Abstract

AMPA and kainate receptors, along with NMDA receptors, represent different subtypes of glutamate ion channels. AMPA and kainate receptors share a high degree of sequence and structural similarities, and excessive activity of these receptors has been implicated in neurological diseases such as epilepsy. Therefore, blocking detrimental activity of both receptor types could be therapeutically beneficial. Here, we report the use of an in vitro evolution approach involving systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment with a single AMPA receptor target (i.e. GluA1/2R) to isolate RNA aptamers that can potentially inhibit both AMPA and kainate receptors. A full-length or 101-nucleotide (nt) aptamer selectively inhibited GluA1/2R with a KI of ∼5 μm, along with GluA1 and GluA2 AMPA receptor subunits. Of note, its shorter version (55 nt) inhibited both AMPA and kainate receptors. In particular, this shorter aptamer blocked equally potently the activity of both the GluK1 and GluK2 kainate receptors. Using homologous binding and whole-cell recording assays, we found that an RNA aptamer most likely binds to the receptor's regulatory site and inhibits it noncompetitively. Our results suggest the potential of using a single receptor target to develop RNA aptamers with dual activity for effectively blocking both AMPA and kainate receptors.

Keywords: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPA receptor, AMPAR); central nervous system (CNS); glutamate receptor; inhibitor; RNA; kainate receptor; RNA aptamers; SELEX

Introduction

Ionotropic glutamate receptors mediate the majority of excitatory neurotransmission in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) and are indispensable for brain development and function (1, 2). The ionotropic glutamate receptor family includes three receptor subtypes that can all be activated upon binding of glutamate: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA), kainate, and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (1–3). Compared with NMDA receptors, AMPA and kainate receptors are more alike in both sequence and structure (3, 4). AMPA receptors are expressed post-synaptically and are involved in fast excitatory neurotransmission (1). Kainate receptors are expressed both pre- and post-synaptically, and contribute to excitatory neurotransmission and modulate network excitability by regulating neurotransmitter release (5, 6).

AMPA and kainate receptors are widely expressed in the brain. AMPA receptors have four subunits, i.e. GluA1–4. GluA1–3 are enriched in the hippocampus, outer layers of the cortex, olfactory regions, lateral septum, basal ganglia, and amygdala, etc. (7, 8). The expression of the GluA4 subunit is low to moderate throughout the CNS, except in the reticular thalamic nuclei and the cerebellum where its level is high (9–11). Kainate receptors have five subunits, i.e. GluK1–5. At the mRNA level, GluK1 is highly abundant in the neocortex, hypothalamus, and the hindbrain, whereas GluK2 is highly abundant in the cerebellum. GluK3 is widely distributed in the brain. GluK4 is enriched in the hippocampus (CA3 pyramidal cells). GluK5 is abundant in the neocortex, hippocampus (dentate gyrus and CA2, 3 pyramidal cells), and cerebellum (granule cells) (12, 13). At the protein level, GluK2 is one of the major kainate receptor subunits in the hippocampus and cerebellum (14). AMPA and kainate receptors may also jointly participate in some neurological activities. For example, kainate receptors mediate excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs)2 of small amplitude and slow decay at mossy fiber synapses, whereas AMPA receptors mediate fast and large EPSC (15). The post-synaptic kainate receptors at these synapses can be also selectively blocked, leaving synaptic AMPA receptors unaffected (16, 17).

There should be a utility of developing antagonists that can effectively block both AMPA and kainate receptors. This is because AMPA and kainate receptors are both involved in some neurological diseases; epilepsy is an example. A study of GluK2-deficient mice has revealed that hippocampal neurons in the CA3 region express both AMPA and kainate receptors, and both receptor types are involved in seizures (18). Entorhinal cortex, a highly epilepsy-prone brain region, also expresses GluA1–4 and GluK5 (19). In both human patients and animal models of temporal lobe epilepsy, the axons of granule cells that normally contact CA3 pyramidal cells sprout to form aberrant glutamatergic excitatory synapses onto dentate granule cells (20–22). The formation of aberrant mossy fiber synapses onto dentate granule cells has been suggested to induce the recruitment of kainate receptors in chronic epileptic rats. These granule cells express AMPA receptors as well, especially GluA1 and GluA2 subunits (23). Other examples that involve both receptor types include acute and chronic pain activated through interior cingulate cortex (15, 24). Together, these lines of evidence suggest that antagonists capable of blocking the activity of both AMPA and kainate receptors should be useful. In fact, a nonselective AMPA/kainate receptor inhibitor, tezampanel (NGX424; Torrey Pines Pharmaceutics), reduced both migraine pain and other symptoms in a Phase II trial. NS1209 (NeuroSearch A/S), another non-selective AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist, was also shown in Phase II studies to alleviate refractory status epilepticus and neuropathic pain (25).

Currently, compounds that do act on both receptor types are by and large competitive inhibitors, and are small molecules. For example, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,5-dione (CNQX) and 2,3-dihydro-6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo-f-quinoxaline (NBQX) are such inhibitors but both are more potent and selective toward AMPA receptors (KI = 0.27 and 0.06 μm, respectively) than toward kainate receptors (KI = 1.8 and 4.1 μm, respectively) (26–28). CNQX shows only a limited selectivity for AMPA versus kainate receptors (affinity ratio ∼7), whereas NBQX is considered more of an AMPA receptor antagonist (affinity ratio ∼70). However, orthosteric inhibitors or drugs tend to exhibit more significant side effects due to their binding to homologous receptors sharing a similar binding site (29). In contrast, the antagonistic action of noncompetitive inhibitors is more preferable. However, noncompetitive inhibitors with equal or nearly equal dual activities on both AMPA and kainate receptors have not been reported (28, 30). In fact, the number of noncompetitive inhibitors developed to date toward kainate receptors is considerably limited (28).

Here we report an RNA aptamer capable of blocking AMPA and kainate receptors without affecting NMDA receptors, and this dual functionality depends on the length of the RNA. On the kainate receptor side, the aptamer or precisely the shorter length aptamer inhibits GluK1 and GluK2 equally well. Yet the full-length, original aptamer selectively inhibits GluA1/2 complex channels, along with the GluA1 and -2 subunits. This aptamer has been identified from a large RNA library (∼1014 sequence variations) using an in vitro evolution approach known as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) (31–34). Because the aptamer is an RNA molecule, it is water soluble by nature. Therefore, this aptamer represents a new class of inhibitors as an alternative to existing small-molecule antagonists for AMPA and kainate receptors.

Results

Design principle

To find an aptamer that may possibly act on both AMPA and kainate receptors, we attempted to choose a single receptor as the target of selection using SELEX. This was possible given that AMPA and kainate receptors share a high degree of sequence and structural homologies (2). Furthermore, given its size, an RNA from our library may bind to the surface of a receptor topologically. As a result, the larger area of interaction with the receptor, as compared with the interaction of a small molecule, may generate sufficient multivalent binding interaction so that an RNA could bind to and inhibit both AMPA and kainate receptors. In contrast, using multiple targets may likely enable the identification of individual aptamers with singular activity. We further decided to choose an AMPA receptor (i.e. GluA1/2R; see detail below), rather than a kainate receptor, as that single receptor target. This was because there are more noncompetitive inhibitors of AMPA receptors (30) than those of kainate receptors (28). Developing antagonists against kainate receptors in general has been far more challenging (28).

