Abstract

The human leucine zipper protein (LZIP) is a basic leucine zipper transcription factor that is involved in leukocyte migration, tumor suppression, and endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated protein degradation. Although evidence suggests a diversity of roles for LZIP, its function is not fully understood, and the subcellular localization of LZIP is still controversial. We identified a novel isoform of LZIP and characterized its function in ligand-induced transactivation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in COS-7 and HeLa cells. A novel isoform of human LZIP designated as “sLZIP” contains a deleted putative transmembrane domain (amino acids 229–245) of LZIP and consists of 345 amino acids. LZIP and sLZIP were ubiquitously expressed in a variety of cell lines and tissues, with LZIP being much more common. sLZIP was mainly localized in the nucleus, whereas LZIP was located in the cytoplasm. Unlike LZIP, sLZIP was not involved in the chemokine-mediated signal pathway. sLZIP recruited histone deacetylases (HDACs) to the promoter region of the mouse mammary tumor virus luciferase reporter gene and enhanced the activities of HDACs, resulting in suppression of expression of the GR target genes. Our findings suggest that sLZIP functions as a negative regulator in glucocorticoid-induced transcriptional activation of GR by recruitment and activation of HDACs.

A novel isoform of human LZIP functions as a negative regulator in glucocorticoid-induced transactivation of the glucocorticoid receptor by recruitment and activation of histone deacetylases.

The human leucine zipper protein (LZIP) is a basic leucine zipper transcription factor of the cAMP response element binding protein/activating transcription factor gene family that contains a basic DNA-binding domain, a putative transmembrane domain, and a leucine zipper domain (1). The ubiquitously expressed human LZIP binds to canonical cAMP response element and regulates cell proliferation (2). LZIP is also known to function as a tumor suppressor (3) and as a factor for ER stress-associated protein degradation (1, 4). We have previously reported that human LZIP binds to CC chemokine receptor (CCR) 1 and is a positive regulator in CC chemokine leukotactin (Lkn)-1-induced cell migration (5). Recent studies have suggested that LZIP is involved in Tat-mediated transcription of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (6) and CCR2 expression (7). These results indicate that human LZIP probably functions as a cellular modulator as well as a transcription factor. Although evidence suggests a diverse array of roles for human LZIP, its function is not fully understood, and the subcellular localization of LZIP is still controversial.

Two members of the murine LZIP family, designated as “LZIP-1” and “LZIP-2,” have been identified (8). The mouse cDNA for LZIP-1 encodes a 379-amino acid residue protein, and LZIP-2 contains an additional 25 amino acids in the N-terminal region (8). However, isoforms of human LZIP have not been previously reported. Herein, we report identification of a novel isoform of human LZIP and partial characterization of the differential roles of two human LZIP isoforms. A novel isoform of human LZIP, designated as a “small LZIP” (sLZIP), consists of 354 amino acids that contain a deleted putative transmembrane domain (amino acid residues 229–245) of LZIP. Our results show that human sLZIP and LZIP are differentially localized and that sLZIP functions as a negative regulator in ligand-induced transcriptional activation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR).

GR, a member of the nuclear receptor family, is a ligand-dependent transcription factor that mediates the effects of glucocorticoids in diverse cellular processes, including homeostasis, stress response, and inflammation (9). Upon glucocorticoid binding, activated GR enters the nucleus where it acts as a ligand-activated transcriptional stimulator or repressor of primary response genes by binding to glucocorticoid-responsive elements (GREs) in the promoter regions of steroid-responsive genes (10). GR is able to recruit a modulator of corepressors and coactivators, which, in turn, modify its transactivational activity (11). At present, several GR-interacting proteins have been identified that can alter the transcriptional efficiency of GR (12). Hormone-activated GR can affect transcription by a direct protein-protein interaction with other transcription factors and accessory proteins (13). It has been reported that glucocorticoids induce down-regulation of GR (14), and this regulation occurs at both the mRNA and protein levels (15).

Corepressors, including the nuclear receptor corepressors and the silencing mediators for retinoid receptor and thyroid hormone receptor, and associated histone deacetylases (HDACs), cause deacetylation of histones resulting in silencing gene transcription by preventing access of cis-acting molecules to the promoter region (16). Histone acetylation is a dynamic process that occurs on actively transcribed chromatin (11). The acetylation of histone that is associated with the increased expression of inflammatory genes is counteracted by the activities of HDACs, 11 of which deacetylated histones have been identified in mammalian cells (17, 18). There is evidence that the different HDACs target different patterns of acetylation and, therefore, regulate different types of gene expression (19). HDAC inhibitors induce specific changes in gene expression that influence a variety of other processes, including growth arrest, differentiation, cytotoxicity, and induction of apoptosis (17). It has been reported that sodium butyrate, an HDAC inhibitor, interferes with GR-activated transcription (20). However, the roles of HDACs in GR-mediated mechanisms are still obscure.

We characterized the regulatory role of sLZIP in ligand-induced transactivation of GR. Our findings indicate that sLZIP serves as a negative regulator of GR by recruiting HDACs and suppressing GR transactivation in response to glucocorticoids.

