Abstract

The progesterone receptor (PR) plays important roles in the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. By dynamic interactions with coregulators, PR represses the expression of genes that increase the contractile activity of myometrium and contribute to the initiation of labor. We have previously shown that PTB-associated RNA splicing factor (PSF) can function as a PR corepressor. In this report, we demonstrated that the PSF heterodimer partner, p54nrb (non-POU-domain-containing, octamer binding protein), can also function as a transcription corepressor, independent of PSF. p54nrb Interacts directly with PR independent of progesterone. In contrast to PSF, p54nrb neither enhances PR protein degradation nor blocks PR binding to DNA. Rather, p54nrb recruits mSin3A through its N terminus to the PR-DNA complex, resulting in an inhibition of PR-mediated transactivation of the progesterone-response element-luciferase reporter gene. PR also repressed transcription of the connexin 43 gene (Gja1), an effect dependent on the presence of an activator protein 1 site within the proximal Gja1 promoter. Mutation of this site abolished PR-mediated repression and decreased the recruitment of PR and p54nrb onto the Gja1 promoter. Furthermore, knockdown p54nrb expression by small interfering RNA alleviated PR-mediated repression on Gja1 transcription, whereas overexpression of p54nrb enhanced it. In the physiological context of pregnancy, p54nrb protein levels decrease with the approach of labor in the rat myometrium. We conclude that p54nrb is a transcriptional corepressor of PR. Decreased expression of p54nrb at the time of labor may act to derepress PR-mediated inhibition on connexin 43 expression and contribute to the initiation of labor.

The progesterone receptor (PR) co-repressor, p54nrb, contributes to the functional withdrawal of progesterone and the initiation of labor by de-repressing PR-mediated inhibition of Cx43 expression.

Progesterone receptors (PRs) play an essential role in reproductive events associated with the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy through modulating gene transcription in target organs (1, 2). At the end of pregnancy, there is a transformation of the myometrial phenotype from one of relative quiescence, unresponsiveness, and limited conductivity during pregnancy to one that is highly responsive and excitable at term (1). Biochemically, this transformation is characterized by up-regulation in the expression and function of genes encoding a cassette of labor-associated proteins such as the gap junction connexin 43 (Gja1) (3), ion channels (4), and stimulatory uterotonin receptors (5, 6). It is known that progesterone signaling represses the expression of several of these labor genes (7, 8, 9). Derepression of the transcription of these labor genes at term can be achieved either by a decline in circulating progesterone levels or by blockade of PR function. In the human myometrium, two major isoforms of PR are expressed, the full-length PRB and an N-terminally 164 amino acids truncated PRA (10). PRA is generally a weaker transcriptional activator than PRB (11, 12) and can also act as a repressor of PRB as well as of other steroid receptors (13, 14). Several studies have proposed that changes in expression of PR protein isoforms (15, 16) as well as PR coactivators (17) may contribute to the blockade of PR function in myometrium at term labor. However, detailed molecular mechanisms by which PR modulates transcription of labor-associated genes to initiate labor at term remain unclear.

Gene transcription involves a series of biochemical reactions starting from chromatin remodeling, transcription initiation, elongation, RNA splicing, and termination (18). These complicated reactions are believed to be executed by the so-called general transcription machinery that process constitutively and sequentially protein-protein and protein-nucleotide reactions (19). Growing evidence of protein interactions between transcription factors and RNA splicing factors support the notion that transcription initiation and RNA splicing are coordinately controlled (20, 21). Gene transcription initiation driven by PR relies on coregulators (including coactivators and corepressors) (19, 22), and that dynamic balance of these coregulators determines the transcription rate of target genes (23, 24). The coregulators possess not only transcription activation or repression domains but also various enzymatic activities that modify chromatin structures and chromatin-bound proteins to create a transcriptionally permissive or nonpermissive environment (25). Among the corepressors is the mSin3A-HDAC complex, in which mSin3A forms a large multiprotein complex containing histone deacetylase (HDAC)1, HDAC2, RbAP46/48, and a number of Sin-associated proteins (26, 27, 28, 29, 30). mSin3A provides the platform for the complex whereas HDAC1/HDAC2 provide enzymatic activities to remove the acetyl group from target lysine residues within histones (28, 30, 31). Recruitment of the mSin3A-HDAC complex generally creates a transcriptionally nonpermissive environment.

Several RNA splicing factors have been reported to participate in regulating transcription initiation through protein interactions with transcriptional factors and/or the core general transcriptional machinery (32, 33, 34, 35, 36). Splicing factors such as peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1, SF(3a), and CAPER interact directly with steroid receptors and coactivate their transcriptional activity (37, 38, 39). However, other RNA splicing factors, such as PTB-associated RNA splicing factor (PSF), inhibit transcription initiation through interactions with nuclear receptors (40, 41) or other transcription factors (42, 43) or in some cases directly with DNA elements within the promoters of target genes (44, 45). We have shown that PSF inhibits PR transactivation through enhancing PR protein degradation as well as interfering with PR binding to DNA (46). We have also demonstrated that PSF corepresses AR transactivation through the recruitment of the mSin3A-HDAC complex (47). These different effects of RNA splicing factors on transcription initiation indicate their complicated roles in regulating the levels of gene transcripts. One possible explanation for these diverse effects on gene transcription could be the different protein complexes with which these RNA splicing factors associate. It is thus important to investigate how RNA splicing factor-interacting proteins modulate gene transcription to enable cells to intricately control gene expression.

PSF usually forms a heterodimer with its partner p54nrb (non-POU-domain-containing, octamer binding protein), also a RNA splicing factor, in vivo (48). Human p54nrb shares 71% identity with PSF within a central region that includes two RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) (48, 49). Consistent with the multifunctional properties of RNA splicing factors, p54nrb can bind single- and double-stranded RNA and DNA and participate in numerous processes within the nucleus, including transcription initiation, RNA processing, transcription elongation, and termination (as reviewed in Ref. 50). As part of the splicesomal complex, PSF and p54nrb were demonstrated to be essential for both step I and II pre-mRNA splicing reactions (51, 52, 53). These observations indicate that PSF/p54nrb can positively regulate gene transcription through the RNA splicing process. However, several reports show that PSF/p54nrb can form protein complexes with transcription factors or even directly with DNA elements within the promoter region to repress transcription initiation (40, 43, 45, 46). These data suggest that, depending on the protein complex to which it is associated, p54nrb can either positively or negatively regulate gene transcription.

In this study, we demonstrate that p54nrb inhibits PR transactivation independent of PSF. In contrast to PSF, inhibition of PR transactivation by p54nrb does not involve PR protein degradation or inhibition of PR binding to DNA; rather, p54nrb acts by recruiting mSin3A to the PR complex. Expression of p54nrb protein falls at the end of pregnancy in rat myometrium, which may release the PR-mediated repression of labor-associated genes such as Gja1 at term pregnancy. These findings indicate that p54nrb is a corepressor of PR and may play a role in the initiation of term labor.

Results

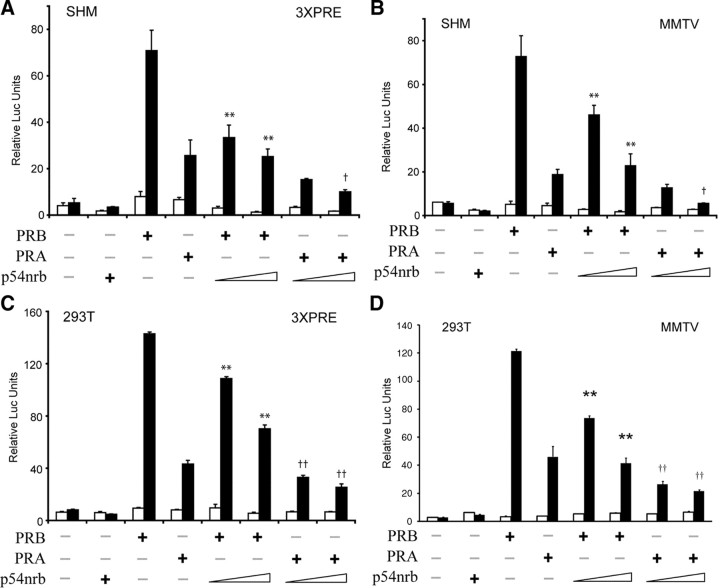

p54nrb Inhibits transcriptional activity of PR

We have previously demonstrated that PSF corepresses PR in a ligand-independent manner. Therefore we hypothesize that the PSF heterodimer, p54nrb, may have a similar function. Transient transfections of reporter gene constructs were conducted in the hamster myometrial cell line (SHM) and the immortalized human embryonic kidney cell line (293T) to determine the functional significance of p54nrb on PR. We used two progesterone-responsive promoters: an artificial promoter with three copies of the progesterone response element (PRE) (3 × PRE) and the steroid-responsive mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter. Overexpression of PRB presented strong transcriptional activity on MMTV and 3× PRE promoters, whereas the transactivation by PRA is weak. The luciferase activity driven by PRA in the presence of progesterone is only 4- to 8-fold higher than that in the absence of progesterone. p54nrb potently inhibits PRB transactivation on both promoters in SHM cells (Fig. 1, A and B). However, the inhibitory effect of p54nrb on PRA is modest (likely due to the weak transactivation properties of PRA) but, nevertheless, statistically significant. Similar inhibitory effects were also observed in the experiments repeated in 293T cells (Fig. 1, C and D), indicating that the transcriptional repressive function of p54nrb is independent of cell and promoter contexts. Cotransfection of increasing doses of p54nrb with PRA or PRB in SHM cells resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of PR transactivation, and the repressive function of p54nrb was observed over a wide range (0.1 nm to 1 μm) of progesterone concentrations (supplemental Fig. l. published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). We conclude that p54nrb is an inhibitor of PR transactivation.