Among all possible AMPA receptor types, we decided to choose GluA1/2R as the target of selection. GluA1/2R is an important channel type (12, 35–37). For example, in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells, ∼80% of synaptic and >95% of somatic extrasynaptic receptors express GluA1/2R heteromers (37). In addition, isolating a target-specific aptamer by SELEX can be significantly facilitated by the use of a binder as the displacement, such as an inhibitor, so that the RNA molecules that bind to the same or a mutually exclusive site can be eluted or selected. However, to find an aptamer capable of recognizing and acting on both AMPA and kainate receptors, we avoided using any known binder. Instead, we used urea after the binding step to denature both the target and possibly all bound RNA molecules, thereby allowing us to select and screen the maximal number of RNA molecules bound to all possible sites on the target. It should be further noted that the choice of using GluA1/2R channel type seemed more appropriate, because to date there is no known selective antagonist targeting the GluA1/2R channel. Therefore, these design features were intended to provide us with the maximum possibilities of finding an RNA aptamer with dual activity on both AMPA and kainate receptors.

Aptamer selection using SELEX

To select RNA aptamers, we used SELEX (31, 32), which involves multiple cycles or rounds. Each round consists of RNA-receptor binding, RNA elution, RT-PCR amplification, followed by enzymatic transcription from the DNA library to regenerate a new RNA library or pool (31, 32). For the target preparation for binding with potential RNA aptamers, GluA1/2R receptors were transiently expressed in HEK-293S cells. To ensure the channel was functional, we used membrane fragments containing the holo-GluA1/2R receptors (38). At the elution step of each round, bound RNAs were dissociated from the receptor using a urea solution. A total of 10 rounds of selection were completed for the SELEX experiment. To minimize the evolution of nonspecific RNAs, we ran a negative selection after rounds 5, 7, and 9. A negative selection consisted of HEK-293S cell membrane fragments lacking only the GluA1/2R receptor, which was used to “filter” or absorb RNAs bound to any other target, but GluA1/2R, from that RNA library. The RNA library that was treated by a negative selection was then used for positive selection, which was involved in exposure of the RNA library to the GluA1/2R receptor. Therefore, running a negative selection was to suppress the evolution of any nonspecific RNAs or enhance the evolution of RNAs that specifically recognize the GluA1/2R target during the SELEX operation.

Identification of functional RNAs

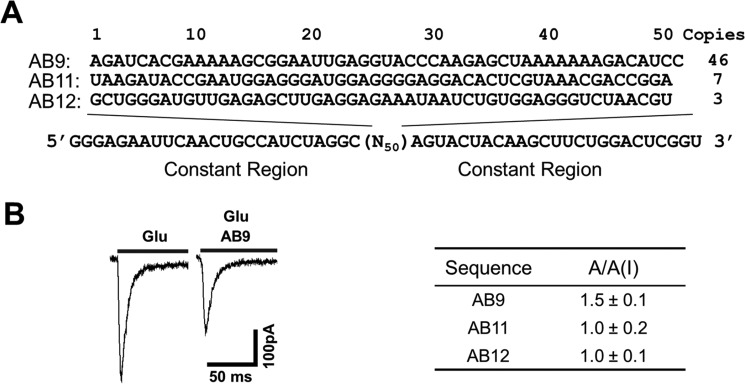

After 10 SELEX rounds, we cloned the 9th and 10th DNA libraries. From a total of 89 clones (i.e. 38 clones from round 9, and 51 from round 10), we identified three consensus sequences (Fig. 1A). Specifically, we considered a sequence to be consensus if that sequence appeared at least three times of a pool of 89 clones. The most populous or enriched sequence was named AB9 (Fig. 1A). This RNA represented 16% of the pool at round 9, but had grown to 80% of the pool by round 10. The second enriched sequence was named AB11 (Fig. 1A); AB11 was identified by a single sequence in round 9, but had grown to 11% by round 10. The third sequence, AB12, represented 4% of the pool at round 10. All others were single sequences. These three enriched sequences were our candidates for functional assays.

Figure 1.

Enriched RNA sequences and their biological functions. A, the three enriched sequences identified from the SELEX against GluA1/2R are shown with their names at the left and the copy numbers at the right. A copy number represents the number of appearances of the same sequence in the pool of 89 sequences in total. The variable sequence region (N50) is shown on top of the 5′ and 3′ constant regions. B, shown on the left is a pair of representative whole-cell current responses of GluA1/2R to 0.05 mm glutamate in the presence of 2 μm AB9 aptamer. The table on the right summarizes the ratio of the whole-cell current amplitude in the absence and presence, A/A(I), of 2 μm aptamer at 0.05 mm glutamate.

Based on these corresponding DNA sequences, we prepared the three RNAs by enzymatic transcription. The full-length RNAs were purified using a cylindrical PAGE (“Experimental procedures”) for functional testing. Specifically, each of the RNAs was measured for its putative ability of inhibiting the glutamate-induced whole-cell current amplitude through the GluA1/2R channel, because GluA1/2R was used as the SELEX target. Based on the ratio of the whole-cell current amplitude in the absence and presence of an aptamer, A/A(I), we found that the most enriched sequence, AB9, was indeed an inhibitor for GluA1/2R (see a pair of representative traces in Fig. 1B). None of the other two RNAs (the two lower sequences in Fig. 1A), however, exhibited any inhibition of GluA1/2R (i.e. the average of A/A(I) ≈ 1, in the inset of Fig. 1B). In this assay, we used 50 μm and 3 mm glutamate concentrations to assay an aptamer with the closed-channel and open-channel forms, respectively (see under “Experimental procedures”). At 50 μm glutamate concentration, most of the AMPA receptor population was in the closed-channel form (i.e. ∼96% were in the closed-channel form). In contrast, at 3 mm glutamate concentration, the majority of the AMPA receptor channels were in the open-channel form (38). We also observed AB9 only inhibited the closed-channel, but not the open-channel, form at the same aptamer concentration.