Results

Identification of a novel isoform of human LZIP

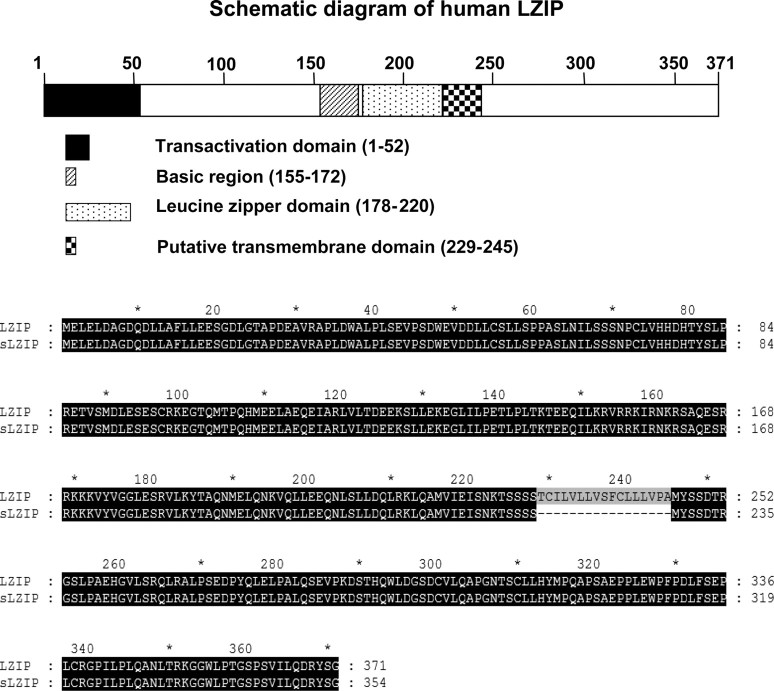

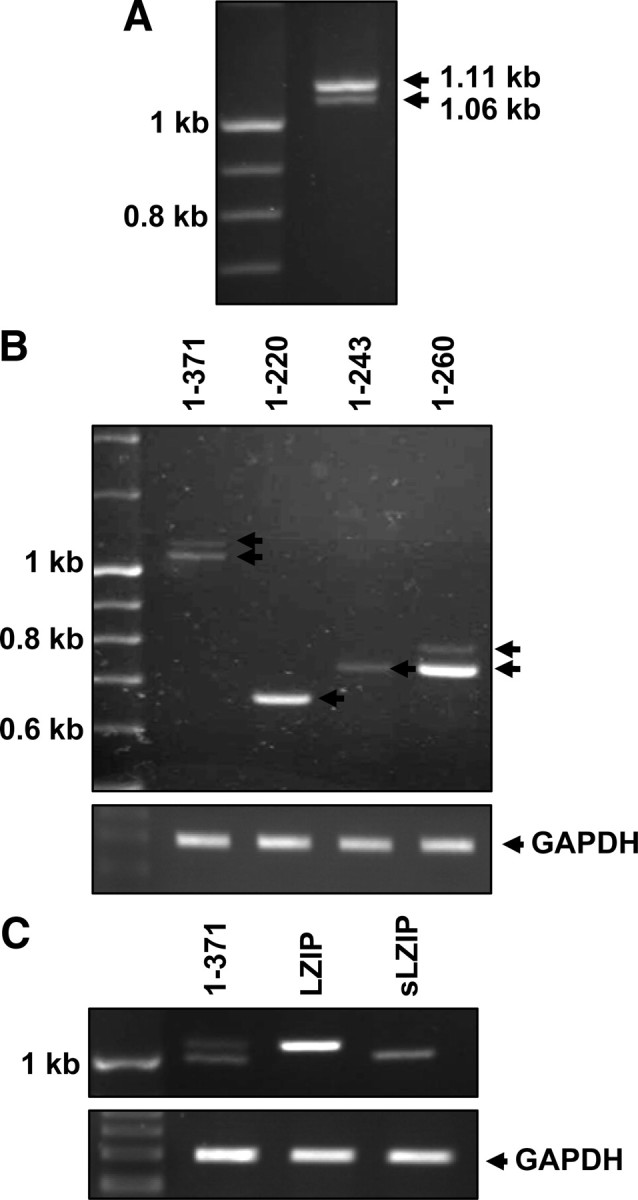

The human LZIP gene is located on chromosome 9p and is composed of nine exons that encode a 371-amino acid polypeptide and eight introns (21). LZIP shows a high degree of sequence conservation in evolution, with more than 70% amino acid sequence homology to mouse, fruit fly, and nematode sequences (3, 8, 22). Transcription factors that are involved in transcription machinery often consist of several types of isoforms that have different roles in cellular processes. Two members of murine LZIP, designated as “LZIP-1” and “LZIP-2,” have been identified (8). However, isoforms of human LZIP have not been reported. We identified two different sizes of human LZIP when we performed RT-PCR to determine LZIP expression in THP-1 monocytic cells (Fig. 1A). Our result indicates that human LZIP probably has a variant type. To confirm the existence of a variant of human LZIP, we conducted RT-PCR using various primers to distinguish between different sizes of possible LZIP isoforms. Results showed that the amino acids in the 220–260 region were responsible for the size difference between the two forms of human LZIP (Fig. 1B). This region contains a putative transmembrane domain (amino acids 229–245). We cloned the two forms of LZIP amplimers into the pcDNA3.1/V5-His expression vector and confirmed two different forms of human LZIP using PCR (Fig. 1C). Sequence analysis of the two LZIP clones shows that LZIP exhibits a large band that represents 371 amino acids and a smaller band that is newly identified herein as a human LZIP isoform represents only 345 amino acids (Fig. 2). The putative transmembrane domain (amino acids 229–245) is deleted in the small LZIP isoform (Fig. 2). The smaller LZIP is here designated as a small LZIP (sLZIP). The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper will appear in the GenBank under accession no. FJ263669.

Fig. 1.

Identification of a novel variant of human LZIP. A, Total RNA was extracted from THP-1 cells, and RT-PCR analysis was performed using primers specific for full-length human LZIP. The PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel. Arrows indicate two different PCR products of human LZIP. B, cDNA prepared from THP-1 cells was subjected to PCR to amplify different regions of human LZIP. Primers specific for amino acids 1–371, amino acids 1–220, amino acids 1–243, and amino acids 1–260 were used. C, Two LZIP variants were purified and subcloned into pcDNA3.1/V5-His vector. The cloning of each variant was confirmed by digestion of recombinant plasmids with BamHI and XhoI.

Fig. 2.

Nucleotide sequences of cDNAs encoding LZIP and sLZIP. Schematic diagrams of human LZIP with highlighting structurally distinct regions. Transactivation domain (1–52, ▪), basic region (155–172,  ), leucine zipper domain (178–220,

), leucine zipper domain (178–220,  ), putative transmembrane domain (229–245, checkered square). Cloned human LZIP isoforms were sequenced. Large LZIP isoform (LZIP) was the same as previously reported human LZIP, which contains a coding region of 1113 bp, encoding a protein of 371 amino acids. Small LZIP isoform (sLZIP) contains 1062-bp coding region, encoding a protein of 354 amino acids. sLZIP lacks the transmembrane domain (amino acids 229–245) of LZIP.

), putative transmembrane domain (229–245, checkered square). Cloned human LZIP isoforms were sequenced. Large LZIP isoform (LZIP) was the same as previously reported human LZIP, which contains a coding region of 1113 bp, encoding a protein of 371 amino acids. Small LZIP isoform (sLZIP) contains 1062-bp coding region, encoding a protein of 354 amino acids. sLZIP lacks the transmembrane domain (amino acids 229–245) of LZIP.

Different subcellular localizations of human LZIP isoforms

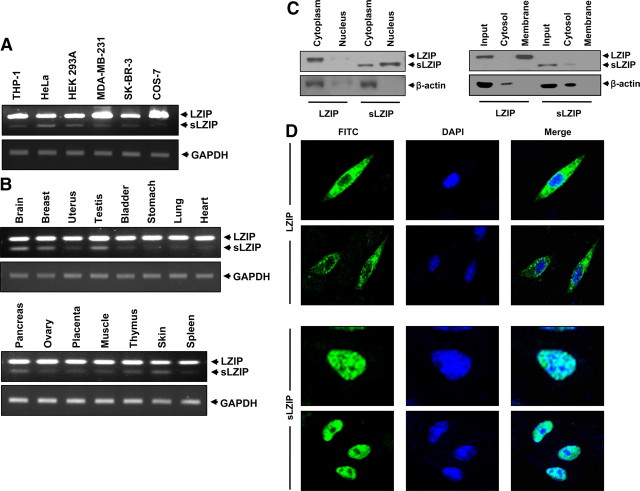

We examined the endogenous mRNA expression levels of LZIP and sLZIP in various cell lines and human tissues using semiquantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, both LZIP and sLZIP were ubiquitously expressed in all cell lines and tissues examined, with LZIP being much more common. Because the subcellular localization of proteins provides important information for understanding their cellular functions and the transmembrane domain affects the localization of proteins, we investigated the subcellular localizations of the two LZIP isoforms. After subcloning both isoforms into the pcDNA3.1/V5-His vector, we transiently transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293A cells with LZIP and sLZIP. The expressions of LZIP and sLZIP were confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis. Cell lysates were fractionated into the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, and the cytoplasmic fractions were further fractionated into the cytosol and membrane fractions. Results from Western blot analysis demonstrated that LZIP was located in the cytosol, particularly in the membrane fraction, and not found in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 3C). However, sLZIP was mainly located in the nucleus and partially in the cytosol, and sLZIP was not found in the membrane fraction (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that the two LZIP isoforms probably have different functions. We also visualized the localizations of the two isoforms using confocal microscopy. HeLa cells were transfected with LZIP and sLZIP and examined under a microscope. As consistent with cell fractionation results, LZIP was observed almost exclusively in the cytoplasm, and sLZIP was located predominantly in the nucleus (Fig. 3D). Taken together, sLZIP is a novel isoform of human LZIP, and the two isoforms have different subcellular localizations and may have different functions.

Fig. 3.

The expressions and subcellular localizations of LZIP isoforms. The mRNA expression levels of LZIP isoforms were examined by semiquantitative RT-PCR using mRNA obtained from six different cell lines (A) and 15 different human tissues (B). The PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels. The analysis was repeated three times, and GAPDH was used as an internal control. C, HEK 293A cells were transfected with 2 μg LZIP or sLZIP expression plasmids. After 24 h, cells were harvested and fractionated into the cytoplasm and nucleus (left panel). The cytoplasm was further fractionated into the cytosol and membranes (right panel). Samples were then separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and subjected to Western blotting with anti-sLZIP antibody. The analysis was repeated three times, and β-actin was used as an internal control. D, HeLa cells were transfected with sLZIP and LZIP. After 24 h, the cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, incubated with polyclonal anti-sLZIP antibody for 1 h, and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antirabbit antibody for 1 h. The preparations were washed and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma). Representative laser-scanning confocal micrographs demonstrating the distribution of sLZIP and LZIP are shown.

sLZIP is not involved in Lkn-1-induced cell migration

We previously reported that LZIP binds to CCR1 and participates in regulation of Lkn-1-induced chemotaxis signaling (5, 21, 23). To investigate the role of sLZIP, we determined whether sLZIP is involved in Lkn-1-induced cell migration. Stable human osteogenic sarcoma cells expressing CCR1 (HOS/CCR1) cells were transfected with mock, LZIP, and sLZIP plasmids, and a chemotaxis assay was performed in the presence and absence of 100 ng/ml of Lkn-1. The chemotactic activity of LZIP-transfected HOS/CCR1 cells was increased approximately 2.5-fold compared with vector-transfected cells. However, sLZIP did not affect the chemoattractant effect of Lkn-1 (data not shown). These results indicate that sLZIP is not involved in Lkn-1-induced chemotaxis signaling and probably has a unique function in the nucleus.

