Abstract

Protein concentration data are required for understanding protein interactions and are a prerequisite for the determination of affinity and kinetic properties. It is vital for the judgment of protein quality and for monitoring the effect of therapeutic agents. Protein concentration values are typically obtained by comparison to a standard and derived from a standard curve. The use of a protein standard is convenient, but may not give reliable results if samples and standards behave differently. In other cases, a standard preparation may not be available and has to be established and validated. Using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors, an alternative concentration method is possible. This method is called calibration-free concentration analysis (CFCA); it generates active concentration data directly and without the use of a standard. The active concentration of a protein is defined through its interaction with its binding partner. This concentration can differ from the total protein concentration if some protein fraction is incapable of binding. If a protein has several different binding sites, active concentration data can be established for each binding site using site-specific interaction partners. This review will focus on CFCA analysis. It will reiterate the theory of CFCA and describe how CFCA has been applied in different research segments. The major part of the review will, however, try to set expectations on CFCA and discuss how CFCA can be further developed for absolute and relative concentration measurements.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12551-016-0219-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: SPR, CFCA, Protein quality, Vaccine, Biomarker, Simulation

Introduction

General

Proteins are complex molecules involved in catalysis and signaling, and serve as building blocks in cells. They often function in networks, and a single protein may interact with several other biomolecules. Protein expression may differ in health and disease, and specific proteins have been identified as biomarkers, i.e., as indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to therapeutic intervention. Antibodies are generated for the detection of biomarkers and both antibodies and vaccines are designed for the treatment or prevention of a range of diseases. Clearly, correct estimates of protein activity and concentration will be important for obtaining a better insight into protein function.

The first time a protein is expressed, no standard preparation is available. An immune response can differ from one animal to another or from one person to another, and it may be difficult or even impossible to identify a specific IgG that can be used as a common standard. Commercial research reagents may not always show the expected activity, and this may impact the quality and cost of research (Baker 2015). It is in situations like these that calibration-free concentration analysis (CFCA) can make an impact, as it has the potential to measure active concentrations without the use of a standard.

Theoretical background to CFCA

With surface plasmon resonance (SPR) detection, the binding of an analyte (A) to its immobilized interaction partner (B) can be monitored directly without the use of labels (Jönsson et al. 1991). In Biacore systems, the analyte is injected over the sensor surface under conditions of laminar flow (Sjoelander and Urbaniczky 1991), and the SPR response has been shown to correlate with changes in mass on the sensor surface (Stenberg et al. 1991).

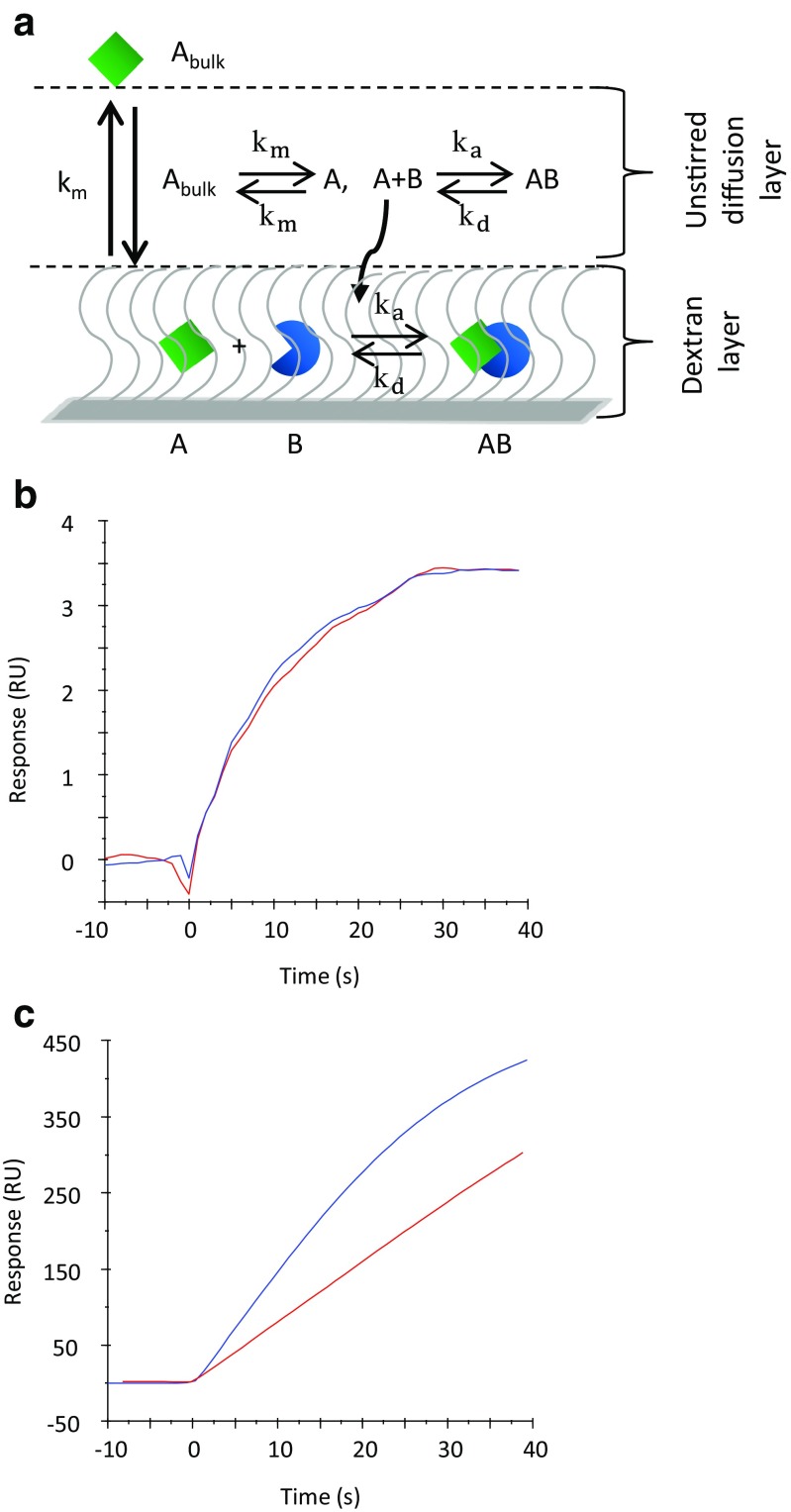

CFCA methodology on the Biacore platform has been developed gradually from early concepts (Karlsson et al. 1993), to broader applicability (Christensen 1997) to incorporate the use of global analysis of concentration series (Sigmundsson et al. 2002). Binding events are generally described by a two-compartment model (Myszka et al. 1998), where transport of analyte to the sensor surface and binding at the sensor surface are regarded as linked processes, as illustrated in Fig. 1a.

