Abstract

Lynch syndrome, caused by germline mutations in the mismatch repair genes, is associated with increased cancer risk. Here using a large whole-genome sequencing data bank, cancer registry and colorectal tumour bank we determine the prevalence of Lynch syndrome, associated cancer risks and pathogenicity of several variants in the Icelandic population. We use colorectal cancer samples from 1,182 patients diagnosed between 2000–2009. One-hundred and thirty-two (11.2%) tumours are mismatch repair deficient per immunohistochemistry. Twenty-one (1.8%) have Lynch syndrome while 106 (9.0%) have somatic hypermethylation or mutations in the mismatch repair genes. The population prevalence of Lynch syndrome is 0.442%. We discover a translocation disrupting MLH1 and three mutations in MSH6 and PMS2 that increase endometrial, colorectal, brain and ovarian cancer risk. We find thirteen mismatch repair variants of uncertain significance that are not associated with cancer risk. We find that founder mutations in MSH6 and PMS2 prevail in Iceland unlike most other populations.

Lynch syndrome is characterized by predisposition to colorectal cancer and mutations in genes involved in mismatch repair. Here, the authors use whole genome sequencing and immunohistochemistry of mismatch repair proteins to show a high prevalence of Lynch syndrome in the Icelandic population.

Lynch syndrome (LS) is the most common inherited cause of colorectal cancer (CRC). The estimated population frequency is 1:370 to 1:2,000 in Western populations1,2. LS is also associated with increased lifetime risk of several other cancer types including endometrial and ovarian cancer3,4. LS prevalence has never been determined across an entire nation.

Microsatellite instability (MSI) and mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) are hallmarks of LS-related CRC. About 15% of CRC exhibit dMMR5 with 2–3% caused by germline mutations in the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 or EPCAM genes6 while 12% of CRC cases have somatic inactivation of MLH1 via promoter hypermethylation (MLH1-hm)7. Furthermore, double somatic mismatch repair (MMR) mutations may explain up to 67% of dMMR CRC cases without LS or MLH1-hm8.

Several groups in Europe and the United States have recommended universal screening of CRC9,10,11,12 using MSI testing or immunohistochemistry for the MMR proteins to identify potential LS cases. MLH1-hm can be assessed directly or inferred by the presence of a somatic BRAF V600E mutation13.

Due to the low frequency of individual LS mutations and heterogeneity in phenotypic expression, it has proven difficult to accurately establish population-based prevalences and to assess the cancer penetrance of LS gene mutations. Furthermore, numerous reported variants of uncertain clinical significance (VUS) complicate genetic counseling. Recently, a collaborative effort was undertaken to reclassify MMR variants in the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT) database (http://insight-group.org/variants/database/)14.

The Icelandic population offers several advantages for studying the genetic epidemiology and associated cancer risks of LS15. These include (i) a nationwide cancer registry dating back to 1955; (ii) universal tumour banking since 1935; (iii) documentation of the entire population's genealogy over centuries; and (iv) the isolation and relative homogeneity of the population which enhances the potential to discover founder mutations. To date, the DNA of over 150,000 Icelanders has undergone whole-genome analysis on microarray platforms. Additionally, 8,453 Icelanders have undergone whole-genome sequencing (WGS). Using long-range phasing, these sequence variants, down to a frequency of <0.01%, have been imputed into the genomes of those genotyped and into un-genotyped close relatives identified via genealogic databases (familial imputation). This familial imputation allows the inclusion of genotypes for cancer cases that were diagnosed decades ago, greatly enhancing the power of this study.

The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence of LS in the Icelandic population and to establish the different etiologies for dMMR in a population-based CRC cohort. Tumours from all CRC cases diagnosed from 2000–2009 were screened for dMMR using immunohistochemistry and methylation assays and patients were genotyped for MMR variants extracted from the deCODE database. Unexplained dMMR cases underwent germline WGS and if still unexplained, tumour ColoSeq. Furthermore, variants extracted from the deCODE database were merged with the cancer registry to estimate the cancer penetrance of LS gene mutations and cancer association of VUS's found in the Icelandic population. We find that MSH6 and PMS2 mutations prevail in the population with a LS prevalence of 1 in 226, the highest reported so far.

Results

LS founder mutations in the Icelandic population

Association studies, using WGS data in the Icelandic population and information on all cancer types, revealed three LS mutations that showed significant association with CRC and endometrial cancer (Table 1). All three mutations are present at allelic frequencies >0.05%, presumably reflecting a founder effect in the population. One mutation in MSH6 (p.Leu585Pro, class 3 per InSiGHT) and another in PMS2 (p.Pro246Cysfs*3, class 5 per InSiGHT) were found in 9 and 12 patients with dMMR CRC, respectively (see below). A further mutation in PMS2 (p.Met1?; pathogenic mutation in National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) ClinVar16) was identified in the population but not in any CRC patients diagnosed during 2000–2009. These mutations were imputed and the prevalence of LS in the Icelandic population determined to be 0.442% or one in 226 individuals. The imputation quality was tested by direct genotyping of the three variants. The concordance between imputed and directly measured genotypes was 1.00 for PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 and PMS2 p.Met1? and 0.99 for MSH6 p.Leu585Pro (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Lynch syndrome mutations in the Icelandic population.

| Gene | Hg38 location | Coding change | Protein change | Pathogenicity* | Nr. pts in CRC cohort | Carrier frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMS2 | chr7:5997387 | c.736_741del6ins11 | p.Pro246Cysfs*3 | Class 5 | 12 | 0.234%† |

| PMS2 | chr7:6009018 | c.2T>A | p.Met1? | Pathogenic‡ | 0 | 0.092%† |

| MSH6 | chr2:47799737 | c.1754T>C | p.Leu585Pro | Class 3 | 9 | 0.080%† |

| MLH1 | chr3:36998760 | Balanced translocation (Fig. 1) | NK | 1 | 1 Family§ | |

| MSH6 | chr2:47798826 | c.843_844insAC | p.Val282Thrfs*10 | NK | 1 | 1 Family§ |

| MSH6 | chr2:47803500 | c.3261dupC | p.Phe1088Leufs*5 | Class 5 | 1 | 1 Family§ |

| MSH6 | chr2:47804984 | c.3514dupA | p.Arg1172Lysfs*5 | Class 5 | 1 | 1 Family§ |

| MSH2 | chr2:47478506 | c.2445T>A | p.Tyr815* | NK | 0 | 1 Family† |

| PMS2 | chr7:6004007 | c.211_214del | p.Asn71Aspfs*4 | NK | 1 | 1 Patient§ |

| PMS2 | chr7:5982885 | c.2113G>A | p.Glu705Lys | Class 3 | 1 | 1 Patient§ |

CRC, colorectal cancer; MMR, mismatch repair; NK, not known; Nr., number; pts=patients.

*Pathogenicity as listed in InSiGHT, if known.

†Extracted from deCODE's database.

‡Listed as pathogenic in NCBI ClinVar16, not listed in InSiGHT.

§Found by sequencing patients with dMMR CRC.

Patient characteristics

A total of 1,208 patients were diagnosed with colorectal carcinoma in Iceland from 2000–2009, with 1,182 (97.8%) included in this study. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. All patients with abnormal immunohistochemistry and 78.2% of patients with normal immunohistochemistry had germline DNA available for genotyping (80.6% of the cohort).

