Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional survey with longitudinal follow-up

Objectives

To test the hypothesis that pain which is localised to the low back differs epidemiologically from that which occurs simultaneously or close in time to pain at other anatomical sites

Summary of Background Data

Low back pain (LBP) often occurs in combination with other regional pain, with which it shares similar psychological and psychosocial risk factors. However, few previous epidemiological studies of LBP have distinguished pain that is confined to the low back from that which occurs as part of a wider distribution of pain.

Methods

We analysed data from CUPID, a cohort study that used baseline and follow-up questionnaires to collect information about musculoskeletal pain, associated disability and potential risk factors, in 47 occupational groups (office workers, nurses and others) from 18 countries.

Results

Among 12,197 subjects at baseline, 609 (4.9%) reported localised LBP in the past month, and 3,820 (31.3%) non-localised LBP. Non-localised LBP was more frequently associated with sciatica in the past month (48.1% vs. 30.0% of cases), occurred on more days in the past month and past year, was more often disabling for everyday activities (64.1% vs. 47.3% of cases), and had more frequently led to medical consultation and sickness absence from work. It was also more often persistent when participants were followed up after a mean of 14 months (65.6% vs. 54.1% of cases). In adjusted Poisson regression analyses, non-localised LBP was differentially associated with risk factors, particularly female sex, older age and somatising tendency. There were also marked differences in the relative prevalence of localised and non-localised LBP by occupational group.

Conclusions

Future epidemiological studies should distinguish where possible between pain that is limited to the low back and LBP which occurs in association with pain at other anatomical locations.

Keywords: Low back pain, diagnostic classification, epidemiology, disability, medical consultation, sickness absence, sciatica, risk factors, somatising, occupation, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain (LBP) is a major cause of disability among people of working age [1], but investigation of its causes has been hindered by challenges in case definition. In most people with LBP, there is no clearly demonstrable underlying spinal pathology, and even where the pain occurs in association with structural abnormalities such as disc herniation or nerve root compression, only a minority of cases are attributable to the observed pathology [2]. In the absence of more objective diagnostic criteria, most epidemiological studies have defined cases according to report of symptoms and/or accompanying disability, and this approach has given useful insights. For example, we know that LBP is associated with heavy lifting and other physical activities which subject the spine to mechanical stresses [3], although disappointingly, ergonomic interventions in the workplace to reduce such exposures have failed to prevent back problems [4]. Associations have also been found with psychological characteristics such as low mood [5–7], tendency to worry about common somatic symptoms (somatising tendency) [5,7], adverse health beliefs about musculoskeletal pain [6], and (to a lesser extent) psychosocial aspects of work [8].

The same psychological and psychosocial risk factors have been linked also with other regional musculoskeletal pain, for example in the upper limb [8,9] and knee [10]; and somatising tendency has shown particularly strong associations with multi-site pain [11]. Moreover, LBP frequently occurs in combination with pain at other anatomical sites, either simultaneously or close in time [12–15]. This raises the possibility that the observed associations of LBP with psychological and psychosocial risk factors might reflect effects on musculoskeletal pain more generally, and that pain which is limited only to the low back is epidemiologically distinct from that which occurs as part of a wider distribution of pain. If this were the case, studies that failed to distinguish localised from non-localised LBP might miss associations with preventable causes, or incorrectly assess the impacts of treatment.

To test the hypothesis that localised and non-localised LBP are epidemiologically distinct, we analysed data from CUPID (Cultural and Psychosocial Influences on Disability), a large, multinational cohort study of musculoskeletal pain and associated disability in selected occupational groups [16], looking for differences in severity, associations with risk factors, and prognosis of LBP, according to whether or not pain was limited to the low back.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study sample for CUPID comprised men and women from 47 occupational groups (mainly nurses, office staff and workers carrying out repetitive manual tasks with their hands or arms) in 18 countries. Each of the 12,426 participants (overall response rate 70%) completed a baseline questionnaire, either by self-administration or at interview. The questionnaire was originally drafted in English and then translated into local languages as necessary, accuracy being checked by independent back-translation. Among other things, it asked about demographic characteristics, smoking habits, whether an average working day entailed lifting weights ≥25 kg, various psychosocial aspects of work, somatising tendency, mental health, beliefs about back pain, and experience of musculoskeletal pain during the past 12 months.

