Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial dysfunction induces retrograde signaling, a pathway of communication from mitochondria to the nucleus that promotes a metabolic remodeling to ensure sufficient biosynthetic precursors for replication. Rtg2p is a positive modulator of this pathway that is also required for cellular longevity. This protein belongs to the ASKHA superfamily, and contains a putative N-terminal ATP-binding domain, but there is no detailed structural and functional map of the residues in this domain that accounts for their contribution to retrograde signaling and aging. Here we use Decomposition of Residue Correlation Networks and site-directed mutagenesis to identify Rtg2p structural determinants of retrograde signaling and longevity. We found that most of the residues involved in retrograde signaling surround the ATP-binding loops, and that Rtg2p N-terminus is divided in three regions whose mutants have different aging phenotypes. We also identified E137, D158 and S163 as possible residues involved in stabilization of ATP at the active site. The mutants shown here may be used to map other Rtg2p activities that crosstalk to other pathways of the cell related to genomic stability and aging.

Introduction

In cells of the baker´s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial dysfunction triggers the transcription of many nuclear genes [1]. This transcriptional activation is modulated by a pathway of communication from mitochondria to the nucleus termed retrograde signaling [2, 3]. Because S. cerevisiae can grow devoid of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), this pathway was extensively explored in this organism. A genome-wide approach in cells lacking mtDNA revealed that when retrograde signaling is activated cells undergo a metabolic remodeling by increasing peroxisomal and mitochondrial activities required to glutamate synthesis [4]. In wild type cells, when glutamate reach sufficient levels retrograde signaling transcriptional response is down-regulated [5]. As glutamate is necessary for the synthesis of several amino acids that include glutamine, which in turn is required for the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines, the communication from mitochondria to the nucleus ensures cell´s metabolism will provide enough biosynthetic precursors to guarantee its replication [3].

At the molecular level retrograde signaling was characterized by analyzing the transcriptional activation of the gene CIT2, that encodes the peroxisomal isoform of citrate synthase [6]. When mitochondrial activity and glutamate levels are low, a heterodimeric transcription factor complex composed of the proteins Rtg1p and Rtg3p translocate to the nucleus to activate the transcription of CIT2 [7]. Rtg1p and Rtg3p belong to the class of bHLH/Zip (basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper) transcription factors and bind to the element GTCAC (UASr) present in CIT2 promoter. The migration of this transcriptional complex requires the protein Rtg2p that associates to Mks1p, the negative modulator of the pathway [8, 9]. When mitochondrial activity and glutamate levels are high, Mks1p is released from Rtg2p, phosphorylated by an unknown kinase, and binds to 14-3-3 proteins Bmh1p/Bmh2p to execute its repression function on the pathway [9]. This keeps Rtg3p also phosphorylated, sequestered in the cytoplasm with Rtg1p, and CIT2 transcription at basal level [8].

The proteins Rtg2p and Mks1p form the minimal binary switch for the regulation retrograde signaling [10]. However, this pathway also crosstalks with other pathways of the cell such as the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway [11], the amino acid SPS (Ssy1-Ptr3-Ssy5) sensor system [12], and Ras signaling [13]. In particular, Rtg2p is a protein involved in several cellular activities that extend this crosstalk to the modulation of genomic stability and replicative aging.

Rtg2p is a protein involved in the expansion of trinucleotide repeats (TNR) in the nucleus, and also is present in the chromatin remodeling complex SLIK, and modulates the production of circles of rDNA. TNR instability is a tract involved in etiology of several diseases such as fragile X syndrome and Huntington’s disease. In S.cerevisiae rtg2Δ cells the expansion of CTG•CAG repeats showed a modest increase in rate, indicating a role for Rtg2p in genomic stability [14]. Besides this modulation of TNR expansion Rtg2p was also found in the nucleus bound to the SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5) histone acetyltransferase complex [15]. The Rtg2p-SAGA complex was named SLIK (SAGA-like), and it connects retrograde signaling to chromatin remodeling. Another important activity of Rtg2p is that it suppresses the production of extrachromosomal ribosomal-DNA (rDNA) circles that accumulate in yeast cells as they age [16]. This accumulation is also a form of genomic instability that reduces longevity and can even kill cells when in very high levels [17]. Indeed, rtg2Δ strain have lower replicative lifespan when compared to wild type [13]. The function of Rtg2p in the suppression of rDNA circles is observed only when the protein is not involved in propagating retrograde signaling [16], as yeast cells lacking mitochondrial DNA (petite ρ0) accumulate high levels of extrachromosomal rDNA episomes [18].

When retrograde signaling is transduced from mitochondria to the nucleus, it requires the putative ATP-binding domain located at the N-terminal of Rtg2p [9]. This domain is predicted to belong to the ASKHA (Acetate and Sugar Kinases, Hsp70, and Actin) protein superfamily [19], that includes acetate kinases, eukaryotic hexokinases, glycerol kinase and exopolyphosphatases, the heat shock protein hsp70, and actin. Multiple sequence alignment of this superfamily located in this domain five conserved regions termed PHOSPHATE 1, PHOSPHATE 2, CONNECT 1, CONNECT 2 and ADENINE that are characteristic of the ATP-binding fold, where the nucleotide makes favorable interactions with Mg2+ ion coordinated by conserved aspartate residues [20]. This common fold is used for inorganic polyphosphate hydrolysis in exopolyphosphatases and transfer of phosphoryl group from ATP in sugar and acetate kinases. Although mutations in this domain impair Rtg2p function in retrograde response there is no detailed structural and functional map of this protein that correlates its N-terminal domain with longevity. Here we use amino acid correlation analysis and site-directed mutagenesis to identify structural determinants in Rtg2p involved in retrograde signaling and in aging of S. cerevisiae. Our results demonstrate that the N-terminal domain is very important to the function of Rtg2p, both in longevity and retrograde response, locates amino acid residues that may be involved in coordination of Mg2+ ion and stabilization of ATP in the active site, and also show there are structural determinants in Rtg2p that control longevity in both dependent or independent manner of the communication from mitochondria to the nucleus.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains, culture media and growth conditions

All strains used in this study were derivatives of PSY142 (ρ+ MATα leu2 lys2 ura3::CIT2-LacZ). This strain has integrated the reporter CIT2-lacZ into the genome [9]. Cells were grown at 30°C in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose), YPR (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% raffinose), YPEG (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% ethanol and 2% glycerol), and YNBD (0.17% yeast nitrogen base, 0.5% (NH4)2SO4, 2% dextrose) with or without glutamate (final concentration 0.02%). Yeast cells were transformed as described previously [21]. To generate ρ0 strains, ρ+ cells were cultured for about 40 generations in liquid YPD medium supplemented with 25 μg/mL of ethidium bromide.

Construction of rtg2Δ strain

The strain carrying rtg2Δ mutation was constructed by one step gene disruption using T-urf13-KanMX cassette. To construct this cassette, T-urf13 gene was removed from YIpTW [22] and the 2.6 kb fragment cloned into HindIII site of YIplac128 [23] generating YIplac128-T-urf13 vector. The gene KanMX from the plasmid pYM-N18 [24] was removed with enzymes BamHI e SacI, and the 1.5 kb fragment cloned into YIplac128-T-urf13 to produce YIplac128-T-urf13-KanMX. To disrupt RTG2, the cassette T-urf13-KanMX was amplified by PCR with the oligonucleotides rtg2-T-urf13-KanMX-F and rtg2-T-urf13-KanMX-R (S1 Table), and the product transformed into yeast. Cells were selected o YPD containing geneticin (G418, 200 μg/mL). To confirm the integration within RTG2 locus genomic DNA was extracted from transformants and PCR reactions were performed with the oligonucleotides pairs rtg2-597up-F/KanB and KanC/rtg2-2217down-F.

Construction of RTG2 mutants by site-directed mutagenesis

The mutants alleles were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis performed by overlap extension PCR [25]. Briefly, for every mutant produced, two independent PCR reactions were performed with oligonucleotides pairs RTG2-F/mutagenic primer-R and mutagenic primer-F/RTG2-R (S1 Table). The products were submitted to gel electrophoresis, purified and combined in a PCR reaction without primers for 10 cycles. Finally, oligonucleotides RTG2-F and RTG2-R were added to proceed the reaction for 30 more cycles to generate the full length product with the desired mutation. PCR products were digested with BamHI and HindIII, and cloned into pGEM-3Zf(+). DNA sequencing was conducted to confirm the identity of the alleles.

Production of RTG2 mutants by gene replacement

The mutants cloned in pGEM3zf(+) were digested with BamHI and HindIII, transformed into rtg2Δ cells in the presence of lithium acetate [21], and selected on YPD plates containing methomyl (final concentration 6 mM) [22]. The DNA of several transformants was extracted to confirm the integration locus by PCR using the primers rtg2-597up-F/G337-R (S1 Table).

Auxotrophy assays and growth curves

Cells were grown until A600 = 1 and subjected to four serial dilutions (10−1, 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4) and an aliquot of 3μl of each dilution was deposited on YNBD plates with or without glutamate. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days and photographed to observe the differential growth of the mutants. Growth curves were constructed by measuring the A600 every hour in a microplate reader INFINITY PRO 200 (Tecan) with constant agitation of 320 rpm at 30°C for 24h.

β-galactosidase assays

Yeast cells were inoculated and grown in YNBD without glutamate until A600 0.6–0.8. The preparation of cell extracts and β-galactosidase assays were conducted as described previously [26]. All protein quantifications were performed according to Bradford [27]. Assays were conducted in triplicate, and independent experiments were carried out 2–3 times.

Yeast replicative lifespan

Replicative lifespan was determined as described previously [28]. Briefly, 50 virgin cells from an overnight culture were aligned on a YPD plate. After each cell division daugther cells were separated from their mothers. The number of daughter cells (generations) that each mother cell was able to bud until stop dividing was scored. During the day the cells were grown at 30°C, but incubated overnight at 4°C. Replicative lifespan assays were repeated at least twice and the Mann-Whitney test was used to measure the statistical significance.

Residue conservation and correlation analysis

Rtg2p is part of the Ppx-GppA protein family in PFAM (PF02541) that belongs to the ASKHA superfamily [29]. An alignment of 5020 sequences from Rtg2p homologs was obtained from PFAM [30]. These sequences were aligned and filtered, sequences with less than 80% coverage and 20% identity when compared to Rtg2p were excluded. After this procedure all sequences were compared to each other to remove similar sequences, if two sequences of the alignment had more than 80% identity, the smallest was removed. The resulting final alignment contained 581 sequences. Residue specific correlations and conservation were calculated using PFstats as described previously [31].

Molecular modeling

Molecular modeling of Rtg2p was performed in five independent servers, Robetta [32], SWISS-MODEL [33], Phyre2 [34], ESyPred3D [35] and I-TASSER [36] using default settings. The models obtained were validated by analysis of the Ramachandran diagram (S2 Table) and through Verify3D program (S3 Table) [37]. The best model showed 90.2% of residues in favorable regions in the Ramachandran diagram and more than 80% of coherence in Verify3D, that are indicators of good quality, and was obtained with Robetta server. Rtg2p model was refined with the 3Drefine for hydrogen bonding network optimization and atomic-level energy minimization [38]. The final model was deposited in the Protein Model Database (PMDB), accession code PM0080565. Figures were generated using PyMOL (https://www.pymol.org/).

