Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Combined loss of Ssb1/Ssb2 induces rapid lethality due to replication stress–associated loss of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

Functionally, loss of Ssb1/Ssb2 activates p53 and IFN pathways, causing enforced cell cycling in quiescent HSPCs and apoptotic cell loss.

Abstract

Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) are vulnerable to endogenous damage and defects in DNA repair can limit their function. The 2 single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding proteins SSB1 and SSB2 are crucial regulators of the DNA damage response; however, their overlapping roles during normal physiology are incompletely understood. We generated mice in which both Ssb1 and Ssb2 were constitutively or conditionally deleted. Constitutive Ssb1/Ssb2 double knockout (DKO) caused early embryonic lethality, whereas conditional Ssb1/Ssb2 double knockout (cDKO) in adult mice resulted in acute lethality due to bone marrow failure and intestinal atrophy featuring stem and progenitor cell depletion, a phenotype unexpected from the previously reported single knockout models of Ssb1 or Ssb2. Mechanistically, cDKO HSPCs showed altered replication fork dynamics, massive accumulation of DNA damage, genome-wide double-strand breaks enriched at Ssb-binding regions and CpG islands, together with the accumulation of R-loops and cytosolic ssDNA. Transcriptional profiling of cDKO HSPCs revealed the activation of p53 and interferon (IFN) pathways, which enforced cell cycling in quiescent HSPCs, resulting in their apoptotic death. The rapid cell death phenotype was reproducible in in vitro cultured cDKO-hematopoietic stem cells, which were significantly rescued by nucleotide supplementation or after depletion of p53. Collectively, Ssb1 and Ssb2 control crucial aspects of HSPC function, including proliferation and survival in vivo by resolving replicative stress to maintain genomic stability.

Introduction

The ability to maintain genome integrity upon endogenous DNA damage is critical for cell survival, self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation. Cells use a tightly coordinated DNA damage response (DDR) to either remove or repair the damage or activate an apoptotic cell death program. A defective DDR underlies a number of human diseases and developmental disorders.

A key class of proteins involved in the DDR are the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding proteins (SSBs), which are recruited to DNA damage sites to protect ssDNA.1 Replication protein A (RPA) was previously believed to be the sole SSB protein complex in eukaryotes, essential for DNA replication, repair, and recombination, and modulation of gene expression.2 Our group identified 2 additional human SSB proteins, designated as SSB1 and SSB2 (also known as NABP2/OBFC2B/SOSS-B1 and NABP1/OBFC2A/SOSS-B2), conserved from archaea to mammals.3 SSB1 and SSB2 share 73% sequence identity, with highly conserved N-terminal OB-fold domains but divergent C-terminal regions. Depletion of SSB1 in cells results in increased radiosensitivity, defective repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), oxidative DNA damage, and failure to restart stalled replication forks.3-8 Moreover, Ssb1 has been shown to regulate telomere homeostasis by protecting newly replicated G-overhangs of leading- and lagging-strand telomeres.9,10 SSB1 is recurrently mutated in various cancers, and an SSB2/RARA fusion gene has been described in variant acute promyelocytic leukemia.11

SSB1 and SSB2 independently form complexes with C9Orf80/INIP and INTS3, a component of integrator complex.4-6 The integrator complex is a 14-subunit, RNA polymerase II binding complex that controls the 3′-end processing of small-nuclear RNAs (snRNAs).12 Recent studies indicate that the integrator complex is required in many steps of the transcription cycle: 3′-end processing and termination of nonpolyadenylated snRNA and replicative histone genes, pause release at immediate early genes, and biogenesis of transcripts required from distal regulatory elements (enhancers).13-17 The association of SSB1/2 with the INTS3 complex indicates the potential for SSBs to influence transcription and RNA processing.15 Furthermore, the target sites of INTS3-SSB complexes are favorable to the formation of DNA:RNA hybrids (R-loops), structures in which nascent RNA transcripts fall back on the template DNA, leaving the nontemplate ssDNA exposed.18 R-loops are formed normally during transcription and, if not resolved properly, can become a source of genomic instability.19

In mice, Ssb1 is ubiquitously expressed, whereas Ssb2 is mainly expressed in the thymus and testis. Deletion of Ssb1 leads to perinatal lethality due to highly abnormal patterning of the dorsal rib cage.9,20-22 Ssb1 conditional knockout20 or Ssb1 hypomorphic mice9 are viable long term and show increased tumor incidence after late latency and are radiosensitive. However, Ssb2 knockout mice develop to term and have no overt pathological phenotype.23 Strikingly, Ssb2 shows pronounced upregulation in Ssb1−/− tissues, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), and hypomorphic Ssb1F/F tissues,9,20,21 whereas a modest upregulation of Ssb1 is observed in thymus and spleen from Ssb2−/− mice and Ssb2−/− MEFs.23 This compensatory upregulation suggests that Ssb1 and Ssb2 may have overlapping functions in vivo.

Here, we report that constitutive Ssb1/Ssb2 double knockout (DKO) mice are early embryonic lethal and that conditional Ssb1/Ssb2 double knockout (cDKO) in adult mice results in unexpected acute bone marrow failure and intestinal atrophy due to loss of rapidly proliferating progenitor cell populations, phenotypes that are reminiscent of acute ionizing radiation toxicity. We observed replication stress, DSBs, and R-loop accumulation accompanied by transcriptional activation of p53 and interferon (IFN) pathways in cDKO hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). This resulted in enforced cell cycle entry of quiescent HSPCs, followed by apoptotic cell death. In conclusion, Ssb1 and Ssb2 coordinately restrict HSPC proliferation and promote HSPC survival by resolving replication/transcription-associated DNA damage and R-loop accumulation.

Materials and methods

Experimental mice and phenotypic analysis

All experimental animals were maintained on a C57BL/6J strain in a pathogen-free animal facility. All procedures were approved by the QIMR Berghofer animal ethics committee (A11605M and A0707-606M). Peripheral blood was collected by retro-orbital venous blood sampling and analyzed on a Hemavet analyzer (Drew Scientific). Tissues were collected and fixed in 10% buffered formalin fixative, embedded in paraffin blocks, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological examination. Immunostaining methods and antibodies used are described in the supplemental Materials and Methods, available on the Blood Web site. All western analyses were performed on the LICOR platform (Biosciences). Bone marrow (BM) cells were harvested by flushing femur and tibia bones. Various BM stem and progenitor populations were purified, as described.24 For cell cycle analysis, cells were fixed and permeabilized (FIX & PERM kit, Invitrogen) and stained with Ki-67 (B56) and Hoechst 33342 (20 μg/mL, Invitrogen). All flow cytometric analysis was performed on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences).

Competitive BM transplantation

BM cells derived from 6- to 8-week-old control or cDKO mice (expressing CD45.2) were combined with equal numbers of CD45.1 congenic competitor BM cells, and injected into the lateral tail vein of lethally irradiated (11 Gy in 2 separate fractions at least 3 h apart) CD45.1/CD45.2 congenic recipient mice (Animal Resource Centre, Western Australia).

In vitro apoptosis rescue assay

BM cells were harvested under sterile conditions from naïve Rosa26-CreERT2;Ssb1+/+Ssb2+/+ mice (n = 5) and Rosa26-CreERT2;Ssb1flflSsb2fl/fl mice (n = 5). Lineagelowc-Kit+Sca−1+ (LKS) cells were purified as previously described.24 Retroviral Hoxb8-producing fibroblasts were seeded in a 10-cm plate at 1 × 105 in a low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. After 24 hours, 5 × 105 sorted LKS cells were cultured atop a layer of Hoxb8-transformed fibroblasts in the presence of 0.25 ng/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3).25 After 4 days in culture, nonadherent cells were passaged into 12-well plates and used in subsequent apoptosis assays by staining with annexin V (BD Biosciences) and Sytox blue (Invitrogen). EmbryoMax nucleoside supplement (Merck Millipore) was added to individual wells, where indicated at 1:100.26,27 To knockdown p53, we plated cells on Retronectin-coated plates (Takara) and spinoculated them with lentiviral p53-short hairpin RNA (shRNA)28 or luciferase-shRNA (control) at a multiplicity of infection of 10, in the presence of 4 μg/mL of polybrene at 2500 rpm at 30°C for 90 minutes.

