Abstract

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor is a rare benign tumor that affects most commonly children and young adults. In the lung, it comprises less than 1% of all neoplasms. The authors describe the clinical, radiological, and pathologic features of 2 cases of incidentally discovered pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors.

Keywords: Lung neoplasms, Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, Solitary pulmonary nodule, Thoracic radiography, Multidetector computed tomography

Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare, indolent, and benign tumor that typically affects children and young adults with no gender predilection [1], [2]. Its clinical and radiologic manifestations are variable and most commonly nonspecific, being frequently found incidentally. Diagnosis is difficult based on imaging alone, and surgical biopsy is often required [1]. We describe the clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features of 2 incidentally discovered pulmonary IMTs.

Case 1

A 12-year-old boy presented at another institution with a weeklong history of cough. A chest radiograph was initially performed, and a solitary pulmonary nodule in the right hemithorax was reported. Physical examination was unremarkable, and there was no relevant past medical or family history. Laboratory tests were within normal limits, except for a slightly elevated C-reactive protein of 15.4 mg/L (normal values <3.0 mg/L). Tuberculin skin test (Mantoux) was negative. He was treated with a course of antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanate) with symptomatic improvement, after which he was referred to our institution for pulmonary nodule workup.

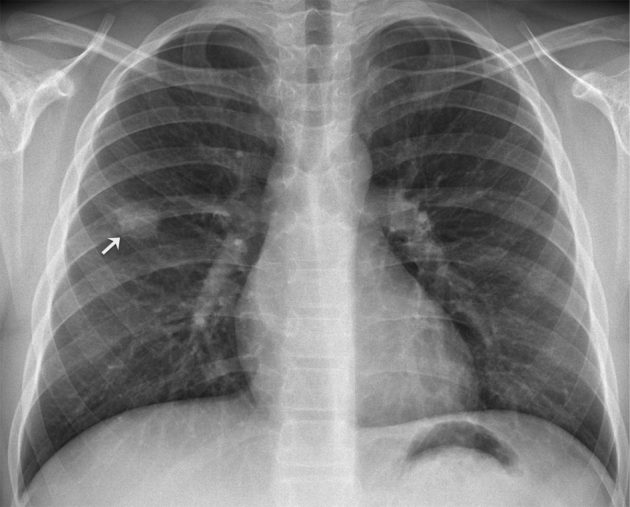

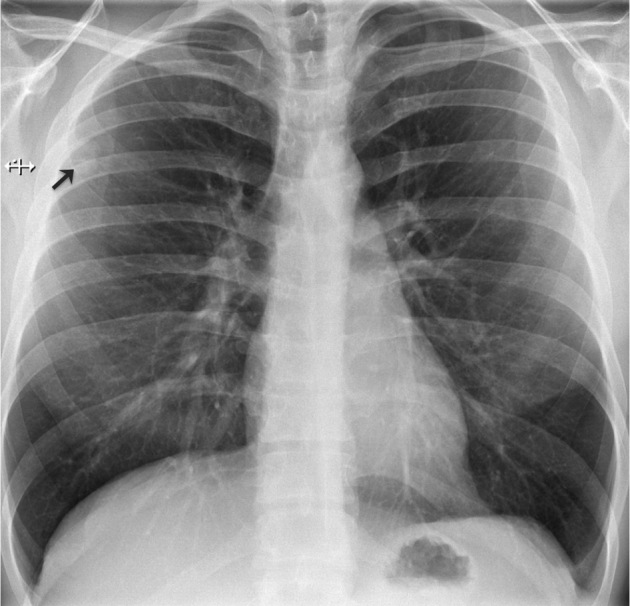

A chest radiograph was repeated at our institution, 1 month after the patient presented to medical care (Fig. 1). A 3-cm solitary pulmonary nodule was present in the right middle lung field. Some spiculation was noted. There were no other nodules, consolidation, or evidence of pleural effusion, and no hilar lymphadenopathy was present.

Fig. 1.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph depicts a solitary pulmonary nodule in the middle third of the right hemithorax (arrow). Slight spiculation of its contour can be appreciated.

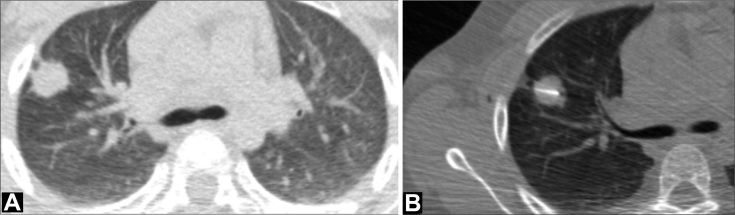

The patient was referred for computed tomography (CT)–guided transthoracic lung biopsy (Fig. 2). CT examination confirmed the presence of a spiculated mass in the right upper lobe. No other pulmonary abnormalities were present. Transthoracic core needle (20G) biopsy was performed without complications.