Results

Rtg2p molecular model is a three domain structure similar to the crystal structure of a putative exopolyphosphatase of the ASKHA superfamily

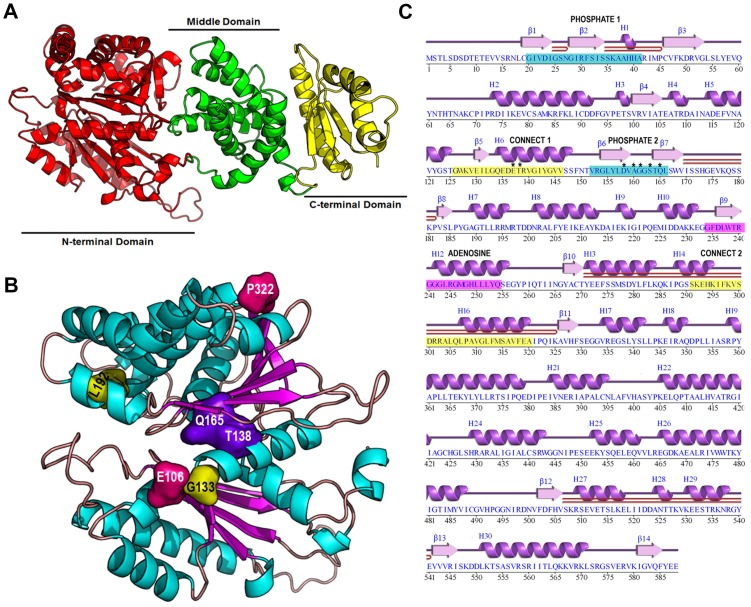

There is no published crystal structure of Rtg2p given the difficulties found in its purification from bacteria due to low solubility and partitioning into inclusion bodies [39]. For this reason, a 3D structure model of Rtg2p was generated in the server Robetta (Fig 1A) that used the crystal structure of the putative exopolyphosphatase of Agrobacterium fabrum (strain C58 / ATCC 33970) (PDB ID 3HI0) as a domain reference structure. The superposition of 440 structurally equivalent Cα atoms of both structures with a root mean square error of 2.3Å, as revealed by TopMatch [40], indicates the quality of our structural model of Rtg2p (S1 Fig).

Fig 1. Domain organization of Rtg2p structural model, location of coevolved residues, and ATP-binding motifs.

(A) Structure of the Rtg2p model obtained with the server Robetta [32]. Domain organization is indicated. (B) Location of residue communities obtained by DRCN on Rtg2p N-terminal Domain. Community 1 is represented in pink, community 2 in yellow, and community 3 in purple (C) Rtg2p ‘wiring diagram’ generated with PDBsum [41] highlighting the five sequence motifs involved in ATP binding (PHOSPHATE 1 and PHOSPHATE 2 (blue), CONNECT 1 and CONNECT 2 (yellow), and ADENOSINE(pink)). Residues on these motifs that were modified by site-directed mutagenesis are marked with an asterisk, and those making β-hairpins are represented by lines underneath.

Rtg2p is a 588 amino acids long protein whose modeled structure is organized in three domains (Fig 1A). The N-terminal domain (amino acids 1–352, Fig 1A, red domain) contains two smaller domains each with a βββαβαβα fold that is characteristic of the ASKHA superfamily [29] of proteins that include exopolyphosphatases and phosphotransferases. This domain corresponds to the Pfam family PF02451 of Pfam database. The middle domain (amino acids 353–496, Fig 1A, green domain) is an all α structure with six α helices that compose a six-helix claw, and a structural comparison with TopSearch [42] identified the catalytic core of the human cAMP phosphodiesterase PDE4B2B as its structural homolog. Finally, the C-terminal domain (amino acids 497–588, Fig 1A, yellow domain) contains a small β-sheet whose side chain residues make hydrophobic contacts with residues from Helix 30 on one side, and polar interactions with charged residues of two small helices on the other side. There is no protein domain assigned for both Middle and C-terminal domains of Rtg2p in any Pfam family. Indeed, for amino acids residue correlation analysis only the N-terminal domain could provide the alignment used in this work.

Decomposition of Residues Correlation Networks identified relevant functional residues in Rtg2p

The N-terminal domain of Rtg2p is important for its function. Mutations in this domain disrupt the transduction of mitochondrial signals of retrograde signaling [9]. In order to characterize this domain structurally we performed a bioinformatics analysis using the program PFstats. This analysis is termed Decomposition of Residues Correlation Networks (DRCN) [31], and it allows the identification of residues that coevolved in the protein. The input of PFstats is the alignment of the Pfam family PF02541, in which Rtg2p is a member, and the output is a set of communities of coevolved residues.

DRCN analysis of PF02541 family produced three communities of coevolved residues: E106-P322, L192-G133, and A138-E165 (Fig 1B). Rtg2p contains most of the residues that coevolved in the family except that T138 and Q165, which are in close contact, are different of those present in community 3 in equivalent positions, where the majority of the family members contain alanine and glutamate, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Conserved amino acid residues on equivalent positions of the ASKHA family members.

| UNIPROT code | Conserved residues in equivalent positions | |

|---|---|---|

| ASKHA family1 | A263 | E423 |

| RTG2_YEAST | T138 | Q165 |

| A9CJF9_AGRT5 | A125 | E152 |

| O67040_AQUAE | G120 | E148 |

| PPX_ECO57 | A122 | E150 |

| PPX_ECOLI | A122 | E150 |

| Q11YA9_CYTH3 | A114 | E143 |

| Q8G5J2_BIFLO | A118 | E149 |

1Conservation of the ASKHA family in the filtered alignment of DRCN analysis.

PFstats also produced a residue conservation analysis of the family. In this analysis only residues with conservation above 90% were considered (S4 Table). In particular, at the alignment position 418, in 99.8% of the sequences there is a glycine residue whereas Rtg2p contains alanine in an equivalent position, indicating a divergence of the family. It is also worth to mention that in Rtg2p primary structure the residues located at positions 204, 262, and 495 of the alignment, which are, respectively, threonine glutamate and glycine, are found in 100% of the sequences. In addition, some conserved residues and those of community 3 locate to two of the five sequence motifs involved in ATP binding, named PHOSPHATE 1, PHOSPHATE 2, CONNECT 1, CONNECT 2, and ADENOSINE [43]. The residues E137, and T138 (that coevolved with Q165 in community 3) are located in CONNECT 1 and D158, A160, G161, S163, and Q165 are located in PHOSPHATE 2 (Fig 1C). Taken together both coevolved residues (Fig 1B) and conserved residues (S2 Fig) located at the N-terminal domain at critical structural motifs are suitable candidates for site-directed mutagenesis to analyze the structural determinants of Rtg2p function.

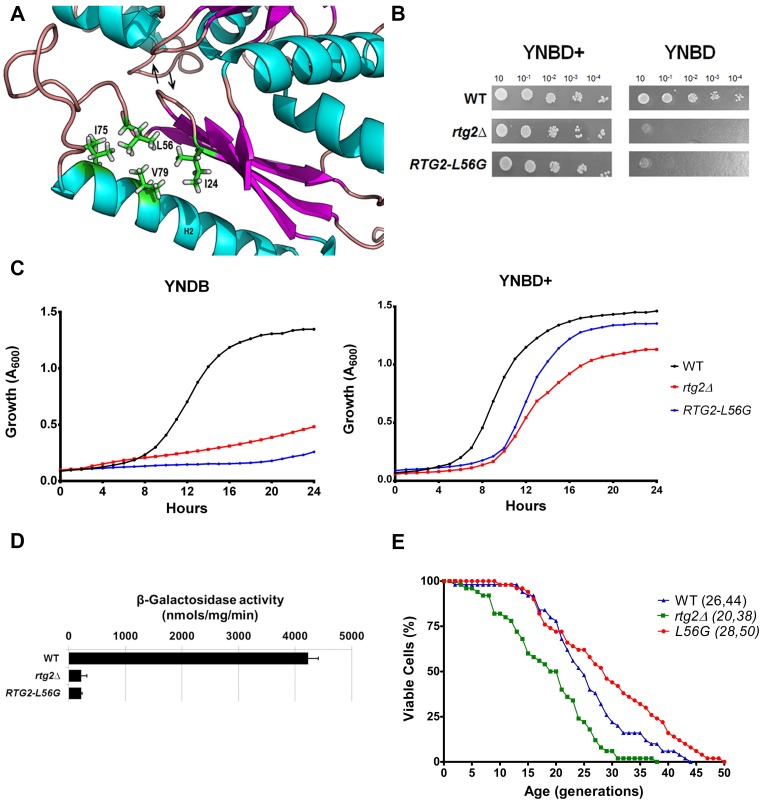

The mutation RTG2-L56G render yeast cells auxotrophic for glutamate, impairs retrograde signaling but extends replicative longevity

One of Rtg2p conserved residues is L56, which lies in a hydrophobic region in the vicinity of I24, I75 and V79 (Fig 2A). We hypothesized that L56 hydrophobic interactions would be necessary for protein activity, and to test this we generated the RTG2-L56G mutant by site-directed mutagenesis using overlap extension PCR and gene replacement. Cells with RTG2 gene disrupted (rtg2Δ) are glutamate auxotrophs [5]. If the mutant produced a similar auxotrophy phenotype it could be verified by growing cells in YNBD medium in the presence or absence of glutamate, and, indeed, RTG2-L56G mutant cells are glutamate auxotrophs, when compared to rtg2Δ and wild type parent (Fig 2B). In order to confirm the result of the spot assay, RTG2-L56G mutant cells were grown in liquid medium and the A600 measured for 24h. In the presence of glutamate RTG2-L56G mutant cells grew as well as the wild type, but a growth curve very similar to that of the rtg2Δ mutant was obtained when cells were grown in the absence of glutamate (Fig 2C), indicating a clear auxotrophy.

Fig 2. The mutation RTG2-L56G impair retrograde signaling, but extends replicative longevity.

