Abstract

Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) are intracellular cation channels that mediate the rapid and voluminous release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) as required for excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Understanding of the architecture and gating of RyRs has advanced dramatically over the past two years, due to the publication of high resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) reconstructions and associated atomic models of multiple functional states of the skeletal muscle receptor, RyR1. Here we review recent advances in our understanding of RyR architecture and gating, and highlight remaining gaps in understanding which we anticipate will soon be filled.

Introduction

Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) are intracellular calcium release channels that facilitate the rapid liberation of Ca2+ from stores in the endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum (ER/SR) into the cytosol, typically in response to depolarization of the plasma membrane. Three RyR genes (RyR1, RyR2 and RyR3) exist, of which RyR1 and RyR2 are the best characterized, with particularly important functional roles in skeletal and cardiac muscle, respectively. Intracellular Ca2+ release plays a fundamental role in a range of signaling processes, including excitation-contraction (EC) coupling, whereby signals transmitted via the nervous system facilitate intracellular calcium release, which in turn activates contractile machinery in skeletal and/or cardiac muscle. In vitro, all RyRs are ligand-gated channels, activated by ATP and other adenine nucleotides, and sharing a biphasic activation/inhibition response to cytosolic Ca2+, as do the distantly related inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (InsP3Rs) [1].

In addition to their role in acute, large scale Ca2+ release during EC-coupling, RyRs also play an important role in maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis under resting conditions[2]. Shirking this responsibility results in leak of Ca2+ into the cytosol and consequent elevation of resting cytosolic [Ca2+], which is associated with several disease states[3], including cardiac arrhythmias and muscular dystrophy.

RyRs are homotetrameric cation channels, poorly selective for Ca2+ (~7 fold selective for Ca2+ vs K+)[4], with an exceptionally large single channel conductance, befitting their role as the “floodgates” of the intracellular Ca2+ stores. RyR activation must raise cytosolic [Ca2+] from ~100nM to ~10μM in a fraction of a second[2] in order to relieve inhibition of the contractile machinery, necessitating high conductance and cooperative opening. Cooperative activation is accomplished by assembly of RyRs into paracrystalline arrays of tens to hundreds of channels at the terminal cisternae[5], in which the state of each individual RyR influences that of the four neighboring channels[6]. RyRs exhibit a limited degree of homology in the transmembrane pore with voltage gated sodium (NaV) and potassium (Kv) channels, but stand apart from their distant cousins in part due to their sheer size. RyRs typically possess ~5000 residues in the single primary subunit[7–9], of which the last ~600–1000 encompass the transmembrane pore and a short C-terminal extension, and the remaining 4000 or so form a complex and interwoven cytosolic assembly.

The architecture of ryanodine receptors, both as isolated entities[10] and in a cellular context[11,12], was first addressed in the 1980s and 1990s primarily by electron microscopy - TEM and freeze-fracture EM of muscle tissue in the former case, and low-resolution single-particle cryoelectron microscopy (cryoEM) in the latter. These studies revealed for the first time the distinctive mushroom-like appearance of the receptor, in which the ‘stalk’ of the mushroom is buried in the SR membrane, and the ‘cap’ nearly touches the opposing plasma membrane of the T-tubule[12], in addition to locating the binding sites of several partner proteins in the tetramer[13–15]. Elegant freeze-fracture EM studies demonstrated that not only do RyRs form arrays in the SR membrane, they also interact with a complementary array of voltage-gated calcium channels (also known as dihydropyridine receptors, or DHPRs) in the T-tubule membrane[16]. In skeletal muscle, these arrays of DHPRs mechanically activate the RyR array upon membrane depolarization, acting like an electromechanical velcro patch at the contacting surfaces of the two membranes[17].

The first higher resolution glimpses of the receptor were provided by improved cryoEM reconstructions with resolutions ~10Å[18,19], a regime where the shapes of individual domains can be perceived with reasonable fidelity, in concert with crystal structures of several fragments of the receptor, most notably a three-domain N-terminal fragment spanning the first 532 residues[20], and a fragment encompassing the second tandem repeat pair of RYR domains, also known as the phosphorylation hotspot domain[21]. The availability of moderate resolution cryoEM envelopes allowed Van Petegem and colleagues to correctly ascertain the location of the N-terminal fragment in the cytosolic vestibule of the channel, and to predict the changes in interprotomer contacts they believed likely to occur upon gating[22]. For the convenience of the reader, Table 1 is provided to disambiguate the domain nomenclature used by groups in the field, in both the pre-atomic model and post-atomic model eras.

Table 1.

