Abstract

Molecular motors are enzymes that convert chemical potential energy into controlled kinetic energy for mechanical work inside cells. Understanding the biophysics of these motors is essential for appreciating life as well as apprehending diseases that arise from motor malfunction. This review focuses on kinesin motor enzymology with special emphasis on the literature that reports the chemistry, structure and physics of several different kinesin superfamily members.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12551-014-0150-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Molecular motors, Kinesin motor enzymology, Kinesin superfamily, Chemical models, Enzymes

Introduction

Molecular motors are enzymes that convert chemical potential energy into controlled kinetic energy for mechanical work (i.e., motion or movement) inside cells. These biological motors come in a variety of flavors, including cytoskeletal motors, rotary motors, nucleic acid motors, protein synthesis and translocation machinery, and dynamic biopolymers. Each motor is designed to perform various tasks inside cells, such as intracellular transport, signal transduction, oxidative phosphorylation, cell motility, nucleic acid translocation, nucleic acid synthesis, endocytosis, protein synthesis, protein translocation across membranes, and cell division. Understanding the chemistry, structure, and physics of these biological motors is essential for appreciating life, as well as for apprehending diseases that arise from malfunction of these motors.

Since the discovery of the first force-generating, microtubule-dependent ATPase that drives fast axonal transport in neurons (Brady 1985; Vale et al. 1985), a wealth of research has focused on characterizing the structure and function of various members of the kinesin superfamily. These motors convert the free energy of nucleoside 5′-triphosphate hydrolysis (typically ATP) into directed mechanical motion during their interaction with a microtubule track. Most kinesins contain: (1) a catalytic domain (also known as a motor or head domain) responsible for nucleotide catalysis, microtubule binding, and force production, (2) a central α-helical stalk domain involved in coiled–coil interactions to organize the motor into higher order oligomers (e.g., dimers, tetramers), and (3) a tail domain responsible for various subfamily specific functions [e.g., light chain binding domain for kinesin-1 (Hackney 2007), DNA binding for kinesin-10 (Vanneste et al. 2011), ATP-independent microtubule binding domain for kinesin-8 (Weaver et al. 2011) and kinesin-14 (Karabay and Walker 1999)]. Several reviews have been written that summarize the various features of the kinesin superfamily (Hirokawa and Takemura 2004; Marx et al. 2009; Sack et al. 1999; Vale and Fletterick 1997).

Studying the biophysics of molecular motors has been the focus of many laboratories for decades. The fundamental understanding of enzyme biochemistry, structure, and (particularly for motors) mechanics has been investigated, yet networking the results from these scientific disciplines into a coherent model is often a difficult task. This review focuses on kinesin enzymology with special emphasis on the literature that reports the chemistry, structure and physics of several different kinesin molecular motors. In the first section, I summarize the biochemistry of kinesins, with a focus on the types of kinetic and thermodynamic experiments that researchers have used to study these motors. In this section I also discuss how the interpretation of these results lead to a chemical model for how kinesins catalyze nucleotide hydrolysis and how their partner filaments (microtubules) stimulate their ATPase cycle. In the second section, I provide a detailed summary of the current knowledge of kinesin structure, highlighting the conserved and divergent structural characteristics among the kinesin superfamily, as well as recent structures that have provided much insight into the function of molecular motors. In the third section, I describe the physics of kinesin motors, focusing on the movements and mechanics that are driven by the biochemical reactions in kinesin enzymes for force generation. A dominant feature of this section is the connection of biochemical free energies with the work performed by the motors. In the fourth and final section, several conclusions and future directions for the study of molecular motors are presented.

Chemistry

Although the kinesin superfamily consists of 14–17 different subfamilies with several individual members per subfamily (Dagenbach and Endow 2004; Lawrence et al. 2004; Miki et al. 2005; Wickstead et al. 2010), only a select few have been studied extensively using a combination of biophysical, biochemical, and structural methodologies. Based on a series of elegant kinetic, thermodynamic, and structural studies, ATPase mechanisms of truncated, recombinant monomeric (Fig. 1a) and dimeric (Fig. 1b) kinesin motors have been defined (note: the minimal mechanisms presented here are simplified in order to highlight the dominant steps in the cycle and for the purpose of comparing many different members of the superfamily; Tables 1 and 2). For monomeric kinesins, the minimal mechanism consists of four consecutive biochemical reactions [ATP binding, ATP hydrolysis, inorganic phosphate (H2PO4 -; Pi) release, and ADP release]. These four reactions can occur in either the microtubule-bound or unbound state. Depending on the family member, the motor affinity for the microtubule varies with the nucleotide state at the kinesin active site (e.g., kinesin-1 binds the microtubule tightly in the nucleotide-free/apo/rigor, ATP-like, and ADP⋅Pi-like states, but binds the microtubule weakly in the ADP state). Therefore, the detachment/dissociation and attachment/association rate constants define the four equilibrium constants at each nucleotide state in the cycle (K d,A = nucleotide-free, K d,B = ATP-like, K d,C = ADP⋅Pi-like, K d,D = ADP). The ATP-like and ADP⋅Pi-like states are typically achieved with nucleotide and Pi analogs, respectively (e.g., AMPPNP, AMPPCP, ATPγS as non-hydrolyzable or slowly hydrolyzable ATP analogs, and ADP with BeFx, AlFx, VO4 -, SO4 - as ADP⋅Pi analogs). These nucleotide states have revealed structural details for a variety of different ATPases, including kinesins (Table 3), myosins (Coureux et al. 2004; Gulick et al. 1997; Menetrey et al. 2008; Smith and Rayment 1996), helicases (Bernstein et al. 2003; Halbach et al. 2012; Luo et al. 2008; Schutz et al. 2010; Xiol et al. 2014), AAA+ motors (Schmidt et al. 2012; Stinson et al. 2013; Yamada et al. 2001), and RecA (Datta et al. 2003; Rajan and Bell 2004).

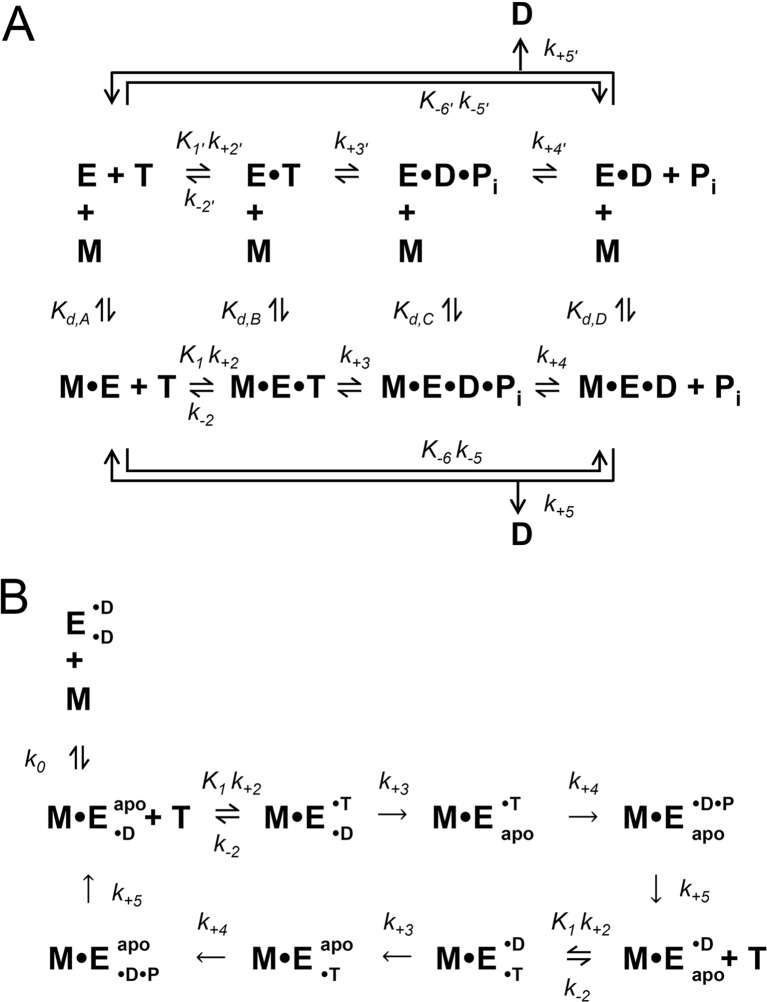

Fig. 1.

Minimal ATPase mechanisms for monomeric and dimeric kinesins. Monomeric (a) and dimeric (b) kinesin ATPase mechanisms are shown. E kinesin, M microtubule, T ATP substrate, D ADP product, P i inorganic phosphate product, apo nucleotide-free/rigor. For dimeric kinesins that have two inter-molecularly regulated active sites, each site is depicted as either a superscript or subscript (for example: E• ADP• ADP indicates tha3 both sites of the dimeric kinesin (E) are bound to ADP)

Table 1.

Comparison of rate and equilibrium constants for truncated monomeric kinesins in published studiesa

| Constant (units) | Reaction | Kinesin-1 | Kinesin-5 | Kinesin-7 | Kinesin-10 | Kinesin-13 | Kinesin-14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hs/BtKHC1-3 | DmKHC4,5 | HsEg56-8 | XlCENP-E9 | DmNOD10,11 | MCAK12 | DmNCD13 | ScKar314,15 | ||

| K 1′ k +2′ (μΜ-1 s-1) | ATP Binding | 300-400 | ND | 0.08 ± 0.01 | ND | 13.8 ± 0.6 | ND | ND | ND |

| k +2′ (s-1) | Isomerization | 170 ± 30 | ND | 0.5-1.2 | ND | 1800 ± 500 | ND | ND | ND |

| k -2′ (s-1) | ATP release | <1 | ND | <0.01 | ND | 5 ± 1 | ND | ND | ND |

| k +3′ (s-1) | Hydrolysis | 7 | ND | >10 | ND | 0.016 ± 0.002 | ND | ND | ND |

| k +4′ (s-1) | Pi release | >0.1 | ND | >10 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| k +5′ (s-1) | ADP release | 0.003 | 0.025 | 0.02 ± 0.001 | ND | 0.23 ± 0.004 | ND | 0.003 ± 0.0006 | 0.006 ± 0.0004 |

| K -6′ k -5′ (μΜ-1 s-1) | ADP binding | 333 | ND | 0.07 ± 0.01 | ND | 19.7 ± 0.4 | ND | ND | ND |

| k -5′ (s-1) | Isomerization | >300 | ND | 0.6-1.0 | ND | 1400 ± 220 | ND | ND | ND |

| K 1 k +2 (μΜ-1 s-1) | ATP binding | 19 ± 3 | 20 ± 5 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | ND | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| k +2 (s-1) | isomerization | >800 | 565 ± 50 | 21.2 ± 1.3 | 28.7 ± 3.9 | 900 ± 120 | ND | >400 | 500 ± 75 |

| k -2 (s-1) | ATP release | 105 ± 11 | 113 ± 60 | <1 | 123 ± 51 | 0.02 ± 0.004 | ND | 7 ± 7 | 50 |

| k +3 (s-1) | Hydrolysis | ND | >300 | 10.2 ± 0.7 | ND | ND | ND | 11.0 ± 2.3 | 70 ± 25 |

| k +4 (s-1) | Pi release | 92 ± 1 | ND | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 11.4 ± 0.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| k +5 (s-1) | ADP release | 300 | 303 ± 23 | 43.3 ± 0.2 | 193 ± 35 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | ND | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.01 |

| K -6 k -5 (μΜ-1 s-1) | ADP binding | 3.3 | 11 ± 1 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 10.6 ± 0.4 | ND | 0.6 ± 0.04 | 1.1 ± 0.01 |

