Abstract

The sodium-calcium exchanger isoform 1 (NCX1) is intimately involved in the regulation of calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis in many tissues including excitation-secretion coupling in pancreatic β-cells. Our group has previously found that intracellular long-chain acyl-coenzyme As (acyl CoAs) are potent regulators of the cardiac NCX1.1 splice variant. Despite this, little is known about the biophysical properties of β-cell NCX1 splice variants and the effects of intracellular modulators on their important physiological function in health and disease. Here, we show that the forward-mode activity of β-cell NCX1 splice variants is differentially modulated by acyl-CoAs and is dependent both upon the intrinsic biophysical properties of the particular NCX1 splice variant as well as the side chain length and degree of saturation of the acyl-CoA moiety. Notably, saturated long-chain acyl-CoAs increased both peak and total NCX1 activity, whereas polyunsaturated long-chain acyl-CoAs did not show this effect. Furthermore, we have identified the exon within the alternative splicing region that bestows sensitivity to acyl-CoAs. We conclude that the physiologically relevant forward-mode activity of NCX1 splice variants expressed in the pancreatic β-cell are sensitive to acyl-CoAs of different saturation and alterations in intracellular acyl-CoA levels may ultimately lead to defects in Ca2+-mediated exocytosis and insulin secretion.

THE SODIUM-CALCIUM EXCHANGERS (NCXs) are a family of membrane proteins that are involved in the regulation of calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis in a variety of tissues (1) and play an important role in excitation-secretion coupling in endocrine tissues such as pancreatic β-cells (2, 3). Despite the crucial function of NCX in β-cells, the biophysical properties and modulatory pathways are still poorly understood.

The NCX gene family consists of three separate gene products: NCX1 (4), NCX2 (5), and NCX3 (6). NCX1 is the best characterized family member and displays a ubiquitous expression pattern (7, 8). NCX1 is alternatively spliced to produce variants with differing tissue-specific expression patterns. For example, in the heart the major splice variant is NCX1.1 (8, 9), whereas the pancreatic β-cell is thought to express the NCX1.3 and 1.7 variants (10).

Under physiological conditions, NCX1 predominantly operates in forward-mode (FM) to extrude Ca2+ (3). However, under certain pathophysiological conditions, NCX1 activity may flip to reverse-mode (RM) with the resultant Ca2+ influx contributing to cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury (11, 12, 13). Understandably, considerable emphasis has been placed on the study of RM cardiac NCX1.1 activity. In this regard, there is significant interest in the intracellular regulators of RM NCX1 activity, such as anionic lipid moieties including phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) (14, 15, 16). Indeed, we have recently shown that RM activity of cardiac NCX1.1 is differentially regulated by saturated and unsaturated anionic lipid long-chain acyl-coenzyme As (CoAs), providing evidence for a link between Ca2+ homeostasis and fat metabolism (17). Interestingly, the accumulation of fatty acid intermediates, such as acyl-CoAs, is observed in type 2 diabetes and obesity (18, 19, 20). Taken together, these findings provide a rationale to test whether the physiologically-relevant FM activity of β-cell NCX1 splice variants is similarly sensitive to anionic lipid moieties such as acyl-CoAs, contributing to alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis, excitation-secretion coupling, and insulin secretion observed in these disease states.

Therefore, the aim of this study was 1) to compare the biophysical properties of β-cell NCX1 splice variants with the cardiac NCX1.1 variant and determine which exons in the alternatively spliced region are responsible for conferring observed differences and 2) to examine whether acyl-CoAs similarly modulate the FM activity of the β-cell/islet splice variants in a manner analogous to that observed for RM of the cardiac NCX1.1 splice variant.

RESULTS

Biophysical Characterization of Rat NCX1 Splice Variants

Previous measurements of the electrogenic activity of NCX1 have predominantly focused on the RM of the cardiac NCX1.1 splice variant. As a result, the biophysical properties of FM activity have been less well characterized. Therefore, we examined the activity of islet/β-cell (NCX1.3 and 1.7) and other splice variants of NCX1 and compared these findings with NCX1.1.

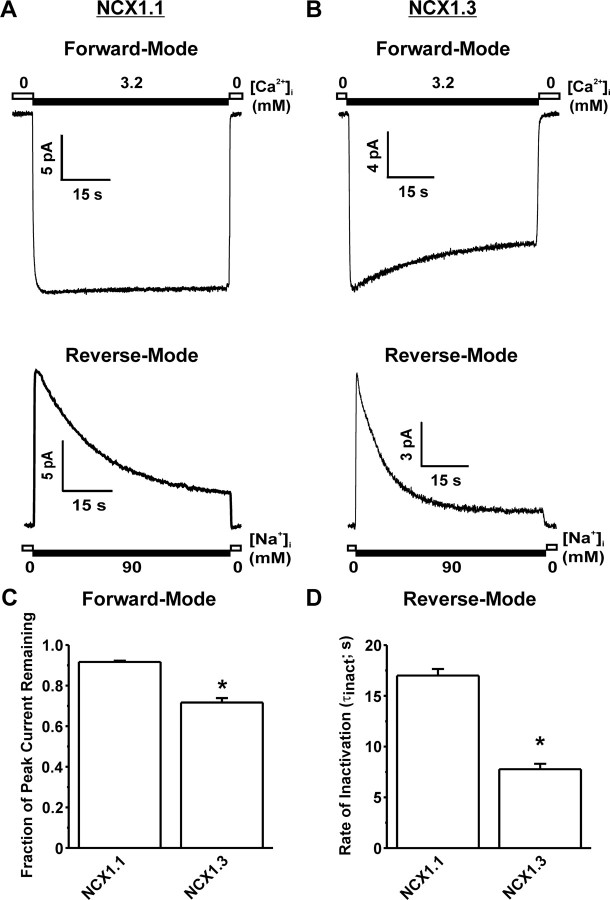

Figure 1 compares the activity of the rat NCX1.1 and 1.3 splice variants. As previously described (21, 22, 23), NCX1.1 generates a non-inactivating current in FM (steady state = 91.6 ± 0.6% that of peak; Fig. 1, B and C), but exhibits sodium-dependent (I1) inactivation (τinact = 17.0 ± 0.7 sec) during RM that stabilizes at a steady-state level that is 26.4 ± 2.0% that of peak current (Fig. 1A). Similarly, NCX1.3 RM activity undergoes I1 inactivation (Fig. 1B). However, NCX1.3 RM currents inactivate faster (τinact = 7.7 ± 0.5 sec; Fig. 1D) and to a greater extent than NCX1.1, stabilizing at a steady-state level that is 4.4 ± 0.8% of peak current (Fig. 1B). In contrast to NCX1.1, NCX1.3 FM activity displays a marked inactivation to a steady-state level that is 71.6 ± 2.2% that of peak current (Fig. 1, B and C).

Fig. 1.

Representative Macroscopic Rat NCX1 Currents in both FM and RM

A, The resulting rat cardiac NCX1.1 current exhibits a characteristic noninactivating FM activity whereas in RM, the current exhibits I1 inactivation. B, Representative macroscopic current recordings of rat β-cell NCX1.3 activity. In contrast to NCX1.1, the NCX1.3 exhibits a slowly developing inactivation when operating in FM. In RM, the NCX1.3 splice variant exhibits a similar I1 inactivation process. C, Grouped data indicating that NCX1.3 FM current inactivates to a significantly greater extent than NCX1.1. *, P < 0.05; n = 29 for NCX1.1 and 27 for NCX1.3. D, Grouped data showing that the rate of I1 inactivation for NCX1.3 is significantly faster than that for NCX1.1. *, P < 0.05; n = 57 for NCX1.1 and 22 for NCX1.3. s, Seconds.