Identification of the minimal, functional aptamer sequence

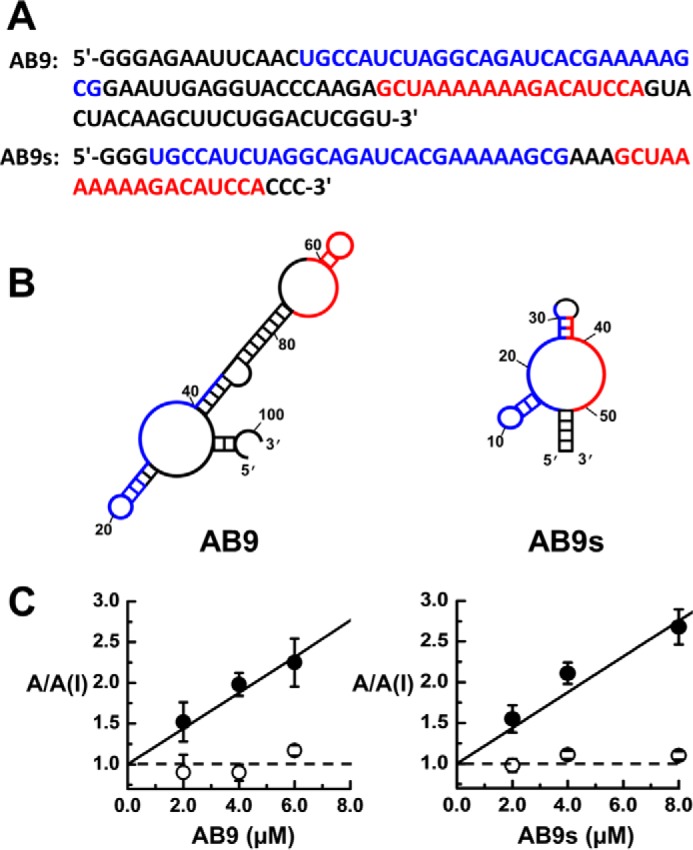

Next we truncated the full-length aptamer AB9 to identify the minimal, but functional, sequence. This experiment is customary to reveal secondary structural motifs of an RNA essential for its biological function. Guided by the Mfold program, we designed a series of shorter RNAs based on the sequence of AB9 (Fig. 2), and tested them by whole-cell recording assay to establish whether a truncation caused any loss of function against the GluA1/2R receptor. We found the two sequence segments, colored by blue and red in Fig. 2, were essential for the inhibitory property of the aptamer. The shortest aptamer was a 55-nt RNA, named as AB9s, which carried these two sequence segments (Fig. 2B, right panel). Functionally, AB9s showed a KI of 4.7 ± 0.2 μm (Fig. 2C, right panel), determined from the A/A(I) plot using Equation 2 (“Experimental procedures”), as compared with KI of 4.5 ± 0.3 μm for full-length AB9 (Fig. 2C, left panel). Therefore, AB9s was a fully functional aptamer, albeit shorter. Interestingly, both aptamers inhibited the GluA1/2 receptor by inhibiting only the closed-channel form, but not the open-channel conformation (Fig. 2C, solid symbol/solid line versus open symbol/dotted line).

Figure 2.

Sequences, secondary structures, and function of aptamer AB9 and AB9s. A, the RNA sequences of the full-length AB9 aptamer, and the shorter sequence AB9s. The blue and red sequences are the two essential sequence segments for biological activity. AB9s is the minimal, functional aptamer derived from the full-length aptamer AB9. B, shown on the left and right are the most stable secondary structure of aptamer AB9 (ΔG = −15.92 kcal/mol) and AB9s (ΔG = −10.09 kcal/mol), respectively, based on the MFold prediction. C, the A/A(I) plot versus aptamer concentration for AB9 (left) and AB9s (right). The current amplitude was obtained from whole-cell recording with GluA1/2R expressed in HEK-293 cells. The inhibition constant, KI, for the closed-channel form of GluA1/2R was determined from the plot, using Equation 2 (”Experimental procedures“), to be 4.5 ± 0.3 and 4.7 ± 0.2 μm for AB9 and AB9s, respectively. Neither aptamer inhibited the open-channel form, as shown in the dotted line (or A/A(I) = 1).

In the truncation experiment, we also observed that (i) a truncated RNA that contained either the blue or red sequences alone was nonfunctional (Fig. 2B); and (ii) removing the long, central sequence section, which is largely based-paired in the full-length RNA (i.e. the sequence in black in the left panel of Fig. 2B) but with the two, colored sequence segments intact, did not affect the inhibitory properties. The truncated RNA was, however, still 78-nt long, and thus was not a minimal RNA, as compared with the 55-nt AB9s (Fig. 2B, right panel).

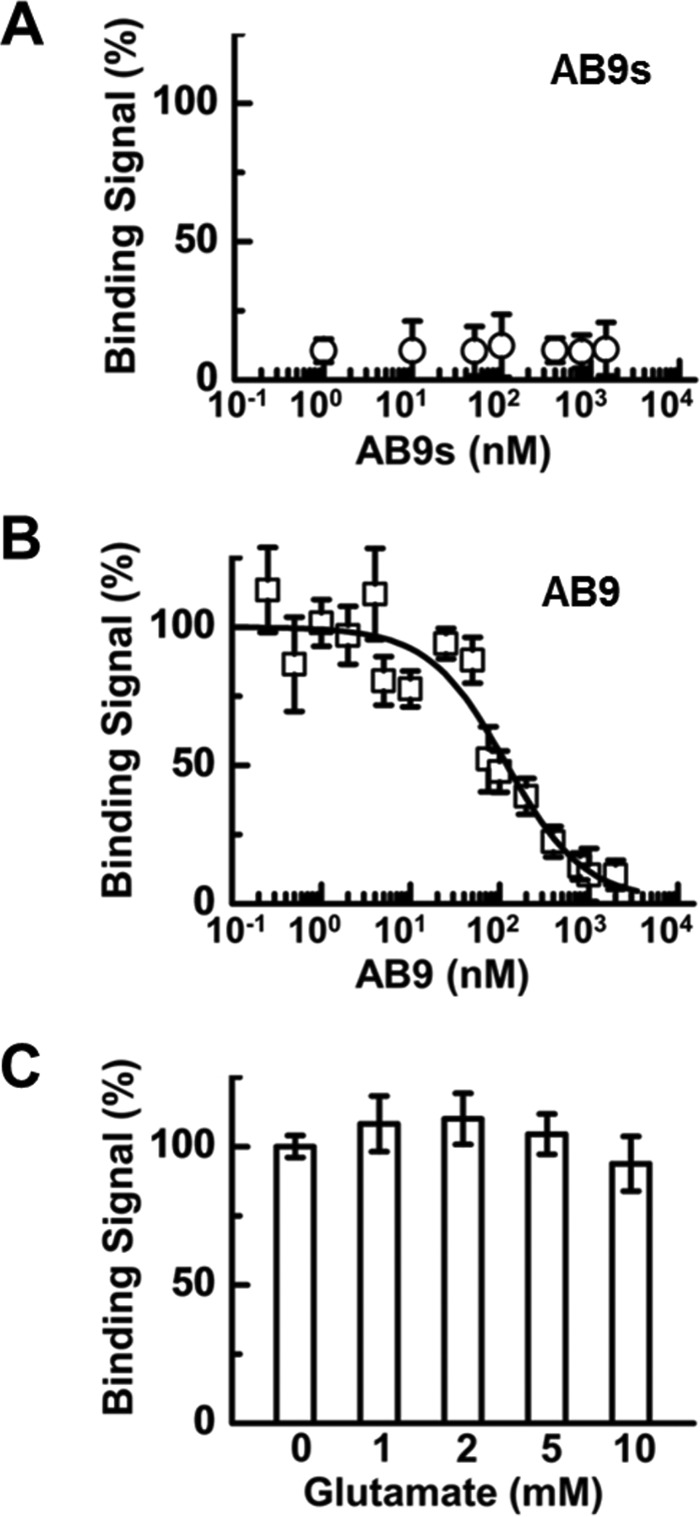

Homologous competition binding with AB9s and AB9 for determining binding affinity

We next attempted to determine the binding affinity of AB9s, the shorter aptamer. To do this, we prepared 32P-labeled AB9s and ran a homologous binding assay (39) with the GluA1/2R lipid membrane. Because AB9s exhibited full inhibitory activity against GluA1/2R (Fig. 2C), we anticipated it would bind to the receptor, yielding a specific binding signal or net radioactivity due to bound AB9s to the receptor. Surprisingly, however, we were unable to observe any specific radioactivity (Fig. 3A). We suspected the failure of observing any radioactivity due to binding of 32P-labeled AB9s to GluA1/2R could be attributed to a fast off-rate of the binder during the washing phase (“Experimental procedures”). Washing after binding was necessary to minimize nonspecific binding of the 32P-labeled aptamer. In our experiment, after washing twice with ice-cold buffer, the amount of the bound 32P-labeled aptamer dropped too low to be detected, presumably due to a fast dissociation rate. We then hypothesized the full-length aptamer might have a slower off-rate, yielding a detectable specific radioactivity. Because AB9 is almost twice as long as AB9s, the full size AB9 aptamer would have a stronger multivalent interaction overall with its site in the same receptor as compared with the shorter counterpart, assuming both bind to the same site. A larger RNA should also have a larger topological surface, therefore covering a larger area of the binding site. As such, the full-length aptamer could bind tighter, and prolong its dissociation from the receptor site.

Figure 3.

