Abstract

We examined social network typologies among African American adults and their sociodemographic correlates. Network types were derived from indicators of the family and church networks. Latent class analysis was based on a nationally representative sample of African Americans from the National Survey of American Life. Results indicated four distinct network types: ambivalent, optimal, family centered, and strained. These four types were distinguished by (a) degree of social integration, (b) network composition, and (c) level of negative interactions. In a departure from previous work, a network type composed solely of nonkin was not identified, which may reflect racial differences in social network typologies. Further, the analysis indicated that network types varied by sociodemographic characteristics. Social network typologies have several promising practice implications, as they can inform the development of prevention and intervention programs.

Keywords: Black family, informal social support, religion, social network, social network typologies

Extended family and church-based social networks are important resources for African Americans (Krause & Bastida, 2011; Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2004) because they provide social support to their members in the form of instrumental, emotional, social, and psychological assistance and resources. Among African Americans, social networks provide informal support to address personal issues such as physical and mental health problems (Cohen, Brittney, & Gottlieb, 2000; Taylor, Chae, Lincoln & Chatters, 2015) and daily life stressors (Benin & Keith, 1995). Moreover, social support is linked to higher levels of overall well-being (Nguyen, Chatters, Taylor, & Mouzon, 2016; Smith, Cichy, & Montoro-Rodriguez, 2015) and lower rates of serious psychological distress (Gonzalez & Barnett, 2014; Taylor et al., 2015). Studies of church-based social support similarly indicate that informal social support exchanges involving congregants are extensive (Taylor et al., 2004) and protective against mental and physical illnesses (Chatters, Taylor, Woodward, & Nicklett, 2015; Krause & Bastida, 2011).

Research on family and church-based social support typically uses a variable-centered approach, which implies that the population is homogeneous and that correlates of social support operate similarly for all groups. In contrast, a person-centered approach to social support assumes that the population is heterogeneous and seeks to identify meaningful subgroups or typologies of social support. The advantages of the person-centered approach to social networks include the ability to account for the complexity of social networks (e.g., interactional and functional aspects) and to identify and confirm patterns of network characteristic profiles or types.

Using latent class analysis (a technique for person-centered analysis), we investigate the prevalence and correlates of distinct social network typologies among African American adults. These network types are derived from family and congregational network characteristics, within a national sample of African American adults. Social network types are defined by constellations of social relationship and network characteristics. Research indicates that constellations of these characteristics (e.g., frequency of contact, social support, network size) that define specific social network types are predictors of mental illness (Levine, Taylor, Nguyen, Chatters, & Himle, 2015; Nguyen, Chatters, Taylor, Levine, & Himle, 2016) and thus represent risk profiles for mental illness. Information on groups that are likely to be in the most vulnerable risk profiles or network types (e.g., older, low-income men) will aid in the development of preventive interventions for these populations. The literature review begins with a discussion of the family solidarity model, which is the theoretical framework for the present analysis. This is followed by a review of scholarship on African Americans’ social networks and research on social network types.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Family Solidarity Model

The family solidarity model is a multidimensional model that assesses familial relations and family cohesion (Bengtson & Roberts, 1991). This model is particularly informative as a guiding theoretical framework for the present study, as it specifically conceptualizes the distinct facets of family social ties. Relationships between family members are assessed on the basis of six dimensions of behaviors, sentiments, and attitudes. A subset of these six solidarity dimensions—association, affect, and function—are the focus of this study. The association dimension relates to interactions between family members; the affect dimension assesses intimacy, or subjective closeness, between family members; and the function dimension examines exchanges of social support between family members. The model also accounts for negative interactions with family members. An elaboration of the family solidarity model, called the solidarity-conflict model (Bengtson, Giarrusso, Mabry, & Silverstein, 2002), acknowledges that conflict and negative interactions are normative aspects of familial relations and simultaneously exist with positive sentiments and behaviors. In the solidarity-conflict model, relationships high in both solidarity and negative interaction are regarded as ambivalent relationships (Bengtson et al., 2002; Connidis & McMullin, 2002).

The family solidarity model has also been applied to nonkin groups, such as church members (Taylor, Lincoln, & Chatters, 2005). The familylike qualities of African American congregational networks and the concept of belonging to a “church family” underscores the operation of solidarity dimensions in African American congregational networks (Krause, 2002; Taylor et al., 2005). Thus, the family solidarity model is also well suited to serve as a framework for exploring supportive relationships with congregants. For the purposes of this study, the term church and congregation are respectively used to broadly denote Christian and non-Christian places of worship, as well as the individuals who attend these places of worship.

African American Extended Family

Extended family members constitute an important source of support for African Americans (Lincoln, Taylor, & Chatters, 2012). African Americans generally rely more heavily on kin than nonkin for support (Taylor, Hernandez, Nicklett, Taylor, & Chatters, 2014) and are more likely than Whites to both provide and receive instrumental assistance such as help with household chores, transportation, and running errands (Gerstel, 2011). Although some argue that African Americans’ greater social involvement in the extended family network is more a function of class, with poorer people more heavily involved in their family networks as a result of need (Gerstel, 2011), O’Brien (2012) found that both middle- and upper-income African Americans were more likely to be involved in their family networks in terms of providing financial assistance than were Whites. With respect to family structure, African Americans are more likely than Whites to reside in extended family households, which are beneficial living arrangements because they allow for family members to pool economic and social resources and distribute household and caregiving responsibilities (Taylor, Chatters, Tucker, & Lewis, 1990).

Negative interactions, problematic social exchanges (e.g., conflicts, criticisms, demands) that are often experienced as unpleasant and stressful are universal features of social relations and are noted for their adverse impact on health and well-being (Lincoln, 2000; Rook, 1990). Prior research suggests that only a small percentage of African Americans frequently experience negative interactions with their extended family (Lincoln & Chae, 2012). Studies on the patterns and correlates of negative interactions can provide a better understanding of how they affect social relationships, who might be at greater risk for experiencing these events, and the ways that negative interactions influence health and well-being outcomes.

