Abstract

Context:

There are scarce data on the prevalence of adult obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in India.

Aims:

The aim was to study the point prevalence of OCD and subthreshold OCD and its psychosocial correlates among college students in the district of Ernakulam, Kerala, India.

Settings and Design:

A cross-sectional survey of 5784 students of the age range of 18–25 years from 58 colleges was conducted.

Materials and Methods:

Students were self-administered the OCD subsection of the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview for obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCSs), and other relevant instruments to identify OCD, subthreshold OCD, and related clinical measures.

Statistical Analysis:

The point prevalence of OCD and subthreshold OCD was determined. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square/Fisher's exact tests as necessary. Differences between means were compared using the ANOVA.

Results:

The point prevalence of OCD was 3.3% (males = 3.5%; females = 3.2%). 8.5% students (males = 9.9%; females = 7.7%) fulfilled criteria of subthreshold OCD. Taboo thoughts (67.1%) and mental rituals (57.4%) were the most common symptoms in OCD subjects. Compared to those without obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCSs), those with OCD and subthreshold OCD were more likely to have lifetime tobacco and alcohol use, psychological distress, suicidality, sexual abuse, and higher attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom scores. Subjects with subthreshold OCD were comparable to those with OCD except that OCD subjects had higher psychological distress scores and academic failures.

Conclusions:

OCD and subthreshold OCD are not uncommon in the community, both being associated with significant comorbidity. Hence, it is imperative that both are identified and treated in the community because of associated morbidity.

Keywords: Adult obsessive-compulsive disorder, correlates, India, prevalence, subthreshold obsessive-compulsive disorder

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological studies have reported that obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common psychiatric illness.[1,2] However, prevalence estimates have varied across major studies, partly owing to methodological differences, with the epidemiological catchment area study reporting lifetime prevalence of 1.9%–3.3%,[1] the Cross-National Collaborative Group reporting 12-month prevalence of 1.1%–1.8%,[2] the British National Comorbidity Survey reporting 1-month prevalence of 1.1%,[3] and the National Comorbidity Survey Replication reporting lifetime prevalence of 2.3%.[4] Asian studies from Iran[5] and Singapore[6] reported a lifetime prevalence of 1.8% and 3%, respectively.

In addition to the high prevalence of diagnosable clinical OCD, there is evidence that OCD symptoms are experienced by many people without the full OCD syndrome. Studies have reported that up to a quarter of the population experience obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCSs), sometimes in their lives.[1,4] A few studies which have examined subthreshold OCD have reported a prevalence rate of up to 12.6%.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] Community studies of OCD have reported a slight female predominance.[2,3,5] One study reported a higher prevalence of subthreshold OCD among males.[11] OCD subjects in epidemiological studies phenomenologically report predominant obsessions.[1,2,3]

According to the World Health Organization, OCD is the sixth most disabling psychiatric disorder.[15] Recent studies have reported that even subjects reporting subthreshold OCD suffer from a significant disability.[4,6]

OCD is highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses,[3,4,16] most commonly depression and anxiety disorders.[3,4,10,17] OCD is also associated with a high risk for suicidal behavior.[3,18,19] In community studies, OCD subjects tend to have high rates of substance and alcohol use disorders; however, in clinical samples, the prevalence of alcohol use disorder is somewhat low.[10,20,21,22] There is robust evidence linking attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to childhood OCD;[23,24] however, the data with regard to the relationship with adult OCD are inconsistent with reports of co-occurrence rates ranging from 0% to 60%.[24] Few studies also report high rates of sexual abuse in OCD.[25,26]

A few studies that have examined comorbid patterns in subthreshold OCD found that they were associated with elevated odds for substance abuse/dependence, mood and anxiety disorders, and somatoform disorders/syndromes when compared to the non-OCD group.[3,11,14,15] They had lower rates of comorbidity in comparison to that of OCD subjects with patterns of comorbidity mirroring that of OCD subjects.[3,14]