Homologous binding assay for AB9s (A), AB9 (B), and AB9 in the presence of glutamate (C). In all of these assays, 32P-labeled aptamer was used with the GluA1/2R lipid membrane (see ”Experimental procedures“). Triplicate experiments were run for each aptamer. In B, the full size aptamer AB9 showed binding signal or radioactivity, whereas the shorter AB9s aptamer showed essentially no signal, in A. For aptamer AB9, the original radioactivity was normalized to 100%. The original radioactivity was averaged using the first three data points in B. The binding constant, Kd, for the binding of AB9 to the unliganded GluA1/2R was determined to be 98 ± 40 nm, using Equation 1 (”Experimental procedures“). In C, glutamate at various concentrations did not displace bound AB9.

Using the same homologous binding assay, we carried out the binding experiment with 32P-labeled AB9 and GluA1/2R lipid membrane. Indeed, the full-length AB9 exhibited a dose-dependent radioactivity due to the binding of AB9 (Fig. 3B). As a control, we did not observe any appreciable (or beyond background) radioactivity when we exposed 32P-labeled AB9 to HEK-293 cell membrane that contained no GluA1/2R. We then determined the binding affinity or Kd of the full-length AB9 to be 98 ± 40 nm (Fig. 3B). This affinity is comparable with a variety of RNA aptamers we have previously selected to inhibit homomeric AMPA receptors, including those subunit-selective and open-channel formation-selective aptamers (38, 40, 41). The fact that the full-length aptamer exhibited detectable radioactivity in the homologous binding experiment, but the shorter aptamer did not, was consistent with our hypothesis. It should be further noted that the bound, 32P-labeled AB9 could not be displaced by glutamate even when glutamate was used at saturating concentrations (Fig. 3C). This result suggested that the receptor site to which the aptamer was bound was not the agonist-binding site.

Subunit selectivity of AB9s and AB9

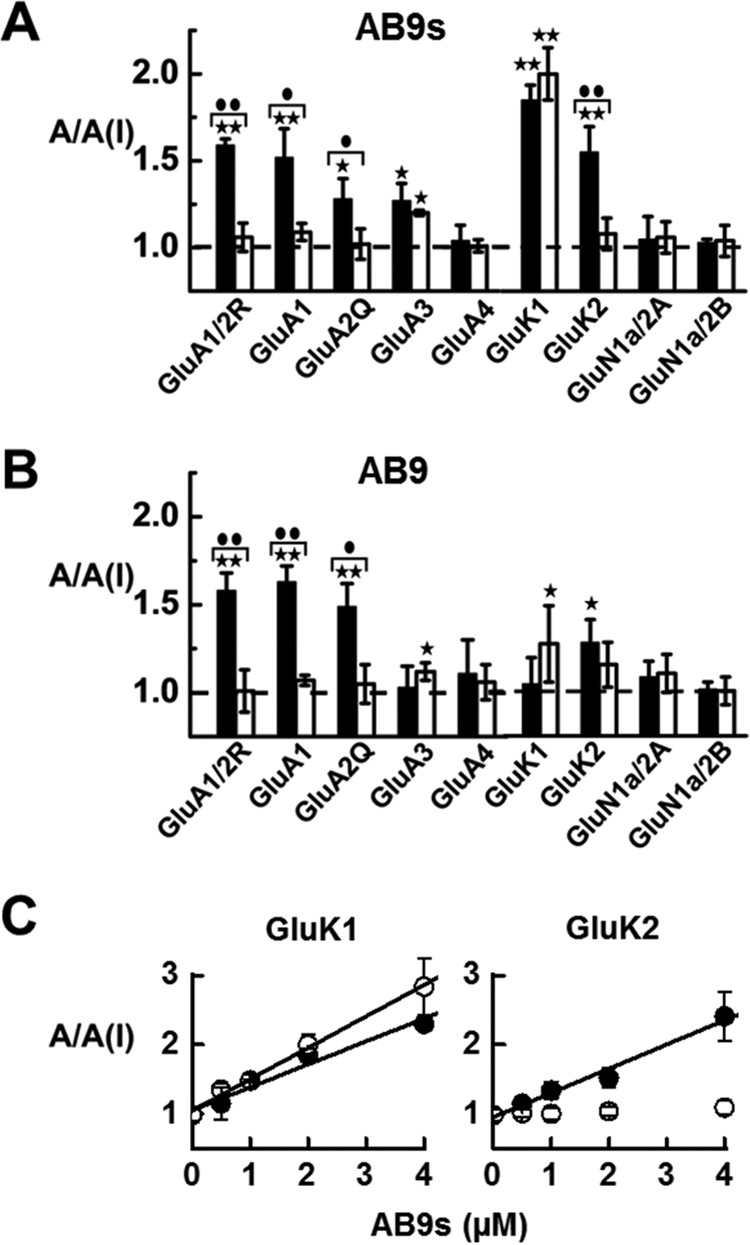

Because the full-length and the truncated aptamers were found to inhibit the heteromeric GluA1/2R channel, the SELEX target, we then expanded the functional assay to other receptor subunits and/or channel types. Using whole-cell recording, we similarly measured the A/A(I) value against a panel of glutamate receptors (Fig. 4). Specifically, the shorter aptamer (AB9s) also inhibited GluA1 and -2Q, and to some extent GluA3 homomeric AMPA receptors; more prominently, however, AB9s also inhibited GluK1 and GluK2 kainate receptors (Fig. 4A). This aptamer did not inhibit NMDA receptors (i.e. GluN1/2A and GluN1/2B) (Fig. 4A). These results demonstrated that aptamer AB9s is a desired inhibitor of AMPA and kainate receptors. It should be noted that GluK1 and GluK2 can form homomeric kainate channels, whereas the two NMDA receptor complexes are two dominate receptor types found in vivo (3), and none of the NMDA receptor subunits can form functional channels on its own (42). Interestingly, the full-length aptamer AB9 has shown a different selectivity profile (Fig. 4B) as compared with the short aptamer (Fig. 4A). The full-length aptamer exhibited a slightly less overall potency toward AMPA receptors; the largest reduction of the inhibitory potency from the full-length AB9 aptamer was toward GluK1 and GluK2 kainate receptors (Fig. 4B), when compared with the shorter AB9s aptamer. Specifically, to validate the t test result, which showed an apparent weak inhibition of AB9 on the GluK1 open state or the GluK2 closed state (as compared with the theoretical A/A(I) mean value of zero inhibition, i.e. 1.0, in Fig. 4B), we used the same assay with AB9 but at a higher aptamer concentration, and observed a higher A/A(I) value or a clearer reduction of current amplitude (supplemental Fig. S1). This experiment also validated that the full-length AB9 was selective to GluA1 and GluA2 or the GluA1/2R AMPA channel.

Figure 4.

Glutamate receptor subunit selectivity of AB9s (A) and AB9 (B), and the A/A(I) plot versus concentration of AB9s against kainate receptors (C). In each aptamer version, whole-cell current recording was used, and the A/A(I) ratio was collected in the presence of 2 μm aptamer. For each of the receptor types, the glutamate concentration was chosen to be equivalent to ∼4 and ∼95% fractions of the open channels. Specifically, the glutamate concentration was 0.05 mm for the closed-channel form and 3 mm for the open-channel form for GluA1/2R and GluA1, 0.5 and 10 mm for GluA3, 0.1 and 3 mm for GluA4. The kainate receptors were tested at 0.05 mm glutamate for the closed-channel and 3 mm for the open-channel forms. The NMDA receptors were tested at 0.02 mm glutamate for closed-channel and 0.05 mm for open-channel forms. Significance of inhibition as evaluated by a one-sample two-tailed Student's t test is represented by either a single asterisk where p ≤ 0.05, or two asterisks indicating p ≤ 0.01. The difference between open- and closed-channel conformations was determined with a two-sample, two-tailed Student's t test. A single circle indicates p ≤ 0.05, whereas the two circles indicate p ≤ 0.01. Error bars indicate mean ± S.D. In C, the A/A(I) values are plotted again at various concentrations of AB9s aptamer for GluK1 (left panel) and GluK2 (right panel). For GluK1, the KI value was determined from the plot, using Equation 2, to be 2.2 ± 0.2 and 3.0 ± 0.1 μm for the open-channel and closed-channel forms, respectively. For GluK2, the KI value was determined to be 2.9 ± 0.2 μm but only for the closed-channel form; AB9s showed no inhibition toward the open-channel form.

