Abstract

Ad4BP/SF-1 [adrenal4 binding protein/steroidogenic factor-1 (NR5A1)] is a factor important for animal reproduction and endocrine regulation, and its expression is tightly regulated in the gonad, adrenal gland, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus, and pituitary gonadotrope. Despite its functional significance in the pituitary, the mechanisms underlying pituitary-specific expression of the gene remain to be uncovered. In this study, we demonstrate by transgenic mouse assays that the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer is localized within the sixth intron of the gene. Functionally, the enhancer recapitulates endogenous Ad4BP/SF-1 expression in the fetal Rathke’s pouch to the adult pituitary gonadotrope. Structurally, the enhancer consists of several elements conserved among animal species. Mutational analyses confirmed the significance of these elements for the enhancer function. One of these elements was able to interact both in vitro and in vivo with Pitx2 (pituitary homeobox 2), demonstrating that pituitary homeobox 2 regulates Ad4BP/SF-1 gene transcription in the pituitary gonadotrope via interaction with the gonadotrope-specific enhancer.

THE PITUITARY GLAND is composed of anterior, intermediate, and posterior lobes. This small organ regulates growth, metabolism, stress response, and fertility of animals, by releasing six physiologically distinct hormones from each hormone-elaborating cell type in the anterior and intermediate pituitary, i.e. GH from somatotropes, prolactin from lactotropes, ACTH from corticotropes, TSH from thyrotropes, FSH and LH from gonadotropes, and MSH from the intermediate melanotropes. Developmentally, the anterior and intermediate lobes arise from the same primordium: Rathke’s pouch (Rp). Thereafter, the cells in this structure begin to differentiate into each specified cell type. Initially, gradients of signaling molecules give positional cues to the primitive cells in Rp and cause subsequent patterning and cell-specific induction of transcription factors. Subsequently, these transcription factors induce terminal differentiation of each cell type (1, 2).

Gonadotropes arise from the cells located in the most ventral part of Rp and initiate the expression of LH and FSH at embryonic d 16.5 (E16.5)–E17.5 in mice. Ad4BP/SF-1 [adrenal4 binding protein (3)/steroidogenic factor-1 (4), also known as ELP (5) or FTZ-F1 (6), officially designated NR5A1 (7), GenBank identification no. 24623] has been characterized as a molecule required for differentiation of the gonadotropes. In the pituitary, this factor is initially transcribed at E13.5–E14.5, shortly before the appearance of LH and FSH expression, and its expression is strictly confined to the gonadotrope lineage (8). Ad4BP/SF-1 gene-disrupted mice showed markedly reduced expression levels of both LH and FSH because of decreased number of the gonadotrope, in addition to the gonadal and adrenal agenesis and abnormal formation of the VMH (ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus) (9, 10). Moreover, pituitary-specific Ad4BP/SF-1 gene knockout mice displayed infertility and sexual immaturity due to markedly decreased gonadotropin levels (11). Consistent with these in vivo observations, Ad4BP/SF-1 activates the transcription of gonadotrope-specific genes such as α-glycoprotein hormone subunit (12, 13, 14), LHβ (15, 16, 17, 18, 19), GnRH receptor (GnRHr) (20, 21), and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (22) via gonadotrope-specific elements recognized by Ad4BP/SF-1 [reviewed by Fowkes and Burrin (23)]. Therefore, Ad4BP/SF-1 is considered essential for proliferation and differentiation of the gonadotropes at an early developmental stage of the pituitary gland as well as for synthesis of the gonadotropins in the pituitary.

Because Ad4BP/SF-1 plays crucial roles and its functions are closely related to tissue specificities, transgenic studies have been performed to investigate the molecular mechanisms that drive the tissue-specific expression. One of them demonstrated that the basal promoter region is sufficient to drive lacZ reporter gene expression in the sexually indifferent gonad (24), whereas other studies revealed that highly conserved regions in the fourth and sixth introns are capable of driving the expression in the fetal adrenal cortex (25) and VMH (26), respectively. These studies highlighted a novel aspect of Ad4BP/SF-1 gene regulation in vivo and elucidated the molecular mechanisms that enable the gene to be expressed in tissue-specific manners.

Pitx2 (Pituitary homeobox 2, also known as Ptx2, Brx1, or Rieg, GenBank identification no. 18741) is a member of the bicoid-related homeobox gene family and is known as one of the genes responsible for Rieger syndrome, an autosomal-dominant human disorder characterized by variable anomalies of the eye, teeth, umbilicus, and pituitary (27, 28). This factor was then identified to have similar transcriptional property to another Pitx member of homeobox transcription factor, Pitx1 (29), and it was also revealed that these two factors show overlapping expression patterns in the stomodeum and its derivatives, including the pituitary gland (30, 31). Gage et al. (32) modified Pitx2 gene locus to generate mice harboring differential Pitx2 gene dosages with hypomorphic and/or null alleles of the gene and demonstrated that Pitx2 is required for the pituitary ontogeny at various stages. Moreover, gonadotrope-specific markers such as GATA2, early growth response gene-1 (EGR-1), and Ad4BP/SF-1 were not detected at all in the anterior pituitary of mice harboring two hypomorphic Pitx2 alleles (33). In another study, it was also revealed that overexpressed Pitx2 could increase the number of Ad4BP/SF-1-positive gonadotropes without affecting other cell types (31).

In the present study, we localized the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer of Ad4BP/SF-1 gene in the sixth intron and characterized it in terms of structure and function by transgenic studies. The enhancer region contains several elements conserved among animal species, and one of them was able to interact with Pitx2. Transient transgenic analyses and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays suggested that Pitx2 is implicated in Ad4BP/SF-1 gene transcription through interaction with the Pitx2 recognition sequence in the enhancer region. Although previous studies indicated that Pitx2 acts as an upstream regulator of Ad4BP/SF-1 gene in the pituitary (31, 33), it remains to be resolved whether the regulation is direct or indirect. This is the first report that demonstrates a functional correlation between the two factors, Pitx2 and Ad4BP/SF-1, both essential for the gonadotrope development.

RESULTS

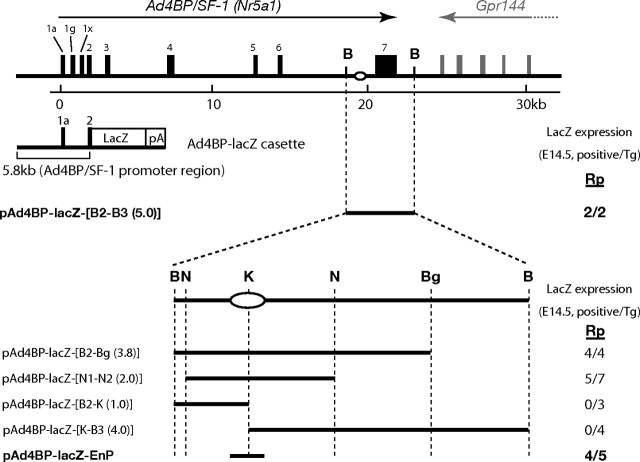

Localization of a DNA Fragment Capable of Inducing Gene Expression in Rp

Our previous transgenic studies showed that pAd4BP-lacZ-[B2-B3(5.0)] harboring a 5.0-kb BamHI-BamHI fragment ranging from intron 6 to 3′-untranslated region of the Ad4BP/SF-1 gene (Fig. 1) potentially induces lacZ reporter gene expression in Rp (26). Thus, in the present study, we further truncated this 5.0-kb fragment to localize precisely the Rp-specific enhancer. To localize the functional enhancers, we adopted transient transgenic mouse analyses in which transgenic founder mice were killed and analyzed at fetal stages after every DNA injection. As shown in Fig. 1, pAd4BP-lacZ-[B2-Bg(3.8)] and pAd4BP-lacZ- [N1-N2(2.0)] carrying a 3.8-kb BamHI–BglII fragment and a 2.0-kb NcoI–NcoI fragment, respectively, induced lacZ expression in Rp, whereas pAd4BP-lacZ-[B2-K(1.0)] and pAd4BP-lacZ-[K-B3(4.0)] failed to induce such expression. These observations strongly suggested that the whole enhancer region is localized in the N1–N2(2.0) fragment and digestion at the KpnI site divided the enhancer region into B2-K(1.0) and K-B3(4.0).

Fig. 1.