DNA damage and genomic instability analysis

For immunostaining, DNA combing and comet assay on HSPCs, whole BM were harvested from control and cDKO littermate mice at 48 hours after 4 mg of tamoxifen (TAM) and sorted for LKS+ (lineagelowc-Kit+Sca-1+) cells. Cells were cultured for 16 hours prior to processing, as described.29 Preparation of metaphases and chromosome aberration analysis was done, as described.20,30 Telomere fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) at metaphases was performed as described previously.31

Direct in situ single-nucleotide resolution labeling and capture of genome-wide DSBs in nuclei were performed using the Breaks Labeling, Enrichment on Streptavidin and next-generation Sequencing (BLESS) technique, as described previously and in the supplemental Materials and Methods.32

Results

Ssb1 and Ssb2 are essential for early embryogenesis

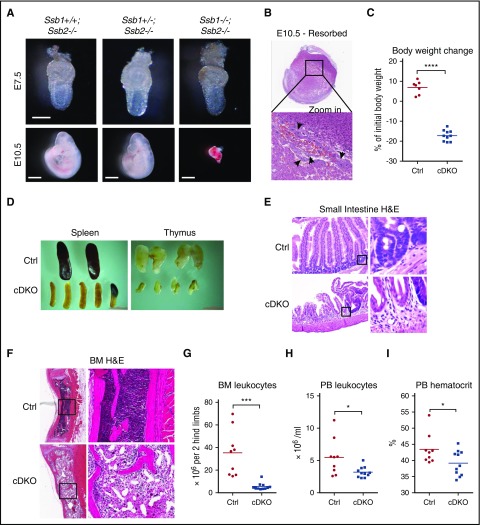

Ssb1+/−Ssb2−/− mice were intercrossed to generate embryos at specific stages. Timed matings revealed that, although Ssb1+/+Ssb2−/−, Ssb1+/−Ssb2−/−, and Ssb1−/−Ssb2−/− (DKO) were recovered at the expected Mendelian ratios at E7.5, no DKO embryos could be recovered at E10.5 (Figure 1A; quantified in supplemental Table 1). Instead, resorbed embryos with apoptotic bodies were observed in the expected proportion (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Early embryonic lethality in constitutive Ssb1/Ssb2 double knockout (DKO) mice and acute mortality in conditional Ssb1/Ssb2 double knockout (cDKO) mice due to BM failure and small intestine atrophy. (A) Embryos at E7.5 (upper panel; scale bar = 200 μm) and E10.5 (lower panel, scale bar = 1 mm) from Ssb1+/−;Ssb2−/− intercrossed, timed matings. (B) Histologic analyses of resorbed embryos from E10.5. Apoptotic bodies are indicated by black arrows. Images were acquired at ×1 (top) and ×40 (bottom) magnification. (C) Body weight change on day 7 of TAM-induced adult Ctrl and cDKO mice. (D) Representative images of spleen and thymus recovered from Ctrl and cDKO mice on day 7 postinduction with TAM (1 mg/day by IP injection for 5 consecutive days). (E) H&E staining of small intestine sections. Images were acquired on day 7 postinduction at ×20 (left) magnification and zoomed in ×16 for indicated areas (right). (F) H&E staining of BM sections. Images were acquired on day 7 postinduction at ×4 (left) and ×20 (right) magnifications. (G) BM cell count. (H-I) Leukocyte and hematocrit counts in peripheral blood (PB) from Ctrl and cDKO mice on day 7 postinduction with TAM (1 mg/day by IP injection for 5 consecutive days). Statistical analysis represents t test. Each point represents an individual mouse/biological replicate. See also supplemental Figure 1. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

Somatic deletion of Ssb1 and Ssb2 in adult mice triggers rapid lethality

We used a conditional approach to delete Ssb1 and Ssb2 across a broad range of tissues in adult mice using the TAM-inducible Rosa26-CreERT2 strain.33 Individual genotypes of Ssb1 and Ssb2 were generated as follows: Ssb1+/+Ssb2+/+ (wild-type [WT]), Ssb1fl/+Ssb2fl/+ (Dbl het [double heterozygous]), Ssb1fl/flSsb2fl/+ (1ko [knockout],2het), Ssb1fl/+Ssb2fl/fl (1het,2ko), and Ssb1fl/flSsb2fl/fl (cDKO). Cre-mediated recombination was induced with TAM (1 mg/d by intraperitoneal injection for 5 consecutive days). cDKO mice displayed 15% body weight loss within 7 days after TAM induction and became moribund, whereas mice of all the other genotypes maintained normal body weight in the same period (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1A-B). The knockout efficacy in BM, spleen, and thymus was confirmed (supplemental Figure 1C).

cDKO causes bone marrow failure and small intestine atrophy

cDKO spleens and thymuses were smaller and paler than were those in controls (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 1D). cDKO small intestines showed profound shortening of villi and marked thinning of the mucosa, resembling villous atrophy due to damage to crypt resident proliferative progenitors (Figure 1E),34,35 whereas other tissues remained grossly intact (data not shown). BM hypocellularity was observed in cDKO sections, featuring trilineage reduction in hematopoiesis with fatty replacement (Figure 1F-G). Analysis of the cDKO peripheral blood showed leukocytopenia and anemia (Figure 1H-I; supplemental Figure 1E-F), with preservation of platelets (supplemental Figure 1G). The acute BM and intestinal damage of both highly proliferative tissues are comparable to those found in acute ionizing radiation toxicity.36 These findings indicate that Ssb1 and Ssb2 are collectively essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis in vivo.

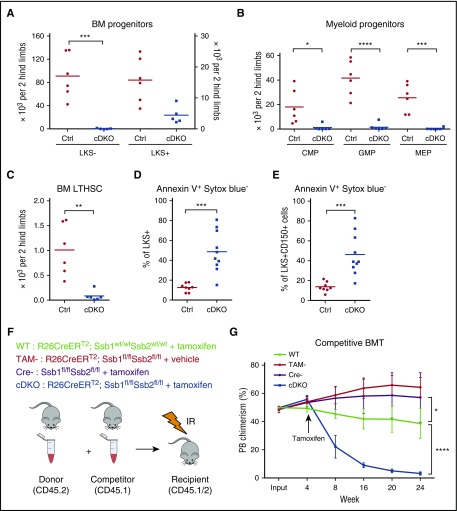

cDKO causes loss of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) by apoptosis and impairs long-term hematopoietic stem cell (LTHSC) function

