Abstract

Early adolescence is a dynamic period for the development of alcohol appraisals (expected outcomes of drinking and subjective evaluations of expected outcomes), yet the literature provides a limited understanding of psychosocial factors that shape these appraisals during this period. This study took a comprehensive view of alcohol appraisals and considered positive and negative alcohol outcome expectancies, as well as subjective evaluations of expected outcomes. Developmental-ecological theory guided examination of individual, peer, family, and neighborhood predictors of cognitive appraisals of alcohol and use. A community sample of 378 adolescents (mean age 11.5 years at Wave 1, 52% female) was assessed annually for 4 years. Longitudinal path analysis suggested that the most robust predictors of alcohol appraisals were peer norms. Furthermore, perceived likelihood of positive and negative alcohol outcomes prospectively predicted increases in drinking. There was limited support for appraisals operating as mediators of psychosocial risk and protective factors.

Cognitive appraisals of alcohol use include expected outcomes of alcohol use, as well as subjective evaluations of these expected outcomes. Such appraisals develop prior to initiation of drinking, and robustly correlate with initiation, escalation, and maintenance of drinking (e.g., Bekman, Goldman, Worley, & Anderson, 2011; Goldman, Del Boca, & Darkes, 1999; Jester et al., 2015; Zucker, Kincaid, Fitzgerald, & Bingham, 1995). Psychosocial factors that might influence the development of cognitive appraisals of alcohol are of interest because knowledge of these factors may help inform potential targets for preventive interventions. The goal of the current study was to test psychosocial predictors of positive and negative outcome expectancies as well as subjective evaluations of these expected outcomes in a sample of early adolescents in the early stage of alcohol use. We also tested whether alcohol appraisals mediated the association between psychosocial variables and early alcohol use, and potential reciprocal associations between alcohol use and appraisals.

Although there is considerable evidence that cognitive appraisals of alcohol change during early and middle adolescence (e.g., Colder et al., 2014; Goldberg, Halpern-Felsher, & Millstein, 2002; Miller, Smith, & Goldman, 1990), the extant literature provides a limited understanding of the psychosocial factors that shape these appraisals. Much of the prior research on adolescent alcohol appraisals has focused on positive expectancies (perceived likelihood of positive outcomes from drinking). This work suggests that parental and peer alcohol use, perceived parental approval of drinking, exposure to alcohol outlets in the community, alcohol use, behavioral approach, and sensation seeking all influence positive alcohol expectancies (e.g., Cumsille, Sayer, & Graham, 2000; Gunn & Smith, 2010; Lopez-Vergara et al., 2012; Martino, Collins, Ellickson, Schell, & McCaffrey, 2006; Settles, Zapolski, & Smith, 2014; Zamboanga, Schwartz, Ham, Jarvis, & Olthuis, 2009). However, few studies have considered the development of negative expectancies (perceived likelihood of negative outcomes from drinking) (see Lopez-Vergara et al., 2012 and Donovan, Molina, & Kelly, 2009 for exceptions). This is a notable gap in the literature, as negative expectancies are especially important in shaping alcohol attitudes, particularly in early adolescence (Beckman et al., 2011; Cameron, Stritzke, & Durkin, 2003; O’Connor et al., 2007).

In addition to positive and negative expectancies, the subjective evaluation or value placed on an expected outcome also influences drinking behavior (e.g., Fromme & D’Amico, 2000; Fromme, Marlatt, Baer, & Kivlahan, 1994; Neighbors, Walker, & Larimer, 2003). An outcome perceived as highly likely may have little impact on use if it is not considered important or desirable. Likewise, even an outcome that has a low perceived likelihood of occurrence may be behaviorally impactful if it is highly valued. Subjective evaluations of outcomes and factors contributing to their development have been overlooked in the extant literature on early adolescent alcohol use. An exception is Zamboanga et al. (2009) who found that peer approval/use of alcohol was associated with the value placed on positive expectancies. Other influences relevant to the development of subjective evaluations (e.g., parents, community, and personality) have not been examined.

In summary, the literature on factors influencing early alcohol appraisals has been sparse and exceedingly narrow. It has focused almost exclusively on positive expectancies without much consideration for negative expectancies or subjective evaluations. The current study addresses these gaps in the literature using a sample of early adolescents.

In early adolescence prior to extensive direct experience with alcohol, interactions with the social environment are presumably dominant influences on how adolescents think about alcohol. Accordingly, we focus on socio-environmental and individual level factors that might shape alcohol appraisals before use experiences began to appreciably impact the formation of alcohol appraisals. We grounded our examination of these psychosocial factors in developmental ecological theory, which emphasizes the influence of multiple, interdependent environmental systems or “ecologies” on child development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Evidence supports this perspective as applied to adolescent substance use in that characteristics of the adolescent (individual level) along with multiple contextual levels of the social environment (peers, family, and community) have been found to be important risk and protective factors (Chassin, Hussong, & Beltran, 2009; Haegerich & Tolan, 2008). Considering multiple sources of influence can yield a more complete understanding of adolescent alcohol use (Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003). Accordingly, we consider individual level (personality/temperament) and social contextual factors (peers, family, and community) as potential predictors of alcohol appraisals. Though our overarching framework in this investigation is developmental-ecological theory, we also borrow from Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory to inform our conceptualization of temperamental/personality influences on substance involvement. We outline this conceptualization and how it informed the present study below.

Individual-Level Influences

Personality/Temperament

A person’s personality/temperament is considered part of the individual system of influences according to developmental ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST; Gray & McNaughton, 2000) posits three systems that may bias individuals toward focusing on reward- or punishment-related information regarding outcomes of alcohol use, thus influencing the development and evaluation of outcome expectancies (Simons, Dvorak, & Lao-Barrocco, 2009). These systems include a Behavioral Approach System (referred to as behavioral approach herein) that mediates reactions to appetitive stimuli, a Fight-Flight-or-Freeze System (referred to fight-flight herein) that mediates responses to aversive stimuli, and a Behavioral Inhibition System (referred to as behavioral inhibition herein) that inhibits behavior, and increases arousal and risk assessment in response to uncertainty and goal conflict (Gray & McNaughton, 2000).

In a cross-sectional analysis with this sample, we examined associations between behavioral approach, fight-flight, and behavioral inhibition with alcohol expectancies (Lopez-Vergara et al., 2012). Our hypotheses are based on these findings. We found that a strong behavioral approach was associated with high positive expectancies as predicted from RST. Behavioral approach was also associated with high negative expectancies. We speculated that this may be attributable to strong behavioral approach being associated with risky drinking patterns (O’Connor & Colder, 2005) and perhaps some experience with negative consequences. However, drinking mediated by behavioral approach is not necessarily curtailed by the experience of aversive consequences. Accordingly, in the present study, we expected that strong behavioral approach would predict increases in positive and negative expectancies, and more positive evaluations (or less negative evaluations) of these outcomes. Although RST might suggest that fight-flight is linked to negative expectancies because this system mediates reactivity to aversive stimuli, our prior work did not yield support for this link. It is possible that in our longitudinal study, as youth accumulate more drinking experience over time, they may experience some negative consequences of alcohol use (either directly or indirectly). This leads us to expect a positive association between the fight-flight and negative expectancies and more negative evaluations of these outcomes. Findings from our prior cross-sectional analysis suggested no links between behavioral inhibition and positive and negative expectancies. Accordingly, we expected no relationship between behavioral inhibition and alcohol appraisals in our longitudinal study. Similarly, we found no cross-sectional evidence for an association between impulsivity/fun seeking (a dimension typically viewed as a facet of behavioral approach) and alcohol appraisals. The lack of association is consistent with work that has distinguished “rash impulsiveness” from reward sensitivity, with only the latter operating on use through appraisals (Dawe, Gullo, & Loxton, 2004; Magid, MacLean, & Colder, 2007). Our impulsivity/fun seeking measure may reflect “rash impulsiveness” and thus it would be expected to be related to drinking, but not necessarily alcohol appraisals.