Nomenclature disambiguation

| des Georges et al. [30] | Yan et al. [23] | Samsó & Wagenknecht [18] |

|---|---|---|

| NTD-A | NTD-A | 2 |

| NTD-B | NTD-B | 4a |

| N-terminal solenoid (NSol) | NTD-C | 2a |

| SPRY1 | SPRY1 | 9 (“Clamp”) |

| RY1&2 | P1 | 10 (“Clamp”) |

| SPRY2 | SPRY2 | - |

| SPRY3 | SPRY3 | 5 |

| Junctional solenoid (JSol) | Handle domain | 3 (“Handle”) |

| Bridging solenoid (BSol) | Helical domain | 8,8a,4,6a,7 (“Clamp”) |

| RY3&4 | P2 | 6 |

| Core solenoid (CSol) | Central domain | - |

| EF1&2 | EF hand | 11 |

| Thumb-and-forefinger domain (TaF) | U-motif | - |

| pVSD | VSL | - |

| S2S3 | VSC | - |

| S4S5L/JM3 | S4S5L; “O-ring” | - |

| S6c | S6 | - |

| CTD | CTD | - |

CryoEM images at chain-tracing levels of resolution

The first global insights into RyR architecture on an atomic level were recently furnished by three high resolution cryoEM studies of RyR1 purified from rabbit skeletal muscle[23–25], facilitated by recent technological advances in cryoEM microscopy that have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere[26]. Of the three studies, one at 3.8Å resolution[23] provided a partially complete atomic model of the receptor, while the other two at somewhat lower resolution levels of 4.8 Å [24] and 6.1 Å [25] provided secondary structure and domain-level interpretations of RyR architecture. All three studies emphasized the initially surprising finding that the majority of the cytosolic region of the receptor is composed of many extended alpha solenoid repeat structures. The latter of the three studies [25] also included a notionally open-state structure, however the resolution of this structure was low (8.5Å), and the density was particularly weak in the pore region, making interpretation challenging. Further confounding matters, the authors used a concentration of Ca2+ in preparation of the sample that would be expected to have a very low open probability, due to the inhibitory effects of mM Ca2+[27].

The interpretations of the RyR1 structure in these cryoEM studies were facilitated by the inclusion of information from the crystal structures of RyR domains, and there have been continuing advances in such structural work in the intervening period, notably the structures of SPRY1[28], SPRY2[29] and the first RYR tandem repeat pair[28].

Recently, new structures of rabbit RyR1 have been solved in multiple functional states, including ligand-bound states and conditions in which the transmembrane pore is apparently in a conducting state [30]. Notably, three activating ligands, Ca2+, ATP and caffeine, all bind to different interdomain interfaces of the C-terminal domain, and upon binding elicit a rearrangement of the core of the channel (“priming”) that appears to be a pre-requisite intermediate for RyR opening. Further, this study reveals that the eponymous RyR ligand, ryanodine, binds within the transmembrane pore of the open RyR, locking the channel in an open state.

Two other recent studies describe the structure of RyR1 in an open state. In both cases, an activating ligand was used in addition to Ca2+ to lock the channel in an open state – PCB-95 in the case of the Bai et al. paper[31], and ruthenium red (RR) in the case of the Wei et al. paper[32]. The lower resolution of the open states from both studies (5.7Å for Bai et al., 4.9 Å for Wei et al.) precluded positive identification of the binding sites for either Ca2+ or the respective activating ligands used [31]. Fortunately, the RyR1 preparation of des Georges et al.[30] provided reconstructions at resolutions that range from 3.8 Å for the Ca2+-only state to 4.5 Å for the nominally Ca2+-free state, with resolutions of 4.4 Å overall and 4.2 Å in the pore regions for the open state. The improved resolution made it possible to improve the atomic model of the closed state, extending sequence registration with the maps significantly. A nearly complete atomic model (4168 of 5037 RyR1 residues plus all of calstabin 2/FKBP12.6) was fitted to the best map and then adapted to the other states. These recent results[30,31,32] largely eclipse prior descriptions of the RyR1 structure, and we focus our further discussion on these structures.

Architectural organization

RyR1 is a four-fold symmetric tetramer. If we consider the RyR1 tetramer as resembling a mushroom, then the “cap” (or shell) is formed by the first ~3600 residues of each protomer, while the hollow “stem” (or core) that forms the ion conduction pathway comprises the remaining ~1400 residues. The last 600 residues or so are embedded in the membrane, save the last hundred residues, which form a C-terminal domain (CTD) that integrates itself in the part of the stem that precedes the transmembrane region (Fig 1A).

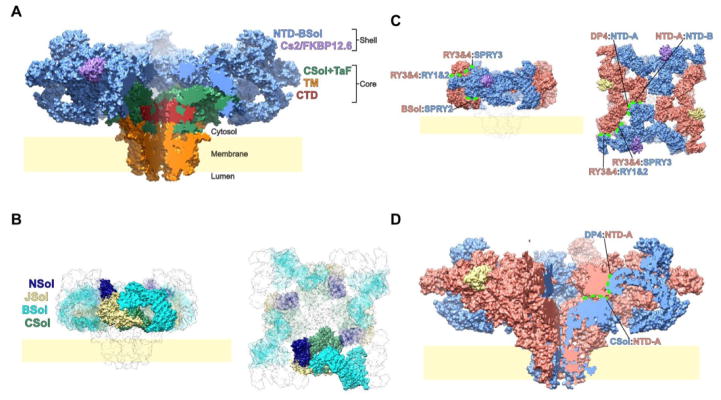

Fig. 1. RyR1 architecture and interprotomer interactions.

(A) The structure of RyR1-FKBP12.6 in the closed state is shown here as a solvent-excluded surface, with one quadrant removed to expose the interior. The shell region comprises the first 3613 residues (light blue), and bound Cs2/FKBP12.6 (light purple). The core comprises the core solenoid (CSol, green), the transmembrane region (orange) and the C-terminal domain (CTD, dark red). (B) The four α-solenoid domains of the receptor are depicted within a transparent surface, with those belonging to three of the four protomers semi-transparent to highlight those from the remaining protomer. (C) The shell region, with alternating RyR1/FKBP12.6 units colored salmon/khaki and light blue/purple, is depicted as a solvent excluded surface, with the remainder of the complex shown as a transparent surface. Notable interprotomer interactions within the shell are labeled. (D) The RyR tetramer, colored as in C, but depicted as in A, with one quarter removed to highlight interprotomer interactions between the core and the shell.

Considering the structure as a whole, it is immediately apparent that much of the extramembranous portion of the channel is assembled from four repetitive assemblies of alpha helices, which themselves form superhelical ribbons (α-solenoids) winding through the structure. Three of these α-solenoids - the N-terminal solenoid (NSol), the bridging solenoid (BSol) and the core solenoid (CSol) - converge at the fourth, junctional solenoid (JSol), with which they share a hydrophobic core (Fig 1B). Recently a high-resolution reconstruction of the related InsP3R1 channel was reported, showing that it shares much of this solenoid architecture, albeit lacking most of the bridging solenoid [33].