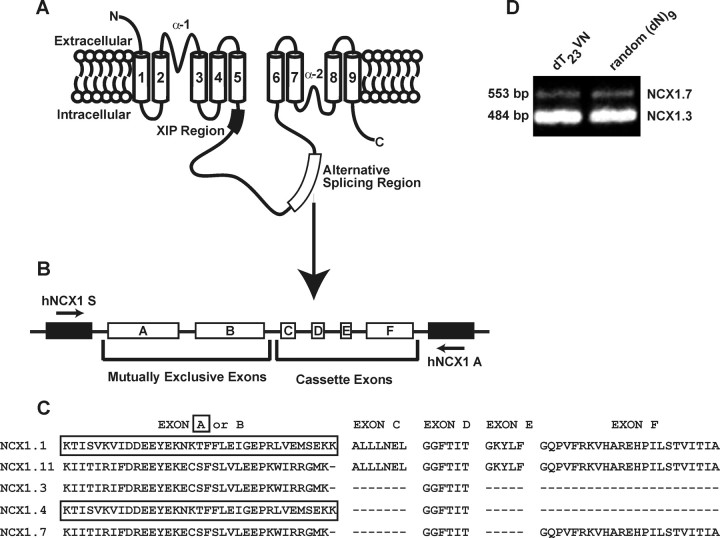

Cloning and Functional Expression of Human Islet NCX1 Splice Variants

The novel observation that FM NCX1.3 currents inactivate may represent a major contribution to the understanding of NCX1 transport. To examine whether this phenomenon is conserved across species, human islet NCX1 splice variants were cloned. RT-PCR using primers that flanked the alternative splicing region of NCX1 revealed that NCX1.3 and 1.7 (Fig. 2) are represented in total RNA obtained from normal adult human islets. These findings are consistent with previous reports from human insulinoma cells and rodent β-cells (10, 24).

Fig. 2.

The Proposed Membrane Topology of the Na+/Ca2+ Exchanger

A, The exchanger protein consists of nine transmembrane domains with a large intracellular loop between domains 5 and 6. Immediately proximal to domain 5 is the XIP region that is involved in the inactivation process. The alternative splicing region is also denoted (27 ). B, Alternative splicing region cassettes with arrows denoting the approximate location of the primers hNCX1 S and hNCX1 A. C, Exon composition of cardiac NCX1.1 (exons ACDEF); 2) NCX1.11 (exons BCDEF); 3) islet NCX1.3 (exons BD); and 4) NCX1.7 (exons BDF) splice variants and NCX1.4 (exons AD). D, NCX1 splice variant-specific human islet amplification reveals expression of NCX1.3 and 1.7. DN, Dominant-negative. dT23VN, OligodT prime (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA).

As observed with the rat splice variant, human FM NCX1.1 currents fail to inactivate (steady state = 93.7 ± 0.6% that of peak; Fig. 3, A and D), whereas the islet exchangers, NCX1.3 (steady state = 75.0 ± 1.7% of peak; Fig. 3, B and D) and NCX1.7 (steady state = 72.7 ± 1.7% of peak; Fig. 3, C and D), exhibit significant FM inactivation. Similarly, human RM NCX1.1 currents exhibit I1 inactivation (τinact = 13.1 ± 0.6 s) that stabilizes at a steady-state level that is 21.8 ± 1.5% that of the peak current (Fig. 3, A and E). Likewise, NCX1.3 (τinact = 7.5 ± 0.4 sec; Fig. 3, B and E) and NCX1.7 (τinact = 7.2 ± 0.7 sec; Fig. 3, C and E) exhibit a faster and more complete RM inactivation.

Fig. 3.

Representative Macroscopic Human NCX1 Currents in both FM and RM

A, FM cardiac NCX1.1 activity exhibits a characteristic noninactivating FM activity whereas in RM, the current undergoes I1 inactivation. Representative macroscopic current recordings of the human islet NCX1.3 (B) and NCX1.7 (C) activities. In contrast to NCX1.1, NCX1.3 and 1.7 currents exhibit a slowly developing inactivation when operating in FM. In RM, the NCX1.3 and 1.7 splice variants exhibit a similar I1 inactivation process. D, Grouped data indicating that human islet NCX1 FM currents inactivate to a significantly greater extent than NCX1.1. *, P < 0.05; n = 36–39 per group. E, Grouped data showing that the rate of I1 inactivation for human islet NCX1 splice variants are significantly faster than that for NCX1.1. *, P < 0.05; n = 17–63 per group. s, Seconds.

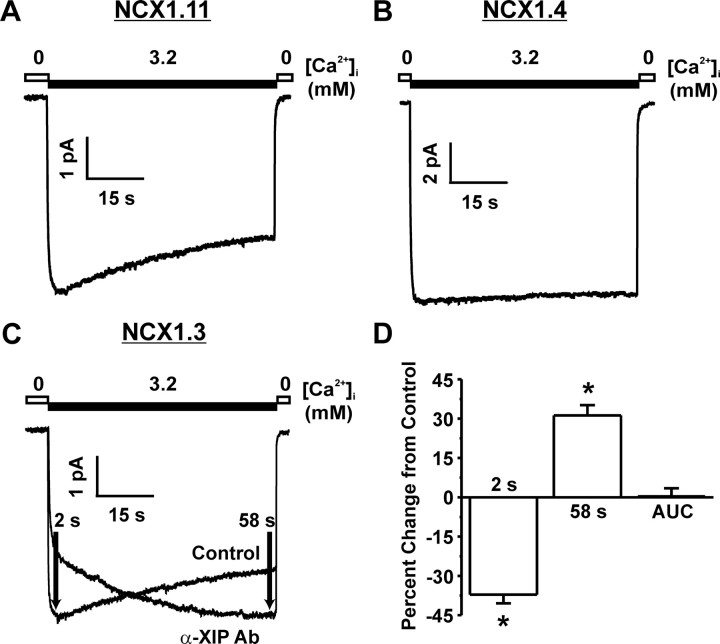

Regions of the NCX1 Protein Involved in FM Inactivation

As NCX1 splice variants differ only in the exon composition of the alternative splicing region, the exon composition in this region likely contributes to FM inactivation. Analysis of this region in NCX1.1 (ACDEF) vs. NCX1.3 (BD) and NCX1.7 (BDF) revealed that the mutually exclusive A and B exons are candidates for the observed biophysical differences between splice variants (Fig. 2). As only NCX1.1 contains exon A and displays no FM inactivation, this exon was substituted for B, generating human NCX1.11 (Fig. 2C). NCX1.11 displays FM inactivation similar to that observed for NCX1.3 and NCX1.7 (steady state = 70.8 ± 1.5% that of peak; n = 33; Fig. 4A). Similarly, replacing exon B with exon A in rat NCX1.3 generates NCX1.4 (Fig. 2C) and abolishes FM inactivation (steady state = 93.9 ± 0.5% that of peak; n = 36; Fig. 4B). Therefore, it can be concluded that exon B is involved in regulating the observed FM inactivation.