Localization of PE of Ad4BP/SF-1 Gene

Ad4BP/SF-1 gene consists of seven exons (solid boxes), including noncoding multiple first exons, exon Ia, Ig, and Ix (exon Io is not active in the mouse gene). Gpr144 gene is localized at the 3′ downstream of Ad4BP/SF-1. A 5.8-kb fragment of the Ad4BP/SF-1 promoter region from the initiation methionine in exon 2 together with lacZ gene and simian virus 40 poly (A) signal were used to generate Ad4BP-lacZ cassette. LacZ expression in Rp of the transgenic founder animals was evaluated at E14.5, and the result for each construct is shown as number of lacZ-positive founders per number of transgenic founders. As described previously (26 ), a 5.0-kb long BamHI–BamHI fragment was identified to have an Rp-specific enhancer activity. Thus, the fragment was further truncated, cloned into Ad4BP-lacZ cassette, and subjected to transgenic assays. The tentative location of the Rp-specific enhancer is shown by an oval. B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; K, KpnI; N, NcoI.

Based on this finding, we compared the nucleotide sequence around the KpnI site of the mouse gene with other vertebrate species because the functional genomic sequences are expected to be conserved among animal species (34). As will be described later in detail (see Fig. 4), the nucleotide sequences were highly conserved among animal species. To address whether the conserved region functions as the Rp-specific enhancer, the region (486-bp) was amplified by PCR and used to construct pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP. Expectedly, transient transgenic analyses demonstrated that the region acts potentially as the Rp-specific enhancer at E14.5 (Fig. 1).

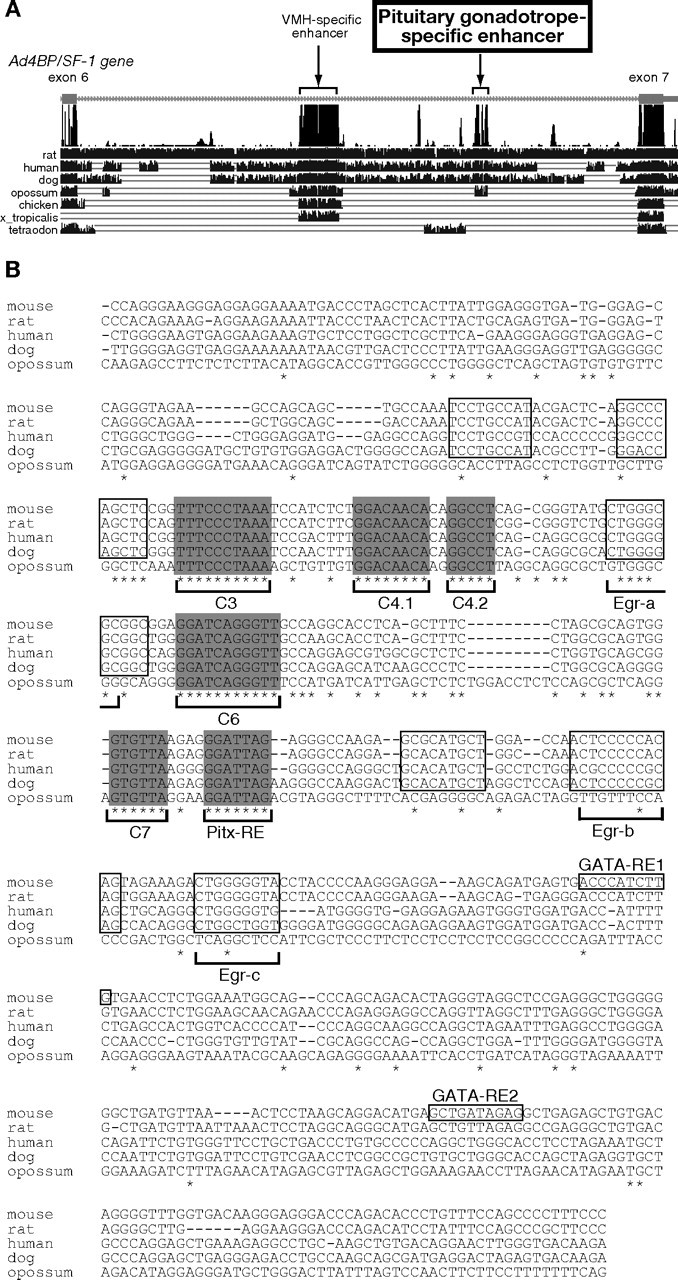

Fig. 4.

Conserved Nucleotide Sequences in the PE

A, Conservation of the enhancer sequences among animal species. Genomic sequence between exons 6 and 7 of the mouse Ad4BP/SF-1 gene was compared with those of rat, human, dog, opossum, chicken, Xenopus tropicalis, and Tetraodon using UCSC genome browser. The regions with vertical lines indicate sequences conserved. The uppermost line demonstrates summary of conservation among the animal species. B, Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer regions among mammalian species. Asterisks indicate the nucleotides conserved in all five species. Gray boxes (C3, C4.1, C4.2, C6, C7, Pit-RE) indicate sequences with more than five consecutively conserved nucleotides, and open boxes indicate sequences conserved in mouse, rat, human, and dog, but not in opossum. Candidate sequences for EGR-1 binding sites are indicated as Egr-a, Egr-b, and Egr-c. Consensus sequences for GATA-2 recognition are also indicated as GATA-RE1 and GATA-RE2.

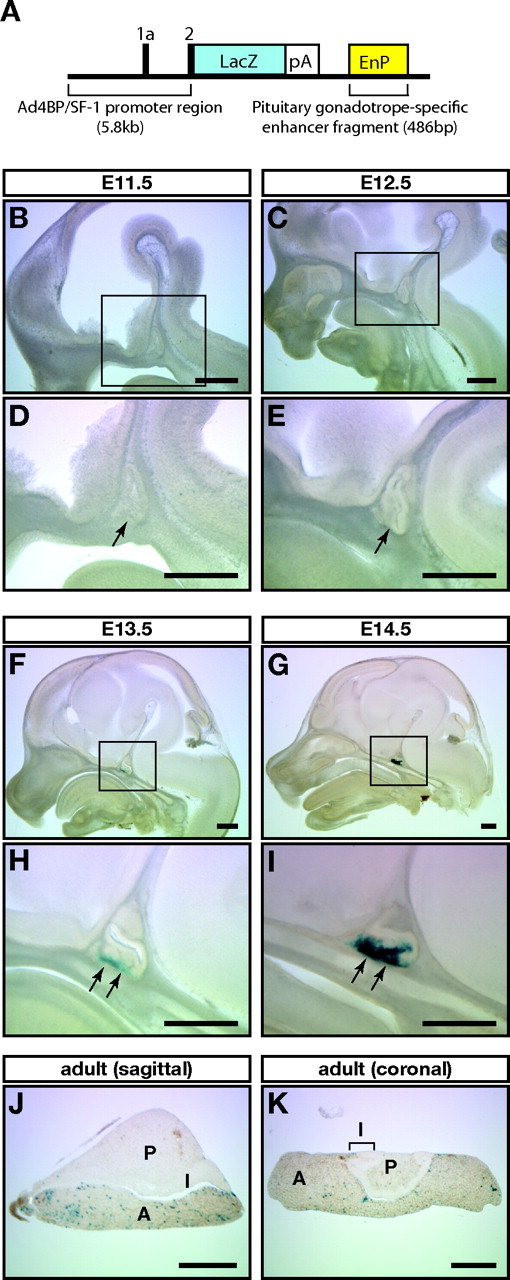

To characterize the reporter gene expression driven by the enhancer, we generated three transgenic mouse lines with pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP (Fig. 2A). Although one line showed ectopic lacZ expression, the other two showed expression specifically in the developing Rp and the adult pituitary gland. Figure 2 shows a representative expression profile of one line termed Ad4-EnP-lacZ (line 3). As described previously (8, 9, 10), the endogenous expression of Ad4BP/SF-1 is initially recognized in the ventral part of Rp at E13.5 and gradually expands throughout the anterior lobe of the pituitary. Thereafter, the expression of Ad4BP/SF-1 becomes specific to the gonadotropes. Consistent with the endogenous expression, lacZ was not expressed in Rp E11.5 and E12.5 (Fig. 2, B–E) but was weakly expressed in the ventral part of Rp at E13.5 (Fig. 2, F and H). The expression became robust at E14.5 (Fig. 2, G and I). In the adult, lacZ-positive cells were sparsely distributed in the anterior pituitary whereas such cells were observed in neither the posterior nor the intermediate lobe (Fig. 2, J and K).

Fig. 2.