All blood cell lineages are thought to be derived from LTHSCs, which have the ability to self-renew and differentiate into multipotent and lineage-committed blood cells.37 Recent data suggest that homeostatic hematopoiesis is supported primarily by progenitor populations.38,39 The longevity and proliferative capacity of myeloid progenitor cells renders them particularly susceptible to DNA damage.40 Analysis of BM populations by flow cytometry revealed a dramatic reduction in committed myeloid progenitor cells (lineagelowc-Kit+Sca-1−; LKS−) in cDKO BM (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 2A), whereas lineagelowc-Kit+Sca-1+ (LKS+, enriched for HSPC) cDKO cells were expanded in frequency, but not absolute number because of BM hypocellularity (Figure 2A), and exhibited a marked induction of Sca-1 expression and slight decrease in c-Kit intensity (supplemental Figure 2A). Phenotypic common myeloid progenitors (lineagelowc-Kit+Sca-1−CD34+CD16/32−) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP; lineagelowc-Kit+Sca-1−CD34+CD16/32+) were proportionally expanded in cDKO BM (supplemental Figure 2A-B) but reduced in absolute numbers in comparison with WT (Figure 2A). Megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEP; lineagelowc-Kit+Sca-1−CD34−CD16/32−) were drastically diminished in both frequency and absolute number in cDKO BM (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 2A). Long-term hematopoietic stem cells (LTHSCs; lineagelowc-Kit+Sca-1+CD150+CD48−) were markedly reduced in cDKO BM (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 2A). To exclude the impact of Sca-1 induction in cDKO BM, we quantified lineagelowc-Kit+CD150+CD48− cells. Indeed, we still observed a profound reduction of lineage low c-Kit+ cells and lineage low c-Kit+CD150+CD48− cells in cDKO BM (supplemental Figure 2C-D). Furthermore, both cDKO LKS+ and CD150+ cells showed a marked increase in annexin V+ cells (Figure 2D-E; supplemental Figure 2E), suggesting that cDKO BM cells were depleted because of apoptotic cell death. Furthermore, we found that expression of a single allele of either Ssb1 or Ssb2 is sufficient to rescue the cell loss phenotype and restore peripheral blood leukocyte/hematocrit and BM LKS+/LTHSCs (supplemental Figure 2Fa-d).

Figure 2.

cDKO causes loss of HSPCs through apoptotic cell death and loss of repopulating potential in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). (A-C) Cell numbers of BM progenitors (A), myeloid progenitors (B), and LTHSCs (C) from 2 hind limbs. (D-E) Frequency of apoptotic cells in LKS+ (D) and CD150+ cells (E). (F) Experimental scheme. Whole BM cells from either non-TAM treated WT or cDKO animals (expressing the CD45.2 allele) were mixed with an equal number of congenic whole BM (CD45.1) and injected into lethally irradiated recipients (CD45.1/CD45.2). (G) Peripheral blood was monitored to measure bone marrow chimera establishment in recipient mice on week 4. cDKO was induced in 4 weeks posttransplantation. TAM or vehicle control was administered, and the percentage of donor chimerism was measured at indicated time points. Statistical analysis represents t test or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Each point represents an individual mouse/biological replicate. See also supplemental Figure 2. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001. ****P < .0001. IR, irradiated.

To investigate the functional potential of cDKO LTHSCs in greater depth, we performed in vivo competitive BM transplantation assays (Figure 2F). Once equivalent engraftment of donor cells of all genotypes was confirmed at 4 weeks, the recipient mice were treated with 1 mg of TAM once daily for 5 days. The induced genetic deletion of Ssb1 and Ssb2 led to the gradual depletion of cDKO donor cell chimerism, as evidenced by the progressive loss of CD45.2 cells from the peripheral blood, whereas all other genotype cohorts sustained stable engraftment for 24 weeks posttransplant (Figure 2G). When the BM was assessed in the recipients at 24 weeks posttransplant, cDKO CD45.2, LKS− and LKS+ populations were dramatically reduced in comparison with other groups, indicating that cDKO cells were unable to sustain long-term hematopoiesis (supplemental Figure 2G-I). These findings demonstrate that both Ssb1 and Ssb2 are required for in vivo HSPC maintenance in a cell-autonomous manner.

cDKO causes replication stress and DNA damage in HSPCs

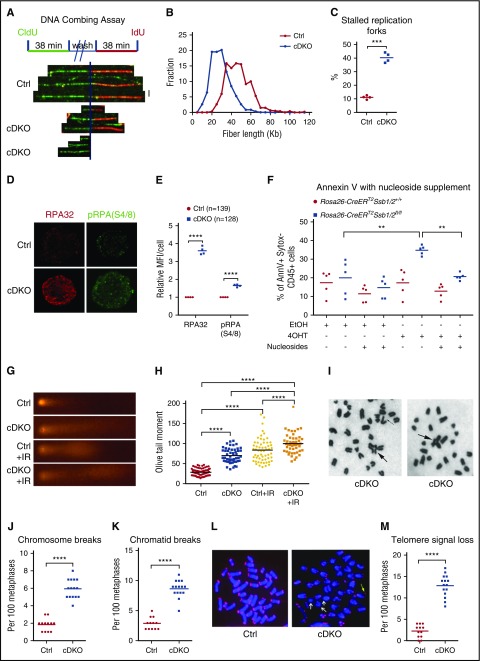

To shed light on the mechanism of HSPC loss, we analyzed DNA replication fork dynamics. BM LKS+ cells were isolated from control or cDKO mice at 48 hours after 1 injection of 4 mg TAM, cultured for 16 hours, and pulse labeled with the thymidine analog chlorodeoxyuridine (CldU), followed by iododeoxyuridine (IdU). DNA was combed onto glass slides and CldU and IdU incorporation in nascent DNA fibers was detected by fluorescent staining (Figure 3A).29 Control LKS+ cells displayed longer elongating fiber lengths representing a fork speed distribution centered around a mean fork velocity of 1.61 kb/min, whereas cDKO cells had shorter fiber lengths overall with a mean velocity of 0.99 kb/min, highlighting a significantly slower DNA replication fork rate in cDKO cells (Figure 3B). We did not observe asymmetric replication in cDKO cells as found previously in old HSCs (supplemental Figure 3A).29 We did, however, observe a significantly increased percentage of stalled replication forks (Figure 3C). These findings correlated with a strong enrichment of RPA foci and phosphorylated RPA (S4/8) in cDKO HSPCs (Figure 3D-E), indicating the presence of extensive ssDNA at replication forks, a hallmark of replication stress.

Figure 3.

Replication stress and genomic instability in cDKO HSPCs and BM. (A-C) DNA fiber assay on HSPCs. (A) LKS+ cells were isolated on day 2 after 4 mg of TAM, cultured for 16 hours, and sequentially pulsed with 2 different thymidine analogs, CldU and IdU. Replication fork movement was measured by incorporation of CldU (green) and IdU (red). (B) Distribution of red fiber length of ongoing forks. At least 300 structures were measured per sample per experiment, and quantification on 4 independent experiments was presented. (C) The frequency of terminated fibers that did not incorporate the second label in at least 300 structures per sample per experiment from 4 independent experiments. (D) Representative images of immunofluorescent staining of RPA (red) and phosphorylated RPA (S4/8) (green). Images were acquired at ×100 magnification. (E) Quantification of relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) from 4 independent experiments. Each data point represents the relative MFI in cDKO HSPCs normalized to that in Ctrl HSPCs. The n represents total number of cells. (F) EmbryoMax nucleoside supplement or vehicle (dH2O) was added to Hoxb8-immortalized cells with indicated treatment. Annexin V was analyzed for apoptotic cell death 5 days after in vitro 4OHT induction of cDKO. AnnV, annexin V. (G-H) Alkaline comet assays on LKS1 cells (G) and olive tail moment (H) from indicated groups before or at 1 hour after 2 Gy of ionizing radiation. Each point represents an individual cell from pooled biological replicates from 4 independent experiments. (I-M) Bone marrow metaphase spreads on day 3 after 4 mg of TAM. Representative images for Giemsa (I) and telomere FISH staining (L), chromosome aberration (J-K), and telomere signal loss (M) analysis are shown. Radial chromosomes, chromosomal breakages, and telomere signal loss are indicated by arrows. Images were acquired at ×63 magnification. Each point represents a biological replicate. Statistical analysis represents t test or 1-way ANOVA for 2 or multiple groups, respectively. See also supplemental Figure 3. **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

Altered DNA replication, in particular increases in DNA replication stalling events, can generate DSBs. Consistent with this, we observed focal accumulation of the DSB marker phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX) in cDKO HSPCs (supplemental Figure 3B-G), suggesting defective DSB repair. To investigate whether replication stress is causative of apoptotic death in cDKO LKS+ cells, we first established Hoxb8-immortalized LKS+ cells in vitro to directly monitor their growth and cell death after 4OHT induction, independent of what is likely a strongly proinflammatory environment in the cDKO animal. Overexpression of Hoxb8 has been shown to immortalize IL-3-dependent myeloid progenitor cells by blocking differentiation of these cells to arrest them in a self-renewing state.25,41 4OHT-mediated cDKO in LKS+ cells was sufficient to induce apoptosis in vitro by day 6 (supplemental Figure 3H). We next treated cells with EmbryoMax nucleosides (Merck Millipore) to relieve cDKO cells of replicative stress26,27 and observed decreased apoptosis in 4OHT-induced cDKO cells supplemented with nucleosides in comparison with those treated with vehicle (Figure 3M; supplemental Figure 3I). These findings demonstrate that replication stress is a major effector of cell death in cDKO.

