Abstract

Background

Exfoliative cheilitis is a condition of unknown etiology characterized by hyperkeratosis and scaling of vermilion epithelium with cyclic desquamation. It remains largely refractory to treatment, including corticosteroid therapy, antibiotics, antifungals, and immunosuppressants.

Objective

We sought to evaluate the safety and efficacy of excimer laser therapy and narrowband ultraviolet B therapy in female patients with refractory exfoliative cheilitis.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of two female patients who had been treated unsuccessfully for exfoliative cheilitis. We implemented excimer laser therapy, followed by hand-held narrowband UVB treatments for maintenance therapy, and followed them for clinical improvement and adverse effects.

Results

Both patients experienced significant clinical improvement with minimal adverse effects with excimer laser therapy 600-700 mJ/cm2 twice weekly for several months. The most common adverse effects were bleeding and burning, which occurred at higher doses. The hand-held narrowband UVB unit was also an effective maintenance tool.

Limitations

Limitations include small sample size and lack of standardization of starting dose and dose increments.

Conclusion

Excimer laser therapy is a well-tolerated and effective treatment for refractory exfoliative cheilitis with twice weekly laser treatments of up to 700 mJ/cm2. Transitioning to the hand-held narrowband UVB device was also an effective maintenance strategy.

Introduction

Exfoliative cheilitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology characterized by scaling, hyperkeratosis, and crusting due to desquamation of the vermilion epithelium (Daley and Gupta, 1995, Rogers and Bekic, 1997, Thomas et al., 1983). First in 1983 and again in 1998, exfoliative cheilitis was defined as a cyclic desquamation of the lips without evidence of factitial sources of irritation such as lip licking or biting, infection, or allergens as the primary etiology of the desquamation (Taniguchi and Kono, 1998, Thomas et al., 1983). Early literature suggested a female predisposition for the condition, particularly when exfoliative and factitious cheilitis were used interchangeably and when exfoliative cheilitis was found to be associated with underlying psychiatric disorders (Crotty and Dicken, 1981, Daley and Gupta, 1995, Taniguchi and Kono, 1998, Thomas et al., 1983). A recent retrospective study found a 2:1 female–male ratio in exfoliative cheilitis cases diagnosed from 2000 to 2010 (Almazrooa et al., 2013). In any population, the condition is generally refractory to treatment. We sought to evaluate the safety and efficacy of excimer laser therapy and a hand-held ultraviolet B (UVB) device for exfoliative cheilitis.

Methods

Two female patients with refractory exfoliative cheilitis were identified. The first patient is a 28-year-old female with a history of mild atopic dermatitis as a child who presented with a 2-year history of dry, cracking, and peeling lips. Her condition was so severe that she was placed on disability due to pain and difficulty eating and speaking. Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative. She had minimal response to topical corticosteroids, topical antibiotics, and topical and oral antifungals in the past (Table 1). Topical desoximetasone, oral mycophenolate mofetil, and topical calcipotriene 0.005% cream were tried in succession, but all had to be discontinued due to irritation and/or poor response. She tolerated a 9-day prednisone pulse tapered from 60 mg daily and tretinoin 0.025% cream with no adverse effects and moderate improvement. Throughout these treatments, she also concurrently used over-the-counter topical products (Table 1). Initial physical exam revealed dry mouth and scaling on lips with minimal erythema. Laboratory blood tests revealed a positive antinuclear antibody with a speckled pattern and low titer (1:80) and an elevated rheumatoid factor. Histologic examination showed subacute spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils. Patch testing revealed 1-2 + reactions to fragrance mix, cinnamic alcohol, amyl cinnamyl alcohol, and carvone, and trace reaction to shellac and triethanolamine. Patient was placed on a low-fragrance diet, and both she and her significant other exclusively used products that did not contain the allergens to which she was allergic. Her condition did not respond to allergen avoidance.

Table 1.