African American Congregational Networks

Historically, the African American church has been an important religious, social, and civic institution in Black communities (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). Informal social networks in these religious communities constitute an important source of support for congregants (Krause, 2008; Taylor et al., 2004). The most common types of support received from church members are socioemotional support, tangible assistance, and spiritual support (Chatters, Nguyen, & Taylor, 2014; Krause, Ellison, Shaw, Marcum, & Boardman, 2001). Spiritual support, assistance provided to a congregant that is designed to increase the individual’s religious commitments, beliefs, and behaviors, is an important and unique aspect of church-based support, as it is a primary function of congregations (Krause et al., 2001). Importantly, spiritual support can mitigate the negative effects of spiritual struggles on mental and physical health (Webb, Charbonneau, McCann, & Gayle, 2011).

Research on African Americans has found that the majority of people who attend church regularly receive support from congregants and that many receive support from both family and congregants, whereas only a small proportion of people receive support solely from their families (Chatters, Taylor, Lincoln, & Schroepfer, 2002; Taylor et al., 2004). This finding underscores the important and complementary role of congregants in African Americans’ informal support networks. Additionally, adult children are integral to the social integration of older African Americans in the congregational network by facilitating supportive exchanges for their parents by connecting their parents with other congregants. Previous studies have found that older African Americans who were parents tended to receive more support from congregants than their counterparts without children (Lincoln, Taylor, Watkins, & Chatters, 2011).

With regard to negative interactions with congregants, African Americans tend to report relatively low levels of negative interactions (Chatters et al., 2015; Ellison, Zhang, Krause, & Marcum, 2009). Similar to negative family interaction, its pernicious effects on health and well-being are evident. For example, negative interactions with congregants are predictive of psychological distress (Ellison et al., 2009), depressed affect (Krause, Ellison, & Wulff, 1998), and depressive symptoms (Chatters et al., 2015).

Social Network Typologies

Although previous studies have explored multiple social network characteristics individually, few have examined them jointly as constellations of network characteristics. Understanding these constellations of network characteristics in a more holistic manner can provide a fuller understanding of what types of naturally occurring social networks exist and their prevalence. Social network typology is an emerging area of research that focuses on identifying constellations of network characteristics, or network profiles. Overall, research in this area has identified four main typologies: family focused, friends focused, diverse, and restricted (Fiori, Smith, & Antonucci, 2007; Wenger, 1996). Members of the family-focused type are highly integrated into their family networks but are less integrated into nonfamily networks (e.g., friendship and congregational networks). The friend-focused type is characterized by higher integration into friendship networks as opposed to family networks. Persons in the diverse type are well integrated into both kin and nonkin networks, reflecting their diverse network composition. Finally, individuals in the restricted type are socially isolated.

Studies on social network types have made contributions to the literature by organizing interrelated data (i.e., network characteristics) into meaningful groups (i.e., typologies). This approach investigates how network characteristics group within individuals rather than how they combine across individuals, making this type of analysis person centered rather than variable centered. A person-centered approach to examining social networks captures the complex and dynamic nature of social networks and reflects the multidimensionality of social relations. Despite these contributions, there are several gaps in knowledge in this area. First, research on social network typologies has traditionally focused on either non-Hispanic White Americans or international populations (e.g., Israelis). Thus, we do not have information on social network types specific to racially diverse populations. Second, most studies on social network types have focused solely on positive relationship qualities. However, negative interaction is a ubiquitous aspect of social relationships.

To address these limitations, this study examined social network types among African Americans and used both positive and negative indicators of social network types. Given that many of the previously published works on social network types in other racial and ethnic groups have identified a diverse, family-focused, nonfamily-focused (e.g., friends-focused), and restricted type, we hypothesize that the social network types identified in this study, to some extent, reflect these previously established types (Hypothesis 1). Although sociodemographic correlates have not been systematically examined in research on social network typologies, studies on social networks have identified several sociodemographic correlates of social integration. In line with previous research, we hypothesize that education (Fiori, Antonucci, & Akiyama, 2008), household income (Fiori et al., 2008), number of children (Litwin & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011), and being married (Fiori, Antonucci, & Cortina, 2006), employed full-time (Gallie, Paugam, & Jacobs, 2003), a parent (Fiori et al., 2006), or a women (Fiori et al., 2006) are positively associated with belonging to a diverse type (Hypothesis 2a). Conversely, we hypothesize that age is negatively associated with belonging to a diverse type (Fiori et al., 2006; Hypothesis 2b).

METHOD

Sample

The sample for the present analyses was drawn from the National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL). The data were collected from 2001 to 2003 by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. The African American sample is a national probability sample of households located in the 48 coterminous states with at least one Black adult 18 years or older who did not identify as having ancestral ties in the Caribbean. A majority (56%) of the sample were women, and the overall mean age was 43 years.

Measures

Social network typology indicators

Congregational network items were assessed for all respondents who indicated that they attended religious services at least once a year, including those who reported no religious affiliation (11% of the sample). These items were assessed for religiously unaffiliated respondents because these individuals indicated that they attended religious services, which provides opportunities for social interactions with other congregants. Frequency of contact with congregants (associational solidarity) was measured by the question “How often do you see, write, or talk on the telephone with members of your church?” Possible responses ranged from never (1) to nearly every day (6). Subjective closeness to congregants (affectual solidarity) was measured by the question “How close are you to the people in your church?” with possible responses ranging from not close at all (1) to very close (4). Emotional support from congregants (functional solidarity) was measured by the questions “How often do the people in your church: (a) make you feel loved and cared for, (b) listen to you talk about your private problems and concerns, (c) express interest and concern in your well-being?” Negative interaction with congregants was assessed by the following three questions: “How often do the people in your church: (a) make too many demands on you, (b) criticize you and the things you do, and (c) try to take advantage of you?” The response categories for the emotional support and negative interaction questions ranged from never (1) to very often (4). Frequency of contact, subjective closeness, emotional support, and negative interaction for the extended family network were measured by questions similar to the congregational network indicators. As required for latent class analysis, all indicators were dichotomized, with low levels of the specific class indicator coded as 1 and high levels of the specific class indicator coded as 2 (McCutcheon, 2012).