Furthermore, using alkaline comet assays, we showed that cDKO LKS+ cells displayed higher baseline and radiation-induced DNA damage in comparison with control cells (Figure 3G-H). cDKO bone marrow metaphases demonstrated a significant increase in spontaneous chromatid and chromosomal breakage (Figure 3I-K), as well as telomere signal loss (Figure 3L-M), which was only evident in the conditional Ssb1−/− bone marrow metaphases after exposure to genotoxic insult.20 These results provide in vivo evidence to suggest that Ssb1 and Ssb2 may have overlapping roles in regulating HSPC function in genome maintenance by resolving replication stress.

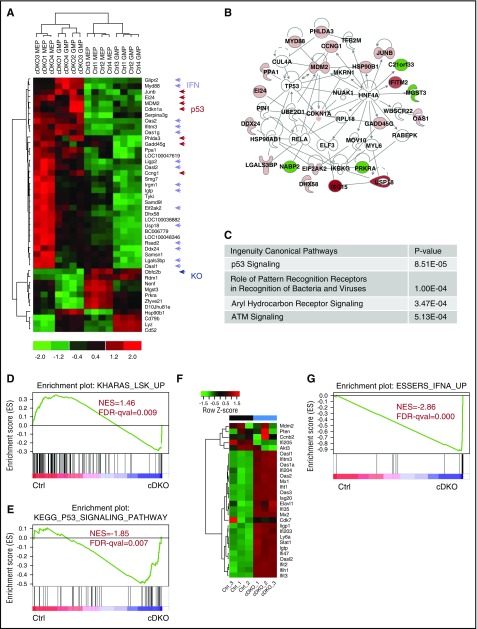

cDKO activates the interferon and p53-mediated apoptosis pathways in HSPCs

Next, we performed microarray analysis on purified MEP and GMPs from control and cDKO mice 2 days after TAM induction to gain insight into the molecular determinants and cellular pathways involved. The key upregulated genes in cDKO MEP and GMP were interferon-α (IFNα), IFN-β, and p53 target genes (Figure 4A), which belong to an integrated network (Figure 4B). Notably, Ssb1 (Obfc2b) was the most downregulated gene (Figure 4A). Ingenuity pathway analysis identified p53, antigen presentation, aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), and ATM signaling as the top canonical pathways affected by cDKO in MEP or GMP (Figure 4C). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) also revealed enrichment of apoptosis and immune response functions in cDKO-regulated genes (data not shown). This finding was validated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction on independent samples for which cDKO HSPC exhibited significant downregulation of Ssb1 and Ssb2 (data not shown) and upregulation of IFN-regulated transcripts (Myd88, Oas1g, Oas2, Ifitm3, and Irgm1; supplemental Figure 4A-B) and p53 DNA damage genes (JunB, Gadd45b, Gadd45g, Mdm2, and Cdkn1a; supplemental Figure 4C-D). These analyses suggest that depletion of both Ssb1 and SSb2 activates transcriptional IFNα/β and p53 responses, which may converge to induce apoptosis.

Figure 4.

cDKO mediates p53 pathway and IFN system activation in HSPCs. (A) Heat map of commonly up- and downregulated transcripts in cDKO MEP and GMP from microarray analysis. (B) Networks enriched in cDKO MEP and GMP by ingenuity pathway analysis of protein–protein interaction databases only; network name: Cell Cycle, Antimicrobial Response, and Inflammatory Response. (C) Top 4 overlapping canonical signaling pathways and P values for enrichment in cDKO MEP and GMP. (D-G) GSEA of RNA-seq analysis of LKE+CD48− cells showing loss of stemness signature (D), p53 pathway activation (E), and interferon activation (F-G) in cDKO HSCs. See also supplemental Figure 4. FDR-qval, false discovery rate q value; NES, normalized enrichment score.

To validate whether IFN and p53 were also activated in cDKO HSCs, we performed RNA sequencing analysis on sorted CD48−LineagelowcKit+ESAM+ (LKE+; ESAM used in place of Sca142) HSCs from Rosa26-CreERT2Ssb1+/+/Ssb2+/+ (control [Ctrl]) and Rosa26-CreERT2Ssb1 fl/fl/Ssb2fl/fl (cDKO) mice at 48 hours after TAM induction. Gene expression was distinct for each genotype (supplemental Figure 4E). GSEA analysis revealed the loss of a LKS self-renewal signature43 in cDKO HSCs (Figure 4D). p53 pathway was upregulated in cDKO HSCs (Figure 4E) and the IFN genes were dramatically enriched in cDKO HSCs (Figure 4F-G; supplemental Figure 4E-F) suggesting transcriptional activation of IFN and p53 pathways accompany this replicative and pro-apoptotic phenotype. Similarly, this IFN gene signature is present in in vitro cultures of Hoxb8-immortalized LKS+ cDKO cells after 4OHT induction (supplemental Figure 4G), indicating the HSC-autonomous nature of IFN production.

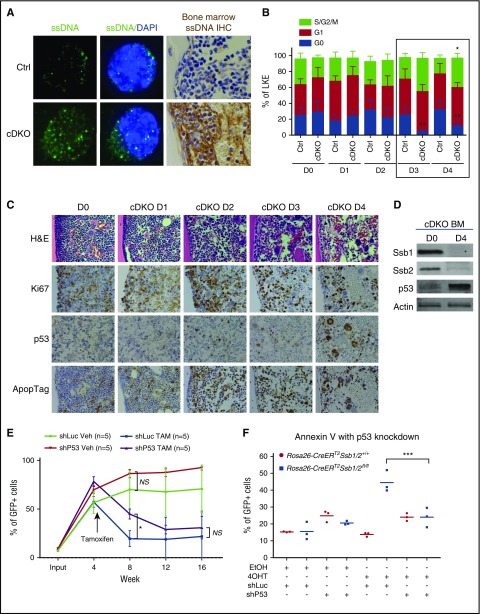

Cytosolic ssDNA in cDKO cells prime HSCs to exit quiescence and enter the cell cycle

Accumulation of unrepaired DNA lesions has recently been shown to activate the type I IFN pathway and inhibit stem cell function through the release of ssDNA into the cytoplasm.44-46 Consistent with this, cDKO HSPCs and BM sections showed the presence of ssDNA in the cytoplasm (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 5A), as with that of positive control cells (Ctrl HSPCs treated with aphidicolin or lipopolysaccharide) (supplemental Figure 5B). Functionally, IFN signaling is reported to force HSCs to exit quiescence and enter the cell cycle, leaving them vulnerable to DNA damage.47,48 We analyzed the cell cycle profile of BM LKE+42 from day 0 to day 4 after a single dose of 4 mg TAM intraperitoneal (IP) injection. Notably, a significantly increased percentage of cDKO LKE+ cells lost quiescence (G0) and became more proliferative (S/G2/M) on D3 and D4 (Figure 5B). This finding was validated in highly enriched HSC fractions lineagelowcKit+CD150+CD48− on D3 post-cDKO (supplemental Figure 5C). Similarly, immunostaining on BM tissues from the corresponding time course showed a transient burst of proliferation, followed by p53 stabilization and apoptotic cell death (Figure 5C-D).

Figure 5.

