Abstract

The biannual European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) conference on nuclear receptors was organized by Beatrice Desvergne and Laszlo Nagy and took place in Cavtat near Dubrovnik on the Adriatic coast of Croatia September 25–29, 2009. The meeting brought together researchers from all over the world covering a wide spectrum from fundamental mechanistic studies to metabolism, clinical studies, and drug development. In this report, we summarize the recent and exciting findings presented by the speakers at the meeting.

Highlights of the EMBO nuclear receptor meeting in Cavtat, Croatia, September 2009, are summarized in this meeting report.

Nuclear receptors (NRs) constitute a unique group of transcription factors. They act as sensors for metabolic as well as systemic hormonal signals and regulate a wealth of cellular processes from growth and differentiation to metabolism. Moreover, the fact that their activity can be pharmacologically modulated by specific ligands, thereby allowing for agonism, partial agonism, and antagonism, has made them primary therapeutic targets for decades. In addition, the ligand-dependence of most of their functions has also allowed using NRs as tools to generate paradigms for the molecular mechanisms of transcriptional regulation.

Novel progress in protein structure research has revolutionized the view on how dimerized NRs bind their DNA response elements and how variations in DNA binding elements impact on NR structure and activity. Genome-wide approaches, such as mapping of chromatin accessibility (by e.g. DNAse hypersensitivity) and mapping of epigenetic marks and transcription factor and cofactor binding by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) combined with deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) has provided a hitherto unprecedented amount of information and has opened the door to an entirely new view on transcriptional regulation by NRs. Conditional knockout or knock-in mouse models in various disease models provide valuable insight into pathophysiological mechanisms in which NRs play a role. Likewise, detailed molecular analyses of the interactions of NR with coregulators and the chromatin remodeling machinery continue to enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of action and of the complexity of the system. The combination of all these technologies will undoubtedly lead to novel therapeutic strategies targeting NRs and their associated factors.

The recent EMBO NR conference organized by Beatrice Desvergne and Laszlo Nagy (Fig. 3) brought together leading experts from the different areas of the NR field. The novel findings presented at the meeting are summarized below.

Fig. 3.

The main organizers of the meeting: Laszlo Nagy and Beatrice Desvergne.

Genome-Wide Approaches

Several speakers reported on studies uncovering genome-wide aspects of transcriptional regulation by NRs and associated factors. Peter Fraser gave the keynote lecture about his recent elegant studies combining fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technology and chromatin conformation capture on chip (4C) to investigate higher order chromatin structures. Using FISH his group has mapped 200–400 so-called transcription factories (i.e. nuclear foci where active genes coassociate in a compartment with high levels of active transcription) in mouse erythroid cells. Mitchell and Fraser ( 1) have previously shown that RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) is rather stably associated with these factories, indicating that it may be tethered to a scaffold, whereas the transcription factors dissociate more rapidly. Notably, they have shown that initiation but not elongation is required to maintain active genes in these factories. Using a genome-wide enhanced 4C (e4C) approach with biotin-labeled α- and β-globin primers, Fraser showed that genes regulated by Krueppel-like factor 1 (Klf-1) preferentially cluster in shared factories and that Klf-1 is required for the nuclear organization of Klf-1-dependent genes in transcription factories ( 2). It was also reported that a particular gene locus associates with different subsets of preferred partner loci depending on the cell type. These data indicate that the composition of transcription factors assembled at a given locus is an important determinant of which specialized factory a locus is located to. Gordon Hager was among the pioneers in exploiting techniques to measure dynamics of NR transcriptional activity. Hager and colleagues ( 3) now demonstrated that the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) occupancy on DNA seems to follow the ultracircadian rhythm of cortisol secretion. Using their established MMTV tandem array cell line in combination with fluorescence recovery after photo bleaching techniques they showed that when cortisol is administered in pulses, the GR exchange from glucocorticoid response elements is rapid after agonist removal. Subsequently, the receptor is rapidly recycled by chaperones to be available for agonist binding again. The pulsatile behavior of GR binding and promoter occupancy was also translated into a pulsatile mRNA synthesis of target genes—in tissue culture experiments and in adrenalectomized rats receiving corticosterone every hour. These data may explain the observation that GR responsive genes under physiological conditions are quite differently regulated compared with the regulation under pharmacological conditions as they occur in steroid therapy. Future challenges will be to reveal the complex gene regulations by pulsating endogenous glucocorticoids in vivo under normal and stress conditions.

ChIP-seq is currently the method of choice for assessing the genome-wide binding of DNA-associated factors and epigenetic modifications. Henk Stunnenberg reported on ChIP-seq studies to map the genome-wide binding of the promyelocytic leukemia-retinoic acid receptor α (PML-RARα) fusion protein, which results from the t(15;17)(q22;q21) translocation that is present in the majority of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Expression of this onco-fusion protein results in a blockade of hematopoietic differentiation at the promyelocyte stage, which can be overcome by treating these cells with pharmacological concentrations of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), the endogenous ligand of the RAR protein. Using the classical leukemic cell line NB4, Stunnenberg and co-workers ( 4) detected colocalization of PML-RARα and retinoid X receptor (RXR) in proliferating NB4 cells, whereas ATRA treatment resulted in loss of PML-RARα and RXR binding. In addition, genome-wide ChIP-Seq data on histone 3 (H3) acetylation (an activating mark), H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and DNA methylation (both repressive marks) were included. ATRA treatment induced histone 3 (H3) acetylation preferably at PML-RAR:RXR binding sites both in the NB4 cell line as well as in primary cells of an APL patient. In contrast, H3K27me3 modifications were most evident at sites not bound by PML-RAR:RXR. Interestingly, also DNA methylation at PML-RAR:RXR binding sites was not changed upon ATRA treatment. Collectively, their results indicate that ATRA-induced PML-RARα degradation is accompanied by H3 acetylation and suggest a crucial role for PML-RARα-recruited histone deacetylase activity in transformation of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Christopher Glass and colleagues ( 5) showed in previous work that liver X receptors (LXRs) are important antiinflammatory factors in macrophages. Agonist-activated LXR suppresses proinflammatory gene expression presumably via tethering mechanisms with other myeloid or proinflammatory transcription factors. To identify the binding sites of LXR and interacting factors, the laboratory of Christopher Glass modified the ChIP-seq method by in vivo biotinylation of a BirA substrate-TEV (tobacco etch virus protease) cleavage site-LXRα fusion protein in primary macrophages in the presence of the biotin ligase BirA. Cross-linked chromatin was then purified on a streptavidin column and eluted using the TEV protease followed by deep sequencing of the DNA. Interestingly, besides the DR4 motif, binding motifs of Pu.1, CAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) and c-Fos were overrepresented in the sequenced DNA, indicating that LXR interacts with transcription factors that are important for specifying the myeloid and B cell lineages. Glass and co-workers ( 5) performed a row of elegant experiments isolating biotinylated LXRα combined with immunoprecipitations against these transcription factors and methylated histones (e.g. H3K4me1) in macrophages and B cells. Pu.1 specifically interacts with LXR in the macrophage lineage. By contrast, in B cells Pu.1 interacts with the early B-cell factor (EBF). Thus, a signature for Pu.1 and interacting factors specific for macrophage and B-cell differentiation, respectively, could be established. These findings shed new light on the transcription factor network involved in lineage specification of immune cells and enhance the molecular understanding of the antiinflammatory activity of LXR ligands. Susanne Mandrup talked about LXR and RXR ChIP-seq studies in mouse liver. Recently the group of Bart Staels ( 6) showed in collaboration with her laboratory that the hypertriglyceridemic action of the RXR agonist bexarotene in mouse liver is entirely dependent on LXR. Interestingly, bexarotene selectively activates LXR target genes involved in triglyceride synthesis rather than cholesterogenic LXR target genes. She now reported the genome-wide mapping of LXR and RXR binding sites in mouse liver in response to RXR and LXR agonists, respectively. Bexarotene promotes the recruitment of RXR and to a much lesser extent LXR to their respective binding sites, whereas LXR agonists promote binding of both RXR and LXR to their target sites. Interestingly, RXR binding to most LXR:RXR binding sites is maintained in LXRα/β knockout mice, indicating that RXR binds to those sites as heterodimers with other NRs in the absence of LXR. Chin-Yo Lin and the laboratory of Edison Liu ( 7) have previously reported that the acute myeloid leukemia 1 protein (AML-1/RUNX1) is a pivotal factor for transrepression of estrogen receptor α (ERα) based on ERα genome-wide binding studies by ChIP paired-end di-tag cloning in MCF-7 cells. Binding sites for RUNX1/AML-1 were detected highly overrepresented at ERα binding sites in repressed genes. Now Lin and co-workers demonstrated that RUNX1 is indeed essential for mediating transrepression of a subset of ERα target genes evidenced by ChIP and knock-down of RUNX1. To which extent the ERα/RUNX1 interaction is crucial for estrogen actions in breast cancer remains to be determined; however, it could serve as a novel target for therapeutic intervention.