Patient 1: Previous Treatments.

| Treatment Category | Medications Previously Used |

|---|---|

| Topical corticosteroids | Betamethasone |

| Clobetasol | |

| Desoximetasone | |

| Topical antibiotics | Metronidazole gel |

| Topical antifungals | Name unknown |

| Topical retinoids | Tretinoin |

| Topical vitamin D analogs | Calcipotriene |

| Systemic antifungals | Name unknown |

| Systemic steroids | Dexamethasone |

| Prednisone | |

| Immunomodulators | Mycophenolate mofetil |

| Over-the-counter products | Olive oil |

| Safflower oil | |

| Vaseline |

The second patient is a 39-year-old female who presented with cheilitis for 15 years with frequent peeling and minute vesiculation limited to the transitional zone of the lip. Initially, the patient described frequently licking and biting her lips, but after stopping this habit, the peeling and flaking persisted. She had a history of asthma as a child, negative airborne allergy and food allergy testing, and a negative North American series patch test. Her only oral medication was omeprazole. In the past, she was treated in the United States, Europe, and Asia by multiple dermatologists. She had used systemic and topical corticosteroids, systemic and topical antibiotics, topical antifungals, multiple vitamin supplements, and various miscellaneous topicals without significant improvement (Table 2). Initial physical exam revealed scale on bilateral lips with minimal inflammation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation. Her lips had been biopsied several times, and the most recent biopsy from 2007 revealed spongiotic dermatitis.

Table 2.

Patient 2: Previous Treatments.

