Abstract

Intestinal macrophages (mϕ) form one of the largest populations of mϕ in the body and are vital for the maintenance of gut homeostasis. They have several unique properties and are derived from local differentiation of classical Ly6Chi monocytes, but the factors driving this tissue-specific process are not understood. Here we have used global transcriptomic analysis to identify a unique homeostatic signature of mature colonic mϕ that is acquired as they differentiate in the mucosa. By comparing the analogous monocyte differentiation process found in the dermis, we identify TGFβ as an indispensable part of monocyte differentiation in the intestine and show that it enables mϕ to adapt precisely to the requirements of their environment. Importantly, TGFβR signalling on mϕ plays a crucial role in regulating the accumulation of monocytes in the mucosa, via mechanisms that are distinct from those used by IL10.

Keywords: Macrophage, colon, transforming growth factor β, differentiation, transcriptome

Introduction

Macrophages (mϕ) are present in most tissues of the body, where they scavenge dying cells, remodel tissues and act as sources of growth factors for neighbouring parenchymal cells and leukocytes 1. During infection or inflammation, they ingest and kill invading microbes and produce pro-inflammatory mediators 2. Despite many similarities, there is increasing evidence that mϕ in distinct steady state tissues differ in terms of ontogeny, phenotype and functions 3.

The discovery that the yolk sac mesenchyme, foetal monocytes and adult bone marrow (BM) derived monocytes could all generate resident mϕ led to the idea that tissue-specific differences amongst mature mϕ might reflect their origin from distinct precursors. Thus, while microglia are derived almost entirely from self-renewal of yolk sac precursors 4–6, alveolar mϕ, liver Kupffer cells and epidermal Langerhans cells are derived from foetal liver monocytes 5–7. Conversely, we have shown that intestinal mϕ require constant replenishment by BM-derived monocytes throughout adult life 8,9. Adult monocyte-derived mϕ are also present to different degrees in other tissues such as dermis 10, heart 11–13 and the serous cavities 14. However, more recent work makes it clear that developmental origin alone does not explain the heterogeneity seen amongst mϕ from different anatomical sites, as these have unique molecular signatures even when derived from the same progenitor 15. Furthermore, transcriptionally identical mϕ develop upon adoptive transfer into the neonatal lung, irrespective of the type of precursor used 16. Thus tissue-derived signals appear to be the principal determinant of resident mϕ fate.

The intestinal mucosa contains one of the largest populations of mϕ in the body 17. Although initially embryo-derived, intestinal mϕ are derived entirely from circulating Ly6Chi monocytes from the time of weaning onwards 9. Under steady state conditions, these monocytes differentiate through a series of short-lived intermediaries to generate mature mϕ characterised by expression of high levels of CD11b, MHCII, CX3CR1 and CD11c, production of IL10 and relative desensitisation to conventional stimuli 8,18,19. However, during inflammation this differentiation process is disrupted resulting in the accumulation of immature, pro-inflammatory cells 8,18,20,21. Thus the fate of Ly6Chi monocytes in the intestine is dependent on the context of the environment into which they arrive.

While recent studies have identified retinoic acid and CSF2/PPARγ ligands as local environmental signals that imprint the unique signature of peritoneal and alveolar mϕ respectively 7,22,23, the equivalent factors in the intestine have not been elucidated. Here we use global transcriptomic analysis to identify a unique genetic signature of steady state colonic mϕ that is acquired as they differentiate locally from Ly6Chi monocytes via a process known as the ‘monocyte waterfall’ 8,18. Through comparison to the analogous process found in the dermis, we identify TGFβR signalling as an indispensable part of monocyte differentiation in the gut and show that it allows intestinal mϕ to adapt precisely to the special requirements of their environment. By combining conditional TGFβR1-deficient mice with BM chimera models, we demonstrate that TGFβR signalling on mϕ limits monocyte recruitment to the mucosa, via mechanisms that appear distinct from those used by IL10.

Results

Transcriptomic Analysis of Colonic Macrophage Differentiation

To explore the processes that govern mϕ differentiation in the intestine, we first performed whole transcriptome array analysis of FACS purified mature CD64+CX3CR1hiLy6C–MHCII+ colonic mϕ and compared the results with published data sets for peritoneal, lung, brain, spleen and BM mϕ (Immgen Consortium), as well as with the mature dermal mϕ 10. Consistent with the idea that resident mϕ show tissue specific specialisation, the different populations clustered separately both when comparing entire transcriptomes (Figure 1a) or the 37 genes suggested to describe a mϕ ‘core signature’ 24 (Supplementary Figure 1a). Both approaches showed that colonic mϕ were more closely related to those from the dermis than to other tissue mϕ (Figure 1a and Supplementary Figure 1a). Further analysis revealed that 108 genes were differentially expressed by at least two-fold in colonic mϕ compared with all other tissue mϕ assessed and these can be considered as comprising a putative signature for colonic mϕ. They included Cd4 and the inhibitory receptor Il1r2, as well as genes that encode the tight junction proteins Amica1, Cdh17 and Cldn7, members of the Notch pathway (Hes1, Dtx3), Cxcl9, Tlr12 and the TGFβ superfamily receptor Tdgf1 (Supplementary Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Transcriptomic Analysis of the Monocyte-Macrophage Differentiation Series in Normal Colonic Mucosa.

(a) Hierarchical cluster analysis of mature colonic macrophages (CD11b+CD64+Ly6C– MHCII+CX3CR1hi) compared with macrophages from the lung, brain, bone marrow, spleen, peritoneal cavity and dermis (ANOVA; PRaw ≤0.05; PAdj ≤0.037). (b) Expression of Ly6C and MHCII by CD45+CD11b+CD64+ cells (upper panel) and expression of CX3CR1-GFP by the Ly6C– MHCII+ cells (lower panel) obtained from the colon of unmanipulated Cx3cr1+/GFP reporter mice. Data are representative of at least 20 independent experiments. (c) Global gene expression profile of Ly6C+MHCII– (P1), Ly6C+MHCII+ (P2), Ly6C–MHCII+CX3CR1int (P3) and Ly6C+MHCII–CX3CR1hi (P4) cells obtained from the colon of unmanipulated Cx3cr1+/GFP reporter mice (ANOVA; PRaw ≤0.05; PAdj ≤0.08). (d) Functionally-defined subsets of mRNA transcripts that are significantly downregulated during differentiation from the P1 to P4 stage in the colon of unmanipulated Cx3cr1+/GFP reporter mice. (Student’s t test; P ≤ 0.05; fold change ≥ 2.0). (e) Flow cytometric analysis of CCR2 and integrin β7 expression by P1-P4 subsets obtained from the colon and small intestine of unmanipulated Cx3cr1+/GFP reporter mice compared with the appropriate isotype control. Data are representative of 3-4 independent experiments. (f) Functionally-defined subsets of mRNA transcripts that are significantly upregulated during differentiation from the P1 to P4 stage in the colon of unmanipulated Cx3cr1+/GFP reporter mice. (Student’s t test; P ≤ 0.05; fold change ≥ 2.0). (g) Subset-specific expression of genes that are progressively upregulated from the P1 to P4 stages and expressed at least twofold higher by mature colonic macrophages compared with any of the tissue resident macrophage populations as in a above. (Student’s t test P≤0.05, fold change ≥ 2.0). (h) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of cell surface markers identified in f above by P1-P4 subsets obtained from the colon and small intestine of unmanipulated Cx3cr1+/GFP reporter mice compared with appropriate isotype controls. Data are representative of 3-4 independent experiments.