Fig. 4.

Regions of the NCX1 Protein Involved in the FM Inactivation Process

A and B, The roles of exons A and B. Substitution of exon A in NCX1.1 with that of exon B (generating NCX1.11) confers FM inactivation to NCX1.1 (A). Similarly, substitution of exon B in NCX1.3 with that of exon A (generating NCX1.4) eliminates FM inactivation from NCX1.3 (B). C and D, The role of the XIP region in the FM inactivation process. Representative FM rat NCX1.3 activity showing that application of the anti-XIP antibody leads to a slowing in the time course of activation (2-sec time point), abolishes the FM inactivation process (58-sec time point), but does not change the total amount of activity [area under the curve (AUC)] (*, P < 0.05; n = 8). The anti-XIP antibody was used at 1:100. Ab, Antibody; s, seconds.

Previous experiments exploring RM inactivation have indicated that interactions with the intracellular exchanger inhibitor peptide (XIP) region are involved in the I1 inactivation process (1, 25). Mutations in this region can enhance, slow, or even eliminate RM inactivation in the cardiac NCX1.1 splice variant (26). Furthermore, we have previously shown that an antibody targeting the XIP region accelerates RM inactivation and almost completely abolishes steady-state current (17). Thus, we speculated that FM inactivation might also involve the XIP region. Accordingly, the effects of an anti-XIP antibody on FM inactivation were tested on rat NCX1.3. In contrast to that previously observed for RM, the anti-XIP antibody significantly delayed the onset of peak current during FM (37.1 ± 3.3% decrease in current 2 sec after activation compared with control; Fig. 4, C and D) and prevented FM inactivation (31.2 ± 3.9% increase in treated current 58 sec after activation compared with control; Fig. 4, C and D). Together, these effects yielded no significant change in the total amount of exchanger activity (0.3 ± 3.1% increase in area under the curve compared with control; Fig. 4, C and D).

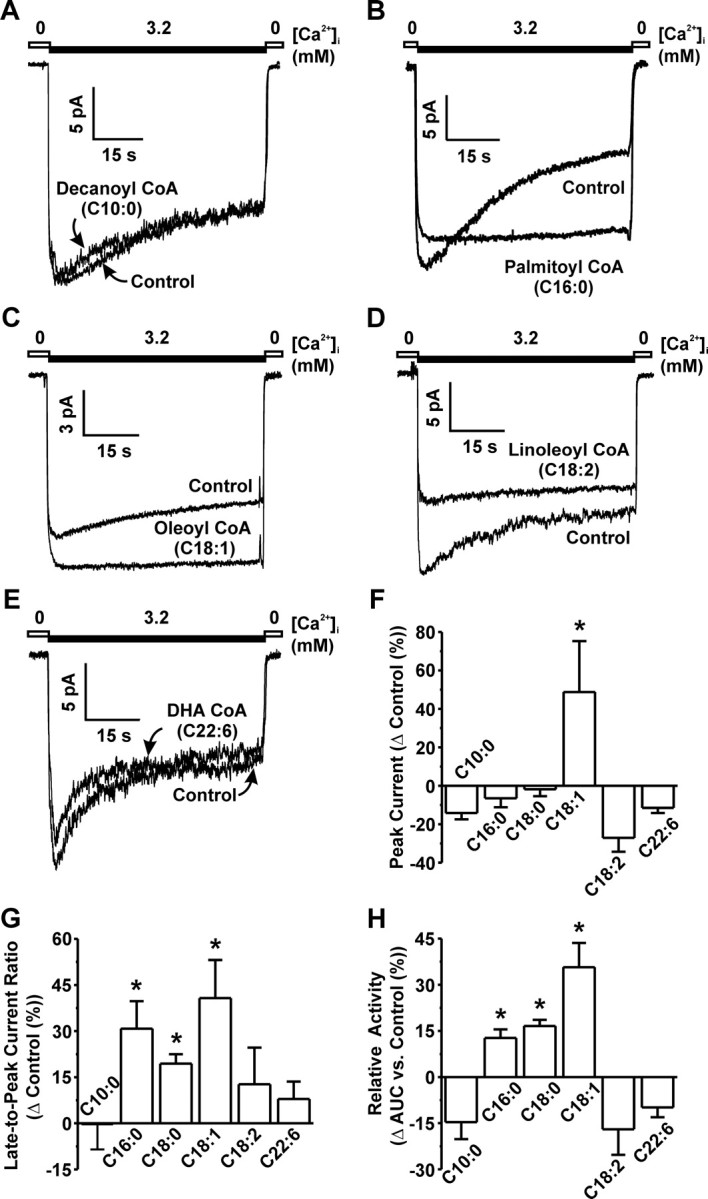

The Effects of Acyl-CoA Chain Length and Degree of Saturation on NCX1.3 FM Activity

We have previously shown that acyl-CoAs increase RM rat cardiac NCX1.1 activity in a side chain length- and saturation-dependent manner and that acyl-CoAs exert their effects by interfering with RM inactivation (17). Thus, we hypothesized that a similar relationship may exist between acyl-CoAs and FM NCX1.3 exchange activity.

Application of the medium-chain decanoyl-CoA (C10:0) to membrane patches expressing rat NCX1.3 resulted in no significant effect on FM currents (Fig. 5, A and F–H). Increasing the chain length to 16 carbons (palmitoyl-CoA, C16:0) resulted in a 30.8 ± 8.9% reduction in FM inactivation (Fig. 5, B and G) and a corresponding 12.7 ± 2.8% increase in total activity (Fig. 5H). A further increase in chain length by 2 carbons (stearoyl-CoA, C18:0) resulted in a 19.4 ± 3.1% reduction in inactivation (Fig. 5G). In the absence of a significant change in peak current (Fig. 5F), this resulted in a 16.6 ± 2.0% increase in total activity (Fig. 5H). The introduction of one double bond (oleoyl-CoA, C18:1) yielded a significant increase in peak current (Fig. 5, C and F) and maintained the effect on inactivation (Fig. 5G), resulting in a 35.7 ± 7.9% increase in total activity (Fig. 5H). Interestingly, the addition of a second double bond (linoleoyl-CoA, C18:2) eliminated the effect of the acyl-CoA on both the peak current and inactivation (Fig. 5, D and F–H). Finally, the effect of the polyunsaturated ω-3 fish oil ester, docosahexaenoyl-CoA (C22:6) CoA was tested and had no significant effects on each of the parameters analyzed (Fig. 5, E–H).

Fig. 5.

Activation of FM Rat NCX1.3 Activity by Acyl-CoAs Exhibits Saturation and Chain Length Dependence

A–E, Representative macroscopic NCX1.3 current recordings showing that short-chain (decanoyl-CoA, C10:0) and polyunsaturated acyl-CoAs (linoleoyl-CoA, C18:2; and DHA-CoA, C22:6) do not significantly modulate FM activity, unlike palmitoyl-CoA (C16:0), oleoyl-CoA (C18:1) and stearoyl-CoA (C18:0) (data not shown). F, Grouped data showing the maximum effect of each acyl-CoA on the peak current obtained during activation. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; n = 4–14 per group. G, Grouped data showing the maximum effect of each acyl-CoA on the inactivation process as measured by the late-to-peak current ratio. *, P < 0.05 vs. respective control; n = 4–14 per group. H, Grouped data indicating that saturated and monounsaturated acyl-CoAs significantly increase total FM activity, whereas polyunsaturated and medium-chain acyl-CoAs do not. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; n = 4–13 per group. Acyl-CoA concentrations were 1 μm. AUC, Area under the curve; s, seconds.