| k -5 (s-1) | Isomerization | >300 | ND | >300 | ND | 760 ± 120 | ND | >100 | >100 |

| k cat (s-1 site-1) | Basal ATPase | 0.005 ± 0.0004 | ND | 0.02 ± 0.003 | ND | 0.001 ± 0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| K m,ATP (μΜ) | ND | ND | 0.17 ± 0.03 | ND | 14.1 ± 2.6 | ND | ND | ND | |

| k cat / K m,ATP | ND | ND | 0.12 ± 0.01 | ND | 5 x 10-5 | ND | ND | ND | |

| k cat (s-1 site-1) | MT-ATPase | 60 ± 7 | 81 ± 2 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 21.0 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.49 ± 0.02 |

| K m,ATP (μΜ) | ND | 91 ± 10 | 9.5 ± 0.4 | ND | 40.9 ± 9.3 | 34 ± 6 | 28 ± 4 | 12.2 ± 2.8 | |

| k cat / K m,ATP | ND | 0.9 | 0.6 | ND | 0.06 | 0.014 | 0.075 | 0.04 | |

| K 0.5,MT (μΜ) | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.60 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 38.5 ± 3.3 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 9.6 ± 1.6 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | |

| k cat / K 0.5,MT | 18 | 405 | 8 | 11 | 0.07 | 49 | 0.22 | 0.08 | |

| K d,A (μΜ) | Apo | 0.4 ± 0.2 | ND | 0.03 – 0.05 | ND | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| K d,B (μΜ) | AMPPNP | 1 ± 0.1 | ND | 0.03 – 0.05 | ND | 9.4 ± 0.3 | ND | ND | ND |

| K d,C (μΜ) | ADP•Pi | 7 ± 0.6 | ND | ND | ND | 8.0 ± 0.7 | ND | ND | ND |

| K d,D (μΜ) | ADP | 22 ± 2 | ND | ND | ND | 11.6 ± 0.8 | ND | ND | ND |

See Fig. 1 for basal (i.e. no microtubules) and microtubule-simulated ATPase mechanisms

ND Not determined

a1Rosenfeld et al. (2001), 2Sadhu and Taylor (1992), 3Cochran et al. (2011), 4Moyer et al. (1998), 5Jiang et al. (1997), 6Cochran et al. (2004), 7Cochran and Gilbert (2005), 8Cochran et al. (2006), 9Rosenfeld et al. (2009), 10Cochran et al. (2009), 11Sontag et al. (unpublished), 12Hertzer et al. (2006), 13Mackey and Gilbert (2000), 14Song and Endow (1998), 15Mackey and Gilbert (2003)

Table 2.

Comparison of rate and equilibrium constants for truncated dimeric kinesins in published studiesa

| Constant (units) | Reaction | Kinesin-1 | Kinesin-5 | Kinesin-7 | Kinesin-14 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HsKHC1-4 | DmKHC5-8 | RnKHC9,10 | HsEg511-14 | HsCENP-E15 | XlCENP-E16,17 | DmNCD18-23 | ScKar3Cik124,25 | ScKar3Vik126,27 | ||

| k 0 (s-1) | ADP release from head 1 | ND | 306 ± 25 | >1000 | 28 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.01 | ND | 17.8 ± 1.6 | 110 ± 8 | 14.4 ± 0.3 |

| K +1 k +2 (μΜ-1 s-1) | ATP Binding | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 8.4 ± 0.02 | 18.6 ± 0.03 |

| k +2 (s-1) | Head isomerization | 457 ± 56 | >200 | 210 ± 25 | 50 ± 3 | 47.5 ± 0.8 | 13.7 ± 2.7 | >200 | 69 ± 1.4 | 54.9 ± 1.0 |

| k -2 (s-1) | ATP dissociation | 55–135 | 71 ± 9 | 18 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 101 ± 13 | 14 ± 5 | 16.6 ± 1.0 | 7.4 ± 0.9 |

| k +3 (s-1) | ADP release from head 2 | 170 ± 17 | 300 ± 100 | >1000 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 19.4 ± 0.6 | 56.8 ± 3.5 | 1.4 ± 0.02 | N/A | N/A |

| k +4 (s-1) | Hydrolysis | 79 ± 4 | 100 ± 30 | 500 | 5–10 | 24.7 ± 0.5 | ND | 35 ± 5 | 26 ± 0.8 | 25.9 ± 1.4 |

| k +5 (s-1) | Pi Release / Dissociation | 48–55 | 50 ± 8 | 80 | 6.6 ± 3.0 | 1.4 ± 0.01 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 12.2 ± 0.3 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.1 |

| k cat (s-1 site-1) | MT-ATPase | 20 ± 2 | 20 ± 2 | 40.3 ± 1.1 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 0.9 ± 0.02 | 12.1 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.02 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.1 |

| K m,ATP (μΜ) | 23 ± 9 | 61 ± 8 | 53.6 ± 4.8 | 7.9 ± 2.4 | 18.3 ± 2.5 | 35 ± 5 | 23.1 ± 1.5 | 65.2 ± 4.1 | 27.1 ± 2.9 | |

| k cat / K m,ATP | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.25 | |

| K 0.5,MT (μΜ) | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | ND | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 18.3 ± 5.1 | 0.7 ± 0.05 | 0.4 ± 0.02 | |

| k cat / K 0.5,MT | 66.7 | 22.2 | ND | 0.3 | 0.6 | 121 | 0.1 | 7.1 | 16.8 | |

| K 0 (μΜ) | No added nucleotide | ND | ND | ND | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 0.9 ± 0.1 | ND | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

| V max (μm/min) | MT gliding velocity | 42.2 ± 4.4 | 51.2 ± 1.5 | 39–48 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.66 ± 0.003 | 20.5 ± 0.6 | 10.2 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 |

| MT end directionality | Plus | Plus | Plus | Plus | Plus | Plus | Minus | Minus | Minus | |

| Stall force (pN) | 6 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | ND | 5 ± 1 | ND | 6 ± 1 | 1 ± 0.5c | ND | ND | |

ND Not determined; N/A Not applicable

aPublished studies: 1Rosenfeld et al. (2002), 2Rosenfeld et al. (2003), 3Clancy et al. (2011), 4Schnitzer et al. (2000), 5Gilbert et al. (1998), 6Coy et al. (1999), 7Moyer et al. (1998), 8Higuchi et al. (2004), 9Auerbach and Johnson (2005a), 10Mazumdar and Cross (1998), 11Krzysiak et al. (2006), 12Kikkawa and Hirokawa (2006), 13Krzysiak et al. (2008), 14 Valentine et al. (2006), 15Sardar and Gilbert (2012), 16Yardimci et al. (2008), 17Rosenfeld et al. (2009), 18Chandra et al. (1993), 19Foster et al. (1998), 20Foster and Gilbert (2000), 21Foster et al. (2001), 22Furuta et al. (2013), 23Heuston et al. (2010), 24Chen et al. (2011), 25Sproul et al. (2005), 26Allingham et al. (2007), 27Chen et al. (2012)

b K Hill value is the product of the K d values for cooperative sites in the Eg5 dimer (Krzysiak et al. 2006)

cStall force determined for 2–4 NCD motors linked via a rigid DNA scaffold with an ~6 or ~22-nm spacing (Furuta et al. 2013)

Table 3.

X-ray crystallographic structural summary for kinesin motors

| Family | Name | PDB ID | Notes | Nucleotide | Ligand(s) | Resolution (Å) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | HsKHC | 1bg2 | MgADP | Acetate | 1.8 | Kull et al. 1996 | |

| HsKHC | 1mkj | MgADP | SO4 | 2.7 | Sindelar et al. 2002 | ||

| RnKHC | 2kin | MgADP | SO4 | 2.0 | Sack et al. 1997 | ||

| NcKHC | 1goj | MgADP | 2.3 | Song et al. 2001 | |||

| RnKHC | 3kin | Dimer | ADP | 3.1 | Kozielski et al. 1997 | ||

| DmKHC | 2y5w | Dimer | MgADP | 2.7 | Kaan et al. 2011 | ||

| DmKHC | 2y65 | Dimer; Tail | MgADP | 2.2 | Kaan et al. 2011 | ||

| HsKHC | 4hna | MgADP⋅AlFx | Tubulin | 3.2 | Gigant et al. 2013 | ||

| Kinesin-2 | GiKIN2A | 2vvg | MgADP | 1.6 | Hoeng et al. 2008 | ||

| Kinesin-3 | MmKIF1A | 2zfi | MgADP | 1.6 | Nitta et al. 2008 | ||

| MmKIF1A | 1i6i | Collision | MgAMPPCP | 2.0 | Kikkawa et al. 2001 | ||

| MmKIF1A | 1vfv | Isomerization | MgAMPPNP | 1.9 | Nitta et al. 2004 | ||

| MmKIF1A | 1vfx | MgADP⋅AlFx | 2.6 | Nitta et al. 2004 | |||

| MmKIF1A | 1vfz | MgADP⋅VO4 | 2.2 | Nitta et al. 2004 | |||

| MmKIF1A | 2zfm | ADP | 2.3 | Nitta et al. 2008 | |||

| NcKIN3 | 2owm | MgADP | 3.3 | Nitta et al. 2008 | |||

| HsKIF3B | 3b6u | MgADP | 1.8 | Zhu et al. (SGC) | |||

| HsKIF3C | 3b6v | MgADP | 2.7 | Tempel et al. (SGC) | |||

| HsKIF13B | 3gbj | MgADP | 2.1 | Tong et al. (SGC) | |||

| MmKIF14 | 4ozq | β-sheet twist | ADP | 2.7 | Arora et al. 2014 | ||

| Kinesin-4 | MmKIF4A | 3zfd | MgAMPPNP | 1.7 | Chang et al. 2013 | ||

| HsKIF7 | 4a14 | MgADP | 1.6 | Klejnot and Kozielski 2012 | |||

| HsKIF7 | 2xt3 | MgADP | 1.9 | Klejnot and Kozielski 2012 | |||

| Kinesin-5 | HsEg5/KSP | 1ii6 | MgADP | NO3 | 2.1 | Turner et al. 2001 | |

| HsEg5/KSP | 3hqd | Isomerization | MgAMPPNP | PO4 | 2.2 | Parke et al. 2010 | |

| HsEg5/KSP | 1q0b | L5 Inhibitor | MgADP | Monastrol | 1.9 | Yan et al. 2004 | |

| HsEg5/KSP | 4ap0 | L5 Inhibitor | MgADP | Ispinesib | 2.6 | Talapatra et al. 2012 | |

| HsEg5/KSP | 4as7 | L5 Inhibitor | CoADP | SB743921 | 2.4 | Talapatra et al. 2013 | |

| HsEg5/KSP | 3zcw | α4 Inhibitor | MgADP | 4A2 | 1.7 | Ulaganathan et al. 2013 | |