Fig. 1.

SHM (A and B) and 293T cells (C and D) were transiently transfected with 50 ng of PRA, PRB expression vector, and increasing doses (300 and 500 ng) of Flag-p54nrb vector together with 200 ng of either 3 × PRE-luc (A and C) or MMTV-luc (B and D) reporter. Cells were treated 24 h after transfection with vehicle (□) or 1 nm progesterone (▪) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Values are shown as means ± sem from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (**, P < 0.01 relative to PRB transactivation alone in the presence of progesterone; †, P < 0.05; and ††, P < 0.01 relative to PRA transactivation alone in the presence of progesterone). Note: the empty vector pcDNA3.1 was added to the DNA mixture to ensure that equal amounts of DNA were transfected in cells.

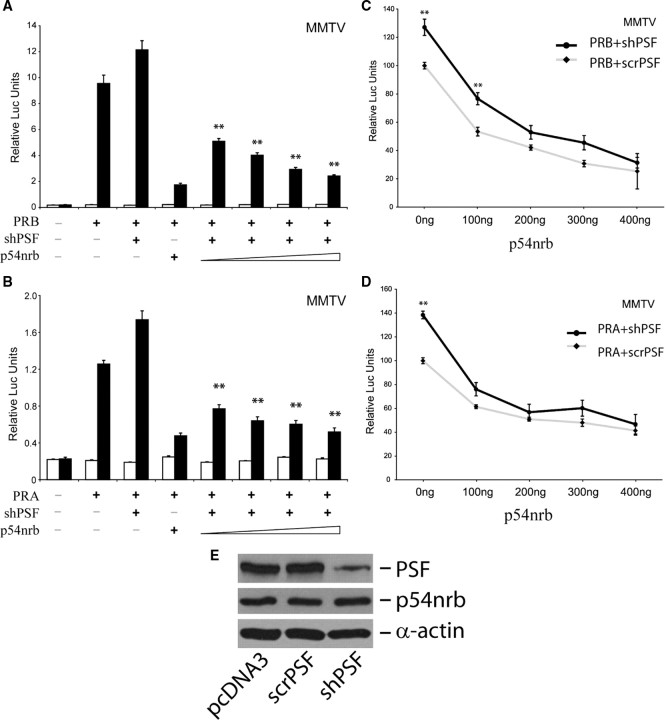

Transcriptional repressor function of p54nrb is independent of PSF

To determine whether the corepressor function of p54nrb on PR is dependent upon the presence of PSF, we used short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to knockdown endogenous PSF levels and then measured the repressor activity of p54nrb on PR. We specifically and effectively knocked down endogenous PSF expression by transfecting cells with a vector encoding the shRNA against PSF (47). 293T cells were transiently transfected with a constant dose of the short hairpin PSF (shPSF) vector and increasing doses of the p54nrb expression vector together with PRB and MMTV-luc reporter vectors (Fig. 2A). Even in the presence of PSF knockdown, p54nrb can still decrease PRB-mediated luciferase activity in a dose-dependent fashion. Similar inhibitory effects were also observed in the experiments when the PRA vector was used (Fig. 2B). In parallel experiments, 293T cells were transfected with increasing doses of p54nrb vector together with shPSF or scrambled PSF (scrPSF) vector (Fig. 2, C and D), p54nrb inhibited PR transactivation even though PR activity was higher in cells transfected with shPSF compared with cells transfected with scrPSF. The effectiveness of the shPSF vector is shown in Fig. 2E. We also tested the inhibitory effects of p54nrb on PR transactivation in the presence of PSF overexpression (supplemental Fig. 2). Even in the presence of PSF overexpression, p54nrb can further decrease PRB-mediated luciferase activity. Vice versa, in the presence of p54nrb overexpression, PSF can further decrease PRB transactivation. Similar results were also observed when experiments were repeated using PRA. These additive effects were limited likely due to the high endogenous levels of PSF and p54nrb or the near maximum inhibition produced by the plasmid input dose of PSF/p54nrb. In summary, p54nrb inhibits PR transactivation regardless of knockdown or overexpression of PSF, indicating that corepressive function of p54nrb is independent of PSF.

Fig. 2.

293T cells were transiently transfected with 100 ng of PRB or PRA expression vector and MMTV-luc reporter, together with (A and B) 200 ng of shPSF vector plus increasing doses (100, 200, 300, and 500 ng) of p54nrb vector, or (C and D) 200 ng of shPSF or scrPSF vector plus increasing doses (100, 200, 300, and 500 ng) of p54nrb vector. Cells were treated 48 h after transfection with either vehicle (□) or 1 nm progesterone (▪) for another 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Values are shown as means ± sem from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA [**, P < 0.01 relative to PRB (A) or PRA (B) cotransfected with shPSF; and **, P < 0.01 relative to PRB (C) or PRA (D) cotransfected with scrPSF]. Note: the empty vector pcDNA3.1 was added to the DNA mixture to ensure that equal amounts of DNA were transfected in cells. E, 293T cells were seeded in six-well plates and were transfected with 4 μg of pcDNA3, scrPSF, or shPSF vector for 48 h. Whole-cell lysates were then used to detect endogenous PSF, p54nrb, and α-actin protein levels by immunoblotting.

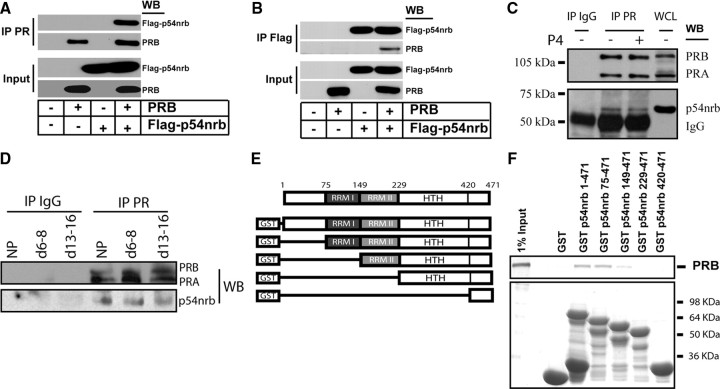

p54nrb forms a protein complex with PR

We next sought to determine whether the repressor function of p54nrb on PR was mediated through interactions between p54nrb and PR. First, 293T cells were transiently transfected with PRB and/or Flag-p54nrb vectors, and cell lysates were precipitated with either PR- or Flag tag-specific antibody. PR antibody was able to coprecipitate PR and Flag-p54nrb (Fig. 3A). Likewise, Flag antibody can also precipitate both Flag-p54nrb and PRB (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that p54nrb and PR form a protein complex in vivo. Next, to determine whether endogenously expressed PR and p54nrb can also form a protein complex, T47D cell lysates were precipitated with PR antibody. p54nrb associated with PR irrespective of the presence of progesterone (Fig. 3C). To confirm that PR-p54nrb complex exists in myometrium, we collected myometrial lysates from nonpregnant rat and pregnant rats at early-pregnant (d 6–8) and midpregnant (d 13–16) stages. PR antibody, but not control IgG, precipitated both PR and p54nrb, further confirming that myometrial PR and p54nrb are associated with each other (Fig. 3D). Third, to determine whether p54nrb directly interacts with PR, and if so to map the interacting sites between p54nrb and PR, we performed glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays. GST fusion proteins containing various domains of p54nrb were incubated with [35S]methionine-labeled PRB (Fig. 3, E and F). Both full-length p54nrb and its deletion mutant p54nrb 75–471 have the similar capacity to retain the PRB in the GST Sepharose matrix. However, p54nrb 149–471 significantly decreased the association with PRB. Deletion mutants of p54nrb 229–471 and 420–471 failed to interact with PRB. These data indicate that PRB interacts with the region of aa 75–229 of p54nrb, which contains the two RNA recognition motifs, RRM I and RRM II. Taken together, our data unequivocally demonstrate that p54nrb can form a protein complex with PR in a ligand-independent fashion and that p54nrb-PR interaction does not require the presence of PSF.

