Abstract

Objective

To examine whether activity limitation stages are associated with admission to facilities providing long-term care (LTC).

Design

Cohort study using Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey data from the 2005–2009 entry panels. In all, 14,580 community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries 65 years of age and older were included. Proportional subhazard models examined associations between activity limitation stages and time to first LTC admission, adjusting for baseline sociodemographics and health conditions.

Results

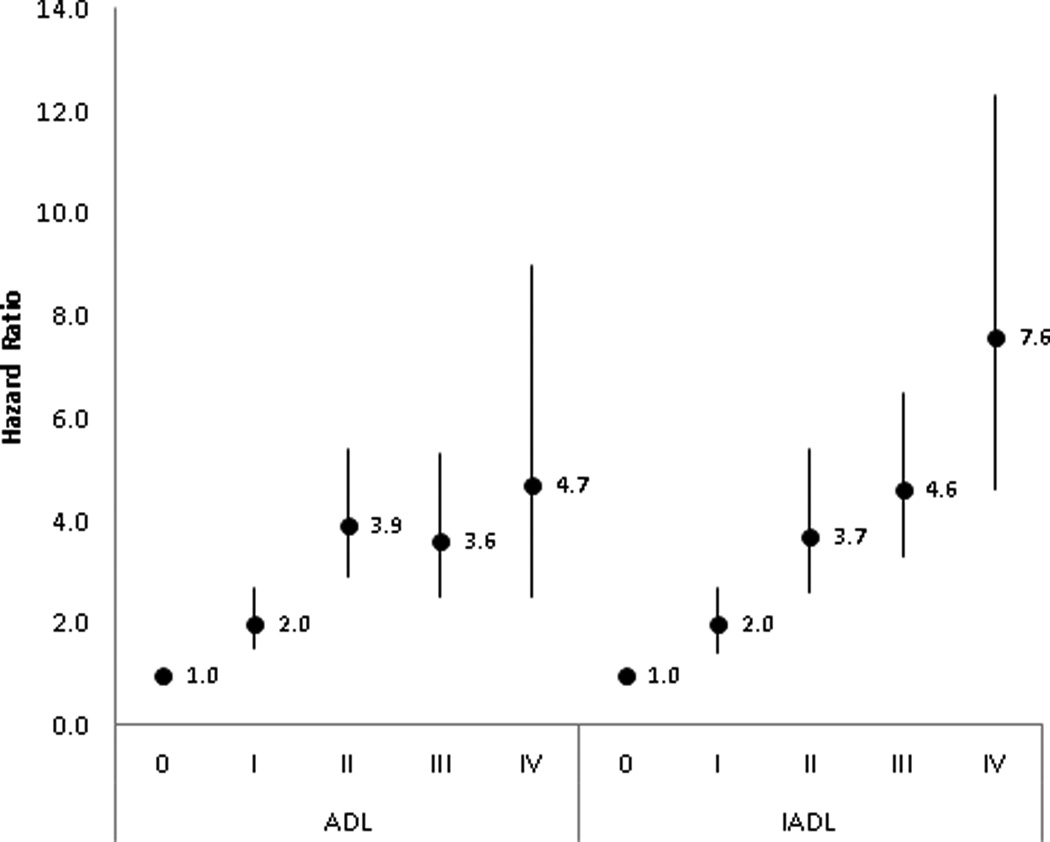

The weighted annual rate of LTC admission was 1.1 %. In the adjusted model, compared to activity of daily living (ADL) stage 0, the hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) were 2.0 (1.5–2.7), 3.9 (2.9–5.4), 3.6 (2.5–5.3), and 4.7 (2.5–9.0) for ADL stage I (mild limitation), ADL stage II (moderate limitation), ADL stage III (severe limitation), and ADL stage IV (complete limitation), respectively. Compared to instrumental ADL (IADL) stage 0, the hazard ratios and 95% CIs for IADL stages I–IV were 2.0 (1.4–2.7), 3.7 (2.6–5.4), 4.6 (3.3–6.5), and 7.6 (4.6–12.3), respectively.

Conclusions

Activity limitation stages are strongly associated with future admission to LTC, and may therefore be useful in identifying specific supportive care needs among vulnerable older community-dwelling adults, which may reduce or delay need for admission to LTC.

Keywords: Disability evaluation, Medicare, Long-term care, Aged

INTRODUCTION

Facilities providing long-term care (LTC) encompasses a variety of medical and non-medical services that elderly people with disabilities or chronic illnesses may need to meet their person care needs.1 LTC provides assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) (i.e., eating, toileting, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (i.e., using the telephone, managing money, and preparing meals). Care can be provided during either short or long periods of time, and in different places by various caregivers. For example, LTC can be provided in nursing homes, adult day care centers, assisted living facilities, in the community, or at home.2

Admission to LTC becomes increasingly common at advanced ages3–6 and is predicted by poor health, female gender, lower income, being single, prior falls, presence of cognitive impairment, and lifestyle-related factors such as smoking, inactivity, and obesity.4,5,7–13 Disability also predicts admission to LTC. ADLs and IADLs are often used in assessments of need for LTC. Simple counts of limitations in ADLs and IADLs are associated with admission to LTC.4–10,14,15 Previous studies have found that older community-dwelling adults with three or more ADL limitations compared to a count of one or two limitations are more likely to be admitted to LTC.5,6,8,14 One study showed a monotonic relationship between the number of ADLs for which individuals needed help and the risk of admission to LTC.6 In addition, greater difficulty performing IADLs are associated with admission to LTC.4

Because disability has already been shown to be associated with mortality,16–18 falls risk,19,20 patient satisfaction,21 and hospital readmission,22 a better understanding of the relationship between disability and admission to LTC may highlight needs for specific supportive care for vulnerable older community-dwelling adults. However, even though older adults with more ADL limitations are assumed to have more severe disabilities and need more support, simple counts do not convey information about the particular activities that older adults are able to perform without difficulty. For example, person A has difficulty eating and toileting while person B has difficulty walking and getting in/out of a bed. Although these two people have the same count of limitations, the patterns of their limitations are very distinct and different from each other, which require different planning and care coordination. A recent article by Fong et al. calls attention to the fact that knowing just the number of limitations is not enough and there is a need to look past simple counts of ADL limitations to be able to inform clinicians which limitations specifically cause the need for LTC.14 Thus, activity limitation stages were developed to represent both the severity and types of limitations experienced, and to specify clinically meaningful patterns of increasing difficulty with self-care items.23,24 Inspired by the TNM (tumor, nodes, metastasis) cancer staging system and its applications,25 which attests to the value of incorporating different domains in cancer staging to understand the status and prognosis of people with different types of cancer, different domains are incorporated in these disability staging systems to better characterize the status, prognosis, and needs of people with different types of disabilities. The activity limitation staging structure reflects two concepts essential to understanding the implications of activity limitation: the domain (ADL and IADL) and the particular activities limited within that domain. Although counts of limitations are the simplest and most easily derived measure of severity, activity limitation staging may have more utility to clinicians because it provides population-level benchmark profiles that classify people in ways that are more clinically interpretable than other population-level aggregated disability measures.24 These disability profiles can inform clinicians specifically which activities people have difficulty with rather than just the number of activities that are limited. Further, understanding the amount of difficulty that an individual experiences when performing each activity in the context of the overall severity of disability may help to explain the relative importance of specific types of functional limitations in predicting admission to LTC.

