Abstract

Stroke induces a catastrophic immune response that involves the global activation of peripheral leukocytes, especially T cells. The HLA-DRα1 domain linked to MOG-35-55 peptide (DRα1-MOG-35-55) is a partial major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) construct which can inhibit neuroantigen-specific T cells and block binding of the cytokine/chemokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) to its CD74 receptor on monocytes and macrophages. Here, we evaluated the therapeutic effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 in a mouse model of permanent distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (dMCAO). DRα1-MOG-35-55 was administered to WT C57BL/6 mice by subcutaneous injection starting 4h after the onset of ischemia followed by 3 daily injections. We demonstrated that DRα1-MOG-35-55 post-treatment significantly reduced brain infarct volume, improved functional outcomes and inhibited the accumulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the ischemic brain 96h after dMCAO. In addition, DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment shifted microglia/macrophages in the ischemic brain to a beneficial M2 phenotype without changing their total numbers in the brain or blood. This study demonstrates for the first time the therapeutic efficacy of the DRα1-MOG-35-55 construct in dMCAO across MHC class II barriers in C57BL/6 mice. This MHC independent effect obviates the need for tissue typing and will thus greatly expedite treatment with DRα1-MOG-35-55 in human stroke subjects. Taken together, our findings suggest that DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment may reduce ischemic brain injury by regulating post-stroke immune responses in the brain and the periphery.

Keywords: stroke, inflammation, DRα1-MOG-35-55, T lymphocytes, microglia/macrophage

Introduction

Post-stroke inflammation includes a rapid activation of microglia followed by the infiltration of peripheral inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, T cells, B cells and macrophages. [1–4] The influx of these immune cells is known to exacerbate the brain injury and deteriorate stroke outcomes. [5–6] Therefore, reducing the brain infiltration of peripheral immune cells and reducing cerebral inflammation after stroke may represent effective therapeutic strategies. [7]

T cells are major contributors to post-stroke inflammation. It has been shown that the activation and infiltration of T cells into the brain contribute to the brain infract and neurological deficit induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [8–10]. Mice lacking T lymphocytes exhibited reduced infract size and improved neurological function after stroke [8–9, 11]. Although the mechanisms for T cell activation after brain ischemia is not completely clear, one explanation is that circulating T cells are activated when encountering myelin antigens leaked through a damaged blood-brain barrier (BBB). Activated T cells may release inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which in turn propagate an auto-aggressive immune response, facilitate the infiltration of other immune cells into the brain [12–14] and aggravate ischemic cell death [8, 15]. Thus, immunotherapy that can inhibit T cell activation and migration may reduce the inflammatory damage to the ischemic brain.

Recombinant T-cell receptor (TCR) ligands (RTL) are molecular constructs comprised of covalently linked α1 and β1 domains of the major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) molecules with an attached antigenic peptide [10–11, 16]. Unlike four-domain MHC II molecules that induce T cell activation, RTLs are partial agonists of TCR and can deviate autoreactive T cell responses [17–20]. Moreover, RTL constructs can block binding and downstream signaling of the cytokine/chemokine, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) through its CD74 receptor on monocytes and macrophages [21] (featured on MDLinx.com). RTL treatment has been shown to inhibit the brain-reactive T cells without inducing general immunosuppression [13]. Previous studies demonstrated that RTL treatment can protect against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and ischemic brain injury in mice [13, 18–19, 22–25]. However, the clinical translation of RTL to stroke treatment is restricted by the requirement for rapid matching of recipient MHC II with the β1 domains of RTL construct. Recently, a recombinant protein consisting of only the HLA-DRα1 domain (without the β1 domain) linked to MOG-35-55 peptide [26] was shown to reduce ischemic brain injury after transient MCAO [27]. Intriguingly, because the DRα1 domain is expressed in all humans, DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment does not require HLA screening of potential recipients and could be used immediately in patients with acute ischemic injury.

Since many cases of stroke in humans are non-reperfused, we here test the effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 in a permanent distal MCAO model of stroke. We demonstrate that DRα1-MOG-35-55 given after permanent stroke induction reduces infract size and improve functional outcomes without reversing spleen atrophy after dMCAO. We further showed that DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment not only reduced the influx of T cells into the ischemic brain, but also shifted microglia/macrophage polarization toward a beneficial M2 phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Murine model of permanent distal MCAO

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with the principles outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male C57/BL6 mice (8–10w, 25–30g body weigh) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice were subjected to distal MCAO as described previously [28]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized and cut an incision in the middle of neck. Left carotid common artery was ligated. The distal part of middle cerebral artery was then coagulated by bipolar electrocautery (Bipolar Coagulator, Codamn & Shurtleff Inc., Randolph, MA, USA). Cerebral blood flow was monitored and animals with less than 70% original cerebral blood flow were excluded.

Drug treatment

Mice that were subjected to dMCAO were randomized. DRα1-MOG-35-55 (100µl, 1mg/mL) or the same volume of vehicle (Tris-HCl, pH=8.5) was administered by subcutaneous injection starting 4h after the onset of ischemia, followed by daily administration for another 3 days.

Measurements of infarct volume

Infarct volume was measured by 2.3.5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining as previously described [28]. Briefly, brains were removed and sliced to generate 1-mm sections. Sections were stained in pre-warmed 2% 2.3.5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) in saline for 10 minutes and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4. National institutes of Health Image J software was uses to analyze the infarct volume by a person blinded to the experiment group. The actual infarct volume was corrected as the volume of the contralateral hemisphere minus the non-infarct volume of the ipsilateral hemisphere.

Rotarod test

The rotarod test was performed to access motor function as previously described [29]. Animals were placed on a rotating rod at an accelerating speed from 4 to 120 rpm over 120s. The latency to fall was recorded. Training (three trials each day) was performed 3 d before surgery. The mean of three trials on the day before surgery was recorded for each mouse and was used as the pre-stroke baseline value. Each mouse was tested three times on days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 after stroke. The mean value of latency to fall was calculated and analyzed.

