Abstract

Promoting child development and welfare delivers human rights and builds sustainable economies through investment in ‘cognitive capital’. This analysis looks at conditions that support optimal brain development in childhood and highlights how social protection promotes these conditions and strengthens the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Asia and the Pacific. Embracing child-sensitive social protection offers multiple benefits. The region has been a leader in global poverty reduction but the underlying pattern of economic growth exacerbates inequality and is increasingly unsustainable. The strategy of channelling low-skilled rural labour to industrial jobs left millions of children behind with limited opportunities for development. Building child-sensitive social protection and investing better in children's cognitive capacity could check these trends and trigger powerful long-term human capital development—enabling labour productivity to grow faster than populations age. While governments are investing more in social protection, the region's spending remains low by international comparison. Investment is particularly inadequate where it yields the highest returns: during the first 1000 days of life. Five steps are recommended for moving forward: (1) building cognitive capital by adjusting the region's development paradigms to reflect better the economic and social returns from investing in children; (2) understand and track better child poverty and vulnerability; (3) progressively build universal, child-sensitive systems that strengthen comprehensive interventions within life cycle frameworks; (4) mobilise national resources for early childhood investments and child-sensitive social protection; and (5) leverage the SDGs and other channels of national and international collaboration.

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

Social protection represents one of government's most effective interventions for tackling poverty and vulnerability in Asia and the Pacific.

What are the new findings?

Child-sensitive social protection, with its prenatal and early childhood investments, nurtures in children ‘cognitive capital’ that not only delivers human rights but also lays the foundation for inclusive social development and equitable economic growth. Governments can maximise long-term returns that address long-term demographic challenges and improve future living standards by substantially increasing child-centred social protection within a life cycle framework, and by building intersector linkages, particularly to health, education, child protection and livelihoods.

Recommendations for policy

Social protection complements a range of best practices by ensuring that all children have access to nutrition, care, learning and security.

Introduction

Policymakers in Asia and the Pacific face vital choices for the future economic growth and prosperity of their countries. With inequality rising, demographic dividends diminishing and middle-income traps threatening, the social and economic options have never been more daunting…or more promising. Asia's most successful countries over the next several decades will be those whose leaders recognise that tomorrow's social inclusion and equitable economic growth depends on their investments in today's children.

Investments in children, particularly in the earliest years, yield dividends that realise human rights and slay today's giants of inequality, deprivation and economic stagnation. They nurture virtuous cycles with immediate as well as long-term impacts on development. Scaling up these investments to reach each baby offers every child a chance to develop to his or her full potential; hence, it positions the whole nation better for participating in the new global economy. Financing child-sensitive social protection interventions promises particularly high returns in countries that embrace international collaboration for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), through reinforcing positive feedback loops between sustainable economic and social development.

This note investigates why integrated child-sensitive social protection provides a crucial building block for equity and human rights as well as for economic and social development. It highlights progress over the past decades and identifies gaps and issues in Asia and the Pacific that can be most productively addressed by taking advantage of evidence on brain development and the impact and effectiveness of social protection in promoting cognitive capital and socioeconomic development.

Cognitive capital represents the complete set of intellectual skills, primarily nurtured prenatally and in early childhood, that determines human capabilities. Hence, cognitive capital refers to cognitive skills, as well as non-cognitive, socioemotional and executive function skills that allow for creativity, flexibility and ability to work collaboratively. Cognitive capital drives the most rapidly growing sectors of the modern economy. It develops optimally in boys and girls who benefit from good nutrition, stimulation and a supportive and secure family and social environment.

Investing in cognitive capital requires a focus on early childhood development and social protection