To gain further insight into how local factors shape the selective characteristics of mϕ in the intestine, we analysed the differentiation stages within the “monocyte waterfall” that generates intestinal mϕ from their monocyte precursors 8,9,18. In this scheme, newly arrived monocytes are Ly6ChiMHCII–CX3CR1int (P1), two intermediate subsets can be identified as Ly6ChiMHCII+CX3CR1int (P2) and Ly6C–MHCII+CX3CR1int (P3), and mature mϕ are Ly6C–MHCII+CX3CR1hi (P4) 8,18 (Figure 1b). Analysis of the transcriptomes of these phenotypic subsets in the colon revealed a clear progression in gene expression, consistent with them being components of a linear maturation continuum (Figure 1c). In total, 1004 genes changed by more than two-fold between newly arrived Ly6Chi monocytes (P1) and CX3CR1hi mature (P4) mϕ (Supplementary Table 1). Among the 391 genes that were downregulated were molecules involved in the chemotaxis and extravasation of monocytes, such as Ccr2, Sell (which encodes CD62L), Ly6c1, Gpr35 (CXCR8), Itga1 (VLA-1), Itgal (LFA-1) and Itgb7 (β7 integrin) (Figure 1d). Flow cytometry confirmed the decreasing expression of CCR2 and β7 integrin proteins during the maturation process in the colon and small intestine (Figure 1e and Supplementary Figure 2). Other highly downregulated genes included the pro-inflammatory factors Il6 and Trem1 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells) and adaptor proteins within the TLR activation pathway (Myd88, Irak3) (Figure 1d).

613 genes were upregulated in mature P4 mϕ compared with newly arrived P1 monocytes (Supplementary Table 1). Many of these were consistent with mature colonic mϕ having an important role in tissue homeostasis, as they included genes encoding receptors involved in the phagocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells (Mertk, Mrc1 (CD206), Cd36, Gas6, Axl, Itgav, Itgb5, Cd9, Cd81, C1qa-c), tissue remodelling metalloproteinases (Mmp2 and Mmp9), monocyte chemoattractants (Ccl7 and Ccl8) and components of the complement cascade (Figure 1f). Other highly upregulated genes were members of the TGFβR signalling pathway (Tgfbr1/2, Smad7) and genes encoding molecules already known to be highly expressed by colonic mϕ, including Cx3cr1, MHCII associated H2-M2, Itgax (CD11c), Emr1 (F4/80), and Il10 (Figure 1f). 42 of these upregulated genes were amongst the 108 genes identified above as being expressed at ≥ 2-fold higher levels by colonic mϕ than in any other tissue mϕ (Figure 1g and Supplementary Figure 1b), thus identifying a signature of monocyte differentiation that is specific to the colonic mucosa. Flow cytometry confirmed the increasing expression of surface proteins corresponding to a number of genes regulated during the maturation process, with comparable changes being observed in the colon and small intestine (Figure 1h and Supplementary Figure 2). However this also showed that while some receptors such as αvβ5 integrin, CD274 and CD9 were upregulated progressively through the monocyte waterfall, others such as CD63 and CD4 only appeared on fully mature CX3CR1hi mϕ (Figure 1h). Thus the changing expression of the genes that mark intestinal mϕ differentiation is not an entirely synchronous process.

Together these findings support the idea that tissue specific signals drive intestinal mϕ to acquire a specific homeostatic signature as they differentiate from monocytes.

The Colonic Environment Shapes a Tissue Specific Programme of Monocyte-Macrophage Differentiation

To explore the mechanisms involved in this specific developmental process in the colon, we repeated our analysis of different tissue mϕ, this time focussing on the 1004 genes that were significantly up- or down-regulated during the transition from monocytes to resident mϕ in the colon (Supplementary Table 1). In this way, we aimed to identify those genes whose regulation was selective for differentiation in the colon, as opposed to being part of generic mϕ development. This approach showed that colonic mϕ cluster closely with skin dermal and lung interstitial mϕ (Figure 2a), populations that are also replenished by BM-derived monocytes 10,14. Indeed a ‘monocyte waterfall’ containing short-lived P1, P2 and P3 subsets is also present in the steady state dermis (Supplementary Figure 3a) 10. In contrast to the colon, the mature mϕ compartment of the dermis contains both MHCII– (designated dermal P4) and MHCII+ (dermal P5) cells. We reasoned that transcriptional differences between the various stages within the monocyte-mϕ continuum in the colon and dermis could reveal factors specific to the colonic environment. Principal component analysis of the individual subsets within the ‘monocyte waterfall’ from the colon and the dermis showed progressively increasing transcriptional distance between each phenotypically defined stage and Ly6Chi blood monocytes, consistent with a putative linear relationship between each subset within its own tissue (Figure 2b). Importantly however, the equivalent subsets in colon and dermis became increasingly separate as they progressed through development, suggesting that a tissue-dependent programme determined the eventual outcome of monocyte differentiation.

Figure 2. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of Monocyte-Macrophage Differentiation in the Colonic Mucosa and Dermis.

(a) Hierarchical cluster analysis of mature colonic macrophages (CD11b+CD64+Ly6C– MHCII+CX3CR1hi; P4) and macrophages from the lung, brain, bone marrow, spleen, peritoneal cavity and dermis based on the 1004 genes that show a greater than twofold increase in expression between P1 and P4 in the colon (Supplemental Table 1). (b) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of gene expression by Ly6Chi blood monocytes, P1-P4 subsets from steady state colon and P1-P5 subsets from steady state dermis identified as in Supplementary Figure 2. Numbers in parentheses indicate the relative scaling of the principal variables (ANOVA; PRaw ≤0.05; PAdj ≤0.14). (c) Overlapping and differentially expressed genes that are significantly upregulated (upper panel) and downregulated (lower panel) between P1 and P4 in the colon and P1 and P5 in the dermis. (Student’s t test; P ≤ 0.05; fold change ≥ 2.0; comparing colonic P1 vs P4 and dermal P1 vs P5 respectively). (d) TGFβR pathway-associated genes regulated during colonic macrophage differentiation identified by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis expressed by P1-P4 subsets in colon (C) and P1-P5 subsets in the dermis (D). (KEGG Database; PRaw =0.0031; PAdj ≤0.0107).

Although a substantial number of genes showed significant changes in expression between newly arrived monocytes and mature MHCII+ mϕ in both the colon and dermis (1004 and 838 genes respectively; Supplementary Table 2), only 240 of the upregulated and 147 of the downregulated genes were common to the two tissues (Figure 2c). Because the developmental origin and relationship of the MHCII– and MHCII+ mϕ in the dermis is unclear, and there is no analogous MHCII– population in the adult colon, we omitted dermal MHCII– mϕ from these analyses. Among the shared downregulated genes were those involved in extravasation of monocytes such as Sell (CD62L), Ly6c1 (Ly6C), Itgb7 (β7 integrin) and proinflammatory molecules like Trem1. Among the shared upregulated genes were Il10, H2-M2, Mrc1 (CD206), Mertk, Gas6, C1qb, C1qc, C1qa, Cd163 and Itgax (Supplementary Table 2). 373 genes were selectively upregulated by maturing monocytes in the colon, and 163 of these genes were expressed by two-fold or more by fully mature colonic mϕ (P4) compared with their MHCII+ (P5) equivalents in the dermis (Figure 2c, upper panel, Supplementary Table 2). These genes seem to comprise a cassette selectively imprinted in mature mϕ by the colonic tissue environment (Supplementary Table 2).