Adhesive removal

Adhesive removal was performed to access sensorimotor function as described previously [30]. Briefly, mice were habituated in the testing box for 1 min and then gently covered with an adhesive tape with equal pressure on the right paw of each mouse. The time to contact and time to remove the tape were recorded with maximum duration of 120 seconds. Pre-training began 3d before surgery and consisted of 3 trials each day. The mean of three trials on the day before surgery were recorded as the pre-stroke baseline value. Each mouse was tested for three trials on days 1, 3, 5 and 7. Data were expressed as time to contact and time to remove the tape on each testing day.

Modified Garcia score

The modified Garcia Score system was established to access sensorimotor function [31]. Briefly an observer blinded to the experimental group evaluated the performance of each mouse at days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 post-surgery. The score consists of 5 tests: body proprioception, vibrissae touch, limb symmetry, lateral turning and forelimb walking with scores of 0–3 for each test (Maximum score equal to 15). Baseline was recorded on each mouse on the day before surgery.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from sham brains and ischemic brains using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction; 1µg of RNA was used to synthesize the first strand of cDNA using the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). PCR was performed on the Opticon 2 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using corresponding primers and SYBR gene PCR Mix (invitrogen). Primers used are as follows: IL-1β forward primer: GCCCATCCTCTGTGACTCGA, reverse primer: AGCTCATATGGGTCCGACAG; IL-17 forward primer: TCCCTCTGTGATCTGGGAAG, reverse primer: CTCGACCCTGAAAGTAAGG; TNF-α forward primer: AGAAGTTCCCAAATGGCCTC, reverse primer: CCACTTGGTGGTTTGCTACG; IFN-γ forward primer: GCGTCATTGAATCACACCTG, reverse primer: TGAGCTCATTGAATGCTTGG. Expression of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA served as an internal control. The expression levels of the mRNAs were reported as fold change vs. sham control.

Tissue preparation and Immunohistochemistry

Brain tissue was prepared and subjected to immunohistochemistry staining as before [32–33]. Primary antibodies include goat anti-CD206 (1:100; R&D System, Minneasolis, MN, USA), rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:1000, Wako, Richmond, VA, USA), F4/80 (1:200, Biolegend). All images were processed with Image J for cell counting. Averaged cell numbers were calculated from 2 randomly selected microscopic fields, and 3 consecutive sections were analyzed for each brain. Data are expressed as mean numbers of cells per square millimeter.

Single cell preparation from spleen, blood and brain

Spleen, blood and brain were collected after dMCAO and single-cell suspensions were prepared for flow cytometry analysis. Briefly, brain was first dissociated into a single-cell suspension by using gentleMACS Dissociators (Miltenyl Biotec) following the manufacture’s instruction. The suspension was passed through a 70-µm cell strainer, resuspended in 30% Percoll (GE health) and overlaid to 3mL with 70% Percoll. Cells were separated at 500g for 30 minutes at 18 °C. The cells in the interface were collected and washed before staining. Peripheral blood was obtained from mice by cardiac puncture and the red blood cells were lysed by ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich). Spleens from individual sham and dMCAO mice were removed and single cell suspensions were isolated, followed by lysis of red blood cells using ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer. Isolated cells were resuspended and stained.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with fluorophore-labeled mouse CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45, CD11b, CD19 or NK1.1 antibodies following manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience). Flow Cytometric analysis was performed using a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis

All data were reported as mean±SD. Comparison of means between two groups was accomplished by the Student's t-test (two tailed). Differences in means among multiple groups were analysed using one- or two-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment significantly reduces infarct size at 4d after dMCAO