(A) Location of L56 residue on Rtg2p protein structural model. ATP-binding loops are indicated with arrows. (B) Mutation L56G in Rtg2p render glutamate auxotrophy to yeast cells. Wild type, rtg2Δ, and RTG2-L56G strains were grown on YPD to A600 = 1 and four serial dilutions (10−1, 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4) were spotted on solid minimal media YNBD and YNBD+ (YNBD plus glutamate at 0.02%). The plates were incubated at 30°C for three days when photographs were taken. (C) Growth performance of strains on minimal liquid medium. Wild type, rtg2Δ and RTG2-L56G strains were grown on YPD until saturation, and diluted to A600 = 0.1 in 200 μL of either YNBD or YBND+. The cells were incubated at 30°C, 160 rpm, for 24 h and growth monitored in a INFINITY PRO 200 (Tecan) microplate reader. (D) L56G mutation impairs retrograde signaling activation on minimal medium. Wild type, rtg2Δ and RTG2-L56G strains were grown on YNBD medium until A600 = 0.6 and cell extracts were prepared to analyze CIT2-LacZ expression. β-galactosidase assays were performed in triplicate as described in the Materials and Methods section and the activity normalized by total protein concentration. (E) Replicative lifespan is extended in the mutant RTG2-L56G. Fifty cells of each strain were aligned on YPD and daughter cells were removed from mothers to construct survival curves from at least two independent experiments. The mean and maximum longevity are indicated between parentheses (mean, maximum). Statistical significance between samples is summarized in Table 2.

The strains used in this work contain CIT2-LacZ as a reporter integrated into the genome. CIT2 is a prototypical target gene of retrograde signaling that is induced when cells are grown in minimal medium YNBD, in the absence of glutamate [5]. This induction is impaired in rtg2Δ background. In order to analyze the effect of Rtg2p mutations on the activation of retrograde signaling and CIT2 transcription we measured the β-galactosidase activity of the reporter expressed in cells grown in YNBD. The mutant RTG2-L56G showed a clear phenotype of rtg2Δ cells, being unable to activate retrograde signaling as the parent wild type that showed a CIT2 expression higher than 30 fold (Fig 2D).

Prior work has shown that yeast cells lacking mitochondrial DNA (petite ρ0) have extended replicative lifespan (RLS) in glucose rich medium (YPD), when compared to the wild type (grande ρ+). This lifespan extension is abrogated by deletion of RTG2 [13]. This effect was strain-dependent, and displayed three possible phenotypes: extended longevity for YPK9 strain, shorter lifespan for SP1-1 and A364A strains, and no change for W303-1A. In order to determine which was the case of PSY142 we generated a ρ0 mutant and observed no difference between petite and grande lifespans (S3 Fig). Although we did not find a longevity extension dependent on RTG2 in our PSY142 petite strain, we did not exclude the possibility that our RTG2 mutants may interfere with yeast longevity. Surprisingly, when compared to the wild type grande strain, the mutant RTG2-L56G showed an increase in RLS (Fig 2E).

Taken together, these results suggest that Rtg2p L56 residue is important for protein function that is possibly accomplished by hydrophobic interactions of L56 with some of its neighbor residues (I24, I75 and V79). These interactions may determine the phenotypes of glutamate prototrophy and retrograde signaling activation observed in wild type cells. Unexpectedly, this single amino acid substitution had a positive effect by extending replicative longevity of the cells.

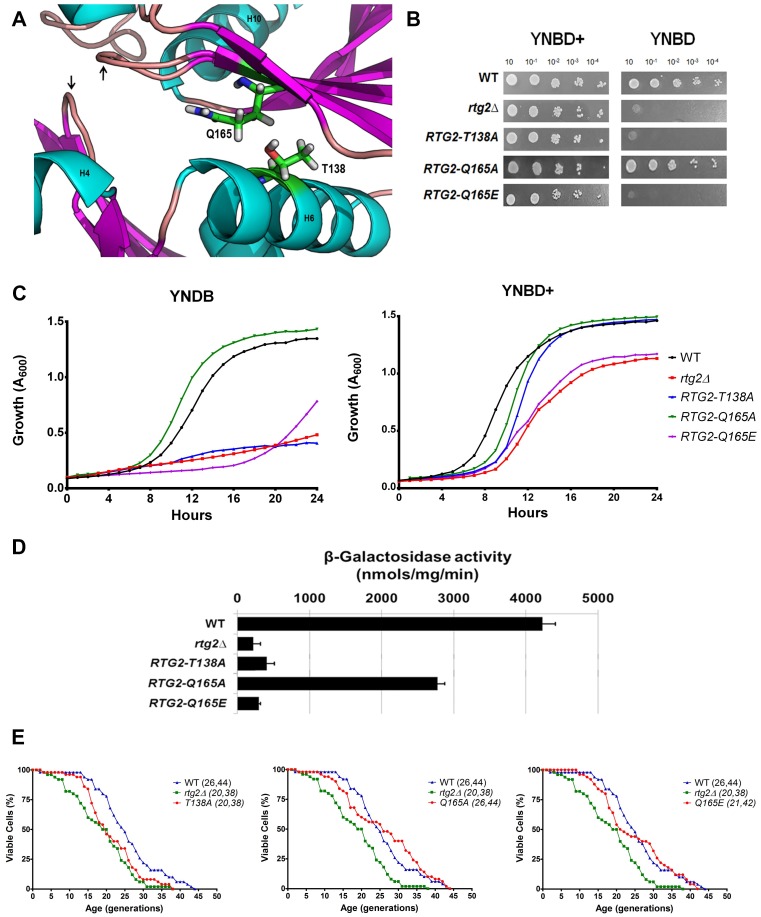

Interaction between the pair of coevolved residues T138 and Q165 determine Rtg2p function

The amino acids alanine and glutamate in positions 138 and 165 were found to be a coevolved pair in community 3 of our DRCN analysis of the Pfam family PF02541; and they are present in the majority of the sequences of the filtered alignment. However, Rtg2p contains threonine and glutamine in equivalent positions of the family (Table 1). By inspection of Rtg2p model structure we proposed that this divergence would be due to a necessary hydrogen bonding interaction between these two residues (Fig 3A), that is relevant for the protein function. To disrupt this interaction we generated the mutant RTG2-T138A that showed glutamate auxotrophy in both solid and liquid medium (Fig 3B and 3C), a very low CIT2 expression (Fig 3D), and decreased longevity in YPD (Fig 3E, left panel), all of which phenotypes comparable to rtg2Δ strain, that corroborated the hypothesis. Similar phenotypes were observed in the RTG2-Q165E mutant (Fig 3B–3D and 3E, right panel) The interaction between T138 and Q165 could be simulated by constructing the mutant RTG2-Q165A. We expected that this mutant would behave just like wild type cells because the hydrophobic interaction between the alanine residue and the methyl group of threonine would take place to stabilize Rtg2p structure locally. RTG2-Q165A cells are glutamate prototrophs, activate CIT2-LacZ gene expression (at 65% of the wild type levels) and show similar longevity to the wild type parent (Fig 3B–3D and 3E, middle panel). These results strongly indicate that T138 located at helix 6 and Q165 of strand 7 of the modeled structure may undergo a hydrogen bonding interaction required for Rtg2p protein function and reinforce their importance in the community 3 of coevolved residues.

Fig 3. Interaction of coevolved residues T138 and Q165 determine Rtg2p function.

(A) Location of T138 and Q165 residues on Rtg2p protein structural model. ATP-binding loops are indicated with arrows. (B) RTG2-T138A, RTG-Q165E strains but not RTG2-Q165A are glutamate auxotrophs. Glutamate auxotrophy assays were performed by spotting serial dilutions of cells on solid minimal media YNBD and YNBD+ (YNBD plus glutamate at 0.02%). (C) Growth performance of strains on minimal liquid medium. Wild type, rtg2Δ and mutants RTG2-T138A, RTG-Q165E, and RTG2-Q165A strains were grown on YPD until saturation, diluted to A600 = 0.1 in 200 μL of either YNBD or YBND+, and the growth was monitored in a INFINITY PRO 200 (Tecan) microplate reader as described in Materials and Methods section. (D) RTG2-Q165A strain that mimics T138 and Q165 interaction shows 65% of retrograde signaling activation on minimal medium. Wild type, rtg2Δ and point mutant strains RTG2-T138A, RTG-Q165E, and RTG2-Q165A were grown on YNBD medium until A600 = 0.6 and cell extracts were prepared to analyze CIT2-LacZ expression. β-galactosidase assays were performed in triplicate as previously described (see Materials and methods) and the activity normalized by total protein concentration. (E) Mutations RTG2-T138A (left panel) and RTG-Q165E (right panel) but not RTG-Q165A (middle, panel) show short lifespan. In at least two independent experiments, fifty cells of each strains were aligned on YPD and daughter cells were removed from mothers to construct survival curves. The mean and maximum longevity are indicated between parentheses (mean, maximum). Statistical significance between samples is summarized in Table 2.

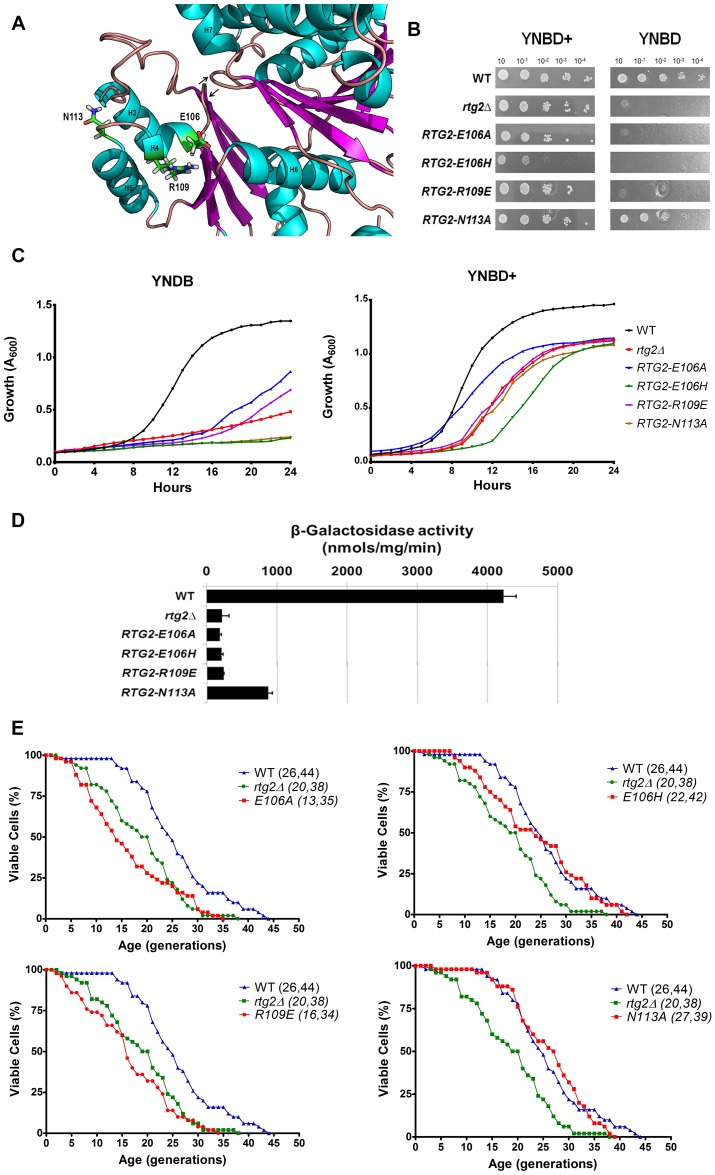

Rtg2p functions are impaired by mutations in surface residues E106, R109 but not N113

A set of conserved residues identified in our analysis are located at the surface of Rtg2p. E106 and R109 are located in a small 5 residue α helix between β4 and H5 (Fig 4A) and may be involved in polar contacts with one another to stabilize its helix turn. To test if this interaction is required for Rtg2p function, we generated the mutant E106A to remove the negative charge of this residue. As expected, RTG2-E106A mutant showed glutamate auxotrophy in both solid and liquid media (Fig 4B and 4C), CIT2 expression similar to the rtg2Δ strain (Fig 4D), and reduced RLS in YPD when compared to the rtg2Δ strain (Fig 4E, top left panel). When R109 was substituted by glutamate in RTG2-R109E mutant, the residue charge was changed to negative to promote repulsion with E106 residue charge, and the cells showed similar phenotypes as observed in RTG2-E106A mutant (Fig 4B–4D and 4E, bottom left panel). Likewise, in RTG2-E106H mutant, a possible charge repulsion with R109 resulted in cells auxotrophic for glutamate, unable to activate retrograde signaling and CIT2 transcription but with replicative longevity similar to that of wild type strain (Fig 4B–4D and 4E, top right panel). We speculate that the small helix in which E106 and R109 are located at the periphery of Rtg2p may interact with some other proteins or help Rtg2p form oligomeric structures [10].