Somatising tendency was ascertained through questions taken from the Brief Symptom Inventory [17], and classified according to how many of five common somatic symptoms (faintness or dizziness, pains in the heart or chest, nausea or upset stomach, trouble getting breath and hot or cold spells) had caused at least moderate distress during the past week. Mental health was assessed through the relevant section of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire [18], and scores were graded to three levels (good, intermediate or poor) representing approximate thirds of the distribution across the study sample. Participants were classed as having adverse beliefs about the work-relatedness of back pain if they completely agreed that such pain is commonly caused by work; about its relationship to physical activity if they completely agreed that for someone with back pain, physical activity should be avoided as it might cause harm, and that rest is needed to get better; and about its prognosis if they completely agreed that neglecting such problems can cause serious harm, and completely disagreed that such problems usually get better within three months.

The questions about musculoskeletal pain used diagrams to define 10 anatomical regions of interest (low back; neck; and right and left shoulder, elbow, wrist/hand and knee). Participants were asked whether during the past 12 months, they had experienced pain lasting for a day or longer at these sites, and those who reported LBP were also asked whether the pain had occurred in the past month, whether it had spread down the leg to below the knee (sciatica), how long in total it had been present during the past month and past 12 months, whether during the past month it had made it difficult or impossible to cut toe nails, get dressed or do normal jobs around the house (disabling pain), whether it had led to medical consultation during the past 12 months, the total duration of any resultant sickness absence from work during the past 12 months, and whether the most recent episode had started suddenly while at work, suddenly while not at work or gradually (an episode of pain was defined as occurring after a period of at least one month without the symptom).

After an interval of approximately 14 months, participants from 45 of the occupational groups were asked to complete a short follow-up questionnaire, which again asked about LBP in the past month.

Further details of the methods of data collection, specification of variables, and characteristics of the study sample have been reported elsewhere [16]. Approval for the study was provided by the relevant research ethics committees in each participating country [16].

Statistical analysis was carried out with Stata software (Stata Corp LP 2012, Stata Statistical Software: Release 12.1, College Station TX, USA). From the baseline questions about pain, we distinguished participants who reported: LBP in the past month but no pain at any other site during the past 12 months (“localised LBP”); LBP in the past month with pain at one or more other sites during the past 12 months (“non-localised LBP”); and no LBP at any time during the past 12 months. We used simple descriptive statistics to compare the features of localised and non-localised LBP, including the prevalence of continuing LBP (i.e. present in the past month) at follow-up. Associations with risk factors were explored by Poisson regression, and summarised by prevalence rate ratios (PRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on robust standard errors. To account for possible clustering by occupational group, we fitted random-intercept models. A scatter plot was used to explore the correlation of localised and non-localised LBP across the 47 occupational groups after adjustment for other risk factors. To derive adjusted prevalence rates, we took no LBP in the past 12 months as a comparator, and first estimated PRRs for the two pain outcomes in each occupational group relative to a reference (office workers in the UK), using Poisson regression models that included the other risk factors. We then calculated the “adjusted numbers” of participants in each occupational group with the two pain outcomes that would give crude PRRs equal to those estimated from the regression model. Finally, we used these adjusted numbers to calculate adjusted prevalence rates.

RESULTS

From the total of 12,426 participants who completed the baseline questionnaire, we excluded 149 because of missing information about LBP in the past month (122), 12 months (2) or both (25), and a further 80 who did not provide full responses regarding pain at other anatomical sites in the past 12 months. Among the remaining 12,197 subjects (35% men), 609 (5.0%) reported localised LBP in the past month, and 3,820 (31.3%) non-localised LBP.

Table 1 compares the characteristics of the pain in these two groups of people with low back symptoms. Non-localised LBP was more frequently associated with sciatica (48.1% vs. 30.0% in past month), occurred on more days in the past month and past year, was more often disabling for everyday activities (64.1% vs. 47.3%), and had more frequently led to medical consultation and sickness absence from work during the past year. However, there was no difference between the categories of LBP in the prevalence of sudden as opposed to gradual onset.