Alcohol use

The developmental ecological framework posits that past experiences contribute to attitudes and behavior (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Thus, we also expected that prior alcohol use would shape alcohol appraisals (Del Boca, Darkes, Goldman & Smith., 2002), such that alcohol use would predict increases in positive expectancies, decreases in negative expectancies, and more positive (or less negative) evaluations of both outcomes (Goldberg et al., 2002; Settles et al., 2014; Wardell & Read, 2013).

Socio-environmental-Level Influences

Peers

Affiliation with peers who engage in alcohol is associated with positive expectancies (e.g., Cumsille et al., 2000; Martino et al., 2006; Ouellette, Gerrard, Gibbons, & Reis-Bergan, 1999; Zamboanga et al., 2009). Accordingly, we hypothesized that peer alcohol use would prospectively predict increases in positive expectancies, as well as positive evaluations of these expected outcomes. Most youth rarely experience negative consequences from early drinking episodes (Goldberg et al., 2002), and to the degree that this is observed or inferred from peers, high levels of peer alcohol use might be expected to predict declines in negative expectancies and less negative evaluations of expected outcomes.

Parents

A large body of prior work (e.g., Cumsille et al., 2000; Martino et al., 2006) has consistently demonstrated that high levels of parental drinking are associated with positive attitudes toward drinking. Yet findings regarding parental use and adolescent negative expectancies have been far more equivocal (Donovan et al., 2009).In addition to parental drinking, alcohol specific parenting may be another way that parents influence the formation of adolescent alcohol appraisals. As frequent parental negative messages about drinking are associated with low likelihood of drinking itself (Napper, Hummer, Lac, & Labrie, 2014; Zehe & Colder, 2014), one would expect that such messages, and parental negative reactions to adolescent drinking (e.g., taking away privileges) to predict later increases in negative expectancies and more negative evaluations of expected outcomes. Yet the ways in which parents may influence adolescent evaluations of drinking when multiple aspects of parental influence are considered is unclear. The delineation of these complex influences was one of the objectives of the present study.

Neighborhood

Another important feature of an adolescent’s developmental context is the community. Community characteristics influence children’s psychological adjustment, including alcohol use (e.g., Fleming, Thorson, & Atkin, 2004; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Jessor, 1993; Trucco, Colder, Wieczorek, Lengua, & Hawk, 2014). Yet the role of these influences on adolescent alcohol appraisals has received very little attention. Community influences, such as community norms and density of alcohol outlets, may operate through proscriptive norms. Proscriptive norms represent unwritten rules about the acceptability of behaviors (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2003), and favorable attitudes about youth drinking in the community and high density of alcohol outlets likely convey tacit approval of drinking. Thus, these community characteristics may promote positive alcohol expectancies and favorable subjective evaluations of positive outcomes.

The Current Study: Summary and Hypotheses

Although prior work has established alcohol appraisals as an important determinant of adolescent alcohol use, the literature examining how alcohol appraisals develops has been exceedingly narrow. In the current study, we sought to examine a theoretically informed and comprehensive integrated model of individual and environmental level influences on the development of alcohol appraisals. We consider both positive and negative outcome expectancies as well as subjective evaluations of these outcomes. Table 1 presents a summary of our hypotheses. These hypotheses are based on theory and prior research (including or own cross-sectional work examining RST) as reviewed above to provide insights into the development of alcohol appraisals during early and middle adolescence during a period of alcohol use initiation and experimentation.

Table 1.

Hypothesized Prospective Associations

| Predictors | Dependent Variable

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use | Positive Outcome | Negative Outcome | |||

|

| |||||

| Likelihood | Evaluation | Likelihood | Evaluation | ||

| Personality | |||||

| Behavioral Approach (Drive) | + | + | + | + | + |

| Impulsivity/Fun Seeking | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Behavioral Inhibition (Anxiety) | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fight-Flight (Fear/Shyness) | + | 0 | 0 | + | + |

| Peers | |||||

| Perceived Peer Use | + | + | + | − | + |

| Parenting | |||||

| Parental Drinking | + | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| Health Messages | − | 0 | 0 | + | − |

| Reactions to Drinking | − | 0 | 0 | + | − |

| Neighborhood | |||||

| Alcohol Outlets | + | + | + | − | − |

| Residents’ Approval | + | + | + | − | − |

Note. + positive association; − negative association; 0 no association.

Method

Sample

The community sample was recruited from Erie County NY via random digit dialing. A full description of recruitment can be found in our prior work (Lopez-Vergara et al., 2012; O’Connor, Lopez-Vergara, & Colder, 2012). In brief, eligibility criteria for recruitment included an English-speaking child between the ages of 10 and 12 years without any physical impairments or cognitive deficits that would preclude completion of the interview and a caregiver willing to participate. Recruitment began in April 2007 and was completed in February 2009. One child per household was recruited.

The final sample included 378 families. Children were assessed annually over four years. The average adolescent age at each assessment was 11.6 (SD = .88), 12.6 (SD = .89), 13.6 (SD = .90), and 14.9 (SD=.90) years old at Waves 1–4 (W1–W4), respectively. The sample was approximately evenly split on gender (52% female). In terms of race/ethnicity, the majority of adolescents were White (76%), 15% were Black/African-American, 3% were Hispanic/Latino, 2% were Asian/Pacific Islander, and the remaining 4% were another race/ethnicity (mostly of mixed background). Additional sample demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | Sample (N=378) |

|---|---|

| Child Gender (% Female) | 52% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 76% |

| Black or African-American | 15% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2% |

| Other | 4% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3% |

| Family Structure | |

| % Married-couple Family | 72% |

| % Male householder | 3% |

| % Female householder | 25% |

| Parental Education | |

| % < HS | 3% |

| % HS graduate | 12% |

| % 2 year or some College | 27% |

| % College Graduate | 41% |

| % Graduate or Professional | 17% |

| Median Family Income | $60,000 ($0–$250,000) |

| % receiving public assistance income | 7% |

Procedure

W1, W2, and W3 interviews were conducted at our university research offices. W4 consisted of a brief telephone administered audio-computer assisted self-interview (CASI) completed by the adolescent that assessed alcohol and drug use only. All study procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board (IRB) before the study began.

W1–W3

After completing the consent (caregiver; typically the mother, 82%-83% across waves) and assent (adolescent) procedures, the adolescent and caregiver were assessed in separate rooms. All adolescent and caregiver questionnaires were read aloud and responses were entered directly into a computer. Questions deemed “sensitive” (i.e., questions assessing substance use) were read aloud by the interviewer, but inputted directly into the computer by the adolescent. Most follow-up assessments were done within ± 2 months of the anniversary of the prior assessment (90%). The same interview procedures were used for W1–W3. Families were compensated $75, $85, and $100 at W1–W3, respectively.

W4

Adolescents received a $15 gift card to local merchant for audio-CASI completion.

Measures

Alcohol use (W1–W4)

A quantity x frequency index was computed to represent total number of drinks consumed in the past year using items from the National Survey of Youth Survey (Elliott & Huizinga, 1983). Adolescents were asked if they drank alcohol without parental permission, and then they were presented with two fill-in-the-blank items asking the number of times in the past year they drank and the typical number of drinks consumed per drinking occasion. Alcohol use without parental permission was assessed because drinking with parental permission at the ages of our assessments typically occurs with parental supervision in highly structured settings, such as family celebrations and religious ceremonies (Donovan & Molina, 2008). Accordingly, alcohol use with parental permission for early adolescents represents a different phenomenon than drinking without parental permission. The quantity x frequency (QF) index was skewed (Skew = 5 to 15 across W1–W4) and was log-transformed, which reduced skew (2 to 7).

Alcohol use appraisal variables (W1–W3)

Expectancies (Likelihood ratings)

Alcohol expectancies were assessed using a measure developed by O’Connor et al. (2007) for youth with limited drinking experience. Adolescents reported perceived likelihood of positive (10 items; e.g., have more fun with my friends, feel happy, feel more relaxed and less nervous) and negative (10 items; e.g., get sick, get into trouble with the law, feel out of control) outcomes using an 11-point response scale (1 = 0% no chance to 11 = 100% for sure). The mean of the items was used to form positive and negative expectancy scale scores at each assessment (α = .87–.92).