Table 2. Patient and tumour characteristics in the colorectal cancer cohort.

| Proficient MMR (n=1,044) | Lynch syndrome (n=27)* | MLH1-hm (n=90) | Double somatic MMR (n=16) | dMMR unexplained (n=5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (Q1, Q3) | 71 (61, 78) | 62 (55, 72) | 78 (73, 84) | 69 (57, 79) | 75 (35, 86) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 601 (57.6%) | 22 (81.5%) | 25 (27.8%) | 9 (56.3%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Female | 443 (42.4%) | 5 (18.5%) | 65 (72.2%) | 7 (43.7%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||||

| I | 193 (18.5%) | 5 (18.5%) | 9 (10.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| II | 282 (27.0%) | 16 (59.3%) | 47 (52.2%) | 9 (56.3%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| III | 298 (28.5%) | 4 (14.8%) | 24 (26.7%) | 4 (25.0%) | 0 |

| IV | 230 (22.0%) | 2 (7.4%) | 6 (6.7%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 |

| Unknown | 41 (3.9%) | 0 | 4 (4.4%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 |

| Location | |||||

| Right | 357 (34.7%) | 14 (51.9%) | 76 (86.4%) | 13 (81.3%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Left | 366 (35.5%) | 9 (33.3%) | 8 (9.1%) | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Rectum† | 307 (29.8%) | 4 (14.8%) | 4 (4.5%) | 1 (6.2%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Metachronous | 30 (2.9%) | 1 (3.7%) | 6 (6.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Synchronous | 30 (2.9%) | 2 (7.4%) | 4 (4.4%) | 0 | 0 |

dMMR, deficient mismatch repair activity; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MLH1-hm, MLH1 hypermethylation; MMR, mismatch repair; N, number; Q, quartiles.

*Six LS patients with CRC with normal IHC are included here.

†Rectosigmoid location is included with rectum.

LS and dMMR in the CRC cohort

MMR immunohistochemistry was abnormal in 132 patients (11.2%; Table 3). MLH1-hm was found in 90 cases (7.6% of the cohort). Twenty-one patients with abnormal immunohistochemistry and six patients with normal immunohistochemistry had LS mutations (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Eight different LS mutations were identified, including the MSH6 p.Leu585Pro and PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 mutations described above, four private mutations (found in a single family each) and two mutations in PMS2, not found in other family members or the population (de novo or very recent). The prevalence of LS in the CRC cohort was therefore 2.3% (27/1182). The median age at CRC diagnosis of patients with the MSH6 p.Leu585Pro mutation was 60 (Q1 51, Q3 73; range 41–75) and the median age of patients with the PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 mutation was 60.5 (Q1 50.5, Q3 70; range 31–86). One patient with PMS2 tumour loss had a class 3 PMS2 variant (p.Glu705Lys). Tumour ColoSeq identified the same variant as well as likely loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the tumour (Table 4). We, therefore, believe this variant is pathogenic and classified this case as having LS. Tumour ColoSeq was performed on 5 of 6 tumour samples from patients with LS who had normal MMR IHC (Table 4). Second hits were found in 3 cases with a MSH6 p.Leu585Pro mutation but not 2 cases with a PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 mutation. Twenty-one patients with dMMR tumours had neither a LS mutation or MLH1-hm. Sixteen patients were found to have double somatic MMR mutations by ColoSeq tumour testing (1.4% of the cohort; Table 4). Five dMMR cases remained unexplained, three cases had one somatic MSH2 mutation and tested negative for MSH2 methylation suggesting an unidentifiable MSH2 mutation in germline or tumour DNA. Two cases failed tumour testing due to low tumour DNA content. None of these patients had a convincing family history of cancer. By using the 953 individuals (80.6% of the cohort) that had germline genotyping as a denominator, the sensitivity and specificity of IHC in detecting LS was 77.8% and 97.7%, respectively. The positive and negative predictive value of abnormal IHC predicting LS was 50.0% and 99.3%, respectively.

Table 3. Colorectal cancer cases with abnormal mismatch repair protein immunohistochemistry.

| Absent stains on IHC |

Etiology of mismatch repair deficiency |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLH1-hm | LS | Double somatic MMR | Unexplained | Nr. cases | |

| MLH1/PMS2 | 90* | 1 | 8 | 1 | 100 (8.5%) |

| MSH2/MSH6 | NA | 2† | 5 | 4 | 11 (0.9%) |

| MSH6 | NA | 7 | 1 | 0 | 8 (0.7%) |

| PMS2 | NA | 11‡ | 2 | 0 | 13 (1.1%) |

| Total | 90 (7.6%)§ | 21 (1.8%) | 16 (1.4%) | 5 (0.4%) | 132 (11.2%) |

IHC, immunohistochemistry; LS, Lynch syndrome; MLH1-hm, MLH1 hypermethylation; NA, not applicable; Nr., number.

The denominator in the table is all CRC patients (n=1182). The six patients with LS and normal IHC are not depicted in this table.

*One case had MLH1/PMS2/MSH2 missing.

†One case had MSH2/MSH6/PMS2 missing.

‡One case had MSH6/PMS2 missing.

§Three biopsy cases failed MLH1-hm testing but were positive for BRAF V600E via IHC.

Table 4. Somatic mismatch repair gene mutations as tested by ColoSeq.

| Study ID | mSINGS | MSI | MLH1-hm | Absent stains on IHC | Gene | MMR mutation no.1 | MMR mutation no. 2 | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 197 | 0.4062 | MSI-H | 10% | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | c.493del (p.A165Lfs*2) | LOH | Double somatic |

| 237 | 0.4531 | MSI-H | 4% | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | c.2237del (p.L746Rfs*37) | LOH | Double somatic |

| 466 | 0.5538 | MSI-H | 5% | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | c.1684C>T (p.Q562*) | LOH | Double somatic |

| 506 | 0.5079 | MSI-H | 4% | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | c.199G>A (p.G67R) | LOH | Double somatic |

| 745 | 0.4923 | MSI-H | 10% | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | c.1783_1784del (p.S595Wfs*14) | LOH | Double somatic |

| 985 | 0.4462 | MSI-H | 10% | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | c.588del (p.K196Nfs*6) | c.171del; c.299G>A (p.K57Nfs*2; p.R100Q) | Double somatic |

| 1034 | 0.5538 | MSI-H | 6% | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | c.2142G>A (p.W714*) | c.670_673dup (p.R226*) | Double somatic |

| 1141 | 0.4923 | MSI-H | NT | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | c.2206G>T (p.E736*) | LOH | Double somatic |

| 246 | 0.4769 | MSI-H | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.545_552del (p.D182Vfs*4) | c.1661+1G>A (Splicing) | Double somatic |

| 1082 | 0.3492 | MSI-H | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.82del (p.E28Rfs*36) | c.1310del (p.V437Gfs*17) | Double somatic |

| 1049 | 0.4754 | MSI-H | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.942+3A>T (splicing) | LOH | Double somatic |

| 959 | 0.5846 | MSI-H | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.2459-2A>C (splicing) | c.2352del (p.H785Mfs*27) | Double somatic |

| 951 | 0.5156 | MSI-H | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.425C>G (p.S142*) | c.942+3A>T (splicing) | Double somatic |

| 509 | 0.1587 | MSS | NT | MSH6 | MSH2 | Inversion; c.2210+7G>T (germline)* | LOH (maybe) | Possibly double somatic |

| 1231 | 0.4462 | MSI-H | NT | PMS2 | PMS2 | c.325delG (p.E109Kfs*3) | c.444delC; c.903+1G>A (p.Y149Tfs*52; splicing) | Double somatic |

| 1022 | 0.2857 | MSI-H | NT | PMS2 | PMS2 | Exon 11 homozygous deletion | LOH | Double somatic |

| 427 | 0.4462 | MSI-H | NT | PMS2 | PMS2 | c.2113G>A (p.E705K, germline) | LOH (likely) | Lynch syndrome† |

