Abstract

The competition between sulfate reducing bacteria and methanogens over common substrates has been proposed as a critical control for methane production. In this study, we examined the co-existence of methanogenesis and sulfate reduction with shared substrates over a large range of sulfate concentrations and rates of sulfate reduction in estuarine systems, where these processes are the key terminal sink for organic carbon. Incubation experiments were carried out with sediment samples from the sulfate-methane transition zone of the Yarqon (Israel) estuary with different substrates and inhibitors along a sulfate concentrations gradient from 1 to 10 mM. The results show that methanogenesis and sulfate reduction can co-exist while the microbes share substrates over the tested range of sulfate concentrations and at sulfate reduction rates up to 680 μmol L-1 day-1. Rates of methanogenesis were two orders of magnitude lower than rates of sulfate reduction in incubations with acetate and lactate, suggesting a higher affinity of sulfate reducing bacteria for the available substrates. The co-existence of both processes was also confirmed by the isotopic signatures of δ34S in the residual sulfate and that of δ13C of methane and dissolved inorganic carbon. Copy numbers of dsrA and mcrA genes supported the dominance of sulfate reduction over methanogenesis, while showing also the ability of methanogens to grow under high sulfate concentration and in the presence of active sulfate reduction.

Keywords: sulfate reduction, methanogenesis, substrates, estuaries, co-existence

Introduction

Estuarine and shallow shelf sediments are often characterized by high fluxes of nutrients, high loads of organic carbon and marine salinity, thus containing high sulfate concentrations and housing intensive bacterial sulfate reduction and methanogenesis. Estuarine sediments account for 10% of oceanic carbon emission rates, despite its relatively small area (Bange et al., 1994; Abril and Iversen, 2002). Nevertheless, our knowledge of the competition and co-existence between sulfate reduction and methanogenesis in these sediments is limited, and specifically it has yet to be determined whether they can co-exist while the active microbes sharing the same substrates. Furthermore, it is important to explore the conditions governing both the rates and initiation of methanogenesis in estuarine sediments. Here we examine the co-existence of methanogenesis and sulfate reduction while the microbes share the same substrates over a range of sulfate concentrations and rates of sulfate reduction through incubation experiments with sediment samples from the sulfate-methane transition zone of the Yarqon estuary (Israel).

The conventional paradigm states that thermodynamics govern biochemical depth profiles, and therefore in sedimentary environments, microbial processes that out-compete substrate uptake will suppress, or outcompete, other microbial processes, shifting the latter to greater depths in the sediment (Froelich et al., 1979; Stumm and Morgan, 1996). Despite this paradigm, a number of studies have shown that microbial processes can co-exist in complex sedimentary systems due to competition for electron donors rather than the difference in energy yield (Oremland and Taylor, 1978; Lovley et al., 1982). Examples of co-occurrence has been documented in the Black Sea sediments in which methane production was found within the sulfate reduction zone (Dale et al., 2008; Knab et al., 2008). Co-existence of sulfate reduction and methanogenesis characterizes also the coastal sediments of North Sea estuary. This co-existence was suggested to be controlled by the fast sediment accumulation combined with high organic carbon loading (Egger et al., 2016). These studies and others have emphasized that the various redox processes can co-exist in natural environments and may be coupled in a way that changes the rates of production or consumption of chemical species. These couplings would impact their distribution depth and their link to the subsurface carbon cycle. The co-existence between sulfate reduction and methanogenesis can occur at the interface between sulfate and methane, often termed the sulfate methane transition zone (SMTZ). Anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) coupled to sulfate reduction is typically found within this zone in marine sediments and has a large significance in controlling methane emission from marine sediment (Borowski et al., 2000; Archer, 2007; Knittel and Boetius, 2009). This process has been shown to consume up to 90% of the upward methane fluxes in marine sediments (Borowski et al., 1996; Valentine and Reeburgh, 2000).

Acetate and hydrogen are the preferred substrates for both sulfate reduction and methanogenesis (Schink, 1997; Conrad, 1999; Chidthaisong and Conrad, 2000a). From a thermodynamic perspective (Thauer et al., 1977; Schönheit et al., 1982; Ward and Winfrey, 1985; Lovley and Phillips, 1988) sulfate reducing bacteria can utilize hydrogen and acetate at lower concentrations than methanogens and therefore will likely outcompete them for substrate uptake, channeling the electron flow toward CO2 production rather than methane (Lovley et al., 1982; Oremland and Polcin, 1982; Lovley and Klug, 1983; King, 1984; Lovley and Goodwin, 1988). Sulfate reduction is known to restrict methanogenesis through several paths. In complex environments such as natural sediments, in the presence of sulfate reducing bacteria and methanogens, sulfate supplementation or high sulfate concentrations will inhibit methanogenesis, diverting the electron flow toward sulfate reduction (Mountfort et al., 1980; Mountfort and Asher, 1981).

Nevertheless, methanogenesis has been detected in zones dominated by sulfate reduction in marine and salt marsh sediments (Oremland and Taylor, 1978; Dale et al., 2008; Treude et al., 2014). This methanogenesis is assumed to be the product of non-competitive substrate uptake, (i.e., substrates that are consumed only by methanogens) such as methanol, methane thiol and methylamines (Oremland and Polcin, 1982; Kiene et al., 1986). Another mechanism that can explain the coexistence of methanogenesis and sulfate reduction is a cooperation between acetoclastic sulfate reducing bacteria that produce hydrogen and hydrogenotrophic methanogens (Ozuolmez et al., 2015). It can be also be a coupling between methanogens and fermentative (hydrogen producing) Clostridia (Oremland and Taylor, 1978) that may also support methane production in sulfate-enriched environments. On the other hand, inhibition of methanogenesis by sulfate reduction can be the result of the toxicity of sulfide, the product of sulfate reduction (Koster et al., 1986), even though one study suggested that the methanogen Methanosarcina barkeri could tolerate sulfide concentrations as high as 20 mM (Mountfort et al., 1980). Therefore, the conditions under which sulfate reduction and methanogenesis can co-exist in natural sedimentary environments and specifically in estuaries, and the possibility of these processes to share ambient substrates are still unclear. The goal of this study was to define the terms in which the methanogenesis and sulfate reduction co-exist using the highly stratified sulfate-enriched Yarqon estuary as a case study.

Materials and Methods

Study Site

The Yarqon (Figure 1) is the largest coastal river in Israel with length of 27.5 km and a drainage basin area of 1800 km2. As other streams along the Mediterranean coast of Israel, the bottom bathymetry of the downstream lies below sea level, enabling the intrusion of seawater and the formation of highly stratified estuary up to a few kilometers inland. The estuary contains high organic carbon loads from upstream (20–60 mg L-1; Arnon et al., 2015) and lower water mass close to seawater salinity (∼19000 mg Cl-).

FIGURE 1.

Yarqon estuary location map at the Israeli coast of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Sediment Core Sampling

Sediment cores (∼35 cm long, 5 cm in diameter) were collected during August and October 2013 at the Yarqon estuary, 3 km upstream (32° 06.0792′ N; 34° 48.3633′ E), using a gravity corer as described in Antler et al. (2014). The cores were stored in the dark at 4°C and then sliced and treated within 48 h under anaerobic conditions.

