Abstract

To repress the expression of target genes, the unliganded nuclear receptor generally recruits the silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT)/nuclear receptor corepressor via its direct association with the conserved motif within bipartite nuclear receptor-interaction domains (IDs) of the corepressor. Here, we investigated the involvement of the SMRT corepressor in transcriptional repression by the unliganded vitamin D receptor (VDR). Using small interference RNA against SMRT in human embryonic kidney 293 cells, we demonstrated that SMRT is involved in the repression of the VDR-target genes, osteocalcin and vitamin D3 24-hydroxylase in vivo. Consistent with this, VDR and SMRT are recruited to the vitamin D response element of the endogenous osteocalcin promoter in the absence of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. To address the involvement of the VDR-specific interaction of SMRT in this repression, we identified the molecular determinants of the interaction between VDR and SMRT. Interestingly, VDR specifically interacts with ID1 of the SMRT/nuclear receptor corepressor and that ID1 is required for their stable interaction. We also identified specific residues in the SMRT-ID1 that are required for VDR binding, using the one- plus two-hybrid system, a novel genetic selection method for specific missense mutations that disrupt protein-protein interactions. These mutational studies revealed that VDR interaction requires a wide range of the residues within and outside the extended helix motif of SMRT-ID1. Notably, SMRT mutants defective in the VDR interaction were also defective in the repression of endogenous VDR-target genes, indicating that the SMRT corepressor is directly involved in the VDR-mediated repression in vivo via an ID1-specific interaction with the VDR.

The SMRT corepressor is directly involved in the VDR-mediated repression of target genes in vivo via a specific interaction between SMRT-ID1 and the VDR.

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are ligand-dependent transcription factors that play important roles in development, cell differentiation, metabolism, and carcinogenesis (1, 2, 3). The vitamin D receptor (VDR) is a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily and binds the biologically active form of vitamin D [1α,25(OH)2D3] as a ligand with high affinity (4). To regulate transcription of target genes, the VDR forms a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR). This heterodimer binds to specific sequences, known as vitamin D-response elements (VDREs), generally located in the promoter regions of target genes (5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

The osteocalcin (OC) gene encodes a γ-carboxylated calcium-binding protein the expression of which is largely restricted to the osteoblast (10, 11), and two OC genes (mOG1 and mOG2) have been identified in the mouse (12). OC gene expression is regulated by various calcitropic hormones, including vitamin D (D3) (13, 14) and glucocorticoids (15, 16), and a number of transcription factors control OC expression by binding to the responsive elements in its promoter region (17). One of the factors that control OC expression is VDR. A VDRE is located in the OC promoter and functions as an enhancer to increase OC gene transcription (14, 18). Another well-known target of VDR is the vitamin D3 24-hydroxylase (CYP24) gene, which encodes a mitochondrial cytochrome P450 that hydroxylates D3 and other vitamin D derivatives at position 24 (19, 20). Two DR3-type VDREs are located in the CYP24 promoter and mediate VDR-dependent activation by the D3 ligand (21, 22, 23).

As with other steroid receptors, ligand binding to the VDR appears to drive conformational changes within the ligand-binding domain (LBD), creating a binding surface for coactivators that enhance the transcription rate (24). A number of coactivators have been described, including steroid receptor coactivators and the VDR-interacting protein (DRIP, also called TRAP and ARC) complex (25, 26, 27). In the absence of ligand, NRs recruit corepressor proteins such as the nuclear receptor corepressor (N-CoR) and silencing mediator for the retinoid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT), which subsequently recruit histone deacetylases (HDACs) to repress transcription of target genes (28, 29). The VDR has been shown to have intrinsic repressive activity via interaction with various corepressor proteins, such as N-CoR/SMRT, Alien, and Hairless (30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of these interactions are largely unknown.

N-CoR and SMRT are expressed ubiquitously and modulate the transcriptional activity of a wide range of transcription factors (36, 37). Three independent autonomous repression domains, located in the N-terminal regions of N-CoR and SMRT, are responsible for the physical interaction with several HDACs to activate repressive functions (38, 39). Conserved NR-interaction domains (IDs), located in the C-terminal regions, mediate direct interactions with unliganded NRs. Whereas SMRT has bipartite IDs (ID1 and ID2), N-CoR has a third ID (ID3) upstream of the bipartite IDs, which interacts specifically with the thyroid hormone receptor (TR) (40, 41, 42). The corepressor-NR (CoRNR) box (L/IXXI/VI) and the related extended helix motif (LXXI/HIXXXI/L) have been identified within each ID of the corepressors as the molecular determinants required for NR interactions (43, 44, 45). The latter motif is believed to form an extended α-helix and to bind to a NR-LBD surface that is composed of residues in helices 3, 4, and 5 and overlaps the same hydrophobic pocket that binds the LXXLL motif of the coactivators. This model has been confirmed by the crystal structure of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α in complex with a SMRT-ID2-derived peptide and an antagonist (46). Interestingly, NRs can distinguish corepressors and IDs for specific interactions, showing corepressor preference (N-CoR vs. SMRT) or ID preference (ID1 vs. ID2) (47). For example, the RevErb and retinoic acid receptor (RAR) interact with ID1 of N-CoR/SMRT, whereas the RXR and liver X receptor interact primarily with ID2 of N-CoR/SMRT (48, 49, 50). As mentioned above, the TR preferentially recruits N-CoR via its direct binding to ID3, which is absent in SMRT (40, 41, 42). In the case of the VDR, interaction with IDs of the N-CoR variant RIP13Δ1 has been reported (35) and the structural model for the VDR-LBD complexed with a N-CoR-ID2 (N2) peptide and an antagonist ZK168281 has been proposed based on molecular dynamics simulations (31). However, compared with other NRs, the molecular determinants of the interaction between the corepressor and unliganded VDR are poorly understood.

Loss-of-interaction mutants are essential for determining the functional significance and molecular basis of interactions between NRs and coregulators. For this purpose, we recently devised a novel yeast genetic-screening method, the one- plus two-hybrid system, which efficiently selects missense mutations that disrupt physical interaction with a given partner (51). This system is comprised of dual reporter systems: a one-hybrid system is used first to positively select missense mutants from a randomly generated mutant library, and a two-hybrid reporter system is used for the second screening of interaction-defective mutants among the isolated missense mutants. Using this method, we have successfully characterized the interactions between unliganded NRs and the conserved motifs within N-CoR-IDs (51).

In this report, we demonstrate that VDR displays ID1 and SMRT preferences for corepressor interactions. Using the one- plus two-hybrid system, we have found that VDR interaction requires a wide range of residues within and outside the extended helix motif of SMRT-ID1 (S1). Functional analyses of VDR-specific SMRT mutants revealed that the SMRT corepressor is directly involved in the VDR-mediated repression of OC and CYP24 transcription via an ID1-specific interaction with VDR.

Results

Involvement of SMRT corepressor in the repression of VDR-target genes in vivo

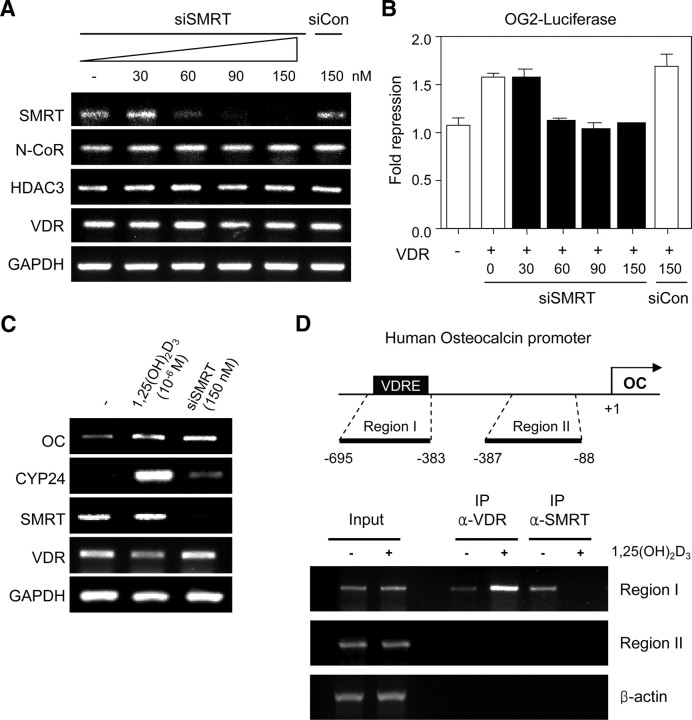

The VDR has been shown to interact with various corepressors, such as N-CoR/SMRT and Alien, providing the molecular basis for the intrinsic repressive activity of the VDR (30, 31, 35). However, the reported weak interaction between VDR and N-CoR/SMRT (52, 53) and the lack of a biological relevance for these interactions suggest that N-CoR/SMRT may not be the physiological corepressor of VDR in vivo. Rather, Hairless corepressor has been shown to be directly involved in VDR-mediated transcriptional repression to maintain hair follicle homeostasis (32, 33, 34). To address whether N-CoR/SMRT acts as a potent corepressor of VDR in vivo, we first examined mRNA levels of VDR-target genes by semiquantitative RT-PCR after knocking down expression of the corepressor. For this purpose, we used small interference RNA (siRNA) against SMRT (siSMRT), because it was reported that the interaction of VDR with SMRT was stronger than that with N-CoR in the mammalian two-hybrid assay (53). As shown in Fig. 1A, the treatment of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells with increasing amounts of siSMRT resulted in reduced levels of SMRT mRNA. At a concentration of 60 nm, the SMRT mRNA level was reduced by more than 70% and at 150 nm, SMRT mRNA expression was completely abolished. In contrast, mRNA levels of N-CoR, HDAC3, VDR, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) genes remained unchanged under these conditions. Transfection with nontargeting siRNA (siCon) had no effect on SMRT expression. To investigate the functional consequences by knocking down SMRT expression, we employed a reporter gene assay using OG2-LUC plasmid. This construct contains the 1.3-kb promoter region of the mouse osteocalcin gene 2 (OG2), a well-known target of VDR. After treating HEK293 cells with increasing concentrations of siSMRT, the cells were transfected with the VDR expression plasmid along with the OG2-luciferase reporter plasmid. Even though VDR expression resulted in only a 1.6-fold repression of reporter gene expression, this effect was consistently reproduced by several repeated experiments under this assay condition (see Discussion). Interestingly, treatment with siSMRT completely abolished this repressive effect of VDR at a concentration of 60 nm or higher (Fig. 1B), which correlates well with the effect of siSMRT on SMRT expression (Fig. 1A). In contrast, nontargeting siRNA had no effect on VDR-mediated repression of the reporter gene.