Sociodemographic correlates

Sociodemographic correlates of social network types included gender, age, education, marital status, household income, parental status, number of children aged 13 years or older, and employment status. Gender and parental status were dummy coded. Age, education, income, and number of children were scored continuously. The log of income was used to minimize variance and account for its skewed distribution. Marital status was coded as married, partnered (i.e., cohabiting), separated, divorced, widowed, and never married. Employment status was coded as employed full-time, employed part-time, unemployed, retired, homemakers, students, and disabled or other. Missing data for income and education were imputed using an iterative regression-based multiple imputation approach incorporating information about age, sex, region, race, employment status, marital status, home ownership, and nativity of household residents.

Analysis Strategy

We used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify social network types; latent classes identified from this procedure represent social network types. Latent class multinomial logistic regression analysis, in which class probabilities are regressed on sociodemographic variables, was used to determine correlates of social network types. A three-step LCA approach was used to avoid the inclusion of the sociodemographic variables in the class extraction process (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2013). Because prior research suggests that parental status and age interact with each other in their effects on social support (Chatters et al., 2002; Taylor, Mouzon, Nguyen, & Chatters, 2016), a Parental status × Age interaction term was tested as a correlate of social network types. All analyses used analytic weights and statistical analyses accounted for the complex multistage clustered design of the NSAL sample, unequal probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and poststratifcation to calculate weighted, nationally representative population estimates and standard errors.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the study variables. The majority of respondents identified as Christian, and a small number of respondents identified with a religion other than Christianity or reported no religious affiliation. The mean household income and educational attainment level were consistent with national means for African Americans. About one-third of respondents were married, and another third had never married. More than three-quarters of respondents were parents, and the majority of the respondents were employed either full-time or part-time. Respondents tended to report moderate to high frequency of contact, subjective closeness, and emotional support with family and church members. Respondents reported relatively low levels of negative family and church interaction.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample and Distribution of Study Variables

| Characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1,271 | 44.03 | |

| Female | 2,299 | 55.97 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 960 | 32.91 | |

| Partnered | 260 | 8.74 | |

| Separated | 286 | 7.16 | |

| Divorced | 524 | 11.75 | |

| Widowed | 353 | 7.89 | |

| Never married | 1,170 | 31.55 | |

| Parental status | |||

| Does not have child | 668 | 21.76 | |

| Has child | 2,769 | 78.24 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed full-time | 1,795 | 50.80 | |

| Employed part-time | 538 | 16.02 | |

| Unemployed | 366 | 10.08 | |

| Retired | 99 | 2.57 | |

| Homemaker | 77 | 2.73 | |

| Student | 371 | 9.84 | |

| Disabled/other | 314 | 7.96 | |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| Baptist | 1,865 | 49.08 | |

| Methodist | 216 | 5.88 | |

| Episcopalian | 17 | .45 | |

| Pentecostal | 304 | 8.62 | |

| Catholic | 202 | 5.96 | |

| Other Christian | 549 | 17.25 | |

| Other religion | 71 | 2.25 | |

| Unaffiliated | 344 | 10.51 | |

| Social network types | |||

| Optimal | 811 | 22.76 | |

| Ambivalent | 1097 | 30.78 | |

| Family-centered | 686 | 19.26 | |

| Strained | 970 | 27.21 | |

| Characteristic | M | SD | Range |

| Age | 43.15 | 16.32 | 18–93 |

| Education | 12.30 | 2.58 | 0–17 |

| Household income (annual) | 32,037.15 | 32,687.94 | 0–520,000 |

| Number of children aged 13+ years | 1.61 | 2.05 | 0–15 |

| Frequency of contact with family | 6.13 | 1.28 | 1–7 |

| Subjective closeness to family | 3.64 | 0.65 | 1–4 |

| Family loves | 3.52 | 0.73 | 1–4 |

| Family listens | 2.79 | 1.12 | 1–4 |

| Family interested | 3.41 | 0.84 | 1–4 |

| Family demands | 2.04 | 1.03 | 1–4 |

| Family criticizes | 1.86 | 0.95 | 1–4 |

| Family takes advantage | 1.61 | 0.91 | 1–4 |

| Frequency of contact with congregants | 3.75 | 1.83 | 1–6 |

| Subjective closeness to congregants | 3.02 | 0.95 | 1–4 |

| Congregants loves | 3.44 | 0.78 | 1–4 |

| Congregants listens | 2.30 | 1.18 | 1–4 |

| Congregants interested | 3.13 | 1.00 | 1–4 |

| Congregants demands | 1.71 | 0.89 | 1–4 |

| Congregants criticizes | 1.44 | 0.77 | 1–4 |

| Congregants takes advantage | 1.29 | 0.66 | 1–4 |

Note. Percentages are weighted and frequencies are unweighted.