Experimental Design

Three incubation Experiments (A, B, and C- described below) were carried out using 1–3 replicates of sediments cores. Treatments parameters are outlined in Table 1. Each of the cores was sliced in the 5–15 cm depth interval under N2 flushing. Methane was measured from the head space using N2 pre-flushed gas tight syringe. Porewater sub-samples for sulfate and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) concentrations and isotopic measurements were extruded using N2 pre-flushed sterile 5 ml syringe (sub-sample of 2 ml).

Table 1.

Description of Experiment A, B, and C with duplicate bottles for each treatment.

| Experiment A | Sediment core collected during August 12th 2013; The goal of the experiment was to determine the effect of different sulfate concentrations on methane production rates, with and without sulfate reduction inhibitor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Sulfate concentration in slurry (mM) | |||

| 100 μl of 13CH4 (99.999%) was added to all slurries | ||||

| No inhibitor | 9 mM | 2 mM | 1 mM | Killed control + 9 mM |

| Sulfate reduction inhibitor | 9 mM + Molybdate | 2 mM + Molybdate | 1 mM + Molybdate | |

| Experiment B | Sediment core collected during October 1st 2013; The goal of the experiment was to determine the effect of inhibitors addition on methane production and effect of sulfate reduction rates and isotopic signature | |||

| 10 mM sulfate without substrate addition in all slurries Inhibition conditions | ||||

| Treatments | No inhibitor addition-control | 20 mM BES | 10 mM Molybdate | |

| Experiment C | Sediment core collected during October 1st 2013; The goal of the experiment was to determine the effect of substrate and the effect of inhibitors addition on methane production and sulfate reduction rates | |||

| Treatment Substrate conditions | 10 mM sulfate in all slurries Inhibition conditions | |||

| 40 mM acetate | No inhibitor | 20 mM BES | Molybdate | Killed control with acetate addition |

| 10 mM lactate | No inhibitor | |||

Experiment A-(Table 1) was conducted on a sediment core from August 2013. The sub-sampled sediment was homogenized and approximately 30 gr of sediment was transferred to N2 pre-flushed 300 ml sterile glass bottles. Sterile and anaerobic 3.5% NaCl omit solutions were pre-prepared with different sulfate concentrations (1, 2, or 9 mM), with or without molybdate (MoO42-) as a sulfate reduction inhibitor (Oremland and Capone, 1988). The range of sulfate concentration and the layer isolated were chosen based on in situ sulfate and methane profiles that show that sulfate reduction and methanogenesis overlap in the Yarqon with sulfate concentration up to 10 mM (Antler et al., 2014). The sediment was mixed with the media at a 1:4 ratio to produce slurry and closed with black butyl rubber stoppers. Three times in sequence, bottles were shaken vigorously for 30 s followed by flushing with a N2 + 300 ppm CO2 mixture for 5 min at the beginning of the experiment. Labeled 13C methane was added to all slurries at a concentration of 100 μmol Lslurry-1. For each treatment duplicates were prepared. Killed control bottles were autoclaved after the bottles were sealed.

Experiment B and C-(Table 1) were conducted on three sediment cores retrieved on October 2013 that were sliced in the depth interval of 10–25 cm depth in an anaerobic hood (Coy Lab-Grass Lake, MI, USA). The sediment slices were homogenized and mixed with sterile and anaerobic medium solutions that were prepared in advance with 3.5% NaCl and 10 mM sulfate, in a 1:4 sediment: medium ratio. One hundred and twenty mililiter sub samples from each slurry were transferred into 300 ml sterile glass bottles and closed with black butyl rubber stoppers inside the anaerobic hood. Three times in sequence, bottles were shaken vigorously for 30 s followed by flushing with a N2 + 300 ppm CO2 mixture for 5 min at the beginning of the experiment. Experiment B was conducted on slurries treated with 10 mM molybdate as a sulfate reduction inhibitor or with 20 mM 2-bromoethanosulfonate (BES; Sigma–Aldrich, Rehovot, Israel) as a methanogenesis inhibitor (Chidthaisong and Conrad, 2000b) or without an inhibitor (as a control). All slurries in Experiment B were not amended with a substrate. Experiment C was conducted on slurries treated with substrate and inhibitors addition. The substrate additions were 7 mM acetate or 7 mM lactate. Killed control bottles were autoclaved after sealing and substrate was added. For each substrate, two bottles were treated with 20 mM of BES or 10 mM molybdate or with no inhibitor addition. Duplicate bottles were made for each treatment.

Analytical Methods

Chemical Analyses

Headspace methane concentrations were measured on a gas chromatograph equipped with a flammable ionization detector (FID) at a precision of 2 μmol CH4 L-1. Sulfate was measured after porewater were filtered with a 0.22 μm filter and diluted by a factor of ∼1:100 (by weight using a Dionex DX500 high pressure liquid chromatograph (HPLC) with an error of 3%. δ13CDIC was measured in ∼0.5 mL of each sample. The sample was transferred into a He-flushed vial containing 50 μl of concentrated H3PO4 that released all DIC to the headspace as CO2. Measurements of the released CO2 was done using a conventional isotopic ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS, DeltaV Advantage, Thermo) with a precision of ±0.1‰, and the results are reported versus the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) standard. DIC concentration was calculated from the IRMS results according to peak height and to a calibration curve (by standard samples prepared from NaHCO3) with an error of ±0.2 mM. The δ13CCH4 values were measured using an IRMS equipped with a PreCon interface after oxidation to CO2. The error between duplicates of this parameter was less than 0.5‰ and the results are reported versus the VPDB standard. For δ34SSO4 analysis, sulfate was precipitated as barium sulfate (barite) using a saturated barium chloride solution (as described in Antler et al., 2014). The barite was then washed with 6N HCl and distilled water. The barite was combusted at 1030°C in a Flash Element Analyzer (EA), and the resulting sulfur dioxide (SO2) was measured by continuous flow on a GS-IRMS (Thermo Finnegan Delta V Plus Godwin Laboratory, University of Cambridge). The error for δ34SSO4 was determined using the standard deviation of the standard NBS 127 at the beginning and the end of each run (∼0.3‰ 1σ). Samples were corrected to NBS 127, IAEA-SO-5 and IAEA-SO-6 standards (20.3, 0.5, and -34.1‰, respectively). The δ34SSO4 values are reported versus Vienna Canyon Diablo Troilite (VCDT). Data analysis of variance (single factor ANOVA) test was conducted on concentration measurements of methane and sulfate to test the variance between the treatments described above with α = 0.05.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) Analyses