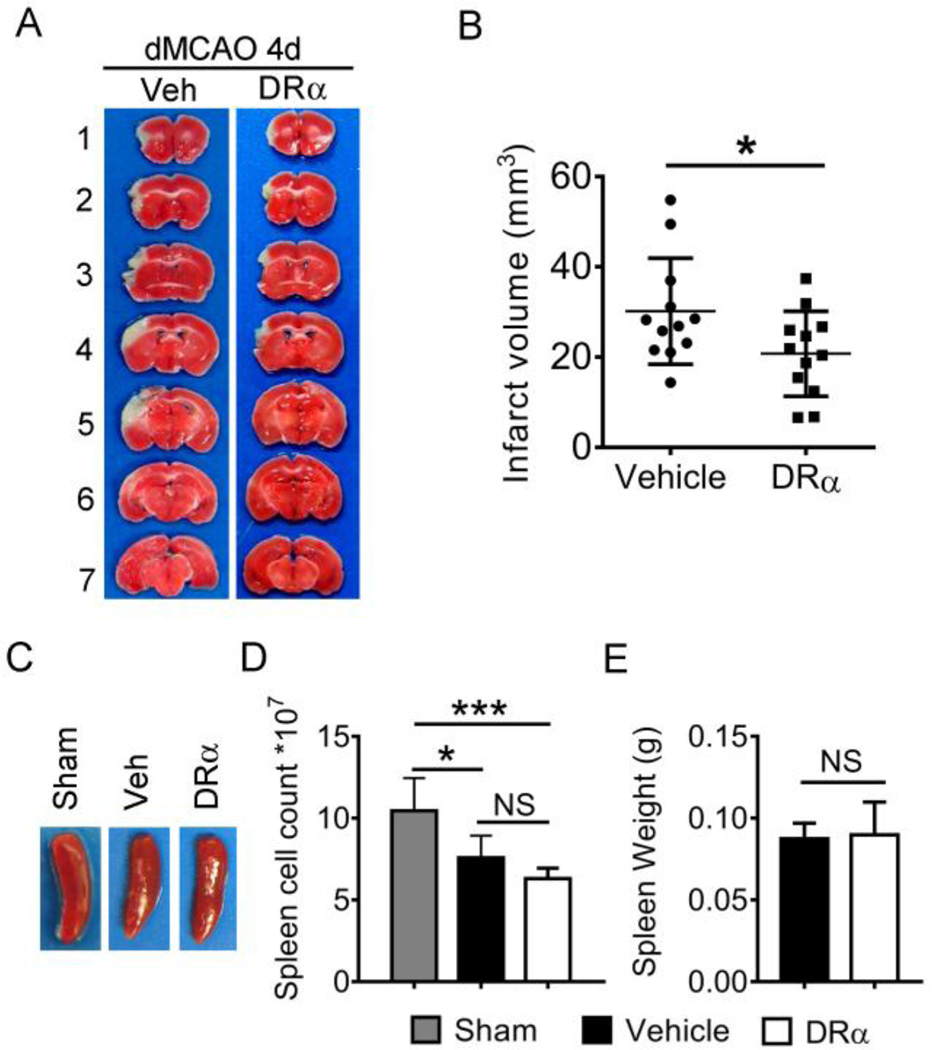

Daily subcutaneous treatment with DRα1-MOG-35-55-MOG-35-55 for 4 consecutive days significantly reduced the infarct volume 4d after the onset of dMCAO as compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 1A and 1B, 30.18±3.19 in vehicle; n=12 versus 20.76±2.72 in DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated mice; n=12, P<0.05). We also evaluated the effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment on stroke-induced splenic atrophy. As expected, the size of spleen and the number of cells in the spleen was significantly reduced at 4d after dMCAO. However, the DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated and vehicle-treated mice showed comparable sizes of spleen (Fig. 1C). Similarly, there was no difference in the number of splenocytes between vehicle-treated and DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated mice at 4d post-dMCAO (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment reduces infract size 4d after dMCAO.

Mice were subjected to dMCAO. Vehicle (Tris-HCl) or 100µg DRα1-MOG-35-55 was injected subcutaneously at 4h, 1d, 2d and 3d after dMCAO. Brains were collected at 4d after dMCAO. (A) Representative TTC-stained brains in vehicle and DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated mice. (B) Quantification of infarct volume, n=12 animals per group. *p<0.05 by Student’s t test. (C) Images of spleens obtained from sham, vehicle and DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated dMCAO mice. (D) The number of cells in the spleens from sham (n=5), vehicle (n=4) and DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated dMCAO mice (n=6). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA follow by Bonferroni test.

DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment significantly augments sensorimotor functions after dMCAO

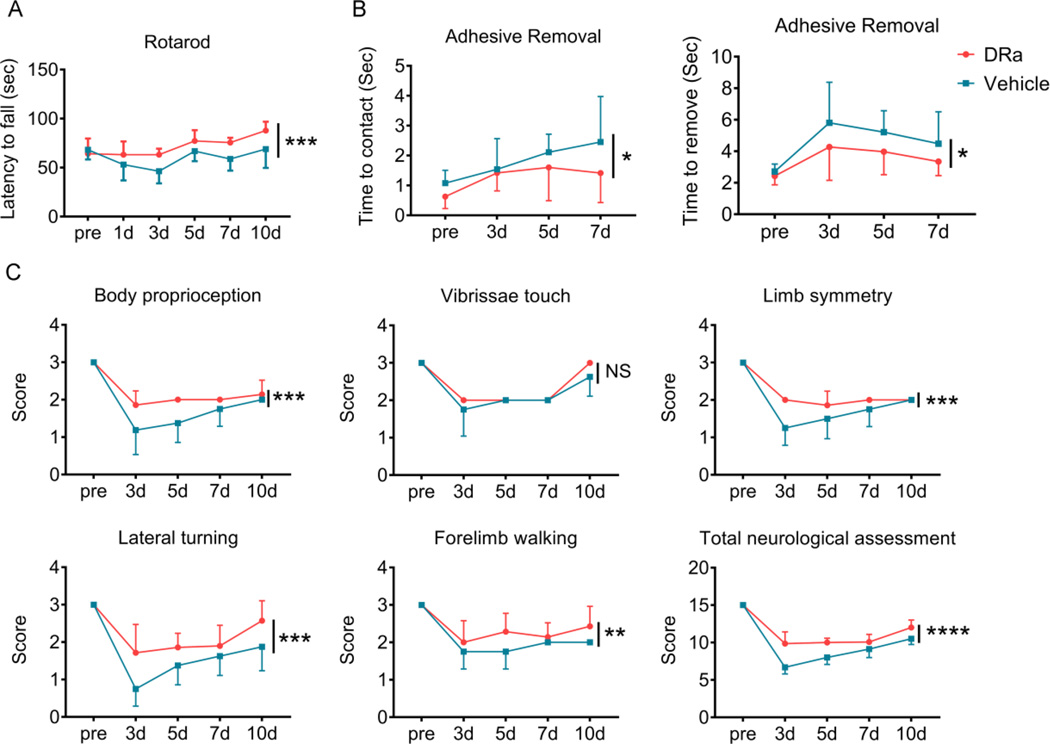

In order to evaluate the effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 on functional outcomes after dMCAO, a battery of neurological behavior tests were performed. The DRα-MOG-35-55-treated group exhibited significant improvement compared with the vehicle-treated group in the rotarod test (Fig. 2A). Similarly, mice with DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment showed better performance in the adhesive removal test (Fig. 2B). The Garcia score was also used to measure the behavioral deficits (Fig.2C). Mice in the vehicle-treatment group showed deficits in body proprioception, limb symmetry, lateral turning, and forelimb walking at different times after stroke, which were ameliorated by DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment improved the short-term behavioral functions after dMCAO.

Fig. 2. DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment significantly improves sensorimotor functions after dMCAO.