| Kinesin-7 | HsCENP-E | 1t5c | MgADP | NO3 | 2.5 | Garcia-Saez et al. 2004 | |

| Kinesin-8 | HsKIF18A | 3lre | MgADP | 2.2 | Peters et al. 2010 | ||

| Kinesin-9 | HsKIF9 | 3nwn | MgADP | 2.0 | Zhu et al. (SGC) | ||

| Kinesin-10 | HsKIF22 | 3bfn | MgADP | 2.3 | Zhu et al. (SGC) | ||

| DmNOD | 3 dc4 | MgADP | 1.9 | Cochran et al. 2009 | |||

| DmNOD | 3dcb | MgAMPPNP | 2.5 | Cochran et al. 2009 | |||

| DmNOD | 3pxn | MnADP | 2.6 | Cochran et al. 2011 | |||

| Kinesin-12 | HsKIF15 | 4bn2 | MgADP | 2.7 | Klejnot et al. 2014 | ||

| Kinesin-13 | MmKIF2C | 1v8j | MgADP | 3.2 | Ogawa et al. 2004 | ||

| MmKIF2C | 1v8k | MgAMPPNP | 2.3 | Ogawa et al. 2004 | |||

| PfKINI | 1ry6 | SO4 | 1.6 | Shipley et al. 2004 | |||

| HsKIF2A | 2gry | MgADP | 2.4 | Wang et al. (SGC) | |||

| HsKIF2C | 2heh | MgADP | 2.2 | Wang et al. (SGC) | |||

| Kinesin-14 | DmNCD | 2ncd | Dimer | ADP | SO4 | 2.5 | Sablin et al. 1998 |

| DmNCD | 1cz7 | Dimer | MgADP | 2.9 | Kozielski et al. 1998 | ||

| DmNCD | 1n6m | Dimer | MgADP | 2.5 | Yun et al. 2003 | ||

| DmNCD | 3l1c | Dimer; T436S | MgADP | 2.8 | Heuston et al. 2010 | ||

| DmNCD | 3u06 | Dimer; G347D | MgADP | 2.4 | Liu et al. 2012b | ||

| ScKAR3 | 3kar | MgADP | 2.3 | Gulick et al. 1998 | |||

| ScKAR3 | 1f9t | WT | MgADP | 1.5 | Yun et al. 2001 | ||

| ScKAR3 | 1f9u | N650K | MgADP | 1.7 | Yun et al. 2001 | ||

| ScKAR3 | 1f9v | R598A | MgADP | 1.3 | Yun et al. 2001 | ||

| ScKAR3 | 1f9w | E631A | MgADP | 2.5 | Yun et al. 2001 | ||

| ScKAR3/VIK1 | 4etp | MgADP | 2.3 | Rank et al. 2012 | |||

| CgKAR3 | 4gkr | MgADP | 2.7 | Duan et al. 2012b | |||

| CaKAR3 | 4h1g | MBP fusion | MgADP | 2.2 | Delorme et al. 2012 | ||

| AgKAR3 | 3t0q | MgADP | 2.4 | Duan et al. 2012a | |||

| StKCBP | 1sdm | MgADP | 2.3 | Vinogradova et al. 2004 | |||

| StKCBP | 3cob | Extended α4 | MgADP | 2.2 | Vinogradova et al. 2008 | ||

| StKCBP | 3h4s | Regulator KIC | MgADP | 2.4 | Vinogradova et al. 2009 | ||

| AtKCBP | 4frz | MgADP | 2.4 | Vinogradova et al. 2013 | |||

| HsKIFC1 | 2rep | MgADP | 2.6 | Zhu et al. (SGC) | |||

| HsKIFC3 | 2 h58 | MgADP | 1.9 | Wang et al. (SGC) | |||

| ScVIK1 | 2o0a | Nonmotor | N/A | 1.6 | Allingham et al. 2007 |

SGC Structural Genomics Consortium Toronto; N/A Not applicable

For dimeric kinesins, the ATPase mechanism is more complicated due to the intramolecular communication between the two heads of the dimer (Fig. 2). This intramolecular communication (aka gating) is both chemical and mechanical in nature and functions to ensure one head is tightly bound to the filament at any given point in the cycle for processive motility (Block 2007). Historically, kinesins have been purified with ADP bound to the active site (Muller et al. 1999); and upon interaction with the microtubule, the first head (head 1) tightly binds the filament and releases its bound ADP very rapidly, while the second head (head 2) remains tightly bound to ADP and weakly bound to the microtubule (Ma and Taylor 1997). Upon ATP binding to head 1, a conformational change in the motor domain induces the neck linker to dock (Asenjo et al. 2006; Khalil et al. 2008; Rice et al. 1999; Rosenfeld et al. 2001; Skiniotis et al. 2003; Sugata et al. 2004; Sugata et al. 2009) and thus bias the diffusional search by head 2 toward its next microtubule binding site in the direction of the plus-end. Head 2 will tightly bind the microtubule and rapidly release its ADP, leading to a “strained” complex with two heads tightly bound to the microtubule, thus resulting in significant head–head tension (Hariharan and Hancock 2009; Hyeon and Onuchic 2007). This intramolecular strain is thought to decrease the affinity of the front head (head 2) for ATP until the rear head (head 1) hydrolyzes ATP and detaches from the microtubule (Guydosh and Block 2006; Klumpp et al. 2004b; Rosenfeld et al. 2003), as well as to trigger ATP hydrolysis and accelerate detachment of the rear head (Crevel et al. 2004; Farrell et al. 2002; Schief et al. 2004; Yildiz et al. 2008). After ATP hydrolysis and Pi release from the rear head (head 1), this head detaches and effectively brings the motor to the beginning of the cycle, with the exception that the heads have swapped position (i.e., head 1 is now tightly bound to ADP and weakly bound to the microtubule, and head 2 is tightly bound to the microtubule where it awaits ATP binding). This finely tuned mechanochemical cycle maintains head–head coordination in order to keep each head’s ATPase cycle out of phase so that the motor is able to take hundreds of steps (for kinesin-1, kinesin-7 and kinesin-8), five to ten steps (for kinesin-5), or thousands of steps (for kinesin-3) along the microtubules without completely detaching and diffusing away from the track (this topic is discussed in more detail in the “Physics” section of this review).

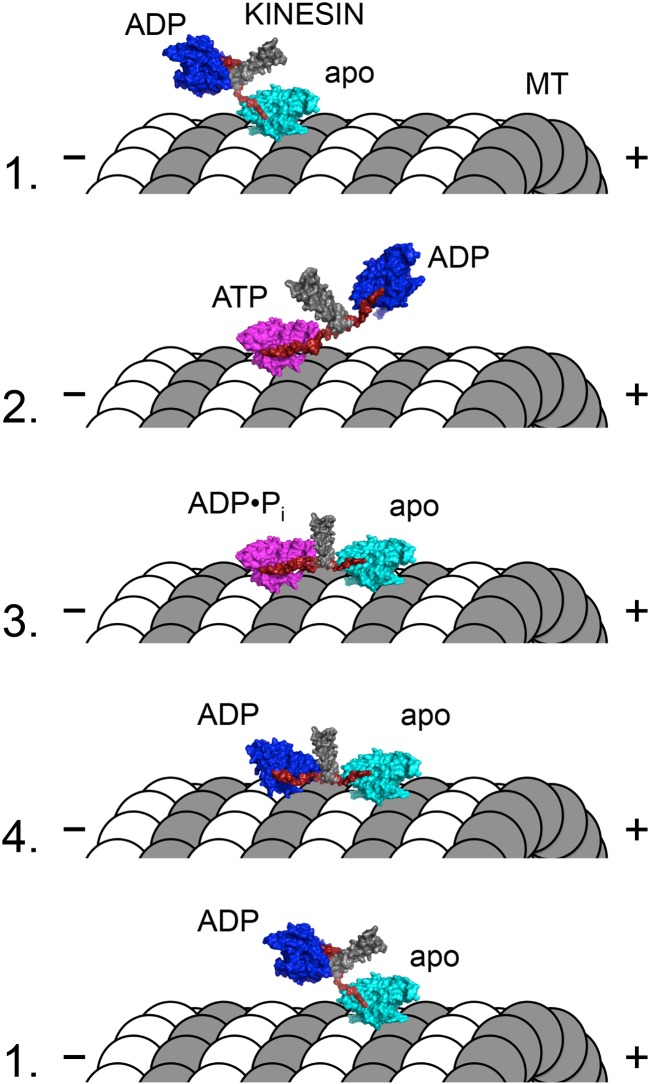

Fig. 2.

Model for the kinesin-1 “hand-over-hand” walking mechanism. Molecular representations of the dimeric kinesin-1 motor and microtubule (MT) are shown in each of four states (labeled numbers to the left of figure). The coiled–coil stalk (gray) and neck linker (red) are highlighted in each state. Coloring of the kinesin motor core represents three structural states: dark blue strongly ADP-bound, weakly microtubule-bound, neck linker undocked; cyan weakly nucleotide-bound, strongly microtubule-bound, neck linker undocked; magenta strongly ATP- or ADP•Pi-bound, strongly microtubule-bound, neck linker docked. Dimeric kinesin-1 motors are purified with ADP tightly bound to both active sites. The first head to strongly interact with the microtubule (head 1) will rapidly release its bound ADP to reach the nucleotide-free/apo/rigor state (state 1). Since head 2 remains unattached to the microtubule, head 1 is able to bind ATP, which docks the neck linker of head 1, biasing head 2 forward (i.e., toward the MT plus-end) to the next binding site on the same MT protofilament (state 2). ATP hydrolysis on head 1 is concomitant with tight microtubule-binding by head 2 to rapidly release its ADP product (state 3). Upon Pi release from head 1, intramolecular strain coupled to conformational changes in the ADP state of head 1 lead to weakening of head 1’s interaction with the MT (state 3). After detachment of head 1 from the MT, the kinesin effectively reaches state 1 with the exception that the heads trade places (i.e., head 2 is nucleotide-free/apo/rigor while head 1 is ADP-bound and detached from the MT). The transition from state 3 to state 4 leads to a release of the intramolecular tension that is thought to provide a mechanical gating of ATP binding to the front head

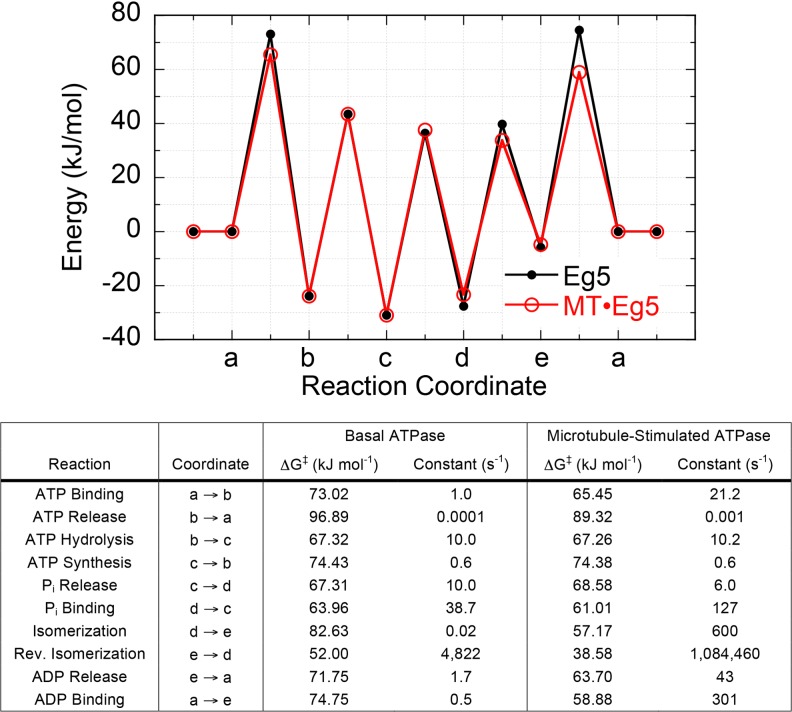

In the absence of microtubules, most purified kinesin motors are unstable and will denature when the nucleotide is removed from its active site (Pechatnikova and Taylor 1997; Sadhu and Taylor 1992). Past studies with monomeric kinesin-5 (Eg5) have demonstrated that the motor domain is stable and active when purified away from the bound ADP (Cochran and Gilbert 2005). Using kinetic (Cochran and Gilbert 2005; Cochran et al. 2006; Cochran et al. 2004; Rosenfeld et al. 2005) and thermodynamic (Zhao et al. 2010) methodologies, the energy landscape has been defined in the absence and presence of microtubules (note: a more thorough discussion of this energy landscape is found in the “Physics” section of this review). The microtubule modulates the energy landscape in three major ways: (1) by accelerating the rate of ATP binding, (2) by weakening ADP binding, and (3) by accelerating the rate of ADP release. Thus, the microtubule acts as an ATPase-activating protein as well as an ADP-exchange factor, analogous to GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for small G proteins (Bos et al. 2007).