Reaction mix for qPCR included the following: 12.5 μl KAPA SYBR Fast Universal Ready mix (KAPA Biosystems, Woburn, MA, USA); 100 nM of each primer, 1 μl template (extracted DNA or plasmid) and DDW to complete to 25 μl. Thermocycling conditions included an initial denaturation step at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s; annealing temperatures as described in Table 2 for 30 s; and 72°C for 30 s. Acquisition was performed at the completion of each cycle, following a short (2 s) step at 78°C to ensure primer dimer denaturation. Melting curves (72–95°C) showed only one peak for all qPCR reactions. PCR for mcrA (methanogens), dsrA (sulfate reducing bacteria), and 16S rRNA genes of archaea and bacteria were preformed based on Wilms et al. (2006) and Yu et al. (2008). Calibration curves for mcrA, dsrA, archaea and bacteria were created by conducting a 10-fold dilution series (∼103–109 copies) of plasmids (constructed as detailed below), containing environmental copies of the relevant genes. For calibration of 16s rRNA genes, genomic DNA from a pure culture of Escherichia coli was used, assuming that the 16S copy number in this genome is 6. Calibration curves had R2 > 0.975, and the slope was between -3.0 and -3.9, corresponding to PCR efficacy of 90–111%. The copy number of mcrA was normalized to archaea copy number and the copy number of dsrA was normalized to bacteria copy number in the same sample. Amplification reactions were carried out in a Rotor-GeneTM 6000 thermocycler (Corbett Life Science, Concorde, NSW, Australia). Primer sequences are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers and annealing temperature based on ∗Wilms et al., 2006 and ∗∗Yu et al., 2008.

| Primer name | Annealing temp | Length (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| dsrA∗ | 5′-ACSCACTGGAAGCACG-3′ | 58°C | 450 |

| 5′-CGGTGMAGYTCRTCCTG-3′ | |||

| mcrA∗ | 5′-GCMATGCARATHGGWATGTC-3′ | 54°C | 350 |

| 5′-TGTGTGAASCCKACDCCACC-3′ | |||

| Archaea∗∗ | 5′-ACGGGGYGCAGCAGGCGCGA-3′ | 48°C | 320 |

| 3′-GTGCTCCCCCGCCAATTCCT-5′ | |||

| Bacteria∗ | 5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′ | 60°C | 270 |

| 3′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG-5′ | |||

Results

Experiment A

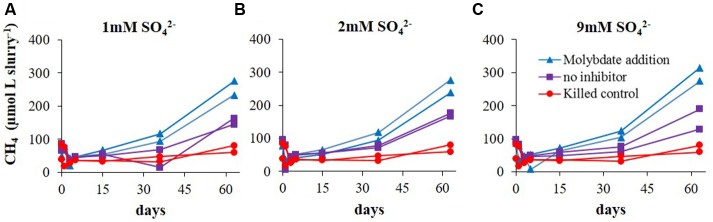

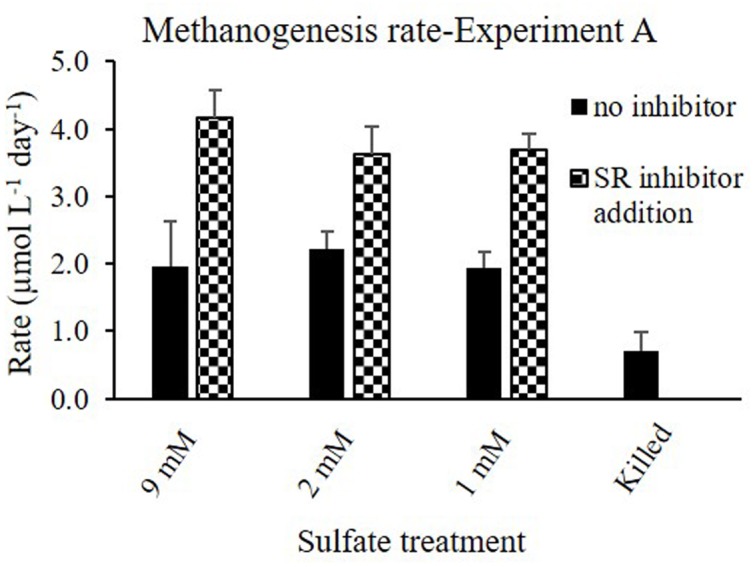

The first set of experiments (Experiment A) aimed to examine the effect of sulfate concentration on the rate of methanogenesis and the lag time for its initiation. Both, methanogenesis rates and the lag time of methanogenesis initiation were similar (40 days) regardless of sulfate concentrations (9, 2, and 1 mM sulfate; Figure 2). In this experiment the effect of sulfate reduction on methanogenesis was tested as well. This was done by molybdate addition, a sulfate reduction inhibitor. In all the non-inhibited slurries, methane concentrations reached ∼170 μmol Lslurry-1, and even slightly higher values with 9 mM sulfate. As expected, when molybdate was added to the slurries, methanogenesis was stimulated and methane concentrations increased up to 250–300 μmol Lslurry-1 in all slurries. In the killed control (with 9 mM sulfate) methane concentrations did not increase throughout the experiment (Figure 2). A comparison between methanogenesis rates in the range of sulfate concentrations with and without sulfate reduction inhibitor is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Experiment A – Evolution of methane concentrations in slurries with (A) 1 mM ; (B) 2 mM ; and (C) 9 mM .

FIGURE 3.

Methanogenesis rates in Experiment A with and without sulfate reduction inhibitor (molybdate) under different sulfate concentrations.

During this experiment sulfate concentrations decreased by 0.1 – 0.3 mM, indicating low reduction rates. DIC concentrations increased by ∼0.9 mM when molybdate was added and by ∼1.0 mM in non-inhibited slurries. This difference is not significant as it is in the range of the standard error. The difference in the δ13CDIC values between the treatments was also not significant, and remained between -16‰ to -18‰. Although 13C labeled methane was added to all slurries (initial concentration of 100 μmol Lslurry-1), 13C enriched DIC was not detected in slurries, indicating that AOM was insignificant in this short time scale experiments, as was shown in marine and lake sediments (Sivan et al., 2014; Bar-Or et al., 2015). Data of this experiment was not shown as it was similar to Experiment B, which was fuller and presented in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Experiment B – Slurries with sediment amended with inhibitors of either sulfate reduction (molybdate) or methanogenesis (BES), control slurries (without inhibitor) and killed control (autoclaved). (A) Sulfate concentration; (B) δ34S of residual ; (C) CH4 concentrations; (D) δ13C-CH4; (E) DIC concentrations and (F) δ13C-DIC. Legend in panel (A) refers to all panels.

Experiment B

The effect of sulfate reduction on methanogenesis was examined by treatment with molybdate; and the effect of methanogenesis on sulfate reduction was examined by treatment with BES (a methanogen inhibitor) in slurries. The results of Experiment B without inhibitors supplementation (Figure 4) were similar to those of Experiment A. Sulfate concentrations in the non-inhibited and BES-treated slurries decreased by a factor of 5–10 relative to molybdate-treated slurries, demonstrating the efficiency of molybdate as an inhibitor of sulfate reduction (Figure 4A). The values of δ34SSO4 increased by 2.3–5.1‰ in non-inhibited slurries and BES-treated slurries, and decreased in slurries treated with molybdate and in the killed controls by 0.4–0.9‰, (Figure 4B).

