtabai R. Sleep problems, psychiatric hospitalization, and emergency department use among psychiatric patients with Medicaid. Psychiatric Serv. 2011;62(9):1101–1105. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.9.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Meltzer H. Clarifying the relationship between unexplained chronic fatigue and psychiatric morbidity: results from a community survey in Great Britain. American J Psychiatry. 2000;157(9):1492–1498. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergen H, Hawton K, Kapur N, Cooper J, Steeg S, Ness J, Waters K. Shared characteristics of suicides and other unnatural deaths following non-fatal self-harm? A multicentre study of risk factors. Psychol Med. 2012;42(4):727–741. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christiansen E, Jensen BF. A nested case-control study of the risk of suicide attempts after discharge from psychiatric care: the role of co-morbid substance use disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(2):132–139. doi: 10.1080/08039480802422677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dinos S, Stevens S, Serfaty M, Weich S, King M. Stigma: the feelings and experiences of 46 people with mental illness. Qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:176–181. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mann CE, Himelein MJ. Factors associated with stigmatization of persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(2):185–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kisely S, Crowe E, Lawrence D. Cancer-related mortality in people with mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(2):209–217. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mortensen PB. The occurrence of cancer in first admitted schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 1994;12(3):185–194. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mortensen PB, Allebeck P, Munk-Jørgensen P. Population-based registers in psychiatric research. Nordic J Psychiatry. 1996;50(36):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huber CG, Schneeberger AR, Kowalinski E, Frohlich D, von Felten S, Walter M, Zinkler M, Beine K, Heinz A, Borgwardt S, Lang UE. Suicide risk and absconding in psychiatric hospitals with and without open door policies: a 15 year observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(9):842–849. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1058–1064. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.