Fig. 2.

Axial CT image, lung window setting (A) shows a peripheral spiculated 3 cm mass in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe. Some pleural tails can be noted extending to the visceral pleura. Core needle biopsy of the lung nodule was performed under CT guidance (B). CT, computed tomography.

Pathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen was inconclusive, but the diagnosis of a hamartoma was suggested (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Histological specimen from the core-biopsy (hematoxylin-eosin [H-E], ×200 magnification). Fibromyxoid tissue and duct-like spaces lined by cuboidal epithelium without atypia. This was insufficient to provide a definitive diagnosis.

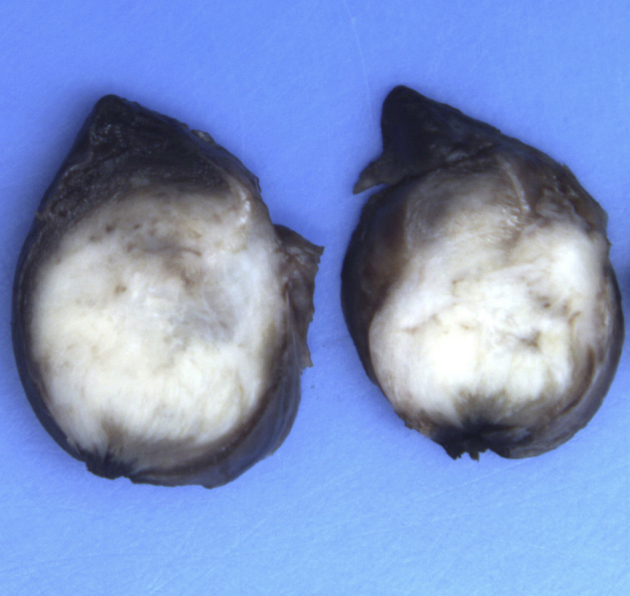

At multidisciplinary meeting, it was decided to perform a surgical excisional lung biopsy. The surgical specimen measured 60 × 25 × 17 mm, weighted 8 g, and was occupied by a firm, circumscribed mass with a fleshy white cut surface measuring 17 mm (Fig. 4). Three-millimeter thick sections were harvested from the lesion and embedded into paraffin blocks after routine tissue procedures.

Fig. 4.

Macroscopic specimen after partial lung resection. This sagittal section shows that the tumor was well circumscribed with a fleshy white cut surface.

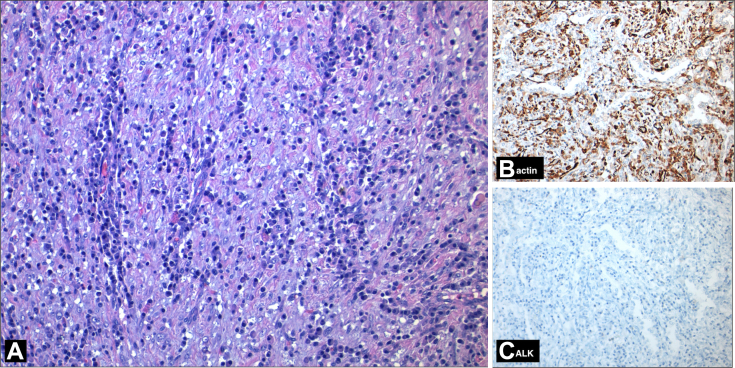

The material was examined under the light microscopy. Sections showed a fascicular pattern tumor. Tumor elements consisted of cells with oval- and spindle-shaped nucleus with indistinct borders, thin chromatin distribution, and inconspicuous nucleoli. There was no cytological atypia or mitosis. These cells were accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate composed mainly of plasma cells and lymphocytes. Immunohistochemical studies showed diffuse expression of smooth muscle actin in spindle cells, and there was no staining with antibodies against anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and CD34 (Fig. 5). The final pathologic diagnosis was IMT.

Fig. 5.

Photomicrograph (H-E stain, ×200 magnification, panel A) shows spindle cells arranged in fascicles mixed with inflammatory cells. Immunohistochemical studies (IHC, ×200 magnification, panels B and C) show reactivity for actin and negative reactivity of tumor elements for ALK. H-E, hematoxylin-eosin.