Methane concentrations increased in all treatments. As expected, the maximum increase was observed in slurries treated with molybdate and the minimum increase was observed in slurries treated with BES and in the non-inhibited slurries (Figure 4C). The initial value of δ13CCH4 in all slurries was approximately -35‰, and decreased throughout the experiment. Maximum depletion was observed in BES-treated slurries (methane production in BES-treated slurries and non-inhibited slurries showed similar rates) and minimum depletion was observed in slurries treated with molybdate, corresponding to methanogenesis rates in the slurries (Figure 4D).

The DIC concentrations were similar in all slurries and increased only by approximately 3 mM (Figure 4E). The initial DIC concentrations were 4.6–5.4 mM in all slurries and the initial δ13CDIC value in all slurries was ∼-12‰. This value slightly decreased during the experiment with a similar trend as δ13CCH4 with maximum depletion in the BES-treated slurries, and minimum depletion in molybdate-treated slurries (Figure 4F).

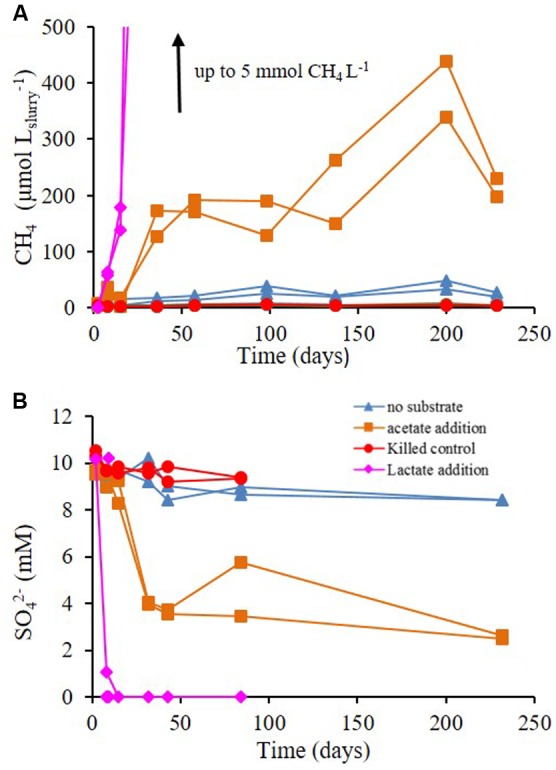

Experiment C

The effect of acetate and lactate supplements on methane production and sulfate reduction rates was examined during Experiment C. These additions stimulated methane production in all slurries. The maximum increase in methane concentration was observed in slurries treated with lactate and in decreasing order with acetate addition, no substrate supplementation and finally killed control (Figure 5A). The most prominent decrease in sulfate during the experiment was in the slurries supplemented with lactate, where sulfate completely depleted within 5 days; followed by slurries supplemented with acetate, and those without substrate supplementation (Figure 5B). The effect of inhibitors and substrates addition on sulfate reduction and methanogenesis rates in Experiments B and C is shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 5.

Experiment C – (A) methane and (B) sulfate concentrations throughout the experiment with no substrate addition, acetate addition, lactate addition and killed control (autoclaved).

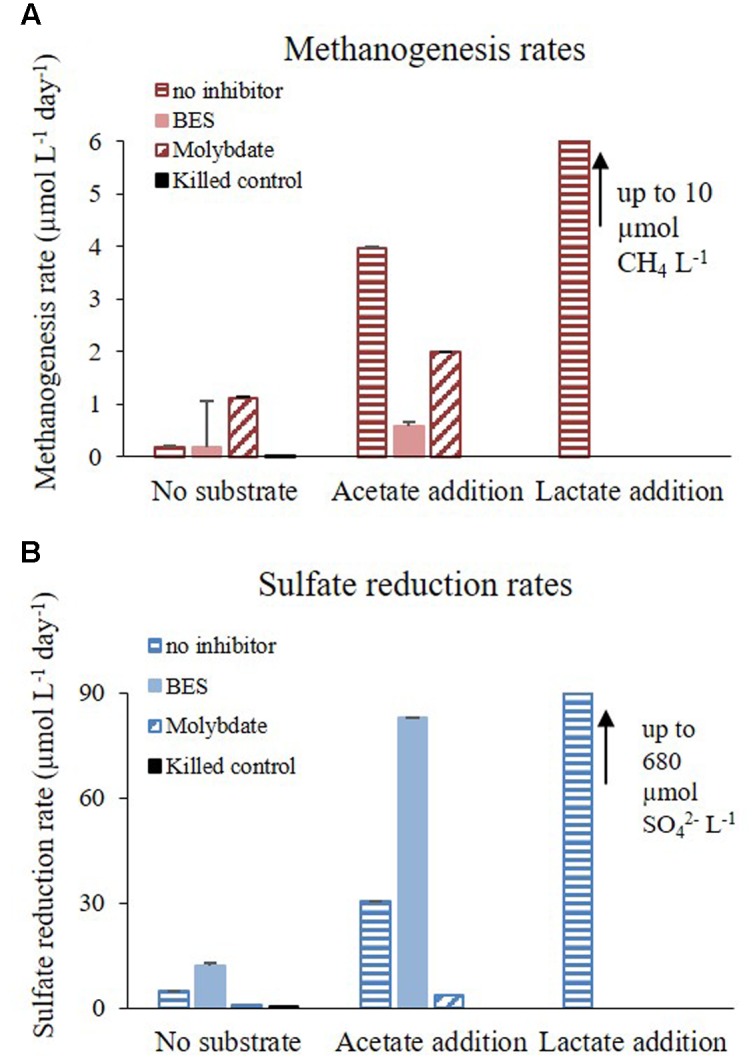

FIGURE 6.

Rates of (A) methanogenesis and (B) sulfate reduction during Experiments B and C treated with inhibitors (BES, molybdate or without inhibitor) and with substrate (acetate, lactate or without substrate addition).

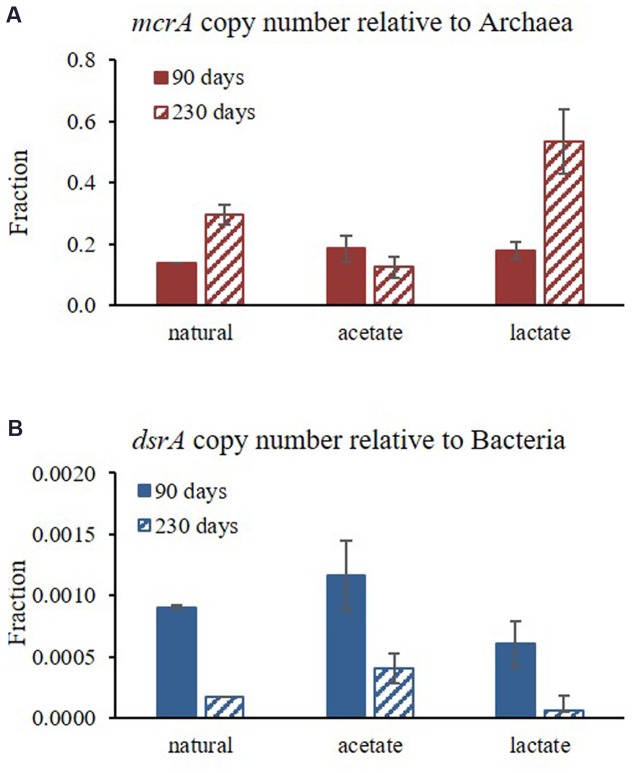

The qPCR results for the abundances of mcrA (normalized to copy number of archaea) and dsrA (normalized to the copy number of bacteria) functional genes at two time points in Experiment C (after 90 and 230 days) are presented in Figure 7. The results show that methanogens (based on mcrA gene) under natural conditions constituted approximately 10% of all archaea, and sulfate reducing bacteria (based on dsrA gene) were approximately 0.1% of all bacteria (Figure 7 and Table 3). In general, sulfate reducing bacteria were more abundant during the first step of the experiment and methanogens became more abundant toward the end of the experiment (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Changes in the relative abundance of (A) mcrA functional gene relative to the copy number of Archaea; and (B) dsrA functional gene relative to the copy number of Bacteria over the course of the experiment at two time points (average of duplicate bottles (each samples in triplicates).