Literature on the prevalence and clinical correlates of OCD and subthreshold OCD in Indian population is sparse. There are no data from the adult population. Recently, in a large sample of school-going adolescents from India, we found the point prevalence of OCD to be 0.8%.[27] There are some data to suggest that the prevalence of OCD could be low in Asian countries,[2] but there are no systematic data on its prevalence and its clinical correlates in Asian countries other than those from Iran and Singapore.[5,6] It is in this background that the findings on the prevalence and correlates of OCD among college students from India are being reported. The findings reported here are part of a larger study which assessed common psychological issues among college-going young adults in the State of Kerala, India. The study reports point prevalence of OCD in young adults in the age range of 18–25 years. Since OCD tends to mostly manifest in late adolescence and young adulthood,[10] prevalence rates in young adults may closely mirror prevalence rate in the wider community. The study did not require participants to reveal their identity to avoid underreporting of symptoms in a direct face-to-face interview because of embarrassment[28] and stigma in talking about OCSs.[29] This study does not report all comorbid conditions in OCD but specifically reports on certain less well studied but important aspects of its morbidity such as psychological distress, suicidal behavior, substance/alcohol abuse, features of ADHD, and history of sexual abuse which were also assessed as part of the larger study.

The aims of this study were as follows:

To study the prevalence of self-reported OCD and subthreshold OCD among college-going young adults aged 18–25 years fulfilling the criteria for OCD as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10

To study self-reported ADHD, substance/alcohol abuse, psychological distress, suicide risk, and history of sexual abuse among subjects with OCD, subthreshold OCD in comparison with those who did not have OCD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This survey was conducted in 58 colleges in the district of Ernakulam, Kerala, India. The district has 123 colleges, most offering specialized courses, with approximately 50,000 students enrolled at any given time. A master list was initially prepared, subcategorizing the colleges into the courses they offered. The categories that were delineated were: medical, dental, nursing, engineering, law, arts and sciences, homeopathy, Ayurveda, and fisheries. The institutions for the survey were selected using stratified random sampling. At least 40% of institutions in each category were randomly selected, and for courses in which colleges were few in number (medical, dental, law, homeopathy, Ayurveda, and fisheries colleges), at least 50% were selected to ensure that they were adequately represented.

From each institution, the college administration allocated students of odd or even years of their course (i.e., 1st year and 3rd year or 2nd year and 4th year). All students in the selected classes were administered the questionnaire.

Survey administration

The survey instrument consisted of a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaires were designed in English and translated into Malayalam (the vernacular language). Another set of translators back translated the same to English, and this was consistent with the original version.

Before the survey, all students were informed that the information they provided would remain anonymous, participation was voluntary, there were no right or wrong answers, and answers would not impact their course grades in any way. Students were given the option to use either the English or Malayalam version of the questionnaire. Mental health professionals from the Department of Psychiatry, Government Medical College, Ernakulam, supervised the survey and were at hand to clarify doubts if any. Participants, on average, took about 50 min to complete the questionnaire. It was administered in a classroom setting with students sitting sufficiently apart so that answers could not be revealed to or discussed with each other.

The survey was carried out over a period of 3 months. Of 5932 eligible students, 5784 students participated (97.5%). The remaining did not participate in the survey possibly because they were free to opt out of the study if they wished. Of 5784 questionnaires, 4926 questionnaires were valid. The remaining 858 (14.8%) questionnaires were excluded from analysis as they were returned incomplete or had substantial missing items. The sample size was adequate to identify a 1% prevalence rate with 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.75%–1.25%.

Ethical considerations

The Institutional Ethics Committee of the Government Medical College, Ernakulam, approved the study for its ethical aspects, and the participating college authorities gave administrative approvals. Only students who verbally consented to participate took part in the study.

Instruments

Students completed a self-administered questionnaire which included sociodemographic data (age/sex/structure of family/area of residence/socioeconomic status/religion/academic performance), OCSs, psychological distress, suicidality, alcohol/substance use, sexual abuse, and symptoms of ADHD. The following instruments were incorporated into the questionnaire to assess these domains.