| 1057 | 0.5692 | MSI-H | NT | PMS2 | PMS2 | c.211_214del (p.N71Dfs*4, germline) | c.2113G>A (p.E705K), LOH (maybe) | Lynch syndrome† |

| 339 | 0.5626 | MSI-H | 5% | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 | Germline translocation‡ | c.2041G>A (p.Ala681Thr) | Lynch syndrome† |

| 786 | 0.2787 | MSI-H | NT | Normal (MSH6 weak, 1–5%) | MSH6 | c.1754T>C (p.L585P, germline) | c.3509delT (p.I1170Mfs*14) | Lynch syndrome† |

| 30 | 0.1228 | MSS | NT | Normal (MSH6 weak, 5%) | MSH6 | c.1754T>C (p.L585P, germline) | c.3261del (p.F1088Serfs*2) | Lynch syndrome† |

| 94 | 0.4032 | MSI-H | NT | Normal (MSH6 weak, 20–30%) | MSH6 | c.1754T>C (p.L585P, germline) | c.3016T>G (p.Y1006D) | Lynch syndrome† |

| 1250 | 0.1538 | MSS | NT | Normal | PMS2 | c.736_741del6ins11 (p.Pro246Cysfs*3, germline) | None detected | Lynch syndrome (sporadic tumour)† |

| 873 | 0.0615 | MSS | NT | Normal | PMS2 | c.736_741del6ins11 (p.Pro246Cysfs*3, germline) | None detected | Lynch syndrome (sporadic tumour)† |

| 162 | 0.5385 | MSI-H | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.2458+2delT (splicing) | None detected§ | Not solved |

| 1127 | 0.2188 | MSI-H | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.943-1G>C (splicing) | None detected§ | Not solved |

| 1108 | 0.4154 | MSI-H | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.2131C>T (p.R711*) | c.2635-10T>G (germline, splicing)‖,§ | Not solved |

| 418 | 0.1077 | MSS | NT | MSH2/MSH6 | MSH2 | c.1077-2736T>G (deep intronic) | LOH | Not solved¶ |

| 827 | 0.0923 | MSS | 2% | MLH1/PMS2 | None | Failed testing | Not solved¶ | |

| 240 | 0.2742 | MSI-H | 14% | MLH1/PMS2 | None | No hits to MMR genes—BRAF V600E | MLH1-hm |

LOH, loss of heterozygosity; MLH1-hm, MLH1 hypermethylation; MMR, mismatch repair; MSI-H, microsatellite unstable high; mSINGS, microsatellite instability by next-generation sequencing; MSS, microsatellite stable, NT ,not tested.

*c.2210+7G>T (rs374675118)—minor allelic frequency is 0.969% in the Icelandic population without CRC association (see Table 6: VUS).

†Two cases with de novo germline PMS2 mutations (427, 1057) and the MLH1 germline translocation (339) and five cases with normal MMR IHC underwent tumour Coloseq testing to confirm a second hit.

‡See Fig. 1.

§Negative for MSH2 hypermethylation.

‖Not clearly pathogenic.

¶Indeterminate study due to low tumour content.

Origin of LS mutations

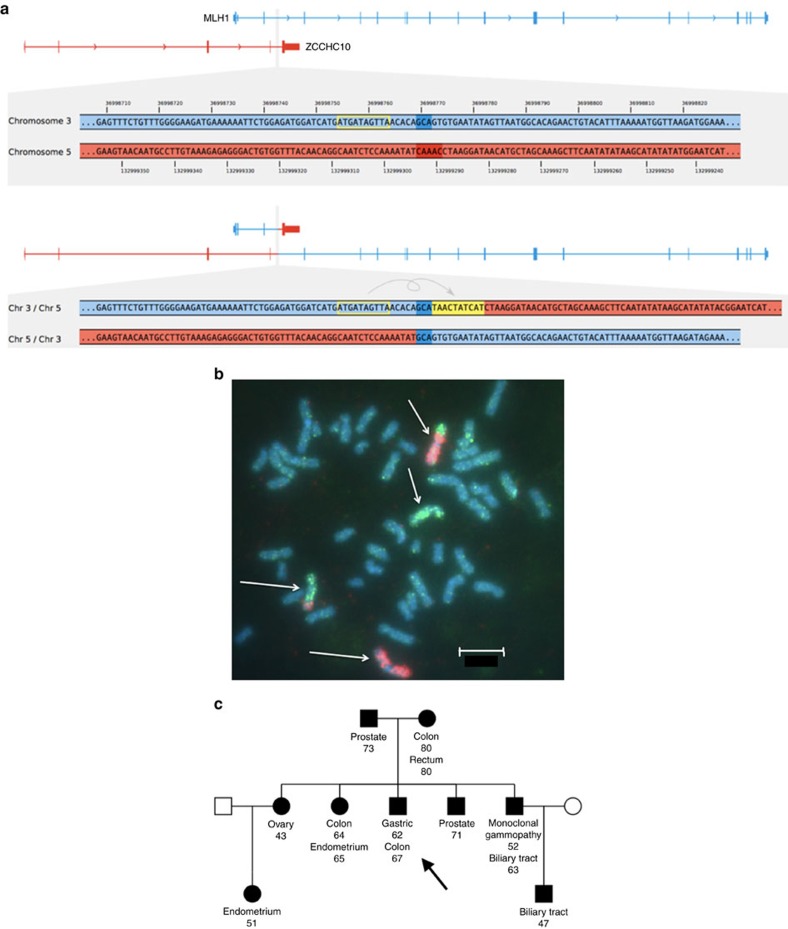

The PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 mutation carriers in Iceland, share a short haplotype with individuals from Sweden, Britain and the US (Supplementary Table 3), indicating that this mutation arose from a common ancestor, previously dated back 1,625 years17. Three private LS mutations in the CRC cohort and one private mutation outside of the CRC cohort were identified (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The MSH6 mutations (p.Val282Thrfs*10, p.Phe1088Leufs*5, p.Arg1172Lysfs*5) and the MSH2 mutation (p.Tyr815*) were traced back to ancestors in the 1700–1800s by genotyping individuals who shared haplotypes around the mutation. Interestingly, a novel balanced translocation, T(3p22;5q31), with breakpoints in MLH1 intron 3 and ZCCHC10, was identified by WGS and confirmed by karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in a family with high incidence of cancer (Fig. 1). This translocation was found in a parent and was inherited by several offspring with nearly 100% cancer penetrance (colorectal, endometrial, gastric, ovarian and renal cell carcinoma; three offspring developed two cancers) but not found in the 8,453 Icelanders who have undergone WGS.

Figure 1. Novel MLH1 translocation.

(a) The top half of the figure displays enlarged GRCh38 reference sequences from within MLH1 on chromosome 3 (blue) and from the reverse complement of chromosome 5 within ZCCHC10 (red) in a patient with CRC with MLH1/PMS2 absent on IHC. The bottom shows the translocation breakpoints observed in the sequencing data. The translocation connects an intron of MLH1 with an intron of ZCCHC10 in sense of the genes' orientations. At the breakpoint, a 3-bp duplication is present on both translocation haplotypes (dark blue), a 5-bp deletion is missing from both translocation haplotypes (dark red), and a 10-bp motif from nearby got inserted in reverse complemented orientation into one of the translocation haplotypes (yellow). (b) FISH, chromosome 3 (red CY3), chromosome 5 (green fitc). Chromosomes 3 and 5 are marked with white arrows. The scale shown is 5 μm. (c) Family tree with cancers and age at diagnosis. Proband is indicated with an arrow.