Sensorimotor functions were measured up to 10 d after dMCAO in mice with vehicle or DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment. n=8 for vehicle group and n=5 for DRα1 MOG-35-55-treated group. (A) Rotarod test. (B) Adhesive removal test. (C) Modified Garcia scores. The total neurologic assessment score includes body proprioception, vibrissae touch, limb symmetry, lateral turning, forelimb walking. NS: no significance, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, by two-way ANOVA. Error bars are SD.

DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment reduces the gene expression of inflammatory cytokines in the ischemic brain after distal MCAO

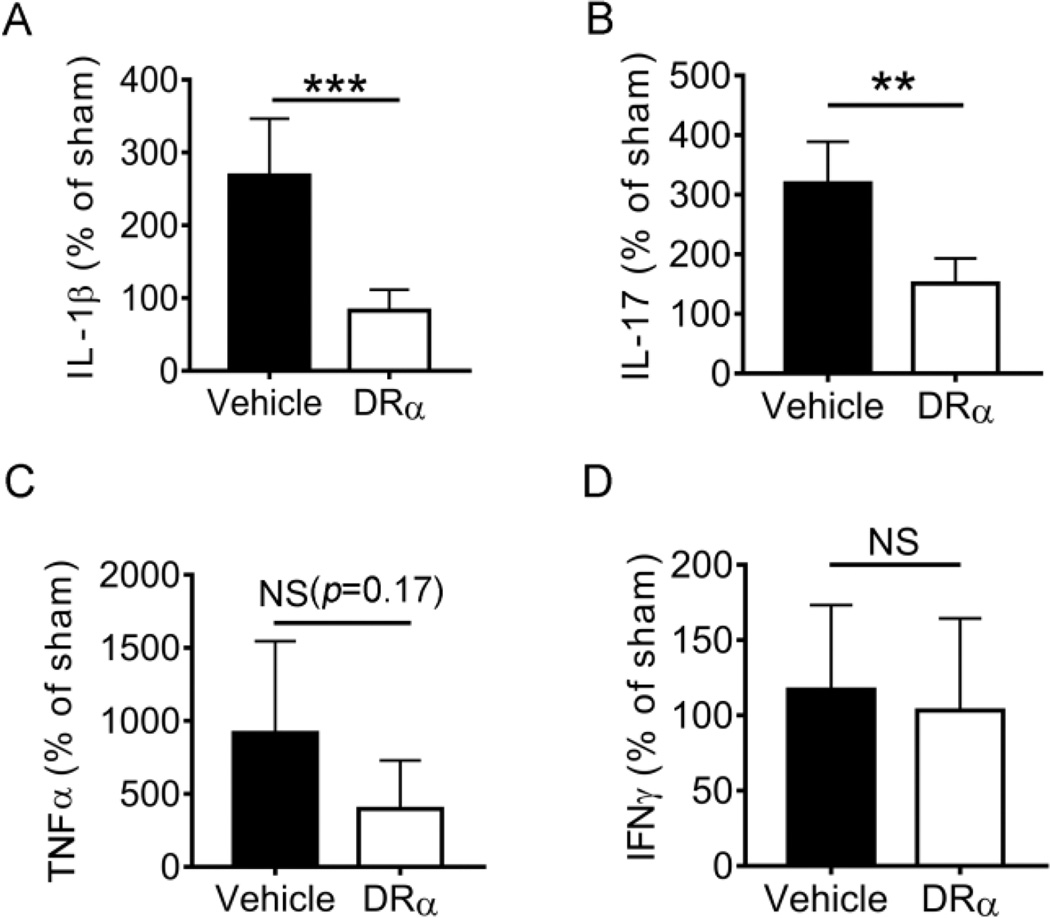

In order to evaluate the effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment on cerebral inflammation after dMCAO, we measured the mRNA expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines in the ischemic brain using RT-PCR at 4d after dMCAO. As shown in Fig. 3A and 3B, DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment significantly reduced the expression of IL-1β and IL-17 in ipsilateral hemispheres compared to that of vehicle-treated mice. There was no significant difference in the expression of TNF-α (Fig. 3C) or IFN-γ (Fig. 3D) between DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment and vehicle treatment.

Fig. 3. DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment affects gene expression of inflammatory cytokines in the ischemic brain after dMCAO.

Gene expression of IL-1β, IL-17, TNF-α and IFN-γ was measured by RT-PCR 4d after ischemia. Results are reported as percentage vs. sham control. n=6 for vehicle group and n=5 for DRα-MOG-35-55 group, Data are mean ± SD. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Student’s t test.

DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment inhibits influx of T lymphocytes after dMCAO

