Abstract

Background:

Common mental disorders, such as mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders, are significant contributors to disability globally, including India. Available research is, however, limited by methodological issues and heterogeneities.

Aim:

The present paper focuses on the 12-month prevalence and 12-month treatment for anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders in India.

Materials and Methods:

As part of the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative, in India, the study was conducted at eleven sites. However, the current study focuses on the household sample of 24,371 adults (≥18 years) of eight districts of different states, covering rural and urban areas. Respondents were interviewed face-to-face using the WMH Composite International Diagnostic Interview after translation and country-specific adaptations. Diagnoses were generated as per the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition, Diagnostic Criteria for Research.

Results:

Nearly 49.3% of the sample included males. The 12-month prevalence of common mental disorders was 5.52% - anxiety disorders (3.41%), mood disorders (1.44%), and substance use disorders (1.18%). Females had a relatively higher prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders, and lower prevalence of substance use disorders than males. The 12-month treatment for people with common mental disorders was 5.09% (range 1.66%–11.55% for individual disorders). The survey revealed a huge treatment gap of 95%, with only 5 out of 100 individuals with common mental disorders receiving any treatment over the past year.

Conclusion:

The survey provides valuable data to understand the mental health needs and treatment gaps in the Indian population. Despite the 12-month prevalence study being restricted to selected mental disorders, these estimates are likely to be conservative due to under-reporting or inadequate detection due to cultural factors.

Keywords: Anxiety disorders, common mental disorders, India, mood disorders, prevalence, substance use

INTRODUCTION

As per the World Mental Health (WMH) surveys conducted in various countries around the world, the 12-month prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders ranged between 3.3% and 26.3%. The 12-month prevalence in the Asian and African regions was reported to be on the relatively lower side, varying between 3.3% and 7.4%.[1,2] Common mental disorders are an important source of health loss and global burden. As per the most recent estimates from the Global Burden of Disease study 2015, depressive disorders are ranked as the single largest contributor to nonfatal health loss (7.5% of all years lived with disability [YLDs]) affecting 4.4% of global population, whereas the anxiety disorders are the sixth largest contributor (3.4% of all YLDs) affecting 3.6% of the global population.[3] The majority of the people suffering from these disorders do not receive appropriate treatment and care, especially in developing countries with resource constraints.[4]

In India, several surveys over the past few decades have attempted to determine the prevalence of mental disorders, but these were mostly confined to a single geographical area. Furthermore, these had a variety of methodological problems, such as nonrandom sampling, unvalidated screening instruments, obtaining information only from proxy respondents, a lack of focus on common mental disorders and unclear time frames for estimating prevalence, and making them incomparable. The prevalence rates of mental morbidity in these surveys have varied from as low as 1%–13%.[5,6,7] Consequently, no national-level consensus has been possible based on these surveys for a large and diverse country like India. Box 1 shows the country profile and mental health resources.[8,9,10,11] A strong need, therefore, exists to generate basic epidemiological data using a rigorous and comparable methodology across diverse regions of the country that can assist in planning services and support the resource allocation decisions.

Box 1.

India: Country profile and mental health scenario

We report here results from a multi-site epidemiologic survey across different parts of India under the WMH Survey Initiative, focused on prevalence, correlates, functioning, physical comorbidity, and treatment seeking for mental disorders in the country. The WMH survey is a series of coordinated surveys conducted across 29 countries using similar methods and instruments to facilitate cross-national comparisons.[12] It is an endeavor to contribute toward understanding the global prevalence of mental disorders and providing comparable estimates across a range of high-, middle-, and low-income countries.

The present paper focuses on the 12-month prevalence and 12-month treatment for anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders in India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

As part of the WMH survey in India, the study was conducted in the year 2005, at eleven sites of different states across India, chosen based on their capacity to handle the survey-related work, experience of investigators and infrastructure with regard to research and health systems and ensuring geographical spread across the country. These sites were as follows (a) Faridabad, (b) Lucknow, (c) Bhavnagar, (d) Pune, (e) Tirupati, Chittoor, (f) Pondicherry, (g) Dibrugarh, (h) Imphal, (i) Chandigarh, (j) Ranchi, and (k) Bangalore. During the process of review of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) data from all sites, several data quality controls were performed using predefined indicators, including a validation/clinical reappraisal using Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN), a gold standard for psychiatric diagnosis and administered by trained psychiatrists (on 10% of study sample at each site; n = 3347). As the analysis of the SCAN interviews revealed nearly no one with any mental or behavioral disorder at three sites (Chandigarh, Ranchi, and Bangalore) in the validation exercise, it was decided to drop these three sites from the pooled dataset used in the current study following discussions between experts participating in the survey as well as the World Health Organization (WHO)-team.