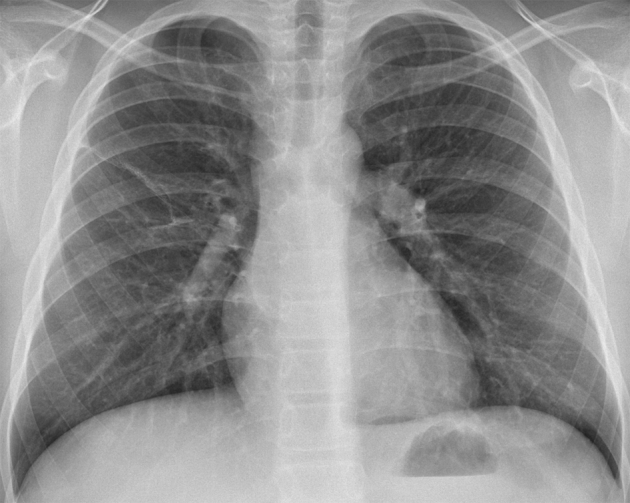

The postoperative period was unremarkable, and after 6 months of follow-up, there was no radiological evidence of persistent or recurrent disease (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph 6 months after surgical excision shows no signs of recurrence. A linear atelectasis can be seen in the right lung.

Case 2

A 39-year-old male was referred to our hospital after an incidental solitary pulmonary nodule was detected on routine chest radiograph. The patient was a nonsmoker with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus (diagnosed at 28 years of age) and allergic rhinitis. He was asymptomatic, and physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests revealed hyperglycemia (285 mg/dL) and slight leukopenia (3.44 × 109/L; normal range: 4.0–11.0 × 109/L).

A chest radiograph was repeated at our institution (Fig. 7). A solitary pulmonary nodule was noted at the periphery of the right upper lung field. No other nodules, consolidation, or pleural effusion was reported.

Fig. 7.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph denotes a solitary pulmonary nodule in the upper right lung field (arrow). The nodule is slightly obscured by the right scapula.

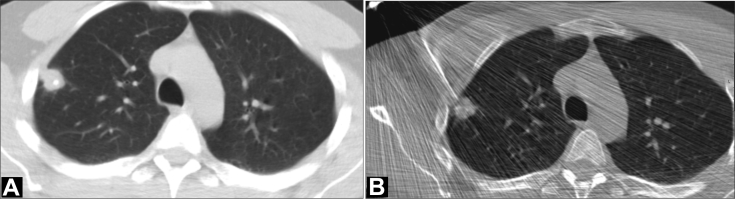

The patient was referred for transthoracic lung biopsy (Fig. 8). CT evaluation at the time of biopsy confirmed the presence of a nodule in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe. No other parenchymal or pleural abnormalities were evident. Transthoracic core needle (18 G) biopsy was performed, and no significant complications were reported apart from a small right pneumothorax that spontaneously resolved.

Fig. 8.

Axial CT image, lung window setting (A) denotes a peripheral 28-mm nodule in the right upper lobe. Punctate eccentric calcification is apparent. Transthoracic core needle biopsy was performed (B). CT, computed tomography.