Obsessive-compulsive symptoms

The Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R),[30] obsessions and compulsions subsection was used to identify OCD. The CIS-R-19 is a standardized semi-structured interview to assess the current mental state of subjects in primary care and community settings.[31] Although this is a semi-structured interview, we employed it as a self-administered questionnaire, as was done in an earlier study on adolescents.[27] Before administering the OCD section, all students in the class were explained by a mental health professional how to rate the responses and clarified doubts if any. The OCD subsection of CIS-R has eight questions each for obsessions and compulsions in the preceding 1 week. One point is assigned for each of the following criteria: (1) symptoms present 4 or more days, (2) respondent tried to stop obsessions or compulsions, (3) upset/annoyed by obsessions or compulsions, and (4) obsessions lasting at least 15 min or compulsions performed at least three times. The total score is 8 (4 each for obsessions and compulsions). The algorithm to diagnose ICD-10OCD required symptoms of 2 weeks or longer, at least one thought or act resisted, and an overall score of 4 for obsessions or compulsions if accompanied by social impairment or a total score of at least 6 if not accompanied by social impairment.[31]

Previous studies have varied in their definition of subthreshold OCD, and to the best of our knowledge, there is no expert consensus or operational definition with regard to subthreshold OCD.[7,8,9,10,11,12] Hence, the authors, by consensus, defined subthreshold OCD as the presence of obsessions/compulsions for a minimum duration of 2 weeks with at least one act/thought resisted but otherwise not fulfilling the severity criteria for OCD as per the CIS-R.

The CIS-R has been validated for use in India and has been shown to have moderate validity and high reliability in comparison to ICD-10 diagnosis.[32,33,34]

As the CIS-R does not have a section for assessment of specific OCSs, five obsession categories (germs/contamination, harm, symmetry/order, saving concerns and obsessions pertaining to sexual/religious/morality, or other disturbing taboo thoughts) and five compulsions categories (washing/cleaning, checking, ordering/touching, saving, and mental rituals) were taken verbatim from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI).[35] In addition, those students who reported OCSs were asked to report the duration of their symptoms.

Substance use

For assessment of lifetime alcohol and tobacco use, the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) was used.[36] It is a brief screening questionnaire to find out about people's use of psychoactive substances. In the present survey, the ASSIST was modified to assess lifetime use of alcohol and tobacco only. Studies have shown that ASSIST has good test-retest reliability and high validity.[37]

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was assessed using the Kessler's Psychological Distress Scale (K10), a screening tool for nonspecific psychological distress over the past month.[38] The tool has been validated to screen for common mental disorders in developing country settings and has previously been used in India.[39] It consists of ten questions to elicit the frequency of depressive and anxiety symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale of frequency. This is used to generate a score (range: 10–50) with higher scores reflecting greater severity of symptoms.[38]

Assessment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Students were asked to rate their behavior for features of ADHD between the ages of 5 and 12 years using the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV – childhood symptoms self-report.[40] The scale consists of 18 questions – 9 of them for features of inattention and 9 questions for hyperactivity-impulsivity. Each question was rated in the form of Likert scale with four options. The total scores ranged from 18 to 72.[40]

Assessment of suicidality

Two questions requiring the participant to respond as yes/no were asked to assess lifetime suicidality: Have you thought of committing suicide ever in your life? Have you made a suicidal attempt in your lifetime?

Assessment of sexual abuse

Four questions modified from the ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool, Children's Version, an instrument which has been validated in India,[41] were asked with regard to lifetime exposure to sexual abuse. Questions asked were the following: (1) Has someone misbehaved with you sexually against your will? (2) Has someone forced you to look at pornographic materials against your will? (3) Has someone demanded or forced you to fondle or fondled you against your will? (4) Has someone forced you to a sexual relationship against your will? Participants were expected to tick “yes” or “no” response. Questions 1 and 2 concerned noncontact sexual abuse, and questions 3 and 4 were regarding contact sexual abuse.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 15[42] and EZR - version 1.29.[43] Point prevalence of OCD and subthreshold OCD was determined. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square/Fisher's exact tests, as necessary. Differences between means were compared using the ANOVA. A post hoc analysis was done with holm correction for categorical variables and Bonferroni correction for continuous variables to find which groups differed from each other. All tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 5784 students took part in the survey. Of the questionnaires, 858 (14.8%) questionnaires had to be discarded as they were incomplete and the rest (n = 4926) were analyzed. Of the 4926 questionnaires which were analyzed, 1752 (35.5%) were males and 3174 (64.5%) were females with a mean age of 20.3 years (range: 18–25 years). The prevalence of self-reported OCSs among our college students fulfilling ICD-10 criteria of OCD was 3.3% (CI: 2.8%–3.9%) (n = 164) (males = 3.5%, n = 61; females = 3.2% n = 103) with no gender difference in prevalence (P = 0.56). Further, 8.5% (CI: 7.7%–9.3%) (n = 418; males = 9.9%, n = 173; females = 7.7%, n = 245) of the students fulfilled criteria of subthreshold OCD with prevalence being significantly higher among males (P = 0.02).