Three other domains are found in the “shell” of RyR1, all of which are repeated at least twice. These are the two N-terminal β-trefoil domains (NTD-A and NTD-B), the three SPRY domains (SPRY1-SPRY3) and the two tandem repeat domains (RY1&2 and RY3&4).

Interprotomer interactions within the shell can be divided into two main regions. Firstly, NTD-A interacts constitutively with a part of the bridging solenoid from the adjacent protomer, disruption of which leads to inappropriate channel activation[34,35], while forming a more labile interaction with NTD-B from the adjacent protomer. Secondly, the C-terminal end of the bridging solenoid forms simultaneous interactions with RY1&2 and SPRY2, of which the latter interaction appears to bury the most surface area (Fig 1C).

A short linker, the disordered N-terminal half of which contains the primary recruitment site for calmodulin[36], separates the bridging solenoid from the RyR1 core. The C-terminal half of the α-helical linker is ensconced within a hydrophobic groove in the surface of JSol, after which it enters the main body of CSol at residue 3666.

Excluding the transmembrane region, the RyR1 core can be divided into three domains - CSol, the EF1&2 domain (which is an insertion within CSol) and the thumb-and-forefingers (or TaF) domain, which is really a C-terminal extension of CSol. Each Csol domain forms interactions with the shell region of its own protomer and with both adjoining protomers. Considering intraprotomer interactions, the hydrophobic core of Csol is contiguous with that of JSol, and interactions are also present between NTD-B, N-sol and the upper convex surface of Csol. Interprotomer core-shell interactions primarily consist of the interaction of the upper surface of Csol with NTD-A from an adjacent protomer (Fig 1D).

The transmembrane pore has an overall architecture similar to that of a voltage-gated sodium or potassium channel, with the first four transmembrane helices (S1–S4) forming a compact bundle termed the pseudo voltage-sensor domain (pVSD), while the last two helices (S5&S6) from each protomer form the pore domain, with S6 helices lining the ion conduction pathway and a hemipenetrant pore helix (P-segment) forming the lumenal mouth of the channel, analogous to the selectivity filters of Kv and NaV channels[23,24]. The resemblance to Kv and NaV channels is less apparent on the cytosolic side of the membrane, where two domains unique to the RyR family of channels can be found. The first of these is a helical bundle domain (S2S3) which is inserted between S2 and S3, and the second of which is a C-terminal elaboration comprised of a cytosolic extension of S6 (S6c), and a C-terminal domain (CTD) containing a zinc finger motif[23]. The presence of a Zn2+-binding site is particularly notable given recent functional data[37,38] hinting at high affinity activation of the channel by Zn2+, although it is unclear whether the CTD site plays a functional or merely structural role. Both S2S3 and the CTD mediate interactions between the transmembrane region and the rest of the RyR1 core.

When in the “primed” conformation, activated but not opened, S2S3 forms an interface with the EF1&2 domain of an adjacent protomer; and this contact breaks apart on pore opening. Both these interacting domains are RyR-specific elements, absent from even the quite closely related InsP3R channels. The functional significance of this S2S3:EF1&2 interaction is unclear, although studies examining this interaction by exchanging the relevant segments of RyR1 and RyR2 suggest involvement of this interaction in Ca2+-dependent inactivation[39]. Three malignant hyperthermia mutation sites (F4732, G4733 & R4736) are located on the S2S3 domain at the interface with the EF1&2 domain from the adjacent protomer, and recombinant channels incorporating these mutations display defects in Ca2+-dependent inactivation [40]. It is however clear from a recent study where the EF1&2 domain was deleted, that this domain is not essential for channel activation by Ca2+ [41].

The CTD is engaged in a vice-like interaction with the TaF domain, in which the β-thumb of the TaF domain grips the upper surface of the CTD while the α-forefingers interact hold a lower CTD surface and the outer face of S6c. In addition to interactions with the TaF domain, the CTD is also engaged in interactions with S2S3, and with the lower surface of Csol.

Sites for activating ligands

Recent high resolution cryoEM reconstructions of RyR1 in complex with Ca2+, ATP and caffeine revealed that all three activating ligands bind at interfaces of the CTD with other domains within the same protomer (Fig. 2A). The clustering of all three binding sites around the C-terminal domain suggests a pivotal role for this region in RyR1 activation and gating, which is supported by functional studies demonstrating removal of residues at the very C-terminus severely compromises channel function [42].

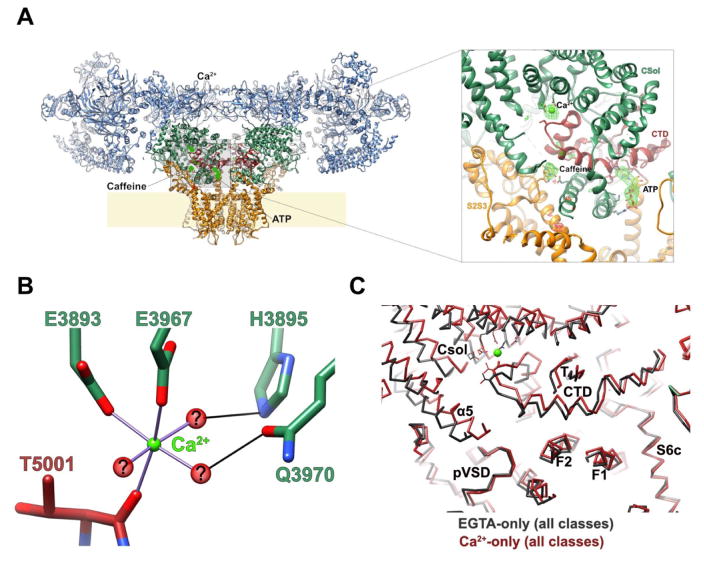

Fig. 2. Ca2+, ATP and caffeine all bind to interdomain interfaces of the CTD.