Table 1.

Characteristics of localised and non-localised low back pain

| Characteristic | Localised low back pain (n = 609) | Non-localised low back pain (n = 3,820) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | (95%CI) | N | % | (95%CI) | |

| Sciatica in past month | 183 | 30.0 | (26.4,33.9) | 1,836 | 48.1 | (46.5,49.7) |

| Sciatica in past 12 months | 233 | 38.3 | (34.4,42.3) | 2,238 | 58.6 | (57.0,60.2) |

| Total duration in past month | ||||||

| 1–6 days | 369 | 60.6 | (56.6,64.5) | 2,067 | 54.1 | (52.5,55.7) |

| 1–2 weeks | 123 | 20.2 | (17.1,23.6) | 783 | 20.5 | (19.2,21.8) |

| >2 weeks | 112 | 18.4 | (15.4,21.7) | 947 | 24.8 | (23.4,26.2) |

| Not known | 5 | 0.8 | 23 | 0.6 | ||

| Total duration in past 12 months | ||||||

| 1–6 days | 180 | 29.6 | (26.0,33.4) | 740 | 19.4 | (18.1,20.7) |

| 1–4 weeks | 263 | 43.2 | (39.2,47.2) | 1,661 | 43.5 | (41.9,45.1) |

| 1–12 months | 162 | 26.6 | (23.1,30.3) | 1,403 | 36.7 | (35.2,38.3) |

| Not known | 4 | 0.7 | 16 | 0.4 | ||

| Disabling in past month | 288 | 47.3 | (43.3,51.3) | 2,447 | 64.1 | (62.5,65.6) |

| Led to medical consultation in past 12 months | 255 | 41.9 | (37.9,45.9) | 1,974 | 51.7 | (50.1,53.3) |

| Attributed sickness absence in past 12 months (days) | ||||||

| 0 | 475 | 78.0 | (74.4,81.2) | 2,707 | 70.9 | (69.4,72.3) |

| 1–5 | 83 | 13.6 | (11.0,16.6) | 674 | 17.6 | (16.4,18.9) |

| 6–30 | 29 | 4.8 | (3.2,6.8) | 238 | 6.2 | (5.5,7.0) |

| >30 | 10 | 1.6 | (0.8,3.0) | 85 | 2.2 | (1.8,2.7) |

| Not known | 12 | 2.0 | 116 | 3.0 | ||

| Onset of most recent episode | ||||||

| Sudden while at work | 167 | 27.4 | (23.9,31.2) | 1,176 | 30.8 | (29.3,32.3) |

| Sudden not while at work | 110 | 18.1 | (15.1,21.4) | 530 | 13.9 | (12.8,15.0) |

| Gradual | 318 | 52.2 | (48.2,56.2) | 2,015 | 52.7 | (51.2,54.3) |

| Not known | 14 | 2.3 | 99 | 2.6 | ||

Table 2 summarises the associations of localised and non-localised LBP with various risk factors. The comparator in this analysis was no LBP at any time in the past 12 months (n = 5,501). Non-localised LBP was significantly more common in women than men, and at older ages, whereas the prevalence of localised LBP was significantly higher in men, and varied little with age. Somatising tendency was much more strongly related to non-localised LBP (PRR 1.7, 95%CI 1.5–1.8 for report of distress from two or more somatic symptoms) than localised LBP (PRR 1.1, 95%CI 0.9–1.4). Associations with non-localised pain were stronger also for poor mental health and report of time pressure at work. Direct comparison of participants with localised and non-localised LBP in a single Poisson regression model (effectively taking those with non-localised LBP as cases and those with localised LBP as controls) indicated that the differences in associations with sex, age and somatising tendency were all highly significant statistically (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Associations of localised and non-localised low back pain with personal and occupational risk factors

| Risk factor | No low back pain in past 12 months | Localised low back pain | Non-localised low back pain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | PRRa | (95%CI) | N | PRRa | (95%CI) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 2,265 | 292 | 1 | 943 | 1 | ||

| Female | 3,236 | 317 | 0.8 | (0.6,0.9) | 2,877 | ***1.2 | (1.1,1.3) |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 20–29 | 1,502 | 175 | 1 | 783 | 1 | ||