The eight sites together had a household sample of 24,371 individuals, aged 18 years or above. The survey sites (districts) represent various states and parts of India. The de-facto population of the entire district was sampled, using the 2001 national population census data[13] as the sampling frame. Households were selected using a stratified multistage cluster sampling with probabilities proportional to the size and one adult 18 years and older per household was selected randomly using the Kish tables.

Survey instrument

Respondents were interviewed using the WMH-CIDI, which is an updated version of the WHO CIDI 3.0 designed specifically for the WMH Survey Initiative.[12] The CIDI is a fully structured interview that generates a diagnosis of commonly occurring mental disorders according to definitions and criteria of both Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV[14] and International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition Diagnostic Criteria for Research (ICD-10-DCR).[15] The paper and pencil instrument (PAPI) was used in India, with responses marked on a separate modified scoresheet. Adequate inter-rater reliability, test-retest reliability, and validity have been documented for earlier CIDI versions.[16] The survey was carried out by lay trained interviewers following a week long structured training in the use of the survey instrument.

The WMH-CIDI begins with a screening section with a series of introductory questions about the respondent's general health and diagnostic stem questions for all core diagnosis. This is followed by 18 diagnostic sections, three sections on functioning and physical comorbidity, two sections on treatment and eight sections on sociodemographic correlates. The disorders assessed by the WMH-CIDI include (a) mood disorders; (b) anxiety disorders; (c) substance use disorders; (d) childhood disorders; and other (intermittent explosive disorder, eating disorders, premenstrual disorder, nonaffective psychoses screen, pathological gambling, and neurasthenia, personality disorders screens). It is to be noted that schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychoses; although, important serious mental disorders were not included in the core WMH assessment because they are significantly overestimated in lay-administered structured interviews and need an alternative sampling and validation strategy requiring clinical interviews.[17,18] The current paper focuses on the common ICD-10-DCR mental and behavioral disorders (i.e., anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance use disorders).

Translation and adaptation

The survey instrument underwent a rigorous process of adaptation to obtain a conceptually and cross-culturally comparable versions in the Indian languages used in the survey.[12,19] The original English instrument was translated to seven Indian languages as per the standard WHO translation protocol (forward-translation, expert panels, back-translation, and pretest/cognitive interviewing) with a focus on conceptual rather than linguistic equivalence. A few country-specific adaptations were made to include the relevant list of religions and social class, modifications to the list of income categories, relevant drugs, and practitioners of alternative medicine, including traditional healers. All supporting materials, including a respondent booklet, were also translated. A pilot survey was conducted on 10-50 respondents per site where interviews were conducted by survey interviewers as well as supervisors to address linguistic problems and assess feasibility.

Ethical aspects

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi before beginning the survey. Standardized descriptions of the goals and procedures of the study, data uses and protection, and the rights of respondents were provided in both written and verbal form to all respondents, and verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study procedure

Respondents from the selected households were contacted by the survey interviewers. In the case of the selected respondent's nonavailability at home, three to five callbacks were attempted to complete the interview before considering the household as a nonrespondent household. At the end of an interview, the respondents were provided with a list of local mental health resources and other public contacts for assistance in help-seeking.

Data processing and analysis

A computerized direct data entry (DDE) program was used to enter data from PAPI. The program checked for inconsistencies and field checks to disallow invalid codes. Each study site was required to send an error report to the coordinating center at AIIMS, New Delhi. The first 500 records were sent for review to the WMH coordinating center along with compiled error reports. After cleaning programs were run, a modified DDE instrument was sent back. Data were migrated to this modified DDE instrument and used for the rest of the survey period. Data from each site were merged into a master data file. The master file was used to create site-specific data files. Sampling weights were created based on the survey design. All analyses were carried out using SPSS. Statistical significance was consistently evaluated using 0.05 level two-sided tests.