Fig. 3.

293T cells were transiently transfected with PRB and or Flag-p54nrb vectors. Cell lysates were precipitated with PR (A) or Flag tag (B) antibody. The associated proteins were immunoblotted with antibodies as indicated. C, Endogenous PR-p54nrb complex was shown by precipitating T47D cell lysate with PR antibody in the presence of vehicle or 1 nm progesterone. The precipitated proteins were immunoblotted with PR and p54nrb antibodies. D, Uterine protein lysates collected from nonpregnant (NP), and early (d 6–8) and midterm (d 13–16) pregnant rat were used to precipitate with either rabbit control IgG or PR antibody (H190, Santa Cruz). The associated proteins were immunoblotted with PR and p54nrb antibodies. E, Schematic diagram of vectors encoding GST fusion proteins with p54nrb or its deletion mutants. F, GST fusion proteins of p54nrb or its mutants were incubated with [35S]methionine-labeled PRB (top). GST or GST fusion proteins used in the pull-down assay were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate gels and stained with Coomassie blue (bottom). IP, Immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

Mechanism of transcription repressor function of p54nrb

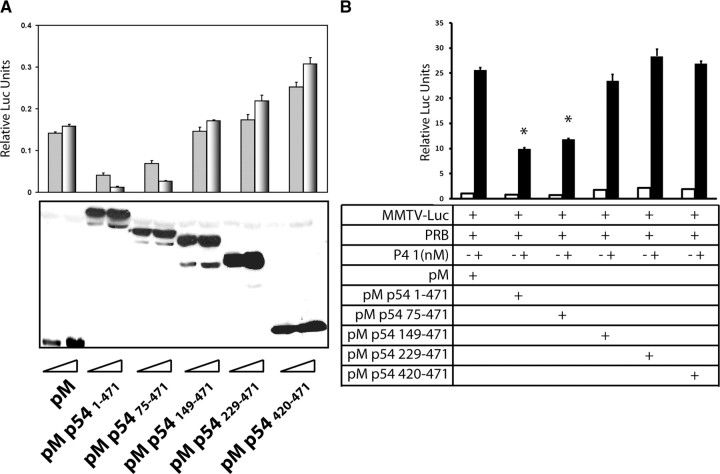

We showed that PSF inhibits the transactivation of PR through mechanisms that include enhancement of PR protein degradation and interference of PR binding to DNA (46). In contrast, experiments repeated with p54nrb indicated that p54nrb neither reduced PR protein stability nor inhibited PR binding to PRE in gel-shift assays (supplemental Fig. 3). We then performed mammalian one-hybrid assays to map the transcription repression domain within p54nrb (Fig. 4A). In these one-hybrid assays, 293T cells were transfected with vectors encoding Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) chimeras with various deletion mutants of p54nrb. These vectors were cotransfected with the G5-Luc reporter, which contains 5× Gal4 DNA-binding sites upstream of the luciferase reporter gene. The luciferase activity reflects the transcriptional activities of the p54nrb deletion mutants. We observed that Gal4-dependent luciferase activity mediated by pM-p54nrb was about 30% of that by the empty pM vector. Deletion of amino acids (aa) 1–75 recovered the luciferase activity to 40–50% of that by pM vector. Further deletion of the aa 76–149 fully recovers the repressive activity of p54nrb to the level of the pM vector. When increasing doses of p54nrb 1–471 and p54nrb 75–471 were transfected in the cells, the luciferase activity decreased in a dose-dependent manner. Other deletion mutants of p54nrb showed no decrease in luciferase activity proportional to the vector input. The expression levels of Gal4 DBD chimeras with p54nrb were detected by immunoblotting with Gal4 DBD antibody to confirm that the observed differences of luciferase activities were not due to different protein expression levels of these p54nrb chimeras (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, we applied PR/MMTV-luc system to map the transcription repression domain of p54nrb. Vectors encoding chimeras of Gal4 DBD with various deletion mutants of p54nrb were cotransfected with PRB vector and MMTV-luc reporter vectors (Fig. 4B). We consistently observed that the aa 1–149 region of p54nrb contains transcription inhibitory activity.

Fig. 4.

A, 293T cells were transfected with increasing doses (300 and 600 ng) of pM vectors encoding Gal4 DBD chimeras of p54nrb or its deletion mutants together with 200 ng of G5-Luc reporter. The luciferase activity was measured 24 h after transfection (top). Expression of Gal4 DBD and its chimera proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting with Gal4 DBD antibody (bottom). B, 293T cells were transfected with pM vectors encoding chimeras of p54nrb or its deletion mutants together with 50 ng of PRB and 200 ng of MMTV-luc reporter. Cells were treated 24 h after transfection with vehicle (□) or 1 nm progesterone (▪) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Values are shown as means ± sem from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (*, P < 0.01 relative to PRB transactivation cotransfected with empty pM vector alone).

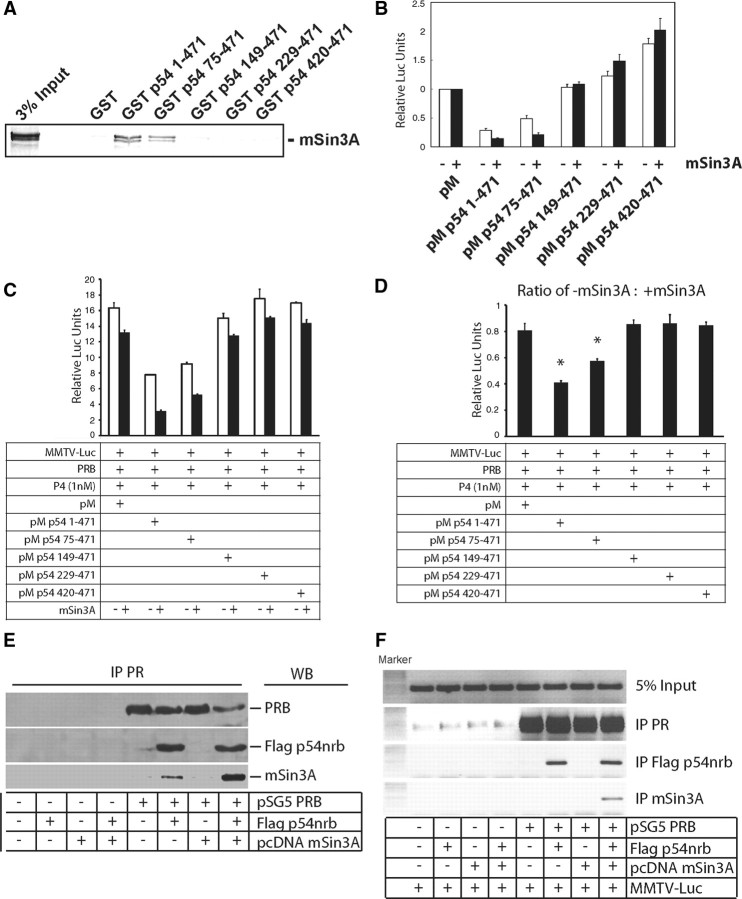

We showed that p54nrb interacts directly with mSin3A by GST pull-down assay (47). It is therefore possible that the transcription repressor function of p54nrb is mediated through protein interactions between aa 1–149 of p54nrb and mSin3A. To map the putative p54nrb-mSin3A interaction site, GST pull-down assays were performed using deletion mutants of GST-p54nrb fusion proteins incubated with [35S]methionine-labeled mSin3A (Fig. 5A). Both p54nrb 1–471 and p54nrb 75–471 associate with mSin3A to a similar extent, whereas other deletion mutants of p54nrb (aa 149–471, aa 229–471, and aa 420–471) do not interact with mSin3A, suggesting that the region aa 75–149 is the site of interaction between these proteins. These data were supported by a mammalian one-hybrid assay showing that both p54nrb 1–471 and p54nrb 75–471, but not other deletion mutants of p54nrb, responded to the cotransfection of mSin3A with a further decrease in luciferase activity (Fig. 5B). We also repeated the experiments using the PR/MMTV-luc system to map the regions within p54nrb that respond to mSin3A (Fig. 5, C and D). Although mSin3A inhibited luciferase activity driven by PRB, the degree of repression varied with Gal4 DBD chimeras of various deletion mutants of p54nrb. To separate the generic repression by mSin3A on the PR/MMTV-luc system from that through interaction with p54nrb, we plotted the luciferase ratio in the absence vs. presence of mSin3A overexpression. Consistently with the mammalian one-hybrid assay in Fig. 5B, the aa 1–149 region of p54nrb induced a further decrease of luciferase activity in the presence of mSin3A overexpression. In summary, aa 1–149 of p54nrb mediate the transcriptional repressor function of p54nrb. This repressor function of p54nrb is due, in part, to an association with mSin3A through aa 75–149 of p54nrb.