Table 3.

Copies per gram dry sediment of specific genes for each of the duplicate bottles.

| Copies per gr dry sediment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural sediment at t0 | Archaea | Bacteria | Methanogens | Sulfate reducing bacteria | Archaea/Bacteria ratio | |||||

| 2.4 × 108 | 1.0 × 1011 | 3.4 × 107 | 7.6 × 107 | 2.4 × 10-3 | ||||||

| Treatment | 90 days | 230 days | 90 days | 230 days | 90 days | 230 days | 90 days | 230 days | 90 days | 230 days |

| Natural | 7.3 × 108 | 1.7 × 108 | 7.8 × 1011 | 4.7 × 1011 | 1.0 × 108 | 4.4 × 107 | 7.0 × 108 | 8.3 × 107 | 9.3 × 10-4 | 3.6 × 10-4 |

| 6.0 × 108 | 1.5 × 108 | 4.9 × 1011 | 4.2 × 1011 | 8.3 × 107 | 4.9 × 107 | 4.5 × 108 | 7.2 × 107 | 1.2 × 10-3 | 3.6 × 10-4 | |

| Acetate | 9.3 × 108 | 3.7 × 108 | 2.6 × 1012 | 1.5 × 1012 | 2.1 × 108 | 5.8 × 107 | 2.3 × 109 | 7.9 × 108 | 3.6 × 10-4 | 2.5 × 10-4 |

| 4.8 × 108 | 1.8 × 108 | 6.8 × 1011 | 8.6 × 1011 | 6.8 × 107 | 1.6 × 107 | 9.9 × 108 | 2.4 × 108 | 7.1 × 10-4 | 2.0 × 10-4 | |

| Lactate | 4.6 × 109 | 1.9 × 109 | 4.8 × 1012 | 2.7 × 1012 | 9.4 × 108 | 8.3 × 108 | 3.8 × 109 | 1.5 × 108 | 9.6 × 10-4 | 7.2 × 10-4 |

| 8.1 × 109 | 2.7 × 109 | 7.0 × 1012 | 4.7 × 1012 | 1.2 × 109 | 1.8 × 109 | 2.9 × 109 | 3.1 × 108 | 1.2 × 10-3 | 5.8 × 10-4 | |

Discussion

Sulfate penetration into the methane production zone was already observed in diverse environments. For example, in continental margin sediments (Treude et al., 2014), in the gassy sediments of Eckernforde Bay in the German Baltic (Treude et al., 2005), in littoral Baltic Sea sediments (Thang et al., 2013), in the saline coastal sediments of Lake Grevelingen in the Netherlands (Egger et al., 2016), in the sediments of the Black Sea (Knab et al., 2009) and in salt marsh sediments (Parkes et al., 2012). However, couplings between sulfate concentrations, sulfate reduction rates and methanogenesis rates have not been fully examined in estuarine sediments. Previous porewater data from sediments of the Yarqon estuary documented a combination of a high organic matter loading and seawater sulfate concentrations, triggering relatively high rates of sulfate reduction (6.05 × 10-4 mol L-1 day-1) with maximum values at the upper 5 cm sediment depth. These were relatively high rates compared to other marine or saline estuarine environments (Eliani-Russak et al., 2013). Methane accumulated to above 300 μmol L-1 in the sulfate reduction zone when sulfate concentrations were above 3 mM at sediment depth of ∼10 cm. In addition, sulfate was not completely exhausted until 20 cm below surface, penetrating into the methanogenesis zone. The isotopic signature of oxygen (δ18OSO4) versus sulfur (δ34SSO4) in dissolved sulfate profiles indicated that in the Yarqon estuary sediment (during May 2010), AOM is likely the main sulfate reduction process (Antler et al., 2014). In this study we used sediment cores from the saline Yarqon estuary at the zone identified as containing both processes.

Sulfate Concentration Effect

The experiments in this research were conducted under a sulfate concentration range of 1–10 mM. This specific concentration range was chosen for several reasons: (1) In situ evidences show that sulfate reduction and methanogenesis overlap in the Yarqon and that sulfate concentrations in this depth can reach 10 mM (Antler et al., 2014); (2) Different sulfate and substrate concentrations cause different reduction rates in the sediment; (3) Flood events cause the salinity gradient to retreat toward seashore, which changes the sulfate concentration gradient.

Methanogens activity is not affected by sulfate concentrations, as was shown in pure cultures (King, 1984). Nevertheless, in different sedimentary systems, the competition with sulfate reducing bacteria for labile substrate controls methanogenesis, since sulfate reducing bacteria outcompete methanogens for substrate uptake. Elevated sulfate concentration will cause an enhancement in sulfate reduction rates and therefore a decrease in methanogenesis, and vise versa – low sulfate concentrations will decrease sulfate reduction rates and will enhance methanogenesis (Mountfort et al., 1980; Lovley et al., 1982; Lovley and Klug, 1983). Here we show that even at elevated sulfate concentrations in sedimentary systems, sulfate reduction and methanogenesis co-exist, and the rates of sulfate reduction control methanogenesis rates. The negligible effect of sulfate concentration on the methanogenesis rates in slurries indicates that the concentration itself is not the direct controlling factor of methanogenesis. The amendments of the slurries with sulfate at various concentrations (Experiment A; Figure 2) did not influence sulfate reduction rates either, indicating that this system is probably substrate depleted. Furthermore, supplementation of molybdate, which lowered the rates of sulfate reduction, enhanced methane production in all slurries (Figure 3). Therefore, we suggest that the competition between methanogens and sulfate reducing bacteria for a common substrate is the main factor controlling the rates and onset of methanogenesis.