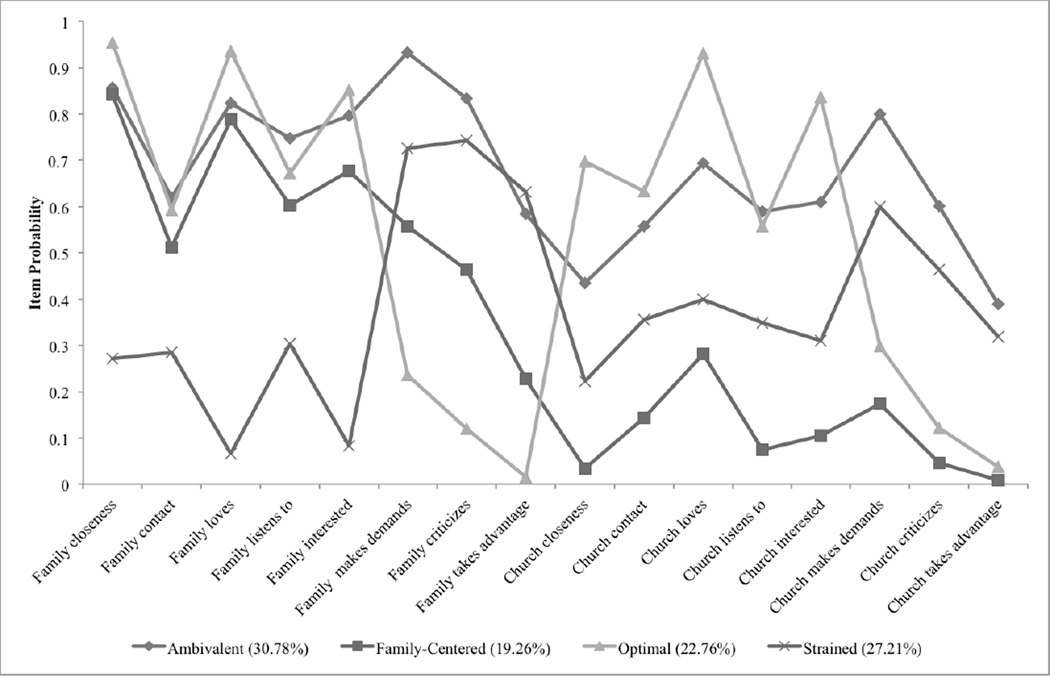

Hypothesis 1: Social Network Types

A series of LCAs indicated that the best-fitting model is a four-class model. Model fit was determined by the Akaike information criterion and sample-size-adjusted Bayesian information criterion. Item response probabilities are depicted in Figure 1. Four network types were identified on the basis of indicators for both the church and extended family networks: optimal, ambivalent, family centered, and strained. Members of the optimal type reported high levels of contact, subjective closeness, and emotional support from both family and church member and low levels of negative family and church interactions. The ambivalent type, the most prevalent type (30.8% of the sample), was similar to the optimal type with a few exceptions. Notably, respondents in this type reported low subjective closeness to congregants and high levels of negative interaction with both family and congregants. The strained type consisted of respondents who were low in contact, subjective closeness, and emotional support from family and congregants and had moderate to high levels of negative family and church interaction. The least prevalent type was the family-centered type (19.3% of the sample), which was characterized by moderate to high levels of contact, subjective closeness, and emotional support from family and low levels of subjective closeness, contact, and emotional support from congregants. Respondents in this type also reported low levels of negative family and church interactions.

Figure 1.

Conditional Item Probability Profile.

Hypothesis 2: Sociodemographic Correlates of Social Network Types

Results from the latent class multinomial logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 2. Sociodemographic variables served as the independent variables in this analysis, and the four social network types identified from church and family network indicators (i.e., optimal, ambivalent, family centered, strained) served as the dependent variable, with the optimal type set as the comparison category. The analysis revealed that the likelihood of being in the ambivalent or family-centered type, relative to the optimal type, increased as income increased across respondents. This finding essentially means that respondents with higher income were less likely than their lower-income counterparts to be socially integrated into a congregational network and tended to have more negative interactions with family members. Relative to married respondents, widowed respondents had a greater probability of being in the ambivalent type, and both never-married and separated respondents were more likely to be in the family-centered or strained type. Parents were more likely to belong to either the ambivalent or strained type than were nonparents. With respect to employment status, compared to those employed full-time, part-time employed and retired persons had a greater probability of being in the ambivalent type, unemployed respondents were more likely to be in either the ambivalent or the strained type, and homemakers were less likely to be members of the strained type and more likely to be members of the optimal type.

Table 2.

Latent Class Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of Social Network Types on Sociodemographic Correlates among African Americans (N = 3,343)

| Ambivalent (optimal) |

Family Centered (optimal) |

Strained (optimal) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent charcateristics | Logit | SE | p | OR | 95% CI | Logit | SE | p | OR | 95% CI | Logit | SE | p | OR | 95% CI |

| Female (male) | 0.10 | 0.18 | .572 | 1.11 | [0.78, 1.57] | −0.08 | 0.16 | .616 | 0.92 | [0.67, 1.26] | −0.15 | 0.10 | .124 | 0.86 | [0.71, 1.05] |

| Age | −0.02 | 0.01 | .067 | 0.98 | [0.96, 1.00] | 0.00 | 0.01 | .954 | 1.00 | [0.98, 1.02] | 0.01 | 0.01 | .231 | 1.01 | [0.99, 1.03] |

| Education | 0.11 | 0.03 | .001 | 1.12 | [1.05, 1.18] | 0.12 | 0.05 | .017 | 1.13 | [1.02, 1.24] | 0.04 | 0.03 | .115 | 1.04 | [0.98, 1.10] |

| Household Income | 0.24 | 0.11 | .028 | 1.27 | [1.02, 1.58] | 0.15 | 0.11 | .158 | 1.16 | [0.94, 1.44] | −0.04 | 0.09 | .639 | 0.96 | [0.81, 1.15] |

| Marital status (married) | |||||||||||||||

| Partnered | 0.11 | 0.29 | .700 | 1.12 | [0.63, 1.97] | 0.46 | 0.35 | .184 | 1.58 | [0.80, 3.15] | 0.50 | 0.28 | .077 | 1.65 | [0.95, 2.85] |

| Separated | 0.22 | 0.28 | .436 | 1.25 | [0.72, 2.16] | 0.01 | 0.29 | .975 | 1.01 | [0.57, 1.78] | 0.72 | 0.24 | .002 | 2.05 | [1.28, 3.29] |

| Divorced | 0.21 | 0.21 | .323 | 1.23 | [0.82, 1.86] | 0.10 | 0.25 | .702 | 1.11 | [0.68, 1.80] | 0.36 | 0.23 | .117 | 1.43 | [0.91, 2.25] |

| Widowed | 0.51 | 0.25 | .038 | 1.67 | [1.02, 2.72] | −0.21 | 0.40 | .601 | 0.81 | [0.37, 1.78] | −0.23 | 0.27 | .386 | 0.79 | [0.47, 1.35] |

| Never married | 0.29 | 0.26 | .270 | 1.33 | [0.80, 2.22] | 0.53 | 0.26 | .040 | 1.70 | [1.02, 2.83] | 0.51 | 0.24 | .034 | 1.67 | [1.04, 2.67] |

| Parent (nonparent) | 1.00 | 0.43 | .020 | 2.72 | [1.17, 6.31] | 1.16 | 0.71 | .105 | 3.19 | [0.79, 12.83] | 1.69 | 0.47 | < .001 | 5.42 | [2.16, 13.62] |

| Number of children 13+ | 0.06 | 0.04 | .178 | 1.06 | [0.98, 1.15] | 0.00 | 0.05 | .968 | 1.00 | [0.91, 1.10] | −0.05 | 0.04 | .237 | 0.95 | [0.88, 1.03] |