The aim of the present study was to examine whether and how activity limitation stages are associated with time to first LTC admission. The hypotheses included that persons 65 years of age and older with any limitations in ADLs (ADL stage I or higher) would be more likely to be admitted to facilities providing LTC compared to those without ADL limitations and that persons 65 years of age and older with any limitations in IADLs (IADL stage I or higher) would be more likely to be admitted to facilities providing LTC compared to those without IADL limitations.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania. Consent was not required due to the use of administrative data. This study conforms to all STROBE guidelines and reports the required information according to cohort studies (see Supplementary Checklist).

Data source

Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), a systematic, representative population-based survey conducted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) were used.26–28 Survey weights are used to account for non-response, and the MCBS oversamples those 80 years and older because of their special needs.27 Sample persons or their proxies are interviewed about their functioning and health conditions during the autumn of their entry year into the survey and each subsequent autumn, and about their health care utilization starting January 1st following their autumn interview. Each beneficiary or proxy is interviewed periodically over four years (entry year and the following three years).

Study cohort

The baseline sample was defined from the entry panels of the 2005–2009 MCBS Cost and Use files (n=14,580), and only included community-dwelling beneficiaries 65 years of age and older.

Study Outcome

The outcome was time to LTC admission within the year following each autumn interview. Time to admission to facilities providing LTC, either short-or long-stay, was determined from the time between the autumn interview to the date of admission to LTC during the following year. Admission to LTC information was obtained from the 2006–2010 residential timeline record in the Cost and Use files. The MCBS uses a broad definition for LTC, including licensed nursing homes and other long-term care facilities such as retirement homes, domiciliary or personal care facilities, mental health or mental retardation facilities, continuing care facilities, assisted living facilities, and rehabilitation facilities. LTC facilities must have three or more LTC beds and provide continuous supervision, personal care, or long-term care.28 Long-term care does not include admissions to skilled nursing facilities or inpatient rehabilitation facilities because those admissions are not necessarily captured using the residential timeline record. Thus, the only admissions that are included in our study as the outcome are the ones obtained from the residential timeline record and that are part of the MCBS’s broad definition of LTC.

Primary variables of interest

The primary variables of interest in this study were activity limitation stages, which have been described previously.23,24 In brief, activity limitation stages define the person’s preserved and limited activities within two domains, ADLs and IADLs. Each domain includes six activities. The ADL items are eating, toileting, dressing, bathing/showering, getting in or out of bed/chairs, and walking. The IADL items are using the telephone, managing money, preparing meals, doing light housework, shopping for personal items, and doing heavy housework. The sample person or proxy answers questions based on the level of difficulty a person has on performing the six activities in a given domain. There are a total of five stages within each domain: 0-no limitation, I-mild limitation, II-moderate limitation, and IV-complete limitation. Thus, higher numbered stages reflect greater disability and less preserved function except for stage III (severe limitation) which is designed to be the non-fitting stage. The staging systems were constructed such that if a task is difficult to perform at a lower stage, it tends to remain difficult at more severe stages, except for the non-fitting stage III, which accommodates patterns of limitation that are atypical of the hierarchy. At ADL stage 0, beneficiaries have no difficulty doing any of the ADL items as listed above. At ADL stage I, a person may have difficulty getting in/out of a bed or chair and/or walking, but has no difficulty eating, toileting, dressing, or bathing/showering. Beneficiaries at ADL stage II may have difficulty dressing, bathing/showering, getting in/out of a bed or chair, and/or walking, but do not have difficulty eating or toileting. At ADL stage III, a person may have difficulty eating and/or toileting but does not have difficulty with all the ADL items. At ADL stage IV, a person will have difficulty performing all ADLs. At IADL stage 0, beneficiaries have no difficulty doing any of the IADL items as listed above. At IADL stage I, people may begin to have difficulty shopping and/or doing heavy housework, but there is no difficulty using the telephone, managing money, preparing meals, or doing light housework. Beneficiaries may have difficulty preparing meals, doing light housework, shopping, and/or doing heavy housework at IADL stage II, but do not have difficulty using the telephone or managing money. At IADL stage III, people may have difficulty using the telephone and/or managing money, but do not have difficulty with all the IADLs. At stage IV, there is difficulty performing all the IADL items.24

Covariates

Sociodemographic variables were age (65–74, 75–84, or ≥85), sex, and race or ethnic group (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other). Education was coded as below high school graduate or high school graduate or higher. Living arrangement was categorized as lives alone, lives with spouse, lives with children, or other. Dual eligibility was categorized as Medicare and Medicaid dual enrollee versus Medicare alone. An indicator for proxy use versus self-respondent was included.

Health conditions included comorbidities or events that a doctor had told the beneficiary were present or that occurred within the past year. With some conditions noted in table 1, the timing of diagnoses were also measured, i.e., diagnosis within the past year or more than a year ago. The medical conditions were Alzheimer’s disease, amputation, angina or coronary artery diseases, arthritis other than rheumatoid, broken hip, cancer other than skin, congestive heart failure, depression, diabetes type 1, 2, or other, emphysema/asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hardening of the arteries, heart rhythm disease, heart valve disease, hypertension, incontinence/catheterization, mental or psychiatric conditions, mental retardation, myocardial infarction, osteoporosis, paralysis, Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and stroke.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries 65 Years of Age and Older Stratified by Activity of Daily Living and Instrumental Activity of Daily Living Stages

| Baseline Characteristic* | Activity of Daily Living Stage | Instrumental Activity of Daily Living Stage | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=1457 3) |