Isotopic Effect

Microorganisms tend to discriminate against the heavy isotope, leaving the product isotopically enriched in the light isotope and the residual pool in the heavy isotope. Sulfate reduction and methanogenesis processes have large isotope fractionation effect, and thus related isotope measurements may be more distinct and sensitive than the measurement of concentration changes (e.g., Sivan et al., 2014). Dissimilatory sulfate reduction is characterized by large isotopic fractionation (up to 72‰) with the light isotope favored in the H2S product (Kaplan and Rittenberg, 1964; Canfield, 2001; Wortmann et al., 2001; Sim et al., 2011). In experiment B there was a significant increase in δ34SSO4 in the slurries without inhibitor and in the slurries with the BES addition. A small decrease was observed in the killed control and in the experiment with molybdate addition (Figure 4B). This indicates active sulfate reduction in the slurries without inhibitor and with the BES addition (the change in sulfate concentration is small during the course of the experiment as it is less sensitive). The decrease in δ34SSO4 in the killed control and in the experiment with molybdate supplementation toward the end of experiment can be attributed to anaerobic abiotic oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds (Balci et al., 2007). Furthermore, sulfate reduction was enhanced when methanogenesis was inhibited (by BES) (Figure 6B) and methanogenesis rate was enhanced when sulfate reduction was inhibited (by molybdate) (Figure 6A). It seems therefore that the enrichment of 34S of residual sulfate is correlated with the rate of sulfate reduction, as shown previously (Kaplan and Rittenberg, 1964; Habicht and Canfield, 1997; Sim et al., 2011).

During methanogenesis the carbon fractionation against 13C is about 25–90‰, producing very light methane with δ13CCH4 of -50 to -100‰ and enriched δ13CDIC (e.g., Ferry, 1992; Whiticar, 1999; Gelwicks et al., 1994). The fractionation varies among the different pathways of methanogenesis. In hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, CO2 is reduced by H2, the fractionation is slightly larger than the fractionation of acetoclastic methanogenesis and can exceed 55‰. In acetoclastic methanogenesis methane is derived from the methyl group of acetate, the fractionation is slightly lower and ranges between 40 and 60‰ (Whiticar et al., 1986; Whiticar, 1999).

Slurries treated with BES and non-inhibited slurries showed similar methanogenesis rates, based on methane concentrations measurements. However, the isotope measurements, which are often more sensitive, showed significant stronger depletion of δ13CCH4 in slurries treated with BES relative to non-inhibited slurries (Figures 4D,F). Valentine et al. (2004) and Penning et al. (2005) showed that during hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis high levels of H2 were correlated with low fractionation in carbon, and low levels of H2 were correlated with higher fractionation. The authors hypothesized that this difference is controlled by the extent of the enzymatic reversibility which, is controlled by the Gibbs free energy of catabolism, similar to dissimilatory sulfate reduction (Kaplan and Rittenberg, 1964; Habicht and Canfield, 1997). BES is an analog of coenzyme M found in all methanogens and is a specific inhibitor for methanogens (Chidthaisong and Conrad, 2000b). Since coenzyme M is involved in the rate limiting step in methane production (Scheller et al., 2013), we propose that BES addition stops the reversibility of methanogenesis or acts similarly to low levels of H2 or reduced Gibbs free energy (less negative) and therefore the fractionation is larger in the BES treated slurries.

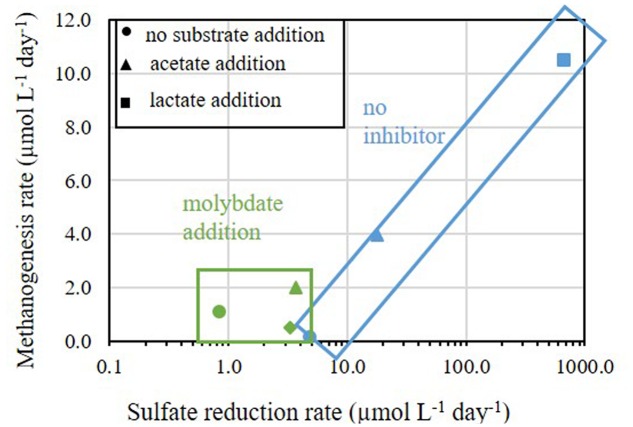

Substrate Supplementation Effect

Methanogenesis and sulfate reduction rates calculated from Experiment C show that the supplementation of lactate and acetate had a significant effect on the rate of the processes (Figure 6). Similarly to Experiment A, when a sulfate reduction inhibitor (molybdate) was added methanogenesis was enhanced, with the exception of acetate supplementation (Figure 6A). The rates of sulfate reduction and methanogenesis increased by one order of magnitude as a result of acetate supplementation, and with lactate both rates increased by two orders of magnitude (Figure 8). Although the effect of a non-competitive substrate was not examined in this research, the results show that competitive labile organic matter had similar effects on the rates of sulfate reduction and methanogenesis. This indicates that at a high organic load, sulfate reduction and methanogenesis can co-exist and share ambient electron donors (Ozuolmez et al., 2015; Egger et al., 2016). The effect of labile organic matter on methanogenesis rate was shown also in a recent study from a shallow sediment in the Peruvian margins having co-existence of methanogenesis and sulfate reduction with 1–2 order of magnitudes difference in rates, which remain steady along the organic carbon concentration gradient (Maltby et al., 2015).

FIGURE 8.

Methanogenesis rates versus sulfate reduction rates in Experiments B and C. The rates of samples without addition of inhibitors are marked in blue symbols and rectangle and the rates of samples treated with molybdate are marked in green symbols and rectangle.

Nevertheless, when considering the absolute rates, sulfate reduction was the favorable process over methanogenesis in slurries with substrate supplementation. This advantage could be attributed to thermodynamic preference of sulfate reduction compared to methanogenesis (Lovley and Goodwin, 1988) and the population composition under natural conditions, in which sulfate reducing bacteria represented 10% of the total microbial community while methanogens represented less than 0.01% (Table 3). This is shown in Figure 8, which summarizes the effect of substrate addition on the rates of sulfate reduction and methanogenesis. When lactate and acetate were added both rates were enhanced by two and one orders of magnitude, respectively. Nevertheless, a two orders of magnitude difference between sulfate reduction and methanogenesis remained. Thus, it appears that the competition over substrate controls the intensity of methanogenesis in estuarine sediments (Figure 8).

According to the microbial population analysis, sulfate reducing bacteria were dominant at the beginning of Experiment B, whereas over the course of the experiment methanogen abundance increased, even though sulfate concentrations was still high with acetate supplementation (7 mM; Figure 7). In addition, lactate addition stimulated rapid sulfate reduction, which may have caused sulfate reducers to be sulfate-limited and enabled methanogens to strengthen. This suggests that sulfate reducing bacteria have an initial advantage for electron donor uptake; however, methanogens can also grow under elevated sulfate concentration and sulfate reduction rates. This observation strengthens our hypothesis that sulfate reduction and methanogenesis can co-exist and initial sulfate concentrations in the sediment do not control methane production initiation and intensity. The rate and initiation depth of methanogenesis is probably more strongly affected by the competition and the quantitative advantage of the sulfate reducing bacteria over the methanogens, as well as their stronger affinity for substrate uptake and the fact that sulfate reducing bacteria are not sulfate limited in these sediments (Figure 7).

Sulfate reducing bacteria have higher affinity to hydrogen and acetate than methanogens (Oremland and Polcin, 1982). However, co-existence of sulfate reduction and methanogenesis was shown under substrate limited conditions and following substrate supplementation, without dependence on sulfate concentration in the Yarqon sediments. The qPCR results show that acetate supplementation considerably enhanced the abundance of sulfate reducing bacteria and may indicate that the dominant electron donor in this process in the sediments is acetate. Lactate supplementation enhanced methanogens considerably, probably due to hydrogen production during lactate degradation and due to quick depletion in sulfate concentrations in the slurries treated with lactate.