Fig. 1.

Involvement of SMRT in the transcriptional repression of VDR-target genes. A, mRNA levels of SMRT and related genes after siRNA treatments. After HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated concentrations of siRNA for human SMRT (siSMRT) or nontargeting siRNA (siCon), mRNA expression levels from SMRT, N-CoR, HDAC3, VDR, and GAPDH genes were analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. B, The effect of siSMRT on VDR-mediated repression of OG2-luciferase gene expression. HEK293 cells were transfected with the OG2-luciferase reporter (200 ng/well) and pcDNA3-VDR full-length (fl), the expression plasmid for human VDR (100 ng/well). After 24 h, siSMRT or siCon was subsequently transfected at the indicated concentration, and luciferase activities were assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Data are represented as the fold repression over the value obtained with the reporter plasmid alone. The results are the means ± se values obtained from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate. C, The effect of the siSMRT on the transcription of the VDR-target genes, OC and CYP24. HEK293 cells were transfected with siSMRT in the absence of D3 or treated with 10−6 m D3. After 24 h, mRNA levels from OC, CYP24, VDR, and SMRT genes were measured by RT-PCR. mRNA from the GAPDH gene served as the loading control. D, Occupancy of the VDRE region of the endogenous OC gene by VDR and SMRT proteins in the absence of D3. Upper panel, Schematics of the human OC promoter region. VDRE is indicated as a black box. Two regions corresponding to a VDRE (region I) and a proximal promoter region without VDRE (region II) were selected for PCR. +1 denotes the transcription start site. Lower panel, ChIP assays were performed with HEK293 cells cultured in the absence or presence of 10−8 m D3 ligand. Specific primer sets were used to detect the indicated VDRE (region I) or proximal promoter (region II) regions of the OC promoter. The β-actin gene (exon 4) was used as a negative control. IP, Immunoprecipitation.

Next, we examined the effect of the knocking-down SMRT expression on the transcription of endogenous VDR-target genes, OC and CYP24 (22, 54), in HEK293 cells by RT-PCR. The endogenous OC gene of HEK293 cells was significantly expressed even in the absence of the D3 ligand, and its expression was increased about 2-fold by D3 treatment (Fig. 1C). In contrast, CYP24 expression was totally dependent on the presence of the D3 ligand. The knocking-down of SMRT resulted in the derepression of OC and CYP24 transcription even in the absence of ligand (Fig. 1C), indicating that SMRT actively represses the basal transcription of the endogenous OC and CYP24 genes in HEK293 cells. The mRNA levels of VDR and GAPDH were not altered by these treatments.

To address D3- and VDR-dependent recruitment of endogenous SMRT to the VDR-target gene, we employed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays using the endogenous OC promoter as a target (Fig. 1D). VDR and SMRT antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate the protein-DNA complex in the absence or presence of the D3 ligand in HEK293 cells. To verify VDRE-dependent factor occupancy, we designed two primer sets to detect the putative VDRE region (region I) and the promoter proximal region lacking the VDRE (region II). As shown in Fig. 1D, VDR was associated with the VDRE region in the absence of the D3 ligand and its association was significantly increased by D3 as expected. Notably, SMRT also associated with the VDRE region in the absence of ligand but in contrast to the VDR, its association was completely abolished by D3 treatment. The binding of VDR and SMRT was restricted to the VDRE of the OC gene, because no signals were detected in region II of OC and exon 4 of the β-action gene (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these results suggest that SMRT is required for transcriptional repression by unliganded VDR in vivo and that the VDR-SMRT complex is actually associated with the VDRE regions of target gene.

The VDR displays ID1 and SMRT preferences for corepressor interaction

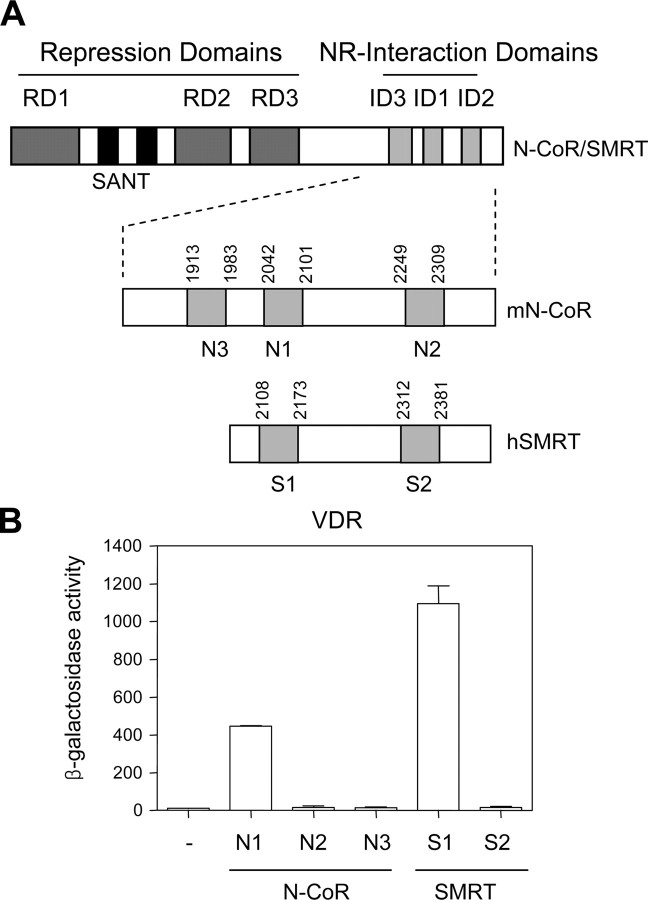

The above results strongly suggest that the SMRT corepressor is directly involved in VDR-mediated repression of target genes. However, we do not know whether the VDR-specific interaction with SMRT is essential for this repression because RXR (the heterodimeric partner of VDR) also participates in this repression. Therefore, we focused on how N-CoR/SMRT mediates the repression of VDR-target genes by examining the molecular determinants of the interactions between unliganded VDR and these corepressors. As a first step, we investigated the interaction profile of corepressor IDs and the VDR using the yeast two-hybrid assay. The bait protein VDR was expressed as a LexA-fusion. The five protein fragments with the centrally located extended-helix motif of ID1 (N1, S1) or ID2 (N2, S2) of N-CoR/SMRT or ID3 (N3) of N-CoR were expressed as triple fusions between B42 and Gal4-DNA binding domain (GBD) (Fig. 2A). Human forms of VDR and SMRT, and mouse version of N-CoR were used for these constructs. The expression vector for B42-GBD was devised for the operation of one- plus two-hybrid system but also can be used for the conventional two-hybrid interaction test (51). As shown in Fig. 2B, the VDR interacted exclusively with ID1 of the corepressors (N1 and S1), but not with ID2 (N2 and S2) or ID3 (N3). In particular, the interaction of the VDR with S1 was more than 2.5-fold stronger than its interaction with N1, explaining the previous observation that the interaction of VDR with SMRT was stronger than that with N-CoR in the mammalian two-hybrid interaction assay (53). Thus, the ID1 of N-CoR/SMRT is the major interaction partner for the VDR (ID1 preference), and the VDR prefers SMRT-ID1 to N-CoR-ID1 (SMRT preference) in the yeast two-hybrid system.

Fig. 2.

VDR shows ID1 and SMRT preferences for corepressor interaction in the yeast two-hybrid assay. A, Schematic depiction of the modular structure of N-CoR/SMRT and the locations of ID constructs used in this study. N-terminal autonomous repression domains (RDs) and C-terminal NR-IDs are shown in dark and light gray, respectively. The conserved SANT [switching-defective protein 3, adaptor 2, nuclear receptor corepressor, and transcription factor IIIB (or Swi3, Ada2, N-CoR, TFIIIB)] motifs (black) essential for histone deacetylase activity are shown. The N1 (ID1; amino acids 2042–2101), N2 (ID2; amino acids 2249–2309), and N3 (ID3; amino acids 1913–1983) fragments of mouse N-CoR (mN-CoR) and the equivalent regions of human SMRT (hSMRT), S1 (amino acids 2108–2173) and S2 (amino acids 2312–2381), were inserted between the B42 activation domain and GBD and used as prey constructs in the yeast two-hybrid assay. All ID constructs encoded the 60-amino acid fragment with the centrally located conserved extended-helix motif of nine amino acids. B, Yeast two-hybrid interaction assays. The yeast strain EGY48, harboring the pSH18-34 plasmid (lexAop-LacZ reporter), was cotransformed with the bait plasmid expressing the LexA-VDR and the indicated prey vectors expressing corepressor-ID (N1, N2, N3, S1, or S2) fusions between B42 and GBD or B42-GBD vector alone (−). Liquid β-galactosidase assays were carried out with three or more transformants and the mean ± se values are shown on the y-axis. Similar results were obtained in multiple repeated experiments.