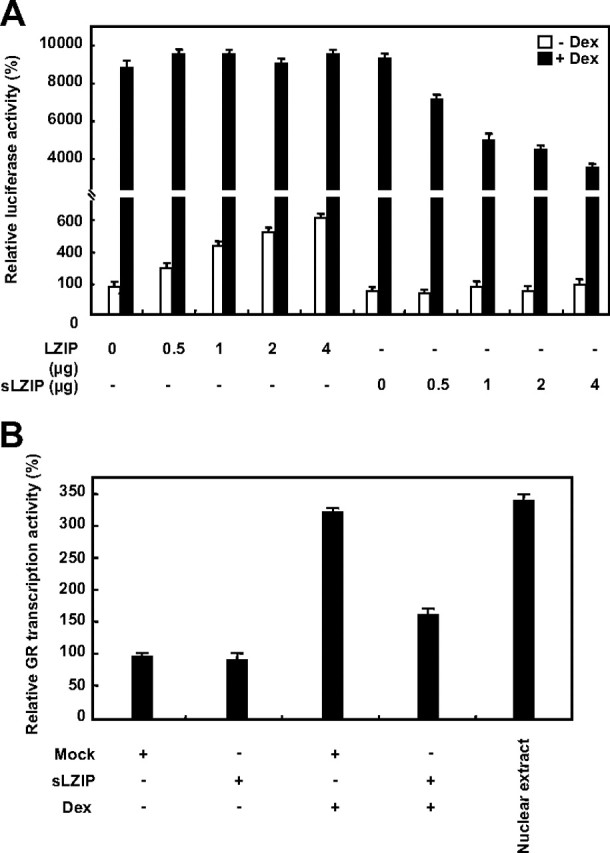

sLZIP decreases the transcriptional activity of GR

Many transcriptional coactivators contain LxxLL motifs and interact with other transcription factors such as nuclear hormone receptors; thus the LxxLL motif is known as a nuclear receptor recognition motif (24, 25). Human LZIP contains two LxxLL motifs; however, its interaction partners are not known. We investigated whether sLZIP interacts with nuclear receptors and is involved in transcriptional activation of the nuclear receptors. Among the known nuclear receptors, we focused on the relationship between sLZIP and GR in this study because LZIP is known to be involved in inflammatory responses. GR is an important intermediary transcription factor for the antiinflammatory responses of steroid hormone glucocorticoids and regulates the expression of a variety of target genes that harbor GRE in their promoter (12). We first examined protein-protein interaction between sLZIP and GR. sLZIP did not directly bind to GR, as demonstrated by immunoprecipitation analysis (data not shown). To examine whether sLZIP affects the ligand-induced transcriptional activation of GR, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with various amounts of sLZIP expression plasmids and a GRE-containing mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter reporter gene, which has been known to be regulated by GR. Transfected cells were stimulated with or without dexamethasone (Dex), and the GR transactivation was determined using a luciferase assay. Dex increased the luciferase activity by 80-fold in cells transfected with the MMTV reporter gene alone (Fig. 4A). In cells stimulated with Dex, sLZIP decreased the luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Cells transfected with 4 μg of sLZIP decreased the GR transcriptional activity approximately by 2.1-fold in response to Dex compared with cells transfected with the mock vector alone (Fig. 4A). However, the effect of LZIP on the MMTV luciferase activity was minimal (Fig. 4A). In the absence of Dex, sLZIP did not affect the GR transcriptional activity; however, LZIP slightly increased the luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). We next examined whether sLZIP affects the transcriptional activity of endogenous GR using an ELISA-based GR transcription factor assay kit. After HeLa cells were transfected with the mock vector and sLZIP, nuclear extracts were prepared. The GR transcription activity was then measured in the presence and absence of Dex. Dex increased the transcriptional activity of GR by 3.3-fold in cells transfected with the mock vector alone, whereas in cells transfected with sLZIP, the Dex-induced transcriptional activity of GR was decreased by 2-fold compared with cells transfected with the mock vector (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that sLZIP negatively regulates the glucocorticoid-induced transcriptional activation of GR.

Fig. 4.

sLZIP decreases the ligand-induced transcriptional activation of GR. A, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with GR, MMTV-Luc, and β-galactosidase in the presence and absence of LZIP or sLZIP as indicated. Cells were incubated with or without 100 nm Dex for 6 h and harvested for the luciferase assays. The luciferase activity was normalized by β-galactosidase activity, and the experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± sd and are presented as the relative luciferase activity. B, HeLa cells were transfected with the mock and sLZIP expression vectors (2 μg). Cells were treated with or without 100 nm Dex, and the nuclear extracts were prepared. The transcriptional activity of GR was assayed using an ELISA-based GR transcription factor assay kit as described in Materials and Methods. Dex-treated HeLa nuclear extract included in the assay kit was used as a positive control. The assays were performed in triplicate.

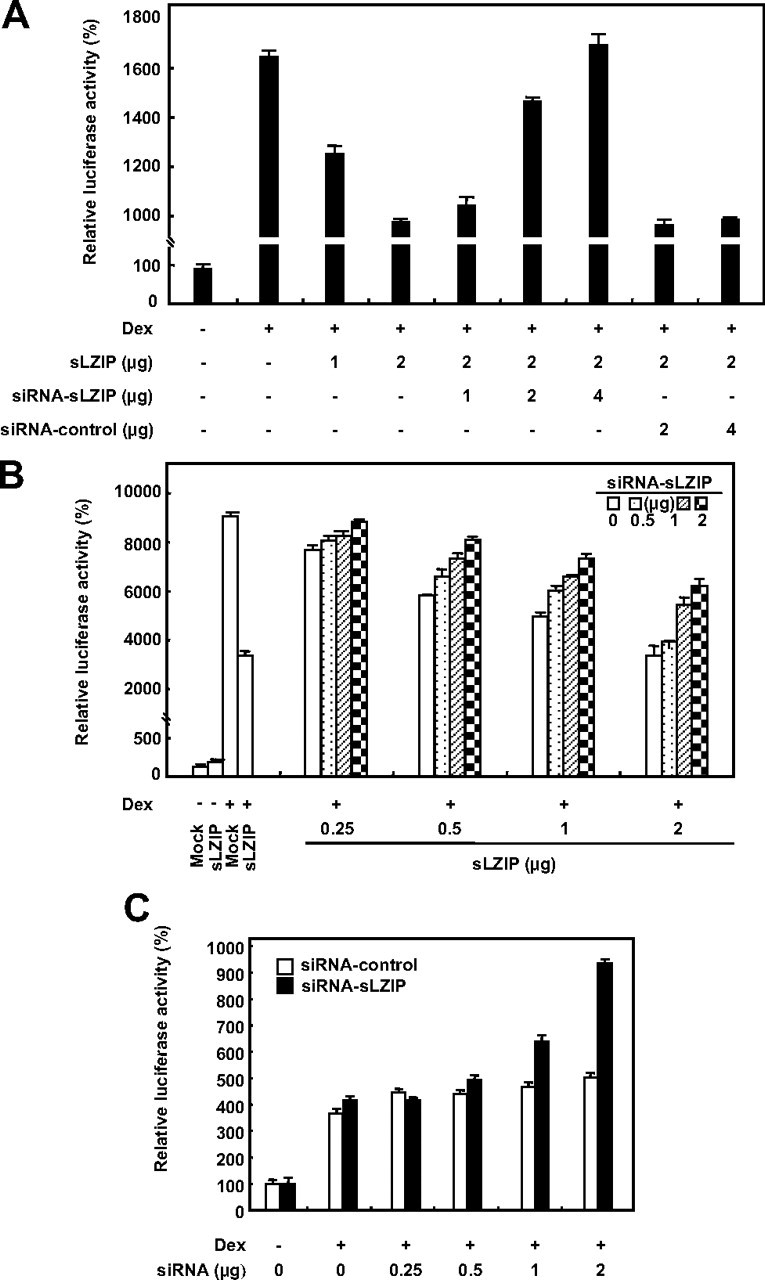

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-sLZIP abolishes the negative regulatory effect of sLZIP on the transcriptional activity of GR

