Abstract

Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism are associated with glucose intolerance, calling into question the contribution of thyroid hormones (TH) on glucose regulation. TH analogues and derivatives may be effective treatment options for glucose intolerance and insulin resistance (IR), but their potential gluco-regulatory effects during conditions of impaired metabolism are not well described. To assess the effects of thyroxine (T4) on glucose intolerance in a model of insulin resistance, an oral glucose tolerance test (oGTT) was performed on three groups of rats (n=8): 1) lean, Long Evans Tokushima Otsuka (LETO), 2) obese, Otsuka Long Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF), and 3) OLETF + T4 (8.0 μg/100g BM/d × 5wks). T4 attenuated glucose intolerance by 15 % and decreased IR index (IRI) by 34% in T4-treated OLETF compared to untreated OLETF despite a 31% decrease in muscle GLUT4 mRNA expression. T4 increased the mRNA expressions of muscle monocarboxylate transporter 10 (MCT10), deiodinase type (DI2), sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), and uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) by 1.8-, 2.2-, 2.7-, and 1.4-fold, respectively, compared to OLETF. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and insulin receptor were not significantly altered suggesting that the improvements in glucose intolerance and IR were independent of enhanced insulin-mediated signaling. The results suggest that T4 treatment increased the influx of T4 in skeletal muscle and, with an increase of DI2, increased the availability of the biologically active T3 to up regulate key factors such SIRT1 and UCP2 involved in cellular metabolism and glucose homeostasis.

Keywords: Thyroxine, Glucose Intolerance, Insulin Resistant Rat, OLETF rat

Introduction

Thyroid hormones (TH) have a multitude of physiological effects related to thermogenesis, metabolism, heart rate, and body composition (Lin & Sun 2011, Araujo et al. 2008). Through the transcriptional regulation of specific genes, THs have critical roles in the maintenance of glucose homeostasis (Brenta. 2010, Villicev et al. 2007, Chidakel et al. 2005). However, evidence suggests that TH may induce non-genomic effects that contribute to cellular metabolism (Weitzel et al. 2001, Davis et al. 2003). While it’s clearly established that TH drive metabolism, there remains conflicting evidence in the literature on the mechanisms involved in the regulation of glucose homeostasis (Medina et al. 2011, Aguer & Harper 2012). Both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism have been associated with complications in insulin signaling and glucose intolerance, a paradox that is likely associated with differential effects of TH on various tissues (Brenta. 2010, Teixeira et al. 2012). Nonetheless the literature suggests that synergies among T3, glucose, and lipid metabolism exists (Lin & Sun 2011, Kim et al. 2002). Exogenous T3 induces insulin-stimulated glucose transport and glycolysis in the muscle (Moreno et al. 2011). Furthermore, T3 potentiates insulin signaling, insulin sensitivity, and an increase in insulin synthesis (Lin & Sun 2011). However, links among thyroid hormones, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance remain elusive.

In peripheral tissues, the genomic effects of TH occur after the intracellular transport of the predominate TH, thyroxine (T4), and its deiodination to triiodothyronine (T3), by either deiodinase type 1 (DI1) or type II (DI2). The activity of these enzymes predominately found in skeletal muscle regulates the availability of T3, and in turn, may indirectly regulate insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis. The binding of T3 to its nuclear thyroid hormone receptor, THrβ-1, induces an energetically expensive and relatively time-consuming, transcriptional signaling cascade (Bernal & Refetoff 1977,Weitzel et al. 2001, Müller et al. 2014, Chidakel et al. 2005). One of the genes activated in this process, uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2), may contribute to mitochondrial ATP production and to glucose homeostasis (Toda & Diano 2014). THs can also promote metabolic changes through non-genomic effects, which can be manifested within minutes (as opposed to the longer genomic effects) (Weitzel et al. 2001). These non-genomic actions are independent of nuclear uptake of TH and may involve plasma membrane, mitochondrial, or cytoplasm receptors that mediate transcriptional actions (Davis et al. 2003). The monocarboxylate transporters, MCT8 and MCT10, are specific for THs and facilitate their transport in and out of the cell (Müller et al. 2014). Specifically, MCT10 has wide tissue distribution and can rapidly transport T4, potentiating non-genomic effects (Van Der Deure et al. 2010).

Additionally, THs may also regulate sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a NAD+-dependent deacetylase, that is involved in glucose homeostasis and insulin secretion. Recent studies have demonstrated that increasing expression of SIRT1 improves insulin secretion and sensitivity, especially in insulin resistance conditions (Moynihan et al. 2005, Sun et al 2007). However, the direct effects of T4 on muscle SIRT1 during insulin resistance are not well defined. Furthermore, down regulation or knockdown of SIRT1 induces insulin resistance in cells and tissues (Sun et al. 2007). SIRT1 may also interact with the TH receptor, THrβ1, which suggests a non-coincidental relationship between SIRT1 and THs (Thakran et al. 2013).

Incongruences in the literature on the relationship between TH and glucose homeostasis during insulin resistance conditions exist. Furthermore, the simultaneous contributions of exogenous T4 on UCP2 and SIRT1 to improved glucose tolerance are not well defined. To address the effects of TH on glucose intolerance we chronically infused insulin resistant, Otsuka Long Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats with exogenous T4 (OLETF+T4).

