Abstract

In obesity, dysregulation of adipocytokines is involved in several pathological conditions including diabetes and certain cancers. As a member of the adipocytokines, adiponectin plays crucial roles in whole-body energy homeostasis. Recently, it has been reported that the level of plasma adiponectin is reduced in several types of cancer patients. However, it is largely unknown whether and how adiponectin affects colon cancer cell growth. Here, we show that adiponectin suppresses the proliferation of colon cancer cells including HCT116, HT29, and LoVo. In colon cancer cells, adiponectin attenuated cell cycle progression at the G1/S boundary and concurrently increased expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21 and p27. Adiponectin stimulated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation whereas inhibition of AMPK activity blunted the effect of adiponectin on the proliferation of colon cancer cells. Furthermore, knockdown of adiponectin receptors such as AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 relieved the suppressive effect of adiponectin on the growth of colon cancer cells. In addition, adiponectin repressed the expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c, which is a key lipogenic transcription factor associated with colon cancers. These results suggest that adiponectin could inhibit the growth of colon cancer cells through stimulating AMPK activity.

In colon cancer cells, adiponectin inhibits proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest via AMPK. Such anti-proliferative effect of adiponectin is associated with decreased lipogenic activity.

Colorectal cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies, ranking as the second leading cause of death from cancer in the United States ( 1). Obesity, high-fat diet, and genetic alterations have been proposed to be critical risk factors for the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer ( 2). Obesity is defined as an abnormal increase of adipose tissue mass with increasing size and number of adipocytes. Adipose tissue is considered as an active endocrine organ that secretes several hormonal proteins, known as adipocytokines, and thereby actively contributes to affect whole-body energy homeostasis ( 3, 4, 5). In obesity, increased adipose tissue mass provokes adipocytokine dysregulation, which results in metabolic changes.

As a member of the adipocytokines, adiponectin is exclusively expressed from adipocytes ( 6) and acts as an insulin sensitizer ( 4). The plasma level of adiponectin is reduced in most obese animal models and human subjects, particularly in those with visceral obesity ( 7, 8), suggesting that reduced expression of adiponectin might play a causative role in the development of obesity-related metabolic complications such as type 2 diabetes. Indeed, the supplementation of adiponectin in obese mice decreases body weight and ameliorates insulin resistance ( 4). As adiponectin receptors, AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 have been identified; AdipoR1 is abundantly expressed in skeletal muscle, and AdipoR2 is predominantly expressed in liver ( 9). In peripheral tissue, it is likely that AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 mediate the effects of adiponectin on glucose utilization and fatty acid oxidation by stimulating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), although it is unclear how AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 could regulate AMPK ( 9, 10, 11, 12).

Accumulating evidence proposes that decreasing levels of plasma adiponectin are associated with development of certain cancers. For instance, an inverse correlation between serum adiponectin levels and the occurrence of several cancers, including breast, prostate, endometrial, and gastric cancers, has been reported ( 13, 14, 15, 16). Additionally, genetic variants of adiponectin, which are linked to altered level of plasma adiponectin, have been shown to closely correlate with decrease of breast cancer risk ( 17). Furthermore, recent papers indicate that adiponectin has antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects on cells derived from several types of cancer ( 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23). In accordance with these reports, it has been reported that there is a close correlation between low levels of plasma adiponectin and the risk of colon cancer ( 24, 25, 26, 27, 28), and adiponectin deficiency promotes the development of colorectal cancer in combination with a high-fat diet ( 29, 30). However, the effects of adiponectin on colon cancer cell growth are largely unclear, and the mechanism by which adiponectin might regulate the proliferation of colon cancer cells remains to be elucidated.

In this work, we have investigated the effect of adiponectin on the proliferation of colon cancer cells. We reveal that adiponectin inhibits proliferation of colon cancer cells by regulating cell cycle-regulatory molecules in an AMPK-dependent manner. Moreover, the expression of lipogenic genes and adiponectin receptors was elevated in colon cancer tissues compared with normal colon tissues, which would provide a clue to the selective antiproliferative effect of adiponectin on colon cancer cells.

Results

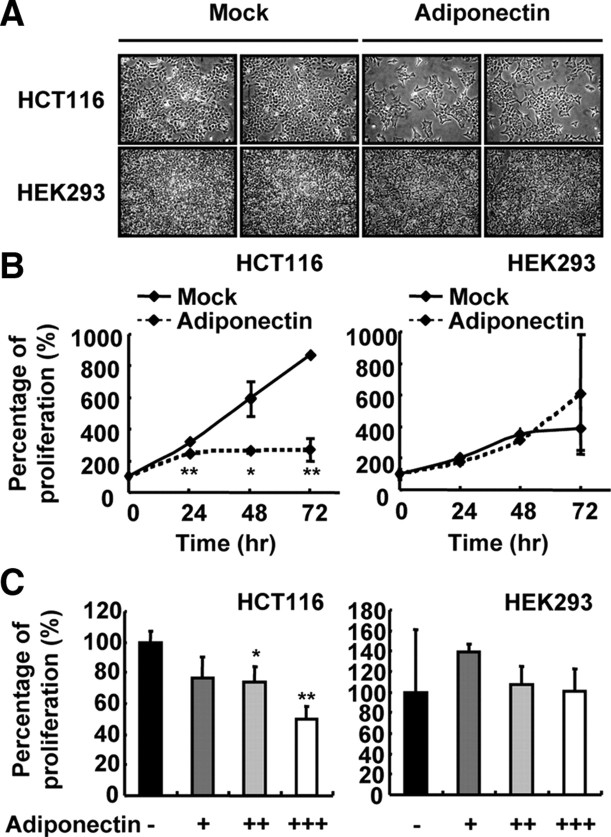

Adiponectin reduces colon cancer cell proliferation

To investigate whether adiponectin affects the growth of colon cancer cells, we treated several colon cancer cell lines including HCT116, HT29, and LoVo with adiponectin and examined their growth. When HCT116 cells were incubated with adiponectin, the proliferation of HCT116 cells was greatly decreased whereas that of human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells was not affected (Fig 1, A and B). Additionally, adiponectin decreased HCT116 cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner but did not inhibit the growth of HEK293 and RWPE1 (Fig. 1C and data not shown). Because HEK293 and RWPE1 are not colon cells, these results imply that the antiproliferative effect of adiponectin appears to be selective for colon cancer cells.