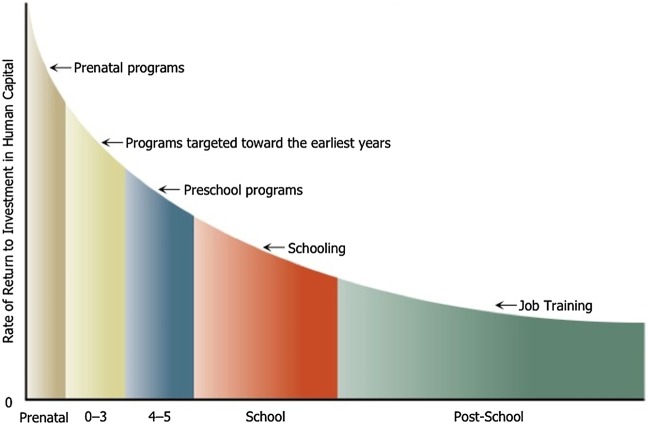

In recent years, a significant body of scientific evidence has emerged on brain development and what these findings mean for public policies.1 Studies highlight positive feedback loops between brain development and children's evolving cognitive, emotional and social capacities. As Nobel Laureate James Heckman demonstrates, the rates of return on investments in human capital decline with age (figure 1):2 a dollar spent during the prenatal and early childhood years gives on average between 7% and 10% greater yields than investments made at older ages.3

Figure 1.

Investment in Human Capital Brings the Highest Return in Early Age.

Unfortunately, feedback loops also work in the reverse direction. Brain research shows that ‘genes provide no more than an initial blueprint for building brain architecture and environmental influences determine how the neural circuitry actually gets wired’.4 Adverse conditions for development during fetal growth and the first 2 years of life can lead to suboptimal development and alterations to a child's brain that have implications for learning, behaviour and health across the lifespan (ref. 4, pp. 10–15). For example, significant adversity in childhood can alter the connectivity between the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, leading to potentially permanent changes in stress physiology, learning and executive functioning. Similarly, changes impairing infant motor development could alter exploratory behaviour and create further barriers to brain development and cognitive capacity.5

What does a young child's brain need from his or her environment—to grow to its potential? There is a vast amount of evidence on the importance of sufficient, healthy and nutritious food intake, especially during the first 1000 days of life, when the body gives strong priority to brain development. However, apart from getting the proper nutrients adequate for age, the body should also be able to keep them. Food safety, clean water and good sanitation are, therefore, also essential. Finally, the child's body should be able to use nutrients optimally for building the brain.6 Stimulation and feeling safe, loved and protected greatly help this process. Breastfeeding epitomises the holistic interaction between these three key dimensions of need—securing optimal nutrients, hygienic environments and intensive personal interaction.

Besides nutrients and proper health conditions, therefore, children need safe, stable and nurturing relationships as well as psychosocial stimulation for their brain development and evolving cognitive capacity. In a randomised controlled trial involving disadvantaged Jamaican children, those who received psychosocial stimulation and nutrition supplements up to the age of 2 years scored higher on intelligence quotient (IQ) tests by the age of 6 years than did a control group receiving only nutrition supplements. Those who received only stimulation did somewhat less well, but strikingly still better than the group treated only with nutrition supplements.7 Exposure to prolonged periods of stress, on the other hand, prevents the brain from fully benefiting from stimulating or enriching educational experiences. It also has the potential to impair the part of the brain that is responsible for self-regulatory skills and hence essential for success in school and adulthood.8 Toxic psychosocial stress—generated by physical and emotional abuse, chronic neglect and family violence—is increasingly considered highly disruptive for the brain architecture, the development of other organs and the ability to deal with stress.9 Similarly, social stigma undermines children's cognitive performance. In one experiment, low-caste Indian young boys' puzzle-solving ability dropped significantly as soon as their caste was publicly revealed, while initially they had been performing just as well as their higher caste peers.10

Violations of children's human rights to development entail significant social as well as economic costs for nations. Stunting in young age significantly increases the probability of chronic disease, low educational attainment, reduced income and decreased birth weight of offspring among adults.5 Stress and anxiety in infancy have cascading negative consequences for later achievements.8 A US National Bureau of Economic Research paper found that, keeping other factors constant, maltreatment in childhood doubles the probability of engaging in crime later in life.11

Adverse prenatal and early childhood environments hence lead to deficits in adult skills and abilities. This drives down productivity and increases social costs, adding to fiscal deficits that burden national economies, hampering long-term growth and development. World Bank research shows that adults who suffered prenatal and very early childhood malnutrition lose 12% of potential earnings due to lower labour productivity, costing India and China billions of dollars a year in foregone incomes.12 Multifaceted and evidence-based action can, however, ensure that children in adversity thrive.13