Cytosolic ssDNA primes cDKO HSPC exit from quiescence, and p53 activation leads to apoptotic cell death in cDKO BM. (A) Immunofluorescent staining shows ssDNA (green) presence in the cytoplasm of LKS+ cells (left panel) and immunohistochemistry staining of cytosolic ssDNA (brown) on BM sections of cDKO mice on day 3 after 4 mg of TAM. Images were acquired at ×100 magnification. (B) Cell cycle analysis of BM LKE+ cells in a time course of 4 days after cDKO. (C) Histological analysis of H&E and immunohistochemistry staining of Ki67, p53, and ApopTag. Images were acquired at ×40 magnification. (D) Western blot showing Ssb1, Ssb2, and p53 levels in cDKO BM samples on D0 and D4 after 4 mg of TAM. (E) LKS+ cells (CD45.2) were isolated from donors, transduced with shLuc-GFP or shP53-GFP, mixed in a 1:1 ratio with competitor BM (CD45.1), and transplanted into irradiated recipient mice. cDKO was induced in 4 weeks posttransplantation. Peripheral blood was monitored to measure bone marrow chimera percentage in recipient mice every 4 weeks post-TAM (cDKO) or vehicle control administration until week 16. (F) Hoxb8-immortalized LKS+ cells were transduced with control (shLuc-GFP) or p53 (shP53-GFP) shRNAs. Apoptosis was measured 5 days after in vitro 4OHT induction of cDKO. Statistical analysis represents 2-way ANOVA. Each point represents an individual mouse/biological replicate. See also supplemental Figure 5. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NS, not significant; Veh, vehicle.

In an effort to rescue the phenotype by knocking down p53, LKS+ cells were isolated from a non-TAM treated Rosa26CreERT2Ssb1fl/flSsb2fl/fl donor mouse and transduced with control (shRNA against luciferase [shLuc]–green fluorescent protein [GFP]) or p53 shRNA (shP53-GFP),28 sorted for GFP+ cells, combined with competitor CD45.1 BM cells, and then transplanted into irradiated syngeneic WT recipient mice (supplemental Figure 5D). TAM was injected at 4 weeks posttransplant. A trend of increased reconstitution capacity was observed after knocking down p53 (supplemental Figure 5E), although this was inadequate to rescue function over the long term (Figure 5E), suggesting that either additional pathways limit HSPC function in cDKO HPSC or complete p53 knockout may be required for full rescue. To demonstrate that p53-mediated apoptosis is functional in the short term in cDKO, we transduced Hoxb8-immortalized LKS+ cells with control (shLuc-GFP) or p53 (shP53-GFP) shRNAs. We observed a significant increase in apoptosis in 4OHT-induced shLuc-transfected cDKO cells, but no increase in 4OHT-induced cells transfected with shP53, suggesting that p53 knockdown in vitro is able to temporarily prevent cDKO-induced cell death (Figure 5F; supplemental Figure 5F).

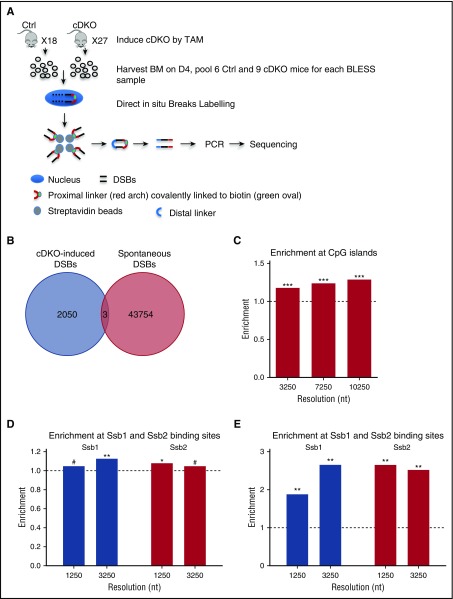

cDKO induces specific genome-wide double-strand breaks enriched at CpG islands and transfer RNAs (tRNAs)

To map the distribution of genome-wide DSBs at nucleotide (nt) resolution, we applied direct in situ BLESS32,49 on whole BM from control and induced cDKO mice at day 4 after a single dose of 4 mg TAM IP injection (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Enrichment of CpG islands and tRNAs in cDKO-induced breaks and all DSBs in cDKO BM. (A) Experimental scheme of BLESS analysis to map genome-wide DSBs. From pooled BM samples of Ctrl and cDKO mice on day 4 after 4 mg of TAM, intact nuclei were purified, and DSBs were ligated to a biotinylated linker (proximal). Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted and fragmented, and labeled fragments were captured by streptavidin and ligated to a secondary linker (distal), PCR amplified, and sequenced. (B) Venn diagram showing regions with cDKO-induced DSBs (BLESS cDKO vs BLESS Ctrl) and spontaneous DSBs (BLESS Ctrl vs gDNA Ctrl) with a P value threshold P < .001 and 1250-nt resolution. (C) Enrichment of CpG islands in cDKO-induced breaks. (D) Enrichment of Ssb1- and Ssb2-binding sites from HIT-Seq data15 in intervals enriched with DSBs from BLESS data. (E) Enrichment of CpG islands in intervals enriched with Ssb1- and Ssb2-binding sites using the same method as that in BLESS data analysis (described in the supplemental Materials and Methods). Significance of enrichment is calculated by permutation test. See also supplemental Figure 6. #Borderline significant, .05 < P < .1; *P < .05; **P < .01.

At the resolution of 1250 nt and at a P value threshold of P = .001 (hypergeometric test), we detected 43 757 genomic regions enriched in spontaneous DSBs (in control BM cells) and 2053 cDKO-induced fragile regions (supplemental Materials and Methods; supplemental Table 3). Strikingly, cDKO-induced breaks occur in different locations than did spontaneous DSBs in control BM cells (hypergeometric test; P < 10−323) (Figure 6B) and did not correlate with previously described common fragile sites.50,51 Fragility of whole genes was independent of gene length (supplemental Materials and Methods; supplemental Table 4). Strikingly, we observed very significant enrichment of CpG islands at different resolutions in DSB-enriched regions (Figures 6C). We also detected borderline significant enrichment of cDKO-induced DSBs in 2-kb promoter-proximal region (supplemental Figure 6A). Moreover, we observed significant enrichment of DSBs in the vicinity of sentinel highly expressed genes (tRNAs) and all transcripts, versus lowly expressed genes (retrogenes), suggesting that cDKO-associated DSBs are related to highly expressed genes (supplemental Figure 6B-C). We also analyzed colocalization of DSBs and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to gain evolutionary perspective. Common SNPs were 1.2-fold enriched, and SNPs in coding regions showed up to 2.7-fold enrichment at cDKO-associated breaks (supplemental Figure 6D). Again, enrichment was highest within a 1- to 3-kb vicinity of a coding SNP.

Furthermore, we reanalyzed HIT-Seq data, for which Skaar et al15 have mapped genome-wide binding sites of Ssb1 and Ssb2, using the same method applied for the BLESS data, and analyzed the enrichment of Ssb1 and Ssb2 binding sites (from HIT-Seq data) in the regions enriched with cDKO-induced DSBs (from BLESS data) at different resolutions. We observed significant enrichment of Ssb1- and Ssb2-binding sites in intervals enriched with cDKO-induced DSBs (Figure 6D; supplemental Table 6). Moreover, we detected enrichment of CpG islands in intervals enriched with Ssb1- and Ssb2-binding sites (Figure 6E; supplemental Table 7) as well as in those enriched with the cDKO-induced DSBs (Figure 6C). When we specifically considered the aforementioned LKS (stemness) signature (Figure 4D), there were 9 genes allocated within the regions enriched with cDKO-specific DSBs identified by BLESS. Among these genes, 7 were differentially expressed, with 6 showing a decrease in expression in cDKO in comparison with Ctrl (FDR ≤ 0.05). The exception was Gbp10, an interferon-inducible gene, which was predictably increased (supplemental Figure 6E).