LacZ Expression Induced by PE

A, A scheme of the construct used for generating Ad4-EnP-lacZ transgenic mouse lines. The 486-bp pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer fragment (EnP) was localized downstream of the lacZ reporter gene. pA, Polyadenylation signal. B–K, LacZ expression pattern in Ad4-EnP-lacZ transgenic mice (line 3). Rps at E11.5 (B and D), E12.5 (C and E), E13.5 (F and H), and E14.5 (G and I) were sectioned sagittally, whereas adult pituitaries were sectioned sagittally (J) or coronally (K). The sections were then subjected to X-gal staining. D, E, H, and I, Enlarged views of the boxed areas in B, C, F, and G, respectively. Arrows in D, E, H, and I indicate Rps. A, Anterior lobe; I, intermediate lobe; P, posterior lobe. Bars, 200 μm in all panels.

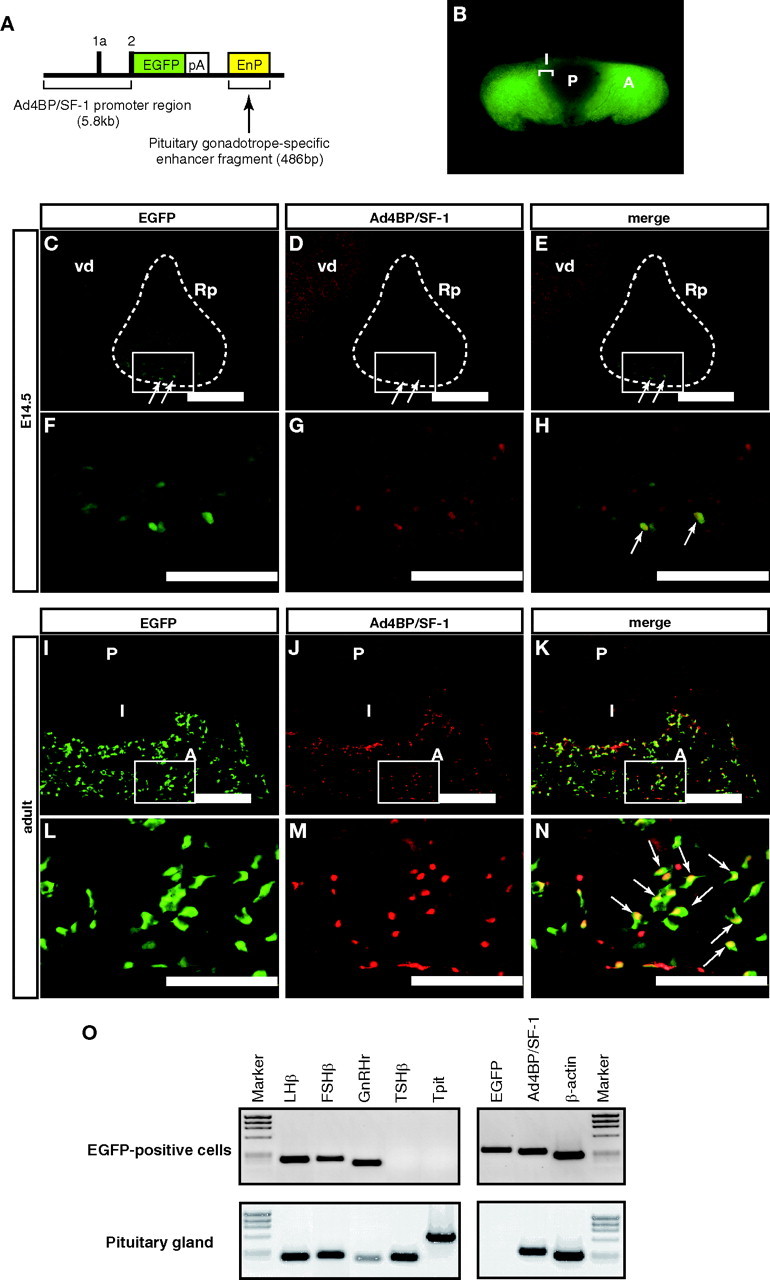

Identification of Pituitary Gonadotrope-Specific Enhancer

To show that the enhancer activity is strictly confined to the gonadotropes, we generated another transgenic mouse line with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) as the reporter gene (pAd4BP-EGFP-EnP in Fig. 3A). Four lines showed EGFP expression in the pituitary at various intensities, and a line termed Ad4-EnP-EGFP (line 4) was used for the following analyses. The transgenic mouse showed anterior pituitary-specific EGFP expression in adulthood (Fig. 3B) and showed no EGFP expression in tissues including the adrenal gland, gonad, and spleen (supplemental Fig. 1 published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). At E14.5, the endogenous expression of Ad4BP/SF-1 was relatively weaker in Rp than in the ventral diencephalon (Fig. 3, D and G), whereas the enhancer-driven EGFP expression was weakly recognized in the ventral part of the Rp (Fig. 3, C and F). As expected, EGFP and endogenous Ad4BP/SF-1 were mostly colocalized (Fig. 3, E and H). Also in adulthood, both EGFP and endogenous Ad4BP/SF-1 were clearly detected in the anterior lobe (Fig. 3, I, J, L, and M), and their expressions were mostly overlapped (Fig. 3, K and N). The possible reason for the presence of nonoverlapping signals is as follows. Ad4BP/SF-1 is predominantly localized in the nucleus whereas EGFP is localized both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. The pituitary specimens contain variously sectioned cells, many of which carry both nucleus and cytoplasm, whereas a few of which carry cytoplasm but not nucleus. The latter sectioning possibly results in EGFP-positive but apparently Ad4BP/SF-1-negative staining (Fig. 3N). In addition, Ad4BP/SF-1-positive and EGFP-negative cells existed (Fig. 3N). It is generally accepted that transgene does not always recapitulate endogenous gene expression. In our present study, approximately 80% of Ad4BP/SF-1-positive cells also expressed EGFP (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

EGFP Expression Induced by the PE

A, A scheme of the construct used for generating Ad4-EnP-EGFP transgenic mouse lines. pA, Polyadenylation signal. EGFP is used as the reporter gene. B, Macroscopic observation of the adult pituitary isolated from Ad4-EnP-EGFP (line 4) mouse. C–N, Immunohistochemical analyses of Ad4-EnP-EGFP (line 4) mice at E14.5 (C–H) and in adulthood (I–N). The heads of the E14.5 fetuses or isolated adult pituitaries were sectioned sagittally, and expression of EGFP (C, F, I, and L) and intrinsic Ad4BP/SF-1 (D, G, J, and M) were examined immunohistochemically. Colocalization of EGFP (green) and Ad4BP/SF-1 (red) is shown in the merged images (E, H, K, and N). Arrows in E, H, and N indicate double-positive cells. F–H and L–N, Enlarged views of the boxed areas in C–E and I–K respectively. Expression of Ad4BP/SF-1 is also observed in the ventral diencephalon (vd). Rps are encircled by broken lines in C–E. A, Anterior lobe; I, intermediate lobe; P, posterior lobe. Bars, 200 μm in C–E and I–K, and 100 μm in F–H and L–N. O, Characterization of EGFP-positive cells. EGFP-positive cells from the pituitary of the adult Ad4-EnP-EGFP (line 4) were sorted. Total RNA prepared from the cells was subjected to RT-PCR with primers for LHβ, FSHβ, GnRHr, TSHβ, and Tpit. Expression of Ad4BP/SF-1, EGFP, and β-actin was also examined. Pituitaries dissected from wild-type mice were used as the control. φX174 digested by HaeIII was used as the DNA size marker.

The EGFP-positive cells in the adult pituitaries were characterized after sorting by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). The EGFP-positive cells were approximately 4.3% of the total cells sorted. Total RNA prepared from the cells was used for RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3O, the expressions of FSHβ, LHβ, GnRHr, EGFP, and Ad4BP/SF-1 were clearly detected, although those of TSHβ and Tpit (corticotrope-specific gene, also known as Tbx19) (35) were not. Taken together, the 486-bp enhancer fragment can drive the reporter gene expression in a manner mimicking the intrinsic expression of Ad4BP/SF-1 throughout development from Rp to mature gonadotropes.