| Treatment Category | Medications Previously Used |

|---|---|

| Topical corticosteroids | Betamethasone |

| Clobetasol | |

| Desonide | |

| Dexamethasone | |

| Flumethasone | |

| Fluticasone | |

| Hydrocortisone | |

| Topical antibiotics | Ciprofloxacin |

| Gentamicin | |

| Topical antifungals | Tinidazole |

| Systemic antibiotics/antiparasitics | Cefprozil |

| Ciprofloxacin | |

| Mebendazole | |

| Tetracycline | |

| Systemic steroids | Prednisone |

| Miscellaneous topicals | Fusidic acid |

| Salicylic acid | |

| Vitamin supplements | Calcium pantothenate |

| Folic acid | |

| Nicotinamide | |

| Vitamins B1, B2, B6, B12 | |

| Vitamin C |

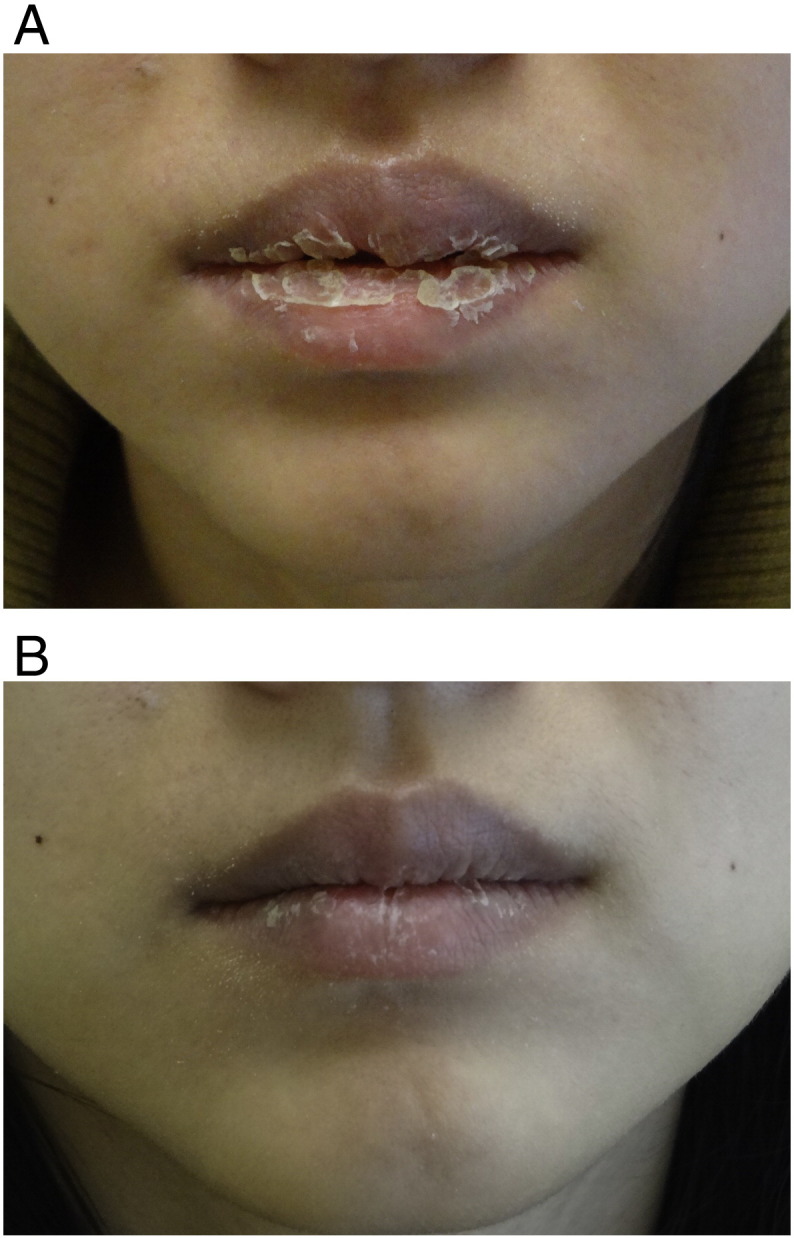

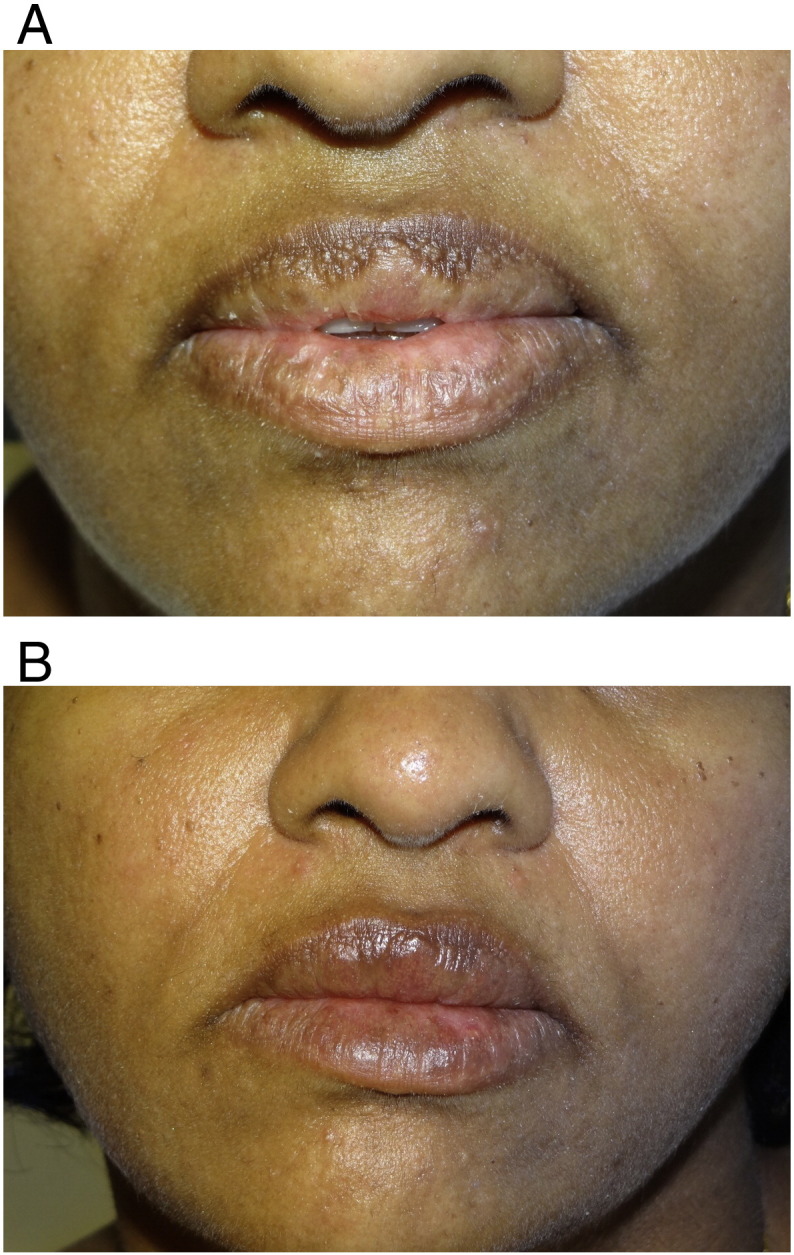

All topical medications were stopped, and patients began excimer laser therapy twice weekly. The first patient started at a dose of 400 mJ/cm2, increasing by 5 to 10% per treatment up to a maximum of 944 mJ/cm2. The second patient started at 300 mJ/cm2, increasing in 5 to 20% increments up to 724 mJ/cm2. Photographs of patients’ lips were taken before initiating laser treatment and at various points throughout treatment to monitor progress (Figs. 1A-B and 2A-B).

Fig. 1.