Altogether, assuming that induction of DSBs is rare and the ones we observe occur in a small fraction of cells and are detectable only because of a very sensitive BLESS detection technique, we hypothesize that the deleterious effects of cDKO-induced DSBs occur initially in the context of transcriptionally active genes, but also through dominant effects of downstream transcriptional pathways such as the IFN and p53 pathways.

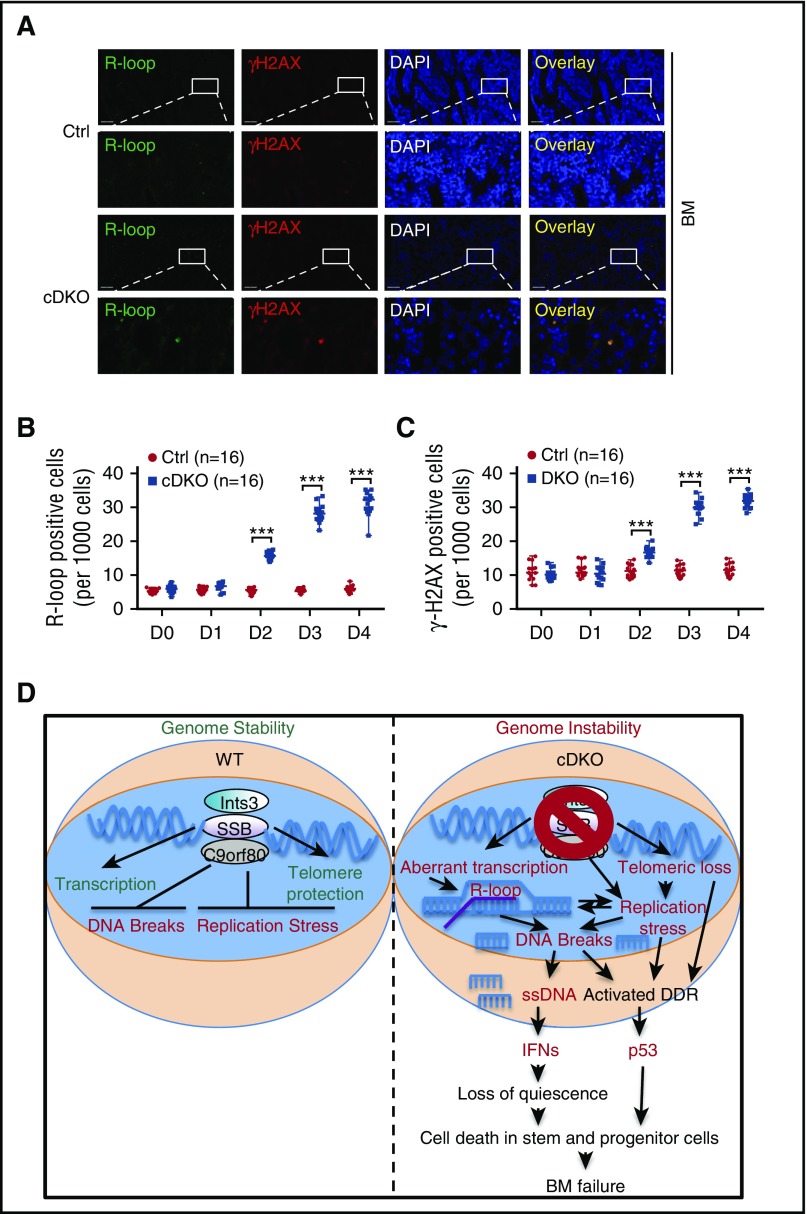

cDKO leads to R-loop accumulation

INTS3-SSB complexes have previously been shown to be enriched at the GC-rich regions of transcription start sites and transcription termination sites as well as open chromatin states favorable to R-loop formation.18,52,53 Interestingly, R-loops are also commonly observed at CpG islands, where significant DSB accumulation was observed in cDKO BM cells by BLESS. We assessed the formation of R-loops and γH2AX on BM tissue sections. R-loop accumulation was observed between 1 and 2 days following 4 mg TAM injection and increased with time after cDKO. γH2AX staining overlapped with R-loop staining and showed a similar increase during the time course in BM (Figure 7A-C), small intestine (supplemental Figure 7A-C), spleen, and thymus (data not shown). Furthermore, RNase H treatment markedly reduced the intensity of the R-loop signal, validating the specificity of antibody for R-loop detection (supplemental Figure 7D). Altogether, these results suggest that R-loop accumulation is one of the early events when both Ssb1 and Ssb2 are disrupted, which accompanies DSB generated most likely because of conflict with replication.

Figure 7.

R-loop and DNA damage accumulation lead to BM failure in cDKO mice. (A) Representative image of immunostaining of R-loop (green), γH2AX (red), and nuclei (blue, DAPI staining) on BM sections on day 4 after 4 mg of TAM. Images were acquired at ×20 magnification (first and third panels) and zoomed in ×5 for indicated areas. (B-C) Ratio of BM cells with positive R-loop (B) and γH2AX (C) during the 4-day time course after cDKO. For each experiment, 4 sections from 4 individual mice were analyzed at 5 time points. Statistical analysis represents t test. (D) Proposed model of genomic instability in cDKO cells. cDKO induces R-loop, replication stress, and DSB accumulation, cytosolic ssDNA with consequent activation of IFN, p53 and DDR pathways, and apoptotic cell death, hence disruption of stem cell homeostasis. See also supplemental Figure 7. ***P < .001.

Discussion

SSB1 and SSB2 have crucial roles in the repair of extrinsic DNA damage in human cells.3-8 Our generation and phenotypic analysis of cDKO mice has unmasked the compensatory and essential functions of Ssb1/Ssb2 in maintaining tissue homeostasis, which was unexpected from analysis of single knockout mouse models.20,23 Here, we studied hematopoiesis to demonstrate the requirement for Ssb1 and Ssb2 in protecting stem and progenitor cells from endogenous DNA damage. Our study is the first to report acute BM failure and severe intestinal atrophy due to stem and progenitor cell death in Ssb1/Ssb2 cDKO mice. The observed phenotypes likely manifest because of the rapidly dividing nature of BM and small intestine; however, the effects of cDKO are likely to be relevant to other rapidly dividing cells in culture. Consistent with this, we observed that in vitro cultured Hoxb8-immortalized cDKO HSPCs corroborate and validate our in vivo findings in BM.

Functionally, cDKO triggers quiescent HSPCs to proliferate, followed by apoptotic cell loss, which ultimately results in hematopoietic failure. We observed that HSPCs have an intrinsic requirement for Ssb1/Ssb2, because their deletion resulted in a loss of hematopoiesis in BM transplant recipients. Mechanistically, we observed replication stress, DSBs and cytosolic ssDNA accumulation, intrinsic transcriptional activation of interferon, p53 and DNA damage pathways in cDKO HSPCs, followed by induction of significant cell death and BM failure. Moreover, in vitro cultured Hoxb8-immortalized HSC undergo significant cell death within 6 days of induction of cDKO. This phenotype can be rescued by supplementation with nucleosides or by knockdown of p53, suggesting that replication-stress-associated DNA damage and p53 induction are major effectors of cell death in cDKO cells. We propose that ssDNA generated from unrepaired DNA damage induces cell-intrinsic activation of the interferon pathway,44-46 which perturbs HSC quiescence, primes HSPCs for p53-mediated apoptotic cell death, and ultimately contributes to HSPC depletion (Figure 7D).29,48,54 These findings indicate that Ssb1 and Ssb2 coordinately protect organs from endogenous replication stress during normal physiology and are essential genome guardians for homeostasis of BM stem and progenitor cells.