Fig. 1.

Transport and binding of analyte to a sensor surface. a Analyte (square) in solution enters an unstirred diffusion layer. A transport coefficient (km) describes transport across the diffusion layer to the sensor surface, where the analyte binds to its ligand (circle segment). Binding rates are defined by analyte and ligand concentrations and rate constants ka and kd. b, c Binding curves observed for β2μglobulin (100 nM) injected at flow rates of 5 (red curve) and 100 (blue curve) μL/min. b 142 RU of anti-β2μglobulin immobilized to sensor chip CM5: transport-independent binding. c 7150 RU of anti-β2μglobulin immobilized to sensor chip CM5: transport-dependent binding

The height of the depletion layer depends on the flow rate, and is reduced at high flow rates. The balance between transport and kinetic rates can be further controlled by altering the immobilization level. For the same interaction, the shape of the binding curves can differ dramatically and depend on the experimental conditions. With low immobilization levels (Fig. 1b), binding curves can be expected to reflect the kinetics of the interaction, and binding rates do not depend on the flow rate. Transport effects are negligible, and the surface concentration is identical to the bulk concentration of the sample. At high immobilization levels (Fig. 1c), transport effects can be significant, and binding curves become flow rate-dependent. In parallel, the time to reach a steady state is prolonged. In this situation, the concentration at the sensor surface varies with the flow rate, and is lower than the bulk concentration.

Kinetic analysis and CFCA share theoretical concepts, but differ in the way data are generated and analyzed (Pol et al. 2016). CFCA analysis is focused on initial binding rates, and requires that the transport coefficient can be pre-calculated and used as a constant during data analysis. CFCA also requires that the interaction is probed with two flow rates.

By fitting binding data to the one-to-one interaction model, the concentration of the analyte can then be determined.

This differentiates CFCA from kinetic analysis, where the concentration has to be entered as a constant and the transport coefficient is calculated during the fitting procedure, along with the rate constants.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to simultaneously fit analyte concentrations and the transport coefficient, as these parameters cannot be resolved from each other.

Applications

CFCA has been used in a number of situations (Table 1) including: quality control of protein reagents, to measure the effect of modification or stress on protein activity, to establish a standard for concentration assays, to validate kinetic analysis, for batch-to-batch control of biotherapeutics, to guide purification procedures, for the analysis of vaccine constructs, for the determination of antibody response in vaccine studies, and for biomarker analysis.

Table 1.

Applications and references

| Application | References | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For quality control of protein reagents | Richalet-Sécordel et al. (1997): Concentration measurement of unpurified proteins using biosensor technology under conditions of partial mass transport limitation | Zeder-Lutz et al. (1999): Active concentration measurements of recombinant biomolecules using biosensor technology | Sissoeff et al. (2005): Stable trimerization of recombinant rabies virus glycoprotein ectodomain is required for interaction with the p75NTR receptor | |||||

| To measure the effect of modification or stress on protein activity | Kubetzko et al. (2005): Protein PEGylation decreases observed target association rates via a dual blocking mechanism | Fant et al. (2007): Calibration-free concentration analysis in the development of therapeutic proteins | Hensel et al. (2011): Identification of potential sites for tryptophan oxidation in recombinant antibodies using tert-butylhydroperoxide and quantitative LC-MS | Watanabe et al. (2013): Structure-based histidine substitution for optimizing pH-sensitive Staphylococcus protein A | Pille et al. (2013): General strategy for ordered noncovalent protein assembly on well-defined nanoscaffolds | |||

| To establish a standard for concentration assays | Choulier et al. (2010): A peptide-based fluorescent ratiometric sensor for quantitative detection of proteins | Pissani (2012): HIV vaccine design based on in vivo evolution of quasispecies envelope proteins | ||||||

| To validate kinetic analysis | Allignet et al. (2002): Several regions of the repeat domain of the Staphylococcus caprae autolysin, AtlC, are involved in fibronectin binding | Pol (2010): The importance of correct protein concentration for kinetics and affinity determination in structure–function analysis | Plummer (2012): Evidence of human endogenous retrovirus K involvement in human cancer | Bee et al. (2012): Exploring the dynamic range of the kinetic exclusion assay in characterizing antigen–antibody interactions | Bee et al. (2013): Determining the binding affinity of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies towards their native unpurified antigens in human serum | Abdiche et al. (2015): The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) binds independently to both sites of the IgG homodimer with identical affinity | Visentin et al. (2016): Calibration free concentration analysis by surface plasmon resonance in a capture mode | Behr et al. (2016): Insights into the DNA-binding mechanism of a LytTR-type transcription regulator |

| For batch-to-batch control of biotherapeutics | Fant et al. (2007): Calibration-free concentration analysis in the development of therapeutic proteins | Pol et al. (2016): Evaluation of calibration-free concentration analysis provided by Biacore™ systems | ||||||

| To guide purification procedures | Application note 29-1154-78, 2014: Accurate comparability assessment of a biosimilar interferon in process development | |||||||

| For the analysis of vaccine constructs | Westdijk et al. (2011): Characterization and standardization of Sabin based inactivated polio vaccine: Proposal for a new antigen unit for inactivated polio vaccines | Ten Have et al. (2015): Trypsin diminishes the rat potency of polio serotype 3 | ||||||

| For the determination of antibody response in vaccine studies | Pol et al. (2007): Biosensor-based characterization of serum antibodies during development of an anti-IgE immunotherapeutic against allergy and asthma | Williams et al. (2012): Enhancing blockade of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion: assessing combinations of antibodies against PfRH5 and other merozoite antigens | Voepel et al. (2014): Malaria vaccine candidate antigen targeting the pre-erythrocytic stage of Plasmodium falciparum produced at high level in plants | Boes et al. (2015b): Analysis of a multi-component multi-stage malaria vaccine candidate—tackling the cocktail challenge | Boes et al. (2015a): Detailed functional characterization of glycosylated and nonglycosylated variants of malaria vaccine candidate PfAMA1 produced in Nicotiana benthamiana and analysis of growth inhibitory responses in rabbits | Spiegel et al. (2015): The stage-specific in vitro efficacy of a malaria antigen cocktail provides valuable insights into the development of effective multi-stage vaccines | Boes et al. (2016): Analysis of the dose-dependent stage-specific in vitro efficacy of a multi-stage malaria vaccine candidate cocktail | |

| For biomarker analysis | Ray et al. (2015): Proteomic analysis of Plasmodium falciparum induced alterations in humans from different endemic regions of India to decipher malaria pathogenesis and identify surrogate markers of severity | Shah et al. (2015): Calibration-free concentration analysis of protein biomarkers in human serum using surface plasmon resonance | ||||||

