Abstract

Background

Disseminated Histoplasmosis (DH) is a rare manifestation of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) in European countries. Naso-maxillar osteolysis due to Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum (Hcc) is unusual in endemic countries and has never been reported in European countries. Differential diagnoses such as malignant tumors, cocaine use, granulomatosis, vasculitis and infections are more frequently observed and could delay and/or bias the final diagnosis.

Case presentation

We report the case of an immunocompromised patient infected by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) with naso-maxillar histoplasmosis in a non-endemic country. Our aim is to describe the clinical presentation, the diagnostic and therapeutic issues. A 53-year-old woman, originated from Haiti, was admitted in 2016 for nasal deformation with alteration of general condition evolving for at least 6 months. HIV infection was diagnosed in 2006 and classified at AIDS stage in 2008 due to cytomegalovirus infection associated with pulmonary histoplasmosis. At admission, CD4 cell count was 9/mm3. Surgical biopsies were performed and ruled out differential or associated diagnoses. Mycological cultures identified Hcc and Blood Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for Hcc was positive. The patient was given daily Amphothericin B liposomal infusion during 1 month. Hcc PCR became negative in the blood under treatment, and then oral switch by itraconazole was introduced. Antiretroviral treatment was reintroduced after a 3-week histoplasmosis treatment. Normalization of naso-maxillar mucosa enabled a palatal prosthesis.

Conclusion

Naso-maxillar histoplasmosis is extremely rare; this is the first case ever reported in a non-endemic country. Differential diagnoses must be ruled out by conducting microbiologic tools and histological examinations on surgical biopsies. Early antifungal treatment should be initiated in order to prevent DH severe outcomes.

Keywords: Case report, Histoplasmosis, HIV, Maxillary osteolysis, Immunocompromized

Background

Histoplasmosis is caused by a dimorphic saprophytic fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum which presents two variants: Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum (Hcc) and Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii (Hcd). Hcc is commonly found in soil contaminated with bird or bat droppings. Primary infection occurs through inhalation of spores [1].

Hcc can take different clinical forms including Disseminated Histoplasmosis (DH) in immunocompromised individuals, such as patients with Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). DH is associated with AIDS in 70% to 90% of cases in endemic countries such as South American countries; however, it remains extremely rare in European countries. DH can involve various organs and naso-oral histoplasmosis is an uncommon manifestation of DH [2, 3].

This article reports the first case of nasal-oral histoplasmosis with naso-maxillar osteolysis in a patient infected by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) at AIDS stage, in a non-endemic country. Naso-maxillar osteolysis can be observed in tumors, infections, granulomatosis, vasculitis or drug exposure.

Our aim is to describe the clinical presentation, the diagnoses issues and the etiologic and functional treatments of naso-oral histoplasmosis.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 53 year-old woman, originally from Haiti, living in France since 1989. She was hospitalized in the infectious diseases department of Bichat Claude Bernard University Hospital in Paris in March 2016 for alteration of general condition, fever and nasal deformity evolving for at least 6 months.

Her medical history is characterized by an HIV infection diagnosed in 2006, which was classified at AIDS stage in 2008 due to cytomegalovirus infection. At the same time, she suffered from pulmonary histoplasmosis that was treated with itraconazole. CD4 cell count nadir amounted to 7/mm3 in 2008. A first line of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) was started 3 weeks after those diagnoses consisting in Efavirenz (EFV), Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF) and Emtricitabine (FTC). After 1,5 months the patient decided to interrupt this treatment, a second line of HAART was initiated 6 months later with nevirapine and TDF/FTC. She only took secondary prophylaxis with itraconazole for 6 months and then stopped being compliant with any treatment and was lost to follow-up over 7 years. No history of recent travel to endemic areas or contact with neither birds nor bats was reported. She never smoked, did not have excessive alcohol consumption and did not inhale any nasal drugs.