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis highlighted the TGFβR signalling pathway as a potential candidate for driving the colonic differentiation process. Genes belonging to this pathway were enriched amongst the 1004 genes that define mϕ maturation in the colon (Supplementary Table 3). A set of these genes was also amongst those upregulated selectively during the differentiation of monocytes into mature mϕ in the colon but not in the dermis. These included Tgfbr1, Bmp2, Smad7 and Tgfb3 (Figure 2d). Together these findings indicate that the tissue specific properties of colonic mϕ reflect the outcome of selective differentiation of monocytes, driven by the local environment and that this process may involve TGFβR signalling.

TGFβR1 Signalling Regulates Monocyte Accumulation in the Colon

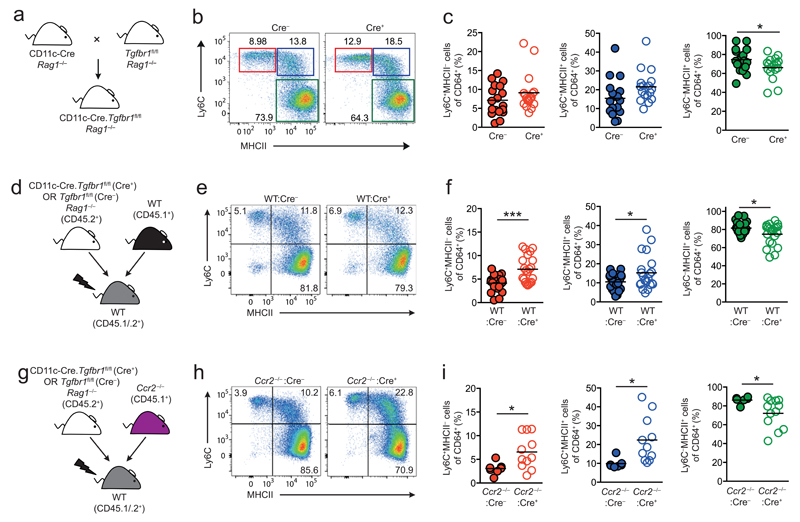

To investigate whether TGFβR signalling contributed to colonic mϕ development in vivo, we examined mice that lack Tgfbr1 on CD11c+ cells using CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/fl mice, as in our hands, most colonic mϕ express CD11c at significant levels 9. These mice were maintained on a Rag1–/– background (Figure 3a) to circumvent the fatal multi-organ inflammation that occurs due to Cre recombinase activity in a small subset of T cells in CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/fl mice {Bain, Montgomery et al, Unpublished observations}. Histology of the colonic tissue isolated from CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/flRag1–/– mice confirmed the absence of intestinal inflammation (data not shown). Analysis of CD11c-Cre-Rosa26-LSL-eYFP reporter mice confirmed efficient CD11c driven Cre recombinase activity in both CD64– DC and CD64+Ly6C–MHCII+ mϕ in the colon, the latter being the equivalent of the P3+P4 subsets defined in Cx3cr1+/GFP mice. In contrast, there was little or no Cre activity in Ly6ChiMHCII– P1 monocytes, their Ly6ChiMHCII+ P2 descendants or in other CD11clo/– cells in the mucosa including eosinophils (Supplementary Figure 4b, c). Analysis of CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/flRag1–/– mice revealed a trend towards more Ly6C+MHCII– P1 and Ly6C+MHCII+ P2 cells, together with significantly fewer mature Ly6C–MHCII+ mϕ amongst CD64+ cells in the colon of Cre+ compared with Cre– mice (Figure 3b,c). To assess the impact of TGFβR deficiency in a competitive environment, we next generated mixed BM chimeric mice. Lethally irradiated CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipients were reconstituted with a mixture of BM from WT (CD45.1+) and Cre– or Cre+ Tgfbr1fl/fl (CD45.2+) mice (Figure 3d). Under these conditions, WT and both types of Tgfbr1fl/fl BM were able to generate monocyte-mϕ subpopulations in the colonic mucosa (Supplementary Figure 5a). However, the Cre+ BM showed a small, but significant reduction in the generation of mature Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3/P4) mϕ compared with WT BM, a competitive disadvantage consistent with the presence of CD11c and therefore active Cre recombinase expression on these mature mϕ. Analysis of the monocyte waterfall in the mixed BM chimeras showed that there were significantly higher frequencies of P1 and P2 cells, together with fewer Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3/P4) mϕ in the colon of WT:Cre+ chimeras compared with their WT:Cre– controls (Figure 3e and f). Interestingly, these changes in the monocyte-mϕ continuum were not due to an intrinsic loss of TGFβR1 signalling, as both Tgfbr1fl/fl- and WT-derived P1 and P2 cells were over-represented in WT:Cre+ chimeras (Supplementary Figure 5b).

Figure 3. TGFβR1 Signalling Regulates Monocyte Accumulation in the Colon.

(a) Schematic representation of the CD11c-Cre. Tgfbr1fl/fl strain. (b) Representative expression of Ly6C and MHCII by live CD45+CD11b+CD64+ cells from the colon of CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre+) or Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre–) littermate controls. (c) Frequency of Ly6C+MHCII– (P1), Ly6C+MHCII+ (P2), Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3+P4) among CD64+ cells from the colon of CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre+) or Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre–) littermate controls. Symbols represent individual animals and horizontal bar is the mean of n=17 (Cre+) or 18 (Cre–) mice pooled from 5 independent experiments. *P<0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test. (d) Schematic representation of the generation of mixed WT:Cre– and WT:Cre+ BM chimeric mice. (e) Representative expression of Ly6C and MHCII by live CD45+CD11b+CD64+ cells from the colon of WT:Cre– and WT:Cre+ mixed BM chimeras. (f) Frequency of Ly6C+ MHCII– (P1), Ly6C+ MHCII+ (P2), Ly6C– MHCII+ (P3+P4) cells among CD64+ cells from the colon of WT:Cre– and WT:Cre+ BM chimeric mice. Symbols represent individual animals and horizontal lines are the means of 21 mice per group and are pooled from 5 independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 as determined by Student’s t-test. (g) Schematic representation of the generation of mixed Ccr2–/–:Cre– and Ccr2–/–:Cre+ BM chimeric mice. (h) Representative expression of Ly6C and MHCII by live CD45+CD11b+CD64+ cells from the colon of Ccr2–/–:Cre– and Ccr2–/–:Cre+mixed BM chimeras. (i) Frequency of Ly6C+MHCII– (P1), Ly6C+MHCII+ (P2), Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3+P4) cells among CD64+ cells from the colon of Ccr2–/–:Cre– and Ccr2–/–:Cre+ mixed BM chimeras. Data are from 7 (Ccr2–/–:Cre–) or 11 (Ccr2–/–:Cre+) mice per group and are pooled from 3-4 independent experiments. *P<0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test.

To assess whether these effects were due to deletion of TGFβR1 on cells of the monocyte/mϕ lineage as opposed to other CD11c+ cells, we generated BM chimeras in which complete TGFβR1 deficiency was restricted to this lineage. Lethally irradiated CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipients were reconstituted with a 50:50 mix of BM from Ccr2–/– (CD45.1+) and Cre– or Cre+ Tgfbr1fl/fl (CD45.2+) mice (Figure 3g). Consistent with our previous findings that intestinal mϕ require constant replenishment by CCR2-dependent precursors 9,18, the colonic mϕ compartment in these animals was derived almost completely from the Tgfbr1fl/fl donor (Supplementary Figure 5c). In contrast, CCR2-independent cells such as eosinophils were derived equally from both BM sources (Supplementary Figure 5c). The Ccr2–/–:Cre+ chimeras recapitulated the increased frequencies of immature P1 and P2 cells, and fewer Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3/P4) mϕ (Figure 3h and i). As in the intact CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/flRag1–/– mice, there was no histological evidence of intestinal inflammation in the Ccr2–/–:Cre+ chimeric mice, indicating this was not responsible for the changes in the waterfall (Supplementary Figure 5d). Dendritic cell subsets were present in comparable frequencies in the two groups of CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/fl x Ccr2–/– chimeric mice (Supplementary Figure 5e). Thus the dysregulated monocyte-mϕ continuum in the absence of TGFβR-mediated signalling in CD11c+ cells is due to an effect on mature mϕ, rather than secondary to changes in the DC compartment.