ID1 is required for VDR-corepressor interaction

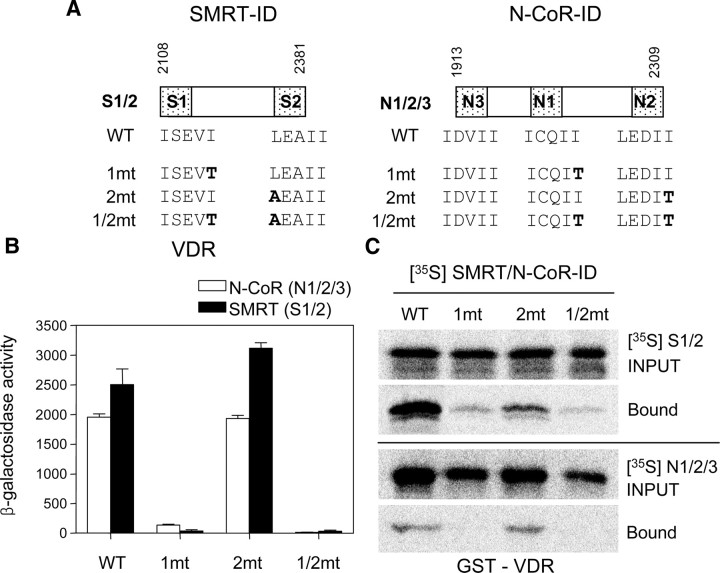

To verify the role of the corepressor ID1 in VDR-mediated repression, we examined the contribution of individual IDs to the interactions with the VDR in the yeast two-hybrid assays. For this purpose, we first constructed B42-GBD fusions of the S1/2 fragment, containing both IDs of SMRT, and its mutant derivatives having single (1mt, 2mt) or double amino acid changes (1/2mt) in the CoRNR motifs of ID1 (I+9T for S1 where the first Leu of the extended helix motif is denoted as +1) and ID2 (L+1A for S2) (Fig. 3A, left). Similarly, we also constructed the N1/2/3 fragment containing all three IDs of N-CoR and its mutant derivatives with single (1mt, 2mt) or double amino acid changes (1/2mt) in the CoRNR motifs of ID1 (I+9T for N1) and ID2 (I+5T for N2) (Fig. 3A, right). All these mutations are known to completely disrupt the interaction of each corepressor-ID with the target NR (45).

Fig. 3.

Corepressor-ID1 is required for VDR interaction. A, Schematic representations of the SMRT and N-CoR constructs used in this study. Substitution mutations were introduced into the indicated residues within the CoRNR motifs of ID1 and/or ID2 of corepressor fragments S1/2 and N1/2/3. The sequence of the CoRNR motifs corresponding to each ID are shown below the wild-type (WT) constructs, and the numbers at the top indicate the positions of amino acids of each ID used in this study. The mutant constructs having single or double ID mutations are represented as 1mt (ID1 mutant), 2mt (ID2 mutant), or 1/2mt (ID1/2 double mutant), and the changed residues in each ID are indicated in bold. B, Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed with EGY48 strains coexpressing LexA-VDR and B42-GBD fusions of the indicated ID constructs of N-CoR (white bar) or SMRT (black bar), and liquid β-galactosidase activities were measured. The results are the means ± se values obtained from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate. C, GST pull-down assays for the interactions of VDR with the indicated ID constructs of SMRT or N-CoR. The 35S-labeled in vitro-translated S1/2 or N1/2/3 derivatives were incubated with GST-VDR, and the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as described in Materials and Methods. INPUT represents 10% of the in vitro-translated proteins used in the pull-down assay.

Consistent with the ID1 preference for the VDR-corepressor interaction (Fig. 2B), the strong binding of VDR to S1/2 or N1/2/3 fragment was completely abolished by the ID1 (1mt) or ID1/2 (1/2mt) mutations. In contrast, the ID2 mutations (2mt) had no effect on VDR binding, indicating the requirement for ID1 in the VDR interaction in yeast. VDR consistently showed somewhat stronger interaction with S1/2 than with N1/2/3 (Fig. 3B). Next, the S1/2 and N1/2/3 derivatives were used in glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays to confirm the yeast data in an in vitro system (Fig. 3C). As expected, the binding between in vitro-translated wild-type S1/2 and the GST-fused VDR was nearly abolished by the ID1 and ID1/2 mutations. However, VDR binding to S1/2 was also significantly reduced by the ID2 mutation, which is inconsistent with our failure to observe an interaction between S2 and VDR in yeast (Fig. 2B) and in vitro (data not shown). We currently do not know the reason for this discrepancy, but we have some evidence that SMRT-ID2 is indirectly involved in the VDR interaction in mammalian cells (see below). Similar to the binding pattern to S1/2, VDR interacted with wild-type and 2mt derivatives of N1/2/3 but not with its 1mt and 1/2mt mutants, confirming the importance of N1 in the VDR interaction in vitro. We also found that VDR interacted more strongly with the S1/2 than with N1/2/3, although this SMRT preference could not be seen in the yeast two-hybrid interaction assay (compare Fig. 3, B and C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that VDR-ID1 interaction has a major and essential role in the VDR-corepressor interaction.

ID1 requirement for corepressor-VDR interaction in a mammalian system

To further define the corepressor ID1-VDR interaction in a more biologically relevant system, a mammalian two-hybrid assay was performed. The VDR was fused to a GBD (Gal4-VDR), whereas ID1 and ID2 of the corepressors were fused to a p65 activation domain (AD-N1, -N2, -S1, and -S2). HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with these plasmids along with the luciferase reporter gene driven by the upstream Gal4-binding site (Gal4-TK-LUC). As shown in Fig. 4A, the VDR interacted exclusively with N1 and not with N2. However, in contrast to yeast data, the VDR did not interact with the individual IDs of SMRT, and only the S1/2 fragment showed significant binding to the VDR (Fig. 4B). In particular, the VDR-S1/2 interaction was specifically abolished by the ID1 or ID1/2 mutation, but not by the ID2 mutation, which is consistent with the yeast and in vitro data. These results suggested that SMRT-ID1 is the major target for VDR binding and that the CoRNR motif in ID2 is not directly involved in the VDR interaction, although S1 alone cannot bind with VDR under this experimental condition (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

ID1 requirement for corepressor-VDR interaction in a mammalian system. Mammalian two-hybrid assays were performed to investigate VDR interaction with IDs of N-CoR (A) or SMRT (B). HEK293 cells were transfected with the Gal4-TK-luciferase reporter alone or together with the pCMX-Gal4-VDR plasmid (200 ng/well), and with the pCMV-AD vector (200 ng/well) alone or in combination with the pCMV-AD vector expressing the p65 activation domain fused to the indicated corepressor IDs [N1, N2, S1, and S2 (white bar); S1/2 wild-type (WT) and mutant derivatives (black bar)]. Luciferase activities were measured as described in Materials and Methods and represented as the fold activation over the value obtained with the pCMX-Gal4-VDR plus pCMV-AD only. C, ID1 requirement for the dominant-negative effect of the S1/2 fragment on VDR-mediated transcriptional repression. HEK293 cells were transfected with the Gal4-TK-luciferase reporter alone or in combination with the pCMX-Gal4-VDR plasmid (200 ng/well) (white bar) and the pcDNA3HA vectors (200 ng/well) expressing the S1/2 wild-type (WT) or the indicated mutants (black bar). Luciferase activities were represented as the fold repression over the value obtained with the reporter alone. The results are the means ± se values obtained from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate. D, Expression levels of the S1/2 derivatives were examined by immunoblot analysis using monoclonal anti-HA antibody with whole-cell extracts prepared from nontransfected (−) and transfected cells. Nonspecific signals generated by the anti-HA antibody served as the loading control. AD, Activation domain.

Because the predominant role of the corepressor is associated with the repressive function of unliganded NRs, we next examined the effects of overexpression of S1/2 and its mutant fragments on VDR-mediated repression of a reporter gene (Fig. 4C). We expected that the expressed S1/2 fragments can reverse the repressive activity of VDR if they are able to interact with the VDR (dominant-negative effect). The Gal4-VDR showed a 2-fold repression of reporter-gene expression, and this repressive effect was reversed by the overexpression of the wild-type S1/2, indicating that the S1/2 fragment specifically competed with endogenous corepressors to play a dominant-negative role in VDR-mediated repression. Interestingly, S1/2 fragments containing the ID1 or ID1/2 mutation, but not the ID2 mutation, had no effect on VDR-mediated repression, indicating that these mutants were unable to interact with the VDR. Western blot analysis revealed that the differences in reporter-gene activities were not due to differences in the expression levels of the S1/2 mutants (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these results consistently support the conclusion that the VDR interacts with SMRT-ID1 as a major and essential partner in a mammalian system.

Screening of SMRT-ID1 mutants defective in VDR interaction

To gain further insight into the mode of corepressor-VDR interaction at the molecular level, we focused on the interaction of SMRT-ID1 with the VDR, because the VDR showed preferential interaction with the SMRT. We used the one- plus two-hybrid screening system to identify the amino acid residues within S1 that mediate high-affinity binding to the VDR. As mentioned previously, this system was recently developed to efficiently select for missense mutations that specifically disrupt a known protein-protein interaction (51).

The VDR was expressed as a LexA-fused bait protein (pRS325LexA-VDR), and the SMRT-ID1 (S1) region was expressed as a triple-fusion prey protein (B42-S1-GBD) as described above. We adopted a PCR-mediated random mutagenesis and gap-repair recombination method to generate the mutant cell library for the S1 region (55, 56). The randomly mutagenized S1 DNA fragments were generated using specific primers in the presence of 0.1 mm MnCl2 and were cotransformed with the linearized gap plasmid into strain YOK400 harboring the LexA-VDR plasmid and the episomal two-hybrid reporter (lexAop-LacZ) plasmid. The transformants were grown in synthetic glucose medium containing 10 mm 3-amino-1,2,4-trialzol but lacking histidine for the positive selection of intact prey fusions using the endogenous UASGAL-HIS3 reporter gene. Among the surviving transformants, noninteracting mutants were selected by isolating white colonies on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) plates.

We isolated white yeast colonies on X-gal plates from among the 1445 transformants that survived the first positive screening for missense mutations. The prey plasmids were rescued and individually retransformed into EGY48 expressing LexA-VDR and EGY-LG containing UASGAL-LacZ reporter to confirm two-hybrid and one-hybrid (intactness of prey fusion) interactions, respectively. A total of 32 candidates showing white color in the two-hybrid assay and blue color in strain EGY-LG were subjected to DNA sequencing. Almost all of the mutants had single-point missense mutations. Although some mutants harbored double mutations, there were no nonsense or frame-shift mutations.