| 30–39 | 1,737 | 208 | 1.0 | (0.8,1.2) | 1,189 | **1.1 | (1.1,1.2) |

| 40–49 | 1,446 | 147 | 0.9 | (0.7,1.1) | 1,203 | ***1.2 | (1.1,1.4) |

| 50–59 | 816 | 79 | 0.9 | (0.7,1.1) | 645 | ***1.2 | (1.1,1.4) |

| Smoking | |||||||

| Never smoked | 3,631 | 339 | 1 | 2,349 | 1 | ||

| Ex-smoker | 727 | 91 | 1.3 | (1.0,1.7) | 579 | 1.1 | (1.1,1.2) |

| Current smoker | 1,124 | 176 | 1.3 | (1.0,1.7) | 885 | 1.1 | (1.1,1.3) |

| Not known | 19 | 3 | 7 | ||||

| Activity in average working day | |||||||

| Lifting weights ≥25 kg | 1,684 | 266 | 1.4 | (1.2,1.7) | 1,599 | 1.2 | (1.1,1.3) |

| Psychosocial aspects of work | |||||||

| Work for >50 hours per week | 1,394 | 176 | 1.0 | (0.8,1.3) | 601 | †1.0 | (0.9,1.1) |

| Time pressure at work | 3,948 | 456 | 1.0 | (0.8,1.2) | 3,046 | *1.2 | (1.1,1.3) |

| Incentives at work | 1,605 | 168 | 0.9 | (0.7,1.1) | 1,054 | 1.0 | (0.9,1.1) |

| Lack of support at work | 1,104 | 126 | 1.0 | (0.8,1.3) | 1,190 | **1.1 | (1.0,1.2) |

| Job dissatisfaction | 1,087 | 128 | 0.9 | (0.8,1.1) | 817 | 1.0 | (0.9,1.2) |

| Lack of job control | 1,136 | 134 | 1.1 | (0.9,1.3) | 864 | 1.0 | (1.0,1.1) |

| Job insecurity | 1,652 | 220 | 1.1 | (1.0,1.3) | 1,277 | 1.1 | (1.0,1.2) |

| Number of distressing somatic symptoms in past week | |||||||

| 0 | 3,871 | 406 | 1 | 1,631 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 983 | 127 | 1.2 | (1.0,1.5) | 943 | ***1.4 | (1.3,1.5) |

| 2+ | 596 | 70 | 1.1 | (0.9,1.4) | 1,200 | ***1.7 | (1.5,1.8) |

| Missing | 51 | 6 | 46 | ||||

| Mental health | |||||||

| Good | 2,417 | 225 | 1 | 1,137 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate | 1,628 | 181 | 1.1 | (0.9,1.3) | 1,157 | 1.2 | (1.1,1.3) |

| Poor | 1,418 | 198 | 1.2 | (1.0,1.5) | 1,504 | **1.4 | (1.3,1.5) |

| Missing | 38 | 5 | 22 | ||||

| Adverse beliefs about back pain | |||||||

| Work-relatedness | 1,472 | 215 | 1.3 | (1.1,1.5) | 1,617 | *1.3 | (1.2,1.3) |

| Physical activity | 999 | 119 | 0.9 | (0.7,1.1) | 669 | 0.9 | (0.9,1.0) |

| Prognosis | 598 | 86 | 1.2 | (1.0,1.4) | 709 | **1.2 | (1.1,1.3) |

Prevalence rate ratios relative to no low back pain in past 12 months derived from a single Poisson regression model for each pain outcome, with random intercept modelling to allow for clustering by occupational group

Risk significantly higher for non-localised when compared directly with localised low back pain (p<0.05)

Risk significantly higher for non-localised when compared directly with localised low back pain (p<0.01)

Risk significantly higher for non-localised when compared directly with localised low back pain (p<0.001)

Risk significantly lower for non-localised when compared directly with localised low back pain (p<0.01)