TGFβR1 Dependent Signalling Shapes Intestinal Macrophage Differentiation

To assess the impact of Tgfbr1 deficiency on colonic mϕ differentiation in more detail, we compared the transcriptome of mature CD64+Ly6C–MHCII+ mϕ from Cre– and Cre+ mice, focussing on the 1004 genes that we found to define monocyte to mϕ differentiation in the colon (Supplementary Table 1). Of these, 115 were differentially expressed by at least 1.5-fold in Cre+ compared with Cre– mice (Figure 4a and Supplementary Table 4). Notably, among those upregulated was the monocyte chemoattractant Ccl8, which could explain the increased abundance of P1 and P2 cells we observed in CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/flRag1–/– and both BM chimeric systems (Figure 4a and b). Indeed CCL8 is reported to be preferentially produced by CD169+ mature macrophages in the colon 25 and we observed increased frequencies of CD169+ macrophages amongst CD64+Ly6C–MHCII+ mϕ from WT:Cre+ mice compared with control WT:Cre– mice (Figure 4c). Analysis of WT:Cre+ mice confirmed that the increased abundance of CD169+ cells was due to loss of cell-intrinsic TGFβR signalling (Figure 4d).

Figure 4. TGFβR1 Dependent Signalling Shapes Colonic Macrophage Differentiation.

(a) Volcano plot comparing the expression of genes that show a greater than twofold change in expression between P1 and P4 in the colon (Supplementary Table 1) by CD11b+CD64+Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3+P4) macrophages from CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre+) or Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre–) littermate controls. Selected genes with fold change ≥ 1.5 and PRaw ≤ 0.05 are highlighted, while genes with fold-change of <1.5 are shown in grey (see also Supplemental Table 2). The dashed line represents the border for PRaw ≤ 0.05. (b) Expression of Ccl8 by Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3+P4) cells from the colon of CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre+) or Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre–) littermate controls. Data are the mean normalised probe intensity + 1 sd taken from the microarray analysis shown in a with 3 biological replicates per group. *P<0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test. (c) Frequency of CD169+ cells amongst Tgfbr1fl/fl-derived (CD45.2+) Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3+P4) cells from the colon of WT:Cre– and WT:Cre+ mixed BM chimeras. (d) Frequency of Tgfbr1fl/fl-derived CD169+ Ly6C– MHCII+ (P3+P4) cells presented as a ratio of their WT-derived counterparts from the same colon of WT:Cre– and WT:Cre+ mixed BM chimeras. Bars represent the means of 6 mice per group + s.d. and are pooled from 2 independent experiments. **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 as determined by Student’s t-test. (e) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Tgfbr1, Cx3cr1 and Il10 mRNA in CD11b+CD64+Ly6C– MHCII+ (P3+P4) colonic macrophages from the colon of CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre+) or Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre–) littermate controls. Data are from one experiment with three biological replicates. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 as determined by Student’s t-test. (f) Flow cytometric validation of αvβ5, αv and CD9 expression by P1, P2 and P3+P4 cells from the colon and small intestine of CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre+) or Tgfbr1fl/fl (Cre–) littermate controls (upper panels). MFI are shown for individual animals and horizontal lines represent the mean (lower panels). Data are from one experiment (CD9 for colon and small intestine, αvβ5, αv for small intestine) or pooled from two independent experiments (αvβ5, αv for colon) with 2-7 mice per group. **P<0.01 determined by Mann Whitney test. (g) Expression of TGFβR-dependent genes in a above by the P1-P4 subsets from the colon (C) or P1-P5 subsets from the dermis (D). The genes listed are those expressed at least twofold higher in colon P4 compared with dermal P5 cells. (h) Clustering analysis of tissue macrophage populations based on the TGFβR-dependent module as in a above. The genes listed are those from the highlighted cluster that show overlapping expression between microglia and colonic macrophages. Genes highlighted in red represent genes that have been reported previously as ‘microglia specific’ 24,26.

Amongst those genes downregulated in the absence of TGFβR1 signalling were Hes1, Il22ra2 and Tlr12, genes we had found to be selectively enriched in colonic mϕ compared with all other tissue mϕ (Figure 4a, Supplementary Figure 1b). mRNA transcripts for Itgav, Itgb5, Cd9 and Cx3cr1 were also expressed at significantly lower levels in mature Cre+ mϕ, findings that were confirmed by RT-qPCR or flow cytometric analysis of for αv, αvβ5 and CD9 expression by small intestinal and colonic macrophages (Figure 4e and f). Notably, RT-qPCR analysis showed lower levels of Il10 mRNA transcripts in Tgfbr1–/– mϕ compared with their Tgfbr1-sufficient counterparts (Figure 4e). We then used the group of genes that differed between Cre+ and Cre– mϕ to interrogate the differentiation continuums in wild type colon and dermis. This identified a set of TGFβR-dependent genes that appeared to define the colon specific differentiation of monocytes (Figure 4g). Interestingly, clustering of all tissue mϕ based on the TGFβR-dependent genes revealed similarity between colonic mϕ and microglia (Figure 4h). Indeed, several genes reported previously to be ‘microglia-specific’ (e.g. Tmem119, Olfml3, Spata13 and Siglech) 24,26, were highly expressed by colonic mϕ (Figure 4a and h).

Thus TGFβR signalling is critical for the acquisition of the characteristic traits of mature homeostatic intestinal mϕ as they differentiate from monocytes.

TGFβ and IL10 imprint non-overlapping features of colonic Mϕ

One of the most characteristic features of mature intestinal mϕ is that during their development from monocytes they become hyporesponsive to stimulation with TLR ligands 8,21,27. While IL10 receptor signalling has been shown to be involved in this in vivo 28–31, experiments with human mϕ have suggested that it may be induced by TGFβ in vitro 19,32. To investigate this role of TGFβR signalling in vivo, we assessed cytokine production by mϕ from the colon of WT:Cre–/Cre+ mixed BM chimeric mice in the presence and absence of TLR4 ligation by LPS. This revealed no changes in TLR4 responsiveness, as cytokine production was increased to a similar extend by LPS stimulation in Cre– and Cre+ macrophages (Figure 5b). However, as in intact CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/fl Rag1–/– mice, resting colonic mϕ derived from Tgfbr1–/– BM had reduced levels of mRNA for IL10 compared with their Tgfbr1+/+-derived counterparts and this was confirmed by intracellular cytokine staining (Figure 5a and b). Interestingly, resting Tgfbr1–/–-derived mϕ also expressed lower levels of TNFα protein (Figure 5b). These differences in IL10 and TNFα production were maintained after stimulation via TLR4 (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. TGFβ and IL10 Imprint Non-overlapping Features of Colonic Macrophages.