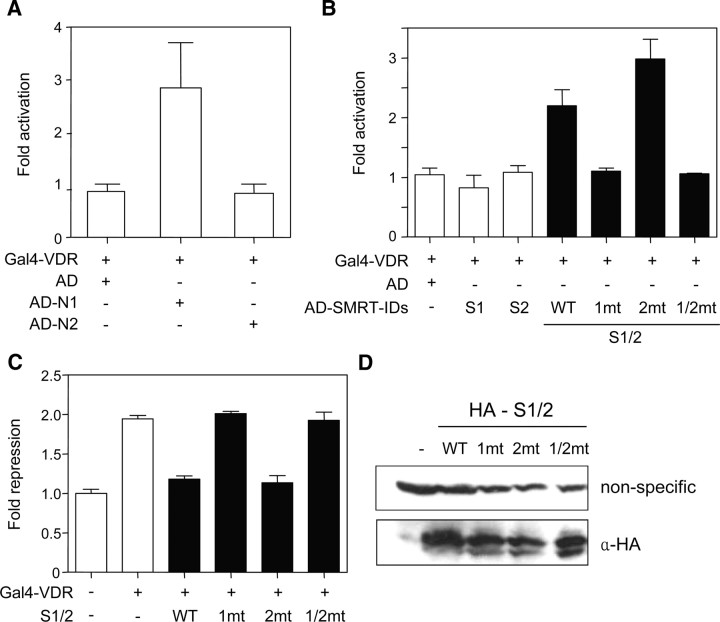

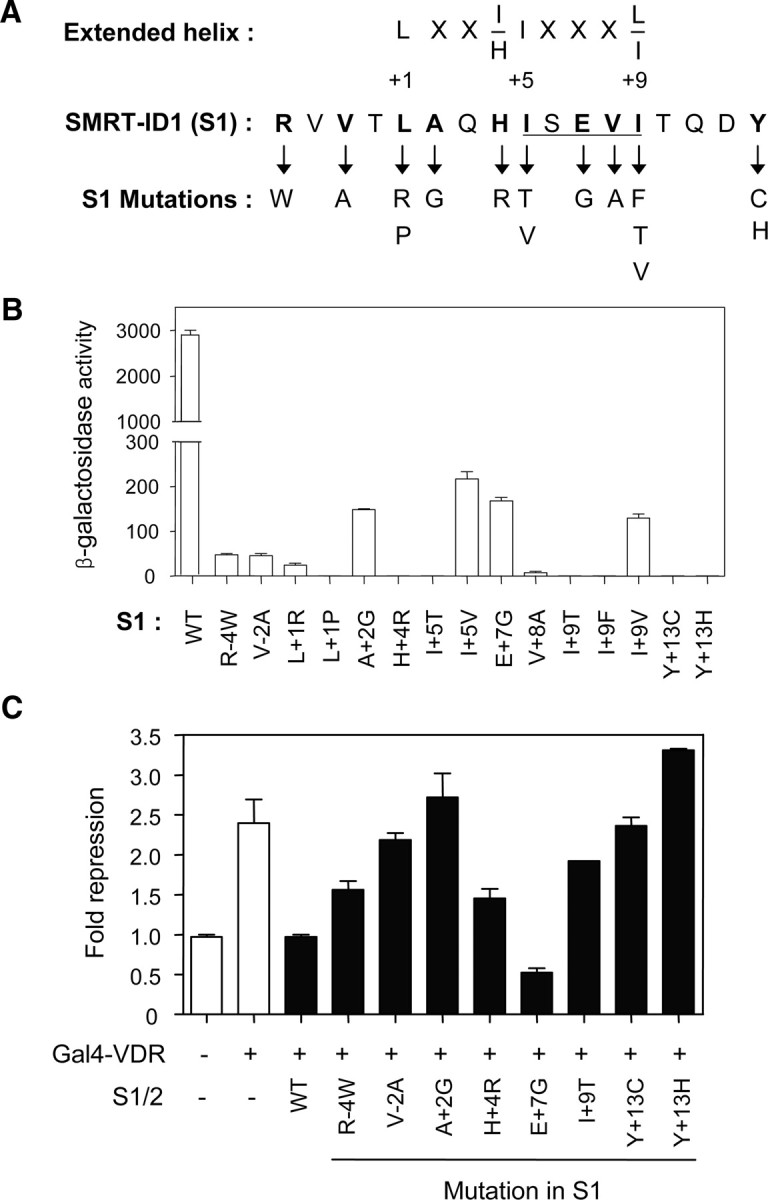

Figure 5A shows the mutational sites and the changed amino acids in the isolated S1 mutants defective in VDR interaction. Consistent with our previous observations and those of other workers, almost all of the identified amino acid residues were located within the extended helix motif (L+1, A+2, H+4, I+5, E+7, V+8, and I+9). Among these residues, L+1, I+5, and I+9 were previously shown to be general requirements for NR interaction (45, 46) and V+8 was also considered to be a general determinant from our study on N-CoR-ID1 (51). Interestingly, mutations at residues R − 4, V − 2, and Y+13, which are located outside the extended-helix motif, were also isolated. Although some mutants (A+2G, I+5V, E+7G, and I+9V) had relatively weak binding activity, the interaction of these mutants with the VDR was significantly weaker than with the wild-type SMRT-ID1 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

SMRT-ID1 mutants defective in VDR interaction. A, The identified S1 mutations are shown below the corresponding residues of SMRT-ID1, in which the CoRNR1 motif is underlined. The bold letters indicate the residues identified in the mutant screening. The consensus sequence of the extended helix (LXXI/HIXXXL/I) is represented at the top, where the Leu is denoted as +1. B, Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed to determine the interactions between LexA-VDR and B42-GBD fusions of the wild-type (WT) and indicated S1 mutants in the EGY48 strain. C, Dominant-negative effects of S1 mutations on VDR-mediated transcriptional repression. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the Gal4-TK-luciferase reporter alone or in combination with the pCMX-Gal4-VDR plasmid (200 ng/well) (white bar) and pcDNA3HA vectors (200 ng/well) expressing the S1/2 wild type or mutant derivatives harboring the indicated S1 mutation (black bar). Luciferase activities were represented as the fold repression over the value obtained with the reporter alone. The results are the means ± se values obtained from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate (B and C).

To examine the mutational effects of the S1 mutants in the relevant biological system, we investigated whether the isolated S1 mutants have the ability to relieve the VDR-mediated repression of a reporter gene expression. Because the wild-type S1/2 fragment plays a dominant-negative role in VDR-mediated repression (Fig. 4C), we introduced the same S1 mutations into the S1/2 fragment and used them for dominant-negative assays. As shown in Fig. 5C, the S1/2 fragments containing single mutations at residue V − 2, A+2, I+9, or Y+13 of S1 had no effect on VDR-mediated repression, indicating that these mutants were unable to interact with VDR. In a good agreement of yeast data, other I+9 substitution mutants (to F, V) also had no effect on VDR-mediated repression (data not shown). In contrast to the yeast two-hybrid data, however, overexpression of R − 4W, H+4R, or E+7G mutants resulted in derepression of the reporter gene activity, implying that these mutants partially (R − 4, H+4) or completely (E+7) compete with endogenous corepressors by directly interacting with VDR. Taken together, these results indicate that a wide range of amino acid residues, within or outside of the extended-helix motif of SMRT-ID1, are involved in VDR interaction.