Because the shorter aptamer or AB9s was a strong inhibitor of both GluK1 and GluK2 homomeric channels, we further collected the A/A(I) value in a series of aptamer concentrations for a better characterization of its inhibition. We found (Fig. 4C) that AB9s inhibited both the open- and closed-channel forms of the GluK1 homomeric channel, whereas AB9s only inhibited the closed-channel, but not the open-channel form of the GluK2 channel. The corresponding KI value was determined (Fig. 4C). The comparison of the KI value (i.e. the closed-channel form only) but with the two different kainate receptor subunits showed AB9s exhibited a similar potency for GluK1 and GluK2, because the KI for the closed-channel form of GluK1 and GluK2 was 3.0 ± 0.1 and 2.9 ± 0.2 μm, respectively (Fig. 4C). In addition, AB9s also inhibited the open-channel form of GluK1 with a KI of 2.2 ± 0.2 μm.

Discussion

In this report we describe two novel RNA aptamers. The full-length, original RNA aptamer seems to selectively inhibit the GluA1/2R heteromeric channel. It is probably not surprising that AB9 also inhibits GluA1 and GluA2 individually. However, the shorter version of this aptamer or AB9s has “inherited” the inhibitory activity of the longer aptamer but most prominently AB9s is now a strong inhibitor of GluK1 and GluK2, the two key kainate receptor subunits, with equal potency (Fig. 4). As expected, neither aptamer has any effect on NMDA receptors (Fig. 4). To our knowledge, such a selectivity profile for an antagonist (i.e. AB9s) with dual inhibitory properties has not been previously reported. In fact, the shorter aptamer with a 55-nt length, which bears two key sequence segments found in the full-length aptamer AB9 (Fig. 1B), seems just as potent, if not even more potent, on the two kainate receptor subunits, as compared with the AMPA receptors (Fig. 4, A and B).

When the secondary structures of these two RNA constructs are compared (Fig. 2B), the shorter aptamer harbors the minimal, functional sequences, marked by blue and red. Yet the full size RNA aptamer contains a stretch of based-paired sequence in the middle (Fig. 2B). Although the centrally located, based-paired sequence segment is not essential for the biological activity of the aptamer for GluA1/2R, the SELEX target (Fig. 2C), the full size aptamer with the central sequence segment seems to enable the aptamer to bind more selectively and thus inhibit more selectively the AMPA receptors. Consistent with this notion is that the full size aptamer most likely enables the AB9 to bind tighter to the receptor, thereby slowing the rate of dissociation of the aptamer from the site, as compared with the shorter RNA. On the other hand, truncating the central base-paired sequence segment of the full-length aptamer, which results in the 55-nt shorter version, has unleashed the power of the aptamer to potently block kainate receptors. The origin of this enhancement due to a smaller size, as compared with the full size aptamer, is unclear at the present.

Virtually all known kainate receptor antagonists have a stronger affinity and potency toward GluK1 than any other kainate receptor subunits (28). Almost all that inhibit GluK2 actually have stronger potency toward GluK1 (28). In this context, it is unique that AB9s is nearly equally effective in inhibiting both the GluK1 and GluK2 kainate receptors; AB9s further possesses a nearly identical potency for both the AMPA and kainite receptors (Fig. 4A). Among the existing inhibitors of either AMPA or kainate receptors, NBQX does inhibit roughly equally well both GluK1 and GluK2; but NBQX is considered an AMPA receptor inhibitor, because it inhibits AMPA receptors >8-fold stronger (28). Glutamylaminomethyl sulfonic acid marginally distinguishes kainate from AMPA receptors, based on various in vivo and in vitro tests, including a test in a seizure model (43–46). However, glutamylaminomethyl sulfonic acid shows a significant antagonism of NMDA receptors (47). In contrast, AB9s can block the activity of both AMPA and kainate receptors equally well without appreciable NMDA receptor activity. In addition, because the aptamer is an RNA molecule, it is a water-soluble antagonist, different from almost all of the existing antagonists for either AMPA or kainate receptors.

The experimental design by which we used a single SELEX target (i.e. GluA1/2R) in a single SELEX operation to evolve a single RNA aptamer that acts on both the AMPA and kainate receptors turns out to be an effective way of generating RNA inhibitors with a desirable inhibitory versatility. The success of this approach relies on the high degree of sequence and structural similarities not only between the kainate and AMPA receptor subtypes but also within a single receptor subtype. More precisely, no place shows a higher structural similarity than the site to which AB9 binds, although at the moment, we do not know the location of this site. We do know, however, this site is unlikely the agonist-binding site. Several lines of evidence suggest that this site may be noncompetitive. (i) That glutamate cannot displace the radiolabeled aptamer supports that the aptamer does not bind to the agonist site as a competitive inhibitor. (ii) The shorter aptamer in particular inhibits both the open-channel and the closed-channel forms of both GluK1 kainate receptor and GluA3 AMPA receptor. The inhibition of both forms is a strong indication of a noncompetitive inhibitor (48). An uncompetitive inhibitor or more commonly termed “open-channel” blocker would only inhibit the open-channel but not the closed-channel form (48). In contrast, a noncompetitive inhibitor binds to a regulatory site through which its inhibition can be realized independently of ligand concentration (48). It should be also noted that AB9s inhibits only the closed-channel form of GluK2, but the same aptamer inhibits both the closed- and open-channel forms of GluK1. It is therefore likely that the same aptamer may act on GluK1 differently from GluK2. Their sites on the two receptors may not be the same.

As a proof of concept, we have shown that using a specially designed SELEX experiment has enabled us to isolate a new type of antagonist or RNA aptamer with a potential of exerting a length-dependent, dual inhibitory activity on AMPA and kainate receptors. Such a strategy may be applicable to identify other types of RNA aptamers that perhaps bind to a site, even a new site, covering a larger “footprint” on the receptor than traditionally a small molecule inhibitor. A large interactive interface may provide enough similarity and difference as well to allow the binding of a large macromolecule like RNA to use perhaps different modules to inhibit similar receptor targets, even though only a single receptor target is used to discover such an RNA though molecular recognition and interaction. As shown in Fig. 4B, because the full-length aptamer or AB9 was in the original RNA library, it may not be surprising that AB9 is still preferentially selective in inhibiting the target or the GluA1/2R heteromeric channel, and the similar subunits, i.e. GluA1 and GluA2Q, although AB9 has weak activity on other subunits such as GluA3 and the two kainate receptors (supplemental Fig. S1). However, removing the central sequence segment has turned this aptamer into a much better inhibitor of the GluK1 and GluK2, the two key kainate receptor subunits.