0 (n=1031 3) |

I (n=2350 ) |

II (n=1035 ) |

III (n=749 ) |

IV (n=108 ) |

p- value |

0 (n=9414 ) |

I (n=2416 ) |

II (n=1026 ) |

III (n=1416 ) |

IV (n=153 ) |

p- value |

||

|

Facilities providing long-term care admissions |

458 (1.1) | 139 (0.5) | 89 (1.5) | 128 (4.7) |

76 (4.6) |

26 (9.9) |

<.000 1 |

96 (0.4) | 72 (1.1) | 66 (2.6) | 146 (4.3) |

78 (12) | <.000 1 |

|

| Deaths | 754 (2.0) | 309 (1.1) | 161 (2.9) |

128 (5.1) |

112 (6.5) |

44 (15.8) |

<.000 1 |

229 (0.9) |

139 (2.3) |

119 (4.9) |

177 (5.2) |

89 (13.6) |

<.000 1 |

|

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||||||

|

Age |

65–74 | 6714 (58.5) |

5305 (63.6) |

831 (46.6) |

320 (40.0) |

228 (41.2) |

30 (40.7) |

<.000 1 |

4943 (64.6) |

977 (50.7) |

347 (44.9) |

392 (37.9) |

55 (29.9) |

<.000 1 |

| 75–84 | 5837 (32.4) |

3952 (30.0) |

1063 (39.3) |

462 (40.0) |

312 (37.4) |

48 (38.3) |

3597 (29.6) |

1049 (36.8) |

466 (39.7) |

629 (40.4) |

95 (36.2) |

|||

| ≥85 | 2022 (9.1) |

1056 (6.4) |

456 (14.1) |

271 (20.0) |

209 (21.4) |

30 (21.1) |

874 (5.8) |

435 (12.5) |

213 (15.4) |

395 (21.6) |

103 (33.9) |

|||

| Sex | Male | 6344 (44.1) |

4784 (46.5) |

905 (39.2) |

357 (34.6) |

256 (34.0) |

42 (39.1) |

<.000 1 |

4672 (49.5) |

635 (26.0) |

295 (28.0) |

658 (48.0) |

84 (35.1) |

<.000 1 |

| Female | 8229 (55.9) |

5529 (53.5) |

1445 (60.8) |

696 (65.4) |

493 (66.0) |

66 (60.9) |

4742 (50.5) |

1826 (74.0) |

731 (72.0) |

758 (52.0) |

169 (64.9) |

|||

|

Race/ethnic group |

Non-Hispanic White | 11908 (81.5) |

8584 (82.9) |

1894 (79.6) |

814 (76.9) |

549 (73.2) |

67 (61.1) |

<.000 1 |

7864 (82.9) |

2025 (82.3) |

757 (73.0) |

1093 (76.6) |

167 (66.5) |

<.000 1 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1162 (7.8) |

740 (7.2) |

203 (8.4) |

122 (11.2) |

86 (10.7) |

11 (10.0) |

693 (7.5) |

198 (7.4) |

118 (10.9) |

117 (7.6) |

36 (14.7) |

|||

| Hispanic | 1125 (7.8) |

737 (7.1) |

186 (8.7) |

88 (8.7) |

90 (12.5) |

24 (23.8) |

649 (7.0) |

173 (7.5) |

109 (11.1) |

153 (11.6) |

41 (15.0) |

|||

| Other | 378 (3.0) |

252 (2.8) |

67 (3.3) |

29 (3.2) |

24 (3.6) |

* | 208 (2.6) |

65 (2.9) |

42 (5.0) |

53 (4.2) |

* | |||

| Education | High school or above | 10773 (76.7) |

8011 (80.0) |

1585 (69.6) |

672 (66.6) |

456 (62.7) |

49 (49.1) |

<.000 1 |

7432 (81.1) |

1736 (72.9) |

646 (64.4) |

833 (60.6) |

127 (52.7) |

<.000 1 |

| Below high school graduate |

3732 (23.3) |

2269 (20.0) |

753 (30.4) |

370 (33.4) |

284 (37.3) |

56 (50.9) |

1956 (18.9) |

721 (27.1) |

371 (35.6) |

563 (39.4) |

118 (47.3) |

|||

| Living arrangement | Alone | 4723 (29.9) |

3250 (28.9) |

828 (32.7) |

371 (33.8) |

246 (30.9) |

28 (28.8) |

<.000 1 |

2942 (28.7) |

938 (35.1) |

361 (33.3) |

424 (28.3) |

55 (20.9) |

<.000 1 |

| With spouse | 7666 (56.0) |

5838 (59.6) |

1074 (48.5) |

410 (41.0) |

297 (42.6) |

47 (43.3) |

5432 (60.5) |

1068 (47.0) |

428 (43.7) |

653 (48.6) |

86 (36.9) |

|||

| With children | 1444 (8.9) |

775 (6.9) |

311 (12.6) |

190 (16.9) |

143 (17.3) |

25 (19.5) |

630 (6.3) |

317 (12.1) |

159 (14.4) |

256 (16.9) |

81 (29.6) |

|||

| Other | 740 (5.2) |

450 (4.5) |

137 (6.2) |

82 (8.2) |

63 (9.3) |

* | 410 (4.5) |

138 (5.8) |

78 (8.7) |

83 (6.1) |

31 (12.6) |

|||

| Dual eligibility | Medicare alone | 12560 (87.3) |

9273 (90.7) |

1914 (81.8) |

769 (73.6) |

542 (72.8) |

62 (56.3) |

<.000 1 |

8592 (91.9) |

2019 (82.7) |

738 (72.1) |

1062 (75.1) |

147 (57.3) |

<.000 1 |

| Medicare and Medicaid dual enrollee |

2013 (12.7) |

1040 (9.3) |

436 (18.2) |

284 (26.4) |

207 (27.2) |

46 (43.7) |

822 (8.1) |

442 (17.3) |

288 (27.9) |

354 (24.9) |

106 (42.7) |

|||

| Proxy respondent | Self-respondent | 13633 (94.1) |

9833 (95.4) |

2210 (94.4) |

926 (89.8) |

603 (82.5) |

61 (61.3) |

<.000 1 |

9069 (96.2) |

2380 (96.8) |

946 (92.5) |

1118 (80.5) |

119 (47.9) |

<.000 1 |

| Proxy-respondent | 940 (5.9) | 480 (4.6) | 140 (5.6) |

127 (10.2) |

146 (17.5) |

47 (38.7) |

345 (3.8) |

81 (3.2) | 80 (7.5) | 298 (19.5) |

134 (52.1) |

|||

| Health conditions | ||||||||||||||

|

Alzheimer’s disease |

No | 14250 (98.3) |

10186 (99.0) |

2304 (98.3) |

982 (94.3) |

693 (93.6) |

85 (81.5) |

<.0001 |

9351 (99.5) |

2441 (99.3) |

1011 (98.6) |

1276 (91.0) |

169 (68.5) |

<.0001 |

| Yes | 323 (1.7) |

127 (1.0) |

46 (1.7) |

71 (5.7) |

56 (6.4) |

23 (18.5) |

63 (0.5) |

20 (0.7) |

15 (1.4) |

140 (9.0) | 84 (31.5) |

|||

|

Amputation |

No | 14484 (99.4) |

10282 (99.7) |

2327 (98.9) |

1039 (98.4) |

730 (97.7) |

106 (98.9) |

<.0001 |

9378 (99.6) |

2441 (99.2) |

1017 (99.0) |

1399 (98.9) |

246 (97.5) |

<.0001 |

| Yes | 89 (0.6) |

31 (0.3) |

23 (1.1) |

14 (1.6) |

19 (2.3) |

* | 36 (0.4) |

20 (0.8) |

* | 17 (1.1) |

* | |||

| Angina or coronary artery diseases |

No | 13203 (91.3) |

9505 (92.7) |

2050 (87.7) |

906 (86.2) |

654 (87.7) |

88 (83.8) |

<.0001 |

8696 (92.8) |

2165 (88.4) |

891 (87.3) |

1239 (88.0) |

208 (82.5) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 876 (5.5) |

559 (5.0) |

183 (7.3) |

71 (6.6) |

52 (6.8) |

11 (9.0) |

502 (4.9) |

172 (6.7) | 76 (6.6) |

100 (6.7) | 27 (10.7) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 494 (3.2) |