Subjective Evaluations

Expectancy items were repeated and adolescents provided subjective evaluations of each item using a 5-point response scale (1 = very bad to 5 = very good). Items were averaged to form scale scores for positive and negative outcomes (α = .87–.96). Prior work with this sample found that expectancies and subjective evaluations were moderately correlated (Colder et al., 2014).

Personality/Temperament (W1–W3)

Caregivers rated the adolescent’s reinforcement sensitivity with the Sensitivity to Punishment - Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire for Children-Revised (SPSRQ-CR, Colder & O’Connor, 2004; Colder et al., 2011) using a five-point response scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Caregivers provide a useful perspective on the temperament of children because they see a wide range of behavior across multiple contexts (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). The SPSRQ-CR includes a behavioral inhibition (anxiety) scale (α=.65–.66), a fight-flight (fear/shyness) scale (α=.83–.84), a behavioral approach (drive) scale (α=.70–.72), and an impulsivity/fun seeking scale (α=.71–.72). Items were averaged to form scale scores.

Peer norms (W1–W3)

Adolescents reported perceived peer norms using three items from Johnston, O’Malley, and Bachman (2003) and a six-point scale (1 = none to 6 = all). Items asked about friends drinking alcohol occasionally, drinking alcohol regularly, and having five or more drinks in one sitting. Items were averaged at each assessment (α=.86 to .88).

Parents (W1–W3)

We considered two domains of parental predictors, including parent alcohol use and alcohol specific parenting.

The participating caregiver reported on his/her own alcohol use and the use of his/her spouse, romantic partner, or significant other if that person was involved in regular care of the child (80% of the sample). Most of these individuals were spouses (96%), and accordingly, from herein we use the term spouse. Caregivers reported on their own alcohol use via the Timeline Followback Interview (Sobell & Sobell, 1995), and on their spouse’s drinking using the Collateral Interview Form (Miller & Marlatt, 1987). Typical number of drinks per week in the past year was calculated for both caregiver and spouse, and the higher of these two indices was used for analysis.

Items assessing alcohol-specific parental discipline and communication were adapted from Kodl and Mermelstein’s (2004) measure of cigarette use-specific parenting and modified for alcohol. Principal components and confirmatory analyses supported two dimensions of alcohol-specific parenting, and suggested that the factor structure was invariant across the three assessments (Zehe & Colder, 2014). Three caregiver-reported items assessed parental discipline in response to adolescent drinking (e.g., take privileges away, grounding him/her) and eight adolescent-reported items assessed health risks of alcohol use that parents communicated to adolescents (e.g., “Drinking alcohol can give you a hangover” and “Alcohol is addictive”). Items were averaged to form scale scores (α = .89 to .90).

Neighborhood variables (W1)

We considered two community risk factors, alcohol outlet density and residents’ approval of youth alcohol use. The place of residence was very stable in this sample; 89% remained in the same census tract throughout waves 1–4. Given this stability, neighborhood variables from Wave 1 were used in analysis.

Alcohol outlet data were obtained from the State of New York Liquor Authority, and outlet locations were geocoded to geographic coordinates based on street addresses. Each geocoded address was assigned a census tract identifier. Alcohol outlets (only off-premise outlets such as convenience stores, supermarkets, and liquor stores) were aggregated to obtain counts for each tract. These counts were transformed into rates per tract representing the number of outlets per 100 miles of road.

Parents rated the degree to which adult neighborhood residents approved of youth drinking with an item adapted from Costa et al. (2005). The item, “How do you think most adults in your neighborhood feel about teenagers drinking alcohol?” was rated on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disapprove to 5 = strongly approve).

Demographic control variables

Community socioeconomic disadvantage was assessed using census tract data and was included as a statistical control variable when testing our neighborhood variables. Respondent domicile street addresses were geocoded to geographic coordinates using a geographic information system (GIS) that utilized census address files. Census 2000 data at the census tract level were then associated with the individual-level data for each respondent. A composite index was derived from a principal components analysis using the following variables: proportion of households living below poverty, proportion of households receiving public assistance, median family income (reverse scored), female headed households living below the poverty level with children ages 0–17, and children living below the poverty level ages 0–17. Variables were standardized and summed. High scores indicate high levels of neighborhood economic disadvantage (α = .96).

Caregivers reported the adolescent’s gender and birth date. Age (computed based on date of interview and date of birth) and gender were included as statistical control variables in all models.

Results

Attrition analysis

Retention was strong with 92%, 94%, and 91% of the sample participating in W2–W4 follow-ups, respectively. Cases missing at a follow-up assessment were compared to those present at all four assessments on demographic and W1 variables. There were no differences on demographic variables (gender, ethnicity, and family socioeconomic status), alcohol use, positive and negative expectancies, or subjective evaluations of these expectancies (all ps > .10). There were also no differences on the SPSRQ personality/temperament scales, parental health messages about drinking, neighborhood characteristics (SES, alcohol outlets, and residents’ approval of underage drinking). Adolescents missing at follow-up assessment reported higher perceived peer alcohol use, and their parents reported higher alcohol use and were less likely to provide behavioral consequences for drinking (all ps < .05), however these differences were small (all η2 < .02). In sum, rates of missing data were low and the few differences found between cases with and without complete data were small. Further, we used full-information maximum likelihood estimation, which includes cases with missing data in the analysis. Thus, missing data likely had a limited impact on our findings.

Descriptive Results

Alcohol use

As would be expected given the age of our sample, rates for alcohol use were low, though they increased as youth aged (see Table 3 for means of quantity x frequency variables). A single dichotomous item was used to assess lifetime alcohol use without parental permission (0=no, 1=yes). Rates of lifetime alcohol use without parental permission were 7%, 17%, 30%, and 33% at W1–W4, respectively. Rates of use in the past year based on the computed quantity x frequency index were (5%, 13%, 25%, 29% at W1–W4, respectively. Among drinkers, average past year frequency of consumption was 3 (SD=2.50), 4 (SD=4.75), 4 (SD=3.36), and 6 (SD=12.78) times, and average quantity of consumption was .30 (SD=.08), .50 (SD=.87), .70 (SD=.79), and 2.0 (SD=1.84) drinks per occasion at W1–W4, respectively. Our sample consists of early adolescents that are not typically examined in large epidemiological studies of adolescent alcohol use. Furthermore, we assessed drinking without parental permission. These two innovations make comparison of our rates of alcohol use to other samples somewhat challenging. We considered the Monitoring the Future (MTF) data from 2009–2011 for 8th graders and from 2011–2013 for 10th graders for comparison to our sample because these cohorts correspond most closely to when our participants were in the 8th and 10th grades. MTF found lifetime rates of alcohol use of 33%–36% for 8th graders and 52%–56% for 10th graders. Lifetime rates of alcohol use were 26% and 45% for our 8th and 10th graders, respectively. MTF found past year rates of alcohol use to be 27%–30% for 8th graders and 47%–50% for 10th graders. Past year rates among our 8th and 10th graders were, 20% and 36%, respectively. The slightly lower rates in our sample are likely attributable to MTF not distinguishing drinking with and without parental permission. King, Iacono, & McGue (2004) reported lifetime rates of alcohol use without parental permission for 11 and 14 year olds for their twin study (N=1402). Their rates were 2% and 31% for 11 and 14 year olds, respectively. These lifetime rates are comparable to those of our 11 and 14 year olds (6% and 33%, respectively). In sum, taking into account differences in ages and assessments, our rates of alcohol use are comparable to other samples, and reinforce that our study is one of the early stages of alcohol use.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables

| Variable | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Expectancies | ||