Obviously, the limitation of our aptamer, such as AB9s, in its potential application in vivo is that its dual inhibitory activity cannot be decoupled. However, one possibility to overcome that limitation is to systematically mutate the sequence of the nucleotides in AB9s, due to its shorter sequence and better inhibitory properties than the full size aptamer, and hopefully identify key residues so that its dual activity can be decoupled. If that happens, we would have an additional ability to mix and match two or more aptamers with more different concentrations to achieve a greater control of the AMPA and kainate receptor functions in vivo. Finally, it should be noted that RNA aptamers can be delivered to the CNS by bypassing the blood-brain barrier using a variety of drug delivery approaches, including intracerebroventricular (ICV) and intrathecal (IT) injection. These approaches have been used for delivering proteins (49), peptides (50), and RNAs (51) as drugs or drug candidates. However, therapeutic RNA aptamers are generally chemically modified to contain 2′-fluoro or 2′-O-methyl groups, for instance, making them resistant to degradation by endogenous nucleases, and therefore improving their pharmacokinetic properties (52).

Experimental procedures

Transient receptor expression and cell culture

The cDNAs encoding the rat GluA1–4 AMPA receptors, two representative NMDA receptors (i.e. GluN1a/2A and GluN1a/2B) and kainate (GluK1 and GluK2) receptors, were prepared as previously described (38, 40, 41). Each of these receptors was transiently expressed in HEK-293S. The cell line was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence of 1% penicillin in a 37 °C, 5% CO2, humidified incubator. The HEK-293S cells were co-transfected with large T-antigen; those used for recording were also co-transfected with the plasmid encoding green fluorescent protein (40). After 48 h the transfected cells were used either for electrophysiology or harvested for SELEX. The membrane fragment containing holo-receptors was prepared as described (40).

For SELEX, the GluA1/2R complex channel was used. GluA2R is the edited isoform of GluA2 at the Gln/Arg editing site (53). At this site, a glutamine (Gln-607) is replaced by an arginine (Arg) (53–55). Unlike the edited Q isoform or GluA2Q, GluA2R is largely unassembled and endoplasmic reticulum-retained (56). When expressed alone in HEK-293 cells, GluA2R channels exhibit a very low conductance of ∼300 femtoseimens (57). However, GluA2R is readily assembled with other AMPA receptor subunits, such as GluA1, forming functional channels. Experimentally, we used a ratio of 4:1 or 4 parts of the GluA2R plasmid (by weight) to one part of GluA1 plasmid for transfection to ensure the formation of GluA1/2R (58, 59). To confirm the formation of the GluA1/2R channel, we used whole-cell recording and measured the current-voltage (I-V) relationship. Specifically, GluA1 homomeric channels (and any other AMPA receptors lacking GluA2R) exhibited an inwardly rectifying I-V relationship, whereas an I-V relationship for GluA1/2R, was linear (58, 60–62).

For selectivity assays, we expressed all GluA1, -2Q, -3, and -4 AMPA receptors, along with GluA1/2R, in HEK-293 cells for whole-cell recording. For kainate receptors, we only used GluK1 and GluK2 as representative kainate receptors for the assay, and each can form homomeric functional channels. We did not use GluK3 for the assay, because GluK3 has an EC50 value of >4 mm (63), and glutamate concentration at synapses is thought to be <1 mm (64).

Receptor preparation for binding study

The GluA1/2R receptor used in the binding study was prepared from the HEK-293 cell membrane, as previously described (38, 40). Briefly, the cells were rinsed with cold phosphate-buffered solution (PBS), then collected in cold PBS containing 0.5 mm EDTA, and 1 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). The cells were spun down and homogenized using a pestle (Potter-Elvehjem) in cold 50 mm Tris acetate buffer containing 10 mm EDTA and 1 mm PMSF. The fragmented cell membrane was then pelleted down by centrifugation at >17,000 × g for 25 min, and then re-suspended in external buffer (see next section), with a final concentration of 5 mg/ml.

The concentration of the receptor embedded in the cell membrane fragments was determined using [3H]AMPA (38, 40). [3H]AMPA was allowed to bind at different concentrations until saturation was reached, thus giving a maximum counts per min (cpm) per unit membrane (in mg). Using a standard curve of radioactivity versus concentration of [3H]AMPA, we established the concentration of the AMPA receptor/mg of membrane fragments. It should be noted that the concentration readout from the working curve was equal to the concentration of a single AMPA receptor subunit. The concentration of the channel was four times smaller, assuming each channel was composed of four subunits.

In vitro selection

The preparation of the RNA library and the protocol for running SELEX with the GluA1/2R receptor are previously described (40). In the first round, the RNA library containing ∼1014 random sequences was dissolved in extracellular buffer (2.5 μm, final concentration). The extracellular buffer contained 3 mm KCl, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4). In the initial binding mixture, the final concentration of the membrane-bound receptor in the HEK-293 membrane fragments (40) was 7 nm. The RNA library/receptor mixture was first incubated for ∼1 h between 23 and 37 °C; an 8 m urea solution was used to denature and elute bound RNAs. The eluted RNAs were subject to RT-PCR. For sequencing, pGEM-T easy vector (Invitrogen) was used to clone a DNA library. Sequence comparison from the selected clones allowed us to identify enriched sequences for functional assay (see text for detailed explanation).

Homologous binding assay

A 32P-labeled aptamer was prepared (40). The final concentrations of the receptor and labeled/cold aptamer were 1 and 20 nm, respectively. The working stock of the hot/cold aptamer had ∼2,500 cpm (the background had ∼80 cpm). The binding mixture (300 μl) was incubated at 4 °C for 4 h. The mixture was then split to 100 μl each, and loaded onto a presoaked nylon filter (VWR, catalog number 82031-362, 0.45-μm pore size; this filter as we found retained insignificant level of RNA). The membrane bound with the hot aptamer was washed with ice-cold extracellular buffer twice. One wash (from buffer loading to the end of the spin filtration at 1,500 g force and 4 °C) took ∼5 min to complete. The radioactivity on the filter was determined by scintillation counting (Beckman LS6500). The binding signal (Y) was plotted against the concentration of the RNA aptamer. Assuming a one-site binding model, we determined the Kd of the aptamer bound to the receptor by fitting the binding data to Equation 1 (39), where [hot] and [cold] are the concentrations of the unbound hot aptamer and cold aptamer; NSB represents any nonspecific binding, and Bmax is the maximal number of receptor binding sites (65). Glutamate solution was also used in separate experiments to assess whether the aptamer was bound to the agonist site.

| (Eq. 1) |

RNA purification

We prepared RNA by enzymatic transcription and purified the desired RNA for functional assay. For purification, we used a Bio-Rad PrepCell, a continuous elution PAGE apparatus (66). Specifically, a 12% urea PAGE gel was cast in 1× TBE (Tris borate-EDTA) buffer. The gel was run at 150 V for 20 h, at a 1-ml/min flow rate. The RNA elution was monitored with a UV detector at 254 nm; and the pooled fractions were concentrated using an Amicon filtration centrifuge tube (3 kDa molecular weight cutoff). The TBE buffer in the sample was exchanged with extracellular buffer, and the concentration of the RNA sample was determined using a Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer.

Whole-cell current recording

The activity of an aptamer was assayed using whole-cell recording at −60 mV and 22 °C (38, 40, 41, 66). The electrode used for whole-cell recording had a resistance of ∼3 MΩ in the intracellular electrode solution, which contains 110 mm CsF, 30 mm CsCl, 4 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm CaCl2, 5 mm EGTA and 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4, adjusted using CsOH). The extracellular buffer was described previously. For assay with NMDA channels, the electrode solution contained 140 mm CsCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm EGTA, and 10 mm HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.2 with Mg(OH)2). The extracellular solution contained 135 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 5 mm HEPES (pH 7.2 adjusted with NaOH); 100 μm glycine was added to the extracellular buffer. The glutamate induced whole-cell current was recorded using an Axopatch-200B amplifier at a cutoff frequency of 2–20 kHz, using a built in four-pole Bessel filter. The current was digitized at a sampling frequency of 5–50 kHz using a Digidata 1322A instrument from Axon Instruments. Data were collected using a pClamp 8.