Key elements and results of social protection

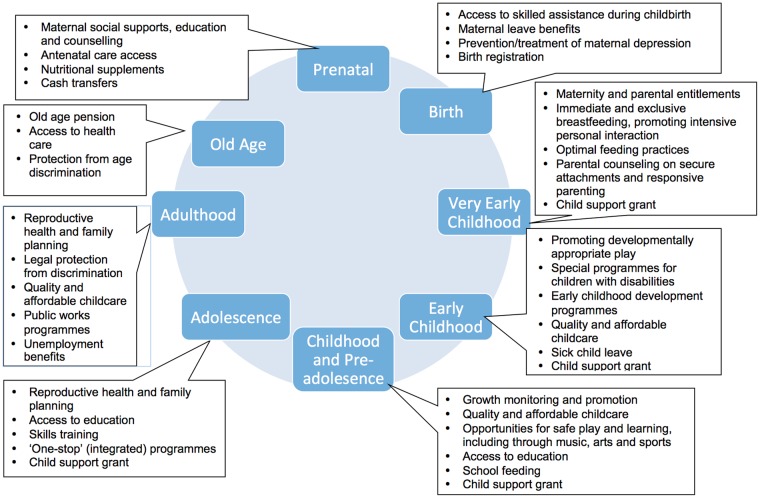

Social protection represents a far-reaching, rich set of policy instruments that tackle poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion throughout the life cycle. Child-sensitive social protection includes social programmes (social transfers, family support and social care services) as well as legislation.14 The latter may encompass social insurance, social assistance, employment and inheritance laws that establish entitlements and prevent discrimination by gender, age, race and ethnicity and, in some countries, also by migration status. Figure 215 lists a number of relevant programmes.

Figure 2.

Social protection instruments across the life cycle.

Box 1 cites global evidence on the effectiveness of social protection in 10 dimensions, including emerging evidence from the Asia and Pacific region. It testifies that social protection consistently strengthens human capital development, especially when benefits reach pregnant women and young children. Taken together, its instruments foster sustainable development and expand livelihoods and employment opportunities; address the work–childcare dichotomy; and enable households to make long-term investments in education, health and nutrition. They make economic growth more robust through enhanced labour productivity, social cohesion, increased demand and macroeconomic stability.16 These instruments and programmes are, therefore, highly suitable for efforts in Asia and the Pacific to sustain high growth rates while broadening progress along the 2016–2030 Sustainable Development Agenda.

Box 1. Evidence on impact of social protection and goals in the Sustainable Development Agenda.

1. Social protection tackles poverty and inequality (Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1, 10)

In Mexico, Progresa beneficiaries showed a poverty gap reduction of 30% after 2 years.17

In Latin America, breaking the region's history with high inequality is associated with growth of social protection programmes over the past 15 years.18

In Bangladesh, a longitudinal assessment of the impact of Building Resources Across Communities (BRAC)'s ultra-poor scheme from 2007 shows beneficiaries consistently improving their development results year after year after the programme ended.19 20

Within Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, higher government spending on family and social benefits is strongly associated with lower child poverty and deprivation rates.21

2. Social protection reduces hunger and strengthens food security (SDG 2)

In South Africa, early childhood receipt of child grants boosts long-term nutritional outcomes, with economic returns estimated between 60% and 130%.22

In Indonesia, a randomised control trial of the social cash transfer programme Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH) shows improved prenatal visits and immunisation indicators and reduced severe stunting.23

While the sizes of these impacts are small relative to those demonstrated in South Africa, results are consistent with the more limited investment and smaller benefit size.

3. Social protection improves maternal health and the foundations of cognitive development (SDG 2, 3)

Evaluation of the Philippines flagship Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) shows significant improvement in preventive healthcare among disadvantaged pregnant women and younger children and the reduction of malnutrition.24

In Mexico, the Oportunidades programme combined cash transfers and free health services with improvements in the supply of health services, leading to a 17% decline in rural infant mortality over a 3-year period.25

Maternal mortality was also reduced (by 11%), and both impacts were stronger in disadvantaged communities.26

Here, children aged 0–3 participating in the earlier Progresa programme were 39.5% less likely to be ill over the course of the 24 months that programme effects were measured.27

4. Social protection strengthens education outcomes (SDG 4)

Conditional and unconditional cash transfer programmes are increasing participation in education and securing progression to higher grades in a large number of countries.25 28