LS and associated cancer risks

The three imputed mutations (MSH6 p.Leu585Pro, PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 and PMS2 p.Met1?) vary in risk for different LS-associated cancer types as shown in Table 5. The MSH6 p.Leu585Pro mutation is associated with a nearly 50% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer and a 36% and 25% risk of CRC in males and females as well as a ∼12% lifetime risk of brain cancer (glioma). The two PMS2 mutations are associated with a significantly increased risk of endometrial, colorectal and ovarian cancer, although the overall cancer risks are lower than for the MSH6 mutation. Risks for other cancers were not significantly increased and are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 5. Icelandic Lynch syndrome mutations and odds ratios for different cancers.

| Cancer type | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P-value | Cases | Controls | Info | Cancer risk (M) | Cancer risk (F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSH6 p.Leu585Pro Pop carrier freq: 0.080% | Endometrial cancer | 32.8 | 13.5–80.0 | 1.61 × 10−14 | 923 | 115,104 | 0.92 | NA | 49.2% |

| Colorectal cancer | 10.1 | 5.1–20.1 | 4.19 × 10−11 | 3834 | 262,425 | — | 36.4% | 25.3% | |

| Colon cancer | 7.5 | 3.3–17.0 | 1.89 × 10−6 | 2793 | 263,466 | — | 17.9% | 12.7% | |

| Rectal cancer | 12.4 | 4.4–34.8 | 1.79 × 10−6 | 1082 | 260,587 | — | 16.1% | 9.9% | |

| Brain cancer (glioma) | 8.9 | 2.2–36.2 | 2.19 × 10−3 | 702 | 358,789 | — | 13.4% | 10.7% | |

| PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 Pop carrier freq: 0.234% | Endometrial cancer | 9.9 | 4.9–19.8 | 1.30 × 10−10 | 923 | 115,104 | 0.99 | NA | 14.8% |

| Colorectal cancer | 3.6 | 2.2–5.9 | 7.64 × 10−7 | 3834 | 262,425 | — | 12.9% | 9.0% | |

| Colon cancer | 3.8 | 2.2–6.6 | 1.7 × 10−7 | 2793 | 263,466 | — | 9.2% | 6.5% | |

| Rectal cancer | 2.3 | 0.8–6.9 | 1.2 × 10−1 | 1082 | 260,587 | — | 3.0% | 1.9% | |

| Ovarian cancer | 3.9 | 1.3–11.9 | 1.53 × 10−2 | 779 | 121,299 | — | NA | 3.5% | |

| PMS2 p.Met1? Pop carrier freq: 0.092% | Endometrial cancer | 7.5 | 2.4–23.5 | 5.53 × 10−4 | 923 | 115,104 | 0.99 | NA | 11.3% |

| Colorectal cancer | 2.2 | 0.94–5.3 | 7.01 × 10−2 | 3834 | 262,425 | — | 8.0% | 5.5% | |

| Colon cancer | 2.7 | 1.1–6.8 | 3.7 × 10−2 | 2793 | 263,466 | — | 6.4% | 4.6% | |

| Rectal cancer | 0.9 | 0.13–6.7 | 5.4 × 10−1 | 1082 | 260,587 | — | 1.2% | 0.8% | |

| Ovarian cancer | 6.6 | 1.8–24.3 | 4.16 × 10−3 | 779 | 121,299 | — | NA | 6.0% |

F, females; Pop carrier freq, population-based carrier frequency; LS, Lynch syndrome; M, males; NA, not applicable.

Cancer risks are calculated by using lifetime cancer risk at age 75 obtained from the Icelandic Cancer Registry18.

In total 16 cancers were tested for each of the mutations. Significant P-value<3.13 × 10−3 to correct for multiple tests. Info represents the imputation quality of the variant. P-values were obtained by logistic regression analysis.

Variants of uncertain significance

We identified 13 MMR gene variants previously described as VUS's and ten novel variants, in the Icelandic population. These were imputed and odds ratios for CRC estimated. None of these variants were associated with cancer risk or unexplained dMMR suggesting they are benign variants. These variants are listed in Table 6.

Table 6. Mismatch repair gene variants of uncertain significance and associated colorectal cancer risk in the Icelandic population.

| Gene | Hg38 location | IHC stains in CRC pts with variant* | Protein change | InSiGHT classification | Carrier frequency (%) in controls | Odds ratio for CRC | 95% Confidence interval | P-value | Info |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLH1 | |||||||||

| chr3:36993584 | Normal (1) | p.Glu13Lys | Class 3 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.22–4.12 | 0.94 | 0.96 | |

| chr3:36993612 | MLH1-hm (1) | p.Gly22Ala | Class 3 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.33–1.88 | 0.58 | 0.99 | |

| chr3:37017517 | Normal (2) | p.Glu268Gln | NK | 0.08 | 1.60 | 0.51–5.07 | 0.42 | 0.95 | |

| chr3:37017536 | None | p.Lys274Arg | NK | 0.22 | 0.78 | 0.33–1.88 | 0.58 | 0.91 | |

| MSH2 | |||||||||

| chr2:47429940 | Normal (4) | p.Glu425.= | Class 3† | 0.26 | 0.62 | 0.26–1.45 | 0.27 | 0.99 | |

| chr2:47445555 | Normal (1) | p.His428Gln | NK | 0.07 | 1.85 | 0.65–5.25 | 0.25 | 1.00 | |

| chr2:47476525 | Normal (7), MLH1-hm (1) | p.Val722Ile | Class 3† | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.48–1.30 | 0.36 | 0.98 | |

| chr2:47476578 | Normal (15), MLH1-hm (1), MSH6 miss (1)‡ | c.2210+7G>T Splicing | NK | 1.94 | 0.68 | 0.50–0.93 | 0.02 | 0.99 | |

| MSH6 | |||||||||

| chr2:47783306 | Normal (5) | p.Ala25Ser | Class 3 | 0.51 | 1.04 | 0.61–1.76 | 0.89 | 0.96 | |

| chr2:47796058 | Normal (5) MLH1-hm (1) | p.Met208Val | Class 3 | 0.50 | 1.39 | 0.87–2.23 | 0.17 | 0.98 | |

| chr2:47801021 | Normal (2) | p.Lys1013Thr | VUS on NCBI† | 0.55 | 0.72 | 0.42–1.22 | 0.22 | 1.00 | |

| chr2:47803464 | Normal (3) | p.Pro1073Ser | Class 3 | 0.1 | 1.36 | 0.47–3.93 | 0.57 | 1.00 | |

| chr2:47803506 | Normal (14) MLH1-hm (2) MLH1 miss (1)§ | p.Pro1087Ser | Class 3† | 1.21 | 0.85 | 0.59–1.22 | 0.38 | 1.00 | |

| chr2:47806495 | Normal (3) | p.Ile1283dup | NK | 0.34 | 1.13 | 0.61–2.09 | 0.69 | 1.00 | |

| PMS2 | |||||||||

| chr7:6009009 | Normal (1) MLH1-hm (1) | p.Ala4Gly | NK | 0.04 | 2.64 | 0.62–11.2 | 0.19 | 0.98 | |

| chr7:6006003 | Normal (17) MLH1-hm (1) PMS2 fs (1) | p.Ile18Val | Class 3† | 1.73 | 0.90 | 0.67–1.21 | 0.47 | 0.99 | |

| chr7:6002515 | None | p.Val159Met | Class 3 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.15–6.31 | 0.96 | 0.96 | |

| chr7:5995539 | None | p.Ala300Pro | NK | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00–8.04 | 0.19 | 0.98 | |

| chr7:5989940 | Normal (1) | p.Asn335Ile | VUS on NCBI | 0.03 | 1.38 | 0.24–7.97 | 0.72 | 0.93 | |

| chr7:5987328 | Normal (5) MLH1-hm (1) | p.His479Gln | Class 3 | 0.30 | 1.12 | 0.58–2.15 | 0.75 | 0.98 | |

| chr7:5987315 | None | p.Pro484Thr | NK | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00–4.18 | 0.15 | 0.95 | |

| chr7:5987213 | Normal (6) MLH1-hm (1) | p.Glu518Lys | NK | 0.33 | 1.62 | 0.95–2.77 | 0.08 | 0.99 | |

| chr7:5986784 | Normal (3) | p.Glu661Lys | NK | 0.29 | 1.04 | 0.52–2.06 | 0.92 | 0.97 | |

CRC, colorectal cancer; fs, frameshift; IHC, immunohistochemistry; miss, missing on stains; MLH1-hm ,MLH1-hypermethylated; NCBI, NK=not known; pts, patients; seq, sequenced; VUS, variants of unknown significance. Info represents the imputation quality of the variant. P-values were obtained by logistic regression analysis.