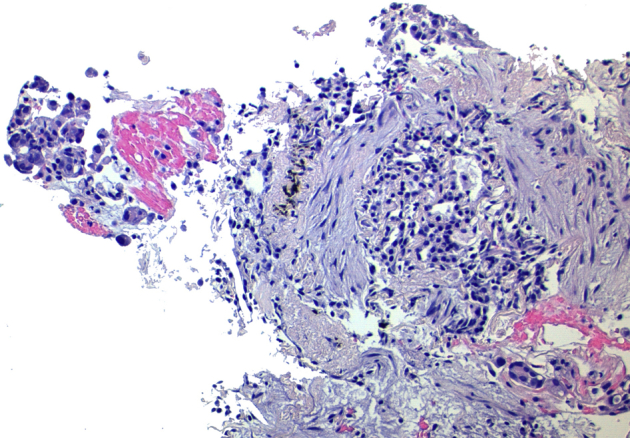

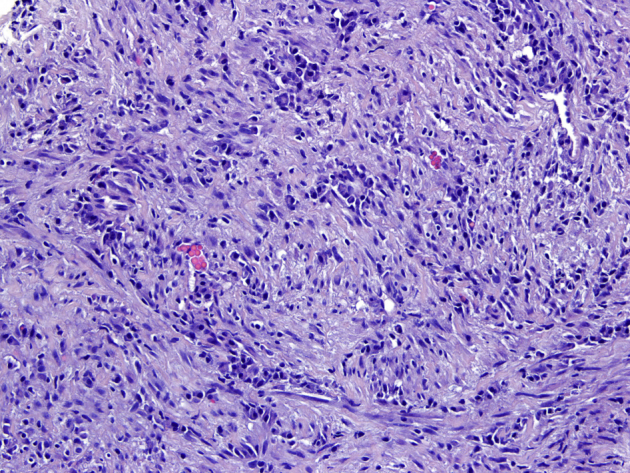

Pathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen was suggestive of IMT (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Histological specimen from the core-biopsy (hematoxylin-eosin [H-E], ×200 magnification). A fascicular pattern of spindle cells and inflammatory infiltrate is seen.

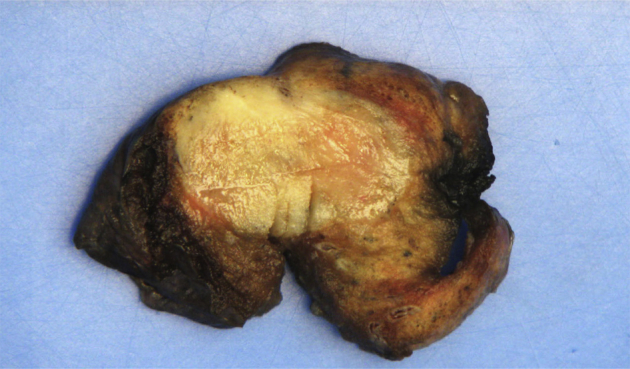

The patient was referred to cardiothoracic surgery consultation, and atypical resection was performed. The surgical specimen was occupied by a firm, well-circumscribed mass with a fleshy white cut surface (Fig. 10). Three-millimeter thick sections were harvested from the lesion and embedded into paraffin blocks after routine tissue procedures.

Fig. 10.

Macroscopic cross-section after partial lung resection. A well-circumscribed, fleshy white-tan nodular lesion is shown.

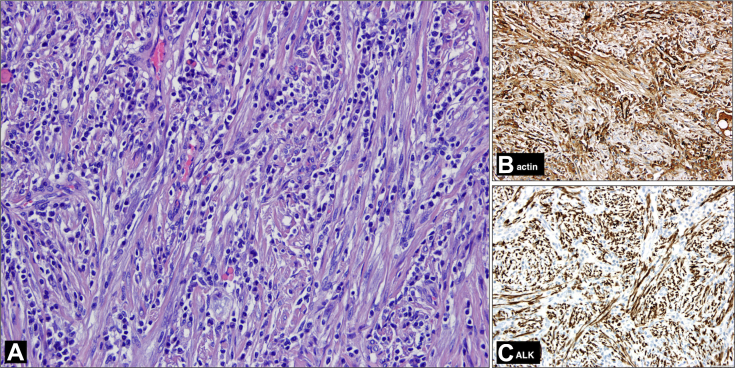

The histological examination revealed a spindle cell tumor, with expansive growth and fascicular pattern. Tumor cells had oval nuclei, with vesicular chromatin, without overt atypia, and amphophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic index was low, and there was no necrosis. Occasional dystrophic calcifications were observed. It was remarkable for the presence of a moderate inflammatory infiltrate composed mainly of plasma cells and lymphocytes. In the immunohistochemical study, it was observed expression in the spindle cells of actin and ALK and lack of expression of CD34. The final pathologic diagnosis was IMT (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Photomicrograph (H-E stain, ×200 magnification, panel A) shows a compact, spindle cell tumor, with fascicular pattern and a distinct inflammatory infiltrated composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells. In immunohistochemical studies (×200 magnification, panels B and C), spindle cells expressed actin and ALK. H-E, hematoxylin-eosin.

Discussion

IMT was first described in the lung in 1939 [3], but extrapulmonary sites, including the head and neck, the heart, the gastrointestinal tract, mesentery, retroperitoneum, hepatobiliary system, genitourinary tract, and soft tissues, can also be involved [1], [3], [4]. Its etiology is still unknown although an exaggerated immune response to a foreign or viral antigen has been proposed [1], and in some instances, it has been associated with trauma, minor surgery, or concomitant malignancy [3].