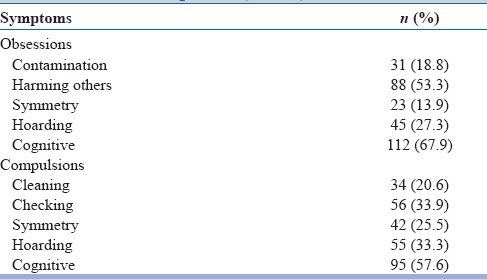

Forty-three (26.8%) subjects were ill between 2 weeks and 6 months, 36 (21.7%) for 6 months to 1 year, 35 (21.6%) for 1–2 years, and 48 (29.9%) for more than 2 years. The symptom profile of OCD subjects showed that taboo thoughts (67.1%) and mental rituals (57.4%) were the most common symptoms [Table 1].

Table 1.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder - symptom profile (n=164)

Students with OCD and subthreshold OCD were comparable with students without OCD with regard to sociodemographics except with regard to higher representation of males in the subthreshold OCD group compared to non-OCD groups (41.4% vs. 34.9%, P < 0.05).

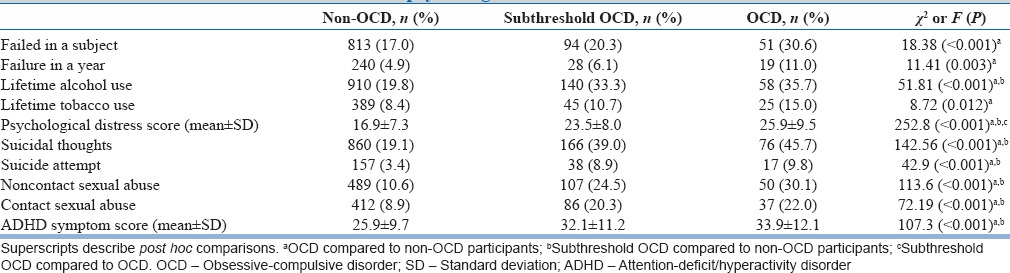

Table 2 describes the clinical correlates of OCD and subthreshold OCD. When compared with the non-OCD group, subjects with OCD were significantly more likely to have academic failures, lifetime alcohol and tobacco use, psychological distress, suicidal thoughts and attempts, history of sexual abuse, and higher ADHD symptom scores [Table 2]. When compared with the non-OCD group, subthreshold OCD subjects were significantly more likely to report lifetime alcohol use, psychological distress, suicidal thoughts and attempts, sexual abuse, and higher ADHD symptom scores [Table 2]. Those with OCD were comparable to the subthreshold OCD group except that OCD subjects had higher psychological distress scores [Table 2].

Table 2.

Correlates of obsessive-compulsive disorder/subthreshold obsessive-compulsive disorder with academic and psychological variables

DISCUSSION

The point prevalence rate of OCD and subthreshold OCD in our sample of college students was 3.3% and 8.5%, respectively. The prevalence rate of OCD and subthreshold OCD in our sample of college students is broadly comparable to the prevalence rates of 1.1%–3.3% for OCD[1,2,3,4,5,6] and 1.6%–12.6% for subthreshold OCD[7,8,9,14] reported in other epidemiological studies from across the world. However, when the current prevalence or annual prevalence of OCD alone is considered, it appears that our estimation of prevalence of OCD is sometimes higher than what has been reported in some epidemiological studies including the Cross National Collaborative Group (12-month prevalence ranging from 1.1% to 1.8%),[2] the British National Comorbidity Survey (1-month prevalence of 1.1%),[3] and the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (12-month prevalence of 1.2%).[4] Higher rates have also been reported in a Turkish study of university students (4.2%)[44] which estimated lifetime prevalence and in a Zurich prospective longitudinal study which reported an unweighted cumulative 1-year prevalence rate of 5.1%.[14]