Previous studies have revealed the dynamic, combinatorial, and cyclical recruitment of transcription factors and chromatin remodeling during ER-regulated transcription. Many estrogen-responsive genes are not randomly dispersed in the genome but rather included into clusters, and Raphaël Métivier discussed how ER regulates such gene clusters. Based on different genome-wide approaches (ChIP-on-chip, DNA-FISH, formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements) as well as approaches, such as chromatin conformation capture, focusing on the estrogen-responsive cluster of the Trefoil factor genes (locus 21q22.3), Metivier presented data indicating that the dynamic binding of ER to several intergenic regions has complex effects on local chromatin remodeling as well as on the dynamic spatial organization of the cluster. His team also evidenced that long-range chromosomal interactions occur during the estrogenic regulation of the Trefoil factor cluster and that insulator proteins such as CCCTC binding factor (CTCF) together with cohesins play an important role in the functionality of the cluster. Xiang-Dong Fu provided evidence that the transcription factor forkhead-box A1 (FoxA1) serves as an enhancer programmer in the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP by simultaneously guiding and restricting androgen receptor (AR) targeting in the human genome. He showed that AR is dramatically reprogrammed to target a large number of new sites in the genome as a result of FoxA1 down-regulation. Because FoxA1 down-regulation has been found to be associated with advanced prostate cancer, he concluded that this mechanism likely contributes to the progression of prostate cancer.

Nuclear Receptor Structures

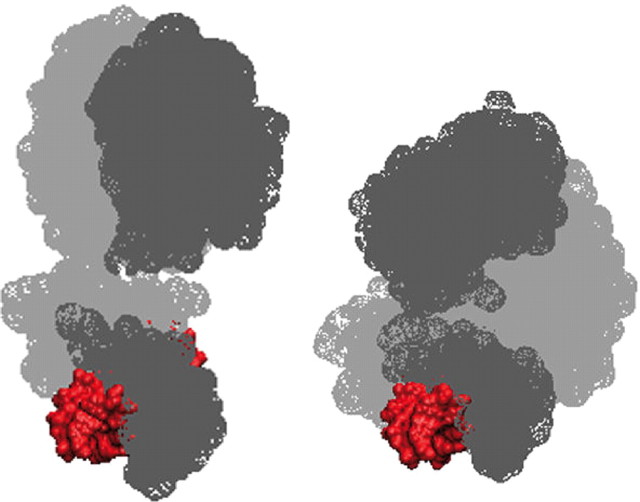

Three talks focused on the structural organization of full-length NRs bound to DNA response elements. Fraydoon Rastinejad ( 8) reported on the structure of the entire peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and RXRα heterodimer bound to a PPAR response element (PPRE), revealing the interconnection between the PPRE and protein domains at the level of the entire receptor. In particular, he showed how regions outside the DNA binding domain (DBD) can contribute to DNA recognition and affinity. For example, Rastinejad’s structures reveal that the hinge region linking the DBD and ligand binding domain (LBD) of PPARγ interacts with the DNA minor groove thus dictating heterodimer polarity. Another interesting observation was that the relative arrangement of receptor domains positions the PPARγ LBD so that it contacts both receptor DBDs to stabilize their PPRE binding. Natacha Rochel from D. Moras’s group and Bruno Klaholz reported on solution structures of several full-length NR heterodimers (RAR:RXR, PPAR:RXR, and vitamin D receptor:RXR) determined by small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) and high-resolution single particle cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM), respectively. Interestingly, it appears that solution structures exhibit a different spatial domain organization as compared with the crystal structure of PPARγ:RXRα (Fig. 1). A key feature of the solution structures shown is an arrangement of the LBDs approximately perpendicular to the DNA, without interdomain contacts as in the PPAR:RXR crystal structure. In addition to differences between solution and crystalline states, the context-dependence (diversity of response elements, ligands, or coregulators) could also have an influence on the architecture of NRs.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the structures of PPARγ:RXRα:PPRE as determined in solution by small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) (left) or by x-ray crystallography (PDB code 3DZY; right). Color code: PPAR in light gray, RXR in dark gray, and the PPRE in red. While the PPARγ:RXRα heterodimer adopts an extended conformation in solution, a more compact structure is observed in the crystal (Courtesy of N. Rochel and D. Moras).

Further data on the structural basis of NR regulation came from the work made in Keith Yamamoto’s laboratory. Sebastiaan H. Meijsing ( 9) reported on a new paradigm for NR action by providing the first structural interpretation of a concept in which the particular sequence of a DNA response element plays a role not only in the recruitment of specific transcription factors, but also in modulating their activity. Using structural, biochemical, and cell-based approaches, Meijsing and colleagues demonstrated how DNA can act as an allosteric effector to modulate GR activity.