We examined the effect of siRNA-sLZIP (siLZIP) on the glucocorticoid-induced transactivation of GR. We generated siRNA for sLZIP that reduced the expression of sLZIP to approximately 50% of the endogenous level (data not shown). Dex induced the GR transcriptional activity in cells transfected with the MMTV reporter gene alone (Fig. 5A). GR transactivation was decreased in response to Dex in cells transfected with sLZIP (Fig. 5A). However, in cells cotransfected with sLZIP and siLZIP, siLZIP abrogated the negative effect of sLZIP on the glucocorticoid-induced transactivation of GR in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). Cells containing 2 μg of sLZIP exhibited up to a 55% decrease in the GR transcription activity compared with cells transfected with the MMTV reporter gene alone (Fig. 5A). However, addition of 4 μg of siLZIP to these cells restored the GR transcription activity to the control level (Fig. 5A). We also examined the effects of siLZIP in cells containing exogenously expressed sLZIP at various concentrations. sLZIP and siLZIP expression plasmids were cotransfected with the MMTV reporter gene into COS-7 cells, and the luciferase activities were determined. The GR transcription activities of cells transfected with sLZIP were decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). However, siLZIP efficiently inhibited the negative effects of sLZIP on the glucocorticoid-induced transactivation of GR in cells containing various concentrations of sLZIP (Fig. 5B). To examine the function of endogenous sLZIP in GR transactivation, we performed the luciferase assay using siLZIP in HeLa cells that express endogenous sLZIP and GR. Results show that siLZIP increased the transcriptional activity of endogenous GR in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 5C). However, scrambled siRNA did not affect the GR transactivation (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that sLZIP specifically functions as a negative regulator of the glucocorticoid-induced GR transactivation pathway that is triggered by Dex.

Fig. 5.

siRNA-sLZIP abolishes the negative regulatory effect of sLZIP on the transcriptional activation of GR. A, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with the GR expression plasmid (0.5 μg), the MMTV-Luc reporter gene plasmid (0.25 μg), and the indicated amounts of sLZIP expression plasmid in the presence and absence of the indicated amounts of siLZIP expression plasmid. Cells were treated with or without 100 nm Dex for 6 h and harvested for the luciferase assays. B, COS-7 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of sLZIP and siLZIP in the presence of the GR expression plasmid (0.5 μg) and the MMTV-Luc reporter gene plasmid (0.25 μg). The luciferase activity was determined after the treatment with 100 nm Dex for 6 h. C, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of scrambled siRNA and siLZIP and the MMTV-Luc reporter gene plasmid (0.25 μg). The luciferase activity was determined after the treatment with 100 nm Dex for 6 h. The luciferase activity was normalized by β-galactosidase activity, and the experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± sd and are presented as the relative luciferase activity.

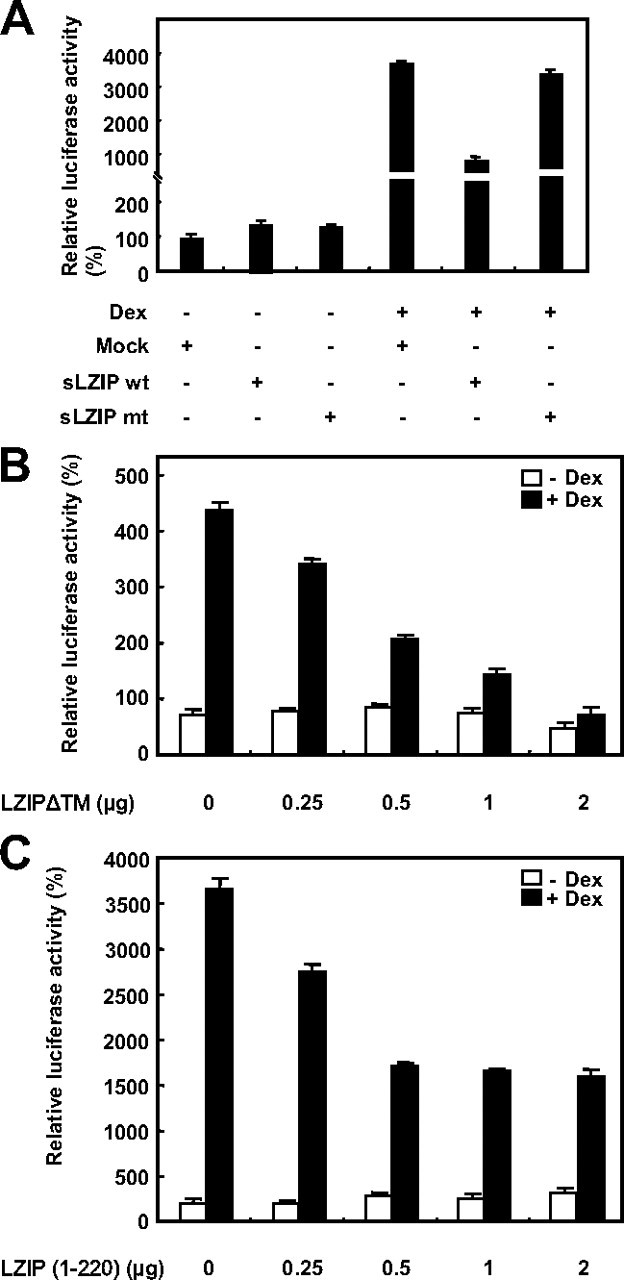

Although sLZIP did not directly bind to GR, we investigated involvement of the LxxLL motifs of sLZIP in binding other cofactors and regulation of GR transactivation. We constructed a mutant form of sLZIP so that two LxxLL motifs were mutated to LxxAA to disable the receptor interactions. Results showed that the mutant sLZIP did not affect the transcriptional activation of GR (Fig. 6A). This result indicates that the LxxLL motifs of sLZIP play an important role in binding to cofactors and regulation of GR transactivation.

Fig. 6.

The LxxLL motifs of sLZIP are critical for negative regulation of GR transactivation. A, COS-7 cells were transfected with the mock, sLZIP (wt), and sLZIP mutant (mt) expression vectors (2 μg) together with the expression vectors for GR (1 μg), MMTV-Luc (0.5 μg), and β-galactosidase (0.02 μg). Cells were treated with or without 100 nm Dex for 6 h and harvested for the luciferase assays. COS-7 cells were transfected with the GR expression plasmid (0.5 μg), the MMTV-Luc reporter gene plasmid (0.25 μg), and the indicated amounts of LZIPΔTM (B) and LZIP (1–220) (C) expression plasmids. Cells were treated with or without 100 nm Dex for 6 h and harvested for the luciferase assays. The luciferase activity was normalized by β-galactosidase activity, and the experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± sd and are presented as the relative luciferase activity. wt, Wild type.