Data analysis

Whole-cell current amplitude in the absence and presence of an aptamer, A/A(I), as a function of aptamer concentration was used to determine an apparent inhibition constant (KI,app) (Equation 2) (38, 40, 41, 66). Equation 2 is derived based on the assumption by which an inhibitor binds to one site on the receptor (38, 40, 41, 66). (AL2) represents the open-channel conformation with n = 2 (note that n = 2 is just an example to show the KI,app, can depend on ligand concentration, see below) (38, 40, 41, 66). I is the concentration of the inhibitor, whereas L is the ligand concentration. Φ represents the channel opening equilibrium constant.

| (Eq. 2) |

When glutamate was at a low concentration (L ≪ K1), most of the receptors in the population were in the closed-channel conformation. Under this condition, the KI we determined using Equation 2 the reflected closed-channel conformation. Likewise, when the glutamate concentration was at a saturation level (L ≫ K1), the majority of the receptors were in the open-channel conformation. Thus the KI was related to the open-channel form. Based on this rationale, we used the two ligand concentrations that corresponded to ∼4 and ∼96% fractions of the open-channel form to measure the inhibition constant for the closed- and open-channel conformations (38, 40, 41, 48, 66, 67).

Statistical data analysis

Each data point used for A/A(I) plot was an average of at least three measurements, each of which was from an individual cell. Uncertainties are representative of the standard deviation from the mean. The significance of inhibition was evaluated by a one-sample two-tailed Student's t test with the null hypothesis being H0: μ = μ0 = 1, 1 being the theoretical value of no inhibition. An asterisk indicates p ≤ 0.05, whereas the two asterisks indicate p ≤ 0.01. The difference between the open- and closed-channel forms was determined by the use of a two-sample, two-tailed, Student's t test with the null hypothesis being H0: μ1 = μ2. All analysis, including a non-linear fit for homologous competitive binding and plotting was performed using Origin 7.

Author contributions

W. J., Z. H., and L. N. designed all the experiments. W. J. and Z. H. performed all SELEX experiments; W. W., A. W., and N. K. performed all electrophysiology experiments and data analysis; W. J. and L. N. wrote the manuscript draft. All authors edited the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health NINDS Grant R01 NS060812 and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to L. N.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- EPSC

- excitatory postsynaptic current

- nt

- nucleotide

- SELEX

- systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment

- CNQX

- 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,5-dione

- NBQX

- 2,3-dihydro-6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo-f-quinoxaline.