On the coregulator side, details in the nature of the large multi-protein repression complex that is recruited to unliganded NRs by the NR corepressor (NCoR) and the silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT) was presented by John W. Schwabe. Although the components of NCoR and SMRT-containing complexes have been rather well characterized, the structural and functional roles of the individual components are poorly understood. Using structural and biophysical approaches, Schwabe reported on a model for the interaction of SMRT with transducin-like 1 (TBL1) and G-protein suppressor 2, which are known to be components of the core complex. Finally, V. Krishna Chatterjee described a novel human PPARγ LBD mutation (A233E) associated with lipodystrophic insulin resistance. The mutant receptor shows markedly attenuated responses to putative endogenous ligands [e.g. prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2)] compared with synthetic agonists (e.g. farglitazar), and circular dichroism studies showed that destabilization of LBD structure by the mutation could be reversed by farglitazar but not PGJ2. Molecular modeling indicated that alanine 233 is more involved in ligand interaction when the pocket is occupied by PGJ2 as opposed to synthetic agonists, with its replacement by a charged glutamic acid residue being deleterious. Overall, he suggested that the properties of this receptor mutation may provide insights into differential occupancy of the ligand binding cavity by endogenous vs. synthetic PPARγ agonists.

Posttranslational Modifications, Cofactors, and Epigenetic Regulation

One session was devoted to regulation of NRs by posttranslational modifications and cofactors. Bert O’Malley presented exciting data about an unexpected role of steroid receptor coactivator 3 (SRC3) in the cytoplasm. Previous studies showed that these NR coactivators are involved in multiple signaling pathways leading to breast cancerogenesis. In the present study the role of SRC-3 in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mediated signaling was investigated. O’Malley and co-workers ( 10) discovered that a splice variant lacking exon 4 (designated SRC3Δ4) devoid of nuclear localization sequences localize with the focal adhesion kinase 1 (FAK1). EGFR-dependent stimulation of FAK1 is augmented by SRC3Δ4, and this requires interaction with p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1). PAK1 phosphorylates SRC3Δ4 at S569/S676, which turned out to be crucial for activation of FAK1. FAK1 activation by SRC3Δ4 facilitates migration of cells triggered by integrin activation. Thus, these data show that SRC3 is involved in transformation not only by coactivating growth-related transcription factors but also by fulfilling cytoplasmic functions facilitating EGFR signaling on the migration machinery of a cell. Muriel Le Romancer spoke about the nongenomic action of estrogen through activation of downstream cellular kinase cascades ( 11). She found that estrogen-induced ERα arginine methylation by protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) promotes interaction with SRCs, phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase, and FAK1, thereby inducing cell proliferation through the protein kinase B (PKB/AKT) signaling pathway. Interestingly, she also showed that the newly identified arginine demethylase JMJD6 interacts in an estrogen-dependent manner with methylated ERα and SRCs in the cytoplasm, suggesting that JMJD6 is a new ERα partner involved in nongenomic estrogen signaling.

The AR binds directly and indirectly to DNA. Within its direct binding sites there are two types of response elements, i.e. so-called classical androgen response elements (AREs) that share their sequence with the GR and progesterone receptor response elements, and selective AREs that are recognized by the AR only ( 12). The laboratory of Frank Claessen generated a modified AR gene, in which the exon encoding the second Zn finger domain was exchanged by the homologous exon from the GR, and introduced this into the germ line of mice. These “specificity-affecting AR knock-in” (SPARKI) mice carry a mutant AR which binds classical AREs but only poorly recognizes selective AREs. In contrast to what is the case in AR-deficient mice, the anabolic effects of androgens, such as bone and muscle integrity, seem to be maintained in the SPARKI mice. However, reproductive organs are in part affected, e.g. there is a reduction of the testis size and a reduction of Sertoli cell and germ cell number ( 13). Thus, using SPARKI mice the physiological relevance of each type of ARE can be dissected in vivo. Michael Stallcup presented that cell cycle and apoptosis regulator 1 (CCAR1) and Flightless-I (Fli-I) coordinate the actions of various coactivator complexes ( 14). He showed that although subunits of SWI/SNF (SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable) and Mediator complexes can bind directly to ER, the presence of CCAR1 and Fli-I augment recruitment of Mediator and SWI/SNF complexes, respectively, to target gene promoters and thereby increases hormone-dependent expression of ER target genes. Didier Picard ( 15) showed that ERα responses can be controlled at multiple levels. He presented evidences on how the levels of ERα are subject to regulation by microRNAs, most notably miR-22. Furthermore, Picard and colleagues ( 16) discovered that the activation of ERα by cAMP is mediated by a PKA-dependent phosphorylation of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1), which enables CARM1 to bind the unliganded ligand binding domain of ERα through a novel regulatory surface. Picard presented evidence that this mechanism also appears to be at play in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells.

Two presentations reported on the dual roles of certain coregulators. transcriptional intermediary factor 1β (TIF1β) was initially identified as transcriptional corepressor for many transcription factors. Strikingly, Jacques Drouin’s work ( 17) documented a coactivator function for TIF1β and implicated this coregulator in hormone responsiveness mediated by Nurr77/NGFIB/NR4A1 and related NRs. He showed that TIF1β interacts directly with the activation function 1 (AF-1) domain of NGFIB and demonstrated a synergistic activation of NGFI-B-dependent transcription by TIF1β and SRC2/TIF2. Malcom Parker showed that the dual coregulator receptor interacting protein of 140 kDa (RIP140) can function as a corepressor of PPARγ coactivator 1 target genes, including uncoupling protein 1, and that this involves epigenetic changes through recruitment of a repression complex containing the methyltransferase G9a, histone deacetylases, and DNA methylase 1 (Dnmt1) ( 18). On the other hand Parker’s group has now found that RIP140 may also function as a coactivator for non-NR transcription factors. He reported that RIP140 interacts with CREB binding protein and p65 and stimulates proinflammatory gene expression through nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) binding sites ( 19). Interestingly, RIP140 appears in addition to activate brain and muscle Arnt-like protein (Bmal) transcription through retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor binding sites, and Parker reported that the hepatic expression of clock genes Bmal, Clock, Period 1 and 2, and Cryptochrome 2 was down-regulated in RIP140 KO mice.