RESULTS

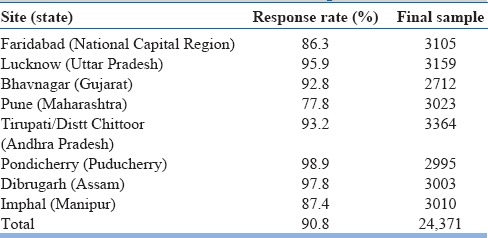

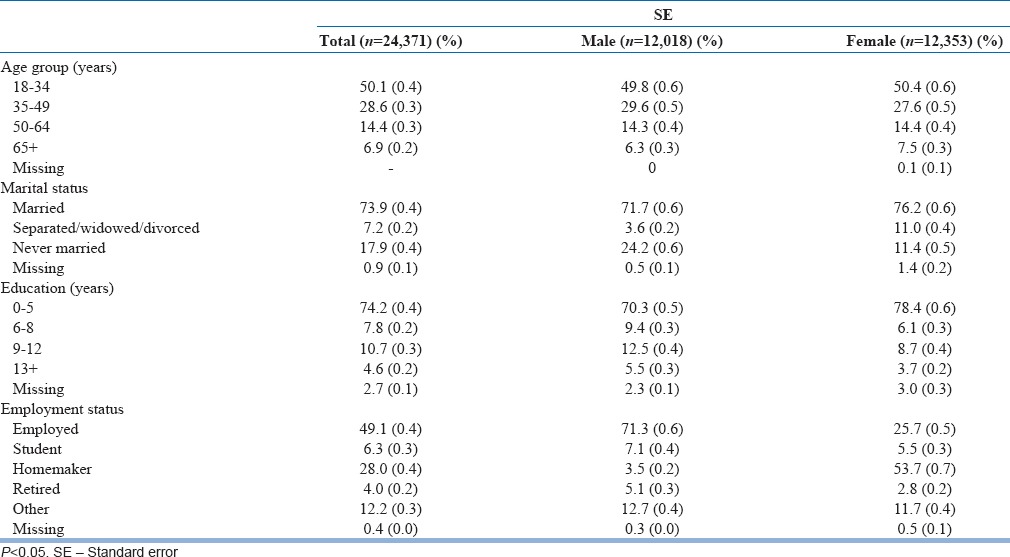

Of the initially targeted sample of 26,852 individuals across eight districts, the average response rate was 90.8%. The final sample size comprised 24,371 individuals. Table 1 shows the sample and response rates for each of the eight sites. There were 49.3% (n = 12,018) males and 50.7% (n = 12,353) females. Of the total sample, half were in the age group of 18–34 years, nearly three-fourths were married and three-fourths were educated up to primary level or below [Table 2].

Table 1.

Site-wise sample

Table 2.

Sample characteristics

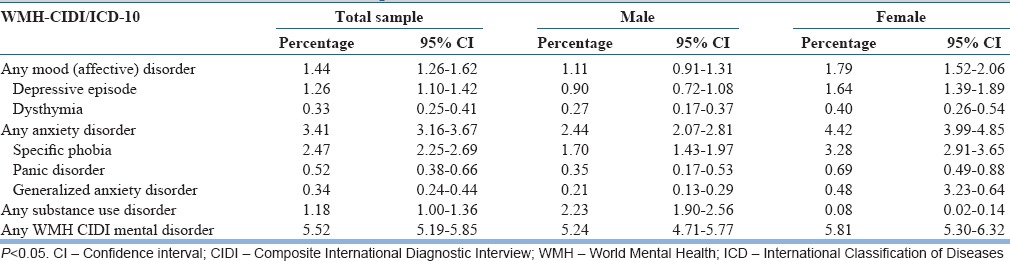

In the total sample, the 12-month prevalence of any mental or behavioral disorder is 5.52%. Table 3 shows the 12-month prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Compared to males, the prevalence of anxiety disorders was nearly twice (4.42% vs. 2.44%) and that of mood disorders was 1.6 times (1.79% vs. 1.11%) higher among females. Substance use disorders were more common among males (2.23% vs. 0.08%) than females.

Table 3.