At hospital admission, physical examination revealed a nasal tip collapse, a disappearance of the nasal septum and a large perforation of the hard palate, resulting in naso-oral communication. Facial skin, alar and triangular cartilages were undamaged. However, maxillary teeth [4, 5] were loose, and teeth 11, 21 and 22 fell spontaneously. Mucosa of the nasal cavity was ulcerated with crusts and partially necrotic (Fig. 1). The sinus CT-scan and the magnetic resonance imaging performed showed: a complete loss of the nasal septum, a maxillar osteolysis, a communication between oral and nasal cavities and bilateral maxillary sinus opacities (Fig. 2). The chest X-ray showed an interstitial pneumonia. She did not manifest dyspnea, cough, cutaneous eruption, neurologic deficit, visceromegaly or lymphadenopathy. HIV viral load was 56,943 copies/ml and CD4 cell count was 9/mm3 (2%). In blood: Treponema Pallidum Hemagglutination Assay and Veneral Disease Research Laboratory, Cryptococcus antigen, Toxoplasma polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Leishmania PCR, galactomannan antigen, blood and mycological (×4) cultures were all negative. β-D-Glucane was positive at 338 pg/ml. Blood Hcc PCR was positive. In bronchoalveolar fluid: cultures, Cryptococcus antigen were negative, Pneumocystis jirovecii PCR level was barely positive (18,000 copies/mL), After 3 months, Mycobacterium tuberculosis sputum cultures were negative.

Fig. 1.

Clinical presentation of the case. a: Three-quarter picture of the face; b: Profile picture of the face; c: Face picture of the face showing lack of teeth 11, 21 and 22 which fall spontaneously; d: Bottom view of the face: nasal tip collapse, hard palate lysis and remaining nasal septum through the hole

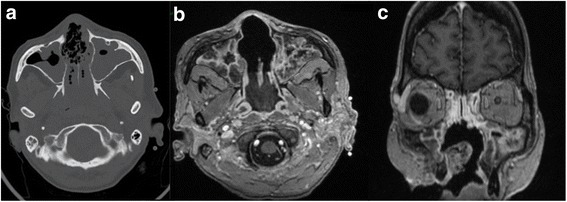

Fig. 2.

Imaging exploration. a: Sinus CT-scan showing bony nasal septum lysis and bilateral maxillary sinus opacities; b and c: Gadolinium-enhanced T1 weighted MRI (b: axial section; c: frontal section) showing bony nasal septum lysis and maxillar lysis without enhanced tumor mass

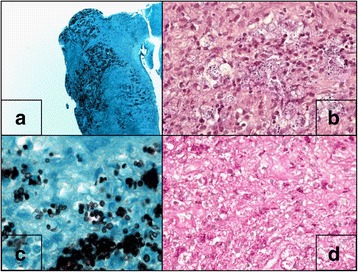

Surgical biopsies of oral, nasal and maxillary mucosa were performed and analyzed. Microscopic examination revealed fungal yeasts (Fig. 3), mycological cultures identified the presence of Hcc then confirmed by PCR.

Fig. 3.

Histological analysis of naso-maxillar biopsy. a and c: Grocott staining; b: Gram Wegert staining; d: PAS staining

Those tests enabled a final diagnosis of DH with naso-oral involvement in an AIDS-stage patient.

The patient received 200 mg per day of intravenous Amphotericin B (AmphoB) liposomal for 1 month. In the follow-up, we observed: negativation of blood histoplasmosis PCR in 10 days and clinical stabilization of naso-maxillary osteolysis with normalization of mucosa. Treatment was switched to 400 mg of oral itraconazole per day for a minimum of 1 year, in accordance with international guidelines [6].

HAART by ritonavir-boosted darunavir and TDF/FTC was reintroduced after 3 weeks of positive response to DH treatment. After 6 months, HIV viral load was undetectable and CD4 cell count at 40/mm3. At 9 months, biological results were stable and she had gained 17 k. Strategy of directly observed therapy permitted full compliance and the patient didn’t report any side effect with any treatment. Blood levels of itraconazole and HAART were both in the standards.