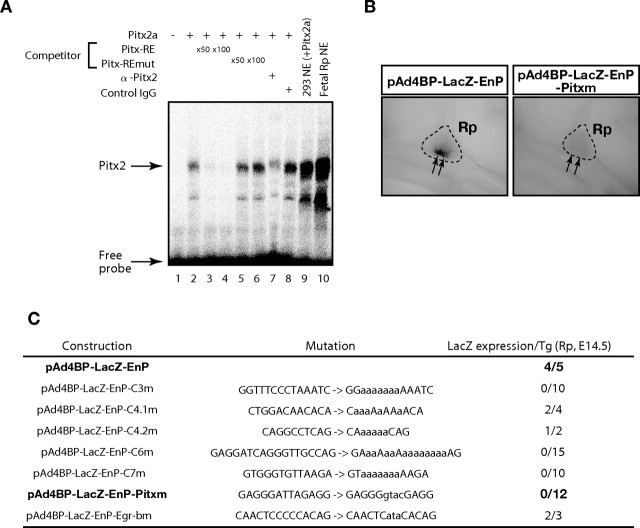

Functional Evaluation of Evolutionally Conserved Elements

As mentioned above, the nucleotide sequences of the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancers were compared among vertebrates. Expectedly, the mouse sequence was conserved in the mammalian species, rat, human, dog, and opossum. Unexpectedly, however, the sequence was not conserved in the chicken, Xenopus tropicalis, and Tetraodon (Fig. 4A). Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of mammals revealed that the enhancer consists of several conserved elements, and one of the elements was found to correlate with the consensus sequence recognized by the bicoid-related factors [Pitx-responsive element (Pitx-RE) in Fig. 4B] (36, 37). Because one of the bicoid-related transcription factors Pitx2 is known as a key factor for proliferation and specification of anterior pituitary cells (27, 32, 38, 39), we examined whether Pitx2 regulates the Ad4BP/SF-1 gene by interacting with this sequence. To determine whether Pitx2 binds to this predicted binding sequence (Pitx-RE), EMSAs were performed. As shown in Fig. 5A, in vitro synthesized Pitx2 formed a DNA-protein complex with Pitx-RE. This complex formation was competed by an excess amount of cold Pitx-RE probe, whereas the mutated probe (Pitx-REmut) failed to compete with it. The DNA-protein complex formation was also inhibited by adding anti-Pitx2 antibody, whereas normal rabbit IgG failed to inhibit the complex formation. In addition, nuclear extracts prepared from 293 cells transfected with a Pitx2a expression plasmid, and nuclear extracts prepared from fetal Rp showed a signal similar to that with the in vitro synthesized Pitx2. Because Pitx2 binds to Pitx-RE in the enhancer fragment, a construct carrying mutation at Pitx-RE (pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP-Pitxm) was subjected to transgenic study. As shown in Fig. 5, B and C, pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP-Pitxm failed to induce reporter gene expression in Rp at E14.5, strongly suggesting that Pitx-RE is essential for the enhancer function.

Fig. 5.

Functions of Conserved Sequences in the PE

A, EMSAs probed with the predicted Pitx2 binding sequence (Pitx-RE) in the enhancer region. In vitro synthesized Pitx2a, nuclear extracts prepared from 293 cells transfected with Pitx2a expression vector, or nuclear extracts prepared from fetal Rp was incubated with Pitx-RE. Excess amounts of nonlabeled probe (competitor), anti-Pitx2 antibody (α-Pitx2), or normal rabbit IgG (control IgG) were used to examine the specificity of the binding. Specific signal for Pitx2 and free probe are indicated by arrows. NE, Nuclear extracts. B, Representative lacZ expressions of the transgenic mice with pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP and pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP-Pitxm at E14.5. Rp is encircled by dotted lines. Arrows indicate the ventral part of Rp. C, Results of transient transgenic mouse assays with mutated constructs. pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP (Fig. 2A) was used as the original plasmid. Each element indicated in Fig. 4B was mutated (substituted nucleotides are indicated by lowercase letters), and the resulting plasmids were subjected to transient transgenic assays. LacZ expression in the transgenic founder animals was evaluated at E14.5, and the result for each construct is shown as number of lacZ-positive founders per number of transgenic founders.

In addition to Pitx-RE, we found five elements (C3, C4.1, C4.2, C6, and C7) in the enhancer region (Fig. 4B). To evaluate their functions, plasmids with each mutated element were subjected to transient transgenic assays. LacZ expression was undetectable in E14.5 fetuses when C3, C6, or C7 was mutated, whereas neither mutation of C4.1 nor that of C4.2 altered the reporter gene expression in the Rp at E14.5 (Fig. 5C).

Moreover, we noticed the presence of three elements; Egr-a, Egr-b, and Egr-c, identical or very similar to the consensus recognition sequence for EGR-1 (40), also known as Krox-24 (41) or NGFI-A (42) (Fig. 4B). The functions of these sequences were analyzed because previous transient promoter assays and knockout mice studies demonstrated that Egr-1 plays essential roles in LHβ transcription (17) and female fertility (43, 44). EMSAs revealed that only Egr-b could interact with EGR-1 (data not shown), and we performed transient transgenic analyses with a construct carrying mutation in the Egr-b. However, mutation in the Egr-b failed to affect lacZ expression at E14.5 (Fig. 5C). Therefore, Egr-b is not likely to be essential for the expression in the fetal Rp, although the function of Egr-b is still unclear in adulthood. It has been reported that GnRH stimulates Ad4BP/SF-1 gene expression in the adult pituitary of rat (45) and sheep (46), and moreover, that EGR-1 is involved in GnRH-responsive gene expression in the adult pituitary (47, 48). Considering these observations, it is possible that EGR-1 enhances Ad4BP/SF-1 transcription in response to the GnRH stimulation.

GATA2 was reported to mediate bone morphogenetic protein signaling gradient and thus induces gonadotrope-specific gene expression in the ventral cells of the anterior pituitary (49). It was also reported that reciprocal interaction of GATA2 and Pit-1 contributes to cell type determination in the anterior pituitary (1, 50, 51). Therefore, we noted that consensus GATA2 binding sequences are present in the mouse enhancer region (GATA-RE1 and GATA-RE2 in Fig. 4B). However, these sequences were not conserved among mammalian genes, and mutation at these GATA2-binding sequences failed to affect lacZ expression (data not shown). This finding seems to be consistent with a recent observation in the pituitary-specific GATA2 knockout mice, showing that the mice are still fertile and secrete gonadotropins (52).

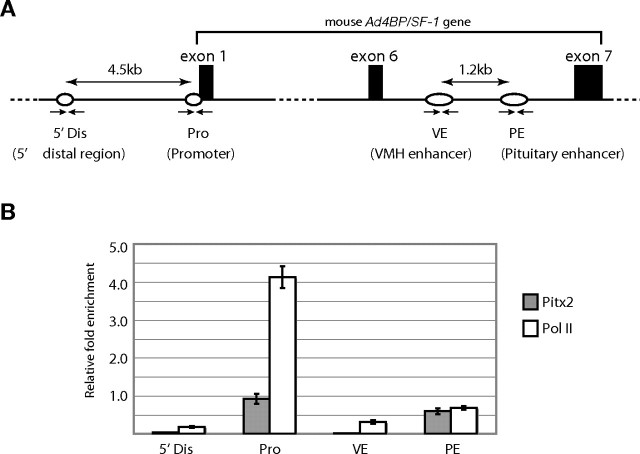

Recruitment of Pitx2 on the Enhancer Region in Vivo

Using adult anterior pituitaries, ChIP assay was performed to demonstrate recruitment of Pitx2 and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to the enhancer region in vivo. DNAs in the immunoprecipitates were subjected to quantitative PCR analyses with specific primer pairs for the pituitary gonadotrope-specific (PE) and VMH-specific enhancers (VE) as well as for the proximal promoter region (Pro) and 5′ far upstream distal region (Dis) (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, Pitx2 was recruited to the Pro and PE regions, whereas the recruitment was hardly detected on the Dis and VE regions. The most significant enrichment of Pol II was detected at the Pro region. Pol II was also accumulated at the PE region, and the accumulation was more than 5-fold and 2-fold higher than at the Dis region and VE region, respectively. These results strongly suggested that the protein complex containing Pitx2 and Pol II mediates interaction between the enhancer and promoter and thereby activates Ad4BP/SF-1 gene expression in the pituitary gonadotrope.

Fig. 6.

Recruitment of Pitx2 on the PE

A, Schematic representation of the locations of the primers used in ChIP analyses. 5′ far upstream distal region (Dis) is localized at approximately 4.5-kb upstream of the proximal promoter region (Pro). The VE and PE are localized within the sixth intron with an approximately 1.2-kb interval. Exons 1, 6, and 7 are indicated with black boxes. Small arrows indicate the primer pairs designed for amplification of each fragment. B, Recruitment of Pitx2 and Pol II on the genomic regions was evaluated by quantitative PCR and indicated as relative fold enrichment values to 0.01% input. These data are mean ± sem of the results of three experiments.