The effect of the ID1 mutation in full-length SMRT on VDR-mediated repression

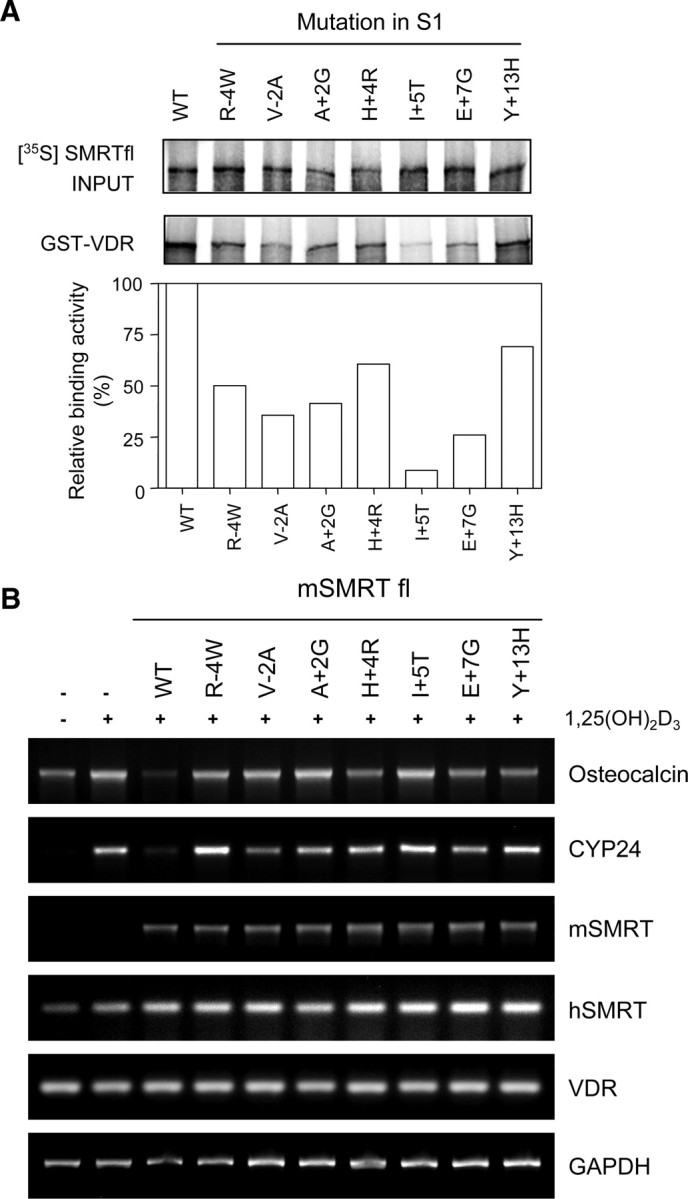

To confirm the S1 mutational effects (Fig. 5) in the context of full-length SMRT, we introduced the same S1 mutations into full-length mouse SMRT and tested their effects on VDR-mediated repression. All of the residues encompassing the extended helix motif of IDs are highly conserved between human and mouse SMRTs. Firstly, we performed GST pull-down assays to confirm the effect of ID1 mutations on the interaction between VDR and full-length SMRT in vitro. As shown in Fig. 6A, wild-type SMRT showed significant binding to GST-VDR whereas all of the tested ID1 mutants (R − 4W, V-2A, A+2G, H+4R, I+5T, E+7G, and Y+13H) had defects in VDR binding, although the extent of binding efficiency varied depending on the mutant (5–65%). These results confirm that the S1 residues within or outside of the extended-helix motif are also involved in the VDR interaction with full-length SMRT. Next, we examined the ability of S1 mutants to augment VDR-mediated repression of the OG2-LUC reporter gene in HEK293 cells. Unfortunately, ectopic expression of SMRT enhanced the reporter gene repression only 1.5-fold as compared with the expression by VDR alone, indicating that this repressive effect is too small to evaluate the mutational effects of SMRT-ID1 mutants (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Requirement of the SMRT-ID1 motif for the repression of endogenous VDR-target genes. A, GST pull-down assays for the detection of interactions of VDR with the indicated SMRT-ID1 mutants. The 35S-labeled and in vitro-translated full-length versions of SMRT wild-type (WT) or its ID1 mutant derivatives were incubated with GST-VDR, and the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. INPUT represents 10% of the in vitro-translated proteins used in the pull-down assay. The relative binding activities are represented by the graph in which the binding strength of the SMRT wild-type to VDR is set to 100%. B, Repressive effect of the SMRT wild-type (WT) or ID1 mutants on the transcription of VDR-target gene in the presence of the D3 ligand. HEK293 cells were transfected with pCMXflag-mSMRT fl wild-type (WT) or its ID1 mutants in the absence or presence of 10−6 m D3. The mRNA expression levels of OC, CYP24, mSMRT, hSMRT, VDR, and GAPDH genes were analyzed by RT-PCR. hSMRT and mSMRT represent human and mouse forms of SMRT, respectively.

Therefore, to demonstrate the physiological relevance of the VDR-SMRT interaction, we examined the effects of the S1 mutations on the transcription of endogenous VDR-target genes, OC and CYP24. We first examined whether SMRT overexpression could repress OC and CYP24 gene transcription activated by the D3 ligand in HEK293 cells. As shown in Fig. 6B, OC gene expression induced by the D3 ligand was reduced to below the level of basal transcription by wild-type SMRT overexpression. Also, ectopic expression of SMRT repressed D3-dependent induction of CYP24 transcription to near the basal level. All these effects occurred without any apparent changes in endogenous hSMRT and VDR transcription (Fig. 6B). In contrast, overexpression of any of the SMRT ID1 mutants (R − 4W, V − 2A, A+2G, H+4R, I+5T, E+7G, or Y+13H) had nearly no effect on D3-stimulated transcription of the endogenous OC and CYP24 genes, indicating that these residues surrounding the SMRT-ID1 are required for VDR-mediated target gene repression. In conclusion, SMRT ID1 mutants defective for the VDR interaction are also defective in the repression of VDR-target genes in vivo, indicating that the SMRT corepressor is actually involved in VDR-mediated repression via an ID1-specific interaction with the VDR.

The general and specific determinants of SMRT-ID1 for NR interaction

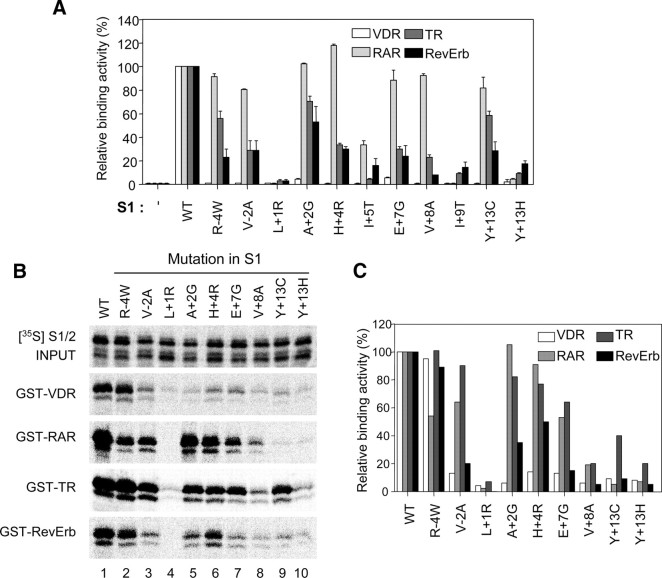

Our previous observations suggested that there are general and specific determinants within N-CoR-IDs for NR interaction (51). Therefore, we investigated the binding activities of the S1 mutants with various target NRs using the yeast two-hybrid assay. To compare the mutational effects of the S1 mutations on target NR binding, the NR binding activities of the isolated S1 mutants were expressed as a ratio of S1 wild-type binding activity (Fig. 7A). As expected, the interactions of S1 mutants with the RAR, RevErb, and TR were abolished by the L+1, I+5, and I+9 mutations, reconfirming that these residues act as general determinants of SMRT-ID1 for NR interaction. Although the V+8A mutation had a negligible effect on RAR binding, we consider the V+8 residue to be a general, rather than a specific, determinant, because no NRs could interact with the V+8A mutant in vitro (see below; Fig. 7B). In contrast, mutations at residues R-4, V-2, A+2, H+4, E+7, and Y+13 displayed obvious differential effects on NR binding. Although the R − 4, V − 2, H+4, and E+7 residues were identified as absolute requirements for VDR interaction in yeast, they had negligible effects on RAR binding and partial defects in RevErb and TR binding. In addition, the A+2G mutation had no effect on any NR binding except for the VDR. Interestingly, the Y+13H mutation abolished all NR binding to S1, whereas the Y+13C mutation had partial defects in RAR and TR binding.

Fig. 7.

General and specific determinants of SMRT-ID1 (S1) for NR binding. A, The relative binding activity of each S1 mutant for the tested NRs in yeast. Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed with EGY48 strains coexpressing LexA-fused RAR, TR, RevErb, or VDR and the B42-GBD fusions of the wild-type (WT) or indicated S1 mutants. Yeast two-hybrid interaction of LexA-NRs with the B42-GBD alone was also shown as control (−). The binding strength of the wild-type S1 to each NR was set to 100%. B, GST pull-down assays for the interactions between identified S1 mutants and target NRs. The S1/2 wild-type (WT) or mutant derivatives having the indicated ID1 mutations were labeled with 35S and incubated with GST-fused VDR, RAR, TR, and RevErb. The bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. INPUT indicates 10% of the in vitro-translated S1/2 proteins used in the pull-down assays. C, The amounts of bound proteins were quantified using the Personal Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). The relative binding activities are represented by the graph in which the binding strength of the wild-type S1/2 to NRs is set to 100%.

To confirm the effects of the SMRT-ID1 mutations on NR binding in vitro, we carried out GST pull-down analysis to investigate the interactions between in vitro synthesized SMRT-ID1 derivatives and GST-fused NRs. We could detect significant binding of the S1/2 fragment, but not of the S1 fragment, with GST-VDR (data not shown), indicating that both ID1 and ID2 are required for optimal VDR binding in vitro. This result is in good agreement with our previous observations that VDR interacts with S1/2, but not with S1, in the mammalian two-hybrid assay (Fig. 4B). Accordingly, we used the S1/2 fragments containing the identified S1 mutations for GST pull-down analysis.

None of the S1/2 derivatives carrying ID1 mutations had detectable VDR binding except for the R-4W mutant. Among the residues regarded as general determinants, L+1, I+5, V+8, and I+9 acted as general requirements for in vitro interactions with all of the tested NRs, as predicted (Fig. 7B and data not shown). In contrast, R − 4W mutant showed no significant defects in all NR binding, and the mutations at residues V − 2, A+2, H+4, and E+7 showed different in vitro binding patterns depending on the NR (Fig. 7B). For example, mutations at all of these residues had negligible effects on RAR and TR binding, but the V − 2A, A+2G, and E+7G mutants had significant defects in RevErb binding. In addition, mutations at the Y+13 residue showed general defects on in vitro interactions with NRs except that Y+13C had a marginal effect on TR binding. Although some variability was observed (e.g. RAR), the overall binding patterns in the yeast two-hybrid and GST pull-down analyses were similar (compare Fig. 7, A and C). Collectively, the above results suggest that residues L+1, I+5, V+8, I+9, and possibly Y+13 of SMRT-ID1 are required for all NR binding (general determinants), whereas residues V-2, A+2, H+4, and E+7 are differentially required for NR binding depending on the specific NR (specific determinants).

Discussion

In this study, we provide some important insights into the physiological relevance and the molecular mechanism of VDR-mediated repression by SMRT. First, we revealed the involvement of the SMRT corepressor in the transcriptional repression of the VDR-target genes, OC and CYP24, in vivo. Second, to address the requirement of VDR-SMRT interaction in this repression, we investigated molecular determinants for the specific interaction between SMRT-IDs and the unliganded VDR using the one- plus two-hybrid system. Using SMRT-ID1 mutants specifically defective in VDR interactions, we could demonstrate that SMRT corepressor is actively involved in the VDR-mediated repression via an ID1-specific interaction with VDR. Finally, we have identified the specific residues within SMRT-ID1 that are generally required for optimal NR binding (general determinants) as well as those involved in preferential interaction with specific NRs (specific determinants).