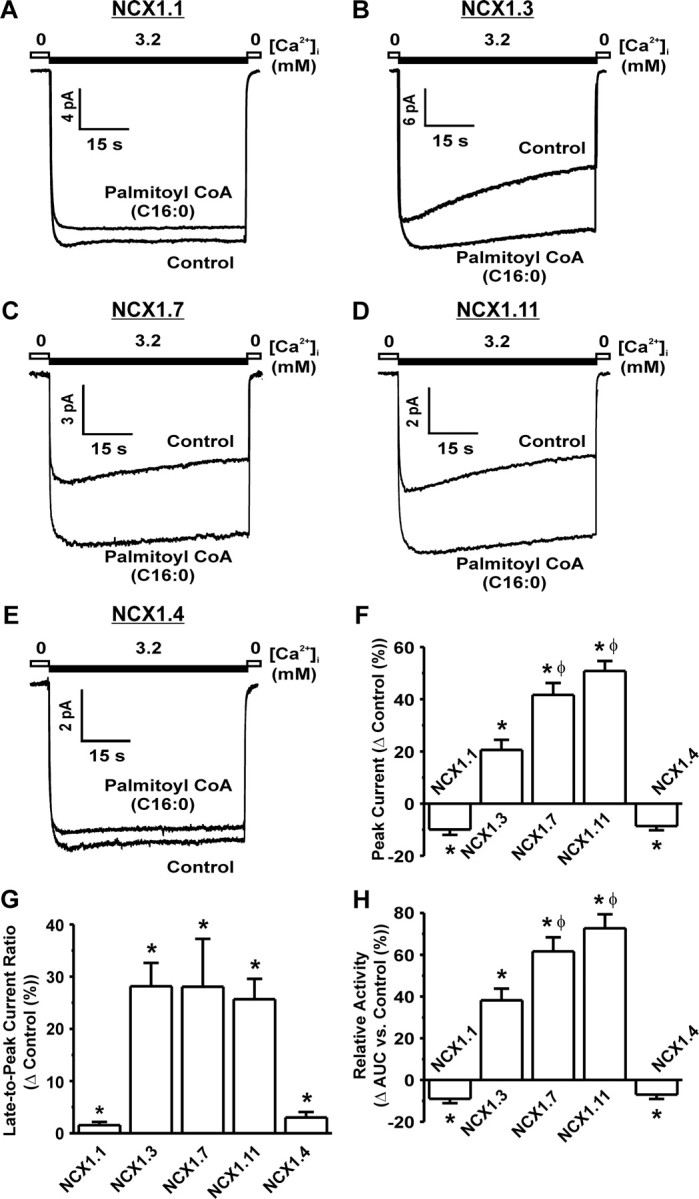

The Effects of Palmitoyl-CoA on Human Islet NCX1 FM Activity

To ascertain whether the stimulatory effects of long-chain acyl-CoAs on FM activity are conserved across species, the effects of palmitoyl CoA on FM human NCX1 currents were examined. Application of 1 μm palmitoyl-CoA (C16:0) to NCX1.1 (Fig. 6A) resulted in a 9.9 ± 2.1% decrease in peak current (Fig. 6F), a 1.5 ± 0.6% reduction in inactivation (Fig. 6G), and a 9.0 ± 2.1% reduction in the total amount of NCX1.1 activity (Fig. 6H). In contrast, application of palmitoyl-CoA to NCX1.3 (Fig. 6B) and 1.7 (Fig. 6C) resulted in an increase in the peak current (20.6 ± 3.9% for NCX1.3 and 38.6 ± 4.1% for NCX1.7; Fig. 6F), a reduction in the amount of inactivation (28.2 ± 4.5% for NCX1.3 and 30.3 ± 11.5% for NCX1.7; Fig. 6G), and a corresponding increase in the total amount of exchanger activity (38.2 ± 5.6% for NCX1.3 and 60.1 ± 7.7% for NCX1.7; Fig. 6H). Moreover, NCX1.7 is more sensitive to palmitoyl-CoA than NCX1.3 (Fig. 6, G and H), suggesting that exon F may confer additional acyl-CoA sensitivity.

Fig. 6.

A Saturated Acyl-CoA Activates FM Activity of Human Islet NCX1 Splice Variants

Representative NCX1 current recordings showing that palmitoyl-CoA (C16:0) modulates NCX1.1 (A) and 1.4 FM activity (E) in a different manner than that of NCX1.3 (B), 1.7 (C), and 1.11 (D). F, Grouped data showing that palmitoyl-CoA significantly increases the peak current obtained during activation for splice variants that exhibit FM inactivation, whereas palmitoyl-CoA significantly decreases peak current for splice variants that did not. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; n = 8–10 per group. G, Grouped data showing that palmitoyl-CoA significantly reduces the amount of FM inactivation regardless of the intrinsic amount of inactivation inherent to the splice variant as measured by the late-to-peak current ratio. *, P < 0.05 vs. control. H, Grouped data indicating that palmitoyl-CoA significantly increases total islet NCX1 FM activity for those splice variants that exhibit FM inactivation and significantly decreases the total activity for those that do not. *, P < 0.05 vs. control. φ, P < 0.05 NCX1.7 and 1.11 vs. NCX1.3. Palmitoyl-CoA concentration was 1 μm. s, Seconds.

To further explore the mechanism of FM inactivation and its modulation by acyl-CoAs, we examined the effects of palmitoyl-CoA on NCX1.11 (Fig. 6D) and NCX1.4 (Fig. 6E). As expected, NCX1.11 exhibited a 50.8 ± 3.8% increase in peak current (Fig. 6F), a 25.7 ± 3.9% reduction in inactivation (Fig. 6G), and 72.7 ± 6.7% increase in total activity (Fig. 6H). Furthermore, like NCX1.7, these were significantly greater than that of NCX1.3, again suggesting a role for exon F in acyl-CoA sensitivity (Fig. 6, G and H). In contrast, NCX1.4 exhibited an 8.6 ± 1.6% decrease in peak current (Fig. 6F), a 3.0 ± 1.1% reduction in inactivation (Fig. 6G), and a 7.0 ± 2.0% reduction in the total amount of activity (Fig. 6H).