Fig 4. Mutations in Rtg2p surface residues E106, R109 and N113 impair protein function.

(A) Location of E106, R109 and N113 residues on Rtg2p protein structural model. ATP-binding loops are indicated with arrows. (B) Mutant strains RTG2-E106A, RTG2-E106H, RTG-R109E but not RTG2-N113A are auxotrophic for glutamate. Auxotrophy assays were performed on solid minimal media YNBD and YNBD+ (YNBD plus glutamate at 0.02%) by spotting serial dilutions of cells that were incubated at 30°C for three days. (C) Growth performance of strains on minimal liquid medium. Wild type, rtg2Δ and point mutants strains were grown on YPD until saturation, diluted to A600 = 0.1 in 200 μL of either YNBD or YBND+, and growth was monitored as described in Materials and Methods. (D) RTG2-N113A mutant strain retains 21% of wild type CIT2-LacZ expression in minimal medium. Wild type, rtg2Δ and point mutants were grown on YNBD medium until A600 = 0.6 and cell extracts were prepared to analyze CIT2-LacZ expression. Triplicate β-galactosidase assays were performed and the activity normalized by total protein concentration. (E) Longevity assays show that lifespan of mutant strain RTG2-E106A (top left panel) is significantly reduced, which is not observed in RTG2-E106H (top right panel), RTG-R109E (bottom left panel), and RTG2-N113A (bottom right panel) strains. Fifty cells of each strain were aligned on YPD and daughter cells were removed from mothers to construct survival curves from at least two independent experiments. The mean and maximum longevity are indicated between parentheses (mean, maximum). Statistical significance between samples is summarized in Table 2.

Although these results were anticipated from our hypothesis, the mutant RTG2-E106H also showed a poor growth even in the presence of glutamate, suggesting an important role for cell viability. In the case of RTG2-N113A mutant, we also found unexpected results such as glutamate prototrophy in solid medium, a very long lag phase in liquid YNBD, CIT2 expression at 21% of wild type levels and no difference from the parent strain regarding to replicative longevity (Fig 4B–4D and 4E, bottom right panel). Altogether these results corroborate the possibility of interaction between E106 and R109 in Rtg2p small helix formed by residues 106–110, and indicates that the conserved residues may be relevant for some but not all functions of the protein, that may include augmenting viability.

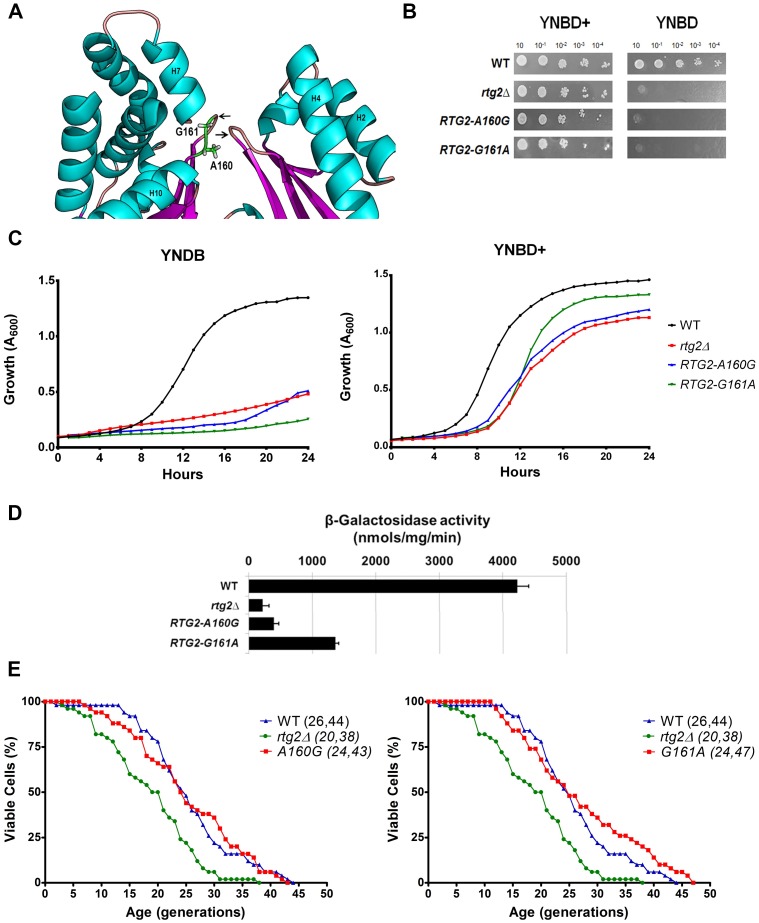

Residues A160 and G161 of Rtg2p ATP-binding loop are involved in retrograde signaling but are not determinants of yeast longevity

The active site of proteins in the ASKHA family is located in a cleft that also divides Rtg2p N-terminal domain. In this cleft, conserved loop structures are involved in ATP binding [43]. The loop between strands β6 and β7 contains an imperfect (D/N)XG motif characteristic of ASKHA phosphotransferases [29] and its side chain residues (D158, V159, A160, G161, G162 and S163) are possibly critical for phosphate binding. In our analysis we identified Rtg2p A160 as a divergent residue from the rest of family members, that contains a glycine in 99.8% of the sequences in an equivalent position (S4 Table). To investigate the reason of this difference we generated the mutant RTG2-A160G, and also RTG2-G161A given the strong conservation for G161 found in our analysis. These mutant strains showed glutamate auxotrophy in both solid and liquid media (Fig 5B and 5C), and RTG2-A160G was blocked in reporter gene expression whereas RTG2-G161A strain retained 32% of CIT2 expression observed in the wild type control (Fig 5D); and although the mutation G161A had an slightly difference in the longevity curve (Fig 5E, right panel), it was not significant (Table 2, and also WT<G161A one-tailed test p = 0.1532).

Fig 5. Mutation on residues A160 and G161 of Rtg2p ATP-binding loop decreases retrograde signaling, but not affect yeast longevity.

(A) Location of A160 and G161 residues on Rtg2p protein structural model. ATP-binding loops are indicated with arrows. (B) Both RTG2-A160G and RTG2-G161A strains show glutamate auxotrophy. Cells were grown on YPD to A600 = 1 and four serial dilutions were spotted on solid minimal media YNBD and YNBD+ (YNBD plus glutamate at 0.02%). The plates were incubated at 30°C for three days when photographs were taken. (C) Growth performance of mutant strains on minimal liquid medium are similar to that of rtg2Δ strain. Wild type, rtg2Δ and point mutants strains were grown on YPD until saturation, and diluted to A600 = 0.1 in either YNBD or YBND+, and growth curves were obtained in a INFINITY PRO 200 (Tecan) microplate reader, as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Expression of CIT2-LacZ reporter of the RTG2-G161A mutant is 32% of wild type parent expression. Wild type, rtg2Δ and point mutants were grown on YNBD medium, and cell extracts were prepared to analyze CIT2-LacZ expression. β-galactosidase assays were performed in triplicate and the activity normalized by total protein concentration. (E) Replicative lifespan of both mutant strains RTG2-A160G (left panel) and RTG2-G161A (right panel) are similar to WT. Fifty cells of each strain were aligned on YPD and daughter cells were removed from mothers to construct survival curves. The mean and maximum longevity are indicated between parentheses (mean, maximum). Statistical significance are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Statistical analysis of RLS experiments performed in YPD.

| Strain | WT | rtg2Δ |

|---|---|---|

| WT | ns | ** |

| rtg2Δ | ** | ns |

| L56G | ** | ** |

| E106A | ** | ns |

| E106H | ns | ** |

| R109E | ** | ns |

| N113A | ns | ** |

| E137A | ** | ns |

| T138A | ** | ns |

| D158A | ** | ns |

| A160G | ns | ** |

| G161A | ns | ** |

| S163A | ns | ** |

| Q165A | ns | ** |

| Q165E | ns | ** |

P-values were determined by Mann-Whitney test. Hypothesis test: WT column: mutant ≠ WT; rtg2Δ column: mutant ≠ rtg2Δ. ns: not significant.

** p <0.0001.

Collectively these results indicate that residues A160 and G161 are involved in the transmission of retrograde signaling, and have longevity in YPD comparable to the wild type strain when mutated, respectively, to glycine and alanine. In addition, although all ASKHA family members have glycine in the equivalent position of Rtg2p A160, this divergent residue is crucial for protein function in the later.