Fig. 5.

A, GST pull-down assays were performed by incubating GST fusion proteins of p54nrb or its mutants with [35S]methionine-labeled mSin3A. B, 293T cells were transfected with 200 ng vectors of pM-p54nrb or its deletion mutants without (□) or with (▪) 400 ng of mSin3A expression vector together with 200 ng of G5-Luc reporter vector, and the luciferase activity was measured 24 h after transfection. C, 293T cells were transfected 200 ng vectors of pM-p54nrb or its deletion mutants without (□) or with (▪) 400 ng mSin3A expression vector together with 50 ng of PRB and 200 ng of MMTV-luc reporter. Cells were treated 24 h after transfection with 1 nm progesterone for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Values are shown as means ± sem from three independent experiments. D, Data from panel C were plotted to show the luciferase activity ratio of absence vs. presence of mSin3A cotransfection. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (*, P < 0.01 relative to PRB transactivation cotransfected with empty pM vector). E, 293T cells were transfected with PRB, p54nrb, and mSin3A vectors as indicated. Cell lysates were precipitated with PR antibody, and associated proteins were immunoblotted with PR, Flag tag, and mSin3A antibodies. F, 293T cells were transfected with PRB, p54nrb, and mSin3A expression vectors together with MMTV-luc reporter as indicated and treated with 1 nm progesterone for 1 h. In vivo DNA-protein interaction assay was performed (as described in Materials and Methods) by PR, Flag tag, and mSin3A antibodies. IP, Immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

To confirm that p54nrb can recruit mSin3A to the PR complex, we first performed immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 5E). Flag-p54nrb and mSin3A were cotransfected with PR vector in 293T cells. Cell lysates were precipitated with PR antibody. Flag-p54nrb was associated with PR. The recruitment of mSin3A to PR was detected only when Flag-p54nrb was cotransfected. These data suggest that p54nrb mediated the recruitment of mSin3A to PR. To further confirm that p54nrb induces mSin3A recruitment to the PR-PRE complex, we performed in vivo DNA-binding assays (Fig. 5F). 293T cells were transfected with PR, Flag-p54nrb, and mSin3A vectors together with MMTV promoter and then treated with 1 nm progesterone for 1 h. Cross-linked cell lysates were used to precipitate with PR, Flag tag, and mSin3A antibodies. PR robustly associated with PRE when cells overexpressed PRB in the presence of progesterone. Flag-p54nrb was recruited to the PRE region in the MMTV depending on the presence of PR. mSin3A was also recruited to the same region only when both PR and Flag-p54nrb were cotransfected. In the absence of progesterone, neither PR nor p54nrb and mSin3A were recruited to PRE (data not shown). In summary, both the immunoprecipitation data and the in vivo protein-DNA interaction assay support the conclusion that p54nrb not only binds PR protein but also the PR-PRE complex to inhibit PR transactivation.

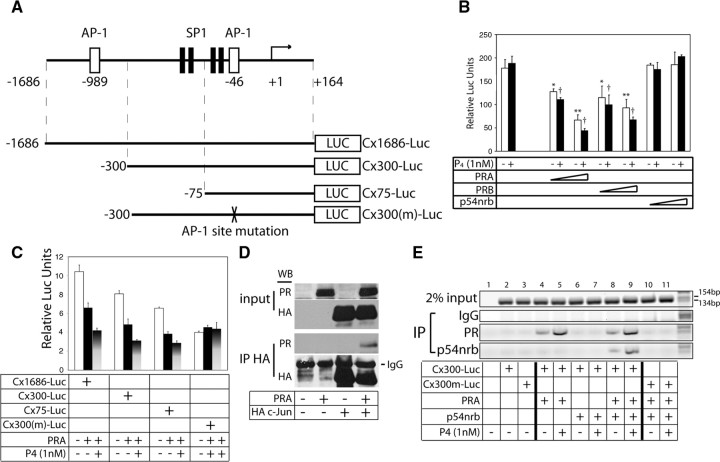

PR inhibits the transcriptional activity of Gja1 promoter

Although the PR/PRE-luc system is widely used to study PR transactivation, it is not representative of PR-mediated transcriptional repression of target genes. For example, myometrial Gja1 expression is dramatically increased at term pregnancy (3, 7) and is required for the timely onset of labor (54). Gja1 mRNA expression is inhibited by progesterone but increased by the PR antagonist RU486, suggesting that PR functions to inhibit Gja1 transcription (55). Therefore, we used the Gja1 promoter reporter gene (Cx1686-luc) to analyze the ability of PR and p54nrb to regulate the Gja1 gene transcription. Deletion mutants (Cx300-Luc and Cx75-Luc) and an activator protein 1 (AP-1) site mutant (Cx300m-luc) of Gja1 promoter reporter vectors are depicted in Fig. 6A. The SHM myometrial cells used to monitor Gja1 promoter activity do not express PR. In contrast to the artificial PRE and MMTV reporter systems described above, overexpression of PRA or PRB down-regulated the Cx1686-Luc activity in a dose-dependent fashion in SHM cells (Fig. 6B). Progesterone treatment led to further repression of luciferase activity. Overexpression of p54nrb alone had no effect on the activity of Cx1686-Luc. To explore the region within the Gja1 promoter that is responsible for PR-mediated repression, PRA was cotransfected with various mutant Gja1 promoter reporter constructs. PRA inhibited all the deletion mutants of Gja1 promoter (Fig. 6C). The shortest deletion mutant, Cx75-luc, contains two SP-1 sites and one AP-1 site that we previously demonstrated were the important cis-elements for Gja1 transcription (56, 57). Mutation of the AP-1 site, however, abolished the PRA-mediated repression on Gja1 promoter, suggesting that PR may mediate the repressive function through protein interactions with AP-1 transcriptional factors (Fig. 6C). To confirm this hypothesis, we performed immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 6D). SHM cells were transiently transfected with PRA and/or hemagglutinin (HA) c-Jun expression constructs. Cell lysates were precipitated with HA tag-specific antibody and PRA was observed to associate with c-Jun.

Fig. 6.

A, Schematic diagram describes the structure of mouse Gja1 promoter. There are two AP-1 and four SP-1 binding sites marked by their locations relative to the transcription initiation site. The luciferase reporter vectors of Gja1 promoter, its deletion mutations, and AP-1 site mutations were used in panels B and C. B, SHM cells were transfected with Cx1686-luc reporter together with 50 ng and 300 ng of PRA, PRB, and p54nrb vectors as indicated. Cells were treated 24 h after transfection with vehicle (□) or 1 nm progesterone (▪) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Values are shown as means ± sem from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 relative to Cx1686-Luc reporter alone in the absence of progesterone; †, P < 0.01 relative to Cx1686-Luc reporter alone in the presence of progesterone). C, SHM cells were transfected with 200 ng of luciferase reporter vectors together with 100 ng PRA vectors as indicated. Cells were treated 24 h after transfection with vehicle (□) or 1 nm progesterone (▪) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Values are shown as means ± sem from three independent experiments. D, SHM cells were transfected with PRA and or HA c-Jun vectors. Cell lysates were precipitated with HA tag antibody, and the associated proteins were immunoblotted with PR and HA tag antibodies. E, SHM cells were transfected with Cx300-Luc or Cx300m-Luc together with PRA and Flag-p54nrb expression vectors as indicated and treated with vehicle or 1 nm progesterone for 1 h. In vivo DNA-protein interaction assay were performed (as described in Materials and Methods) by control IgG, PR, and Flag tag antibodies. IP, Immunoprecipitation.