(A) Three RyR-activating ligands all bind to interdomain interfaces of the CTD. Here, and in the inset at right, the three ligands are shown with a difference density map calculated between the ligand-bound and apo- structures overlaid. (B) Coordination of the bound Ca2+ ion. Hypothetical water molecules are shown to highlight possible solvent-mediated interactions with Q3970 and H3895. (C) The conformational changes observed between the apo closed-state structure (charcoal) and a Ca2+-bound closed-state structure (dark red) are displayed here as an overlay of the two structures, aligned on the transmembrane region.

Ca2+ forms a bridging interaction between the CTD and the core solenoid, with two glutamate residues (E3967 & E3893) from CSol appearing crucial in ion coordination (Fig. 2A&B). ATP binds at a pocket formed by the mutual interface of S6c, the CTD and the TaF domain, wherein the nucleotide is wedged in a hydrophobic crevice within the CTD while the triphosphate tail interacts with a patch of positively charged residues on the first forefinger of the TaF domain. The caffeine binding site is located at the interface between the CTD and the S2S3 domain, where it apparently stabilizes this interdomain interaction, although in this case the orientation of the ligand could not be assigned unequivocally.

The Ca2+ binding site is likely to represent the high-affinity Ca2+ activation site of RyR1, given the concentration of free Ca2+ that was present in the sample (30μM) and the occurrence of E4032 in this at the same CTD:Csol interface since mutation of E4032 severely impedes Ca2+ activation. The question of where the lower affinity inhibitory Ca2+ site is located remains to be resolved. Likewise, the mechanism of RyR inhibition by Mg2+ is not entirely clear, although prior work suggests that cytoplasmic Mg2+ competes for the Ca2+ coordination site. If this is indeed the case, it is likely that Mg2+ inhibition derives from the different coordination preferences of the two ions - Ca2+ is more flexible in this regard, while Mg2+ sites typically have strictly octahedral geometry. It is plausible that the divergent coordination geometries of the two ions result in two slightly different dispositions of the CTD, one of which is associated with a lower-energy path to the open state than the other.

The effects of adenine derivatives on RyR activation exhibit a very distinct structure activity relationship, with two notable features. Firstly, the adenine moiety is essential for binding - neither pyrimidines nor even subtly modified purines such as inosine monophosphate bind to the channel[43]. Secondly, the triphosphate tail is crucial to the effects of the nucleotide on channel activity. The maximal open probability of the channel with varying [Ca2+] approaches 1.0 in the presence of ATP, and becomes progressively lower in the presence of ADP, AMP, adenosine and adenine, respectively[44]. The structure of the receptor in complex with ATP helps shed some light on both of these observations. ATP binds in such a manner that the nucleotide ring is buried deep in a mostly hydrophobic crevice, with the primary amine located at a break in the first α-helix of the CTD, where it may be coordinated by the exposed carbonyls at the end of the helix. Any other substituent at this position - a methyl or carbonyl for example - would encounter very unfavorable interactions at this position. The location of the triphosphate tail, mediating interactions with the TaF domain, suggests that this aspect of the effects of ATP/ADP/AMP on RyR1 activity is related to the conformational changes induced by ATP binding - it is plausible that binding of ADP and AMP could produce a less pronounced version of the “priming” conformational change described below. The physiological significance of adenine nucleotide regulation of RyRs remains unclear. At least in skeletal muscle, the overall cytosolic concentration of ATP is high enough that one would expect this ATP binding site to be saturated, even under conditions of fatigue; however, given the variations in ATP consumption across the muscle fiber (due to myosin motors and SERCA Ca2+ pumps), it is possible that the ATP/ADP/AMP ratio may locally be such that metabolic regulation of RyR1 activity by ATP/ADP/AMP may occur.

Activation and gating

Ligand binding to the CTD elicits a global conformational change, termed “priming”, which is necessary but insufficient for full-scale activation of the channel. This priming event involves reorientation of the CTD, accompanied by deformation of the CSol and TaF domains (Fig. 2C). Intriguingly, chemically distinct ligands (Ca2+ and ATP/caffeine), binding to different sites on the CTD (the former on the upper surface and the latter both on the membrane proximal face), induce very similar conformational changes.

One of the advantages of cryoEM as a structure determination technique is the capacity to classify (3D-classify) computationally and to extract multiple conformationally or compositionally distinct states of the molecule of interest from a single sample. This is of particular utility in the study of ion channels, which are inherently dynamic entities that stochastically flip between conducting and non-conducting states when active. As a consequence of this inherent conformational heterogeneity, obtaining crystal structures of multiple functional states of a single ion channel has proven a challenging task, in the absence of mutations or ligands to lock the structure in a particular state.