A, Exfoliative cheilitis. Patient 1 before beginning excimer laser therapy, with thick scaling and hyperkeratosis. B, Exfoliative cheilitis. Patient 1 showing significant improvement in scaling and dryness after completing 8 months of excimer therapy.

Fig. 2.

A, Exfoliative cheilitis. Patient 2 before beginning excimer therapy, demonstrating initial scaling and hypopigmentation. B, Exfoliative cheilitis. Patient 2 after 3 months of excimer laser therapy and 6 months of home narrowband UVB therapy, with minimal scaling and significant improvement of hypopigmentation.

Results

Clinical improvement of scaling and discoloration was noted within five weeks of beginning excimer laser therapy at 300 to 400 mJ/cm2. The first patient began excimer laser therapy twice weekly in December 2011 at a dose of 400 mJ/cm2, and started to see improvement after the third treatment at 462 mJ/cm2. Dose was increased by 5 to 10% per treatment, which she tolerated well up to a dose of 600 mJ/cm2, resulting in significant improvement. She experienced some burning and blistering at levels from 642 mJ/cm2 up to a peak dose of 944 mJ/cm2, and continued to have some blistering and bleeding when her dose was reduced to 610 mJ/cm2. She was further decreased to a maintenance dose of 510 mJ/cm2 with continuing clinical improvement and fewer side effects, reserving increases up to 530 mJ/cm2 for specific sites where the patient had thicker, intact skin during her desquamation cycle. Patient continued to have excellent clinical results, completing 52 total treatments with a nearly complete clinical response. She was provided a hand-held narrowband UVB unit to use at home starting August 2012 for maintenance. She continues to use this periodically, approximately every 3 to 4 months, for approximately 1-to-3-week intervals when the condition recurs, but reports that crusts remain thinner and are no longer painful since completing excimer laser therapy. The condition no longer impacts her activities of daily living. Lip peeling remained mild at 23-month follow-up from discontinuation of the excimer laser therapy.

The second patient began excimer laser therapy twice weekly in October 2012, starting at 300 mJ/cm2 and increasing by 5 to 20% increments to 600 to 700 mJ/cm2. She experienced mild swelling beginning at 470 mJ/cm2. Improvement of the scaling and discoloration was noted after 10 treatments, at 690 mJ/cm2. She reported some blistering, burning, and pruritus at 690 to 724 mJ/cm2. Peak dose was 724 mJ/cm2. She was simultaneously applying Vaseline and desonide 0.05% ointment to the affected areas twice daily to alleviate pruritus. In January 2013, she was transitioned to a hand-held narrowband UVB unit after experiencing a partial clinical response with 15 treatments. She began at 200 mJ/cm2 and increased by 10 mJ/cm2 increments up to three times/week up to a maximum of 700 mJ/cm2. Her cheilitis was 60% improved by April 2013. She reached a new maximum of 750 mJ/cm2, with a therapeutic range of 500 to 750 mJ/cm2. The patient experienced an 80% improvement by June 2013, after completing 3 months of excimer laser therapy and 6 months of home therapy. She felt overall the excimer laser therapy was the most effective of all the treatments she had tried and had stayed in remission at 18-month follow-up from discontinuation of the narrowband UVB therapy at home.

Both patients experienced significant resolution of scaling, crusts, skin thickness, and lip discomfort at doses of up to 600 mJ/cm2. At higher doses ranging from 610 to 944 mJ/cm2, patients experienced the adverse effects of blistering, burning, and bleeding. Doses up to 600 mJ/cm2 were better tolerated when patients had thicker, intact skin during their desquamation cycle.

Discussion

Exfoliative cheilitis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Patients will describe a cyclic desquamation of the lips despite minimizing factitial sources of irritation, such as lip licking or biting. It is important to rule out sources of allergic or irritant dermatitis, bacterial or candidal infection, and cheilitis glandularis through biopsy, culture, and patch testing (Crotty and Dicken, 1981, Reade and Sim, 1986, Reichart et al., 1997, Taniguchi and Kono, 1998, Thomas et al., 1983). Despite positive patch testing, avoidance does not result in remission in this population, and they classically fail trials of topical steroids and oral antifungal and antibiotic therapy (Crotty and Dicken, 1981, Daley and Gupta, 1995, Taniguchi and Kono, 1998).