| Time 1 | 3.41 | 1.96 |

| Time 2 | 3.73 | 2.01 |

| Time 3 | 4.35 | 2.07 |

| Subjective Evaluation of Positive Expectancies | ||

| Time 1 | 2.80 | 0.98 |

| Time 2 | 2.79 | 0.94 |

| Time 3 | 2.98 | 0.96 |

| Negative Expectancies | ||

| Time 1 | 7.17 | 2.12 |

| Time 2 | 7.23 | 2.18 |

| Time 3 | 6.87 | 1.91 |

| Subjective Evaluation of Negative Expectancies | ||

| Time 1 | 1.52 | 0.57 |

| Time 2 | 1.48 | 0.53 |

| Time 3 | 1.54 | 0.56 |

| Alcohol Use | ||

| Time 1 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| Time 2 | 0.11 | 0.40 |

| Time 3 | 0.27 | 0.62 |

| Time 4 | 0.46 | 1.02 |

| Behavioral Approach (Drive) | ||

| Time 1 | 3.23 | 0.71 |

| Time 2 | 3.19 | 0.70 |

| Time 3 | 3.15 | 0.69 |

| Impulsivity/Fun-seeking | ||

| Time 1 | 2.56 | 0.65 |

| Time 2 | 2.55 | 0.65 |

| Time 3 | 2.54 | 0.63 |

| Fight-Flight (Fear/Shyness) | ||

| Time 1 | 2.66 | 0.71 |

| Time 2 | 2.63 | 0.69 |

| Time 3 | 2.61 | 0.68 |

| Behavioral Inhibition (Anxiety) | ||

| Time 1 | 3.05 | 0.72 |

| Time 2 | 2.99 | 0.68 |

| Time 3 | 2.96 | 0.61 |

| Peer Alcohol Use | ||

| Time 1 | 1.17 | 0.55 |

| Time 2 | 1.32 | 0.70 |

| Time 3 | 1.47 | 0.81 |

| Parental Alcohol Use | ||

| Time 1 | 4.66 | 7.33 |

| Time 2 | 4.99 | 7.65 |

| Time 3 | 5.02 | 7.89 |

| Parental Reaction to Alcohol Use | ||

| Time 1 | 3.19 | 0.94 |

| Time 2 | 3.10 | 0.99 |

| Time 3 | 3.11 | 0.98 |

| Parental Health Messages about Alcohol Use | ||

| Time 1 | 3.26 | 0.72 |

| Time 2 | 3.18 | 0.75 |

| Time 3 | 3.12 | 0.76 |

| Alcohol Outlets | 22.51 | 21.36 |

| Neighborhood residents’ | ||

| Approval of Alcohol Use | 1.65 | 0.68 |

| Neighborhood Poverty | 0.00 | 1.00 |

Other study variables

Means and standard deviations of study variables are presented in Table 2. Our prior work with this sample suggested that that expectancies and subjective evaluations changed across waves as expected (see Colder et al., 2014). As can be seen in Table 2, positive expectancies increase and negative expectancies decreased across waves. Furthermore, subjective evaluations of both positive and negative outcomes increased (became more positive or less negative) over time. Positive outcomes were also evaluated more positively and less likely compared to negative outcomes.

Path Models

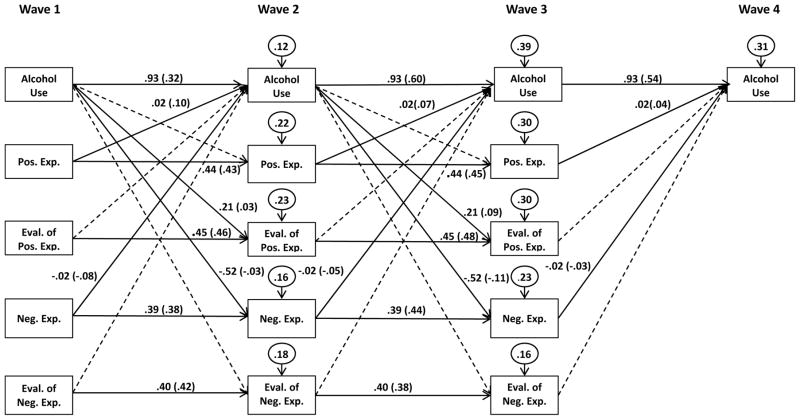

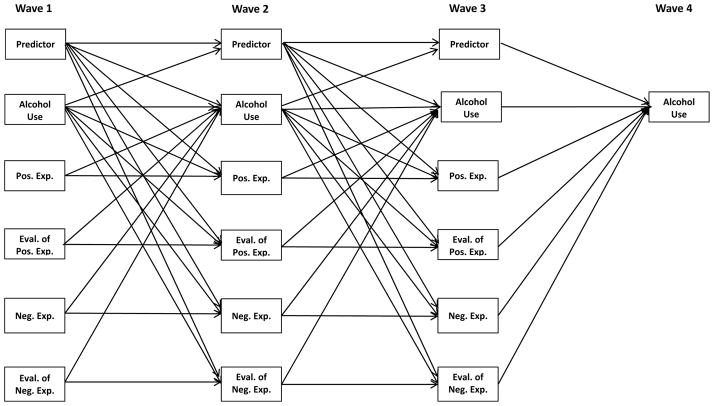

Cross-lagged path models estimated in Mplus Version 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) with maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimation were used to test our hypotheses. All variables and hypothesized pathways could not be estimated simultaneously in one model given the large number of parameters. Accordingly, separate models were estimated for each domain of predictors (e.g., individual, peer, parents, community). First, a model was estimated with positive and negative expectancies, subjective evaluations, and alcohol use (see Figure 1). Within time covariances and covariances among exogenous variables were freely estimated. Paths from age and gender to all W2–W4 variables were included as statistical controls. In subsequent models, predictor variables from each domain were added to the model (see Figure 2 for general schematic of our predictor models). In some domains reciprocal associations between predictors and alcohol use were expected (personality/temperament, peers, parenting), but in other domains they were not (e.g., neighborhood). Hence, reciprocal associations depicted in Figure 2 were not estimated in the neighborhood model. Nested tests were used to evaluate whether stability paths and cross-lagged paths were equivalent across time periods (e.g., paths from W1 to W2 equivalent to corresponding paths from W2 to W3, etc.). If nested tests suggested equivalence, then the relevant constraints were retained in the final model. This approach helped reduce the number of parameters being estimated, and provided a parsimonious model. Finally, if the pattern of statistically significant paths suggested evidence for a relevant mediation pathway (e.g., a predictor variable was prospectively associated with an alcohol appraisal variable, which in turn, predicted subsequent alcohol use), then the mediational path was tested using bootstrapped confidence intervals based on 5000 samples (MacKinnon, 2008). This approach allowed us to test fully longitudinal mediational pathways.

Figure 1.

Path model of alcohol appraisal variables and alcohol use. (Note: Solid paths are statistically significant p <.05, dashed paths are estimated, but not statistically significant. Unstandardized coefficients outside of parentheses and standardized coefficients inside parentheses. R2 is reported in disturbance terms. Pos. = positive, Neg. = negative, Exp. = expectancy. Eval. = evaluation. Paths from age and gender to endogenous variables, within time covariances among disturbances, and covariances among exogenous variables were estimated but not depicted in the figure).

Figure 2.

Conceptual path model with predictor variables.

Expectancies, subjective evaluations, and alcohol use

All nested tests suggested equivalence of the corresponding direct paths over time (W1 to W2, W2 to W3, and W3 to W4; all ps > .05), and therefore, across time equality constraints were retained in the final model. These direct paths included stability paths (e.g., W1 alcohol use to W2 alcohol use, W2 alcohol use to W3 alcohol use, and W3 alcohol use to W4 alcohol use, etc.), and cross-lagged paths (e.g., W1 positive expectancies to W2 alcohol use, W2 positive expectancies to W3 alcohol use, and W3 positive expectancies to W4 alcohol use, etc.). The final model provided an adequate fit to the data (χ2 (85) = 182.48, p < .01, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .92, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = .06). All stability paths were statistically significant (see Figure 1). In addition, high positive and low negative expectancies were associated with increases in alcohol use above and beyond prior levels of alcohol use. Subjective evaluation variables were not prospectively associated with alcohol use. Alcohol use was also associated with alcohol appraisals, such that high levels of alcohol use were associated with high subjective evaluations of positive outcomes (more positive evaluations) and decreases in negative expectancies. In sum, among the alcohol appraisal variables, positive and negative expectancies were prospectively associated with alcohol use, and therefore, these were the candidate mediators to be considered in subsequent models.