Tweleve-month prevalence: Common mental and behavioral disorders

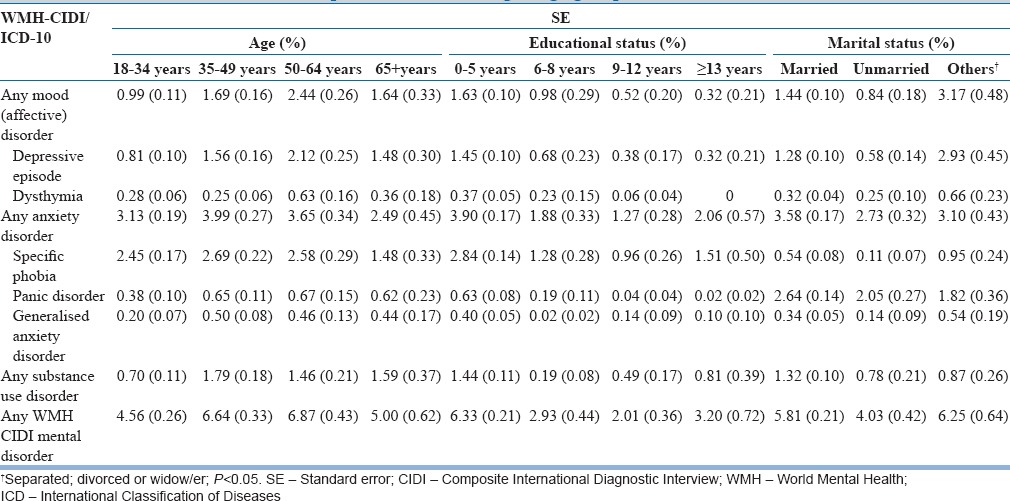

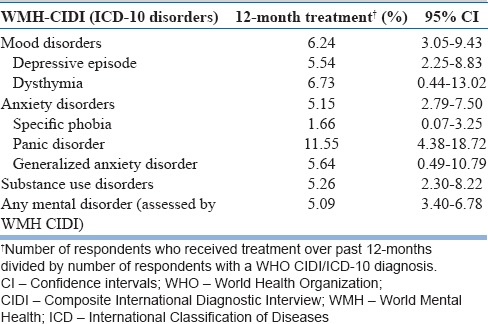

The 12-month prevalence rates according to age, education, and marital status are shown in Table 4. The treatment sought for individuals with diagnosable mental or behavioral disorders over the past 12-month duration is shown in Table 5. The rates for treatment varied between 1.66% and 11.55% for various disorders, with an overall rate of 5.09%. Only 5 of the 100 individuals with any mental or behavioral disorders received treatment over the past 1 year.

Table 4.

Tweleve months prevalence according to age group, educational, and marital status

Table 5.

Treatment seeking in sub-sample with diagnosable mental disorders

DISCUSSION

This is the first systematically conducted a comparable epidemiological survey for mental disorders on a large representative sample from multiple sites across India. The current paper focuses on the 12-month prevalence and 12-month treatment for anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders.

Twelve-month prevalence of any World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview disorder

The 12-month prevalence of any common mental disorder was 5.52% in the present survey. Previous single-site community studies from India have found a wide range of prevalence for mental disorders and two available meta-analyses of select Indian studies reported prevalence estimates to be 5.8% and 7.3%.[6,7] However, as noted earlier, most surveys had a variety of methodological problems limiting their utility. In contrast, the present survey employed a rigorous sampling, a structured diagnostic instrument, a large representative sample drawn from multiple sites and a uniform training protocol. The findings are, therefore, likely to be more reliable and have a potential for wider applicability.

Comparing with the WMH survey findings from other western regions, the 12-month prevalence in India (5.52%) is on the lower side. In comparison to India, the 12-month prevalence was found to be nearly five times higher in WMH survey from the United States (26.3%), 2–4 times higher in the European Union and 2–3 times higher in South American countries.[1,20,21] However, the prevalence in India is relatively comparable to WMH survey findings from other Asian countries (China: 7.1%, Japan: 7.4%).[1] The Nigerian survey (African region) reported a 12-month prevalence (3.3%) which was lower than India. In a previously published paper from one of the sites at Pune, Maharashtra, the 12-month prevalence of mental disorders was 3.18%, most common being depression (1.75%), followed by substance use disorder (0.99%) and panic disorder (0.69%).[22] The average 12-month prevalence estimate (in which only Pondicherry data were included from India) for bipolar spectrum disorders was 1.5% for eleven countries.[23]

This 12-month prevalence figure should, however, be interpreted with caution. Even for these otherwise common disorders, the prevalence found in this survey is most likely on the lower side of the true prevalence figures due to a multitude of reasons. The survey focused mainly on detection of disorders that cross the threshold for the disorder as stated in the ICD-10-DCR, but the subthreshold or subsyndromal disorders are often more common and disabling. It has been reported that the subthreshold depressive disorders occur commonly all across the world, produce significant decrements in health and do not qualitatively differ from full-blown episodes of depression.[24] The mental health care needs of the country would be substantially higher if these disabling subthreshold symptoms are considered together with diagnosable mental disorders. Under-detection of mental morbidity may occur due to cultural variations in the expression of a particular disorder across different cultures and nations. For example, “somatized depression” is a frequent clinical presentation in India. The WMH-CIDI instrument may fail to detect these cultural differences in phenomenology and follows a narrow definition of mental disorders and rigid diagnostic criteria, which may not behave in the same manner in Asian as compared to Western countries where most such epidemiological studies are conducted.[25] In addition, under-reporting of symptoms due to stigma and embarrassment related to mental disorders in the Indian setting may also have contributed to the lower prevalence. Finally, it needs to be emphasized here that the figure is restricted to selected mental disorders, and the data on other psychiatric disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorders, somatization disorders, and dissociative disorders, have not been included in this study.