Steady-state ATPase

The kinetic study of kinesin family members has been made possible through the purification of truncated constructs from a recombinant source (usually Escherichia coli or baculovirus). After preparation, the protein concentration must be established using available methods (e.g. Bradford assay or ultraviolet light absorbance at 280 nm). The first step in understanding the kinetic properties of the motor is to determine the microtubule-activated Michaelis–Menten steady-state ATPase activity of kinesin, which simply requires measuring the products of ATP hydrolysis (ADP or Pi) produced as a function of time [note: see De La Cruz and Ostap (2009); Gilbert and Mackey (2000) for methods to monitor hydrolysis product formation]. The aim of such experiments is to characterize the steady-state kinetic parameters (k cat, K m,ATP, K 0.5,MT) using a set of reciprocal experiments. In the first experiment, the microtubule concentration is kept constant and in excess (ideally 10-fold higher than the K 0.5,MT) and the ATP concentration is varied. The initial ATPase velocity (i.e., v o, slope of a plot of product formed over time) is then plotted against ATP concentration and the data fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation (Michaelis and Menten 1913; Michaelis et al. 2011):

| 1 |

where [E]o is the total concentration of kinesin [which ideally is 100- to 1,000-fold lower than the lowest ATP concentration ([ATP]) in the experiment], k cat is the maximum rate of ATP turnover per enzyme active site at infinite [ATP], and K m,ATP is the Michaelis constant, which is defined as the [ATP] which yields ½ [E]o k cat.

In the second experiment, the ATP concentration is kept constant and in excess (ideally 10-fold higher than K m,ATP) and the microtubule concentration is varied. The initial ATPase velocity is plotted against microtubule concentration and the data fit to the following quadratic equation since (1) [E]o is rarely 100- to 1,000-fold lower than the lowest microtubule concentration in the experiment, (2) the microtubules are not consumed in the reaction (whereas ATP does get consumed as a substrate), and (3) microtubules typically bind very tightly to kinesin (Morrison 1969). Thus,

| 2 |

where [E]o is the total concentration of kinesin {typically 2- to 10-fold lower than the lowest microtubule concentration ([MT])]}, k cat is the maximum rate of ATP turnover per enzyme active site at infinite [MT], and K 0.5,MT is the [MT] that yields ½ [E]o k cat.

It has been observed that unpolymerized tubulin heterodimers stimulate the ATPase activity of various kinesin motors (Alonso et al. 2007; Arora et al. 2014; Friel and Howard 2011; Gigant et al. 2013; Hertzer et al. 2006). Tubulin-stimulated ATPase activity in kinesin can be assayed in a similar manner as described above [i.e., with [ATP] held constant and in excess (10-fold higher than K m,ATP) while the concentration of unpolymerized tubulin is varied]. One must be thorough and also perform an ATP-concentration dependence test with excess tubulin heterodimer (ideally 10-fold higher than the K 0.5,tub) to test if the substrate binding affinity is different when kinesin is bound to tubulin heterodimers rather than polymerized microtubules. An important consideration for this analysis would be to test that the tubulin is not polymerizing under the experimental conditions. Sedimentation and light microscopy using fluorescently labeled tubulin are two commonly used experimental strategies to provide evidence that tubulin remains soluble and unpolymerized. Also, recent studies have demonstrated a designed ankyrin repeat protein (DARPin) that blocks longitudinal interaction between tubulin dimers along the protofilament axis, thus preventing microtubule polymer formation (Gigant et al. 2013; Pecqueur et al. 2012). This biochemical reagent can be useful to ensure non-polymerizable tubulin conditions.

Steady-state ATPase assays have also been useful for assessing the binding affinity of allosteric inhibitors of multiple different kinesin motors (Catarinella et al. 2009; Cochran et al. 2005; DeBonis et al. 2003; Maliga et al. 2002; Skoufias et al. 2006; Tcherniuk et al. 2010; Wood et al. 2010). Typically, these steady-state assays are designed by varying the inhibitor concentration in the presence of excess ATP and microtubule concentrations. However, with this added reagent to the ATPase reaction, one can determine the ATP affinity (vary [ATP] while keeping microtubule and inhibitor concentrations constant) and microtubule affinity (vary microtubule concentration while keeping [ATP] and inhibitor concentration constant) in the presence of the inhibitor (Cochran et al. 2005). Results from these experiments are important for deciphering the mechanism of kinesin inhibition and establish the foundation for the design of subsequent kinetic and thermodynamic experiments.

Together, these steady-state assays provide information on important properties of the kinesin enzyme, including the apparent binding affinities for ATP (K m,ATP) and microtubules (K 0.5,MT), as well as the quantitative measure of the maximum rate of ATPase activity (k cat). However, since the Michaelis–Menten theory does not adequately model even the minimal ATPase mechanism for kinesin (Fig. 1), one must be careful in the interpretation of the meaning of these steady-state kinetic parameters. Also, the determination of the k cat requires an accurate measure of the active enzyme population, which can be a very challenging task for a protein enzymologist. Monomeric kinesins have been shown to have a range of microtubule-stimulated k cat values, i.e., 0.5–80 s-1, K m,ATP values of between 9 and 90 μM, and K 0.5,MT values of between 0.01 and 10 μM (Table 1). The enzymatic efficiency (k cat/K m,ATP) and the biochemical “processivity” [k bi = k cat/K 0.5,MT; (Hackney 1995a; Hackney 1995b)] of the motor can be derived from the steady-state constants, which range from 0.04 to 0.9 μM-1 s-1 and from 0.07 to 405 μM-1 s-1, respectively. For dimeric kinesin motors (Table 2), k cat values range from 0.5 to 40 s-1, K m,ATP values range from 8 to 65 μM, and K 0.5,MT values range from 0.1 to 20 μM, with the enzymatic efficiency and biochemical processivity ranging from 0.05 to 0.9 μM-1 s-1 and from 0.1 to 121 μM-1 s-1, respectively. Despite the relatively minimal information attained through these assays, this information is essential for the design of more complicated pre-steady-state experiments to measure intrinsic rate constants for ATP binding/release, microtubule association/dissociation, Pi release, and ADP binding/release, as well as for the design of parameters for cosedimentation experiments.

Microtubule⋅kinesin cosedimentation

Cosedimentation experiments have historically been performed to quantify the concentration of kinesin that pellets (or sediments) with microtubule polymers after ultra-high speed centrifugation. Since this methodology provides the effective dissociation constant (K d) of an ensemble of kinesin states, various nucleotides (or nucleotide analogs) can be added in excess to the reaction to assess how different nucleotide states can influence microtubule binding affinity. For this assay, the kinesin concentration is typically kept constant, and microtubules are titrated into the reaction where they are allowed to equilibrate prior to centrifugation at ultra-high speed. Samples of the supernatant and pellet are prepared for analysis by SDS-PAGE. The fraction (f) of total kinesin [E]o bound to microtubules [E⋅MT] is plotted as a function of microtubule concentration, and the data are fit to a quadratic equation (Eq. 6):

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

To ascertain mechanistic information for the kinesin affinity for microtubules at various nucleotide states (nucleotide-free/apo/rigor: apyrase or alkaline phosphatase treatment; ATP-like: AMPPNP, AMPPCP, ATPγS; ADP⋅Pi-like: ADP + BeFx, AlFx, VO4 -, SO4 -; ADP; steady-state ATP hydrolysis), care must be taken to ensure that the “equilibrium population” being studied demonstrates a valid biochemical state that will lead to sound interpretation. For example, if you want to characterize the fraction of kinesin motors bound to microtubules under steady-state ATP hydrolysis conditions, the concentrations of reagents and timing for incubation prior to sedimentation must be correct to monitor the binding under “steady-state” ATP turnover conditions. Often an ATP-regeneration system [pyruvate kinase/phospho(enol)pyruvate or creatine kinase/phosphocreatine] will assist in keeping ATP concentrations “constant,” but may interfere with densitometry analysis of Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Overall, this cosedimentation methodology is very powerful in elucidating the mechanochemistry of a kinesin motor and is a relatively simple experiment to perform in a biochemistry laboratory.

Care must be taken in the design and interpretation of cosedimentation results. Typically, these experiments rely on Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel and densitometry analysis, which sets the lower limit for the concentration of kinesin used in the experiment. Under most nucleotide conditions, kinesin binds tightly to microtubules (usually a 10- to 100-fold lower K d than the kinesin concentration) and renders an inaccurate measurement of the binding constant. Alternative SDS-gel staining methods (e.g., Sypro Ruby; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) have been utilized to perform the cosedimentation experiments at lower kinesin concentrations (Allingham et al. 2007), however the error in the standard curve using low quantities of protein (5–20 ng) renders experimental reproducibility difficult, ultimately leading to large standard deviations in observed binding constants (±10–30 %). It is possible that emerging technologies, such as microscale thermophoresis (Seidel et al. 2013) or isothermal titration calorimetry (Devred et al. 2010; Tsvetkov et al. 2013), will provide a means to accurately determine the kinesin–microtubule binding constant under various nucleotide conditions.

ATP binding

The kinetic mechanism of substrate binding to an enzyme is very important in enzymology. This is especially true for nucleotide binding to kinesin motors since conformational changes during MgATP binding are central to harnessing of the free energy of ATP hydrolysis for force production (Rice et al. 1999). Depending on how the observed rate of the reaction changes as a function of ATP concentration, the data can reveal the presence of intermediate steps after (or before) ATP binding that limit the rate of this reaction. Several methodologies are available for measuring the presteady-state ATP binding kinetics for kinesins, including fluorescent nucleotide binding experiments (mant-ATP), radiolabeled pulse-chase methodologies, FRET methods, and intrinsic protein fluorescence experiments (in the absence of microtubules). All kinesins studied to date have demonstrated (at least) a two-step rapid equilibrium binding mechanism in the presence or absence of microtubules. This binding mechanism can follow two similar (yet distinct) pathways:

| 7 |

| 8 |

In the first mechanism (Eq. 7), the ATP substrate collides with the kinesin motor (E) and weakly interacts. Then, upon a reversible isomerization (i.e., change in conformational state) of the E⋅S complex, the motor tightens its interaction with ATP to form the E*⋅S intermediate. In the second mechanism (Eq. 8), the motor undergoes a reversible isomerization prior to binding the ATP substrate, which is followed by tight ATP binding. The difference between these two mechanisms centers on the timing of the reversible isomerization step (i.e., a conformation change after or before ATP binding, respectively). Either mechanism satisfies the curvature in the concentration dependence of the observed reaction rate, which is indicative of (at least) a two-step mechanism approaching a maximum rate that is limited by a first-order isomerization of the E⋅S complex (or E prior to binding ATP).

Monomeric kinesin motors have shown a wide range of ATP binding affinities in the absence and presence of microtubules (K +1′ k +2′ = 0.08–400 μM-1 s-1 and 1–20 μM-1 s-1, respectively; Table 1) as well as a range of isomerization rates (k +2′ = 0.5–1800 s-1 and 20–900 s-1, respectively; Table 1). Dimeric kinesins have also demonstrated a wide range of ATP binding kinetics when bound to microtubules (K +1 k +2 = 1–20 μM-1 s-1 and k +2 = 10–500 s-1; Table 2). These kinetic constants indicate that kinesin motors have diverse ways of interacting with ATP substrate and that the structural interpretation for these kinetics may not be as straightforward as some have suggested (Chang et al. 2013).