Daniel Metzger presented analyses of TIF2(i)skm−/− mice in which the SRC2/TIF2 is selectively ablated in skeletal muscle myocytes at adulthood. The results showed that TIF2 tunes energy metabolism in skeletal muscle myocytes by limiting mitochondrial uncoupling, thereby indicating that TIF2 is a potential drug target to prevent metabolic disorders. Emily Faivre from Holy Ingraham’s group reported that lysine sumoylation serves as an active posttranslational mark that modulates the ability of steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) to regulate small ubiquitin-like modifier-sensitive target genes ( 20). She presented data showing that the most dramatic effect of SF-1 sumoylation is the selective loss of all DNA binding at noncanonical SF-1 binding sites suggesting that sumoylation reduces recognition of small ubiquitin-like modifier-sensitive genes thereby modifying SF-1 transcriptional programs. Shigeaki Kato provided evidence that GlcNAcylation (addition of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine) of the histone lysine methyltransferase MLL5 by the β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (O-GlcNAc) facilitates ATRA-induced granulopoiesis in human HL60 promyelocytes through methylation of H3 lysine 4 (H3K4). MLL5 was identified as a multi-subunit complex and characterized as a novel ligand-dependent RAR coactivator complex ( 21). In addition, Kato also reported the interesting observation that vitamin D induces methylation of the 5mCpG sites of the promoter of the CYP27B1 gene, whereas parathyroid hormone induces active demethylation of the 5mCpG sites in this promoter, indicating that methylation switching at the DNA level contributes to the hormonal control of transcription ( 22).

Inflammation

Two talks dealt with the role of NRs in inflammation. It is known that proinflammatory signals inhibit while antiinflammatory signals promote PPARγ activity in several cell types. Balint L. Balint from the group of Laszlo Nagy reported that in macrophages and dendritic cells, signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (Stat6) is activated by IL-4 and is necessary for PPARγ-mediated activation of target genes. As an example, Stat6 binds to a response element in the fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) enhancer, through which it appears to cooperate with PPARγ. Eckardt Treuter spoke about the molecular mechanisms by which LXRα/β and the liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1), in addition to their well-established roles in lipid metabolism, trans-repress the hepatic acute phase response. He reported that selective synthetic agonists for either receptor induce sumoylation-dependent recruitment onto acute phase response genes such as haptoglobin, thereby preventing corepressor complex clearance. Interestingly, the antiinflammatory actions of LXR agonists in liver appear selectively mediated by the LXRβ subtype, which may stimulate pharmacological development. Moreover, the coregulator G-protein suppressor 2, which the group previously found to be associated with either coactivator or corepressor complexes at metabolic receptor target genes in liver, was demonstrated to function as a hitherto unrecognized trans-repression mediator of interactions between sumoylated receptors and inflammatory genes ( 23).

Most autoimmune diseases are treated with glucocorticoids, which signal through GR to block gene expression of proinflammatory cytokines by suppressing activator protein 1, NF-κB, or interferon regulatory factor 3 activity. Inez Rogatsky reported that glucocorticoids also attenuate interferon-induced gene expression under the control of the Janus kinase/Stat pathway. The GR depletes SRC2/TIF2 from the heterotrimeric interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 transcription factor complex (Stat1/Stat2/interferon regulatory factor 9). This leads to the inhibition of promoter occupancy by interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 transcription factor complex and of transcription of interferon target genes.

Metabolism

A large number of talks dealt with the involvement of NRs in metabolic regulation. Ron Evans reported on two papers about novel interactions between NRs and AMP activated kinase (AMPK) and their role in exercise and circadian rhythm. He showed that training or AMPK agonists activate the AMPK substrate coactivator PPARγ coactivator 1α, which in turn potentiates PPARβ/δ activation of gene programs involved in fatty acid and oxidative metabolism. This leads to an increase in the amount of oxidative low-twitch muscle fibers. Intriguingly, AMPK agonists combined with PPARβ/δ agonists can replace training, thereby opening the possibility to enhance performance of muscles in pathological conditions ( 24). Furthermore, in a recently published study the importance of AMPK activity in resetting the circadian clock was demonstrated. Using a mass spectrometry approach the group of Ron Evans ( 25) identified the circadian clock regulatory factor Cry1 as a substrate for AMPK. Cry1 expression is under the control of the clock genes Bmal1 and CLOCK, but Cry also directly interferes with and inactivates the DNA bound Bmal1/CLOCK heterodimeric complex, thereby generating negative feedback loop that contributes to the rhythmic activity of Bmal/CLOCK. AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of Cry leads to its degradation as demonstrated in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and in livers of mice by AMPK agonist treatment. Interestingly, AMPK activity was found to be rhythmic, and genetic disruption of AMPK or its upstream activating serine/threonine kinase LKB1 ameliorated the rhythmic behavior of a Bmal1-luciferase reporter gene. Furthermore, active AMPK was required to reset the rhythmic behavior of the reporter gene. Thus being controlled by AMPK, Cry1 serves as a nutrient sensor to reset the peripheral clocks and adapt these to requirements of nutrition. Recent work by Walter Wahli and co-workers ( 26) demonstrated that in mouse liver PPARα has female-dependent repressive actions on genes involved in steroid metabolism. PPARα represses the expression of the cytochrome P450 Cyp7B1 gene, which is negatively involved in androgen biosynthesis and positively involved in ER activity. PPARα activity thereby antagonizes estrogen-induced hepatoxicity and inflammation, indicating that PPARα agonist therapy might be used to counteract the negative side effects of postmenopausal estrogen therapy. Furthermore, Wahli showed that agonists induce sumoylation of PPARα and that repression is dependent on this sumoylation. Sumoylated PPARα interacts with the GA binding protein α (GABPα) in the Cyp7B1 promoter leading to DNA methylation, reduced binding of the general transcription factor Sp1, and repression of the gene. PPARγ agonism is known to exert insulin-sensitizing and therefore antilipolytic effects in adipocytes. Eric Kalkhoven ( 27) reported that the genes encoding the antilipolytic G-protein-coupled receptors GPR81 and GPR109A are novel PPARγ target genes in human as well as mouse adipocytes. The genes are positioned head to tail and may be coordinately regulated through a single conserved PPARγ binding site identified by ChIP-seq analysis in the proximal promoter of the GPR81 gene. These results indicate a novel mechanism by which PPARγ agonists can exert their antilipolytic action. Noa Noy ( 28) reported that ATRA activates different NRs depending on the relative expression of the retinoic acid binding proteins cellular retinoic acid binding protein II (CRABP-II) and fatty acid binding protein 5 (FABP5). Thus, in preadipocytes, ATRA binds CRABP-II and activates RAR, which represses adipogenesis through induction of Krüppel like factor 2 (KLF2) and preadipocyte factor 1 (Pref-1). In adipocytes, ATRA binds FABP5 and activates PPARβ/δ in addition to RAR, thereby enhancing lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation and depleting lipid stores. In obese animal models, administration of ATRA led to improved glucose tolerance and loss of fat mass–effects that resulted from ATRA-induced activation of both PPARβ/δ and RAR.