Personality/Temperament

Next, personality/temperament predictor variables were added to the model depicted in Figure 2. Direct paths from behavioral approach (drive), impulsivity/fun seeking, behavioral inhibition (anxiety), and fight-flight (fear/shyness) at a prior assessment to the alcohol appraisal variables and to alcohol use at a subsequent assessment were estimated as were stability paths for the personality/temperament variables (1 year stabilities). Direct cross-lagged paths from alcohol use to subsequent personality/temperament variables were also estimated given speculation in the literature of the impact of alcohol use on self-regulation and reinforcement sensitivity (Koob & Volkow, 2010; Spear, 2002). Nested model tests suggested that all stability paths were equivalent over time (all ps > .05) with the exception of stability paths for the personality/temperament variables (Δχ2 (5) = 35.37, p < .01). Furthermore, all cross-lagged paths (e.g., W1 behavioral approach (drive) to W2 positive expectancies, W2 behavioral approach (drive) to W3 positive expectancies, etc. were equivalent over time (all ps > .05). The final model with equality constraints (except for the personality/temperament stabilities) provided a good fit to the data (χ2 (224) = 353.25, p < .01, CFI=.97, RMSEA= .04). Although all stability coefficients for the personality/temperament variables were statistically significant, there was a trend for personality/temperament to become less stable over time. Path coefficients from the personality/temperament variables to alcohol use and to alcohol appraisal variables are presented in Table 4. The path coefficients were in the expected direction, but most fell short of conventional criteria for significance (all ps<.10). These marginally statistically significant trends suggested that high levels of behavioral approach (drive) and impulsivity/fun seeking, and low levels of behavioral inhibition (anxiety) were prospectively associated with increases in alcohol use, controlling for prior use. High levels of behavioral approach (drive) were prospectively associated with increases in positive and negative expectancies, and lower subjective evaluations (more negative ratings) of negative outcomes. The exception was that high levels of fight-flight (fear/shyness) was prospectively associated with increases in negative expectancies (p<.05). Neither impulsivity/fun seeking nor behavioral inhibition (anxiety) were prospectively associated with alcohol appraisal variables. None of the paths from alcohol use to the personality/temperament variables were statistically significant (ps > .05, see Table 5). The pattern of findings along with those from our first model suggests that negative expectancies were a candidate mediator of the association between fight-flight (fear/shyness) and alcohol use., However, the 95% confidence interval (CI) suggested no evidence for a statistically significant mediational path (CI = −0.010 and .001).

Table 4.

Unstandardized Path Coefficients from Longitudinal Path Models for alcohol use and alcohol appraisals as outcomes (standardized coefficients in parentheses)

| Predictor | Dependent Variable

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use | Positive Outcome | Negative Outcome | |||

|

| |||||

| Likelihood | Evaluation | Likelihood | Evaluation | ||

| Personality | |||||

| BA (Drive) | 0.043* (.03 to .08) | 0.171+ (.06) | 0.017 (.01) | 0.210+ (.07 – .08) | 0.053+ (.06 – .07) |

|

| |||||

| Impulsivity/Fun Seeking | 0.048* (.03 to .08) | 0.109 (.04) | 0.012 (.008) | −0.023 (−.01) | −0.005 (−.01) |

|

| |||||

| BI (Anxiety) | −0.047* (−.08 to −.03) | −0.086 (−.03) | 0.018 (.01) | 0.010 (.003) | 0.002 (.003) |

|

| |||||

| Fight-Flight (Fear/Shyness) | −0.016 (−.02 to −.01) | 0.157 (.05) | 0.005 (.004) | 0.299** (.10) | −0.006 (−.01) |

|

| |||||

| Peers | |||||

| Perceived Peer Use | 0.175** (.13 to .24) | 0.325* (.09 to .12) | 0.136* (.08 to .14) | −0.296* (−.07 to −.11) | .065+ (.07 to .08) |

|

| |||||

| Parenting | |||||

| Parental Drinking | 0.004 (.03 to .08) | 0.004 (.02) | 0.008* (.06 to .07) | −0.009 (−.03 to −.04) | 0.001 (.01 to .03) |

|

| |||||

| Health Messages | 0.007 (.003 to .01) | 0.379** (.13 to .14) | 0.004 (.003) | 0.155 (.04 to .05) | 0.028 (.04) |

|

| |||||

| Reactions to Drinking | 0.001 (.001) | −0.079 (−.04) | −0.002 (−.002) | −0.023 (−.01) | 0.014 (.03) |

|

| |||||

| Neighborhood | |||||

| Alcohol Outlets | −0.008 (−.005 to −.002) | −0.29 (−.03) | −0.10 (−.02) | −0.08 (−.01) | −0.17 (−.07) |

|

| |||||

| Residents’ Approval | 0.001 (.001 to .002) | 0.15 (.04) | 0.04 (.02) | 0.08 (.02) | 0.05 (.04 to .05) |

Note.

p<.01;

p<.05;

p<.10.

BA= behavioral approach; BI= behavioral inhibition. Ranges are reported for standardized coefficients because for some effects they varied slightly across the different lags given that variances were not constrained to be equal over time.

Table 5.

Unstandardized Path Coefficients from Longitudinal Path Models for paths from alcohol use to personality/temperament, peer, and parenting variables

| Outcome | Path Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Personality | |

| BA (Drive) | 0.043* (.03 to .08) |

| Impulsivity/Fun Seeking | 0.048* (.03 to .08) |

| BI (Anxiety) | −0.047* (−.08 to −.03) |

| Fight-Flight (Fear/Shyness) | −0.016 (−.02 to −.01) |

| Peers | |

| Perceived Peer Use | 0.175** (.13 to .24) |

| Parenting | |

| Parental Drinking | 0.004 (.03 to .08) |

| Health Messages | 0.007 (.003 to .01) |

| Reactions to Drinking | 0.001 (.001) |

Note.

p<.01;

p<.05;

p<.10;

BA= behavioral approach; BI= behavioral inhibition. Ranges are reported for standardized coefficients because for some effects they varied slightly across the different lags given that variances were not constrained to be equal over time.

Peers

Perceived peer alcohol use was added to the model depicted in Figure 2. Nested model tests suggested the stability paths for perceived peer use were not equivalent (Δχ2 (2) = 13.0, p < .01). The other stabilities were equivalent over time. Furthermore, cross-lagged paths were equivalent over time (all ps > .05) with the exception of paths from alcohol use to perceived peer use (Δχ2 (2) = 6.67, p < .05) . The final model with equality constraints (other than stabilities for peer use and paths from alcohol use to peer use) provided a good fit to the data (χ2 (104)=201.62, p < .01, CFI=.95, RMSEA= .05). The stability coefficients for perceived peer alcohol use suggested less stability over time. Cross-lagged path coefficients are presented in Table 4. High levels of perceived peer alcohol use were associated with increases in alcohol use and positive expectancies, and decreases in negative expectancies. High perceived peer alcohol use was also associated with high subjective evaluations of both positive (more positive ratings) and negative outcomes (less negative ratings). Alcohol use was associated with increases in perceived peer alcohol use across the first, but not the second lag (W2 to W3) (see Table 5). These findings along with those from our first model pointed to two possible mediated paths, such that W2 positive and negative expectancies were potential mediators of the association between W1 peer use and W3 alcohol use. Neither were statistically significant (CI = .00 to .02 for positive expectancies, and CI = −.01 to .01 for negative expectancies, ps > .05).