*This column displays patients in the CRC cohort with the variant (either by sequencing or imputation) and their tumour MMR stain (# patients in parenthesis).

†These variants can be reclassified as benign variants based on the population frequency and low odds ratio for CRC.

‡Patient #509 with MSH6 absent on MMR tumour immunohistochemistry with possible double somatic hit (see Table 4).

§Patient #506 with MLH1/PMS2 absent on MMR tumour immunohistochemistry with double somatic hit (see Table 4).

Discussion

In this comprehensive nationwide study, WGS and imputation were combined with dMMR screening of CRC to accurately determine the prevalence of LS in the Icelandic population. LS causes 2.3% of all CRC in Iceland which is similar to the prevalence in two CRC population-based studies from Finland19 and the US6 but it is higher than LS prevalence in Southern Europe20,21,22,23. The distribution of mutations among the MMR genes in Iceland is unique. LS is predominantly caused by mutations in MSH6 and PMS2 which are responsible for 96% of all LS cases in the CRC cohort while mutations in these two genes cause 28% of LS-associated CRC in the US6. Only a single mutation in MSH2 and a single novel MLH1 translocation were found in the population.

The low rates of MLH1 and MSH2 mutations constitute a negative founder effect, that is, the founders may not have introduced MLH1 and MSH2 mutations into the population. Genetic drift, which is more common in smaller populations, may also have influenced low rates of MLH1 and MSH2 mutations. Furthermore, the higher cancer penetrance and earlier onset associated with MLH1 and MSH2 mutations may have impacted reproductive fitness. Over 50 mutations showing founder effects have been described across the world and in some populations they have a large effect on the LS gene distribution24. In Finland, two MLH1 mutations cause >50% of all LS cases19,25 and in the Netherlands26 and Sweden27, MSH6 mutations are unusually highly prevalent. The PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 mutation in Iceland shares a haplotype with cohorts from Sweden, US and Britain17. This mutation was previously dated back to around 1,625 years ago17, a time before Iceland was settled and it is likely to have entered the gene pool via one of the original settlers. The MSH6 p.Leu585Pro and PMS2 p.Met1? mutations have been described in InSiGHT and NCBI ClinVar but are not known to be founder mutations in any population. The MSH6 p.Leu585Pro mutation is clearly pathogenic in this study with a strong cancer risk association. The PMS2 p.Met1? mutation has a cancer risk association indicating that it is a pathogenic mutation. In addition, four private LS mutations were found and traced back to a single common ancestor in each family who lived in the 1700–1800s.

The MLH1 germline translocation described is to our knowledge the first case of a translocation causing LS. The translocation is passed to offspring and affected family members had close to 100% cancer penetrance. Screening for translocations where LS is suspected and germline mutations cannot be found should be considered.

The population-based prevalence of LS has been estimated in CRC and endometrial cancer studies in several countries but no country has determined the prevalence empirically. It has been postulated that LS prevalence is higher than estimated in most studies1 and here we show the highest prevalence so far of 0.442% or 1:226 individuals. Of note, the prevalence is higher than elsewhere even though the proportion of LS in CRC is just 2.3%. This is due to the markedly low cancer penetrance of the MSH6 and PMS2 mutations in Iceland as compared with cancer penetrance with MLH1 and MSH2 mutations, dominating in most populations.

One of the strengths of this study is the ability to determine cancer risk for each of the imputable mutations. This will help tailor genetic counseling in Iceland, specific to the individual mutation. The MSH6 p.Leu585Pro mutation is associated with a high (∼50%) lifetime risk of endometrial cancer while the PMS2 mutations (p.Pro246Cysfs*3 and p.Met1?) have a lower lifetime risk of cancer. One of the limitations of this study is the small size of the population, which makes it difficult to estimate the risk of rare cancers such as brain cancer (confidence intervals around odds ratios are wide).

Our two-pronged approach, of linking population-based MMR variants to a dMMR CRC phenotype, imputing these variants into the population and performing an association analysis with the cancer registry, strengthens the assumption of pathogenicity (or lack thereof). The MSH6 p.Leu585Pro mutation is described as a class 3 VUS in InSiGHT but, based on our data, should be reclassified as a pathogenic mutation. Thirteen other VUS's were not associated with a dMMR phenotype or increased cancer risks. Some of these variants can be reclassified as benign variants based on our data (variants with high population frequency and low odds ratios with narrow 95% confidence interval while others may require additional data before reclassification).

The incidence of dMMR via immunohistochemistry (11.2%) was lower than reported in many studies. In this study, an etiology was found for nearly all dMMR cases, leaving very few unexplained dMMR cases (only 0.4% of all cases remained unexplained). As 80% of all cases were genotyped, sensitivity and specificity could be calculated for the immunohistochemistry method. In three cases with the MSH6 p.Leu585Pro germline mutation, the stains were weak but present in >1% of cells (Supplementary Table 2) and a second tumour mutation was found on ColoSeq (Table 4) indicating that these tumours developed as a result of LS. In two PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 cases with strong stains ColoSeq did not detect a second tumour mutation so these patients developed a sporadic CRC unrelated to their germline mutation. Sporadic tumour development is likely more common with the lower penetrance mutations in MSH6 and PMS2.

The population-based incidence of double somatic MMR mutations in CRC is described in this study for the first time. In total, 1.4% of all CRC had double somatic MMR mutations. These cases followed the more traditional pattern of MMR mutations with 81.3% of the mutations occurring in MLH1 and MSH2. The cancer etiology in three cases with just one somatic hit in MSH2 remains unclear. The family history was unconvincing so it is unlikely that a LS mutation was missed. Nevertheless such cases present a challenge for genetic counseling. The tumour location in LS patients was left-sided or rectal in ∼50% of cases while it was predominantly right-sided in the MLH1-hm and double somatic MMR cases (>80%). It is possible that left-sidedness is more common with MSH6 and PMS2 mutations as compared with MLH1 and MSH2 mutations. Less than 10% of patients with dMMR CRC presented with metastastic disease, similar to other studies on dMMR CRC. A male predominance was seen in the LS group, a female predominance in the MLH1-hm group while the double hit sporadic tumours had a more even gender distribution.

In conclusion, this study has mapped the prevalence of LS in the Icelandic population, and its associated cancer risks and established that one in 226 Icelanders carry this syndrome. Furthermore, the contribution of different etiologies to dMMR CRC has been described. It is likely that among the population of 320,000 Icelanders, >1,000 individuals carry mutations causing LS. Identifying these individuals and establishing a cancer screening program are imperative next steps. Thirteen class 3 variants were not associated with an increased cancer risk and one class 3 variant was determined to be pathogenic; these results could guide counseling of patients with these variants. Finally, we have shown that a combined approach of phenotypic screening and population-based WGS can be used to extensively map out an inherited syndrome with a well-recognized phenotype.