Previous reports suggest that the location of LZIP is ER membrane and a mutant form of LZIP missing putative transmembrane domain (amino acids 229–243, LZIPΔTM) and a deletion mutant form of LZIP (amino acids 1–220) is localized in the nucleus (1, 26). To examine the effects of mislocalized LZIP on GR transactivation, we constructed a mislocalized mutant form of LZIP missing putative transmembrane domain (amino acids 229–243, LZIPΔTM) and a deletion mutant form of LZIP (amino acids 1–220). Results from the luciferase assays showed that the mislocalized LZIP mutants effectively inhibited the transcriptional activation of GR in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that the location of LZIP is critical for regulation of GR transactivation (Fig. 6, B and C).

sLZIP decreases the GR transcriptional activity by recruiting and activating HDACs

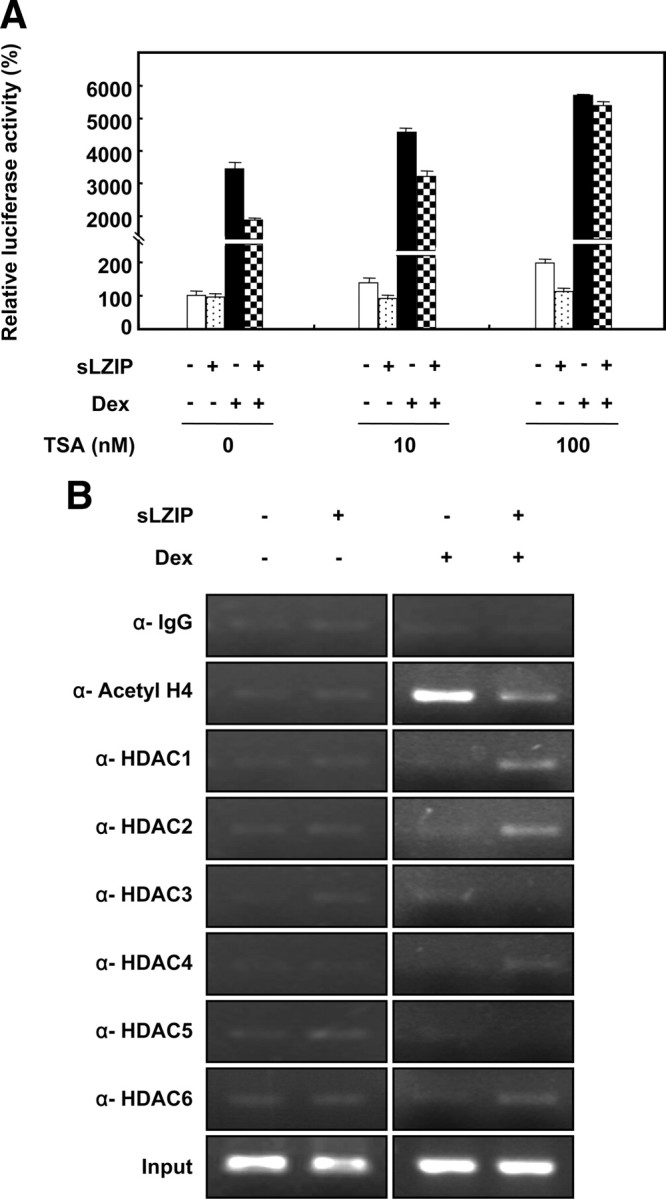

It has been reported that corepressors recruit HDACs, resulting in a decrease in the transactivation of GR in response to glucocorticoids (27). Because sLZIP decreased the transcriptional activity of GR in response to glucocorticoids, we examined whether HDACs are involved in repression of the GR transactivation by sLZIP using the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin (TSA). COS-7 cells were cotransfected with the GR expression plasmid and the MMTV reporter gene and then treated with TSA. In the absence of TSA, cells transfected with sLZIP exhibited up to a 47% decrease in the GR transcription activity compared with cells transfected with the MMTV reporter gene alone in response to Dex (Fig. 7A). However, treatment with 10 mm and 100 mm TSA decreased the GR transcription activity up to 33% and 6%, respectively (Fig. 7A). These results indicate that TSA abrogated the negative effect of sLZIP on GR transactivation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A), suggesting that sLZIP negatively regulates the glucocorticoid-induced transactivation of GR via histone deacetylation. We next examined which HDACs are involved in sLZIP-mediated transcriptional repression of GR by using ChIP assays. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with the GR expression plasmid and the MMTV reporter gene with or without sLZIP expression plasmid. ChIP assays were then performed with antibodies against HDAC1, -2, -3, -4, -5, and -6 in the presence and absence of Dex. In cells transfected with the mock vector only, HDACs were not attracted to the MMTV GREs regardless of the Dex treatment (Fig. 7B). However, in cells transfected with sLZIP, HDAC1, -2, and -6 were attracted to GREs in response to Dex, whereas HDACs were not coprecipitated with GREs without the Dex treatment (Fig. 7B). Also, sLZIP significantly decreased the acetylation level of histone 4 used as a positive control (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that specific HDAC proteins, including HDAC1, -2, and -6, were recruited to the MMTV GRE in cells expressing sLZIP. Our findings suggest that sLZIP probably recruits specific HDACs and activates HDAC activities to deacetylate histones in MMTV chromatin, resulting in inhibition of the GR transcriptional activity.

Fig. 7.

HDACs are involved in suppression of GR transactivation by sLZIP. A, COS-7 cells were transfected with the mock and sLZIP expression vectors (2 μg) together with the expression vectors for GR, MMTV-Luc, and β-galactosidase. Cells were treated with or without 100 nm Dex for 6 h and were subsequently treated with the indicated concentrations of TSA. The luciferase activity was normalized by β-galactosidase activity, and the experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± sd and are presented as the relative luciferase activity. B, COS-7 cells were transfected with the mock and sLZIP expression vectors (2 μg) together with the GR expression plasmid and the MMTV-Luc reporter gene plasmid. ChIP assays were performed with anti-HDAC1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6, and anti-acetyl H4 antibodies in the presence and absence of 100 nm Dex. Anti-IgG used as a negative control.

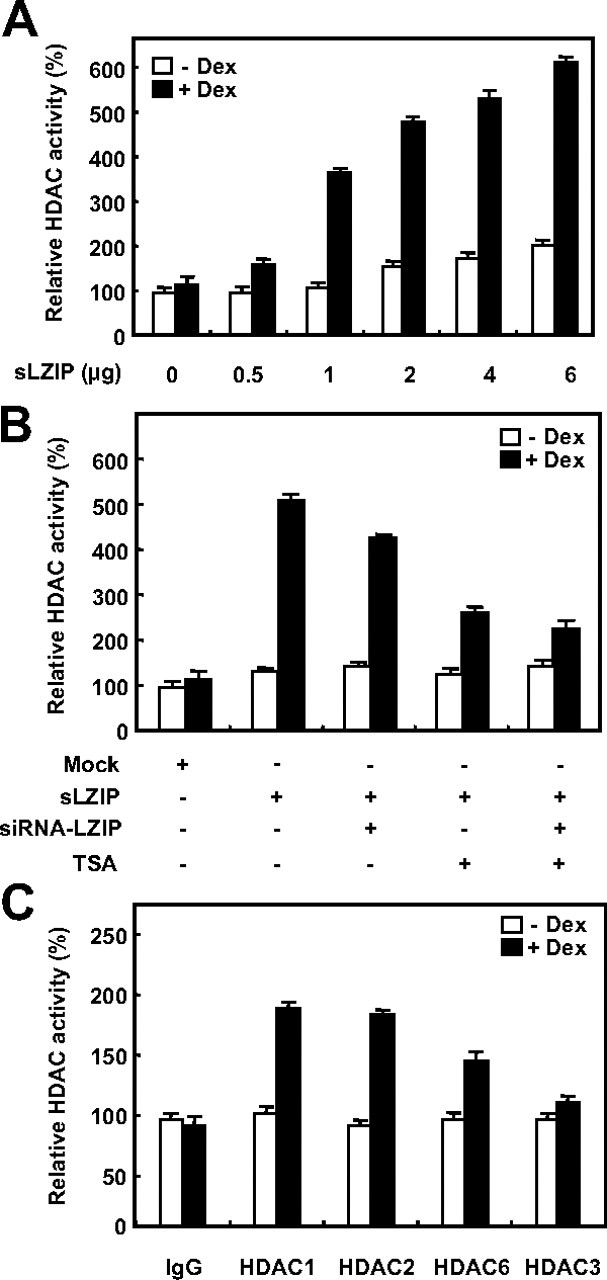

To confirm whether sLZIP stimulates HDAC activity, HDAC activity assays were performed in the presence and absence of Dex. HeLa cells were transfected with or without sLZIP and treated with Dex. As shown in Fig. 8A, sLZIP increased HDAC activities in response to Dex in a dose-dependent manner. However, HDAC activities were not affected by sLZIP in the absence of Dex (Fig. 8A). Enhanced HDAC activity due to sLZIP was decreased in cells cotransfected with both sLZIP and siLZIP (Fig. 8B). Also, HDAC activity was decreased by the treatment with TSA; however, HDAC activity was not further decreased by siLZIP in cells treated with TSA (Fig. 8B). To determine the specificity of HDAC activity, HDAC1, -2, and -6, and HDAC3 as a negative control were immunoprecipitated and assayed for HDAC activity. Immunoprecipitated HDAC1, -2, and -6 increased the HDAC activities in cells transfected with sLZIP in response to Dex, whereas HDAC3 did not affect the HDAC activity (Fig. 8C). Rabbit IgG control antibody was used as a negative control. These observations were consistent with previous results. Taken together, we propose that sLZIP negatively regulates the transcriptional activity of GR in response to glucocorticoids by recruiting a specific HDAC-containing complex, in turn, enhancing the HDAC activities.