249 (2.3) |

117 (5.0) |

76 (7.2) |

43 (5.5) |

* | 216 (2.2) |

124 (4.9) | 59 (6.1) |

77 (5.3) |

18 (6.8) |

|||

|

Arthritis other than rheumatoid |

No | 7725 (54.6) |

6129 (60.7) |

864 (36.5) |

411 (39.3) |

274 (36.1) |

47 (43.3) |

<.0001 |

5674 (61.7) |

889 (35.7) |

358 (34.3) |

680 (48.2) |

122 (49.4) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 1759 (11.9) |

1235 (11.7) |

311 (13.4) |

115 (10.7) |

88 (12.0) |

* | 1107 (11.5) |

332 (13.4) |

132 (12.7) |

160 (11.9) |

27 (10.1) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 5089 (33.5) |

2949 (27.6) |

1175 (50.1) |

527 (49.9) |

387 (51.9) |

51 (47.4) |

2633 (26.8) |

1240 (50.9) |

536 (53.0) |

576 (39.9) |

104 (40.5) |

|||

|

Brokenhip |

No | 14070 (97.2) |

10139 (98.6) |

2203 (94.5) |

957 (91.9) |

676 (91.1) |

95 (88.9) |

<.0001 |

9257 (98.6) |

2339 (95.7) |

941 (92.4) |

1312 (93.7) |

219 (87.1) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 403 (2.3) |

152 (1.2) |

122 (4.6) |

62 (5.3) |

59 (7.1) |

* | 129 (1.1) |

106 (3.8) | 64 (5.9) |

80 (5.0) |

24 (8.9) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 100 (0.5) |

22 (0.2) |

25 (0.9) |

34 (2.8) |

14 (1.7) |

* | 28 (0.3) |

16 (0.5) |

21 (1.7) |

24 (1.3) |

* | |||

| Cancer other than skin | No | 11992 (83.3) |

8591 (84.3) |

1881 (81.3) |

846 (80.6) |

582 (76.7) |

92 (84.7) |

<.0001 |

7867 (84.7) |

1960 (80.1) |

815 (79.7) |

1132 (80.0) |

215 (85.0) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 1855 (12.0) |

1248 (11.4) |

337 (13.3) |

145 (13.4) |

117 (16.0) |

* | 1103 (10.9) |

381 (15.1) |

136 (13.4) |

205 (14.3) |

31 (12.1) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 726 (4.7) |

474 (4.3) |

132 (5.4) |

62 (6.0) |

50 (7.2) |

* | 444 (4.4) |

120 (4.8) | 75 (6.9) |

79 (5.7) |

* | |||

|

Congestive heart failure |

No | 13663 (94.6) |

9902 (96.5) |

2118 (90.9) |

915 (87.2) |

635 (85.9) |

93 (88.6) |

<.0001 |

9103 (97.1) |

2207 (90.3) |

885 (87.4) |

1256 (89.5) |

209 (83.5) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 553 (3.4) |

290 (2.5) |

136 (5.5) |

64 (6.3) |

57 (7.2) |

* | 220 (2.1) |

160 (6.1) | 63 (6.0) |

87 (5.9) |

22 (8.4) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 357 (2.0) |

121 (1.0) |

96 (3.6) |

74 (6.5) |

57 (6.9) |

* | 91 (0.8) |

94 (3.6) |

78 (6.6) |

73 (4.7) |

22 (8.1) |

|||

| Depression | No | 12336 (84.7) |

9153 (88.6) |

1853 (77.6) |

738 (68.5) |

530 (69.1) |

62 (55.0) |

<.0001 | 8493 (89.9) |

1915 (76.6) |

721 (68.2) |

1052 (72.9) |

154 (60.9) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 991 (6.9) |

577 (5.8) |

220 (10.0) |

118 (11.8) |

67 (9.1) |

* | 496 (5.6) |

226 (9.5) | 115 (11.5) |

126 (9.4) | 27 (10.6) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 1246 (8.4) |