Sample matrixes range from pure buffer systems to diluted serum samples. For “absolute” concentration data, the binding model assumes that the interaction proceeds as a one-to-one interaction, but real-life applications include examples where avidity and/or heterogeneity contributes to the response. In such cases, the resulting data are interpreted as relative concentrations, or CFCA data are regarded as an empirical value that can be correlated to other effects. Examples of relative analysis include comparison of stressed and wild-type protein (Hensel et al. 2011), comparison of alkaline tolerance of protein A constructs (Watanabe et al. 2013), or batch-to-batch comparisons (Pol et al. 2016). CFCA data have been successfully correlated to growth inhibition in vaccine development (Spiegel et al. 2015) and for the identification of biomarkers (Ray et al. 2015; Shah et al. 2015).

Reliability of CFCA

The transport coefficient

In contrast to kinetic analysis, which has benefitted from increased sensitivity of SPR systems, CFCA has received less attention from developers and from the user community. This is surprising, as CFCA can potentially be developed to an absolute concentration method. For this, a detailed understanding of the transport coefficient is necessary (Pol et al. 2016). By examining the parameters in the transport coefficient, it is possible to estimate the repeatability and accuracy of CFCA measurements. The transport coefficient can also be used to calculate the degree of mass transport limitation (MTL). With this, it may be possible to predict under which circumstances CFCA can be successfully applied.

| 1 |

The transport coefficient, kt, includes parameters (Table 2) that reflect the design of the Biacore system, the flow rate, a factor for the conversion of RU to surface concentration, the molecular weight, and the diffusion coefficient of the analyte.

Table 2.

Parameters in the transport coefficient, kt

| Parameters | Biacore-specific data | |

|---|---|---|

| α | Distance from the flow cell inlet to the center of the detection spot (m) | 1.28*10−3 |

| β | Detection spot length (m) | 1.80*10−3 |

| D | Diffusion coefficient (m2·s) | |

| F | Volumetric flow rate (m3·s−1) | |

| h | Flow cell height (m) | 4*10−5 |

| Mw | Molecular weight (g·mole−1) | |

| w | Flow cell width (m) | 5.00*10−4 |

Note that Biacore-specific data vary for different instruments and flow cell designs. The values provided here are relevant for the Biacore T200 flow cell FC 2–1 configuration

The conversion factor is not explicitly seen in the final expression, but it is assumed that 1 RU is 10−6 g·m−2 (Stenberg et al. 1991).

Biacore-specific data vary between different versions of Biacore systems. The Biacore=specific data provided in Table 2 are nominal values for an injection in flow cell FC 2–1 in Biacore T200 systems. The height and width are properties of the flow system and the integrated fluidic cartridge (IFC). The distance from the inlet to the center of the detection spot depends on the angle of incident light and on the thicknesses of the optointerface and the glass on the sensor chip. The length of the detection spot is given by the optical settings.

Simulation and re-evaluation of data

Simulations of data using kinetic models were performed using the “fit simulate curves” function in BIAevaluation software v4.1.1 available from GE Healthcare. Re-evaluation of data was performed with the same software, to which the CFCA model was entered using the “fit/edit models” function.

All rate equations are presented in the Supplementary data.

The degree of MTL

The degree of MTL can be obtained from the following relation (de Mol and Fischer 2008; Pol et al. 2016):

| 2 |

This expression scales transport (kt) and binding (ka*Rmax) rates.

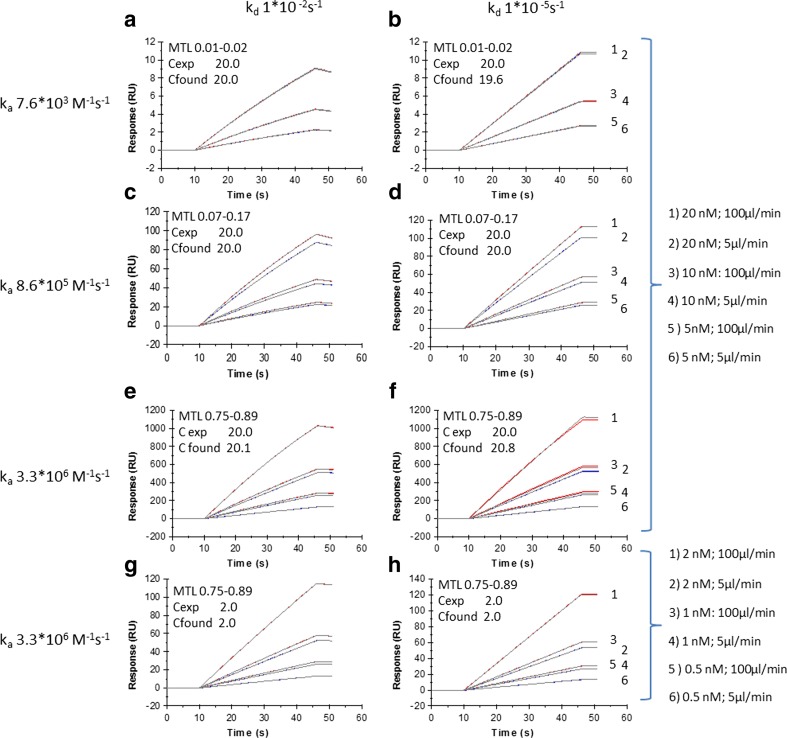

Christensen (1997) used simulation and re-analysis of binding data, and showed that accurate concentrations could be obtained with MTL as low as 0.2. They derived concentrations using binding rates rather than full binding curves. Figure 2 shows simulated and re-evaluated data (for the rate equations, see the Supplementary data) using whole binding curves.