DISCUSSION

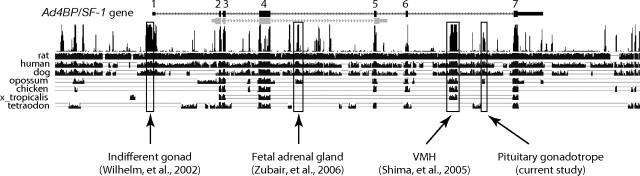

Multiple Tissue-Specific Enhancers of Ad4BP/SF-1 Gene

Transgenic studies to date have identified tissue-specific regulatory regions within the Ad4BP/SF-1 gene (Fig. 7). The proximal upstream region of the gene can drive reporter gene expression in sexually indifferent gonadal cells (24), which thereafter, in the case of males, differentiate into Sertoli cells (53). However, this region does not seem to act as a tissue-specific enhancer because the activity disappears soon (our unpublished data). In this regard, tissue-specific enhancers for the fetal adrenal gland (25) and VMH (26) are localized in the fourth and sixth intron, respectively, and the present study identified the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer within the sixth intron. Although multiple enhancers have been identified in the Ad4BP/SF-1 gene locus, enhancers for the adult testis, adult ovary, adult adrenal cortex, and spleen are yet to be identified. Because YAC and BAC clones covering the Ad4BP/SF-1 and its flanking genes can reproduce the intrinsic gene expression (54, 55), unidentified regulatory regions are expected to be localized within the gene locus.

Fig. 7.

Conserved Tissue-Specific Enhancers of Ad4BP/SF-1 Gene

The nucleotide sequence of the mouse Ad4BP/SF-1 gene is compared with those of seven animal species using the UCSC genome browser. Exon/intron structure of the gene is indicated in the uppermost line. In addition to the present study, recent studies identified tissue-specific enhancers for the fetal adrenal and VMH (25 26 ). Basal promoter of the gene drives gene expression in the indifferent gonads of both sexes (24 ). The fetal adrenal enhancer is located within the fourth intron of the gene, whereas the VE and PE both reside within the sixth intron. The nucleotide sequences of the fetal adrenal gland-specific enhancer region and PE region are conserved in mammalian species, whereas the basal promoter region and its flanking regions are conserved in mouse, rat, human, and dog, but not in the opossum. On the other hand, the VE region is conserved not only in mammals, but also in the chicken and Xenopus tropicalis.

Conservation of cis-Regulatory Elements in the Ad4BP/SF-1 Gene Locus

It is generally accepted that functional cis-regulatory elements of developmentally important genes are highly conserved across animal species even though they are evolutionarily diverged (34). By contrast, there are other classes of genes with strictly preserved expression patterns even in the absence of detectable conserved regulatory sequences (56, 57), suggesting that evolutionary conservation of gene expression is not necessarily coupled with conservation of the cis-regulatory sequences. In fact, comparison of regulatory sequences among mammalian genomes revealed that functional transcription factor binding sites could be diverged even between humans and rodents (58, 59).

As shown in Fig. 7, phylogenetic footprinting analyses demonstrated retrospectively that all enhancer regions of Ad4BP/SF-1 gene identified so far are conserved through mammalian species. Moreover, the VMH-specific enhancer is conserved beyond mammals. Because the fetal adrenal cortex evolutionarily appears when mammalian diversified, it is easily understood that animal species, except for mammals, do not develop the fetal adrenal enhancer. In contrast, the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer is conserved only in mammals but not in nonmammals although the pituitary gonadotropes develop in all vertebrate species. Considering that Ad4BP/SF-1 is expressed in the pituitary of fishes (60, 61, 62) and frogs (63), and Ad4BP/SF-1 plays common and essential roles in the pituitary gonadotrope, it would be expected that the pituitary enhancer is conserved even in nonmammalian species. As a possible explanation, the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer might structurally evolve in a manner preserving the competence and at the same time in a manner changing degeneracy, orientation, and/or spacing of sequences recognized by transcription factors. Due to the presumptive diversification, the regulatory sequences of nonmammalian species would not be easily predicted by the simple phylogenetic footprinting analysis. Although phylogenetic conservation is the primary hallmark of the functional cis-regulatory elements, strict conservation might not be necessarily associated with the regulatory function.

Regulator of Pituitary Gonadotrope-Specific Ad4BP/SF-1 Expression

Conditional gene targeting study for Pitx2 revealed its functional importance in pituitary ontogeny. In brief, analyses of mice harboring hypomorphic and/or null alleles of the Pitx2 gene, resulting in various Pitx2 gene dosages (32), have clarified that Pitx2 is required for the expansion of Rp and the expression of gonadotrope-specific genes including Ad4BP/SF-1 at early and late stages, respectively (33). These observations strongly suggest the involvement of Pitx2 in Ad4BP/SF-1 gene regulation, although the molecular mechanisms for the regulation remain to be determined. Demonstrating the interaction between Pitx2 and the intronic enhancer of Ad4BP/SF-1, the present study provided the molecular basis to the previous findings. However, in the adult pituitary, Pitx2 is primarily expressed in the gonadotrope and thyrotrope, whereas Ad4BP/SF-1 expression is strictly confined to the gonadotrope (28, 31, 64). Considering these observations, although Pitx2 is essential, Pitx2 alone seems to be insufficient for the gonadotrope-specific expression of Ad4BP/SF-1. Rather, it is reasonable to speculate that unknown factor(s) restricts Ad4BP/SF-1 expression to the gonadotrope in conjunction with Pitx2. In this context, factors that potentially recognize the functionally crucial elements, such as C3, C6, and C7, would be plausible candidates to elucidate their differential expression. Further analyses of the uncharacterized core elements will provide extensive information about the molecular mechanisms implicated in gonadotrope-specific transcription of the Ad4BP/SF-1 gene.

We have identified the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer of the Ad4BP/SF-1 gene by transient transgenic assays. This enhancer can recapitulate the intrinsic Ad4BP/SF-1 gene expression throughout the development of the pituitary gonadotrope. The enhancer region consists of multiple core elements that are conserved across mammalian species, and Pitx2 regulates Ad4BP/SF-1 gene transcription through the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation and Characterization of Transgenic Mice

The method used for the construction of the plasmid (pAd4BP-lacZ) vector containing Ad4BP-lacZ cassette was described previously (25, 26). In brief, all first exons (Ia, Ig, and Ix) (65) and the noncoding region of the second exon (5.8-kb DNA fragment) were placed 5′ upstream of the bacterial lacZ reporter gene. Simian virus 40 poly (A) signal was placed 3′ downstream of the reporter gene (Ad4BP-lacZ cassette in Fig. 1). After identification of a cosmid clone with fetal adrenal-, VE, and PE activities (cAd4BP-lacZ-cIA3), the insert DNA was truncated and used for transgenic assays. The pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer region was amplified by PCR using P-UP1 (5′-GGACTAGTGGAAGGGAGGAGGAAAATGAC-3′) and P-LP1 (5′-ACGCGTCGACGGGAAAGGGGCTGGAAACAGG-3′). SpeI and SalI adaptors were added to the 5′-end of P-UP1 and P-LP1, respectively. The amplified fragment (486-bp) was inserted into SpeI–SalI site downstream of lacZ in pAd4BP-lacZ (pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP). To demonstrate the functions of the conserved elements in the enhancer, the nucleotides were substituted by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. pAd4BP-EGFP-EnP was simply constructed by replacing lacZ of pAd4BP-lacZ-EnP with EGFP (pAd4BP-EGFP-EnP). To compare the genomic sequences of the Ad4BP/SF-1 gene locus among animal species, UCSC (University of California at Santa Cruz) genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) (66, 67) was used.

Transgenic mice were generated as described previously (68). The presence or absence of the transgene in the animals was examined by PCR using primers for lacZ (26) and EGFP (5′-CAAGATCCGCCACAACATCG-3′ and 5′-CCAGCAGGACCATGTGATCG-3′). All protocols for animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute for Basic Biology.

Antibody Preparation

Mouse Ad4BP/SF-1 (5–462 amino acids) cDNA was cloned into pET28a (Novagen, Madison, WI) to construct an expression plasmid for His-tagged Ad4BP/SF-1. His-Ad4BP/SF-1 was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) at 30 C for 3 h with 1 mm IPTG induction. The E. coli was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min, and the precipitated E. coli was suspended and sonicated in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, and 10% glycerol. The lysates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 C. Because His-Ad4BP/SF-1 was recovered as an inclusion body, the pellet was resonicated in G buffer [6 m guanidine-HCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 450 mm KCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mm MgCl2, and 0.1% Tween 20]. After ultracentrifugation at 120,000 × g for 30 min at 4 C, the supernatants were mixed with Probond nickel-chelating resin (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) at room temperature for 1 h in the presence of 10 mm imidazole. After washing with 25 mm imidazole, His-Ad4BP/SF-1 was eluted with 200 mm imidazole in G buffer. Guanidine was removed by stepwise dialysis against PBS containing 1 m urea and thereafter 0.1 m l-arginine.