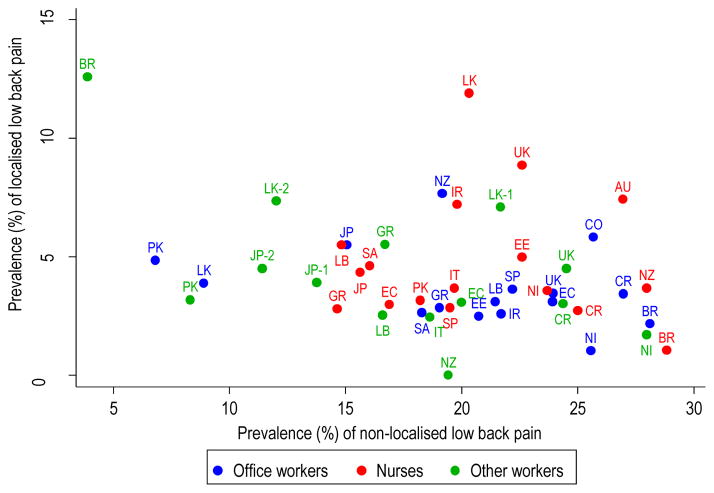

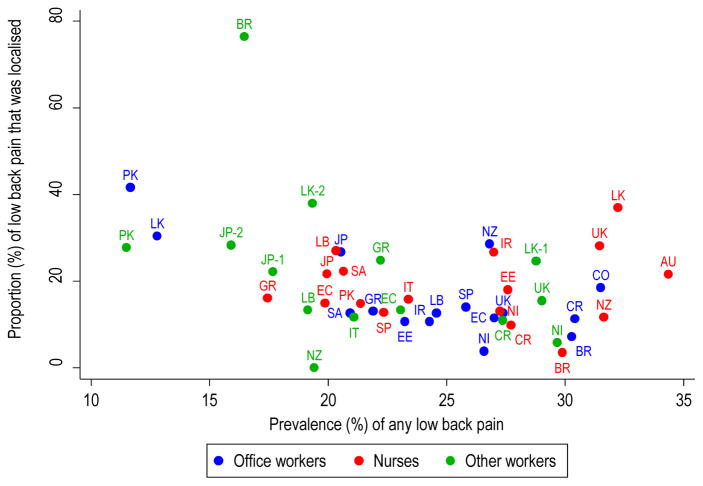

Figure 1 shows the one-month prevalence of localised and non-localised LBP by occupational group, after adjustment for all of the risk factors in Table 2. Rates of localised LBP ranged from zero among postal workers in New Zealand and 1.0% in office workers in Nicaragua to 11.9% in Sri Lankan nurses, and 12.6% in Brazilian sugar cane cutters. For non-localised LBP, the absolute variation in prevalence was even greater – from 3.9% in Brazilian sugar cane cutters and 6.8% among office workers in Pakistan to 28.1% in Brazilian office workers and 28.8% in Brazilian nurses. However there was no clear relationship between the two categories of LBP. Thus, as illustrated in Figure 2, the proportion of all back pain cases that were localised varied substantially, but did not consistently rise or fall as the overall prevalence of LBP increased (Spearman correlation coefficient = −0.37).

Figure 1. One-month prevalence of localised and non-localised low back pain by occupational group.

Prevalence rates are adjusted for all of the risk factors in Table 2

Key to countries: AU Australia; BR Brazil; CO Colombia; CR Costa Rica; EC Ecuador; EE Estonia; GR Greece; IR Iran; IT Italy; JP Japan; LB Lebanon; LK Sri Lanka; NI Nicaragua; NZ New Zealand; PK Pakistan; SA South Africa; SP Spain; UK United Kingdom

Figure 2. Proportion of low back pain that was localised according to overall prevalence of low back pain in each occupational group.

Prevalence rates are adjusted for all of the risk factors in Table 2

Key to countries: AU Australia; BR Brazil; CO Colombia; CR Costa Rica; EC Ecuador; EE Estonia; GR Greece; IR Iran; IT Italy; JP Japan; LB Lebanon; LK Sri Lanka; NI Nicaragua; NZ New Zealand; PK Pakistan; SA South Africa; SP Spain; UK United Kingdom

Among the 11,764 participants from whom follow-up data were sought, 9,188 (78%) provided satisfactory information about LBP at a mean of 14 months (range 3–35 months, 84% within 11–19 months) after baseline. Table 3 shows the prevalence of continuing LBP at follow-up according to the features of pain at baseline. Overall, persistence of pain was more frequent when initially it was non-localised (65.6%) than when it was localised (54.1%). Moreover, both categories of pain were more likely to be persistent if there was associated sciatica at baseline.