Fig. 8.

sLZIP decreases the GR transcriptional activity by recruiting and activating HDACs. A, HeLa cells were transfected with various amounts of sLZIP and were treated with or without 100 nm Dex for 6 h. After nuclear extracts were prepared, HDAC activity was determined by using an HDAC activity assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. B, HeLa cells were transfected with the mock vector, 2 μg sLZIP, and 2 μg siLZIP expression vectors. Cells were treated with or without 100 nm Dex for 6 h and were subsequently treated with or without 100 nm TSA. After nuclear extracts were prepared, HDAC activity was determined. C, HeLa cells were transfected with the mock vector and 2 μg sLZIP expression vector. Cells were treated with or without 100 nm Dex for 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HDAC1, -2, and -6 antibodies. IgG and HDAC3 were used as negative controls. HDAC activity was presented as the relative HDAC activity, and the experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± sd.

Negative regulation of the GR transcriptional activity by sLZIP leads to suppression of glucocorticoid-induced gene expression

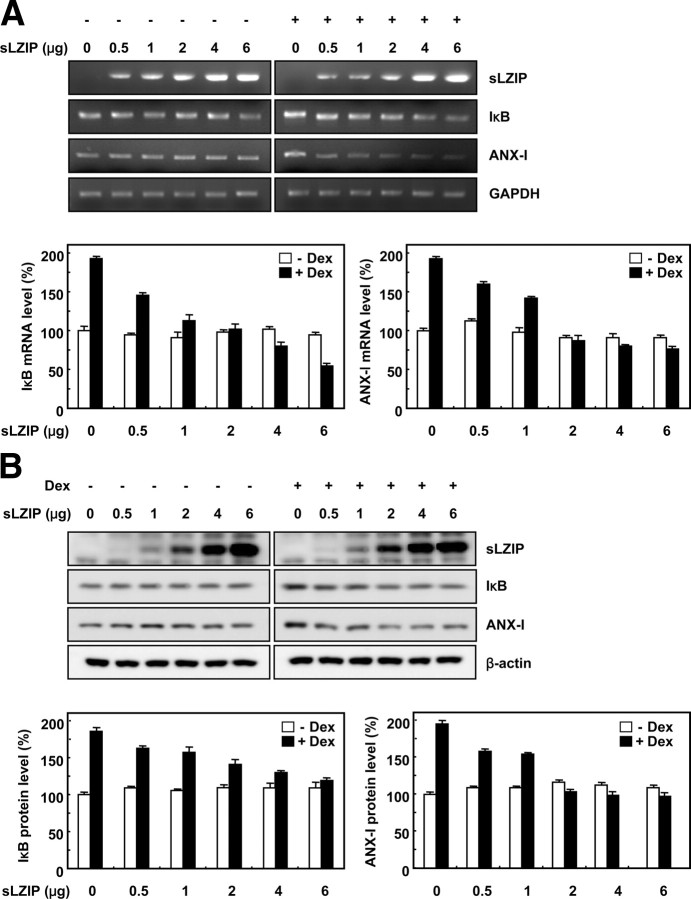

Because GR induces expression of a diverse array of genes involved in inflammatory responses, we examined whether repression of the GR transcriptional activity by sLZIP affects the expressions of the GR-mediated genes Annexin-I (ANX-I) and IκB. HeLa cells were transfected with the mock vector and sLZIP and subjected to Western blotting in the presence and absence of Dex. Dex treatment induced expressions of ANX-I and IκB both at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 9, A and B). sLZIP did not affect the expressions of ANX-I and IκB at either the mRNA and protein levels in the absence of Dex. However, in cells treated with Dex, sLZIP decreased the mRNA and protein expressions of both GR target genes in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 9, A and B). These results indicate that sLZIP functions as a negative regulator in the glucocorticoid-induced transcriptional activation of GR, leading to suppression of the gene expression induced by the glucocorticoid-mediated GR transactivation pathway.

Fig. 9.

sLZIP down-regulates the expressions of glucocorticoid-induced genes at both the mRNA and protein levels. A, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of sLZIP expression vector and were incubated with or without 100 nm Dex for 24 h. After total RNA was extracted from the cells, the mRNA expression levels of ANX-I and IκB were examined by RT-PCR analysis. The analysis was repeated three times, and GAPDH was used as an internal control. Densitometric analysis was performed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). Data are expressed as the mean ± sd. B, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of sLZIP expression vector and were incubated with or without 100 nm Dex for 24 h. Cell lysates were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (20 μg/lane) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The protein levels of ANX-I and IκB were detected by Western blotting using polyclonal anti-ANX-I and anti-IκB antibodies. The membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody. β-actin was used as an internal control. Densitometric analysis was performed using Quantity One software. Data are expressed as the mean ± sd.

Discussion

Transcription factors that belong to the basic leucine zipper superfamily play important roles in a variety of cellular processes by regulating the expressions of genes involved in many signal pathways and intracellular events. Human LZIP is known to be involved in cell proliferation, cell migration, ER stress-mediated signaling, tumor suppression, and inflammatory gene expression (3, 4, 5, 7). Although there have been advances in our understanding of the roles of LZIP, characterization of this protein is still not established. In this study, we identified a novel variant of human LZIP and determined its unique role in ligand-induced transactivation of GR. It has been reported that the subcellular localization of LZIP is in the ER membrane where it functions as an ER stress-activated transcription factor (26). LZIP has also been reported to be associated with the plasma membrane where it binds to chemokine receptors (5). In addition, it has been reported that LZIP exists in the nucleus where it functions as a tumor suppressor that is targeted by the hepatitis C virus core protein (3). Thus the subcellular localization of human LZIP has been controversial. We found that a novel human isoform is mainly located in the nucleus and may function as a transcriptional cofactor in the nucleus. The controversy regarding different subcellular localizations and functions may be due to variants of LZIP that have different localizations and functions. Therefore, identification of a novel LZIP isoform provides important information to better understand the different cellular roles of isoforms in the human LZIP family. To characterize the properties of sLZIP, the sequence and expression pattern of sLZIP were analyzed. LZIP and sLZIP transcripts were abundantly expressed in various tissues, although LZIP expression was dominant in all tissues examined. Although the sequences and genomic structures of LZIP and sLZIP genes were identical, except for a putative transmembrane domain, the function of sLZIP was different from LZIP in suppression of the glucocorticoid-induced transactivation of GR. LZIP was primarily located in the cytoplasm and had no effect on the ligand-mediated GR transcriptional activation.

It has been reported that the N terminus of human LZIP (residues 1–92) contains a potent transcriptional activation domain that is composed of three functional elements, including two LxxLL motifs (also referred to as nuclear receptor boxes) and the host cell factor-binding motif (24). In particular, the LxxLL motifs have been found in a number of non-DNA-binding transcriptional coactivators, and they mediate recognition of other coactivators/corepressors and the nuclear hormone receptors (10). The LxxLL motif found in receptor-interacting protein 140, steroid receptor coactivator 1, and cAMP response element binding protein-binding protein is necessary to mediate the binding of these proteins to ligand-activated nuclear receptors (28). The p160 proteins contain a nuclear receptor interaction domain that harbors three LxxLL motifs, which are differentially recognized by nuclear receptors (25, 29). sLZIP, which probably is a DNA-binding transcription factor, has two LxxLL motifs. Although it is known that GR interacts preferentially with the nuclear receptor box (29), our results show that sLZIP does not directly bind to GR. This unexpected result may be due to experimental conditions. Another possible reason is that sLZIP probably recruits other transcriptional cofactors and forms a complex with GR, resulting in negative regulation of the GR transcriptional activation. Our results indicate that two LxxLL motifs of sLZIP play important roles in binding to cofactors and regulation of GR transactivation.