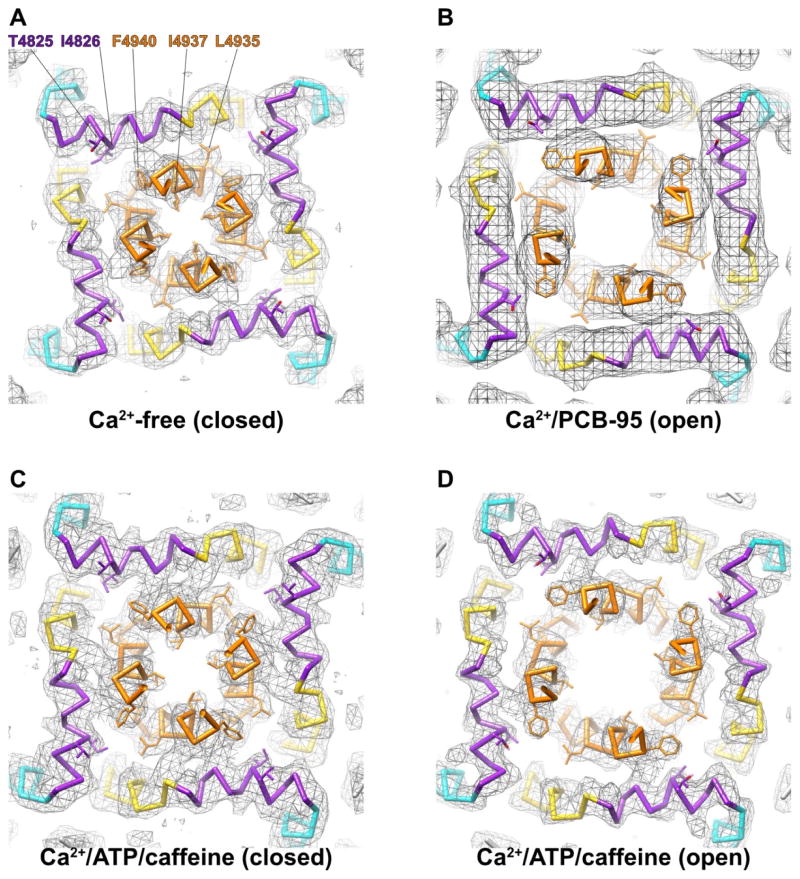

Applying 3D-classification to RyR1 in the presence of activating concentrations of Ca2+, ATP and caffeine made it possible to obtain structures of RyR1 with both open and closed pores under identical conditions, facilitating structural investigation of the stochastic gating transitions that occur at equilibrium. The structural nature of activation could be seen by comparison with an apo structure lacking all activating ligands. Comparison of the open and closed structures obtained in the presence of Ca2+, ATP and caffeine shows that transition between non-conducting (closed) and conducting (open) states involves dilation of the transmembrane pore at the hydrophobic gate residue, I4937, to an aperture sufficient for passage of a single hydrated Ca2+ ion. This opening is facilitated by bending and rotation of the S6/S6c helix (Fig. 3). The enlargement of the cytosolic aperture of the channel also necessitates expansion of the “girdle” of juxtamembrane helices (S4–S5 linker helices) that encircle the pore - as the channel opens, these helices straighten and alter their interactions with the pore-lining S6 helices. Pore expansion is also coincident with lateral displacement of the CTD and associated domains away from the channel axis.

Fig. 3. Structural basis of RyR1 gating.

Slabs of density and atomic models are shown for (A) the closed-state structure from Yan et al 2015, (B) the PCB-95 bound open state structure from Bai et al. 2016, and (C,D) the open and closed Ca2+/ATP/caffeine structures from des Georges et al 2016. In all panels, a 7 Å slab is oriented perpendicular to the channel axis, centered on the Cα of the hydrophobic gate residue, I4937. S4 is colored cyan, S4S5L (JM3) is colored purple, S5 is colored gold, and S6/S6c is colored orange. Several key residues are depicted in stick representation, labeled in A.

Bai et al.[31] and Wei et al.[32], in their studies of the Ca2+/PCB-95 and Ca2+/RR bound states of the receptor, made observations similar to those of des Georges et al.[30] regarding the global conformational changes of the receptor. A difference is that as they did not have access to the ligand bound closed-state structures, they interpreted these transitions as all being related to gating in a single-step mechanism; whereas the additional structures solved by des Georges et al. allow separation of activation and gating. Bai et al. noted that the detergent used for purification of the receptor was critically important to obtaining an open state[31]. Under otherwise similar conditions, the authors were able to identify an open state in the presence of CHAPS (the same detergent used by Zalk et al. and des Georges et al.) but not when using Tween-20 (the detergent used for the original Yan et al. closed state structure). Strikingly, in the presence of Tween-20, not only is the transmembrane pore closed, but the structural changes observed in the “priming” conformational change described by des Georges et al. are absent, and there is no evidence in the density map for the presence of a Ca2+ ion bound at the putative cytosolic activation site. This implies that the presence of Tween-20 not only inhibits the transition to the open state, but also to the “primed” state that is competent to bind Ca2+. Unfortunately the open-pore Ca2+/PCB-95 structure determined in the presence of CHAPS is of insufficient resolution (5.7Å) to assess the presence or absence of either activating ligand. Lacking definitive identification of the Ca2+-binding site, Wei et al. posited that the Ca2+-dependent displacement of the EF-hand pair is a result of Ca2+ binding to one of the two putative Ca2+ binding loops; however, the observation that the internal structure of the EF-hand pair does not change upon Ca2+-binding in the manner that one would expect for an EF-hand pair [30], along with the recent demonstration that the EF-hand pair is dispensable for Ca2+-activation[45] show that this assessment is unlikely to be correct.