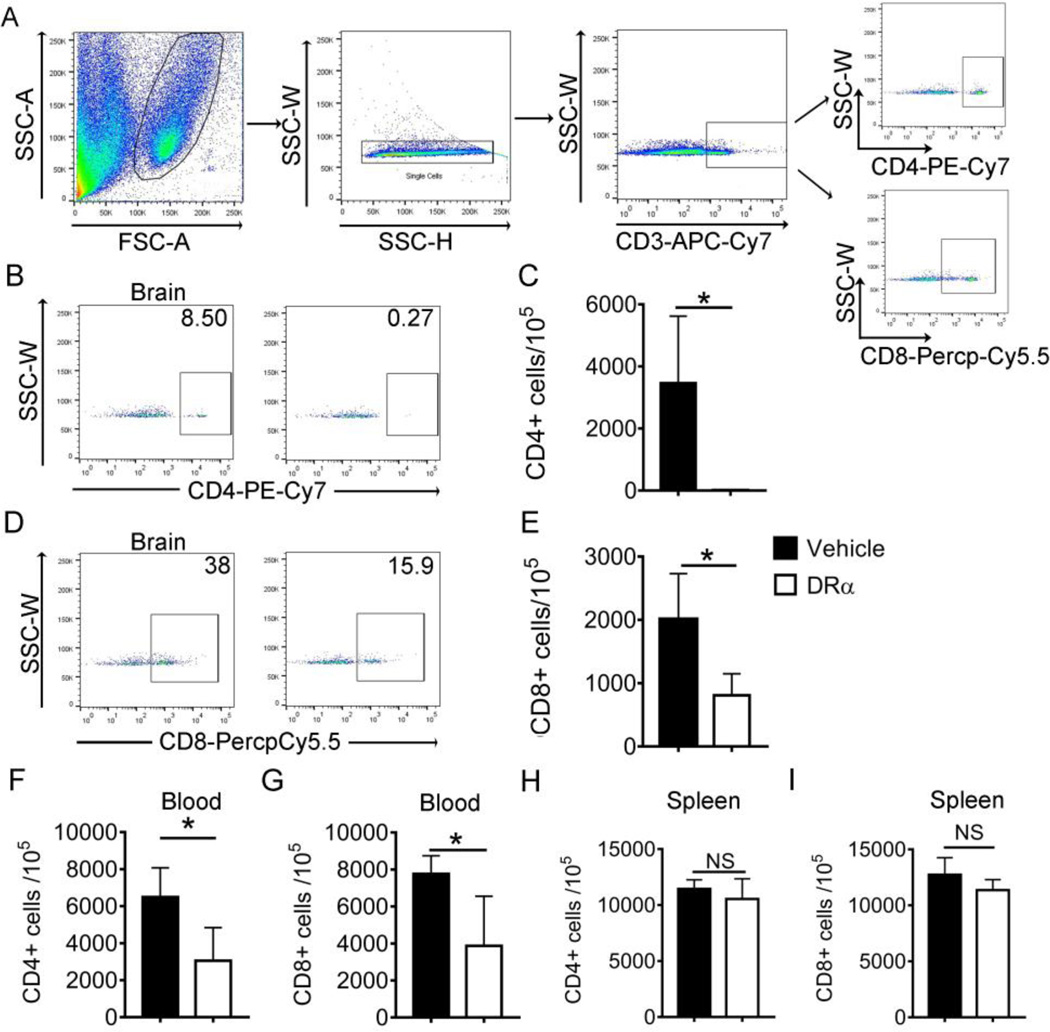

We then evaluated the effects of DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment on immune cell infiltration into the ischemic brain at 4d after dMCAO. The brain tissue was collected from the ipsilateral brain and single cell suspension was prepared for FACS analysis. The cells were gated to exclude debris and doublets (Fig. 4A). The results showed that DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment markedly decreased the number of CD3+CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4B and 4C) and CD3+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4D and 4E) in the ischemic hemisphere compared to those of the vehicle-treated mice. Similarly, the number of CD3+CD4+ T cells and CD3+CD8+ T cells in the blood of DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated mice was significantly decreased compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 4F and 4G). In contrast, there was no difference in the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in the spleen between DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated and vehicle-treated groups (Fig. 4H and 4I).

Fig. 4. DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment inhibits influx of T lymphocytes after dMCAO.

Total brain cells were isolated from ischemic hemisphere 4d after DRα1-MOG-35-55 or vehicle treatment. Flow cytometry was used to evaluate the cell number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry plot for gating strategy. (B-C) Representative plot and quantification of CD4+CD3+ T cells in the ischemic brain. (D-E) Representative plot and quantification of CD8+CD3+ T cells in the ischemic brain. (F-G) Quantification of CD4+CD3+ and CD8+CD3+ T cells in the blood. (H-I) Quantification of CD4+CD3+ and CD8+CD3+ T cells in the spleen. Data were presented as mean±SD. n=4 for each group,*p<0.05 by Student’s t test.

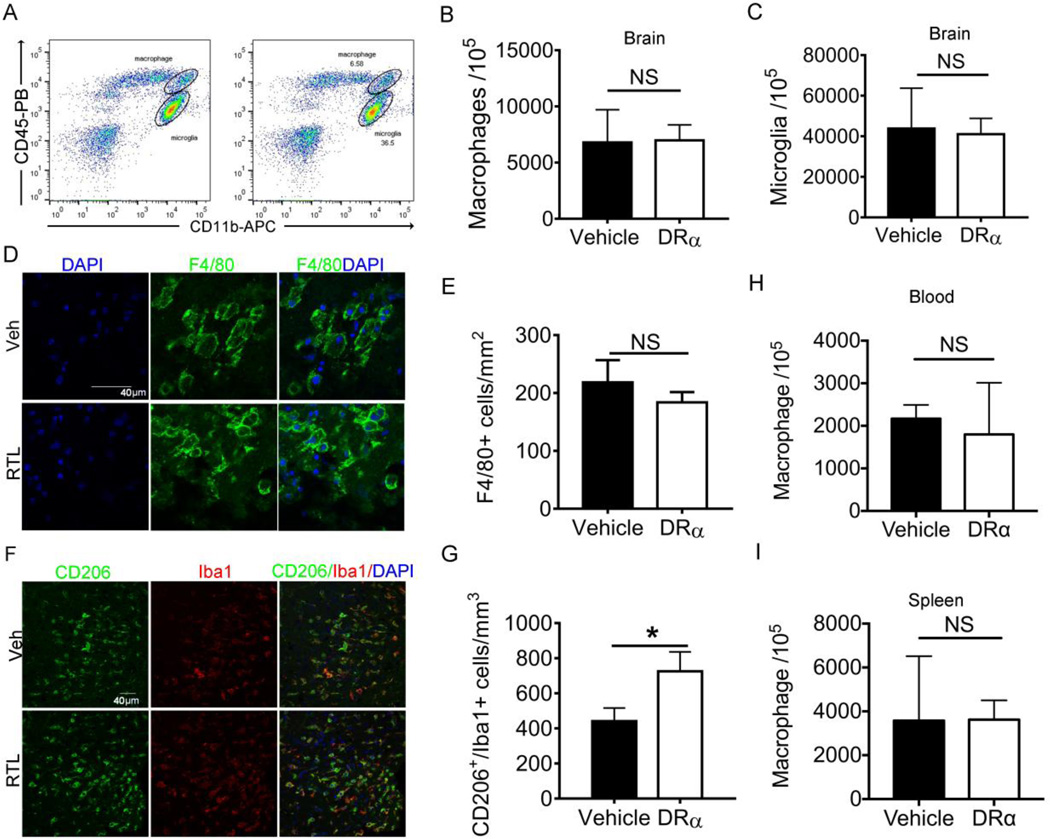

DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment enhances M2 polarization of microglia/macrophage in the ischemic brain after dMCAO