Activation of LXR stimulates cholesterol efflux through ABC transporters and inhibits cholesterol uptake via the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) in macrophages and hepatocytes. Recently, the Peter Tontonoz group ( 29) reported that the LDLR protein is redistributed and significantly destabilized in hepatoma cells in response to LXR agonists and that a novel LXR target gene, Idol, mediates this effect. Idol is an E3 ligase that triggers ubiquitination of the cytoplasmic domain of LDLR, thereby targeting it for degradation. The protein is expressed in many different cell types; however, the responsiveness to LXR regulation varies. Expression is highly LXR-dependent in macrophages but only mildly LXR-dependent in liver. Ectopic expression of Idol in mouse liver leads to a rise in plasma LDL in an LDLR-dependent way. The carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP) is known to mediate transcriptional activation of gene expression in response to glucose. In addition, LXR activity has been reported to be increased by glucose, but the importance and mechanisms are controversial. Catherine Postic’s group ( 30) has demonstrated that glucose regulation of gene expression is similar in wild-type and LXRα/β knockout mice. In addition, she presented work showing that ChREBP is required for glucose-induced lipogenesis in the liver and that ChREBP may be able to restore lipogenesis in the liver of LXRα/β knockout mice. These results indicate that ChREBP activates lipogenesis independently of LXR.

Caloric restriction has been shown to block the estrous cycle through the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis. Recent results from Adriana Maggi and co-workers have shown that a hyperproteic diet partly rescues the estrous cycle, thereby suggesting that low levels of proteins is a key component linking shortage of food and malnutrition with the estrous cycle. Interestingly, the group showed that shortage of proteins decreases ER activity in mouse liver, whereas amino acids activate ER in liver. Amino acids do not bind directly to ER but activates the receptor through protein kinase A (PKA), phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase, and the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)-dependent mechanisms. The activation of ER by amino acids in liver leads to increased expression and secretion of insulin-like growth factor 1, whereas mice lacking insulin-like growth factor 1 do not display the inhibitory effect of caloric restriction on the estrous cycle. These results identify a novel mechanism by which shortage of food and malnutrition can interfere with the estrous cycle and suggest that the liver acts as an integrator of nutritional signals affecting the estrous cycle.

Bile acids function as both emulsifiers for lipids during digestive processes and as ligands for the farnesoid X receptors. More recently, a G-protein-coupled receptor, TGR5, was recognized to induce PKA-dependent signaling upon bile acid binding, and this receptor was suggested to be involved in metabolic disorders by altering energy expenditure in muscle and brown adipose tissue ( 31). Kristina Schoonjans and her colleagues ( 31) reported now that TGR5 protects liver from steatosis, prevents hypertrophy of pancreatic islets, and enhances insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance in obese mice. TGR5-overexpressing mice were protected against these aspects of diet-induced obesity, whereas TGR5 knockout mice exhibited exacerbated insulin resistance. In addition, Schoonjans showed in a pharmacological approach that specific agonists of TGR5 rescue obese mice from insulin resistance. Furthermore, she showed that activation of TGR5 in L cells of the intestine induces the expression and secretion of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which has been documented to have many beneficial effects in amelioration of the metabolic syndrome. Thus, intervention with bile acid derivates that distinguish between farnesoid X receptor and TGR5 activation could be promising drugs for combating the metabolic syndrome. David Moore talked about the identification of novel phosphatidylcholine species as liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1) agonist ligands. He reported on the antidiabetic and antiinflammatory effects of these compounds in mouse models and showed that their effects are mediated by LRH-1. Moore also indicated that a human clinical trial to test these antidiabetic effects on obese people has been initiated.

A curiosity in the NR field is that in humans 48 NRs are identified, whereas the nematode C. elegans, a small organism with 959 cells, has 248 genes encoding NRs. All of these were orphan receptors until David Mangelsdorf and colleagues ( 32) identified the ligand for DAF-12, which is a NR involved in “dauer formation,” a larval duration phase, which occurs when nutrient supply is limited. The ligand for DAF-12 is Δ4-dafachronic acid and Δ7-dafachronic acid, both of which are synthesized from precursor molecules by a P450 enzyme encoded by the gene daf-9. Parasitic nematode species exhibit a stage during larval development called iL3 that is similar to the dauer diapause stage of free-living species. Dafachronic acids were found to trigger premature recovery from the iL3 stage, which led to killing of the parasitic worms. Mangelsdorf and his group cloned the DAF-12 orthologues in these worms and solved the crystal structure of the LBD bound to dafachronic acid. These results identify DAF-12 as a novel NR drug target in parasitic nematodes that can be exploited to combat these parasites.

Development and Cancer

It was long believed that white and brown adipocytes arise from a common precursor. This notion was supported by the very similar gene expression programs and by the finding that some white adipose depots could trans-differentiate to brown adipocytes (e.g. by pharmacological activation of the β3-adrenergic receptor). Interestingly, however, the laboratory of Bruce Spiegelman has found that brown adipocytes are derived from myoblastic myogenic factor 5 (Myf5)-positive precursors in vivo, and that in vitro differentiation of myoblasts to the brown adipocyte lineage requires the coregulator PRD1-BF1-RIZ1 homologous domain containing 16 (PRDM16). Mice deficient in PRDM16 die at birth, but investigations of the embryos show that brown adipose tissue depots have significantly lower levels of brown and higher levels of white adipocyte specific gene expression in their adipose depot ( 33). PRDM16 coactivates C/EBPβ, previously reported to play a role in brown adipocyte differentiation, and ectopic expression of PRDM16 and C/EBPβ is sufficient to activate the brown adipocyte specific gene program in vitro in several cell types including skin fibroblasts ( 34). Furthermore, new data from the Spiegelman laboratory showed that ectopic expression of PRDM16 and C/EBPβ in transplanted fibroblasts is sufficient to drive a full program of brown adipogenesis in vivo. Interestingly, mice with transgenic expression of PRDM16 in white adipose depots are resistant to high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, thereby showing that PRDM16 is sufficient to switch on the entire brown adipocyte gene program in an adipocyte setting in vivo. Jan Tuckermann reported on the molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Using conditional targeting of the GR in mice he and his co-workers could demonstrate that glucocorticoids lead to bone loss via activation of GR in osteoblasts. Interestingly, inhibition of bone formation by the GR in osteoblasts was independent of GR dimerization and relied, at least in isolated cells, in part on suppression of IL-11 expression, which is controlled by c-jun/activator protein 1. Conversely, IL-11 counteracts glucocorticoid suppression of osteoblast differentiation. These results reveal novel mechanisms of this severe side effect of glucocorticoid therapy (Rauch A, Seitz S, Baschant U, Schilling AF, Illing OS, Schinke T, Spanbroek R, Zaiss M, Angel PE, Lerner UH, David JP, Reichard HM, Amling M, Schütz G, Tuckermann JP 2010 Glucocorticoids suppress bone formation by attenuating osteoblast differentiation via the monomeric glucocorticoid receptor. Cell metabolism 11:517–531).