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of both Kagawa Medical University (Kagawa, Japan) and the University of California Merced (Merced, CA).

Animals

Male lean (265 ± 7 g), strain-control Long Evans Tokushima Otsuka (LETO) rats and obese (356 ± 4 g) Otsuka Long Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokushima, Japan), both 9 weeks of age, were assigned to the following groups (n=8/group): 1) untreated LETO, 2) untreated OLETF, and 3) OLETF + T4 (8.0 μg/100g BM/d × 5 wk). Rats were housed in groups of two or three in a specific pathogen-free facility (at Kagawa Medical University, Japan) under controlled temperature (23°C) and humidity (55%) with a 12 hr light and dark cycle. Animals were provided water and food ad libitum.

T4 Administration

Osmotic minipumps (Alzet, model 2006, Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA) loaded with T4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 6.5 mM NaOH and 50% propylene glycol, were implanted subcutaneously, delivering a predefined dose (Klieverik et al. 2009).

Body Mass and Food Intake

Body mass (BM) and food intake were measured daily. Sum of cumulative changes in body mass (ΣΔBM) was determined as the sum of consecutive changes in mean daily BM. Changes in ΣΔBM were determined by comparing slopes of the liner regressions for each group.

Blood Pressure

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured weekly in conscious rats by tail-cuff plethysmorgraphy (BP-98A; Softron Co., Tokyo, Japan) (Rodriguez et al. 2012, Vázquez-Medina et al. 2013).

Rectal Temperature

Rectal temperature was measured weekly until the end of the study using a small animal warmer and thermometer (BWT-100A; Bio Research Center, Nagoya, Japan).

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

A week before the end of the study, all animals were fasted overnight (ca. 12 hr) and oGTTs performed as previously described (Rodriguez et al. 2012). The glucose area under the curve (AUC glucose) and insulin area under the curve (AUC insulin) were calculated by the trapezoidal method and used to calculate the insulin resistant index (IRI) as previously described (Habibi et al. 2008).

Dissections

At the end of the treatment, all animals were fasted overnight (ca. 12 hr) and tissues harvested the subsequent morning. Trunk blood was immediately collected in chilled vials containing 50mM EDTA and protease inhibitor cocktail. Samples were centrifuged (3000x g, 15 min, 4°C), plasma collected in cryovials, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. The heart, soleus muscle, and epididymal (epi) and retroperitoneal (retro) fat were rapidly dissected, weighed, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. All samples were stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Plasma Analysis

Plasma insulin was measured using a commercially available kit (Rat Insulin ELISA kit; Shibayagi, Gunma, Japan) (Rodriguez et al. 2012). Plasma concentrations of total T4, total T3, and serum concentrations of free T4 were determined using commercial radioimmunoassay (RIA) kits (Coat-A-Count kit; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA, USA). Plasma thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was determined with a commercially available rat ELISA kit (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH). Plasma glucose, triglycerides (TG), and nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) were measured as previously described (Rodriguez et al. 2012). All samples were analyzed in duplicate with percent coefficients of variability of <10%.

Real-time Quantitative PCR

The mRNA expressions of muscle DI1, DI2, GLUT4, MCT10, SIRT1, THrβ1, and UCP2 were quantified by real-time PCR as previously described (Martinez et al. 2016, Vázquez-Medina et al. 2013). Values were normalized for the expression of β-actin. Samples were run, with positive and negative controls, on a 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in a 20μL reaction containing: 10μl of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 6μL water, 0.5μL of each primer (20μmol L-1), and 3μL of cDNA (150ng of RNA sample) (Martinez et al. 2014, Vázquez-Medina et al. 2013). Relative quantity of mRNA levels was plotted as fold-increase compared with the control group levels using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Primer sequences used are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Quantification of Protein Expression by Western Blot

Muscle protein content was assessed by Western blot as previously described (Martinez et al. 2016, Rodriguez et al. 2012, Vázquez-Medina et al. 2013). Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against AMPKα (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), phospho-AMPKα (Thr172) (1:350, Cell Signaling Technology), insulin receptor-β (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-IGF-I receptor-β (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology), and Na+/K+-ATPase-α (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Membranes were washed and incubated with secondary antibodies IR Dye 680RD donkey anti-mouse, IR Dye 680 RD donkey anti- rabbit, or IR Dye 800CW donkey anti-rabbit (1:20000). Proteins were then visualized using the LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System and quantified with ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). In addition consistency in loading equivalent amounts of total protein was confirmed and normalized by correcting for the densitometry values of Ponceau S staining (Gilda & Gomes 2013).

Statistics

Means (±SE) were compared by ANOVA followed by Fisher’s protected least-significant difference post-hoc test and considered significant at P<0.05. Glucose tolerance was determined by comparing mean AUC values obtained from the oGTT. All statistical analyses were performed with the SYSTAT 11.0 software (SPSS, Richmond, CA).