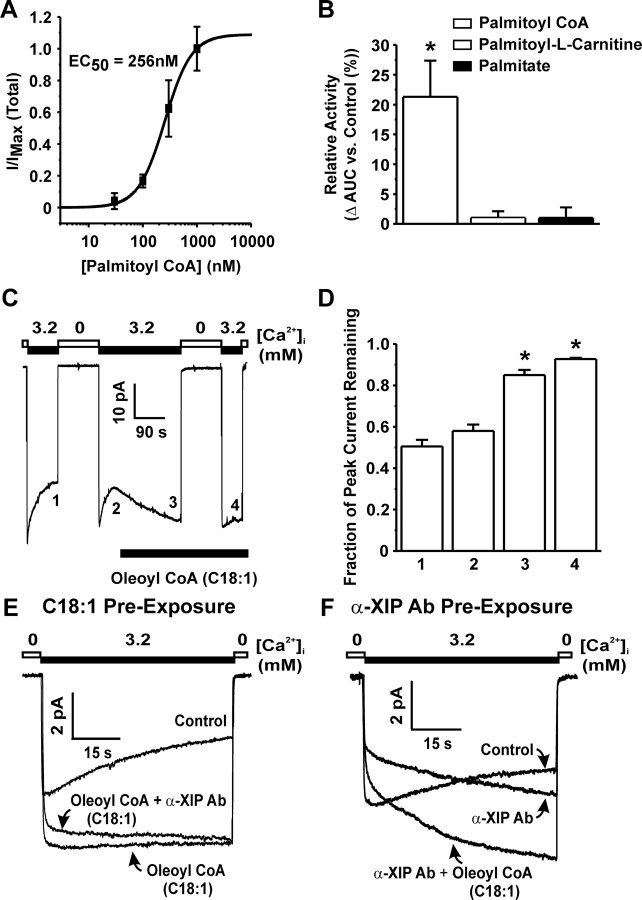

In addition, it was found that the effect of palmitoyl-CoA on NCX1.3 FM activity is concentration dependent (EC50 = 255.5 ± 15.0 nm) and reaches a maximum at 1 μm (Fig. 7A). Lastly, the observed increase in FM activity brought on by exposure of palmitoyl-CoA (300 nm; 21.3 ± 6.1% increase; Fig. 7B) is due to the presence of the CoA moiety. Replacement of CoA with a carnitine group (palmitoyl-l-carnitine) failed to significantly increase NCX1.3 total activity (1.0 ± 1.0% increase; Fig. 7B). Similarly, removal of the CoA moiety altogether (palmitate) also failed to significantly increase total activity (1.0 ± 1.8% increase; Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

The Effects of Different Acyl Derivatives and Mechanistic Insights into Acyl-CoA Regulation of FM Inactivation

A, Concentration-response curve illustrating the effects of palmitoyl-CoA on FM human NCX1.3 (EC50 = 255.5 ± 15.0 nm; n = 3–6 per concentration). B, The effects of different acyl derivatives (300 nm) on human NCX1.3 FM activity. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; n = 6 per group. C, Representative FM rat NCX1.3 current recording indicating that the inactivation process is reversible in the presence of oleoyl-CoA (C18:1). D, Grouped data were obtained for peak currents normalized to the peak current obtained during the control activation. Each numbered bar corresponds to the respective number on the representative trace in panel A. *, P < 0.05 vs. 1 in panel A; n = 3–4 per group. E, Pre-exposure of membrane patches with oleoyl-CoA does not prevent the effects of the anti-XIP antibody on FM activity as evidence by the delayed time-to-peak. F, Similarly, pre-exposure of membrane patches with the anti-XIP antibody does not prevent the effects of oleoyl-CoA on FM activity. Oleolyl-CoA concentration was 1 μm and the anti-XIP antibody was used at 1:100. Ab, Antibody; s, seconds.

The Mechanism and Site of Acyl-CoA Interaction with NCX1

To explore whether the acyl-CoA effect requires a nonexchanging state, we applied acyl-CoAs during the activated state. Application of 1 μm oleoyl-CoA (C18:1) to rat NCX1.3 currents that have partially inactivated resulted in a restoration of activity and a reversal of the inactivation process (Fig. 7C). The level of activity reached at steady state (85 ± 2.5% of control peak current) was not different from the initial peak current recorded before inactivation nor was it different from the peak current obtained after a brief 2-min inactivation of current in the presence of oleoyl-CoA (Fig. 7, C and D; compare points 3 and 4). Similar effects were observed with saturated stearoyl-CoA (data not shown).

We have previously shown that acyl-CoAs alter RM NCX1.1 activity via the XIP region as pre-exposure of membrane patches with oleoyl-CoA prevents the inhibitory effects of the anti-XIP antibody (17). To test whether acyl-CoAs may alter this antibody-mediated effect, we pretreated membrane patches expressing rat NCX1.3 with 1 μm oleoyl-CoA and found that this acyl-CoA did not prevent the effects of the anti-XIP antibody on the inactivation process (Fig. 7E). Similarly, pre-exposing NCX1.3 to the anti-XIP antibody did not prevent the effects of oleoyl-CoA (Fig. 7F). Thus, in contrast to that observed for NCX1.1 RM activity, acyl-CoAs affect FM activity at a site that is distinct from the XIP region.

Increased NCX1 Activity Inhibits Calcium-Dependent Exocytosis

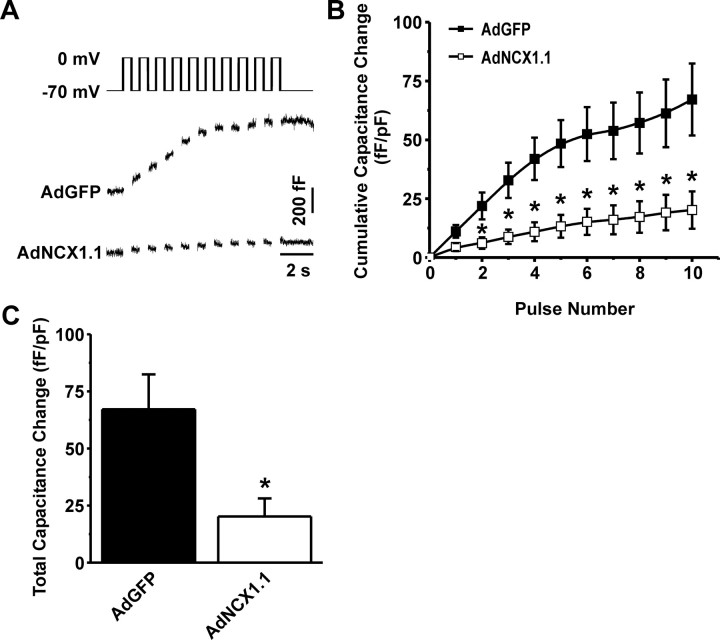

To examine the cellular consequences of increased FM NCX1 activity, we measured whole-cell capacitance changes elicited by a train of depolarizing pulses in primary mouse β-cells overexpressing either green fluorescent protein (GFP) or the rat NCX1.1 splice variant (Fig. 8). Overexpression of NCX1.1 blunted the capacitance response (Fig. 8, A and B). This resulted in an overall decrease in the total capacitance change from 67.1 ± 15.3 (n = 5) to 20.2 ± 7.9 fFarad/pFarad (n = 8; Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

The Effects of Increased NCX1 Activity on Calcium-Dependent Exocytosis in Mouse β-Cells

A, Representative capacitance measurements from β-cells either expressing GFP (AdGFP, control) or NCX1.1 (AdNCX1.1), in response to a depolarizing train of membrane potential pulses. B, Grouped data of cumulative changes in capacitance in the AdGFP and AdNCX1.1 groups at individual pulse numbers. C, Grouped total capacitance changes as determined by summation of the individual pulse capacitance measurements. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; n = 5–8 experiments for each group. fF, femtoFarads; pF, picoFarads; s, seconds.