Anxiety and mood disorders: Twelve-month prevalence and distribution

Over the past 12 months, anxiety disorders (3.41%) were the most common followed by mood (depressive) disorders (1.44%). Among anxiety disorders, specific phobia was the most common and among mood disorders, depressive episode was the most common disorder. Previous studies from primary care and community settings in India have also indicated anxiety neurosis and depression to be common conditions,[26] with an estimate of 1%–1.7% for anxiety disorders and 1.2%–3.4% for various types of depression.[6,7] Recent GBD study estimated that the depressive disorders affect 4.4% and anxiety disorders affect 3.6% of the global population in the year 2015.[3,4]

This pattern is consistent with findings from almost all the other WMH surveys. The 12-month prevalence for any anxiety disorder ranged between 2.4% and 18.2% and any mood disorder between 0.8% and 9.6% across multiple nations from various regions.[21] Another review of international studies reported an overall average prevalence estimate of 10.6% for any anxiety disorder, 4.1% for major depression and 2% for dysthymia in the 12-month before assessment.[27] These common mental disorders are responsible for a significant proportion of disability across various cultures in the world.[28]

Mental disorders appear to be differentially distributed across various sociodemographic groups. The female preponderance for anxiety (1.6:1) and mood disorders (2:1) is a well-established finding in epidemiological studies across almost all other countries.[29,30,31] Besides being more prevalent, depression is also likely to be more chronic and persistent among females, which may contribute to higher 12-month prevalence rates. Several factors, including low education, recent intimate partner violence, and spousal substance use have been associated with poorer outcomes for common mental disorders among women.[32]

The 12-month prevalence of mental disorders, including anxiety and mood disorders, appear to be lowest in the 18–34 years age group with an increase over the subsequent age groups with highest rates in the 50–64 years age group. This may be the result of increasing stress, cumulative life events, or declining physical health with the advancement of age. Data from other WMH surveys have shown mixed findings, with some reporting no association with age,[33] others reporting a higher past 12-month prevalence at the younger age[34] and still others reporting a peak between 35 and 50 years.[35] The considerably higher prevalence observed in the widowed/separated/divorced group could be due to more social stressors and life events among this group. The overrepresentation of females in this sub-group could have contributed to the finding. Those in the lowest education category (0–5 years) appear to be at a disadvantageous position. Several social (e.g., poverty), demographic (e.g., gender), or psychological (e.g., low problem-focused coping) factors associated with low education may contribute to this finding. Those with postgraduate or above education had the lowest overall disorder-specific prevalence rates. Higher levels of education have been previously shown to have a positive effect on mental health.[36]

Substance use disorders: Twelve-month prevalence and distribution

The 12-month prevalence of substance use disorders (viz., alcohol and drug use disorders, including harmful use and dependence) was 1.18% for both genders and 2.23% for the male sample. These are the first prevalence figures for “diagnosable” substance use disorders in a large representative sample from multiple sites across India. Previously, a national survey for extent, pattern, and trends of drug use was carried out in India,[37] but it had focused on any lifetime or current “use,” even if a single use, without an ascertainment of diagnosis of substance use disorder.

Comparing with other WMH surveys, the 12-month prevalence for substance use disorders was 3.8% in the United States, 2.5%–2.8% in South American countries, and 0.1%–3% in Europe (with the exception of 6.4% in Ukraine).[1,21] The overall 12-month prevalence in India is similar to that reported from Asia (0.5%–1.7%), Middle East (Lebanon: 0.8%), and Africa (Nigeria: 1.3%).[26,34,38,39]

The very low rates for female substance use are common findings in nonwestern countries since sociocultural mores prohibit the use of alcohol and drugs among females. Substance use is more socially acceptable for men and is typically regarded as a machismo behavior.[40] Only 0.1% of females had a substance use disorder in the present sample, but it is possible that prevalence of “use” of substances may be more common among females in certain sections or parts of the country.