Results

T4 did not alter food consumption or body composition

Daily food consumption and body mass, and end-of-study tissue masses were measured to assess the potential effects of infused T4 on body composition and food intake. Mean food intake was higher in OLETF than in LETO (27.6 ± 0.3 vs. 19.4 ± 0.3 g/d), but there was no significant treatment effect (27.4±0.4 g/d) (Figure 1A). BM increased by 25% in untreated OLETF compared to LETO, but T4 treatment had no significant effect (Figure 1B). While the slope for the ΣΔBM regression for LETO (3.0±0.13) was lesser than that for OLETF groups, no significant treatment-effect was observed (4.4 ± 0.19 vs. 4.1 ± 0.16) (Figure 1C). While relative heart and soleus masses were not different among the groups, the fat masses (epi and retro) were greater in the OLETF groups than LETO; however, T4 treatment had no additional effect (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Mean (±SE)(A) food consumption, (B) BM throughout the course of the study, and (C) cumulative change of BM of LETO, OLETF, and OLETF+T4. †, P<0.05 vs. LETO.

Table 1.

Relative masses (g/100g BM) of heart, soleus muscle, and epi and retro fat in LETO, OLETF, and OLETF+T4 after 5 wk treatment (n=8/group).

| LETO | OLETF | OLETF+T4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative heart mass | 0.38±0.03 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.29±0.01 |

| Relative soleus muscle mass | 0.05±0.008 | 0.03±0.001 | 0.03±0.002 |

| Relative epi fat mass | 0.94±0.06 | 1.4±0.09† | 1.4±0.11† |

| Relative retro fat mass | 1.3±0.07 | 3.1±0.17† | 2.8±0.18† |

P<0.05 vs. LETO

T4 did not alter SBP or core-body temperature

SBP was measured to determine if improvements in metabolic defects translated to improvements in arterial blood pressure. Mean SBP in obese OLETF increased by 15% compared to lean LETO (138 ± 2 vs. 117 ± 1 mm HG), and treatment with T4 had no additional effect (140 ± 2 mmHG). These results demonstrate the development of elevated arterial blood pressure in the insulin resistant phenotype, and the lack of improvement with the improved metabolic phenotype associated with the exogenous T4 infusion. Rectal temperatures were also measured to determine the potential thermogenic effects of infused T4. There were no consistent strain or treatment effects on core-body temperature suggesting that the T4-mediated cellular effects had none to minimal thermogenic impacts (Supplemental Figure 1).

T4 improved glucose intolerance and IRI

An oGTT was conducted to determine the benefits of T4 treatment on glucose intolerance and IRI during an insulin resistant condition. Mean AUCglucose increased by 55% in OLETF compared to LETO, and decreased 15 % in T4-treated OLETF (Figure 2A). Mean AUCinsulin increased by 68% in OLETF compared to LETO, and decreased 24% in T4-treated OLETF (Figure 2B). The IRI increased 86% in OLETF compared to LETO, and decreased 34% in T4-treated OLETF (Figure 2C). These results suggest that T4 improved glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and IRI in the OLETF rat.

Figure 2.

Mean (±SE) (A) blood glucose and (B) plasma insulin levels taken during an oral glucose tolerance test and corresponding area under the curve (AUC) and (C) insulin resistance index (IRI) of LETO, OLETF, and OLETF+T4. †, P<0.05 vs. LETO. #, P<0.05 vs. OLETF.

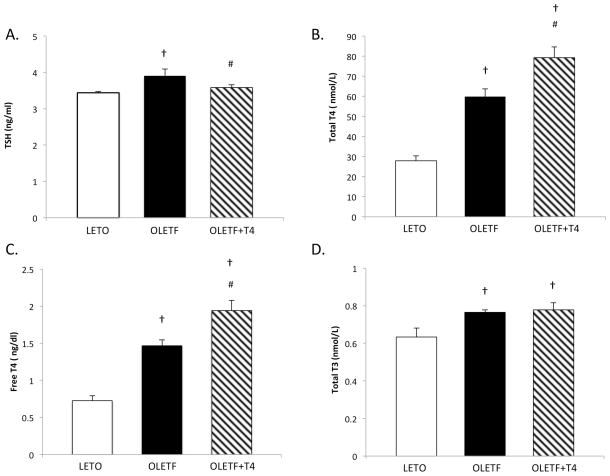

The obese, insulin resistant phenotype is associated with hyperthyroidism

TSH, total T4, free T4, and total T3 were measured to determine the thyroid hormone profile of the insulin resistant animals. TSH was 15% greater in OLETF compared to LETO, and was reduced 8% with T4 treatment (Figure 3A). The other thyroid hormones were consistently greater in OLETF compared to LETO (Figure 3B, 3C, 3D). In addition, fT4 and tT4 levels were exacerbated with the infusion of T4 as expected, confirming the successful infusion of exogenous T4. The elevated fT4 levels increase the availability of biologically active hormone to support the increase in DI2 for conversion to intracellular T3. To further demonstrate the cellular effectiveness of the T4 infusion, Na+-K+ ATPase protein expression, a sensitive marker of T4 activity, was measured. The protein expression of Na+-K+ ATPase increased nearly 3-fold in the treated OLETF group compared to its untreated counterpart (Figure 4). A 50% reduction in protein expression was associated with the obese OLETF compared to the lean LETO (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Mean (±SE) (A) TSH, (B) total T4, and (C) free T4 (fT4), and (D) total T3 measured in plasma of LETO, OLETF, and OLETF+T4. †, P<0.05 vs. LETO. #, P<0.05 vs. OLETF.