Summary

This study evaluated the regulatory effects of sulfate concentrations and microbial sulfate reduction on methanogenesis in the SMTZ of estuarine sediments using the Yarqon river estuary as a case study. The results show that: (a) Sulfate concentrations do not limit the onset and methanogenesis rates in the Yarqon estuarine sediments, even when sulfate concentrations are as high as 10 mM; (b) The main factors controlling methanogenesis initiation and intensity are sulfate reduction rate and substrate availability and; (c) Methanogenesis can co-exist with sulfate reduction in a large range of sulfate reduction rates (5–700 μmol L-1 day-1) that are controlled by substrate and inhibitor additions. Sulfate reducing bacteria have a distinct favorable substrate utilization, as apparent by two orders of magnitude higher reduction rates compared to methanogenesis rates. The qPCR analysis results strengthen our geochemical data and show a shift in time from an initial dominance of sulfate reducing bacteria to a growth of the methanogen community toward the end of the experiment. Although estuarine sediments represent only 0.7% of the total marine sediments area, they contribute 7–10% of oceanic emissions of carbon to the atmosphere (Bange et al., 1994; Abril and Iversen, 2002). Thus, studying methane production controls and specifically the co-existence of the two main carbon sink processes in estuarine sediments is globally important. The results from the Yarqon estuary may be significant to other estuarine environments that show co-existence of methanogenesis and sulfate reduction.

Author Contributions

MS-A and OS designed the experiments, MS-A and HV performed the work, GA measured the sulfur isotopes. MS-A, ZR, BH, GA, WE, and OS analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. D. Pargament and P. Rubinzaft from the Yarqon River Authority for their technical support in the field. We are thankful to E. Eliani-Russak for technical help in the lab. We are thankful to A. Turchyn for sulfur isotopes measurements, interpretation and for the internal review. We are thankful also to Prof. J. Ganor for the use in the HPLC. This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (#643/12).

References

- Abril G., Iversen N. (2002). Methane dynamics in a shallow non-tidal estuary (Randers Fjord, Denmark). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 230 171–181. 10.3354/meps230171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antler G., Turchyn A. V., Herut B., Davies A., Rennie V. C., Sivan O. (2014). Sulfur and oxygen isotope tracing of sulfate driven anaerobic methane oxidation in estuarine sediments. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 142 4–11. 10.1016/j.ecss.2014.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer D. (2007). Methane hydrate stability and anthropogenic climate change. Biogeosciences 4 993–1057. 10.5194/bgd-4-993-2007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon S., Avni N., Gafny S. (2015). Nutrient uptake and macroinvertebrate community structure in a highly regulated Mediterranean stream receiving treated wastewater. Aquat. Sci. 77 623–637. 10.1007/s00027-015-0407-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balci N., Shanks W. C., Mayer B., Mandernack K. W. (2007). Oxygen and sulfur isotope systematics of sulfate produced by bacterial and abiotic oxidation of pyrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71 3796–3811. 10.1016/j.gca.2007.04.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bange H. W., Bartell U., Rapsomanikis S., Andreae M. O. (1994). Methane in the Baltic and North Seas and a reassessment of the marine emissions of methane. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 8 465–480. 10.1029/94GB02181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Or I., Ben-Dov E., Kushmaro A., Eckert W., Sivan O. (2015). Methane-related changes in prokaryotes along geochemical profiles in sediments of Lake Kinneret (Israel). Biogeosciences 12 2847–2860. 10.5194/bg-12-2847-2015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borowski W. S., Cagatay N., Ternois Y., Paull C. K. (2000). “Data report: carbon isotopic composition of dissolved CO2 CO2 gas, and methane, Blake-Bahama Ridge and northeast Bermuda Rise, ODP Leg 172” in Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results Vol. 172 eds Keigwin L. D., Rio D. (College Station, TX: Ocean Drilling Program; ), 1–16. 10.1021/es5006797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borowski W. S., Paull C. K., Ussler W. (1996). Marine pore-water sulfate profiles indicate in situ methane flux from underlying gas hydrate. Geology 24 655–658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D. E. (2001). Isotope fractionation by natural populations of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65 1117–1124. 10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00584-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chidthaisong A., Conrad R. (2000a). Turnover of glucose and acetate coupled to reduction of nitrate, ferric iron and sulfate and to methanogenesis in anoxic rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 31 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidthaisong A., Conrad R. (2000b). Specificity of chloroform, 2-bromoethanesulfonate and fluoroacetate to inhibit methanogenesis and other anaerobic processes in anoxic rice field soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32 977–988. 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00006-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R. (1999). Contribution of hydrogen to methane production and control of hydrogen concentrations in methanogenic soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 28 193–202. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1999.tb00575.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dale A. W., Regnier P., Knab N., Jørgensen B. B., Van Cappellen P. (2008). Anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) in marine sediments from the Skagerrak (Denmark): II. Reaction-transport modeling. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72 2880–2894. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01526.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Lenstra W., Jong D., Meysman F. J. R., Sapart C. J., van der Veen C., et al. (2016). Rapid sediment accumulation results in high methane effluxes from coastal sediments. PLoS ONE 11:e0161609 10.1371/journal.pone.0161609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliani-Russak E., Herut B., Sivan O. (2013). The role of highly sratified nutrient-rich small estuaries as a source of dissolved inorganic nitrogen to coastal seawater, the Qishon (SE Mediterranean) case. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 71 250–258. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry J. G. (1992). Methane from acetate. J. Bacteriol. 174 5489–5495. 10.1128/jb.174.17.5489-5495.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froelich P., Klinkhammer G., Bender M. A. A., Luedtke N., Heath G. R., Cullen D., et al. (1979). Early oxidation of organic matter in pelagic sediments of the eastern equatorial Atlantic: suboxic diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 43 1075–1090. 10.1016/0016-7037(79)90095-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gelwicks J. T., Risatti J. B., Hayes J. M. (1994). Carbon isotope effects associated with aceticlastic methanogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60 467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habicht K. S., Canfield D. E. (1997). Sulfur isotope fractionation during bacterial sulfate reduction in organic-rich sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61 5351–5361. 10.1016/S0016-7037(97)00311-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan I. R., Rittenberg S. C. (1964). Microbiological fractionation of sulphur isotopes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 34 195–212. 10.1099/00221287-34-2-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene R. P., Oremland R. S., Catena A., Miller L. G., Capone D. G. (1986). Metabolism of reduced methylated sulfur compounds in anaerobic sediments and by a pure culture of an estuarine methanogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52 1037–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G. M. (1984). Utilization of hydrogen, acetate, and “noncompetitive”; substrates by methanogenic bacteria in marine sediments. Geomicrobiol. J. 3 275–306. 10.1080/01490458409377807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knab N. J., Cragg B. A., Hornibrook E. R. C., Holmkvist L., Pancost R. D., Borowski C., et al. (2009). Regulation of anaerobic methane oxidation in sediments of the Black Sea. Biogeosciences 6 1505–1518. 10.5194/bg-6-1505-2009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knab N. J., Dale A. W., Lettmann K., Fossing H., Jørgensen B. B. (2008). Thermodynamic and kinetic control on anaerobic oxidation of methane in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72 3746–3757. 10.1016/j.gca.2008.05.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knittel K., Boetius A. (2009). Anaerobic oxidation of methane: progress with an unknown process. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63 311–334. 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster I., Rinzema A., De Vegt A., Lettinga G. (1986). Sulfide inhibition of the methanogenic activity of granular sludge at various pH-levels. Water Res. 20 1561–1567. 10.1016/0043-1354(86)90121-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R., Dwyer D. F., Klug M. J. (1982). Kinetic analysis of competition between sulfate reducers and methanogens for hydrogen in sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43 1373–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R., Goodwin S. (1988). Hydrogen concentrations as an indicator of the predominant terminal electron-accepting reactions in aquatic sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 52 2993–3003. 10.1016/0016-7037(88)90163-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R., Klug M. J. (1983). Sulfate reducers can outcompete methanogens at freshwater sulfate concentrations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45 187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R., Phillips E. J. (1988). Novel mode of microbial energy metabolism: organic carbon oxidation coupled to dissimilatory reduction of iron or manganese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54 1472–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltby J., Sommer S., Dale A. W., Treude T. (2015). Microbial methanogenesis in the sulfate-reducing zone of surface sediments traversing the Peruvian margin. Biogeosciences 12 14869–14910. 10.5194/bgd-12-14869-2015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mountfort D. O., Asher R. A. (1981). Role of sulfate reduction versus methanogenesis in terminal carbon flow in polluted intertidal sediment of waimea inlet, Nelson, New Zealand. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 42 252–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountfort D. O., Asher R. A., Mays E. L., Tiedje J. M. (1980). Carbon and electron flow in mud and sandflat intertidal sediments at delaware inlet, nelson, new zealand. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 39 686–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oremland R. S., Capone D. G. (1988). “Use of “specific” inhibitors in biogeochemistry and microbial ecology,” in Advances in Microbial Ecology (Anonymous), ed. Marshall K. C. (Berlin: Springer; ), 285–383. [Google Scholar]

