Abstract

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) is a key factor necessary for osteoclast differentiation and activation. Mutations within the TNF-like core domain of RANKL have been recently reported in patients with osteoclast-poor autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. However, the functional consequence owing to RANKL mutations has not been well characterized. Here we describe the functional propensity of RANKL mutants in osteoclast differentiation and their impact on RANKL-mediated signaling cascades. Recombinant RANKL (rRANKL) mutants within the TNF-like core domain exhibited diminished osteoclastogenic potential as compared with wild-type rRANKL1 encoding the full TNF-like core domain [amino acids (aa) 160–318]. Consistent with the insufficient activities on osteoclastogenesis, rRANKL mutants showed reduced activation of nuclear factor-κB, IκBα degradation, and ERK phosphorylation. In addition, we found that rRANKL mutants interfered with wild-type rRANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis with deletion mutant rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) exhibiting the greatest inhibitory effect. The same mutant also significantly reduced wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318)-induced osteoclastic bone resorption in vitro. BIAcore assays demonstrated that rRANKL5 alone, lacking the AA″ and CD loops, weakly binds to receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK). Intriguingly, preincubation of mutant rRANKL5 with rRANKL1 before exposure to RANK enhanced the maximal binding level to RANK, indicating that rRANKL5 forms hybrid trimeric complexes with rRANKL1. Furthermore, RANKL mutant mimicking human RANKL V277 mutation in patients, impairs osteoclast differentiation and signaling. Taken together, these data lend support to the notion that the TNF-like core domain of RANKL contains structural determinants that are crucial for osteoclast differentiation and activation, thus providing a possible mechanistic explanation for the observed phenotype in osteopetrotic patients harboring RANKL mutations.

Recombinant rRANKL mutants within the TNF-like core domain form short-lived hybrid trimeric complexes with wildtype RANKL, thus inhibiting RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption.

Osteoclasts are large multinucleated cells that are exclusively responsible for the degradation of bone matrix. They are formed by the fusion of precursor cells derived from the monocyte-macrophage lineage (1). Overproduction and/or activation of osteoclasts is a hallmark of several debilitating osteolytic disorders including osteoporosis, Paget’s disease, cancer metastasis to bone, arthritis, and aseptic bone loosening. The receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) ligand (RANKL) (2), also known as osteoprotegerin ligand (3), TNF-related activation-induced cytokine (4), or osteoclast differentiation factor (5) is essential for osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Mice deficient in RANKL gene exhibit severe osteopetrosis and defective tooth eruption and completely lack osteoclasts as a result of the failure of osteoblasts to support osteoclastogenesis (6). Furthermore, RANKL has been shown to play a role in dendritic cell survival (2, 4, 7), mammary gland development (8), lymph node organogenesis, and lymphocyte development (6). In addition to its established role in osteoclast physiology, RANKL has been implicated in the migration and metastatic behavior of cancer cells (9). Elevated RANKL expression has also been documented in several pathological bone diseases, including giant cell tumor of bone (10), periodontal disease (11), nonunion fracture (12), and multiple myeloma (13). Thus, RANKL and its signaling pathways have been proposed as therapeutic targets in the management of osteolytic bone diseases (14, 15).

RANKL is a type II transmembrane protein that consists of a short N-terminal cytoplasmic domain and a conserved extracellular receptor-binding domain that defines this molecule as a member of the TNF family (3, 5, 16). The receptor-binding domain consists of an antiparallel β-sheet that is predicted to assemble into a trimer required for receptor activation (17, 18). Recently, RANKL mutations have been identified in patients with osteoclast-poor autosomal recessive osteopetrosis (19). Interestingly, these RANKL mutations were localized within its TNF-like core domain [amino acids (aa) 160–318]. Mutation V277 resulted in a frameshift at aa 277 and a premature stop codon within the TNF-like core domain, which consequently leads to a truncated RANKL mutant. Mutant del145–177AA has an in-frame deletion of aa 145–177, which occurs at the end-terminal region of TNF-like core region. The M199K mutant introduces an aa substitution (Met199Lys change) in the midregion TNF-like core domain (19). Taken together, these functional mutations within the TNF-like core domain suggest that this region encodes essential structural determinants required for osteoclast differentiation and may represent a mutational hot spot in osteoclast-poor osteopetrotic patients.

In light of the recent findings that mutations within the TNF-like core domain of RANKL have been identified in patients with osteopetrosis, we predicted that disruption and/or deletion of this domain may impair RANKL-mediated osteoclast formation. Here, we generated a series of mutants within the TNF-like core domain of RANKL and investigated their inductive potential on osteoclast formation, affinity to receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK), and activation of its associated signaling pathways. Our results indicate that mutations within the TNF-like core domain of RANKL drastically reduce osteoclastogenic potential in vitro, reminiscent of the condition observed in RANKL mutant patients. These findings correlate with biochemical evidence that RANKL mutants fail to fully support key osteoclastic signaling pathways including NF-κB, IκBα, and ERK as well as the gene expression of functional osteoclastic proteins, calcitonin receptor, and cathepsin K. In addition, we provide evidence to suggest that RANKL mutants might potentially serve as peptide mimics that can interfere with RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Our data corroborate the recent findings of Sobacchi et al. (19) that the TNF-like core domain encodes the major structural determinants responsible for osteoclast formation and activation.