It has been demonstrated that DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment can reduce the number of activated macrophages in the transient MCAO model [27]. Therefore, we sought to assess whether DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment can also reduce the number of activated microglia/macrophage in distal permanent model of stroke. CD11b+CD45intermediate microglia and CD11b+CD45high macrophages were distinguished by flow cytometry (Fig. 5A). The total number of macrophages and microglia showed no difference between DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated and vehicle-treated mice at day 4 after dMCAO (Fig. 5B and 5C). Immunofluorescent staining of F4/80 confirmed comparable numbers of F4/80+ macrophages in the ischemic areas in DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated and vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 5D and 5E). Interestingly, the expression of the M2 marker, CD206, was significantly upregulated in Iba1+ microglia/macrophage in DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated mice as compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 5F and 5G). These results suggest that although DRα1-MOG-35-55 does not reduce the number of activated microglia/macrophage after dMCAO, it can shift microglia/macrophage toward a beneficial M2 phenotype. Similar to the brain, the number of macrophages in blood and spleen showed no difference between DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated and vehicle-treated mice 4 days after dMCAO (Fig. 5H and 5I).

Fig. 5. DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment enhances M2 polarization of microglia/macrophage in the ischemic brain after dMCAO.

Mice were subjected to dMCAO. Vehicle (Tris-HCl) or 100µg DRα1-MOG-35-55 was injected subcutaneously at 4h, 1d, 2d and 3d after dMCAO. Brains were obtained from mice 4d after distal MCAO. (A-C) Flow cytometry analysis in the samples of the ischemic brain. There was no change in the number of microglia and macrophage. (D) Representative images of brain immunostaining of F4/80+ macrophages. Scale bar: 20µm. (E) Quantification of (D). (F) Representative images of double immunofluorescent staining of CD206 and Iba1 on brain sections. Scale bar: 40µm. (G) Quantification of (F). (H-I) Number of microglia in the blood (H) and spleen (I). n=3 in vehicle group and 4 for DRα1-MOG-35-55 group. Data are presented as mean±SD. *p<0.05 by Student’s t test.

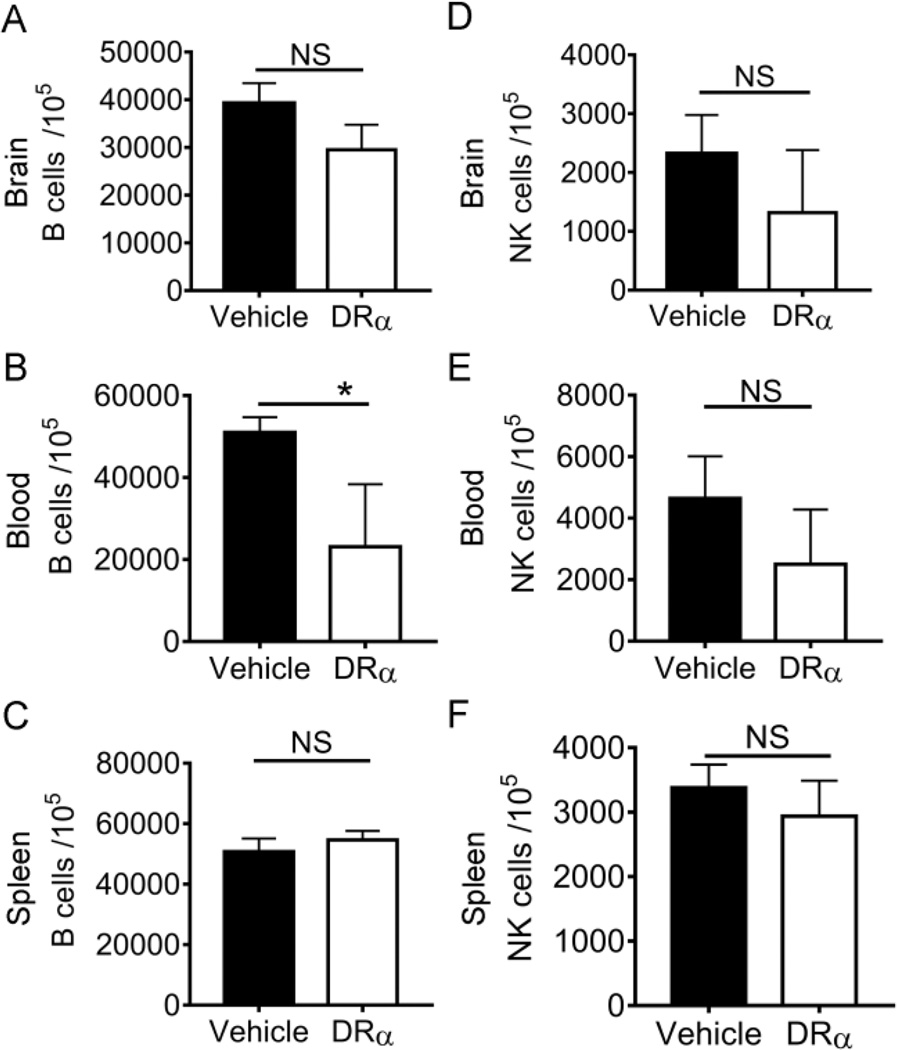

DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment has minimal effect on B cell and NK cell populations in the ischemic brain after dMCAO

We also evaluated the effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 on CD19+ B lymphocytes and NK1.1+ natural killer (NK) cells in the brain, blood and spleen at 4 days after dMCAO. No difference was observed in the number of B cell in the brain (Fig. 6A) and spleen (Fig. 6C) between vehicle and DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment at 4d post-dMCAO. The number of B cells in the blood was significantly decreased in DRα1-MOG-35-55-treated mice compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 6B). DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment did not have an effect on the number of NK cells in the brain, blood and spleen after dMCAO (Fig. 6D-6F).