Fig. 1.

Adiponectin inhibits proliferation of HCT116 cells. A, Microscopic view of HCT116 and HEK293 cells. Cells were incubated with mock or adiponectin (∼25 μg/ml) for 48 h. B, Time-dependent effect of adiponectin on the growth of HCT116 cells. Viable cells were counted at each time point of incubation with mock or adiponectin (∼33 μg/ml). A value of 100% was assigned for the cell number before being incubated with mock or adiponectin. C, Dose-dependent effect of adiponectin in HCT116 and HEK293 cells. HCT116 and HEK293 cells were incubated with different concentrations of adiponectin for 48 h. A value of 100% was assigned to the cell number without adiponectin. +, Approximately 8 μg/ml; ++, approximately 16 μg/ml; +++, approximately 33 μg/ml. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 vs. cells incubated with mock (Student’s t test).

To further confirm the effects of adiponectin, we transfected an adiponectin expression vector into colon cancer cells and investigated their growth. Consistent with the above results (Fig. 1), adiponectin overexpression clearly reduced proliferation of colon cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner (Supplemental Fig. 1, A and B, published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). Because adiponectin significantly decreased the proliferation of many colon cancer cells including HCT116, HT29, and LoVo (Supplemental Fig. 1C), it is likely that adiponectin could repress colon cancer cell proliferation.

To confirm the inhibitory effect of adiponectin on colon cancer cell growth, we explored soft agar colony formation assay. When HCT116 cells were treated with adiponectin, the numbers of colonies were significantly decreased (Fig. 2, A and B). Furthermore, the sizes of colonies with adiponectin-incubated HCT116 cells were smaller than those of control cells (Fig. 2, A and C). These results imply that adiponectin would repress not only tumor formation but also growth of colon cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

Adiponectin suppressed colony formation. A, Microscopic view of colony formation. Suspensory single HCT116 cells were incubated with or without adiponectin (20 μg/ml) in agar containing media for 14 d. B, Total colonies were counted in 11 random microscopic fields as previously reported ( 62 ). The mean values of three independent experiments were shown. C, The diameters of colonies were measured 14 d after plating. Similar results were obtained at least more than two independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 vs. cells incubated with mock (Student’s t test).

Antiproliferative effect of adiponectin is dependent on AdipoR1 and AdipoR2

To examine whether the antiproliferative effect of adiponectin in colon cancer cells is mediated through adiponectin receptors, we repressed the expression of AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 via small interfering RNA (siRNA). To prevent off-target effects of siRNA, we used two different siRNAs, which were targeting at different regions of AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 mRNA. The knockdown efficiencies of each AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 siRNA were determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 3, A and B). When the levels of AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 mRNA were down-regulated via siRNA (40% and 60%, respectively), the inhibitory effect of adiponectin on colon cancer proliferation was relieved in colon cancer cells (Fig. 3C). Under the same condition, adiponectin-dependent AMPK phosphorylation was disturbed by knockdown of AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 in HCT116 cells (Supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). However, the reduction of either AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 expression did not affect HEK293 cell growth regardless of adiponectin (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that reduction of AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 mRNA would alleviate the adiponectin signaling in colon cancer cells and that adiponectin would selectively suppress colon cancer proliferation through adiponectin receptors.

Fig. 3.

AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 mediate the antiproliferative effect of adiponectin in colon cancer cells. To minimize off-target effects of siRNAs, we tested two different siRNAs against AdipoR1 and AdipoR2. Each siRNA sequence information is described in Supplemental Table 1. HCT116 and HEK293 cells were transfected with 20 μm siRNAs of green fluorescent protein (GFP), AdipoR1, or AdipoR2. A and B, The relative amounts of each AdipoR1/R2 mRNA against GAPDH were measured with quantitative real-time RT-PCR. C and D, The siRNA-transfected cells were incubated with or without adiponectin (∼21 μg/ml) for 48 h, and viable cells were counted. The mean values from four separate countings are presented. Similar results were obtained for at least more than three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

Adiponectin induces G1 arrest and apoptosis in colon cancer cells

The observation that adiponectin perturbed colon cancer cell proliferation led us to examine whether adiponectin might modulate cell cycle progression in colon cancer cells. HCT116 cells were incubated with adiponectin for 12 or 24 h, and cell cycle states were analyzed using flow cytometry. Compared with control cells, adiponectin-treated HCT116 cells exhibited a larger portion of the population in G1 phase and a smaller fraction of the population in S phase (Fig. 4, A and B), indicating that adiponectin would induce cell cycle arrest at G1/S boundary in colon cancer cells. However, adiponectin did not affect cell cycle progression in HEK293 cells under the same condition (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Adiponectin induces cell cycle arrest at G1 phase in HCT116. Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle regulation by adiponectin in HCT116 cells. A, HCT116 cells were incubated with mock or adiponectin (∼33 μg/ml) for 12 or 24 h. At the end of the incubation, BrdU was added to the cells to measure DNA synthesis. Then, the cells were collected and stained with an FITC-conjugated BrdU antibody and propidium iodide for flow cytometry analysis. B, The percentage of the cell population to each cell cycle stage was calculated and presented at each time point. Similar results were obtained for at least more than three independent experiments.

Interestingly, we also observed that the population of Sub-G1 phase that reflects apoptotic cells was increased by long-term incubation (72 h) in adiponectin-treated HCT116 cells (Fig. 5, A and B). To confirm the proapoptotic effect of adiponectin in colon cancer cells, we stained cells with annexin-V. As shown in Fig. 5, C and D, the annexin-V-positive population was greatly increased by adiponectin treatment into HCT116 cells. In accordance with these, adiponectin stimulated the expression of Bax, a well-known proapoptotic gene, and increased the cleavage of PARP-1, a target of activated caspase-3 in HCT116 cells (Supplemental Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, long-term incubation of adiponectin did not induce apoptosis in HEK293 (Fig. 5, C and D). These data suggest that adiponectin would induce not only cell cycle arrest but also apoptosis in colon cancer cells with the induction of proapoptotic gene expression.