Methods

CRC patient population

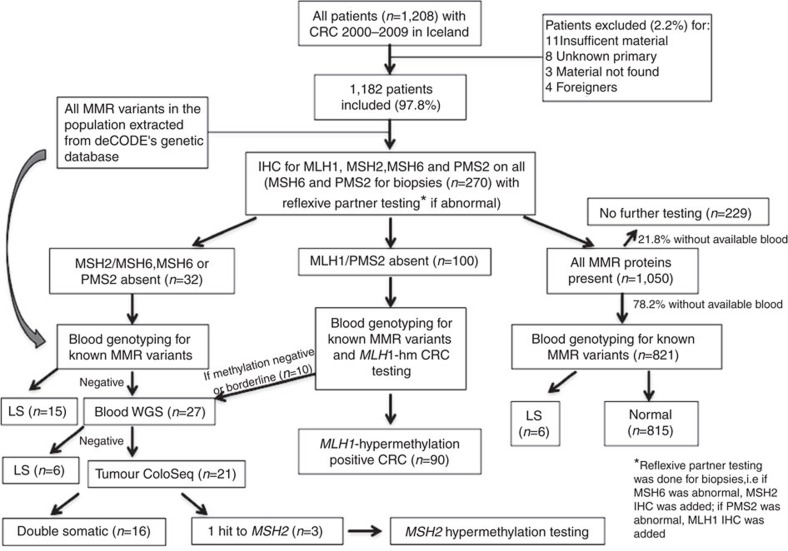

All patients diagnosed with CRC in Iceland from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009 as identified through the Icelandic Cancer Registry (http://www.krabbameinsskra.is) were included in the study. Figure 2 depicts the study design and reasons for exclusion. The Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (VSNb2013010033/03.15), the Icelandic Data Protection Authority (2013010109TS), and the Ohio State University (OSU) Institutional Review Board (2013C0144) approved this study. Descriptive statistics (median with quartiles for age and frequency for categorical variables) were provided to summarize the patient population. Cases where the origin of the primary tumour was regarded to be non-colonic (appendix, ileum and so on.) or unknown were excluded. Charts were accessed and clinical information obtained. Foreigners and patients without available tumour material were excluded. In cases of synchronous CRC, only the tumour with the most advanced stage or stage subdivision was analysed. In cases of metachronous CRC, the tumour diagnosed in the defined period was used (the first one if there were two).

Figure 2. Study design.

CRC, colorectal cancer; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LS, Lynch syndrome; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Immunohistochemistry and MLH1 hypermethylation testing

Haematoxylin and eosin stained tumour slides (obtained from Landspitali University Hospital, Akureyri Hospital and Histopathology Institute, Sudurlandsbraut) were reviewed and formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue blocks selected for further analysis. Tissue microarrays were built at the OSU Pathology Core Facility with two 1.0 mm cores from each case. Immunoperoxidase staining was performed using primary antibodies for MLH1 (Novacastra, Buffalo Grove, IL; NCL-L-MLH-1; Clone:ESO5; diluted 1:500), MSH2 (Calbiochem, [Merck Biosciences AG], Basel-Land, Switzerland; NA-27; Clone:FE11; diluted 1:3,000), MSH6 (Epitomics Inc, Burlingame, CA; AC-0047; Clone:EP49; diluted 1:800) and PMS2 (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA; 556415; clone:A16-4; diluted 1:300). Stains were scored as present with convincing nuclear staining in tumour cells with a positive internal control. In cases where only biopsies were available or rectal cancer cases where pre-radiation therapy biopsy samples were chosen, biopsies were stained for MSH6 and PMS2. If either were lost, stains were performed for MLH1 (if PMS2 lost) and MSH2 (if MSH6 lost). In cases scored as absent where no MLH1-hm or germline mutation was found, stains were repeated on a whole section (if previously done on tissue microarrays). In cases found to have LS with normal immunohistochemistry, stains were repeated on a whole section.

Tumours with MLH1 loss were tested for MLH1-hm by pyrosequencing using the Pyromark Q96 CpG MLH1 kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Up to five 1.0 mm cores were used for tumour DNA and germline DNA extraction by standard methods. Methylation levels of ≥15% were classified as positive for hypermethylation. The Pyromark Q96 CpG MLH1 kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) tests hypermethylation in four sites of the promoter region of MLH1, positions −209 to −188. Polymerase chain reaction is used to amplify the region and the degree of methylation of four CpG sites is analysed in a single pyrosequencing reaction by taking the average of four sites. In cases where only biopsy tissue was available and MLH1-hm testing failed, BRAF immunohistochemistry for the V600E mutation was performed as previously described using the VE1 antibody (1:700, incubation 15 min; Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA) with an automated staining system (Bond Autostainer; Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL)28. BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry was graded as positive for the mutation when diffuse cytoplasmic staining in tumour cells was seen.

Detection of LS mutations

The whole genomes of 8,453 Icelanders, irrespective of cancer status, were sequenced using Illumina technology to a mean depth of at least 10 × , unveiling 31.6 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and short insertions/deletions that meet stringent quality criteria. These variants were imputed into 150,656 Icelanders whose DNA had been genotyped with various Illumina SNP chips and phased using long-range phasing29,30.

All patients with dMMR tumours had germline DNA genotyped for MMR variants found by WGS of the 8,435 Icelanders. If no LS mutations were identified, WGS was undertaken on blood samples with Illumina technology or, in cases where blood DNA was not available, DNA from archived formalin-fixed paraffin embedded normal tissue was subjected to Sanger sequencing of the MMR genes. Single variant genotyping was carried out by Sanger sequencing. The PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 variant was also genotyped using PCR and size fractionation. The region around chr7:5997387 was amplified from genomic DNA from blood using conventional PCR and size fractionated on 3730 DNA Analyser (Applied Biosystems Inc.). The PMS2 p.Met1? variant was also genotyped using the Centaurus (Nanogen) platform. All primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 5. To assess the quality of the imputation, a set of imputed carriers and non-carriers of the variants were genotyped using single marker assays, comparing imputed genotypes to genotypes obtained by direct genotyping (see Supplementary Table 1).

Whole-genome genetic analyses of the Icelandic population

WGS and genotyping, imputation and association analysis used in the Icelandic population were as described15. The whole genomes of 8,453 Icelanders were sequenced using Illumina technology to a mean depth of at least 10 × (median 32 × ). SNPs and indels were identified and their genotypes called for all samples simultaneously using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK version 2.2–13)31. Genotype calls were improved by using information about haplotype sharing, taking advantage of the fact that all the sequenced individuals had also been chip-typed and long range phased. A total of 31.6 million SNPs and short indels that met stringent quality criteria were identified in the 8,453 sequenced Icelanders. These variants were then imputed into 150,656 Icelanders who had been genotyped with various Illumina SNP chips and their genotypes phased using long-range phasing29,30. Genealogical deduction of carrier status of 294,212 un-typed relatives of chip-typed individuals further increased the sample size for association analysis and increased the power to detect associations. Individuals who have any form of cancer and controls were derived from the chip-typed individuals and un-typed relatives. Association testing for case–control analysis was performed using logistic regression.

To account for inflation in test statistics due to cryptic relatedness and stratification, we applied the method of LD score regression32,33. With a set of 1.1 M variants, we regressed the χ2 statistics from our genome-wide association study scan against LD score and used the intercept as a correction factor. The LD scores were downloaded from an LD score database (see URL). For the traits reported here, the estimated correction factors were 1.15 for CRC, 1.12 for colon cancer, 1.04 for rectal cancer, 1.05 for endometrial cancer, 1.04 for ovarian cancer, 1.03 for brain cancer, 1.25 for breast cancer, 1.07 for bladder cancer, 1.02 for esophageal cancer, 1.01 for gallbladder/bile duct cancer, 1.13 for gastric cancer, 1.02 for liver cancer, 1.00 for myelodysplastic syndrome, 1.09 for pancreatic cancer, 1.22 for prostate cancer, 1.01 for renal/ureteral cancer, 1.03 for testicular cancer.