Fig. 6. DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment has minimal effect on B cell and NK cell populations in the ischemic brain 4d after dMCAO.

Cells were isolated from the ischemic hemisphere, the blood and the spleen 4d after ischemia. Flow cytometry was used to evaluate the number of B cells (A-C) and NK cells (D-F) in the ischemic brain, blood and spleen. n=3 in vehicle group and 4 for DRα1-MOG-35-55 group. Data are presented as mean±SD. *p<0.05 by unpaired Student’s t test.

Discussion

Stroke is considered a classical acute brain injury that is closely associated with inflammation both inside and outside the brain. Interventions aimed at harnessing post-stroke inflammation are considered as promising avenues for stroke management [34]. Our study here demonstrates that treatment of permanent dMCAO in HLA-class II mismatched C57BL/6 mice with DRα1-MOG-35-55 can significantly reduce the infarct size, block the infiltration of T cells into the ischemic brain, shift microglia/macrophage to a beneficial M2 phenotype and enhance functional outcomes. These results extend our previous studies showing treatment of transient MCAO with RTL1000 constructs in which efficacy was limited to MHC class II matched HLA-DR2-Tg mice.

DRα1-MOG-35-55 as well as RTL were initially used as a therapy for EAE, a murine model for multiple sclerosis, which may involve increased CD4+ T cell responses against myelin antigens [18, 35]. Antigen-specific T cell responses are also prominent after stroke [36]. In particular, the infiltration of MOG-specific T cells into the brain was observed after experimental stroke [12]. Similarly, in vivo expansion of myelin reactive T cells was detected in the cortical spinal fluid (CSF) of stroke patients [37]. Moreover, the increased T cell reactivity to myelin was correlated with stroke severity and worse outcome at follow-up [37–38]. This might explain why blocking the MOG specific T cells with DRα1-MOG-35-55 could reduce local inflammation and provide protection to the ischemic brain.

Our data demonstrated a strong capacity of DRα1-MOG-35-55 to inhibit the infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells into the ischemic brain and reduce the number of circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after dMCAO. Based on the structure of DRα1-MOG-35-55, its inhibitory effect on CD8+ T cells might be secondary to its primary effect on CD4+ T cells. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 seems to be specific for T cells as DRα1-MOG-35-55 showed minimal effects on other immune cells including macrophages, B cells and NK cells. Notably, it is reported in the transient stroke model with reperfusion that DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment could inhibit the infiltration of CD11b+CD45high macrophages into the ischemic brain. However, in the permanent stroke model, we did not observe the same phenomenon. This discrepancy might be due partially to the different temporal file of macrophage infiltration in these two stroke models. A comparison study showed that the influx of macrophages into the ischemic brain after permanent MCAO is relatively delayed as compared to transient MCAO [39]. Moreover, as revealed by bone-marrow transplant chimeras, the majority of macrophage-like cells in the ischemic brain are activated microglia but not blood-derived macrophages, especially during the first few days following permanent cerebral ischemia [40].

Despite the lack of effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 on the number of activated microglia/macrophages, our data demonstrated an effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 on promoting M2 polarity of these phagocytes. It is well known that microglia/macrophages are highly dynamic cells that can assume different functional status under stimulation. Specifically, the M1-like microglia/macrophages could accentuate brain damage while the M2-like microglia/macrophages preserved brain tissue after ischemic injury [41]. Our previous study has revealed a gradual shifting of microglia/macrophage polarity toward M2 with the progress of ischemic brain injury [42]. Therefore, the effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 to shift microglia/macrophage polarity toward a beneficial M2-like phenotype may partially contribute to the protection of the ischemic brain. Since microglia/macrophage phenotype change is also common in other forms of CNS injuries [43], the effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 on other neurological disorders such as intracerebral hemorrhage needs to be examined.

It is also noted that although DRα1-MOG-35-55 treatment ameliorated splenic atrophy in the transient model of stroke, it showed no effect on the permanent model. This might be due to the less severe splenic atrophy in the distal model compared with the transient model. Consistent with this observation, DRα1-MOG-35-55 showed very little effect on the number of different immune cells in the spleen. Therefore, the circulating T cells might be the main peripheral target for DRα1-MOG-35-55.

In summary, this study shows the therapeutic effect of DRα1-MOG-35-55 in a permanent model of stroke and elucidates the immunomodulatory effect of this drug on T cells and microglia/macrophages. Based on the potency of DRα1-MOG-35-55 to reduce acute brain infarct in both transient [27] and permanent models of stroke and its ability to treat across MHC barriers thus obviating need for tissue typing in human stroke subjects, further studies are warranted to explore its long-term effects on brain integrity and functional recovery after stroke.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grants R01NS075887 (HO) and R01NS076013 (HO) and by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Offner, Dr. Benedek, Dr. Meza-Romero and Dr. Vandenbark and OHSU have a significant financial interest in Artielle Immunotherapeutics, Inc., a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by the OHSU and VAMC Conflict of Interest in Research Committees. No other authors have a conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants.