Fig. 5.

Long-term treatment of HCT116 cells with adiponectin induces apoptosis. A, HCT116 cells were incubated with mock or adiponectin (∼33 μg/ml) for 72 h. At the end of the incubation, BrdU was added to cells at each time point. The cells were then collected and stained with FITC-conjugated BrdU antibody and propidium iodide for flow cytometry analysis. B, The percentage of cell population in each stage of cell cycle was calculated. C, HCT116 and HEK293 were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated annexin-V after incubation with mock or adiponectin (∼25 μg/ml) for 72 h, and flow cytometry analysis was used. D, The percentage of the annexin-V-positive cell population was calculated and presented. Similar results were obtained for at least more than two (C and D) and three (A and B) independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. cells incubated with mock (Student’s t test).

Adiponectin modulates the expression of cell cycle-regulatory genes in colon cancer cells

Because adiponectin arrested cell cycle progression at the G1 phase in colon cancer cells, we asked the question whether adiponectin might affect the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) to cause G1/S arrest. As illustrated in Fig. 6A, adiponectin substantially promoted the expression of p21 and p27 mRNAs and proteins in HCT116 cells, but not in HEK293 and RWPE1 cells (Fig. 6, A and B, and data not shown). Moreover, the protein level of cyclin E, which regulates transition from G1 to S phase, was slightly decreased in adiponectin-treated HCT116 cells, whereas such an effect was not detected in HEK293 and RWPE1 cells (Fig. 6B and data not shown). However, the levels of other cell cycle-regulatory proteins such as p53 and cyclin D were not significantly altered in HCT116, HEK293, and RWPE1 by adiponectin (Fig. 6B and data not shown). These results imply that adiponectin might provoke cell cycle arrest in colon cancer cells at the G1 phase by regulating expression of CKIs.

Fig. 6.

Adiponectin promotes the expression of p21 and p27 and decreases cyclin E in colon cancer cells. HCT116 and HEK293 cells were incubated with mock or adiponectin (∼33 μg/ml) for 48 h. A, Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis to measure relative mRNA abundance of p53, p21, and p27. Relative mRNA levels of p53, p21, and p27 were quantified after normalization against GAPDH. B, The protein levels of p53, p21, p27, CDK2, cyclin D, cyclin E, and GAPDH in the presence or absence of adiponectin in HCT116 and HEK293 cells. *, P < 0.05 (Student’s t test).

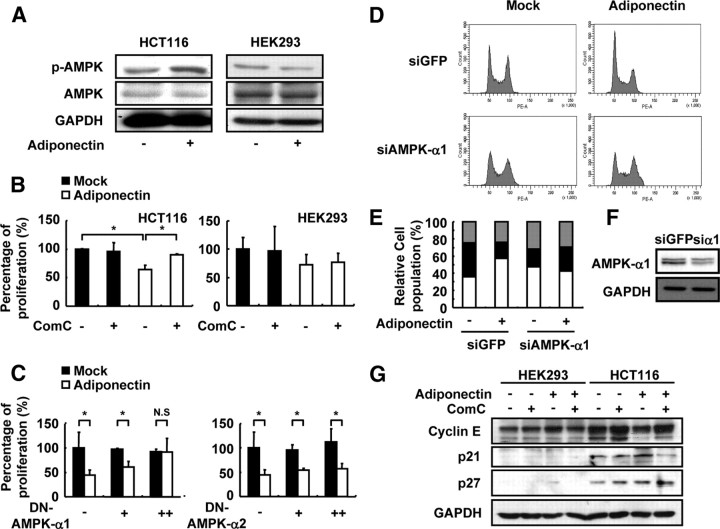

Adiponectin inhibits the proliferation of colon cancer cells via AMPK activation

It is well established that adiponectin activates AMPK and p38 MAPK to mediate its downstream signaling cascades ( 9, 10, 11, 12). To decipher the underlying signaling pathways of the antiproliferative activity of adiponectin in colon cancer cells, we examined the level of phosphorylation of AMPK and p38 MAPK in HCT116 cells upon adiponectin. As shown in Fig. 7A, adiponectin elevated AMPK phosphorylation in HCT116, but not in HEK293. However, adiponectin did not affect p38 MAPK phosphorylation in both HCT116 and HEK293 (data not shown). To test whether the inhibitory effect of adiponectin on cell cycle progression in colon cancer cells is dependent on AMPK activation, HCT116 cells were incubated with adiponectin in the absence or presence of Compound C (ComC), an AMPK inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 7B and Supplemental Fig. 4A, ComC treatment alleviated the antiproliferative activity of adiponectin in HCT116, but not in HEK293. Consistent with this observation, overexpression of dominant-negative (DN)-AMPK-α1 blunted the effect of adiponectin on colon cancer cell proliferation (Fig. 7C), clearly indicating that adiponectin suppresses colon cancer proliferation by stimulating AMPK activity. However, overexpression of DN-AMPK-α2 failed to nullify the effect of adiponectin in HCT116 (Fig. 7C) whereas it repressed AMPK activity (Supplemental Fig. 4B). In addition, when AMPK-α1 was suppressed with siRNA, adiponectin-dependent cell cycle arrest at G1 phase was remarkably alleviated (Fig. 7, D and E). Furthermore, the adiponectin-dependent reduction of cyclin E and induction of CKIs (p21 and p27) were diminished by AMPK inhibition with ComC (Fig. 7G). Together, these data indicate that adiponectin could mediate its antiproliferative effects via activation of AMPK-α1 in colon cancer cells.

Fig. 7.