Fig. 2.

Impact of the degree of mass transport limitation (MTL) on calibration-free concentration analysis (CFCA) data. Overlay plot of simulated and fitted data. Data were simulated for a one-to-one interaction with Rmax of 2000 RU, kd values of 1*10−2 s−1 (a, c, e, g) and 1*10−5 s−1 (b, d, f, h). Flow rates were 5 and 100 μL/min and the kt value at 1 μL/min was 4.88*108 RU*M−1*s−1. ka varied and was 7.6*103 M−1s−1 (a, b), 8.6*105 M−1s−1 (c, d), and 3.3*106 M−1s−1 (e, f, g, h). Analyte concentrations were 5, 10, and 20 nM (a–f) and 0.5, 1, and 2 nM (g, h). Each curve is identified by the scale to the right and this scale is applicable to both left and right sensorgram panels. As simulated and re-evaluated data are shown in an overlay plot, each subfigure contains 12 sensorgrams. In Fig. 2a, b, only three curves are visible, as data obtained with flow rates of 5 and 100 μL/min overlap almost completely. The resulting binding curves were re-analyzed using the CFCA model, which includes a dilution factor to allow for global analysis of a concentration series. The insert shows the degree of MTL calculated with Eq. 2, together with the expected Cexp (used in simulations) and found Cfound (determined by the CFCA algorithm) concentrations in nM

Data were simulated with varying ka, kd, and concentration values, as shown in Fig. 2. The maximum binding capacity was set to 2000 RU, and a kt value at 1 μL/min of 4.88*108 RU*M−1*s−1 was used in the simulations. This kt value was obtained using an Mw of 150 kDa and a diffusion coefficient of 4.0*10−11 m2/s as inputs (Eq. 1) to mimic antibody experiments described by Pol et al. (2016).

Each subfigure in Fig. 2 contains 12 sensorgrams; six simulated sensorgrams and the corresponding fits. In Fig. 2a, b, binding curves at 5 and 100 μL/min overlap almost completely, with very little influence of mass transport. In Fig. 2c–h, where higher association rate constants are used, transport effects become visible and binding curves obtained at 5 and 100 μL/min start to spread out. In all cases, simulated curves (red for 100 μL/min and blue for 5 μL/min) and fitted curves (gray) appear tightly together. The fitting procedure takes all dilutions into account and returns one concentration value that corresponds to that of the undiluted sample. The fitted concentrations agree with concentrations used in simulation and differences in kd values do not impact the results.

Clearly, binding curve analysis confirms the findings of Christensen, and demonstrates that CFCA analysis can be expected to return correct concentrations at very low degrees of MTL. The simulations further indicate that CFCA will be possible for interactions with dissociation rate constants, at least in the range from 10−2 to 10−5 s−1. The analysis requires the use of two flow rates for accurate analysis of transport effects and simulated data cannot be retrieved if only one flow rate is used.

These simulations are in contrast to the experimental data from Pol et al. (2016), where concentration values obtained at varying degrees of MTL differed, and increased with 30 to 50 % as immobilization levels and the degree of MTL dropped. This trend was observed for analytes in the molecular weight range from 430 Da to 150 kDa, and with diffusion coefficients from 4.0*10−11 m2/s to 3.7*10−10 m2/s. Interestingly, experimental data reported by Visentin et al. (2016) showed consistent concentrations for HLA-A and antibody samples, irrespective of the degree of MTL that ranged from 0.1 to 0.4. To obtain more insight into these findings, it may be useful to look into the repeatability and accuracy of CFCA, and factors that influence them.