Results

Mutations within the TNF-like core domain of RANKL impair osteoclastogenesis

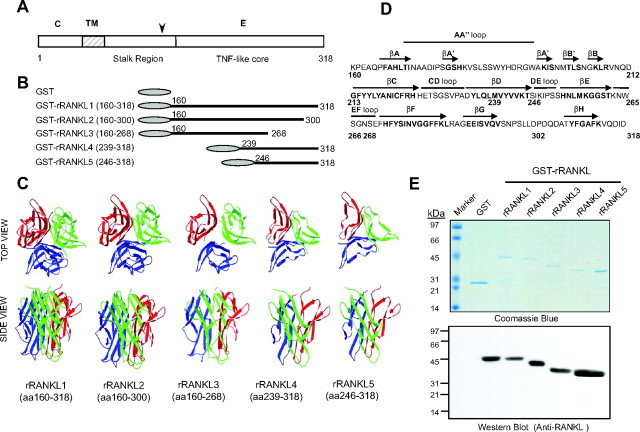

Previous structural analyses suggest that the TNF-like core domain of RANKL (aa 160–318) is essential for osteoclastogenesis; however, this notion has yet to be validated experimentally (3, 16). To study the structure and function of the TNF-like core domain of RANKL, we generated a series of truncation mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), and rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) and expressed them as glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins (Fig. 1, A and B). Based on the crystal structure of RANKL (17, 18), each RANKL mutant protein exhibits distinct structural characteristics due to the various truncation mutations on the TNF-like core domain (Fig. 1, C and D). As shown in Fig. 1, B and C, rRANKL2 (aa 160–300) carried a deletion of βH strand on the C terminus of the TNF-like core domain. Mutant rRANKL3 (aa 160–268) carried a deletion of βF, βG, and βH strands, also at the C terminus of the TNF-like core domain. Mutant rRANKL4 (aa 239–318) had a deletion of βA, AA″ loop, βB′ and βB, βC, and CD loop, whereas mutant rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) had a deletion of βA, AA″ loop, βB′ and βB, βC, CD loop, and βD. Both deletions are on the N-terminal end of the TNF-like core domain. Recombinant rRANKL mutants, together with the wild-type protein rRANKL1 (aa 160–318), were affinity-purified to greater than 95% purity as determined by SDS-PAGE, and confirmed by Western blot analysis using a specific monoclonal antibody to RANKL (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Structure of rat rRANKL and expression of rat rRANKL mutants within the TNF-like core domain. A, Schematic representation of the structure of rRANKL. C, Cytoplasmic region; TM, transmembrane region; E, extracellular region; arrowhead, the potential TNF-α-converting enzyme TACE cleavage site. B, rRANKL and rRANKL mutant cDNA fragments cloned into the pGEX expression vectors and purified. C, Predicted crystal structures of RANKL mutants based on the crystal structure of wild-type RANKL. Both top view and side view of trimeric structures of RANKL mutants are shown. D, Structure determinants of TNF-like core domain of rat RANKL based on the crystal structure of mouse RANKL. Secondary structure assignments for TNF-like core domain are depicted above the sequence. The 10 β-strands that form the TNF family β sandwich are shown as arrows. The aa residues of mutants are indicated. E, Coomassie blue-stained polyacrylamide gel showing the affinity-purified rat rRANKL fusion proteins expressed in Escherichia coli (top panel), and an autoradiagraph showing that a monoclonal antibody to RANKL specifically interacts with the affinity-purified GST-rRANKL fusion proteins by Western blot analysis (bottom panel).

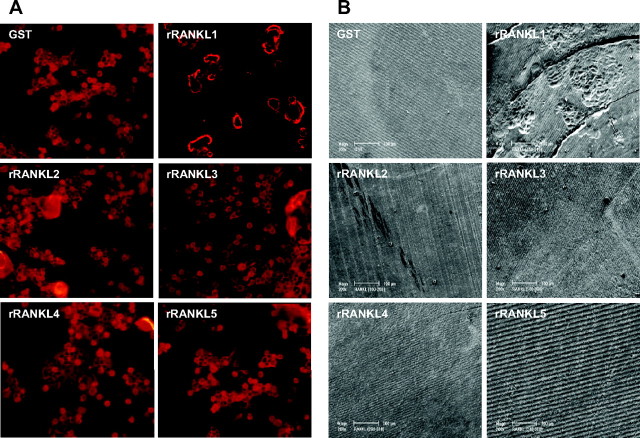

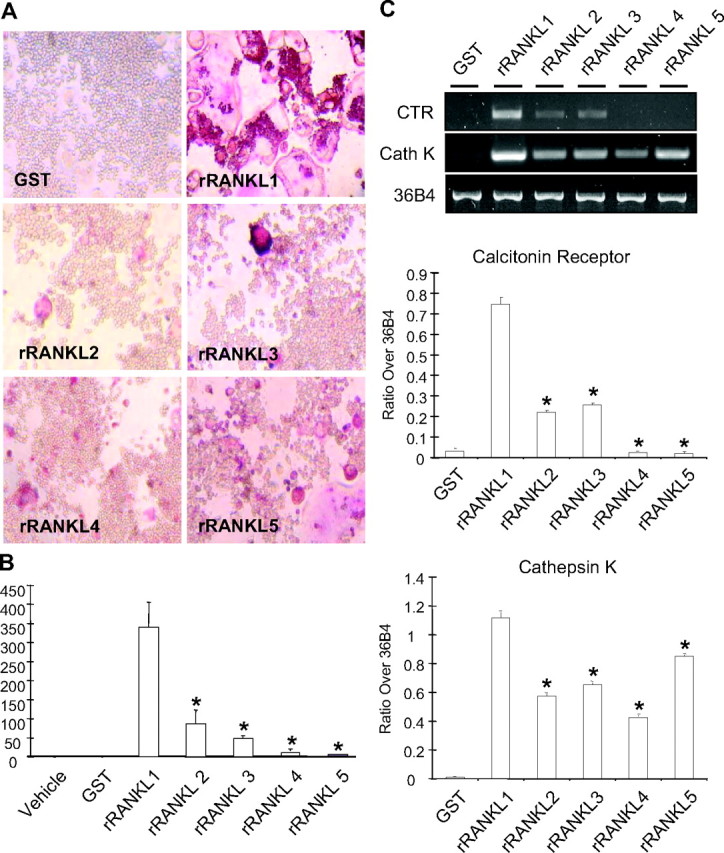

To test whether RANKL mutants induce osteoclast formation in vitro, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with either wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318) or truncation mutants. After 5 d, cells were fixed and stained with tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) to assess potential osteoclastogenesis. As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), and rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) induced lower levels of osteoclast-like cell (OCL) formation compared with wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318). The treatment with GST alone showed no TRAP-positive cells. Similar effects were observed in osteoclasts derived from bone marrow monocytes (data not shown). In addition, the TRAP-positive multinucleated cells generated by RANKL mutants were morphologically smaller and exhibited less multinucleation as compared with osteoclasts formed in the presence of the wild-type rRANKL1 protein (Fig. 2A). As expected, the observed reduction in osteoclastogenesis correlated with a decrease in the mRNA expression of mature osteoclast markers such as calcitonin receptor and cathepsin K (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

RANKL mutant lacks osteoclastogenesis induction potential. A, Representative images of RAW264.7 cell cultures stained for TRAP activity. Note that full-length rRANKL1 induces the formation of well-spread, TRAP-positive multinucleated (≥3 nuclei) OCLs. rRANKL mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), and rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) generated much less TRAP-positive multinucleated (≥3 nuclei) cells that are smaller in size and lacking the characteristic morphology of osteoclasts. GST alone did not induce the formation of TRAP-positive cells. B, Graphical representation of the total numbers of TRAP-positive multinucleated (≥3 nuclei) cells from RAW264.7 cells treated with 100 ng/ml of mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), rRANKL5 (aa 246–318), wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318), or GST control. The results represent three experiments with triplicate wells per experiment (*, P < 0.001). C, Semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses showing the lack of inductive effect of rRANKL mutants on the gene expression of calcitonin receptor and cathepsin K. The result is a representation of three experiments (*, P < 0.001). Cath K, Cathepsin K; CTR, calcitonin receptor.

RANKL mutants do not support osteoclastic polarization and bone resorption in vitro

In addition to its function in osteoclast formation, RANKL is also known to support osteoclast activation and function during bone resorption (16). Given as such we next examined whether the OCLs formed by RANKL truncation mutants were capable of sustaining the cellular activation required for functional bone resorption. For this purpose, RAW264.7 cells were directly cultured on bone slices in the presence of rRANKL1 or rRANKL mutants and examined for their ability to form F-actin rings and resorption pits, characteristic of osteoclast polarization and activation. RAW264.7 cells were continuously stimulated for up to 15 d with rRANKL1 or rRANKL mutants to allow for maximal OCLs formation and subsequent bone resorption. After 15 d OCLs formed on bone slices were fixed, stained with Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin, and processed for confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3A, multinucleated OCLs derived from wild-type rRANKL1 formed typical F-actin rings highlighting the sealing zones of actively resorbing cells. On the other hand, OCLs derived from the RANKL mutants failed to support F-actin ring formation. The inability of RANKL mutants to sustain structural integrity of the F-actin ring and functional polarization of osteoclasts was further evidenced by the lack of bone resorption as revealed by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 3B). Whereas OCLs derived from the wild type exhibited numerous resorptive pits, little to no resorptive activity could be detected by OCLs derived from RANKL mutants. Taken together, these results imply that mutations within the TNF-like domain of RANKL, although able to induce to some extent formation of smaller, less multinucleated TRAP-positive cells, are unable to support osteoclast activation and thus bone resorption.