Adiponectin suppresses proliferation of HCT116 via AMPK activation. A, Western blot analysis for AMPK phosphorylation by adiponectin. HCT116 and HEK293 cells were incubated with mock or adiponectin (∼25 μg/ml) for 30 min. B, Viable cell numbers were counted after incubation with mock and adiponectin (∼25 μg/ml) for 48 h in the presence or absence of ComC (2 μm). A value of 100% was assigned to the cell number without adiponectin and ComC. C, HCT116 cells were transfected with a DN form of AMPK-α1 and AMPK -α2 expression vector (+, 0.1 μg; ++, 1 μg). HCT116 cells were incubated 24 h after transfection with mock or adiponectin (∼33 μg/ml) for 48 h, and then viable cells were counted. A value of 100% was assigned for the cell number with overexpressed backbone vector and incubated without adiponectin. D–F, HCT116 cells were transfected with 20 μm green fluorescent protein (GFP) siRNA or AMPK-α1 siRNA. After transfection, HCT116 cells were incubated with mock or adiponectin (∼20 μg/ml) for 24 h. At the end of the incubation, BrdU was added to the cells, after which the cells were collected and stained with an FITC-conjugated BrdU antibody (panel D) and propidium iodide for flow cytometry analysis. E, The percentage of the cell population to each cell cycle stage was calculated. F, The efficiency of AMPK-α1 siRNA was evaluated by Western blot analysis. G, HCT116 and HEK293 cells were incubated with or without adiponectin for 48 h in the presence or absence of ComC (2 μm). Western blot analysis was performed to determine the cyclin E, p21, and p27 protein level. *, P < 0.05 (Student’s t test). N.S., Not significant.

Adiponectin decreases the expression of lipogenic genes in HCT116

It has been reported that several lipogenic genes including sterol-regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) are up-regulated in certain obesity-linked cancers such as breast, prostate, endometrial, and colon cancers ( 31, 32, 33, 34, 35). Consistent with these reports, the levels of lipogenic genes such as SREBP-1c and FAS were elevated in colon cancer tissues compared with normal tissues from the same colon cancer patients (Fig. 8A). Further, the basal levels of SREBP-1c and FAS mRNA were higher in HCT116 than in HEK293 or RWPE1 (Fig. 8B). Because AMPK has been shown to decrease lipogenic activity by repressing SREBP-1c ( 36), we examined whether adiponectin is able to suppress the expression of SREBP-1c and FAS in HCT116 cells. In colon cancer cells, adiponectin decreased the expression of SREBP-1c and FAS (Fig. 8B). In contrast, adiponectin did not alter the gene expression of other members of SREBP family such as SREBP-1a and SREBP-2 (Fig. 8C). Further, when DN-AMPK-α1 was overexpressed in HCT116 cells, the expression of SREBP-1c and FAS mRNA gene was restored in the presence of adiponectin (Fig. 8D). Consistently, suppression of AMPK-α1 with siRNA in HCT116 cells diminished the adiponectin-dependent down-regulation of SREBP-1c and FAS gene expression (Fig. 8E). In addition, when HCT116 cells were cotreated with adiponectin and ComC, the reduction of lipogenic gene expression by adiponectin was relieved (Supplemental Fig. 5). Thus, these data suggest that adiponectin would suppress colon cancer cell growth, at least partly, by inhibiting lipogenic gene expression via activation of AMPK.

Fig. 8.

Adiponectin suppresses lipogenic gene expression via AMPK activation to regulate the proliferation of colon cancer cells. A, Quantification of SREBP-1c and FAS mRNA levels in normal and colon cancer tissues from each colon cancer patient (n = 7). B, Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of mRNA abundance of SREBP-1c and FAS in HCT116 and HEK293 with or without adiponectin (∼33 μg/ml). C, The relative amounts of SREBP-1a, -1c, and -2 mRNA in HCT116 were measured with quantitative real-time RT-PCR. D and E, The relative mRNA levels of SREBP-1c and FAS were quantified after normalization against GAPDH. D, DN-AMPK-α1 was transfected in HCT116 cells and incubated with or without adiponectin (∼21 μg/ml) for 48 h. E, The siRNA for AMPK-α1 was transfected in HCT116 cells and incubated with mock or adiponectin (∼21 μg/ml) for 48 h. #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01 (paired t test). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (Student’s t test). N.S., Not significant.

Adiponectin receptors are up-regulated in colon cancer

To understand why adiponectin appears to selectively prevent the growth of colon cancer cells, we compared the expression levels of adiponectin receptors in human colon cancer tissues and normal colon tissues. Compared with normal tissues, the level of AdipoR1 mRNA expression was increased in colon cancer tissues from the same patient (Fig. 9). Although it was not statistically significant, AdipoR2 expression showed a tendency to increase in cancer tissues. On the other hand, the levels of calreticulin and T-cadherin, other adiponectin-binding proteins, were insignificantly altered in colon cancer tissues (data not shown). Thus, it appears that adiponectin might selectively inhibit colon cancer proliferation through adiponectin receptors.

Fig. 9.

AdipoR1 is up-regulated in human colon cancer tissue. Quantification of relative mRNA levels of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 in normal and colon cancer tissues from each colon cancer patient (n = 7). The relative amounts of each AdipoR1/R2 mRNA against GAPDH were measured with quantitative real-time RT-PCR. #, P < 0.05 (paired t test).

Discussion

In the present study, we reveal that adiponectin inhibits colon cancer cell proliferation via AdipoR1- and AdipoR2-mediated AMPK activation. AMPK activation in colon cancer cells by adiponectin reduced lipogenic gene expression, which is required for active proliferation of cancer cells, whereas adiponectin increased the expression of CKIs such as p21 and p27 that inhibit cell cycle progression in colon cancer cells. Further, adiponectin decreased the level of cyclin E, which is essential for cell cycle transition from G1 to S phase. Thus, it is possible to speculate that the increased p21 and p27 expression promoted by adiponectin would contribute to the control of colon cancer cell proliferation. Here, we observed that adiponectin also provoked apoptosis when HCT116 cells were incubated with adiponectin for a long-term period (>72 h). However, adiponectin did not induce cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in HEK293 or RWPE cells, implying that long-term adiponectin treatment promotes apoptosis selectively in colon cancer cells. Therefore, it is likely that extended adiponectin treatment into colon cancer cells might transit from cell cycle arrest or antiproliferation to apoptosis, concomitantly with the induction of apoptotic gene expression.