Repeatability

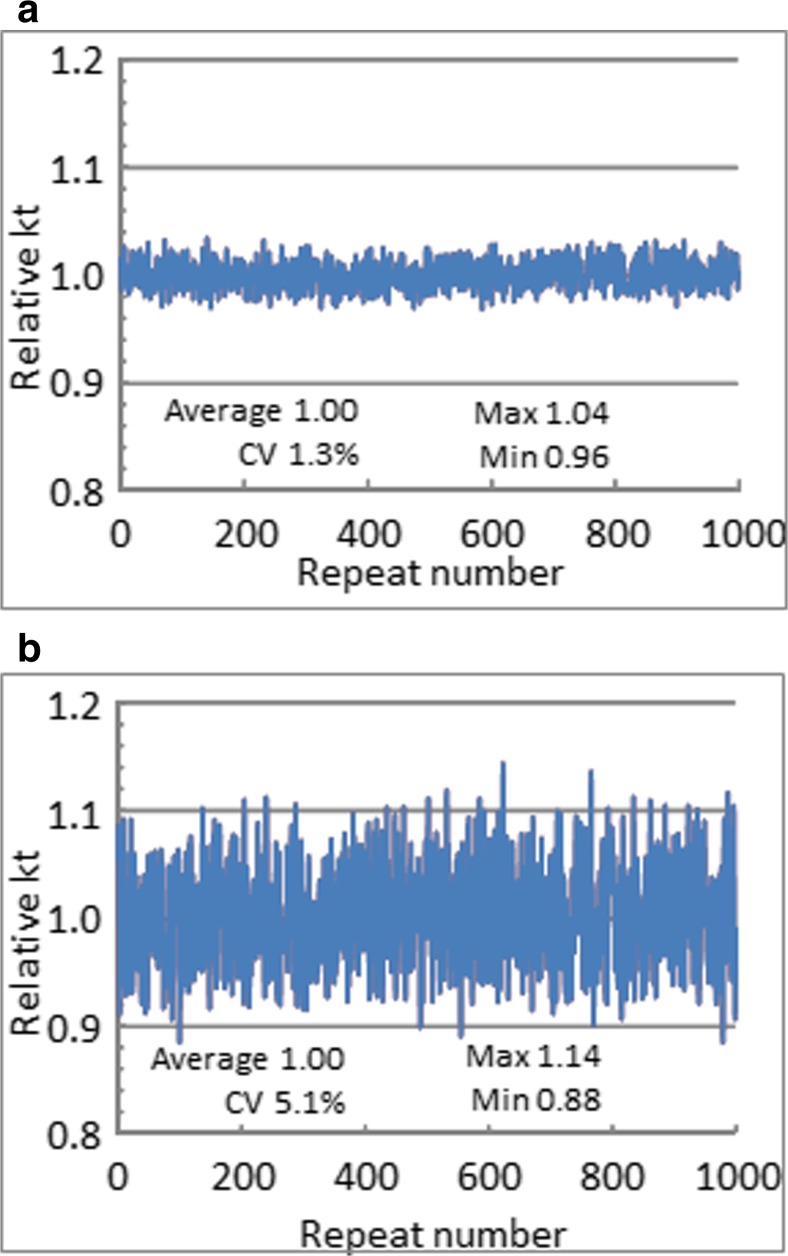

By using the randbetween function in Microsoft™ Excel™, the influence of system parameters on assay repeatability were estimated by assigning a percentage error to each parameter and calculating kt for 1000 random settings (Fig. 3). These kt values were compared to nominal kt values.

Fig. 3.

Predicted variation in kt values. Error spaces were assigned to the nominal values of the height and width of the flow cell, the flow rate, the distance to the detection center spot, and the detection spot length. a Variation over time in one Biacore system. b Hypothetical variation between 1000 Biacore systems. The text in each figure shows the average, relative standard deviation (%CV), and maximum and minimum values

With errors of 1 % for height, width, and detection spot length, and 3 % in flow rate (5 or 100 μL/min) and distance from the flow cell inlet to the center of the detection spot (Fig. 3a), the coefficient of variation, CV, in kt was 1.3 %. This value can be compared to a response CV of 1.34 % obtained with 1000 repeat injections of hIgG over a surface with immobilized anti-human IgG antibody (Kärnhall 2011). As the experimental data include chemical noise (stability of reagents and sensor chips), it can be assumed that system parameters which influence kt are very stable during a run.

The situation is somewhat different when 1000 Biacore systems are compared, as IFCs, pumps, optointerfaces, and optical settings are unique to each system (Fig. 3b). To mimic 1000 Biacore system, errors of 5 % for height, width, detection spot length, and flow rate, and 15 % error for the distance from the flow cell inlet to the center of the detection spot were assumed. With these settings, the CV in kt increases to just over 5 %, with a min/max range of approximately +/− 15 %.

Accuracy

The conversion from RU to mass assumes that one RU corresponds to a mass increase on the sensor surface of 10−6 g·m−2. This conversion factor was obtained by using radioactively labeled proteins (Stenberg et al. 1991). In these experiments, proteins were bound to a carboxymethylated dextran sensor surface by electrostatic forces. The protein sample was re-circulated until a steady state was reached, and then transferred to a scintillation counter.

Binding experiments are very different. A ligand is already immobilized when the analyte is injected, and the distribution of the analyte in the dextran matrix may not be known. Different binding scenarios are illustrated in Fig. 4.

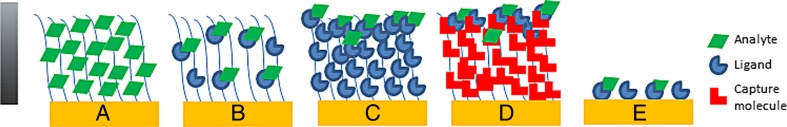

Fig. 4.

Hypothetical distribution of analyte on sensor surfaces and in the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) evanescent field. a Electrostatical attraction of analyte to carboxymethylated dextran. b Binding of analyte to ligand immobilized to a low level. c Binding of analyte to ligand immobilized to a high level. d Immobilization of capture molecule to a high level, followed by capture of ligand and binding of analyte. e Binding of analyte to ligand immobilized on a surface without dextran matrix. The gray bar illustrates that the strength of the SPR signal is reduced with increasing distance from the gold surface

Figure 4a corresponds to the radioactivity experiment, where the protein was found to be evenly distributed in the matrix. In Fig. 4b, a low immobilization level is used and the analyte is distributed throughout the dextran matrix. In Fig. 4c, a high immobilization level is used. Here, most of the analyte is assumed to remain at the top of the immobilized layer, as diffusion into the matrix may be prevented. In Fig. 4d, a capture approach is used. The capturing agent is immobilized to a high degree and the ligand is bound on top of the capturing agent. The analyte is again assumed to remain at the top of the sensor surface. In Fig. 4e, the ligand is immobilized to a flat surface without a dextran matrix and the analyte binds to the immobilized ligand.

When these scenarios are considered in view of the evanescent field strength at the SPR angle (Stenberg et al. 1991), it is clear that the highest response per mass unit will be obtained on the flat surface. The intensity of the SPR signal decays exponentially with increasing distance from the sensor surface. In Biacore systems, the effective penetration depth, where the field strength is reduced to 1/e (0.37), is close to 150 nM, and the field strength is almost twice as high at the surface compared to 100 nm away from the surface. The difference in response per mass unit is, thus, approximately two-fold when scenarios with protein binding to the top of the dextran matrix are compared with binding to a 2D surface without a dextran matrix. Consequently, the response per mass unit will be lower in the scenarios in Fig. 4c, d, where mass is accumulated at the top of the surface compared to the scenarios in Fig. 4a, b, where protein is distributed within the dextran matrix.

The experimental setup used by Pol et al. (2016) corresponds to Fig. 4b, c and that of Visentin et al. (2016) to Fig. 4d. This may explain why Visentin et al. obtained consistent concentration data irrespective of the ligand level. The ligand was always captured and may have been confined to the top of the matrix. During analyte binding, the specific response can, therefore, be expected to be constant, as there is little variation in the SPR field strength.

The results obtained by Pol et al. (2016) and Visentin et al. (2016) demonstrate that the distribution of the analyte in the evanescent field has to be considered, if absolute concentration data are to be obtained.

It has been suggested that the effective diffusion coefficient can vary by at least one order of magnitude (Schuck 1996; Schuck and Zhao 2010) between solution and dextran matrix compartments. This would slow down reactions at higher immobilization levels, and would lead to lower concentration values. Diffusion effects may, therefore, contribute to the trends observed by Pol et al. (2016). However, the diffusion coefficients used in the CFCA analysis were solution based, and the active concentrations obtained at high degrees of immobilization gave results approximately 15 % lower than the total analyte concentrations. A ten-fold change in the diffusion coefficient would lead to a 4.6 times change in the transport coefficient. Such a change would impact concentration values much more than the 30–50 % that was observed when the immobilization levels were varied. Nevertheless, the differences observed in CFCA data may still be influenced by changes in diffusion that may have to be considered along with analyte distribution in the evanescent field.