(a) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Tgfbr1, Cx3cr1 and Il10 mRNA expression by Tgfbr1fl/fl-derived (CD45.2+) CD11b+CD64+Ly6C–MHCII+ (P3+P4) colonic macrophages from the colon of WT:Cre– or WT:Cre+ mixed BM chimeric mice. Data are from one experiment with five biological replicates. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,****P<0.0001 as determined by Student’s t-test. (b) Expression of IL10 (left panel) or TNFα (right panel) by Tgfbr1fl/fl-derived (CD45.2+) P3/4 colonic macrophages from the colon of WT:Cre– or WT:Cre+ mixed BM chimeric mice assessed by intracellular cytokine staining following 4.5 hr culture in the presence (+ LPS) or absence (–) of LPS. Symbols represent individual animals and the horizontal lines are the means of 6 mice per group and are pooled from 2 independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 as determined by Student’s t-test. (c) Total mRNA transcripts (upper panel) and mRNA transcripts that show a greater than twofold change in expression between P1 and P4 in the colon (lower panel; see also Supplemental Table 1) that show at least twofold difference between Il10ra+/+ and Il10ra–/– colonic macrophages (IL10R-dependent -28) or between Tgfbr1+/+ and Tgfbr1–/– colonic macrophages (TGFβR1-dependent) (Student’s t test; P ≤ 0.05; fold change ≥ 2.0). Genes named in the overlapping regions are impacted by both IL10R and TGFβR1 deficiency.

These results indicate that although TGFβR and IL10R mediated signalling can both influence the behaviour of resident intestinal mϕ in vivo, their effects appear to be quite distinct. To study this in more detail, we compared the global transcriptome of TGFβR-deficient mϕ with that of a recently published transcriptome from IL10R-deficient mϕ 28. When compared with their control populations, 316 and 325 genes were expressed at significantly different levels by IL10R- and TGFβR1-deficient mϕ respectively. However only 9 of these were affected by both IL10R- and TGFβR1-deficiency, and this was reduced to 5 genes when we focused on the 1004 genes defining the transition from monocytes to resident mϕ in the colon (Figure 5c).

Thus, IL10 and TGFβ act in concert to imprint largely non-overlapping phenotypic and functional characteristics of mature mϕ in the colonic mucosa.

Discussion

Tissue mϕ are highly heterogeneous and their differentiation is determined by tissue-specific combinations of individual cytokines, transcription and growth factors 7,15,22,23,26. Here we show that mature mϕ in steady state colon progressively acquire a specific signature as they differentiate locally from classical Ly6Chi monocytes via a process that is determined to a substantial degree by intrinsic TGFβ mediated signalling.

By identifying a module of genes that is expressed by colonic mϕ but not by mature mϕ from other tissues, we extend previous findings that intestinal mϕ possess a distinctive transcriptional and epigenetic landscape 15. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to perform transcriptional profiling of monocyte-macrophage differentiation in the gut. By doing so, we demonstrate progressive imprinting by the colonic environment, as each stage within the local differentiation continuum became increasingly distinct from the equivalent subsets in dermis that share a classical monocyte precursor 9,10. This process must begin rapidly after recruitment of monocytes into the tissue, as newly arrived monocytes in the colon (‘P1’) were already transcriptionally distinct from their counterparts in both blood and dermis. This is consistent with our earlier findings that adoptively transferred Ly6Chi monocytes enter the colonic mucosa and change in phenotype within 24 hours after transfer 8. The mechanisms involved in this early acquisition of tissue specificity are unknown. However the process of crossing the endothelial barrier can itself induce phenotypic and genetic changes in monocytes 33 and the consequences of this may vary depending on the anatomical site. Other sources of such factors could be stromal cells in the vicinity of blood vessels and it would be important to explore the tissue-specificity of such processes in future. Alternatively, we cannot rule out the possibility that the BM monocyte compartment may be heterogeneous, with individual subsets already imprinted to migrate to specific tissues, but to date, this possibility has not been explored directly.

Important clues to the potential homeostatic roles of intestinal mϕ emerged from our comparative analysis of colonic and dermal mϕ development. In particular, genes encoding receptors for apoptotic cells showed progressive upregulation as monocytes matured and while some of these were common to both sites (e.g. C1q, Mer and CD36), others (e.g. αvβ5 integrin and Axl) were selectively enriched during colonic mϕ development. αvβ5 integrin plays an indispensable role in removing effete photoreceptor cells from the retina 34 and mice with LysM-driven deletion of integrin αv develop spontaneous colitis associated with accumulation of apoptotic cells 35. As β5 is the only partner for the αv chain expressed by intestinal mϕ (data not shown), these results suggest that αvβ5 may also be important for maintenance of intestinal homeostasis by myeloid cells 36. Together, these findings indicate how this population has been shaped to deal with the specific requirements of its environment. The rapid turnover rate of the intestinal epithelium means that effective clearance of effete cells and remodelling of the underlying extracellular matrix is essential. Colonic mϕ are perfectly equipped to handle these tasks, being located close to the surface epithelium and possessing all the machinery needed to clear apoptotic epithelial cells and modify the surrounding stroma. Intriguingly, fully differentiated colonic mϕ also expressed Amica1, the gene encoding junctional adhesion molecule-like (JAML), a protein that allows leukocytes to adhere to and migrate across tight junctions by binding to the Coxsackie and Adenovirus receptor (CAR) expressed by epithelial and endothelial cells 37. Our analysis showed that Amica1 is not expressed to any extent by other mϕ and given that intestinal CX3CR1+ mononuclear phagocytes have been suggested to extend processes into the epithelium to sample the lumen 38,39, the ability to form tight junctions may allow intestinal mϕ to enter the epithelial layer without disruption of the barrier. Importantly, all these activities take place without provoking local inflammation, perhaps reflecting the upregulation of several immunoregulatory mediators and receptors by mature colon mϕ including Il10, Il1r2, Il22ra2, Il18bp and Cd274 40–43, together with progressive downregulation of the pro-inflammatory signalling elements Myd88, Nod2 and Il6.

Recent studies indicated that Tgfbr1 is amongst those genes whose enhancer carries active epigenetic marks in intestinal mϕ 15 and consistent with this, we identified TGFβR mediated signalling as a candidate for controlling colonic mϕ differentiation. To test this idea, we examined CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/flRag1–/– mice, in which mature intestinal mϕ showed CD11c-driven Cre recombinase activity. All stages of the monocyte waterfall were present in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/flRag1–/– mice, suggesting that TGFβ does not control the recruitment of monocytes or survival of their progeny in the mucosa. However, our transcriptomic analysis identified a role for TGFβ in the maturation of colonic mϕ. Of the genes that define P1 to P4 transition, ~10% were altered in the absence of Tgfbr1, including Cx3cr1, whose high expression is a defining feature of terminally differentiated colonic mϕ 8,18,44. We cannot exclude the possibility that the transcriptome of mϕ from the Tgfbr1fl/fl strains may be influenced by the fact they are bred on a Rag1–/– background and hence may be intrinsically distinct from those obtained from the immunocompetent mice that we used to establish the macrophage “signature”. However the fatal multi-organ inflammation that occurs due to Cre recombinase activity in a small subset of T cells in CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/fl mice{Bain, Montgomery et al, Unpublished observations} precluded use of these mice for studies of mϕ function. It was also impossible to target the Tgfbr1 deficiency to mϕ more specifically using, for example, the conditional Cx3cr1-Cre approach, as CX3CR1 itself is downregulated due to Tgfbr1 deficiency. However it is important to note that our studies of Tgfbr1 deficient mϕ used Cre– littermates on the Rag1–/– background as internal controls, allowing us to identify the TGFβ dependent effects precisely. Many of the genes in this TGFβ-dependent cassette included those that were upregulated during monocyte maturation in colon, but not in the dermis, consistent with tissue specific imprinting. However, part of this cassette was shared with microglia in the brain, which are known to rely on TGFβ for their differentiation 26. Given that microglia are entirely yolk sac-derived, whereas colonic mϕ are derived from classical monocytes, our findings corroborate recent conclusions that anatomical location, and not developmental origin, is the major determinant of resident mϕ function 16.