Ulceration and inflammation of the mucus decreased, enabling a palatal prosthesis to be implemented. A reconstructive surgery will be proposed to the patient upon completion of antifungal therapy and stabilization of HIV infection.

Discussion

In immunocompromised individuals such as AIDS patients, especially when CD4 cell count is under 150/mm3, Hcc can produce a DH involving various organs, such as: liver, spleen, bone marrow, lymphnodes, gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system [2, 7]. Oral histoplasmosis is a rare lesion in DH and is hardly documented even in endemic regions. Palate, gingiva and tongue are the most frequently locations [3, 8]. Naso-maxillar histoplasmosis is extremely rare; we report the first case in a non-endemic country. It has previously been described that the lower CD4 T cell count is, the higher the probability of nasal and mucous lesion as manifestation of DH [7, 9, 10]. Our patient‘s very low CD4 T cell counts supports this hypothesis.

Other etiologies of naso-maxillar osteolysis have to be discussed and ruled out: i) non-infectious etiologies (malignant tumors, Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis and consequences of drug exposure) and ii) other infectious etiologies (tuberculosis, leprosy, leishmaniosis, paracoccidioidomycosis and mucormycosis). The most frequent infectious cause of nasal lesion in AIDS patients is leishmaniosis.

The issue is that histoplasmosis can be confused with leishmaniosis for the following reasons: first of all Histoplasma yeasts could be interpreted as Leishmania amastigotes in direct examination; second, leishmaniosis frequently affects nasal mucosa [11, 12].

Because of its severity, mucormycosis must be explored and ruled out in this context, since very similar cases of maxillary osteolysis have been reported [13].

Chronic nasal ulcerations and nasal septum perforation can be symptoms of vasculitis, especially granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) also known as Wegener’s granulomatosis. Unfortunately, the histological results show the classical triad of granulomatous inflammation, necrosis and vasculitis in up to 16% of cases of GPA. Diagnosis of GPA is based on a combination of clinical symptoms, histology and positive c-ANCA serology [14]. One case of naso-septal perforation related to Takayashu’s arteritis is reported [4]. In Behçet disease, patients with nasal mucosa involvement do not have more nasal manifestations than those without [15]. However no case of maxillary osteolysis caused by vasculitis has been reported in the literature so far.

An increasing cause of midface destructive lesions is cocaine exposure. Ischemia, mucociliar clearance modification, bacterial infection and lesions due to intranasal consumption lead to septal and hard palate perforation [16, 17]. In this context, a rise of c-ANCA may be possible, and may lead to a misdiagnosis with GPA. Nevertheless, necrosis and inflammation without vasculitis would be observed at histology examination [18].

At last, maxillary osteolysis can be observed in malignant tumors like mucoepidermoid carninoma, squamous-cell carcinoma and lymphoma [19, 20]. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection has to be highlighted because of its severity and the difficulties to diagnose it. It can lead to a misdiagnosis such as GPA [21, 22].

In literature only 18 cases of nasal mucosa involvement due to Hcc have been reported (Table 1). Three of them died because of delay in introducing treatment or non-adherence to treatment. Treatment was either AmphoB or itraconazole. Among patients, 12 had HIV related immunodeficiency, when it was reported, CD4 cell counts was always <150/mm3.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of nasal and oral histoplasmosis in 18 patients

| N°/Ref | Sex | Age (years) | Risk Factor | CD4 (/mm3) | Clinical Presentation | Diagnosis | Location | Treatment | Follow up (M: months) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [31] | M | 32 | HIV infection | 60 | Pain | Histology | Nasal septum perforation | Amphotericin B then itraconazole | 6 M, Improvement | Colombia |

| 2 [31] | F | 37 | HIV infection | 133 | Nasal itch, epistaxis, nasal discharge | Histology | Nasal septum perforation | Itraconazole | 2 M, Improvement | Colombia |

| 3 [32] | M | 59 | HCV infection | Nose wound with crust | Not available | Nasal ulceration covered by crusts | Itraconazole | 1 M, Improvement | Brazil | |