Rigorous quantitative evaluations of cash transfer programmes in Cambodia, Bangladesh and Pakistan showed strong and gendered impact.27 29

5. Social protection promotes gender equality and empowers women and girls (SDG 5)

Social protection programmes around the world show good capacity and many innovative solutions to overcome barriers and help the girl child and adult women to access good nutrition, health and education.30

In Pakistan, the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) delivered the money order to women on their doorsteps in recognition of their restricted mobility.30

Typically, the intended recipients of child grants and other cash transfers are mothers or women in the household, which has been found to boost development impacts and help power relationships within the family.31

6. Social protection strengthens resilience and households’ environmental management (SDG 6, 9, 13)

Cash-for-work programmes in Bangladesh targeting assistance to more than 1 million people now are aligned with the peak vulnerability period associated with annual floods. The public works build plinths to raised homes and gardens above the flood lines and provide income that increases and diversifies food consumption, leading to significant anthropometrically measured nutritional impacts for women and children.32

In Nepal as well as in the Philippines, emergency cash transfers and benefit top-up initiatives have proven quick and scalable interventions, also triggering longer term development impacts.33 34

7. Social protection strengthens social inclusion and cohesion, as well as prevents violence (SDG 10, 11, 16)

Social protection programmes have contributed positively to capacity for diverse groups within the society to work collaboratively and find common ground and solutions that promote comprehensive well-being among engaged parties, including in postconflict contexts.35

Nepal's labour unions negotiated social protection benefits as a necessary quid pro quo for labour market reforms, with a resulting win–win policy mix that would reinforce growth and social equity.35

8. Social protection fosters inclusive growth, decent work and more productive employment (SDG 8)

In Brazil, the Programme for the Eradication of Child Labour (PETI) reduced the probability of children working and their likelihood to be engaged in higher risk activities.36

Zambia's Child Grant Programme helps recipient households to increase agricultural inputs like seeds and labour and expand land used for agricultural production by 34%. It also enables families to diversify into non-agricultural business ventures, increasing these activities by 16%.37

Mauritius's social protection system enables the government to lead a vulnerable monocrop economy with high poverty rates onto a high growth export-driven path, which has produced extraordinarily high economic growth rates and some of the lowest poverty rates in the developing world.38

In India, the Maharashtra Employment Guarantee Scheme was a success in terms of stabilising household income, improving women's employment and generating through these effects significant impacts on child nutrition outcomes.39

9. Social protection stimulates local economies, macroeconomic reforms and resilience (SDG 12, 16, 17)

A comparative analysis of seven sub-Saharan countries finds that social cash programmes create significant boosts to the local economy: each dollar transferred to a poor, labour constrained household generating an additional 0.27–1.52 dollar income at the local level through economic spillover effects.40

The size of the social protection component of stimulus packages introduced in Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, China and Malaysia after 2008 ranged from 10% to 35%.41

Mexico and Indonesia have employed social protection programmes to compensate poor households for the costs of economic reforms, thus better enabling the growth that benefits rich and poor in the long run.42

10. Social protection strengthens policy coherence and development partnerships (SDG 17)

Social protection strengthens the effectiveness and credibility of governments, building and reinforcing good governance.43

During the recent global financial and economic crisis, many countries, including most large Asian economies, have introduced or upgraded social protection interventions to soften the worst effects of the crisis, effectively protecting the whole global economy.41

Social protection is also on Nepal's agenda to help build a more secure state, prevent a return to conflict and to provide a visible peace dividend.44

Importantly, this extensive evidence base confirms that social protection is effective in reducing poverty and the prevalence of malnutrition and life-threatening risks during fetal growth and early childhood. It can prevent the accumulation of disadvantage by connecting children and their carers better to health and education services. It is also effective in reducing stress, stigma and violence throughout childhood. Finally, there is also strong evidence that social protection strengthens individual, household and community resilience. When looking at the issue from the flip side, that is, why some programmes show less success, very similar lessons emerge (box 2).

Box 2. When social protection fails, knowledge on causality helps eliminate errors and increase programme effectiveness and efficiency.