There are only a few major studies which have reported the prevalence of subthreshold OCD, all of which have differed with regard to the definition of “subthresholdness.” In comparison to our finding of 8.5%, one study which defined subthreshold cases as having obsessions or compulsions plus at least one additional formal criterion, including the time and distress criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM)-IV reported a prevalence rate of 2%.[7] Other studies which have had less restrictive criteria with inclusion of all subjects with obsessions and/or compulsions (the DSM-III-R A criterion) who did not meet the full criteria for OCD reported rates between 4.9% and 12.6%;[9,11,12] and a prevalence rate of 8.7% was reported by a study which included subjects with OCSs according to DSM-IV with moderate distress.[8] Though our study findings support the assertion that the prevalence of OCD and subthreshold worldwide is somewhat similar, as noted, estimates vary based on the methodological approaches to assessment. Estimates derived from lay interviews may overestimate the prevalence of OCD relative to clinical interviews.[45,46] A higher rate in this study could be due to the fact that the survey was essentially based on a self-administered questionnaire with no follow-up diagnostic confirmation.

Our study found no gender differences in the prevalence of OCD, whereas major epidemiological studies have reported a slight female predominance[1,2,3] or equal prevalence.[47] The male predominance for subthreshold OCD has been reported previously.[7] Consistent with findings from community studies,[1,2,3] a higher proportion of our subjects with OCD reported obsessions.

Our subjects with OCD had higher academic failures indicating the occupational impairment which has been reported in many studies across the world.[4,9] Academic achievement for the subthreshold group was comparable to controls indicating lesser impairment. However, subjects with OCD and subthreshold OCD in our sample had higher psychological distress indicated by higher Kessler's psychological distress scale scores than the control group. Further, subjects with OCD had higher psychological distress than the subthreshold group indicating a higher distress with increasing severity of illness. Although a direct comparison may not be possible, a greater severity of Kessler's scores is correlated with a diagnosis of anxiety and depression as per CIDI.[39] Both clinical and epidemiological studies in OCD report high rates of comorbid depression and anxiety disorders.[3,4,9,17] Subjects with both OCD and subthreshold OCD had higher rates of suicidal thoughts and suicidal attempts in comparison to controls. The higher psychological distress in both these groups could have contributed to the higher rates of suicidality. The finding of higher suicidality in OCD subjects has been reported from both clinical and epidemiological studies[3,18,19] and from an epidemiological study in subthreshold OCD.[13]

Subjects with OCD in our study had higher rates of alcohol and tobacco use while those with subthreshold OCD had higher rates of alcohol use only. The high co-occurrence of alcohol use among OCD subjects (20%–40%) in epidemiological studies has been reported previously.[3,4] The rate of alcohol use in OCD (35.7%) and subthreshold OCD (33.7%) in our study is toward the higher end of comorbid prevalence rates reported from elsewhere the world. A high rate of comorbid alcohol use could be partly accounted by the high baseline prevalence rates of lifetime alcohol use in our sample (19.6%). While there have been consistent low reports of tobacco use among OCD subjects in prior studies,[3,21] tobacco use was significantly higher in our OCD subjects and not in subthreshold subjects indicating that in our sample, greater severity of illness was linked to tobacco use.

In our sample, higher ADHD symptoms scores were reported in our young adult subjects with both OCD and subthreshold OCD. The data with regard to the relationship between adult OCD and ADHD are inconsistent with most studies indicating no relationship.[24] However, a strong association of ADHD with OCD has been reported in clinical[23,24] and epidemiological samples[27] of children and adolescents suggesting that it could be a developmental marker for early-onset OCD. Our finding of a relationship in young adults presenting with OCD suggests that this relationship may extend to this age group, and young adults with OCD may also need to be screened for ADHD similar to children and adolescents presenting with OCD.