- Oremland R. S., Polcin S. (1982). Methanogenesis and sulfate reduction: competitive and noncompetitive substrates in estuarine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 44 1270–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oremland R. S., Taylor B. F. (1978). Sulfate reduction and methanogenesis in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 42 209–214. 10.1016/0016-7037(78)90133-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozuolmez D., Na H., Lever M. A., Kjeldsen K. U., Jørgensen B. B., Plugge C. M. (2015). Methanogenic archaea and sulfate reducing bacteria co-cultured on acetate: teamwork or coexistence? Front. Microbiol. 6:492 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes R. J., Brock F., Banning N., Hornibrook E. R., Roussel E. G., Weightman A. J., et al. (2012). Changes in methanogenic substrate utilization and communities with depth in a salt-marsh, creek sediment in southern England. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 96 170–178. 10.1016/j.ecss.2011.10.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penning H., Plugge C. M., Galand P. E., Conrad R. (2005). Variation of carbon isotope fractionation in hydrogenotrophic methanogenic microbial cultures and environmental samples at different energy status. Glob. Change Biol. 11 2103–2113. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller S., Goenrich M., Thauer R. K., Jaun B. (2013). Methyl-coenzyme M reductase from methanogenic archaea: isotope effects on the formation and anaerobic oxidation of methane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 14975–14984. 10.1021/ja406485z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schink B. (1997). Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61 262–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönheit P., Kristjansson J. K., Thauer R. K. (1982). Kinetic mechanism for the ability of sulfate reducers to out-compete methanogens for acetate. Arch. Microbiol. 132 285–288. 10.1007/BF00407967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sim M. S., Bosak T., Ono S. (2011). Large sulfur isotope fractionation does not require disproportionation. Science 333 74–77. 10.1126/science.1205103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivan O., Antler G., Turchyn A. V., Marlow J. J., Orphan V. J. (2014). Iron oxides stimulate sulfate-driven anaerobic methane oxidation in seeps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 E4139–E4147. 10.1073/pnas.1412269111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumm W., Morgan J. J. (1996). Aquatic Chemistry: Chemical Equilibria and Rates in Natural Waters, 3rd Edn Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Thang N. M., Brüchert V., Formolo M., Wegener G., Ginters L., Jørgensen B. B., et al. (2013). The impact of sediment and carbon fluxes on the biogeochemistry of methane and sulfur in littoral Baltic Sea sediments (Himmerfjärden. Sweden). Estuaries Coasts 36 98–115. 10.1007/s12237-012-9557-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thauer R. K., Jungermann K., Decker K. (1977). Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 41 100–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treude T., Krause S., Maltby J., Dale A. W., Coffin R., Hamdan L. J. (2014). Sulfate reduction and methane oxidation activity below the sulfate-methane transition zone in Alaskan Beaufort Sea continental margin sediments: implications for deep sulfur cycling. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 144 217–237. 10.1016/j.gca.2014.08.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treude T., Krüger M., Boetius A., Jørgensen B. B. (2005). Environmental control on anaerobic oxidation of methane in the gassy sediments of Eckernförde Bay (German Baltic). Limnol. Oceanogr. 50 1771–1786. 10.4319/lo.2005.50.6.1771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine D. L., Chidthaisong A., Rice A., Reeburgh W. S., Tyler S. C. (2004). Carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation by moderately thermophilic methanogens. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 68 1571–1590. 10.1016/j.gca.2003.10.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine D. L., Reeburgh W. S. (2000). New perspectives on anaerobic methane oxidation. Environ. Microbiol. 2 477–484. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00135.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward D. M., Winfrey M. R. (1985). Interactions between methanogenic and sulfate-reducing bacteria in sediments. Adv. Aquat. Microbiol. 3 141–179. [Google Scholar]

- Whiticar M. J. (1999). Carbon and hydrogen isotope systematics of bacterial formation and oxidation of methane. Chem. Geol. 161 291–314. 10.1016/S0009-2541(99)00092-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiticar M. J., Faber E., Schoell M. (1986). Biogenic methane formation in marine and freshwater environments: CO2 reduction vs. acetate fermentation—Isotope evidence. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 50 693–709. 10.1016/0016-7037(86)90346-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilms R., Sass H., Kopke B., Koster J., Cypionka H., Engelen B. (2006). Specific bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic communities in tidal-flat sediments along a vertical profile of several meters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 2756–2764. 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2756-2764.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann U. G., Bernasconi S. M., Böttcher M. E. (2001). Hypersulfidic deep biosphere indicates extreme sulfur isotope fractionation during single-step microbial sulfate reduction. Geology 29 647–650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Garcia-Gonzalez R., Schanbacher F. L., Morrison M. (2008). Evaluations of different hypervariable regions of archaeal 16S rRNA genes in profiling of methanogens by Archaea-specific PCR and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 889–893. 10.1128/AEM.00684-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]