While social protection's global success is undeniable, interventions sometimes fail to generate the expected developmental impact. Three main factors explain much of the weakness observed:

1. Programmes were inappropriately designed and/or ineffectively implemented;

2. Early childhood effects were not considered well; pregnant women as well as the youngest and/or most vulnerable children were not covered properly through a special effort;

3. Interventions were developed in ‘silo’, hence lacking integration into the social protection system and failing to build bridges to the health, education, child protection and livelihood sectors, foregoing much of the promised developmental impact.

Today, with hundreds of rigorous evaluations of social protection programmes around the world, policymakers can benefit from the lessons of global experience. Appropriately designed and effectively implemented programmes, embedded within comprehensive multisectoral frameworks, can tackle poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion while strengthening inclusive social development and equitable economic growth.

Progress, gaps and opportunities in Asia and the Pacific for human development

As discussed previously, poverty and inequality have a causal link to suboptimal and unequal child outcomes through material and psychosocial levers. The fact that extreme income poverty decreased significantly over the past decades in Asia and the Pacific as a result of rapid economic growth is therefore good news for children. While many Asian countries achieved good progress with the Millennium Development Agenda, and some countries indeed prioritised supporting nutrition and early learning, some very important gaps and issues for children and women remain and are summarised in the following highlights.

Poverty reduction has frequently been shallow, and there are indications—although no clear statistics—suggesting that children remain over-represented among the poor. Evidence from the World Development Indicators database implies that in East Asia the population living in moderate poverty shrank to a third of its 1990 size, with 454 million people living on less than 3.10 dollars a day at purchasing power parity, while it actually increased from 791 to 899 million people in South Asia. Simultaneously, income inequalities have increased significantly, even though in recent years in some countries they have started to stabilise.45 46

The data47 show that there is still a very significant deficit in child nutrition in many countries. Despite progress in strengthening food security, child nutrition outcomes have proven to be difficult to improve in many countries. In South Asia, 28% of babies have low birth weight, contributing to high levels of stunting by the age of 5 years. In East Asia, breastfeeding shows a serious deficit. Stunting rates here are mostly low due to the success of China, Vietnam, Thailand and some other countries in addressing chronic child malnutrition under the age of five. Nevertheless, some other countries show less progress, and it is yet unclear how the long-term cognitive and health impacts of rapid urbanisation affecting over 100 million children will unfold.

Disparities in access to services deny disadvantaged children and women a fair chance in life. Children born into the poorest 20% of households in the Philippines or Indonesia show significant differences in anthropometric outcomes and face a risk of dying before reaching age five, about three times higher than those born into the richest 20%. Annually, still over 1.4 million children do not live to their fifth birthday in the Asia and the Pacific; around 80 000 women lose their life to maternity-related complications. Women's access to antenatal care, skilled care at birth and essential newborn care is often marked by extreme disparity. For example, in Bangladesh and Pakistan, women from the richest households are, respectively, four and six times more likely to receive antenatal care than those from the poorest households. Across the region, around 17 million children (1 out of 20) do not participate in primary education; many of these children live with disabilities. Enrolment and/or attendance gaps in preprimary and secondary education hover around 30% in East Asia and 40–45% in South Asia and with rates still showing gender imbalances, most notably in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Gender disparity and violence against women and children remain a concern. Women in Asia and the Pacific are over-represented in the informal economy, with more than 8 out of 10 in what a United Nations Women study calls ‘vulnerable’ employment status. Consequently, exposure to health risks, chances of employment promotion or accessing social security benefits shows a clear gender dimension. Parental leaves, breastfeeding time and other social protection measures, which aim at reconciling the work–childcare dichotomy, address ‘time-poverty’, strengthen men's commitment to childcare or improve the power balance within the household and mitigate the chance of domestic violence, are missing or rarely available in Asia and the Pacific, even though in some countries legal guarantees exist.48

Finally, it is important to remember here that the region faces high exposure to weather-related risks, climate change, natural disasters as well as imbalances in the global economy.49 The effects of these shocks tend to hit the poor, disadvantaged and vulnerable populations much harder than others.