Parents

Parent alcohol use and alcohol specific parenting were added to the model depicted in Figure 2. Nested model tests suggested that all direct paths, including stability paths and cross-lagged paths were equal over time (all ps > .05). The final model with equality constraints provided an adequate fit to the data (χ2 (192)=426.86, p < .01, CFI=.92, RMSEA= .06). Path coefficients for cross-lag paths are presented in Table 3. Only two paths from parent variables to alcohol appraisal were statistically significant. Contrary to hypotheses, parental communication of health risks of drinking was prospectively associated with increases in positive expectancies. Also, parental drinking was prospectively associated with high subjective evaluations (more positive ratings) of positive outcomes. Adolescent alcohol use was not prospectively associated with change in alcohol-specific parenting (all ps > .05) (see Table 5). The mediational path from W1 communication of health risks to W2 positive expectancies to W3 alcohol use was statistically significant (CI=.003 to .014, p < .05). Frequent communication of health risks of alcohol use was associated with increases in positive expectancies, which in turn, were associated with increases in alcohol use.

Neighborhood

Density of alcohol outlets and adult approval of adolescent drinking at W1 were added to the model depicted in Figure 2. Paths from these variables to alcohol appraisal variables (W1–W3) and to alcohol use (W1–W4) were estimated. Neighborhood SES was included as a statistical control variable (in addition to gender and age), and thus, paths from neighborhood SES to alcohol appraisal variables and alcohol use were also estimated. Paths from alcohol use to the neighborhood variables were not estimated as we did not expect our participants’ drinking behavior to have an impact on density of alcohol outlets or adult attitudes. Nested model tests suggested equivalence of paths (all ps >.05) from the two neighborhood variables to subsequent alcohol appraisal (e.g., alcohol outlets at W1 to evaluations of negative outcomes at W2–W3 were equivalent, etc.) and to alcohol use (e.g., adult approval of adolescent alcohol use at W1 to alcohol use at W2–W4 were equivalent, etc.). The final model with equality constraints provided a good fit to the data (χ2 (105)=181.87, p < .01, CFI=.94, RMSEA= .04). Path coefficients are presented in Table 4. None of the paths from neighborhood variables to alcohol appraisal variables were statistically significant. Hence, there were no candidate mediational paths to be tested.

Discussion

Informed by a developmental ecological framework, this study examined how cognitive appraisals of alcohol use are shaped by direct experience with alcohol and by individual and socio-environmental-level factors, and how appraisals might operate in mediational pathways to alcohol use. Taking a comprehensive approach, we considered several aspects of alcohol appraisals, including positive and negative outcome expectancies as well as subjective evaluations of these expected outcomes.

Alcohol Appraisals and Alcohol Use

Much of the research examining adolescent outcome expectancies has focused on positive expectancies in part because findings regarding prospective effects of negative expectancies on alcohol use have been mixed (e.g., Cranford, Zucker, Jester, Puttler, & Fitzgerald, 2010; Mann, Chassin, & Sher, 1987; Leigh & Stacy, 2004; Stacy, Widaman, & Marlatt, 1990). Consistent with several other longitudinal studies of adolescent drinking, we found that high levels of positive expectancies were prospectively associated with drinking (Natvigaas, Leigh, Anderssen, & Jakobsen, 1998; Christiansen, Smith, Roehling, & Goldman, 1989; Wardell & Read, 2013; Wardell, Read, Colder, & Merrill, 2012). Our results also suggested that low levels of negative expectancies were prospectively associated with alcohol use. Moreover, examination of the standardized path coefficients suggests that the associations for positive and negative expectancies were of similar magnitude. Our sample and design spanned early to middle adolescence, and as would be expected given this developmental period, most youth had not yet initiated drinking at the first assessment. Hence, alcohol use in our sample reflects the early stages of alcohol use (initiation and experimentation), and our findings should be understood within this developmental context. That is, our findings suggest that among early adolescents who are in the early stages of alcohol use, both positive and negative expectancies are prospectively associated with changes in alcohol use.

We also found that prior levels of alcohol use were associated with changes in negative, but not positive expectancies. High levels of drinking were associated with decreases in negative expectancies. It is possible that as youth age and gain experience with alcohol, negative expectancies weaken, perhaps because negative consequences are rare in initial alcohol use episodes (Goldberg et al., 2002). Over time, as youth move into later adolescence, weakening negative expectancies may leave positive expectancies as the more dominant influence on drinking. Several lines of evidence support this notion. First, there is evidence that alcohol use prospectively influences outcome expectancies (Leigh & Stacy, 1998). Second, positive expectancies become increasingly dominant in adolescents’ memory networks with age (Dunn & Goldman, 1998). Finally, negative outcomes are perceived as more likely than positive outcomes in early adolescents, but with age, this gap narrows (Colder et al., 2014; O’Connor et al., 2007). In short, the relative importance of positive and negative expectancies may shift with age and experience with alcohol. This may account for inconsistencies in the literature regarding conclusions about the role of negative expectancies to the degree that samples differ in terms of age and stage of alcohol use.

There was no evidence of associations between subjective evaluations and alcohol use. One possibility is that subjective evaluations operate as moderators of expectancies. (Bauman & Bryan, 1980). We tested these interactions and found support for moderation with respect to negative outcomes, but not positive outcomes.1 In our prior work, we found that adolescent evaluations of alcohol outcomes were negative or neutral (Colder et al., 2014; O’Connor et al., 2007), even for outcomes typically considered to be positive. It is possible that subjective evaluations of positive outcomes may not be an important influence on alcohol use during early adolescence because youth maintain a predominantly negative view of alcohol during this period. In the current study, we found that alcohol use was prospectively associated with evaluations of positive outcomes, suggesting that drinking experience shifts evaluations (in addition to expected likelihood perceptions). Subjective evaluations of positive outcomes may come to influence alcohol use as drinking experience accumulates and alcohol appraisals shift (Fromme, Stroot, & Kaplan, 1993).

Psychosocial Correlates of Alcohol Appraisals

Contemporary developmental theories emphasize the role of the individual and multiple social contexts (e.g., Sameroff, 2009), and this emphasis is well represented in etiological theories of adolescent alcohol use (Flay & Petraitis, 1994; Zucker, 2000). Accordingly, we examined individual level (personality/temperament) and social contextual factors (peers, family, and community) as potential influences that shape alcohol appraisals.

Adolescents are not passive observers of their environment, and personality/temperament is believed to impact how they appraise both direct and indirect experiences (Smith & Anderson, 2001). Our results involving personality/temperament provided some evidence for this notion, but many of these associations did not meet conventional criteria for significance (ps < .10). We provide some discussion of these associations because they largely replicate some of our previous cross-sectional findings (Lopez-Vergara et al., 2012) albeit associations were weaker in this longitudinal analysis. We found some evidence for the associations between behavioral approach (drive) and alcohol appraisals. Consistent with research with adults (O’Connor & Colder, 2005, Wardell et al., 2012), high levels of drive, a component of the behavioral approach, were marginally associated with high levels of positive expectancies (p=.08). RST postulates that cues signaling potential reinforcement are more salient for individuals with a strong behavioral approach system (Gray & McNaughton, 2000). Thus, observed or vicariously experienced positive alcohol outcomes may be particularly salient for children characterized by a strong behavioral approach system, increasing the probability of forming positive expectancies. Behavioral approach (drive) was also marginally associated with increases in negative expectancies (p=.09). A strong behavioral approach system has been linked to risky drinking patterns and negative consequences (O’Connor & Colder, 2005). Youth with a strong behavioral approach system may therefore experience more negative consequences of drinking that over time may lead to negative expectancies. However, these negative expectancies are not necessarily expected to curtail drinking among those with a strong behavioral approach system.

Findings also suggested that high levels of fight-flight (fear/shyness) were associated with increases in negative expectancies. Although not commonly considered in models of addiction, a strong fight-flight system might be associated with high negative expectancies because this system is thought to mediate sensitivity to aversive stimuli, which may increase sensitivity to potential aversive consequences of drinking (e.g., getting sick, getting into trouble).