Another notable finding is that nearly 1.6% of those aged 65 years and above had a substance use disorder. There is hardly any data for geriatric substance use in the Indian context, apart from a few small scale studies.[41,42] There is a need more clinical and public health attention to geriatric substance use, which should also be reflected in the respective policies for substance use and geriatric health in India.

Twelve-month treatment for mental disorders

Only 5 of the 100 individuals suffering from any mental disorder over the past year received any treatment (with 95% of people with any mental disorder not receiving treatment, pointing to a huge treatment gap). Across the other WMH surveys, the rates for treatment varies between 0.8% for Nigeria and 15.3% in the United States.[43] Treatment rates in India are closer to Mexico and Colombia (4.2%–5%) and Asian countries (2.7%–5.7%). The treatment rates varied from as low as 1.66% for specific phobia to nearly 5%–6% for depressive episode, generalized anxiety, and substance use disorders to a maximum of 11.55% for panic disorder. The sudden unexpected and catastrophic nature of panic attacks, at times mimicking serious physical illness, may be responsible for higher rates of help-seeking in panic disorder.

Several factors are responsible for poor treatment-seeking in countries like India. Low perceived need and attitudinal barriers were found to be the major barriers to seeking and staying in treatment among individuals with common mental disorders worldwide, including in India.[44] Most importantly, the conceptualization of mental disorders in traditional societies does not strictly follow the medical perspective, and more often rely on explanations provided by alternate systems of medicine (e.g., ayurveda), supernatural causations or other cultural beliefs (mis-deeds, past-life sins, ancestral displeasure, etc.). Apart from that, mental illnesses are often stigmatized and are viewed as a source of shame for the entire family. The traditional healers or religious practitioners form the common source for seeking help, especially in the rural India.[45] In a case-vignette based study, respondents showed a preference for lay help over medical help even when they labeled the illness as mental disorder.[46] Special diets, tonics, appetite stimulants, and sleeping pills were strongly endorsed, but awareness of psychiatric medications was negligible.[47] Another major contributing factor is the lack of mental health-care services and resources in most parts of the country. The public sector mental health services are mostly limited to secondary or tertiary care settings. In terms of public sector services for substance use treatment, there are only 122 drug de-addiction Centers by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and 442 centers (primarily as nongovernmental organizations) supported by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.[48,49] The average national deficit of trained psychiatrists in India is estimated to be 77% (0.2 psychiatrists per 100,000 population).[10] Most general physicians are also not sufficiently equipped with the knowledge or skills to treat the common mental or substance use disorders.

Implications of the survey findings

Nearly 5.5% of the adult population in India had a diagnosable mental disorder over the past 12-month, but only 1 in 20 of them received any treatment. Although the sample did not represent all states of India, if these figures were to be extrapolated to the adult population in India, it translates into an estimated 33.3 million adults suffering from common mental and substance use disorders over the past 1 year.

The survey has implications for future policy and service development in India. The findings provide us an insight into the magnitude of national mental health care needs and can serve as a guide for mental health planners and administrators. Ensuring adequate coverage and easy accessibility of mental health services is the first step in mental health-care provision. There is a need to strengthen the primary care infrastructure and community mental health activities. Activities directed at information dissemination and community mental health awareness should be scaled up, and care should be taken to package them in a culturally acceptable manner. The mental health services for common mental disorders require adequate numbers of mental health professionals, in the form of psychologists, social workers, nursing staff, etc., trained to deliver the psychosocial interventions. The common mental problems may not always require the intensive involvement of a psychiatrist on a regular basis which may not be feasible or practical in a low-resource country like India. The self-help approaches may also be considered as part of a stepped care approach, especially in the context of milder mental conditions with preserved functioning and social support. Mental health professionals should, however, play a key role in terms of developing effective models of care for common mental disorders in the community and being involved in the service organization and implementation at various levels. The shortage of manpower and resources can also be overcome with a greater integration of mental health with general health services at various levels. Available studies from India have demonstrated that the trained lay counselors working within a collaborative-care model may reduce the prevalence of common mental disorders, psychological morbidity, and disability days among those attending public primary care facilities.[50] Further work is needed to improve access to mental health care, given the international commitment to Universal Health Coverage in the Sustainable Development Goals and hence the need for Integrated People-Centred Service Delivery and the scaling up of WHO's mhGAP program.

More recently, a few efforts have been initiated to improve the mental health scenario in the country. These include the revision of an outdated Mental Health Act, drafting the first Mental Health Policy and the 12th 5-year plan with an expansion of mental health program and budgetary provisions. However, the transition from policy to practice is likely to be a gradual and uphill task.