DISCUSSION

Mechanistic Insights

Our data represent the first direct electrophysiological characterization of β-cell/islet NCX1.3 and 1.7 currents and their comparison with the cardiac NCX1.1 splice variant. Interestingly, we observed that islet splice variants exhibited FM inactivation and a faster and more complete RM inactivation. However, the molecular mechanisms that mediate these alterations in the inactivation processes observed in NCX1.3 and 1.7 are not currently known. NCX1 splice variants share substantial sequence identity, and regulatory regions are conserved (27). The exon makeup within the alternative splicing region represents the only differences between NCX1 splice variants, determining their unique properties. Because the only sequence variations among NCX1.1, 1.3, and 1.7 reside in this region, the presence or absence of FM inactivation can be attributed to the differences within this region. To investigate this directly, we examined NCX1.11 (BCDEF) and NCX1.4 (AD). In contrast to NCX1.1 (ACDEF), NCX1.11 FM currents exhibited significant acyl-CoA-sensitive inactivation (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, unlike NCX1.3 (BD), FM NCX1.4 (AD) currents exhibited no inactivation and markedly reduced sensitivity to acyl-CoAs (Fig. 6E). Together, these data strongly indicate that exon B is responsible for bestowing FM inactivation and acyl-CoA sensitivity to NCX1.

Precisely how differences between the amino acid sequence of exons A and B confer FM inactivation and acyl CoA sensitivity remains to be determined. However, our previous results on the actions of acyl-CoAs on the KATP channel indicate the importance of positively charged residues (28, 29). It is possible that the presence of several arginine and lysine residues in exon B that are not present in exon A (Fig. 2) may confer acyl-CoA sensitivity and FM inactivation to NCX1.3, 1.7, and 1.11 (Fig. 6). Additional positively charged residues in exon F (Fig. 2) may also contribute additional acyl-CoA sensitivity to NCX1.7 and 1.11.

The observed differences in FM inactivation between NCX1 splice variants must lie either directly within the alternative splicing region itself or in the manner by which this region interacts with specific areas of the folded protein that control the inactivation process. For example, the XIP region is known to modulate RM inactivation (15, 26). The presence of exon B in NCX1.3 and 1.7 may facilitate a XIP-mediated inactivation process leading to the observed FM inactivation and accelerated RM inactivation (Figs. 1 and 3). Surprisingly, application of an anti-XIP antibody did not abolish FM activity. Instead, the antibody caused the exchanger to reach the maximal peak current more slowly and prevented FM inactivation (Fig. 4, C and D). These results suggest that the XIP region is involved in the transition from the non-exchanging state to the active state and that the antibody slows the rate at which this state change occurs. Furthermore, the XIP region seems to be intimately involved in the switch from the active state to the inactive state as evidenced by the ability of the antibody to prevent FM inactivation from occurring.

We have previously suggested that acyl-CoAs interact with the XIP region in NCX1.1 to reduce RM inactivation (17). Therefore, an interaction between acyl-CoAs and the XIP region may provide a plausible explanation for the stimulatory effects of acyl-CoAs on FM NCX1.3 and 1.7 activities by relief of a XIP-mediated inactivation process. In contrast to this notion, our results suggest that acyl-CoAs may not exert their effects via the XIP region directly because pretreatment with oleoyl-CoA could not abolish the effect of the anti-XIP antibody on FM NCX1.3 currents and vice versa (Fig. 7, E and F). Based upon the marked difference in the response of exon A-containing splice variants (NCX1.1 and 1.4) and exon B-containing splice variants (NCX1.3, 1.7, and 1.11) to palmitoyl-CoA, it is tempting to speculate that exon B may be the site of acyl-CoA modulation of FM activity.

In this study we observed a marked side-chain length and saturation dependence in the effects of acyl-CoAs on FM NCX1.3 activity, with longer chain saturated and monounsaturated acyl-CoAs having the greatest effect (Fig. 5). These findings agree with our previous results on RM activity for NCX1.1 (17). The similar acyl-CoA side-chain and saturation dependence between FM and RM suggests that the underlying mechanisms involved in the relief of inactivation may be related in both modes. Our present data suggest that whereas the XIP region is important for FM inactivation, the ability of acyl-CoAs to modulate this process is not directly associated with this region. Rather, our data suggest interplay between the XIP and alternative splicing regions (especially exons B and F) is involved in mediating the observed acyl-CoA effects. Furthermore, our data show that this effect is dependent upon the presence of the CoA moiety, because other free fatty acids and acyl intermediates fail to effect FM NCX1.3 activity (Fig. 7B).

The Cellular Consequences of Increased NCX1 FM Activity

NCX1 is a major Ca2+ extrusion pathway regulating the secretory response. Consequently, the identification of potential endogenous modulators of NCX1 activity is of critical importance in both health and disease. For example, the pancreatic β-cell expresses a number of intracellular and plasma membrane-bound proteins (including NCX1) that combine to reduce intracellular free Ca2+ (30, 31). Indeed, the importance of β-cell NCX1 activity is highlighted in studies where NCX1 expression is either increased (32) or decreased (33) and β-cell NCX1 activity may account for up to 70% of Ca2+ extrusion (33). Recently, however, this value has been estimated at 21–30% when intracellular Ca2+ is elevated (31). This apparent discrepancy may result from species-specific differences in β-cell function. Indeed, NCX1 pancreatic activity varies substantially between rat (33) and mouse (34), and therefore interspecies variability in β-cell physiology may explain this difference.

Whereas it would be advantageous to test the direct effects of acyl-CoAs on NCX1 current in native β-cells, the inherently small current in native cells precluded us from attempting these studies. Furthermore, acyl-CoAs have a number of cellular effects in addition to regulating NCX1 activity (35). Thus, experimental manipulation of intracellular acyl-CoA levels and measurement of exocytosis would likely not reveal a definitive direct link between acyl-CoAs and NCX1 activity. Therefore, we chose to directly examine the cellular consequences of increased FM NCX1 activity, by overexpression of the cardiac NCX1.1 splice variant in mouse pancreatic β-cells. By artificially increasing the amount of FM NCX1 activity in β-cells, we observed a significant reduction in the amount of granule exocytosis (and presumably insulin secretion) in response to a train of depolarizing stimuli (Fig. 8). These results further support the concept that increases in NCX1 FM activity, by any mechanism, will lead to reductions in β-cell excitation-secretion coupling and exocytosis. Furthermore, saturated long-chain acyl-CoAs increase the physiologically relevant peak NCX1 activity that plays a key role in mediating the Ca2+ secretory signal. Fatty acid metabolism within pancreatic β-cells is involved in the regulation of the appropriate nutrient-stimulated insulin-secretory response, and acyl-CoAs are clearly an important intracellular signaling molecule in this process (20, 35, 36).