The lung is the most frequent anatomic location for IMTs, which represent about 0.04%–1% of all lung neoplasms [2]. In children, IMT is the most common primary lung mass, representing almost 50% of benign pulmonary tumors seen in pediatric patients [3]. The disease may manifest with cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, and dyspnea, although it is usually asymptomatic [2]. On chest radiography, IMTs appear as a solitary, well-circumscribed, lobulated, peripherally located lesion, most commonly in the lower lobes [2], [4], [5], [6]. In the presented cases, both nodules were solitary and peripherally located, but both arose in the right upper lobes. Also, some radiographic worrisome features were present in our pediatric patient (slight spiculation and pleural tails). Regarding size, in a series of 61 pulmonary IMTs, the mean lesion diameter was 4.4 cm [5]. Calcification is not uncommon and is seen more frequently in children than adults [2], [4]. Interestingly, in our cases, calcification was seen in the adult but not on the pediatric patient. Presentation as multiple lung masses is uncommon (5%) [5]. When IMT presents as a solitary pulmonary nodule, the main radiologic differential diagnosis includes a primary or secondary neoplasm, hamartoma, hemangioma, chondroma, and pulmonary sequestration [3]. In young children, round pneumonia should also be considered. At CT, IMTs have a variable appearance, but most appear as heterogeneous enhancing lesions [2], [3]. Atelectasis, pleural effusion, and locally aggressive features (vascular, bronchial, or mediastinal invasion) may rarely be present [3], [7]. Although seldom performed, on magnetic resonance imaging, these lesions present with intermediate signal intensity on T1 and hyperintensity on T2-weighted images [5].

Macroscopically, IMTs are firm, well-circumscribed, nonencapsulated, yellowish gelatinous masses [2], [6]. Calcification, hemorrhage, and necrosis are uncommon [2].

Histologically, IMTs consist of a variable mixture of fibroblasts, granulation tissue, fibrous tissue, and inflammatory cells [6]. Three histologic subtypes are recognized: (1) loosely arranged plump or spindle myofibroblasts in an edematous background with abundant blood vessels and mixed inflammatory infiltrate, simulating granulation tissue, or reactive process, (2) compact fascicular spindle cell proliferation, with a distinctive inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocyted, plasma cells, and eosinophils, and (3) scar-like proliferation of plate-like collagen with lower cellularity and a relatively sparse inflammatory infiltrate [3]. In any case, immunohistochemistry demonstrates the polyclonal nature of plasma cells, though IMTs have been rarely found to be associated with IgG4-sclerosing disease [2], [4]. About half of IMTs have a clonal abnormality overexpressing ALK, suggesting a neoplastic process [4]. In our case, there was expression of ALK in tumor cells only on the adult patient. Clinical, radiologic, and pathologic characteristics of both cases are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical, radiologic, and pathologic characteristics of the two cases.

| Sex | Age | Symptoms | Nodule location | Calcification | Transthoracic biopsy diagnostic | Actin positivity | ALK positivity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Male | 12 | Upper respiratory infection | Right upper lobe | No | No | Yes | No |

| Patient 2 | Male | 39 | Asymptomatic | Right upper lobe | Yes (punctate, eccentric) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

The main differential diagnoses on pathology are organizing pneumonia, lymphoma, sarcoma, and fibrosis, but the pathologist is usually able to eliminate a malignant neoplastic process [1], [6].

Although cases of spontaneous regression have been reported, complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice, as IMTs can be locally aggressive and recurrence after surgery is well documented [1], [3], [4]. Prognosis is excellent after radical surgical excision with 5-year survival rates of 91.3% [1], [6].

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Hammas N., Chbani L., Rami M., Boubbou M., Benmiloud S., Bouabdellah Y. A rare tumor of the lung: inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:83. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surabhi V.R., Chua S., Patel R.P., Takahashi N., Lalwani N., Prasad S.R. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors: current update. Radiol Clin North Am. 2016;54(3):553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narla L.D., Newman B., Spottswood S.S., Narla S., Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics. 2003;23(3):719–729. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patnana M., Sevrukov A.B., Elsayes K.M., Viswanathan C., Lubner M., Menias C.O. Inflammatory pseudotumor: the great mimicker. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(3):W217–W227. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrons G.A., Rosado-de-Christenson M.L., Kirejczyk W.M., Conran R.M., Stocker J.T. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor: radiologic features. Radiology. 1998;206(2):511–518. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.2.9457206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morar R., Bhayat A., Hammond G., Bruinette H., Feldman C. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the lung: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Radiol. 2012;2012:214528. doi: 10.1155/2012/214528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedlund G.L., Navoy J.F., Galliani C.A., Johnson W.H., Jr. Aggressive manifestations of inflammatory pulmonary pseudotumor in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29(2):112–116. doi: 10.1007/s002470050553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]