The acute BM failure seen in adult cDKO mice was completely penetrant, in comparison with Ssb1 or Ssb2 single knockouts or knockouts of other DNA repair genes, including genes in the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway, which show much milder phenotypes and longer latencies that in some cases are evident only during aging or stress.55-58 FA is a polygenic human syndrome characterized by aberrant DNA repair and with stem cell defects, leading to BM failure.56,59,60 In murine models of FA, BM failure can only be induced by physiological activation of HSCs out of a quiescent state (eg, through the induction of type 1 interferon).48 Notably, in cDKO mice, BM failure occurred rapidly and with full penetrance in the absence of extrinsic genotoxic stressors. Ssb2 has been proposed as a HSC marker61,62; its expression is higher in more immature HSCs and downregulated with lineage maturation.63 This trend is distinct from other repair genes that show increased expression during lineage commitment and differentiation.63 However, the function of Ssb2 in BM can be well compensated for by Ssb1 when Ssb2 is abolished because Ssb2-null mice show no defect.23

The human SSB proteins are components of the integrator complex, which has recently been shown to play a broader role in transcription, including in promoter proximal pause release and elongation and in 3′-end processing and termination.13-17 Most of the target sites of the components of integrator complex including SSB1 and SSB2 maintain a constitutively open chromatin state that is favorable to R-loop formation.18 Defects in transcription initiation and termination can lead to accumulation of R-loops and consequent genomic instability as the exposed nontemplated ssDNA becomes more susceptible to DNA damage, which may restrict transcription and slow down or block replication forks. Blocked replication forks could further lead to fork stalling, collapse, and DSBs.64,65 In situ mapping of DSBs revealed that cDKO-induced specific DSBs are enriched in Ssb1 and Ssb2 binding sites,15 in CpG islands, and near transcription start sites of highly expressed genes; all of these regions are favorable to R-loop formation. Consistently, rapid R-loop accumulation was observed after induction of cDKO and progressively increased over time concomitant with γ-H2AX staining. This evidence supports potential roles of Ssb1 and Ssb2 in preventing accumulation of R-loop and associated DNA damage in concert with the integrator complex during transcription. However, it remains to be determined whether R-loops play a causative role in genomic instability and cell death observed in cDKO cells, because our attempts to rescue the phenotype by ribonuclease H overexpression led to nonspecific toxicity in WT and cDKO HSPCs.

In conclusion, this study has elucidated the novel roles of Ssb1 and Ssb2, which function as guardians of genome stability by resolving endogenous replication stress in HSPCs and later components of the blood hierarchy. The cDKO model exhibits rapid cell death of stem and progenitors and functional loss of BM and intestine, which resembles the changes seen in acute radiation toxicity. This warrants further studies into these 2 proteins, for their roles in mediating chemotherapy and radiation resistance by protecting the genome against the DNA damaging effects of cytotoxic cancer treatments. Alternatively, inducing DNA damage (eg, through interferon therapy) together with inhibition of SSB1/2 may synergize as an antineoplastic therapy. Importantly, accumulating evidence suggests that networks that coordinate normal stem cell self-renewal may lead to tumorigenesis upon overactivation or to premature aging once their functionality declines.66 As genomic instability is a major hallmark of actively self-renewing and proliferating cancer cells,67 further study on the function of SSB1 and SSB2 in cancer formation and progression will be of great interest to the field.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Mcguckin (University of Queensland) and Robert Ramsay and Jordane Malaterre (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre) for thoughtful discussions on the intestinal phenotype; David Curtis and Ross Dickins (Monash, Melbourne) for provision of plasmid constructs; and Axia Song, Emma Dishington, Stephen Miles (QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute), and Jian Gong (Central South University) for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (NHMRC1085367) (K.K.K. and S.W.L.); the National Institutes of Health (grants CA129537 and CA154320 [T.K.P.] from the National Cancer Institute and grants GM109768 [T.K.P.] and GM112131 [M.R., J.N., and N.D.] from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences); the Polish National Science Centre (grants 2011/02/A/NZ2/00014, 2014/15/B/NZ1/03357, and 2015/17/D/NZ2/03711) (K.G., M.S., A.B., and M.G.); the Foundation for Polish Science (grant TEAM) (K.G., M.S., and A.B.); and an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (K.K.K.). S.W.L. is an NHMRC Career Development Fellow, and T.V. is a Leukaemia Foundation PhD Scholar.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: W.S., T.V., S.W.L., and K.K.K. designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; W.S., T.V., D.B., A.B., R.K.P., G.M.B., J.J., J.L.H., A.L.B., M.G., M.S., N. Crosetto, K.G., and P.N. performed the experiments; and J.N., J.S., F.A.-E., A.M., N.D., N. Cloonan, O.J.B., J.F., J.R.S., C.R.W., T.K.P., M.R., and K.G. analyzed data. All authors read and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for D.B. is Cancer & Ageing Research Program, Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Translational Research Institute, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia.

The current affiliation for N.D. is Institute of Informatics, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland.

Correspondence: Wei Shi, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, 300 Herston Rd, Herston QLD 4006, Australia; e-mail: wei.shi@qimrberghofer.edu.au; Steven W. Lane, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, 300 Herston Rd, Herston QLD 4006, Australia; e-mail: steven.lane@qimrberghofer.edu.au; or Kum Kum Khanna, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, 300 Herston Rd, Herston QLD 4006, Australia; e-mail: kumkum.khanna@qimrberghofer.edu.au.