As a sensor of cellular energy status, AMPK is activated by various stresses such as low glucose levels, fasting, and exercise ( 37, 38). Recently, it has been demonstrated that AMPK could suppress cell growth and proliferation. For example, activation of AMPK with AICAR causes cell cycle arrest in certain cancer cell lines such as hepatoma HepG2, prostate carcinoma PC-3, and breast cancer MCF-7 by up-regulating tumor suppressor genes such as p53, p21, and p27 ( 39, 40, 41). Similar to these reports, we demonstrated that the suppressive effect of adiponectin on colon cancer cell proliferation was eliminated by inhibition of AMPK activity. While the present paper was in preparation, a recent paper reported that globular adiponectin prevents colon cancer cell growth via AMPK and mTOR pathway ( 42) These results are quite consistent with our findings that, in colon cancer cells, adiponectin would regulate cell cycle progression in an AMPK-dependent manner.

Many cancer cells exhibit increased lipogenic activity for rapid cell growth and division. Because the cell growth and division rates in cancer cells are higher than in normal cells, lipid metabolites such as phospholipids are crucial for maintaining membrane integrity in cancer cells ( 43). Accordingly, lipogenic genes are up-regulated to supply a lipid source in various human cancers ( 34, 35, 44, 45). In this aspect, inhibitors of lipogenic genes have been proposed as anticancer drugs. For instance, FAS inhibitors such as cerulenin and C75 exhibit potent inhibition of human cancer cell growth ( 44, 46, 47, 48). Both cerulenin and C75 also inhibit DNA replication and S-phase progression in colon cancer cells ( 44). SREBP-1c is a key transcription factor that coordinates most lipogenic genes such as FAS, acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase (ACC), and stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase (SCD) ( 49, 50, 51). Previously it has been reported that SREBP-1 regulates the expression of FAS in HCT116 ( 33). Additionally, adiponectin down-regulates SREBP-1c to decrease lipogenesis ( 52), and AMPK activator reduces de novo lipid synthesis in prostate cancer cells ( 40). Therefore, it is reasonable to propose that adiponectin would inhibit lipogenesis in certain cancer cells via AMPK activation, and consequently lead to attenuation of cell growth and proliferation. Indeed, we observed that adiponectin inhibited expression of lipogenic genes such as SREBP-1c and FAS, which is probably associated with retardation of colon cancer cell growth. More importantly, suppression of lipogenic gene expression by adiponectin was eliminated by AMPK inhibition. Because AMPK regulates lipid metabolism through increase of lipid β-oxidation and/or decrease of lipogenesis ( 53), it is plausible that activation of AMPK upon adiponectin would affect colon cancer cell proliferation via lipid homeostasis. However, it is unclear whether the change of lipogenic gene expression upon adiponectin is directly linked with expression of CKIs (i.e. p21 and p27) in colon cancer cells.

It is of interest to note that the antiproliferative effect of adiponectin is preferentially restricted to colon cancer cells but not observed in other cell lines such as HEK293 and RWPE1. As one of several plausible mechanisms, we suggest that the different expression levels of adiponectin receptors in colon cancer cells may mediate this selectivity. This idea has been supported by the report that the expression of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 was elevated in colorectal carcinomas but not in normal tissues ( 54). In addition, it has been shown that the AdipoR1-mediated pathway is more important than AdipoR2 in the effect of adiponectin on colorectal carcinogenesis under a high-fat diet condition ( 29). Similarly, we observed that the expression of AdipoR1 was elevated in colon cancer tissues compared with normal tissues. Furthermore, when the expression of AdipoR1 or AdipoR2 was down-regulated with siRNA, reduction of colon cancer proliferation by adiponectin was abolished, providing a potential explanation of how and why colon cancer cells would exhibit selective sensitivity to adiponectin. Another potential model to explain selective cancer cell sensitivity to adiponectin is that cancer cells are more sensitive to lack of lipid supply than normal cells, as suggested previously ( 45). Related to this, we observed that SREBP-1c and FAS mRNA were more highly expressed in colon cancer tissues than in normal colon tissues. Additionally, SREBP-1c expression in the colon cancer cell line HCT116 was relatively higher than in other cell lines that were not responsive to adiponectin. Thus, it is likely that reduction of lipogenesis by adiponectin in colon cancer cells might contribute to adiponectin selectivity in colon cancer cells. Of course, further studies would elucidate the mechanism by which colon cancer cells are sensitized to adiponectin and the role of adiponectin in colon cancer cell proliferation.

There are controversies for the role of adiponectin on colon cancer proliferation. Some studies have reported that the level of plasma adiponectin is not associated with risk of colon cancer and that increase of serum adiponectin does not reduce colon carcinogenesis under a high-fat diet ( 55, 56). On the other hand, a number of groups have demonstrated that the level of circulating adiponectin exhibits a negative correlation with the incidence and/or development of colon cancer ( 24, 25, 26, 27, 57). Furthermore, deficiency of adiponectin promotes colon polyp formation and increases colonic epithelial cell proliferation under the high-fat diet condition ( 29, 30). Moreover, genetic variants of adiponectin and AdipoR1 are closely connected with colon cancer risk ( 28, 58). Consistent with our findings, there are several reports that adiponectin has antiproliferative effects on colon cancer cells ( 42, 59). In these reports, they reveal that adiponectin suppresses proliferation of colon cancer cells via AMPK activation. However, they did not provide detailed mechanisms by which adiponectin represses colon cancer cell proliferation. In this study, we investigated the molecular mechanism for the anticancer property of adiponectin in colon cancer cells. We demonstrated that adiponectin induces cell cycle arrest at G1 phase by stimulating expression of CKIs and that the induction of CKIs was mediated by AMPK activation (Fig. 10). Moreover, we discovered that adiponectin decreased the expression of SREBP1c and FAS, key lipogenic genes for cell proliferation, in colon cancer cells (Fig. 10). Therefore, we believe this work suggests more detailed mechanisms of adiponectin on colon cancer cell proliferation. Because the antiproliferative effect of adiponectin appears to be selective to colon cancer cells, our data provide substantial evidences that adiponectin might be useful as a potential therapeutic target of colon cancer.

Fig. 10.