Information on cancer in the study population

Individuals affected with all forms of cancer were identified through the Icelandic Cancer Registry. The Icelandic Cancer Registry contains all cancer diagnoses in Iceland from 1 January 1955. Over 90% of diagnoses are histologically confirmed. The Icelandic Cancer Registry contains records of 4,434 Icelandic CRC patients (52% males) diagnosed from 1 January 1955 until 31 December 2013. Recruitment of cancer cases of all types was initiated in 2001 and included all prevalent cases as well as newly diagnosed cases from that time. Of the 1,685 CRC cases diagnosed from 1 January 2001–31 December 2013, 1,354 (80%) participated in our study. Patients are recruited by trained nurses on behalf of the patients' treating physicians, through special recruitment clinics. Participants in the study sign an informed consent form, donate a blood sample and answer a lifestyle questionnaire.

The median age at diagnosis for all consenting cases was 72 years, the same as that for all CRC patients in the Icelandic Cancer Registry. In addition to the chip-genotyped cases, we used information on 2,480 CRC cases without chip information whose genotype probabilities were imputed using methods of familial imputation15. The 262,425 controls (combined chip-typed and familially imputed) used in this study consisted of individuals from other ongoing genome-wide association studies at deCODE. No individual disease group is represented by more than 10% of the total control group. Samples from other cancer cases used in the cross-risk analysis come from other ongoing projects at deCODE Genetics. All subjects were of European ancestry.

All sample identifiers were encrypted in accordance with the regulations of the Icelandic Data Protection Authority. Approval for the study was granted by the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (ref. VSNb201410008/03.12) and the Icelandic Data Protection Authority (ref. 2014101449).

The Icelandic genealogy

The Icelandic genealogical database contains 819,410 individuals back to 740 AD. Of the 471,284 Icelanders recorded to have been born in the 20th century, 91.1% had a recorded father and 93.7% had a recorded mother in the database. Similarly, of the 183,896 Icelanders recorded to have been born in the 19th century, 97.5% had a recorded father and 97.8% had a recorded mother.

Haplotype analysis for the PMS2 frameshift mutation

Seven SNPs spanning exons 5–9 in the PMS2 gene were analysed in patients carrying the PMS2 p.Pro246Cysfs*3 founder mutation and compared to the haplotype found in carriers of this founder mutation in US, Swedish and British populations17. These are described in Supplementary Table 3.

MLH1 translocation, karyotyping and FISH

To scan for structural variation, all reads from the WGS data that align to the respective genes including 100 Kbp flanking regions to both sides of the genes were extracted. All reads that have a mapping quality of 0 or an average PHRED-scaled base calling quality of 25 or below were excluded. The remaining sets of reads were analysed for read pair discordance: A read was considered be part of a discordant read pair if (1) its mate is unaligned or aligns to a different chromosome or (2) the read and its mate align in unexpected orientation to each other or (3) the distance between the alignment positions of the read and its mate differ by more than three standard deviations from the mean insert size of the sequencing library. The discordant pairs that passed these filters were analysed manually for clusters where the reads align to similar positions. Suspicious clusters were further examined for alternative alignment locations of the two read ends and discarded if the location in the reference genome was repetitive. Further, clusters were discarded as common variants if present in many whole-genome sequenced controls. The only cluster that passed all filters indicates the translocation between chromosome 3 (MLH1) and chromosome 5 (ZCCHC10). The exact breakpoint positions and target-site events were inferred from 36 soft-clipped reads from the two locations on chromosome 3 and 5 in the WGS data of one patient and confirmed by 31 soft-clipped reads in a relative.

Metaphase chromosomes were harvested from PHA-stimulated (phytohaemagglutinin) lymphocytes cultured in McCoýs 5A medium with 20% fetal calf serum applying standard methods. Chromosomes were G-banded and karyotyped34. Whole chromosome FISH was performed with directly labelled StarFISH paint probes (Gambio Ltd., Cambridge, UK) for chromosomes 3 (CY3-labelled) and 5 (fitc-labelled) from Cambio, following their protocols. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Image analysis was done using Leica CW4000 FISH software and Leica DMRA2 microscope with appropriate filters for FITC and Cy3.

Somatic tumour mutation and MSH2 methylation analysis

Three micrograms of tumour DNA (1 ug in two biopsy cases) were used to perform ColoSeq tumour next-generation sequencing in dMMR cases that remained unexplained after germline mutation and MLH1-hm analysis and selected LS cases35. ColoSeq tumour is a clinical diagnostic assay that detects single nucleotide, indel and deletion/duplication mutations in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM as well as the BRAF p.V600E mutation and phenotypic MSI. The assay uses paired-end sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument to sequence all exons, introns, and flanking sequences at >300 × average coverage. LOH was determined by haplotype analysis of the variant allele fraction. Cases were considered solved if: (1) Two pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations were identified (mutations identified as class 4 or 5 or predicted to result in protein truncation); or (2) One pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutation was identified with associated LOH. Cases were considered possibly solved if only one pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutation was identified with possible LOH. Phenotypic MSI was assessed with ColoSeq tumour next-generation sequencing data using mSINGS (MSI by NGS)36.

One microgram tumour DNA was treated with sodium bisulphite using the EZ Methylation Gold kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, California), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Approximately 100 ng bisulphite-converted template was tested for the presence of methylation by two methods, quantitative CpG pyrosequencing and real-time methylation-specific PCR (qMSP) and temperature denaturation analysis, alongside the Universal Methylated Human DNA Standard (fully methylated) and Human WGA Non-Methylated DNA (unmethylated) control samples (Zymo Research, Irvine, California). CpG pyrosequencing was conducted as previously described37 with some modifications. PCR amplification was performed with 1 μM of each primer 5′-Biotin-TTTGGAAGTTGATTGGGTGTGGT-3′ and 5′-CYACTTCTCCYACATACCCTAAAAAAAAC-3′ and 3 μM MgCl2 with cycling conditions of 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 66 °C for 30 s and extensions at 72 °C for 30 s, then a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were prepared for pyrosequencing according to the standard protocol. Pyrosequencing was performed using internal primer 5′-CCACACCCACTAAACTATT-3′ with nucleotide dispensation order 5′-CTA CGA CTC CTC ATC GAT CCA GAT CAG ATC GAT ACA GAC ATC AGA TCA GAC AC-3′ on the PyroMark Q96-ID system (Qiagen). Methylation levels were measured using the PyroMark CpG Methylation software. The methylation levels were quantified at six consecutive CpG sites. Semi-quantitative methylation-specific PCR of the MSH2 promoter was performed using primers 5′-GTAGTAGTTAAAGTTATTAGCGTGCGCG-3′ and 5′-TCCTTCGACTACACCGCCATATCG-3′ with cycling conditions of 95 °C for 6 min, followed by 42 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 59 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, followed by a melt curve from 65 °C to 94 °C at 0.5 °C increments for 5 s each. A MyoD control reaction for DNA input and normalization of MSH2 methylation levels was included, as we have previously described38. Real-time qMSP was performed on the CFX-96 Real-time System (BioRad).