Some limitations of the survey need to be considered while interpreting the findings. First, fully structured instruments such as the WMH-CIDI limit the scope for explanations and cross-examinations by interviewers. Symptom patterns and cultural variations in the phenomenology of depression (such as somatized depression) more prevalent in Asian countries may not be captured in such interviews.[25] Since the CIDI uses an approach whereby screen questions are used to determine which respondent will go on to answer further questions covering the core diagnostic sections and section on psychological distress and functioning to determine if a diagnosis of mental disorder as per the existing classificatory system is met, it is likely that respondents in different settings may have different reporting thresholds that may increase the proportion of those who are false negatives. These issues may have contributed to under-diagnosis or under-recognition of mental disorders in this cultural setting. In prior studies too, the CIDI was seen to have a downward bias in prevalence estimates in Asian countries.[25] Second, the under-reporting of psychological symptoms is expected in this setting as there is a lot of stigma and embarrassment related to mental disorders in India and across all social strata.[51] In addition, other factors, such as recall bias, may have also contributed to biasing these estimates downward. There may also be a lack of understanding regarding the intention behind the survey leading to poor motivation for answering the interview questions. Third, several practical problems were faced during field visits. Some respondents did not know their exact date of birth or did not want to disclose certain personal details. People from urban areas were especially reluctant to share information with an unknown interviewer citing privacy and security concerns. Some rural women covered their faces with a veil (as part of cultural practice) in the presence of the interviewer and or elder male members in the house which interfered with the quality of the interview. On occasions, it was difficult to ensure the privacy of the interview which may have led to limited disclosure. Many respondents did not have adequate space in their home for interview to be carried out in privacy. Many times, the married female did not wish to disclose a treatment-seeking attempt to her in-laws family members for fear of discrimination and stigma. While the survey had a good response rate (90%), some of the common reasons for refusal were a reluctance to participate citing the futility of official activities concerning data collection. Others were daily wage earners who were unable to give the extended time required for a long interview-occasionally requiring about 2 h. The households with only female members refused to consent to being interviewed by male interviewers.

Fourth, the survey was restricted to only the adult population. Child and adolescent age groups, which form over 40% of Indian population,[8] were not represented in this survey. Finally, the data from three sites had to be dropped due to implausible rates at those three sites (<1.5% at each site and further, clinical reappraisal interviews using SCAN by a trained psychiatrist found virtually no diagnosable case at these sites). Better implementation and quality assurance would have yielded improved prevalence figures from these sites.

CONCLUSION

In our view, these estimates are likely to be relatively conservative and the true prevalence is likely to be higher. The study shows that 1 in 20 adults in India have a diagnosable common mental and substance use disorders. However, only 1 in 20 of these received treatment from the health system over the past year showing the huge treatment gap that exists for these conditions. The study provides a valuable data for understanding the mental health needs of the Indian population and calls for a concerted effort to develop community-based mental health services in India on a priority basis. A regular system to monitor the mental health needs of the population is imperative to appropriately plan services to cater to this large burden. Future studies should continue to strive for improved, more culturally sensitive instruments to capture the true burden of mental disorders in India and better quality control and validation to support evidence-informed policies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the WHO (India) and Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. We acknowledge their support. We would like to thank WHO (HQ) and Prof. Ronald C. Kessler, Harvard Medical School, USA for the provision of training of the instrument, analysis, and technical guidance. We thank the coordinating staff of the WHO-WMH Survey Initiative for their consultation on field procedures, assistance with instrumentation and data analysis. We acknowledge the support/ thank all the research staff and all other persons involved in the study. We extend the gratitude to all the respondents and families for their cooperation and participation in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18:23–33. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Kola L, Makanjuola VA. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:465–71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Last accessed on 2016 Mar 09]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/prevalence_global_health_estimates/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Math SB, Chandrashekar CR, Bhugra D. Psychiatric epidemiology in India. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy VM, Chandrashekar CR. Prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders in India: A meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:149–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganguli HC. Epidemiological finding on prevalence of mental disorders in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:14–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Census of India. Office of Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs. Government of India. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khandelwal SK, Jhingan HP, Ramesh S, Gupta RK, Srivastava VK. India mental health country profile. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2004;16:126–41. doi: 10.1080/09540260310001635177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thirunavukarasu M, Thirunavukarasu P. Training and National deficit of psychiatrists in India – A critical analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(Suppl 1):S83–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The World Bank Data: Indicators. [Last accessed on 2016 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS .

- 12.Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Census of India. Office of Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, et al. Concordance of the composite international diagnostic interview version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) ith standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2006;15:167–80. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample. The National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1022–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IR, Gagnon E, Guyer M, et al. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:668–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, et al. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:122–39. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deswal BS, Pawar A. An epidemiological study of mental disorders at pune, Maharashtra. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37:116–21. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.96097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:241–51. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayuso-Mateos JL, Nuevo R, Verdes E, Naidoo N, Chatterji S. From depressive symptoms to depressive disorders: The relevance of thresholds. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:365–71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.071191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang SM, Hahm BJ, Lee JY, Shin MS, Jeon HJ, Hong JP, et al. Cross-national difference in the prevalence of depression caused by the diagnostic threshold. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:159–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gururaj G, Girish N, Isaac MK. Mental, Neurological and Substance Abuse Disorders: Strategies towards a Systems Approach, NCMH Background Papers-Burden of Disease in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2005. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 01]. Available from: http://www.who.int/macrohealth/action/NCMH_Burden%20of%20disease_(29%20Sep%202005).pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Somers JM, Goldner EM, Waraich P, Hsu L. Prevalence and incidence studies of anxiety disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:100–13. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruffaerts R, Vilagut G, Demyttenaere K, Alonso J, Alhamzawi A, Andrade LH, et al. Role of common mental and physical disorders in partial disability around the world. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:454–61. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.097519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Mental Health Aspects of Women's Reproductive Health: A Global Review of the Literature. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 01]. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43846/1/9789241563567_eng.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC. The epidemiology of depression among women. In: Keyes CL, Goodman SH, editors. Women and Depression: A Handbook for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandra PS, Satyanarayana VA. Gender disadvantage and common mental disorders in women. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22:513–24. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.516427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shidhaye R, Patel V. Association of socio-economic, gender and health factors with common mental disorders in women: A population-based study of 5703 married rural women in India. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1510–21. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Benjet C, Lara C, Berglund P. Psychiatric disorders in Mexico: Lifetime prevalence in a nationally representative sample. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:521–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Ono Y, Uda H, Hata Y, Nakane Y, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and treatment of common mental disorders in communities in Japan: Preliminary finding from the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002-2003. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:441–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herman AA, Stein DJ, Seedat S, Heeringa SG, Moomal H, Williams DR. The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. S Afr Med J. 2009;99(5 Pt 2):339–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chevalier A, Feinstein L. Sheepskin or Prozac: The Causal Effect of Education on Mental Health. 2006. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 01]. Available from: http://www.ftp.iza.org/dp2231.pdf .

- 37.Ray R. National Survey on Extent, Pattern and Trends of Drug Abuse in India. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment and United Nations Office on Drug and Crime Regional Office for South Asia. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen YC, Zhang MY, Huang YQ, He YL, Liu ZR, Cheng H, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in metropolitan China. Psychol Med. 2006;36:257–67. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karam EG, Mneimneh ZN, Karam AN, Fayyad JA, Nasser SC, Chatterji S, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders in Lebanon: A national epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2006;367:1000–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68427-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel V. Alcohol Use and Mental Health in Developing Countries. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:s87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seby K, Chaudhury S, Chakraborty R. Prevalence of psychiatric and physical morbidity in an urban geriatric population. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:121–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.82535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tiwari SC, Srivastava S. Geropsychiatric morbidity in rural Uttar Pradesh. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:266–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:841–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andrade LH, Alonso J, Mneimneh Z, Wells JE, Al-Hamzawi A, Borges G, et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1303–17. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapur RL. The role of traditional healers in mental health care in rural India. Soc Sci Med Med Anthropol. 1979;13:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(79)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srinivasan K, Isaacs AN, Villanueva E, Lucas A, Raghunath D. Medical attribution of common mental disorders in a rural Indian population. Asian J Psychiatr. 2010;3:142–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kermode M, Bowen K, Arole S, Joag K, Jorm AF. Community beliefs about treatments and outcomes of mental disorders: A mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Public Health. 2009;123:476–83. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Drug De-addiction Programme (DDAP) [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 01]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/index1.php?linkid=229&level=1&lid=1353&lang=1 .

- 49.Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. Scheme of Assistance for the Prevention of Alcoholism and Substance (Drugs) Abuse and for Social Defense Services, Government of India. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, et al. Lay health worker led intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders in India: Impact on clinical and disability outcomes over 12 months. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:459–66. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venkatesh BT, Andrews T, Mayya SS, Singh MM, Parsekar SS. Perception of stigma toward mental illness in South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:449–53. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.161352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]