| 4 [33] | M | 27 | HIV infection | 20 | Fatigue, fever, skin lesions, dyspnea | Histology | Disseminated (nasal ulceration and cutaneous) | Amphotericin B then itraconazole | Improvement | Argentina |

| 5 [34] | M | 37 | HIV infection | Not available | Fever, dysphagia, inflammatory and hemorrhagic nasal process | Histology | Destruction of nasal septum | No treatment | Death | Brazil |

| 6 [35] | M | 30 | None | Nasal swelling | Histology | Nasal crusts | Itraconazole | Lost follow-up | India | |

| 7 [23] | F | 79 | Farmer | Fatigue, nasal obstruction | Histology | Nasal ulceration and crusts | Itraconazole | Lost follow-up | USA (Ohio) | |

| 8 [36] | M | 37 | Renal transplant, HBV/HCV coinfection | Nose septal destruction | Not available | Ulceration in mouth and nose | Amphotericin B then itraconazole | 1 M, Improvement | Brazil | |

| 9 [37] | F | 32 | HIV infection | 69 | Fatigue, fever, nasal pain, nasal pyramid collapse | Histology | Destruction of the cartilaginous septum, columella and left nasal wing, and ulcerations | Amphotericin B | 12 M, Improvement | Brazil |

| 10 [38] | M | 39 | HIV infection | 20 | Nasal congestion, post nasal rhinorrhea, cough | Histology | Sinusitis, Skin rash, pulmonary involvement | Itraconazole | Improvement | USA (La) |

| 11 [39] | F | 49 | HIV infection | Not available | Nasal obstruction | Histology and culture | Lesion on the nasal vestibule and septum | Not available | Death | Brazil |

| 12 [39] | F | 23 | HIV infection | Not available | Not available | Histology | Crusts | Amphotericin B then itraconazole | Improvement | Brazil |

| 13 [40] | M | 43 | HIV infection, farmer | 15 | Nasal regurgitation | Histology | Complete destruction of the nasal architecture, palatal perforation | Itraconazole | Improvement | Brazil |

| 14 [41] | M | 39 | HIV infection | 120 | Nasal obstruction, post nasal rhinorrhea, headache, epistaxis | Histology | Papular and nodular rash, polypoid and inflammatory nasal mucosa in the right nasal fossa, bulging posterior wall of the nasopharynx | Amphotericin B | Improvement | Morocco |

| 15 [42] | M | 30 | Adrenal insufficiency | Visual acuity impairment, nasal, septum and soft palate lesions | Histology | Endophtalmitis, nasal, septum and soft palate lesions | Amphotericin B (intraocular injection), itraconazole | 12 W, Improvement | Argentina | |

| 16 [43] | NA | NA | HIV infection | Not available | Not available | Not available | Mouth, gingivae, hard palate, right maxillary sinus, right nasal cavity | Not available | Not available | South Africa |

| 17 [44] | M | 76 | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Epistaxis and facial pain, facial erythema, swelling, and fever | Histology and culture | Ethmoïdal, sphenoidal and maxillary sinusitis | Amphotericin B then itraconazole | Improvement | Brazil | |

| 18 [45] | M | 36 | HIV infection, drug abuse | Not available | Fever, orodynia | Histology | Ulceration on the nasal bridge, necrotizing gingivitis and granulomatous oral lesion | Ketoconazole | 4 M, Death | Brazil |

Rizzi and al. reported a case of nasal histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent 79-year-old woman with nasal obstruction. Based on the histopathological examination, it was misdiagnosed with sarcoidosis and aggravation was observed on corticosteroids [23].

Generally speaking, diagnosis of histoplasmosis can be difficult because of its low frequency, its non-specific clinical presentation and some histological similarities with others causes of nasal damage [5, 11].

