Introduction

KEY TEACHING POINTS

|

Late complications from pacemaker leads are infrequent. The majority of lead-related issues, such as dislodgment and perforation, occur around the time of implant.1 Rarely, arrhythmias are triggered by the physical presence of the lead. We present the case of a patient with recurrent ventricular tachycardia (VT) precipitated by positional change and specific movements, and associated with a pacing lead placed 3 decades earlier.

Case report

A 53-year-old man with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries presented with recurrent syncope and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks secondary to episodes of VT despite antiarrhythmic medications. Before this, he had been relatively asymptomatic until age 20 years. At that time, he underwent ventricular septal defect repair. An epicardial pacing lead was also placed prophylactically at that time but was later abandoned. He remained asymptomatic until age 43 years, when he was noted to have severe systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation requiring valve replacement surgery. The abandoned epicardial lead was partially dissected free during the surgery but was intentionally not removed because of dense adhesions. Two years later, he underwent placement of a dual-chamber endocardial pacemaker for high-grade AV block. Several years later, the device was upgraded to a transvenous ICD because of symptomatic episodes of sustained monomorphic VT.

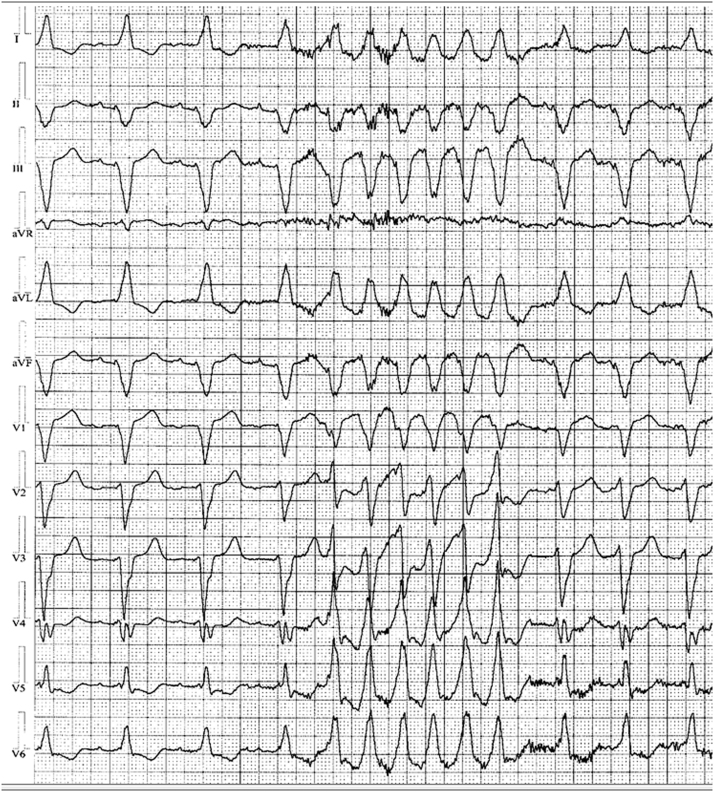

The episodes of VT increased in frequency and were associated with presyncope, syncope, and appropriate ICD therapies. Twelve-lead Holter recordings showed runs of nonsustained monomorphic VT with left bundle morphology, originating from the inferior aspect of the heart and strongly positive in lead I. Precordial transition was noted at lead V4. The maximum deflection index was measured at 0.48. Several antiarrhythmic medications failed to prevent these episodes, and the decision was made for ablation of the VT. At his initial ablation, VT was not inducible using standard programmed ventricular extrastimulation with and without isoproterenol. Using a pace-map approach, an empiric substrate-based ablation was undertaken based on the morphology from 12-lead Holter monitoring (Figure 1). A discrete area of diseased myocardium in the inferior septum of the morphologic left ventricle inferior to the ventricular septal defect patch was thought to be the culprit area. However, a 12/12 pace-map could not be identified. Linear ablation was performed there to the tricuspid valve. This particular ablation was associated with some initial improvement in symptoms as well as a reduction in ventricular events as recorded by the patient’s ICD. However, 3 after this ablation, the patient had recurrence of VT, syncope, and ICD shocks. The patient noted that he could consistently provoke these episodes with jumping or straining.

Figure 1.

Twelve-lead Holter monitor recording showing the clinical ventricular tachycardia.