References

- 1.Richard DJ, Bolderson E, Khanna KK. Multiple human single-stranded DNA binding proteins function in genome maintenance: structural, biochemical and functional analysis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;44(2-3):98-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wold MS. Replication protein A: a heterotrimeric, single-stranded DNA-binding protein required for eukaryotic DNA metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:61-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richard DJ, Bolderson E, Cubeddu L, et al. . Single-stranded DNA-binding protein hSSB1 is critical for genomic stability. Nature. 2008;453(7195):677-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J, Gong Z, Ghosal G, Chen J. SOSS complexes participate in the maintenance of genomic stability. Mol Cell. 2009;35(3):384-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Bolderson E, Kumar R, et al. . HSSB1 and hSSB2 form similar multiprotein complexes that participate in DNA damage response. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(35):23525-23531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skaar JR, Richard DJ, Saraf A, et al. . INTS3 controls the hSSB1-mediated DNA damage response. J Cell Biol. 2009;187(1):25-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolderson E, Petermann E, Croft L, et al. . Human single-stranded DNA binding protein 1 (hSSB1/NABP2) is required for the stability and repair of stalled replication forks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(10):6326-6336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paquet N, Adams MN, Leong V, et al. . hSSB1 (NABP2/ OBFC2B) is required for the repair of 8-oxo-guanine by the hOGG1-mediated base excision repair pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(18):8817-8829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu P, Deng W, Lei M, Chang S. Single strand DNA binding proteins 1 and 2 protect newly replicated telomeres. Cell Res. 2013;23(5):705-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandita RK, Chow TT, Udayakumar D, et al. . Single-strand DNA-binding protein SSB1 facilitates TERT recruitment to telomeres and maintains telomere G-overhangs. Cancer Res. 2015;75(5):858-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Won D, Shin SY, Park CJ, et al. . OBFC2A/RARA: a novel fusion gene in variant acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(8):1432-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baillat D, Hakimi MA, Näär AM, Shilatifard A, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Integrator, a multiprotein mediator of small nuclear RNA processing, associates with the C-terminal repeat of RNA polymerase II. Cell. 2005;123(2):265-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stadelmayer B, Micas G, Gamot A, et al. . Integrator complex regulates NELF-mediated RNA polymerase II pause/release and processivity at coding genes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto J, Hagiwara Y, Chiba K, et al. . DSIF and NELF interact with Integrator to specify the correct post-transcriptional fate of snRNA genes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skaar JR, Ferris AL, Wu X, et al. . The Integrator complex controls the termination of transcription at diverse classes of gene targets. Cell Res. 2015;25(3):288-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardini A, Baillat D, Cesaroni M, et al. . Integrator regulates transcriptional initiation and pause release following activation. Mol Cell. 2014;56(1):128-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai F, Gardini A, Zhang A, Shiekhattar R. Integrator mediates the biogenesis of enhancer RNAs. Nature. 2015;525(7569):399-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baillat D, Wagner EJ. Integrator: surprisingly diverse functions in gene expression. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40(5):257-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groh M, Gromak N. Out of balance: R-loops in human disease. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(9):e1004630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi W, Bain AL, Schwer B, et al. . Essential developmental, genomic stability, and tumour suppressor functions of the mouse orthologue of hSSB1/NABP2. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(2):e1003298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldhahn N, Ferretti E, Robbiani DF, et al. . The hSSB1 orthologue Obfc2b is essential for skeletogenesis but dispensable for the DNA damage response in vivo. EMBO J. 2012;31(20):4045-4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bain AL, Shi W, Khanna KK. Mouse models uncap novel roles of SSBs. Cell Res. 2013;23(6):744-745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boucher D, Vu T, Bain AL, et al. . Ssb2/Nabp1 is dispensable for thymic maturation, male fertility, and DNA repair in mice. FASEB J. 2015;29(8):3326-3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruedigam C, Bagger FO, Heidel FH, et al. . Telomerase inhibition effectively targets mouse and human AML stem cells and delays relapse following chemotherapy. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(6):775-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salmanidis M, Brumatti G, Narayan N, et al. . Hoxb8 regulates expression of microRNAs to control cell death and differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(10):1370-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bester AC, Roniger M, Oren YS, et al. . Nucleotide deficiency promotes genomic instability in early stages of cancer development. Cell. 2011;145(3):435-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruiz S, Lopez-Contreras AJ, Gabut M, et al. . Limiting replication stress during somatic cell reprogramming reduces genomic instability in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickins RA, Hemann MT, Zilfou JT, et al. . Probing tumor phenotypes using stable and regulated synthetic microRNA precursors. Nat Genet. 2005;37(11):1289-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flach J, Bakker ST, Mohrin M, et al. . Replication stress is a potent driver of functional decline in ageing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;512(7513):198-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta A, Hunt CR, Hegde ML, et al. . MOF phosphorylation by ATM regulates 53BP1-mediated double-strand break repair pathway choice. Cell Reports. 2014;8(1):177-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandita RK, Sharma GG, Laszlo A, et al. . Mammalian Rad9 plays a role in telomere stability, S- and G2-phase-specific cell survival, and homologous recombinational repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(5):1850-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crosetto N, Mitra A, Silva MJ, et al. . Nucleotide-resolution DNA double-strand break mapping by next-generation sequencing. Nat Methods. 2013;10(4):361-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vooijs M, Jonkers J, Berns A. A highly efficient ligand-regulated Cre recombinase mouse line shows that LoxP recombination is position dependent. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(4):292-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghosh M, Aguila HL, Michaud J, et al. . Essential role of the RNA-binding protein HuR in progenitor cell survival in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(12):3530-3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macià i Garau M, Lucas Calduch A, López EC. Radiobiology of the acute radiation syndrome. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2011;16(4):123-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potten CS. Radiation, the ideal cytotoxic agent for studying the cell biology of tissues such as the small intestine. Radiat Res. 2004;161(2):123-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eaves CJ. Hematopoietic stem cells: concepts, definitions, and the new reality. Blood. 2015;125(17):2605-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun J, Ramos A, Chapman B, et al. . Clonal dynamics of native haematopoiesis. Nature. 2014;514(7522):322-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez Perdiguero E, Klapproth K, Schulz C, et al. . Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature. 2015;518(7540):547-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou T, Chen P, Gu J, et al. . Potential relationship between inadequate response to DNA damage and development of myelodysplastic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(1):966-989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perkins AC, Cory S. Conditional immortalization of mouse myelomonocytic, megakaryocytic and mast cell progenitors by the Hox-2.4 homeobox gene. EMBO J. 1993;12(10):3835-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pietras EM, Lakshminarasimhan R, Techner JM, et al. . Re-entry into quiescence protects hematopoietic stem cells from the killing effect of chronic exposure to type I interferons. J Exp Med. 2014;211(2):245-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kharas MG, Lengner CJ, Al-Shahrour F, et al. . Musashi-2 regulates normal hematopoiesis and promotes aggressive myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2010;16(8):903-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen YJ, Le Bert N, Chitre AA, et al. . Genome-derived cytosolic DNA mediates type I interferon-dependent rejection of B cell lymphoma cells. Cell Reports. 2015;11(3):460-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Q, Katlinskaya YV, Carbone CJ, et al. . DNA-damage-induced type I interferon promotes senescence and inhibits stem cell function. Cell Reports. 2015;11(5):785-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Härtlova A, Erttmann SF, Raffi FA, et al. . DNA damage primes the type I interferon system via the cytosolic DNA sensor STING to promote anti-microbial innate immunity. Immunity. 2015;42(2):332-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Essers MA, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, et al. . IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009;458(7240):904-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walter D, Lier A, Geiselhart A, et al. . Exit from dormancy provokes DNA-damage-induced attrition in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2015;520(7548):549-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitra A, Skrzypczak M, Ginalski K, Rowicka M. Strategies for achieving high sequencing accuracy for low diversity samples and avoiding sample bleeding using illumina platform. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0120520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Helmrich A, Ballarino M, Tora L. Collisions between replication and transcription complexes cause common fragile site instability at the longest human genes. Mol Cell. 2011;44(6):966-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fungtammasan A, Walsh E, Chiaromonte F, Eckert KA, Makova KD. A genome-wide analysis of common fragile sites: what features determine chromosomal instability in the human genome? Genome Res. 2012;22(6):993-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skourti-Stathaki K, Proudfoot NJ. A double-edged sword: R loops as threats to genome integrity and powerful regulators of gene expression. Genes Dev. 2014;28(13):1384-1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hartono SR, Korf IF, Chédin F. GC skew is a conserved property of unmethylated CpG island promoters across vertebrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(20):9729-9741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G, et al. . Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135(6):1118-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruzankina Y, Pinzon-Guzman C, Asare A, et al. . Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(1):113-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garaycoechea JI, Patel KJ. Why does the bone marrow fail in Fanconi anemia? Blood. 2014;123(1):26-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richardson C, Yan S, Vestal CG. Oxidative stress, bone marrow failure, and genome instability in hematopoietic stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(2):2366-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang S, Yajima H, Huynh H, et al. . Congenital bone marrow failure in DNA-PKcs mutant mice associated with deficiencies in DNA repair. J Cell Biol. 2011;193(2):295-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ceccaldi R, Parmar K, Mouly E, et al. . Bone marrow failure in Fanconi anemia is triggered by an exacerbated p53/p21 DNA damage response that impairs hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(1):36-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tulpule A, Lensch MW, Miller JD, et al. . Knockdown of Fanconi anemia genes in human embryonic stem cells reveals early developmental defects in the hematopoietic lineage. Blood. 2010;115(17):3453-3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Montrone C, Kokkaliaris KD, Loeffler D, et al. . HSC-explorer: a curated database for hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Venezia TA, Merchant AA, Ramos CA, et al. . Molecular signatures of proliferation and quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(10):e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cabezas-Wallscheid N, Klimmeck D, Hansson J, et al. . Identification of regulatory networks in HSCs and their immediate progeny via integrated proteome, transcriptome, and DNA methylome analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(4):507-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aguilera A, García-Muse T. R loops: from transcription byproducts to threats to genome stability. Mol Cell. 2012;46(2):115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skourti-Stathaki K, Kamieniarz-Gdula K, Proudfoot NJ. R-loops induce repressive chromatin marks over mammalian gene terminators. Nature. 2014;516(7531):436-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rossi DJ, Jamieson CH, Weissman IL. Stems cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell. 2008;132(4):681-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]