A review of literature reported only 72 patients with AIDS having presented histoplasmosis in Europe between 1984 and 2004 [24]. The diagnosis of histoplasmosis is based on mycological examination, antigen detection or detection of Histoplasma DNA by PCR. The limits are: the unlikelihood to see yeast with GIEMSA staining, the duration of the culture (up to 4 weeks) and its lack of sensitivity [25].

Antigen detection is quick (within 24 h) and allows monitoring response to treatment [26]. Unfortunately, this test is not available in non-endemic countries. Besides, false negatives results can occur especially in immunocompromised patients, as well as false positives results because of cross-reaction with other fungal infections [27]. In European countries, galactomannan antigen is usually used as a surrogate marker of histoplasmosis, especially on HIV patients. The sensitivity of this test is proportional to fungal load [28]. The negative result in our case study may be explained by the fact that it was conducted after treatment initiation.

Thanks to development of genetic diagnostic tools, histoplasmosis DNA can be detected by PCR either on blood sample or on tissue specimens. Its very good sensitivity, its 100% of specificity, and the rapidity to obtain the results make it the most reliable test as of today [29, 30]. Thus, if available, PCR must be performed on blood and tissue samples as soon as the diagnosis of histoplasmosis is suggested.

Conclusion

Nasal histoplasmosis should be suspected for patients coming from endemic region, with deep immunosuppression (especially in AIDS patients).

Our patient is the first case of nasal architecture destruction by Hcc reported to date in a non-endemic region. After 1 year of treatment, she has had a really encouraging clinical course with good compliance illustrated by: controlled HIV infection, controlled DH and significant weight gain.

Given the very wide range of etiologies, the non-specific symptoms and the difficulty of histological analysis, a reliable diagnosis requires a thorough knowledge of maxillary osteolysis causes and an efficient cooperation and communication between surgeon, infectious disease clinician, mycologist and pathologist.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (DV) upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

A.C.L., J.P. have been involved in the acquisition and analysis of data and then drafting of the infectious part of the manuscript. They took care of the patient during hospitalization in the infectious diseases department. M.Z. have been involved in the acquisition and analysis of data and then drafting the surgical and Otorhinolaryngology part of the manuscript. M.Z. and A.P. were the surgeons of the patient. V.G., S.D., A.B., C.R., A.P., D.V. have been involved in revising critically the manuscript (A.P. for the Otorhinolaryngology part and others for the infectious part). A.B., C.R., A.P., D.V have given the final approval of the version to be published. They all took care of the patient during hospitalization. D.V. and A.P. did the submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Consent of the patient was obtained.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- AmphoB