Fig. 3.

OCLs induced by rRANKL mutants lack F-actin ring formation and bone resorption activities. RAW264.7 cells were directly seeded on bovine bone slices and continuously cultured in the presence of wild-type rRANKL, rRANKL mutants, or GST proteins as a control for 15 d. After 15 d, cell were fixed and stained with F-actin and examined by confocal microscope (A). B, Bone slices from panel A were also examined for bone pit formation by scanning electron microscope.

RANKL mutants impair key osteoclastic signaling pathways: NF-κB, IκBα, and ERK

As an initial step toward validating the biological activity of GST-RANKL mutants, their ability to associate with their cognate receptor RANK was assessed using in vitro GST-pull down assays (refer to Materials and Methods). Surprisingly, despite their structurally anomalies all rRANKL mutants (aa 160–300, aa 160–268, aa 239–318, and aa 246–318) were capable of binding to RANK albeit with different levels of RANK precipitation (supplemental Fig. 1 published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). Predictably, full-length rRANKL1 (aa 160–318) exhibited strongest binding to Flag-RANK (aa 34–616) followed by rRANKL3 mutant (aa 160–268) > rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) mutant. rRANKL2 (aa 160–300) and rRANKL4 (aa 239–318) mutants exhibited the weakest binding, suggesting that selective C- and N-terminal residues of the TNF-like core domain may be important for RANKL trimerization and binding to RANK.

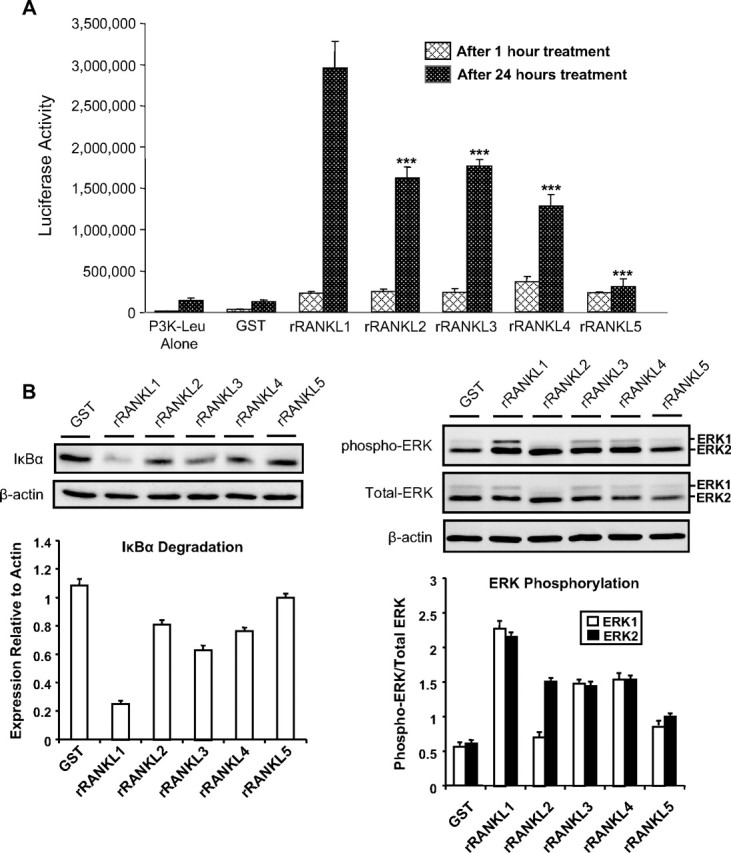

Next, we investigated whether rRANKL mutants have some detectable effect on known downstream signaling pathways of RANK. It is well established that, upon activation, RANK recruits members of the TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF) adapter proteins including TRAF6 and TRAF2, which are subsequently involved in the activation of NF-κB, ERK, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (20, 21, 22, 23). To assess NF-κB activation, RAW264.7 cells stably expressing a 3κB-Luc-SV40 (22) were stimulated with 200 ng/ml of wild-type rRANKL1 and the mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), and rRANKL5 (aa 246–318), and lysates harvested at 1 h and 24 h after stimulation, respectively. NF-κB activities were measured by luciferase assay. As shown in Fig. 4A, all rRANKL mutants were capable of differentially inducing NF-κB activation, albeit to a significantly lower extent as compared with full-length rRANKL1 (aa 160–318). Mutant rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) exhibited least induction potential of NF-κB transcriptional activity. GST protein alone exhibited no significant effect on NF-κB activity (Fig. 4A) and served as an internal control. To exclude the possibility that the reduced effects of RANKL mutants on NF-κB activation was not a reflection of potential endotoxin contamination, we also performed an endotoxin assay (data not shown). Notably, all recombinant rRANKL mutants and GST displayed comparable levels of endotoxin (24–86 pg/ml in stock which was diluted at least 1:100 for a final working concentration), thereby ruling out the possibility that that the observed activation of NF-κB induced by rRANKL mutants was not due to endotoxin contamination.

Fig. 4.

RANK-signaling pathway induction by rRANKL mutants. A, RAW264.7 cells stably transfected with the 3kB-Luc-SV40 (P3K-Leu) reporter gene were treated with 200 ng/ml of GST, mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), rRANKL5 (aa 246–318), or wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318). The luciferase activity was measured at 1 and 24 h after treatment. Note that the RANKL mutants have reduced effects on the activation of NF-κB compared with the full-length rRANKL1, whereas GST control has no effects. B, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 200 ng/ml of GST, mutants rRANKL2, rRANKL3, rRANKL4, and rRANKL5, or wild-type rRANKL1. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analyses using IκBα, total and phosphorylated ERK, and β-actin antibodies. The results represent three independent experiments.

Next, we turned our attention to the potential effects of rRANKL mutants on IκBα degradation and ERK phosphorylation. To this end, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with rRANKL mutants, wild-type rRANKL1, or GST for 20 min (IκBα) or 30 min (ERK), before being harvested and processed for immunoblotting (refer to Material and Methods). As shown in Fig. 4B, mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), and rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) exhibit impaired IκBα degradation and ERK phosphorylation potential as compared with wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318). Again it appears that rRANKL5 mutant (aa 246–318) has the least potential for the induction of IκBα degradation and ERK phosphorylation, indicating that the AA″ and CD loops of the TNF-like core domain of RANKL are important for the activation of RANK signaling pathways.