583 (5.6) |

277 (12.3) |

197 (19.7) |

152 (21.8) |

37 (33.6) |

425 (4.5) |

320 (13.9) |

190 (20.3) |

238 (17.7) |

72 (28.5) |

|||

| Diabetes | No | 11137 (76.5) |

8266 (80.0) |

1630 (68.9) |

682 (62.5) |

493 (63.7) |

66 (60.6) |

<.0001 |

7531 (79.9) |

1770 (71.2) |

661 (63.9) |

1003 (69.3) |

168 (64.0) |

<.0001 |

| Type 1 | 310 (2.0) |

140 (1.2) |

81 (3.7) |

58 (5.8) |

25 (3.5) |

* | 124 (1.2) |

66 (2.9) |

57 (5.6) |

49 (3.4) |

15 (6.5) |

|||

| Type 2 D | 2358 (16.2) |

1401 (13.7) |

486 (21.1) |

260 (26.6) |

181 (25.0) |

30 (28.5) |

1286 (13.7) |

496 (20.7) |

248 (24.5) |

277 (21.0) |

51 (22.7) |

|||

| Other type | 768 (5.4) |

506 (5.1) |

153 (6.3) |

53 (5.1) |

50 (7.9) |

* | 473 (5.2) |

129 (5.2) | 60 (5.9) |

87 (6.3) |

19 (6.8) |

|||

| Emphysema/asthma/chro nic obstructive pulmonary disease |

No | 12576 (86.4) |

9187 (89.2) |

1879 (78.8) |

840 (79.5) |

582 (76.3) |

88 (78.7) |

<.0001 |

8451 (89.8) |

1980 (79.6) |

773 (74.0) |

1161 (81.7) |

209 (82.0) |

<.0001 |

| Yes | 1997 (13.6) |

1126 (10.8) |

471 (21.2) |

213 (20.5) |

167 (23.7) |

20 (21.3) |

963 (10.2) |

481 (20.4) |

253 (26.0) |

255 (18.3) |

44 (18.0) |

|||

|

Hardening of the arteries |

No | 13442 (93.0) |

9646 (94.2) |

2109 (90.1) |

941 (89.3) |

656 (88.3) |

90 (84.8) |

<.0001 |

8854 (94.7) |

2204 (89.8) |

915 (89.9) |

1248 (88.1) |

218 (86.0) |

<.0001 |

| Yes | 1131 (7.0) |

667 (5.8) |

241 (9.9) |

112 (10.7) |

93 (11.7) |

18 (15.2) |

560 (5.3) |

257 (10.2) |

111 (10.1) |

168 (11.9) |

35 (14.0) |

|||

|

Heart rhythm disease |

No | 12053 (84.2) |

8778 (86.3) |

1822 (78.7) |

820 (78.9) |

551 (74.8) |

82 (79.2) |

<.0001 |

8092 (87.0) |

1899 (78.4) |

752 (74.5) |

1109 (79.8) |

196 (79.1) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 1291 (8.1) |

851 (7.6) |

249 (10.1) |

94 (8.1) |

89 (11.6) |

* | 761 (7.5) |

255 (9.5) |

111 (10.3) |

142 (9.3) |

24 (9.0) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 1229 (7.7) |

684 (6.1) |

279 (11.2) |

139 (13.1) |

109 (13.6) |

18 (14.3) |

561 (5.5) |

307 (12.1) |

163 (15.2) |

165 (10.9) |

33 (11.9) |

|||

|

Heart valve disease |

No | 13416 (92.7) |

9609 (93.8) |

2100 (89.7) |

940 (89.7) |

668 (89.5) |

99 (91.8) |

<.0001 |

8819 (94.2) |

2186 (88.9) |

907 (89.5) |

1269 (90.0) |

232 (91.9) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 728 (4.7) |

463 (4.1) |

146 (6.2) |

69 (6.5) |

43 (5.7) |

* | 406 (3.9) |

163 (6.8) |

64 (5.6) |

80 (5.7) |

15 (5.8) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 429 (2.6) |

241 (2.1) |

104 (4.1) |

44 (3.7) |

38 (4.8) |

* | 189 (1.8) |

112 (4.3) |

55 (4.9) |

67 (4.3) |

* | |||

|

Hypertension |

No | 5474 (39.4) |

4277 (43.3) |

650 (28.2) |

307 (28.9) |

217 (29.3) |

23 (23.1) |

<.0001 |

4003 (44.1) |

680 (28.9) |

257 (26.0) |

441 (31.2) |

93 (37.6) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 1828 (12.5) |

1318 (12.5) |

303 (13.3) |

110 (10.1) |

85 (11.8) |

12 (10.6) |

1232 (12.9) |

297 (12.0) |

122 (12.3) |

153 (10.7) |

24 (9.5) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 7271 (48.1) |

4718 (44.2) |

1397 (58.5) |

636 (61.1) |

447 (59.0) |

73 (66.3) |

4179 (43.0) |

1484 (59.2) |

647 (61.7) |

822 (58.2) |

136 (52.9) |

|||

|

Incontinence |

No | 10051 (71.3) |

7802 (77.3) |

1392 (60.3) |

509 (49.2) |

323 (44.1) |

25 (22.4) |

<.0001 |

7268 (78.7) |

1349 (55.8) |

535 (53.3) |

805 (58.1) |

91 (36.8) |

<.0001 |

| Dialysis/catheterizat ion |

4453 (28.3) |

2492 (22.5) |

947 (39.3) |

536 (50.0) |

403 (52.6) |

75 (71.7) |

2135 (21.2) |

1093 (43.2) |

480 (45.6) |

597 (41.0) |

148 (58.4) |

|||

| Yes | 69 (0.4) |

19 (0.2) |

11 (0.5) |

* | 23 (3.3) |

* | 11 (0.1) |

19 (0.9) |

11 (1.1) |

14 (0.9) |

14 (4.9) |

|||

| Mental or psychiatric conditions |

No | 14362 (98.5) |

10199 (98.8) |

2310 (98.1) |

1020 (96.6) |

731 (97.6) |

102 (94.5) |

<.0001 |

9330 (99.0) |

2425 (98.4) |

1000 (96.9) |

1361 (95.7) |

243 (96.1) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 74 (0.5) |

48 (0.5) |

11 (0.5) |

* | * | * | 32 (0.3) |

17 (0.7) |

* | 15 (1.2) |

* | |||

| ≤ 1 year | 137 (1.0) |

66 (0.8) |

29 (1.3) |

26 (2.6) |

12 (1.5) |

* | 52 (0.6) |

19 (0.9) |

17 (2.0) |

40 (3.1) |

* | |||

|

Mental retardation |

No | 14524 (99.7) |

10295 (99.8) |

2342 (99.6) |

1041 (98.7) |

740 (98.6) |

106 (98.1) |

<.0001 |

9397 (99.8) |

2459 (99.9) |

1021 (99.5) |

1400 (98.6) |

244 (95.8) |

<.0001 |

| Yes | 49 (0.3) |

18 (0.2) |

* | 12 (1.3) |

* | * | 17 (0.2) |

* | * | 16 (1.4) |

* | |||

|

Myocardial infarction |

No | 12689 (88.2) |

9229 (90.5) |

1903 (81.9) |

875 (83.2) |

597 (80.5) |

85 (79.7) |

<.0001 |

8430 (90.6) |

2067 (84.8) |

827 (81.2) |

1158 (81.5) |

203 (80.8) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 1624 (10.1) |

957 (8.4) |

382 (15.1) |

146 (13.9) |

123 (15.7) |

16 (14.6) |

873 (8.3) |

336 (12.6) |

153 (14.3) |

221 (16.0) |

42 (16.2) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 260 (1.7) |

127 (1.1) |

65 (3.0) |

32 (2.9) |

29 (3.8) |

* | 111 (1.1) |

58 (2.6) |

46 (4.5) |

37 (2.4) |

* | |||

|

Osteoporosis |

No | 12011 (83.5) |

8766 (85.8) |

1818 (78.1) |

786 (74.6) |

563 (75.7) |

78 (74.4) |

<.0001 |

8159 (87.3) |

1790 (73.7) |

746 (72.4) |

1123 (79.7) |

191 (76.6) |

<.0001 |

| Yes | 2562 (16.5) |

1547 (14.2) |

532 (21.9) |

267 (25.4) |

186 (24.3) |

30 (25.6) |

1255 (12.7) |

671 (26.3) |

280 (27.6) |

293 (20.3) |

62 (23.4) |

|||

|

Paralysis |

No | 14244 (97.9) |

10206 (99.0) |

2279 (96.9) |

992 (94.1) |

683 (91.1) |

84 (78.3) |

<.0001 |

9320 (99.0) |

2395 (97.3) |

962 (93.6) |

1349 (95.2) |

215 (85.5) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 193 (1.3) | 86 (0.8) |