The importance of analyte distribution and the impact of the evanescent field strength have been discussed already by Christensen (1997), who suggested the use of 2D surfaces for CFCA analysis.

At that time, there was too scarce experimental data to support the recommendation. Given the results by Pol et al. (2016) and Visentin et al. (2016), two approaches now appear possible for improving CFCA; the use of 2D surfaces or the use of capture on highly immobilized dextran surfaces.

Pol et al. (2016) introduced a form factor that can be used to calibrate CFCA data. The form factor is included in the CFCA algorithm found in Biacore T200 Evaluation Software version 3.0. The form factor can be edited by the user. It is suggested for tuning the transport coefficient based on results obtained with one or several analytes where the active concentration is known. A first attempt in this direction has been made by setting the form factor to 0.81 for the scenario in Fig. 4c (Pol et al. 2016). With a calibration kit, based on an analyte with known active concentration, molecular weight, and diffusion coefficient, it would be possible to handle data from both 2D surfaces and capture approaches. Additionally, it would be possible to ensure consistency of data from one instrument to another.

Instead of ligand-specific concentration analysis, the scenarios in Fig. 4a, e (if no ligand is attached to a negatively charged surface) can potentially be used to estimate the total protein concentration. This avenue of research is still largely unexplored. The rate of protein binding to highly charged surfaces is certainly transport limited, but the binding rate may also potentially be influenced by pH and by the use of different charge densities on sensor surfaces. Still, this points to a possibility to determine both total and binding-specific concentrations of a purified protein.

Relative data

While CFCA can already be used to estimate an absolute concentration, a 15–30 % error can sometimes be expected. This error may drop considerably if a calibration kit becomes available.

However, in many instances, a relative concentration or the concentration ratio between two samples is of key interest. This is the case in potency testing, where a new sample is always compared to a reference product. By taking the ratio of two CFCA results determined under similar conditions, uncertainties in CFCA will cancel out. The result will be independent of how the signal is interpreted and errors in the values of the diffusion coefficient and the molecular weight will no longer impact the results.

Data obtained with non one-to-one interactions

The analytical situation is often more complex than suggested by a one-to-one interaction. Antibody binding to antigen may lead to avidity effects and can then not be considered as single binding events.

Simulation of avidity effects (Table 3) indicate that avidity will not impact concentration data when low concentrations (1–4 nM) are used. This means that it will be possible to determine antibody concentrations when antibodies bind to immobilized antigen.

Table 3.

Predictions of the impact of avidity on CFCA data

| Parameter values used in simulations | Concentrations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ka1 (M−1s−1) | ka2 (RU−1s−1) | kd1 (s−1) | kd2 (s−1) | Rmax (RU) | Flow rates (μL/min) | kt at 1 μL/min (RU*M−1s−1) | Conc. (nM) | Expected (nM) | Found (nM) |

| 7.59*103 | 5.06*10−4 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 7.59*103 | 5.06*10−3 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 7.59*103 | 5.06*10−5 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 8.65*104 | 5.77*10-3 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 8.65*104 | 5.77*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 8.65*104 | 5.77*10−4 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 1.48*106 | 9.87*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| 1.48*106 | 9.87*10−1 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 1.48*106 | 9.87*10−3 | 1*10−2 | 1*10−2 | 2000 | 5 and 100 | 4.88*108 | 1, 2, and 4 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

Avidity was simulated with the bivalent analyte model and re-evaluation of data with the CFCA model (see the Supplementary data for rate equations) using BIAevaluation software v4.1.1. The second association rate constant reflects a binding event that occurs on the immobilized ligand. For each first association rate constant, three second association rate constants were tested to probe cooperative binding events. Low concentrations were used to ensure low ligand occupancy

Heterogeneous binding may occur for a number of reasons. An immune response may be polyclonal and several antibodies may react in parallel or compete for antigen binding.

Alternatively, an analyte can be present in multiple forms due to post-translational modifications or aggregation. In some cases, the analyte may bind non-specifically to the sensor surface.

To illustrate one case, specific and non-specific binding were simulated. For each situation, the one-to-one interaction model in BIAevaluation software v4.1.1 was used for the simulation. This resulted in sensorgrams for the specific binding and sensorgrams for the non-specific binding. The response values for each binding event were added to obtain sensorgrams that contained both elements and, finally, these sensorgrams were re-analyzed with the CFCA model. In simulations, binding was assumed to proceed with a ten-fold higher association rate constant for the specific binding and with a ten-fold lower or equal binding capacity for the non-specific element. Evaluated data in the first case were 4 % higher than expected and in the second case, it was 37 % higher.

Clearly, heterogeneity can impact CFCA results. This suggests that the design of the assay will be important. Clean-up of ligand or sample as well as design of a reference surface may allow the investigator to focus the data on the analyte of interest. The use of diluted sample may also be beneficial, as this may favor the binding of interest.

Conclusions

The importance of protein concentration is undisputed, but the determination of protein concentration is typically not considered a hot topic. CFCA, as discussed in this paper, however, has some remarkable features. It measures active concentrations, and accurate concentration data may be determined directly without the use of a standard preparation. Current CFCA methodology allows a user to easily set up an experiment. With cycle times of 1–2 minutes, the assay is rapid and results are obtained in a short time. The repeatability of CFCA analysis is excellent (Pol et al. 2016). The ratio of CFCA concentrations determined under similar conditions is useful for potency analysis, where a new sample is compared to a reference preparation. As discrete CFCA results are available for both sample and reference, CFCA not only allows calculation of the ratio between samples, but it can also be used to control that the reference sample does not change over time.

CFCA at this point does not seem to have gained widespread use or even general acceptance. In fact, many of the papers cited in this article originate from a few research groups. One reason for this may be linked to the difficulty in validating CFCA results. Theoretical analysis suggests that CFCA has the potential to provide accurate results, even at low degrees of MTL. Experimental data obtained with directly immobilized ligands contradict this assumption, as CFCA results depend on the immobilization level, in spite of acceptable degrees of MTL. Uneven distribution of analyte in the dextran matrix coupled with the fact that the signal strength decays with distance from the sensor surface may explain the discrepancy between simulated data and experimental results.