Findings suggested that neither behavioral inhibition (anxiety) nor impulsivity/fun seeking were associated with alcohol appraisal. There is ample evidence that anxiety and impulsivity/fun seeking are complex constructs, and some facets of these constructs (e.g., physiological symptoms for anxiety, positive urgency for impulsivity) may be more germane to alcohol appraisals than others (Nichter & Chassin, 2015; Settles et al., 2014). Worry was heavily represented in our behavioral inhibition measure and “rash impulsiveness”, which has been linked to executive control rather than reward sensitivity (Dawe et al., 2004), was heavily represented in our impulsivity/fun seeking measure. These aspects of personality/temperament were directly associated with alcohol use, but do not appear to influence alcohol appraisals.

It is notable that our RST variables (behavioral approach, behavioral inhibition, impulsivity/fun seeking) were more robustly associated with alcohol use than alcohol appraisals. Our measures of alcohol appraisals assessed explicit consciously controlled cognitive processing of alcohol-related information. Reinforcement sensitivities have been described as emanating from reactive neural systems (Rothbart & Bates, 2006), and this suggests that reinforcement sensitivity may be more strongly linked to implicit automatic cognitive processing of alcohol-related information. An important direction for future research would be to examine associations between reinforcement sensitivity and implicit measures of alcohol appraisals.

Perceived peer alcohol use was the most robust correlate in our study, prospectively associated with all four of the alcohol appraisal variables. The perception of peer alcohol use was associated with an increase in positive and a decrease in negative expectancies, and more positive (or less negative) evaluations of both positive and negative outcomes. Prior research has linked peer alcohol use and positive expectancies (e.g., Cumsille et al., 2000; Martino et al., 2006; Ouellette et al., 1999; Zamboanga et al., 2009). Our findings suggest that peer context may influence alcohol appraisals more broadly than just perceived likelihood of positive outcomes. We assessed perceived peer alcohol use as opposed to actual peer use. Although there are some drawbacks of using perceptions of peer use (e.g., projection of personal use on perceptions of peer use), perceptions may be more relevant in shaping appraisals and behavior, even if they are inaccurate (Henry, Kobus, & Schoney, 2011; Trucco, Colder, & Wieczorek, 2011). Perceiving alcohol use as normative may lead adolescents to adopt positive attitudes about drinking to foster acceptance and cohesion with peers (Trucco, Colder, Bowker, & Wiezcorek, 2011). Although the pattern of associations suggested that alcohol appraisals might mediate the association between peer alcohol use and subsequent increases in levels of drinking, we found no evidence for mediation. This suggests that the perception of peers appears play a role in shaping alcohol appraisals, but these perceptions appear to influence drinking directly in early adolescence, perhaps through modeling and social reinforcement (Ennett et al., 2008).

The family is another important social context that appeared to influence adolescent alcohol appraisals and use in our study. We found that parental drinking was associated with subjective evaluations, but not with expectancies. Specifically, high levels of parental drinking were prospectively associated with more positive evaluations of positive alcohol outcomes. This suggests that parental modeling of alcohol use conveys positive aspects of alcohol use that are transmitted to adolescents (Ary, Tildesley, Hope, & Andrews, 1993). Contrary to our expectation, frequent parental communication of the risks of alcohol use was associated with increases in positive expectancies. Goldberg et al. (2002) found that initial episodes of adolescent alcohol use are typically associated with positive experiences and few negative consequences resulting in marked age-related decline in the expected likelihood of negative outcomes. It is possible that lack of negative drinking outcomes either observed from peers or directly experienced may create a mismatch with parental messages about the risks of drinking. This mismatch may lead to the perception that parental messages are overly cautious, and a bias toward focusing on positive outcomes. These conclusions, however, remain speculative, and it will be important for future research to replicate our findings.

Finally, we considered community factors that are conceptually linked to alcohol appraisals, including adult residents’ approval of adolescent alcohol use and density of alcohol outlets. There was no evidence that these factors were associated with alcohol appraisals or with alcohol use. Community effects on child outcomes tend to be small and distal (Chung & Steinberg, 2006; Mrug & Windle, 2009; Trucco et al., 2014). Moreover, community level factors are believed to have a stronger influence as children age into late adolescence when they have more unsupervised direct contact with their community and neighbors (Aber, Gephart, Brooks-Gunn, Connell, & Spencer, 1997). Thus, the lack of community effects may be attributable to weak distal mechanisms, or the relatively young age of the sample, or both. Another possibility is limited variability and range in our community measures or low reliability. This seems to be a potential explanation for lack of effects of neighborhood adults’ approval of adolescent alcohol use because the majority of the sample (90%) reported adults strongly disapprove or disapprove of adolescent drinking and this construct was assessed with one item.

Limitations and Conclusions

Although this study makes an important contribution to our understanding of the development of adolescent appraisals of alcohol, it is important to note some limitations. First, our longitudinal sample spanned early to middle adolescence, and most adolescents had limited direct experience with alcohol at the initial assessments. Our findings are best understood as providing insight into the early stages of alcohol use and alcohol appraisal formation, and should not be generalized to other ages or later stages of alcohol use (e.g., heavy use or misuse). Second, it is possible that the socio-environmental variables in this study operate together through meditational or moderational models. Such processes were too complex to test given our sample size and the incorporation of multiple domains of alcohol appraisals. Given the remarkable dearth of studies examining the development of alcohol appraisals, our study is an important step forward for this literature in that we examined an impressive breadth of psychosocial correlates. Nonetheless, future studies might begin to further develop more complex models that incorporate other potential moderating or mediating mechanisms. Third, some cognitive models of addiction make the distinction between implicit and explicit appraisals of drug-related information (Wiers et al., 2007). Our study focused on aspects of explicit appraisals. An important direction for future research is to extend our study to examine correlates of implicit appraisals, as these also have been linked to drinking outcomes. As noted above, this may be particularly important when considering reinforcement sensitivity aspects of personality/temperament. Fourth, there were some differences between participants with missing data and those who had complete data. Although these differences were small and few, the attrition rate was low, and full-information maximum likelihood estimation was used to include all cases in our analysis, there is the possibility that missing data created some small bias in our findings. Finally, in some cases, limited range and low reliability may account for some of the observed null associations (e.g., neighborhood residents’ approval of adolescent drinking and fear/shyness).

In conclusion, adolescence is an important period for the formation of alcohol appraisals (e.g., Bekman et al., 2011; Cameron et al., 2003, Colder et al., 2014). Richter (2010) argued that developmentally informed health promotion interventions should strive to “support, alter, or redirect developmental processes that are already in motion” (p. 103) and that there likely are critical periods for successful intervention. Our work suggests that the social environment (parents and peers) and individual differences (reinforcement sensitivity) may be linked to the development of alcohol appraisals during early and middle adolescence. One of the most robust correlates of alcohol appraisals and of alcohol use was perceptions of peer alcohol use. Hence, it may be useful for preventive interventions to consider these factors when targeting alcohol appraisals, perhaps in combination with reinforcement sensitivities that impact the degree to which benefits of drinking are integrated into such appraisals. Furthermore, health promotion messaging for adolescents has been matched to personality/temperament with some success (Donohew, Bardo, & Zimmerman, 2004). Our data suggest that similar strategies may work for children characterized by a strong behavioral approach. However, our findings suggest some caution as focusing on the risks of drinking may have paradoxical effects. This may be particularly true if the risks messages do not match the adolescent’s experience.

Footnotes

Interaction terms between expectancies and subjective evaluations (positive expectancies x evaluation of positive outcomes and negative expectancies x evaluation of negative outcomes) were also tested. The interaction for negative (p<.05), but not positive (p>.25) expectancies was a statistically significant predictor of alcohol use. Strong negative expectancies were associated with low levels of drinking, particularly when evaluations of negative expectancies were more negative (as opposed to neutral).