In addition to these changes in mature mϕ, the monocyte waterfall was also disrupted in the absence of Tgfbr1, with more P1 and P2 monocytes, and fewer P3+4 cells in all three models we investigated. Importantly, these changes were not secondary to local inflammation, as this was not present in any of the models. Although the BM chimera approaches confirmed that the effects of deleting TGFβR1 were intrinsic to CD11c+ mϕ, the infiltrating monocytes, which are CD11c– and express low levels of Tgfbr1, were derived from both Tgfbr1fl/fl and wild type sources in the mixed chimeras. Therefore, this phenomenon appears to be a bystander consequence of the lack of TGFβ dependent control of mϕ function. The exact basis of this effect remains to be determined, but it was associated with enhanced expression of mRNA for the monocyte chemoattractant CCL8 by colonic mϕ. In parallel, the cell intrinsic deficiency of TGFβR1 in mϕ was accompanied by an expanded number of CD169+ mϕ, a population that has recently been shown to be involved in monocyte recruitment via production of CCL8 25. Thus TGFβR1 signalling may control how colonic mϕ regulate the rate of monocyte recruitment to the mucosa.

We initially hypothesised that the dysregulated monocyte-mϕ waterfall occurred because Tgfbr1–/– colonic mϕ had become unusually responsive to local pro-inflammatory stimuli. However these cells actually produced less TNFα than littermate controls both after stimulation and under resting conditions. Although these findings contrast with previous experiments showing that exogenous TGFβ can inhibit pro-inflammatory responses by human blood monocytes 19,32, such in vitro conditions may not recapitulate the in vivo environment. In our hands, steady state and LPS-stimulated Cre+ mϕ also produced less IL10 than control mϕ, although this was associated with only a rather limited disruption of the monocyte-mϕ continuum in vivo, consistent with recent results that signalling through the IL10R in mϕ is much more important for preventing inflammation than their ability to produce IL10 itself 28,29,31. Our microarray comparison of Tgfbr1–/– and Il10ra–/– colonic mϕ provided further evidence that these cytokines regulate mϕ activity by different mechanisms, as there was little or no overlap in the genes whose expression was altered in these animals. As above, it should be noted that these experiments compared gene expression changes in IL10R deficient mϕ from immunocompetent mice with those in Tgfbr1 deficient mϕ from mice on the Rag1–/– background. Therefore we cannot exclude the possibility that the transcriptional differences might vary if the strains were maintained on similar backgrounds. Together our results indicate that TGFβ and IL10 play complementary roles in imprinting intestinal mϕ, with TGFβ shaping their tissue repair and scavenging functions, whereas IL10 controls the production of pro-inflammatory mediators. That IL10 and TGFβ may have distinct effects on controlling intestinal inflammation in vivo are consistent with experiments in which TGFβ inhibited γIFN production in intestinal explants by limiting IL12 production, whereas IL10 did this by reducing caspase-1 mediated generation of IL18 45.

Our discovery of TGFβ as being critical for the functional specification of intestinal mϕ adds to the growing list of factors that drive the differentiation of mϕ in a tissue-specific manner 7,22,23,46–48. However TGFβ alone clearly cannot explain all aspects of intestinal mϕ differentiation, consistent with the evidence from other tissues that multiple factors, including specific cytokines and transcription factors act synergistically to imprint the full phenotypic and functional signature of resident mϕ 49. Interestingly, the transcription factor RUNX3 was highlighted in a recent study of the transcriptome and epigenome of intestinal mϕ 15. RUNX3 mediates TGFβ responsiveness in several cell types and TGFβR signalling cooperates with PU.1 in RUNX3 driven development of Langerhans cells 50–52. Other mediators that can influence intestinal mϕ development include CSF1 53 and Notch 54 and interestingly, we found that TGFβR signalling regulated the expression of genes involved in the Notch signaling pathway, including Hes1 and Dtx4. The retinoic acid and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signalling pathways also both have abundant ligands in the intestine and RA is known to regulate intestinal DC development 55, while the Ahr-inducible regulatory gene Ahrr is part of the colonic mϕ signature we identified. Furthermore, microbes and their products are known to influence the behaviour 56 and turnover of colonic mϕ 9. Dissecting the interaction of different pathways in regulating intestinal macrophage development and the factors involved is an important goal for the future.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Wild-type (WT) C57Bl/6 (CD45.2+), C57Bl/6.SJL (CD45.1+), CD45.1+/CD45.2+, Cx3cr1GFP/+ 57, CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl mice have been described previously 58 and were generated by crossing Itgax-Cre mice 59 with mice carrying LoxP sites at exon 3 of the Tgfbr1 gene 60 and maintained on a Rag1–/– background. Ccr2–/– 61 were backcrossed onto the C57Bl/6.SJL (CD45.1+) background. CD11c-Cre.Rosa26-LSL-eYFP mice were generated by crossing Itgax-Cre mice with homozygous Rosa26-LSL-YFP mice (a gift from Dr. Megan Macleod, University of Glasgow). All mice had been backcrossed for at least nine generations onto the B6 background and were used at 6 – 12 weeks of age. Age-matched mice were used in all experiments for all groups. Male and female mice were used throughout the study and all mice were bred and maintained at the Central Research Facility at the University of Glasgow under specified pathogen-free conditions under licence by the UK Home Office and approved by the University of Glasgow Local Ethical Review Panel.

Cell Isolation

Intestinal lamina propria leukocytes were isolated as described previously 62 (Cerovic, 2013). Briefly, colons and small intestines were removed, Peyer’s patches were excised from small intestines, the tissues were cleared of luminal contents and opened longitudinally. Tissue was incubated at 37°C shaking twice for 15min in HBSS (2mM EDTA) to remove the epithelial layer and then digested in complete RPMI 1640 (cRPMI) (RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS, 2mM L-glutamine, 100U/ml penicillin, 100μg/ml streptomycin and 50μM 2-mercaptoethanol; all Gibco) containing 0.425mg/ml collagenase V (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.625mg/mL collagenase D (Roche), 1mg/ml dispase (Gibco), 30μg/ml DNase (Roche) for the colon or 1 mg/mL Collagenase VIII (Sigma-Aldrich) for the small intestine for 40min shaking at 37°C. Dermal leukocytes were isolated as described previously 63.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Following incubation with purified anti-CD16/CD32 for 10 mins at 4°C, 1–10x106 cells were stained at 4°C in the dark using the antibodies listed in Supplementary Table 5 and analyzed using an LSR II or FACSAriaI/III cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star). 7AAD or Fixable Viability Dye eFluor510 or eFluor780 was used to eliminate dead cells from analysis. For microarray analysis of colonic P1-P4 subsets, cells were sorted according to 8. For microarray analysis of colonic mϕ from CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr1fl/fl mice, cells were sorted using the gating strategy detailed in Supplementary Figure 3b.

Cell Stimulation and Cytokine Measurement In Vitro

For intracellular cytokine detection, whole colonic lamina propria isolates were incubated in cRPMI with monensin (Biolegend; 1:1000) and brefeldin A (Biolegend; 1:1000) with or without LPS (1μg/ml) for 4.5hrs in sterile capped polystyrene tubes at 37°C in 5% CO2. Intracellular staining for IL10 and TNFα was performed following surface staining and fixation and permeabilisation using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit.

Generation of BM chimeras

6- to 8-week-old CD45.1+CD45.2+ WT mice were lethally irradiated with two doses of 5Gy with an interval of 1hr and reconstituted immediately by intravenous infusion of 5×106 BM cells from CD45.1+ WT mice together with BM from CD45.2+ CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl Rag1–/– (Cre+) or Tgfbr1fl/fl mice (Cre–) mice at a ratio of 1:1. In some experiments, recipients were reconstituted with BM from Ccr2–/– (CD45.1+) mice and CD45.2+ CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl mice Rag1–/– (Cre+) or Tgfbr1fl/fl mice (Cre–) mice at a ratio of 1:1. Mice were left for at least 8 weeks before analysis.