Ryanodine locked open-pore state

The eponymous RyR-ligand ryanodine exhibits peculiar effects on RyR function. At low concentrations (nM-~10μM), ryanodine locks the channel in a state of unitary open probability but reduced single channel conductance, while at higher concentrations the same ligand blocks the channel, locking it in a non-conducting state[46]. Structural analysis of RyR1 in the presence of Ca2+ and ryanodine gives some insight as to the provenance of both effects. Unlike RyR1 in the presence of Ca2+/ATP/caffeine, where approximately half of the channels are closed, in the presence of ryanodine all 3D classes have a maximally dilated pore. In addition, new density features arise within the transmembrane pore, which are attributed to a single four-fold averaged ryanodine molecule t. The putative ryanodine binding site is offset from the channel axis, directly contacting the only hydrophilic residue lining the transmembrane cavity, Q4933, which is also the only residue unambiguously associated with ryanodine binding[47]. Although the quality of the density was insufficient to assign the orientation of ryanodine de novo, some clues can be gleaned from prior studies on the structure-activity relationship of synthetic ryanoids. Most notably, alterations at the 10’ position on the ryanoid scaffold affect the conductance of the modified channel, without impacting affinity, suggesting that this position is likely oriented towards the channel axis, where it can interact with the permeant ion as it traverses the membrane[48,49]. Precise assignment of the mechanism of open channel lock awaits higher resolution studies where the ryanodine orientation may be gleaned more precisely, but current observations are consistent with a model in which ryanodine prevents channel closure by intercalating between the S6 helices from adjacent channel protomers. The observation that the four equivalent ryanodine binding sites are located in close proximity within the transmembrane conduction pathway also suggests a possible mechanism for high-ryanodine channel block, in which binding of ryanodine to a single site reduces affinity for the remaining sites due to steric hindrance, and multiple occupancy of the conduction pathway by ryanodine molecules prevents ion conduction by steric interference.

Conclusions

The last two years have produced exciting advances in our understanding of ryanodine receptor structure and dynamics, and provided significant mechanistic insights into RyR function. It is important to emphasize, however, that we still lack a complete high resolution structure of the channel; even in the most complete structure, ~1000 residues in the BSol and SPRY3 domains remain unassigned, and higher local resolution in these regions (or crystal structures of appropriate fragments) will be required before a complete atomic model of the receptor is available. Nevertheless, recently solved structures of the receptor in multiple ligand bound states, including open states, have provided significant insights into the structural basis of ryanodine receptor activation and ligand binding. Most notably, these studies have demonstrated that activation is at least a two state process, in which ligand binding first induces a conformational change in the core of the receptor that permits opening, and then the synergistic binding of additional ligands increases the probability of transition to an open pore state. One outstanding question concerns the activation barrier that restricts channel opening from the primed state without having multiple ligands present. Another major remaining question, which now appears to be tractable to structural dissection, concerns how voltage gated calcium channels in the plasma membrane interact with and mechanically activate RyR1, and how RyR1 oligomerizes in the membrane to form paracrystalline arrays at the terminal cisternae. We anticipate that the recent availability of high resolution reconstructions of both RyR1 and CaV1.1[50,51], as well as application of direct detector technology to cryoelectron tomography studies of either muscle tissue or purified triads, will lead to rapid advances on this front as well.

Highlights.

Extended α-solenoid domains form a cytosolic scaffold with a core-shell structure

The transmembrane pore is reminiscent of Kv/Nav channels, with unique insertions

Three activating ligands - Ca2+, ATP and caffeine - all bind at the C-terminal domain interfaces

Ligand binding leads to a rearrangement of the channel core that primes RyR1 to open

Ryanodine locks the pore in an open state by binding in the TM conduction pathway

PCB-95 and Ruthenium Red also lock the pore in an open state, binding sites unknown

Notes Added in Proof.

After our submission of this review, the PDB released files that had been deposited for structures described by Wei et al. [32] on RyR1 in the presence of Ca2+ and ruthenium red. We were then able to compare this structure with those determined by des Georges et al. [29]. We now find that the structure (PDBid: 5J8V) is very similar to that of the Ca2+-only state (PDBid: 5T15) of Ref. [30], and that the density map (EMD-8074 ) confirms the presence of Ca2+ in the same site as shown here in Figure 2a. The conformational changes described by Wei et al. do not lead to opening, however, but leave the pore constricted as in Figure 3c here.

CryoEM structures have been reported for porcine RyR2 in a closed state at 4.2Å resolution and in an open state at 4.1Å resolution (W. Peng et al., Science 10.1126/science.aah5324 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We thank our coworkers R. Zalk, A. des Georges, A.R. Marks, J. Frank and F. Mancia for sharing insights into the structure and activity of RyR1. This work was supported in part by NIH grant P41GM116799 to WAH and by a Charles H. Revson Senior Fellowship to OBC.