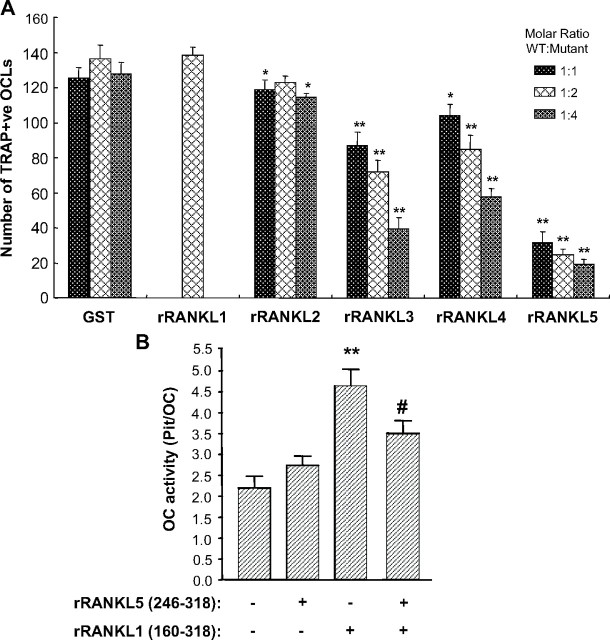

AA″ and CD loop deletion mutant (rRANKL5) interferes with RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption

Having demonstrated that deletion mutants of RANKL significantly impair osteoclast formation, activation, and bone resorption, we next asked whether the same mutants may interfere with wild-type rRANKL-induced differentiation, activation, and function of osteoclasts. To explore this possibility, the effect of rRANKL mutants on rRANKL1-induced osteoclastogenesis was first examined using RAW264.7 cell cultures. For this purpose, RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with various concentrations of mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), and rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) up to 1 h before the addition of wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318) (100 ng/ml). After 5 d of culture, cells were fixed and TRAP stained, and resulting OCLs were quantified. As shown in Fig. 5A, RAW264.7 cell cultures pretreated with rRANKL mutants displayed significantly fewer OCLs as compared with RAW264.7 cells cultured in the presence of either wild-type rRANKL1 alone or in combination with GST. Of the mutants tested, AA″ and CD loop deletion mutant rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) again exhibited the most potent inhibitory effects on RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. The inhibitory effect of the rRANKL mutants was still observed when the molar ratio of wild-type rRANKL1 to rRANKL mutants was reduced, i.e. 1:2 and 1:4 (50 ng/ml of rRANKL1 to 100 ng/ml of rRANKL mutants and 50 ng/ml rRANKL1 to 200 ng/ml rRANKL mutants). TRAP-positive OCLs formed in preincubation experiments with rRANKL mutants appeared morphologically smaller and exhibited fewer nuclei as compared with osteoclasts formed/derived from wild-type rRANKL1 alone or GST-pretreated groups. These results imply that all rRANKL mutants interfere with rRANKL1-induced osteoclastogenesis, with the AA″ and CD loop deletion mutant rRANKL5 displaying the most potent inhibitory effect.

Fig. 5.

Inhibitory effects of rRANKL mutants on wild-type rRANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. A, Graph representation of the total numbers of TRAP-positive multinucleated (≥3 nuclei) cells. RAW264.7 cells were treated with different doses of mutants rRANKL2 (aa 160–300), rRANKL3 (aa 160–268), rRANKL4 (aa 239–318), or rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) for 30 min before 100 ng/ml wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318) was added (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). B, The effect of mutant rRANKL5 on wild-type rRANKL1-induced osteoclastic bone resorption. Isolated rat osteoclasts (∼100 osteoclasts per slice) were cultured in the presence of rRANKL5 mutant or wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318) or both, and bone resorption pits were determined. Note that rRANKL5 mutant attenuated wild-type rRANKL1-induced bone resorption [**, significantly different from control, P < 0.01 in t test; #, significantly different from rRANKL1 (aa 160–318), P < 0.05, in t test]. The results represent three independent experiments. OC, Osteoclast; WT, wild type.

Having established that rRANKL mutants interfere with RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis, we next examined whether the same mutants could block RANKL-induced activation of mature osteoclasts during bone resorption. Given the fact that the rRANKL5 mutant (aa 246–318) exerted the most potent inhibitory effect on RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis, we chose to examine its effect on RANKL-induced osteoclastic bone resorption. To this end, primary osteoclasts were isolated from the long bones of neonatal rats and cultured on bovine bone slices in the presence of either 1) wild-type rRANKL1 (aa 160–318), 2) rRANKL5 mutant (aa 246–318), or 3) in combination. After 48 h of culture, OCLs were removed and resorptive pits were quantified. As shown in Fig. 5B, rRANKL5 significantly suppressed the bone-resorptive activity of osteoclasts even in the presence of full-length rRANKL1, indicating that this TNF mutant may serve as a peptide mimic to interfere with bone resorption in vitro.

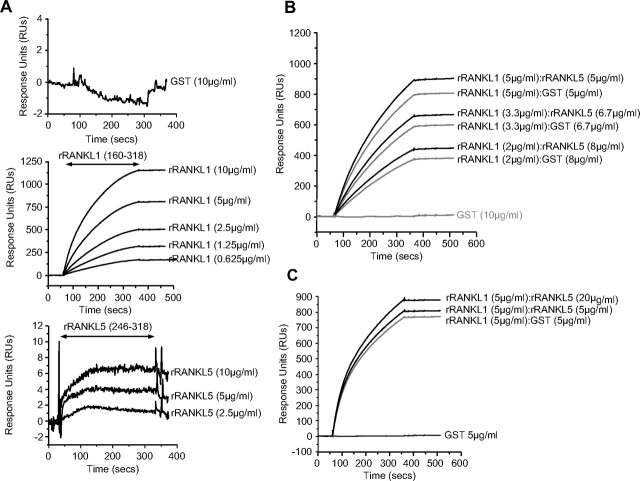

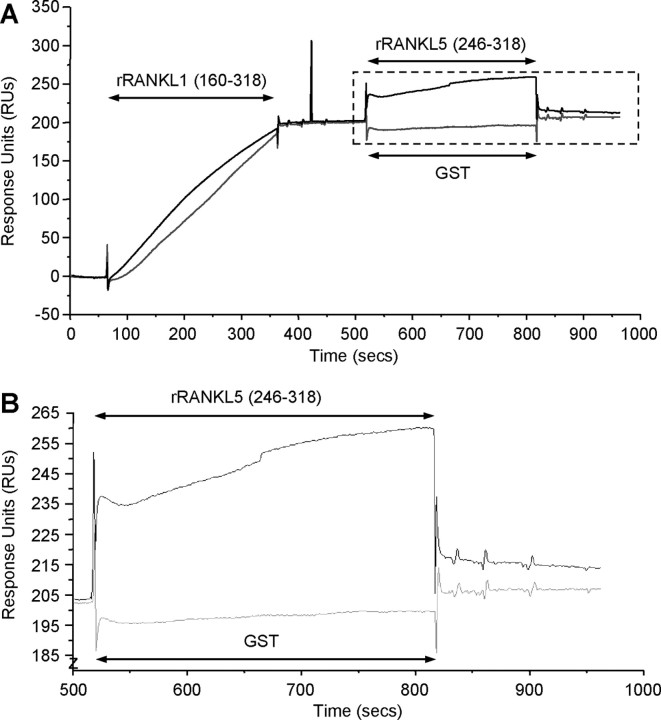

Deletion of AA″ and CD loops abrogates binding to RANK but not RANKL-RANK complex