Figure 4.

Mean (±SE) percent change from LETO for Na+/K+ ATPase in soleus muscle of LETO, OLETF, and OLETF+T4 after 5 wk treatment and representative Western blot bands. †, P<0.05 vs. LETO. #, P<0.05 vs. OLETF.

T4 increases muscle mRNA expressions of MCT10, DI2, UCP2, and SIRT1

To assess the effects of T4 on the mRNA expressions of key regulators of TH-mediated signaling and metabolism in muscle, MCT10, DI1/2, THrβ1, UCP2, and SIRT1 were measured. Muscle MCT10 mRNA expression decreased over 50% in untreated OLETF compared to LETO, and levels were completely recovered with T4 (Figure 5A). While the decreases in DI2 with OLETF did not reach significance, DI1 levels were significantly reduced (Figure 5B, 5C) and DI2 levels nearly doubled with T4 (Figure 5C). No strain- or treatment-effect was detected in THrβ1 expression (Figure 5D). While no strain-effect in UCP2 and SIRT1 expression levels was detected, T4 increased levels 40% (Figure 5E) and 2.7-fold (Figure 5F), respectively.

Figure 5.

Mean (±SE) fold change of mRNA expression relative to LETO for (A) MCT10, (B) DI1, (C) DI2, (D) THRβ-1, (E) UCP2, and (F) SIRT 1 in soleus muscle of LETO, OELTF, and OLETF+T4 after 5 wk treatment. †, P<0.05 vs. LETO. #, P<0.05 vs. OLETF.

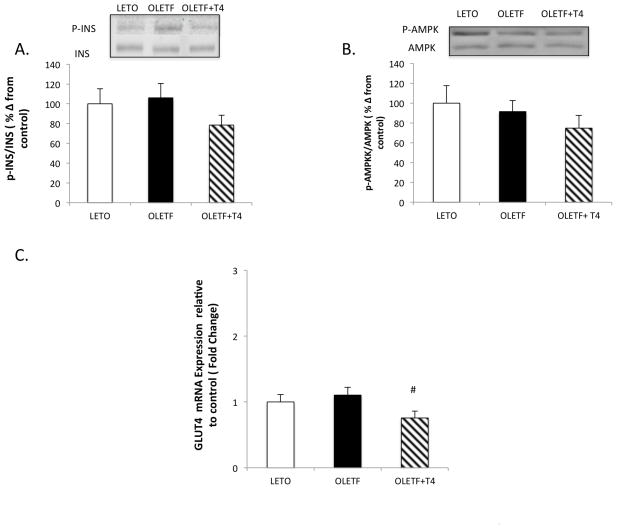

T4 improvements in IRI are independent in static changes in insulin signaling

The phosphorylation of AMPK and insulin receptor were measured to help determine the contributing factors to the improvements in glucose intolerance and IRI with T4 infusion. No profound changes in phosphorylation of insulin receptor or AMPK were detected (Figure 6A and 6B). While mean AMPK phosphorylation decreased 30% with T4 treatment, it did not reach significance (Figure 6B). GLUT4 mRNA expression did not exhibit a strain-effect, but T4 reduced levels by 31% (Figure 6C). Collectively, this data suggest that the improvements in glucose clearance and IRI are independent of static enhancements in insulin signaling and/or are the result of other, non-traditional signaling pathways that are associated with other glucose transporters.

Figure 6.

Mean (±SE) percent change from LETO for the ratios of (A) p-INS to INS (B) p-AMPK to AMPK including representative Western blot bands and (C) mean fold change of mRNA expression relative to LETO for GLUT 4 in soleus muscle of LETO, OLETF, and OLETF+T4 after 5 wk treatment. #, P<0.05 vs. OLETF.

T4 does not improve the strain-associated effect on lipid metabolism

Fasting plasma TG and NEFA were measured to assess the effects of T4 treatment on lipid metabolism. Fasting plasma TG (85±9 vs. 36±5 mg/dl) and NEFA (0.78±0.09 vs. 0.45±0.04 mEq/l) increased in OLETF compared with LETO. However, circulating lipids (79.1±11.0mg/dl and 0.67± 0.01mEq/l) were not significantly altered with T4.

Discussion

Hyper- and hypothyroidism are both associated with insulin resistance suggesting that thyroid hormones may have little if any effect on the regulation of glucose during insulin resistance. In the present study we investigated the role exogenous T4 has on glucose intolerance and insulin signaling in a model of insulin resistance. We demonstrated that the infusion of T4 significantly improved the insulin resistant condition and glucose intolerance in the insulin resistant OLETF rat.