References

- 1.Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, Ehrlich BE. Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature. 1991;351:751–754. doi: 10.1038/351751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zahradníková A, Zahradník I, Györke I, Györke S. Rapid activation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor by submillisecond calcium stimuli. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:787–798. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.6.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zalk R, Lehnart SE, Marks AR. Modulation of the ryanodine receptor and intracellular calcium. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:367–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.053105.094237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramachandran S, Chakraborty A, Xu L, Mei Y, Samso M, Dokholyan NV, Meissner G. Structural Determinants of Skeletal Muscle Ryanodine Receptor Gating. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6154–6165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.433789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baddeley D, Jayasinghe ID, Lam L, Rossberger S, Cannell MB, Soeller C. Optical single-channel resolution imaging of the ryanodine receptor distribution in rat cardiac myocytes. PNAS. 2009;106:22275–22280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908971106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marx SO, Ondrias K, Marks AR. Coupled gating between individual skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channels (ryanodine receptors) Science. 1998;281:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeshima H, Nishimura S, Matsumoto T, Ishida H, Kangawa K, Minamino N, Matsuo H, Ueda M, Hanaoka M, Hirose T. Primary structure and expression from complementary DNA of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Nature. 1989;339:439–445. doi: 10.1038/339439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks AR, Tempst P, Hwang KS, Taubman MB, Inui M, Chadwick C, Fleischer S, Nadal-Ginard B. Molecular cloning and characterization of the ryanodine receptor/junctional channel complex cDNA from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1989;86:8683–8687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zorzato F, Fujii J, Otsu K, Phillips M, Green NM, Lai FA, Meissner G, MacLennan DH. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding human and rabbit forms of the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2244–2256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito A, Inui M, Radermacher M, Frank J, Fleischer S. Ultrastructure of the calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:211–219. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Protasi F, Franzini-Armstrong C, Flucher BE. Coordinated incorporation of skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptors and ryanodine receptors in peripheral couplings of BC3H1 cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:859–870. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.4.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagenknecht T, Hsieh C-E, Rath BK, Fleischer S, Marko M. Electron tomography of frozen-hydrated isolated triad junctions. Biophys J. 2002;83:2491–2501. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75260-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagenknecht T, Grassucci R, Berkowitz J, Wiederrecht GJ, Xin HB, Fleischer S. Cryoelectron Microscopy Resolves FK506-Binding Protein Sites. Biophys J. 1996;70:1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79733-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samso M, Trujillo R, Gurrola GB, Valdivia HH, Wagenknecht T. Three-dimensional location of the imperatoxin A binding site on the ryanodine receptor. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:493–499. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samsó M, Wagenknecht T. Apocalmodulin and Ca2+-calmodulin bind to neighboring locations on the ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1349–1353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paolini C, Protasi F, Franzini-Armstrong C. The Relative Position of RyR Feet and DHPR Tetrads in Skeletal Muscle. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paolini C, Fessenden JD, Pessah IN, Franzini-Armstrong C. Evidence for conformational coupling between two calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2004;101:12748–12752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404836101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serysheva II, Ludtke SJ, Baker ML, Cong Y, Topf M, Eramian D, Sali A, Hamilton SL, Chiu W. Subnanometer-resolution electron cryomicroscopy-based domain models for the cytoplasmic region of skeletal muscle RyR channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2008;105:9610–9615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803189105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludtke SJ, Serysheva II, Hamilton SL, Chiu W. The pore Structure of the closed RyR1 channel. Structure. 2005;13:1203–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tung C-C, Lobo PA, Kimlicka L, Van Petegem F. The amino-terminal disease hotspot of ryanodine receptors forms a cytoplasmic vestibule. Nature. 2010;468:585–588. doi: 10.1038/nature09471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma P, Ishiyama N, Nair U, Li W, Dong A, Miyake T, Wilson A, Ryan T, MacLennan DH, Kislinger T, et al. Structural determination of the phosphorylation domain of the ryanodine receptor. FEBS J. 2012;279:3952–3964. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong X, Liu Y, Zhu L, Meng X, Wang R, Van Petegem F, Wagenknecht T, Chen SRW, Liu Z. Conformational dynamics inside amino-terminal disease hotspot of ryanodine receptor. Structure. 2013;21:2051–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23**.Yan Z, Bai X-C, Yan C, Wu J, Li Z, Xie T, Peng W, Yin C-C, Li X, Scheres SHW, et al. Structure of the rabbit ryanodine receptor RyR1 at near-atomic resolution. Nature. 2015;517:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature14063. With the highest resolution (3.8Å) of the three initial papers describing the architecture of rabbit RyR1, this paper provided the most detailed description of the architecture of the channel in the closed state, including a partial atomic model of the receptor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24**.Zalk R, Clarke OB, Georges des A, Grassucci RA, Reiken S, Mancia F, Hendrickson WA, Frank J, Marks AR. Structure of a mammalian ryanodine receptor. Nature. 2015;517:44–49. doi: 10.1038/nature13950. This paper, along with the Yan et al and Efremov et al papers, provided the first domain-level description of the architecture of RyR1, at a chain-tracing level of resolution (4.8Å) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Efremov RG, Leitner A, Aebersold R, Raunser S. Architecture and conformational switch mechanism of the ryanodine receptor. Nature. 2015;517:39–43. doi: 10.1038/nature13916. The reconstructions of RyR1 provided here were at lower resolution (6.2Å) than the other two initial papers, but were determined in a native lipidic (nanodisc) environment, providing an important point of comparison, and included a structure determined in the presence of Ca2+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng Y. Single-Particle Cryo-EM at Crystallographic Resolution. Cell. 2015;161:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, Ehrlich BE. Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature. 1991;351:751–754. doi: 10.1038/351751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Yuchi Z, Yuen SMWK, Lau K, Underhill AQ, Cornea RL, Fessenden JD, Van Petegem F. Crystal structures of ryanodine receptor SPRY1 and tandem-repeat domains reveal a critical FKBP12 binding determinant. Nat Comms. 2015;6:7947. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8947. As with previous crystal structures of RyR domains, these results provided definitive high resolution information that enabled interpretation of recent cryoEM images of RyR1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29*.Lau K, Van Petegem F. Crystal structures of wild type and disease mutant forms of the ryanodine receptor SPRY2 domain. Nat Comms. 