Abstract

Submucosal esophageal hematoma is an uncommon clinical entity. It can occur spontaneously or secondary to trauma, toxins, medical intervention, and in this case, coagulopathy. Management of SEH is supportive and aimed at its underlying cause. This article reports an 81-year-old male patient with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and hypertension that develops a submucosal esophageal hematoma.

Keywords: Esophageal, Submucosal hematoma, Intramural dissection, Intramural hemorrhage

Clinical scenario

An 81-year-old male presented to the Emergency with chief complaints of chest pain and dysphagia. History of presenting illness revealed the chest pain was precipitated suddenly while eating lunch. It was a severe 10/10 tearing type of pain that radiated to the upper abdomen. Past medical history included cardiac arrhythmias (ie, ventricular fibrillation and arrest treated with an implanted defibrillator) and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) (with recent history of transfusion with platelets). Additionally, past medical history also included hypertension and hyperlipidemia controlled with ongoing medication (ramipril and atorvastatin, respectively).

Upon physical examination, patient was retching and appeared to be pale and diaphoretic. His respiratory rate was around 32/min. His blood pressure was 164/80 mm Hg (left arm); however, the rest of the vitals signs were within normal range (HR: 84/min, SpO2: 98, temperature: 36.5°C). Abdominal examination showed guarding, and respiratory and cardiac examinations was normal.

An ECG and blood test for serum cardiac enzymes were reported to be negative, confirming the etiology as a noncardiac chest pain. A complete blood count showed hemoglobin levels of 114 g/L (ref. 130–180 g/L) and platelet count of 68 × 109/L (ref. 150–400 ×109/L). Coagulation workup showed INR-PT of 0.9 (ref. 0.8–1.2) and APTT of 22 (ref. 22–35). Isolated thrombocytopenia aided in making the partial diagnosis of an episode of ITP. Blood chemistry appeared unremarkable, and liver function test was within normal range.