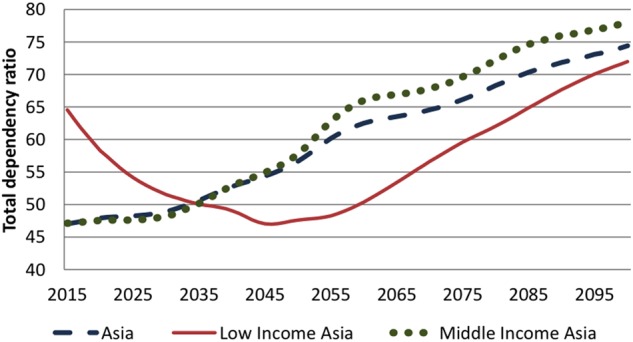

These gaps and issues would justify a stronger focus on expanding social protection to all. However, there are two further trends that make stronger social protection an economic imperative. Figure 350 displays projected dependency ratios, a measure showing the number of people not in working age to the population in working age. Social protection, with its powerful long-term effects on human capital development, counters this demographic trap by better enabling labour productivity to grow faster than the population ages. This is particularly important for low-income Asian countries that are still reaping the benefits of demographic dividend. (Demographic dividend refers to the freeing up of resources for a country's economic development due to a working-age population that is temporarily growing faster than the population depending on it, usually due to falling fertility rates at the initial stage of transition from an agrarian to an industrial economy.) Given that this period will last no longer than perhaps another several decades, investing now in children builds a long-term human capital stock that can compensate for its ceasing in the future. For the middle-income Asian countries facing rising dependency ratios already, investing in cognitive capital represents the highest-return development opportunity.51

Figure 3.

Total projected dependency ratios in Asia 2015 to 2100.

Second, while public investment in social protection has started to accelerate in recent years, spending is still very low in international comparison, especially when it comes to child and family-oriented expenditures. International Labour Organization (ILO) data show that spending on children amounts to a meagre 0.2% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in Asia Pacific,52 which is one of the lowest among the main global regions, and about 10 times less in relative terms than in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) economies with which the region intends to compete in global markets over the longer term.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

In the second half of the past century, East Asian economies channelled unskilled labour into a rapidly expanding industrial base, sustaining for decades some of the highest economic growth rates the world has ever seen. Today, however, the most prominent source of economic growth lies in cognitive capital. For example, a college kid types at a keyboard and births a company that grows to a market capitalisation exceeding $100 billion. Cognitive capital cannot be mined or traded but rather must be carefully cultivated by the most forward-looking of policies. Box 3 shows a five-step agenda to embrace these policies, address headwinds and build a more virtuous, sustainable cycle of social and economic development—reconciling two major development paradigms: child rights and economic policy perspectives.

Box 3. A five-step agenda for maximising investments in child development.

1. Focus on building the cognitive capital of nations. Adjust the prevailing development paradigm to reflect better on the economic and social returns from investing in children, in particular during the first 1000 days of life. Consider equity-seeking, child-sensitive and integrated social protection, a crucial building block for sustained results.

2. Understand better child poverty and track vulnerability to hazards and exclusion. Create unified registers for social programmes and monitor the inclusion of children in services and supports in a more integrated and outcomes-centred fashion than has been the case so far. Collect and analyse household survey data regularly to understand the causality of inadequate child results that programmes need to address.

3. Build universal, child-sensitive social protection. Plan comprehensively, addressing exclusion and current programme fragmentation with a forward-looking, progressive perspective. Make programme evaluation and adjustment a regular part of the planning and resourcing process across the system.

4. Prioritise domestic resource mobilisation for early childhood investments and child-sensitive social protection. Build political support for financing investment in children's cognitive capital, making the case on economic efficiency as well as human rights grounds. Identify which items in the public budget make a difference and deliver results for children. Highlight that investment is needed on a significantly larger scale than what exists today.

5. Leverage the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), existing institutions and fora of national and international collaboration. Benefit from the experience of other countries in building integrated, child-sensitive social protection. Use in full the existing channels of South–South collaboration. Involve the private sector, national institutions and external donors as well as practitioners and children themselves—when and where this is useful and meaningful.

At this point in the 21st century, policy initiatives have already harvested the low-hanging fruit that has nourished the region's rise. Future progress depends on policies that tackle more complex challenges such as initiatives that build bridges across sectors and generate developmental synergies. National and geographical contexts vary significantly but human brain and child development follow a universal pattern, sending clear signals for timely and adequate support. What adults—mothers, fathers, carers, teachers, community and national leaders—need to do is listen, understand and respond well to these signals. When they do—especially at scale across the nearly four billion people strong Asia and Pacific region—the individual miracle of child development becomes a social and economic miracle with global ramifications. Child-sensitive social protection offers well-tried instruments, exciting innovations and sensible approaches to counter the impact of adverse conditions; there is no good reason why any country should pass on the chance to use them better.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: GF and DF drafted the first version, using extensively an unpublished manuscript by MS on the subject. MS, GF and DF all edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was funded from the resources of UNICEF.