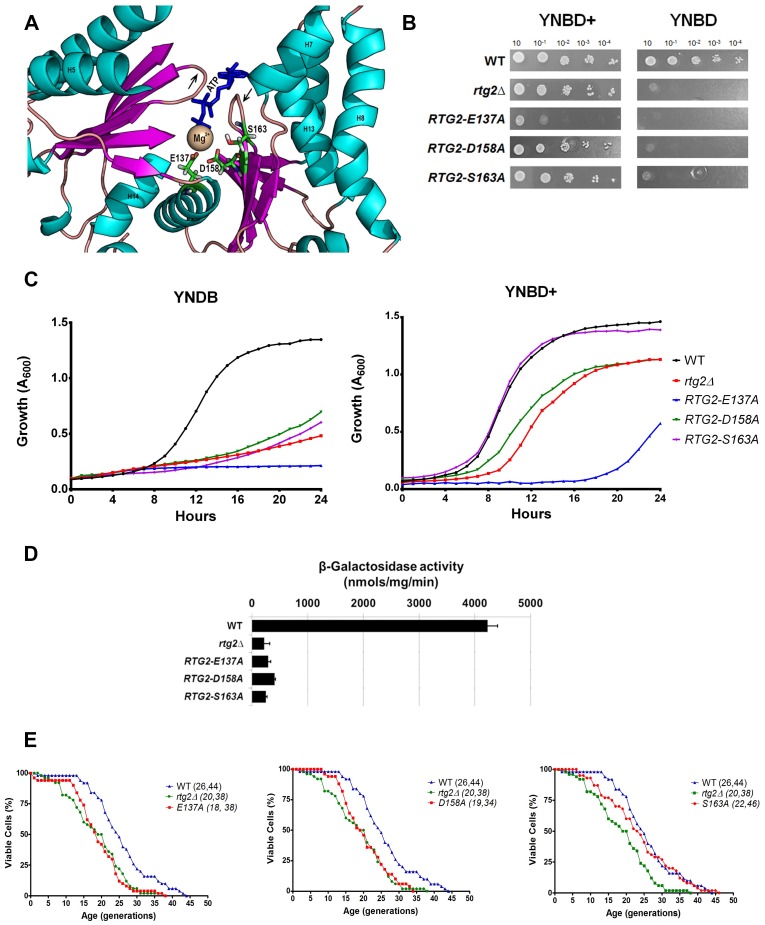

E137, D158, and S163 are probably residues involved in coordination of Mg2+ ion in the ATP binding site of Rtg2p

Previous work established the residues involved in Mg2+ ion coordination in the ATP-biding site of ASKHA family members. The two loop structures with (D/N)XG motif contribute with aspartate residues that act as ligands through water molecules that coordinate magnesium in an octahedral arrangement [20]. In agreement with that, our conserved residue analysis pointed to D158, that is located at the loop between strands β6 and β7, as a conserved residue important for Rtg2p function (Fig 6A). Moreover, it also found S163 located in the same loop and E137, a residue of helix 6 that is present in 100% of the sequences in the alignment (Fig 6A), as good candidates for mutagenesis and phenotypical analysis. To investigate the contribution of these residues to Rtg2p function we constructed the alanine mutants RTG2-D158A, RTG2-S163A, and RTG2-E137A, all of which resulted in cells auxotrophic for glutamate, blocked in retrograde signaling, but only RTG2-D158A and RTG2-E137A showed reduced longevity in YPD rich medium (Fig 6B–6E). The strain RTG2-S163A showed no difference in lifespan when compared to wild type cells (Fig 6E, left panel).

Fig 6. E137, D158, and S163 residues are likely involved in the coordination of Mg2+ ion at the ATP binding site of Rtg2p.

(A) Location of E137, D158, and S163 residues on ATP binding site of Rtg2p protein structural model. ATP-binding loops are indicated with arrows. (B) Mutations E137A, D158A, and S163A on Rtg2p cause glutamate auxotrophy to yeast cells. Glutamate auxotrophy assays were performed by spotting serial dilutions of cells on solid minimal media YNBD and YNBD+ (YNBD plus glutamate at 0.02%). (C) Growth performance of mutant strains on YNBD liquid medium are similar to that of rtg2Δ strain. Wild type, rtg2Δ and RTG2-E137A, RTG2-D158A, and RTG2-S163A strains were grown on YPD until saturation, diluted to A600 = 0.1 in either YNBD or YBND+, and incubated at 30°C, 160 rpm, for 24 h to monitor growth in a INFINITY PRO 200 (Tecan) microplate reader. (D) Retrograde signaling is not activated in RTG2-E137A, RTG2-D158A, and RTG2-S163A mutant strains. Wild type, rtg2Δ and point mutants were grown on YNBD medium until A600 = 0.6 and cell extracts were prepared to analyze CIT2-LacZ expression. β-galactosidase assays were performed as previously described (see Materials and Methods), and the activity normalized by total protein concentration. (E) Rtg2p mutations E137A (left panel) and D158A (middle panel) but not S163A (right panel) decrease the replicative lifespan of yeast. Fifty cells of each strain were aligned on YPD and daughter cells were removed from mothers to construct survival curves from at least two independent experiments. The mean and maximum lifespan are indicated between parentheses (mean, maximum). Statistical significance are summarized in Table 2.

Given the structural similarity of Rtg2p with other members of the ASKHA protein family, these data strongly suggest that residues D158, E137 and S163 are probably involved in polar interaction with water molecules that may coordinate Mg2+ ion in the active site of the protein. It also worth to mention that cells RTG2-E137A grew poorly even in the presence of glutamate (Fig 6B and 6C), a phenotype also observed in RTG2-E106H mutant (Fig 4B and 4C), that indicates this residue is important for cell viability.

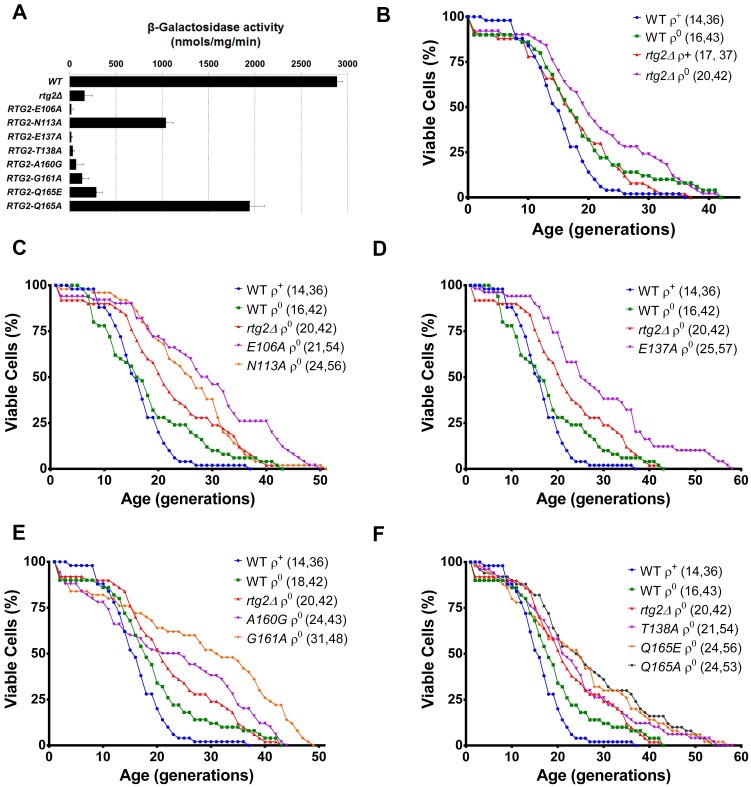

Some RTG2 point mutations extend the lifespan of PSY142 ρ0 cells grown in raffinose

Northern blot analyses of CIT2 expression revealed that in some strain backgrounds [13], and also in PSY142 [6], glucose represses the transcriptional activation of retrograde signaling. However, the increase in up to 30-fold of CIT2 expression of ρ0 cells compared to that of ρ+ parent can be uncovered in raffinose [5, 13], a nonrepressing fermentable carbon source. This difference in carbon source may promote a significant increase in RLS of ρ0 cells, such as that observed in SP1-1 strain, whose petite have shorter RLS in glucose and longer RLS in raffinose when compared to the WT ρ+ parent [13]. As retrograde signaling is activated in ρ0 cells grown in raffinose, and taking into account a possible difference in RLS that could be observed, we decided to address the effect of the carbon source on the expression of CIT2-LacZ, and also on the RLS of the thirteen mutants generated.

In raffinose, when compared to the ρ+, the lifespan of the PSY142 ρ0 strain is extended (Fig 7B), but the increase in RLS is not dependent on RTG2, because there is no significant difference in longevity between ρ0 and rtg2Δ ρ0 strains. A similar observation is made with RTG2-A160G and RTG2-T138A (Fig 7E and 7F), and in RTG2-L56G (S5B Fig), RTG2-E106H, RTG2-R109E (S5C Fig), RTG2-D158A (S5D Fig), and RTG2-S163A (S5E Fig) point mutations in ρ0 background. The expression of CIT2-LacZ in these mutants was also marginal (Fig 7A and S5A Fig). Nevertheless, some of the RTG2 point mutants showed a robust enhance in RLS compared to WT ρ0, as in RTG2-E106A ρ0 (Fig 7C), RTG2-E137A ρ0 (Fig 7D), RTG2-G161A ρ0 (Fig 7E), RTG2-Q165E ρ0 (Fig 7F) without significant activation of CIT2 transcription, whereas RTG2-N113A ρ0 (Fig 7C), and RTG2-Q165A ρ0. (Fig 7F) extended RLS and also showed, respectively, 36 and 67% of the expression observed in RTG2 ρ0.

Fig 7. When grown in raffinose, RTG2 point mutations in ρ0 background extend the lifespan when compared to PSY142 ρ0.

(A) RTG2-N113A and RTG2-Q165A mutants retain partial CIT2 expression. Petite strains, generated from wild type, rtg2Δ and RTG2 point mutants, were grown on YPR medium until A600 = 0.6, and cell extracts were prepared to analyze CIT2-LacZ expression. β-galactosidase assays were performed in triplicate as described in the Materials and Methods section and the activity normalized by total protein concentration. (B) PSY142 ρ0 strain shows extended RLS when compared to its ρ+ parent and no difference when compared to rtg2Δ ρ0. (C) RTG2-E106A ρ0 and RTG2-N113A ρ0 strains show enhanced longevity increase in RLS compared to WT ρ0. (D) RTG2-E137A, a residue involved in Mg2+ ion coordination, have significantly extended lifespan in ρ0 background if compared to WT ρ0. (E) The strain RTG2-G161A ρ0 but not RTG2A160G ρ0 robustly increases RLS when compared to WT ρ0 (F) Both strains RTG2-Q165E ρ0 and RTG2-Q165A ρ0 significantly increased RLS, but the mutant RTG2-T138A ρ0 is similar to WT ρ0. In replicative longevity assays, fifty cells of each strain were aligned on YPR and daughter cells were removed from mothers to construct survival curves from at least two independent experiments. The mean and maximum longevity are indicated between parentheses (mean, maximum). Statistical significance between samples is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Statistical analysis of RLS experiments conducted in YPR.

| Strains | WT | WT ρ0 | rtg2Δ ρ0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ns | * | *** |

| WT ρ0 | * | ns | ns |

| rtg2Δ | ns | ns | * |

| rtg2Δ ρ0 | *** | ns | ns |

| L56G ρ0 | * | ns | ns |

| E106A ρ0 | *** | ** | * |

| E106H ρ0 | ns | ns | *** |

| R109E ρ0 | ns | ns | ns |

| N113A ρ0 | *** | *** | * |

| E137A ρ0 | *** | *** | ** |

| T138A ρ0 | *** | ns | ns |

| D158A ρ0 | ns | ns | * |

| A160G ρ0 | * | ns | ns |

| G161A ρ0 | *** | ** | * |

| S163A ρ0 | * | ns | ns |

| Q165A ρ0 | *** | ** | * |

| Q165E ρ0 | *** | * | ns |

P-values were determined by Mann-Whitney test. Hypothesis test: WT column: mutant ≠ WT; WT ρ0 column: mutant ≠ WT ρ0. rtg2Δ ρ0 column: mutant ≠ rtg2Δ ρ0. ns: not significant.