Finally, in and attempt to examine the mechanism through which the rRANKL5 mutant (aa 246–318) was able to compete with full-length rRANKL1, we compared its ability to bind to its cognate receptor RANK using Surface Plasmon Resonance (BIAcore) analysis. Binding curves were generated from experiments in which rRANKL1 and rRANKL5 were exposed to a high-density RANK coated on a CM5 sensor chip (Fig. 6A). Differences between wild-type rRANKL1 and rRANKL5 mutant binding to RANK was evidently shown, with rRANKL1 demonstrating dose-dependent and high levels of binding to RANK with a relatively steep association curve. No dissociation of rRANKL1 from RANK was observed, suggesting that the rRANKL1-RANK interaction is relatively strong. On the other hand, the measurement obtained for rRANKL5, although dose dependent, demonstrates a very weak binding to RANK, which is below the detection level. The maximal level of binding of rRANKL5 to RANK was insignificant when compared with wild-type rRANKL1. GST at the highest concentration tested did not bind to RANK and was used as a control. Although rRANKL5 weakly binds to RANK on the cell-free BIAcore system, we cannot exclude the possibility that rRANKL5 might still interact with RANK in a kiss-and-run manner in living cell conditions.

Fig. 6.

Binding of wild-type rRANKL1 and rRANKL5 mutant to RANK using surface plasmon resonance. A, Binding curves for GST (upper panel), wild-type rRANKL1 (middle panel), and rRANKL5 mutant (lower panel) on a high-density surface of RANK-Fc. Each of the recombinant proteins was injected at concentrations of 10 μg/ml, 5 μg/ml, 2.5 μg/ml, 1.25 μg/ml, and 0.625 μg/ml. Wild-type rRANKL1 associated with RANK in a dose-dependent manner with little dissociation upon cessation of injection. Very weak association with RANK was demonstrated by rRANKL5 mutant. GST did not associate with RANK at all. B and C, Effects of preincubation of wild-type rRANKL1 with rRANKL5 mutant before exposure to RANK. B, Molar ratio of rRANKL1 to rRANKL5 was reduced (1:2 and 1:4) while maintaining the total protein concentration at 10 μg/ml. C, Increasing protein concentration of rRANKL5 while rRANKL1 protein remains at 5 μg/ml. In both situations, preincubation of rRANKL1 with rRANKL5 resulted in a higher maximal level of association with RANK as compared with preincubation with GST. The results are representative of four independent experiments. RUs, Response units.

Interestingly, when rRANKL1 was preincubated with rRANKL5 before exposure to a RANK-coupled surface, the resulting binding curves were higher than that observed for rRANKL1 + GST (Fig. 6, B and C). This enhanced level of binding was still observed when the molar ratio of rRANKL to rRANKL5 was reduced to 1:2 and 1:4 while maintaining the total protein concentration at 10 μg/ml (Fig. 6B). Increasing amounts of rRANKL5 protein concentration relative to unchanged rRANKL1 protein levels also significantly increased the maximal level of binding (Fig. 6C). The higher level of maximal binding for rRANKL1 + rRANKL5, as compared with rRANKL1 + GST, may suggest a hybrid trimeric complex formation between rRANKL1 and rRANKL5 upon binding to RANK.

Because rRANKL5 alone binds only weakly to RANK and to further investigate whether rRANKL1 is a prerequisite for rRANKL5 to bind to RANK, wild-type rRANKL1 was exposed to RANK to form rRANKL-RANK before exposure to rRANKL5 (Fig. 7). As shown in Fig. 7, rRANKL5 demonstrated significant binding to the rRANKL1-RANK complex. However, upon cessation of exposure of rRANKL5 to the rRANKL1-RANK complex, the binding curve is not maintained but immediately returns to rRANKL-RANK baseline levels, indicating that rRANKL5 easily dissociates from this hydrid complex. These data indicate that rRANKL5 may form temporary, less functional, trimeric hybrid complexes with wild-type rRANKL1-RANK and thus account for the inhibitory effect on osteoclast formation and function.

Fig. 7.

rRANKL5 mutant associates with rRANKL1-RANK complex. A, Wild-type rRANKL1 (1 μg/ml) was exposed to RANK to first allow for rRANKL1-RANK complex formation. rRANKL5 mutant (50 μg/ml) was then injected over the flow cell of rRANKL1-RANK complexes 20 sec after cessation of rRANKL1 injection. rRANKL5 was able to associate with rRANKL1-RANK complex but was easily dissociated upon cessation of injection. B, Enlarged view of dashed box from panel A. The results are representative of three independent experiments. RUs, Response units.

RANKL mutant mimicking human RANKL V277 mutation in patients impairs osteoclast differentiation and signaling

Finally, in an attempt to mimic the natural mutations that occur in the patients, we have generated the RANKL V277 mutant, which carried a mutation from aa residue V277 with four extra aa residues WWIF leading to a premature stop codon (19). After the expression and purification, we tested its biological activity and impact on osteoclast signaling. In line with our previous results, RANKL-V277 protein exhibited an attenuated efficacy for inducing osteoclastogenesis, and apparent deficits in NF-kB signaling and IκBα degradation, and ERK phosphorylation (supplemental Fig. 2). These data further attest that the TNF-like core domain of RANKL contains structural determinants that are crucial for osteoclast differentiation and signaling.

Discussion

The RANKL-RANK-TRAF6 axis plays a critical role in osteoclast differentiation and function. We report here that mutations within the TNF-like core domain of RANKL impair osteoclast formation and activation in vitro. Moreover, the observed disruption in osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption from RANKL mutants correlates with reduced activation of key RANK signaling cascades including NF-κB, IκBα, and ERK. Furthermore, RANKL mutant mimics human V277 mutation in patients, demonstrating impaired osteoclastogenesis and RANK-mediated signaling. Our results corroborate recent findings in which patients with inherited RANKL mutations develop osteopetrosis due to a lack of osteoclasts in bone biopsy specimens (19) and thus provide a possible experimental explanation as to why patients with RANKL mutants exhibit osteopetrosis.

Several lines of evidence indicate that peptide sequences (mimotopes), which mimic conformational epitopes of ligand- receptor interactions, are able to block/interfere the biological activities of their target cytokines (24, 25). More recently, a TNF receptor loop peptide mimic was reported to block RANKL-induced signaling, bone resorption, and bone loss (26). There is at least one other report suggesting the presence of naturally occurring shorter isoforms of RANKL, which by itself has little effects on the formation of preosteoclasts or osteoclasts, but significantly inhibits fusion of preosteoclasts when coexpressed with full-length RANKL (27). These findings are consistent with observations in the present study, pointing to the potential application of peptide agents for the treatment of diseases in which osteoclasts are increased or overactivated.