GR plays an important role in transactivation of various target genes by binding to the GRE element of genes, and by protein-protein interaction with other transcription factors through the LxxLL motif (13). Our data showed that sLZIP alone did not affect the MMTV reporter gene expression without glucocorticoids, whereas sLZIP decreased the MMTV reporter gene expression in ligand-activated cells. On the other hand, LZIP had no influence on ligand-induced GR transactivation. However, the MMTV reporter gene expression in cells transfected with LZIP was slightly increased in the absence of glucocorticoids, indicating that LZIP is probably involved in other MMTV reporter gene expression signal pathways in the resting state. The exact mechanism of increased MMTV reporter gene expression by LZIP in the absence of glucocorticoids is under investigation.

The transcriptional regulation of a cis element of a specific gene may involve competition between many different transcription factors with varying abundance, affinities for the site, and transcriptional potentials (8). sLZIP decreases the transactivation of GR in response to glucocorticoids, indicating that sLZIP functions as a negative regulator of GR, which is crucial to antiinflammatory responses. HDACs are known to be recruited to the GR-associated transcriptional cofactor complex, and they act to suppress the ligand-induced transactivation of GR by changing the chromatin structure (30). Our data showed that the HDAC inhibitor TSA abolished the inhibitory effect of sLZIP on glucocorticoid-induced transactivation of GR, indicating that HDAC is involved in this negative regulatory event induced by sLZIP. At least 11 HDACs are now recognized in mammalian cells and are grouped into four classes based on similarity to genes in yeast (17, 18). At the local promoter and gene level, histone acetyltransferases and HDACs are recruited by activators/repressors in the context of coactivators and corepressors to regulate the transcriptional output of target genes (31). Results from ChIP analysis showed that HDAC1, -2, and, -6 were involved in the negative regulatory effect of sLZIP on ligand-mediated GR transactivation. Because sLZIP does not directly interact with GR, the effect of sLZIP on the expression of genes harboring GRE on their promoter probably derives indirectly from protein-protein interactions with other cofactors, which recruit HDAC1, -2, and -6.

Glucocorticoids play critical roles in maintenance of a variety of cellular processes, including homeostasis of intermediary metabolism, central nervous and cardiovascular system functions, and the immune and inflammatory responses (32). The predominant effect of glucocorticoids is to terminate many inflammatory gene products, including cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, inflammatory enzymes, and receptors that have been activated during the chronic inflammatory process (32). The antiinflammatory function of glucocorticoids makes them important therapeutic agents in many inflammatory diseases. In higher concentrations they have additional effects on the synthesis of antiinflammatory proteins and postgenomic effects (33). Among the target proteins induced by glucocorticoids and GR activity, ANX-I and IκB expression were inhibited by sLZIP, suggesting that sLZIP plays an important role in inflammatory responses and expressions of genes that participate in inflammatory processes. Our findings indicate that sLZIP is a potential therapeutic target molecule that regulates inflammatory responses induced by glucocorticoids.

Excessive immune-mediated inflammation may also arise from glucocorticoid resistance in target tissues (32). GR concentration reduction in leukocytes causes glucocorticoid resistance, which is important in immune diseases such as arthritis, asthma, and AIDS (34). In this regard, overexpression of sLZIP in leukocytes may inhibit GR transactivation, leading to glucocorticoid resistance. Although further studies are required to demonstrate the therapeutic importance of sLZIP, we can begin to understand the differential roles of the different isoforms of the human LZIP family in inflammatory responses.

Materials and Methods

Materials

DMEM, RPMI 1640 and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). Rabbit polyclonal anti-sLZIP antibody was raised against a C-terminal peptide conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Anti-GR and anti-β-actin antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-HDAC1, -2, -3, -4, -5, and -6 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antiacetylhistone 4 antibody was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA). TSA and Dex were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Lkn-1 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Cell culture

COS-7, HeLa, HEK 293A and HOS/CCR1 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml). and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). THP-1 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, penicillin (100 U/ ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

Transient transfection

COS-7 cells were plated at a density of 4 × 105 cells per well in a six-well plate. After 18–24 h, cells were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of the reporter gene plasmid and the experimental plasmid using lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 24 h of transfection, cells were grown in the same medium supplemented with 0.5% FBS for 24 h. Serum-starved cells were used for the assays. HOS/CCR1 cells were plated at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well in a six-well plate. After 24 h, cells were transfected with 2 μg of the vector control plasmid and the sLZIP expression plasmid using lipofectamine 2000 reagents.

RNA extraction and semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells with Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Approximately 2 μg of total RNA were used to prepare cDNA using the Superscript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bioneer, Daejeon, South Korea). The experimental conditions were as follows: 96 C for 40 sec, 60 C for 40 sec, and 72 C for 40 sec for 22 cycles. Primer pairs of sLZIP and GR were as follows. Sense primer for sLZIP, 5′-ATGGAGCTGGAATTGGATGC-3′; and antisense primer, 5′-CTAGCCTGAGTATCTGTCCT-3′. Sense primer for GR, 5′-TTTCTTATGGCATTTGCTCTG-3′; and antisense primer, 5′-GATGACGACTCAACTGCTTCTG-3′. GAPDH was amplified as an internal control. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% (wt/vol) agarose gel in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer, and stained with ethidium bromide solution. All the PCRs were repeated at least three times. The intensity of each band amplified by RT-PCR was analyzed using MultiImage Light Cabinet (version 5.5, Alpha Innotech Corp., San Leandro, CA) and normalized to that of GAPDH mRNA in corresponding samples.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested and washed with ice-cold PBS. Cells were then resuspended in 100 ml of lysis buffer [150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 mm Na3VO4, and protease inhibitors]. The suspension was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4 C. Protein samples (20 μg of each lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. The blots were incubated with anti-GR and anti-sLZIP antibodies. Membranes were processed using chemiluminescence detection reagents (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL). The same blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody for use as an internal control.

Confocal microscopy

HeLa cells transiently transfected with LZIP and sLZIP were grown on cover slips. After 24 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Cells were incubated with 1% BSA for 1 h and a polyclonal anti-sLZIP antibody for 1 h. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antirabbit antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 h. Cover slides were washed with PBS, mounted, and examined using a LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Luciferase reporter gene activity assay

Luciferase assays were performed using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). The transfected cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in the culture dishes with reporter lysis buffer. Luciferase activities were recorded in a Luminometer 20/20n (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity. For β-galactosidase assay, pSV-β-galactosidase was cotransfected with the luciferase reporter gene. Cell extracts were assayed for β-galactosidase activity using the β-galactosidase enzyme assay system (Promega) and analyzed by a DU530 spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA). The ratio of luciferase to β-galactosidase activity was determined in triplicate samples. All data are presented as the mean ± sd of at least three independent experiments.

GR-transcriptional activity assay

GR-transcriptional activity was measured in nuclear extracts using an ELISA-based TransAM GR Transcription Factor Assay Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Nuclear extracts from mock or sLZIP-transfected HeLa cells were incubated in oligonucleotide-coated 96-well plates containing a GRE consensus sequence. GR binding to oligonucleotides was colorimetrically detected in nuclear extracts by an enzyme-immunosorbent method using an anti-GR antibody.