SMRT as a corepressor for the repression of VDR-target genes in vivo

Although the VDR has been shown to interact with various corepressors, such as N-CoR/SMRT and Alien, the biological relevance of these interactions has been unclear up until now (30, 31, 35). Recently, Hairless was reported to function as a corepressor of certain NRs, including VDR, TR, and the RAR-related orphan receptors, via functional and physical interactions (32, 34, 57). All these observations have made it difficult to draw a conclusion about the physiological role of SMRT and its mechanism of action in VDR-mediated repression in vivo. In this regard, we first tried to address whether the SMRT corepressor is actually involved in transcriptional repression by the unliganded VDR. We showed that the knocking down of SMRT expression resulted in the derepression of endogenous VDR- target genes, OC and CYP24 as well as an OG2 (VDRE)-reporter gene in HEK293 cells (Fig. 1). In addition, we provided evidence that unliganded VDR recruits SMRT to the VDRE region of the OC promoter, and that the binding of SMRT to the VDRE is totally abolished by the presence of the D3 ligand. We also tested the binding of exogenous VDR and SMRT to the VDRE region of the OG2 reporter gene in the presence and absence of D3 ligand. We obtained similar results using the endogenous OC gene and proteins (data not shown), confirming the association between SMRT and the unliganded VDR in the VDRE region of target genes. Overall, the results strongly suggest that the SMRT corepressor plays a physiological role in VDR-mediated repression in vivo.

VDR-mediated repression of the OC gene in HEK293 cells

In general, nonsteroid NRs including VDR are known to bind to their cognate element as heterodimers with RXR and to recruit corepressor proteins for the repression of transcription of target genes in the absence of a cognate ligand (28, 29). In contrast to this widely held view, Carvallo et al. (17) reported that the VDR binds to the OC promoter only after D3 treatment, which would tend to suggest that VDR-mediated repression by SMRT is unlikely to be involved in OC repression in the absence of the D3 ligand. However, our analysis clearly showed that the unliganded VDR is actually present in the VDRE region of the endogenous and reporter OC promoters in HEK293 cells. This discrepancy could be explained in two ways. First, regulation of OC transcription could be cell type specific. Carvallo et al. examined VDR binding to the OC promoter in osteoblast cells whereas we used HEK293 kidney cells. Second, differences in the experimental conditions for the ChIP assays could be responsible.

We observed a basal level of OC expression in HEK293 cells even in the absence of D3 ligand (Fig. 1C). Consistent with this, it was reported that OC mRNA is also expressed at a low basal level in several nonosseous tissues, including kidney, liver, and lung (58, 59). In addition, a mouse-specific member of the OC gene family, the osteocalcin-related gene (ORG), is expressed in the kidney where it could serve as an important crystallization inhibitor (60). Accordingly, we suggest that this high level of basal expression might be why we observed only a 2-fold stimulation of OC transcription by the D3 ligand and a relatively weak effect of siSMRT on the derepression of OC and OG2 reporter genes in this cell type (Fig. 1, B and C).

Molecular determinants of the interaction between SMRT and VDR

As mentioned in the introduction, NRs have the ability to distinguish the corepressor-IDs for their specific interaction, which determines the corepressor preference (N-CoR vs. SMRT) or the ID preference (ID1 vs. ID2) of a given NR (47). However, the molecular mechanism of this selective and specific binding of corepressor-IDs to VDR is not fully understood. As a first step to reveal this, we demonstrated that the VDR interacts exclusively with ID1 of N-CoR/SMRT, which is required for the optimal interaction between the corepressor and the VDR (Figs. 2–4). Second, using a one- plus two-hybrid system, we have identified the residues R − 4, V-2, L+1, A+2, H+4, I+5, E+7, V+8, I+9, and Y+13, located within or outside of the extended helix motif of SMRT-ID1 (+1LAQHISEVI+9), as important for VDR interaction (Fig. 5). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of these residues would not be a direct target for VDR interaction because mutations at those residues might cause the indirect change of the secondary structure of the extended helix.

As recognized from the last three figures, mutations of the R-4 and E+7 residues had different effects depending on the method employed. The S1 mutant R − 4W showed defective functional and physical interactions with the VDR in the yeast two-hybrid and in the mammalian dominant-negative mutant analyses (Fig. 5). However, R − 4W had reduced or negligible effects in in vitro pull-down analyses (Figs. 6A and 7B). Similarly, a mutation at residue E+7 had no defect in the mammalian dominant-negative analysis (Fig. 5C). To clarify the reasons for these discrepancies, we introduced these mutations into full-length SMRT and investigated their effects on endogenous OC and CYP24 transcription activated by the D3 ligand. Interestingly, none of the SMRT mutants, including R − 4W, and E+7G, could repress D3-stimulated transcription of OC and CYP24 genes, indicating that these S1 residues, which are critical for the interaction of SMRT with the VDR, are important for mediating the repression of VDR-target genes in vivo (Fig. 6B). There are also some discrepancies between in vitro binding profiles of full-length S1 mutants and their S1/2 fragment versions (Figs. 6A and 7B). For example, full-length Y+13H mutant showed a significant in vitro binding activity to VDR as compared with other mutants, whereas R − 4W in S1/2 context had no defects in VDR binding. We currently do not recognize the reason for these context-dependent differences in VDR binding pattern.

We also examined the requirement for the S1 motif in SMRT recruitment to the OG2 promoter by performing ectopic expression of wild-type SMRT or its ID1 mutant (I+5T) and ChIP analysis. As expected, wild-type SMRT was recruited in the absence of ligand, and this recruitment was reversed by D3 treatment. In contrast, the SMRT ID1 mutant which was defective for the VDR interaction could not be detected on the VDRE of the OG2 gene under the same conditions (data not shown), confirming that SMRT recruitment to the VDRE region is mediated by a direct interaction between VDR and SMRT-ID1.

Molecular determinants of SMRT-ID1 for NR interactions

From the analyses of the isolated S1 mutants, we have classified the L+1, I+5, V+8, and I+9 residues as the general determinants of S1 for NR binding, as revealed by our in vivo and in vitro analyses (Fig. 7). In a good agreement with our findings, these residues are conserved within either the extended helix motif (L+1, I+5, and I+9) or the CoRNR motif (I+5, V+8, and I+9) of SMRT-ID1, as well as in N-CoR-ID1, reinforcing the general importance of these residues for NR binding of both SMRT and N-CoR (51). With respect to the effects of mutations at residues Y+13 of S1, the results of the in vitro and mammalian interaction assays consistently showed that residue Y+13 is a general determinant for NR binding, despite the fact that the Y+13C mutant showed preferential interaction to a specific NR in yeast (Fig. 7). On the contrary, residues V-2, A+2, H+4, and E+7 of SMRT-ID1 are obviously classified as specific requirements for binding to a particular NR. Among these, informative mutations at the V-2, A+2, H+4, and E+7 residues were not identified in the screening for N-CoR-ID1 mutants defective in RAR interaction (51). We hypothesized that this might be due to the difference in the target NR used for screening. To address this possibility, we introduced an H+4A mutation into N-CoR-ID1 and examined its effect on NR binding. This mutant showed a significant defect in VDR binding, but had a negligible effect on RAR binding in the yeast two-hybrid assay, confirming our hypothesis (data not shown).

We hope our diverse corepressor mutants showing general or differential effects on NR interactions will be very useful for the functional dissection of NR-specific repression mechanisms, as well as for the structural modeling of NR-corepressor interaction.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and siRNA

The constructs expressing IDs of N-CoR and SMRT were generated by cloning the PCR fragment corresponding to each ID into the appropriate restriction sites of pRS424UB42-GBD (51), pcDNA3HA (61), and pCMV-AD (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) vectors. The N3 and N1/2/3 DNA fragments correspond to the coding region of ID3 (amino acids 1913–1983) and ID1/2/3 (amino acids 1913–2309), respectively, of the mouse N-CoR. Similarly, the S1/2 fragment corresponds to the coding region of ID1/2 (amino acids 2108–2381) of the human SMRT. The N1, N2, S1, and S2 DNA fragments subcloned in pEG202 vectors, pGEX4T-1-NR constructs (human forms of the RARα, TRα, and RevErb), were described previously (51). Mutant derivatives of N1/2/3 and S1/2 were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis and cloned into appropriate vectors as described previously (51). The pCMX-hVDRfl (full-length) DNA was the kind gift of Makoto Makishima (Nihon University, Tokyo, Japan). The partial human VDR (amino acids 4–428) was subcloned into EcoRI/XhoI sites of pcDNA3 and pcDNA3HA, EcoRI/NotI sites of pEG202, SalI/NotI sites of pGEX4T-1, and EcoRI/SalI sites of pCMX-Gal4N (62). hVDR were also subcloned into the appropriate sites of the pRS325LexA vector for mutant screening (51). The DNA fragment containing the three repeats of the VDRE (3×VDRE) was generated from the OC gene promoter (63) by PCR using the appropriate primers and inserted into the XhoI site of the pLGZ vector, resulting in the pLGZ-3×VDRE reporter plasmid. The mouse OG2-luciferase reporter plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Jeong-Tae Koh. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. The siRNA against the human form of SMRT (2584AAGGGUAUCAUCACCGCUGUG2604) (64) and the siGENOME Non-Targeting siRNA no. 1 (D-001210-01-05) were chemically synthesized (Dharmacon Research, Lafayette, CO), deprotected, annealed, and transfected according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mouse SMRTα full-length gene cloned in pCMX-flag vector (pCMXflag-mSMRT) was supplied by Dr. Ronald M. Evans.

siRNA treatment, transient transfections, and immunoblot assays

HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum or 10% charcoal-stripped serum for ligand treatment. For siRNA treatment, cells at 30–50% confluency were transfected with the indicated amounts of siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For transient transfection of DNA, HEK293 cells were transfected with the appropriate set of reporter and expression plasmids using SuperFect reagent (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA) and assayed for luciferase activity according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plasmid DNAs used for transfection included the OG2-LUC reporter, the pCMX-hVDRfl, and/or the pCMXflag-mSMRT construct for functional assays or ChIP analyses. For the mammalian two-hybrid assay, Gal4-TK-LUC luciferase reporter, the pSV-β-gal control plasmid, pCMX-Gal4N-VDR, and pCMV-AD-N1, -N2, -S1, -S2, or -S1/2 wild-type or mutants were used. Similarly, the pcDNA3HA-S1/2 wild-type or mutants were used for the dominant-negative assay, as indicated in the figure legends. To detect the expression levels of hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged S1/2 and its mutants, whole-cell extracts from transiently-transfected HEK293 cells were prepared and immunoblot analysis using monoclonal antibody against HA (12CA5) was performed as previously described (51).