Next, we performed in vivo protein-DNA binding assays to determine whether PR and p54nrb can be recruited to the AP-1 region of the Gja1 promoter (Fig. 6E). SHM cells were transfected with PR, Flag-p54nrb, or empty expression vector together with Cx300-Luc or Cx300m-Luc reporter vector and then treated with either vehicle or 1 nm progesterone for 1 h. Cross-linked cell lysates were precipitated with PR and Flag tag antibodies. The primers used in this in vivo protein-DNA assay were designed from the murine sequence as were the Cx300-Luc and Cx300m-Luc. No signal was detected in the absence of the transfected reporter gene, suggesting that the primers do not recognize the hamster Gja1 gene from SHM cells (lanes 1-3). PRA interacts with the Gja1 promoter, and this association was enhanced when the cells were treated with progesterone (lanes 4–5) consistent with our observation in luciferase assays in Fig. 6B. In addition, p54nrb was only recruited to the Gja1 promoter when PR is present, indicating PR and p54nrb form a complex on the Gja1 promoter (lanes 6–9). A greater amount of p54nrb is associated with the Gja1 promoter in the presence of progesterone treatment, in agreement with the enhanced interaction between PR and the Gja1 promoter (lanes 8–9) in the presence of the hormone. Site-directed mutagenesis of the AP-1 site abolished both PRA and p54nrb recruitment (lanes 10 and 11), further supporting our conclusion that the PR-p54nrb complex interacts with the Gja1 promoter through protein-protein association with AP-1 proteins.

p54nrb Regulates PR-mediated repression on Gja1 transcription

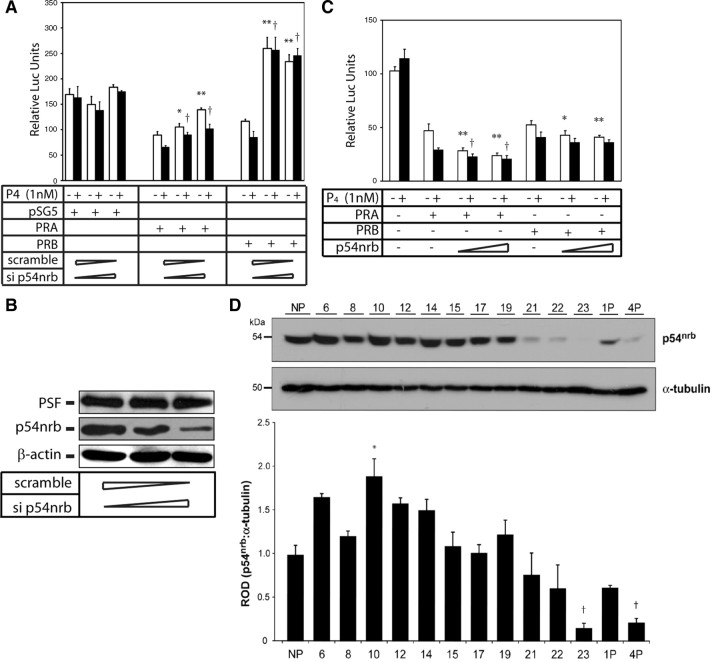

Because both PR and p54nrb can be recruited to the Gja1 promoter, the physiological impact of p54nrb on PR-mediated repression of Gja1 transcription was next investigated. We first explored the role of p54nrb by using small interfering RNA (siRNA) to knock down endogenous p54nrb expression. We observed that decreased expression of p54nrb protein can alleviate both PRA- and PRB-mediated inhibition on Gja1 transcription (Fig. 7A). In the case of the PRB isoform, knockdown of p54nrb even enhanced the luciferase activity 2.5-fold higher than that of scrambled RNA-transfected cells. The different effects of PRA and PRB on Gja1 promoter activity in the presence of p54nrb knockdown may possibly be due to the fact that PRB is able to more efficiently recruit coactivators than PRA. The efficiency of the siRNA knockdown of p54nrb expression was shown by immunoblotting the lysate from cells transfected with either scrambled or siRNA against p54nrb (Fig. 7B). PSF shares significant homology with p54nrb and was used to control for the specificity of siRNA against p54nrb. No changes in PSF protein level were observed in the presence of siRNA against p54nrb. In addition, p54nrb overexpression enhanced both PRA- and PRB-mediated inhibition of Gja1 promoter activity in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 7C). The enhanced repression by overexpression of p54nrb is limited possibly due to the relatively high endogenous levels of p54nrb protein expressed in the cells. Taken together, these data suggest that the inhibitory effect of PR on Gja1 transcription is, in part, through the recruitment of the p54nrb corepressor to the Gja1 promoter.

Fig. 7.

A, 293T cells were transfected with the mixture of scramble and siRNA against p54nrb at different ratios (20:0, 10:10, and 0:20 pmol) in 24-well plates for 24 h. Cells were transfected with Cx1686-Luc, PRA, and PRB for another 24 h, after which cells were then treated with vehicle (□) or 1 nm progesterone (▪) for 24 h. Luciferase activities were measured and calibrated with β-galactosidase activity. Values are shown as means ± sem from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 relative to PR cotransfected with scramble RNA in the absence of progesterone; †, P < 0.01 relative to PR cotransfected with scramble RNA in the presence of progesterone). B, 293T cells were transfected with mixture of scramble and siRNA against p54nrb at different ratios (20:0, 10:10, and 0:20 pmol) in 24-well plates for 72 h. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with PSF, p54nrb, and α-actin antibodies. C, SHM cells were transiently transfected with 200 ng of Cx1686-luc reporter together with 100 ng of PRA or PRB vector and increasing does (200 and 400 ng) of p54nrb vector. Cells were treated 24 h after transfection with either vehicle (□) or 1 nm progesterone (▪) for another 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Values are shown as means ± sem from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 relative to PR cotransfected with Cx1686-Luc in the absence of progesterone; †, P < 0.01 relative to PR co-transfected with Cx1686-Luc in the presence of progesterone). D, Four sets of myometrial tissue were collected from non-pregnant (NP) rat and pregnant rats during gestational days indicated on the x-axis, as well as from 1- and 4-d post-partum (1P, 4P) rats. Lysates were immunoblotted with p54nrb and α-tubulin antibodies. The intensity of p54nrb protein bands was quantified by densitometry and normalized against α-tubulin to give a relative optical density (ROD) value. Bars represent the mean ± sem of each time point. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (*, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.05 relative to NP).

Gestational profile of myometrial p54nrb protein in rat

To explore whether there are changes in p54nrb expression in myometrium that could alter PR signaling during pregnancy, we next used immunoblotting assays to determine the gestational profile of p54nrb protein expression in rat myometrium. Myometrial tissue samples were collected from nonpregnant rats and pregnant rats on gestational d 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 21, 22, and 23 (labor), as well as 1 and 4 d postpartum (n = 4 for each time point) (Fig. 7D). Western blot analysis with a p54nrb-specific antibody revealed that p54nrb expression is relatively high throughout gestation, but exhibited a significant decrease with the approach of labor on d 23 (P < 0.05). After birth, p54nrb was transiently up-regulated (d 1P), and returned to low levels by the fourth day after birth. This gestational profile of myometrial p54nrb protein expression together with data from Figs. 5–7 strongly suggest that decreased expression of p54nrb in myometrium at term pregnancy may alleviate the inhibitory effects of PR on Gja1 promoter activity and allow the derepression of Gja1 transcription.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates, for the first time, that the RNA splicing factor, p54nrb, represses transcriptional activity of PR. The repressor function of p54nrb is mediated through the recruitment of the mSin3A complex to PR independent of the presence of PSF. Furthermore, our data suggest that the decrease in myometrial p54nrb expression at term pregnancy alleviates PR repression of the labor-associated gene, Gja1. Because increased expression of Gja1 is essential for the onset of labor at term (54), we suggest that this derepression induced by decreased p54nrb expression contributes to the initiation of normal term labor.

The molecular mechanism by which p54nrb inhibits PR-mediated transcription initiation is through the recruitment of the mSin3A complex. We showed that PSF and p54nrb recruit mSin3A to the androgen receptor and that, in turn, mSin3A recruits HDACs to inhibit AR-mediated transactivation (47). We propose that p54nrb might also recruit HDACs to PR. The mSin3A-HDAC complex mediates histone deacetylation and chromatin remodeling to produce a transcription-nonpermissive environment. HDACs have also been reported to reverse lysine acetylation of various nonhistone proteins located in the nucleus and the cytoplasm (58). The association of the mSin3A/HDAC to the splicing factor p54nrb raises the interesting possibility that these regulators of transcription initiation may also be functional in other nuclear processes such as transcription elongation, RNA splicing, or transcription termination.

This activity of p54nrb as a corepressor adds to the multiple roles of this protein in gene transcription. The multifunctional property of p54nrb is attributed to its affinity for both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA/RNA, and its ability to associate with multiple proteins or protein complexes. As yet, it is not clear whether these multifunctional protein complexes are associated with each other or exist as separate protein complexes that each contain p54nrb as a common component. In order for p54nrb to participate in several simultaneous nuclear processes, we speculate that it might be shuffled between complexes, being dynamically recruited to one protein complex (e.g. the transcription initiation complex) and then released to join another functional protein complex (such as the RNA splicesome).