References

- 1. Palmer C. L., Cotton L., and Henley J. M. (2005) The molecular pharmacology and cell biology of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 253–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Traynelis S. F., Wollmuth L. P., McBain C. J., Menniti F. S., Vance K. M., Ogden K. K., Hansen K. B., Yuan H., Myers S. J., and Dingledine R. (2010) Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 405–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dingledine R., Borges K., Bowie D., and Traynelis S. F. (1999) The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 51, 7–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu S., and Gouaux E. (2017) Structure and symmetry inform gating principles of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology 112, 11–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Contractor A., Mulle C., and Swanson G. T. (2011) Kainate receptors coming of age: milestones of two decades of research. Trends Neurosci. 34, 154–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bortolotto Z. A., Lauri S., Isaac J. T., and Collingridge G. L. (2003) Kainate receptors and the induction of mossy fibre long-term potentiation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 657–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keinänen K., Wisden W., Sommer B., Werner P., Herb A., Verdoorn T. A., Sakmann B., and Seeburg P. H. (1990) A family of AMPA-selective glutamate receptors. Science 249, 556–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beneyto M., and Meador-Woodruff J. H. (2004) Expression of transcripts encoding AMPA receptor subunits and associated postsynaptic proteins in the macaque brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 468, 530–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petralia R. S., and Wenthold R. J. (1992) Light and electron immunocytochemical localization of AMPA-selective glutamate receptors in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 318, 329–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martin L. J., Blackstone C. D., Huganir R. L., and Price D. L. (1993) The striatal mosaic in primates: striosomes and matrix are differentially enriched in ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits. J. Neurosci. 13, 782–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spreafico R., Frassoni C., Arcelli P., Battaglia G., Wenthold R. J., and De Biasi S. (1994) Distribution of AMPA selective glutamate receptors in the thalamus of adult rats and during postnatal development: a light and ultrastructural immunocytochemical study. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 82, 231–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wisden W., and Seeburg P. H. (1993) A complex mosaic of high-affinity kainate receptors in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 13, 3582–3598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Porter R. H., Eastwood S. L., and Harrison P. J. (1997) Distribution of kainate receptor subunit mRNAs in human hippocampus, neocortex and cerebellum, and bilateral reduction of hippocampal GluR6 and KA2 transcripts in schizophrenia. Brain Res. 751, 217–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Watanabe-Iida I., Konno K., Akashi K., Abe M., Natsume R., Watanabe M., and Sakimura K. (2016) Determination of kainate receptor subunit ratios in mouse brain using novel chimeric protein standards. J. Neurochem. 136, 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu L. J., Zhao M. G., Toyoda H., Ko S. W., and Zhuo M. (2005) Kainate receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the adult anterior cingulate cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 94, 1805–1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pinheiro P. S., Lanore F., Veran J., Artinian J., Blanchet C., Crépel V., Perrais D., and Mulle C. (2013) Selective block of postsynaptic kainate receptors reveals their function at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Cereb. Cortex 23, 323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crépel V., and Mulle C. (2015) Physiopathology of kainate receptors in epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 20, 83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mulle C., Sailer A., Pérez-Otaño I., Dickinson-Anson H., Castillo P. E., Bureau I., Maron C., Gage F. H., Mann J. R., Bettler B., and Heinemann S. F. (1998) Altered synaptic physiology and reduced susceptibility to kainate-induced seizures in GluR6-deficient mice. Nature 392, 601–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borbély S., Czégé D., Molnár E., Dobó E., Mihály A., and Világi I. (2015) Repeated application of 4-aminopyridine provoke an increase in entorhinal cortex excitability and rearrange AMPA and kainate receptors. Neurotox. Res. 27, 441–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nadler J. V. (2003) The recurrent mossy fiber pathway of the epileptic brain. Neurochem. Res. 28, 1649–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Represa A., Tremblay E., and Ben-Ari Y. (1987) Kainate binding sites in the hippocampal mossy fibers: localization and plasticity. Neuroscience 20, 739–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sutula T. P., and Dudek F. E. (2007) Unmasking recurrent excitation generated by mossy fiber sprouting in the epileptic dentate gyrus: an emergent property of a complex system. Prog. Brain Res. 163, 541–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hagihara H., Ohira K., Toyama K., and Miyakawa T. (2011) Expression of the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 is associated with granule cell maturation in the dentate gyrus. Front. Neurosci. 5, 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bliss T. V., Collingridge G. L., Kaang B. K., and Zhuo M. (2016) Synaptic plasticity in the anterior cingulate cortex in acute and chronic pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 485–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Swanson G. T. (2009) Targeting AMPA and kainate receptors in neurological disease: therapies on the horizon? Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 249–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shimizu-Sasamata M., Kawasaki-Yatsugi S., Okada M., Sakamoto S., Yatsugi S., Togami J., Hatanaka K., Ohmori J., Koshiya K., Usuda S., and Murase K. (1996) YM90K: pharmacological characterization as a selective and potent α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate/kainate receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 276, 84–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dev K. K., Petersen V., Honoré T., and Henley J. M. (1996) Pharmacology and regional distribution of the binding of 6-[3H]nitro-7-sulphamoylbenzo[f]-quinoxaline-2,3-dione to rat brain. J. Neurochem. 67, 2609–2612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jane D. E., Lodge D., and Collingridge G. L. (2009) Kainate receptors: pharmacology, function and therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology 56, 90–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nussinov R., and Tsai C. J. (2012) The different ways through which specificity works in orthosteric and allosteric drugs. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18, 1311–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sólyom S., and Tarnawa I. (2002) Non-competitive AMPA antagonists of 2,3-benzodiazepine type. Curr. Pharm. Des. 8, 913–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellington A. D., and Szostak J. W. (1990) In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346, 818–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tuerk C., and Gold L. (1990) Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249, 505–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sullenger B. A., and Nair S. (2016) From the RNA world to the clinic. Science 352, 1417–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McConnell E. M., Holahan M. R., and DeRosa M. C. (2014) Aptamers as promising molecular recognition elements for diagnostics and therapeutics in the central nervous system. Nucleic Acid Ther. 24, 388–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wenthold R. J., Petralia R. S., Blahos J. II, and Niedzielski A. S. (1996) Evidence for multiple AMPA receptor complexes in hippocampal CA1/CA2 neurons. J. Neurosci. 16, 1982–1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shi S., Hayashi Y., Esteban J. A., and Malinow R. (2001) Subunit-specific rules governing AMPA receptor trafficking to synapses in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Cell 105, 331–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu W., Shi Y., Jackson A. C., Bjorgan K., During M. J., Sprengel R., Seeburg P. H., and Nicoll R. A. (2009) Subunit composition of synaptic AMPA receptors revealed by a single-cell genetic approach. Neuron 62, 254–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang Z., Pei W., Jayaseelan S., Shi H., and Niu L. (2007) RNA aptamers selected against the GluR2 glutamate receptor channel. Biochemistry 46, 12648–12655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Swillens S. (1995) Interpretation of binding curves obtained with high receptor concentrations: practical aid for computer analysis. Mol. Pharmacol. 47, 1197–1203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang Z., Han Y., Wang C., and Niu L. (2010) Potent and selective inhibition of the open-channel conformation of AMPA receptors by an RNA aptamer. Biochemistry 49, 5790–5798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park J. S., Wang C., Han Y., Huang Z., and Niu L. (2011) Potent and selective inhibition of a single α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor subunit by an RNA aptamer. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 15608–15617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Domingues A., Cunha Oliveira T., Laço M. L., Macedo T. R., Oliveira C. R., and Rego A. C. (2006) Expression of NR1/NR2B N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors enhances heroin toxicity in HEK293 cells. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1074, 458–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhou N., Hammerland L. G., and Parks T. N. (1993) γ-d-glutamylaminomethyl sulfonic acid (GAMS) distinguishes kainic acid- from AMPA-induced responses in Xenopus oocytes expressing chick brain glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology 32, 767–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Davies J., and Watkins J. C. (1983) Role of excitatory amino acid receptors in mono- and polysynaptic excitation in the cat spinal cord. Exp. Brain Res. 49, 280–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davies J., and Watkins J. C. (1985) Depressant actions of γ-d-glutamylaminomethyl sulfonate (GAMS) on amino acid-induced and synaptic excitation in the cat spinal cord. Brain Res. 327, 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wilding T. J., and Huettner J. E. (1996) Antagonist pharmacology of kainate- and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid-preferring receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 49, 540–546 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Raigorodsky G., and Urca G. (1990) Spinal antinociceptive effects of excitatory amino acid antagonists: quisqualate modulates the action of N-methyl-d-aspartate. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 182, 37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ritz M., Micale N., Grasso S., and Niu L. (2008) Mechanism of inhibition of the GluR2 AMPA receptor channel opening by 2,3-benzodiazepine derivatives. Biochemistry 47, 1061–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Calias P., Banks W. A., Begley D., Scarpa M., and Dickson P. (2014) Intrathecal delivery of protein therapeutics to the brain: a critical reassessment. Pharmacol. Ther. 144, 114–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wallace M. S. (2006) Ziconotide: a new nonopioid intrathecal analgesic for the treatment of chronic pain. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 6, 1423–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. van Zundert B., and Brown R. H. Jr. (2017) Silencing strategies for therapy of SOD1-mediated ALS. Neurosci. Lett. 636, 32–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Keefe A. D., Pai S., and Ellington A. (2010) Aptamers as therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 537–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sommer B., Köhler M., Sprengel R., and Seeburg P. H. (1991) RNA editing in brain controls a determinant of ion flow in glutamate-gated channels. Cell 67, 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Seeburg P. H. (1996) The role of RNA editing in controlling glutamate receptor channel properties. J. Neurochem. 66, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burnashev N., Monyer H., Seeburg P. H., and Sakmann B. (1992) Divalent ion permeability of AMPA receptor channels is dominated by the edited form of a single subunit. Neuron 8, 189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Greger I. H., Khatri L., Kong X., and Ziff E. B. (2003) AMPA receptor tetramerization is mediated by Q/R editing. Neuron. 40, 763–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Swanson G. T., Kamboj S. K., and Cull-Candy S. G. (1997) Single-channel properties of recombinant AMPA receptors depend on RNA editing, splice variation, and subunit composition. J. Neurosci. 17, 58–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Koike M., Tsukada S., Tsuzuki K., Kijima H., and Ozawa S. (2000) Regulation of kinetic properties of GluR2 AMPA receptor channels by alternative splicing. J. Neurosci. 20, 2166–2174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mansour M., Nagarajan N., Nehring R. B., Clements J. D., and Rosenmund C. (2001) Heteromeric AMPA receptors assemble with a preferred subunit stoichiometry and spatial arrangement. Neuron 32, 841–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rozov A., Zilberter Y., Wollmuth L. P., and Burnashev N. (1998) Facilitation of currents through rat Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptor channels by activity-dependent relief from polyamine block. J. Physiol. 511, 361–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Geiger J. R., Melcher T., Koh D. S., Sakmann B., Seeburg P. H., Jonas P., and Monyer H. (1995) Relative abundance of subunit mRNAs determines gating and Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors in principal neurons and interneurons in rat CNS. Neuron 15, 193–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bowie D., and Mayer M. L. (1995) Inward rectification of both AMPA and kainate subtype glutamate receptors generated by polyamine-mediated ion channel block. Neuron 15, 453–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schiffer H. H., Swanson G. T., Masliah E., and Heinemann S. F. (2000) Unequal expression of allelic kainate receptor GluR7 mRNAs in human brains. J. Neurosci. 20, 9025–9033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Clements J. D., Feltz A., Sahara Y., and Westbrook G. L. (1998) Activation kinetics of AMPA receptor channels reveal the number of functional agonist binding sites. J. Neurosci. 18, 119–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hulme E. C., and Trevethick M. A. (2010) Ligand binding assays at equilibrium: validation and interpretation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 161, 1219–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huang Z., Jayaseelan S., Hebert J., Seo H., and Niu L. (2013) Single-nucleotide resolution of RNAs up to 59 nucleotides by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 435, 35–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ritz M., Wang C., Micale N., Ettari R., and Niu L. (2011) Mechanism of inhibition of the GluA2 AMPA receptor channel opening: the role of 4-methyl versus 4-carbonyl group on the diazepine ring of 2,3-benzodiazepine derivatives. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2, 506–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.