Summary

Findings from this study now demonstrate, for the first time, that acyl-CoAs regulate β-cell/islet FM NCX1 splice variant activity in an exon-dependent manner and that these changes may have implications for excitation-secretion coupling in health and disease. β-Cell NCX1 is thought to operate predominantly in FM as a Ca2+ extrusion mechanism (32), and elevation of intracellular acyl-CoA levels is known to occur in obesity and diabetes. We therefore speculate that the observed acyl-CoA-mediated increases in FM NCX1 activity, via enhanced peak and steady-state currents, may contribute to the documented first-phase insulin-secretory defect in type 2 diabetes. Additionally, the marked differences in the stimulatory effects between acyl-CoAs of different saturation and chain length may have dietary implications for our current understanding of β-cell Ca2+ signaling in the development of impaired insulin secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular Biology

The rat NCX1.1 adenovirus was provided by Dr. J.Y. Cheung (37), and the rat NCX1.3 and 1.4 cDNAs were obtained from Dr. J. Lytton (38). Primers used to determine which NCX1 splice variants are expressed in human islets were hNCX1 S 5′-gtgagtgagagcattggc-3′ and hNCX1 A 5′-ctctccagctgttagtcc-3′ and flanked the region of alternative splicing. Full-length human NCX1.3 and 1.7 cDNAs were separately generated from two overlapping cDNAs obtained via RT-PCR. The cDNAs were sequenced and compared with the corresponding GenBank sequences AF108389 (NCX1.3) and AF108388 (NCX1.7). For NCX1.1, RT-PCR was performed using total human atrial RNA to generate human NCX1.1. For NCX1.11, two overlapping PCR products were amplified and fused together via PCR. The upstream PCR product was amplified from NCX1.3 using an antisense primer that contained partial sequence for exon C, and the downstream PCR product was amplified from NCX1.1 using a sense primer that contained partial sequence for exon B.

Cell Culture and Transfection

tsA201 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 25 mm glucose, 2 mm l-glutamine, 10% FCS, and 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 C with 5% CO2. tsA201 cells were cotransfected with an NCX1 cDNA clone and a GFP plasmid using the calcium phosphate precipitation technique. Expression of rat NCX1.1 in tsA201 cells was obtained via adenoviral delivery of NCX1.1. In this adenoviral construct, both NCX1.1 and GFP were driven under separate cytomegalovirus promoters (37). tsA201 cells were exposed to approximately 30 pfu/cell AdNCX1.1 for 2–4 h. Experiments were performed 24–72 h after transfection/infection.

Electrophysiology

The excised inside-out patch clamp technique was used to measure inward (FM) and outward (RM) NCX1, and macroscopic NCX1 currents were evoked at room temperature (22 ± 1 C) as previously described (17). Briefly, FM currents were elicited by applying 3.2 mm Ca2+ to the cytosolic surface of the patch, whereas RM currents were measured by applying 90 mm Na+. The membrane patch was held at 0 mV, and NCX1 currents were measured and analyzed using the Axopatch 200B amplifier and Clampex 8.0 or 9.2 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA).

NCX1.1 Overexpression in β-Cells

Primary β-cells from BALB/c mouse islets were isolated and cultured as described previously (39). β-Cells were infected with the rat NCX1.1 adenovirus (AdNCX1.1) or an adenoviral vector expressing GFP (AdGFP). Membrane capacitance changes were measured in the whole-cell configuration of an EPC10 amplifier and Patchmaster software (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Pfalz, Germany). Exocytosis was elicited with a train of ten 500-msec depolarizations (at 1Hz) from −70 to 0 mV. Fire-polished patch pipettes had resistances of 3–6 MΩ and were filled with (in mm concentration): 125 Cs-glutamate, 20 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 3 Mg-ATP, 0.1 cAMP, 0.05 EGTA (pH 7.2) with CsOH. β-Cells were identified based on cell size (>5 pFarads) and the lack of voltage-activated Na+ current from physiological holding potentials (−70 mV) (40). Data were analyzed with Fitmaster software (HEKA Elektronik). Total exocytosis was taken as the sum of the capacitance increases during the depolarizing pulses, whereas the total endocytosis was taken as the sum of the capacitance decreases between depolarizing pulses (i.e. the interpulse interval). Capacitance changes were normalized to the initial cell size (as fFarads/pFarad).

Experimental Compounds

The anti-XIP antibody (Alpha Diagnostic Intl, San Antonio, TX) was reconstituted in PBS at 1 mg/ml and diluted 1:100 in intracellular solution before use. All acyl-CoAs were dissolved in double-distilled H2O as 1 mm stocks and sonicated for 5–10 min before their addition to the patching solutions yielding an effective concentration of 1 μm, well below the critical micellar concentration for these acyl-CoAs (41, 42). Patch solutions themselves were also sonicated as above. The medium and long-chain acyl-CoAs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada) as Li+ salts, and docosahexaenoyl-CoA (C22:6) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Palmitoyl-l-carnitine chloride was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used in a manner identical that of the acyl-CoAs, except the stock concentration was 300 mm. Palmitate (as a Na+ salt) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. MβCD was dissolved in PBS (20% wt/vol) and heated to 60 C. Palmitate was dissolved in 20% MβCD at a ratio of 3:100 [palmitate/MβCD (wt/wt)] and heated to 60 C and remained in solution upon cooling (43). A final stock concentration of 300 mm was used for experimentation. Vehicle was present in all control solutions.

Statistical Analysis

NCX1 currents were normalized to the peak control current. FM inactivation was expressed as the ratio of the steady-state current obtained after 1 min activation to the initial peak current (late-to-peak ratio). The rate of RM inactivation (τ) was obtained by fitting the current recorded for 50 sec after the peak current had been obtained with a best-fit single exponential function. Total NCX1 current was measured as the area under the curve during the 1-min activation period. Statistical significance was assessed using the paired or unpaired Student’s t test or a one-way ANOVA with a Bonnferoni post hoc test where required. P < 0.05 was considered significantly different.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. G.S Korbutt and K.L. Seeberger for provided human islet RNA and Dr. B.A Finegan and A. Lam for providing human atrial RNA. We also thank D.E. Dixon for the isolation of mouse islets.

Footnotes

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA) (to P.E.L.). P.E.M. was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. K.S.C.H. received support from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Strategic Training Initiative for the study of Membrane Proteins. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) and CDA trainee awards supported M.J.R. and N.J.W. AHFMR trainee awards supported D.S. and G.J.S. PEM received salary support as a CDA Scholar, AHFMR Scholar, and the Canada Research Chair in Islet Biology. P.E.L. received salary support as an AHFMR Senior Scholar.

Disclosure Statement: K.S.C.H., M.J.R., D.S., L.C.M., N.J.W., G.J.S., and P.E.L. have nothing to declare. P.E.M. received lecture fees from Merck Frosst Canada.

First Published Online July 17, 2008

K.S.C.H. and M.J.R. contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations: CoA, Coenzyme A; FM, forward mode; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MβCD, methyl-β-cyclodextrin; NCX, sodium-calcium exchanger; RM, reverse mode; XIP, exchanger inhibitor peptide.