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from transfected cells by the Trizol method (Invitrogen), subjected to reverse transcription using Reverse Transcriptase Premix kit (Elpis-Biotech, Seoul, Korea), followed by semiquantitative PCR. The sequences of the primers were as follows: human SMRT, 5′-CGCAACTGGTCGGCCA-3′ [forward (F)] and 5′-GCTGCAAGATCTCATCGAGGT-3′ [reverse (R)]; mouse SMRT, 5′-CTGCCCGAGAGCCAGCCCTC-3′ (F) and 5′-GGACAGGGCAGCTGGCTCC-3′ (R); N-CoR, 5′-AGCATTCCATCCCTACGGG-3′ (F) and 5′-TGGACCCCTTCACCAAAGC-3′ (R); HDAC3, 5′-ACGTGGGCAACTTCCACTAC-3′ (F) and 5′-GACTCTTGGTGAAGCCTTGC-3′ (R); VDR, 5′-GCCCACCATAAGACCTACGA-3′ (F) and 5′-AGATTGGGAAGCTGGACGA-3′ (R); OC, 5′-CATGAGAGCCCTCACACTCC-3′ (F) and 5′-CAGCAGAGCGACACCCTAGACC-3′ (R); CYP24, 5′-TGAACGTTGGCTTCAGGAGAA-3′ (F) and 5′-AGGGTGCCTGAGTGTAGCATCT-3′ (R); GAPDH, 5′-AGAACATCATCCCTGCCTC-3′ (F) and 5′-GCCAAATTCGTTGTCATACC-3′ (R). The amplification of specific DNA regions was monitored by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining.

ChIP assays

HEK293 cells were grown on a 60-mm dish in the absence or presence of 10−8 m of D3 ligand. After 24 h of treatment, ChIP assay was performed using the ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY) as instructed by manufacturer’s protocol. We used anti-VDR (sc-1008; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and anti-SMRT (sc-1610, Santa Cruz) antibodies for immunoprecipitation of endogenous VDR and SMRT proteins. The primer sets used in ChIP assays are as follows: region I, 5′-CCGGCTGA CCTCATCTCCTG-3′ (F) and 5′-GCTGAGCTCTAGGGGAGTCT-3′ (R); region II, 5′-TCAGCCAGTGCTCAACCTGA-3′ (F) and 5′-TGTGCCCAGCGATGAGGAGG-3′ (R); β-actin, 5′-GAGACCTTCAACACCCCAGCC-3′ (F) and 5′-CCGTCAGGCA GCTCATAGCTC-3′ (R).

Yeast two-hybrid test

Yeast strain EGY48 (65) containing the pSH18-34 plasmid (8×lexAop-LacZ reporter) (66) or the pLGZ-3×VDRE plasmid was cotransformed with bait plasmids expressing the LexA-fused NR (cloned into pEG202 or pRS325LexA) and prey vectors expressing N-CoR/SMRT-ID fusions between B42 and GBD by the standard lithium-acetate method (67). Plate and liquid assays for β-galactosidase activity of three or more transformants were carried out as described elsewhere (61). Similar results were obtained with multiple repeated experiments.

Mutagenic PCR and one- plus two-hybrid screening

Random mutagenesis of the S1 fragment was performed as described previously (51). The mutagenic PCR products of the S1 region were obtained by PCR with oligo-SF and oligo-SR, using pRS424UB42-S1-GBD as the template. The yeast strain YOK400 (MATα, leu2, trp3, ura3, lexAop-LEU2, UASGAL-HIS3) for the one- plus two-hybrid screening was prepared as reported previously (51). To construct the mutant-allele library for S1 in yeast cells, we used a single-step method based on in vivo gap repair as described previously (51). Each of the mutagenic PCR products (1 μg) was cotransformed with the gap plasmid (4 μg) into strain YOK400 carrying the pSH18-34 reporter, as well as the bait plasmids pRS325LexA-VDR. His+ transformants were picked onto plate media containing X-gal, and the yeast colonies showing a white or weak blue color were isolated from among the wild-type blue colonies. Prey vectors were rescued and individually transformed into the EGY48 strain expressing LexA-VDR, as well as the EGY-LG strain containing the pLGSD5 plasmid (UASGAL-LacZ reporter) (68). Prey plasmids that still conferred blue color in the one-hybrid test and white color in the two-hybrid test were chosen as the final mutant candidates and subjected to DNA sequencing to identify the mutational site(s).

Site-directed mutagenesis

To make single-point mutations in the IDs of corepressors and the ID1 of the S1/2 construct, site-directed mutagenesis was performed by the sequential PCR method with overlap extension (69). The final PCR products were sequenced to confirm the mutations and then cloned into appropriate vectors for use in in vivo and in vitro studies. Site-directed mutagenesis to generate ID1 mutants of full-length mouse SMRTα was performed using pCMXflag-mSMRT as template and the Muta-Direct site-directed mutagenesis kit (iNTRON Biotech, Seongnam, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer sequence used for mutagenesis will be provided upon request. All clones were subjected to sequencing to confirm the mutations.

In vitro GST pull-down assay

Detailed information for the purification of GST alone and GST-fused NR proteins as well as the in vitro translation of corepressor-ID fragments using pcDNA3HA-based ID constructs were described in our previous report (51). The same protocol was applied for the in vitro translation of pCMXflag-mSMRT fl or its ID1 mutants. The radiolabeled corepressor-ID or mSMRT proteins were added to similar amounts of GST or GST-fused NRs (2–4 μg) bound to glutathione-agarose beads pre-equilibrated with buffer A [150 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 5% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1× protease inhibitor, 0.01% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm KCl] in a final volume of 250 μl. The beads were washed three times in the same buffer, and the bound radiolabeled proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Makoto Makishima (Nihon University, Tokyo, Japan), Dr. Jeong-Tae Koh (Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea), Dr. Ronald M. Evans (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA), and Dr. Ho-Geun Yoon (Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea) for providing plasmids and reagents.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Coregulators: VDR.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grant J03003 from The Korea Research Foundation (to Y.C.L.). J.Y.K and Y.L.S are supported in part by the Second Stage BK21 Program.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online December 19, 2008

Abbreviations: ChIP, Chromatin immunoprecipitation; CoRNR, corepressor-nuclear receptor; CYP24, vitamin D3 24-hydroxylase; D3, vitamin D [1α,25(OH)2D3]; F, forward; GBD, Gal4-DNA binding domain; HA, hemagglutinin; HDAC, histone deacetylase; ID, interaction domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; N-CoR, nuclear receptor corepressor; NR, nuclear receptor; N1, N-CoR-ID1; N2, N-CoR-ID2; N3, N-CoR-ID3; OC, osteocalcin; R, reverse; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; RXR, retinoid X receptor; siRNA, small interference RNA; siSMRT, siRNA against SMRT; SMRT, silencing mediator for the retinoid and thyroid hormone receptor; S1, SMRT-ID1; S2, SMRT-ID2; TR, thyroid hormone receptor; VDR, vitamin D [1α,25(OH)2D3] receptor; VDRE, vitamin D response element; X-gal, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside.