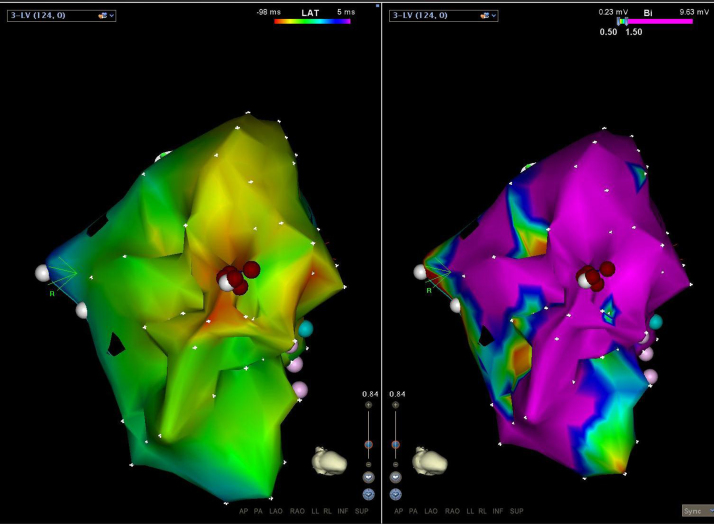

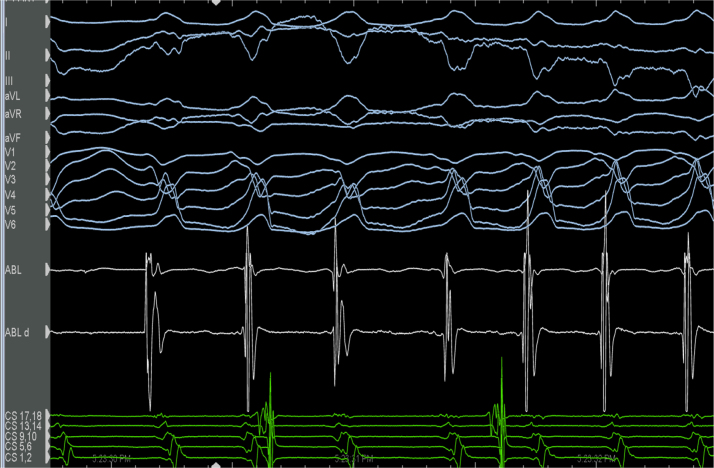

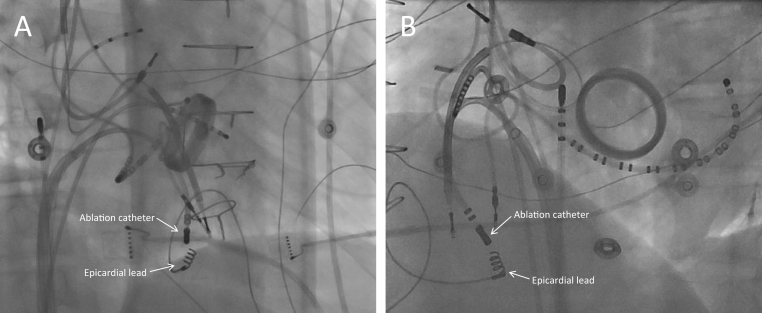

A repeat electrophysiologic study was performed, and again no ventricular arrhythmia could be induced. During the procedure, the patient was awakened and asked to perform a Valsalva maneuver. This reproducibly triggered the clinical VT. The clinical arrhythmia was found to be self-terminating and focal in nature. The source was mapped to the inferior aspect of the subpulmonic morphologic left ventricle. Substrate mapping in this area showed entirely normal myocardial characteristics. Voltage (>5 mV) was present with no evidence of electrogram fractionation or mid-diastolic potentials. The earliest ventricular electrogram was identified to be 24 ms ahead of the QRS onset, and no prepotential was seen (Figure 2, Figure 3). Importantly, this earliest site was noted to be exactly opposite the abandoned screw-in epicardial lead. The pace-map morphology from this area was found to be an 11/12 match compared with the clinical VT, and the VT was provoked with Valsalva maneuver. Despite these features, long-duration, empiric ablation lesions delivered from several different angles using high power (40–45 W) and an irrigated-tip catheter were required (Figure 4). Also, in an attempt to achieve a deeper lesion toward the epicardial surface, a nonirrigated catheter was used to deliver 80 W to the same area. After this set of lesions, the VT could not be reinduced with Valsalva provocation. Premature ventricular contractions were still present from the site with deep Valsalva, yet conversion to an epicardial approach was decided against given the patient’s history of 2 prior sternotomies and known dense adhesions. The patient has remained free of VT and ICD therapies since the ablation (2 years).

Figure 2.

Inferior view of the heart looking specifically at the subpulmonic left ventricle. Left: Activation map showing a central early point from which activation spreads outward. Right: Electroanatomic voltage map with the scale set to 0.5–1.5 mV. As evident from the map, the earliest point and ablation lesions were delivered within an area of essentially normal myocardium with voltages >1.5 mV.