The antibody was prepared based on the rat lymph node method (69). Briefly, 500 μl emulsion containing 125 μg His-Ad4BP/SF-1 and Freund’s complete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) was injected into the hind footpads of a 10-wk-old female WKY/Izm rat (Japan SLC). After 2 wk, cells from the medial iliac lymph nodes of the immunized rat were fused with mouse myeloma SP2 cells at a ratio of 5:1 in 50% polyethylene glycol (PEG4000, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The resulting hybridoma cells were cultured in histone acetyltransferase selection medium (Hybridoma-SFM, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), 5% fetal bovine serum, 5% BM-Condimed H1 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), 100 μm hypoxanthine, 0.4 μm aminopterin, and 16 μm thymidine). Ten days after fusion, the hybridoma supernatants were screened by ELISA against His-Ad4BP/SF-1 recombinant protein. Positive clones were subcloned and rescreened by ELISA and immunoblotting. Finally, the monoclonal antibody, MAb 1B1, was selected. IgG subclass of the antibody was determined using Rat MonoAb-ID Kit (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., South San Francisco, CA). The analysis confirmed that MAb 1B1 is rat IgG2a (κ). Immunoblot study confirmed the specificity of this antibody (supplemental Fig. 2).

Anti-Pitx2 antibody (P2R10) was described previously (64). The other antibodies used in this study were purchased; rabbit anti-GFP antibody from Medical and Biological Laboratories (Nagoya, Japan), anti-RNA polymerase II antibody (N-20, sc-899) from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), Cy3-conjugated goat antirat IgG from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA), and ALEXA Fluoro 488 goat antirabbit IgG from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR).

Immunohistochemistry

Heads of the fetuses or the pituitaries were fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS at 4 C. After fixation, the specimens were soaked overnight into 20% sucrose-PBS under constant rotation at 4 C and then cryo-sectioned. Double immunohistochemical staining for Ad4BP/SF-1 and EGFP was performed as follows. The sections were blocked with 2% skim milk-PBS at room temperature for 30 min, followed by incubation with the anti-Ad4BP/SF-1 rat monoclonal antibody (MAb 1B1, 1:200) and rabbit anti-GFP antibody (1:1000) at 4 C overnight. After washing four times with PBS, the sections were incubated with Cy3-conjugated goat antirat IgG (1:500) and ALEXA Fluoro 488 goat antirabbit IgG (1:500) at room temperature for 3 h and then washed three times with PBS. The specimens were mounted in PermaFluor aqueous mounting medium (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Immunostainings were examined using a Zeiss Axioplan-2 optical microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Nonspecific staining by the primary or secondary antibody was not detected, and the absence of cross-reactivity between the antibodies was also demonstrated (supplemental Fig. 3).

FACS and RT-PCR

The anterior pituitaries were isolated from adult transgenic mice harboring pAd4BP-EGFP-EnP transgene (EnP-EGFP line 4). The tissues were minced, and incubated with 0.25% trypsin-Earle’s balanced salt solution (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 37 C for 30 min. Dispersed cells were washed twice with PBS, filtered through 35-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA), and then subjected to FACS. COULTER EPICS ALTRA system flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA) was used. EGFP-positive gonadotropes were sorted by gating for EGFP-positive and autofluorescence-negative events, as well as light-scattering parameters. The sorted cells were directly collected into a lysis buffer included in the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Total RNA was used for RT-PCR. As a positive control, adult pituitaries were dissected from wild-type mice and subjected to the analyses. The sequences of the primers used for PCR were as follow: FSHβ, 5′-CCCTCCATCCATACTGTT-3′ and 5′-TTTCTCACCTTTCTTTTT-3′; LHβ, 5′-CTGGCCGCAGAGAATGAG-3′ and 5′-AGGGCTACAGGAAAGGAG-3′; GnRHr, 5′-GCTGAATCAGTCCAAGAA-3′ and 5′-AAAGCAAAGAGAAAGAAA-3′; TSHβ, 5′-AGCAGCATCCTTTTGTAT-3′ and 5′-GGGCATCCTGGTATTTCC-3′; Tpit, 5′-CCAAGAACGGCAGACGGATGT-3′ and 5′-GGGAGCAGGCAGAGGCAAAGG-3′; EGFP, 5′-CAAGATCCGCCACAACATCG-3′ and 5′-CCAGCAGGACCATGTGATCG-3′; Ad4BP/SF-1, 5′-GTACGGCAAGGAAGACAGCAT-3′ and 5′-CCACCAGGCACAATAGCAACT-3′; β-actin, 5′-AGGGTGTGATGGTGGGAATGG-3′ and 5′-TGGCTGGGGTGTTGAAGGTCT-3′.

EMSAs

EMSAs were performed basically as described previously (70). Pitx2a cDNA (28) was cloned into pCMX (71) and used for in vitro protein synthesis using a coupled transcription and translation kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). Nuclear extracts were prepared from 293 cells that overexpressed Pitx2a or from fetal Rp at E16.5–17.5. The oligonucleotide probes used for EMSAs for Pitx2 were as follows. Pitx-RE, 5′-ggttaagagGGATTAGagggccaag-3′ and 5′-gcttggccctCTAATCCctcttaac-3′ (uppercase letters indicate Pitx2 binding sequence); Pitx-Rem, 5′-ggttaagagGGGTACGagggccaag-3′ and 5′-gcttggccctCGTACCCctcttaac-3′ (uppercase letters indicate mutated nucleotides). These experiments were performed in triplicate.

ChIP Assay

ChIP was performed according to the method of Boyd and Farnham (72). The anterior pituitaries dissected from ICR adult mice were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde-PBS overnight at 4 C. After tissues were incubated at 4 C for 10 min with 125 mm glycine and washed twice with PBS, they were sonicated in RIPA buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete EDTA-Free, Roche)] using a Branson sonifier (Sonifier Cell Disruptor, Branson, Danbury, CT) to fragment DNA to an average length of 400–800 bp. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4 C for 10 min, the supernatant was precleared by incubating with 20 μl Protein G sepharose (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL) for 1 h, and thereafter incubated overnight with 2 μg anti-Pitx2 antibody or anti-Pol II antibody at 4 C. Normal rabbit IgG (Zymed Laboratories) was used as the control. After adding 50 μl Protein G sepharose, which was preincubated with 2% BSA in RIPA buffer, the mixture was rotated slowly at 4 C for an additional 1 h. The precipitate was recovered by brief centrifugation and then washed eight times with RIPA buffer, and twice with TE (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mm EDTA). The precipitate was diluted in TE with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, incubated with 50 μg deoxyribonuclease-free ribonuclease (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) at 37 C for 1 h, and thereafter treated with 40 μg Proteinase K (Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ) at 55 C for 3 h. After cross-link was reversed by incubation at 65 C overnight, DNAs were extracted by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, precipitated with ethanol, and finally subjected to quantitative PCR. PCR was performed with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) and the following sets of primers: Dis-FW (forward) (5′-CTAGACCCCCAGCGTCGAA-3′) and Dis-Re (reverse) (5′-TGGACAGCTTAGCAGTGGGAA-3′) for 5′ far upstream distal region; Pro-FW (5′-AATGAAGAGAACCACCAACAAAGGA-3′) and Pro-Re (5′-AGTGGCTAGCGGGCTCTCA-3′) for proximal promoter region; VE-FW (5′-CAGGCAGCTCAGAGGCAGGTA-3′) and VE-Re (5′-GGCTTGGAGCGGTGGGTAAAT-3′) for the VMH-specific enhancer region; and PE-FW (5′-GGACCAACTCCCCCACAGTA-3′) and PE-Re (5′-CCTCGGAGCCTACCCTAGTGT-3′) for the pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer region. Amplification of each fragment was monitored by Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The values for samples immunoprecipitated by control IgG was subtracted from the values for the samples immunoprecipitated by anti-Pitx2 antibody or anti-Pol II antibody, and finally the data were indicated as relative fold enrichments to 0.01% input. These ChIP experiments were performed with two individually prepared chromatin samples, and quantitative PCR was performed in triplicate for each sample.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jacques J. Tremblay (Ontogeny-Reproduction Research Unit, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Laval Research Center, Quebec, Canada) for supplying Pitx2 cDNA. We also thank Dr. Kaoru Miyamoto (Department of Biochemistry, Fukui Medical University, Fukui, Japan) for supplying rat Erg-1 cDNA. We also thank Drs. Satoru Kobayashi and Shuji Shigenobu, and Ms. Kayo Arita (Okazaki Institute for Integrative Bioscience, National Institute for Basic Biology, National Institutes of Natural Sciences, Okazaki, Japan) for their support on FACS experiments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan and Swedish Research Council.