50 (2.1) |

29 (2.6) |

26 (3.9) |

* | 76 (0.8) |

48 (1.9) |

30 (3.1) |

29 (2.0) |

* | |||

| ≤ 1 year | 136 (0.8) |

21 (0.2) |

21 (0.9) |

32 (3.3) |

40 (5.0) |

22 (19.9) |

18 (0.2) |

18 (0.8) |

34 (3.3) |

38 (2.9) |

28 (10.3) |

|||

|

Parkinson’s disease |

No | 14405 (99.0) |

10261 (99.5) |

2302 (98.2) |

1023 (97.4) |

721 (96.5) |

98 (91.5) |

<.0001 |

9369 (99.6) |

2423 (98.5) |

997 (97.5) |

1376 (97.4) |

237 (93.3) |

<.0001 |

| Yes | 168 (1.0) | 52 (0.5) |

48 (1.8) |

30 (2.6) |

28 (3.5) |

* | 45 (0.4) |

38 (1.5) |

29 (2.5) |

40 (2.6) |

16 (6.7) |

|||

|

Rheumatoid arthritis |

No | 13356 (92.2) |

9657 (94.1) |

2078 (88.5) |

893 (84.5) |

639 (84.6) |

89 (84.6) |

<.0001 |

8854 (94.5) |

2165 (88.1) |

871 (84.2) |

1245 (87.9) |

219 (86.4) |

<.0001 |

| Yes | 1217 (7.8) |

656 (5.9) |

272 (11.5) |

160 (15.5) |

110 (15.4) |

19 (15.4) |

560 (5.5) |

296 (11.9) |

155 (15.8) |

171 (12.1) |

34 (13.6) |

|||

|

Stroke |

No | 13036 (90.7) |

9597 (93.8) |

1985 (85.4) |

820 (78.5) |

569 (77.6) |

65 (62.0) |

<.0001 |

8783 (94.0) |

2154 (88.5) |

823 (81.5) |

1124 (79.1) |

149 (60.1) |

<.0001 |

| > 1 year ago | 1257 (7.7) |

598 (5.3) |

307 (12.2) |

186 (17.3) |

139 (17.4) |

27 (23.6) |

532 (5.1) |

249 (9.5) |

162 (14.7) |

236 (16.8) |

78 (29.6) |

|||

| ≤ 1 year | 280 (1.7) |

118 (1.0) |

58 (2.5) |

47 (4.2) |

41 (5.0) |

16 (14.5) |

99 (0.9) |

58 (2.1) |

41 (3.8) |

56 (4.1) |

26 (10.3) |

|||

=Cannot display raw number nor percentage since cell size is less than 11, which are not allowed to be disclosed due to CMS’s confidentiality rules.

The primary variables of interest and all the covariates were obtained from the Cost and Use files at each autumn interview for three years. The fourth interview was not used as there was no subsequent follow-up time.

Analysis

To characterize the cohort included in this analysis, variables across the ADL and IADL stages at the first autumn interview were examined first. Time to admission to LTC was observed from the autumn interview until the next autumn interview. Thus, information regarding one beneficiary was potentially included in the model three times, and repeated measures were accounted for by using robust sandwich variance estimates.29 This approach allowed us to examine the proximal association between stage and LTC admission and made use of all available data. Fine and Gray Proportional subhazard models30 using PROC PHREG were used where sample persons were followed from baseline (each autumn Cost and Use survey) to admission to LTC. These models produce hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Death was treated as a competing risk30 so that factors associated with death would not artificially appear to be negatively associated with admission to LTC.

One model per activity limitation stage domain (i.e., ADL and IADL) was fit to examine the association with time to admission to a facility providing LTC. The models included stage plus age, sex, race, education, living arrangement, dual eligibility, proxy status, and the health conditions listed above. The ADL and IADL activity limitation stages were analyzed separately because the two domains are highly collinear and development of the stages identified them as separate constructs supported by factor analysis.23,24

The proportional hazards assumption was tested to determine if the HRs remained constant over time in the adjusted ADL and IADL models. To test this assumption, the interaction between each covariate in the final model and time to LTC admission was examined. Such interactions with p-values <0.05 would be included to the adjusted models.

All statistical analyses accounted for complex sampling including weight, clustering, stratification, and multiple observations per person. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.)31 was used for all the analyses. Specifically, we used PROC SURVEYFREQ to obtain results for table 1 and the sampling cluster variable was specified in the CLUSTER option. For the models, we treated sampling strata and clusters as the strata in the stratified proportional subhazard model. In other words, each cluster in a stratum can have a different baseline subhazard. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by specifying sampling clusters in the ID option to account for the correlation (the other level of correlation is the beneficiary as one beneficiary can contribute up to 3 observations) in PROC PHREG. P-values were two-sided, with statistical significance defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

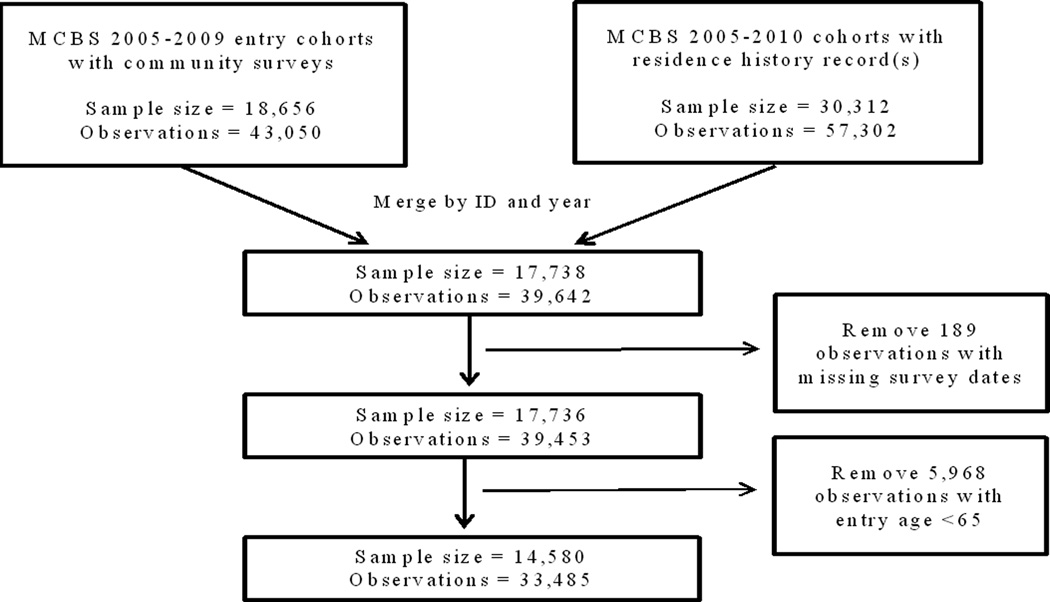

There were a total of 14,580 beneficiaries included in the sample. Some beneficiaries were missing information on covariates that were included in the models and were therefore excluded from the analyses (Figure 1). Thus, 14,573 beneficiaries were included in the ADL stages analyses and 14,570 beneficiaries were included in the IADL analyses. The number of deaths during the study period (n=760) compared to the number of admissions to LTC confirmed treatment of death as competing risk in the model was appropriate.

Figure 1. Flow Chart for the Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of Cohort.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics by ADL and IADL stage. Older beneficiaries were more likely to be at higher activity limitation stages. Those at higher activity limitation stages generally had a higher number of comorbidities.

The weighted annual rate of admission to LTC was 1.1% (459 admissions out of 32,485 possible observations of 14,580 beneficiaries). The proportional hazards assumption was not violated for any variable in either the ADL or IADL model.

The associations between stage above 0 and admission to LTC were strong and statistically significant. The increase in hazard ratios with stage was monotonic in the IADL model and monotonic except for stage III in the ADL model (Figure 2). More specifically, compared to ADL stage 0, the hazard ratios and 95% CIs were 2.0 (1.5–2.7), 3.9 (2.9–5.4), 3.6 (2.5–5.3), and 4.7 (2.5–9.0) for ADL stage I, ADL stage II, ADL stage III, and ADL stage IV, respectively. Compared to IADL stage 0, the hazard ratios and 95% CIs for IADL stages I–IV were 2.0 (1.4–2.7), 3.7 (2.6–5.4), 4.6 (3.3–6.5), and 7.6 (4.6–12.3), respectively.

Figure 2. Association between Activity of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL) Stages and Admission to Facilities Providing Long-term Care.