ChIP assay

For ChIP experiments, approximately 1 × 106 cells were assayed per sample. Cells were washed with PBS and treated with 1% formaldehyde in media for 10 min at 25 C followed by addition of glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 m for 5 min. Cells were then scraped into PBS and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4 C. The ChIP assays were performed by coprecipitating the DNA-protein complexes with antiacetyl H4, anti-HDAC1, -2, -3, -4, -5, and -6 antibodies and antirabbit IgG as an internal control. The promoter region −219 to −47 of the MMTV long terminal repeat (fragment size 173 bp), which contains two functional GREs, was amplified from the prepared DNA samples using a primer pair: sense primer, 5′-AACCTTGCGGTTCCCAG-3′; and antisense primer, 5′-GCATTTACATAAGATTTGG-3′.

Measurement of HDAC activity

For fluorimetric HDAC activity assay, anti-HDAC antibodies and rabbit IgG immunoprecipitates from nuclear extracts of HeLa cells transfected with sLZIP were washed with assay buffer provided with an HDAC fluorimetric assay kit (Anaspec, San Jose, CA). The immunoprecipitates were then incubated with fluorescence-producing substrate (HDAC 520 substrate) at 25 C and treated with developer solution for 15 min. Fluorescence signals were detected in a 96-well plate using Zenyth 3100 UV/VIS FLUORO detector (Anthos Labtec Instruments, Salzburg, Austria) with excitation at 490 nm and emission at 520 nm. Inhibitor controls were included, and all reactions were set up in duplicate.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Coregulators: HDAC1 | HDAC2 | HDAC3 | HDAC4;

Ligands: Dexamethasone;

Nuclear Receptors: GR.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation Grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Education, Science and Technology) (R01-2007-000-10778-0), and a Grant from the Diseases Network Research Program (M10751050002-07N5105-00210), Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, South Korea.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online September 24, 2009

H.K. and Y.S.K. contributed equally to this study.

Abbreviations: ANX-I, Annexin-I; CCR, CC chemokine receptor; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; Dex, dexamethasone; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; GRE, glucocorticoid-responsive element; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HEK, human embryonic kidney; Lkn, leukotactin; LZIP, human leucine zipper protein; MMTV, mouse mammary tumor virus; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; siLZIP, siRNA-sLZIP; siRNA, small interfering RNA; sLZIP, small LZIP; TSA, trichostatin.

References

- 1.Raggo C, Rapin N, Stirling J, Gobeil P, Smith-Windsor E, O'Hare P, Misra V2002. Luman, the cellular counterpart of Herpes simplex virus VP16, is processed by regulated intramembrane proteolysis. Mol Cell Biol 22:5639–5649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freiman RN, Herr W1997. Viral mimicry: common mode of association with HCF by VP16 and the cellular protein LZIP. Genes Dev 11:3122–3127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin DY, Wang HL, Zhou Y, Chun AC, Kibler KV, Hou YD, Kung H, Jeang KT2000. Hepatitis C virus core protein-induced loss of LZIP function correlates with cellular transformation. EMBO J 19:729–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang G, Audas TE, Li Y, Cockram GP, Dean JD, Martyn AC, Kokame K, Lu R2006. Luman/CREB3 induces transcription of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response protein Herp through an ER stress response element. Mol Cell Biol 26:7999–8010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko J, Jang SW, Kim YS, Kim IS, Sung HJ, Kim HH, Park JY, Lee YH, Kim J, Na DS2004. Human LZIP binds to CCR1 and differentially affects the chemotactic activities of CCR1-dependent chemokines. FASEB J 18:890–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blot G, Lopez-Vergès S, Treand C, Kubat NJ, Delcroix-Genête D, Emiliani S, Benarous R, Berlioz-Torrent C2006. Luman, a new partner of HIV-1 TMgp41, interferes with Tat-mediated transcription of the HIV-1 LTR. J Mol Biol 364:1034–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sung HJ, Kim YS, Kang H, Ko J2008. Human LZIP induces monocyte CC chemokine receptor 2 expression leading to enhancement of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1/CCL2-induced cell migration. Exp Mol Med 40:332–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burbelo PD, Gabriel GC, Kibbey MC, Yamada Y, Kleinman HK, Weeks BS1994. LZIP-1 and LZIP-2: two novel members of the bZIP family. Gene 139:241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cato AC, Wade E1996. Molecular mechanisms of anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoids. Bioessays 18:371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM1995. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell 83:835–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito K, Yamamura S, Essilfie-Quaye S, Cosio B, Ito M, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM2006. Histone deacetylase 2-mediated deacetylation of the glucocorticoid receptor enables NF-κB suppression. J Exp Med 203:7–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adcock IM, Ito K, Barnes PJ2004. Glucocorticoids: effects on gene transcription. Proc Am Thorac Soc 1:247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogatsky I, Luecke HF, Leitman DC, Yamamoto KR2002. Alternate surfaces of transcriptional coregulator GRIP1 function in different glucocorticoid receptor activation and repression contexts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:16701–16706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellingham DL, Sar M, Cidlowski JA1992. Ligand-dependent down-regulation of stably transfected human glucocorticoid receptors is associated with the loss of functional glucocorticoid responsiveness. Mol Endocrinol 6:2090–2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong Y, Poellinger L, Okret S, Höög JO, von Bahr-Lindström H, Jörnvall H, Gustafsson JA1988. Regulation of gene expression of class I alcohol dehydrogenase by glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:767–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW1999. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev 20:321–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Ruijter AJ, van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB2003. Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J 370:737–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiagalingam S, Cheng KH, Lee HJ, Mineva N, Thiagalingam A, Ponte JF2003. Histone deacetylases: unique players in shaping the epigenetic histone code. Ann NY Acad Sci 983:84–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson CL2002. HDAC’s at work. Mol Cell 9:921–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plesko MM, Hargrove JL, Granner DK, Chalkley R1983. Inhibition by sodium butyrate of enzyme induction by glucocorticoids and dibutyryl cyclic AMP. A role for the rapid form of histone acetylation. J Biol Chem 258:13738–13744 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jang SW, Kim YS, Kim YR, Sung HJ, Ko J2007. Regulation of human LZIP expression by NF-κB and its involvement in monocyte cell migration induced by Lkn-1. J Biol Chem 282:11092–11100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abel T, Bhatt R, Maniatis T1992. A Drosophila CREB/ATF transcriptional activator binds to both fat body- and liver-specific regulatory elements. Genes Dev 6:466–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang SW, Kim YS, Lee YH, Ko J2007. Role of human LZIP in differential activation of the NF-κB pathway that is induced by CCR1-dependent chemokines. J Cell Physiol 211:630–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luciano RL, Wilson AC2000. N-terminal transcriptional activation domain of LZIP comprises two LxxLL motifs and the host cell factor-1 binding motif. Proc Natl Acad USA 97:10757–10762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding XF, Anderson CM, Ma H, Hong H, Uht RM, Kushner PJ, Stallcup MR1998. Nuclear receptor-binding sites of coactivators glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) and steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1). Mol Endocrinol 12:302–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu R, Misra V2000. Potential role for luman, the cellular homologue of herpes simplex virus VP16 (α gene trans-inducing factor), in herpesvirus latency. J Virol 74:934–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ichijo T, Voutetakis A, Cotrim AP, Bhattachryya N, Fujii M, Chrousos GP, Kino T2005. The smad6-histone deacetylase 3 complex silences the transcriptional activity of the glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem 280:42067–42077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westin S, Kurokawa R, Nolte RT, Wisely GB, McInerney EM, Rose DW, Milburn MV, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK1998. Interactions controlling the assembly of nuclear-receptor heterodimers and co-activators. Nature 395:199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plevin MJ, Mills MM, Ikura M2005. The LxxLL motif: a multifunctional binding sequence in transcriptional regulation. Trends Biochem Sci 30:66–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito K, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM2000. Glucocorticoid receptor recruitment of histone deacetylase 2 inhibits interleukin-1β-induced histone H4 acetylation on lysines 8 and 12. Mol Cell Biol 20:6891–6903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Struhl K1998. Histone acetylation and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Genes Dev 12:599–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chrousos GP1995. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N Engl J Med 332:1351–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnes PJ2006. How corticosteroids control inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 148:245–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis-Tuffin LJ, Cidlowski JA2006. The physiology of human glucocorticoid receptor β (hGRβ) and glucocorticoid resistance. Ann NY Acad Sci 1069:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]