References

- 1.Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G1995. Steroid hormone receptors: many actors in search of a plot. Cell 83:851–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW2002. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell 108:465–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM1995. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell 83:835–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chawla A, Repa JJ, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ2001. Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science 294:1866–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao J, Ozono K, Sone T, McDonnell DP, Pike JW1990. Vitamin D receptor interaction with specific DNA requires a nuclear protein and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:9751–9755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald PN, Haussler CA, Terpening CM, Galligan MA, Reeder MC, Whitfield GK, Haussler MR1991. Baculovirus-mediated expression of the human vitamin D receptor. Functional characterization, vitamin D response element interactions, and evidence for a receptor auxiliary factor. J Biol Chem 266:18808–18813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu VC, Delsert C, Andersen B, Holloway JM, Devary OV, Naar AM, Kim SY, Boutin JM, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG1991. RXRβ: a coregulator that enhances binding of retinoic acid, thyroid hormone, and vitamin D receptors to their cognate response elements. Cell 67:1251–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM1992. Retinoid X receptor interacts with nuclear receptors in retinoic acid, thyroid hormone and vitamin D3 signalling. Nature 355:446–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlberg C1995. Mechanisms of nuclear signalling by vitamin D3 Interplay with retinoid and thyroid hormone signalling. Eur J Biochem 231:517–527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owen TA, Aronow M, Shalhoub V, Barone LM, Wilming L, Tassinari MS, Kennedy MB, Pockwinse S, Lian JB, Stein GS1990. Progressive development of the rat osteoblast phenotype in vitro: reciprocal relationships in expression of genes associated with osteoblast proliferation and differentiation during formation of the bone extracellular matrix. J Cell Physiol 143:420–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKee MD, Glimcher MJ, Nanci A1992. High-resolution immunolocalization of osteopontin and osteocalcin in bone and cartilage during endochondral ossification in the chicken tibia. Anat Rec 234:479–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desbois C, Hogue DA, Karsenty G1994. The mouse osteocalcin gene cluster contains three genes with two separate spatial and temporal patterns of expression. J Biol Chem 269:1183–1190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison NA, Shine J, Fragonas JC, Verkest V, McMenemy ML, Eisman JA1989. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D-responsive element and glucocorticoid repression in the osteocalcin gene. Science 246:1158–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvallo L, Henriquez B, Paredes R, Olate J, Onate S, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein GS, Stein JL, Montecino M2008. 1α,25-Dihydroxy vitamin D3-enhanced expression of the osteocalcin gene involves increased promoter occupancy of basal transcription regulators and gradual recruitment of the 1α,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 receptor-SRC-1 coactivator complex. J Cell Physiol 214:740–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison N, Eisman J1993. Role of the negative glucocorticoid regulatory element in glucocorticoid repression of the human osteocalcin promoter. J Bone Miner Res 8:969–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lian JB, Shalhoub V, Aslam F, Frenkel B, Green J, Hamrah M, Stein GS, Stein JL1997. Species-specific glucocorticoid and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D responsiveness in mouse MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts: dexamethasone inhibits osteoblast differentiation and vitamin D down-regulates osteocalcin gene expression. Endocrinology 138:2117–2127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvallo L, Henriquez B, Olate J, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein GS, Onate S, Stein JL, Montecino M2007. The 1α,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 receptor preferentially recruits the coactivator SRC-1 during up-regulation of the osteocalcin gene. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 103:420–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lian JB, Stein GS, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ1999. Regulated expression of the bone-specific osteocalcin gene by vitamins and hormones. Vitam Horm 55:443–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Endres B, DeLuca HF2001. 26-Hydroxylation of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 does not occur under physiological conditions. Arch Biochem Biophys 388:127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutton AL, MacDonald PN2003. Vitamin D: more than a “bone-a-fide” hormone. Mol Endocrinol 17:777–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaisanen S, Dunlop TW, Frank C, Carlberg C2004. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation to monitor 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-dependent chromatin activity on the human CYP24 promoter. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 89–90:277–279 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Chen KS, DeLuca HF1995. Cloning of the human 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3 24-hydroxylase gene promoter and identification of two vitamin D-responsive elements. Biochim Biophys Acta 1263:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaisanen S, Dunlop TW, Sinkkonen L, Frank C, Carlberg C2005. Spatio-temporal activation of chromatin on the human CYP24 gene promoter in the presence of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 J Mol Biol 350:65–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rochel N, Wurtz JM, Mitschler A, Klaholz B, Moras D2000. The crystal structure of the nuclear receptor for vitamin D bound to its natural ligand. Mol Cell 5:173–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YY, Nguyen C, Peleg S2000. Regulation of ligand-induced heterodimerization and coactivator interaction by the activation function-2 domain of the vitamin D receptor. Mol Endocrinol 14:1776–1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naar AM, Beaurang PA, Zhou S, Abraham S, Solomon W, Tjian R1999. Composite co-activator ARC mediates chromatin-directed transcriptional activation. Nature 398:828–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rachez C, Lemon BD, Suldan Z, Bromleigh V, Gamble M, Naar AM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Freedman LP1999. Ligand-dependent transcription activation by nuclear receptors requires the DRIP complex. Nature 398:824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen JD, Evans RM1995. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 377:454–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horlein AJ, Naar AM, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Gloss B, Kurokawa R, Ryan A, Kamei Y, Soderstrom M, Glass CK1995. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature 377:397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polly P, Herdick M, Moehren U, Baniahmad A, Heinzel T, Carlberg C2000. VDR-Alien: a novel, DNA-selective vitamin D3 receptor-corepressor partnership. FASEB J 14:1455–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lempiainen H, Molnar F, Macias Gonzalez M, Perakyla M, Carlberg C2005. Antagonist- and inverse agonist-driven interactions of the vitamin D receptor and the constitutive androstane receptor with corepressor protein. Mol Endocrinol 19:2258–2272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potter GB, Zarach JM, Sisk JM, Thompson CC2002. The thyroid hormone-regulated corepressor hairless associates with histone deacetylases in neonatal rat brain. Mol Endocrinol 16:2547–2560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh JC, Sisk JM, Jurutka PW, Haussler CA, Slater SA, Haussler MR, Thompson CC2003. Physical and functional interaction between the vitamin D receptor and hairless corepressor, two proteins required for hair cycling. J Biol Chem 278:38665–38674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potter GB, Beaudoin 3rd GM, DeRenzo CL, Zarach JM, Chen SH, Thompson CC2001. The hairless gene mutated in congenital hair loss disorders encodes a novel nuclear receptor corepressor. Genes Dev 15:2687–2701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dwivedi PP, Muscat GE, Bailey PJ, Omdahl JL, May BK1998. Repression of basal transcription by vitamin D receptor: evidence for interaction of unliganded vitamin D receptor with two receptor interaction domains in RIP13δ1. J Mol Endocrinol 20:327–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jepsen K, Rosenfeld MG2002. Biological roles and mechanistic actions of co-repressor complexes. J Cell Sci 115:689–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu X, Lazar MA2000. Transcriptional repression by nuclear hormone receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab 11:6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heinzel T, Lavinsky RM, Mullen TM, Soderstrom M, Laherty CD, Torchia J, Yang WM, Brard G, Ngo SD, Davie JR, Seto E, Eisenman RN, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG1997. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387:43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishizuka T, Lazar MA2005. The nuclear receptor corepressor deacetylase activating domain is essential for repression by thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 19:1443–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen RN, Brzostek S, Kim B, Chorev M, Wondisford FE, Hollenberg AN2001. The specificity of interactions between nuclear hormone receptors and corepressors is mediated by distinct amino acid sequences within the interacting domains. Mol Endocrinol 15:1049–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makowski A, Brzostek S, Cohen RN, Hollenberg AN2003. Determination of nuclear receptor corepressor interactions with the thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 17:273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webb P, Anderson CM, Valentine C, Nguyen P, Marimuthu A, West BL, Baxter JD, Kushner PJ2000. The nuclear receptor corepressor (N-CoR) contains three isoleucine motifs (I/LXXII) that serve as receptor interaction domains (IDs). Mol Endocrinol 14:1976–1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu X, Lazar MA1999. The CoRNR motif controls the recruitment of corepressors by nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 402:93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagy L, Kao HY, Love JD, Li C, Banayo E, Gooch JT, Krishna V, Chatterjee K, Evans RM, Schwabe JW1999. Mechanism of corepressor binding and release from nuclear hormone receptors. Genes Dev 13:3209–3216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perissi V, Staszewski LM, McInerney EM, Kurokawa R, Krones A, Rose DW, Lambert MH, Milburn MV, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG1999. Molecular determinants of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction. Genes Dev 13:3198–3208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu HE, Stanley TB, Montana VG, Lambert MH, Shearer BG, Cobb JE, McKee DD, Galardi CM, Plunket KD, Nolte RT, Parks DJ, Moore JT, Kliewer SA, Willson TM, Stimmel JB2002. Structural basis for antagonist-mediated recruitment of nuclear co-repressors by PPARα. Nature 415:813–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen RN, Putney A, Wondisford FE, Hollenberg AN2000. The nuclear corepressors recognize distinct nuclear receptor complexes. Mol Endocrinol 14:900–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zamir I, Harding HP, Atkins GB, Horlein A, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Lazar MA1996. A nuclear hormone receptor corepressor mediates transcriptional silencing by receptors with distinct repression domains. Mol Cell Biol 16:5458–5465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu X, Li Y, Lazar MA2001. Determinants of CoRNR-dependent repression complex assembly on nuclear hormone receptors. Mol Cell Biol 21:1747–1758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu X, Li S, Wu J, Xia C, Lala DS2003. Liver X receptors interact with corepressors to regulate gene expression. Mol Endocrinol 17:1019–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JY, Park OG, Lee JW, Lee YC2007. One plus two-hybrid system: a novel yeast genetic method to select for specific missense mutations disrupting protein-protein interactions. Mol Cell Proteomics 6:1727–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen JD, Umesono K, Evans RM1996. SMRT isoforms mediate repression and anti-repression of nuclear receptor heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:7567–7571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tagami T, Lutz WH, Kumar R, Jameson JL1998. The interaction of the vitamin D receptor with nuclear receptor corepressors and coactivators. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 253:358–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kerry DM, Dwivedi PP, Hahn CN, Morris HA, Omdahl JL, May BK1996. Transcriptional synergism between vitamin D-responsive elements in the rat 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase (CYP24) promoter. J Biol Chem 271:29715–29721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cadwell RC, Joyce GF1992. Randomization of genes by PCR mutagenesis. PCR Methods Appl 2:28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muhlrad D, Hunter R, Parker R1992. A rapid method for localized mutagenesis of yeast genes. Yeast 8:79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J, Malloy PJ, Feldman D2007. Interactions of the vitamin D receptor with the corepressor hairless: analysis of hairless mutants in atrichia with papular lesions. J Biol Chem 282:25231–25239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fleet JC, Hock JM1994. Identification of osteocalcin mRNA in nonosteoid tissue of rats and humans by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Bone Miner Res 9:1565–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jung C, Ou YC, Yeung F, Frierson Jr HF, Kao C2001. Osteocalcin is incompletely spliced in non-osseous tissues. Gene 271:143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Petrucci M, Paquette Y, Leblond FA, Pichette V, Bonnardeaux A2006. Evidence that the mouse osteocalcin-related gene does not encode nephrocalcin. Nephron Exp Nephrol 104:e140–146 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Na SY, Choi JE, Kim HJ, Jhun BH, Lee YC, Lee JW1999. Bcl3, an IκB protein, stimulates activating protein-1 transactivation and cellular proliferation. J Biol Chem 274:28491–28496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Forman BM, Umesono K, Chen J, Evans RM1995. Unique response pathways are established by allosteric interactions among nuclear hormone receptors. Cell 81:541–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gutierrez S, Liu J, Javed A, Montecino M, Stein GS, Lian JB, Stein JL2004. The vitamin D response element in the distal osteocalcin promoter contributes to chromatin organization of the proximal regulatory domain. J Biol Chem 279:43581–43588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoon HG, Chan DW, Huang ZQ, Li J, Fondell JD, Qin J, Wong J2003. Purification and functional characterization of the human N-CoR complex: the roles of HDAC3, TBL1 and TBLR1. EMBO J 22:1336–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Estojak J, Brent R, Golemis EA1995. Correlation of two-hybrid affinity data with in vitro measurements. Mol Cell Biol 15:5820–5829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R1993. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell 75:791–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol 153:163–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guarente L, Yocum RR, Gifford P1982. A GAL10-CYC1 hybrid yeast promoter identifies the GAL4 regulatory region as an upstream site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79:7410–7414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki RK1988. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 16:7351–7367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]