Proposed mechanism of the antiproliferative effect of adiponectin on colon cancer cells. In colon cancer cells, adiponectin binds to AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 and activates AMPK. Activation of AMPK with adiponectin results in up-regulation of p21 and p27 expression, leading to the decrease of cyclin E, which is required for the transition from G1 to S phase. On the other hand, adiponectin in colon cancer cells potentially stimulates AMPK activity to promote lipid β-oxidation and to suppress lipogenic gene expression for cell proliferation. Furthermore, adiponectin induces apoptosis through activation of proapoptotic genes such as Bax in colon cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

ComC was obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Propodium iodide was provided by Sigma (St. Louis, MO). As we previously reported ( 60), we obtained functional adiponectin in the form of high molecular weight complex from mammalian cells. Briefly, we used conditioned media from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells overexpressing full-length adiponectin. CHO cells were transfected with a plasmid vector expressing myc-His-tagged mouse adiponectin or backbone vector (pcDNA3.1-myc-His) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 24 h of transfection, CHO cells were split and incubated for an additional 24 h in MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). We then collected the conditioned media. The concentration of adiponectin was quantified, and the formation of multimers was confirmed by Western blotting. siRNA duplexes were designed and purchased from Genepharma (Shanghai, China). The sequences are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Cell culture and tissue sampling

HCT116, HT29, LoVo, HEK293, and CHO cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). RWPE1 cells were a kind gift from Dr. Sung Hee Baek (Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea). Each cell line was maintained in medium as follows: HT29, DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS; HCT116 and LoVo, RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS; HEK293, DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum; RWPE1, keratinocyte-serum-free medium supplemented with 5 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor and 0.05 mg/ml bovine pituitary extract (Invitrogen); and CHO cells, MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. All the cell lines were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 C. Biopsy specimens were obtained from patients with colorectal cancer during colonoscopic examination between August, 2003 and July, 2004. Two biopsy specimens of representative samples of the carcinoma and macroscopically normal mucosa, respectively, were frozen and stored at −70 C until mRNA extraction. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and subjected to cDNA synthesis using RevertAid M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD). Relative amounts of mRNA were measured using the MyIQ quantitative real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) and calculated by normalization to the level of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA. The primer sequences that were used for quantitative real-time PCR analyses are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed with TGN buffer (150 mmol/liter NaCl; 50 mmol/liter Tris, pH 7.5; 0.2% Nonidet P40; 1 mmol/liter phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 100 mmol/liter NaF; 1 mmol/liter Na3VO4; 10 μg/ml aprotinin; 2 μg/ml pepstatin A; and 10 μg/ml leupeptin). Proteins were separated by electrophoresis on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA). After transfer, the membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk and probed with primary antibodies. Antibodies against GAPDH (AbFrontier, Anyang-si, Korea), adiponectin, AMPK, p-AMPK, α-Myc, p-ACC (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), cyclin E, cyclin A, CDK2, PARP-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), ACC, AMPK-α1, AMPK-α2 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY), and p27 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were used. The p53, p21, and cyclin D antibodies were kindly donated by Dr. Deog Su Hwang (Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea). The results were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and enhanced chemiluminescence.

Transient transfection

pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Adiponectin, pcDNA-myc-DN-AMPK-α1, pcDNA-myc-DN-AMPK-α2, and siRNAs (20 μm) were delivered using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in HCT116. HEK293 cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate method. Cells were split 24 h after transfection and incubated for an additional 24 h.

Cell count

Harvested cells were washed with 1× PBS and mixed with trypan blue dye, and the number of viable cells was determined manually using a hematocytometer.

Cell cycle analysis

HCT116 and HEK293 cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated BrdU antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and analyzed by flow cytometry using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

Detection of apoptosis by flow cytometry

HCT116 and HEK293 cells were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated Annexin-V antibody (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and cells were analyzed by FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences).

Soft agar colony formation assay

Base layers (4 ml) of RPMI containing 0.6% Difco Noble agar (BD Biosciences) were set in 60-mm culture dishes. Then, this was overlaid with 1.5 ml of a second layer of the conditioned media and agar containing a suspension of 1000 single cells. After 14 d, we counted the numbers of colonies and measured the diameter of each colony in 11 independent fields as described in previous reports ( 61, 62).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. David Carling (MRC Clinical Science Centre), Toshimasa Yamauchi (University of Tokyo), Massimo Loda (Harvard Medical School), Yong-Keun Jung (Seoul National University), and Hyunsook Lee (Seoul National University) for sharing materials and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the Stem Cell Research Center of the First Century Frontier Research Program (SC-3230), the National Research Foundation grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (2009-0091913), the Research Center for Functional Cellulomics of Science Research Center Program (2010-0001492), and World Class University project (R31-2009-000-100320). A.Y.K. and J.H.L. were supported by a BK21 Research Fellowship from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. Y.S.L. was supported by MEST (2009-0094022).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online May 5, 2010