Whereas progesterone is essential for the maintenance of pregnancy and hence the reproductive survival of mammalian species, the specific genes directly targeted by progesterone and the mechanisms by which transcription of these genes is regulated are poorly understood. We previously reported that in animals the myometrial expression of genes that contribute to the initiation of labor (including Gja1, oxytocin receptor, and FP receptor) is increased in association with the fall of plasma progesterone at term. The expression of these genes is prematurely increased by administration of the progesterone antagonist, RU486, but is blocked by administration of exogenous progesterone (3, 8, 59, 60). These data highlight the repressive effects of PR on the transcription of these labor genes. Several mechanisms could contribute to PR-mediated repression of target gene transcription, including that 1) PR directly binds target gene promoters to interfere with other transcription factors that are essential for the promoter to achieve optimum transcriptional activation; 2) PR binds other transcriptional activators and thereby blocks coactivator recruitment to target gene promoters; and 3) through an association of PR to target gene promoters either directly or indirectly through other transcription factors, PR might further recruit a transcriptional corepressor complex to inhibit the transcription rate of PR target genes. These mechanisms could function individually or cooperatively. PR was reported to impair IL-1β-induced Cox-2 expression by interfering with nuclear factor-κB p65 binding to the COX-2 promoter (61). We show here that PR recruits p54nrb corepressor to the AP-1 transcriptional factor and inhibits transcription of the key labor gene, Gja1. This conclusion is based on the following findings: 1) PR interacts with p54nrb, which further recruits mSin3A to PR target gene promoter (Figs. 3 and 5); 2) PR mediates transcriptional repression that is dependent on the presence of the AP-1 binding site in the Gja1 promoter (Fig. 6, B and C); 3) PR interacts with c-Jun, and the recruitment of the PR-p54nrb complex onto the Gja1 promoter is dependent upon the AP-1 binding site (Fig. 6, D and E); and 4) knockdown of p54nrb expression alleviates, whereas p54nrb overexpression enhances, PR-mediated suppression on Gja1 promoter activity (Fig. 7, A–C). These observations support a model in which PR suppresses target genes transcription through interactions with AP-1 proteins and the further recruitment of transcriptional corepressors to the target gene promoters.

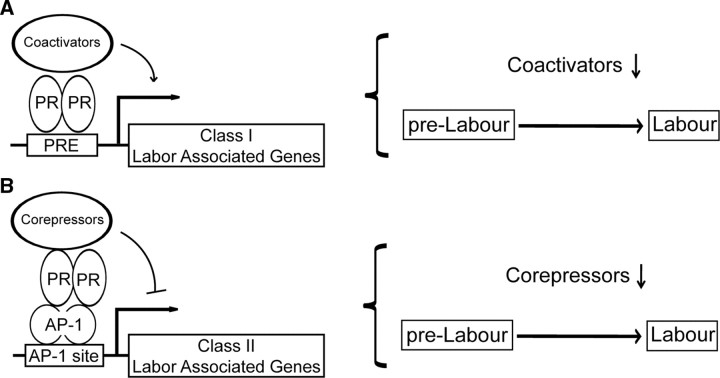

Importantly, we provide in vivo data that p54nrb protein levels within the myometrium are high throughout pregnancy (enhancing PR-mediated suppression of labor-gene transcription), and significantly fall at the end of pregnancy, allowing a derepression of the labor gene expression. We have previously reported that genetic ablation of Gja1 in myometrial smooth muscle cells in mice delays parturition, emphasizing the requirement for increased expression of this gene for normal labor (54). Data presented here suggest that p54nrb plays a critical role in the initiation of labor through the inhibition of PR-mediated repression of Gja1 transcription. We therefore propose two models, in which altered expression of PR coregulators could modulate labor-associated gene expression and contribute to the initiation of labor, as depicted in Fig. 8. The first model (Fig. 8A) is supported by the study showing that there are decreases in expression of PR coactivators at term. This change would reduce the expression of labor-associated genes that are positively regulated by PR (12). The second model is supported by our current study showing that decreased expression of PR corepressors, such as p54nrb, contribute to increased expression of labor-associated genes (such as Gja1 and possibly other labor genes) that are suppressed by PR (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Two models are proposed by which decrease in expression of PR coregulators contributes to the initiation of labor. A, In class I labor-associated genes, PR binds to the PRE directly on the promoters and either up- or down-regulates gene transcription. Decrease in expression of PR coactivators blocks this PR action at term to change the levels of transcription of these labor-associated genes. B, In class II labor-associated genes, PR binds AP-1 and further recruits corepressors to the promoters to suppress gene transcription. Decrease in expression of PR corepressors also results in blockade of PR-suppressive action at term, and higher levels of the class II labor-associated genes are transcribed.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction

All recombinant DNA analyses were performed according to standard procedures (54). Flag-p54nrb, PRA, PRB, mSin3A expression vectors, and pCx1686-luc and its deletion mutation reporter vectors were described previously (31, 46, 56, 57, 62). HA c-Jun expression vector was generously provided by Dr. Dirk Bohmann (University of Rochester, Rochester, MN). Using Flag-p54nrb as the template, a series of deletion mutations (p54nrb aa 1–471, 75–471, 149–471, 229–471, and 420–471) were generated by PCR with a 5′-primer containing an EcoRI site and an ATG start codon and 3′-primer containing a TGA stop codon and a SalI site using high-fidelity Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR fragments were then inserted into pM and pGEX-5X-2 vectors at the EcoRI and SalI sites. The veracity of all PCR-generated fragments was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Expressed proteins were also detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies.

Cell culture and transient transfection

Hamster myometrial cell line (SHM) and the immortalized human embryonic kidney cell line (293T) were maintained in DMEM, and breast cancer cell line (T47D) were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium, plus 5% fetal calf serum (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) as described elsewhere (46, 47). For experiments involving steroid exposure, the medium was substituted with phenol red-free DMEM containing 5% charcoal-treated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT). Transfection was performed using Exgen500 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Fermentas, Inc., Glen Burnie, MD). Cell lysates collected in lysis buffer (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) were used for the luciferase and β-galactosidase activity assays, respectively. Luciferase activity was determined using the luciferin reagent (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transfection efficiency was normalized to β-galactosidase or Renilla luciferase activities.

RNA interference

The siRNA targeting human p54nrb was synthesized by Invitrogen. We use the same sequence as shown (63): sense 5′-CAG GCG AAG UCU UCA UUC A dTdT-3′, antisense 5′-UGA AUG AAG ACU UCG CCU G dTdT-3′. The control scramble RNA is from Invitrogen (catalog no. 12935-300). Control scramble and siRNA against p54nrb were transfected in 293T cells using lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer’s instructions. We use shRNA to knock down endogenous PSF expression as reported previously (47).

Coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in TNET buffer [50 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1% Triton] plus protease inhibitor cocktail. Cell lysates precleared with control IgG (Santa Cruz Biochemicals, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) were incubated with specific antibodies overnight at 4 C, followed by the addition of protein A/G (Santa Cruz) for another 2 h at 4 C. Resins were washed with TNET buffer (contains 500 mm NaCl) and eluted with Laemmli buffer, boiled, and centrifuged. The supernatant was separated by protein PAGE gel, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and blotted by specific antibodies. Antibodies used in these experiments are for PR (AB-52 and H190, Santa Cruz), Flag tag (M2 antibody, Sigma), HA tag (F-7, Santa Cruz), p54nrb (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, CA), PSF (B92, Sigma), Gal4 DBD (sc-577, Santa Cruz), and mSin3A (K-20, Santa Cruz).

GST pull-down assay

GST pull-down assay was performed as previously described (62). PRB and mSin3A were expressed and [35S]methionine labeled by the TNT T7-coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). Labeled proteins were incubated with GST and p54nrb fusion proteins. After extensive wash with TENT (contains 500 mm NaCl) buffer, associated proteins were recovered by Laemmli buffer and separated on protein PAGE gels. Gels were treated with Enhancer (New England Nuclear), dried, and analyzed by autoradiography.

In vivo protein-DNA interaction assay

In vivo protein-DNA interaction assay was performed with modifications of the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay as previously described (64, 65). 293T cells were transfected with luciferase reporter vector as well as PR and p54nrb vectors for 24 h before exposure to either vehicle or 1 nm progesterone for 1 h. Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at 37 C and sonicated in lysis buffer (1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mm EDTA, and 50 mm Tris 8.0, plus protease inhibitor cocktail). After centrifugation, 10 μl of the supernatant was used as input, and the remaining lysate was subjected to precipitation with antibodies against PR, p54nrb, or mSin3A. After washing, associated protein-DNA complexes were eluted and heated to reverse the formaldehyde cross-link. DNA fragments were extracted with the QIAGEN PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Chatsworth CA), and used as templates to perform PCR. The primers used to amplify PREs in MMTV promoter were: forward, 5′-TAT GGT TAC AAA CTG TTC TTA AAA CGA GGA TG-3′; and reverse, 5′-GCA AGT TTA CTC AAA AAT CAG CAC TCT TT-3′. The PCR amplified the region corresponding to position 1038-1228 bp (GenBank accession no. Vo1175). The size of the PCR product was 190 bp. The primers used to amplify AP-1 region in the Gja1 promoter were: forward, 5′-TTT CTC CTA GCC CCT CCT TC-3′; and reverse, 5′-TCA AAG TCT GCT GCT GTT GG-3′. The PCR amplified the region corresponding to position 1618-1771 bp (GenBank accession no. U17892). The size of the PCR product was 153 bp.