* p <0.05,

** p <0.01,

*** p <0.001.

These observations suggest that lifespan extension of PSY142 ρ0 is dependent on carbon source and independent on RTG2 gene, as illustrated by a complete gene disruption or by some RTG2 point mutants. They suggest further that retrograde signaling is not required for lifespan extension in ρ0 cells grown in raffinose, and that retrograde response activation and RLS extension are not mutually exclusive, as show in RTG2-N113A ρ0 and RTG2-Q165A ρ0 mutants that retained partial activation of CIT2 transcription.

Discussion

Retrograde signaling, a pathway of communication from mitochondria to the nucleus, activates genes whose transcription is either independent or dependent on the action of Rtg1/3p transcription factor complex and Rtg2p protein (RTG pathway). Three conditions can activate the RTG pathway: ρ0 cells grown in rich or minimal medium with raffinose [1, 6], ρ+ cells grown in minimal medium under glutamate starvation (YNBD medium) [5], and ρ+ cells treated with the macrolide rapamycin, that inhibits the TOR pathway [9, 44]. Rtg2p is a key positive modulator required to activate retrograde signaling in response to such conditions in yeast. This activation is dependent on its N-terminal putative ATP-binding domain that is a member of the ASKHA superfamily of phosphotransferases. Although there is a wealth of information about this family, to date there is no extensive structural characterization of Rtg2p. In the present work, we performed residue conservation and correlation analysis, and generated thirteen point mutants by site-directed mutagenesis, to identify the determinants of Rtg2p in retrograde signaling and longevity. We constructed a 3D molecular model to locate the mutated residues on Rtg2p structure. This model allowed us to generate hypotheses that were tested to understand the contribution of the individual residues to the protein function. The majority of mutated residues affected the functions of the protein rendering cells auxotrophic for glutamate, unable to activate CIT2 gene expression and with rtg2Δ, wild type or long-lived phenotypes regarding to lifespan. This phenotype analysis together with our Rtg2p model located the residues of the protein required for its function in retrograde signaling (RTG pathway) and longevity.

CIT2-LacZ expression and glutamate auxotrophy were surrogate phenotypes used to study the function of Rtg2p in both metabolic reprogramming and retrograde response. Although the majority of mutants that are glutamate auxotrophs have decreased lifespan, it is important to mention that glutamate auxotrophy does not cause lifespan changes per se, as clearly observed in the mutant RTG2-L56G, that is auxotrophic for glutamate but showed an extension in lifespan in YPD. In addition, CIT2 expression is not a requirement for yeast longevity, as shown previously in two distinct genetic backgrounds, YPK9 and YSK365 [13]. Finally, the ability of the mutants to grow in rich medium YPD or YPR is not compromised by either RTG2 deletion or point mutation (S4 Fig), except for a mild effect observed in RTG2-E106H (S4A Fig).

Previous work showed an alignment of amino acid sequences of the GppA and Ppx proteins that included S. cerevisiae Rtg2p, and this analysis revealed the conservation of five motifs, related to the binding of ATP (PHOSPHATE 1, PHOSPHATE 2, CONNECT 1, CONNECT 2, and ADENOSINE) [19]. The conservation of such motifs suggests that the structural core of the family is present in Rtg2p. Indeed, Liu and co-workers have shown that mutations in the motifs PHOSPHATE 2 (G154D), ADENOSINE (G266V), and CONNECT 2 (G311D) of Rtg2p generated cells with reduced CIT2 expression and decreased ability of Rtg2p to bind the negative regulator Mks1p [9]. The residues found in the DRCN conservation analysis were also located in these motifs, E137 and T138 in CONNECT 1 and D158, A160, G161, S163, and Q165 (that coevolved with T138 in community 3, Fig 1B) in PHOSPHATE 2. Whereas most of this residues when mutated impaired retrograde signaling in YPD, Q165A and G161A mutations retained part of this activation as shown by CIT2 expression (respectively, Figs 3D and 5D). When Q165 is mutated to glutamate CIT2 expression level is similar to that of rtg2Δ strain. Therefore, the residues conserved in the N-terminus of Rtg2p, present in two out of five conserved ASKHA family motifs, depending on the chemical environment modification, may not impair retrograde signaling.

Remarkably, L56 is a conserved Rtg2p residue, that is not present in any of the five motifs related to ATP-binding, whose mutation to glycine confers the most dramatic extension in mean and maximum longevity in YPD rich medium (Fig 2E) with no activation of retrograde signaling (Fig 2B–2D). This is completely unexpected because most of mutations in Rtg2p N-terminal domain render cells with lifespan similar to rtg2Δ phenotype with pronounced decreased in longevity when compared to wild type parent. This mutant clearly shows there is a separation between retrograde signaling pathway and lifespan extension functions in Rtg2p. Indeed, one of the functions of Rtg2p is the suppression of extrachromosomal rDNA circles (ERCs) that accumulate in yeast cells as they age [16, 17]. In petite mutants that lack mitochondrial DNA the retrograde signaling is active and such cells accumulate high levels of ERCs [18]. This suggested that when involved in the induction of retrograde response Rtg2p is not able to counter ERC accumulation which causes cell death [16]. Therefore, the mutation L56G inactivated retrograde signaling but increased lifespan, possibly augmenting the interaction of Rtg2p with other proteins, and such complexes are able to inhibit ERC accumulation and promote longevity extension.

Among Rtg2p conserved residues found in DRCN analysis E137 (CONNECT 1), D158 and Q165 (PHOSPHATE 2) are also conserved in Escherichia coli exopolyphosphatase (equivalent residues E121, D143, and E150). E. coli Ppx is a protein that degrades long chains of ionorganic polyphosphate [29, 45, 46]. Mutations in its equivalent residues diminished the exopolyphosphatase activity to a residual level [29]. In Rtg2p, mutation in D158 generated a strain with very low CIT2 expression (Fig 6D), and mutation in E137 gave rise to cells with defects in both retrograde signaling and longevity maintenance (Fig 6D and 6E, left panel). The mutation Q165E produced a glutamate auxotroph strain, but the mutation Q165A grows as well as the wild type in YNBD without glutamate (Fig 3B and 3C). Both RTG2-Q165A and RTG2-Q165E mutants have similar lifespans, that are presumably due to movement restrain of a protein hinge (discussed below) and an increase in the amount of residues available to chelate magnesium ion in the ATP-binding site, respectively. Indeed, the mutation Q165E is in the vicinity of E137 and D158, that are located in positions know to be involved in Mg2+ biding and stabilization of ATP at the active site, in other members of the ASKHA protein family. Rtg2p is the only member of its family that contains a glutamine in this position (Q165) whereas all the others contain glutamate at the equivalent position, such as E. coli Ppx exopolyphosphatase (E150). This residue is critical for ATP binding of exopolyphosphatases and is commonly found in members of the ASKHA family, but S. cerevisiae found an adaptive advantage in Q165 for activating of retrograde signaling.

The community 3 of amino acids present in Rtg2p (T138 and Q165) diverge from those found in our analysis of the Pfam family PF02541 (alanine and glutamate on equivalent positions). After locating these residues in our Rtg2p structural model, we hypothesized that this divergence would be due to a hydrogen bonding interaction between these two residues (Fig 3A), that could be significant for protein function. Disruption of this interaction confirmed this hypothesis because the mutant RTG2-T138A showed glutamate auxotrophy (Fig 3B and 3C), diminished CIT2 expression (Fig 3D), and reduction of longevity in YPD (Fig 3E, left panel), phenotypes comparable to those of rtg2Δ strain. We also simulated the interaction between T138 and Q165 in the mutant RTG2-Q165A, that behaved just like wild type cells, because the hydrophobic interaction between the alanine residue and the methyl group of threonine probably stabilized Rtg2p locally in a similar way (Fig 3B–3D and 3E, middle panel). The interaction between T138 and Q165 in Rtg2p associates the helix 6 that contain residues of CONNECT1 with strand seven that belongs to the PHOSHATE2 motif. This restraint caused by Q165 is absent in all known structures of the family, that contain glutamate in the equivalent position, and, for this reason, are more mobile. In the ASKHA superfamily domain movements up to 30° required for catalysis are observed [43]. One example is the crystal structure of Aquifex aeolicus Ppx/GppA [47], that was studied from two crystals forms type I and type II, that revealed the protein has a structural flexibility previously described as "butterfly-like" cleft opening in other members of the family [48]. The domain configuration of these structures indicated the residues Y122 and A123 as a protein hinge region that allowed a rotational flexibility of 11.5° [47]. In Rtg2p, the equivalent residues are V140 and G141, and just beside this putative hinge lies the residue T138 that may interact with Q165, possibly to prevent the "butterfly-like" movement around the active site of the protein. We expect this restriction in mobility may result in a better proximity between the two ATP-binding loops of the protein, that are required for Rtg2p function. This exclusive characteristic of Rtg2p identified in the coevolved pair T138-Q165 indicates an evolutionary advantage, as the mutants RTG2-T138A and RTG2-Q165E that contain exactly the residues that coevolved in the family are not functional regarding the phenotypes analyzed in YNBD and YPD.

ATP binding and hydrolysis depend on the presence of Mg2+ and/or Mn2+ ions, is already found in structures of the members of the ASKHA superfamily such as Hsc70 [20]. Solvent exposed Mg2+ ions have a critical role in the active site of Hsc70 mediating the binding of ATP. In hexokinases, Mg2+ ions are coordinated by an aspartate, in Hsc70 and actin glutamate and glutamine participate of nucleotide binding [20, 29]. Given the importance of Mg2+ ions, our Rtg2p model was submitted to the server 3DLigandSite [49] that indicated residues with similar interaction with Mg2+ ions to stabilize ATP binding. Based in this structure, the conserved residues found by DRCN analysis and the known residues of the superfamily involved in this binding, we identified E137, D158 and S163 as three probable residues that may facilitate the binding of ATP in the active site of Rtg2p (Fig 6A). In this region we mutated individually these residues to alanine to prevent they act as ligands through water molecules to coordinate Mg2+ ion in an octahedral arrangement [20]. These mutations decrease dramatically the retrograde signaling to the levels observed in cells lacking RTG2 (Fig 6B–6D). These results together with the observation that physiological concentration of ATP dissociates the negative regulator of retrograde response Msk1p from Rtg2p [39] strengths the notion that the N-terminal of Rtg2p binds ATP, and we mapped the residues that may be involved in this interaction.

It was unexpected that RTG2-E137A and RTG2-E106H mutant strains grow poorly in minimal medium even in the presence of glutamate (Fig 6B). However, the strain RTG2-E106H showed no significant difference in lifespan from the wild type (Fig 4E, top right panel) whereas the strain RTG2-E137A showed a decrease longevity (Fig 6E, right panel). A possible structural explanation for this behavior is the fact that E137 is a residue involved in Mg2+ ion binding that is required for the function of Rtg2p involved in longevity. Similarly, D158 is also involved in magnesium binding and the mutant RTG2-D158A have decreased longevity, similar to that of rtg2Δ mutant (Fig 6E, middle panel). The residue E106 is not involved in Mg2+ ion binding, and it is located at the periphery of Rtg2p, in a small 5 residue α helix between β4 and H5 (Fig 4A). This helix may provide the surface for protein-protein interactions, possibly Rtg2p oligomerization [10] but contacts with other proteins are not excluded. Therefore, lack of appropriate coordination of magnesium ion is more detrimental to yeast longevity than loss of a possible interaction with other proteins at the periphery of Rtg2p.