Na+-K+ ATPase is a downstream target of T4 that is responsible for an electrochemical gradient that provides energy for the transport of many ions, metabolites, and nutrients such as glucose (Forst et al 2000). The up-regulation of Na+-K+ ATPase also imposes an energetic burden on cellular metabolism. Typically, diabetes-induced metabolic changes are also associated with alteration to the Na+-K+ ATPase activity. For example, impaired skeletal muscle glucose uptake in high fat diet, insulin resistant Wistar rats was associated with a reduction in Na+-K+ ATPase, and increased T3 increased its activity (Ho 2011, Lei et al. 2004). In the present study the muscle content of Na+-K+ ATPase was statically lower in the OLETF rat, and exogenous T4 more than completely recovered the suppressed protein content suggesting that the T4 infusion was effective at inducing a cellular response. Furthermore, the increase in muscle Na+-K+ ATPase likely contributed to the improvement in IRI in the T4-treated group by increasing cellular metabolism independent of insulin and AMPK signaling. Additionally, increased Na+-K+ ATPase activity is associated with increased SIRT1 (Yuan et al. 2014), similar to the relationship demonstrated in the present study. Thus, increasing cellular metabolism independent of enhanced insulin signaling may produce greater benefits on ameliorating obesity-associated insulin resistance than directly targeting insulin-mediated mechanisms.

The transport of T4 into the cell is required regardless if the cellular outcomes are genomic or non-genomic. While originally the transport of TH was thought to be passive, multiple membrane-bound transporters have been recently identified including MCT8 and MCT10 suggesting that TH-mediated effects may be regulated by the presence or up-regulation of these specific transporters. Thus, the concentration of thyroid hormone within the cell will determine the rate of cellular regulation of TH-mediated signaling (Van Der Deure et al. 2010, Visser 2010 ). In the present study, MCT10 was reduced and associated with elevated plasma levels of T4 in insulin resistant OLETF rats suggesting that the elevated plasma levels are attributed to reduced cellular transport, and consequently contribute to impairment of the HPT axis. Furthermore, the reduced MCT10 levels may also explain the decreasing trends in the mRNA expression levels of DI1 and DI2 as reduced availability of T4 for conversion to T3 reduces the demand for deiodinases. This is corroborated by reduced protein content of Na+-K+ ATPase, a surrogate marker of energetic demand and downstream target of TH signaling. Conversely, exogenous T4 reversed these strain-associated defects, and likely contributing to the improvements in glucose intolerance and IRI. The recovery of the MCT10 expression levels, while not associated with a decrease in plasma T4 due to the constant infusion, was associated with increased DI2 and Na+-K+ ATPase. Increased expression of the transporter should translate to a greater availability of T4 inside the cell, and with increased DI2 expression (and likely activity given the increase in fT4), there would be increased conversion to the more biologically active T3. This is supported by the complete recovery of muscle Na+-K+ ATPase.

With skeletal muscle accounting for about 40–50% of the total body mass, it’s the largest contributor to resting energy expenditure and insulin-induced glucose utilization (Marsili et al. 2010). Furthermore, DI2 has been shown to have a greater effect on T3-dependent gene transcription than D1 (Maia et al. 2005). Subjects with genetic defects to DI2 have reduced glucose turnover and DI2 knockout mice become insulin resistant (Hong et al. 2013, Maia et al. 2005). The present study would corroborate that further demonstrating that exogenous T4 is effective at restoring this insulin resistance-associated defect in DI1/2. In addition DI2 has been shown to provide a protective effect against diet-induced obesity associated glucose dysregulation (Marsili et al. 2011), which would explain the increase in mRNA of DI2 in our treated, diet-induced, obese insulin resistant OLETF rats. The increased mRNA expression of the transporter and DI2 can be linked with a higher availability of the T3 inside the cell in order to potentiate the increases of downstream targets that contributed to the improvement in glucose intolerance and insulin resistance.

In muscle, the genomic effects of T3 are mediated by its receptor, THrβ1. Furthermore, T3 can increase the expression of THrβ1, which may activate (phosphorylate) AMPK, a key regulator of cellular metabolism (Cantó & Auwerx 2013, Wang et al. 2014). When active, AMPK triggers the translocation of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane to increase the uptake of glucose (Cantó & Auwerx 2013). GLUT4 is an insulin-regulated protein that contributes to whole-body glucose homeostasis, and therefore is a key target for understanding insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (Teixeira et al. 2012). However, in this present study there was no detectable increase in the static activations of muscle insulin receptor or AMPK, and a reduction of mRNA expression of GLUT4 suggesting that the improvements in insulin resistance with infused T4 was independent of static enhancements in the traditional insulin-mediated signaling pathway. Alternatively, the improvements may have been accomplished through the contributions of other glucose transporters not measured here. The lack of an increase in THrβ1 would also suggest that the improvements in glucose tolerance were either mediated through: (1) non-genomic mechanisms such as increased cellular metabolism, and/or (2) genomic effects that did not necessitate static elevations in THrβ1 expression. That is, the increase in T4 transport (via increased MCT10) and deiodination (via increased DI2) in the T4 infused rats was likely sufficient to maintain the levels of THrβ1 expression to facilitate the increase in cellular metabolism that translated to improved glucose tolerance. Furthermore, T3 can rapidly increase glucose uptake independent of increased GLUT4 at the cell surface (Teixeira et al. 2012), thus the increase in DI2 likely increased the cellular levels of T3 to facilitate glucose uptake independent of GLUT4.