| Employment status (employed full-time) | |||||||||||||||

| Employed part-time | 0.54 | 0.22 | .016 | 1.72 | [1.11, 2.64] | 0.20 | 0.29 | .485 | 1.22 | [0.69, 2.16] | 0.31 | 0.23 | .175 | 1.36 | [0.87, 2.14] |

| Unemployed | 1.05 | 0.29 | < .001 | 2.86 | [1.62, 5.05] | 0.56 | 0.36 | .115 | 1.75 | [0.86, 3.55] | 0.82 | 0.29 | .004 | 2.27 | [1.29, 4.01] |

| Retired | 0.76 | 0.26 | .004 | 2.14 | [1.28, 3.56] | 0.31 | 0.26 | .227 | 1.36 | [0.82, 2.27] | 0.09 | 0.36 | .800 | 1.09 | [0.54, 2.22] |

| Homemaker | −0.29 | 0.36 | .419 | 0.75 | [0.37, 1.52] | −0.78 | 0.54 | .147 | 0.46 | [0.16, 1.32] | −1.12 | 0.36 | .002 | 0.33 | [0.16, 0.66] |

| Student | 1.03 | 0.87 | .235 | 2.80 | [0.51, 15.41] | 0.96 | 0.92 | .299 | 2.61 | [0.43, 15.41] | 1.05 | 0.85 | .215 | 2.86 | [0.54, 15.12] |

| Disabled/other | 0.27 | 0.25 | .285 | 1.31 | [0.80, 2.14] | −0.12 | 0.26 | .631 | 0.89 | [0.53, 1.48] | 0.15 | 0.21 | .492 | 1.16 | [0.77, 1.75] |

| Parent × age | −0.02 | 0.01 | .023 | 0.98 | [0.96, 1.00] | −0.02 | 0.02 | .377 | 0.98 | [0.94, 1.02] | −0.03 | 0.01 | .001 | 0.97 | [0.95, 0.99] |

Note. Reference category is in parentheses. CI = confidence interval for odds ratio (OR).

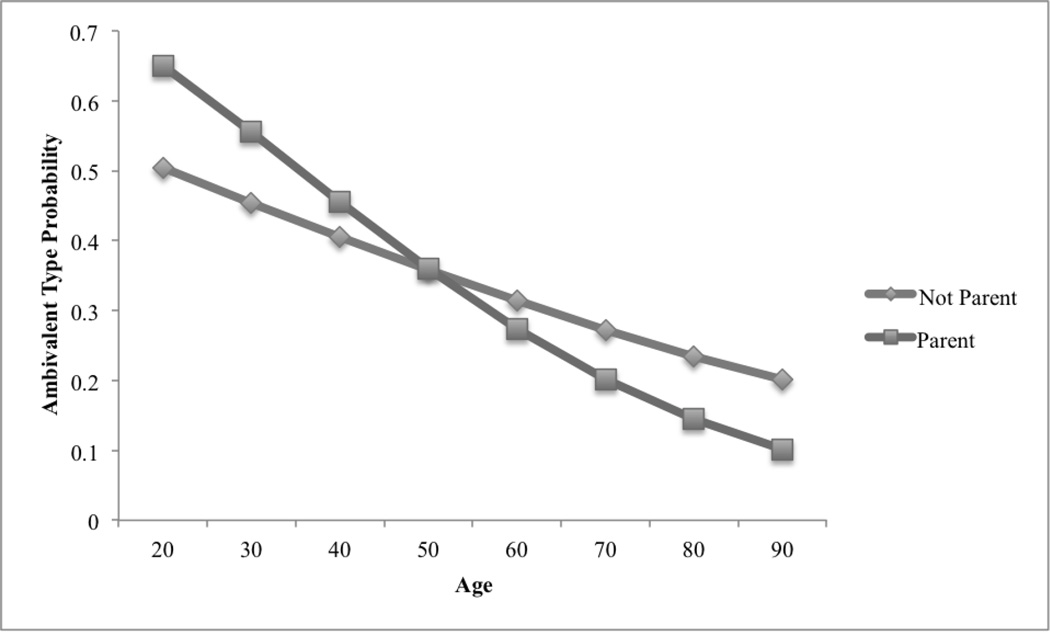

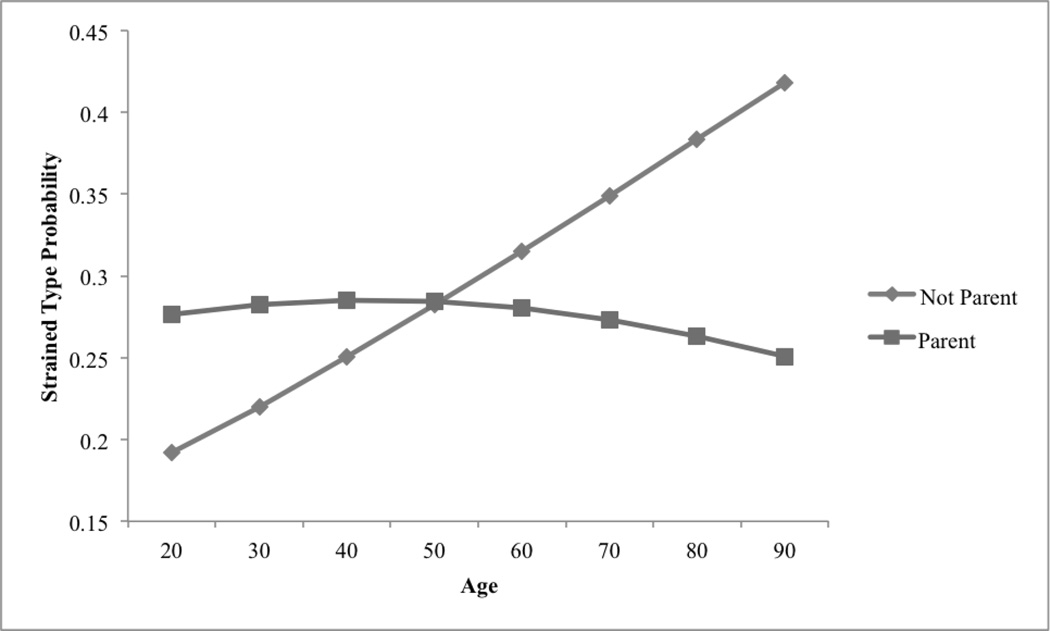

Several statistically significant interactions between age and parental status emerged. As illustrated in Figure 2, younger adults with children had higher probabilities of being in the ambivalent type than younger adults without children. This probability decreased with age, but the decrease was more pronounced for parents. Thus, among older respondents, those without children had a greater likelihood of being in the ambivalent type than those with children. A second interaction effect revealed that among younger adults, parents were more likely than nonparents to belong to the strained type (see Figure 3). The probability of being in the strained type increased with age for nonparent respondents, but for parents the probability of being in the strained type increased minimally with age until it began to decrease at about 50 years of age. Consequently, among older respondents the relationship between parental status and network type reversed; older parents were less likely to be in the strained type than were older nonparents.