Glucose represses the retrograde signaling activation and the lifespan extension observed in some ρ0 strain backgrounds [13], and it is also known to repress CIT2 expression in PSY142 ρ0 strain [6]. Here we show that glucose curtails the effect of longevity extension in these cells, because, in a nonrepressing carbon source such as raffinose, PSY142 ρ0 showed extended RLS compared to the grande parent (Fig 7B). In raffinose, regarding the expression of CIT2-LacZ, the mutant strains RTG2-N113A ρ0 and RTG2-Q165A ρ0 were the only to retain partial transcriptional activation of CIT2 (Fig 7A). The lifespan of these mutants (respectively, Fig 7C and 7F) and also that of RTG2-E106A ρ0 (Fig 7C), RTG2-E137A ρ0 (Fig 7D), RTG2-G161A ρ0 (Fig 7E), and RTG2-Q165E ρ0 (Fig 7F) were significantly extended compared to the WT ρ0 strain, whereas the other RTG2 mutant ρ0 strains showed no difference (Fig 7C–7F). These surprising findings show that raffinose extends the RLS of PSY142 ρ0 cells whose lifespan can be further extended in strains carrying the aforementioned mutations. The structural basis for these observations is rather complex as the mutations are spread over residues in the surface of the protein (N113 and E106), or located at the community 3 of coevolved amino acids (Q165), or involved in magnesium binding (E137). The production of strains with combinations of these mutations may help to determine if they act cooperatively, and this information may possibly integrate the actions of such mutant residues in a single mechanism. Finally, it is noteworthy that RTG2 deletion does not decrease the lifespan extension of PSY142 ρ0 compared to ρ+ cells, indicating a phenotype dependent on the genetic background, because it is contrary to previous observations in YPK9 and SP1-1 strains [13].

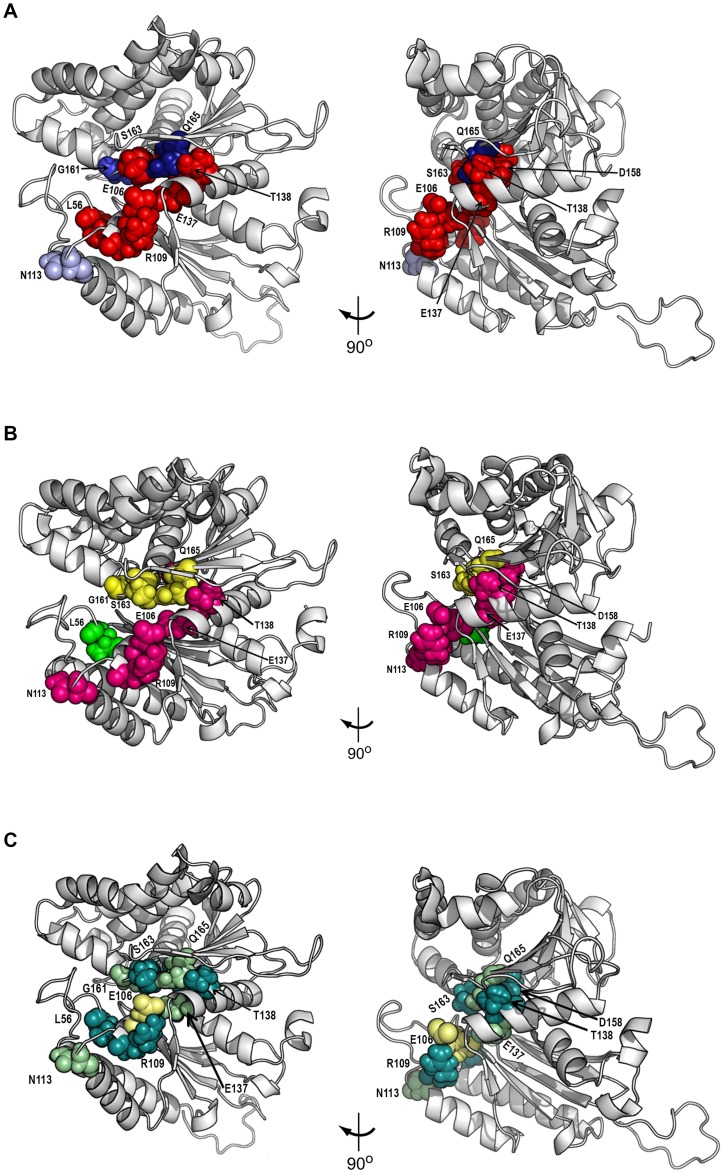

Altogether, the phenotypes analyzed of the mutants obtained by site-directed mutagenesis, and the structural 3D model generated, allowed to map on Rtg2p the determinants of retrograde signaling and longevity (Fig 8). Retrograde signaling is mediated by residues that surround Rtg2p N-terminal active site (Fig 8A, red residues). This is in contrast with previous findings whose residues (G154, G266 and G311) map to the opposite side of the domain, away from the active site [9]. These residues were not found in our conservation analysis that excluded positions with conservation below 90% in the filtered alignment. Interestingly, in three positions of Rtg2p it is possible to modulate the activity of the protein such that partial CIT2-LacZ expression is observed as in N113A, G161A and Q165A mutants that show, respectively 21, 32 and 65% of the wild type expression (Fig 8A, blue shades). Rtg2p is a protein involved in yeast longevity; in some strain backgrounds, lack of mitochondrial DNA extends lifespan, that is abolished by rtg2Δ mutation [13]. Although the lifespan extension in petites is not observed in PSY142 strain grown in YPD (S3 Fig), replicative lifespan assays conducted with our mutants identified the contribution of the individual residues to longevity. When these results are transported to the Rtg2p structural model it is possible to notice the distribution of the residues along the N-terminal domain divides it in three distinct regions (Fig 8B). In the first region are located the residues whose mutation is unable to interfere with Rtg2p function in longevity (E106H, N113A, A160G, G161A, S163A, Q165A, and Q165E) (Fig 8B, yellow surface). The second region contains residues whose mutation rendered cells with aging phenotype similar to rtg2Δ strain (E106A, R109E, E137A, T138A, and D158A) (Fig 8B, magenta surface), and the third region contains only the residue L56G, whose mutation produced long-lived cells (Fig 8B, green surface). The functional RLS map of the mutants grown in raffinose also showed three regions; one containing mutated residues that did not further extended the longevity of WT ρ0 (L56G, R109E, T138A, D158A, A160G, S163A) (Fig 8C, deepteal), a second region containing residues that significantly increased RLS (N113A, E137A, G161A, and Q165A) (Fig 8C, palegreen), and the residue E106 whose mutations E106H and E106A showed RLS similar to the WT ρ0 or an enhanced effect on RLS, respectively (Fig 8C paleyellow). This spatial distribution shows that, apparently, the function of Rtg2p related to longevity reside in a specific part of its N-terminus close to the ATP-binding site. To the best of our knowledge, this the first time the contribution of single Rtg2p residues to yeast aging is demonstrated, and it suggests that this approach could map other functional residues of Rtg2p involved in other pathways within the cell. Moreover, it is also the first report using the DRCN method extensively to map a protein involved in aging.

Fig 8. Functional mapping of Rtg2p residues involved in retrograde signaling and aging.

(A) Retrograde signaling determinants map. This map reflects the gene expression of the reporter CIT2-LacZ in the mutant strains grown on YNBD. Red color represents the residues whose β-galactosidase activity was similar to the rtg2Δ strain, in which the retrograde response is not activated. Blue color shades indicates the expression observed in RTG2-N113A, RTG2-G161A and RTG2-Q165A mutants that show, respectively 21, 32 and 65% of the wild type expression (the darker blue the higher the level of gene expression). (B) Map of Rtg2p lifespan determinants identified with RTG2 point mutants grown on YPD. N-terminal Rtg2p mutants are divided into three different groups in respect to their longevity phenotype. Mutants showing longevity similar to the wild type are shown in yellow, those similar to rtg2Δ in magenta and the long-lived mutants in green. (C) Map of Rtg2p lifespan determinants found in RTG2 ρ0 point mutants grown on YPR. N-terminal Rtg2p mutants are divided into two different groups in respect to their longevity phenotype. Mutants showing longevity similar to the WT ρ0 are shown in deepteal, those whose RLS was markedly increased are in palegreen; and in paleyellow; the residue E106 whose mutations are in both groups (E106H is long-lived whereas Q165E is short-lived). Residues are displayed in space filling representation and left panels are the same model as right panels rotated 90°clockwise around y axis.

Recently, the gene PHO84 was identified as the target of retrograde signaling responsible for lifespan extension in ρ0 cells [50]. Pho84p is a high-affinity inorganic phosphate transporter located at the plasma membrane [51, 52] and its expression is decreased in rtg2Δ ρ0 cells [4]. Although this finding directs the research on lifespan extension induced by retrograde signaling toward the proximal effector of longevity downstream of PHO84, Rtg2p is a protein involved in many cellular processes related to aging, and our structural map may provide the means to analyze more Rtg2p functions. One of these functions is the participation on the complex SLIK, a specialized form of the coactivator complex SAGA [15]. It was proposed that Rtg2p expands SAGA repertoire of gene modulation that includes several genes involved in stress response [53]. Our mutants could be used to probe the SAGA-Rtg2p association and their participation in chromatin remodeling. Likewise, the contribution of Rtg2p to the expansion/contraction of CTG•GAC triplets [14] may be studied by mutants designed by DRCN, and that may shed light to the mechanism shared in neurodegenerative diseases like Huntington´s disease. Another important trait of genomic instability modulated by Rtg2p activity is the formation of the extrachromosomal ribosomal-DNA (ERC) circles, that accumulate in cells with aging [16]. In yeast rtg2Δ background ERCs accumulate and eventually kill cells [17]. Because Rtg2p function that suppresses ERCs formation is observed only when the protein is not involved in propagating retrograde signaling [16], further studies of the mutants described here could be very informative, especially those that do not activate retrograde signaling but still extends longevity. The usefulness of the mutants could also be extended to the role of Rtg2p in the acidification of the vacuole in cells deficient in cardiolipin [54]. Elevation of vacuole pH is also strongly related to aging and mitochondrial dysfunction [55]. Overall, these works indicate that Rtg2p is very important for the longevity of S. cerevisiae, and its functional crosstalks with several other pathways of the cell could also be structurally mapped in Rtg2p by a similar approach shown here.

Supporting information

Structural superposition of Rtg2p Robetta model (red) and the crystal structure of the exopolyphosphatase of Agrobacterium fabrum (orange; cover structural similarity 67.6%; PDB ID 3HI0). Rtg2p unaligned regions are shown in blue. Superposition was performed with TopMatch (https://topmatch.services.came.sbg.ac.at/).