Data availability

The variants found in the MMR genes (pathogenic, likely pathogenic and variants of unknown significance) that support the findings of this study have been deposited in InSiGHT (https://www.insight-group.org/variants/databases/) with the accession codes (http://insight-database.org/variants/0000004813 to http://insight-database.org/variants/0000004866). LD score database (accessed 23 June 2015) ftp://atguftp.mgh.harvard.edu/ brendan/1k_eur_r2_hm3snps_se_weights.RDS. All other remaining data are available within the Article and Supplementary Files, or available from the authors upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Haraldsdottir, S. et al. Comprehensive population-wide analysis of Lynch syndrome in Iceland reveals founder mutations in MSH6 and PMS2. Nat. Commun. 8, 14755 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14755 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Tables

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Trausti Valdimarsson for his assistance with this study. This study was funded by the Ohio State University (OSU) Comprehensive Cancer Center P30 CA16058 grant (shared resource), the OSU R01-67941 grant, the OSU Colorectal Cancer Research fund, the Obrine-Weaver Fund, the Pelotonia Fellowship Award and deCODE genetics.

Footnotes

All authors from deCODE are employees of the biotechnology company deCODE genetics, a subsidiary of AMGEN. Ms Heather Hampel has received research support from Myriad Genetic Laboratories and is on the clinical advisory board for Invitae Genetics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions S. Haraldsdottir, T.R., W.L.F., H.H., P. Snaebjornsson., A.d.l.C., J.G.J., R.M.G. and K.S. conceived and designed the study. A.S., D.W., A.Y., P.G.S., M.S., M.H. and C.C.P. performed experiments. S. Haraldsdottir, T.R., A.S., G.M., B.K. and P. Sulem contributed to bioinformatics analysis. S. Haraldsdottir, T.R., A.S., G.M., B.K. and P. Sulem performed statistical analysis. S. Haraldsdottir, T.R., W.L.F., S.E., A.S., H.H., P. Snaebjornsson, G.M., D.W., R.A., B.K., A.Y., S. Haraldsson, P. Sulem, T.S., P.G.S., F.S., T.B., P.H.M., M.S., K.A., M.H., C.C.P., A.d.l.C., J.G.J., R.M.G. and K.S. contributed to data acquisition. S. Haraldsdottir, T.R., W.L.F., A.S., H.H., P. Snaebjornsson, G.M., B.K., P. Sulem, A.d.l.C., R.M.G. and K.S. analysed and interpreted the data. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. K.S. and R.M.G. supervised the study.

References

- Hampel H. & de la Chapelle A. How do we approach the goal of identifying everybody with Lynch Syndrome? Fam. Cancer 12, 313–317 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson P. & Lynch H. T. The tumor spectrum in HNPCC. Anticancer Res. 14, 1635–1639 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonadona V. et al. Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in mlh1, msh2, and msh6 genes in lynch syndrome. JAMA 305, 2304–2310 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Broeke S. W. et al. Lynch syndrome caused by germline PMS2 mutations: delineating the cancer risk. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 319–325 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487, 330–337 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel H. et al. Screening for the Lynch syndrome (Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer). New Engl. J. Med 352, 1851–1860 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M. F. et al. Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 57, 808–811 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraldsdottir S et al. Colon and endometrial cancers with mismatch repair deficiency can arise from somatic, rather than germline, mutations. Gastroenterology 147, 1308–1316.e1 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Chapelle A. Inherited human diseases: victories, challenges, disappointments. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 236–240 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasen H. F. A. et al. Revised guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): recommendations by a group of European experts. Gut 62, 812–823 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Colon Cancer (Version 1) (2017). Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf (accessed 24 Feburary 2017).

- Giardiello F. M. et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 147, 502–526 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomaki G. E., McClain M. R., Melillo S., Hampel H. L. & Thibodeau S. N. EGAPP supplementary evidence review: DNA testing strategies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome. Genet. Med. 11, 42–65 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B. A. et al. Application of a 5-tiered scheme for standardized classification of 2,360 unique mismatch repair gene variants in the InSiGHT locus-specific database. Nat. Genet. 46, 107–115 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjartsson D. F. et al. Large-scale whole-genome sequencing of the Icelandic population. Nat. Genet. 47, 435–444 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrum M. J. et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucl. Acids Res 44, D862–D868 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clendenning M. et al. A frame-shift mutation of PMS2 is a widespread cause of Lynch syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 45, 340–345 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engholm G. et al. NORDCAN: Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Prevalence and Survival in the Nordic Countries, Version 7.2 (16 December 2015). (Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries Danish Cancer Society, 2016). Available at: http://www.ancr.nu (accessed 01 January 2016)..

- Aaltonen L. A. et al. Incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and the feasibility of molecular screening for the disease. New Engl. J. Med 338, 1481–1487 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravnik-Glavac M., Potocnik U. & Glavac D. Incidence of germline hMLH1 andhMSH2 mutations (HNPCC patients) among newly diagnosed colorectal cancers in a Slovenian population. J. Med. Genet. 37, 533–536 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percesepe A. et al. Molecular screening for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: a prospective, population-based study. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 3944–3950 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñol V. et al. Accuracy of revised bethesda guidelines, microsatellite instability, and immunohistochemistry for the identification of patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. JAMA 293, 1986–1994 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berginc G., Bračko M., Ravnik-Glavač M. & Glavač D. Screening for germline mutations of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 genes in Slovenian colorectal cancer patients: implications for a population specific detection strategy of Lynch syndrome. Fam. Cancer 8, 421–429 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti G., Castellsagué E., Ruini C., Percesepe A. & Tomasi A. Mismatch repair genes founder mutations and cancer susceptibility in Lynch syndrome. Clin. Genet. 87, 507–516 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisio A. L., Sistonen P., Weissenbach J., de la Chapelle A. & Peltomäki P. Age and origin of two common MLH1 mutations predisposing to hereditary colon cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 59, 1243–1251 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsoekh D. et al. A high incidence of MSH6 mutations in Amsterdam criteria II-negative families tested in a diagnostic setting. Gut 57, 1539–1544 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederquist K. et al. Mutation analysis of the MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 genes in patients with double primary cancers of the colorectum and the endometrium: a population-based study in northern Sweden. Int. J. Cancer 109, 370–376 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth R. M. et al. A modified Lynch syndrome screening algorithm in colon cancer: BRAF immunohistochemistry is efficacious and cost beneficial. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 143, 336–343 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A. et al. Detection of sharing by descent, long-range phasing and haplotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 40, 1068–1075 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A. et al. Parental origin of sequence variants associated with complex diseases. Nature 462, 868–874 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik-Sullivan B. K. et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 291–295 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutyavin I. V. et al. A novel endonuclease IV post-PCR genotyping system. Nucl. Acids Res 34, e128–e128 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney D. E. inHuman Cytogenetics, Constitutional Analysis Vol. 3 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2001)..

- Pritchard C. C. et al. ColoSeq provides comprehensive Lynch and Polyposis syndrome mutational analysis using massively parallel sequencing. J. Mol. Diagn. 14, 357–366 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salipante S. J., Scroggins S. M., Hampel H. L., Turner E. H. & Pritchard C. C. Microsatellite instability detection by next generation sequencing. Clin. Chem. 60, 1192–1199 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titze S. et al. Differential MSH2 promoter methylation in blood cells of Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18, 81–87 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchins M. P. et al. Identification of new cases of early-onset colorectal cancer with an MLH1 epimutation in an ethnically diverse South African cohort. Clin. Genet. 80, 428–434 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Tables

Data Availability Statement

The variants found in the MMR genes (pathogenic, likely pathogenic and variants of unknown significance) that support the findings of this study have been deposited in InSiGHT (https://www.insight-group.org/variants/databases/) with the accession codes (http://insight-database.org/variants/0000004813 to http://insight-database.org/variants/0000004866). LD score database (accessed 23 June 2015) ftp://atguftp.mgh.harvard.edu/ brendan/1k_eur_r2_hm3snps_se_weights.RDS. All other remaining data are available within the Article and Supplementary Files, or available from the authors upon request.