References

- 1.Lytton J 2007. Na+/Ca2+ exchangers: three mammalian gene families control Ca2+ transport. Biochem J 406:365–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herchuelz A, Diaz-Horta O, Van Eylen F 2002. Na/Ca exchange in function, growth, and demise of β-cells. Ann NY Acad Sci 976:315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herchuelz A, Diaz-Horta O, van Eylen F 2002. Na/Ca exchange and Ca2+ homeostasis in the pancreatic β-cell. Diabetes Metab 28:3S54–S60; discussion 3S108–S112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicoll DA, Longoni S, Philipson KD 1990. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Science 250:562–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Z, Matsuoka S, Hryshko LV, Nicoll DA, Bersohn MM, Burke EP, Lifton RP, Philipson KD 1994. Cloning of the NCX2 isoform of the plasma membrane Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 269:17434–17439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicoll DA, Quednau BD, Qui Z, Xia YR, Lusis AJ, Philipson KD 1996. Cloning of a third mammalian Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, NCX3. J Biol Chem 271:24914–24921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kofuji P, Hadley RW, Kieval RS, Lederer WJ, Schulze DH 1992. Expression of the Na-Ca exchanger in diverse tissues: a study using the cloned human cardiac Na-Ca exchanger. Am J Physiol 263:C1241–C1249 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Lee SL, Yu AS, Lytton J 1994. Tissue-specific expression of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoforms. J Biol Chem 269:14849–14852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kofuji P, Lederer WJ, Schulze DH 1994. Mutually exclusive and cassette exons underlie alternatively spliced isoforms of the Na/Ca exchanger. J Biol Chem 269:5145–5149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Eylen F, Svoboda M, Herchuelz A 1997. Identification, expression pattern and potential activity of Na/Ca exchanger isoforms in rat pancreatic B-cells. Cell Calcium 21:185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shigekawa M, Iwamoto T 2001. Cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchange: molecular and pharmacological aspects. Circ Res 88:864–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuter H, Pott C, Goldhaber JI, Henderson SA, Philipson KD, Schwinger RH 2005. Na+/Ca2+ exchange in the regulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Cardiovasc Res 67:198–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwamoto T, Kita S 2006. Topics on the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger: role of vascular NCX1 in salt-dependent hypertension. J Pharmacol Sci 102:32–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilgemann DW 2004. Biochemistry. Oily barbarians breach ion channel gates. Science 304:223–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He Z, Feng S, Tong Q, Hilgemann DW, Philipson KD 2000. Interaction of PIP(2) with the XIP region of the cardiac Na/Ca exchanger. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278:C661–C666 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hilgemann DW 2003. Getting ready for the decade of the lipids. Annu Rev Physiol 65:697–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riedel MJ, Baczko I, Searle GJ, Webster N, Fercho M, Jones L, Lang J, Lytton J, Dyck JR, Light PE 2006. Metabolic regulation of sodium-calcium exchange by intracellular acyl CoAs. EMBO J 25:4605–4614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golay A, Swislocki AL, Chen YD, Jaspan JB, Reaven GM 1986. Effect of obesity on ambient plasma glucose, free fatty acid, insulin, growth hormone, and glucagon concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 63:481–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golay A, Swislocki AL, Chen YD, Reaven GM 1987. Relationships between plasma-free fatty acid concentration, endogenous glucose production, and fasting hyperglycemia in normal and non-insulin-dependent diabetic individuals. Metabolism 36:692–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaney GC, Corkey BE 2003. Fatty acid metabolism and insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells. Diabetologia 46:1297–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuoka S, Nicoll DA, Hryshko LV, Levitsky DO, Weiss JN, Philipson KD 1995. Regulation of the cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by Ca2+ Mutational analysis of the Ca2+-binding domain. J Gen Physiol 105:403–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilgemann DW, Matsuoka S, Nagel GA, Collins A 1992. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Sodium-dependent inactivation. J Gen Physiol 100:905–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilgemann DW 1990. Regulation and deregulation of cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchange in giant excised sarcolemmal membrane patches. Nature 344:242–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Eylen F, Bollen A, Herchuelz A 2001. NCX1 Na/Ca exchanger splice variants in pancreatic islet cells. J Endocrinol 168:517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, Nicoll DA, Collins A, Hilgemann DW, Filoteo AG, Penniston JT, Weiss JN, Tomich JM, Philipson KD 1991. Identification of a peptide inhibitor of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 266:1014–1020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuoka S, Nicoll DA, He Z, Philipson KD 1997. Regulation of cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by the endogenous XIP region. J Gen Physiol 109:273–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quednau BD, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD 1997. Tissue specificity and alternative splicing of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoforms NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 in rat. Am J Physiol 272:C1250–C1261 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Manning Fox JE, Nichols CG, Light PE 2004. Activation of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels by acyl coenzyme A esters involves multiple phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-interacting residues. Mol Endocrinol 18:679–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riedel MJ, Light PE 2005. Saturated and cis/trans unsaturated acyl CoA esters differentially regulate wild-type and polymorphic β-cell ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Diabetes 54:2070–2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes E, Lee AK, Tse A 2006. Dominant role of sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pump in Ca2+ homeostasis and exocytosis in rat pancreatic β-cells. Endocrinology 147:1396–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen L, Koh DS, Hille B 2003. Dynamics of calcium clearance in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes 52:1723–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Eylen F, Horta OD, Barez A, Kamagate A, Flatt PR, Macianskiene R, Mubaqwa K, Herchuelz A 2002. Overexpression of the Na/Ca exchanger shapes stimulus-induced cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in insulin-producing BRIN-BD11 cells. Diabetes 51:366–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Eylen F, Lebeau C, Albuquerque-Silva J, Herchuelz A 1998. Contribution of Na/Ca exchange to Ca2+ outflow and entry in the rat pancreatic β-cell: studies with antisense oligonucleotides. Diabetes 47:1873–1880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gall D, Gromada J, Susa I, Rorsman P, Herchuelz A, Bokvist K 1999. Significance of Na/Ca exchange for Ca2+ buffering and electrical activity in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Biophys J 76:2018–2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corkey BE, Deeney JT, Yaney GC, Tornheim K, Prentki M 2000. The role of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA esters in β-cell signal transduction. J Nutr 130:299S–304S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prentki M, Vischer S, Glennon MC, Regazzi R, Deeney JT, Corkey BE 1992. Malonyl-CoA and long chain acyl-CoA esters as metabolic coupling factors in nutrient-induced insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 267:5802–5810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang XQ, Song J, Rothblum LI, Lun M, Wang X, Ding F, Dunn J, Lytton J, McDermott PJ, Cheung JY 2001. Overexpression of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger alters contractility and SR Ca2+ content in adult rat myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281:H2079–H2088 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Dunn J, Elias CL, Le HD, Omelchenko A, Hryshko LV, Lytton J 2002. The molecular determinants of ionic regulatory differences between brain and kidney Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1) isoforms. J Biol Chem 277:33957–33962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ammala C, Eliasson L, Bokvist K, Larsson O, Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P 1993. Exocytosis elicited by action potentials and voltage-clamp calcium currents in individual mouse pancreatic B-cells. J Physiol 472:665–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gopel S, Kanno T, Barg S, Galvanovskis J, Rorsman P 1999. Voltage-gated and resting membrane currents recorded from B-cells in intact mouse pancreatic islets. J Physiol 521:717–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powell GL, Grothusen JR, Zimmerman JK, Evans CA, Fish WW 1981. A re-examination of some properties of fatty acyl-CoA micelles. J Biol Chem 256:12740–12747 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Constantinides PP, Steim JM 1985. Physical properties of fatty acyl-CoA. Critical micelle concentrations and micellar size and shape. J Biol Chem 260:7573–7580 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wray-Cahen D, Caperna TJ, Steele NC 2001. Methyl- β-cyclodextrin: an alternative carrier for intravenous infusion of palmitate during tracer studies in swine (Sus scrofa domestica). Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 130:55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]