Gel shift assay

Gel shift assays were performed as previously described (46, 47). GST or GST-PR DBD was purified by using the glutathione sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Flag-p54nrb was purified by the M2-sephoroase beads (Sigma) using 293T cell lysates expressing Flag-p54nrb as previously described (46, 47). Double-strand synthetic oligonucleotide probes containing a palindromic consensus PRE (5′-AGC TTA GAA CAC AGT GTT CTC TAG AG-3′) were labeled with [γ-32P]-ATP. Binding reactions were performed with 0.5ng of labeled PRE and purified GST or GST-PR DBD together with or without Flag-p54nrb. The total volume is 20 μl in 1× reaction buffer [5% glycerol, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 5 mm EDTA, 250 mm KCl, 100 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 μg of polydeoxyinosinic deoxycytidylic acid, 25 mm MgCl2, 1 mg/ml BSA, 1 μg of salmon sperm DNA, 0.05% Triton X-100]. The binding reaction was allowed to proceed for 20 min at room temperature before loading onto 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Tissue collection and protein extraction

Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratories, St. Constance, Canada) were housed individually under standard environmental conditions (12-h light, 12-h dark cycle) and fed Purina Rat Chow (Ralston Purina, St. Louis, MO) and water ad libitum. Female virgin rats were mated with male Wistar rats. Day one of gestation was designated as the day a vaginal plug was observed. The average time of delivery under these conditions was during the morning of d 23. Our criteria for labor are based on delivery of at least one pup. All animal procedures received prior approval by the Institutional Animal Care Committee.

Rats were killed by carbon dioxide inhalation, and myometrial samples were collected on gestations d 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 21, 22, and 23, or 1 and 4 d postpartum (1PP and 4PP). Tissue was collected at 0010 h on all days, except for laboring animals (d23L) when samples were collected once the animal had delivered at least one pup. Rat myometrial tissues were placed into ice-cold PBS, bisected longitudinally, and dissected away from both pups and placentas. The endometrium was carefully removed from the myometrial tissue by mechanical scraping on ice. We have previously shown that this removes the entire luminal epithelium and the majority of the endometrial stroma (66, 67, 68, 69). The myometrial tissue was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 C. Myometrial protein was extracted from frozen myometrial tissue as described elsewhere (66, 67, 68, 69) and immunoblotted with p54nrb and α-tubulin antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SigmaStat version 1.01 (Jandel Corp., San Rafael, CA). Four complete sets of gestational profiles (p54nrb vs. α-tubulin) were analyzed by immunoblotting, and the data were subjected to a one-way ANOVA followed by pair-wise multiple comparison procedures (Student-Newman-Keuls method) to determine differences between groups, with the level of significance for comparison set at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Anna Dorogin (Lye Lab, Mount Sinai Hospital) for her technical support and members from Lye laboratory for the discussion of this project.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Coregulators: Sin3A | p54nrb;

Ligands: Progesterone;

Nuclear Receptors: PR.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Operating Grant from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-42378).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online May 7, 2009

Abbreviations: aa, Amino acids; AP-1, activator protein 1; DBD, DNA-binding domain; Gja1, Connexin 43 gene; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; HA, hemagglutinin; HDAC, histone deacetylase; MMTV, mouse mammary tumor virus; p54nrb, non-POU-domain-containing, octamer binding protein; PR, progesterone receptor; PRE, progesterone response element; PSF, PTB-associated RNA splicing factor; RRM, RNA recognition motif; scrPSF, scrambled PSF; SHM, hamster myometrial cell line; shPSF, short hairpin PSF; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