Disclaimer: This paper is based on a longer thematic report presented on November 7th and 8th, 2016 at the UNICEF High Level Meeting on South-South Cooperation for Child Rights in Asia and the Pacific. The opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of UNICEF or any other agency.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Huebner G, Boothby N, Aber JL et al. . Beyond survival: the case for investing in young children globally. Discussion paper. National Academy of Medicine, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Heckman curve. http://heckmanequation.org/content/resource/heckman-curve.

- 3.Carneiro PM, Heckman JJ.. Human Capital Policy. IZA Discussion Paper No. 821 2003. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=434544

- 4.Shonkoff J. Building a foundation for prosperity on the science of early childhood development. Pathways winter edition. Stanford: Stanford Center of Poverty and Inequality, 2011:12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C et al. . Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008;371:340–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNICEF. Building better brains: new frontiers in early childhood development. 2014. http://www.unicef.cn/en/uploadfile/2015/0319/20150319103627793.pdf

- 7.Walker SP, Chang SM, Younger N et al. . The effect of psychosocial stimulation on cognition and behavior at 6 years in a cohort of term, low-birthweight Jamaican children. J Dev Med Child Neurol 2009;52:148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Bank. Mind, society and behavior. 2015 World Development Report. Washington DC: The World Bank, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Am Acad Psychiatrics 2012;129:232–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoff K, Panday P. Discrimination, social identity, and durable inequalities. Am Econ Rev 2006;96:206–12. 10.1257/000282806777212611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currie J, Tekin E. Does child abuse cause crime? NBER Working Paper No. 12171 2006.

- 12.World Bank. Repositioning nutrition as central to development – a strategy for large-scale action. Washington DC: World Bank; 2006:26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boothby N, Robert LB, Goldman P et al. . Coordinated and evidence-based policy and practice for protecting children outside of family care. Int J 2012;36:743–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department for International Development, United Kingdom (DFID UK), HelpAge International, Hope & Homes for Children, Institute of Development Studies, International Labour Organization, Overseas Development Institute, Save the Children UK, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Bank. Joint statement on advancing child-sensitive social protection. UNICEF: New York, 2009. http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/CSSP_joint_statement_10.16.09.pdf.

- 15.Developed by authors based on Samson M. Cognitive Capital - Investing in children to generate sustainable growth. Background paper for the Third High Level Meeting on Cooperation and Child Rights in the East Asia and Pacific Region 2016.

- 16.United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP). Time for equality: the role of social protection in reducing inequality in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok: UNESCAP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanlon J, Barrientos A, Hulme D. Just give money to the poor—the development revolution from the Global South. Boulder: Kumarian Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Bank. A break with history: fifteen years of inequality reduction in Latin America. Washington DC: World Bank, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das N, Misha F. Addressing extreme poverty in a sustainable manner: evidence from CFPR programme. CFPR Working paper No. 19 Dhaka: BRAC Research and Evaluation Division, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The World Bank. Bangladesh's Chars Livelihoods Programme (CLP). Washington DC: The World Bank, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNICEF. Child poverty in perspective: an overview of child well-being in rich countries. Innocenti Report Card 7 Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aguëro M, Carter M, Wooland I. The impact of unconditional cash transfers on nutrition: the South African Child Support Grant. Working Paper Series 06/08 Cape Town: SALDRU, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satriawan E.2016. Evaluating Longer-term Impact of Indonesia's CCT Program: Evidence from a Randomised Control Trial, presented at the JPAL SEA Conference on Social Protection, Jakarta. http://ekonomi.lipi.go.id/sites/default/files/evaluating_longer_term_impact_of_cct.pdf.