Figure 2.

Predicted Probability of Membership in the Ambivalent Network Type by Parental Status and Age Among African Americans.

Figure 3.

Predicted Probability of Membership in the Strained Network Type by Parental Status and Age Among African Americans.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the findings partially confirm our hypotheses. We found four distinct patterns that characterized the extended family and congregational networks of African Americans on the basis of respondents’ reports of the nature of their family and congregational relationships. Three main network characteristics—social integration, network composition, and negative interaction—distinguished the four network types by features of both church- and family-based social ties. These patterns are similar to those identified in previous studies on social network types (Fiori et al., 2006; Litwin, 1997; Wenger, 1996). The optimal type included respondents who were socially integrated into both the congregational and the family networks and experienced minimal negative interaction with both networks. This network type represents the most favorable constellation of relational characteristics, as social involvement and lower levels of negative interaction are associated with better mental health and well-being outcomes (Nguyen et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2015).

The ambivalent type was similar to the optimal type, with the exception that members of this type reported high levels of negative interaction with congregants and family. This type is an important focus for future studies because an emerging area of research on ambivalence in social relationships has demonstrated that ambivalence is predictive of poorer health despite the presence of positive qualities in ambivalent ties (Rook, Luong, Sorkin, Newsom, & Krause, 2012; Uchino et al., 2012). The family-centered type was distinguished by social integration into the extended family network, social disengagement from the congregational network, and low levels of negative interaction with both congregants and family. Finally, the strained type included respondents who were socially disengaged from both their congregational and their family networks and experienced frequent negative interaction with both networks. This network type is the least socially endowed type, and members of this type are likely to be at elevated risk for mental health problems, given the established links between social disengagement and negative interaction and poor mental health status (Taylor, Taylor, Nguyen, & Chatters, 2016; Lincoln, 2000).

In a departure from previous work, we did not identify a nonkin-focused type (e.g., church-focused type), which may have been because of differences in the indicators used. In addition to congregational relationships, some prior studies also used indicators of friend and neighbor relationships (see Fiori et al., 2008; Litwin, 2001). The greater number of indicators of nonkin relationships may have facilitated the identification of a nonkin network type. However, the lack of a nonkin network type in this study also suggests the possibility of racial variations in social network types. This is not surprising, given that research has identified several differences in network characteristics between African Americans and Whites (Ajrouch, Antonucci, & Janevic, 2001). The present findings, coupled with previous research, suggest that social network types may vary among racial groups.

Ambivalent Versus Optimal Type

Ambivalence in the context of social relations often arises when sources of support are limited and, as a result, the individual depends on a select few individuals for support (Smelser, 1998). This dependence can lead to negative interactions with support networks. Our findings suggest that in the absence of a spouse, widowed respondents may depend on a small number of network members for support. This situation may introduce conflict into their relationships, especially if support needs are burdensome and persistent. Individuals with limited financial resources (e.g., unemployed, part-time employed, and retired individuals) are also likely to rely more heavily on their networks for support and assistance. Consequently, this heavy reliance on their networks for support and assistance could lead to relational strains.

Family-Centered Versus Optimal Type

We found that never-married respondents were more likely than their married counterparts to belong to the family-centered type rather than the optimal type. It is important to recall that the primary difference between these two network types is the level of social integration within the congregational network. Respondents in the optimal type were socially integrated into their family and congregational networks, and respondents in the family-centered type were socially integrated primarily into their family network. Extant research indicates that unmarried African Americans are less socially integrated into their congregational network and less likely to receive support from congregants than are married African Americans (Taylor & Chatters, 1988). In fact, some studies have indicated that unmarried individuals are less likely to attend church than married individuals (Brown, Taylor, & Chatters, 2013; Taylor et al., 2014). For instance, Taylor et al. (2014) found that unmarried persons attended religious services less frequently, were less likely to be church members, and participated in congregational activities (e.g., choir, women’s club) less frequently than their married counterparts. In regard to the present findings, given lower rates of congregational involvement, unmarried respondents may have fewer opportunities to cultivate congregational relationships and to become socially integrated into their congregational networks.

Strained Type Versus Optimal Type

Separated and never-married respondents were more likely to belong to the strained type. The strained typology is particularly important because it is characterized by high levels of negative interactions with both family and congregation members. Moreover, research has confirmed that negative interaction with family and congregation members is associated with negative psychological states, including more symptoms of depression and anxiety (Chatters et al., 2015) and various psychiatric disorders, including social anxiety (Levine et al. 2015) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Nguyen et al., 2016). Thus, the negative interactions that separated and never-married individuals experience with their social networks may place some of them at greater risk of possible psychological problems.

Homemakers were also less likely than full-time employed respondents to belong to the strained type and more likely to belong to the optimal type, a finding likely driven by the fact that the majority of homemakers in this study were women. Women who are not employed full-time tend to be more socially integrated into their family network because they have fewer constraints imposed by nonfamily roles (Moore, 1990; Pugliesi & Shook, 1998). Further, some prior research has found that more religiously involved women are less likely to be employed (Mahoney, 2010). For these reasons, homemakers were more likely to belong to a network type distinguished by high levels of social involvement in both the congregational and family networks. An additional finding for employment status showed that unemployed respondents were more likely than those employed full-time to belong to the strained type, which again demonstrates how dependence (due to financial limitations) can lead to relational conflicts.

Consistent with prior research, the interaction between parental status and age suggests that adult children act as social brokers for their aging parents to facilitate social connections to the family and congregational networks (Chatters et al., 2002). Accordingly, parents in the present analysis were less likely than respondents without children to belong to a socially disengaged network type.