Amphotericin B

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- DRV

Darunavir

- DH

Disseminated Histoplasmosis

- EFV

Efavirenz

- FTC

Emtricitabine

- F

Female

- GPA

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HAART

Highly active antiretroviral therapy

- Hcc

Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum

- Hcd

Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- M

Male

- M

Months

- NVP

Nevirapine

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- RTV

Ritonavir

- TDF

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

- VDRL

Veneral disease research laboratory

Contributor Information

A. C. Lehur, Email: ac.lehur@gmail.com

M. Zielinski, Email: maxime.zielinski@gmail.com

J. Pluvy, Email: johanpluvy@gmail.com

V. Grégoire, Email: v.gregoire.faucher@gmail.com

S. Diamantis, Email: sylvain.diamantis@ch-melun.fr

A. Bleibtreu, Email: alexandre.bleibtreu@aphp.fr

C. Rioux, Email: christophe.rioux@aphp.fr

A. Picard, Email: annabellepicard@aol.com

D. Vallois, Phone: +0033140257816, Email: dorothee.vallois@aphp.fr

References

- 1.Sarosi G, Deepe J. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. Eighth. Edinburgh: Elsevier Science Limited and W.B. Saunders; 2015. Histoplasma capsulatum (Histoplasmosis) pp. 2949–2962. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarosi G, Johnson P. Disseminated Histoplasmosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(Suppl 1):S60–S67. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.Supplement_1.S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheat LJ, Conolly-Stringfield P. Disseminated histoplasmosis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: clinical findings, diagnosis and treatment, and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69(6):361–374. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akar S, Dogan E, Goktay Y, Can G, Akkoc N, Sarioglu S, et al. Nasal septal perforation in a patient with Takayasu’s arteritis; a rare association. Intern Med Tokyo Jpn. 2009;48(17):1551–1554. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talvalkar GV. Histoplasmosis simulating carcinoma: a report of three cases. Indian J Cancer. 1972;9(2):149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Baddley JW, McKinsey DS, Loyd JE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the Management of Patients with Histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807–825. doi: 10.1086/521259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva TC, Treméa CM, Zara ALSA, Mendonça AF, Godoy CSM, Costa CR, et al. Prevalence and lethality among patients with histoplasmosis and AIDS in the Midwest region of Brazil. Mycoses. 2017;60(1):59–65. doi: 10.1111/myc.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin R, Shapiro J, Thurman G. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980;59:1–33. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couppie P. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome related oral and/or Cutaneous Histoplasmosis: a descriptive and comparative study of 21 cases in French Guiana. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:571–576. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunha V. Mucocutaneous manifestations of disseminated Histoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: particular aspects in a Latin-American population. Clin Exper Dermatol. 2007;32:250–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaimes A, Muvdi S, Alvarado Z, Rodríguez G. Perforation of the nasal septum as the first sign of histoplasmosis associated with AIDS and review of published literature. Mycopathologia. 2013;176(1–2):145–150. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9662-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pérez C, Yoanet S, Rodríguez G. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis in a patient with AIDS. Biomedica. 2006;26(4):485–497. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v26i4.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selvamani M, Donoghue M, Bharani S, Madhushankari GS. Mucormycosis causing maxillary osteomyelitis. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2015;6(2):456–459. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.160039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greco A, Marinelli C, Fusconi M, Macri GF, Gallo A, De Virgilio A, et al. Clinic manifestations in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29(2):151–159. doi: 10.1177/0394632015617063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahram F, Zarandy MM, Ibrahim A, Ziaie N, Saidi M, Nabaei B, et al. Nasal mucosal involvement in Behçet disease: a study of its incidence and characteristics in 400 patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89(1):30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silvestre FJ, Perez-Herbera A, Puente-Sandoval A, Bagán JV. Hard palate perforation in cocaine abusers: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2010;14(6):621–628. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tartaro G, Rauso R, Bux A, Santagata M, Colella G. An unusual oronasal fistula induced by prolonged cocaine snort. Case report and literature review. Minerva Stomatol. 2008;57(4):203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stahelin L, Fialho SC, De MS NFS, Junckes L, Werner De Castro GR, Pereira IA. Cocaine-induced midline destruction lesions with positive ANCA test mimicking Wegener’s granulomatosis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2012;52(3):431–437. doi: 10.1590/S0482-50042012000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolude B, Lawoyin JO, Akang EE. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the oral cavity. J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93(5):178–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker C, Kayser G, Pfeiffer J. Squamous cell cancer of the nasal cavity: new insights and implications for diagnosis and treatment. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E2112–E2117. doi: 10.1002/hed.24391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasil’ev VI, Sedyshev SK, Gorodetskiĭ BP, Probatova NA, Gaĭduk IV, Logvinenko OA, et al. Differential diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Ter Arkh. 2012;84(7):79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aozasa K, Takakuwa T, Hongyo T, Yang W-I. Nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma: epidemiology and pathogenesis. Int J Hematol. 