Table 3.

One-month prevalence of low back pain at follow-up according to localisation of low back pain at baseline

| Category of low back pain at baseline | Number of cases at baseline | Low back pain in past month at follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | Prevalence % | (95%CI) | ||

| Localised with no sciatica in past 12 months | 282 | 144 | 51.1 | (45.1,57.0) |

| Localised with sciatica in past 12 months | 158 | 94 | 59.5 | (51.4,67.1) |

| All localised low back pain | 440 | 238 | 54.1 | (49.3,58.8) |

| Non-localised with no sciatica in past 12 months | 1,199 | 718 | 59.9 | (57.0,62.6) |

| Non-localised with sciatica in past 12 months | 1,695 | 1,181 | 69.7 | (67.4,71.8) |

| All non-localised low back pain | 2,894 | 1,899 | 65.6 | (63.8,67.4) |

Analysis was restricted to the 9,188 cases with satisfactory information about low back pain at follow-up

DISCUSSION

In this large international study, we found that most LBP (86%) was non-localised. In comparison with localised LBP, non-localised LBP tended to be more troublesome, disabling and persistent, and showed distinctive associations with risk factors. In addition, the two categories of LBP differed markedly in their relative prevalence across the 47 occupational groups that were studied.

Apart from occupational group, all of the information that was analysed came from questionnaires. Pain, somatising tendency, mental health and health beliefs are all best assessed through self-report. However, it is possible that reliance on participants’ recall led to inaccuracies in other variables such as smoking habits and exposure to heavy lifting at work. If so, the impact on risk estimates will have depended on whether errors differed systematically according to report of pain. If they were non-differential with respect to pain, then any resultant bias will have been towards the null. On the other hand, if they varied by pain status (e.g. if participants with LBP tended to report heavy lifting more completely than those who were pain-free), then risk estimates could have been spuriously exaggerated. However, even if such biases occurred, it seems unlikely that they would have differed importantly according to whether or not LBP was localised.

A particular methodological challenge in the CUPID study was the possibility that despite our efforts to minimise errors in translation of the questionnaires, terms for pain might be understood differently in different cultures. However, misunderstandings are less likely to have occurred in determining the anatomical location of symptoms, which was assisted by the use of diagrams. Thus, while some of the differences between occupational groups in the overall prevalence of LBP may have been a linguistic artefact, variations in the proportion of LBP that was localised are likely to be more reliable.

It seems unlikely that the differences which we found between localised and non-localised LBP could be explained by selective participation in the study. Eligibility for inclusion depended only on participants’ employment in designated jobs and being in the specified age range, and response rates were relatively high both at baseline and at follow-up. Moreover, we can think of no reason why responders should differ from non-responders differentially in relation to associations with non-localised as compared with localised LBP.

In comparison with localised LBP, non-localised LBP was more persistent and more often a cause of disability, sickness absence from work and medical consultation. This accords with the observation in a Dutch study that among industrial workers with LBP, those whose pain was disabling or had lasted for longer than three months were more likely to have musculoskeletal co-morbidity [14], although in that investigation rates of sickness absence and medical care-seeking were only marginally higher in subjects whose LBP was accompanied by pain in the upper extremity. Also, in a community-based Norwegian investigation, functional ability was better among participants with localised LBP than in those who reported LBP as part of widespread pain [12]. These differences may occur because people who report pain at multiple sites have a generally lower threshold for awareness and intolerance of symptoms.

Before performing our analysis, we speculated that sudden onset and associated sciatica might be indications that LBP arises from acute injury or other localised spinal pathology, and therefore would be more common among people with localised LBP. However, we found no evidence for such a relationship. On the contrary, sciatica was more prevalent among participants with non-localised LBP than in those whose LBP was localised.

Previous analysis of the CUPID dataset has indicated that multi-site musculoskeletal pain is more common in women than men, and at older ages [15]. It is therefore unsurprising that non-localised LBP showed similar associations. In marked contrast, however, localised LBP was more frequent among men than women, and tended to have higher prevalence at younger ages. This is consistent with findings from a community-based survey in Norway [12].