MicroRNAs as a novel step in gene regulation have also arrived at the NR field. Not only do NRs regulate microRNA expression, but they are also targeted by microRNAs themselves, conforming negative feedback loops. Carlos P. Fitzsimons ( 35) reported that GR protein expression and GR target genes are suppressed by miR-18 and miR-124a. Reporter assays revealed binding of miR-124a, a brain-specific microRNA, to the 3′ untranslated region of GR, and miR-124a up-regulation during neuronal differentiation of P19 mouse stem cells is associated with a decreased amount of GR protein levels and reduced activity. Interestingly, miR-124a expression varies during the stress hyporesponsive period in early postnatal life in rodents. This could explain the reduced glucocorticoid signaling during this period, protecting neuronal development. Loss-of-function experiments to determine the role of endogenously expressed microRNA will clarify the impact of microRNAs as novel regulators of GR expression.

Thyroid hormones are important in numerous development processes, and the laboratory of Michela Plateroti has investigated the necessity of these hormones in the developing gut. Hypothyroid mice exhibit strong reduction of crypt cell proliferation in the small intestine, which is specifically mediated by thyroid hormone receptor α1 (TRα1) in the epithelial cells through regulation of the Wnt and other signaling pathways that play a key role in the physiopathology of this tissue. Finally, data were presented showing a role of TRα1 in gut tumor development in mouse, due to its cooperation with the Wnt pathway ( 36). Ana Aranda reported on the action of TRs in epithelial homeostasis of the skin. Despite elevated malignant tumorigenesis in hypothyroid mice as well as TRα1 and TRβ knockout mice ( 37), the initial hyperplastic response induced by phorbol ester and retinoid topical treatment is diminished. These mice are also defective in anagen entry of the hair growth cycle, develop alopecia after serial depilation, and exhibit slower kinetics in the wound healing response. Epidermal cells lacking thyroid responses displayed slower proliferation, but enhanced motility, and accumulation of CD34-positive stem cell-like cells in their niche in the hair bulge in TR−/− mice was observed. Thus, TRs are required for epithelial homeostasis under challenging conditions such as hair loss, wound healing, and tumorigenesis initiation.

PPARβ/δ is highly expressed in several parts of the brain, but the role of PPARβ/δ in the brain is currently not known. Laure Quinondon from the group of Beatrice Desvergne reported that PPARβ/δ−/− mice develop hydrocephalus. This partially penetrant phenotype is associated with an impaired development of the axon tracts. Expression microarrays show that the knockout animals have reduced expression of L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM) and ankyrin 2 proteins that have previously been causally associated with hydrocephalus. The data suggest that PPARβ/δ could be a potential drug target for some neurological disorders. Jan Åke Gustafsson ( 38) spoke about novel actions of LXR subtypes based on work with mouse models with genetic ablation of the two subtypes. As previously reported, male LXRβ−/− mice have lipid accumulation and loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord, resulting in impaired motor coordination. Ten percent of the female LXRβ−/− mice develop seizures. In addition, male LXRβ−/− mice are significantly more sensitive to the neurotoxic effects of the phytosterol and the LXR agonist β-sitosterol. In older animals, β-sitosterol leads to death of motor neurons in the spinal cord and loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. β-sitosterol has been implicated in the development of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and these results therefore suggest that alterations in LXR expression and activity may play a role in the predisposition to this disease. As a follow-up on these studies, Gustafsson and collaborators ( 39) have recently shown that activation of LXRs with oxysterols increased the number of dopaminergic neurons in mouse embryonic stem cells and increased neurogenesis and the number of mature dopaminergic neurons in human embryonic stem cells.

Günther Schütz reported new insights into the involvement of the orphan NR Tailless (Tlx) in neural stem cell function in the adult brain by exploiting elegantly cell type-specific gain- and loss-of-function approaches in mice ( 40). In particular, his laboratory demonstrated that in the sub ventricular zone Tlx is expressed in astrocyte-like B cells. By tamoxifen-induced ablation of Tlx in these cells using a Tlx promoter CreER-T2 fusion, self-renewal was strongly reduced and neurogenesis subsequently impaired. Overexpression of Tlx in bacterial artificial chromosome-transgenic mice led to a dose-dependent increase in neural stem cell self-renewal and proliferation. Interestingly, when Tlx-overexpressing mice were crossed to p53-deficient mice, glioma-like lesions occurred. In conclusion, Tlx is a crucial regulator of adult neural stem cells and involved in brain tumor formation. Orla Coneely elucidated the mechanism of Nurr77/NGFIB/NR4A1 and NOR1/NR4A3 tumor suppressor function in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) ( 41). In AML patients both receptors are down-regulated in blast cells. Moreover, NR4A1 and NR4A3 were shown to be essential for the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), because simultaneous deletion of both genes in mice led to a strong proliferative response of HSCs and thereby loss of quiescence ( 41). More importantly, in mice lacking both receptors hematopoietic cells could be isolated capable of initiating AML when transplanted into recipient mice. Coneely furthermore presented data demonstrating that loss of NR4A1 and NR4A3 is associated with an alteration in the expression of genes involved in cell cycle control and with an increased expression of genes involved in oxidative glycolysis, a classical feature of cancer cells. These data indicate an integrative function of NR4A receptors in the control of metabolism and cell cycle in HSCs and suggest that this receptor is involved in preventing aberrant proliferation. Roland Schüle presented a row of elegant studies illustrating how biochemical and molecular analysis of AR-mediated chromatin modification can be directly translated into strategies to attenuate tumor growth. Schüle’s group showed that in the presence of ligands, the AR associates with the protein kinase C-related kinase 1 (PKR1). This complex activates protein kinase Cβ, which subsequently phosphorylates H3 threonine 6. Phosphorylation at T6 blocks demethylation of di- and monomethylation of H3K4 and redirects lysine-specific demethylase 1 to demethylate H3K9. These in turn lead to the demethylation at H3K9, which facilitates androgen-induced transcription. By the identification of the phosphorylation site H3T6, a novel marker for malignancy was established in prostate cancer, exhibiting a strong correlation of immunohistochemical reactivity against H3T6 with the Glieson score. In a second set of experiments Schüle and co-workers ( 42) demonstrated that inhibition of lysine-specific demethylase 1 does indeed lead to a regression of prostate cancers in animal models, thereby clearly illustrating that the molecular understanding of AR dependent chromatin remodeling opens novel possibilities to treat this life threatening malignancy.