Abbreviations: ACC, Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; CKI, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor; ComC, Compound C; DN, dominant negative; FAS, fatty acid synthase; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HEK, human embryonic kidney; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SREBP, sterol-regulatory element-binding protein.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ2008. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 58:71–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chao A, Thun MJ, Connell CJ, McCullough ML, Jacobs EJ, Flanders WD, Rodriguez C, Sinha R, Calle EE2005. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA 293:172–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P1995. Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 269:546–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer PE2001. The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med 7:947–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fruebis J, Tsao TS, Javorschi S, Ebbets-Reed D, Erickson MR, Yen FT, Bihain BE, Lodish HF2001. Proteolytic cleavage product of 30-kDa adipocyte complement-related protein increases fatty acid oxidation in muscle and causes weight loss in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:2005–2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF1995. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J Biol Chem 270:26746–26749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu E, Liang P, Spiegelman BM1996. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J Biol Chem 271:10697–10703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, Hotta K, Shimomura I, Nakamura T, Miyaoka K, Kuriyama H, Nishida M, Yamashita S, Okubo K, Matsubara K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y1999. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257:79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Ito Y, Tsuchida A, Yokomizo T, Kita S, Sugiyama T, Miyagishi M, Hara K, Tsunoda M, Murakami K, Ohteki T, Uchida S, Takekawa S, Waki H, Tsuno NH, Shibata Y, Terauchi Y, Froguel P, Tobe K, Koyasu S, Taira K, Kitamura T, Shimizu T, Nagai R, Kadowaki T2003. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature 423:762–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, Yamashita S, Noda M, Kita S, Ueki K, Eto K, Akanuma Y, Froguel P, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Carling D, Kimura S, Nagai R, Kahn BB, Kadowaki T2002. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med 8:1288–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubota N, Yano W, Kubota T, Yamauchi T, Itoh S, Kumagai H, Kozono H, Takamoto I, Okamoto S, Shiuchi T, Suzuki R, Satoh H, Tsuchida A, Moroi M, Sugi K, Noda T, Ebinuma H, Ueta Y, Kondo T, Araki E, Ezaki O, Nagai R, Tobe K, Terauchi Y, Ueki K, Minokoshi Y, Kadowaki T2007. Adiponectin stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. Cell Metab 6:55–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamauchi T, Nio Y, Maki T, Kobayashi M, Takazawa T, Iwabu M, Okada-Iwabu M, Kawamoto S, Kubota N, Kubota T, Ito Y, Kamon J, Tsuchida A, Kumagai K, Kozono H, Hada Y, Ogata H, Tokuyama K, Tsunoda M, Ide T, Murakami K, Awazawa M, Takamoto I, Froguel P, Hara K, Tobe K, Nagai R, Ueki K, Kadowaki T2007. Targeted disruption of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 causes abrogation of adiponectin binding and metabolic actions. Nat Med 13:332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen DC, Chung YF, Yeh YT, Chaung HC, Kuo FC, Fu OY, Chen HY, Hou MF, Yuan SS2006. Serum adiponectin and leptin levels in Taiwanese breast cancer patients. Cancer Lett 237:109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goktas S, Yilmaz MI, Caglar K, Sonmez A, Kilic S, Bedir S2005. Prostate cancer and adiponectin. Urology 65:1168–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petridou E, Mantzoros C, Dessypris N, Koukoulomatis P, Addy C, Voulgaris Z, Chrousos G, Trichopoulos D2003. Plasma adiponectin concentrations in relation to endometrial cancer: a case-control study in Greece. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:993–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa M, Kitayama J, Kazama S, Hiramatsu T, Hatano K, Nagawa H2005. Plasma adiponectin and gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11:466–472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaklamani VG, Sadim M, Hsi A, Offit K, Oddoux C, Ostrer H, Ahsan H, Pasche B, Mantzoros C2008. Variants of the adiponectin and adiponectin receptor 1 genes and breast cancer risk. Cancer Res 68:3178–3184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang JH, Lee YY, Yu BY, Yang BS, Cho KH, Yoon DK, Roh YK2005. Adiponectin induces growth arrest and apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell. Arch Pharm Res 28:1263–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Lam JB, Lam KS, Liu J, Lam MC, Hoo RL, Wu D, Cooper GJ, Xu A2006. Adiponectin modulates the glycogen synthase kinase-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway and attenuates mammary tumorigenesis of MDA-MB-231 cells in nude mice. Cancer Res 66:11462–11470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dieudonne MN, Bussiere M, Dos Santos E, Leneveu MC, Giudicelli Y, Pecquery R2006. Adiponectin mediates antiproliferative and apoptotic responses in human MCF7 breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 345:271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bub JD, Miyazaki T, Iwamoto Y2006. Adiponectin as a growth inhibitor in prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 340:1158–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cong L, Gasser J, Zhao J, Yang B, Li F, Zhao AZ2007. Human adiponectin inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in human endometrial carcinoma cells, HEC-1-A and RL95 2. Endocr Relat Cancer 14:713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishikawa M, Kitayama J, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T, Maki T, Miyato H, Yamashita H, Nagawa H2007. Adiponectin inhibits the growth and peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer through its specific membrane receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2. Cancer Sci 98:1120–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei EK, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Mantzoros CS2005. Low plasma adiponectin levels and risk of colorectal cancer in men: a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:1688–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukumoto J, Otake T, Tajima O, Tabata S, Abe H, Mizoue T, Ohnaka K, Kono S2008. Adiponectin and colorectal adenomas: Self Defense Forces Health Study. Cancer Sci 99:781–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otake S, Takeda H, Suzuki Y, Fukui T, Watanabe S, Ishihama K, Saito T, Togashi H, Nakamura T, Matsuzawa Y, Kawata S2005. Association of visceral fat accumulation and plasma adiponectin with colorectal adenoma: evidence for participation of insulin resistance. Clin Cancer Res 11:3642–3646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erarslan E, Turkay C, Koktener A, Koca C, Uz B, Bavbek N2009. Association of visceral fat accumulation and adiponectin levels with colorectal neoplasia. Dig Dis Sci 54:862–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaklamani VG, Wisinski KB, Sadim M, Gulden C, Do A, Offit K, Baron JA, Ahsan H, Mantzoros C, Pasche B2008. Variants of the adiponectin (ADIPOQ) and adiponectin receptor 1 (ADIPOR1) genes and colorectal cancer risk. JAMA 300:1523–1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujisawa T, Endo H, Tomimoto A, Sugiyama M, Takahashi H, Saito S, Inamori M, Nakajima N, Watanabe M, Kubota N, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T, Wada K, Nakagama H, Nakajima A2008. Adiponectin suppresses colorectal carcinogenesis under the high-fat diet condition. Gut 57:1531–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishihara T, Baba M, Matsuda M, Inoue M, Nishizawa Y, Fukuhara A, Araki H, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Tamura S, Hayashi N, Iishi H, Shimomura I2008. Adiponectin deficiency enhances colorectal carcinogenesis and liver tumor formation induced by azoxymethane in mice. World J Gastroenterol 14: 6473–6480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Yang YA, Morin PJ, Han WF, Chen T, Bornman DM, Gabrielson EW, Pizer ES2003. Regulation of fatty acid synthase expression in breast cancer by sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c. Exp Cell Res 282:132–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chuu CP, Hiipakka RA, Kokontis JM, Fukuchi J, Chen RY, Liao S2006. Inhibition of tumor growth and progression of LNCaP prostate cancer cells in athymic mice by androgen and liver X receptor agonist. Cancer Res 66:6482–6486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li JN, Mahmoud MA, Han WF, Ripple M, Pizer ES2000. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 participates in the regulation of fatty acid synthase expression in colorectal neoplasia. Exp Cell Res 261:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alo' PL, Visca P, Marci A, Mangoni A, Botti C, Di Tondo U1996. Expression of fatty acid synthase (FAS) as a predictor of recurrence in stage I breast carcinoma patients. Cancer 77:474–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein JI, Carmichael M, Partin AW1995. OA-519 (fatty acid synthase) as an independent predictor of pathologic state in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Urology 45:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, Musi N, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Moller DE2001. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest 108:1167–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salt IP, Johnson G, Ashcroft SJ, Hardie DG1998. AMP-activated protein kinase is activated by low glucose in cell lines derived from pancreatic β cells, and may regulate insulin release. Biochem J 335 (Pt 3):533–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Carlson CL, Winder WW1999. Liver AMP-activated protein kinase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase during and after exercise. J Appl Physiol 86:669–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rattan R, Giri S, Singh AK, Singh I2005. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside inhibits cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo via AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 280:39582–39593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiang X, Saha AK, Wen R, Ruderman NB, Luo Z2004. AMP-activated protein kinase activators can inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cells by multiple mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321:161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imamura K, Ogura T, Kishimoto A, Kaminishi M, Esumi H2001. Cell cycle regulation via p53 phosphorylation by a 5′-AMP activated protein kinase activator, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside, in a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 287:562–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugiyama M, Takahashi H, Hosono K, Endo H, Kato S, Yoneda K, Nozaki Y, Fujita K, Yoneda M, Wada K, Nakagama H, Nakajima A2009. Adiponectin inhibits colorectal cancer cell growth through the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Int J Oncol 34:339–344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackowski S, Wang J, Baburina I2000. Activity of the phosphatidylcholine biosynthetic pathway modulates the distribution of fatty acids into glycerolipids in proliferating cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1483:301–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pizer ES, Lax SF, Kuhajda FP, Pasternack GR, Kurman RJ1998. Fatty acid synthase expression in endometrial carcinoma: correlation with cell proliferation and hormone receptors. Cancer 83:528–537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rashid A, Pizer ES, Moga M, Milgraum LZ, Zahurak M, Pasternack GR, Kuhajda FP, Hamilton SR1997. Elevated expression of fatty acid synthase and fatty acid synthetic activity in colorectal neoplasia. Am J Pathol 150:201–208 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pizer ES, Wood FD, Heine HS, Romantsev FE, Pasternack GR, Kuhajda FP1996. Inhibition of fatty acid synthesis delays disease progression in a xenograft model of ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 56:1189–1193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pizer ES, Wood FD, Pasternack GR, Kuhajda FP1996. Fatty acid synthase (FAS): a target for cytotoxic antimetabolites in HL60 promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cancer Res 56:745–751 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furuya Y, Akimoto S, Yasuda K, Ito H1997. Apoptosis of androgen-independent prostate cell line induced by inhibition of fatty acid synthesis. Anticancer Res 17:4589–4593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JB, Sarraf P, Wright M, Yao KM, Mueller E, Solanes G, Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM1998. Nutritional and insulin regulation of fatty acid synthetase and leptin gene expression through ADD1/SREBP1. J Clin Invest 101:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopez JM, Bennett MK, Sanchez HB, Rosenfeld JM, Osborne TF1996. Sterol regulation of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase: a mechanism for coordinate control of cellular lipid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:1049–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabor DE, Kim JB, Spiegelman BM, Edwards PA1998. Transcriptional activation of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase 2 gene by sterol regulatory element-binding protein/adipocyte determination and differentiation factor 1. J Biol Chem 273:22052–22058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shklyaev S, Aslanidi G, Tennant M, Prima V, Kohlbrenner E, Kroutov V, Campbell-Thompson M, Crawford J, Shek EW, Scarpace PJ, Zolotukhin S2003. Sustained peripheral expression of transgene adiponectin offsets the development of diet-induced obesity in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:14217–14222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viollet B, Guigas B, Leclerc J, Hebrard S, Lantier L, Mounier R, Andreelli F, Foretz M2009. AMP-activated protein kinase in the regulation of hepatic energy metabolism: from physiology to therapeutic perspectives. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 196:81–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams CJ, Mitsiades N, Sozopoulos E, Hsi A, Wolk A, Nifli AP, Tseleni-Balafouta S, Mantzoros CS2008. Adiponectin receptor expression is elevated in colorectal carcinomas but not in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer 15:289–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lukanova A, Söderberg S, Kaaks R, Jellum E, Stattin P2006. Serum adiponectin is not associated with risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15:401–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ealey KN, Archer MC2009. Elevated circulating adiponectin and elevated insulin sensitivity in adiponectin transgenic mice are not associated with reduced susceptibility to colon carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer 124:2226–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumor A, Daniel P, Pietruczuk M, Malecka-Panas E2009. Serum leptin, adiponectin, and resistin concentration in colorectal adenoma and carcinoma (CC) patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 24:275–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pechlivanis S, Bermejo JL, Pardini B, Naccarati A, Vodickova L, Novotny J, Hemminki K, Vodicka P, Försti A2009. Genetic variation in adipokine genes and risk of colorectal cancer. Eur J Endocrinol 160:933–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zakikhani M, Dowling RJ, Sonenberg N, Pollak MN2008. The effects of adiponectin and metformin on prostate and colon neoplasia involve activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 1:369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoon MJ, Lee GY, Chung JJ, Ahn YH, Hong SH, Kim JB2006. Adiponectin increases fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle cells by sequential activation of AMP-activated protein kinase, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α. Diabetes 55:2562–2570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cifone MA, Fidler IJ1980. Correlation of patterns of anchorage-independent growth with in vivo behavior of cells from a murine fibrosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77:1039–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lewis JD, Payton LA, Whitford JG, Byrne JA, Smith DI, Yang L, Bright RK2007. Induction of tumorigenesis and metastasis by the murine orthologue of tumor protein D52. Mol Cancer Res 5:133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]