(TIF)

Conserved residues with conservation highest than 90% in PF02541 family were obtained by DRCN analysis. These residues were modified by site-directed mutagenesis, and are indicated in sticks representation in Rtg2p N-terminal structural model.

(TIF)

Fifty cells of each strain were aligned on YPD and daughter cells removed from mothers to construct survival curves from at least two independent experiments. Mean and maximum longevity are indicated between parentheses (mean, maximum). Statistical analyses were performed by Mann-Whitney test; p <0.895 [rho0] vs. [rho+].

(TIF)

Growth performance of strains on rich liquid medium YPD. Wild type, rtg2Δ, and RTG2 mutant strains were grown on YPD until saturation, and diluted to A600 = 0.1 in 200 μL of rich medium. The cells were incubated at 30°C, 160 rpm, for 24 h and growth monitored in a INFINITY PRO 200 (Tecan) microplate reader.

(TIF)

(A) RTG2 ρ0 point mutants show CIT2 expression comparable to that of rtg2Δ ρ0 strain. Petite strains, generated from wild type, rtg2Δ and RTG2 point mutants, were grown on YPR medium until to analyze CIT2-LacZ expression. β-galactosidase assays were performed in triplicate as described in the Materials and Methods section. RTG2 mutant ρ0 strains RTG2-L56G ρ0 (B), mutants in surface residues RTG2-E106H ρ0 and RTG2-E106A ρ0 (C), and mutants in putative residues involved in Mg2+ ion binding, RTG2-D158A ρ0 (D) and RTG2-S163E ρ0 (E) failed to increase RLS, when compared to WT ρ0. In RLS assays, fifty cells of each strain were aligned on YPR and daughter cells were removed from mothers to construct survival curves from at least two independent experiments. The mean and maximum longevity are indicated between parentheses (mean, maximum). Statistical significance between samples is summarized in Table 3.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

1Percentage of the residues with an averaged 3D-1D score ≥ 0.2.

(DOCX)

In red are positions that diverge from the conservation observed in the majority of the sequences f the alignment.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We are in debt to Dr. Mário Henrique de Barros and to Dr. Felipe Santiago Chambergo Alcalde for respectively providing the infrastructure and equipment for DRCN analysis and growth curve assays.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo (www.fapesp.br) to JRFJ.

References

- 1.Parikh VS, Morgan MM, Scott R, Clements LS, Butow RA. The mitochondrial genotype can influence nuclear gene expression in yeast. Science. 1987;235(4788):576–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butow RA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial signaling: the retrograde response. Mol Cell. 2004;14(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Z, Butow RA. Mitochondrial retrograde signaling. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:159–85. 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein CB, Waddle JA, Hale Wt, Dave V, Thornton J, Macatee TL, et al. Genome-wide responses to mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(2):297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z, Butow RA. A transcriptional switch in the expression of yeast tricarboxylic acid cycle genes in response to a reduction or loss of respiratory function. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(10):6720–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao XS, Small WC, Srere PA, Butow RA. Intramitochondrial functions regulate nonmitochondrial citrate synthase (CIT2) expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11(1):38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jia Y, Rothermel B, Thornton J, Butow RA. A basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcription complex in yeast functions in a signaling pathway from mitochondria to the nucleus. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(3):1110–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekito T, Thornton J, Butow RA. Mitochondria-to-nuclear signaling is regulated by the subcellular localization of the transcription factors Rtg1p and Rtg3p. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(6):2103–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Z, Sekito T, Spirek M, Thornton J, Butow RA. Retrograde signaling is regulated by the dynamic interaction between Rtg2p and Mks1p. Mol Cell. 2003;12(2):401–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira Junior JR, Spirek M, Liu Z, Butow RA. Interaction between Rtg2p and Mks1p in the regulation of the RTG pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 2005;354:2–8. 10.1016/j.gene.2005.03.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannattasio S, Liu Z, Thornton J, Butow RA. Retrograde response to mitochondrial dysfunction is separable from TOR1/2 regulation of retrograde gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(52):42528–35. 10.1074/jbc.M509187200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Sekito T, Epstein CB, Butow RA. RTG-dependent mitochondria to nucleus signaling is negatively regulated by the seven WD-repeat protein Lst8p. Embo J. 2001;20(24):7209–19. 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirchman PA, Kim S, Lai CY, Jazwinski SM. Interorganelle signaling is a determinant of longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1999;152(1):179–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharyya S, Rolfsmeier ML, Dixon MJ, Wagoner K, Lahue RS. Identification of RTG2 as a modifier gene for CTG*CAG repeat instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2002;162(2):579–89. Epub 2002/10/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pray-Grant MG, Schieltz D, McMahon SJ, Wood JM, Kennedy EL, Cook RG, et al. The novel SLIK histone acetyltransferase complex functions in the yeast retrograde response pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(24):8774–86. Epub 2002/11/26. 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8774-8786.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borghouts C, Benguria A, Wawryn J, Jazwinski SM. Rtg2 protein links metabolism and genome stability in yeast longevity. Genetics. 2004;166(2):765–77. Epub 2004/03/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinclair DA, Guarente L. Extrachromosomal rDNA circles—a cause of aging in yeast. Cell. 1997;91(7):1033–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conrad-Webb H, Butow RA. A polymerase switch in the synthesis of rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(5):2420–8. Epub 1995/05/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koonin EV. Yeast protein controlling inter-organelle communication is related to bacterial phosphatases containing the Hsp 70-type ATP-binding domain. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19(4):156–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurley JH. The sugar kinase/heat shock protein 70/actin superfamily: implications of conserved structure for mechanism. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:137–62. Epub 1996/01/01. 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.001033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:87–96. Epub 2002/06/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glab N, Petit PX, Slonimski PP. Mitochondrial dysfunction in yeast expressing the cytoplasmic male sterility T-urf13 gene from maize: analysis at the population and individual cell level. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236(2–3):299–308. Epub 1993/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gietz RD, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74(2):527–34. Epub 1988/12/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janke C, Magiera MM, Rathfelder N, Taxis C, Reber S, Maekawa H, et al. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast. 2004;21(11):947–62. Epub 2004/08/31. 10.1002/yea.1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heckman KL, Pease LR. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(4):924–32. Epub 2007/04/21. 10.1038/nprot.2007.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rupp S. LacZ assays in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:112–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. Epub 1976/05/07. [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinclair DA. Studying the replicative life span of yeast cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1048:49–63. Epub 2013/08/10. 10.1007/978-1-62703-556-9_5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarado J, Ghosh A, Janovitz T, Jauregui A, Hasson MS, Sanders DA. Origin of exopolyphosphatase processivity: Fusion of an ASKHA phosphotransferase and a cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase homolog. Structure. 2006;14(8):1263–72. Epub 2006/08/15. 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D279–85. Epub 2015/12/18. 10.1093/nar/gkv1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bleicher L, Lemke N, Garratt RC. Using amino Acid correlation and community detection algorithms to identify functional determinants in protein families. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e27786 Epub 2011/12/30. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim DE, Chivian D, Baker D. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W526–31. Epub 2004/06/25. 10.1093/nar/gkh468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(2):195–201. Epub 2005/11/23. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10(6):845–58. Epub 2015/05/08. [pii] 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. 10.1038/nprot.2015.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert C, Leonard N, De Bolle X, Depiereux E. ESyPred3D: Prediction of proteins 3D structures. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(9):1250–6. Epub 2002/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40 Epub 2008/01/25. 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luthy R, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D. Assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Nature. 1992;356(6364):83–5. Epub 1992/03/05. 10.1038/356083a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhattacharya D, Cheng J. 3Drefine: consistent protein structure refinement by optimizing hydrogen bonding network and atomic-level energy minimization. Proteins. 2012;81(1):119–31. Epub 2012/08/29. 10.1002/prot.24167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang F, Pracheil T, Thornton J, Liu Z. Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Is a Candidate Signaling Molecule in the Mitochondria-to-Nucleus Retrograde Response Pathway. Genes (Basel). 2013;4(1):86–100. Epub 2014/03/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sippl MJ, Wiederstein M. Detection of spatial correlations in protein structures and molecular complexes. Structure. 2012;20(4):718–28. Epub 2012/04/10. [pii] 10.1016/j.str.2012.01.024. 10.1016/j.str.2012.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laskowski RA. PDBsum new things. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D355–9. Epub 2008/11/11. 10.1093/nar/gkn860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiederstein M, Gruber M, Frank K, Melo F, Sippl MJ. Structure-based characterization of multiprotein complexes. Structure. 2014;22(7):1063–70. Epub 2014/06/24. 10.1016/j.str.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bork P, Sander C, Valencia A. An ATPase domain common to prokaryotic cell cycle proteins, sugar kinases, actin, and hsp70 heat shock proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(16):7290–4. Epub 1992/08/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sekito T, Liu Z, Thornton J, Butow RA. RTG-dependent mitochondria-to-nucleus signaling is regulated by MKS1 and is linked to formation of yeast prion [URE3]. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(3):795–804. 10.1091/mbc.01-09-0473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akiyama M, Crooke E, Kornberg A. An exopolyphosphatase of Escherichia coli. The enzyme and its ppx gene in a polyphosphate operon. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(1):633–9. Epub 1993/01/05. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rangarajan ES, Nadeau G, Li Y, Wagner J, Hung MN, Schrag JD, et al. The structure of the exopolyphosphatase (PPX) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 suggests a binding mode for long polyphosphate chains. J Mol Biol. 2006;359(5):1249–60. Epub 2006/05/09. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kristensen O, Laurberg M, Liljas A, Kastrup JS, Gajhede M. Structural characterization of the stringent response related exopolyphosphatase/guanosine pentaphosphate phosphohydrolase protein family. Biochemistry. 2004;43(28):8894–900. Epub 2004/07/14. 10.1021/bi049083c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuler H. ATPase activity and conformational changes in the regulation of actin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1549(2):137–47. Epub 2001/11/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wass MN, Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. 3DLigandSite: predicting ligand-binding sites using similar structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W469–73. Epub 2010/06/02. 10.1093/nar/gkq406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang JC, Stumpferl SW, Tiwari A, Qin Q, Rodriguez-Quinones JF, Jazwinski SM. Identification of the Target of the Retrograde Response that Mediates Replicative Lifespan Extension in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2016;204(2):659–73. Epub 2016/07/31. 10.1534/genetics.116.188086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bun-Ya M, Nishimura M, Harashima S, Oshima Y. The PHO84 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes an inorganic phosphate transporter. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11(6):3229–38. Epub 1991/06/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wykoff DD, O'Shea EK. Phosphate transport and sensing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2001;159(4):1491–9. Epub 2002/01/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jazwinski SM. Rtg2 protein: at the nexus of yeast longevity and aging. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005;5(12):1253–9. Epub 2005/08/16.] 10.1016/j.femsyr.2005.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]