ATP hydrolysis

After ATP binds tightly to the kinesin core, the motor can adopt the necessary active site configuration that promotes rapid hydrolysis of the γ-phosphate from ATP. In certain kinesins [e.g., monomeric Drosophila kinesin-10 in the absence and presence of microtubules (Cochran et al. 2009); monomeric human kinesin-13 in the absence of microtubules (Friel and Howard 2011)] and microtubule-stimulated dimeric human kinesin-5 (Krzysiak and Gilbert 2006)], this conformational change in the core represents the slow, rate-limiting step in the pathway. For other well-characterized kinesins, this reaction is relatively fast during the ATPase cycle (Tables 1 and 2), so the time spent in the ATP-bound state is transient. Subsequent to the characterization of ATP binding kinetics, rapid acid-quench-flow methodologies are used to measure the kinetics of the ATP hydrolysis reaction (Gilbert and Mackey 2000; Johnson 1992). However, since the kinetics of ATP binding precede the hydrolysis reaction, care must be taken in the interpretation of observed kinetics determined by acid-quench experiments. Normally kinetic simulation and global data fitting software are utilized to fit presteady-state data to the minimal mechanism based on numerical integration of the rate equations [e.g. DynaFit (Kuzmic 1996), KINSIM/FITSIM (Barshop et al. 1983; Zimmerle and Frieden 1989), or Global Kinetic Explorer (Johnson et al. 2009)].

ATP hydrolysis is a thermodynamically favorable reaction (ΔG° = –35.6 kJ mol-1; see Appendix A), yet, when uncatalyzed, is a very slow reaction (ΔG‡ = 115 kJ mol-1, k uncat = 3.8 × 10-8 s-1, t 0.5 = 211 days; Stockbridge and Wolfenden 2009). ATPases catalyze this reaction by lowering the energy of the transition state relative to the reactants through either a “dissociative” mechanism, an “associative” mechanism, or a “concerted” mechanism between these two extremes (Admiraal and Herschlag 1995; Khan and Kirby 1970; Thatcher and Kluger 1989). A substantial amount of data supports a largely “dissociative” mechanism for phosphoanhydride hydrolysis in which bond cleavage precedes nucleophilic attack by the lytic water molecule, thus leading to a metaphosphate-like transition state (Bunton and Chaimovi 1965; Halkides and Frey 1991; Lightcap and Frey 1992; Miller and Ukena 1969; Miller and Westheim 1966a; Miller and Westheim 1966b). Recent studies using combined quantum–mechanical/molecular–mechanical metadynamics simulations support the “dissociative” model of ATP hydrolysis by kinesin whereby two water molecules participate in proton transfer to ultimately the Pi product (McGrath et al. 2013). These two water molecules (one “lytic” water molecule located proximal to the γ-phosphate and a second “relay” water molecule positioned between the lytic water molecule and the switch-2 glutamic acid that forms a salt bridge with the switch-1 arginine; for more detail, see the “Structure” section of this review) establish a network of hydrogen bonds in the hydrolysis-competent conformation of motor ATPases (Dittrich et al. 2003; Dittrich et al. 2004; Grigorenko et al. 2011; Grigorenko et al. 2007; Hayashi et al. 2012; Onishi et al. 2004; Parke et al. 2010; Schwarzl et al. 2006).

This “hydrolysis-competent” conformational state of the motor must be a very transient (i.e., short-lived) structural intermediate that rapidly isomerizes to a state that is not conducive for ATP synthesis for monomeric kinesins in the absence and presence of microtubules, yet the trailing head in a dimeric kinesin does show propensity for ATP synthesis (Hackney 2005). Despite having an abundant quantity of data available on the ATP hydrolysis reaction and various conformational states of motor ATPases, it remains unknown how sequential conformational changes in hydrolases catalyze nucleotide bond cleavage.

Pi release

After ATP hydrolysis produces its reaction products (ADP and Pi), Pi product release occurs first, followed by ADP release. For most kinesins, Pi release leads to an allosteric change in the microtubule-binding region that weakens the motor’s affinity for the microtubule (see below). Therefore, Pi release is one of the pivotal reactions in the kinesin ATPase cycle, yet arguably the most difficult to experimentally study since it is a transient step buried deep within the mechanism. Although Pi release is typically a rapid reaction in the basal ATPase cycle, monomeric kinesin-1, kinesin-5, and kinesin-7 motors demonstrate rate-limiting Pi release for their microtubule-stimulated ATPase cycles [(Cochran and Gilbert 2005; Cochran et al. 2006; Cochran et al. 2004; Cochran et al. 2011; Moyer et al. 1998; Rosenfeld et al. 2001; Rosenfeld et al. 2009); Table 1].

Experimental strategies have been developed to directly measure the rapid kinetics of Pi release from kinesin in the absence and presence of microtubules using a fluorescence-coupled assay (Brune et al. 1994; White et al. 1997). This strategy relies on the very rapid (i.e., near diffusion-limited reaction) and tight (K d,Pi ~ 100 nM) binding of Pi to a modified phosphate-binding protein with the MDCC fluorophore (MDCC-PBP; Phosphate Sensor® from Life Technologies). This reagent can be rapidly mixed in a kinesin-catalyzed ATPase reaction using a stopped-flow fluorimeter, and fluorescence can be monitored over time to measure the kinetics of Pi release. After ATP hydrolysis, Pi is released from the kinesin active site, followed by rapid and tight Pi binding to MDCC-PBP, thus triggering a five- to sixfold fluorescence enhancement of the MDCC-PBP⋅Pi complex. Since this assay is very sensitive to Pi in solution, a “Pi mop” consisting of 7-methylguanosine and purine nucleoside phosphorylase must be added to effectively eliminate background Pi before the ATPase reaction is initiated (Cochran and Gilbert 2005). Depending on the intrinsic rate constant for Pi release in relation to the other steps in the ATPase cycle, various outcomes are possible for the observed rate of reaction (e.g., linear kinetics if Pi release is the rate-limiting step or burst kinetics if a step after Pi release is rate-limiting). Also, the presence or absence of an initial exponential lag phase can provide insight into the rate of a given reaction prior to Pi release, which can be compared with observed rates of ATP binding or ATP hydrolysis reactions. Kinetic simulation and global data fitting software ought to be utilized to model the intrinsic rate constant for Pi release since both the ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis steps precede this reaction (note: Pi rebinding to kinesin can be ignored due to the Pi binding to MDCC-PBP rendering the reaction kinetically irreversible).

MgADP release

The final reaction that completes the kinesin ATPase cycle is MgADP release to reach the nucleotide-free/apo/rigor state. For the basal ATPase cycle, this step represents the rate-limiting reaction for most (but not all) kinesin motors (Table 1). The observed presteady-state rate of ADP release in the absence of microtubules is typically similar to the measured basal ATPase activity, strengthening the argument for ADP release being rate-limiting in the cycle (Table 1). However, in the presence of microtubules, the rate of ADP release is dramatically accelerated for most kinesins (3–5 orders of magnitude). For kinesin-14 motors, the rate of MgADP release remains the rate-limiting step in the mechanism, but for other kinesins, the rate of this reaction no longer limits steady-state ATPase activity (Tables 1 and 2).

The mechanism of MgADP release has been the subject of multiple investigations since the discovery of kinesin, yet it remains a poorly understood step in the kinesin ATPase cycle. Several techniques are available to measure the presteady-state rate constants for MgADP binding and release, including mant-ADP fluorescence (both direct excitation/emission and FRET from protein tryptophans and tyrosines), intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (in the absence of microtubules), and radiolabeled ADP chase experiments using a rapid ATP regeneration system. One can also measure the kinesin or microtubule⋅kinesin complex binding affinity for ADP using mant-ATP binding competition assays (De La Cruz and Ostap 2009; Zhao et al. 2010). Each method has advantages and limitations that must be taken into consideration when determining the mechanism of ADP product release. If nucleotide-free kinesin can be attained, the kinetics of MgADP binding can be measured in the absence of microtubules (Cochran et al. 2009; Zhao et al. 2010). Most kinesins are stable in the nucleotide-free state when bound tightly to microtubules. Therefore, presteady-state MgADP binding kinetics can be measured for the microtubule⋅kinesin complex (Table 1). The mechanism of MgADP binding ought to provide insight into the pathway for ADP release from kinesins since the intrinsic rate constants that govern the minimal mechanism can be derived from the fit of the ADP concentration dependence of the observed reaction rate (Johnson 1992).

All kinesins studied to date have demonstrated (at least) a two-step rapid equilibrium binding mechanism for MgADP binding in the presence or absence of microtubules. As with MgATP binding, this binding mechanism can follow two similar (yet distinct) pathways:

| 9 |

| 10 |

The difference between these two mechanisms centers on the timing of the reversible isomerization step (i.e., a conformation change after or before ADP binding, respectively). Although the reversible isomerization of the kinesin motor domain has been demonstrated using enzyme kinetics, the details of the structural changes that drive this isomerization remain mysterious.

Monomeric kinesin motors have shown a wide range of ADP binding affinities in the absence and presence of microtubules (K -6′ k -5′ = 0.07–330 μM-1 s-1 and 0.6–11 μM-1 s-1, respectively; Table 1), as well as a range of isomerization rates (k -5′ = 0.6–1400 s-1 and 100–760 s-1, respectively; Table 1). As with MgATP binding, the variability of rate constants governing MgADP binding suggests that the conformational changes occurring in each motor extend beyond the conserved active site motifs. What remains an unexplainable phenomenon is the symmetry of the rate constants that limit the isomerization reactions for MgATP and MgADP binding. For example, these rates were measured at 0.5–1 s-1 for monomeric kinesin-5 in the absence of microtubules using multiple different methodologies (Cochran and Gilbert 2005), suggesting the rate-determining structural change is dictated by a reaction that does not require the presence of the nucleotide γ-phosphate.

Microtubule detachment and binding

How kinesin motors convert the energy of ATP hydrolysis into directed mechanical work largely relies on allosteric changes in the region of the motor that interacts with the microtubule in order to modulate binding affinity. A wealth of data supports the notion that the kinesin nucleotide state modulates the microtubule binding affinity and vice versa. Thus, not only measuring the equilibrium binding constants under different nucleotide conditions (as described above), but also measuring the kinetics of microtubule binding (aka microtubule association) and microtubule detachment (aka microtubule dissociation) is important for deciphering the kinesin ATPase mechanism.

These presteady-state experiments have been adopted from similar methodologies from the actomyosin (Finlayson et al. 1969; Finlayson and Taylor 1969) and axonemal dynein systems (Porter and Johnson 1983). Solution turbidity (λ = 340–350 nm at 180° to the incident beam) and light scattering (λ = 420 nm at 90° to the incident beam) provide optical signals for kinesin binding to or detaching from microtubules, which can be monitored over time in a rapid mixing stopped-flow fluorimeter. This experimental design depends on: (1) the turbidity/light scattering signal from the microtubule⋅kinesin complex is greater than the sum of turbidity/light scattering signals from the individual components; (2) the formation of or dissociation of the microtubule⋅kinesin complex follows simple exponential kinetics; (3) the initial and final equilibrium states can be characterized using other biophysical methodologies, such as cosedimentation or analytical ultracentrifugation, to confirm either complex formation or dissociation (Finlayson et al. 1969). For measuring the kinetics of microtubule⋅kinesin complex formation, kinesin motors under various nucleotide conditions are rapidly mixed with increasing concentrations of taxol-stabilized microtubules, and the observed rate of the change of turbidity/light scattering is plotted as a function of microtubule concentration. The fit of the data provides the apparent second-order rate constant for kinesin association with microtubules. For measuring the kinetics of microtubule⋅kinesin complex dissociation, the microtubule⋅kinesin complex is rapidly mixed with increasing concentrations of MgATP + extra salt (typical ionic strength 100–200 mM). The MgATP triggers the kinesin to detach from the microtubule during the ATPase cycle, whereas the increased ionic strength promotes weak microtubule⋅kinesin interaction, thus shifting the kinesin population towards its detached state. The observed rate of turbidity/light scattering is plotted as a function of MgATP concentration, and the hyperbolic fit provides the maximal rate of kinesin dissocation and the relative binding affinity of kinesin for MgATP.