Key for Figure 2: reference = stage 0; Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are from the fully-adjusted models (ADL or IADL stage in separate models, age, sex, race, education, living arrangement, dual eligibility, proxy status, and health conditions (Alzheimer’s disease, amputation, angina or coronary artery diseases, arthritis other than rheumatoid, broken hip, cancer other than skin, congestive heart failure, depression, diabetes type 1, 2, or other, emphysema/asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hardening of the arteries, heart rhythm disease, heart valve disease, hypertension, incontinence/catheterization, mental or psychiatric conditions, mental retardation, myocardial infarction, osteoporosis, paralysis, Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and stroke).

The y-axis is the hazard ratios and the x-axis is the ADL or IADL stages.

The results from the sensitivity analysis were similar to the main results in that all the results remained statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that activity limitation stages are strongly associated with admission within one year to facilities providing long-term care, adjusting for well-known risk factors for admission to LTC including dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.4,9,32–35 For the ADL stages, the hazard ratios increased monotonically, except at stage III. This was not unexpected, since by design stage III is non-fitting, i.e., capturing non-hierarchical patterns of activity limitation that do not meet the definitions for assignment to stages II or IV. The hazard ratio doubled from ADL stage 0 to ADL stage I, and then almost doubled again from ADL stage I to ADL stage II. Moreover, the relationship with IADL stages was monotonic. The hazard increased by more than 1.5-fold between IADL stage III and IADL stage IV.

Admission to LTC is associated with factors such as demographic characteristics, health status, and lack of social support.36 A myriad of complex mechanisms may underlie these well-known relationships, including disease severity, presence of a disabling condition, living environment and circumstances, insurance coverage, and financial status. Efforts to maintain or improve function have received less attention than deserved. Similar to TNM staging in which new diagnostic imaging procedures have been better at predicting survival rates among patients with lung cancer,37 activity limitation staging is an emerging approach intended to more explicitly capture the activities people are still able to do without difficulty in sharp contrast to counts of limitations which only provide information in the number of activities that are limited. In this study, prior findings have been extended by evaluating the relationship between activity limitation stages and admission to LTC. Knowledge of the strong association between specific patterns of activity limitation and admission to LTC could help stimulate the development of “personalized” therapeutic or care strategies or programs to ameliorate the effects of disabilities in older adults, potentially improving the performance of those activities most critical to averting admission to LTC. This, in turn, could enable older adults to “age in place” in the community for extended periods of time, leading to improvements in quality of life.

The results were consistent with our a priori hypotheses. One hypothesis was that persons with any ADL limitation (stage I or higher) would be more likely to be admitted to LTC compared to those without ADL limitations. Other researchers have shown that disability in bathing was associated with an increased risk of admission to LTC,38 which corresponds to ADL stage II. This study found an increased risk beginning at ADL stage I, with some additional risk at stage II. Persons at ADL stage I may have difficulty walking and/or getting in and out of a bed or chair, while those at ADL stage II in addition may have difficulties dressing and/or bathing. For a person at stage I, the activities of walking and/or getting in and out of a bed or chair have become difficult. Difficulties and the lack of someone to help at home with these tasks could trigger admission to LTC. Unlike the approach used by Gill and colleagues,38 the activity limitation stages used in this study looked at difficulty experienced in doing the activity and not at the receipt of help from a second person. However, the significant association between stage I and LTC suggests that difficulty with these tasks may be strongly correlated with need for help. This could explain why stages based on self- or proxy-reported difficulty are associated with admission to LTC, beginning at stage I.

IADLs may be affected more by living arrangement than ADLs are. No or low levels of social support (i.e., being single or only living with children) has been noted as a risk factor for admission to LTC.4 The relationships among disability, extent of help needed, caregiver availability to meet that need, and changes in degree of caregiver burden are all likely to be important in explaining risk of admission to LTC. Moreover, the types and patterns of activity limitation revealed by the IADL stages can be used to identify targets for interventions aimed at mitigating specific factors that increase the risk of admission to LTC in subsets of the Medicare population. For example, the telephone activity in the IADL domain might be more important than any of the ADL items since the person cannot call for help. Although electronic sensors on medical alert systems may be worn by patients to automatically call caregivers or 911 when assistance is needed in emergency situations, those at greatest risk for admission to LTC may be patients who lose the ability to use the telephone to call for help in routine and semi-urgent (but non-emergency) situations, and therefore can no longer be left alone during part of the day or night. Persons who experience difficulty using the telephone are, by definition, assigned to IADL stage III. Among elders who progress to IADL stage III, those with only part-time on-site caregivers may represent another sub-population at higher risk for admission to LTC that may benefit from a targeted intervention. In comparison, those at IADL stage II may have difficulty preparing meals, doing light housework, shopping, and/or doing heavy housework. These items may not be applicable to the beneficiary himself as someone else may do the activity because of non-health reasons,39 but people at these two distinct stages require different care needs and support systems. In particular, stage III of the activity limitation staging system allows categorization of those tasks that are not part of the normal hierarchy of difficulty.23,24 Policy makers or administrators can recognize specific areas where beneficiaries may need help. Those categorized at stage III will need a broader range of services since stage III is atypical. Traditional instruments that measure disability such as counts of ADL or IADL limitations misses the opportunity to specify both the severity and type of limitation the beneficiary experiences.

This study has limitations that deserve comment. Since survey data was used, there is the possibility of recall bias by the study participant. In addition, the survey data were obtained through self-or proxy responses. The sample person may not have answered the same way that the proxy answered for the beneficiary since there may be differences in perception of difficulty in performing various ADLs and IADLs,23 however, proxy responses were included and controlled for because it was shown that bias could be introduced when proxy responses are excluded.40 There may be unobserved variables (i.e., prior falls) that are associated with admission to LTC. Cognition as a covariate was not included in the models since it was unavailable. We were unable to account for the complicated issues surrounding caregiver availability in the analysis, such as the caregiver’s availability or willingness to meet the beneficiary’s need or the change in degree of caregiver burden’s ability to help the beneficiary. Although in our adjusted models, beneficiaries who were Medicare and Medicaid dual enrollee had more than four times the hazards of LTC admission compared to beneficiaries with Medicare alone, we were not able to adjust for differences by state or for admissions (or lack thereof) to LTC due to Medicare or Medicaid eligibility requirements. It is also worth mentioning that the MCBS uses a broad definition of LTC and does not ask sample persons to distinguish between short- and long-stays in facilities. Similarly, many of the listed LTC facilities are quite different in nature. Furthermore, there may be an issue with selection bias which may affect the outcome. Patients may be admitted to other settings before being admitted to LTC. Future research will need to look at a parsimonious set of variables that predict admission to LTC among Medicare beneficiaries. Knowledge of these factors will help develop future policies to delay or prevent admission to LTC. Activity limitation stages might serve as a useful tool to identify personalized environmental supports or rehabilitation strategies to prevent functional decline. Future work should aim to identify effective interventions in population subsets with patterns of activity limitation that place them at greatest risk for admission to LTC.