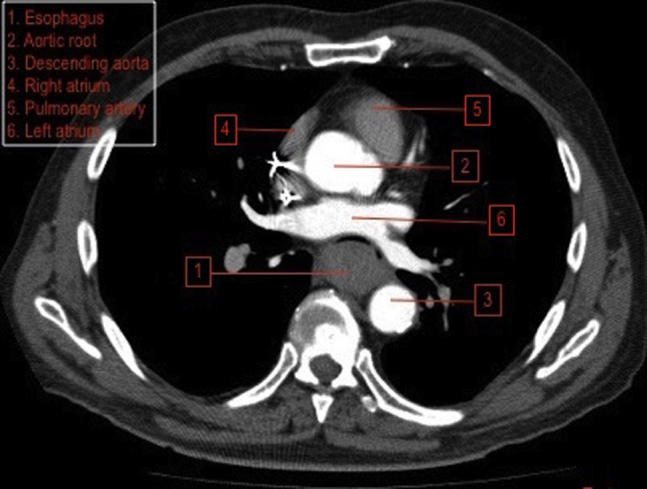

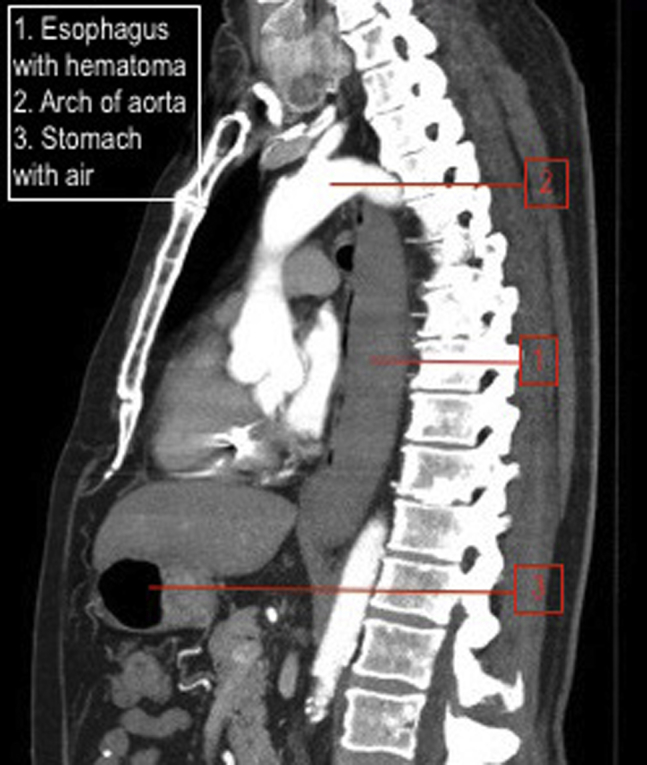

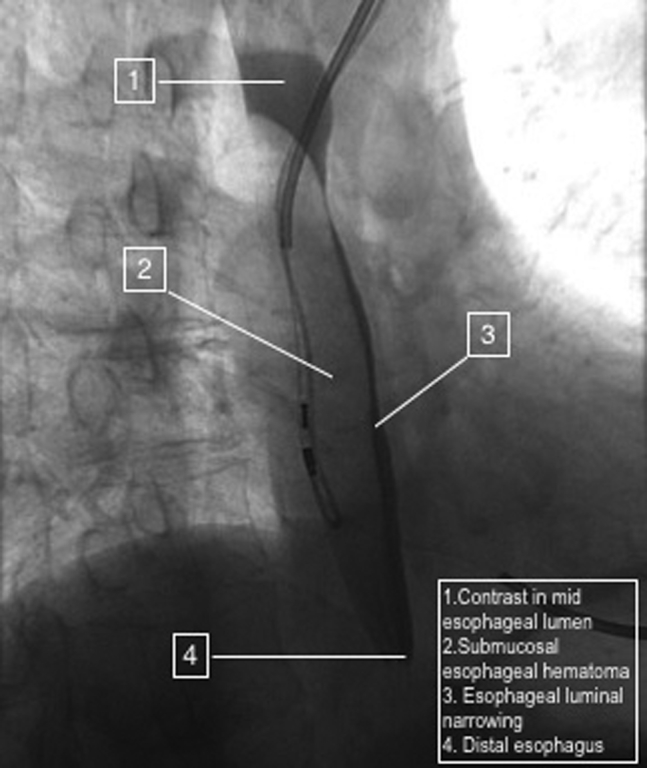

ITP, anemia, and the clinical presentation of the patient raised concerns of possible aortic dissection, submucosal esophageal hematoma (SEH), Boerhaave syndrome, and Mallory-Weiss tear, etc. This patient was therefore arranged for a CT exam of the chest before and following intravenous contrast. CT findings revealed a 17-cm long segment of homogeneous, soft tissue like density in the mid-to-distal esophagus with smooth eccentric configuration causing luminal narrowing (Figs. 1 and 2). The maximal esophageal wall measures approximately 26 mm in thickness. This brought upon the suspicion of a SEH. A subsequent single contrast upper gastrointestinal study was performed. It showed a large eccentric luminal narrowing caused by a mural wall compression of the mid-to-distal esophagus, confirming the submucosal hematoma (Fig. 3). It appeared to a stage III manifestation of SEH, as the lesion compressed the esophageal lumen [1].

Fig. 1.

CT axial view.

Fig. 2.

CT sagittal view.

Fig. 3.

Upper gastrointestinal contrast study.

The patient was managed with supportive therapy with intravenous fluids, morphine, and prochlorperazine. The ITP was managed with a combination of IV immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone. No platelet transfusion was performed. This was followed by continuous treatment with prednisone and danazol on an out patient basis with a follow-up with the family doctor and hematologist. Meanwhile, the SEH, known to resolve spontaneously, was treated with supportive therapy with pantoprazole.

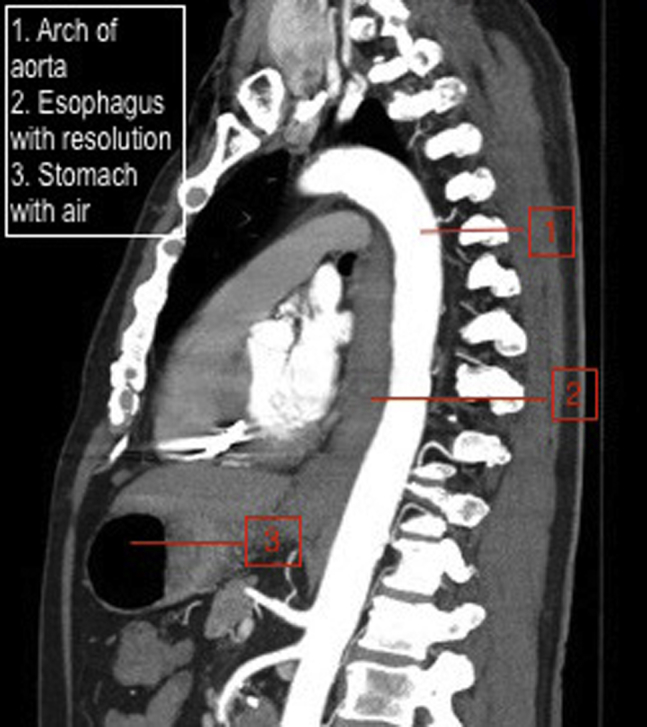

Thereon, the SEH was treated conservatively. A 3-month follow-up CT showed complete resolution of the lesion (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Follow up CT after 3 months.