Subjects with OCD and subthreshold OCD had higher rates of exposure to contact and noncontact sexual abuse. The higher rates of sexual abuse have been reported in adults with OCD in a clinical sample.[25] Sexual abuse has long-term consequences including borderline personality disorder, eating disorder, somatization, and depression.[26] However, the evidence with regard to OCD is sparse. Two possibilities have been postulated with regard to the link between sexual abuse and OCD. One, abuse could have specific role in the expression of OCD or could represent a nonspecific contributory factor to the manifestation of OCD.[48,49] Both explanations are speculative, and this aspect needs to be studied further.

Overall, the study adds to the growing evidence that even subthreshold OCD is associated with significant morbidity.[11,12,13,14] The finding suggests that even those with obsessions and compulsions not fulfilling diagnostic criteria for OCD may have to be offered help to reduce morbidity. Our current preoccupation with syndromal diagnosis as per classificatory systems may exclude a significant proportion of people having obsessions and compulsions who are in need of care. There is, thus, a need for greater research and improved clinician awareness of subthreshold OCD.

The findings of our study should be evaluated in the context of its strengths and limitations. The diagnosis of OCD was based only on the self-reported responses of the students. No diagnostic interview was conducted to confirm the diagnosis. Therefore, an estimate of prevalence may be less than accurate. The cross-sectional design of the study precludes any conclusion on cause and effect with regard to OCD, subthreshold OCD, and the independent variables examined. The strengths of the study include a large representative sample of young adults from the state of Kerala. The prevalence of OCD and subthreshold OCD and its correlates have been examined for the first time in a community adult sample in India.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that OCD and subthreshold OCD are not uncommon in the Indian population. Those with OCD (and subthreshold OCD) have significant morbidity including suicidality. This finding has important public health implications. Mental health programs in our country often revolve around serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia ignoring common but disabling mental illnesses such as OCD. Mental health professionals and health planners in India need to develop mechanisms to diagnose and treat OCD early to prevent morbidity associated with it.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank all the staff at all participating colleges who provided administrative and logistic support for the research project, and Mr. Ajayakumar and the team who helped with data entry. We also thank all students who took part in this survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1094–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360042006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Lee CK, et al. The cross national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. The Cross National Collaborative Group. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(Suppl):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres AR, Prince MJ, Bebbington PE, Bhugra D, Brugha TS, Farrell M, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Prevalence, comorbidity, impact, and help-seeking in the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1978–85. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:53–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh A, Rahgozar M, Noorbala AA, Davidian H, Afzali HM, et al. Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in Iran. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Chong SA. Obsessive – Compulsive disorder: Prevalence, correlates, help-seeking and quality of life in a multiracial Asian population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:2035–43. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grabe HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, Rumpf HJ, Freyberger HJ, Dilling H, et al. Prevalence, quality of life and psychosocial function in obsessive-compulsive disorder and subclinical obsessive-compulsive disorder in northern Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;250:262–8. doi: 10.1007/s004060070017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angst J, Gamma A, Endrass J, Goodwin R, Ajdacic V, Eich D, et al. Obsessive-compulsive severity spectrum in the community: Prevalence, comorbidity, and course. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:156–64. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bruijn C, Beun S, de Graaf R, ten Have M, Denys D. Subthreshold symptoms and obsessive-compulsive disorder: Evaluating the diagnostic threshold. Psychol Med. 2010;40:989–97. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL. The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15:743–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Gloster AT, Lieb R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the community: 12-month prevalence, comorbidity and impairment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:339–49. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maina G, Albert U, Bogetto F, Ravizza L. Obsessive-compulsive syndromes in older adolescents. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100:447–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goracci A, Martinucci M, Kaperoni A, Fagiolini A, Sbaragli C, Corsi E, et al. Quality of life and subthreshold obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2007;19:357–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2007.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fineberg NA, Hengartner MP, Bergbaum C, Gale T, Rössler W, Angst J. Lifetime comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder and sub-threshold obsessive-compulsive symptomatology in the community: Impact, prevalence, socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17:188–96. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2013.777745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organisation. Projections of Mortality and Burden of Disease, 2004-2030. [Last accessed on 2016 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections/en/index.html .