Present address for M.Z.: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, 5523 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, Texas 75390-8857.

Present address for K.-i.M.: Department of Molecular Biology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Maidashi 3-1-1, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka, Japan.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online April 16, 2008

Abbreviations: Ad4BP/SF-1, Adrenal4 binding protein/steroidogenic factor-1; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; Dis, distal region; E16.5, embryonic d 16.5; EGFP; enhanced green fluorescent protein; EGR-1, early growth response gene-1; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FW, forward; GnRHr, GnRH receptor; PE, pituitary gonadotrope-specific enhancer; Pitx-RE, Pitx-responsive element; Pol II, RNA polymerase II; Pro, proximal promoter region; Re, reverse; Rp, Rathke’s pouch; VE, VMH-specific enhancer; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus.

References

- 1.Scully KM, Rosenfeld MG 2002. Pituitary development: regulatory codes in mammalian organogenesis. Science 295:2231–2235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu X, Rosenfeld MG 2004. Transcriptional control of precursor proliferation in the early phases of pituitary development. Curr Opin Genet Dev 14:567–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honda S, Morohashi K, Nomura M, Takeya H, Kitajima M, Omura T 1993. Ad4BP regulating steroidogenic P-450 gene is a member of steroid hormone receptor superfamily. J Biol Chem 268:7494–7502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lala DS, Rice DA, Parker KL 1992. Steroidogenic factor I, a key regulator of steroidogenic enzyme expression, is the mouse homolog of fushi tarazu-factor I. Mol Endocrinol 6:1249–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukiyama T, Ueda H, Hirose S, Niwa O 1992. Embryonal long terminal repeat-binding protein is a murine homolog of FTZ-F1, a member of the steroid receptor superfamily. Mol Cell Biol 12:1286–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavorgna G, Ueda H, Clos J, Wu C 1991. FTZ-F1, a steroid hormone receptor-like protein implicated in the activation of fushi tarazu. Science 252:848–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuclear Receptors Nomenclature Committee 1999. A unified nomenclature system for the nuclear receptor superfamily. Cell 97:161–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda Y, Takeda Y, Shikayama T, Mukai T, Hisano S, Morohashi KI 2001. Comparative localization of Dax-1 and Ad4BP/SF-1 during development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis suggests their closely related and distinct functions. Dev Dyn 220:363–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingraham HA, Lala DS, Ikeda Y, Luo X, Shen WH, Nachtigal MW, Abbud R, Nilson JH, Parker KL 1994. The nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 acts at multiple levels of the reproductive axis. Genes Dev 8:2302–2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinoda K, Lei H, Yoshii H, Nomura M, Nagano M, Shiba H, Sasaki H, Osawa Y, Ninomiya Y, Niwa O, Morohashi K-I, Li E 1995. Developmental defects of the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus and pituitary gonadotroph in the Ftz-F1 disrupted mice. Dev Dyn 204:22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao L, Bakke M, Parker KL 2001. Pituitary-specific knockout of steroidogenic factor 1. Mol Cell Endocrinol 185:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnhart KM, Mellon PL 1994. The orphan nuclear receptor, steroidogenic factor-1, regulates the glycoprotein hormone α-subunit gene in pituitary gonadotropes. Mol Endocrinol 8:878–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowkes RC, Burrin JM 2003. Steroidogenic factor-1 enhances basal and forskolin-stimulated transcription of the human glycoprotein hormone α-subunit gene in GH3 cells. J Endocrinol 179:R1–R6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Fowkes RC, Desclozeaux M, Patel MV, Aylwin SJ, King P, Ingraham HA, Burrin JM 2003. Steroidogenic factor-1 and the gonadotrope-specific element enhance basal and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-stimulated transcription of the human glycoprotein hormone α-subunit gene in gonadotropes. Mol Endocrinol 17:2177–2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keri RA, Nilson JH 1996. A steroidogenic factor-1 binding site is required for activity of the luteinizing hormone β subunit promoter in gonadotropes of transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 271:10782–10785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe MW 1999. The equine luteinizing hormone β-subunit promoter contains two functional steroidogenic factor-1 response elements. Mol Endocrinol 13:1497–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halvorson LM, Ito M, Jameson JL, Chin WW 1998. Steroidogenic factor-1 and early growth response protein 1 act through two composite DNA binding sites to regulate luteinizing hormone β-subunit gene expression. J Biol Chem 273:14712–14720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halvorson LM, Kaiser UB, Chin WW 1996. Stimulation of luteinizing hormone β gene promoter activity by the orphan nuclear receptor, steroidogenic factor-1. J Biol Chem 271:6645–6650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tremblay JJ, Marcil A, Gauthier Y, Drouin J 1999. Ptx1 regulates SF-1 activity by an interaction that mimics the role of the ligand-binding domain. EMBO J 18: 3431–3441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Duval DL, Nelson SE, Clay CM 1997. A binding site for steroidogenic factor-1 is part of a complex enhancer that mediates expression of the murine gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Biol Reprod 56:160–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngan ES, Cheng PK, Leung PC, Chow BK 1999. Steroidogenic factor-1 interacts with a gonadotrope-specific element within the first exon of the human gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene to mediate gonadotrope-specific expression. Endocrinology 140:2452–2462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei X, Sasaki M, Huang H, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2002. The orphan nuclear receptor, steroidogenic factor 1, regulates neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene expression in pituitary gonadotropes. Mol Endocrinol 16:2828–2839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowkes RC, Burrin JM 2003. Steroidogenic factor-1: a key regulator of gonadotroph gene expression. J Endocrinol 177:345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilhelm D, Englert C 2002. The Wilms tumor suppressor WT1 regulates early gonad development by activation of Sf1. Genes Dev 16:1839–1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zubair M, Ishihara S, Oka S, Okumura K, Morohashi K 2006. Two-step regulation of Ad4BP/SF-1 gene transcription during fetal adrenal development: initiation by a Hox-Pbx1-Prep1 complex and maintenance via autoregulation by Ad4BP/SF-1. Mol Cell Biol 26:4111–4121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shima Y, Zubair M, Ishihara S, Shinohara Y, Oka S, Kimura S, Okamoto S, Minokoshi Y, Suita S, Morohashi K 2005. Ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus-specific enhancer of Ad4BP/SF-1 gene. Mol Endocrinol 19:2812–2823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Semina EV, Reiter R, Leysens NJ, Alward WL, Small KW, Datson NA, Siegel-Bartelt J, Bierke-Nelson D, Bitoun P, Zabel BU, Carey JC, Murray JC 1996. Cloning and characterization of a novel bicoid-related homeobox transcription factor gene, RIEG, involved in Rieger syndrome. Nat Genet 14:392–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gage PJ, Camper SA 1997. Pituitary homeobox 2, a novel member of the bicoid-related family of homeobox genes, is a potential regulator of anterior structure formation. Hum Mol Genet 6:457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tremblay JJ, Goodyer CG, Drouin J 2000. Transcriptional properties of Ptx1 and Ptx2 isoforms. Neuroendocrinology 71:277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanctot C, Gauthier Y, Drouin J 1999. Pituitary homeobox 1 (Ptx1) is differentially expressed during pituitary development. Endocrinology 140:1416–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charles MA, Suh H, Hjalt TA, Drouin J, Camper SA, Gage PJ 2005. PITX genes are required for cell survival and Lhx3 activation. Mol Endocrinol 19:1893–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gage PJ, Suh H, Camper SA 1999. Dosage requirement of Pitx2 for development of multiple organs. Development 126:4643–4651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suh H, Gage PJ, Drouin J, Camper SA 2002. Pitx2 is required at multiple stages of pituitary organogenesis: pituitary primordium formation and cell specification. Development 129:329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulin F, Nobrega MA, Plajzer-Frick I, Holt A, Afzal V, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA 2005. In vivo characterization of a vertebrate ultraconserved enhancer. Genomics 85:774–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamolet B, Pulichino AM, Lamonerie T, Gauthier Y, Brue T, Enjalbert A, Drouin J 2001. A pituitary cell-restricted T box factor, Tpit, activates POMC transcription in cooperation with Pitx homeoproteins. Cell 