References

- 1.Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ2000. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev 21:514–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesiano S, Welsh TN2007. Steroid hormone control of myometrial contractility and parturition. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18:321–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piersanti M, Lye SJ1995. Increase in messenger ribonucleic acid encoding the myometrial gap junction protein, connexin-43, requires protein synthesis and is associated with increased expression of the activator protein-1, c-fos. Endocrinology 136:3571–3578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue Y, Sperelakis N1991. Gestational change in Na+ and Ca2+ channel current densities in rat myometrial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 260:C658–C663 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Soloff MS, Beauregard G, Potier M1988. Determination of the functional size of oxytocin receptors in plasma membranes from mammary gland and uterine myometrium of the rat by radiation inactivation. Endocrinology 122:1769–1772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senior J, Sangha R, Baxter GS, Marshall K, Clayton JK1992. In vitro characterization of prostanoid FP-, DP-, IP- and TP-receptors on the non-pregnant human myometrium. Br J Pharmacol 107:215–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ou CW, Orsino A, Lye SJ1997. Expression of connexin-43 and connexin-26 in the rat myometrium during pregnancy and labor is differentially regulated by mechanical and hormonal signals. Endocrinology 138:5398–5407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell JA, Shynlova O, Langille BL, Lye SJ2004. Mechanical stretch and progesterone differentially regulate activator protein-1 transcription factors in primary rat myometrial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287:E439–E445 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.McKeown KJ, Challis JR, Small C, Adamson L, Bocking AD, Fraser M, Rurak D, Riggs KW, Lye SJ2000. Altered fetal pituitary-adrenal function in the ovine fetus treated with RU486 and meloxicam, an inhibitor of prostaglandin synthase-II. Biol Reprod 63:1899–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kastner P, Krust A, Turcotte B, Stropp U, Tora L, Gronemeyer H, Chambon P1990. Two distinct estrogen-regulated promoters generate transcripts encoding the two functionally different human progesterone receptor forms A and B. EMBO J 9:1603–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tora L, Gronemeyer H, Turcotte B, Gaub MP, Chambon P1988. The N-terminal region of the chicken progesterone receptor specifies target gene activation. Nature 333:185–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giangrande PH, McDonnell DP1999. The A and B isoforms of the human progesterone receptor: two functionally different transcription factors encoded by a single gene. Recent Prog Horm Res 54:291–313; discussion 313–294 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vegeto E, Shahbaz MM, Wen DX, Goldman ME, O’Malley BW, McDonnell DP1993. Human progesterone receptor A form is a cell- and promoter-specific repressor of human progesterone receptor B function. Mol Endocrinol 7:1244–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraus WL, Weis KE, Katzenellenbogen BS1995. Inhibitory cross-talk between steroid hormone receptors: differential targeting of estrogen receptor in the repression of its transcriptional activity by agonist- and antagonist-occupied progestin receptors. Mol Cell Biol 15:1847–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Condon JC, Hardy DB, Kovaric K, Mendelson CR2006. Up-regulation of the progesterone receptor (PR)-C isoform in laboring myometrium by activation of nuclear factor-κB may contribute to the onset of labor through inhibition of PR function. Mol Endocrinol 20:764–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merlino AA, Welsh TN, Tan H, Yi LJ, Cannon V, Mercer BM, Mesiano S2007. Nuclear progesterone receptors in the human pregnancy myometrium: evidence that parturition involves functional progesterone withdrawal mediated by increased expression of progesterone receptor-A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:1927–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Condon JC, Jeyasuria P, Faust JM, Wilson JW, Mendelson CR2003 A decline in the levels of progesterone receptor coactivators in the pregnant uterus at term may antagonize progesterone receptor function and contribute to the initiation of parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:9518–9523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandit S, Wang D, Fu XD2008. Functional integration of transcriptional and RNA processing machineries. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20:260–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonard DM, O’Malley BW2007. Nuclear receptor coregulators: judges, juries, and executioners of cellular regulation. Mol Cell 27:691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornblihtt AR, de la Mata M, Fededa JP, Munoz MJ, Nogues G2004 Multiple links between transcription and splicing. RNA 10:1489–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auboeuf D, Batsché E, Dutertre M, Muchardt C, O’Malley BW2007 Coregulators: transducing signal from transcription to alternative splicing. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18:122–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonard DM, Lanz RB, O’Malley BW2007. Nuclear receptor coregulators and human disease. Endocr Rev 28:575–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lonard DM, O’Malley BW2006. The expanding cosmos of nuclear receptor coactivators. Cell 125:411–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenfeld MG, Lunyak VV, Glass CK2006. Sensors and signals: a coactivator/corepressor/epigenetic code for integrating signal-dependent programs of transcriptional response. Genes Dev 20:1405–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermanson O, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG2002. Nuclear receptor coregulators: multiple modes of modification. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleischer TC, Yun UJ, Ayer DE2003. Identification and characterization of three new components of the mSin3A corepressor complex. Mol Cell Biol 23:3456–3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassig CA, Fleischer TC, Billin AN, Schreiber SL, Ayer DE1997. Histone deacetylase activity is required for full transcriptional repression by mSin3A. Cell 89:341–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laherty CD, Billin AN, Lavinsky RM, Yochum GS, Bush AC, Sun JM, Mullen TM, Davie JR, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Ayer DE, Eisenman RN1998 SAP30, a component of the mSin3 corepressor complex involved in N-CoR-mediated repression by specific transcription factors. Mol Cell 2:33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiio Y, Rose DW, Aur R, Donohoe S, Aebersold R, Eisenman RN2006 Identification and characterization of SAP25, a novel component of the mSin3 corepressor complex. Mol Cell Biol 26:1386–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Iratni R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D1997 Histone deacetylases and SAP18, a novel polypeptide, are components of a human Sin3 complex. Cell 89:357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heinzel T, Lavinsky RM, Mullen TM, Söderstrom M, Laherty CD, Torchia J, Yang WM, Brard G, Ngo SD, Davie JR, Seto E, Eisenman RN, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG1997. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387:43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baurén G, Wieslander L1994. Splicing of Balbiani ring 1 gene pre-mRNA occurs simultaneously with transcription. Cell 76:183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fong N, Bentley DL2001. Capping, splicing, and 3′ processing are independently stimulated by RNA polymerase II: different functions for different segments of the CTD. Genes Dev 15:1783–1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosonina E, Ip JY, Calarco JA, Bakowski MA, Emili A, McCracken S, Tucker P, Ingles CJ, Blencowe BJ2005. Role for PSF in mediating transcriptional activator-dependent stimulation of pre-mRNA processing in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 25:6734–6746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang G, Taneja KL, Singer RH, Green MR1994. Localization of pre-mRNA splicing in mammalian nuclei. Nature 372:809–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emili A, Shales M, McCracken S, Xie W, Tucker PW, Kobayashi R, Blencowe BJ, Ingles CJ2002. Splicing and transcription-associated proteins PSF and p54nrb/nonO bind to the RNA polymerase II CTD. RNA 8:1102–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auboeuf D, Dowhan DH, Li X, Larkin K, Ko L, Berget SM, O’Malley BW2004. CoAA, a nuclear receptor coactivator protein at the interface of transcriptional coactivation and RNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol 24:442–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowhan DH, Hong EP, Auboeuf D, Dennis AP, Wilson MM, Berget SM, O’Malley BW2005. Steroid hormone receptor coactivation and alternative RNA splicing by U2AF65-related proteins CAPERα and CAPERβ. Mol Cell 17:429–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monsalve M, Wu Z, Adelmant G, Puigserver P, Fan M, Spiegelman BM2000. Direct coupling of transcription and mRNA processing through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Mol Cell 6:307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathur M, Tucker PW, Samuels HH2001. PSF is a novel corepressor that mediates its effect through Sin3A and the DNA binding domain of nuclear hormone receptors. Mol Cell Biol 21:2298–2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sewer MB, Nguyen VQ, Huang CJ, Tucker PW, Kagawa N, Waterman MR2002. Transcriptional activation of human CYP17 in H295R adrenocortical cells depends on complex formation among p54(nrb)/NonO, protein-associated splicing factor, and SF-1, a complex that also participates in repression of transcription. Endocrinology 143:1280–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urban RJ, Bodenburg Y2002. PTB-associated splicing factor regulates growth factor-stimulated gene expression in mammalian cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283:E794–E798 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Hallier M, Tavitian A, Moreau-Gachelin F1996. The transcription factor Spi-1/PU. 1 binds RNA and interferes with the RNA-binding protein p54nrb. J Biol Chem 271:11177–11181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urban RJ, Bodenburg YH, Wood TG2002. NH2 terminus of PTB-associated splicing factor binds to the porcine P450scc IGF-I response element. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283:E423–E427 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Iacobazzi V, Infantino V, Costanzo P, Izzo P, Palmieri F2005. Functional analysis of the promoter of the mitochondrial phosphate carrier human gene: identification of activator and repressor elements and their transcription factors. Biochem J 391:613–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong X, Shylnova O, Challis JR, Lye SJ2005. Identification and characterization of the protein-associated splicing factor as a negative co-regulator of the progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem 280:13329–13340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong X, Sweet J, Challis JR, Brown T, Lye SJ2007. Transcriptional activity of androgen receptor is modulated by two RNA splicing factors, PSF and p54nrb. Mol Cell Biol 27:4863–4875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong B, Horowitz DS, Kobayashi R, Krainer AR1993. Purification and cDNA cloning of HeLa cell p54nrb, a nuclear protein with two RNA recognition motifs and extensive homology to human splicing factor PSF and Drosophila NONA/BJ6. Nucleic Acids Res 21:4085–4092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng R, Dye BT, Pérez I, Barnard DC, Thompson AB, Patton JG2002 PSF and p54nrb bind a conserved stem in U5 snRNA. RNA 8:1334–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shav-Tal Y, Zipori D2002. PSF and p54(nrb)/NonO–multi-functional nuclear proteins. FEBS Lett 531:109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kameoka S, Duque P, Konarska MM2004. p54(nrb) associates with the 5′ splice site within large transcription/splicing complexes. EMBO J 23:1782–1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lindsey LA, Crow AJ, Garcia-Blanco MA1995. A mammalian activity required for the second step of pre-messenger RNA splicing. J Biol Chem 270:13415–13421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gozani O, Patton JG, Reed R1994. A novel set of spliceosome-associated proteins and the essential splicing factor PSF bind stably to pre-mRNA prior to catalytic step II of the splicing reaction. EMBO J 13:3356–3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Döring B, Shynlova O, Tsui P, Eckardt D, Janssen-Bienhold U, Hofmann F, Feil S, Feil R, Lye SJ, Willecke K2006. Ablation of connexin43 in uterine smooth muscle cells of the mouse causes delayed parturition. J Cell Sci 119:1715–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrocelli T, Lye SJ1993. Regulation of transcripts encoding the myometrial gap junction protein, connexin-43, by estrogen and progesterone. Endocrinology 133:284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen ZQ, Lefebvre D, Bai XH, Reaume A, Rossant J, Lye SJ1995. Identification of two regulatory elements within the promoter region of the mouse connexin 43 gene. J Biol Chem 270:3863–3868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitchell JA, Lye SJ2005. Differential activation of the connexin 43 promoter by dimers of activator protein-1 transcription factors in myometrial cells. Endocrinology 146:2048–2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hess-Stumpp H2005. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and cancer: from cell biology to the clinic. Eur J Cell Biol 84:109–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Orsino A, Taylor CV, Lye SJ1996 Connexin-26 and connexin-43 are differentially expressed and regulated in the rat myometrium throughout late pregnancy and with the onset of labor. Endocrinology 137:1545–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lye SJ, Nicholson BJ, Mascarenhas M, MacKenzie L, Petrocelli T1993 Increased expression of connexin-43 in the rat myometrium during labor is associated with an increase in the plasma estrogen:progesterone ratio. Endocrinology 132:2380–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hardy DB, Janowski BA, Chen CC, Mendelson CR2008. Progesterone receptor inhibits aromatase and inflammatory response pathways in breast cancer cells via ligand-dependent and ligand-independent mechanisms. Mol Endocrinol 22:1812–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dong X, Challis JR, Lye SJ2004. Intramolecular interactions between the AF3 domain and the C-terminus of the human progesterone receptor are mediated through two LXXLL motifs. J Mol Endocrinol 32:843–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amelio AL, Miraglia LJ, Conkright JJ, Mercer BA, Batalov S, Cavett V, Orth AP, Busby J, Hogenesch JB, Conkright MD2007. A coactivator trap identifies NONO (p54nrb) as a component of the cAMP-signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:20314–20319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.An BS, Selva DM, Hammond GL, Rivero-Muller A, Rahman N, Leung PC2006 Steroid receptor coactivator-3 is required for progesterone receptor trans-activation of target genes in response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone treatment of pituitary cells. J Biol Chem 281:20817–20824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Q, Li W, Liu XS, Carroll JS, Jänne OA, Keeton EK, Chinnaiyan AM, Pienta KJ, Brown M2007. A hierarchical network of transcription factors governs androgen receptor-dependent prostate cancer growth. Mol Cell 27:380–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shynlova O, Tsui P, Dorogin A, Chow M, Lye SJ2005. Expression and localization of α-smooth muscle and γ-actins in the pregnant rat myometrium. Biol Reprod 73:773–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shynlova O, Tsui P, Dorogin A, Langille BL, Lye SJ2007. The expression of transforming growth factor β in pregnant rat myometrium is hormone and stretch dependent. Reproduction 134:503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shynlova O, Tsui P, Dorogin A, Langille BL, Lye SJ2007. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins define specific phases of myometrial differentiation during pregnancy in the rat. Biol Reprod 76:571–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shynlova O, Tsui P, Dorogin A, Lye SJ2008. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL-2) integrates mechanical and endocrine signals that mediate term and preterm labor. J Immunol 181:1470–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]