Structure

The very first glimpse into how the kinesin motor is built came from determination of the high-resolution structure of the kinesin-1 motor domain based on by X-ray crystallography [Fig. 3; (Kull et al. 1996)], which showed that the kinesin-1 motor has many similarities with the related myosin motor domain (Rayment et al. 1993). Since then, over 100 kinesin structures from multiple families have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank (PDB; Table 3). and detailed reviews of these structures have been published (Kull 2000; Kull and Endow 2002; Marx et al. 2009; Marx et al. 2005; Woehlke 2001).

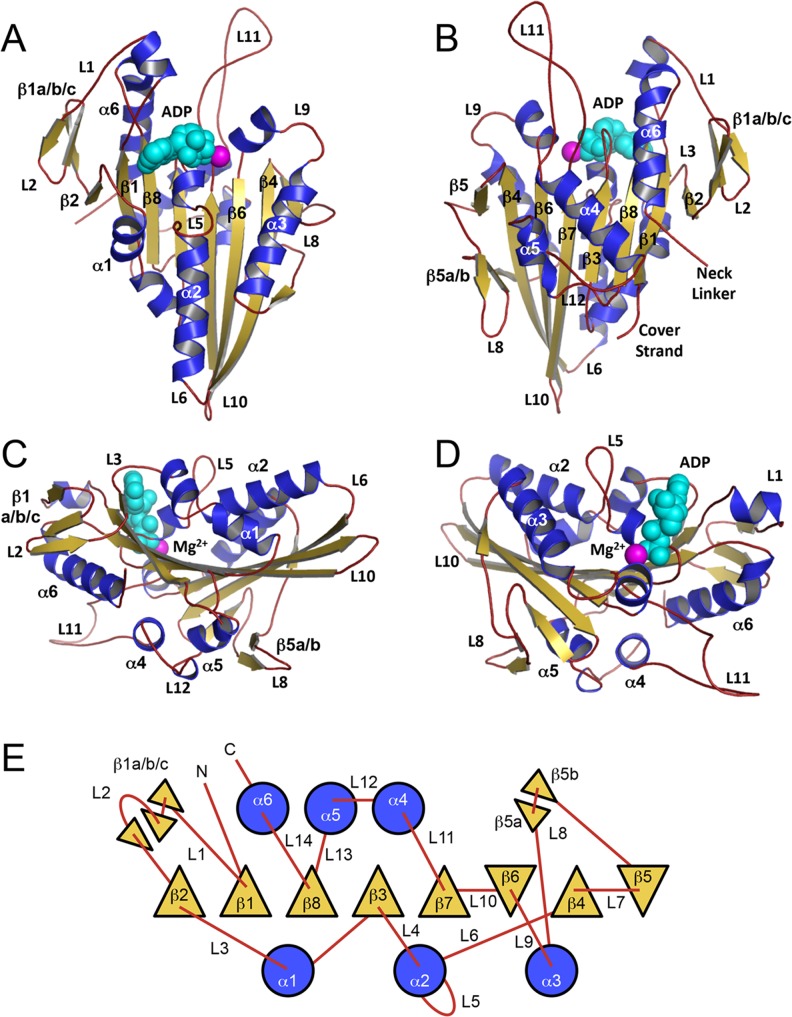

Fig. 3.

Kinesin structure and topology. The monomeric human kinesin-1 structure (1BG2; Kull et al. 1996) is depicted in four distinct orientations: a front, b back, c left side, d right side. Secondary structure elements (α-helices, β-strands, and loops) are colored blue, gold, and red, respectively. Mg2+ and ADP are shown as space-fill model and are colored magenta and cyan, respectively. e Topology diagram of the kinesin motor domain shows α-helices (circles; shaded blue; up/down direction indicated by loop attachment), β-strands (triangles; shaded gold; up/down to depict orientation), and loops (red lines) as rendered from (Kull et al. 1998)

The kinesin motor domain contains: (1) the motor core consisting of an αβα fold with three α-helices on each side of an eight-stranded β-sheet; (2) a family-specific neck-linker sequence immediately preceding or following the core in its primary sequence; (3) a motif called the cover strand at the opposite terminus relative to the neck linker (e.g., kinesin-5 has its neck linker at the C-terminus and the cover strand has its neck-linker at the N-terminus relative to the core). The neck linker is central for energy transduction in kinesin motors (Rice et al. 1999; Schief and Howard 2001) and is also important for communicating strain between the two motor domains of dimeric kinesins to chemically and physically gate the mechanochemical cycle (Guydosh and Block 2006; Hwang and Lang 2009; Hyeon and Onuchic 2007; Jaud et al. 2006; Miyazono et al. 2010; Rosenfeld et al. 2003; Shastry and Hancock 2010; Yildiz et al. 2008). Although the neck linker and the cover strand are at opposite ends of the core in the primary sequence, they are in close tertiary-structural proximity due to the physical location for where the N- and C-termini enter and exit the core, respectively (Fig. 3). The cover strand interacts with the neck linker to form the cover-neck bundle, which is thought to participate in force generation (Hwang et al. 2008; Khalil et al. 2008).

The core contains several key structural motifs present in all kinesin motors. First, located on opposite sides of the eight-stranded β-sheet are the nucleotide binding pocket and the microtubule-binding interface (β5-L8 lobe, L11, and the “Sw2 cluster” comprised of α4-L12-α5; Sosa et al. 1997; Woehlke et al. 1997). Second, conserved motifs called the phosphate binding loop (P-loop: Walker A motif consensus GxxxxGKT/S located at L4), switch-1 (Sw1: NxxSSR located at the β6-L9 junction), and switch-2 (Sw2: Walker B motif, DxxGxE located at the β7-L11 junction) undergo conformational changes during the ATPase cycle in response to the presence (e.g., ATP-bound state) or absence (e.g., ADP-bound or nucleotide-free/apo/rigor states) of the γ-phosphate. These structural changes are reciprocally related to–and thus modulate–the conformations of the neck linker/cover strand, and vice versa (Block 2007; Hwang et al. 2008; Khalil et al. 2008; Rice et al. 1999; Zhao et al. 2010). Third, a conserved motif called N-4 (consensus: RxxP) establishes interaction with the purine nucleotide base.

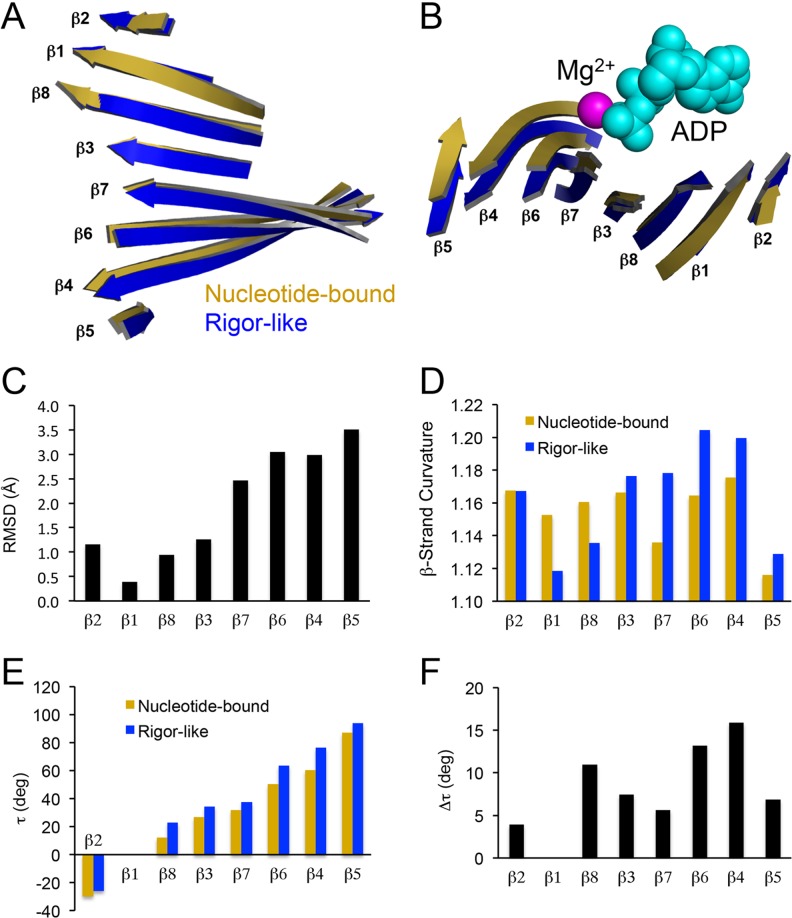

Central to the kinesin motor domain is an eight-stranded β-sheet (topology β2-β1-β8-β3-β7-β6-β4-β5; Fig. 3e) which serves as the core element that structurally connects the nucleotide-binding pocket and the microtubule-binding region. This central β-sheet has shown slightly variable degrees of right-handed twisting, which is thought to be important for the geometry and function of the motor domain (Kull and Endow 2013). Since most kinesins have been crystallized with bound nucleotide (Table 3), the degree of twisting has been very similar. However, recent crystal structures have demonstrated significant increases in right-handed twist or “over-twisting” of the kinesin β-sheet (Fig. 4; (Arora et al. 2014; Gigant et al. 2013), similar to the “over-twisting” seen in myosin’s β-sheet as it transitions from the nucleotide-bound state to the nucleotide-free state (Cecchini et al. 2008; Coureux et al. 2003; Reubold et al. 2003) [note: the “nucleotide-free” state has historically been called the “rigor” state since myosin binds very tightly to actin filaments in this nucleotide state]. The degree of “over-twisting” (τavg = 9.1 ± 4.3°; range 3.9–13.2°; Fig. 4f) observed in kinesins transitioning between the nucleotide-bound to nucleotide-free rigor states was comparable to that seen in myosin-V (τavg = 6.7 ± 4.8°; range 1–14°; Cecchini et al. 2008), which supports the hypothesis for common allosteric communication in cytoskeletal motors via the twisting of the central β-sheet. Indeed, theoretical studies on the origin of β-sheet twisting have demonstrated that the conformational energy associated with perturbing the structure of a β-sheet (through “twisting”, “bulging,” and “bending”) provide physical “reservoirs” of conformational free energy in globular proteins (Shamovsky et al. 2000a; Shamovsky et al. 2000b). Examination of the number of hydrogen bonds formed between residues of the central β-sheet reveals that five more hydrogen bonds are formed in the “under-twisted” nucleotide-bound state compared to the “over-twisted” rigor-like state, which amounts to 10–50 kJ mol-1 bond energy. This “stored” bond energy may provide the biophysical basis whereby kinesin motors can accelerate their rates of product release during their ATPase cycles (for more details, see the “Physics” section of this review). Interestingly, Hsp70 ATPases have also demonstrated nucleotide-dependent conformational changes in their central β-sheet (Zhuravleva et al. 2012; Zhuravleva and Gierasch 2011), suggesting this means of allosteric communication in proteins may be quite prevalent.