104:849–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson DS, Sheng G, Jun S, Desplan C 1996. Conservation and diversification in homeodomain-DNA interactions: a comparative genetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:6886–6891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Driever W, Nusslein-Volhard C 1989. The bicoid protein is a positive regulator of hunchback transcription in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature 337:138–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitamura K, Miura H, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Yanazawa M, Katoh-Fukui Y, Suzuki R, Ohuchi H, Suehiro A, Motegi Y, Nakahara Y, Kondo S, Yokoyama M 1999. Mouse Pitx2 deficiency leads to anomalies of the ventral body wall, heart, extra- and periocular mesoderm and right pulmonary isomerism. Development 126:5749–5758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin CR, Kioussi C, O'Connell S, Briata P, Szeto D, Liu F, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Rosenfeld MG 1999. Pitx2 regulates lung asymmetry, cardiac positioning and pituitary and tooth morphogenesis. Nature 401:279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao XM, Koski RA, Gashler A, McKiernan M, Morris CF, Gaffney R, Hay RV, Sukhatme VP 1990. Identification and characterization of the Egr-1 gene product, a DNA-binding zinc finger protein induced by differentiation and growth signals. Mol Cell Biol 10:1931–1939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lemaire P, Vesque C, Schmitt J, Stunnenberg H, Frank R, Charnay P 1990. The serum-inducible mouse gene Krox-24 encodes a sequence-specific transcriptional activator. Mol Cell Biol 10:3456–3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milbrandt J 1987. A nerve growth factor-induced gene encodes a possible transcriptional regulatory factor. Science 238:797–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Levi G, Trembleau A, Gourdji D, Driancourt MA, Rao CV, Charnay P 1998. Multiple pituitary and ovarian defects in Krox-24 (NGFI-A, Egr-1)-targeted mice. Mol Endocrinol 12:107–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadovsky Y, Crawford PA, Woodson KG, Polish JA, Clements MA, Tourtellotte LM, Simburger K, Milbrandt J 1995. Mice deficient in the orphan receptor steroidogenic factor 1 lack adrenal glands and gonads but express P450 side-chain-cleavage enzyme in the placenta and have normal embryonic serum levels of corticosteroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:10939–10943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haisenleder DJ, Yasin M, Dalkin AC, Gilrain J, Marshall JC 1996. GnRH regulates steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1) gene expression in the rat pituitary. Endocrinology 137:5719–5722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turzillo AM, Quirk CC, Juengel JL, Nett TM, Clay CM 1997. Effects of ovariectomy and hypothalamic-pituitary disconnection on amounts of steroidogenic factor-1 mRNA in the ovine anterior pituitary gland. Endocrine 6:251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorn C, Ou Q, Svaren J, Crawford PA, Sadovsky Y 1999. Activation of luteinizing hormone β gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone requires the synergy of early growth response-1 and steroidogenic factor-1. J Biol Chem 274:13870–13876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tremblay JJ, Drouin J 1999. Egr-1 is a downstream effector of GnRH and synergizes by direct interaction with Ptx1 and SF-1 to enhance luteinizing hormone β gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol 19:2567–2576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Treier M, Gleiberman AS, O'Connell SM, Szeto DP, McMahon JA, McMahon AP, Rosenfeld MG 1998. Multistep signaling requirements for pituitary organogenesis in vivo. Genes Dev 12:1691–1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenfeld MG, Briata P, Dasen J, Gleiberman AS, Kioussi C, Lin C, O'Connell SM, Ryan A, Szeto DP, Treier M 2000. Multistep signaling and transcriptional requirements for pituitary organogenesis in vivo. Recent Prog Horm Res 55:1–13; discussion 13–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dasen JS, O'Connell SM, Flynn SE, Treier M, Gleiberman AS, Szeto DP, Hooshmand F, Aggarwal AK, Rosenfeld MG 1999. Reciprocal interactions of Pit1 and GATA2 mediate signaling gradient-induced determination of pituitary cell types. Cell 97:587–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Charles MA, Saunders TL, Wood WM, Owens K, Parlow AF, Camper SA, Ridgway EC, Gordon DF 2006. Pituitary-specific Gata2 knockout: effects on gonadotrope and thyrotrope function. Mol Endocrinol 20:1366–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaboissier M-C, Kobayashi A, Vidal VIP, Lutzkendorf S, van de Kant HJG, Wegner M, de Rooij DG, Behringer RR, Schedl A 2004. Functional analysis of Sox8 and Sox9 during sex determination in the mouse. Development 131:1891–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fatchiyah, Zubair M, Shima Y, Oka S, Ishihara S, Fukui-Katoh Y, Morohashi K 2006. Differential gene dosage effects of Ad4BP/SF-1 on target tissue development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 341:1036–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karpova T, Maran RR, Presley J, Scherrer SP, Tejada L, Heckert LL 2005. Transgenic rescue of SF-1-null mice. Ann NY Acad Sci 1061:55–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oda-Ishii I, Bertrand V, Matsuo I, Lemaire P, Saiga H 2005. Making very similar embryos with divergent genomes: conservation of regulatory mechanisms of Otx between the ascidians Halocynthia roretzi and Ciona intestinalis Development 132:1663–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ludwig MZ, Palsson A, Alekseeva E, Bergman CM, Nathan J, Kreitman M 2005. Functional evolution of a cis-regulatory module. PLoS Biol 3:e93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Smith NG, Brandstrom M, Ellegren H 2004. Evidence for turnover of functional noncoding DNA in mammalian genome evolution. Genomics 84:806–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dermitzakis ET, Kirkness E, Schwarz S, Birney E, Reymond A, Antonarakis SE 2004. Comparison of human chromosome 21 conserved nongenic sequences (CNGs) with the mouse and dog genomes shows that their selective constraint is independent of their genic environment. Genome Res 14:852–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Higa M, Kanda H, Kitahashi T, Ito M, Shiba T, Ando H 2000. Quantitative analysis of fushi tarazu factor 1 homolog messenger ribonucleic acids in the pituitary of salmon at different prespawning stages. Biol Reprod 63:1756–1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.von Hofsten J, Jones I, Karlsson J, Olsson PE 2001. Developmental expression patterns of FTZ-F1 homologues in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Gen Comp Endocrinol 121:146–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yaron Z, Gur G, Melamed P, Rosenfeld H, Elizur A, Levavi-Sivan B 2003. Regulation of fish gonadotropins. Int Rev Cytol 225:131–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mayer LP, Overstreet SL, Dyer CA, Propper CR 2002. Sexually dimorphic expression of steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) in developing gonads of the American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana Gen Comp Endocrinol 127:40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hjalt TA, Semina EV, Amendt BA, Murray JC 2000. The Pitx2 protein in mouse development. Dev Dyn 218:195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kimura R, Yoshii H, Nomura M, Kotomura N, Mukai T, Ishihara S, Ohba K, Yanase T, Gotoh O, Nawata H, Morohashi K 2000. Identification of novel first exons in Ad4BP/SF-1 (NR5A1) gene and their tissue- and species-specific usage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 278:63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D 2002. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res 12:996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuhn RM, Karolchik D, Zweig AS, Trumbower H, Thomas DJ, Thakkapallayil A, Sugnet CW, Stanke M, Smith KE, Siepel A, Rosenbloom KR, Rhead B, Raney BJ, Pohl A, Pedersen JS, Hsu F, Hinrichs AS, Harte RA, Diekhans M, Clawson H, Bejerano G, Barber GP, Baertsch R, Haussler D, Kent WJ 2007. The UCSC genome browser database: update 2007. Nucleic Acids Res 35:D668–D673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Hogan B, Beddington F, Lacy E 1994. Manipulating the mouse embryo. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

- 69.Kishiro Y, Kagawa M, Naito I, Sado Y 1995. A novel method of preparing rat-monoclonal antibody-producing hybridomas by using rat medial iliac lymph node cells. Cell Struct Funct 20:151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morohashi K, Honda S, Inomata Y, Handa H, Omura T 1992. A common trans-acting factor, Ad4-binding protein, to the promoters of steroidogenic P-450s. J Biol Chem 267:17913–17919 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Umesono K, Murakami KK, Thompson CC, Evans RM 1991. Direct repeats as selective response elements for the thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and vitamin D3 receptors. Cell 65:1255–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boyd KE, Farnham PJ 1997. Myc versus USF: discrimination at the cad gene is determined by core promoter elements. Mol Cell Biol 17:2529–2537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]