These findings demonstrate the complex interaction between church- and family-based relationships. Literature on family ties in the context of religion has indicated that church-based relationships can reinforce and maintain family relationships through religious norms and ideologies. For example, Mahoney (2010, 2013) reported that (a) through the sanctification of family relationships, people perceive their relationships with family members as having spiritual character and meaning, which leads people to value and prioritize their family relationships; (b) spiritual support from congregants can reinforce the notion that family ties are sacred, which in turn reinforces the importance of maintaining strong family ties, and (c) religious activities that family perform together (e.g., religious service) can also reinforce family ties. In fact, many African Americans view their family ties as an extension of their faith experience, which can lead to greater relationship satisfaction and quality (Mattis & Grayman-Simpson, 2013).

Interestingly, our findings illustrate similarities in structure and function between church- and family-based relationships. With the exception of the family-centered type, all network types showed similar relationship patterns in the family and congregational networks. For example, high subjective closeness to family was also accompanied by high subjective closeness to congregants in the optimal and ambivalent types. In contrast, low subjective closeness to family was parallel to low subjective closeness to congregants in the strained type. These similar effects between family and congregational relationships support the argument that family solidarity dimensions exist in church-based relationships. In particular, the present analysis identified an associational, affectual, and functional solidarity dimension in church-based relationships. Overall, the present findings reinforce the notion that congregational and family networks are interrelated and demonstrate the synergetic effects family and church-based relationships have on one another.

Limitations and Strengths

The present findings must be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. First, because the NSAL only surveyed noninstitutionalized, community dwelling individuals, findings are generalizable only to this population. Second, all network measures were self-reported and thus subject to recall and social desirability biases. Third, because the data for the present analysis are cross-sectional, causal inferences on the relationship between sociodemographic correlates and network types cannot be made.

Despite these limitations, this study has several notable strengths. This analysis is the first to examine social network types in a national probability sample of African American adults across the life span using multiple indicators of extended family and religious congregational networks—two central institutions for understanding African American social networks. In particular, the inclusion of multiple congregational indicators assessing both interactional (frequency of contact) and relationship qualities (emotional support, perceived closeness, negative interaction) extends the current literature on network types in several ways. Previous studies that used a single congregational network indicator (e.g., religious service attendance) have provided some sense of integration into the network but are inadequate for assessing an individual’s relationships with congregants. Further, our analysis of network types incorporated both positive and negative aspects of social relations and provided important information concerning the interactive roles of social support, perceived affinity, and negative interaction in social relationships. The availability of a diverse set of congregational indicators provided an opportunity to explore family solidarity theory and to test the applicability of theoretical constructs (i.e., association, affection, and function) in relation to a recognized and principal cultural institution in the African American population. Finally, examining social network types derived from extended family and congregational network characteristics identified: (a) profiles that represent potential protections (e.g., optimal, family centered) and risks (e.g., strained, ambivalent) for social and mental health, (b) persons who may be vulnerable (e.g., separated) or advantaged (e.g., married) with respect to social network types, and (c) complex relationships between personal characteristics and membership in social network types (e.g., age and parental status interactions for ambivalent and strained networks). This level of specificity facilitates the development of interventions that acknowledge the social network and sociodemographic diversity in the African American population.

Future Directions

Several potential directions for future research in this area are possible. In extending existing literature on social network typologies, future work could investigate the association between extended family and congregation network typologies and various indicators of psychological well-being, psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression), and substance abuse disorders. Research along these lines could investigate whether and how an individual’s mental and behavioral health status is associated with characteristics of extended family and congregation networks. For example, would persons with substance abuse disorders be less likely to have support networks comprising church members? Future research could also examine neighbors, workplace, and other community networks as components of social network typologies. Taking a different perspective, given evidence of the detrimental health effects associated with relational ambivalence, future research could examine whether belonging to an ambivalent network type is associated with poorer mental and physical health.

Practice Implications

A major contribution of the present study is the resulting practice implications. Previous research has indicated that particular network types are associated with worse mental health (Levine et al., 2015; Nguyen, Chatters, Taylor, Levine, & Himle, 2016). As such, network types represent risk profiles that can be used as a screening instrument to identify vulnerable clients who are at risk of developing or deteriorating mental and physical health problems, as well as to assess clients’ social environments and resources. Moreover, information on sociodemographic correlates of network types provides useful information with regard to groups that are most likely to belong to vulnerable risk profiles. This knowledge can help practitioners effectively screen and identify specific groups that are more likely to belong to vulnerable network types, such as unmarried parents. In terms of interventions, findings from this study will help practitioners tailor and adapt interventions to the specific social support needs of clients, facilitating more effective treatments to address issues of social disengagement, problematic social interactions, and inadequate supports.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this investigation of social network types among African Americans is an initial effort to understand the different configurations of social networks in this population. This study demonstrated that network types vary across sociodemographic categories and underscored the synergetic relationship between the congregational and extended family networks. The study also makes a contribution by providing a deeper understanding of ambivalence in social relations, especially in nonkin relationships, and its correlates.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging to AWN (P30AG043073) and RJT (P30AG1528) and the National Institute for General Medicine to LMC (NIGMS R25GM058641-15).

Contributor Information

Ann W. Nguyen, University of Southern California

Linda M. Chatters, University of Michigan

Robert Joseph Taylor, University of Michigan.