2014;5:1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6397. As with previous crystal structures of RyR domains, these results provided definitive high resolution information that enabled interpretation of recent cryoEM images of RyR1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30**.des Georges A, Clarke OB, Zalk R, Yuan Q, Kondon KJ, Grassucci RA, Hendrickson WA, Marks AR, Frank J. Structural basis for gating and activation of RyR1. Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.075. in press. The authors obtained reconstructions of multiple functional states of RyR1, resolving the binding sites of Ca2+, ATP, caffeine and ryanodine, as well as characterizing the structural basis of both activation and stochastic gating of RyR1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Bai X-C, Yan Z, Wu J, Li Z, Yan N. The Central domain of RyR1 is the transducer for long-range allosteric gating of channel opening. Cell Res. 2016;26:995–1006. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.89. The authors obtained, along with new reconstructions of the closed state of RyR1, a reconstruction of the PCB-95 activated open state at a resolution of 5.7Å. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Wei R, Wang X, Zhang Y, Mukherjee S, Zhang L, Chen Q, Huang X, Jing S, Liu C, Li S, et al. Structural insights into Ca(2+)-activated long-range allosteric channel gating of RyR1. Cell Res. 2016;26:977–994. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.99. The authors obtained a reconstruction of the ruthenium red activated open state of RyR1, at an overall resolution of 4.9 Å (4.2Å in the core of the molecule) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33*.Fan G, Baker ML, Wang Z, Baker MR, Sinyagovskiy PA, Chiu W, Ludtke SJ, Serysheva II. Gating machinery of InsP3R channels revealed by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2015;527:336–341. doi: 10.1038/nature15249. A 4.7Å cryoEM reconstruction of InsP3R1 provides the first glimpse of the architecture of this class of channels, revealing an architecture that has many similarities to that of the RyRs, including an extended alpha solenoid scaffold in the cytosol, but with notable differences, particularly the absence of both the EF1&2 and S2S3 domains. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamb GD, Posterino GS, Yamamoto T, Ikemoto N. Effects of a domain peptide of the ryanodine receptor on Ca2+ release in skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C207–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bannister ML, Hamada T, Murayama T, Harvey PJ, Casarotto MG, Dulhunty AF, Ikemoto N. Malignant hyperthermia mutation sites in the Leu2442–Pro2477 (DP4) region of RyR1 (ryanodine receptor 1) are clustered in a structurally and functionally definable area. Biochem J. 2007;401:333–339. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore CP, Rodney G, Zhang JZ, Santacruz-Toloza L, Strasburg G, Hamilton SL. Apocalmodulin and Ca2+ calmodulin bind to the same region on the skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8532–8537. doi: 10.1021/bi9907431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodier J, Rainbow RD, Stewart AJ, Pitt SJ. Intracellular Zinc Modulates Cardiac Ryanodine Receptor-mediated Calcium Release. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:17599–17610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.661280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulien AJ, Justice JA, Di Maio R, Wills ZP, Shah NH, Aizenman E. Zn 2+-induced Ca 2+release via ryanodine receptors triggers calcineurin-dependent redistribution of cortical neuronal Kv2.1 K +channels. J Physiol. 2016;594:2647–2659. doi: 10.1113/JP272117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez AC, Yamaguchi N. Two Regions of the Ryanodine Receptor Calcium Channel Are Involved in Ca 2+-Dependent Inactivation. Biochemistry. 2014;53:1373–1379. doi: 10.1021/bi401586h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Gomez AC, Holford TW, Yamaguchi N. Malignant Hyperthermia-Associated Mutations in S2–S3 Cytoplasmic Loop of Type 1 Ryanodine Receptor Calcium Channel Impair Calcium-Dependent Inactivation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016 Aug 24; doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00134.2016. [Epub ahead of print]. This paper provides better definition for the conclusion, also realized in Ref. 39, that S2S3:EF1&2 interactions are important for Ca2+-dependent inactivation and finds these sites to be those found in primed-state RyR1 structures. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41**.Guo W, Sun B, Xiao Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang R, Chen SRW. The EF-hand Ca2+ Binding Domain Is Not Required for Cytosolic Ca2+ Activation of the Cardiac Ryanodine Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2015;291:2150–2160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.693325. The authors demonstrate that neither mutation of residues within EF1&2 nor deletion of the entire domain (in RyR2) affects activation by cytosolic Ca2+, but does impact acitvation by luminal Ca2+ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao L, Tripathy A, Lu X, Meissner G. Evidence for a role of C-terminal amino acid residues in skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) function. FEBS Letters. 1997;412:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laver DR, Lenz GK, Lamb GD. Regulation of the calcium release channel from rabbit skeletal muscle by the nucleotides ATP, AMP, IMP and adenosine. J Physiol. 2001;537:763–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan WM, Welch W, Sitsapesan R. Structural factors that determine the ability of adenosine and related compounds to activate the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1618–1626. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo W, Sun B, Xiao Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang R, Chen SRW. The EF-hand Ca2+ Binding Domain Is Not Required for Cytosolic Ca2+ Activation of the Cardiac Ryanodine Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:2150–2160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.693325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagasaki K, Fleischer S. Ryanodine sensitivity of the calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Cell Calcium. 1988;9:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(88)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ranatunga KM, Chen SRW, Ruest L, Welch W, Williams AJ. Quantification of the effects of a ryanodine receptor channel mutation on interaction with a ryanoid. Mol Membr Biol. 2007;24:185–193. doi: 10.1080/09687860601076522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welch W, Ahmad S, Airey JA, Gerzon K, Humerickhouse RA, Besch HR, Ruest L, Deslongchamps P, Sutko JL. Structural determinants of high-affinity binding of ryanoids to the vertebrate skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor: a comparative molecular field analysis. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6074–6085. doi: 10.1021/bi00186a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welch W, Williams AJ, Tinker A, Mitchell KE, Deslongchamps P, Lamothe J, Gerzon K, Bidasee KR, Besch HR, Airey JA, et al. Structural components of ryanodine responsible for modulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium channel function. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2939–2950. doi: 10.1021/bi9623901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu J, Yan Z, Li Z, Yan C, Lu S, Dong M, Yan N. Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1.1 complex. Science. 2015;350:aad2395–aad2395. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51**.Wu J, Yan Z, Li Z, Qian X, Lu S, Dong M, et al. Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1.1 at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature. 2016 Aug 31; [Epub ahead ofprint]. This paper extends the resolution (from 4.2Å in Ref. 50) and structural definition of the plasma membrane calcium channel that mechanically couples to RyR1 during excitation-contraction coupling. [Google Scholar]