Fig. 4.

Structural changes in the eight-stranded central β-sheet of kinesin. Side (a) and end (b) views of the kinesin β-sheet after a nucleotide-bound structure (1BG2; Kull et al. 1996) was aligned with a rigor-like structure (4OZQ; Arora et al. 2014) using the main chain atoms of the P-loop. Mg2+ and ADP are shown as space-fill model and are colored magenta and cyan, respectively. c The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of complementary residues is plotted for each individual β-strand. d Individual β-strand curvature based on the sum of sequential Cα distances for each β-strand residue (i = initial residue, i + x = final residue) divided by the total distance from initial to final plotted for nucleotide-bound and rigor-like structures. e β-strand torsion angles (τ) relative to β1 are plotted to quantify the degree of twisting within the entire β-sheet. Torsion angles were calculated using the following equation for each individual β-strand: , where are the unit vectors for each respective β-strand (Cecchini et al. 2008). f The change in each individual β-strand torsion angle (Δτ) as the kinesin central β-sheet transitions from nucleotide-bound (1BG2) to rigor-like (4OZQ) states

Structural differences among kinesin members result in differences in the intrinsic rate and equilibrium constants that govern the ATPase cycle. Although the detailed structural mechanism of the nucleotide- and microtubule-driven conformational changes remains largely unknown, a current model exists for processive kinesins and is largely based on studies of kinesin-1. The nucleotide state at the active site is thought to trigger a conformational change that is transmitted to the adjacent microtubule-binding regions of the core. Communication between the active site and the microtubule binding region is achieved through two prominent structural pathways: (1) Sw1 to α3 to the β5-L8 lobe (Cochran et al. 2009; Ogawa et al. 2004) and (2) Sw2 to L11 to helix α4 to the remainder of the “Sw2 cluster” (Rice et al. 1999; Sindelar and Downing 2007; Vale and Milligan 2000). The Sw2 cluster also controls the orientation of the neck linker in alternate conformations that result in directed force production and motility stabilization (Gigant et al. 2013; Kikkawa et al. 2001). Cryo-electron microscopy (cyro-EM) studies have provided key insights into the conformational changes that kinesin motor domains undergo during their ATPase cycle, and recent advances in image processing algorithms have provided moderate/high resolution structures of these complexes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary for kinesin⋅microtubule interactions via cryo-electron microscopy methodologies

| Family | Name | PDB ID | Nucleotide | Notes | Resolution (Å) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | HsKHC | 2p4n | Free/Rigor | 9.0 | Sindelar and Downing 2007 | |

| RnKHC | 4atx | Free/Rigor | Dcxa; Pseudo model | 8.2 | Liu et al. 2012b | |

| Kinesin-3 | MmKIF1A | 2hxf | MgAMPPNP | 10.0 | Kikkawa and Hirokawa 2006 | |

| MmKIF1A | 2hxh | MgADP | 11.0 | Kikkawa and Hirokawa 2006 | ||

| MmKIF1A | 1ai0 | MgAMPPCP | 15.0 | Kikkawa et al. 2001 | ||

| Kinesin-5 | HsEg5/KSP | 4aqw | Free/Rigor | 9.5 | Goulet et al. 2012 | |

| HsEg5/KSP | 4aqv | MgAMPPNP | 9.7 | Goulet et al. 2012 | ||

| DmKLP61F | 2wbe | MgAMPPNP | KLP61F homology model | 9.4 | Bodey et al. 2009 | |

| Kinesin-10 | DmNOD | 3dco | Free/Rigor | 11.0 | Cochran et al. 2009 | |

| Kinesin-13 | DmKLP10A | 3j2o | Unknown | 10.8 | Asenjo et al. 2013 | |

| DmKIF2C | 3edl | MgAMPPNP | 28 | Tan et al. 2008 |

aDcx, Microtubule-associated protein called doublecortin

Family-specific motifs modulate the structural communication of various kinesins during their mechanochemical cycles. For example, L5 plays an important role during the kinesin ATPase cycle and has been the subject of several studies due to its location in the motor domain (it interrupts the long α2 helix immediately downstream of the P-loop; Fig. 3), variability in length across the superfamily (6–21 residues), and forming part of the binding pocket for various kinesin-5/Eg5 inhibitors (Brier et al. 2004; Kaan et al. 2010; Maliga et al. 2006; Talapatra et al. 2012; Yan et al. 2004). L5 wast proposed to first undergo conformational changes upon nucleotide binding during the kinesin-5 ATPase cycle (Cochran et al. 2005) and has since been found to function as a “conformational latch” to structurally and kinetically regulate its stepping behavior (Behnke-Parks et al. 2011; Parke et al. 2010; Waitzman et al. 2011). Specific interactions of the “microtubule-sensing latch” L7 with Sw1 and Sw2 have been implicated in the mechanism of MgADP product release from the active site of the kinesin-3 motor KIF1A (Nitta et al. 2008). For kinesin-13 motors, microtubule depolymerization activity relies on an extended L2 that contains the sequence “KVD” (also called the “KVD finger”), which has been shown to be necessary for microtubule depolymerization activity of these motors (Ogawa et al. 2004). This extended L2 is located within the conserved β-lobe near α6 (Fig. 3); however, the actual function of this β-lobe has remained elusive. The authors of a recent molecular dynamics simulation study aimed at investigating the role of this β-lobe in the mechanical stepping behavior in kinesin-1 suggested that it functions to amplify movements in the neck linker for processive motility (Geng et al. 2014).

Most kinesins walk along the microtubule lattice in a directional manner, either moving towards the plus-end or minus-end of the microtubule (Wade and Kozielski 2000). Traditionally, kinesins which have their motor domain located at the N-terminus of the heavy chain (i.e., N-class kinesins; e.g., kinesin-1) have shown plus-end directed motility, while kinesins with their motor domain located at the C-terminus (i.e., C-class kinesins; e.g., kinesin-14) have demonstrated minus-end directed motility. It was originally thought that directionality was caused by inherent differences in the structure of the motor domains of N-class and C-class kinesins (Henningsen and Schliwa 1997). However, crystal structures of the motor domains of kinesin-1 and kinesin-14 show very few structural differences (Kull et al. 1996; Sablin et al. 1996), while dimeric structures obtained through cryo-EM show significant differences in the orientation of the two motor domains relative to one another, with both having their unattached heads pointing in the direction they move along the microtubule (Arnal et al. 1996; Hirose et al. 1996; Kozielski et al. 1999; Sablin et al. 1998). Furthermore, dimeric chimeras with the motor core from kinesin-14 and stalk and neck regions from kinesin-1 show plus-end directed movement, despite the fact that the motor domains are from a minus-end directed motor (Henningsen and Schliwa 1997). Likewise, chimeras with the kinesin-1 motor core and kinesin-14 neck and stalk regions show minus-end motility (Endow and Waligora 1998). Taken together, these results suggest that directionality is determined primarily by structures outside the conserved motor core (Case et al. 1997).

The neck linker, which connects the motor core to the stalk, has been shown to reorient in response to the nucleotide state of the motor domain (Rice et al. 1999) and is thought to be responsible for positioning the detached motor head in the dimers towards either the plus- or minus-end of the microtubule, as seen in the dimeric structures of kinesin-1 and kinesin-14 (Rice et al. 1999). Additionally, mutant studies of kinesin-14 chimeras have also indicated that interactions between the neck region and the stalk are critical for maintaining minus-end directed movement. Mutant motors that lack critical core-interacting residues result in the slowing of kinesin-14 walking towards the plus-end of microtubules (Sablin et al. 1998). Disrupting the interaction between the neck linker and the motor domain in kinesin-1 also significantly impairs motility (Case et al. 2000), suggesting that interactions of the motor core with both the neck linker and neck region are responsible for determining directional movement. Lastly, the finding that kinesin-14 moves towards the plus-end of microtubules when interactions between the motor core and neck are interrupted suggests that the catalytic motor core inherently has an slight plus-ended directionality (Sablin et al. 1998), which in plus-ended motors is amplified by their neck linker and neck interactions, and in minus-ended motors is over-ridden by stronger interactions resulting in minus-directed movement.

Recently, the kinesin-5’s isolated from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Cin8p and Kip1p; Fridman et al. 2013; Gerson-Gurwitz et al. 2011; Roostalu et al. 2011; Thiede et al. 2012) and from Schizosaccharomyces pombe [Cut7p; (Edamatsu 2014)] have been shown to be able to switch directionality between slow plus-end movement to rapid minus-end movement. In vitro, the switch to plus-end directionality for both Cin8 and Kip1 can be induced by motor coupling when they bind two antiparallel microtubules or by decreasing the ionic strength. At high (physiological) ionic strength, or when on single microtubules, they act as rapid minus-end directed motors, while at low ionic strength, or when cross-linking two antiparallel microtubules, they act as slow plus-end directed motors. This ability for single kinesin motors to change directionality based on environmental conditions provides an opportunity to better understand the underlying factors that regulate directional movement of all members of the kinesin superfamily.

Kinesin motors are allosteric enzymes by nature. Therefore, amino acid residue substitutions in the motor domain can yield expected results, yet often produce unexpected or unpredicted pleiotropic effects (Table 5). Many different substitutions have been discovered in kinesin motors that have been implicated in diseases such as cancer (Rath and Kozielski 2012) or motor neuron degeneration [e.g., hereditary spastic paraplegia; (Ebbing et al. 2008; Fuger et al. 2012)]. As a general trend, but one not yet considered to be universal across all kinesin members, most tested substitutions lead to a reduced turnover number (k cat), altered binding affinity for microtubules, and slower in vitro microtubule gliding velocity (Table 5). Substitutions in the conserved active site motifs lead to drastically reduced (if not completely abolished) ATPase activity, whereas substitutions in adjacent loops involved in the structural communication pathways between the active site and the microtubule binding region lead to disruption of allosteric regulation of the motor. Recently, the conserved switch-1 serine residue that physically interacts with the divalent metal ion in the active site was substituted with a cysteine; this rendered several kinesin family members inactive with Mg2+ but swapping metals with Mn2+ led to the restoration of activity (Cochran et al. 2011). Interestingly, single substitutions in the neck of kinesin-14 leads to bidirectional motility (Endow and Higuchi 2000), which should shed light on how the yeast kinesin-5 motors (Cin8p, Kip1p, and Cut7p) show directionality switching behavior (Fridman et al. 2013; Gerson-Gurwitz et al. 2011; Roostalu et al. 2011; Thiede et al. 2012). Despite the numerous residue substitutions that have been characterized, researchers still have only scratched the surface for using site-specific mutagenesis techniques to probe kinesin structure and function.

Table 5.