Conclusion

The data presented at the EMBO meeting convincingly demonstrated that NRs hold the key to the understanding of an ever-growing number of cellular, physiological, and pathophysiological processes, many of which are just beginning to be unraveled. As easy drugable proteins, these receptors are excellent examples of how basic understanding of transcription can be directly translated into drug design and novel paradigms for treatment of diseases. Thus, as concluded by Keith Yamamoto, one of the co-organizers of the conference, the NRs are the perfect example of “translational medicine: insights in molecular mechanisms directly pave the way for novel successful therapeutic strategies to combat diseases.” The many exciting new developments in the field make us all look forward to the next NR EMBO conference to be held in 2011.

Fig. 2.

The authors: Jan Tuckermann, Susanne Mandrup, and William Bourguet.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Coregulators: AIB1 | NCOR | PRMT1 | SMRT | TBL1;

Ligands: 15-Deoxy-Δ12 | all-trans-Retinoic acid;

Nuclear Receptors: AR | ER-α | GR | LXR-α | PPAR-γ | RAR-α | RXR-α | VDR.

Footnotes

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online June 2, 2010

Abbreviations: AML, Acute myeloid leukemia; AMPK, AMP-activated kinase; AR, androgen receptor; ARE, androgen response element; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; Bmal, brain and muscle Arnt-like protein; C/EBP, CAAT/enhancer binding protein; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; ChIP-seq, ChIP combined with deep sequencing; ChREBP, carbohydrate response element binding protein; DBD, DNA binding domain; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ER, estrogen receptor; FABP4/5, fatty acid binding protein 4/5; FAK1, focal adhesion kinase 1; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; FoxA1, forkhead-box A1; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; H3, histone 3; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; Klf-1, Krueppel-like factor 1; LBD, ligand binding domain; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LDLR, LDL receptor; LRH-1, liver receptor homolog-1; LXR, liver X receptor; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NR, nuclear receptor; PGJ2, prostaglandin J2; PKA/B, protein kinase A/B; PML-RARα, promyelocytic leukemia-retinoic acid receptor α; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ; PPRE, PPAR response element; PRDM16, PRD1-BF1-RIZ1 homologous domain containing 16; RIP140, receptor interacting protein of 140 kDa; RXR, retinoid X receptor; SF-1, steroidogenic factor 1; SMRT, silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors; SPARKI, specificity-affecting AR knock-in; SRC-3, steroid receptor coactivator 3; Stat, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TIF, transcriptional intermediary factor; TRα1, thyroid hormone receptor α1.