Two approaches are suggested to improve on the accuracy of CFCA: to use 2D surfaces or capture on highly immobilized 3D (dextran) surfaces. When these approaches are combined with a calibration kit or clear instructions on how to calibrate CFCA parameters, CFCA methodology may come into maturation.

Improved methodology does not mean that all challenges have been mastered. Different proteins may have different refractive index increments (Zhao et al. 2011). Fortunately, this can be calculated and, therefore, used in CFCA algorithms as part of the form factor. CFCA additionally relies on the fact that the diffusion coefficient of the analyte can be determined, and errors in the diffusion coefficient will propagate into the CFCA results.

CFCA is already at a stage where relative concentrations determined by it can be used in potency and similarity studies. In parallel with the development of CFCA as an absolute concentration method, it is expected to be continuously used for the analysis of more complex interactions. While avidity is predicted not to influence data, heterogeneity may and this will require attention during the design of the assay. Here, values determined by CFCA should not be considered as absolute concentration values, but they can be used to estimate protein concentrations and changes in concentration over time. Empirical use of CFCA in vaccine studies and for biomarker analysis has already provided meaningful input to aid vaccine design and for the grouping of patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgments

I met with professor Winzor several times during the early Biacore days when I visited Australia. He straightened me out on some mathematical issues and helped me to derive correct rate equations for the bivalent analyte model included in the Supplementary data. I have always struggled with the mathematics and remember Don as being crisp and clear on these topics. It was a great help for me.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author is employed by GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, the provider of Biacore™ systems.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of a Special Issue on “Analytical Quantitative Relations in Biochemistry” edited by Damien Hall and Stephen Harding.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12551-016-0219-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Abdiche YN, Yeung YA, Chaparro-Riggers J, Barman I, Strop P, Chin SM, Pham A, Bolton G, McDonough D, Lindquist K, Pons J, Rajpal K. The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) binds independently to both sites of the IgG homodimer with identical affinity. MAbs. 2015;7(2):331–343. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1008353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allignet J, England P, Old I, El Solh N. Several regions of the repeat domain of the Staphylococcus caprae autolysin, AtlC, are involved in fibronectin binding. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;213(2):193–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. Blame it on the antibodies. Nature. 2015;521(7552):274–276. doi: 10.1038/521274a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee C, Abdiche YN, Stone DM, Collier S, Lindquist KC, Pinkerton AC, Pons J, Rajpal A. Exploring the dynamic range of the kinetic exclusion assay in characterizing antigen–antibody interactions. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee C, Abdiche YN, Pons J, Rajpal A. Determining the binding affinity of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies towards their native unpurified antigens in human serum. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr S, Heermann R, Jung K. Insights into the DNA-binding mechanism of a LytTR-type transcription regulator. Biosci Rep. 2016;36(2):e00326. doi: 10.1042/BSR20160069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes A, Spiegel H, Edgue G, Kapelski S, Scheuermayer M, Fendel R, Remarque E, Altmann F, Maresch D, Reimann A, Pradel G, Schillberg S, Fischer R. Detailed functional characterization of glycosylated and nonglycosylated variants of malaria vaccine candidate PfAMA1 produced in Nicotiana benthamiana and analysis of growth inhibitory responses in rabbits. Plant Biotechnol J. 2015;13(2):222–234. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes A, Spiegel H, Voepel N, Edgue G, Beiss V, Kapelski S, Fendel R, Scheuermayer M, Pradel G, Bolscher JM, Behet MC, Dechering KJ, Hermsen CC, Sauerwein RW, Schillberg S, Reimann A, Fischer R. Analysis of a multi-component multi-stage malaria vaccine candidate—tackling the cocktail challenge. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0131456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes A, Spiegel H, Kastilan R, Bethke S, Voepel N, Chudobová I, Bolscher JM, Dechering KJ, Fendel R, Buyel JF, Reimann A, Schillberg S, Fischer R. Analysis of the dose-dependent stage-specific in vitro efficacy of a multi-stage malaria vaccine candidate cocktail. Malar J. 2016;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choulier L, Shvadchak VV, Naidoo A, Klymchenko AS, Mély Y, Altschuh D. A peptide-based fluorescent ratiometric sensor for quantitative detection of proteins. Anal Biochem. 2010;401(2):188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LL. Theoretical analysis of protein concentration determination using biosensor technology under conditions of partial mass transport limitation. Anal Biochem. 1997;249(2):153–164. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mol NJ, Fischer MJE. Chapter 5. Kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of ligand–receptor interactions: SPR applications in drug development. In: Schasfoort RBM, Tudos AJ, editors. Handbook of surface plasmon resonance. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2008. pp. 123–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fant M, Wang L, Karlsson R, Larsson A, Franklin G, Pol E (2007) Calibration-free concentration analysis in the development of therapeutic proteins. Poster 29-0011-94 AA from GE Healthcare

- Hensel M, Steurer R, Fichtl J, Elger C, Wedekind F, Petzold A, Schlothauer T, Molhoj M, Reusch D, Bulau P. Identification of potential sites for tryptophan oxidation in recombinant antibodies using tert-butylhydroperoxide and quantitative LC-MS. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson U, Fägerstam L, Ivarsson B, Johnsson B, Karlsson R, Lundh K, Löfås S, Persson B, Roos H, Rönnberg I, Sjölander S, Stenberg E, Ståhlberg R, Urbaniczky C, Östlin H, Malmqvist M. Real-time biospecific interaction analysis using surface plasmon resonance and a sensor chip technology. Biotechniques. 1991;11(5):620–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson R, Fägerstam L, Nilshans H, Persson B. Analysis of active antibody concentration. Separation of affinity and concentration parameters. J Immunol Methods. 1993;166(1):75–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90330-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärnhall J (2011) New SPR based assays for plasma protein titer determination. Master’s thesis, University of Linköping. urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-70044