References

- Aber JL, Gephart M, Brooks-Gunn J, Connell J, Spencer MB. Neighborhood, family, and individual processes as they influence child and adolescent outcomes. In: Brooks-Funn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty: Vol 1. Context and consequences for children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ary DV, Tildesley E, Hops H, Andrews J. The influence of parent, sibling, and peer modeling and attitudes on adolescent use of alcohol. Substance Use & Misuse. 1993;28(9):853–880. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Bryan ES. Subjective expected utility and children’s drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1980;41:952–958. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1980.41.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekman NM, Goldman MS, Worley MJ, Anderson KG. Pre-adolescent alcohol expectancies: Critical shifts and associated maturational processes. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2011;19(6):420. doi: 10.1037/a0025373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris P. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Lerner RM, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development. 5. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron CA, Stritzke WGK, Durkin K. Alcohol expectancies in late childhood: An ambivalence perspective on transitions toward alcohol use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(5):687–698. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin LA, Hussong AM, Beltran I. Adolescent substance use. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 723–764. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen BA, Smith GT, Roehling PV, Goldman MS. Using alcohol expectancies to predict adolescent drinking behavior after one year. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1989;57(1):93. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HL, Steinberg L. Relations between neighborhood factors, parenting behaviors, peer deviance, and delinquency among serious juvenile offenders. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):319–331. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, O’Connor RM. Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity model and child psychopathology: Laboratory and questionnaire assessment of the BAS and BIS. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(4):435–451. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000030296.54122.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, O’Connor RM, Read JP, Eiden RD, Lengua LJ, Hawk LW, Wieczorek WF. Growth trajectories of alcohol information processing and associations with escalation of drinking in early adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(3):659–70. doi: 10.1037/a0035271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Trucco EM, Lopez HI, Hawk LW, Jr, Read JP, Lengua LJ, … Eiden RD. Revised reinforcement sensitivity theory and laboratory assessment of BIS and BAS in children. The Journal of Research in Personality. 2011;45(2):198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa FM, Jessor R, Turbin MS, Dong Q, Zhang H, Wang C. The role of social contexts in adolescence: Context protection and context risk in the United States and China. Applied Developmental Science. 2005;9(2):67–85. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads0902_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Zucker RA, Jester JM, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE. Parental alcohol involvement and adolescent alcohol expectancies predict alcohol involvement in male adolescents. Psychology of addictive behaviors. 2010;24(3):386. doi: 10.1037/a0019801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumsille PE, Sayer AG, Graham JW. Perceived exposure to peer and adult drinking as predictors of growth in positive alcohol expectancies during adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):531–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Gullo MJ, Loxton NJ. Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: Implications for substance misuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(7):1389–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Goldman MS, Smith GT. Advancing the expectancy concept via the interplay between research and theory. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:926–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohew L, Bardo MT, Zimmerman RS. In: On the psychobiology of personality: Essays in honor of Marvin Zuckerman. Stelmack RM, editor. New York: Elsevier Science; 2004. pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Molina BSG. Children’s introduction to alcohol use: Sips and tastes. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;21:108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Molina BSG, Kelly TM. Alcohol outcome expectancies as socially shared and socialized beliefs. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(2):248–259. doi: 10.1037/a0015061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, Goldman MS. Age and drinking-related differences in the memory organization of alcohol expectances in 3rd-, 6th-, 9th-, and 12th-grade children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(3):579. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D. Social class and delinquent behavior in a national youth panel. Criminology: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 1983;21(2):149–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Cai L, Reyes HLM, … DuRant R. The social ecology of adolescent alcohol misuse. Child development. 2008;79(6):1777–1791. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Petraitis J. The theory of triadic influence: A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. In: Albrecht GS, editor. Advances in Medical Sociology. IV. Greenwich: JAI Press; 1994. A reconsideration of models of health behavior change. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming K, Thorson E, Atkin CK. Alcohol Advertising Exposure and Perceptions: Links with Alcohol Expectancies and Intentions to Drink or Drinking in Underaged Youth and Young Adults 1. Journal of health communication. 2004;9(1):3–29. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D’Amico EJ. Measuring adolescent alcohol outcome expectancies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(2):206–212. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR. The alcohol skills training program: A group intervention for young adult drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1994;11(2):143–154. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot E, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(1):19–26. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JH, Halpern-Felsher BL, Millstein SG. Beyond invulnerability: The importance of benefits in adolescents’ decision to drink alcohol. Health Psychology. 2002;21(5):477–484. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.21.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Del Boca FK, Darkes J. Alcohol expectancy theory: The application of cognitive neuroscience. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 203–246. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, McNaughton N. The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the sept - hippocampal system. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn RL, Smith GT. Risk factors for elementary school drinking: Pubertal status, personality, and alcohol expectancies concurrently predict fifth grade alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:617–627. doi: 10.1037/a0020334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haegerich TM, Tolan PH. Core competencies and the prevention of adolescent substance use. New directions for child and adolescent development. 2008;2008(122):47–60. doi: 10.1002/cd.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Kobus K, Schoeny ME. Accuracy and bias in adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(1):80–89. doi: 10.1037/a0021874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Successful adolescent development among youth in high-risk settings. American Psychologist. 1993;48:117–126. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JM, Wong MM, Cranford JA, Buu A, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Alcohol expectancies in childhood: change with the onset of drinking and ability to predict adolescent drunkenness and binge drinking. Addiction. 2015;110(1):71–79. doi: 10.1111/add.12704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2002 (Vol. 1): Secondary school students. Bethesda: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2003. NIH Publication No. 03-5375. [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodl MM, Mermelstein R. Beyond modeling: Parenting practices, parental smoking history, and adolescent cigarette smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(1):17–32. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stacy AW. Individual differences in memory associations involving the positive and negative outcomes of alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive behaviors. 1998;12(1):39. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stacy AW. Alcohol expectancies and drinking in different age groups. Addiction. 2004;99(2):215–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Vergara HI, Colder CR, Hawk LW, Jr, Wieczorek WF, Eiden RD, Lengua LJ, Read JP. Reinforcement sensitivity theory and alcohol outcome expectancies in early adolescence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(2):130–134. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32(10):2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann LM, Chassin L, Sher KJ. Alcohol expectancies and the risk for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55(3):411. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Schell TL, McCaffrey D. Socio-environmental influences on adolescents’ alcohol outcome expectancies: A prospective analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:971–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Marlatt GA. The Collateral Interview Form. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Miller PM, Smith GT, Goldman MS. Emergence of alcohol expectancies in childhood: A possible critical period. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1990;51(4):343–349. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Windle M. Mediators of neighborhood influences on externalizing behavior in preadolescent children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:265–280. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus(Version 6.1) [Computer Software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Hummer JF, Lac A, Labrie JW. What are other parents saying? Perceived parental communication norms and the relationship between alcohol-specific parental communication and college student drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(1):31–41. doi: 10.1037/a0034496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natvigaas H, Leigh BC, Anderssen N, Jakobsen R. Two-year longitudinal study expectancies and drinking adolescents of alcohol among Norwegian. Addiction. 1998;93(3):373–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9333736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Walker DD, Larimer ME. Expectancies and evaluations of alcohol effects among college students: self-determination as a moderator. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2003;64(2):292–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichter B, Chassin L. Separate dimensions of anxiety differentlially predict alcohol use among male juvenile offenders. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;50:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor R, Colder CR. Predicting alcohol patterns in first-year college students through motivational systems and reasons for drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(1):10–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RM, Fite PJ, Nowlin PR, Colder CR. Children’s beliefs about substance use: An examination of age differences in implicit and explicit cognitive precursors of substance use initiation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(4):525–533. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RM, Lopez-Vergara HI, Colder CR. Implicit cognition and substance use: the role of controlled and automatic processes in children. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2012;73(1):134. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette JA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M. Parents, peers, and prototypes: Antecedents of adolescent alcohol expectancies, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related life problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Richter M. Risk behavior in Adolescence: Patterns, determinants, and consequences. Hackensack: VS Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology. 6. Vol. 3. Wiley, N.Y: Wiley; 2006. pp. 1–77. ch.3. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]