Structural studies on the mouse RANKL suggest that RANKL self-associates as a trimer with four unique surface loops that distinguish it from other TNF family cytokines as well as having conserved features of RANKL in the TNF superfamily (17, 18). Several residues in RANKL are predicted to be important for the ligand-receptor interaction. These residues include Ile-248 in the DE loop for conserved interaction, Gln-236 in the N-terminal region of the D strand, and Lys-180 in the AA″ loop for the specific interaction (17). All three of these residues are conserved in mouse, human, and rat RANKL (18). The rRANKL mutants rRANKL4 (aa 239–318) and rRANKL5 (aa 246–318) contain the deletion of both AA″ loop and CD loop, and the deletion of residues Lys-180 and Gln-236. The rRANKL mutant rRANKL2 (aa 160–300) carried a deletion of βH whereas rRANKL3 (aa 160–268) has a deletion of βF, βG, and βH. Although by no means proven experimentally, it is possible that the disruption of any of these loops owing to RANKL mutations could affect the trimeric formation of RANKL and/or complex formation with cognate receptor RANK and, as a result of this, affect their biological activities. Although each mutation has its own profile of activity, it remains a challenge to determine why the mutants differ in their behavior.

The binding of RANKL to RANK recruits TRAFs, which is important for the initiation of a receptor-mediated signal transduction cascade and the activation of NF-κB, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, ERK, nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase activity (2, 21, 22, 28, 29). Of particular interest of all RANKL mutants is the mutant rRANKL5 (aa 246–318), which appears to exhibit the greatest decreased effect on NF-κB activation, IκBa degradation, and ERK phosphorylation. Although the precise mechanism underlining this observation requires further investigation, it is plausible that rRANKL5 effects on RANK signaling could be the result of rRANKL-RANKL hybrid complex formation leading to reduction in functional ligand activation of receptor RANK. Studies by Lam et al. (17) have demonstrated that AA″, CD, DE, and EF loops are necessary for efficient RANK binding and subsequent activation. Deletion of the entire AA″ loop failed to induce osteoclast precursors to differentiation in vitro, whereas single aa substitution in the DE loop resulted in a 8-fold decrease in potency for inducing osteoclastogenesis (17).

Our binding studies demonstrate that rRANKL5 alone, which has the AA″ and CD loops truncated, bind only weakly to receptor RANK, which is in agreement with its structural prediction (17). On the other hand, the preincubation of mutant rRANKL5 with wild-type rRANKL1 before exposure to RANK enhanced the maximal binding level to RANK when compared with preincubation with GST. Although missing the AA″ and CD loops, rRANKL5 does contain a large number of aa residues in β-strands E, F, G, and H, which are important for homotrimerization of RANKL. It is thus possible that rRANKL5 is forming hybrid trimeric complexes with wild-type rRANKL1 to bind or associate with RANK. However, this hybrid complex between rRANKL5 and rRANKL1 is short lived because rRANKL5 easily dissociates from the rRANKL1-RANK complex. It is probable that the negative effect of rRANKL5 on RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and activation is through the formation of such hybrid trimeric structure impeding the functional activation of RANK and its downstream signaling cascades.

In summary, we have shown that recombinant rRANKL mutants within the TNF-like core domain are capable of inhibiting RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. Our study echoes the recent finding that naturally occurring RANKL mutations are responsible for the development of osteopetrosis. The impairment of bone resorption by RANKL mutants may be due, at least in part, to the formation of a short-lived hybrid trimeric structure between the mutant and wild-type RANKL.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, cell lines, and antibodies

RAW264.7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in αMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, in a humidified atmosphere chamber with 5% CO2 at 37 C. Anti-RANKL was purchased from Oncogene Research Products (Boston, MA). Goat antimouse IgG-conjugated horseradish peroxidase was obtained from Sigma (Sydney Australia). Glutathione agarose beads were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Luciferase assay systems were obtained from Promega Corp. (Sydney, Australia). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

Construction, expression, and purification of GST-RANKL (rRANKL) mutants

A series of truncation mutants (aa 160–300), (aa 160–268), (aa 239–318), and (aa 246–318) were constructed as GST fusion proteins using the pGEX expression system. DNA sequencing was carried out to confirm correct insertions of RANKL cDNA in frame with GST. To express GST fusion proteins, each plasmid containing RANKL mutations was transformed into the bacterial strain BL21. After growth in Luria Bertani broth (LB) containing 100 μg/ml of ampicillin for 3 h at 30 C, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mm, and the bacterial culture was incubated for an additional 4 h at 30 C. Bacteria was harvested and lysed in a buffer containing 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl, and 1 mm EDTA. The bacterial lysate obtained after addition of Triton X-100 to a final concentration of 1% was sonicated and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 C. One milliliter of 50% of glutathione agarose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was added per liter of supernatant. After incubation for 1 h on ice, glutathione agarose beads were washed in PBS, pH 7.2 (PBS) containing 0.1% Triton X-100, until no more protein was present in the washing solution as monitored by a spectrophotometer. GST-RANKL fusion protein was eluted with an increasing concentration of 10 mm, 20 mm, and 30 mm of reduced glutathione in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The eluted protein was analyzed on SDS-PAGE to estimate purity. Fractions with GST-RANKL greater than 95% purity were collected and dialyzed with 2 liters of PBS overnight with one change. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). All experiments were carried out using uncleaved GST-RANKL fusion proteins based on previous studies that the GST tag does not impact on RANKL function (16).

Construction of stable cell line expressing luciferase reporter gene

To examine the effects of RANKL mutants on NF-κB activation, a RAW264.7 cell line stably expressing a NF-κB luciferase reporter gene was generated. The 3kB-Luc-SV40 reporter, which contains three Ig NF-κB sites from the interferon gene (30) upstream of the luciferase-coding region of the pGL2-basic plasmid was described previously (31). This construct was transfected into RAW264.7 using electroporation (280 V, 960 μF), the transfected cells were selected with 400 μg/ml of G418 (Life Technologies, Inc., Melbourne, Australia). The resulting stable cell line was used to investigate NF-κB activation by RANKL mutants. To study the activation of NF-κB by RANKL mutants, 5 × 104 P3K luciferase RAW264.7 cells were seeded onto each well of a 24-well plate overnight, treated with RANKL mutants, and incubated for different times. Firefly luciferase expression was measured using the Promega Luciferase Assay System according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro RANK-RANKL interaction by GST pull-down assay

GST-rRANKL fusion proteins (5 μg) were immobilized on 50 μl of 50% GSH-Sepharose agarose beads. The expression clone containing Flag-tagged RANK (aa 34–616, lacking an N-terminal signal sequence) has been previously reported (32). One sixth of cell lysates from a T75 flask-transfected COS-7 cells with Flag-RANK (aa 34–616) was added to agarose beads. The interaction mixture was incubated overnight at 4 C with gentle mixing on a rocking platform mixer. The RANK-RANKL interacting complexes were then collected by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 5 min at 4 C. The agarose beads-GST pull-down complexes were washed four times with cold NET lysis buffer (0.5% vol/vol Nonidet P-40, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl) to remove any unbound proteins. 2×SDS-PAGE loading buffer (50 μl) was then added to each tube, and protein complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blots were performed using the anti-Flag (M2) antibody.