References

- Ajrouch KJ, Antonucci TC, Janevic MR. Social networks among Blacks and Whites: The interaction between race and age. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56:S112–S118. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.2.s112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: 3-step approaches using Mplus. Mplus Web Notes. 2013;15:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Giarrusso R, Mabry JB, Silverstein M. Solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence: Complementary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:568–576. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Roberts RE. Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: An example of formal theory construction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:856–870. [Google Scholar]

- Benin M, Keith VM. The social support of employed African American and Anglo mothers. Journal of Family Issues. 1995;16:275–297. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RK, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Religious non-involvement among African Americans, Black Caribbeans and non-hispanic Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Review of Religious Research. 2013;55:435–457. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ. Religion and spirituality among older African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics. In: Whitfield KE, Baker TA, editors. Handbook of minority aging. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD. African American religious participation: A multi-sample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999;38:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Schroepfer T. Patterns of informal support from family and church members among African Americans. Journal of Black Studies. 2002;33:66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Nicklett EJ. Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Brittney L, Gottlieb BH. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA, McMullin JA. Ambivalence, family ties, and doing sociology. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:594–601. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Zhang W, Krause N, Marcum JP. Does negative interaction in the church increase psychological distress? Longitudinal findings from the Presbyterian Panel Survey. Sociology of Religion. 2009;70:409–431. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Relationship quality and changes in depressive symptoms among urban, married African Americans, Hispanics, and Whites. Family Relations. 2009;58:259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. Profiles of social relations among older adults: A cross-cultural approach. Ageing and Society. 2008;28:203–231. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Antonucci TC, Cortina KS. Social network typologies and mental health among older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61:P25–P32. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.p25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Smith J, Antonucci TC. Social network types among older adults: A multidimensional approach. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62:P322–P330. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.p322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie D, Paugam S, Jacobs S. Unemployment, poverty and social isolation: Is there a vicious circle of social exclusion? European Societies. 2003;5:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel N. Rethinking families and community: The color, class, and centrality of extended kin ties. Sociological Forum. 2011;26:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez H, Barnett MA. Romantic partner and biological father support: Associations with maternal distress in low-income Mexican-origin families. Family Relations. 2014;63:371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Sherry A, Bethea K, Wyckoff S, Compton MT, Grall MB, Thompson N. Social risk and protective factors for suicide attempts in low income African American men and women. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35:400–412. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring race differences in a comprehensive battery of church-based social support measures. Review of Religious Research. 2002;44:126–149. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Bastida E. Church-based social relationships, belonging, and health among older Mexican Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2011;50:397–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Ellison CG, Wulff KM. Church-based emotional support, negative interaction, and psychological well-being: Findings from a national sample of Presbyterians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37:725–741. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Ellison CG, Shaw BA, Marcum JP, Boardman JD. Church-based social support and religious coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40:637–656. [Google Scholar]

- Levine DS, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Himle JA. Family and friendship informal support networks and social anxiety disorder among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015;50:1121–1133. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The Black church in the African American experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD. Social support, negative social interactions, and psychological well-being. Social Service Review. 2000;74:231–252. doi: 10.1086/514478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chae DH. Emotional support, negative interaction and major depressive disorder among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012;47:361–372. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Correlates of emotional support and negative interaction among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;34:1262–1290. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12454655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Watkins DC, Chatters LM. Correlates of psychological distress and major depressive disorder among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011;21:278–288. doi: 10.1177/1049731510386122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H. Support network type and health service utilization. Research on Aging. 1997;19:274–299. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H, Shiovitz-Ezra S. The association of background and network type among older Americans: Is “who you are” related to “who you are with”? Research on Aging. 2011;33:735–759. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A. Religion in families: 1999–2009: A relational spirituality framework. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:805–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A. The spirituality of us: Relational spirituality in the context of family relationships. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality: Vol. 1. Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 365–389. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Grayman-Simpson NA. Faith and the sacred in African American life. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. Handbook of religion, spirituality, and psychology: Vol. 1. Context, theory, and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 547–564. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AL. Latent class analysis. 2nd. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moore G. Structural determinants of men’s and women’s personal networks. American Sociological Review. 1990;55:726–735. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Levine DS, Himle JA. Family, friends, and 12-month PTSD among African Americans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2016;8:1149–1157. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1239-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Mouzon DM. Social support from family and friends and subjective well-being of older African Americans. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2016;17:959–979. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9626-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien RL. Depleting capital? Race, wealth and informal financial assistance. Social Forces. 2012;91:375–396. [Google Scholar]

- Petts RJ. Single mothers’ religious participation and early childhood behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Petts RJ. Parental religiosity and youth religiosity: Variations by family structure. Sociology of Religion. 2015;76:95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. America’s changing religious landscape. Washington, DC: Author; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliesi K, Shook SL. Gender, ethnicity, and network characteristics: Variation in social support resources. Sex Roles. 1998;38:215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. Stressful aspects of older adults’ social relationships: Current theory and research. In: Stephens MAP, Crowther JH, Hobfall SE, Tennenbaum DL, editors. Stress and coping in later-life families. Washington, DC: Hemisphere; 1990. pp. 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS, Luong G, Sorkin DH, Newsom JT, Krause N. Ambivalent versus problematic social ties: Implications for psychological health, functional health, and interpersonal coping. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:912–923. doi: 10.1037/a0029246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smelser NJ. The rational and the ambivalent in the social sciences. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC, Cichy KE, Montoro-Rodriguez J. Impact of coping resources on the well-being of custodial grandmothers and grandchildren. Family Relations. 2015;64:378–392. doi: 10.1111/fare.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Chatters LM. Extended family and friendship support networks are both protective and risk factors for major depressive disorder, and depressive symptoms among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2015;203:132–140. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Brown RK. African American religious participation. Review of Religious Research. 2014;56:513–538. doi: 10.1007/s13644-013-0144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Mattis JS, Joe S. Religious involvement among Caribbean blacks in the United States. Review of Religious Research. 2010;52:125–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Tucker MB, Lewis E. Developments in research on Black families: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:993–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Hernandez E, Nicklett EJ, Taylor HO, Chatters LM. Informal social support networks of African American, Latino, Asian American, and Native American older adults. In: Whitfield KE, Baker TA, editors. Handbook of minority aging. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 417–434. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Chatters LM. Supportive relationships with church members among African Americans. Family Relations. 2005;54:501–511. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Mouzon DM, Nguyen AW, Chatters LM. Reciprocal family, friendship and church support networks of African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Race and Social Problems. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12552-016-9186-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HO, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, Chatters LM. Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health. 2016:1–18. doi: 10.1177/0898264316673511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cawthon RM, Smith TW, Light KC, McKenzie J, Carlisle M, Bowen K. Social relationships and health: Is feeling positive, negative, or both (ambivalent) about your social ties related to telomeres? Health Psychology. 2012;31:789–796. doi: 10.1037/a0026836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb M, Charbonneau AM, McCann RA, Gayle KR. Struggling and enduring with God, religious support, and recovery from severe mental illness. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67:1161–1176. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger GC. Social networks and gerontology. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 1996;6:285–293. [Google Scholar]