References

- 1.Mitchell JA, Fraser P2008. Transcription factories are nuclear subcompartments that remain in the absence of transcription. Genes Dev 22:20–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenfelder S, Sexton T, Chakalova L, Cope NF, Horton A, Andrews S, Kurukuti S, Mitchell JA, Umlauf D, Dimitrova DS, Eskiw CH, Luo Y, Wei CL, Ruan Y, Bieker JJ, Fraser P2010. Preferential associations between co-regulated genes reveal a transcriptional interactome in erythroid cells. Nat Genet 42:53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stavreva DA, Wiench M, John S, Conway-Campbell BL, McKenna MA, Pooley JR, Johnson TA, Voss TC, Lightman SL, Hager GL2009. Ultradian hormone stimulation induces glucocorticoid receptor-mediated pulses of gene transcription. Nat Cell Biol 11:1093–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martens JH, Brinkman AB, Simmer F, Francoijs KJ, Nebbioso A, Ferrara F, Altucci L, Stunnenberg HG2010. PML-RARα/RXR alters the epigenetic landscape in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell 17:173–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogawa S, Lozach J, Benner C, Pascual G, Tangirala RK, Westin S, Hoffmann A, Subramaniam S, David M, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK2005. Molecular determinants of crosstalk between nuclear receptors and toll-like receptors. Cell 122:707–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lalloyer F, Pedersen TA, Gross B, Lestavel S, Yous S, Vallez E, Gustafsson JA, Mandrup S, Fievet C, Staels B, Tailleux A2009. Rexinoid bexarotene modulates triglyceride but not cholesterol metabolism via gene-specific permissivity of the RXR/LXR heterodimer in the liver. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29:1488–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin CY, Vega VB, Thomsen JS, Zhang T, Kong SL, Xie M, Chiu KP, Lipovich L, Barnett DH, Stossi F, Yeo A, George J, Kuznetsov VA, Lee YK, Charn TH, Palanisamy N, Miller LD, Cheung E, Katzenellenbogen BS, Ruan Y, Bourque G, Wei CL, Liu ET2007. Whole-genome cartography of estrogen receptor α binding sites. PLoS Genet 3:e87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Chandra V, Huang P, Hamuro Y, Raghuram S, Wang Y, Burris TP, Rastinejad F2008. Structure of the intact PPAR-γ-RXR- nuclear receptor complex on DNA. Nature 456:350–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meijsing SH, Pufall MA, So AY, Bates DL, Chen L, Yamamoto KR2009. DNA binding site sequence directs glucocorticoid receptor structure and activity. Science 324:407–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long W, Yi P, Amazit L, LaMarca HL, Ashcroft F, Kumar R, Mancini MA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW2010. SRC-3Δ4 mediates the interaction of EGFR with FAK to promote cell migration. Mol Cell 37:321–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Romancer M, Treilleux I, Bouchekioua-Bouzaghou K, Sentis S, Corbo L 29 January 2010. Methylation, a key step for nongenomic estrogen signaling in breast tumors. Steroids pmid 20116391 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Claessens F, Denayer S, Van Tilborgh N, Kerkhofs S, Helsen C, Haelens2008. Diverse roles of androgen receptor (AR) domains in AR-mediated signaling. Nucl Recept Signal 6:e008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Schauwaers K, De Gendt K, Saunders PTK, Atanassova N, Haelens A, Callewaert L, Moehren U, Swinnen JV, Verhoeven G, Verrijdt G, Claessens F2007. Loss of androgen receptor binding to selective androgen response elements causes a reproductive phenotype in a knockin mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:4961–4966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong KW, Lee YH, Stallcup MR2009. Recruitment of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex to steroid hormone-regulated promoters by nuclear receptor coactivator flightless-I. J Biol Chem 284:29298–29309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandey DP, Picard D2009. miR-22 inhibits estrogen signaling by directly targeting the estrogen receptor α mRNA. Mol Cell Biol 29:3783–3790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carascossa S, Dudek P, Cenni B, Briand PA, Picard D2010. CARM1 mediates the ligand-independent and tamoxifen-resistant activation of the estrogen receptor α by cAMP. Genes Dev 24:708–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rambaud J, Desroches J, Balsalobre A, Drouin J2009. TIF1β/KAP-1 is a coactivator of the orphan nuclear receptor NGFI-B/Nur77. J Biol Chem 284:14147–14156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiskinis E, Hallberg M, Christian M, Olofsson M, Dilworth SM, White R, Parker MG2007. RIP140 directs histone and DNA methylation to silence Ucp1 expression in white adipocytes. EMBO J 26:4831–4840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zschiedrich I, Hardeland U, Krones-Herzig A, Berriel Diaz M, Vegiopoulos A, Muggenburg J, Sombroek D, Hofmann TG, Zawatzky R, Yu X, Gretz N, Christian M, White R, Parker MG, Herzig S2008. Coactivator function of RIP140 for NFκB/RelA-dependent cytokine gene expression. Blood 112:264–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell LA, Faivre EJ, Show MD, Ingraham JG, Flinders J, Gross JD, Ingraham HA2008. Decreased recognition of SUMO-sensitive target genes following modification of SF-1 (NR5A1). Mol Cell Biol 28:7476–7486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiki R, Chikanishi T, Hashiba W, Ito H, Takada I, Roeder RG, Kitagawa H, Kato S2009. GlcNAcylation of a histone methyltransferase in retinoic-acid-induced granulopoiesis. Nature 459:455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MS, Kondo T, Takada I, Youn MY, Yamamoto Y, Takahashi S, Matsumoto T, Fujiyama S, Shirode Y, Yamaoka I, Kitagawa H, Takeyama K, Shibuya H, Ohtake F, Kato S2009. DNA demethylation in hormone-induced transcriptional derepression. Nature 461:1007–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venteclef N, Jakobsson T, Ehrlund A, Damdimopoulos A, Mikkonen L, Ellis E, Nilsson LM, Parini P, Janne OA, Gustafsson JA, Steffensen KR, Treuter E2010. GPS2-dependent corepressor/SUMO pathways govern anti-inflammatory actions of LRH-1 and LXRβ in the hepatic acute phase response. Genes Dev 24:381–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narkar VA, Downes M, Yu RT, Embler E, Wang YX, Banayo E, Mihaylova MM, Nelson MC, Zou Y, Juguilon H, Kang H, Shaw RJ, Evans RM2008. AMPK and PPARδ agonists are exercise mimetics. Cell 134:405–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamia KA, Sachdeva UM, DiTacchio L, Williams EC, Alvarez JG, Egan DF, Vasquez DS, Juguilon H, Panda S, Shaw RJ, Thompson CB, Evans RM2009. AMPK regulates the circadian clock by cryptochrome phosphorylation and degradation. Science 326:437–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leuenberger N, Pradervand S, Wahli W2009. Sumoylated PPARα mediates sex-specific gene repression and protects the liver from estrogen-induced toxicity in mice. J Clin Invest 119:3138–3148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeninga EH, Bugge A, Nielsen R, Kersten S, Hamers N, Dani C, Wabitsch M, Berger R, Stunnenberg HG, Mandrup S, Kalkhoven E2009. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ regulates expression of the anti-lipolytic G-protein-coupled receptor 81 (GPR81/Gpr81). J Biol Chem 284:26385–26393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berry DC, Noy N2009. All-trans-retinoic acid represses obesity and insulin resistance by activating both peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor β/δ and retinoic acid receptor. Mol Cell Biol 29:3286–3296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zelcer N, Hong C, Boyadjian R, Tontonoz P2009. LXR regulates cholesterol uptake through idol-dependent ubiquitination of the LDL receptor. Science 325:100–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denechaud PD, Bossard P, Lobaccaro JM, Millatt L, Staels B, Girard J, Postic C2008. ChREBP, but not LXRs, is required for the induction of glucose-regulated genes in mouse liver. J Clin Invest 118:956–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallim TQ, Edwards PA2009. Bile acids have the gall to function as hormones. Cell Metab 10:162–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z, Zhou XE, Motola DL, Gao X, Suino-Powell K, Conneely A, Ogata C, Sharma KK, Auchus RJ, Lok JB, Hawdon JM, Kliewer SA, Xu HE, Mangelsdorf DJ2009. Inaugural Article: Identification of the nuclear receptor DAF-12 as a therapeutic target in parasitic nematodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9138–9143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, Scime A, Devarakonda S, Conroe HM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Rudnicki MA, Beier DR, Spiegelman BM2008. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature 454:961–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kajimura S, Seale P, Kubota K, Lunsford E, Frangioni JV, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM2009. Initiation of myoblast to brown fat switch by a PRDM16-C/EBP-β transcriptional complex. Nature 460:1154–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vreugdenhil E, Verissimo CSL, Mariman R, Kamphorst JT, Barbosa JS, Zweers T, Champagne DL, Schouten T, Meijer OC, Ron de Kloet E, Fitzsimons CP2009. MicroRNA 18 and 124a down-regulate the glucocorticoid receptor: implications for glucocorticoid responsiveness in the brain. Endocrinology 150:2220–2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kress E, Skah S, Sirakov M, Nadjar J, Gadot N, Scoazec JY, Samarut J, Plateroti M2010. Cooperation between the Thyroid hormone receptor TRα1 and the WNT pathway in the induction of intestinal tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology 138:1863–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Iglesias O, Garcia-Silva S, Tenbaum SP, Regadera J, Larcher F, Paramio JM, Vennstrom B, Aranda A2009. Thyroid hormone receptor β1 acts as a potent suppressor of tumor invasiveness and metastasis. Cancer Res 69:501–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HJ, Fan X, Gabbi C, Yakimchuk K, Parini P, Warner M, Gustafsson JA2008. Liver X receptor β (LXRβ): A link between β-sitosterol and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-Parkinson’s dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:2094–2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacchetti P, Sousa KM, Hall AC, Liste I, Steffensen KR, Theofilopoulos S, Parish CL, Hazenberg C, Richter LA, Hovatta O, Gustafsson JA, Arenas E2009. Liver X receptors and oxysterols promote ventral midbrain neurogenesis in vivo and in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 5:409–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu HK, Wang Y, Belz T, Bock D, Takacs A, Radlwimmer B, Barbus S, Reifenberger G, Lichter P, Schutz G2010. The nuclear receptor tailless induces long-term neural stem cell expansion and brain tumor initiation. Genes Dev 24:683–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mullican SE, Zhang S, Konopleva M, Ruvolo V, Andreeff M, Milbrandt J, Conneely OM2007. Abrogation of nuclear receptors Nr4a3 and Nr4a1 leads to development of acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med 13:730–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metzger E, Imhof A, Patel D, Kahl P, Hoffmeyer K, Friedrichs N, Muller JM, Greschik H, Kirfel J, Ji S, Kunowska N, Beisenherz-Huss C, Gunther T, Buettner R, Schüle R2010. Phosphorylation of histone H3T6 by PKCβ(I) controls demethylation at histone H3K4. Nature 464:792–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]