Quantitation of gene expression by real-time reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted from FACS-purified colonic subsets of individual adult mice or BM chimeric mice using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Superscript II First strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and gene expression was assayed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR using Brilliant III Ultra Fast SYBR qPCR master mix (Agilent Technologies, Workingham, UK) on the 7500HT Fast system (Applied Biosystems, Paisley, UK). Primers) using the primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Glasgow, UK) are detailed in Supplementary Table 6. Complementary DNA samples were assayed in triplicate and gene expression levels were normalized to Cyclophilin A. The mean relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-dC(t) method.

Histological Analysis

Sections of colon were fixed in 2% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and stained with H & E (Sigma) for assessment of intestinal architecture.

Microarray analysis

Microarray analysis was performed in triplicate. Cell populations from colonic cell isolates were sort-purified and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen).

The microarray study of mϕ populations from CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl mice Rag1–/– mice was performed in the Research Core Unit Transcriptomics of the Hannover Medical School using a refined version of the Whole Mouse Genome Oligo Microarray 444 K v2 (Design ID 026655, Agilent Technologies) (026655AsQuadruplicatesOn180k’ Design ID 048306) and designed via Agilent’s eArray portal using a 4180 k design format for mRNA expression as template. All non-control probes of design ID 026655 were printed four times onto a single 180 k Microarray. Control probes required for proper Feature Extraction software algorithms were determined and placed automatically by eArray using recommended default settings. Total RNA (4–8 ng) was used to prepare aminoallyl-UTP-modified (aaUTP) cRNA (Amino Allyl MessageAmp II Kit; #AM1753; Life Technologies) as directed by the company (applying one round of amplification). The labelling of aaUTP-cRNA was performed by use of Alexa Fluor 555 Reactive Dye (#A32756; LifeTechnologies). Before the reverse transcription reaction, 1ml of a 1:50,000 dilution of Agilent’s ‘One-Colour spike-in Kit stock solution’ (#5188–5282, Agilent Technologies) was added to each total RNA sample. cRNA fragmentation, hybridization and washing steps were carried out as recommended in the ‘One-Colour Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis Protocol V5.7’, except that 45 ng of each fluorescently labelled cRNA population were used for hybridization. Slides were scanned on the Agilent Micro Array Scanner G2565CA (pixel resolution 3mm, bit depth 20). Data extraction was performed with the ‘Feature Extraction Software V10.7.3.1’ using the extraction protocol file ‘GE1_107_Sep09.xml’. Extracted raw data were imported into Omics software 3.2 (Qlucore) under default import settings for Agilent One-Colour mRNA Microarrays. Accordingly, data processing steps were: (1) removal of control measurements, (2) log base 2 transformation, (3) normalization of non-control values by shifting to 75 Percentile, (4) averaging of values from on-chip replicates and (5) baseline transformation to the median.

The microarray study of monocyte and macrophage populations from Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice was performed by use of GeneChip® Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix). Quantity, quality and absence of genomic DNA contamination were assessed with a Bioanalyser (Agilent). Biotinylated double strand cDNA targets were prepared, starting from 4.9 ng to 20 ng of total RNA using the NuGEN Ovation Pico WTA System V2 Kit and the NuGEN Encore Biotin Module Kit according to NuGEN recommendations. Following fragmentation and end-labeling, 2.07 μg of cDNAs were hybridized for 16 hours at 45°C on GeneChip® Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix) interrogating 28.853 genes represented by approximately 27 probes spread across the full length of the gene. The chips were washed and stained in the GeneChip® Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix) and scanned with the GeneChip® Scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix) at a resolution of 0.7 μm. Raw data (CEL Intensity files) were extracted from the scanned images using the Affymetrix GeneChip® Command Console (AGCC) version 3.2. The CEL Intensity files were further processed using the Omics software 3.2 (Qlucore). They were imported using the default import process for GeneChip® Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix) using RMA-Sketch Normalisation.

Omics software 3.2 (Qlucore) was used to generate heat maps and to classify cell subsets according to the proximity of their gene expression pattern as assessed by hierarchical clustering with average linkage. Lists of genes showing differential expression between two different conditions were generated and the expression levels in the heatmaps are represented as log2 transformations.

Enrichment analyses was performed using WebGestalt 64 all the genes present on the GeneChip® Mouse Gene 1.0 ST array were used as a reference (N genes in the reference gene set B). Genes within this set that changed by at least 2-fold with a p-value lower than 0.05 during the differentiation from P1 to P4 in the colon were defined as the gene set of interest (n genes in the interesting gene set A). k genes in A and K genes in B are given in a specific category C. The hypergeometric test to evaluate the significance of enrichment for category C in gene set A is: . As multiple categories in a group of functional gene set categories were being compared, the p-value was adjusted using R function p.adjust based on Benjamini Hochberg.

The microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus and will be made available upon publication. Public expression data from the ImmGen compendium (Heng and Painter, 2008) of mouse tissue macrophage subsets were retrieved from the GEO dataset GSE15907. The expression data from the dermal tissue were retrieved from the GEO dataset GSEGSE49358.