After adjustment for sex and age, both localised and non-localised LBP were associated with smoking, heavy lifting, somatising tendency, poor mental health, adverse beliefs about occupational causation and the prognosis of LBP, and less clearly with some psychosocial aspects of work (Table 2). Because the analysis was cross-sectional, these associations cannot necessarily be interpreted as causal, although they are consistent with findings from other studies [3,5–8,19,20]. Of greater interest are the differences in the strength of the relationships according to whether LBP was localised or associated with pain at other anatomical sites. As well as somatising tendency, poor mental health and several psychosocial aspects of work showed significantly stronger associations with non-localised LBP. This could occur if the psychological risk factors were associated with proneness to pain more generally, and not specifically in the low back.

We are aware of only one other study that has compared the epidemiology of localised and non-localised LBP [12], and that did not investigate multiple risk factors as we have done. However, a prospective cohort study in Germany of patients who consulted general practitioners with chronic LBP, but in whom pain was not at the time widespread, found that transition to chronic widespread pain at follow-up was associated with female sex and a high rate of psychosomatic symptoms [21,22]. Non-localised LBP, as we defined it, would not necessarily be classed as chronic widespread pain – the pain may have occurred at only one other anatomical site in addition to the low back, and may have been only short-lived. Moreover, we do not know whether the onset of pain in the low back preceded or followed that at other anatomical sites. Nevertheless, our observation that non-localised LBP was differentially associated with female sex and somatising tendency is consistent with the results of the German study.

When the risk factors in Table 2 were taken into account, there were also marked differences in the relative prevalence of localised and non-localised LBP by occupational group. Thus the proportion of LBP that was localised varied from zero in New Zealand postal workers to 76.4% among sugar cane cutters in Brazil, with a tendency to be lower when the overall prevalence of LBP was higher (Figure 2). This again is an indication that localised LBP is epidemiologically distinct.

Our study sample was limited to men and women in employment, and we cannot be certain that the differences which were found between localised and non-localised LBP in severity, associations with risk factors, and prognosis, would be the same in all populations. However, their observation in a large sample of workers from 18 countries across five continents is sufficient to demonstrate that potentially important epidemiological differences do occur. This suggests that where possible, epidemiological studies on the causes and prognosis of LBP should distinguish pain that is limited to the low back from that which occurs in association with pain at other anatomical locations.

Acknowledgments

The Medical Research Council, Arthritis Research UK, NHMRC, and The Ministry of Higher Education in Malaysia funds were received in support of this work. In addition, a research training grant to Southwest Center for Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of Texas Health Science Center from the NIH Fogarty International Center, Monash University, Health Research Council of New Zealand, The Deputy for Training and Research, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, ISCII, and The Colt Foundation funded data collection.

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: consultancy, grants, employment, travel/accommodations/meeting expenses.

We thank: Pietro Muñoz, Patricio Oyos, Gonzalo Albuja, María Belduma and Francisco Lara for their assistance with data collection in Ecuador; Patrica Monge, Melania Chaverrri and Freddy Brenes, who helped with data collection in Costa Rica; Aurora Aragón, Alberto Berríos, Samaria Balladares and Martha Martínez who helped with data collection in Nicaragua; Alfredo José Jirón who assisted with data entry in Nicaragua; Catalina Torres for translation and piloting of the questionnaire in Spain; Ben and Marie Carmen Coggon for back translation of the Spanish questionnaire; Cynthia Alcantara, Xavier Orpella, Josep Anton Gonzalez, Joan Bas, Pilar Peña, Elena Brunat, Vicente San José, Anna Sala March, Anna Marquez, Josefina Lorente, Cristina Oliva, Montse Vergara and Eduard Gaynés for their assistance with data collection in Spain; Natale Battevi, Lorenzo Bordini, Marco Conti and Luciano Riboldi who carried out data collection in Italy; Paul Maurice Conway for back translation of the Italian questionnaire; Tuuli Sirk who helped with data collection in Estonia; Asad Ali Khan for supervision of data collection and checking in Pakistan; Khalil Qureshi for training of field workers and supervision of data collection and checking in Pakistan; and Masami Hirai, Tatsuya Isomura, Norimasa Kikuchi, Akiko Ishizuka and Takayuki Sawada for their help with data collection and management in Japan.