Many different therapies have been attempted to treat exfoliative cheilitis. Among these are topical and systemic corticosteroids, antifungals, immunosuppressants, cryotherapy, and radiation therapy, as well as vitamins, petrolatum gels, mineral oils, and moisturizers, all which have not been curative (Crotty and Dicken, 1981, Connolly and Kennedy, 2004, Daley and Gupta, 1995, Leyland and Field, 2004, Mani and Shareef, 2007, Reade and Sim, 1986, Reichart et al., 1997, Taniguchi and Kono, 1998, Thomas et al., 1983). Individual case reports have supported the use of antidepressants (Crotty and Dicken, 1981, Leyland and Field, 2004, Mani and Shareef, 2007, Taniguchi and Kono, 1998), tacrolimus (Connolly and Kennedy, 2004), and Calendula officinalis ointment 10% (Roveroni-Favaretto et al., 2009).

Excimer laser is a form of light therapy that delivers a very specific, 308-nm wavelength of monochromic ultraviolet B in high-intensity, short impulses. Its main advantage is its precision, as it directly penetrates affected skin without affecting surrounding healthy skin, and it may also require fewer treatments than narrowband UVB therapy (Mudigonda et al., 2012). It is most commonly used for chronic, recalcitrant conditions such as psoriasis, vitiligo, dermatitis, and mycosis fungoides (Mudigonda et al., 2012). Excimer laser therapy is increasingly used in psoriasis due to its ability to target chronic exfoliative processes. Studies have suggested that the mechanism of action of the laser is to cause T-cell depletion by affecting key mediators of apoptosis and decreasing the rate of proliferation of keratinocytes (Bianchi et al., 2003). This, in turn, results in decreased inflammation and desquamation from a clinical standpoint.

In this sense, exfoliative cheilitis may respond to excimer laser by a similar mechanism as in psoriasis, as it involves chronic desquamation of the lips. Our two patients presented with severe scaling and hyperkeratosis in a desquamative cycle that was resistant to standard anti-infectious and anti-inflammatory therapy. The practitioner can consider the excimer laser as a novel therapy for exfoliative cheilitis, which is effective because it addresses the underlying cyclic processes of scaling and desquamation. It can result in significant clinical improvement by decreasing the rate of turnover the skin, perhaps by the same basic mechanisms of action affecting T-cells and apoptosis in psoriasis.

In our experience, exfoliative cheilitis that is refractory to treatment may benefit from excimer laser therapy. Therapy twice weekly can deliver results within 5 weeks, with progressive improvement seen after several months. Based on these two cases, initial doses of 300 to 400mJ/cm2 can be incrementally increased to a maximum of 700 mJ/cm2, based on patient response and adverse effects such as blistering, burning, and bleeding. Dosage may have to be adjusted at each visit based on how much skin is present at the time of the laser treatment (i.e., what point the patient is in during their desquamative cycle). Excimer laser therapy has the potential to produce clinically significant results in patients with recalcitrant exfoliative cheilitis.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Almazrooa S.A., Woo S.B., Mawardi H., Treister N. Characterization and management of exfoliative cheilitis: a single-center experience. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116(6):e485–e489. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi B., Campolmi P., Mavilia L., Danesi A., Rossi R., Cappugi P. Monochromatic excimer light (308 nm): an immunohistochemical study of cutaneous T cells and apoptosis-related molecules in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17(4):408–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly M., Kennedy C. Exfoliative cheilitis successfully treated with topical tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(1):241–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty C.P., Dicken C.H. Factitious lip crusting. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117(6):338–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley T.D., Gupta A.K. Exfoliative cheilitis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24(4):177–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyland L., Field E.A. Case report: exfoliative cheilitis managed with antidepressant medication. Dent Update. 2004;31(9):524–526. doi: 10.12968/denu.2004.31.9.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani S.A., Shareef B.T. Exfoliative cheilitis: report of a case. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73(7):629–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudigonda T., Dabade T.S., Feldman S.R. A review of targeted ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(4):664–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reade P.C., Sim R. Exfoliative cheilitis–a factitious disorder? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;15(3):313–317. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(86)80091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichart P.A., Weigel D., Schmidt-Westhausen A., Pohle H.D. Exfoliative cheilitis (EC) in AIDS: association with Candida infection. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26(6):290–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R.S., Bekic M. Diseases of the lips. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16(4):320–336. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(97)80025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roveroni-Favaretto L.H., Lodi K.B., Almeida J.D. Topical Calendula officinalis L. successfully treated exfoliative cheilitis: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9077. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi S., Kono T. Exfoliative cheilitis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1998;196(2):253–255. doi: 10.1159/000017886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J.R., III, Greene S.L., Dicken C.H. Factitious cheilitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:368–372. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]