Residue Some of the WT sequence is in bold. Should the bold font not be explained in a footnote? substitutions in kinesin motor domain with reported effects relative to the respective WT construct

| Family | Name | Substitution | WT Sequence | Structure | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | HsKHC | R14A | MCRFR | β1/N-4 | R14A/R14A homodimer; 35-fold tighter K m; 18-fold slower k cat; 18-fold slower gliding V obs | Kaseda et al. 2003 |

| R14A | MCRFR | β1/N-4 | WT/R14A heterodimer; 2-fold tighter K m; 9-fold slower k cat; 8-fold slower gliding V obs; similar stall force | Kaseda et al. 2003 | ||

| D140A | YLDKI | L7 | 3.5-fold tighter K m; 1.7-fold slower k cat; 1.8-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| K141A | LDKIR | L7 | 1.8-fold weaker K m; 1.1-fold faster k cat; 1.1-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| K159A | EDKNR | L8 | 2.3-fold weaker K m; similar k cat; 1.3-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| E170A | CTERF | L8 | 2.6-fold tighter K m; 1.2-fold slower k cat; 1.6-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| S202C | HSSRS | L9/Sw1 | 10-fold slower MgATPase; similar MnATPase; 100-fold slower MgATP gliding V obs; 10-fold slower MnATP gliding V obs | Cochran et al. 2011 | ||

| E236A | GSEKV | L11/Sw2 | No MT gliding; >1000-fold slower k cat; similar ATP binding kinetics; increased ADP release kinetics; can take one ATP-dependent step | Rice et al. 1999 | ||

| K240A | VSKTG | L11 | 4.2-fold weaker K m; similar k cat; 1.6-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| L248A | AVLDE | L11 | 3.1-fold weaker K m; 1.3-fold slower k cat; 1.1-fold faster gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| E250A | LDEAK | L11 | 1.9-fold tighter K m; 1.3-fold slower k cat; 1.8-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| K252A | EAKNI | α4 ext. | 4.4-fold weaker K m; 2.7-fold slower k cat; 1.1-fold faster gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| K256A | INKSL | α4 | 2.9-fold weaker K m; 1.4-fold slower k cat; similar gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| E270A | LAEGS | L12 | 2.1-fold tighter K m; 1.1-fold faster k cat; 1.1-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| Y274A | STYVP | L12 | 3.2-fold weaker K m; 1.3-fold slower k cat; 1.2-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| R278A | PYRDS | L12 | 15.5-fold weaker K m; 1.5-fold slower k cat; 1.3-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| D279A | YRDSK | L12 | 2.3-fold tighter K m; 1.3-fold slower k cat; 1.2-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| K281A | DSKMT | L12/α5 | 2.4-fold weaker K m; 1.1-fold slower k cat; 1.2-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| R284A | MTRIL | α5 | 2.2-fold weaker K m; 2.3-fold slower k cat; 1.1-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| E311A | ESETK | α6 | 3.1-fold tighter K m; 2.9-fold slower k cat; 3.2-fold slower gliding V obs | Woehlke et al. 1997 | ||

| W340F | EQWKK | Neck | Similar k cat; 4-fold tighter K 0.5,MT; Cys-light K413-C333 construct | Rosenfeld et al. 2001 | ||

| DmKHC | T94S | GQTSS | L4/P-loop | 3.6-fold faster basal ADP release; 1.8-fold faster MT-stimulated ADP release; 3.3-fold slower MT gliding V obs; similar stall force | Higuchi et al. 2004 | |

| E164A | VHEDK | β5a/L8 | 4.2-fold slower k cat; 4-fold faster ATP hydrolysis; no observed MT dissociation; 2–3-fold slower ADP release | Klumpp et al. 2004a; Klumpp et al. 2004b; Klumpp et al. 2003 | ||

| E164K | VHEDK | β5a/L8 | 3-fold slower k cat; 2-fold faster ATP hydrolysis; 3–4-fold slower ADP release | Klumpp et al. 2004a; Klumpp et al. 2004b | ||

| E164N | VHEDK | β5a/L8 | 2.6-fold slower k cat; 3-fold faster MT dissociation; 3-fold slower MT association; 2–3-fold slower ADP release | Klumpp et al. 2004a | ||

| E164D | VHEDK | β5a/L8 | 1.5-fold slower k cat; 4-fold faster MT dissociation | Klumpp et al. 2004a | ||

| E164Q | VHEDK | β5a/L8 | 1.4-fold slower k cat; 3-fold faster MT dissociation; 2-fold slower MT association; 2-fold slower ADP release from both heads | Klumpp et al. 2004a | ||

| D165A | HEDKN | β5a/L8 | 1.7-fold slower k cat; 1.5-fold slower ADP release | Klumpp et al. 2004a | ||

| R210A | SSRSH | L9/Sw1 | >500-fold slower ATP hydrolysis; 350-fold slower k cat; 12–25-fold slower MT association; 5–6-fold slower ADP release from both heads | Farrell et al. 2002 | ||

| R210K | SSRSH | L9/Sw1 | >800-fold slower ATP hydrolysis; 350-fold slower k cat; 1.3-fold slower MT association; processive motility by WT/R210K heterodimer | Klumpp et al. 2003; Thoresen and Gelles 2008 | ||

| T291M | KLTRI | α5 | 3.8-fold slower MT gliding V obs; 2.5-fold weaker K m; 4-fold weaker K 0.5,MT; 2.5-fold faster ATP hydrolysis; 3-fold faster MT dissociation | Brendza et al. 1999; Brendza et al. 2000 | ||

| RnKHC | E200A | MNEHS | L9/Sw1 | 1.4-fold slower k cat; 5–10-fold slower MT-stimulated ADP release | Auerbach and Johnson 2005b | |

| E200D | MNEHS | L9/Sw1 | 1.7-fold slower k cat; 2-fold faster mantATP binding; 4.3-fold slower MT-stimulated mantADP release | Auerbach and Johnson 2005b | ||

| E237A | GSEKV | L11/Sw2 | >400-fold slower k cat; >500-fold faster basal ADP release; 3–4-fold slower MT-stimulated ADP release | Auerbach and Johnson 2005b | ||

| E237D | GSEKV | L11/Sw2 | 9.1-fold slower k cat; 2.7-fold slower ATP binding; 4.4-fold slower MT-stimulated ADP release | Auerbach and Johnson 2005b | ||

| N256K | NINKS | α4 ext. | 133-fold slower k cat; 1.3-fold faster ATP binding; 400–500-fold slower MT-stimulated ADP release | Auerbach and Johnson 2005b | ||

| MmKIF5C | V240Q/S241K | EKVSKT | L11 | Double substitution; similar k cat; ~2-fold weaker K 0.5,MT | Chang et al. 2013 | |

| S258G | NKSLS | α4 | 2-fold faster k cat; 10-fold weaker K 0.5,MT | Chang et al. 2013 | ||

| GDDKKG | AEGTK | L12 | Chimeric construct; 2-fold faster k cat; 1.6-fold tighter K 0.5,MT; 3.4-fold increase in k cat/K 0.5,MT | Chang et al. 2013 | ||

| Kinesin-3 | MmKIF1A | E148A | YMEIY | β4 | 37-fold slower k cat; 2.9-fold slower basal ATPase | Nitta et al. 2008 |

| Y150F | EIYCE | β4/L7 | 5.3-fold slower k cat; 2.1-fold slower basal ATPase | Nitta et al. 2008 | ||

| E152A | YCERV | L7 | 11.5-fold slower k cat; 8.1-fold tighter K 0.5,MT; >7-fold faster MT-stimulated ADP release; 1.5-fold slower basal ATPase | Nitta et al. 2008 | ||

| R153A | CERVR | L7/β5 | 2.4-fold slower k cat; similar basal ATPase | Nitta et al. 2008 | ||

| K161A/R167A R169A/K183A |

L8 | Quadruple substitution; 6-fold weaker K d,MT with AMPPNP; 3.9-fold weaker K d,MT with ADP | Nitta et al. 2004 | |||

| R203A | KARTV | α3 | 15-fold slower k cat; 3.3-fold slower basal ATPase | Nitta et al. 2008 | ||

| R216A | SSRSH | L9/Sw1 | 240-fold slower k cat; 8.3-fold slower basal ATPase | Nitta et al. 2008 | ||

| D248A | LVDLA | β7/Sw2 | 1670-fold slower k cat; 3.1-fold slower basal ATPase | Nitta et al. 2008 | ||

| K261A/R264A/ K266A |

L11 | Triple substitution; 4.8-fold weaker K d,MT with AMPPNP; 1.8-fold weaker K d,MT with ADP | Nitta et al. 2004 | |||

| E267A | LKEGA | α4 ext. | 22-fold slower k cat; 5.6-fold slower basal ATPase | Nitta et al. 2008 | ||

| GTKT | MDSGPNKN(K)6TD | L12 | Chimeric construct; 3.5-fold weaker K d,MT with ADP; 3.8-fold weaker K d,MT with ATP; 7.8-fold weaker K d,MT with ADP + VO4 | Nitta et al. 2004 | ||

| Kinesin-4 | MmKIF4A | Q248V/K249S | ERQKKT | L11 | Double substitution; Slightly increased k cat and K 0.5,MT; similar k cat/K 0.5,MT | Chang et al. 2013 |

| G267S | NRGLL | α4 | Slightly decreased k cat and K 0.5,MT; similar k cat/K 0.5,MT | Chang et al. 2013 | ||

| AEGTK | GDDKKG | L12 | Chimeric construct; 2-fold decreased k cat; similar K 0.5,MT; 2.3-fold decrease in k cat/K 0.5,MT | Chang et al. 2013 | ||

| Kinesin-5 | HsEg5 | P121A | RSPNE | L5 | 2-fold slower neck-linker isomerization; 4.3-fold slower ADP binding; 5.1-fold slower ADP release | Behnke-Parks et al. 2011 |

| P131A | EDPLA | L5 | 50-fold slower ATP binding; 5-fold slower neck-linker isomerization; 7.7-fold slower ADP release; 3.5-fold slower MT dissociation | Behnke-Parks et al. 2011 | ||

| S233C | YSSRS | L9/Sw1 | 5–6-fold slower MgATPase; similar MnATPase; ATP hydrolysis slowed for MgATPase; similar ATP binding and ADP release kinetics | Cochran et al. 2011 | ||

| R234K | SSRSH | L9/Sw1 | 125-fold slower ATP hydrolysis; 10-fold faster MT association; similar AMPPNP binding affinity | Zhao et al. 2010 | ||

| SC/RK | YSSRSH | L9/Sw1 | Double substitution; similar ATP binding; complete loss of ATP hydrolysis | Krzysiak et al. 2008; Zhao et al. 2010 | ||

| Kinesin-10 | DmNOD | S203C | NSSRS | L9/Sw1 | ~20-fold slower basal MgATPase; similar basal MnATPase | Cochran et al. 2011 |

| Kinesin-13 | MmKIF2C | K293A | KLKVD | L2 | ~50 % MT depolymerization activity | Ogawa et al. 2004 |

| V294A | LKVDL | L2 | ~55 % MT depolymerization activity | Ogawa et al. 2004 | ||

| D295A | KVDLT | L2 | ~65 % MT depolymerization activity | Ogawa et al. 2004 | ||

| K293A/V294A/ D295A |

L2 | Triple substitution; ~35 % MT depolymerization activity | Ogawa et al. 2004 | |||

| G489A | LAGNE | L11/Sw2 | Defective in tubulin detachment; very slow ATP hydrolysis | Wagenbach et al. 2008 | ||

| E491A | GNERR | L11/Sw2 | Defective in tubulin detachment; 20-fold tighter K d,tubulin; catalytically depolymerizes MTs in ADP | Wagenbach et al. 2008 | ||

| PfKINI | K40A/V41A/ D42A |

L2 | Triple substitution; 10-fold reduction in MT depolymerization; ~10-fold slower MT-stimulated k cat; similar tubulin-stimulated k cat | Shipley et al. 2004 | ||

| R242A | SERGA | L11 | ~2-fold reduction in MT depolymerization; ~2-fold slower MT-stimulated k cat; ~3-fold slower tubulin-stimulated k cat | Shipley et al. 2004 | ||

| D245A | GADTV | L11 | Similar MT depolymerization; ~1.5-fold faster MT-stimulated k cat; ~1.2-fold faster tubulin-stimulated k cat | Shipley et al. 2004 | ||

| K268A/E269A/ C270A |

α4 | Triple substitution; no MT depolymerization; ~20-fold slower MT-stimulated k cat; ~4-fold slower tubulin-stimulated k cat | Shipley et al. 2004 | |||