- 24.Frufonga RF. The Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) in Iloilo, Philippines: an evaluation. Asia Pac J Multidisciplinary Res 2015;3:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asian Development Bank. Conditional cash transfer programs: an effective tool for poverty alleviation? Manila: ADB, 2008:6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gertler P. Do conditional cash transfers improve child health? Evidence from PROGRESA's Control Randomized Experiment. Am Econ Rev 2004;94:336–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3592906339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asian Development Bank. Conditional cash transfer programs: an effective tool for poverty alleviation? Manila: ADB, 2008:6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.DSD, SASSA & UNICEF. The South African child support grant impact assessment: evidence from a survey of children, adolescents, and their households. Pretoria: UNICEF South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filmer D and Norbert Schady (2008) Getting Girls into School: Evidence from a Scholarship Program in Cambodia. See pp. 581–617 in “Economic development and cultural change”. Marcel Fafchamps, editor; The University of Chicago, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmes R, Jones N. Rethinking social protection using a gender lens. Working Paper 320 London: Overseas Development Institute, 2010:17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fajth G, Vinay C. Conditional cash transfers: a global perspective. MDG Insights. New York: UNDG, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mascie-Taylor CG, Marks MK, Goto R et al. . Impact of a cash-for-work programme on food consumption and nutrition among women and children facing food insecurity in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:854–60. 10.2471/BLT.10.080994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.UNICEF Nepal. Cash transfers as an emergency response and a catalyst to enhance the social protection system in Nepal. Kathmandu: UNICEF Nepal, 2016. http://unicef.org.np/media-centre/reports-and-publications/2015/09/30/the-road-to-recovery-cash-transfers-as-an-emergency-response-and-a-catalyst-to-enhance-the-social-protection-system-in-nepal [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNICEF Philippines. One Year After Typhoon Haiyan, Philippines. - Progress Report. 2014. Manila: UNICEF Philippines, 2014. http://www.unicef.org/appeals/files/UNICEF_Philippines_Typhoon_Haiyan_1_Year_Progress_Report_-_Dec2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.GIZ. Social protection and its contribution to social cohesion and state-building. Bonn: Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, 2012:11. [Google Scholar]

- 36.UNICEF. Child labour and UNICEF in action: children at the centre. New York: UNICEF, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Institutes for Research (AIR). Zambia's Child Grant Program: 24-month impact report. Washington DC: AIR, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy D, Subramanian A. Who can explain the Mauritian Miracle: Meade, Romer, Sachs, or Rodrik? Working Paper No. 01/116 Washington DC: International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2001. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2001/wp01116.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dandekar K. Employment guarantee scheme—an employment opportunity for women. Pune: Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thome K, Taylor JE, Filipski M et al. . A comparative analysis of seven sub-Saharan countries. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.UNICEF. Social protection: accelerating the MDGs with equity. Social and economic policy working briefs. UNICEF, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samson M. Cognitive Capital – Investing in children to generate sustainable growth. Background paper for the Third High Level Meeting on Cooperation and Child Rights in the East Asia and Pacific Region, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathers N, Slater R. Social protection and growth. London: Overseas Development Institute, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.UNICEF. Integrated social protection systems—enhancing equity for children. Social protection strategic framework. New York: UNICEF, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45.United Nations Economic and Social Committee for Asia and the Pacific. Time for Equality. UNESCAP: Bangkok, 2015:16–31. http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/SDD%20Time%20for%20Equality%20report_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balakrishnan R, Steinberg S, Syed M. The Elusive Quest for Inclusive Growth: Growth, Poverty, and Inequality. Working Paper 13/152. Washington DC: International Monetary Fund, 2013:4–7. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp13152.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 47.The source of the data quoted in this and following paragraph is derived from UNICEF. State of the World's Children 2016: A fair chance for every child. New York: UNICEF, 2016. http://www.unicef.org/publications/index_91711.html [Google Scholar]

- 48.International Labour Organization. Social protection for maternity: key policy trends and statistics. Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP). Disasters in Asia and the Pacific: 2014 year in review. Bangkok: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Authors’ calculation based on United Nations. World population prospects: the 2015 revision. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/events/other/10/index.shtml

- 51.The World Bank and International Monitory Fund (IMF). Development goals in an era of demographic change. Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016 2016:14–19.

- 52.International Labour Office. Social protection for children: key policy trends and statistics. Social Protection Policy Papers No. 14 Geneva: International Labour Office, 2015. [Google Scholar]