- Kubetzko S, Sarkar CA, Plückthun A. Protein PEGylation decreases observed target association rates via a dual blocking mechanism. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68(5):1439–1454. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myszka DG, He X, Dembo M, Morton TA, Goldstein B. Extending the range of rate constants available from BIACORE: interpreting mass transport-influenced binding data. Biophys J. 1998;75(2):583–594. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77549-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pille J, Cardinale D, Carette N, Di Primo C, Besong-Ndika J, Walter J, Lecoq H, van Eldijk MB, Smits FCM, Schoffelen S, van Hest JCM, Mäkinen K, Michon T. General strategy for ordered noncovalent protein assembly on well-defined nanoscaffolds. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14(12):4351–4359. doi: 10.1021/bm401291u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pissani F (2012) HIV vaccine design based on in vivo evolution of quasispecies envelope proteins. Scholar Archive. Paper 887, Oregon Health & Science University

- Plummer JB (2012) Evidence of human endogenous retrovirus K involvement in human cancer. UT GSBS Dissertations and Theses (Open Access). Paper 255

- Pol E. The importance of correct protein concentration for kinetics and affinity determination in structure–function analysis. JoVE (J Vis Exp) 2010;37:e1746. doi: 10.3791/1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pol E, Karlsson R, Roos H, Jansson Å, Xu B, Larsson A, Jarhede T, Franklin G, Fuentes A, Persson S. Biosensor-based characterization of serum antibodies during development of an anti-IgE immunotherapeutic against allergy and asthma. J Mol Recognit. 2007;20(1):22–31. doi: 10.1002/jmr.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pol E, Roos H, Markey F, Elwinger F, Shaw A, Karlsson R. Evaluation of calibration-free concentration analysis provided by Biacore™ systems. Anal Biochem. 2016;510:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Kumar V, Bhave A, Singh V, Gogtay NJ, Thatte UM, Talukdar A, Kochar SK, Patankar S, Srivastava S. Proteomic analysis of Plasmodium falciparum induced alterations in humans from different endemic regions of India to decipher malaria pathogenesis and identify surrogate markers of severity. J Proteome. 2015;127:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richalet-Sécordel PM, Rauffer-Bruyère N, Christensen LL, Ofenloch-Haehnle B, Seidel C, Van Regenmortel MH. Concentration measurement of unpurified proteins using biosensor technology under conditions of partial mass transport limitation. Anal Biochem. 1997;249(2):165–173. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck P. Kinetics of ligand binding to receptor immobilized in a polymer matrix, as detected with an evanescent wave biosensor. I. A computer simulation of the influence of mass transport. Biophys J. 1996;70(3):1230. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79681-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck P, Zhao H (2010) The role of mass transport limitation and surface heterogeneity in the biophysical characterization of macromolecular binding processes by SPR biosensing. In: de Mol NJ, Fischer MJE (eds) Surface plasmon resonance. Methods and protocols. Humana Press, pp 15–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shah VG, Ray S, Karlsson R, Srivastava S. Calibration-free concentration analysis of protein biomarkers in human serum using surface plasmon resonance. Talanta. 2015;144:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmundsson K, Másson G, Rice R, Beauchemin N, Öbrink B. Determination of active concentrations and association and dissociation rate constants of interacting biomolecules: an analytical solution to the theory for kinetic and mass transport limitations in biosensor technology and its experimental verification. Biochemistry. 2002;41(26):8263–8276. doi: 10.1021/bi020099h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sissoeff L, Mousli M, England P, Tuffereau C. Stable trimerization of recombinant rabies virus glycoprotein ectodomain is required for interaction with the p75NTR receptor. J Gen Virol. 2005;86(9):2543–2552. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoelander S, Urbaniczky C. Integrated fluid handling system for biomolecular interaction analysis. Anal Chem. 1991;63(20):2338–2345. doi: 10.1021/ac00020a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel H, Boes A, Kastilan R, Kapelski S, Edgue G, Beiss V, Chubodova I, Scheuermayer M, Pradel G, Schillberg S, Reimann A, Fischer R. The stage-specific in vitro efficacy of a malaria antigen cocktail provides valuable insights into the development of effective multi-stage vaccines. Biotechnol J. 2015;10(10):1651–1659. doi: 10.1002/biot.201500055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg E, Persson B, Roos H, Urbaniczky C. Quantitative determination of surface concentration of protein with surface plasmon resonance using radiolabeled proteins. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1991;143(2):513–526. doi: 10.1016/0021-9797(91)90284-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Have R, Westdijk J, Levels LMAR, Koedam P, de Haan A, Hamzink MRJ, Metz B, Kersten GFA. Trypsin diminishes the rat potency of polio serotype 3. Biologicals. 2015;43(6):474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin J, Minder L, Lee JH, Taupin JL, Di Primo C. Calibration free concentration analysis by surface plasmon resonance in a capture mode. Talanta. 2016;148:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voepel N, Boes A, Edgue G, Beiss V, Kapelski S, Reimann A, Schillberg S, Pradel G, Fendel R, Scheuermayer M, Spiegel H, Fischer R. Malaria vaccine candidate antigen targeting the pre-erythrocytic stage of Plasmodium falciparum produced at high level in plants. Biotechnol J. 2014;9(11):1435–1445. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Matsumaru H, Ooishi A, Honda S. Structure-based histidine substitution for optimizing pH-sensitive Staphylococcus protein A. J Chromatogr B. 2013;929:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westdijk J, Brugmans D, Martin J, van’t Oever A, Bakker WA, Levels L, Kersten G. Characterization and standardization of Sabin based inactivated polio vaccine: proposal for a new antigen unit for inactivated polio vaccines. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3390–3397. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Douglas AD, Miura K, Illingworth JJ, Choudhary P, Murungi LM, Furze JM, Diouf A, Miotto O, Crosnier C, Wright GJ, Kwiatkowski DP, Fairhurst RM, Long CA, Draper SJ. Enhancing blockade of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion: assessing combinations of antibodies against PfRH5 and other merozoite antigens. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(11):e1002991. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeder-Lutz G, Benito A, Van Regenmortel MHV. Active concentration measurements of recombinant biomolecules using biosensor technology. J Mol Recognit. 1999;12(5):300–309. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1352(199909/10)12:5<300::AID-JMR467>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Brown PH, Schuck P. On the distribution of protein refractive index increments. Biophys J. 2011;100(9):2309–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 19 kb)