- 16.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quarantini LC, Torres AR, Sampaio AS, Fossaluza V, Mathis MA, do Rosário MC, et al. Comorbid major depression in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:386–93. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamath P, Reddy YC, Kandavel T. Suicidal behavior in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1741–50. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernández de la Cruz L, Rydell M, Runeson B, D’Onofrio BM, Brander G, Rück C, et al. Suicide in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A population-based study of 36 788 Swedish patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.115. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.115. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riemann BC, McNally RJ, Cox WM. The comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder and alcoholism. J Anxiety Disord. 1992;6:105–10. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Degonda M, Wyss M, Angst J. The Zurich Study. XVIII. Obsessive-compulsive disorders and syndromes in the general population. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;243:16–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02191519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bejerot S, Humble M. Low prevalence of smoking among patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40:268–72. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaisoorya TS, Janardhan Reddy YC, Srinath S. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder?– Findings from an Indian study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;12:290–7. doi: 10.1007/s00787-003-0342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abramovitch A, Dar R, Mittelman A, Wilhelm S. Comorbidity between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder across the lifespan: A systematic and critical review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:245–62. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caspi A, Vishne T, Sasson Y, Gross R, Livne A, Zohar J. Relationship between childhood sexual abuse and obsessive-compulsive disorder: Case control study. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2008;45:177–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, daCosta GA, Akman D, Cassavia E. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16:101–18. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaisoorya TS, Janardhan Reddy YC, Thennarasu K, Beena KV, Beena M, Jose DC. An epidemological study of obsessive compulsive disorder in adolescents from India. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;61:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welkowitz LA, Struening EL, Pittman J, Guardino M, Welkowitz J. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid anxiety problems in a national anxiety screening sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14:471–82. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(00)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uher R, Heyman I, Mortimore C, Frampton I, Goodman R. Screening young people for obsessive compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:353–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis G, Pelosi AJ. Manual of the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) London: Institute of Psychiatry; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: A standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22:465–86. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K. The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel V, Pereira J, Coutinho L, Fernandes R, Fernandes J, Mann A. Poverty, psychological disorder and disability in primary care attenders in Goa, India. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:533–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.6.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jordanova V, Wickramesinghe C, Gerada C, Prince M. Validation of two survey diagnostic interviews among primary care attendees: A comparison of CIS-R and CIDI with SCAN ICD-10 diagnostic categories. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1013–24. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, et al. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:122–39. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO ASSIST Working Group. The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): Development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, Farrell M, Formigoni ML, Jittiwutikarn J, et al. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103:1039–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25:494–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel V, Araya R, Chowdhary N, King M, Kirkwood B, Nayak S, et al. Detecting common mental disorders in primary care in India: A comparison of five screening questionnaires. Psychol Med. 2008;38:221–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barkley RA. Barkley adult ADHD rating scale –IV (BAARS –IV): Childhood symptoms. New York: Guildford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zolotor AJ, Runyan DK, Dunne MP, Jain D, Péturs HR, Ramirez C, et al. ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool Children's Version (ICAST-C): Instrument development and multi-national pilot testing. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:833–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Inc. SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. Chicago: SPSS inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.R Development Core Team: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 15]. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoldascan E, Ozenli Y, Kutlu O, Topal K, Bozkurt AI. Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in Turkish university students and assessment of associated factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein MB, Forde DR, Anderson G, Walker JR. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the community: An epidemiologic survey with clinical reappraisal. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1120–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nestadt G, Samuels JF, Romanoski AJ, Folstein MF, McHugh PR. Obsessions and compulsions in the community. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89:219–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kolada JL, Bland RC, Newman SC. Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in Edmonton. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994;376:24–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders BE, Villeponteaux LA, Lipovsky JA, Kilpatrick DG, Veronen LJ. Child sexual assault as a risk factor for mental disorders among women. J Interpers Violence. 1992;7:189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khanna S, Rajendra PN, Channabasavanna SM. Life events and onset of obsessive compulsive disorder. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;34:305–9. doi: 10.1177/002076408803400408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]