Discussion

In a nutshell, this was a case of an 81-year-old male with an exacerbation of his previously diagnosed chronic ITP manifesting as a SEH.

ITP is an autoimmune hemorrhagic disease whose exact cause is still unknown. It is, however, stipulated that abnormal antibodies against immunoglobulin G bind to the platelet membrane causing the platelets to be eliminated in the spleen [2]. ITP is classified as acute and chronic; acute ITP occurs particularly in children (peak age 2–5 years), while chronic is seen mostly in adults (peak age 20–50 years). Further, adult ITP affects females more than males (3:1) [3]. As the case in question is an 81-year-old male patient, a thorough investigation of instigating causes was warranted (ie, underlying bone marrow pathologies like myelodysplasias, leukemias [4], etc.) in order to distinguish the true primary etiology.

The diagnosis was made by exclusion. The presence of thrombocytopenia with normal coagulation studies, along with no history of drugs or other comorbidities that could potentially precipitate ITP, and the past medical history of ITP further supported the diagnosis. The condition mostly presents as purpura, bleeding from mucous membranes, and hemorrhage as the most serious complication (intracranial hemorrhage being the most frequent cause of death) [5]. This patient presented with a SEH, a rare entity, which occurred secondary to the proposed ITP, yet again, making it a unique case not only demographically, but also in its clinical manifestation.

In literature, SEH is also known as intramural hemorrhage or intramural dissection. It is a rare form of esophageal insult that may occur spontaneously or due to iatrogenic reasons, trauma, or toxic ingestion. Risk factors include states of increased esophageal pressure (ie, vomiting), female sex, and coagulopathy [6]. Presence of hypertension may also play a role in the mechanism of this form esophageal injury and is worth further review of literature and research. It presents itself mostly with all or a combination of the following symptoms: sharp retrosternal pain radiating toward the abdomen, epigastric pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, and hematemesis [6], [7]. Before arriving at the diagnosis of SEH, alarming cardiovascular and gastrointestinal causes need to be investigated and excluded.

A CT scan is a nontraumatic and an appropriate initial modality to investigate the patients’ complaint. It aids in the detection of the extent of the disease and is also helpful in excluding other disorders. In SEH, a CT scan can reveal the intramural soft tissue density as an acute hematoma. According to luminal involvement, SEH is classified into stages. Stage I is characterized by an isolated hematoma, while in stage II, the hematoma is surrounded by tissue edema. When a hematoma with edema compresses the esophageal lumen, it becomes stage III. And, in stage IV, the esophageal lumen is obliterated by the hematoma, edema, and clot formation [1]. In this case, the CT findings along with the clinical presentation had raised suspicion of an SEH of stage III. To further confirm the provisional diagnosis, a single contrast esophageal swallowing study was done using a water-soluble contrast. It is noted that an upper GI endoscopy can also be performed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes [8]. It may allow direct visualization of luminal narrowing, mucosal friability, and the presence of other lesions. Endoscopic esophageal ultrasonography may also be useful in difficult cases [6]. SEHs, known to resolve spontaneously, are treated conservatively and are followed up clinically. If clinically warranted, an appropriate CT or esophagogram can be helpful to evaluate the evolution/resolution of the SEH.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Hong M., Warum D., Karamanian A. Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma secondary to anticoagulation and/or thrombolysis therapy in the setting of a pulmonary embolism: a case report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7(2):1–10. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v7i2.1210. [Accessed September 2, 2015 from PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panitsas F., Theodoropoulou M., Kouraklis A., Karakantza M., Theodorou G., Zoumbos N. Adult chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is the manifestation of a type-1 polarized immune response. Blood. 2004;103(7):2645–2647. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogarty P.F. Chronic immune thrombocytopenia in adults: epidemiology and clinical presentation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23(6):1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashman F., Hill M., Saba G., Diaconis J. Esophageal hematoma associated with thrombocytopenia. Gastrointest Radiol G. 1978;3(1):115–118. doi: 10.1007/BF01887049. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01887049#page-1 Department of Radiology, University of Maryland Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland U.S.A.; and Department of Radiology, The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman M., Dyne P. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Medscape. 2015 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/779545-overview; accessed 30.06.15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung J., Müller N., Weiss A. Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma: case report and review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20(4):285–286. doi: 10.1155/2006/764714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonheur J., Talavera F., Katz J., Cerulli M. Esophageal hematoma. Medscape. 2014 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/174496-overview; accessed 15.06.16. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagai T., Torishima R., Nakashima H., Uchida A., Okawara H., Suzuki K., Sato R., Murakami K., Fujioka T. Spontaneous esophageal submucosal hematoma in which the course could be observed endoscopically. Intern Med. 2004;43(6):461–467. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.461. Department of Gastroenterology, Oita Kouseiren Tsurumi Hospital, Beppu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]