Sirt1, a downstream target of AMPK, is thought to be nutritionally regulated and low levels have been reported with high fat and hyperglycemic conditions (Brandon et al. 2015). AMPK typically regulates SIRT1 expression via NAD+ content; however, studies have shown that phosphorylation of AMPK had no effect on SIRT1 levels when knocked out or overexpressed. Furthermore, T3 stimulation enhanced the transcription of genes involved in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and gluconeogensis via up-regulation of SIRT1 (Brandon et al. 2015, Thakran et al. 2013). This is consistent with our findings that demonstrated a decrease in SIRT1 in OLETF rats that were completely recovered by the infusion of T4. Furthermore, the increase in muscle SIRT1 expression with T4 treatment was likely independent of AMPK activation. Thus, the improvements in insulin resistance in the treated group may be the result of non-TH-mediated genomic effects mediated in part by SIRT1. This is supported by a study demonstrating that SIRT1 can directly bind DNA bound transcription factors, including nuclear receptors, and influence transcription (Suh et al. 2013).

UCP2 is also a downstream target of THrβ1. Although the mechanisms describing UCP2 regulation of glucose metabolism is not well understood, an important link between the two is apparent. For example, subjects with a polymorphism in the transcription of UCP2 are associated with obesity and T2DM (Toda & Diano 2014). In addition, UCP2 increases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells (Toda & Diano 2014). The insulin resistance phenotype in OLETF is associated with an approximately 20% decrease in hepatic UCP2 protein content, which is more than completely restored with ARB treatment and associated with improved IRI (Montez et al. 2012). Similarly, the present study demonstrates a substantial increase in muscle UCP2 expression with infused T4 and an associated improvement in IRI suggesting that the maintenance and/or restoration of systemic UCP2 is an important factor in abating the manifestation and consequences of insulin resistance. Additionally, as with the current study, the previous improvements in IRI were independent of static improvements in the insulin signaling cascade suggesting that maintenance and/or restoration of UCP2 contributes to improvement in IRI independent of direct insulin-mediated signaling (Rodriguez et al. 2012). Furthermore, the observed improvements in glucose metabolism may be attributed to the up-regulation of UCP1 in brown adipose tissue (BAT). BAT in rodents has been shown to not only improve the control of thermogenesis, but glucose metabolism as well (Matsen et al. 2013). Furthermore, a human case study demonstrated that T4 treatment induced brown adipose tissue and ameliorated diabetes in a patient with extreme insulin resistance. This improvement was associated with an increase of UCP1 and DI2 in BAT (Skarulis et al. 2010).

A major concern of clinical hyperthyroidism is the deleterious effects associated with potential thyrotoxicosis (Araujo et al. 2008, Brenta. 2010, Villicev et al. 2007). Exogenous T4 treatment did not have any deleterious effects on the body composition, food consumption, excessive thermogenesis, and SBP suggesting that thyrotoxicosis was not a compounding factor. As expected, exogenous T4 administration decreased TSH levels and increased plasma T4, indicative of intact negative feedback mechanism and successful accomplishment of chronic elevation of circulating T4 with the infusion. The untreated OLETF was also characterized by relative hyperthyroidism with elevated triglycerides and non-esterified fatty acids suggesting that thyroid hormones do not profoundly improve the dyslipidemia associated with insulin resistance. Furthermore, the OLETF model presents with an impaired hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid negative feedback mechanism, as the nearly doubled T4 levels are associated with a 15% increase in circulating TSH. This impaired negative feedback is restored in the T4 infused rats. Additionally, hyperthyroid states may be associated with elevated plasma free fatty acids and glucose levels, which possibly contribute to the decrease in insulin sensitivity during this condition. However, it remains unclear if this condition is a cause or a consequence of insulin resistance in hyperthyroidism (Teixeira et al. 2012).

In conclusion, we found that exogenous T4 treatment improved glucose intolerance and insulin resistance via increased cellular metabolism. The increase in cellular metabolism was achieved by increases in the mRNA expressions of MCT10, DI2, SIRT1, and UCP2 that likely resulted in increased content of muscle Na+-K+ ATPase. The results suggest that T4 treatment increased the influx of T4 in skeletal muscle and, with an increase of DI2, increased the availability of the biologically active T3 to up regulate key factors such SIRT1 and UCP2 involved in cellular metabolism and glucose homeostasis. Furthermore, these changes in cellular events are largely suppressed in the obese, insulin resistant OLETF rat suggesting that these factors contribute to the manifestation of metabolic syndrome in this model. The ability of exogenous T4 to ameliorate this condition is independent of the phosphorylation (activation) of insulin receptor and AMPK, which combined translated into reduced expression of GLUT4. These results collectively suggest that impaired thyroid hormone regulation of key factors in cellular metabolism contributes to the glucoses intolerance associated with insulin resistance and ultimately the development of metabolic syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Mean (±SE) weekly rectal temperatures of LETO, OLETF, and OLETF+T4. Treatment began on week two.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health NHLBI R01HL091767. G V-A and B M were partially supported by 9T37MD001480 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

We thank Dr. K.R. Islam, Dr. Y. Takeshige, R. Rodriguez, Y. Sakane, and M. Thorwald for their assistance with conducting the study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Author Contributions