Accession Numbers

The microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds) under accession numbers GSE84764 (Colonic P1 to P4 array data) and GSE84765 (Colonic TGFβR array data).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software. All data are presented as mean ± s.d. and P=0.05 are considered as significant. Statistical tests used and levels of significance are detailed in each figure legend. Statistical analysis of microarray data was performed using Omics software 3.2 (Qlucore). Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups, while multiple groups were compared using ANOVA or Student’s t tests with appropriate corrections as detailed in the legends. A P value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Ruairi Lynch and Cathy Hawley for critical reading of the manuscript, Ms Diane Vaughan at the Glasgow Flow Cytometry Facility for help with sorting, Dr Moritz Muschaweck for his assistance with histological analysis. Microarray data of colonic macrophages from CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1fl/fl mice were generated by the Research Core Unit Transcriptomics of the Hannover Medical School.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust UK, the Medical Research Council UK, Tenovus Scotland, the German Research Foundation grant DFG PA921/2-1 (O.P.), European Research Council FP7/2007–2013 grants n° 322465 (B.M.) and 281225 (M.D.) ANR grant SkinDC (S.H.), the Hannover Biomedical Research School (HBRS) and the Center for Infection Biology (ZIB).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AS, CCB, JoMa and JeMo performed experiments and analysed data. AS, EP, BD, MD and SH carried out and interpreted the transcriptional analyses. SJJ provided expert advice. AMM, OP, BM, SWM and SH supervised different parts of the project. CCB and AMM conceived and directed the study. AS, CCB, OP and AMM wrote the manuscript and all authors edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Perdiguero EG, Geissmann F. The development and maintenance of resident macrophages. Nature immunology. 2015;17:2–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue biology perspective on macrophages. Nature immunology. 2016;17:9–17. doi: 10.1038/ni.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-Resident Macrophage Ontogeny and Homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;44:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez Perdiguero E, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature. 2015;518:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoeffel G, et al. C-Myb(+) erythro-myeloid progenitor-derived fetal monocytes give rise to adult tissue-resident macrophages. Immunity. 2015;42:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheng J, Ruedl C, Karjalainen K. Most Tissue-Resident Macrophages Except Microglia Are Derived from Fetal Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Immunity. 2015;43:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guilliams M, et al. Alveolar macrophages develop from fetal monocytes that differentiate into long-lived cells in the first week of life via GM-CSF. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:1977–1992. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bain CC, et al. Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:498–510. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bain CC, et al. Constant replenishment from circulating monocytes maintains the macrophage pool in the intestine of adult mice. Nature immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ni.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamoutounour S, et al. Origins and functional specialization of macrophages and of conventional and monocyte-derived dendritic cells in mouse skin. Immunity. 2013;39:925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epelman S, et al. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molawi K, et al. Progressive replacement of embryo-derived cardiac macrophages with age. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211:2151–2158. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidt T, et al. Differential contribution of monocytes to heart macrophages in steady-state and after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2014;115:284–295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bain CC, et al. Long-lived self-renewing bone marrow-derived macrophages displace embryo-derived cells to inhabit adult serous cavities. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11852. ncomms11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavin Y, et al. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell. 2014;159:1312–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Laar L, et al. Yolk Sac Macrophages, Fetal Liver, and Adult Monocytes Can Colonize an Empty Niche and Develop into Functional Tissue-Resident Macrophages. Immunity. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SH, Starkey PM, Gordon S. Quantitative analysis of total macrophage content in adult mouse tissues. Immunochemical studies with monoclonal antibody F4/80. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1985;161:475–489. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamoutounour S, et al. CD64 distinguishes macrophages from dendritic cells in the gut and reveals the Th1-inducing role of mesenteric lymph node macrophages during colitis. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:3150–3166. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smythies LE, et al. Inflammation anergy in human intestinal macrophages is due to Smad-induced IkappaBalpha expression and NF-kappaB inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19593–19604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platt AM, Bain CC, Bordon Y, Sester DP, Mowat AM. An independent subset of TLR expressing CCR2-dependent macrophages promotes colonic inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:6843–6854. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zigmond E, et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue-specific signals control reversible program of localization and functional polarization of macrophages. Cell. 2014;157:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider C, et al. Induction of the nuclear receptor PPAR-γ by the cytokine GM-CSF is critical for the differentiation of fetal monocytes into alveolar macrophages. Nature immunology. 2014;15:1026–1037. doi: 10.1038/ni.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gautier EL, et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nature immunology. 2012;13:1118–1128. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asano K, et al. Intestinal CD169(+) macrophages initiate mucosal inflammation by secreting CCL8 that recruits inflammatory monocytes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7802. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butovsky O, et al. Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:131–143. doi: 10.1038/nn.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivollier A, He J, Kole A, Valatas V, Kelsall BL. Inflammation switches the differentiation program of Ly6Chi monocytes from antiinflammatory macrophages to inflammatory dendritic cells in the colon. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:139–155. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zigmond E, et al. Macrophage-restricted interleukin-10 receptor deficiency, but not IL-10 deficiency, causes severe spontaneous colitis. Immunity. 2014;40:720–733. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shouval DS, et al. Interleukin-10 receptor signaling in innate immune cells regulates mucosal immune tolerance and anti-inflammatory macrophage function. Immunity. 2014;40:706–719. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoshi N, et al. MyD88 signalling in colonic mononuclear phagocytes drives colitis in IL-10-deficient mice. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1120. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girard-Madoux MJH, et al. IL-10 control of CD11c+ myeloid cells is essential to maintain immune homeostasis in the small and large intestine. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maheshwari A, et al. TGF-beta2 suppresses macrophage cytokine production and mucosal inflammatory responses in the developing intestine. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:242–253. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jakubzick C, et al. Minimal differentiation of classical monocytes as they survey steady-state tissues and transport antigen to lymph nodes. Immunity. 2013;39:599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruggiero L, Connor MP, Chen J, Langen R, Finnemann SC. Diurnal, localized exposure of phosphatidylserine by rod outer segment tips in wild-type but not Itgb5-/- or Mfge8-/- mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8145–8148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121101109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lacy-Hulbert A, et al. Ulcerative colitis and autoimmunity induced by loss of myeloid alphav integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15823–15828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer T, et al. Identification of Axl as a downstream effector of TGF-β1 during Langerhans cell differentiation and epidermal homeostasis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:2033–2047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morton PE, et al. TNFα promotes CAR-dependent migration of leukocytes across epithelial monolayers. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26321. doi: 10.1038/srep26321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niess JH, et al. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science (New York, NY. 2005;307:254–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1102901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chieppa M, Rescigno M, Huang AY, Germain RN. Dynamic imaging of dendritic cell extension into the small bowel lumen in response to epithelial cell TLR engagement. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:2841–2852. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garlanda C, Riva F, Bonavita E, Mantovani A. Negative regulatory receptors of the IL-1 family. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huber S, et al. IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature. 2012;491:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature11535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dinarello CA, Novick D, Kim S, Kaplanski G. Interleukin-18 and IL-18 binding protein. Front Immunol. 2013;4:289. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang J, et al. The novel costimulatory programmed death ligand 1/B7.1 pathway is functional in inhibiting alloimmune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2011;187:1113–1119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varol C, et al. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31:502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jarry A, Bossard C, Sarrabayrouse G, Mosnier J-F, Laboisse CL. Loss of interleukin-10 or transforming growth factor β signaling in the human colon initiates a T-helper 1 response via distinct pathways. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1887–96.e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosas M, et al. The transcription factor Gata6 links tissue macrophage phenotype and proliferative renewal. Science (New York, NY. 2014;344:645–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1251414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gautier EL, et al. Gata6 regulates aspartoacylase expression in resident peritoneal macrophages and controls their survival. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1084/jem.20140570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.A-Gonzalez N, et al. The nuclear receptor LXRα controls the functional specialization of splenic macrophages. Nature immunology. 2013;14:831–839. doi: 10.1038/ni.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lavin Y, Mortha A, Rahman A, Merad M. Regulation of macrophage development and function in peripheral tissues. Nature reviews. 2015;15:731–744. doi: 10.1038/nri3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fainaru O, et al. Runx3 regulates mouse TGF-beta-mediated dendritic cell function and its absence results in airway inflammation. EMBO J. 2004;23:969–979. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brenner O, et al. Loss of Runx3 function in leukocytes is associated with spontaneously developed colitis and gastric mucosal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16016–16021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407180101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chopin M, et al. Langerhans cells are generated by two distinct PU.1-dependent transcriptional networks. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:2967–2980. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlitzer A, et al. IRF4 transcription factor-dependent CD11b+ dendritic cells in human and mouse control mucosal IL-17 cytokine responses. Immunity. 2013;38:970–983. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishifune C, et al. Differentiation of CD11c+ CX3CR1+ cells in the small intestine requires Notch signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5986–5991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401671111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klebanoff CA, et al. Retinoic acid controls the homeostasis of pre-cDC-derived splenic and intestinal dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:1961–1976. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ueda Y, et al. Commensal microbiota induce LPS hyporesponsiveness in colonic macrophages via the production of IL-10. Int Immunol. 2010;22:953–962. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jung S, et al. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kel JM, Girard-Madoux MJH, Reizis B, Clausen BE. TGF-beta is required to maintain the pool of immature Langerhans cells in the epidermis. J Immunol. 2010;185:3248–3255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caton ML, Smith-Raska MR, Reizis B. Notch-RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8- dendritic cells in the spleen. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1653–1664. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Larsson J, et al. Abnormal angiogenesis but intact hematopoietic potential in TGF-beta type I receptor-deficient mice. EMBO J. 2001;20:1663–1673. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boring L, et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bain CC, Mowat AM. CD200 receptor and macrophage function in the intestine. Immunobiology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Henri S, et al. CD207+ CD103+ dermal dendritic cells cross-present keratinocyte-derived antigens irrespective of the presence of Langerhans cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:189–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang J, Duncan D, Shi Z, Zhang B. WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt): update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W77–83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.