2008;87(2):110–117. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizzi MD, Batra PS, Prayson R, Citardi MJ. Nasal histoplasmosis. Otolaryngol--Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(5):803–804. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antinori S, Magni C, Nebuloni M, Parravicini C, Corbellino M, Sollima S, et al. Histoplasmosis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected people in Europe: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85(1):22–36. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000199934.38120.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheat LJ. Current diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11(10):488–494. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheat LJ. Histoplasmosis: a review for clinicians from non-endemic areas. Mycoses. 2006;49(4):274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durkin M, Witt J, LeMonte A, Wheat B, Connolly P. Antigen assay with the potential to aid in diagnosis of Blastomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(10):4873–4875. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4873-4875.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivière S, Denis B, Bougnoux M-E, Lanternier F, Lecuit M, Lortholary O. Serum Aspergillus galactomannan for the management of disseminated histoplasmosis in AIDS. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2012;87(2):303–305. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buitrago MJ, Canteros CE, Frías De León G, González Á, Marques-Evangelista De Oliveira M, Muñoz CO, et al. Comparison of PCR protocols for detecting Histoplasma capsulatum DNA through a multicenter study. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2013;30(4):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dantas KC, Freitas RS, Moreira APV, Da Silva MV, Benard G, Vasconcellos C, et al. The use of nested polymerase chain reaction (nested PCR) for the early diagnosis of Histoplasma capsulatum infection in serum and whole blood of HIV-positive patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(1):141–143. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962013000100025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaimes A, Muvdi S, Alvarado Z, Rodríguez G. Perforation of the nasal septum as the first sign of histoplasmosis associated with AIDS and review of published literature. Mycopathologia. 2013;176(1–2):145–150. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9662-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manzini M, Lavinsky-Wolff M. Nasal histoplasmosis without lung involvement in an immunocompromised patient. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;78(5):136. doi: 10.5935/1808-8694.20120022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rico MF, Asensio P, Pavón G, Scasso M, Brusco J, Chabbert PM, et al. Histoplasmosis diseminada. Arch Argent Dermatol. 2010;60:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oikawa F, Carvalho D, Matsuda NM, Yamada AT. Histoplasmosis in the nasal septum without pulmonary involvement in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: case report and literature review. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128(4):236–238. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802010000400012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sood N, Gugnani HC, Batra R, Ramesh V, Padhye AA. Mucocutaneous nasal histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent young adult. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73(3):182–184. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.32743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motta ACF, Galo R, Lourenço AG, Komesu MC, Arruda D, Velasco FG, et al. Unusual orofacial manifestations of histoplasmosis in renal transplanted patient. Mycopathologia. 2006;161(3):161–165. doi: 10.1007/s11046-005-0195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felix F, Gomes GA, Pinto PCL, Arruda AM, Da Penha Costa Marques M, Tomita S. Nasal histoplasmosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120(1):67–69. doi: 10.1017/S0022215105006432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butt AA, Carreon J. Histoplasma capsulatum sinusitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(10):2649–2650. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2649-2650.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Machado AA, Coelho IC, Roselino AM, Trad ES, Figueiredo JF, Martinez R, et al. Histoplasmosis in individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): report of six cases with cutaneous-mucosal involvement. Mycopathologia. 1991;115(1):13–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00436416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehta V, De A, Balachandran C, Monga P. Mucocutaneous histoplasmosis in HIV with an atypical ecthyma like presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15(4):10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elansari R, Abada R, Rouadi S, Roubal M, Mahtar M. Histoplasma capsulatum sinusitis: possible way of revelation to the disseminated form of histoplasmosis in HIV patients: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;24:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlaen A, Ingolotti M, Couto C, Jacob N, Pineda G, Saravia M. Endogenous Histoplasma capsulatum endophthalmitis in an immunocompetent patient. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2015;25(4):e53–e55. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White J, Khammissa R, Wood NH, Meyerov R, Lemmer J, Feller L. Oral histoplasmosis as the initial indication of HIV infection: a case report. SADJ J South Afr Dent Assoc Tydskr Van Suid-Afr Tandheelkd Ver. 2007;62(10):452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alves MD, Pinheiro L, Manica D, Fogliatto LM, Fraga C, Goldani LZ. Histoplasma capsulatum sinusitis: case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2011;171(1):57–59. doi: 10.1007/s11046-010-9345-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Souza Filho FJ, Lopes M, Almeida OP, Scully C. Mucocutaneous histoplasmosis in AIDS. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133(3):472–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (DV) upon reasonable request.