Figure 3.

Ventricular tachycardia is induced with Valsalva. Twelve-lead ECG is shown, with the normal voltage electrogram noted on the ablation catheter.

Figure 4.

Fluoroscopic images from ablation showing the epicardial lead attached to the inferior surface of the subpulmonic ventricle. A: Right anterior oblique view. B: Left anterior oblique view.

Discussion

This case demonstrates that ventricular arrhythmias can be provoked by screw-in epicardial leads placed many years earlier. This rare scenario has been described for endocardial pacing and defibrillator lead tips2, 3, 4 as well as secondary to the lead shaft itself.5, 6, 7 It also has been documented with fractured and migrated epicardial leads in the setting of perforation.8, 9 In this case, the lead itself did not appear to have any abnormality, and there was no evidence of perforation on prior computed tomographic imaging. In previous similar cases, however, the offending lead was removed, which was not necessary in our patient, demonstrating that endocardial ablation was sufficient to modify the peri-lead substrate and result in noninducibility.

The trigger for VT was entirely mechanical, with the arrhythmia reliably provoked by physical actions, such as voluntary abdominal distension, bending, or jumping. This was only evident to the patient in retrospect after the initial failed ablation and suggests that traction on the lead was a key factor. This also alerts the clinician that unconventional methods of VT induction should be considered in refractory cases in which conventional pacing protocols have failed and the patient is aware of a specific precipitator.

Previous evidence suggests that epicardial (ICD) leads may have an initial proarrhythmic effect, but this occurs shortly after lead placement.10 Why this particular lead became arrhythmogenic after 3 decades of quiescence is unclear. An alteration in the position of the lead or a new area of lead fixation occurring secondary to the valve replacement surgery is a possibility. Alternatively, it may have been related to anatomic changes associated with cardiac hypertrophy or aging.

Given that there has been long-term suppression of the clinical VT, this case also demonstrates that deeper myocardial lesions are possible with longer, high-power radiofrequency ablation. Despite the lead being epicardial in nature, review of the 12-lead maximum deflection index suggests that the exit of the VT likely was not epicardial.11 Furthermore, the entirely normal voltage signals during mapping and the less than ideal electrogram to QRS duration suggest that the origin also was not endocardial. Therefore, ablation from the endocardial surface may simply have resulted in exit block from a midmyocardial source.

This case demonstrates that screw-in epicardial device leads must be considered as a trigger for VT even decades after implantation. The unusual VT provocation also is important for the clinician to consider as a mechanism of induction in patients in whom positional changes result in arrhythmia induction.

References

- 1.Udo E.O., Zuithoff N.P.A., van Hemel N.M. de Cock CC, Hendriks T, Doevendans PA, Moons KGM. Incidence and predictors of short- and long-term complications in pacemaker therapy: the FOLLOWPACE study. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W.E.I., Sarubbi B., Somerville J. Iatrogenic ventricular tachycardia from endocardial pacemaker late after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:2131–2134. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casella M., Russo A.D., Pelargonio G., Tondo C. Sustained right ventricular tachycardia originating close to defibrillator lead tip in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:994–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J.C., Epstein L.M., Huffer L.L., Stevenson W.G., Koplan B.A., Tedrow U.B. ICD lead proarrhythmia cured by lead extraction. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohm A., Pinter A., Preda I. Ventricular tachycardia induced by a pacemaker lead. Acta Cardiol. 2002;57:23–24. doi: 10.2143/AC.57.1.2005375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindsay A.C., Wong T., Segal O., Peters N.S. An unusual twist: ventricular tachycardia induced by a loop in a right ventricular pacing wire. QJM. 2006;99:347–348. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datta G., Sarkar A., Haque A. An uncommon ventricular tachycardia due to inactive PPM lead. ISRN Cardiol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.5402/2011/232648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier D.J., Tamirisa K.P., Eitzman D.T. Ventricular tachycardia associated with transmyocardial migration of an epicardial pacing wire. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1077–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01141-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwak J.G., Kim W.-H., Bae E.J. Epicardial pacemaker lead-induced ventricular tachycardia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:942–943. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S.G., Fisher J.D., Furman S., Gross J., Zilo P., Roth J.A., Ferrick K.J., Brodman R. Exacerbation of ventricular arrhythmias during the postoperative period after implantation of an automatic defibrillator. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:1200–1206. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90536-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels D.V., Lu Y.-Y., Morton J.B., Santucci P.A., Akar J.G., Green A., Wilber D.J. Idiopathic epicardial left ventricular tachycardia originating remote from the sinus of Valsalva: electrophysiological characteristics, catheter ablation, and identification from the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Circulation. 2006;113:1659–1666. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]