G V-A designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed the data, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the paper. B M performed experiments and provided guidance in the design of the study. J G S-O provided guidance in experimental design. D N and A N participated in the design of the study and made available facilities and resources. R M O designed the study, supervised the work, wrote the paper, and made available facilities and resources. All authors assisted in editing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

- Aguer C, Harper M-E. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: endocrine aspects. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2012;26:805–819. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo RL, de Andrade BM, de Figueiredo ÁSP, da Silva ML, Marassi MP, dos Pereira VS, Bouskela E, Carvalho DP. Low replacement doses of thyroxine during food restriction restores type 1 deiodinase activity in rats and promotes body protein loss. Journal of Endocrinology. 2008;198:119–125. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal J, Refetoff S. The action of thyroid hormone. Clinical Endocrinology. 1977;6:227–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1977.tb03319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon AE, Tid-ang J, Wright LE, Stuart E, Suryana E, Bentley N, Turner N, Cooney GJ, Ruderman B, Kraegen EW. Overexpression of SIRT1 in Rat Skeletal Muscle Does Not Alter Glucose Induced Insulin Resistance. 2015:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenta G. Diabetes and thyroid disorders. The British Journal of Diabetes & Vascular Disease. 2010;10(4):172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Cantó C, Auwerx J. Europe PMC Funders Group AMP-activated protein kinase and its downstream transcriptional pathways. 2013;67:3407–3423. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0454-z.AMP-activated. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidakel a, Mentuccia D, Celi FS. Peripheral metabolism of thyroid hormone and glucose homeostasis. Thyroid: Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2005;15:899–903. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis PJ, Davis FB. Diseases of the Thyroid. Humana Press; 2003. Nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Forst T, De La Tour DD, Kunt T, Pfützner A, Goitom K, Pohlmann T, Schneider S, Johansson BL, Wahren J, Löbig M, Engelbach M. Effects of proinsulin C-peptide on nitric oxide, microvascular blood flow and erythrocyte Na+, K+-ATPase activity in diabetes mellitus type I. Clinical Science. 2000;98(3):283–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilda JE, Gomes AV. Stain-Free total protein staining is a superior loading control to b-actin for Western blots. Analytical Biochemistry. 2013;440:186–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi J, Whaley-Connell A, Hayden MR, DeMarco VG, Schneider R, Sowers SD, Karuparthi P, Ferrario CM, Sowers JR. Renin inhibition attenuates insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and pancreatic remodeling in the transgenic Ren2 rat. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5643–5653. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K. A critically swift response: Insulin-stimulated potassium and glucose transport in Skeletal Muscle. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011;6:1513–1516. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04540511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong EG, Kim BW, Jung DY, Kim JH, Yu T, Da Silva WS, Friedline RH, Bianco SD, Seslar SP, Wakimoto H, et al. Cardiac expression of human type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase increases glucose metabolism and protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiac dysfunction in male mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3937–3946. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SR, Tull ES, Talbott EO, Vogt MT, Kuller LH. A hypothesis of synergism: the interrelationship of T 3 and insulin to disturbances in metabolic homeostasis. Medical hypotheses. 2002;59(6):660–666. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(02)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klieverik LP, Sauerwein HP, Ackermans MT, Boelen A, Kalsbeek A, Fliers E. Effects of thyrotoxicosis and selective hepatic autonomic denervation on hepatic glucose metabolism in rats. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;294:E513–E520. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00659.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klieverik LP, Coomans CP, Endert E, Sauerwein HP, Havekes LM, Voshol PJ, Rensen PCN, Romijn JA, Kalsbeek A, Fliers E. Thyroid hormone effects on whole-body energy homeostasis and tissue-specific fatty acid uptake in vivo. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5639–5648. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J, Mariash CN, Ingbar DH. 3, 3′, 5-Triiodo-l-thyronine up-regulation of Na,K-ATPase activity and cell surface expression in alveolar epithelial cells is Src kinase- and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:47589–47600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Sun Z. Thyroid hormone potentiates insulin signaling and attenuates hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;162:597–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia AL, Kim BW, Huang Sa, Harney JW, Larsen PR. Type 2 iodothyronine deioinase in the major source of plasme T3 in euthyroid humans. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115:1–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI25083.The. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsili A, Ramadan W, Harney JW, Mulcahey M, Castroneves LA, Goemann IM, Wajner SM, Huang SA, Zavacki AM, Maia AL, et al. Type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase levels are higher in slow-twitch than fast-twitch mouse skeletal muscle and are increased in hypothyroidism. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5952–5960. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsili A, Aguayo-Mazzucato C, Chen T, Kumar A, Chung M, Lunsford EP, Harney JW, van-Tran T, Gianetti E, Ramadan W, et al. Mice with a targeted deletion of the type 2 deiodinase are insulin resistant and susceptible to diet induced obesity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez B, Sonanez-Organis JG, Viscarra JA, Jaques JT, MacKenzie DS, Crocker DE, Ortiz RM. Glucose Delays the Insulin-induced Increase in Thyroid Hormone-mediated Signaling in Adipose of Prolong-Fasted Elephant Seal Pups. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2016;310(6):R502–R512. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsen ME, Thaler JP, Wisse BE, Guyenet SJ, Meek TH, Ogimoto K, Cubelo A, Fischer JD, Kaiyala KJ, Schwartz MW, et al. In uncontrolled diabetes, thyroid hormone and sympathetic activators induce thermogenesis without increasing glucose uptake in brown adipose tissue. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;304:E734–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00488.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina MC, Molina J, Gadea Y, Fachado A, Murillo M, Simovic G, Pileggi A, Hernandez A, Edlund H, Bianco AC. The thyroid hormone-inactivating type III deiodinase is expressed in mouse and human β-cells and its targeted inactivation impairs insulin secretion. Endocrinology. 2011;152:3717–3727. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M, Silvestri E, De Matteis R, de Lange P, Lombardi A, Glinni D, Senese R, Cioffi F, Salzano AM, Scaloni A, et al. 3,5-Diiodo-L-thyronine prevents high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance in rat skeletal muscle through metabolic and structural adaptations. FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011;25:3312–3324. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-181982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montez P, Vazquez-Medina JP, Rodriguez R, Thorwald MA, Viscarra JA, Lam L, Peti-Peterdi J, Nakano D, Nishiyama A, Ortiz RM. Angiotensin receptor blockade recovers hepatic UCP2 expression and aconitase and SDH activities and ameliorates hepatic oxidative damage in insulin resistant rats. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5746–5759. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan KA, Grimm AA, Plueger MM, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Ford E, Cras-Meneur C, Permutt MA, Imai SI. Increased dosage of mammalian Sir2 in pancreatic β cells enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mice. Cell Metabolism. 2005;2:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Mayerl S, Visser TJ, Darras VM, Boelen A, Frappart L, Mariotta L, Verrey F, Heuer H. Tissue-specific alterations in thyroid hormone homeostasis in combined Mct10 and Mct8 deficiency. Endocrinology. 2014;155:315–325. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R, Viscarra JA, Minas JN, Nakano D, Nishiyama A, Ortiz RM. Angiotensin receptor blockade increases pancreatic insulin secretion and decreases glucose intolerance during glucose supplementation in a model of metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1684–1695. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarulis MC, Celi FS, Mueller E, Zemskova M, Malek R, Hugendubler L, Cochran C, Solomon J, Chen C, Gorden P. Thyroid hormone induced brown adipose tissue and amelioration of diabetes in a patient with extreme insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95:256–262. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh JH, Sieglaff DH, Zhang A, Xia X, Cvoro A, Winnier GE, Webb P. SIRT1 is a Direct Coactivator of Thyroid Hormone Receptor β1 with Gene-Specific Actions. PLoS ONE. 2013:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Zhang F, Ge X, Yan T, Chen X, Shi X, Zhai Q. Article SIRT1 Improves Insulin Sensitivity under Insulin-Resistant Conditions by Repressing PTP1B. 2007:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira SS, Tamrakar AK, Goulart-Silva F, Serrano-Nascimento C, Klip A, Nunes MT. Triiodothyronine Acutely Stimulates Glucose Transport into L6 Muscle Cells Without Increasing Surface GLUT4, GLUT1, or GLUT3. Thyroid. 2012;22:747–754. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakran S, Sharma P, Attia RR, Hori RT, Deng X, Elam MB, Park Ea. Role of sirtuin 1 in the regulation of hepatic gene expression by thyroid hormone. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:807–818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.437970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda C, Diano S. Mitochondrial UCP2 in the central regulation of metabolism. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;28:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Deure WM, Peeters RP, Visser TJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone transporters, including MCT8, MCT10, and OATPs, and the effects of genetic variation in these transporters. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2010;44:1–11. doi: 10.1677/JME-09-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Medina JP, Popovich I, Thorwald Ma, Viscarra Ja, Rodriguez R, Sonanez-Organis JG, Lam L, Peti-Peterdi J, Nakano D, Nishiyama A, et al. Angiotensin receptor-mediated oxidative stress is associated with impaired cardiac redox signaling and mitochondrial function in insulin-resistant rats. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2013;305:H599–H607. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00101.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villicev CM, Freitas FRS, Aoki MS, Taffarel C, Scanlan TS, Moriscot AS, Ribeiro MO, Bianco AC, Gouveia CHA. Thyroid hormone receptor β-specific agonist GC-1 increases energy expenditure and prevents fat-mass accumulation in rats. Journal of Endocrinology. 2007;193:21–29. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.07066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser TJ. Cellular Uptake of Thyroid Hormones. 2010:14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, Wei D, Guan MP, Xue YM. Triiodothyronine regulates distribution of thyroid hormone receptors by activating AMP-activated protein kinase in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and induces uncoupling protein-1 expression. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2014;393:247–254. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzel JM, Radtke C, Seitz HJ. Two thyroid hormone-mediated gene expression patterns in vivo identified by cDNA expression arrays in rat. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:5148–5155. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.24.5148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Zhou QY, Liu D, Yu L, Zhan L, Li XJ, Peng HY, Zhang XL, Yuan XC. Advanced glycation end-products impair Na+/K+-ATPase activity in diabetic cardiomyopathy: Role of the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/sirtuin 1 pathway. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2014;41:127–133. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mean (±SE) weekly rectal temperatures of LETO, OLETF, and OLETF+T4. Treatment began on week two.