Western blotting

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk powder in TBST [10 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20] and then probed with primary antibodies in the blocking solution. The membranes were washed three times with Tris-buffered saline. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were diluted 1:5000 in 1% (wt/vol) nonfat milk powder in TBST. The membranes were developed using the ECL+ system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Endotoxin assay

GST-RANKL fusion proteins were subjected to an endotoxin assay using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Chromogenic Test Kit Pyrochrome (Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA). Endpoint assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, endotoxin standards were made, measured, and determined in a 96-well plate according to the protocol. GST-RANKL fusion proteins (100 μl of each) were added to each well of a 96-well plate, after which 100 μl of Pyrochrome was then added to each sample and incubated at 37 C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped with 50% acetic acid. The color intensities of the wells were measured using a plate reader at 405 nm and recorded for analysis for the amount of endotoxin present according to the standard curve.

In vitro osteoclastogenesis assay

Mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells were used to test the inductive effect of rRANKL on osteoclastogenesis (16). In brief, RAW264.7 cells at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well in a 96-well plate were cultured in medium in the presence of GST-rRANKL fusion protein. All cultures were fed every 2–3 d by replacing used medium with respective fresh medium. After 6–7 d, all the cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and washed four times with PBS. The fixed cells were stained for TRAP using the Diagnostic Acid Phosphatase kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. TRAP-positive multinucleated cells with three or more nuclei were scored, and data were statistically analyzed by Student’s t test. In a parallel experiment, RAW264.7 cells were cultured on dentine slices in a 96-well plate and fixed. A bone resorption pit assay was then used to quantify the bone resorption.

Rat osteoclast isolation and bone resorption pit assay

Osteoclasts were isolated from the long bones of 1-d-old Wistar rats according to the procedure described by Burgess et al. (33). The separation of osteoclasts from nonosteoclastic cells was based on the different adhesion of the cells to the bone surface (34). To isolate the osteoclasts, the rat long bones free of surrounding soft tissues were split longitudinally and then minced in a homogenizer (Arthur H. Thomas Co., Philadelphia, PA) containing 2 ml acidified αMEM (72 μl concentrated HCl per 80 ml media) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Auckland, New Zealand) and antibiotics. Bones were homogenized gently, and the cell suspension was collected in a 15-ml conical tube. The remaining bone tissue was placed in a small petri dish with 1 ml media and chopped quickly with a scalpel blade. The resulting cell suspension was collected and added to the same conical tube. The bone tissue was homogenized again in 1 ml media, and the suspension was once again collected. The pooled cell suspension was then loaded onto the bone slices (170 μl/slice), which were previously equilibrated with culture medium in a 96-well plate (Cellstar, Greiner Labortechnik, Frickenhausen, Germany). After incubation at 37 C for 25 min in a humidified atmosphere to allow the attachment of the cells, the bone slices were rinsed vigorously in PBS and then in culture medium to remove the less adherent nonosteoclastic cells. Subsequently, the bone slices with enriched osteoclast population (100 osteoclasts per slice) were transferred to a 12-well plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) containing 2.5ml of culture medium per well (four slices per well). After incubation for 1 h, the cells were treated with rRANKL or rRANKL mutant and were continuously incubated under the above conditions. After incubation for 24 h, the cells on bone slices were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (in PBS) for 2 min and then washed twice with distilled water. The cells were then subjected to TRAP staining. The TRAP-positive cells with three or more nuclei were counted as osteoclasts under an inverted microscope (Olympus CK 40; Olympus Corp., Lake Success, NY). After counting, the cells were removed by gentle brushing, and the bone slices were stained for pits with 1% toluidine blue (in 1% disodium tetraborate) for 30 sec. The bone slices were examined under a reflection-light microscope (Olympus BH-2) to count the numbers of pits formed by the osteoclast. The bone-resorbing activity of osteoclasts was expressed as the number of pits produced per osteoclast.

Surface plasmon resonance

Binding of recombinant RANKL and RANKL mutants to RANK was measured using BIAcore 2000 system (BIAcore AB, Uppsala, Sweden) according to previous procedures (35). In brief, HEPES balanced salt running buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mm NaCl; 3 mm EDTA; and 0.005% P-20 surfactant) was used for immobilization and binding assays. Mouse RANK-Fc chimera (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) was immobilized on to the activated capture surface of a CM5 sensor chip using amine coupling. For general analysis of binding ability, RANK-Fc was immobilized to the flow cell at a very high surface density [measured in response units (RUs)] of 6000 RUs. Samples of GST, rRANKL1, and rRANKL5 were diluted in HEPES balanced salt running buffer for analysis and injected over the RANK-Fc flow cell at flow rate of 10 μl/min. Surface regeneration to baseline levels was achieved with a 1-min injection of 10 mm glycine, pH 1.5.

Generation of RANKL V277 mutant

To generate RANKL V277 mutant that mimics human mutation V277, plasmid pGEX-GST-rRANKL1 was amplified using two mutagenic primers: 5′-attTTTTaaAAGCTCCGGGCTGGTG-3′; and 5′-CCACCAGTTTATGGAATAAAAGTGG-3′. The amplified PCR products were treated with polynucleotide kinase and DpnI restriction enzyme, and then purified from agarose gel. The purified PCR products were self ligated and transformed. The plasmid was fully sequenced to confirm the identity. The expression and purification of RANKL-V277 as GST fusion proteins were carried out as described in a previous section.

Statistics and data presentation

The statistical analysis was performed using a paired or unpaired Student’s t test with significance taken at P < 0.05. At least three independent experiments were conducted. A set of data was then randomly selected from one of the experiments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (to M.H.Z. and J.X.) and the Health Research Council of New Zealand (to J. C.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online November 13, 2008

T.C., N.J.P., and C.W. contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations: aa, Amino acid(s); GST, glutathione S-transferase; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; OCL, osteoclast cell; RANK, receptor activator of NF-κB; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand; rRANKL, recombinant RANKL; TRAF, TNF receptor-associated factor; TRAP, tartrate-resistant of acid phosphatase.