References

- 1.Liesz A, Kleinschnitz C. Regulatory T Cells in Post-stroke Immune Homeostasis. Transl Stroke Res. 2016;7(4):313–321. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An C, et al. Molecular dialogs between the ischemic brain and the peripheral immune system: dualistic roles in injury and repair. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;115:6–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S, et al. An update on inflammation in the acute phase of intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6(1):4–8. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CM, et al. Chronic Systemic Immune Dysfunction in African-Americans with Small Vessel-Type Ischemic Stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6(6):430–436. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0424-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrone AB, et al. The Role of Arginase 1 in Post-Stroke Immunosuppression and Ischemic Stroke Severity. Transl Stroke Res. 2016;7(2):103–110. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0431-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atangana E, et al. Intravascular Inflammation Triggers Intracerebral Activated Microglia and Contributes to Secondary Brain Injury After Experimental Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (eSAH) Transl Stroke Res. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang B, et al. Various Cell Populations Within the Mononuclear Fraction of Bone Marrow Contribute to the Beneficial Effects of Autologous Bone Marrow Cell Therapy in a Rodent Stroke Model. Transl Stroke Res. 2016;7(4):322–330. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0462-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yilmaz G, et al. Role of T lymphocytes and interferon-gamma in ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2006;113(17):2105–2112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurn PD, et al. T- and B-cell-deficient mice with experimental stroke have reduced lesion size and inflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(11):1798–1805. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu W, et al. Preclinical evaluation of recombinant T cell receptor ligand RTL1000 as a therapeutic agent in ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6(1):60–68. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0373-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan J, et al. Novel humanized recombinant T cell receptor ligands protect the female brain after experimental stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5(5):577–585. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0345-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dirnagl U, et al. Stroke-induced immunodepression: experimental evidence and clinical relevance. Stroke. 2007;38(2 Suppl):770–773. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251441.89665.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dziennis S, et al. Therapy with recombinant T-cell receptor ligand reduces infarct size and infiltrating inflammatory cells in brain after middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Metab Brain Dis. 2011;26(2):123–133. doi: 10.1007/s11011-011-9241-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frenkel D, et al. Nasal vaccination with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein reduces stroke size by inducing IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171(12):6549–6555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87(5):779–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu W, et al. Recombinant T cell receptor ligand treatment improves neurological outcome in the presence of tissue plasminogen activator in experimental ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5(5):612–617. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burrows GG, et al. Design, engineering and production of functional single-chain T cell receptor ligands. Protein Eng. 1999;12(9):771–778. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burrows GG, et al. Rudimentary TCR signaling triggers default IL-10 secretion by human Th1 cells. J Immunol. 2001;167(8):4386–4395. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandenbark AA, et al. Recombinant TCR ligand induces tolerance to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 35–55 peptide and reverses clinical and histological signs of chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in HLA-DR2 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2003;171(1):127–133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, et al. Recombinant TCR ligand induces early TCR signaling and a unique pattern of downstream activation. J Immunol. 2003;171(4):1934–1940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandenbark AA, et al. A novel regulatory pathway for autoimmune disease: binding of partial MHC class II constructs to monocytes reduces CD74 expression and induces both specific and bystander T-cell tolerance. J Autoimmun. 2013;40:96–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian S, et al. Recombinant T cell receptor ligand treats experimental stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2539–2545. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burrows GG, et al. Two-domain MHC class II molecules form stable complexes with myelin basic protein 69–89 peptide that detect and inhibit rat encephalitogenic T cells and treat experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1998;161(11):5987–5996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huan J, et al. Monomeric recombinant TCR ligand reduces relapse rate and severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in SJL/J mice through cytokine switch. J Immunol. 2004;172(7):4556–4566. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dotson AL, et al. Partial MHC Constructs Treat Thromboembolic Ischemic Stroke Characterized by Early Immune Expansion. Transl Stroke Res. 2016;7(1):70–78. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meza-Romero R, et al. HLA-DRalpha1 constructs block CD74 expression and MIF effects in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2014;192(9):4164–4173. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benedek G, et al. A novel HLA-DRalpha1-MOG-35-55 construct treats experimental stroke. Metab Brain Dis. 2014;29(1):37–45. doi: 10.1007/s11011-013-9440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suenaga J, et al. White matter injury and microglia/macrophage polarization are strongly linked with age-related long-term deficits in neurological function after stroke. Exp Neurol. 2015;272:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouet V, et al. Sensorimotor and cognitive deficits after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the mouse. Exp Neurol. 2007;203(2):555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouet V, et al. The adhesive removal test: a sensitive method to assess sensorimotor deficits in mice. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(10):1560–1564. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doyle KP, et al. Distal hypoxic stroke: a new mouse model of stroke with high throughput, low variability and a quantifiable functional deficit. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;207(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An C, et al. Severity-Dependent Long-Term Spatial Learning-Memory Impairment in a Mouse Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pu H, et al. Delayed Docosahexaenoic Acid Treatment Combined with Dietary Supplementation of Omega-3 Fatty Acids Promotes Long-Term Neurovascular Restoration After Ischemic Stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0498-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leonardo CC, Pennypacker KR. The Splenic Response to Ischemic Stroke: What Have We Learned from Rodent Models? Translational Stroke Research. 2011;2(3):328–338. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bielekova B, et al. Expansion and functional relevance of high-avidity myelin-specific CD4+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2004;172(6):3893–3904. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urra X, et al. Antigen-specific immune reactions to ischemic stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:278. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang WZ, et al. Myelin antigen reactive T cells in cerebrovascular diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;88(1):157–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Planas AM, et al. Brain-derived antigens in lymphoid tissue of patients with acute stroke. J Immunol. 2012;188(5):2156–2163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gronberg NV, et al. Leukocyte infiltration in experimental stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:115. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka R, et al. Migration of enhanced green fluorescent protein expressing bone marrow-derived microglia/macrophage into the mouse brain following permanent focal ischemia. Neuroscience. 2003;117(3):531–539. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00954-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu X, et al. Microglial and macrophage polarization-new prospects for brain repair. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(1):56–64. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu X, et al. Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2012;43(11):3063–3070. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wan S, et al. Microglia Activation and Polarization After Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Mice: the Role of Protease-Activated Receptor-1. Transl Stroke Res. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0472-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]