We are particularly grateful to the Colt Foundation, which funded data collection in Brazil, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, UK, Greece, Estonia, Lebanon, Pakistan and South Africa; all of the organisations that allowed us to approach their employees; and all of the workers who kindly participated in the study.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: 2

References

- 1.Coggon D, Ntani G, Palmer KT, Felli VE, Harari R, Barrero LH, et al. Disabling musculoskeletal pain in working populations: Is it the job, the person or the culture? Pain. 2013;154:856–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endean A, Palmer KT, Coggon D. Potential of MRI findings to refine case definition for mechanical low back pain in epidemiological studies: A systematic review. Spine. 2011;36:160–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181cd9adb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lötters F, Burdorf A, Kuiper J, Miedema H. Model for the work-relatedness of low back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003;29:431–40. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driessen MT, Proper KI, van Tulder MW, Anema JR, Bongers PM, van der Beek AJ. The effectiveness of physical and organisational ergonomic interventions on low back pain and neck pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:277–85. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.047548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, Field AP. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine. 2002;5:E109–E120. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200203010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramond A, Bouton C, Richard I, Roquelaire Y, Baufreton C, Legrand E, Huez JF. Psychosocial risk factors for chronic low back pain in primary care – a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2011;28:12–21. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas-Prada S, Serra C, Martinez J, Ntani G, Delclos G, Palmer K, Coggon D, Benavides F. Psychological and culturally-influenced risk factors for the incidence and persistence of low back pain and associated disability in Spanish workers: findings from the CUPID study. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:57–62. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang J, Ochsmann E, Kraus T, Lang JW. Psychosocial work stressors as antecedents of musculoskeletal problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis of stability-adjusted longitudinal studies. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1163–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer KT, Reading I, Linaker C, Calnan M, Coggon D. Population-based cohort study of incident and persistent arm pain: role of mental health, self-rated health and health beliefs. Pain. 2008;136:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer KT, Reading I, Calnan M, Linaker C, Coggon D. Does knee pain in the community behave like a regional pain syndrome? Prospective cohort study of incidence and persistence. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1190–1194. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.061481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vargas-Prada S, Coggon D. Psychological and psychosocial determinants of musculoskeletal pain and associated disability. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:374–90. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natvig B, Bruusgaard D, Eriksen W. Localised low back pain and low back pain as part of widespread musculoskeletal pain: two different disorders? A cross-sectional population study. J Rehab Med. 2001;33:21–5. doi: 10.1080/165019701300006498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haukka E, Leino-Arjas P, Solovieva S, Ranta R, Viikari-Juntura E, Riihimäki H. Co-occurrence of musculoskeletal pain among female kitchen workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006;80:141–8. doi: 10.1007/s00420-006-0113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IJzelenberg W, Burdorf A. Impact of musculoskeletal co-morbidity of neck and upper extremities on healthcare utilisation and sickness absence for low back pain. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:806–10. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.011635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coggon D, Ntani G, Palmer KT, Felli VE, Harari R, Barrero LH, et al. Patterns of multisite pain and associations with risk factors. Pain. 2013;154:1769–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coggon D, Ntani G, Palmer KT, et al. The CUPID (Cultural and Psychosocial Influences on Disability) Study: Methods of Data Collection and Characteristics of Study Sample. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, Solovieva S, Viikari-Juntura E. The association between smoking and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2010;123:87.e7–87.e35. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Main CJ, Foster N, Buchbinder R. How important are back pain beliefs and expectations for satisfactory recovery from back pain? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:205–17. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viniol A, Jegan N, Leonhardt C, et al. Study protocol: Transition from localized low back pain to chronic widespread pain in general practice: Identification of risk factors, preventive factors and key elements for treatment – a cohort study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viniol A, Jegan N, Brugger M, et al. Even worse – risk factors and protective factors for transition from chronic localized low back pain to chronic widespread pain in general practice: a cohort study. Spine. 2015;40:E890–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]