References

- 1.Teitelbaum SL2000. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289:1504–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson DM, Maraskovsky E, Billingsley WL, Dougall WC, Tometsko ME, Roux ER, Teepe MC, DuBose RF, Cosman D, Galibert L1997. A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature 390:175–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, Hsu H, Sullivan J, Hawkins N, Davy E, Capparelli C, Eli A, Qian YX, Kaufman S, Sarosi I, Shalhoub V, Senaldi G, Guo J, Delaney J, Boyle WJ1998. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 93:165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong BR, Rho J, Arron J, Robinson E, Orlinick J, Chao M, Kalachikov S, Cayani E, Bartlett III FS, Frankel WN, Lee SY, Choi Y1997. TRANCE is a novel ligand of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family that activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase in T cells. J Biol Chem 272:25190–25194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Mochizuki S, Tomoyasu A, Yano K, Goto M, Murakami A, Tsuda E, Morinaga T, Higashio K, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Suda T1998. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:3597–3602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL, Timms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Van G, Itie A, Khoo W, Wakeham A, Dunstan CR, Lacey DL, Mak TW, Boyle WJ, Penninger JM1999. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature 397:315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong BR, Josien R, Choi Y1999. TRANCE is a TNF family member that regulates dendritic cell and osteoclast function. J Leukoc Biol 65:715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fata JE, Kong YY, Li J, Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Moorehead RA, Elliott R, Scully S, Voura EB, Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Khokha R, Penninger JM2000. The osteoclast differentiation factor osteoprotegerin-ligand is essential for mammary gland development. Cell 103:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones DH, Nakashima T, Sanchez OH, Kozieradzki I, Komarova SV, Sarosi I, Morony S, Rubin E, Sarao R, Hojilla CV, Komnenovic V, Kong YY, Schreiber M, Dixon SJ, Sims SM, Khokha R, Wada T, Penninger JM2006. Regulation of cancer cell migration and bone metastasis by RANKL. Nature 440:692–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang L, Xu J, Wood DJ, Zheng MH2000. Gene expression of osteoprotegerin ligand, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of NF-κB in giant cell tumor of bone: possible involvement in tumor cell-induced osteoclast-like cell formation. Am J Pathol 156:761–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu D, Xu JK, Figliomeni L, Huang L, Pavlos NJ, Rogers M, Tan A, Price P, Zheng MH2003. Expression of RANKL and OPG mRNA in periodontal disease: possible involvement in bone destruction. Int J Mol Med 11:17–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laird RK, Pavlos NJ, Xu J, Brankov B, White B, Fan Y, Papadimitriou JM, Wood DJ, Zheng MH2006. Bone allograft non-union is related to excessive osteoclastic bone resorption: a sheep model study. Histol Histopathol 21:1277–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roux S, Meignin V, Quillard J, Meduri G, Guiochon-Mantel A, Fermand JP, Milgrom E, Mariette X2002. RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB) and RANKL expression in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 117:86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamdy NA2008. Denosumab: RANKL inhibition in the management of bone loss. Drugs Today (Barc) 44:7–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Wu HF, Ang FS, Yip K, Woloszyn M, Zheng MH, Tan RX 27 November 2008. NF-κB modulators in osteolytic bone diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Xu J, Tan JW, Huang L, Gao XH, Laird R, Liu D, Wysocki S, Zheng MH2000. Cloning, sequencing, and functional characterization of the rat homologue of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand. J Bone Miner Res 15:2178–2186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam J, Nelson CA, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL, Fremont DH2001. Crystal structure of the TRANCE/RANKL cytokine reveals determinants of receptor- ligand specificity. J Clin Invest 108:971–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito S, Wakabayashi K, Ubukata O, Hayashi S, Okada F, Hata T2002. Crystal structure of the extracellular domain of mouse RANK ligand at 2.2-A resolution. J Biol Chem 277:6631–6636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobacchi C, Frattini A, Guerrini MM, Abinun M, Pangrazio A, Susani L, Bredius R, Mancini G, Cant A, Bishop N, Grabowski P, Del Fattore A, Messina C, Errigo G, Coxon FP, Scott DI, Teti A, Rogers MJ, Vezzoni P, Villa A, Helfrich MH2007. Osteoclast-poor human osteopetrosis due to mutations in the gene encoding RANKL. Nat Genet 39:960–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darnay BG, Haridas V, Ni J, Moore PA, Aggarwal BB1998. Characterization of the intracellular domain of receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK). Interaction with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors and activation of NF-κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem 273:20551–20555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galibert L, Tometsko ME, Anderson DM, Cosman D, Dougall WC1998. The involvement of multiple tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factors in the signaling mechanisms of receptor activator of NF-κB, a member of the TNFR superfamily. J Biol Chem 273:34120–34127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, Steer JH, Joyce DA, Yip KH, Zheng MH, Xu J2003. 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) inhibits osteoclastogenesis by suppressing RANKL-induced NF-κB activation. J Bone Miner Res 18:2159–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang YH, Heulsmann A, Tondravi MM, Mukherjee A, Abu-Amer Y2001. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) stimulates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis via coupling of TNF type 1 receptor and RANK signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 276:563–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Partidos CD, Steward MW2002. Mimotopes of viral antigens and biologically important molecules as candidate vaccines and potential immunotherapeutics. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 5:15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Partidos CD, Chirinos-Rojas CL, Steward MW1997. The potential of combinatorial peptide libraries for the identification of inhibitors of TNF-α mediated cytotoxicity in vitro. Immunol Lett 57:113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aoki K, Saito H, Itzstein C, Ishiguro M, Shibata T, Blanque R, Mian AH, Takahashi M, Suzuki Y, Yoshimatsu M, Yamaguchi A, Deprez P, Mollat P, Murali R, Ohya K, Horne WC, Baron R2006. A TNF receptor loop peptide mimic blocks RANK ligand-induced signaling, bone resorption, and bone loss. J Clin Invest 116:1525–1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda T, Kasai M, Suzuki J, Kuroyama H, Seki S, Utsuyama M, Hirokawa K2003. Multimerization of the RANKL isoforms and regulation of osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem 278:1525–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yip KH, Feng H, Pavlos NJ, Zheng MH, Xu J2006. p62 ubiquitin binding-associated domain mediated the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand-induced osteoclast formation: a new insight into the pathogenesis of Paget’s disease of bone. Am J Pathol 169:503–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ang ES, Zhang P, Steer JH, Tan JW, Yip K, Zheng MH, Joyce DA, Xu J2007. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase activity is required for efficient induction of osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption by receptor activator of nuclear factor κ B ligand (RANKL). J Cell Physiol 212:787–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akama KT, Albanese C, Pestell RG, Van Eldik LJ1998. Amyloid β-peptide stimulates nitric oxide production in astrocytes through an NFκB-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:5795–5800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steer JH, Kroeger KM, Abraham LJ, Joyce DA2000. Glucocorticoids suppress tumor necrosis factor-α expression by human monocytic THP-1 cells by suppressing transactivation through adjacent NF-κB and c-Jun-activating transcription factor-2 binding sites in the promoter. J Biol Chem 275:18432–18440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rea SL, Walsh JP, Ward L, Yip K, Ward BK, Kent GN, Steer JH, Xu J, Ratajczak T2006. A novel mutation (K378X) in the sequestosome 1 gene associated with increased NF-κB signaling and Paget’s disease of bone with a severe phenotype. J Bone Miner Res 21:1136–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgess TL, Qian Y, Kaufman S, Ring BD, Van G, Capparelli C, Kelley M, Hsu H, Boyle WJ, Dunstan CR, Hu S, Lacey DL1999. The ligand for osteoprotegerin (OPGL) directly activates mature osteoclasts. J Cell Biol 145:527–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hakeda Y, Kobayashi Y, Yamaguchi K, Yasuda H, Tsuda E, Higashio K, Miyata T, Kumegawa M1998. Osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor (OCIF) directly inhibits bone-resorbing activity of isolated mature osteoclasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 251:796–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Middleton-Hardie C, Zhu Q, Cundy H, Lin JM, Callon K, Tong PC, Xu J, Grey A, Cornish J, Naot D2006. Deletion of aspartate 182 in OPG causes juvenile Paget’s disease by impairing both protein secretion and binding to RANKL. J Bone Miner Res 21:438–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]