Activity limitation stages are powerful predictors of admission to facilities providing LTC. Activity limitation staging, by grouping people across distinct domains of disability, offers an innovative approach to planning for the care needs of the aging population, and represents a potentially useful tool for changing and tracking adverse outcomes. Knowing which specific limitations the person has is important for admission to facilities providing LTC by being able to adequately target care and help in anticipating future health care planning. Our results underscore the importance of early interventions to support community-dwelling people at ADL or IADL stage I (mild limitations). If both known limitations are captured among people earlier and unknown limitations are recognized earlier, strategies may be developed for maintaining their community-dwelling status at milder activity limitation stages longer. A further understanding of the associations of activity limitation stages with adverse outcomes is necessary for establishing approaches to track the potential benefits of interventions at the population-level to improve independent living for people with disabilities. The greater specificity of disability profiles depicted in activity limitation stages can be used to enhance communication across lay and professional audiences, better projecting supportive care needs and better targeting initiatives to sub-groups of older adults, with the goal of delaying or preventing admission to LTC and preserving quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AG040105) and a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute PCORI Project Program Award AD-12-11-4567. Neither the National Institutes of Health nor the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) (which provided the data) played a role in the design or conduct of the study, in the analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

We would like to thank Dr. Margaret G. Stineman for the foundation of the activity limitation staging systems.

Footnotes

Disclosures: There are no personal conflicts of interest of any of the authors, and no authors reported disclosures beyond the funding source.

This material has not been previously presented at a meeting.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health & Human Services. What is Long-Term Care? [Accessed May 17, 2016];2016 http://longtermcare.gov/the-basics/what-is-long-term-care/

- 2.NIH Senior Health. Long-Term Care. [Accessed May 17, 2016];2015 http://nihseniorhealth.gov/longtermcare/whatislongtermcare/01.html.

- 3.Ahmed A, Allman RM, JF D. Predictors of nursing home admission for older adults hospitalized with heart failure. Arch Gerontol Geriatrc. 2003;36:117–126. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharucha AJ, Pandav R, Shen C, Dodge HH, Ganguli M. Predictors of nursing facility admission: a 12-year epidemiological study in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(3):434–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley DJ, Ostfeld AM, Branch LG, Wallace RB, McGloin J, Cornoni-Huntley JC. The risk of nursing home admission in three communities. J Aging Health. 1992;4(2):155–173. doi: 10.1177/089826439200400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu K, Coughlin T, McBride T. Predicting nursing-home admission and length of stay. A duration analysis. Med Care. 1991;29(2):125–141. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai Q, Salmon JW, Rodgers ME. Factors associated with long-stay nursing home admissions among the U.S. elderly population: comparison of logistic regression and the Cox proportional hazards model with policy implications for social work. Soc Work Health Care. 2009;48(2):154–168. doi: 10.1080/00981380802580588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman JF. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47(2):191–198. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu K, McBride T, Coughlin T. Risk of entering nursing homes for long versus short stays. Med Care. 1994;32(4):315–327. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temkin-Greener H, Meiners MR. Transitions in long-term care. Gerontologist. 1995;35(2):196–206. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(18):1279–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710303371806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valiyeva E, Russell LB, Miller JE, Safford MM. Lifestyle-related risk factors and risk of future nursing home admission. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):985–990. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fong JH, Mitchell OS, Koh BS. Disaggregating activities of daily living limitations for predicting nursing home admission. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):560–578. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jette AM, Branch LG, Sleeper LA, Feldman H, Sullivan LM. High-risk profiles for nursing home admission. Gerontologist. 1992;32(5):634–640. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennessy S, Kurichi JE, Pan Q, et al. Disability Stage is an Independent Risk Factor for Mortality in Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 65 Years and Older. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2015;7(12):1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stineman MG, Xie D, Pan Q, et al. All-cause 1-, 5-, and 10-year mortality in elderly people according to activities of daily living stage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(3):485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Z, Xie D, Kurichi JE, Streim J, Zhang G, Stineman MG. Mortality predictive indexes for the community-dwelling elderly US population. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):901–910. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2027-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown J, Kurichi JE, Xie D, Pan Q, Stineman MG. Instrumental activities of daily living staging as a possible clinical tool for falls risk assessment in physical medicine and rehabilitation. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2014;6(4):316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.10.007. quiz 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henry-Sanchez JT, Kurichi JE, Xie D, Pan Q, Stineman MG. Do elderly people at more severe activity of daily living limitation stages fall more? Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(7):601–610. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31825596af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogner HR, de Vries McClintock HF, Hennessy S, et al. Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality of Care Among Older Adults According to Activity Limitation Stages. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(10):1810–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559–565. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurichi JE, Streim JE, Bogner HR, Xie D, Kwong PL, Hennessy S. Comparison of predictive value of activity limitation staging systems based on dichotomous versus trichotomous responses in the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(1):64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stineman MG, Streim JE, Pan Q, Kurichi JE, Schussler-Fiorenza Rose SM, Xie D. Activity Limitation Stages empirically derived for Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental ADL in the U.S. Adult community-dwelling Medicare population. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2014;6(11):976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.05.001. quiz 987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fainsinger RL, Nekolaichuk CL. A "TNM" classification system for cancer pain: the Edmonton Classification System for Cancer Pain (ECS-CP) Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(6):547–555. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health and Health Care of the Medicare Population. Technical Documentation for the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey- Appendix A page 2. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kautter J, Khatutsky G, Pope GC, Chromy JR, Adler GS. Impact of nonresponse on Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey estimates. Health Care Financ Rev. 2006;27(4):71–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Health & Human Services. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) [Accessed March 26, 2013];2010 http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MCBS/

- 29.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The Robust Inference for the Proportional Hazards Model. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1989;84:1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lo A, Ghu A. Variance Estimation and the Components of Variance for the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Sample. American Statistical Association Section on Survey Research Methods. 2005:3333–3341. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banaszak-Holl J, Fendrick AM, Foster NL, et al. Predicting nursing home admission: estimates from a 7-year follow-up of a nationally representative sample of older Americans. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(2):83–89. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000126619.80941.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauer EJ. Transitions from home to nursing home in a capitated long-term care program: the role of individual support systems. Health Serv Res. 1996;31(3):309–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heyman A, Peterson B, Fillenbaum G, Pieper C. Predictors of time to institutionalization of patients with Alzheimer's disease: the CERAD experience, part XVII. Neurology. 1997;48(5):1304–1309. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott WK, Edwards KB, Davis DR, Cornman CB, Macera CA. Risk of institutionalization among community long-term care clients with dementia. Gerontologist. 1997;37(1):46–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Brahler E, Riedel-Heller SG. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39(1):31–38. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(25):1604–1608. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506203122504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gill TM, Allore HG, Han L. Bathing disability and the risk of long-term admission to a nursing home. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(8):821–825. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stineman MG, Xie D, Pan Q, et al. Understanding non-performance reports for instrumental activity of daily living items in population analyses: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stineman MG, Ross RN, Maislin G. Functional status measures for integrating medical and social care. Int J Integr Care. 2005;5:e07. doi: 10.5334/ijic.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.